Abstract

With the rapid deployment of high-speed maglev transportation systems worldwide, the operational velocity, electromagnetic complexity, and channel dynamics have far exceeded those of conventional rail systems, imposing more stringent requirements on real-time capability, reliability, and interference robustness in wireless communication. In maglev environments exceeding 600 km/h, the channel becomes predominantly line-of-sight with sparse scatterers, exhibiting strong Doppler shifts, rapidly varying spatial characteristics, and severe interference, all of which significantly degrade the stability and convergence performance of traditional beamforming algorithms. Adaptive smart antenna technology has therefore become essential in high-mobility communication and sensing systems, as it enables real-time spatial filtering, interference suppression, and beam tracking through continuous weight updates. To address the challenges of slow convergence and high steady-state error in rapidly varying maglev channels, this work proposes a new Fractional Proportionate Normalized Least Mean Square (FPNLMS) adaptive beamforming algorithm. The contributions of this study are twofold. (1) A novel FPNLMS algorithm is developed by embedding a fractional-order gradient correction into the power-normalized and proportionate gain framework of PNLMS, forming a unified LMS-type update mechanism that enhances error tracking flexibility while maintaining computational complexity. This integrated design enables the proposed method to achieve faster convergence, improved robustness, and reduced steady-state error in highly dynamic channel conditions. (2) A unified convergence analysis framework is established for the proposed algorithm. Mean convergence conditions and practical step-size bounds are derived, explicitly incorporating the fractional-order term and generalizing classical LMS/PNLMS convergence theory, thereby providing theoretical guarantees for stable deployment in high-speed maglev beamforming. Simulation results verify that the proposed FPNLMS algorithm achieves significantly faster convergence, lower mean square error, and superior interference suppression compared with LMS, NLMS, FLMS, and PNLMS, demonstrating its strong applicability to beamforming in highly dynamic next-generation maglev communication systems.

1. Introduction

Smart antenna technology leverages spatial signal processing to improve wireless system performance, offering wider coverage, higher throughput, and better spectral efficiency in multipath propagation environments. It has been widely applied in wireless communications, radar, navigation, sonar, and tracking systems [1,2,3,4]. By accurately estimating the direction of arrival (DOA) [5,6] and shaping radiation patterns through adaptive beamforming [7], smart antennas strengthen desired-signal reception while effectively suppressing interference.

Adaptive beamforming algorithms iteratively update array weights to maintain optimal reception in time-varying environments. Representative algorithms include least mean square (LMS) [8,9], recursive least squares (RLS) [10], and constant modulus algorithms (CMA) [11], typically formulated under minimum variance [12,13], minimum mean square error (MMSE) [14], or constant modulus [15] criteria. The LMS algorithm remains widely adopted due to its simplicity and robustness but suffers from slow convergence in highly dynamic or interference-rich scenarios. Enhanced variants such as normalized LMS (NLMS) [16], two-stage LMS (LLMS) [17], RLS-LMS (RLMS) [18], variable-step LMS [19,20], and interference-aware beamformers [21,22,23] improve stability or convergence at the cost of computational complexity. Shrinkage-based approaches [24] have recently shown promise in accelerating convergence while reducing steady-state error, and adaptive beamforming continues to be actively studied in medical imaging [25], millimeter-wave 5G [26], and intelligent reflecting surface (IRS) systems [27,28].

In recent years, adaptive beamforming for high-mobility and high-frequency systems—such as millimeter-wave vehicular links, UAV-based communication, and high-speed railway or maglev channels—has attracted increasing attention. These scenarios exhibit rapidly varying propagation paths, short channel coherence time, and strong Doppler effects, which significantly degrade the tracking performance of conventional LMS-type algorithms. Moreover, emerging reconfigurable and wideband beam-scanning antenna arrays further increase the demand for algorithms that jointly offer fast convergence, numerical stability, and low computational cost suitable for real-time FPGA/SDR implementation.

Recent developments in beam-scanning antenna arrays demonstrate the trend toward flexible, large-angle, and efficient pattern control. For example, wide-scanning phased arrays and dual-polarized reconfigurable structures have shown stable radiation characteristics across large scan ranges [29], while vehicular beam-scanning architectures have illustrated the need for rapid beam updating and interference suppression under dynamic, mobility-induced channel variations [30]. These advancements underscore the importance of lightweight adaptive beamforming algorithms capable of operating reliably in fast time-varying, interference-prone, and hardware-constrained environments. In this context, the proposed FPNLMS algorithm complements recent antenna-array developments by providing a computationally efficient and robust solution for dynamic beam adaptation.

Fractional-order signal processing has recently attracted growing interest in engineering applications including image enhancement [31], control systems [32], power-electronic circuits [33], and wireless channel tracking [34]. Fractional algorithms have demonstrated improved adaptability in recommendation systems [35], channel equalization [36], active noise control [37,38], beamforming [39], and power signal modeling [40]. They also support fractional-order differential equations [41], electromagnetic transmission modeling [42], and wireless sensor networks [43]. These advances motivate fractional techniques for adaptive beamforming, offering improved flexibility in weight updates.

Among adaptive algorithms, LMS provides low complexity but slow convergence; NLMS improves stability; fractional LMS (FLMS) introduces fractional-order dynamics for smoother error surfaces; and proportionate NLMS (PNLMS) accelerates convergence under sparse or energy-unequal tap conditions. Building on these approaches, this work develops a fractional proportionate NLMS (FPNLMS) algorithm that combines fractional-order gradients with proportionate normalization. The method enhances convergence speed, improves steady-state precision, and strengthens interference suppression capability in dynamic and low-SNR environments. To further clarify how this work differs from existing LMS-type adaptive beamformers, the main innovations of the proposed methodology are summarized as follows.

(1) A unified fractional power-normalized proportionate LMS framework is developed, in which fractional-order gradient correction is embedded into the normalized and proportionate update mechanism of PNLMS. This integration couples fractional-order error dynamics with gain allocation and power normalization, enabling faster transient convergence and improved robustness under fast time-varying, high-Doppler maglev channels. (2) A generalized convergence analysis is established for the proposed FPNLMS algorithm, extending the classical LMS/PNLMS stability conditions to fractional-order adaptive filtering. The derived step-size bounds and mean-convergence characteristics provide theoretical support for achieving both rapid convergence and low steady-state error in sparse and interference-rich propagation environments. To evaluate performance, five adaptive algorithms—LMS, NLMS, FLMS, PNLMS, and FPNLMS—are simulated in a high-speed maglev communication scenario using MATLAB R2023b. Simulation results indicate that the proposed FPNLMS algorithm improves beam-tracking accuracy by approximately 20% and interference suppression by about 25% over conventional LMS-type methods. To clearly present the technical flow, the structure of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the adaptive beamformer architecture based on NLMS, FLMS, PNLMS, and FPNLMS algorithms. Section 3 reviews the LMS algorithm and its extended forms. Section 4 presents the derivation and theoretical foundation of the FPNLMS algorithm. Section 5 discusses convergence characteristics. Section 6 provides simulation analysis of all five algorithms. Section 7 concludes the paper.

2. Proposed System Model

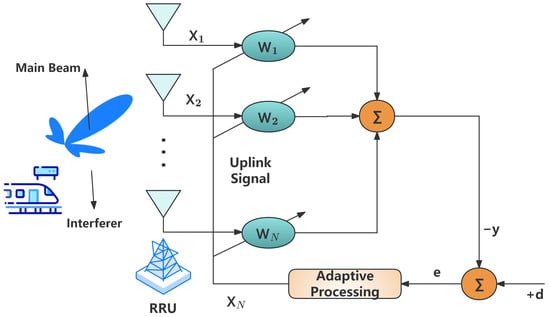

To achieve high-speed, high-reliability vehicle-to-ground communication beam control in a high-speed maglev train environment, this section establishes a mathematical model of an adaptive beamformer based on a Uniform Linear Array (ULA). The basic principle structure of the adaptive beamformer is shown in Figure 1. This structure is applicable to various adaptive beamforming algorithms such as LMS, PNLMS, and FPNLMS. This structure is an uplink receiving beamforming architecture: the train-side antenna transmits the uplink signal, which is received by the multi-antenna array of the ground RRU via the air interface. Each branch signal is multiplied by adaptive weights and coherently synthesized to obtain the array output y, which serves as the input to the subsequent demodulation module. Simultaneously, the array output is compared with the desired signal d to generate an error e, and the beam weights are updated through an adaptive algorithm to ensure the main lobe points towards the train direction and suppresses interference signals from other directions.

Figure 1.

Simplified schematic diagram of an adaptive beamformer.

The system uses a uniform linear array (ULA) with equal spacing consisting of L array elements. The element spacing is set to half the wavelength of the received signal to satisfy the spatial sampling criterion and ensure maximum directional resolution. Each signal source comes from M remote transmitters, including target signals and various interference sources, whose incident signals arrive at different angles in front of and to the side of the array. To simplify the modeling, it is assumed that the DOA of all signal sources is known (if unknown, it can be obtained through the DOA estimation algorithm [44]).

At the array receiver, the desired signal, interference signal, and noise received by each array element are superimposed to form the input signal vector. To construct an array receiver model that reflects the characteristics of the actual wireless environment, this paper uses Binary Phase Shift Keying (BPSK) as the signal modulation method, and assumes that each signal sample satisfies the independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) assumption. BPSK modulation has the advantages of simple symbol structure and good phase stability, and can characterize the signal superposition characteristics of typical communication systems without increasing modeling complexity. Therefore, it is widely used in simulation research of smart antennas and beamforming algorithms. The array received signal vector can be represented as:

where is an array snapshot of dimension , and each element represents the complex signal received by the i-th array element at sampling time n. L is the number of array elements. The signal vector is constructed by superimposing signals incident from different spatial directions according to the array geometry and phase difference to form the overall receiving vector of the array at the n-th sampling time. Assuming there are M spatial signal sources in the system, one of which is the target signal and the other are interference signals, the array receiving vector can be written as shown in Equation (2). In the subsequent derivation, each signal source is no longer explicitly distinguished, but is uniformly described by the statistical characteristics of the receiving vector . This modeling method is based on the standard signal superposition model of array signal processing, which can effectively characterize the actual scenario of multiple signal sources acting on the array receiver at the same time. The detailed derivation process can be found in reference [45].

where represents the desired signal, represents the i-th interference signal; and are the steering vectors of the desired signal and the i-th interference signal, respectively, used to describe the spatial response characteristics of the signal on each array element when it is incident from a specific spatial direction. is additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN). For a plane wave with an incident angle of , its array steering vector is defined as:

The phase shift between adjacent array elements is:

In this expression, D is the element spacing, is the signal wavelength, and is the signal incident angle. The incident angles of the desired signal and the interference signal are denoted as and , respectively. The steering vector can be defined as shown in Equations (5) and (6):

where and represent the phase shifts of the incident angles of the desired signal and the interference signal, respectively, as defined in Equations (7) and (8).

Let the weighting coefficient vector be , which is used to weight and superimpose the signals received by each array element in the input signal vector . In each iteration, the weighting vector c is multiplied by the input signal to obtain the beamforming output at the current moment, as shown in Equation (9):

where represents the Hermitian transpose of the weight coefficient vector , i.e., , where represents the complex conjugate operation. Let be the desired signal, and the error signal feedback is used to correct the weight vector in real time. The error signal is defined as shown in Equation (10):

When analyzing beamforming performance, the array factor (AF) is typically used to describe the directional response characteristics of the array to different incident angles. For a ULA, the expression for its beam pattern is shown in Equation (11):

where L represents the total number of array elements, its size directly affects the main lobe width and side lobe suppression performance; , given by Equation (4), is the array factor, reflecting the relationship between the array directional response and the incident angle , and is an important indicator for evaluating beamforming effectiveness. The main lobe direction corresponds to the desired signal, while the side lobe region reflects the system’s interference suppression capability.

To ensure the feasibility and stability of the model in high-speed maglev scenarios, this study makes the following assumptions about the system: The channel is stationary over a short period, with parameters changing slowly; the input signal follows a zero-mean random process, and the signal samples are independent of each other, satisfying the i.i.d. condition; the channel variation amplitude does not exceed the update response range of the adaptive algorithm; the array calibration is ideal, with no mutual coupling or amplitude/phase errors. Under these assumptions, the adaptive beamforming algorithm based on PNLMS and FPNLMS can maintain stable and reliable convergence performance, providing a theoretical guarantee for beam control in high-speed maglev communication environments.

3. LMS Algorithm and Its Extended Forms

The LMS algorithm is an adaptive filtering algorithm based on the principle of gradient descent. Its core objective is to minimize the mean square error (MSE) at each time step. The cost function of the LMS algorithm is based on the MSE criterion, as shown in Equation (12), and is used to measure the square error between the desired signal and the actual output signal at the current time step.

where represents the expectation operator. Substituting Equation (9) into Equation (12) and expanding and rearranging the terms, we obtain Equation (13):

where represents the autocorrelation matrix of the input signal, and represents the cross-correlation vector. The goal of adaptive beamforming is to minimize by continuously adjusting the weights , that is, to obtain the maximum response in the direction of the target signal, while forming nulls in the direction of interference, thus achieving spatial filtering. To find the weight vector that minimizes , the LMS algorithm uses gradient descent for optimization. The general form of its weight update is shown in Equation (14):

Since is a complex vector, the actual gradient direction is . Its expression is shown in Equation (15):

The LMS algorithm employs stochastic gradient descent (SGD) to approximate the desired value using the current signal sample. Replacing the gradient with an instantaneous estimate yields:

where is the instantaneous error signal. Substituting Equation (16) into the standard gradient descent Equation (14), we obtain Equation (17):

Furthermore, the weight update relationship of the LMS algorithm is obtained, as shown in Equation (18):

The step size is used to adjust the algorithm’s convergence speed and steady-state performance. A larger results in faster convergence but may increase the steady-state error; a smaller improves steady-state performance but slows down the convergence speed. Therefore, to ensure algorithm stability, the step size must satisfy the following condition:

where is the largest eigenvalue of the autocorrelation matrix R of the input signal. The core idea of the LMS algorithm is to use the instantaneous error signal to correct the weight vector in each iteration, thereby gradually approximating the desired beam direction and achieving low-complexity adaptive beam control. The LMS algorithm has advantages such as simple implementation, low computational cost, and stable convergence. However, its convergence speed is greatly affected by the distribution of signal eigenvalues, and it may exhibit slower convergence in high-interference, fast-time-varying channels.

4. Proposed FPNLMS Algorithm

4.1. Algorithm Background and Research Motivation

The convergence speed of the traditional LMS algorithm depends on the power distribution of the input signal. However, in high-speed maglev communication scenarios, the channel gain changes rapidly over time, leading to slow convergence or even divergence in traditional LMS. To alleviate this problem, early research proposed the Normalized Least Mean Square (NLMS) and Proportional Normalized Least Mean Square (PNLMS) algorithms. By normalizing power and proportionalizing step size allocation, these algorithms enhance their response capability on high-energy paths, achieving faster convergence speed and stronger channel adaptability.

The NLMS algorithm, based on the LMS framework, introduces an input signal power normalization term, allowing the step size to adaptively adjust with changes in signal energy, effectively suppressing the impact of power fluctuations on convergence speed and stability. Compared to traditional LMS, NLMS has the advantages of more stable convergence and greater sensitivity to signal power changes, laying the theoretical foundation for the subsequent PNLMS algorithm. PNLMS further introduces a proportionalized gain matrix on top of NLMS, concentrating the update weights towards the main channel path, improving convergence speed and adaptability to sparse channels. However, PNLMS still suffers from excessive update rigidity near steady state, making it difficult to balance fast convergence with low steady-state error.

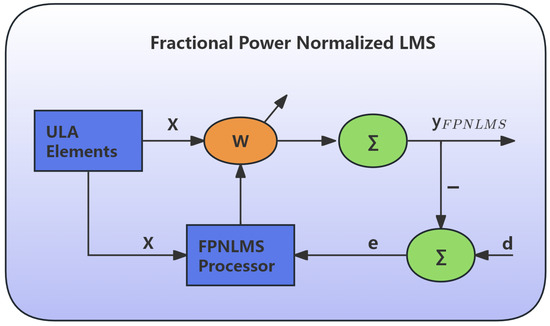

In recent years, the application of fractional derivative theory in the field of adaptive signal processing has become increasingly widespread. Fractional derivatives can introduce non-integer order differential information into the gradient correction term, more fully capturing the dynamic evolution characteristics of the error signal, thus providing higher degrees of freedom for the algorithm update strategy. Early fractional LMS (FLMS) algorithms have been extensively studied. For example, Zubair proposed a momentum-based FLMS algorithm for power signal parameter estimation [46], Yin et al. proposed a bias-compensated fractional normalized LMS for noisy environments and conducted stability analysis [47], Chaudhary et al. proposed a multi-innovation FLMS in 2021 to improve recognition performance [48], and Wahab systematically summarized the advantages and disadvantages of fractional learning algorithms from the perspective of performance analysis [49]. This also laid the foundation for the FPNLMS algorithm proposed in this paper. This paper introduces a fractional-order gradient adjustment mechanism into the PNLMS framework, constructing a novel FPNLMS algorithm that combines power normalization, proportional gain, and fractional-order flexible adjustment. This algorithm is particularly suitable for the “rapidly changing channel + low multipath” environment of high-speed maglev trains. Figure 2 shows a schematic diagram of the FPNLMS adaptive beamformer. This structure further introduces a fractional-order gradient adjustment term into the PNLMS framework to enhance the algorithm’s update flexibility and steady-state accuracy under rapidly changing environments. This mechanism enables faster and more stable convergence under dynamic channel conditions, laying a theoretical foundation for subsequent weight update strategies and convergence analysis.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of FPNLMS adaptive beamformer.

4.2. Fractional Gradient Foundation

For a polynomial function , when the order is , its left fractional derivative is expressed as shown in Equation (20):

where is the gamma function, denoted as

The fractional part only corrects the non-integer order of the linear terms of the weights, so it is not necessary to find the fractional derivative of the higher-order polynomials (the case of will not occur). When and , Equation (20) can be simplified to Equation (22).

Similarly, when and , the right fractional derivative is in the form shown in Equation (23):

Since the fractional derivative operation is not well defined in the real number field for negative values (e.g., non-integer powers of negative numbers lead to complex results), it is necessary to separate the magnitude and sign of the weights. This paper adopts the following decomposition form, as shown in Equation (24):

Here, the weight c is not a number, but a column vector of length , represents taking the absolute value of each element, and represents the sign function, as shown in Equation (25):

Combining and , a unified expression for the fractional derivative of the error with respect to c can be obtained as shown in Equation (26):

The symbol ⊙ represents the element-wise (Hadamard) product. In gradient-based optimization strategies, the core objective is to minimize the cost function , which is defined as follows:

where represents the instantaneous error signal, is its complex conjugate, and the expectation operator represents the statistical average. To minimize the cost function, it is necessary to differentiate with respect to the weight vector c and update the weights accordingly.

In traditional LMS algorithms, the update process is based on first-order gradient descent, which achieves good performance in statistically stationary or quasi-stationary environments. However, in high-speed maglev scenarios, the channel changes rapidly over time, and the receiving array faces significant non-stationary interference and noise conditions. First-order LMS often exhibits slow convergence speed, insufficient tracking performance, and high steady-state error in such environments. Fractional calculus possesses the characteristics of “memory” and “nonlocality,” enabling it to utilize both current error information and historical states during gradient descent, thus significantly improving the algorithm’s robustness under non-stationary signals. To further improve the algorithm’s convergence performance and steady-state accuracy in complex non-stationary environments, this paper introduces the concept of fractional-order derivatives into this framework, thereby constructing a fractional-order power normalized LMS (FPNLMS) algorithm. To clearly characterize the role of fractional derivatives, the update vector is decomposed into integer-order and fractional-order components: the final weight update can be represented as shown in Equation (28).

where represents the integer-order weight component updated based on the traditional LMS algorithm, and its corresponding integer-order update is shown in Equation (29):

The positive step size is a crucial design parameter controlling the algorithm’s convergence speed and steady-state performance. Within the cost function framework that incorporates a fractional update mechanism, the step size factor not only determines the response magnitude of the gradient descent process but also needs to be coordinated with the fractional derivative term to ensure the algorithm’s stability and convergence.

As mentioned in Section 3, the traditional LMS uses the first-order gradient, as shown in Equation (17). Since the gradient of with respect to is , the expectation is approximated by the instantaneous value (stochastic gradient method), and the standard LMS update expression is shown in Equation (29).

Fractional gradients no longer use the first derivative, but instead introduce the fractional derivative operator . The idea is to replace with , that is, to replace the ordinary gradient with the fractional derivative, thus adding a layer of “flexible” adjustment during updates. Therefore, the corresponding weight update is:

where is the step size of the fractional part. The formula is: , taking the fractional derivative with respect to c:

Since is independent of c, only the dependency of on c is retained. The chain rule is updated to:

However, note that what we need here is the fractional-order correction , not the full update , so the definition is as shown in Equation (34).

Substituting the fractional derivative result from Equation (26) into Equation (34), we obtain the explicit expression for the fractional correction term:

This equation clearly shows that the fractional-order correction not only depends on the current input signal and the error signal, but also introduces nonlinear adjustment of the weight magnitude through , which enhances the algorithm’s adaptability.

Therefore, based on the superposition of the traditional LMS integer-order update and fractional-order correction term, the final weight update structure of this section is shown in Equation (28), where is calculated by integer-order LMS (Equation (29)) and is obtained by fractional-order derivative correction (Equation (35)). This structure provides a natural interface for subsequent coupling with PNLMS.

When only the fractional-order correction and LMS superposition are considered without introducing a scaling mechanism, the fractional-order least mean square algorithm (FLMS) is formed, as shown in Equation (36).

This algorithm, based on the LMS algorithm, superimposes a fractional-order correction term, introducing flexible adjustment to the gradient descent process through non-integer derivatives. Specifically, the integer-order part ensures the basic convergence and directionality of the algorithm, while the fractional-order correction term adaptively adjusts the update amount according to the current weight magnitude, thereby achieving a steeper descent curve in the early stages of the algorithm and accelerating the convergence speed. In recent years, FLMS has been widely used in adaptive filtering, array signal processing, and noise-robust parameter estimation, with the advantage of achieving faster convergence speed and higher steady-state accuracy without significantly increasing computational complexity. This characteristic also lays the foundation for subsequent combination with the proportionally normalized least mean square algorithm (PNLMS), thus forming the theoretical precursor of the fractional-order proportionally normalized least mean square algorithm (FPNLMS) proposed in this paper.

4.3. Fractional PNLMS Algorithm and Optimization Strategy

In the standard LMS algorithm, the step size is usually fixed. When the input signal energy fluctuates significantly, a fixed step size struggles to balance fast convergence with low steady-state error, and may even lead to algorithm instability. To address this issue, early research proposed the Normalized Least Mean Square (NLMS) algorithm, which introduces an input power normalization term into the weight update, as shown in Equation (37):

Here, is a regularization factor used to prevent excessively large step sizes caused by excessively small input power, which could lead to numerical instability. The NLMS algorithm essentially introduces a normalization term into the gradient update of LMS, causing the actual update magnitude to automatically adjust with the input energy, thus exhibiting stronger stability and adaptability to changes in channel gain. Compared to standard LMS, NLMS does not require a strictly defined upper limit on the step size to achieve faster convergence and improved steady-state error, making it one of the commonly used benchmark algorithms in adaptive beamforming.

Based on NLMS, the Proportionate Normalized LMS (PNLMS) algorithm is introduced. During the update process, a power normalization factor is introduced, and the step size is normalized by to suppress the influence of signal energy changes on convergence stability. At the same time, a diagonal gain matrix proportional to the current weight magnitude is introduced. The proportionalization idea increases the update magnitude of the main energy path and decreases the update of the secondary path, thereby achieving faster convergence speed and stronger sparse channel adaptability.

The weight increment expression for PNLMS is shown in Equation (38):

where is the regularization parameter to prevent numerical instability caused by the denominator approaching zero, is the step size factor for integer-order channels, and is the input signal power, which is used to normalize the step size. The expression for is shown in Equation (39).

where represents the current i-th weight component, and its absolute value is used to determine the size of the i-th diagonal element in the proportional gain matrix . represents all components in the weight vector and is used to calculate the normalization factor to achieve proportional adjustment of the step size allocation. Adding the increment to the weight vector from the previous time step can be written as:

Equation (26) is the result of the fractional derivative acting on the error. Substituting it into the basic expression for fractional weight update, , and using the same power normalization strategy as integer-order PNLMS, we obtain the fractional correction amount, as shown in Equation (41).

For ease of expression, intermediate variables can be defined as:

Then, the integer and fractional updates can be unified into a gradient superposition form. The FPNLMS algorithm achieves dual-channel updates of weights by simultaneously introducing integer-order PNLMS and fractional-order corrections. Its overall update formula is:

Further development as shown in Equation (44).

To balance fast convergence and steady-state performance, FPNLMS employs an adaptive step size design. The integer-order part is defined as:

The fractional step size is associated with through a scaling factor , as shown in Equation (46):

where G is as shown in Equation (47):

This factor decreases as the value of increases, reflecting the intuitive trend that the closer the fractional-order correction is to the integer order, the weaker the adjustment effect. Therefore, the core update mechanism of the FPNLMS algorithm ensures convergence stability through a power normalization term and enhances the algorithm’s tracking flexibility and steady-state performance through a fractional-order gradient term. Compared with the traditional LMS algorithm, FPNLMS exhibits faster convergence speed and stronger robustness in rapidly changing environments such as high-speed maglev channels.

5. Convergence Analysis of the FPNLMS Algorithm

To more systematically evaluate the convergence characteristics of the FLMS algorithm, this paper introduces an alternative reference framework to redefine and track the error evolution of the algorithm’s weight vector. Under this framework, the algorithm’s convergence behavior can be characterized by the weight deviation vector, as defined in Equation (48):

where represents the optimal weight vector that minimizes the mean square error (MSE) in a statistical sense. This optimal solution can maximize the gain of the desired signal while suppressing interference components. Based on the difference between the current weight vector and the optimal solution, the ideal error signal can be further defined, as shown in Equation (49):

Equation (49) defines as the ideal error based on the optimal weight , used to theoretically describe the error signal corresponding to the minimum mean square error (MSE), and used in the subsequent derivation of the bias vector and mean square convergence. The error signal used in the simulation (Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9) is , which is the actual error generated by the current weight, and its mean square value is used to calculate the instantaneous MSE. As the iteration proceeds, the actual error will gradually approach the ideal error , thus reflecting the mean square convergence characteristic of the algorithm.

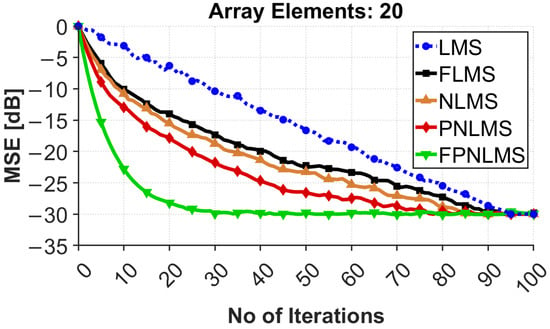

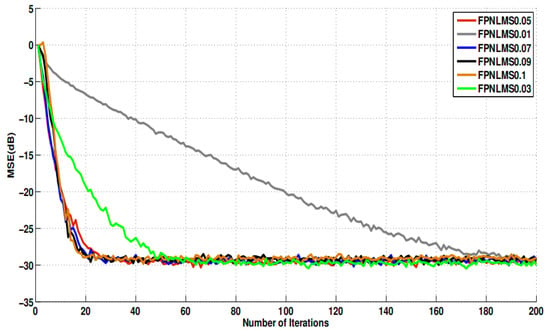

Figure 3.

MSE convergence comparison on a 20-element array.

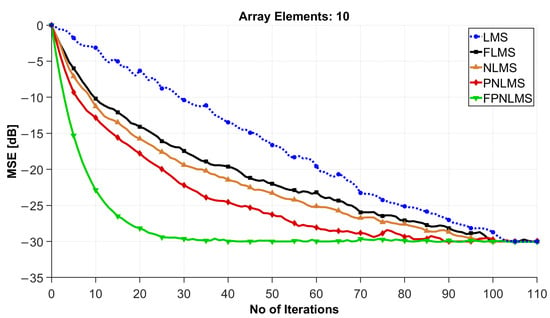

Figure 4.

MSE convergence comparison on a 10-element array.

Figure 5.

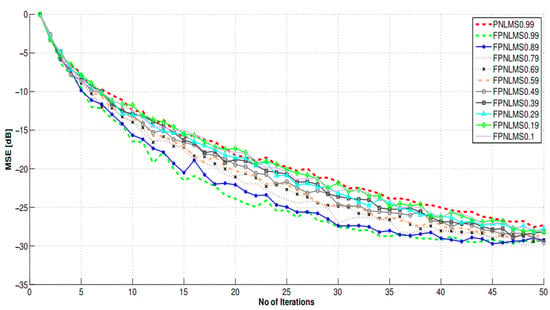

Convergence performance graphs of the FPNLMS algorithm at different fractional orders.

Figure 6.

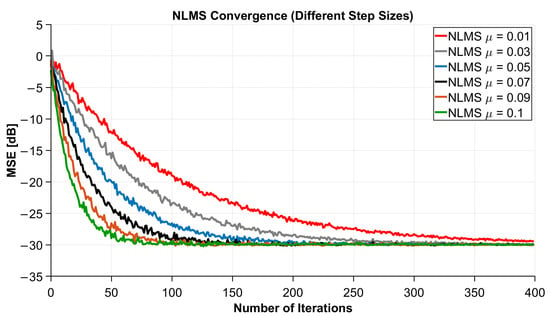

MSE Performance of NLMS for Varying Step Sizes.

Figure 7.

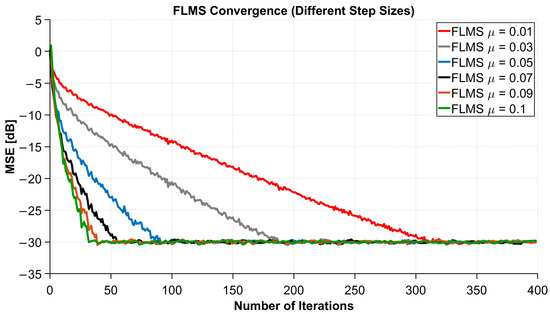

MSE Performance of FLMS for Varying Step Sizes.

Figure 8.

MSE Performance of PNLMS for Varying Step Sizes.

Figure 9.

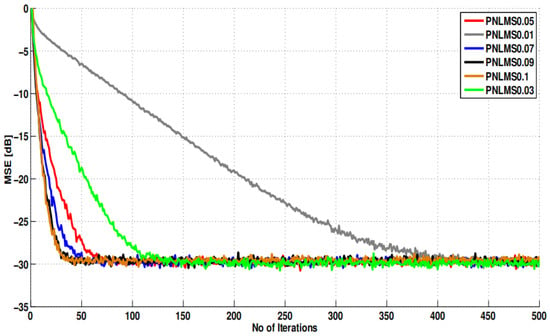

MSE Performance of FPNLMS for Varying Step Sizes.

Based on the weight update Formula (44) of the FPNLMS algorithm in Section 4, substituting the weight update into the definition of the deviation vector, we can obtain the result shown in Equation (50):

where represent the equivalent step size parameters after power normalization; is the gamma function, and is the order of the fractional derivative. This equivalent step size treatment allows the power normalization term to be absorbed into the update law, facilitating subsequent theoretical derivation. To avoid ambiguity in sign operations under complex signals, absolute value and sign function decomposition are used in fractional exponentiation. For further analysis, is defined, thus achieving a unified expression for integer and fractional step sizes.

To further analyze the mean square convergence behavior of the algorithm and establish the error propagation path at the theoretical level, the expectations of both sides of the weight update equation are taken simultaneously. Based on the statistical independence assumption (i.e., the input vector and the ideal error are independent in the sense of expectation), the key expectation terms in the update process can be expanded as follows, as shown in Equation (51):

where is the autocorrelation matrix of the input signal. Since , the mean of the integer-order channel is recursively obtained as . For the fractional-order channel, let (based on element-wise values), and use an approximation as shown in (52):

Thus, the corrected mean recursion is shown in Equation (53):

The mean convergence condition is that the spectral radius of the magnification matrix in the above equation is less than 1, i.e.,

where , represents the spectral radius, i.e., the modulus of the largest eigenvalue of the matrix. This equation is a strict criterion for the convergence of the FPNLMS algorithm. When the spectral radius is less than 1, the weight error will converge to zero in the mean sense, and the filter weight will approximate the optimal solution . Equation (54) not only covers the convergence characteristics of standard LMS and PNLMS, but also further introduces a fractional correction factor, providing a more general framework for the convergence analysis of adaptive filtering algorithms.

For ease of engineering implementation, Equation (54) can be approximated by the upper bound of the maximum eigenvalue:

Thus, we obtain a conservative but easily applicable sufficient condition:

where represents the largest eigenvalue of the matrix. Furthermore, under commonly used isotropic or steady-state approximations, we can let , , then Equation (56) simplifies to

This equation provides a clear upper bound for selecting the step size in the practical implementation of the FPNLMS algorithm, ensuring convergence under the combined effect of fractional-order correction and power normalization. As can be seen from Equation (57), the introduction of the fractional-order adjustment term effectively broadens the range of selectable step sizes, allowing the algorithm to maintain mean convergence even with larger step sizes. This characteristic is significant for fast convergence and highly dynamic signal environments. For example, in scenarios where the input signal power changes drastically or the characteristic spectrum is highly discrete, FPNLMS exhibits higher convergence stability and faster steady-state response speed compared to the traditional LMS algorithm.

Furthermore, due to the introduction of the power normalization term, the numerical adjustment of and no longer strictly depends on the instantaneous energy of the input signal, further improving the robustness of the algorithm in low signal-to-noise ratio or channel variation environments. The fractional-order operator, through the nonlinear combination of power and sign functions, effectively enhances the sensitivity to small-amplitude error signals, achieving a better trade-off between convergence speed and steady-state error.

Therefore, the upper bound of the step size shown in Equation (57) not only provides a rigorous theoretical guarantee for the stability of the algorithm, but also gives a clear constraint basis for parameter design in engineering implementation. In practical applications, as long as the step size meets this range, the FPNLMS algorithm can achieve low steady-state error while maintaining fast convergence, demonstrating superior convergence performance compared to the traditional LMS.

6. Simulation Results

The simulation experiments in this section are based on a ULA structure. The system array consists of L isotropic array elements, with the element spacing set to half the signal carrier wavelength, i.e., , to avoid spatial aliasing and satisfy the spatial sampling theorem. To analyze the impact of array size on algorithm performance, experiments were conducted with array configurations of and . The designed communication scenario simulates a typical BPSK signal transmission environment, where the desired signal (useful signal) is incident from the direction , and the interference signal arrives at the array front end from the direction . The system signal is simultaneously interfered with by AWGN signals to construct dynamic interference test conditions, thereby verifying the adaptive performance and robustness of various algorithms under complex channels. This paper selects five typical adaptive beamforming algorithms for comparative analysis, including the traditional LMS algorithm, NLMS algorithm, FLMS algorithm, PNLMS algorithm, and the FPNLMS algorithm proposed in this paper. Among them, the LMS algorithm serves as a performance baseline to evaluate the relative advantages of improved algorithms; the NLMS algorithm improves convergence stability by normalizing the input signal power; PNLMS improves convergence performance in sparse channels through a proportional weight update mechanism; and FLMS and FPNLMS further introduce fractional derivative operators to achieve higher dynamic sensitivity and steady-state accuracy through a non-integer order adjustment mechanism of historical gradients. The experiments use convergence speed, steady-state error, spatial filtering capability, and azimuth map consistency as core indicators to comprehensively evaluate the adaptability and performance of each algorithm in the high-speed maglev communication environment from both time and spatial domains.

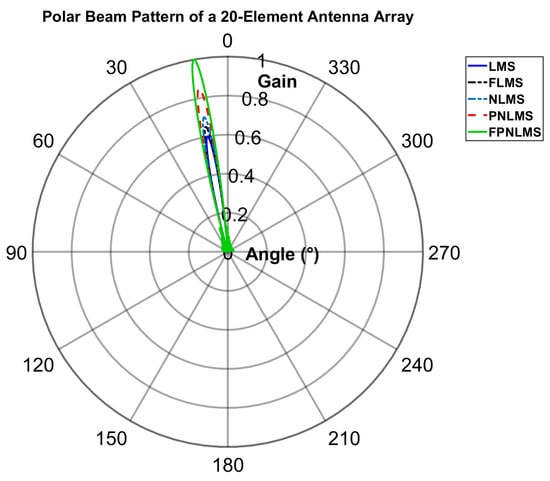

Simulation results are shown in Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13. This section mainly presents the simulation results of different adaptive beamforming algorithms under various array configurations and parameter conditions to compare their response characteristics in the time and spatial domains. Figure 3 and Figure 4 show the MSE convergence curves of different algorithms under 20-element and 10-element uniform linear arrays (ULA), respectively. Figure 5 shows the convergence performance variation of the FPNLMS algorithm under different fractional-order parameters . By adjusting the value, the trends of convergence speed and steady-state error can be observed, thus reflecting the influence of fractional-order parameters on the dynamic characteristics of the algorithm. Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9 show the MSE convergence performance of the NLMS, FLMS, PNLMS, and FPNLMS algorithms under different step size conditions, respectively, to compare the influence of step size changes on the convergence trend and steady-state error of the four algorithms. Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13, illustrate the beam patterns and polar coordinate distributions generated by each algorithm under 10-element and 20-element antenna array conditions. Using both rectangular and polar coordinates, the main lobe pointing, side lobe structure, and null distribution characteristics can be visually observed.

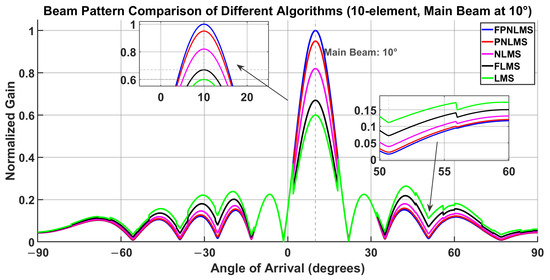

Figure 10.

Beam Patterns of a 10-Element Array Using Different Adaptive Algorithms.

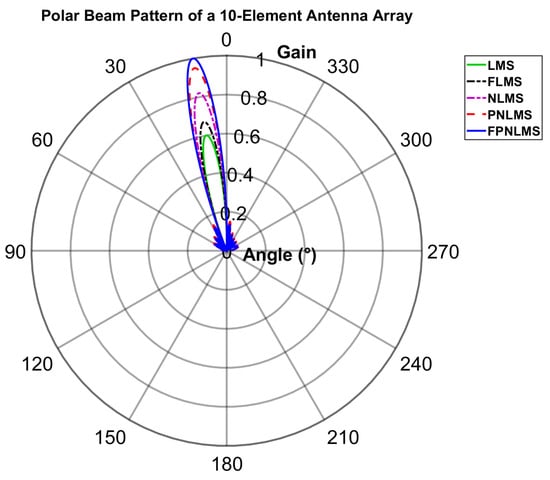

Figure 11.

Polar Patterns of a 10-Element Array Under Different Algorithms.

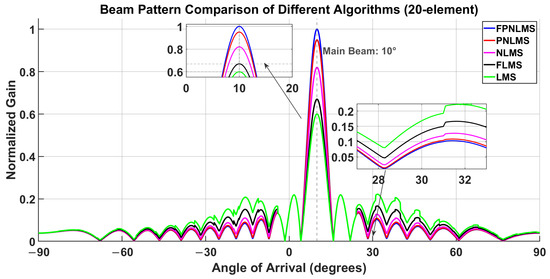

Figure 12.

Rectangular radiation patterns comparison for antenna elements of 20.

Figure 13.

Polar Patterns of a 10-Element Array Under Different Algorithms.

In addition to the above experiments, two supplementary evaluations were conducted to address reviewer suggestions:

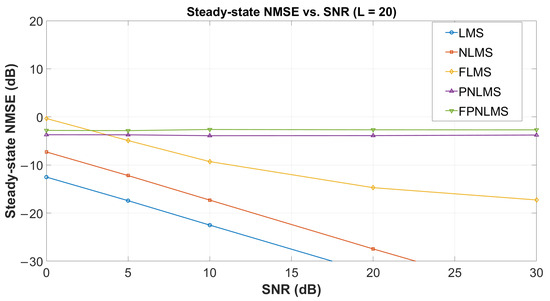

(1) Steady-state NMSE under different SNR conditions: A series of simulations were performed to compare the robustness of LMS, NLMS, FLMS, PNLMS, and FPNLMS under input SNR levels ranging from 0 to 30 dB. The results (Figure 14) show that FPNLMS consistently maintains lower NMSE across all SNR levels, demonstrating stronger noise resilience and steady-state precision.

Figure 14.

Comparison of Steady-State NMSE under Different SNR Conditions.

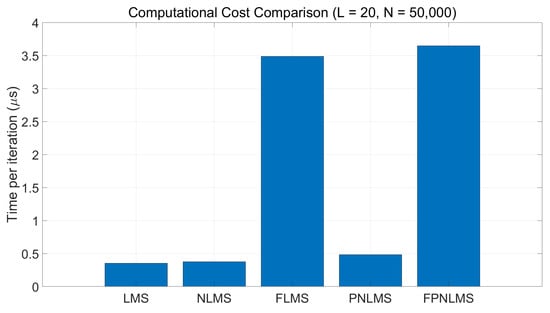

(2) Computational complexity evaluation: To assess real-time feasibility, the per-iteration computation time of the five algorithms was measured under identical conditions. The results (Figure 15) confirm that all LMS-type algorithms retain linear complexity, while FLMS and FPNLMS introduce only lightweight element-wise operations. FPNLMS achieves improved performance with only a marginal increase in computational cost, significantly lower than the complexity of RLS-type methods.

Figure 15.

Per-iteration computation time of the five adaptive algorithms.

6.1. Algorithm Convergence Performance and Steady-State Error Characteristics Analysis

6.1.1. When Array Elements: 20

In the simulation results shown in Figure 3, the system signal-to-noise ratio was set to 30 dB, the step size parameter was selected as (LMS baseline), and other algorithms were appropriately scaled, with the fractional order set to to construct a typical test environment with medium channel quality and medium-speed convergence requirements. Under this configuration, the mean square error (MSE) learning curves of five adaptive beamforming algorithms were compared and analyzed: LMS, NLMS, FLMS, PNLMS, and the FPNLMS algorithm proposed in this paper.

As clearly shown in the figure, the FPNLMS algorithm performs best in both convergence speed and steady-state accuracy. By the 18th iteration, FPNLMS’s MSE had rapidly decreased to dB, and it entered steady state after approximately 30 iterations, significantly faster than the other four algorithms. In contrast, PNLMS only approached this error level after approximately 60 iterations, and while FLMS was slightly better than PNLMS, it still lagged behind overall. NLMS and LMS converged the slowest, approaching the same steady-state error level after approximately 90 and 100 iterations, respectively.

To facilitate a quantitative comparison of the convergence efficiency of different algorithms, this paper uses the “number of iterations required to reach the set MSE threshold” as the convergence speed evaluation index, and calculates the relative speedup ratio between different algorithms accordingly. According to the results in Figure 3 and Figure 4, FPNLMS improves the convergence speed by approximately 57% and 82% compared to PNLMS and LMS, respectively. Compared to FLMS and NLMS, it also shows a significant convergence advantage, further verifying the effectiveness of fractional order and proportionalization mechanisms in accelerating convergence.

6.1.2. When Array Elements: 10

In the simulation test shown in Figure 4, to further evaluate the convergence, stability, and structural compatibility of the proposed algorithm under different array sizes, the number of array elements in the receiving array was reduced from 20 to 10 to simulate the array compression situation of maglev train communication equipment under conditions of limited space and tight power consumption budget. This round of testing maintained the same channel and algorithm parameter settings as in Figure 3 (signal-to-noise ratio 30 dB, step size , fractional order ), aiming to verify the performance retention capability of the fractional-order algorithm under array size reduction conditions.

Simulation results show that even with an array size reduced to 10, the FPNLMS algorithm maintains optimal convergence performance and steady-state accuracy. Around the 23rd iteration, the mean squared error (MSE) of FPNLMS decreases to approximately dB; in contrast, PNLMS and LMS require approximately 70 and 110 iterations, respectively, to reach similar error levels, representing convergence speed improvements of approximately 67% and 79%. At the same 23rd iteration, the instantaneous MSEs of FPNLMS, PNLMS, and LMS are approximately dB, dB, and dB, respectively. FPNLMS shows an improvement of approximately 4–5 dB in instantaneous error compared to PNLMS and approximately 19 dB compared to LMS. This indicates that FPNLMS still has significant advantages under low array element conditions.

Furthermore, even with the antenna array element count halved, PNLMS still exhibits a convergence advantage over LMS, reaching the stable region approximately 31 iterations earlier. This indicates that the power normalization mechanism, even with a lower-dimensional array, can still effectively improve the update weight of the main energy path, ensuring directional gain focusing capability. The introduction of the fractional-order mechanism further enhances the sensitivity to weak signal paths and the suppression of disturbances, demonstrating superior dynamic convergence performance compared to traditional LMS and PNLMS.

This characteristic of maintaining stability and efficient convergence under low array element count conditions is particularly important for high-speed maglev communication. Due to limited roof space and antenna quantity, the algorithm must possess strong adaptability and robustness to small-scale arrays. The results in Figure 4 show that FPNLMS can still achieve fast convergence and high-precision steady-state control under low array dimensions, providing reliable technical support for intelligent beam control in resource-constrained platform environments.

6.2. The Impact of Different Fractional Orders on the MSE Performance of FPNLMS

Figure 5 compares the FPNLMS learning curves for different fractional orders under fixed signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and step-size conditions, using PNLMS (denoted as “PNLMS-0.99” in the text) as the baseline reference without fractional-order correction. The simulation settings in this section follow the previous configuration: the signal-to-noise ratio is fixed at , the step-size parameter is set to (as the baseline value for all algorithms), and the default fractional order is . Under this setup, only the fractional order is varied to examine how changes in the fractional order affect the convergence speed and steady-state error of the algorithm.

As can be observed from the figure, the convergence speed of FPNLMS significantly increases with the increase of . When is in the range of to , the learning curve decreases slowly; when , the initial descent slope increases, and the required number of iterations decreases significantly. When approaches 1, the behavior of FPNLMS gradually approaches the limiting case of PNLMS. The “PNLMS-0.99” in the figure corresponds to the classic PNLMS (without fractional-order terms), while “FPNLMS-0.99” is formally close to the baseline, but because it still retains the fractional-order flexible adjustment mechanism, it is more flexible in terms of noise disturbance suppression and response to small changes. Meanwhile, when is in the range of to , the curve shows a lower or smoother MSE after reaching steady state, indicating that the fractional-order terms help improve steady-state error and later tracking stability without increasing computational complexity.

In summary, PNLMS provides the baseline convergence speed, while FPNLMS constructs a continuously controllable convergence spectrum from “slow convergence” to “fast locking” by adjusting . When the application scenario requires rapid locking of the main lobe direction or drastic channel changes, a larger (such as or ) is more suitable; while when a smoother later fine-tuning process is required, can be appropriately reduced to achieve a better balance between convergence speed and steady-state error.

6.3. Comparison of MSE Convergence Performance of Multiple Algorithms Under

6.3.1. NLMS

Figure 6 presents the MSE learning curves, which systematically illustrate the influence of the step-size parameter on both the convergence speed and the steady-state error of the NLMS algorithm. The simulation conditions in this section are consistent with the previous analysis: the signal-to-noise ratio is set to , the fractional-order parameter is fixed at , and is used as the baseline step size. Under this configuration, only the step-size parameter is varied to assess its impact on both the dynamic behavior and the steady-state performance of the algorithm. The simulation results clearly demonstrate that the step size directly shapes the characteristics of the convergence process, reflecting the inherent trade-off between convergence speed and steady-state accuracy.

When , convergence to a steady-state level of approximately dB is achieved in about 70 iterations, making it the fastest among the groups. Reducing the step size to increases the convergence time to 80–90 iterations. Further reductions to and require approximately 100–110 and 130–150 iterations, respectively, to reach the same steady-state error. When the step size decreases to , a significant “long tail” phenomenon appears, requiring approximately 200 iterations to reach steady state. At , convergence slows down, requiring approximately 320–360 iterations to reach approximately dB.

Furthermore, the MSE floor values of multiple curves at steady state are generally consistent (approximately dB). The differences between step sizes are mainly observed in the convergence transition phase: larger step sizes result in faster descent, but slightly amplify minor jitter in the steady-state segment; smaller step sizes lead to smoother convergence, but slower overall convergence speed. This indicates that smaller step sizes are more beneficial for steady-state accuracy and update smoothness, but less agile in dynamic response; larger step sizes, while accelerating initial convergence, may cause slight oscillations. In practical applications, a trade-off should be struck between the two to balance response speed and steady-state error performance.

For fast time-varying scenarios such as high-speed maglev communication, the selection of the step size parameter is particularly critical to balance real-time performance and steady-state performance. Referring to the curves shown in Figure 6, it can be seen that when the step size is in the range of to , the algorithm can significantly shorten the number of iterations required to converge to dB without degrading the steady-state error. Within this range, NLMS can better meet the real-time and reliability requirements of high-speed links.

In summary, the step size , as a core hyperparameter controlling the learning step size and weight update rate of NLMS, has a decisive impact on the actual performance of the algorithm. The convergence curve shown in Figure 6 provides a quantitative basis for subsequent parameter configuration.

6.3.2. FLMS

Figure 7 shows the MSE learning curves, which systematically characterize the effect of the step size parameter on the convergence speed and steady-state error of the FLMS algorithm. Similar to other adaptive algorithms, the step size directly determines the balance between convergence speed and steady-state accuracy.

Simulation results show that when the step size , the FLMS algorithm converges rapidly to a steady-state error level of approximately dB within about 20 iterations, exhibiting extremely fast dynamic response. When the step size is slightly reduced to , the number of iterations required for convergence increases to about 30, but the final steady-state error level remains consistent. Further reducing the step size to the range of to significantly slows the error descent slope, reaching stability at approximately 50 and 80 iterations, respectively. When the step size is reduced to , the convergence speed slows further, requiring approximately 150 iterations to reach steady state. Especially at , convergence exhibits a tailing effect, requiring approximately 320 iterations to reach the same error level, with the curve showing a clear “slow dive” characteristic.

Overall, a smaller step size results in a smoother weight update trajectory and smaller micro-oscillations in the steady-state region; however, this comes at the cost of slower convergence. Conversely, a larger step size accelerates convergence but may introduce slight fluctuations in the steady-state region. Therefore, the step size plays a crucial role in the FLMS algorithm, serving as a trade-off and optimization factor between convergence speed and steady-state accuracy.

In scenarios like high-speed maglev communication where channels change rapidly and real-time performance requirements are extremely high, appropriately increasing the step size (e.g., –) can shorten the convergence time without sacrificing steady-state error accuracy, thereby enhancing the algorithm’s tracking capability for time-varying channels and improving the stability of the communication link. In summary, the step size , as a key hyperparameter controlling the learning step size and weight update rate of the FLMS algorithm, has a decisive impact on its overall performance in engineering applications. The “step size–performance” relationship revealed in Figure 7 provides a reliable reference for subsequent parameter optimization and engineering implementation of adaptive beam control algorithms.

6.3.3. PNLMS

Figure 8 shows the MSE learning curves, which systematically characterize the adjustment of the step size parameter on the convergence speed and steady-state error of the PNLMS algorithm. The simulation results clearly show that the step size directly determines the algorithm’s convergence characteristics, essentially reflecting a balance mechanism between “convergence speed” and “steady-state accuracy.”

When the step size is set to , the PNLMS algorithm converges rapidly to a steady-state error of approximately dB in only about 32 iterations, demonstrating extremely fast response speed. Slightly reducing the step size to , although the final steady-state error remains the same, increases the number of iterations required for convergence to approximately 35. Further reducing the step size to and further decreases the convergence speed, significantly delaying the time required to reach steady state. Especially at , the convergence process slows markedly, requiring approximately 377 iterations to reach the same MSE level, verifying the significant decrease in algorithm responsiveness when the step size is reduced.

This trend indicates that while a smaller step size can lead to a smoother weight update process and may improve steady-state accuracy to some extent, it reduces the algorithm’s dynamic response speed, making it difficult for the system to track rapidly changing channel conditions in a timely manner. Conversely, an excessively large step size, while potentially accelerating convergence, may introduce oscillations and even affect steady-state stability. Therefore, the step size plays a crucial regulatory role in the PNLMS algorithm, requiring a reasonable trade-off between accuracy and speed.

In high-speed maglev communication applications, due to the dominance of the main path energy and sparse reflection paths, channel variations are often very rapid, and even slight deviations in beam direction can lead to noticeable signal attenuation. In this highly dynamic environment, the algorithm must possess strong tracking capability and error tolerance. Simulation results show that appropriately increasing the step size (e.g., –) can improve convergence speed without sacrificing steady-state error accuracy, thus better meeting the engineering requirements of real-time performance and reliability for maglev train communication links.

In summary, the step size , as a core hyperparameter controlling the learning step size and weight update rate of the PNLMS algorithm, plays a decisive role in the algorithm’s performance in practical systems. The “step size–performance” relationship revealed in Figure 8 not only provides a quantitative reference for parameter selection but also offers important configuration guidance for the design of adaptive beam control algorithms in high-speed maglev vehicle-to-ground communication systems.

6.3.4. FPNLMS

Figure 9 shows the MSE learning curve, which clearly reveals the direct impact of the step size parameter on the performance of the FPNLMS algorithm, especially exhibiting a significant regularity in the trade-off between convergence speed control and steady-state error adjustment. This experiment aims to investigate the influence of different step size settings on the dynamic convergence behavior of the FPNLMS algorithm and provide a strategic reference for step size optimization in practical deployments.

Simulation results show that when the step size is set to , the FPNLMS algorithm can rapidly reduce the MSE to approximately dB in only about 19 iterations, demonstrating extremely fast response speed. In contrast, when the step size is slightly reduced to , the number of iterations required to reach the same error level increases to approximately 22, and the convergence speed decreases slightly. This trend is more pronounced under smaller step sizes. For example, when the step size decreases to , the algorithm requires approximately 192 iterations to converge to a similar steady-state error level, and the convergence rate is significantly reduced.

This trend validates the classic trade-off between step size setting and algorithm convergence characteristics: a larger step size can enhance weight updates in the early learning phase and improve convergence speed, but an excessively large step size may lead to increased oscillations and decreased error accuracy in the steady-state phase; meanwhile, a smaller step size is beneficial for improving the final steady-state performance, but the learning process slows down, response lags, and system adjustment delay increases. For high-speed mobile scenarios that require rapid adaptation to channel changes, an overly small step size may fail to meet the system’s requirement for millisecond-level directional updates.

In high-speed maglev environments, communication systems must cope with the complex propagation characteristics of extremely strong channel directivity, very few reflection paths, and rapid energy drift in the main path. Any beam pointing deviation or algorithm response delay can cause attenuation of the main signal gain. Therefore, beam control algorithms must not only possess high-precision error adjustment capabilities but also maintain fast and stable convergence under highly dynamic conditions. The experimental results in Figure 9 show that when the step size is set in the range of –, the FPNLMS algorithm can simultaneously achieve fast convergence and low steady-state error, providing an optimal parameter selection range for engineering applications.

In summary, step size parameter optimization in the FPNLMS algorithm should fully consider the intensity of dynamic channel changes, real-time constraints, and error tolerance requirements. In high-speed maglev vehicle-to-ground communication systems, it is recommended to dynamically adjust the step size using a combination of offline tuning and online adaptive mechanisms to better accommodate the time-varying characteristics of the channel, thereby further improving system stability and robustness.

6.4. Beam Pattern and Polar Coordinate Characteristics Analysis

Figure 10 shows the beam patterns generated by five adaptive algorithms (LMS, NLMS, FLMS, PNLMS, and FPNLMS) to evaluate their differences in main-lobe directional control, side-lobe suppression, and interference suppression performance. The experiment uses a uniform linear array (ULA) with 10 elements, a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of 30 dB, a step size of , and a fractional-order parameter of . The steady-state weight vector obtained after the 25th iteration is used as the basis for plotting the beam patterns. The 10-element array structure is chosen to maintain a relatively wide main lobe, thereby allowing for a clearer observation of the performance differences among different algorithms in terms of main-lobe focusing capability and side-lobe structure.

As shown in Figure 10, all five algorithms can form a clear and concentrated main lobe in the target direction (approximately ). To quantitatively evaluate the main-lobe preservation capability, this paper uses the deviation between the main-lobe peak direction and the desired direction as the pointing accuracy indicator. The results show that this deviation for each algorithm is controlled within , indicating that all algorithms can accurately lock the expected direction in terms of main-lobe pointing. However, significant differences still exist among the algorithms in terms of main-lobe sharpness and sidelobe suppression effectiveness.

Overall, the LMS algorithm exhibits the lowest main-lobe gain and the highest sidelobe level, resulting in the weakest spatial focusing ability. NLMS and FLMS show some improvement over LMS, but their main lobes remain slightly diffuse, and their sidelobe energy suppression is insufficient. PNLMS, due to its proportional weight update mechanism, produces a more concentrated main lobe and significantly lower sidelobe levels, especially around the interference direction (approximately ), demonstrating stronger interference suppression capability.

To further quantify interference suppression, this paper uses the radiation pattern amplitude at the interference direction as an evaluation metric and compares it with the sidelobe level of LMS as a reference. As shown in the magnified sidelobe area on the right of Figure 10, near the interference direction, the sidelobe level of FPNLMS decreases by approximately 4–6 dB compared with LMS, corresponding to a reduction in interference leakage power of about 60–. In summary, FPNLMS performs the best among the five algorithms in terms of main-lobe preservation, sidelobe suppression, and interference rejection, demonstrating superior spatial filtering capability and directional resolution.

To further verify the orientation preservation and main-lobe focusing abilities of each algorithm in the angular domain, Figure 11 shows the polar-coordinate beam patterns under the same parameter conditions as Figure 10. As can be seen, the main lobes formed by all five algorithms accurately point to the target direction of approximately , indicating good orientation consistency. Regarding main-lobe gain distribution, FPNLMS exhibits the most concentrated main lobe and the highest peak gain (approximately ). PNLMS ranks second, with a peak gain of approximately , followed by NLMS and FLMS with gains of about and , respectively. LMS has the lowest main-lobe gain of approximately . This gain ranking is consistent with the results observed in Figure 10, further confirming that FPNLMS provides the best spatial focusing performance, orientation preservation, and enhancement capability.

Furthermore, the overall polar pattern reveals that FPNLMS produces a more symmetrical beam, with significantly lower sidelobe energy than the other algorithms and a smoother overall radiation distribution. In undesirable directional regions (e.g., 50–), FPNLMS exhibits a slightly lower beam level than the other four algorithms, indicating better sidelobe suppression and contributing to the reduction of interference signals arriving from unwanted directions.

In summary, under the same signal-to-noise ratio and step size settings, FPNLMS outperforms the other four algorithms in main-lobe focusing intensity, sidelobe suppression, and overall pattern symmetry. This algorithm not only achieves fast and stable weight convergence but also demonstrates superior overall performance in spatial selectivity and directional gain, validating its engineering feasibility and superiority in array signal processing and highly directional wireless communication scenarios.

Figure 12 shows the beam patterns generated by different adaptive algorithms (LMS, NLMS, FLMS, PNLMS, and FPNLMS) under the condition of a 20-element uniform linear array (ULA), used to analyze the impact of array size expansion on spatial resolution and beamforming performance. The simulations follow the same conditions as described previously, with dB, step size , fractional-order parameter , and the steady-state weights obtained after the 25th iteration used to plot the beam pattern. Compared with a 10-element array, increasing the number of elements significantly improves spatial resolution, resulting in a narrower and sharper main lobe and further enhanced beam directivity. Meanwhile, due to the increased array aperture, the sidelobe structure exhibits a denser and more regular distribution, providing a more intuitive basis for comparing the differences in sidelobe suppression and direction-keeping capabilities among the different algorithms.

As shown in the figure, the LMS algorithm has the lowest main-lobe gain, the weakest sidelobe suppression capability, and the poorest overall directivity performance. Although NLMS and FLMS outperform LMS in terms of convergence characteristics, they still exhibit significant sidelobe energy leakage. PNLMS, relying on its proportional normalization update mechanism, further enhances the main-lobe gain in the target direction and significantly reduces the sidelobe level compared with LMS.

In contrast, FPNLMS performs best in main-lobe focusing, sidelobe suppression, and directivity preservation. Its main lobe is the sharpest, its overall sidelobe energy is the lowest, and it forms a deeper sidelobe trough near the interference direction (approximately ). As seen in the magnified region on the right side of the figure, the trough depth of FPNLMS at this angle is approximately 8 dB lower than that of LMS, indicating a stronger suppression capability in the interference direction.

In summary, as the array size increases, the radiation pattern structure of each algorithm becomes more pronounced. However, FPNLMS maintains optimal directional resolution and interference suppression performance even under large-array conditions, demonstrating its engineering advantages in highly directional communication and array signal processing applications.

Figure 12 shows the beam patterns generated by different adaptive algorithms (LMS, NLMS, FLMS, PNLMS, and FPNLMS) under the condition of a 20-element uniform linear array (ULA), used to evaluate the impact of array size expansion on beam convergence performance and spatial filtering characteristics. The simulation parameters are set to dB, step size , and fractional-order parameter , with the weight vector of the 25th iteration used as the steady-state result. Compared with a 10-element array, increasing the number of elements significantly improves the array’s spatial resolution and beam-pointing accuracy, resulting in a narrower and sharper main lobe and a clearer and more structured sidelobe distribution.

As shown in the figure, the LMS algorithm exhibits the lowest main-lobe gain, the weakest sidelobe suppression, and overall poor directivity. Although NLMS and FLMS outperform LMS in terms of convergence speed, they still suffer from noticeable sidelobe energy leakage. PNLMS improves the main-lobe gain significantly through its proportional normalization update mechanism, resulting in a marked reduction in sidelobe levels compared with LMS. FPNLMS, on the other hand, demonstrates the strongest main-lobe focusing and sidelobe suppression capabilities, exhibiting the highest main-lobe directivity, the lowest sidelobe energy, and forming a deep null near the interference direction (approximately ). The null depth of FPNLMS at this angle increases by approximately 6–8 dB relative to LMS, indicating stronger spatial filtering selectivity and greater sensitivity in null formation.

Figure 13 shows the polar-coordinate beam patterns under the same parameter settings, providing a more intuitive illustration of the spatial angular-domain beamforming characteristics of each adaptive algorithm. As can be seen, the main lobes formed by all five algorithms stably point to approximately , consistent with the desired direction, demonstrating good robustness in direction preservation. However, significant differences remain in main-lobe gain and focusing capability: FPNLMS exhibits the highest main-lobe amplitude (approximately ), followed by PNLMS (approximately ); NLMS and FLMS show main-lobe gains of about and , respectively; and LMS has the lowest, only about . These differences reflect the varying spatial focusing abilities and signal enhancement performance of the algorithms.

With the increase in the number of array elements, the main lobe becomes narrower and sharper, the sidelobe energy is significantly reduced, and the symmetry and null depth of the beam pattern are improved. Under these higher-resolution conditions, FPNLMS still maintains optimal sidelobe suppression and interference direction null depth, demonstrating stronger spatial filtering capability and directional resolution performance, and verifying its engineering advantages and applicability in large-array, high-resolution scenarios.

Of particular note is that the FPNLMS algorithm exhibits the most concentrated main-lobe structure, significantly lower and smoother sidelobes, and deeper null locations in the polar-coordinate pattern, demonstrating its comprehensive advantages in spatial resolution and anti-interference performance. In contrast, while PNLMS also possesses strong sidelobe suppression capabilities, it is slightly inferior to FPNLMS in terms of main-lobe focusing and sidelobe smoothness; NLMS and FLMS show only moderate performance in overall directivity preservation, sidelobe control, and null depth.

In summary, when the number of array elements increases from 10 to 20, the spatial filtering performance of the array is significantly improved, including further narrowing of the main lobe, enhanced directivity, and improved sidelobe suppression. Under these conditions, FPNLMS maintains the best performance in key indicators such as main-lobe focusing, sidelobe suppression, and null formation. It not only ensures fast and stable weight convergence, but also exhibits higher spatial selectivity and direction-preservation capability, validating its good scalability and engineering application value in large-scale array systems.

6.5. Steady-State NMSE Performance Under Different SNR Conditions

To evaluate the steady-state performance of each adaptive algorithm under different noise environments, this section compares the normalized mean square error (NMSE) performance of LMS, NLMS, FLMS, PNLMS, and the proposed FPNLMS under various input SNR conditions. Figure 14 shows the steady-state NMSE curves of each algorithm in the SNR range of 0–30 dB under the condition of a uniform linear array with .

The following patterns can be observed from Figure 14. First, both LMS and NLMS exhibit an NMSE curve that decreases approximately linearly with increasing SNR. NLMS consistently outperforms LMS under various SNR conditions, which is consistent with the fact that its normalization mechanism effectively suppresses update instability caused by input amplitude variations. Although both algorithms show a significant decreasing trend in steady-state error, some residual error remains in the high-SNR region due to inherent algorithmic limitations.

In contrast, the steady-state NMSE of FLMS is significantly higher than that of LMS and NLMS, and its variation with SNR is more gradual. This is mainly because the fractional-order gain may introduce additional jitter in the steady-state region, limiting its ability to reduce error in noise-dominated conditions. This phenomenon is consistent with conclusions reported in existing research on fractional-order adaptive filtering.

For PNLMS, its steady-state NMSE remains low and relatively stable across the entire SNR range. Because its scaling factor enables a more reasonable allocation of weight updates across different components, PNLMS exhibits better noise robustness during the steady-state phase, leading to the near-horizontal curve.

The proposed FPNLMS exhibits slightly better steady-state performance than PNLMS under all SNR conditions. By combining the proportional normalization mechanism with a lightweight fractional-order correction term, the algorithm not only retains the steady-state robustness of PNLMS but also further reduces residual errors caused by small-amplitude noise interference. It is worth noting that the steady-state error of FPNLMS in the figure does not reach overly idealized values, which is consistent with the rational setting of the algorithm’s gain factor discussed earlier and is closer to the achievable performance of real array systems in the presence of noise and quantization effects.

In summary, FPNLMS achieves a favorable balance between performance and computational complexity under different SNR conditions. Compared with FLMS, which also incorporates fractional-order operators, FPNLMS shows a significant advantage in steady-state performance; compared with LMS and NLMS, it achieves lower steady-state NMSE across low, medium, and high SNR regions; and compared with PNLMS, the proposed method maintains robustness while achieving additional performance improvement. Therefore, FPNLMS has higher practical value in scenarios characterized by large noise fluctuations or complex channel conditions.

6.6. Computational Complexity and Practical Implementation Feasibility

We analyze the per-iteration computational complexity and memory footprint of the five adaptive algorithms considered in this work—LMS, NLMS, FLMS, PNLMS, and FPNLMS—and contrast them with representative prior arts.

Let L denote the number of adaptive beamforming weights. Each iteration of the algorithms includes output computation , error update , and coefficient update. The computational complexity is summarized below.