Abstract

Network function virtualization (NFV) is an emerging technology that is gaining popularity for network function migration. NFV converts a network function from a dedicated hardware device into a virtual network function (VNF), thereby improving the agility of network services and reducing management costs. A complex network service can be expressed as a service function chain (SFC) request, which consists of an ordered sequence of VNFs. Given the inherent heterogeneity and dynamic nature of network services, effective SFC deployment encounters significant unpredictable challenges. Machine learning-based methods offer the flexibility to predict and select the optimal next action based on existing data models. In this paper, we propose a deep reinforcement learning-based approach for bandwidth-aware service function chaining (DRL-BSFC). Aiming to simultaneously improve the acceptance ratio of SFC requests and maximize the total revenue for Internet service providers, DRL-BSFC integrates a graph convolutional network (GCN) for feature extraction of the underlying physical network, a sequence-to-sequence (Seq2Seq) model for capturing the order information of an SFC request, and a modified A3C (Asynchronous Advantage Actor–Critic) algorithm of deep reinforcement learning. To ensure efficient resource utilization and a higher acceptance ratio of SFC requests, the bandwidth cost for deploying an SFC is explicitly incorporated into the A3C’s reward function. The effectiveness and superiority of DRL-BSFC compared to the existing DRL-SFCP scheme are demonstrated via simulations. The performance measures include the acceptance ratio of SFC requests, the average bandwidth cost, the average remaining link bandwidth, and the average revenue-to-cost ratio under different SFC request arrival rates.

1. Introduction

According to the Ericsson Mobility Report [1], the number of global 5G (fifth-generation) subscriptions is growing rapidly and reached close to 2.9 billion globally at the end of 2025, accounting for one-third of all mobile subscriptions at that time. The number of 4G (fourth-generation) subscriptions is continually declining as subscribers migrate to 5G. Global 5G subscriptions are forecast to reach 6.4 billion in 2031 and will make up two-thirds of all mobile subscriptions. This growth trend not only reflects the significant increase in the number of 5G mobile devices but also shows that people depend heavily on network quality, diversified applications, and a personalized service experience. As 5G-enabled applications gradually become a reality, including network slicing, edge computing, and real-time video transmission, physical network architectures are facing demands for greater flexibility, resource allocation, and real-time response capabilities. Given the different quality of service (QoS) requirements of various applications, network management systems must be capable of dynamically adjusting traffic-handling strategies. For instance, high-definition video and cloud gaming depend on traffic acceleration and guaranteed QoS, while industrial control and remote medical services need extremely low latency and highly secure transmission. These applications are driving modern network infrastructures toward requiring flexible deployment capabilities. However, traditional physical network architectures based on proprietary hardware commonly suffer from limitations such as insufficient flexibility, difficult resource allocation, and no scalability, making them unable to meet the high agility and flexibility demands of emerging application scenarios.

With the extensive development of network function virtualization (NFV) technology, network infrastructures are moving towards softwareization, which has promoted the rapid growth of applications such as video streaming, cloud services, and the Internet of Things (IoT) and has greatly improved the elasticity and scalability of network services. NFV significantly enhances network resource utilization and configuration flexibility by transforming traditional hardware-dependent network functions into a combination of flexibly deployable virtual network functions (VNFs). However, as application scenarios become more diverse and complex, the challenge of effectively connecting these distributed VNFs has become a critical issue affecting network service availability and scheduling capabilities. On the other hand, software-defined networking (SDN) technology is commonly used to support NFV architectures. SDN decouples the control and data planes, allowing for centralized, programmable network management. This enables network operators to dynamically configure services based on application requirements. The controller of SDN allows the virtually linked VNFs, which are placed in a physically distributed manner, to create flexible and scalable network services. According to a survey by Market Growth Reports [2], the global SDN and NFV technology in Telecommunication Network Transformation Market was valued over USD 44.78 billion in 2025 and is projected to reach USD 71.87 billion in 2026, steadily progressing to USD 242.21 billion by 2035, with a strong CAGR of 16.4% for the period spanning 2025 to 2035. This growth highlights the trend towards flexible, programmable, and virtualized network architectures.

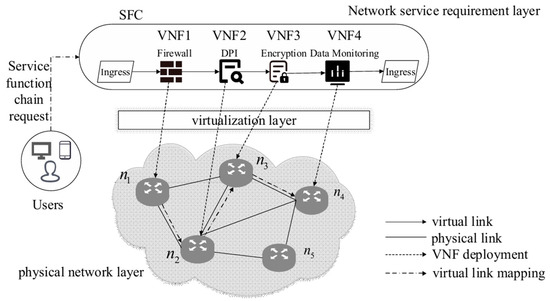

With the integration of NFV and SDN technologies, service function chaining (SFC) has become a key architectural design for enabling flexible network services. Through SDN’s control mechanisms, SFC can dynamically chain multiple VNFs in a logical sequence based on different application requirements, thereby deploying complex end-to-end network service flows. According to RFC 7665 [3], a standard defined by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), this framework explicitly defines the logical components, encapsulation format, and traffic-steering mechanisms for SFC, providing a universal framework to support the creation and deployment of SFC. Through this standardized design, the SFC architecture can effectively enhance the flexibility and adaptability of network resource allocation to meet diverse and rapidly changing network service demands. As shown in Figure 1, the system architecture for SFC deployment is composed of three layers: a network service requirement layer, a virtualization layer, and a physical network layer [4]. On the network service requirement layer, a user submits an SFC request that includes multiple VNFs, such as a firewall, deep packet inspection (DPI), and an encryption module. These VNFs are then connected via virtual links to form a service flow with a specific processing order. The virtualization layer is responsible for monitoring the dynamical status of the physical network layer and mapping the VNF nodes and virtual links to the underlying physical nodes and links. The physical network layer, which provides the resources required for the VNFs to operate, consists of multiple physical nodes with computational and other capabilities and physical links with transmission capabilities. The core problem of SFC deployment is how to map a series of VNFs to the corresponding physical servers and connect them sequentially via physical links. Therefore, the selection of physical nodes and links that can satisfy the resource requirements of each VNF of an SFC request is crucially important to SFC deployment, as the network performance of NFV-enabled technology largely depends on this process.

Figure 1.

The system architecture for SFC deployment.

Successful SFC deployment hinges on the effective utilization of physical resources, requiring a consideration of the computational, memory, and storage capacities of the nodes, alongside the available bandwidth resources of the links. Physical resources, however, are unevenly distributed and limited within the network topology. Consequently, the complexity of SFC deployment is exacerbated by a vast combination of VNF length, service type, and specific ordering requirements for an SFC. Several authors have proposed mathematical optimization methods to obtain the optimal solution for SFC deployment [5,6]; however, this is an NP-hard problem [7,8]. These methods suffer from high computational complexity, making it difficult to find the optimal solution in large-scale networks. As a result, numerous approximation algorithms with non-exponential time complexity have been proposed to solve the aforementioned SFC deployment problem [9,10]. Yet, these algorithms cannot guarantee optimal performance, and in some cases, an approximation of the optimal solution may not even exist. Additionally, some heuristic or meta-heuristic algorithms have appeared in the literature [11,12], which attempt to find an acceptable solution in a short time, assuming that the arrival time of SFC requests and resource requirements are known in advance. In reality, the solutions found using heuristic or meta-heuristic methods are likely to be locally optimal and probably far from the true global optimum. Although heuristic or meta-heuristic algorithms can reduce computational complexity and quickly find an SFC deployment solution, they tend to converge to local optima and, by necessity, rely on manual parameter tuning [13]. Consequently, real-time deployment of SFC requests on a physical network with limited resources remains a challenge.

Recently, artificial intelligence (AI) has been widely applied in various fields. To meet the demands of an increasing number of service types and network scales, machine learning-based SFC deployment methods that can handle network heterogeneity and dynamics have been proposed. Specifically, several studies have effectively addressed the SFC deployment problem from various perspectives using deep reinforcement learning (DRL) [14,15]. In an NFV environment, a new SFC request may be unprecedented. Instead of requiring extensive prior data for training, DRL-based approaches learn from rich past experience, continuously maximizing a predefined reward function until reaching convergence, thereby adapting to a new network state. Previous studies [16,17,18] have focused on using DRL-based methods to complete SFC deployment in a real-time manner. However, the reward functions in these DRL-based algorithms for SFC deployment primarily consider only the resources required by the SFC request itself. They often fail to account for the bandwidth consumed by the path between the nodes where the new and previous VNFs are placed. This neglect can waste link bandwidth resources in the physical network. In view of this, this study proposes a deep reinforcement learning-based approach for bandwidth-aware service function chaining (DRL-BSFC). The main contributions of DRL-BSFC are as follows: it designs a modified A3C (Asynchronous Advantage Actor–Critic) algorithm [19,20] for deep reinforcement learning, which also integrates a graph convolutional network (GCN) for feature extraction of the underlying physical network [21] and a sequence-to-sequence (Seq2Seq) model [22] for capturing the order information of an SFC request. Aiming to simultaneously improve the acceptance ratio of SFC requests and maximize the total revenue for Internet service providers (ISPs), the bandwidth cost for deploying an SFC is explicitly incorporated into the A3C’s reward function. By reducing the extra link bandwidth resources consumed by deploying an SFC, DRL-BSFC provides more remaining bandwidth for subsequent SFC requests. Consequently, this can reduce the deployment failures caused by insufficient bandwidth resources and increase the probability of successful SFC deployment.

2. Related Work

To confront the expanding network scale and diverse network service requirements, DRL-based methods, through neural network architectures for parameter training and policy optimization, possess higher generalizability. In recent years, several SFC deployment schemes using DRL have been proposed. Tian et al. [23] proposed a DRL-based two-stage SFC deployment approach (DTS-SFC) to complete SFC deployment within a given latency constraint, thereby improving the acceptance ratio of SFCs. In the first stage, the DTS-SFC method considers both computational and bandwidth resources simultaneously to find candidate paths under the latency constraint; subsequently, a DRL-based heuristic algorithm is proposed to determine the placement of each VNF, simultaneously considering SFC demands and path resources. Notably, VNF movements are utilized by DTS-SFC to define the dimensions of the action space, allowing the DRL agent to make effective decisions for improving the acceptance ratio of SFCs and average node utilization. However, the running time of the DTS-SFC method is relatively long. The authors in [24] proposed a deep hierarchical reinforcement learning method named HRL-ACRA (Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning with Admission Control and Resource Allocation) for the placement of VNFs with no consideration of virtual links. HRL-ACRA is capable of simultaneously learning admission control and resource allocation for VNF placement. The entire VNF embedding process of HRL-ACRA is decomposed into an upper-level policy and a lower-level policy. The upper level decides whether to accept the incoming VNF request, and the lower level then allocates physical node resources for the accepted VNF request. In order to avoid embedding failure, HRL-ACRA attempts not to map too many VNFs to the physical nodes. Although the upper-level admission control for VNF requests ensures the VNF’s QoS, it relatively reduces the full utilization of network resources. Cao et al. [25] presented a method combining a GCN for extracting physical network features with a Seq2Seq model to design a set of methods for dynamically embedding VNFs into the physical network through deep reinforcement learning. The drawbacks are that only one resource type is considered and no virtual links among VNFs exist. The authors of [26] proposed the Transformer-based Deep Reinforcement Learning with Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (TDRL-DDPG) method. TDRL-DDPG aims to handle the deployment of VNF forwarding graphs, where a key distinction from other VNF placements is the formation of a randomly connected graph between VNFs, instead of a linear chain. The reward function of TDRL-DDPG considers both the acceptance ratio of service requests and energy consumption to enhance resource utilization and energy-saving performance. Similarly, TDRL-DDPG only considers a single resource type, which is less consistent with the multi-resource constraints in actual networks.

Furthermore, the schemes proposed in [27,28] both combine a GCN for extracting physical network features, a Seq2Seq model for capturing the order information of an SFC request, and a DRL-based SFC deployment method to meet diverse network service requirements, aiming at maximizing the DRL’s long-term average revenue. Regarding the two schemes, DRL-SFCP (Deep Reinforcement Learning for Service Functions Chain Placement) [27] considers the corresponding performance of past decisions rather than a hypothetical environment, utilizes a Seq2Seq model to capture the ordered information of an SFC request, and defines the total resources used by the successfully deployed SFCs as the reward function of the A3C algorithm. DRL-D (Online Service Function Chain Deployment via Deep Reinforcement Learning) [28] investigates a trade-off between pursuing high long-term average revenue and making decisions in an online manner. By utilizing the strengths of the GCN in learning network features, DRL-D integrates a heuristic algorithm and a new prioritized experience replay technique to optimize the DRL framework and reduce the time complexity.

Among the aforementioned DRL-based approaches for SFC deployment, DRL-SFCP is the most similar to the DRL-BSFC proposed in this paper, regardless of the system architecture or the number of resource types used. In addition to considering three resource types on a physical node, CPU, RAM, and ROM, DRL-BSFC defines the bandwidth cost for deploying an SFC, which is incorporated into the modified A3C’s reward function. Therefore, in Section 4, DRL-BSFC will be compared with DRL-SFCP through simulations to verify the effectiveness and superiority of DRL-BSFC.

3. The Proposed DRL-BSFC

Firstly, to make the following descriptions easier to read, the key notations we will use throughout the paper are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Notations and descriptions.

3.1. Physical Network Architecture

Let a physical network be represented as a weighted undirected graph, denoted as Gp. Gp = (Np, Lp), where Gp consists of a set of physical nodes (denoted as Np) and a set of physical links (denoted as Lp). Let K denote the number of resource types on each physical node and k denote the resource type, where k = 1 indicates CPU resource, k = 2 indicates RAM resource, and k = 3 indicates ROM resource. In our proposed DRL-BSFC mechanism, K is set to be 3. For each physical node np in Np, the remaining resources of K types are denoted by a list , , and the maximum resources of K types are denoted by a list , . For each physical link lp in Lp, its remaining and maximum bandwidths are denoted as and , respectively. The capacity for each of the network resources (CPU, RAM, ROM, and link bandwidth) is quantified into units.

3.2. Service Function Chaining

Let the v-th SFC request be denoted as Gv. Gv = (Nv, Lv) is a weighted directed chain-like graph, where v represents the index of SFC. Gv consists of a set of VNFs (denoted as Nv) and a set of virtual links (denoted as Lv). As Gv is a chain-like graph, |Lv| equals |Nv| minus one. For each virtual node nv in Nv, the resource requests for K types are denoted by a list ,. For each virtual link lv in Lv, its bandwidth resource request is denoted as . For example, an SFC request with |Nv| = 4 indicates that SFC v is composed of four VNFs and three virtual links. Each VNF has a CPU resource request, a RAM resource request, and a ROM resource request, and each virtual link between two logically adjacent VNFs has a bandwidth resource requirement. The service function chaining involves attempting to map Gv onto Gp under certain constraints, such as those on node resource, bandwidth resource, duplicate placement, and placement order. The details of this are described below.

(a) Node resource constraints

The remaining resource of type k for physical node np () must be larger than or equal to the total amount of required resource of type k when nv is mapped to np. That is,

where is 1 if nv is mapped to np, and 0 otherwise.

(b) Bandwidth resource constraints

The remaining bandwidth for physical link lp () must be larger than or equal to the total amount of required bandwidth when lv is mapped to lp. That is,

where is 1 if lv is mapped to lp; and 0 otherwise.

(c) Duplicate placement constraints

Each VNF node nv of SFC v can only be placed on a physical node. That is,

(d) Placement order constraints

The path for deploying Gv onto Gp must pass through each placed nv according to the sequence specified by Gv, adhering to the flow conservation constraint [29]. That is,

In Equation (4), In(np) and Out(np) denote the set of incoming and outgoing links of physical node np, respectively.

In other words, for successful SFC deployment, the same number of physical nodes will be placed with |Nv| VNFs sequentially but the number of physical links to chain these VNFs will be larger than or equal to |Lv|. This means that the total hop count of the physical path for successfully placing two logically adjacent VNFs is probably larger than one.

3.3. Reward Functions

Similar to DRL-SFCP, which is described previously in Section 2, our proposed DRL-BSFC integrates a GCN for feature extraction of the underlying physical network, a Seq2Seq model for capturing the order information of an SFC request, and a modified A3C algorithm using deep reinforcement learning. To ensure efficient resource utilization and a higher acceptance ratio of SFC requests, the total path bandwidth for deploying an SFC is explicitly incorporated into the modified A3C’s reward function.

Prior to defining the reward function in the modified A3C algorithm of DRL-BSFC, we first explain the concepts of placement bandwidth for the j-th VNF (denoted as ) and bandwidth cost for successfully deploying the v-th SFC (denoted as Cb(v)), which are expressed by Equations (5) and (6), respectively. In Equation (5), the total bandwidth used by placing the j-th VNF of SFC v on a certain physical node is expressed as the virtual link bandwidth () multiplied by the total hop count of the path chaining two logically adjacent VNFs (j − 1) and j on the physical network (denoted as ). The bandwidth cost is defined as the total amount of extra bandwidth used by successfully placing all VNFs of SFC v. Because the so-called “cost” refers to the extra bandwidth incurred by the deployed path with one or more hops between two logically adjacent VNFs, the bandwidth cost of placing the j-th VNF is multiplied by . Therefore, as expressed by Equation (6), the bandwidth cost for successfully deploying SFC v is the sum of VNF j’s placing bandwidth cost for every j in {1, 2, 3, …, |Nv|}. Notably, is zero since the first VNF has no virtual links.

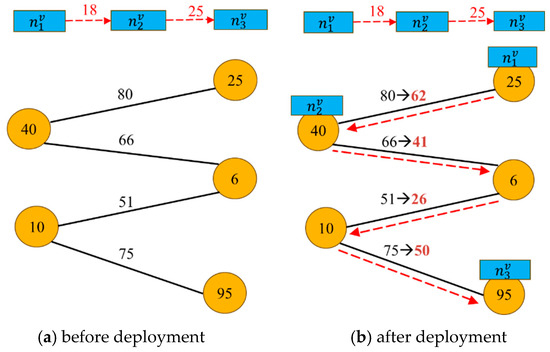

Figure 2 shows a simple example illustrating the placement bandwidth of VNF j and the bandwidth cost of deploying SFC v. In Figure 2, the yellow nodes represent physical nodes, and the numbers within the physical nodes represent their individual IDs. The black solid lines represent physical links, and the black numbers over the physical links indicate their individual remaining bandwidth resources. A blue rectangle represents a VNF of SFC v. The red dashed directed lines are virtual links, and the red numbers over the virtual links indicate the requested bandwidth resources. To simply illustrate how Lv is mapped to Lp, it is assumed that the remaining resource for each physical node is enough to place the corresponding VNF. Figure 2a shows the remaining bandwidth of each physical link before deploying SFC v. Specifically, the remaining bandwidth of the physical link between yellow nodes 25 and 40 is 80 units; between nodes 40 and 6, it is 66 units; between nodes 6 and 10, it is 51 units; and between nodes 10 and 95, it is 75 units. In addition, the v-th SFC request arrives with |Nv| = 3 and |Lv| = 2. rep resents the j-th VNF of SFC v, where j belongs to {1, 2, 3}. Let denote the virtual link between virtual nodes 1 and 2. is always zero, and is the requested bandwidth of 18 units for the virtual link between virtual nodes 1 and 2. Similarly, is the requested bandwidth of 25 units for the virtual link between virtual nodes 2 and 3. Figure 2b shows the successful deployment of SFC v, in which , , and are mapped to the physical nodes 25, 40, and 95, respectively, and the remaining bandwidth resources of the physical links are indicated by the dark red numbers, which are obtained by subtracting the requested bandwidth from the remaining bandwidth on the selected links in Figure 2a. By referring to Equation (6), we can obtain the bandwidth cost for successfully deploying SFC v, as follows:

Figure 2.

An example of link bandwidth used by SFC deployment.

The design of the reward function is divided into two parts. The first part is the reward obtained during the deployment process by placing the j-th VNF, which we designate as the placement reward, denoted as , as expressed by Equation (8). In Equation (8), wp is a positive coefficient representing the weight of the placement bandwidth of a VNF. Clearly, the placement reward is inversely proportional to the placement bandwidth (), which implies the cost for placing the j-th VNF. In contrast to the other rvnf(j)’s, rvnf(1) is defined as the reciprocal of |Nv| because is zero. The probability of successfully completing the placement of all VNFs decreases as the length of SFC v increases. Consequently, the reward associated with successfully placing the first VNF is defined as the reciprocal of |Nv|. The second part is obtained when all VNFs (indexed from 1 to |Nv|) of SFC v are successfully placed, indicating that the deployment of SFC v is successful. As expressed by Equation (9), it is referred to as the deployment reward, denoted as . In Equation (9), ws is a positive coefficient representing the weight of the reciprocal of the bandwidth cost, and wf is a negative coefficient representing the penalty if the deployment process fails at the j*-th VNF. In addition, as the bandwidth cost increases, the incentive for successful deployment of SFC v decreases. When j* is larger, the negative reward will be greater. This design attempts to avoid placement failures, especially when the SFC is about to be successfully deployed.

Finally, the total reward after the deployment of SFC v is formulated by Equation (10), which is used to find the deploying strategy that can maximize the long-term average reward. The long-term average reward with a strategy π, denoted as R(π), can be represented by Equation (11).

where denotes the set of SFC requests that arrive before τ and tv represents the arrival time of SFC v. The use of τ approaching infinity indicates that our desired outcome is long-term average performance, not short-term performance. As expressed in Equation (12), the objective of DRL-based methods is to find a strategy that maximizes the long-term average reward, denoted as π*—that is, to continuously adjust π by updating the A3C’s parameters, so that the strategy with the maximum long-term average reward R(π) is found.

As previously stated, the aim of our proposed DRL-BSFC is not only to improve the acceptance ratio of SFCs but also to maximize the total revenue for ISPs. Let Trevenue, which is expressed as in Equation (13), be the sum of the requested resources of all successfully deployed SFCs. If an SFC fails at the placement of VNF j*, the previously placed node and link resources for every VNF j (j < j*) will be excluded in Trevenue, and the resources allocated during the deployment process will be released. That is, only the successful deployment of SFC v is counted in Trevenue. On the other hand, Tcost, which is expressed as in Equation (14), is the sum of the physical network resources consumed by all successfully deployed SFCs. By calculating the revenue-to-cost ratio, denoted as Trc, we can determine how much profit per unit of cost is for ISPs.

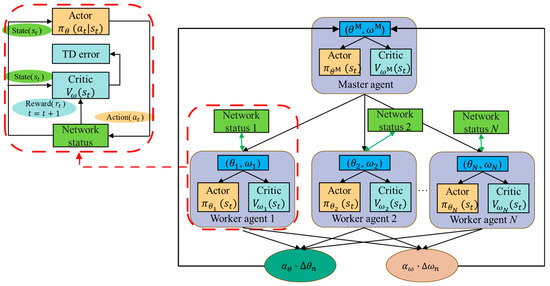

3.4. The Modified A3C Algorithm

Figure 3 illustrates the A3C’s training diagram in the proposed DRL-BSFC. Apart from using the reward functions defined in Section 3.3, the entire training model is the same as the original A3C algorithm [19,20]. The right side of Figure 3 shows the A3C architecture, utilizing a master–worker (i.e., client–server) framework. The uppermost is the master agent, which is responsible for maintaining the global actor parameter θM and the global critic parameter ωM. Also, the strategy with the maximum long-term average reward R(π), which is defined by Equations (10) and (11) in Section 3.3, for deploying SFC v is decided by the master agent. The bottom of Figure 3 shows N worker agents, which are independent of each other. Each worker agent indexed by n (}) has its own network status, actor parameter θn, and critic parameter ωn. As highlighted in the red dashed box in the upper left part of Figure 3, a worker agent interacts with its respective network status to generate and collect the sample data (st, at, rt, st+1) for updating θn and ωn, where t (}) is used to indicate the order of VNFs for SFC v. The process of generating and collecting the sample data (st, at, rt, st+1) is detailed below.

Figure 3.

Training diagram of the A3C algorithm.

(a) Firstly, the network status is organized as a feature matrix st, and then st is input into the critic and actor neural networks. The critic function is used to evaluate the expected value of the cumulative discounted reward Gt under the current deploying strategy.

(b) The actor function represents the probability distribution of each executable action at given st. Then, the actor selects the physical node corresponding to at with the greatest probability to place the t-th VNF of SFC v.

(c) According to Equations (8) and (9), the reward rt is obtained. Then, the network state st is updated to st+1. During the process of placing the t-th VNF, ; when the last VNF is successfully placed onto the physical node corresponding to aT, , where T is |Nv|.

(d) For the critic function, is updated to .

(e) With and , the temporal difference (TD) error is calculated and used to estimate the advantage function (denoted as ), which is primarily used for updating θM and ωM.

4. Performance Evaluation

4.1. Simulation Settings

As summarized in Table 2, the physical network used to perform simulations includes 100 nodes and 500 links, in which the 500 links are randomly located between 2 of the 100 nodes following the Waxman topology model [30] with α = 0.5 and β = 0.2. CPU, RAM, and ROM resources of each physical node all uniformly distributed from 50 to 100 units, and the bandwidth resource of each physical link has the same distribution. The simulation platform is VMware with the Ubuntu operating system and the simulator is named Virne [31], which was also used by the authors of the existing DRL-SFCP scheme [27]. Our simulations are run on a single computer with Intel Core i7-11370H CPU and 16GB RAM. In addition, the values of A3C’s parameters are summarized in Table 3.

Table 2.

Parameter Settings for the physical network.

Table 3.

Parameter settings for A3C.

4.2. Results and Discussion

Two simulation scenarios for 1000 SFC requests are established. One is the same as that used in the existing DRL-SFCP scheme, and the other is a scenario with limited network bandwidth resource. All the performance measures are obtained by averaging the simulation results of 20 episodes. The performance measures include the acceptance ratio of SFC requests (denoted as Ar), the average bandwidth cost of deploying SFC v (Cb (v)), the average remaining link bandwidth (denoted as RLb), the total revenue (Trevenue), the total cost (Tcost), and the revenue-to-cost ratio (Trc).

4.2.1. Scenario I

The parameters of SFC requests have the same values as the previously proposed DRL-SFCP. In each episode, 1000 SFC requests arrive sequentially at the system according to a Poisson process with an average arrival rate of 20 every 100 units of time. Each SFC request has a lifetime exponentially distributed with an average of 400 units of time. The length of each SFC (i.e., the number of VNFs) varies from 2 to 5 according to a uniform distribution. The resource requests for CPU, RAM, and ROM, and link bandwidth for a VNF follow a uniform distribution ranging from 2 to 30 units.

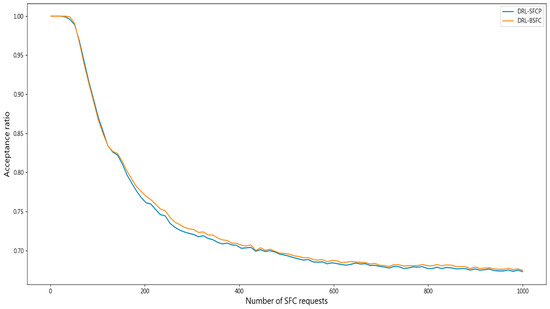

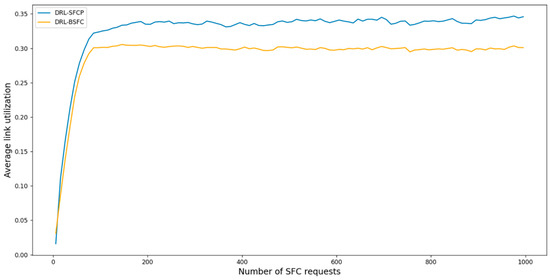

Figure 4 shows the acceptance ratios of SFCs with DRL-BSFC and DRL-SFCP, which are plotted by yellow and blue lines, respectively. It is observed that the acceptance ratio with DRF-BSFC is almost the same as that for DRL-SFCP. This is because the average link utilization with DRL-SFCP is around 0.34 and the average link utilization with DRL-BSFC is lower than that with DRL-SFCP, owing to taking into account the bandwidth cost, as shown in Figure 5. It is very interesting that the average link utilization for either of the two approaches is always no more than 34%, which indicates that 66% of the bandwidth resource in the system is still available. This means that the bandwidth resource is quite abundant, allowing for easy identification of available physical paths connecting two logically adjacent VNFs. Therefore, the acceptance ratios with DRL-BSFC and DRL-SFCP are nearly the same. However, if there is a lack of bandwidth resource, DRL-SFCP may encounter difficulties in successfully deploying SFCs. Addressing this drawback, the proposed DRL-BSFC mitigates bandwidth scarcity by reducing the extra bandwidth resource occupied by the successfully deployed SFCs.

Figure 4.

Acceptance ratio versus the number of SFC requests.

Figure 5.

Average link utilization versus the number of SFC requests.

4.2.2. Scenario II

To create a bandwidth-scarce environment, 60 SFC requests are introduced before the beginning of each episode to establish so-called “background SFCs” in the system. For the background SFCs, each has eight VNFs, and the resource requests for CPU/RAM/ROM and link bandwidth for a VNF are fixed at 2 and 15, respectively. In total, the background SFCs occupy approximately 35% of the bandwidth resource over the duration of an episode. By referring to the parameter settings of SFC requests in [24], we let 1000 SFC requests arrive sequentially at the system according to a Poisson process with average arrival rates of 4, 6, and 8 every 100 units of time, indicating light, medium, and heavy loads, respectively. Each SFC request has a lifetime exponentially distributed with an average of 1000 units of time. Similar to Scenario I, the length of each SFC (i.e., the number of VNFs) also varies from 2 to 5 according to a uniform distribution. The resource requests for CPU, RAM, and ROM, and link bandwidth for a VNF also follow a uniform distribution ranging from 2 to 30 units.

As shown in Table 4, with an average arrival rate of 4 SFCs per 100 time units, both DRL-SFCP and DRL-BSFC have relatively sufficient remaining link bandwidth resources (denoted as RLb) and good acceptance ratios (denoted as Ar). That is, all of the node and link resources are very abundant for SFC deployment under light load conditions. However, Table 4 shows that the total revenue-to-cost ratios for these two DRL-based methods have a difference of approximately 3%. As shown in Table 5, with an average arrival rate of 6 SFCs per 100 time units, DRL-BSFC has more remaining link bandwidth than DRL-SFCP by saving bandwidth occupied by the successfully deployed SFCs, and the SFC acceptance ratios with these two methods differ by nearly 4%. As for the average bandwidth cost (Cb(v)) for successfully deploying an SFC, DRL-SFCP uses an extra 299.5 units of bandwidth on average. In contrast, our proposed DRL-BSFC uses only an extra 238.1 units of bandwidth. This represents a great improvement of approximately 20.5% in the bandwidth cost compared to DRL-SFCP. Additionally, Table 5 shows that the total revenue-to-cost ratio of DRL-BSFC is over 5% higher than that of DRL-SFCP. Briefly, as the number of SFC requests increases, the performance improvement of DRL-BSFC relative to DRL-SFCP becomes increasingly significant in terms of the acceptance ratio of SFC requests, the average bandwidth cost, and the revenue-to-cost ratio under medium load conditions. For an average arrival rate of 8 SFCs per 100 time units, Table 6 shows that DRL-SFCP requires an extra 281.4 units of bandwidth resource to successfully deploy an SFC on average, while DRL-BSFC requires only 273.7 units of bandwidth resource. As shown in Table 6, the total revenue-to-cost ratios for these two DRL-based methods become nearly the same for ISPs, with a difference of only 1%. Under heavy load conditions, the performance difference between DRL-BSFC and DRL-SFCP becomes less significant because all of the node and link resources are more limited. Although the resource scarcity leads to subsequent SFC deployment failure, the performance measures with DRL-BSFC, including those we referred to previously, are still slightly better than those with DRL-SFCP.

Table 4.

Performance comparison under light load conditions.

Table 5.

Performance comparison under medium load conditions.

Table 6.

Performance comparison under heavy load conditions.

5. Conclusions

Aiming to simultaneously improve the acceptance ratio of SFC requests and maximize the total revenue for Internet service providers, this study proposes a DRL-BSFC approach for the inherent heterogeneity and dynamic nature of network services. Since the existing DRL-based SFC deployment methods generally overlook the issue of bandwidth resource consumption, we propose a DRL-based approach for bandwidth-aware service function chaining (DRL-BSFC). DRL-BSFC integrates a GCN for feature extraction of the underlying physical network, a Seq2Seq model for capturing the order information of an SFC request, and a modified A3C algorithm that incorporates the bandwidth cost for deploying an SFC into the reward function. The modified A3C algorithm automatically learns during the training process to prioritize the selection of physical nodes with lower bandwidth consumption, thereby avoiding additional bandwidth resource occupation caused by improper deployment. The simulation results demonstrate that DRL-BSFC can effectively reduce bandwidth costs under different network loads (various arrival rates, requested resources, and SFC lengths) and simultaneously improve the acceptance ratio of SFC requests. In addition, DRL-BSFC can continuously maintain larger remaining bandwidth resource, thereby mitigating the risk of subsequent SFC deployment failure due to insufficient bandwidth. This not only helps promote the long-term development of the network infrastructure but also creates greater economic benefits for ISPs. In the future, we are going to extend the proposed DRL-BSFC model to cope with heterogeneous network environment and energy consumption management, with an aim to enhance the automated management capabilities and overall performance of next-generation networks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.-J.W. and W.-S.H.; methodology, Y.-J.W., S.-H.H., M.-H.C. and W.-S.H.; software, S.-H.H. and M.-H.C.; validation, S.-H.H. and M.-H.C.; formal analysis, Y.-J.W. and S.-H.H.; investigation, Y.-J.W., S.-H.H. and M.-H.C.; resources, Y.-J.W. and W.-S.H.; data curation, S.-H.H.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.-J.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.-J.W. and W.-S.H.; visualization, Y.-J.W. and S.-H.H.; supervision, Y.-J.W. and W.-S.H.; project administration, Y.-J.W. and W.-S.H.; funding acquisition, Y.-J.W. and W.-S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science and Technology Council in Taiwan under grant number NSTC 113-2221-E-992-001, NSTC 113-2221-E-158-001, and the APC was funded by NSTC 114-2221-E-992-001.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments, which helped improve the quality of this paper. We also thank MDPI Author Services for helping us improve the English writing quality.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ericsson Subscriptions Outlook. Available online: https://www.ericsson.com/en/reports-and-papers/mobility-report/dataforecasts/mobile-subscriptions-outlook (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- SDN and NFV Technology in Telecom Network Transformation Market Overview. Available online: https://www.marketgrowthreports.com/market-reports/sdn-and-nfv-technology-in-telecom-network-transformation-market-104266 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- RFC 7665. Available online: https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc7665 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Wang, Y.; Chen, Z. Online Service Function Chain Deployment Method Based on Advantage Actor-Critic Learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Digital Society and Intelligent Systems, Chengdu, China, 10–12 November 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tomassilli, A.; Giroire, F.; Huin, N.; Perennes, S. Provably Efficient Algorithms for Placement of Service Function Chains with Ordering Constraints. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2018, Honolulu, HI, USA, 16–19 April 2018; pp. 774–782. [Google Scholar]

- Addis, B.; Belabed, D.; Bouet, M.; Secci, S. Virtual network functions placement and routing optimization. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 4th International Conference on Cloud Networking, Niagara Falls, ON, Canada, 5–7 October 2015; pp. 171–177. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, R.; Lewin-Eytan, L.; Naor, J.S.; Raz, D. Near Optimal Placement of Virtual Network Functions. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2015, Hong Kong, China, 26 April–1 May 2015; pp. 1346–1354. [Google Scholar]

- Rost, M.; Schmid, S. On the Hardness and Inapproximability of Virtual Network Embeddings. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 2020, 28, 791–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, I.; Suh, D.; Pack, S.; Dán, G. Joint Optimization of Service Function Placement and Flow Distribution for Service Function Chaining. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2017, 35, 2532–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Chen, X.; An, W.; Peng, Y.; Cao, J.; Zhang, Y. Multiple Service Function Chaining under Load Balance in SDN/NFV Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE 28th PIMRC, Montreal, QC, Canada, 8–13 October 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Luizelli, M.C.; da Costa Cordeiro, W.L.; Buriol, L.S.; Gaspary, L.P. A Fix-and-Optimize Approach for Efficient and Large Scale Virtual Network Function Placement and Chaining. Comput. Commun. 2017, 102, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Wen, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Lee, T. Toward Profit-Seeking Virtual Network Embedding Algorithm via Global Resource Capacity. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2014, Toronto, ON, Canada, 27 April–2 May 2014; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Cui, L.; Tso, F.P.; Li, Z.; Jia, W. Dapper: Deploying Service Function Chains in the Programmable Data Plane Via Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2023, 16, 2532–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbey, N.E.; Ayad, S.; Benhaya, B. Review on Reinforcement Learning-based Approaches for Service Function Chain Deployment in 5G Networks. In Proceedings of the 2022 2nd International Conference on New Technologies of Information and Communication, Mila, Algeria, 21–22 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Yang, L. A Survey of Service Function Chain Orchestration Based on Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 98th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2023-Fall), Hong Kong, China, 10–13 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Z.; Ge, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, L.; Li, T. Automatic Virtual Network Embedding: A Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach with Graph Convolutional Networks. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2020, 38, 1040–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Hong, P.; Pan, M.; Liu, J.; Zhou, J. Optimal VNF Placement via Deep Reinforcement Learning in SDN/NFV-Enabled Networks. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2020, 38, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PQuang, T.A.; Hadjadj-Aoul, Y.; Outtagarts, A. Evolutionary Actor-Multi-Critic Model for VNF-FG Embedding. In Proceedings of the IEEE 17th Annual Consumer Communications & Networking Conference, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 10–13 January 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- A3C. Available online: https://zh.wikipedia.org/zh-tw/A3C (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Chen, L.; Gu, Q.; Jiang, K.; Zhao, L. A3C-Based and Dependency-Aware Computation Offloading and Service Caching in Digital Twin Edge Networks. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 57564–57573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Pan, S.; Chen, F.; Long, G.; Zhang, C.; Yu, P.S. A Comprehensive Survey on Graph Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 32, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seq2Seq Model. Available online: https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/machine-learning/seq2seq-model-in-machine-learning/ (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Tian, A.; Feng, B.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Yu, S.; Zhang, H. DRL-Based Two-Stage SFC Deployment Approach Under Latency Constraints. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2024, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20–20 May 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Shen, L.; Fan, Q.; Xu, T.; Liu, T.; Xiong, H. Joint Admission Control and Resource Allocation of Virtual Network Embedding via Hierarchical Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2024, 17, 1001–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Wu, S.; Aujla, G.S.; Wang, Q.; Yang, L.; Zhu, H. Dynamic Embedding and Quality of Service-Driven Adjustment for Cloud Networks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 16, 1406–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahraoui, R.; Houidi, O.; Bannour, F. Energy-Aware VNF-FG Placement with Transformer-based Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Network Operations and Management Symposium, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 6–10 May 2024; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Fan, Q.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Xiong, Q.; Fu, S.; Gao, M. DRL-SFCP: Adaptive Service Function Chains Placement with Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Communications, Montreal, QC, Canada, 14–23 June 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Q.; Pan, P.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Wen, J. DRL-D: Revenue-Aware Online Service Function Chain Deployment via Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2022, 19, 4531–4545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.; Rahman, M.R.; Boutaba, R. ViNEYard: Virtual Network Embedding Algorithms With Coordinated Node and Link Mapping. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 2012, 20, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waxman, B.M. Routing of multipoint connections. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 1988, 6, 1617–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virne. Available online: https://github.com/GeminiLight/virne/blob/main/resources/pdfs/virne_benchmark_paper.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.