Abstract

Automatic modulation classification (AMC) under low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and complex channel conditions remains a significant challenge due to the trade-off between robustness and efficiency. This study proposes a lightweight temporal convolutional network (TCN) and Mamba fusion architecture designed to enhance modulation recognition performance. In the modulation signal denoising stage, a non-local adaptive thresholding denoising module (NATM) is introduced to explicitly improve the effective signal-to-noise ratio. In the parallel feature extraction stage, TCN captures local symbol-level dependencies, while Mamba models long-range temporal relationships. In the output stage, their outputs are integrated through additive layer-wise fusion, which prevents parameter explosion. Experiments were conducted on the RadioML 2016.10A, 2016.10B, and 2018.01A datasets with leakage-controlled partitioning strategies including GroupKFold and Leave-One-SNR-Out cross-validation. The proposed method achieves up to a 3.8 dB gain in the required signal-to-noise ratio at 90 percent accuracy compared with state-of-the-art baselines, while maintaining a substantially lower parameter count and reduced inference latency. The denoising module provides clear robustness improvements under low signal-to-noise ratio conditions, particularly below −8 dB. The results show that the proposed network strikes a balance between accuracy and efficiency, highlighting its application potential in real-time wireless receivers under resource constraints.

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of modern wireless communications, spectrum scarcity has become a pressing issue, meaning fast and reliable signal identification has become increasingly important for ensuring communication security and efficiency. AMC, as a key technology in intelligent receivers, is widely applied in spectrum monitoring, interference detection, and signal demodulation [1,2,3]. However, practical wireless environments often involve low SNRs, multipath fading, and co-channel interference, which severely degrade recognition performance. Traditional likelihood-based and handcrafted feature approaches rely heavily on accurate channel estimation and compensation, making them unsuitable for dynamic and noisy scenarios where real-time response is required [1].

With the availability of large-scale labeled communication datasets, deep learning has gradually become the mainstream solution for AMC [2,3]. Existing models typically transform raw IQ signals into alternative representations such as spectrograms, amplitude–phase vectors, or normalized complex sequences, and then employ CNNs, RNNs, ResNet variants, or hybrid architectures [4,5,6,7,8]. CNNs are effective at extracting localized symbol patterns, while RNNs capture sequential correlations [3]. More recently, attention mechanisms and lightweight architectures [6,9,10] have been introduced to improve robustness and real-time applicability [6,9]. However, despite these advances, most approaches remain limited by local receptive fields or fixed input windows, which restrict their ability to capture long-range symbol dependencies [11], especially in dynamic and noisy environments typical of real-world wireless communication systems [8]. Moreover, many methods lack explicit mechanisms for noise suppression before feature extraction, which severely hampers reliability under low-SNR conditions [12].

To overcome these limitations, Transformer-based models have been investigated for AMC. Cai et al. [11] first applied the Transformer for global sequence modeling, while Ma et al. combined it with CNN to jointly exploit global and local features. However, the quadratic complexity of self-attention imposes prohibitive computational cost for resource-constrained receivers [13]. To address this issue, Zhang et al. [14] proposed MAMC, a state-space model that achieves linear-time global modeling, but its reliance on recurrence weakens the extraction of fine-grained local details. Xiao et al. [15] employed TCNs to strengthen local temporal pattern learning, yet their performance can still degrade in strong-noise environments due to the lack of explicit denoising. Taken together, these studies suggest that a practical AMC framework must simultaneously meet three communication-oriented requirements: (i) robustness to low-SNR interference to ensure reliable detection, (ii) effective integration of local and global features to capture both symbol-level and packet-level dependencies, and (iii) lightweight design for real-time implementation on constrained devices [7,16,17].

Motivated by these requirements, we propose a lightweight AMC framework that integrates noise suppression, local feature extraction, and long-range dependency modeling into a unified design. The NATM selectively enhances the relevant signal components under noisy conditions [18]. The TCN branch captures short-range temporal patterns, while the Mamba state-space branch efficiently models long-range dependencies with linear complexity [19,20]. Importantly, these branches are fused in parallel through an additive fusion strategy, which prevents parameter growth associated with concatenation and facilitates complementary feature learning [19]. This unified architecture maintains compactness while ensuring robustness across a wide range of SNR conditions.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- We propose a unified lightweight AMC framework that addresses the challenges of low-SNR robustness, local feature extraction, and global dependency modeling in a single design, improving performance in both noisy environments and real-time applications.

- The NATM is introduced to enhance effective SNR, significantly improving robustness under low-SNR conditions where traditional methods struggle.

- A parallel dual-branch architecture integrates TCN and Mamba modules, effectively balancing local symbol-level feature extraction and global long-range dependency modeling.

In addition, extensive experiments on the RadioML 2016.10A/B and 2018.01A datasets validate the effectiveness and efficiency of the proposed framework.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related work on TCN-based sequence modeling and state-space architectures such as Mamba. Section 3 presents the proposed lightweight AMC framework, including the NATM denoising module, the parallel TCN–Mamba feature extractor, and the classification design. Section 3.3.1 describes the datasets, evaluation protocols, and experimental settings. Section 4 reports the performance comparison, efficiency analysis, ablation studies, and further evaluations under different SNR conditions. Section 5 provides an in-depth discussion of the results, and Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

2.1. Temporal Convolutional Networks (TCN)

Temporal Convolutional Networks (TCNs) [8] are widely used in sequence modeling due to their causal structure and dilated convolutions, which efficiently capture local temporal dependencies. In AMC, TCN-based methods typically focus on extracting symbol-level temporal features such as pulse shapes and short-range correlations. Prior studies improve TCN performance by deepening the network, modifying dilation configurations, or integrating attention modules [7,16]. Although these approaches enhance local feature extraction, they largely emphasize short-range modeling, and their effectiveness in capturing long-range dependencies or handling complex noise conditions remains limited.

2.2. Mamba and State-Space Models

State-space models (SSMs) have gained growing interest for long-range temporal modeling in lightweight architectures. Recent selective SSMs, such as Mamba, achieve linear-time computation while capturing global sequence dynamics, demonstrating strong performance in speech and general time-series tasks. In AMC and related signal-processing applications, SSM-based models are explored as efficient global sequence learners and are often compared with recurrent and attention-based architectures. Existing research primarily investigates their ability to model long-context temporal patterns and their computational advantages in resource-constrained environments. Additional studies on SSMs and long-range sequence modeling [14,21] further highlight the relevance of such architectures for communication signals.

2.3. Denoising and Robust AMC

Improving AMC robustness under low-SNR conditions has long been a key research focus. Traditional approaches employ filtering or time–frequency denoising techniques, though their performance degrades when noise characteristics vary. Deep-learning-based denoising strategies introduce feature-domain suppression, adaptive thresholding [22], and autoencoder-based front-end denoisers to mitigate noise while preserving modulation features. Recent trends emphasize learning noise-aware representations within the classifier to improve robustness across varying SNRs. Studies in noise-resilient RF classification [23,24] further highlight the importance of integrated denoising mechanisms for reliable AMC.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Problem Formulation

In a single-input single-output (SISO) communication system, the transmitted signal passes through the wireless channel and is observed at the receiver as

where and denote the transmitted and received signals in the continuous-time domain, respectively. represents the time-varying channel fading function (also referred to as the channel impulse response), and is the additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN). The variable t denotes the continuous time, and is the channel propagation delay.

After passing through the analog-to-digital converter (ADC), the received signal is sampled to obtain the discrete sequence:

where n is the discrete-time index and L is the sampling length. The discrete signal is expressed in complex form, whose real and imaginary parts correspond to the in-phase (I) and quadrature (Q) components, respectively:

where and denote the real and imaginary operators, respectively. The I component reflects the signal aligned with the reference carrier, while the Q component corresponds to the signal orthogonal to the carrier. Together, the IQ components form the complete complex baseband representation, which is fundamental in digital modulation and demodulation.

In automatic modulation classification (AMC), the IQ signals serve as input features to the model. For a sampled sequence, the input matrix can be expressed as

where and are composed of the I and Q components of all sampled points, respectively. The matrix X transforms the continuous-time wireless signal into a discrete representation suitable for deep learning models, providing the foundation for subsequent modulation recognition.

3.2. Proposed Model

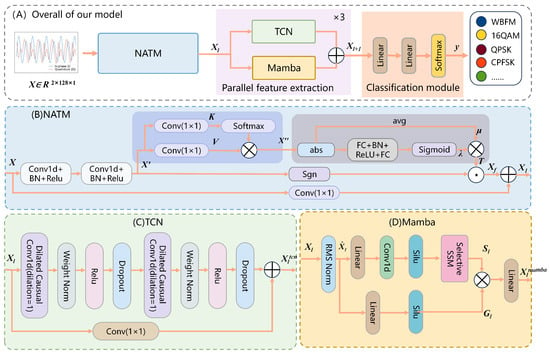

As shown in Figure 1, the proposed AMC model is designed to achieve robustness under low-SNR conditions while maintaining lightweight complexity. The model consists of three main components: (1) The NATM suppresses noise and generates symbol-dependent thresholds to enhance the effective SNR; (2) a dual-branch feature extraction module employing parallel TCN and Mamba networks to capture both local temporal patterns and long-range dependencies; (3) a classification module that outputs the predicted modulation type.

Figure 1.

Overview of the Proposed Model. (A) Overall architecture integrating NATM, a parallel TCN–Mamba feature extraction block, and the classification module. (B) NATM structure, which applies non-local thresholding to adaptively suppress noise. (C) TCN branch for extracting local temporal features using dilated causal convolutions. (D) Mamba branch for modeling long-range dependencies through a selective state-space mechanism.

3.2.1. Non-Local Adaptive Thresholding Module (NATM)

To address the challenge of heavily degraded IQ signals in low-SNR environments, we incorporate the NATM module, which enhances robustness by adaptively suppressing noise before feature extraction. Unlike conventional methods relying on global average estimates, NATM leverages a non-local attention mechanism to generate symbol-dependent thresholds, thereby preserving discriminative features while attenuating noise-dominated components.

As shown in Figure 1B, the input IQ signal is first processed through two 1D convolutional layers with ReLU activation and batch normalization (BN), yielding richer feature representations:

Here, is the output feature; Conv(.) denotes 1D convolution mapping the input from to , while ReLU(.) and BN(.) represent the activation and batch normalization, respectively.

To enhance cross-channel contextual modeling, NATM replaces traditional global average pooling with a non-local attention mechanism. Specifically, the feature is processed by two convolutions to obtain the key vector K and value vector V. The Softmax-normalized generates channel attention weights, which are used to aggregate the value features in V to obtain the enhanced representation :

The attention-enhanced feature is computed as

Next, the baseline amplitude is calculated by absolute mean per channel, followed by two fully connected layers with Sigmoid activation to produce the channel-wise scaling factor . The final threshold is obtained as

The gated feature is fused with NATM’s original 2-channel IQ feature via residual addition, with the 2-channel feature expanded to 16 channels via convolution. The fused feature is passed to the subsequent dual-branch feature extraction module.

3.2.2. Parallel Feature Extraction

To effectively classify modulation signals, an AMC model must capture both local symbol-level patterns and long-range temporal dependencies. Local characteristics such as pulse shapes and short-range correlations carry strong class-specific information, while global temporal dynamics across frames are crucial for identifying higher-order modulations and dealing with fading effects. This motivates a feature extraction design that incorporates both perspectives.

To address this, we design a parallel feature extraction module with two complementary branches. The TCN branch captures multi-scale local structures through dilated causal convolutions, preserving temporal causality while efficiently enlarging the receptive field. The dilation factors are chosen to balance receptive field growth with latency, ensuring symbol-level dependencies are covered within typical packet lengths. In contrast, the Mamba branch employs a state-space mechanism with linear recurrence and gating to model long-range dependencies at low complexity. The gating operation further suppresses irrelevant temporal variations, which is critical under low-SNR conditions. Their outputs are fused via additive integration after each layer, allowing the two branches to reinforce each other without the parameter inflation of concatenation. This dual-branch module is stacked three times in depth, providing progressive feature refinement while maintaining a lightweight architecture. Each layer computes as

Feature dimensions remain unchanged across layers. This preserves critical temporal patterns for modulation classification while avoiding complexity inflation to ensure real-time performance.

(1) TCN Branch

Temporal dependencies at the symbol level, such as pulse shapes, phase transitions, and short-range correlations, are critical cues for distinguishing modulation types in communication signals. Conventional CNNs are restricted by narrow receptive fields, while RNNs often suffer from vanishing gradients and high latency, limiting their suitability for real-time AMC tasks [25].

To address this, the TCN branch adopts a Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN) architecture with stacked residual blocks, see the TCN branch structure in Figure 1C. Each block consists of dilated causal convolutions, ReLU activation, dropout, and weight normalization. Optional convolutions are applied in residual connections to ensure dimensional consistency without breaking temporal order. This design allows the model to efficiently capture multi-scale local temporal patterns while maintaining causality, thereby enhancing classification robustness under practical channel conditions.

Given input , the output of the l-th TCN layer is

Here, denotes 1D causal convolution with dilation rate d. In our three-layer design, d is set to 1, 2, and 4 in the first, second, and third layers, respectively, enabling multi-scale temporal receptive fields.

(2) Mamba Branch

In practical wireless communications, many modulation schemes, particularly higher-order constellations under fading channels, exhibit dependencies that span long symbol sequences or even entire frames. Capturing these global temporal dynamics is essential for distinguishing between modulation formats that share similar short-term patterns [21]. Conventional CNNs and TCNs are restricted to short- and mid-range contexts, while Transformer-based self-attention can model long-range dependencies but incurs quadratic computational cost, making it unsuitable for real-time AMC on resource-constrained devices.

To address this, the Mamba branch employs a State Space Model (SSM) formulation that replaces explicit attention with learnable recurrence, enabling linear-time sequence processing. This design allows the network to capture long-range, continuous dependencies across symbols and frames while maintaining lightweight complexity suitable for deployment.

See Figure 1D. Given the input , the Mamba branch feature of the l-th layer is obtained through the following process: first undergoes a linear projection to produce , then splits into two parallel paths: one for generating gating signals , and the other for computing state updates via the State Space Model (SSM). Finally, and are element-wise multiplied and fed to a linear layer to yield . The process is defined as follows:

Here, denotes the SiLU activation function, and ⊙ is element-wise multiplication. The SSM module models implicit state transitions via learned convolutional dynamics, enabling efficient sequence updates.

Mamba captures long-range patterns better than TCN. Stacked in parallel, they preserve temporal resolution while enhancing channel depth, combining local and global features for robust sequence modeling.

3.2.3. Classification Module

To predict modulation types, we employ a two-layer linear classifier composed of ReLU activation and Softmax normalization. Formally, the prediction process is defined as

where denotes the predicted probability distribution over K modulation classes. During training, the cross-entropy loss is adopted to optimize the classifier’s parameters.

3.3. Datasets and Experimental Settings

3.3.1. Datasets

We evaluate our approach on three widely used benchmarks: RadioML 2016.10A, RadioML 2016.10B, and RadioML 2018.01A [2,26,27].

RadioML 2016.10A includes 11 modulation types (8 digital and 3 analog) with SNRs ranging from dB to dB in 2 dB steps, sampled at 1 Msps. This dataset contains only additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN) without multipath fading; therefore, 0% of samples include fading effects.

RadioML 2016.10B covers 10 modulation types, including higher-order QAM, and introduces realistic channel impairments such as Rayleigh multipath fading, timing offset, and frequency offset [4]. As a result, 100% of the samples in this dataset contain multipath fading.

RadioML 2018.01A contains 24 modulation types under more complex wireless channel conditions, including Rayleigh and Rician fading, Doppler spread, oscillator drift, and synchronization offsets [27,28]. Thus, 100% of its samples include multipath fading and other channel-induced distortions, making it a widely used over-the-air benchmark.

In addition, for all RadioML datasets used in this work, the SNR values provided with each sample follow the original dataset generation procedure. The SNR is defined at the complex baseband sample level after pulse shaping and before channel noise injection, and is computed uniformly across all modulation types. It therefore corresponds to the per-sample signal-to-noise ratio rather than an or definition that depends on modulation order. All signals are sampled at 1 Msps without additional oversampling, and the same SNR definition applies consistently to both training and test samples.

3.3.2. Leakage-Controlled Partitioning

Prior studies have shown that RadioML datasets may suffer from sample leakagedue to overlapping IQ windows being split between train and test sets [9,10,29]. To address this, we adopt two leakage-controlled protocols:

- GroupKFold: Partitioned by capture ID to ensure that no contiguous IQ segments are shared between splits [18].

- Leave-One-SNR-Out (LOSO): Each SNR is left out once as a held-out test set [27,28,30].

This prevents inflated accuracy caused by near-duplicate samples and ensures more realistic evaluation.

3.3.3. Training Setup

All models are implemented in PyTorch (version 2.0, Meta, Menlo Park, CA, USA) [31] and trained with the Adam optimizer (learning rate 0.005, batch size 256) for 150 epochs.

For the 2016.10A dataset, each 80:20 split yields approximately 132K training and 44K test samples per fold, while for 2016.10B the corresponding numbers are 720K and 240K. All experiments are conducted on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU.

3.3.4. Reproducibility and Confidence Intervals

To ensure statistical validity, all experiments are repeated with five random seeds: 42, 8, 17, 23, 61.We report all results (OA, Kappa, F1) in the format mean ± 95% CI, computed across these runs [9,12,18].

4. Results

4.1. Performance Evaluation on Different Datasets

To provide a comprehensive and representative evaluation, we compare the proposed model against six widely adopted baseline methods on the three RadioML benchmark datasets (2016.10A, 2016.10B, and 2018.01A). The selected baselines cover the main deep-learning paradigms used in AMC research, including convolution-based models, recurrent sequence models, hybrid architectures, lightweight CNN variants, and a recent state-of-the-art self-supervised approach. This selection ensures that different modeling strategies and feature-extraction mechanisms are fairly represented, enabling a reliable assessment of the proposed method relative to established AMC methodologies.

CNN2 [26]: a classical shallow CNN applied to raw IQ sequences, representing early convolution-based feature extraction.

LSTM2 [3]: a recurrent network designed to capture temporal dependencies in IQ samples, representing sequential modeling approaches.

CTDNN [4,5]: a deeper time-domain CNN with large receptive fields, offering stronger local feature extraction at higher computational cost.

CDSCNN [32]: a lightweight CNN utilizing depthwise separable convolutions, representing efficient convolutional architectures.

HCGDNN [33]: a hybrid CNN–GRU architecture that combines convolutional feature extraction with recurrent temporal modeling.

MCLHN [15]: a recent state-of-the-art model employing masked contrastive learning and TCN blocks, serving as a strong modern baseline for comparison.

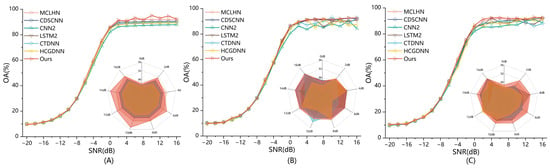

Here we mainly report overall accuracy (OA) and Kappa, as they are the most commonly used indicators in modulation recognition and can sufficiently reflect overall performance. As shown in Figure 2, our model achieves consistently competitive accuracy under moderate to high SNR conditions (above dB) across all three datasets. In particular, it performs comparably or better than MCLHN in most SNR intervals. Across the three datasets, the proposed model attains overall accuracies of 62.78%, 64.44%, and 69.91%, respectively, which are close to or slightly below those of MCLHN (60.76%, 63.72%, 70.77%). Compared with mid-sized models such as CTDNN, our method improves accuracy by 5.3%, 3.4%, and 2.8% on the three datasets. These results clearly demonstrate the advantage of our lightweight multi-scale architecture in extracting discriminative features from IQ sequences. Table 1 further illustrates the balance between performance and efficiency: our model consistently ranks among the top-2 in both OA and Kappa, while being the most parameter-efficient among all high-performing baselines.

Figure 2.

Performance comparison of different models on the RadioML 2016.10A/B and 2018.01A datasets under varying SNR conditions. (A) OA(%) versus SNR(dB) results under Dataset 1. (B) OA(%) versus SNR(dB) results under Dataset 2. (C) OA(%) versus SNR(dB) results under Dataset 3.

Table 1.

Comparison of performance (Kappa, %) of different models on RadioML datasets. All baseline results reported in this paper are cited from the original publications and were obtained under the same datasets and evaluation protocols. We follow the standard RadioML settings (same dataset versions and SNR configurations) to ensure a fair comparison. The best results are highlighted in bold, and the second-best results are underlined for clear comparison.

Finally, the inclusion of RadioML 2018.01A offers a more rigorous validation of generalization [27,28]. As shown in Table 1, our model consistently outperforms the baselines across all three datasets, including RadioML 2018.01A, where it achieves a Kappa score of 55.37, maintaining its advantage despite the more challenging conditions. This demonstrates the robustness and overall performance of our approach, validating its effectiveness for real-world applications.

To acknowledge recent progress in the field, we note that several newer AMC models have been proposed after 2024, and incorporating these methods into a more comprehensive comparison will be explored in future work.

4.2. Efficiency Analysis

To comprehensively evaluate computational efficiency, we compared the proposed model with representative baselines in terms of parameter count, FLOPs, and inference latency under samples with a length of 4096, as summarized in Table 2. Our method achieves the lowest parameter count () and FLOPs ( G), which represent reductions of 65.7% and 77.6% compared with MCLHN ( M, G), respectively.

Table 2.

Efficiency comparison of models under batch size = 1. The best results are highlighted in bold, and the second-best results are underlined for clear comparison.

Regarding inference latency, the proposed model requires only 4.75 ms per sample on an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU, which is faster than CTDNN (5.63 ms), HCGDNN (8.21 ms), and MCLHN (11.40 ms). These results highlight not only the architectural compactness of our design but also its practical advantage in runtime performance [34].

Taken together, the proposed framework achieves a favorable balance between accuracy and efficiency, making it a strong candidate for real-time or resource-constrained AMC applications.

Since the proposed model is primarily designed for deployment on GPU-accelerated platforms such as embedded AI modules and edge computing devices, we focus on GPU latency with batch size = 1. CPU latency is not reported because the framework is not optimized for CPU inference.

4.3. Ablation Study

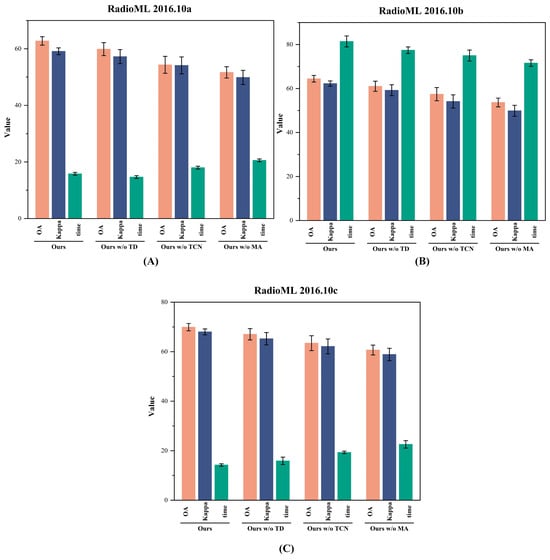

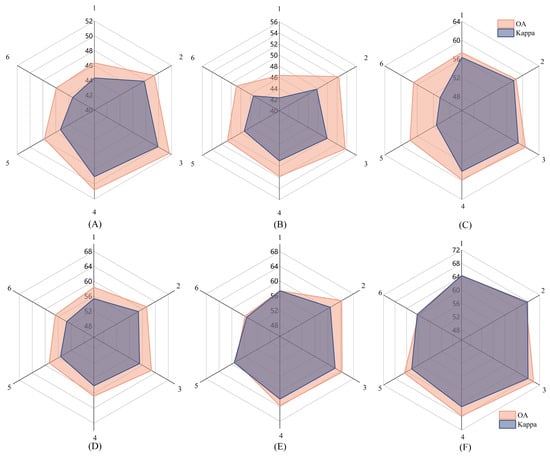

To verify the individual contributions of each module, we conducted ablation experiments by selectively removing or combining components from our framework, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Ablation study results on RadioML 2016.10A, 2016.10B, and 2018.01A datasets. (A) Results on the RadioML 2016.10A dataset. (B) Results on the RadioML 2016.10B dataset. (C) Results on the RadioML 2018.01A dataset.

- Ours w/o MA: NATM + TCN.

- Ours w/o TCN: NATM + Mamba.

- Ours w/o NATM: Dual branches without NATM.

- Ours: Complete architecture.

We also evaluate the performance of each component individually to further examine their standalone contributions. The results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Performance of individual modules on different datasets. Latency is measured as the average forward-pass time of the module alone (batch size = 1, RTX 4090 GPU). Note that these numbers are not directly comparable to the end-to-end inference latency reported in Table 2 and Table 4, which include the complete network pipeline.

The results in both Figure 3 and Table 3 indicate that each module contributes independently and significantly to overall performance. Specifically, the threshold-based denoising module enhances robustness in low-SNR regimes by suppressing noise-dominated components, which is especially valuable for short input segments. The TCN branch captures local temporal dependencies, such as pulse shapes and short-range correlations, which are critical for distinguishing similar digital modulations. Meanwhile, the Mamba branch excels in modeling long-range dependencies across symbol sequences, benefiting high-order modulation formats and fading-prone channels.

Among the single-module variants, the Mamba-only configuration achieves the highest OA and Kappa, underscoring the importance of global temporal modeling in AMC. However, it still falls short of the full model, which integrates all three components. The complete framework consistently outperforms all partial variants across datasets, confirming that the three modules are not only individually beneficial but also complementary when combined.

It is important to note that the latency reported in Table 3 reflects the per-module forward-pass time, which is naturally shorter than the full end-to-end inference latency (Table 2 and Table 4). This separation allows us to analyze the computational footprint of each component in isolation while still providing a realistic assessment of the complete model in subsequent efficiency experiments.

Table 4.

Comparison of fusion strategies across three datasets. Sum fusion achieves the best accuracy–efficiency trade-off. The best results are highlighted in bold, and the second-best results are underlined for clear comparison.

4.4. Fusion Method Comparison

We further compare three fusion strategies between the TCN and Mamba branches to verify that our choice of additive fusion is well-founded rather than arbitrary. The evaluated methods include

- Sum (ours): Element-wise addition of branch outputs after each layer.

- Concat: Concatenation followed by a linear projection to match dimensionality.

- Gated: A learnable weight-based gating mechanism for adaptive fusion.

As shown in Table 4, the Sum fusion consistently achieves the highest overall accuracy on 2018.01A, while maintaining the lowest parameter count () and fastest inference speed (13.12 ms per batch). In contrast, the Concat strategy introduces more parameters and latency due to dimensional expansion, and the Gated method, while moderately effective, still lags behind Sum fusion in both accuracy and efficiency. These results confirm that simple additive fusion offers the best trade-off between performance and complexity in our architecture.

4.5. Performance Evaluation at Different SNRs

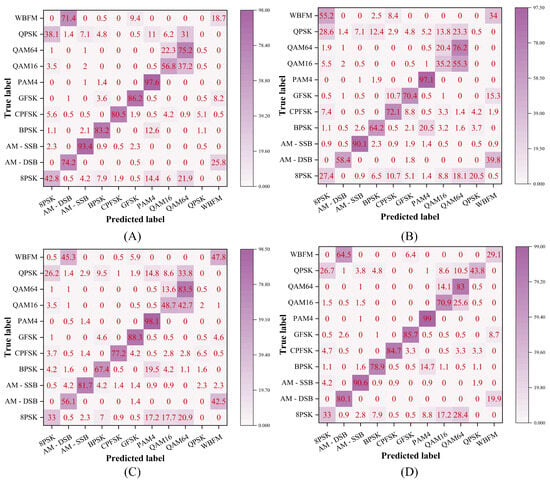

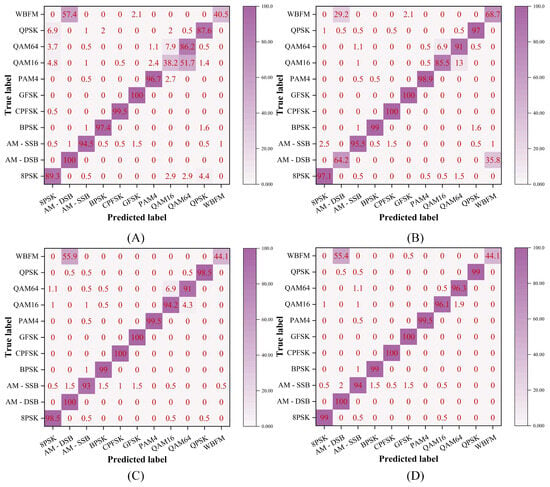

We evaluate model performance under both low ( dB) and high (16 dB) SNR conditions. As shown in Figure 4, at dB all models suffered from heavy noise, but the proposed method exhibited the least confusion, particularly for high-order modulations such as 16QAM, 64QAM, PAM4, and CPFSK. At 16 dB, while classification accuracy improved across all methods (Figure 5), certain analog modulations such as AM-DSB and WBFM remained challenging due to silent segments present in the RadioML 2016.10A dataset.

Figure 4.

Confusion matrix at SNR = −4 dB. (A) CNN2; (B) HCGDNN; (C) MCLHN; (D) Ours.

Figure 5.

Confusion matrix at SNR = 16 dB. (A) CNN2; (B) HCGDNN; (C) MCLHN; (D) Ours.

Our approach consistently achieved superior discrimination of 16QAM and 64QAM, which many baselines misclassified because of their similar constellation patterns. It also obtained near-perfect accuracy on 8PSK, CPFSK, and BPSK, demonstrating robustness across both digital and analog schemes.

To provide a clearer evaluation, we further report Macro-F1 scores in Table 5. The results demonstrate that the proposed method not only improves overall accuracy and Kappa but also maintains comparable class-wise performance even under low SNR conditions. Specifically, at SNR = −4 dB, the model achieves an OA of 58.0%, Kappa of 56.0%, and Macro-F1 of 57.0%, which are on par with the performance at SNR = 0 dB (OA: 58.6%, Kappa: 56.2%, Macro-F1: 57.0%). This indicates that our method is effective in handling low SNR situations, achieving results comparable to those in higher SNR conditions.

Table 5.

Performance under different SNR levels on RadioML 2016.10A (mean ± 95% CI over 5 seeds). The best results are highlighted in bold, and the second-best results are underlined for clear comparison.

4.6. Impacts of Model Structure Design on Model Performance

As illustrated in Figure 6A–C compare the performance of TCN modules with different depths (1–6 layers) on the RadioML 2016.10A, 2016.10B, and 2018.01A datasets without Mamba. Across all three datasets, the accuracy and Kappa values steadily increase as the TCN becomes deeper, with the 3-layer TCN achieving the best trade-off between accuracy and stability. Figure 6D–F then fix the TCN at three layers and progressively increase the number of Mamba layers (1–3) across the three datasets. The results consistently indicate that adding Mamba improves performance, with the 3-layer Mamba configuration achieving the highest scores.

Figure 6.

Performance comparison of TCN–Mamba under different configurations. Subfigures (A–C) show the impact of varying TCN depths (1–6 layers) without Mamba on the RadioML 2016.10A, 2016.10B, and 2018.01A datasets. Subfigures (D–F) fix the TCN depth at three layers and report the results of adding 1–3 Mamba layers across the three datasets.

In summary, combining a 3-layer TCN with a 3-layer Mamba yields the best performance in terms of accuracy, consistency, and robustness. These findings highlight the complementary strengths of local and global modeling and demonstrate that our dual-branch architecture is well-suited for complex signal classification scenarios.

5. Discussion

The experimental results across different datasets (RadioML 2016.10A, 2016.10B, and 2018.01A) demonstrate that our lightweight AMC framework effectively balances classification accuracy, parameter efficiency, and inference speed. Compared with mid-sized models, our method achieves accuracy improvements of over 5% while using only a fraction of the parameters, highlighting its computational advantages. Relative to MCLHN, the performance remains comparable while requiring substantially fewer resources. Furthermore, the NATM provides clear benefits under low-SNR conditions by alleviating noise-induced degradation in IQ samples, contributing to the overall robustness of the framework. These observations collectively confirm the effectiveness of the proposed design and provide a solid foundation for further analysis in the subsequent discussion. The collective findings imply that the proposed design provides an effective balance between accuracy, robustness, and efficiency, underscoring its suitability for practical AMC applications where computational resources and channel conditions may be highly constrained.

Moreover, although the denoising module has achieved significant results under low SNR conditions, it may need further optimization when dealing with non-Gaussian noise. Future research could focus on further improving the model’s performance under high SNR conditions, exploring other denoising methods, and meeting real-time requirements for practical applications [24].

6. Conclusions

In this work, we presented a lightweight AMC framework integrating a non-local adaptive thresholding denoising module, a dual-branch TCN–Mamba feature extractor, and a compact classifier. The proposed design explicitly enhances robustness under low SNR conditions, balances local and global feature modeling, and remains highly parameter-efficient. Experimental results on RadioML 2016.10A/B and 2018.01A confirm the effectiveness of our approach across different datasets and SNR ranges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization Conceptualization, Y.K.; Methodology, Y.K.; Software, Y.K.; Validation, Y.K.; Formal analysis, Y.K.; Investigation, Y.K.; Resources, Y.G. and Z.G.; Data curation, Y.K.; Writing—original draft preparation, Y.K.; Writing—review and editing, Y.G. and Z.G.; Visualization, Y.K.; Supervision, Y.G. and Z.G.; Project administration, Y.G.; Funding acquisition, Y.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the RadioML dataset at https://www.deepsig.io/datasets (accessed on 10 March 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the open-source community for providing the RadioML datasets used in this study. No additional support beyond the reported funding was received.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Dobre, O.A.; Abdi, A.; Bar-Ness, Y.; Su, W. Survey of Automatic Modulation Classification Techniques: Classical Approaches and New Trends. IET Commun. 2007, 1, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, T.J.; Roy, T.; Clancy, T.C. Over-the-Air Deep Learning Based Radio Signal Classification. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2018, 12, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, S.; Meert, W.; Giustiniano, D.; Lenders, V.; Pollin, S. Deep Learning Models for Wireless Signal Classification with Distributed Low-Cost Spectrum Sensors. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Commun. Netw. 2018, 4, 433–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, N.; O’Shea, T.J. Deep Architectures for Modulation Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Dynamic Spectrum Access Networks (DySPAN), Baltimore, MD, USA, 6–9 March 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Lu, C.; Sun, Y.; Yang, M.; Liu, C.; Ou, C. Automatic ECG Classification Using Continuous Wavelet Transform and Convolutional Neural Network. Entropy 2021, 23, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, F.; Yue, C.; Han, C. A lightweight and efficient neural network for modulation recognition. Digit. Signal Process. 2022, 123, 103444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Jiang, J.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, H.; Huang, D.; Lu, Y. Improving Computation and Memory Efficiency for Real-world Transformer Inference on GPUs. Acm Trans. Archit. Code Optim. 2023, 20, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanghieri, M.; Benatti, S.; Burrello, A.; Kartsch, V.; Conti, F.; Benini, L. Robust Real-Time Embedded EMG Recognition Framework Using Temporal Convolutional Networks on a Multicore IoT Processor. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2020, 14, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Ma, Q.; Ding, W. Multiscale Correlation Networks Based on Deep Learning for Automatic Modulation Classification. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2023, 30, 633–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Zhao, P.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y. Spectrum interference-based two-level data augmentation method in deep learning for automatic modulation classification. Neural Comput. Appl. 2021, 33, 7723–7745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Gan, F.; Cao, X.; Liu, W. Signal Modulation Classification Based on the Transformer Network. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Commun. Netw. 2022, 8, 1348–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.C.; Han, D.S. Deep Learning-Based Automatic Modulation Classification With Blind OFDM Parameter Estimation. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 108305–108317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Shi, J.; Li, Z.; Du, M.; Liu, F.; Zeng, F. Contrastive Semi-Supervised Learning With Pseudo-Label for Radar Signal Automatic Modulation Recognition. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 30399–30411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Cao, Y.; Li, G.; Li, X. MAMC—Optimal on Accuracy and Efficiency for Automatic Modulation Classification with Extended Signal Length. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2024, 28, 2864–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Yang, S.; Feng, Z.; Jiao, L. MCLHN: Toward Automatic Modulation Classification via Masked Contrastive Learning with Hard Negatives. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2024, 23, 14304–14319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Deng, T.; Gavin, B.; Ball, E.A.; Seed, L. A Ultra-Low Cost and Accurate AMC Algorithm and Its Hardware Implementation. IEEE Open J. Comput. Soc. 2024, 6, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Chen, S.; Ma, Y.; Gao, Y.; Yang, S. Learning Temporal–Spectral Feature Fusion Representation for Radio Signal Classification. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2025, 21, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Jin, Z. Latent Modulated Function for Computational Optimal Continuous Image Representation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 26026–26035. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, A.; Dao, T. Mamba: Linear-Time Sequence Modeling with Selective State Spaces. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2312.00752. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, S.; Kolter, J.Z.; Koltun, V. An Empirical Evaluation of Generic Convolutional and Recurrent Networks for Sequence Modeling. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.01271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Fei, Z. GIGNet: A Graph-in-Graph Neural Network for Automatic Modulation Recognition. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 10058–10062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, T.T.; Argyriou, A.; Puspitasari, A.A.; Cotton, S.L.; Lee, B.M. Efficient Automatic Modulation Classification for Next-Generation Wireless Networks. IEEE Trans. Green Commun. Netw. 2025, 10, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Tian, X.; Yu, Z.; Yang, M.; Elhanshi, A.; Saponara, S. Robust automatic modulation classification using asymmetric trilinear attention net with noisy activation function. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 141, 109861. [Google Scholar]

- An, T.; Lee, B.M. Robust Automatic Modulation Classification in Low Signal to Noise Ratio. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 7860–7872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, T. Ghost Convolutional Neural Network-Based Lightweight Semantic Communications for Wireless Image Classification. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2025, 14, 886–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, T.; West, N. Radio Machine Learning Dataset Generation with GNU Radio. In Proceedings of the GNU Radio Conference, Boulder, CO, USA, 12–16 September 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, J.; Xu, Y. Large-Scale Real-World Radio Signal Recognition with Deep Learning. J. Electron. Inf. Technol. 2022, 35, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekbiyik, K.; Ekti, A.; Görçin, A.; Kurt, G.; Keçeci, C. Robust and Fast Automatic Modulation Classification with Convolutional Neural Networks under Multipath Fading Channels. In Proceedings of the IEEE Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC-Spring), Antwerp, Belgium, 25–28 May 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, H.S.; Ali, M.H.E.; Ismail, M.; Shaaban, M.N.; Mohamed, M.L.; Atallah, H.A. Automatic Modulation Classification: Convolutional Deep Learning Neural Networks Approaches. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 98695–98705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, J.K.; Darr, M.J. Interpretable AI for Time-Series: Multi-Model Heatmap Fusion with Global Attention and NLP-Generated Explanations. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.00234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; pp. 8024–8035. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, C.; Yang, S.; Feng, Z. Complex-Valued Depthwise Separable Convolutional Neural Network for Automatic Modulation Classification. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 2522310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, B. CA-CNN-GRU Communication Modulation Signal Classification Method Based on Multi-Scale Feature. IET Trans. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2025. Early View. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveen, S.; Kounte, M.R.; Ahmed, M.R. Low Latency Deep Learning Inference Model for Distributed Intelligent IoT Edge Clusters. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 160607–160621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.