SpikingDynamicMaskFormer: Enhancing Efficiency in Spiking Neural Networks with Dynamic Masking

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- We introduce SDMFormer, an improvement of Spikformer, aimed at significantly reducing the network’s parameters and energy consumption.

- (2)

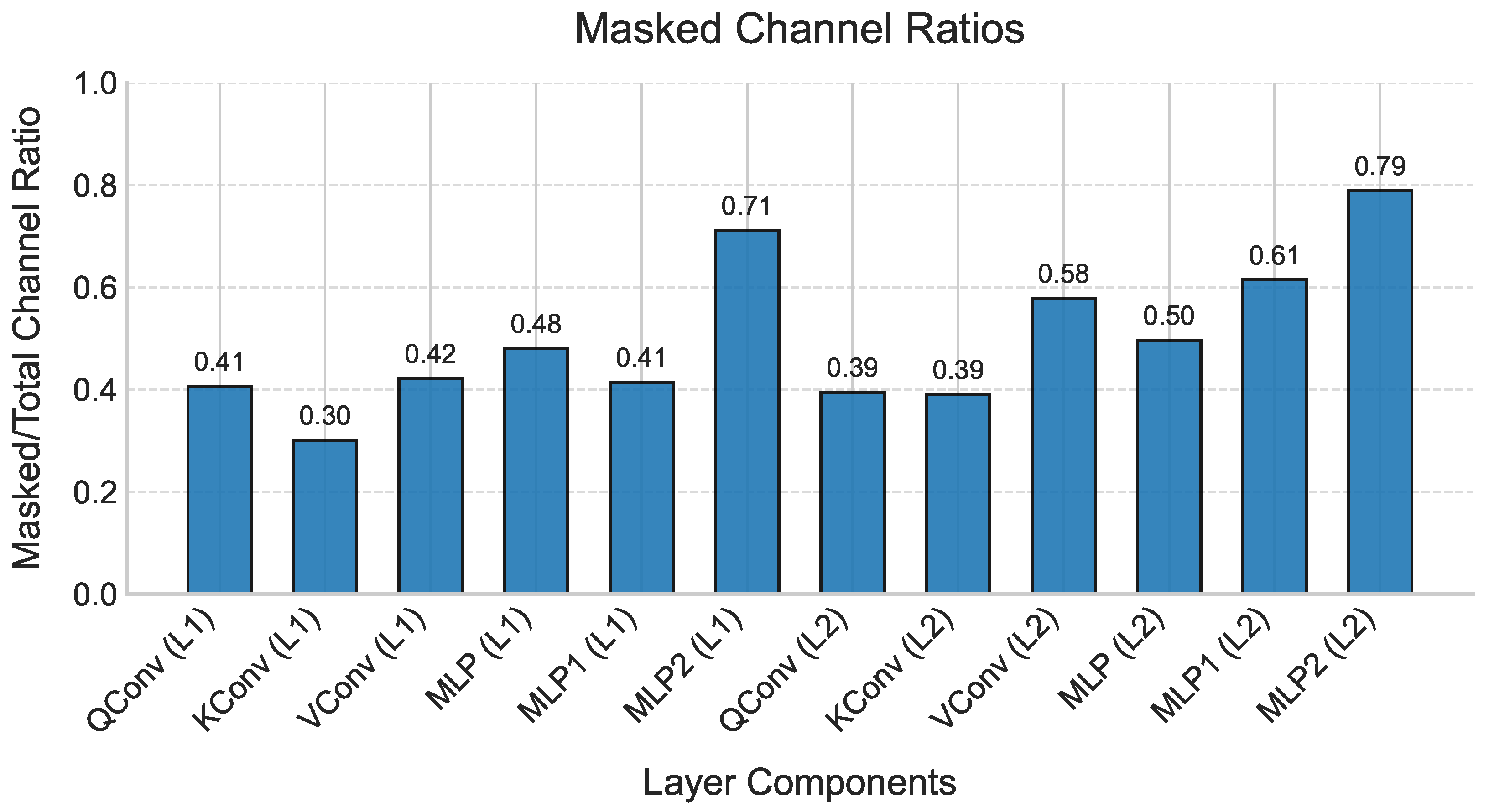

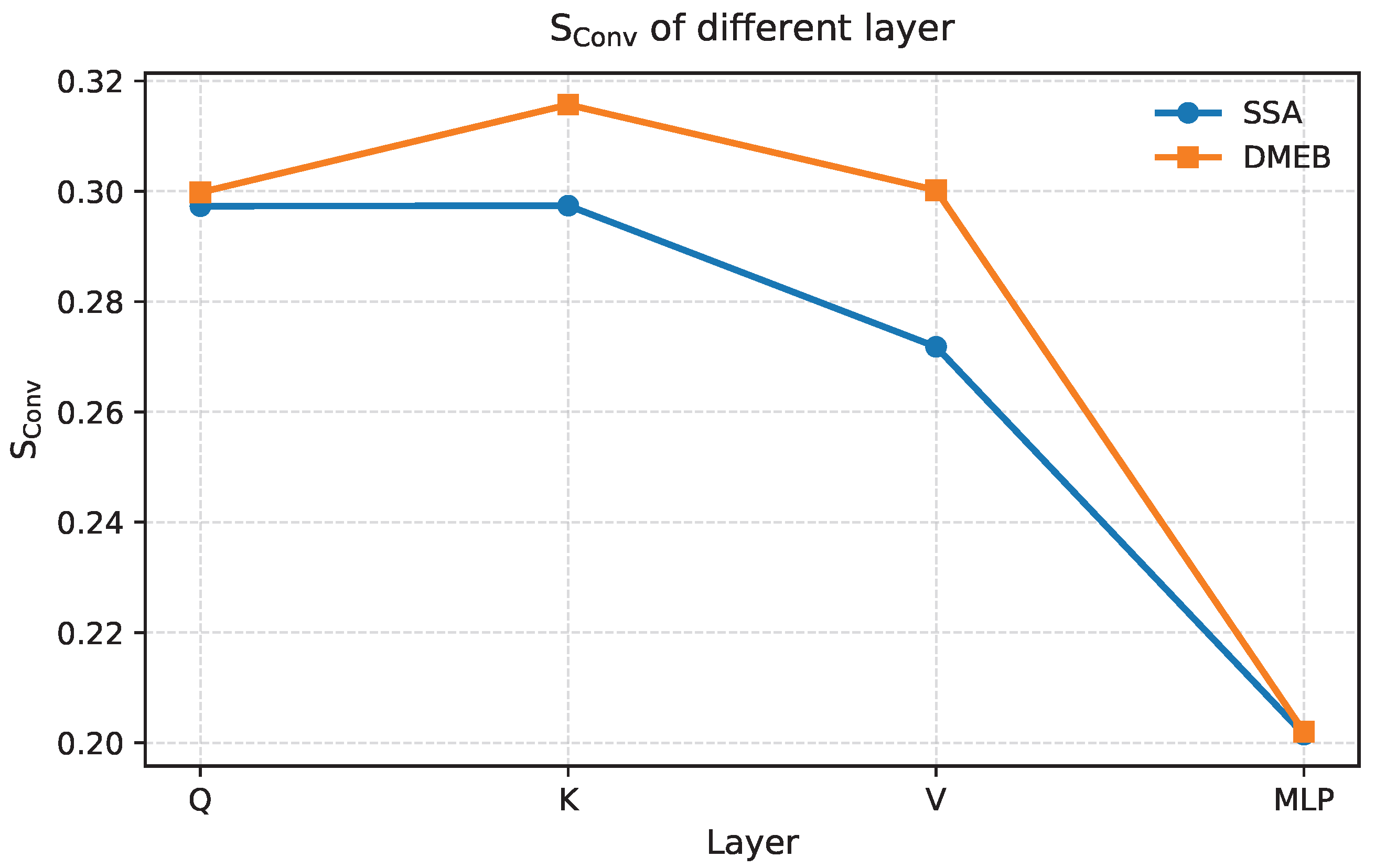

- To address channel redundancy in Spikformer networks, we propose DMEB that dynamically learns and adjusts mask values during training to suppress spike emissions in ineffective channels. Pruning these redundant channels not only preserves model performance but also significantly reduces model parameters and inference energy consumption.

- (3)

- We redesign the original relative position encoding into a streamlined module through structural optimization and feature fusion enhancement. Integrated with SPS, LPE focuses computation on information-rich regions while maintaining parameter efficiency (20.3% reduction vs. conventional RPE modules).

2. Related Work

2.1. Spiking Convolutional Neural Networks

2.2. Spiking Transformer Architecture

2.3. Model Pruning Techniques

3. Methods

3.1. LIF Neuron

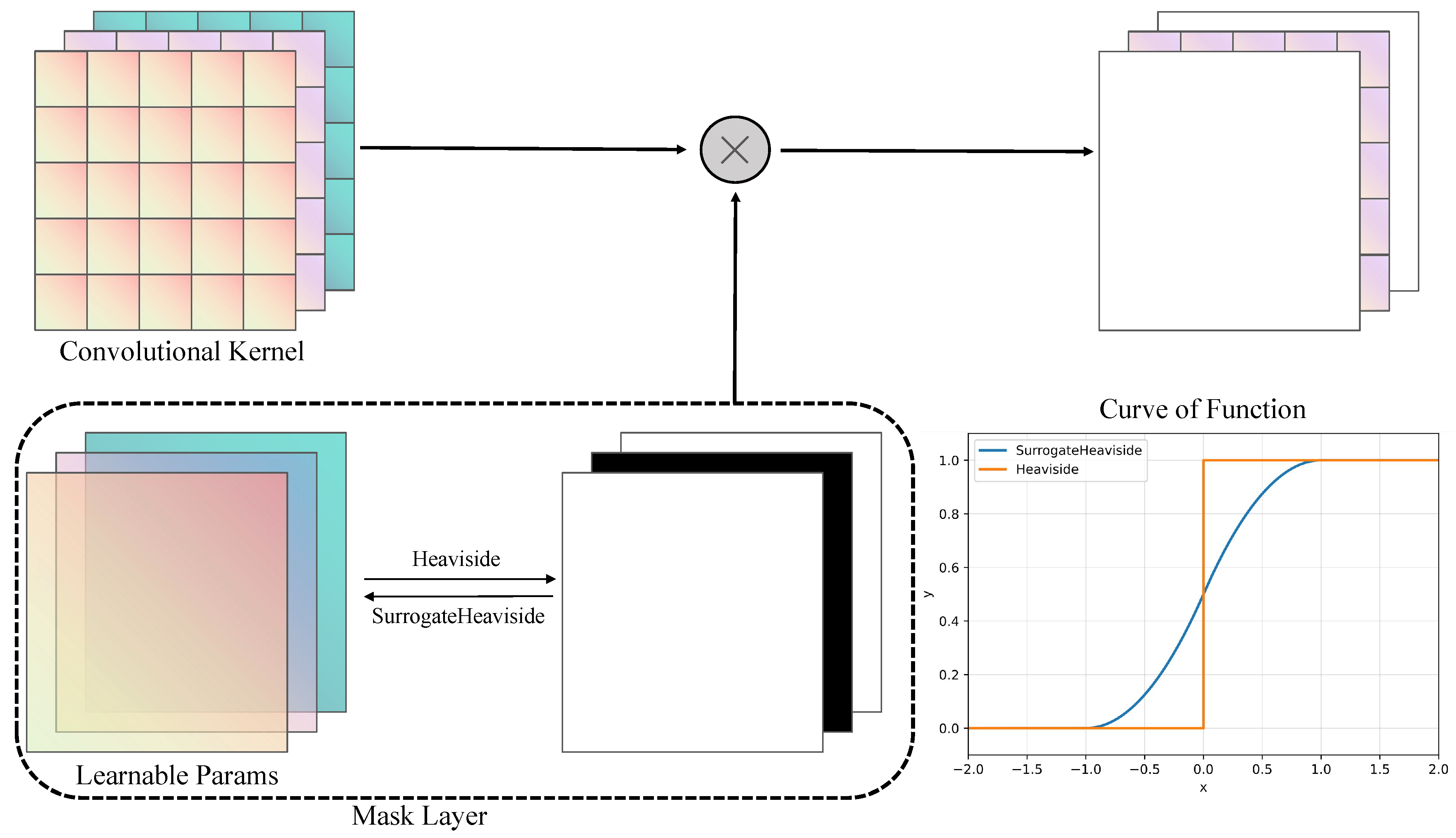

3.2. Mask Layer

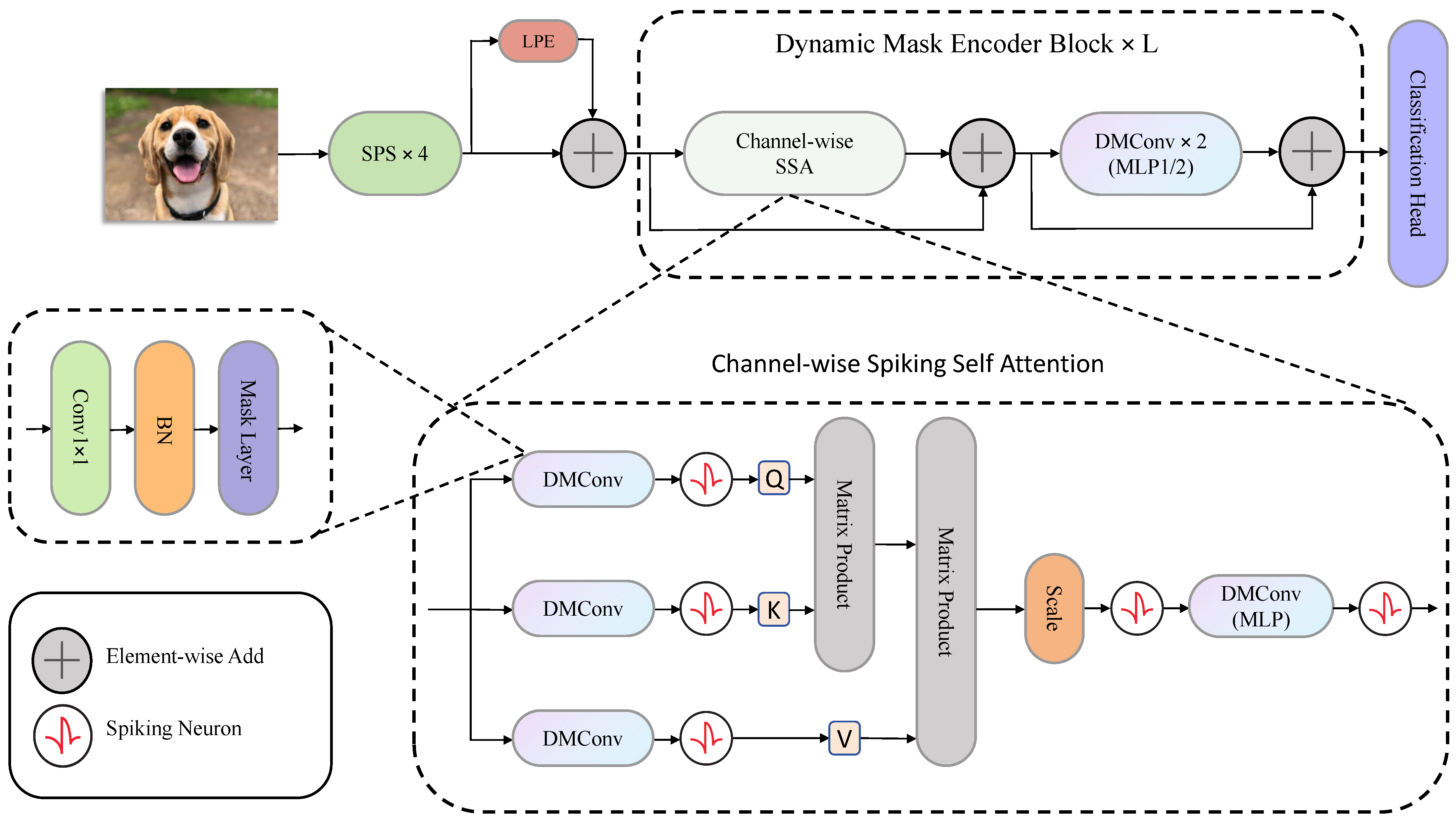

3.3. Dynamic Mask Encoder Block

3.4. Lightweight Position Embedding

4. Experiments

- DVS128 Gesture [51]: Captured using Dynamic Vision Sensors (DVS), this dataset records pixel-change events rather than conventional image frames. It contains 11 hand gestures performed by 29 subjects under three illumination conditions, comprising 1342 event streams.

- CIFAR10-DVS [52]: As a neuromorphic adaptation of CIFAR-10, this dataset features 10 classes with 10,000 samples per class. Following Spikformer’s protocol, we use the first 9000 samples per class for training and the remaining 1000 for testing, ensuring fair comparison.

- N-Caltech101 [53]: This neuromorphic conversion of Caltech101 excludes duplicate “Faces” categories, resulting in 100 object classes plus background. Captured via ATIS sensor mounted on a pan-tilt unit observing LCD-displayed images, it preserves biological vision characteristics through active camera movements.

4.1. Implementation Details

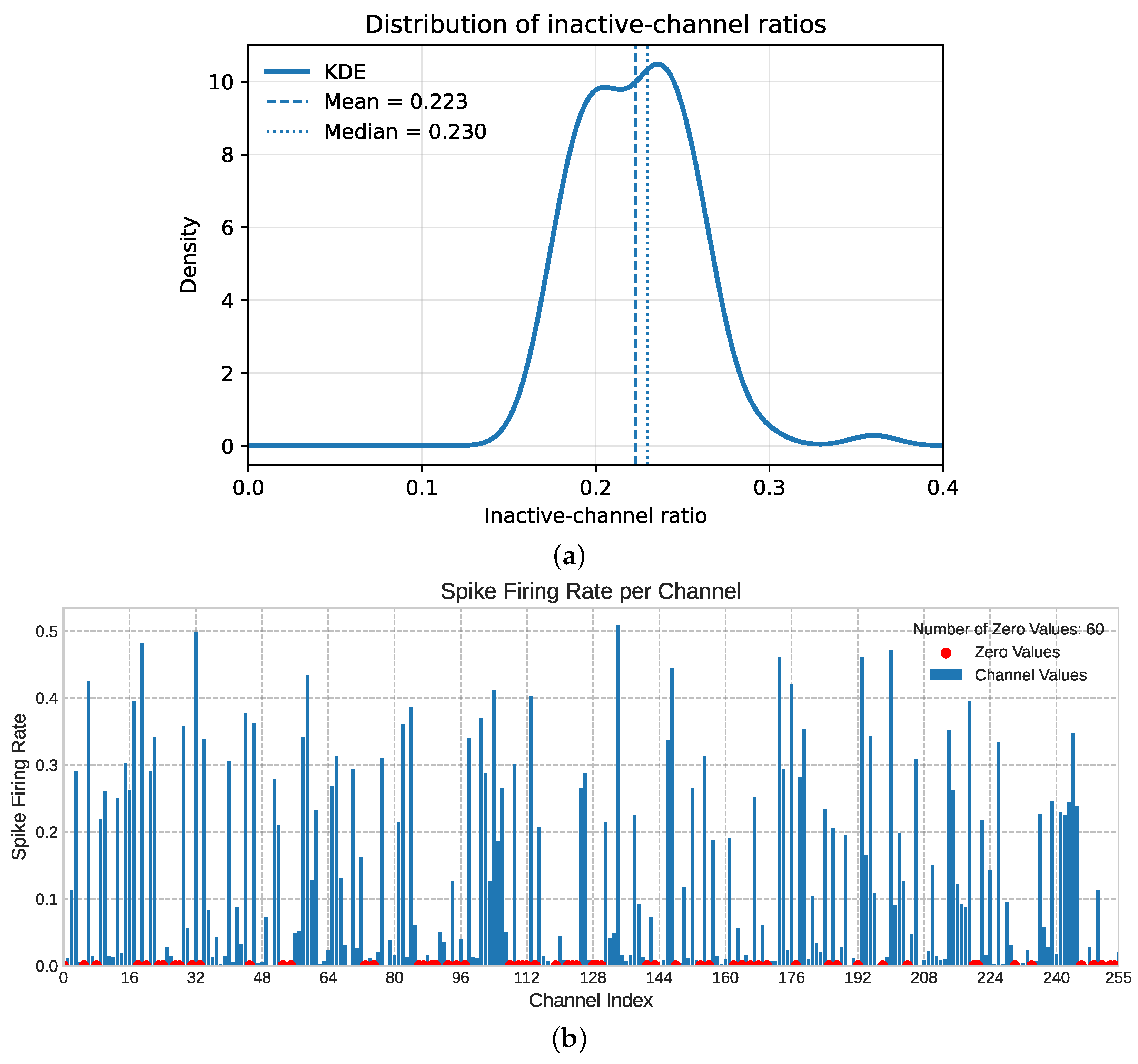

4.2. Mask Rate

4.3. Comparison with Baseline

4.3.1. Number of Parameters

4.3.2. Energy Consumption

4.4. Comparison with Related Work

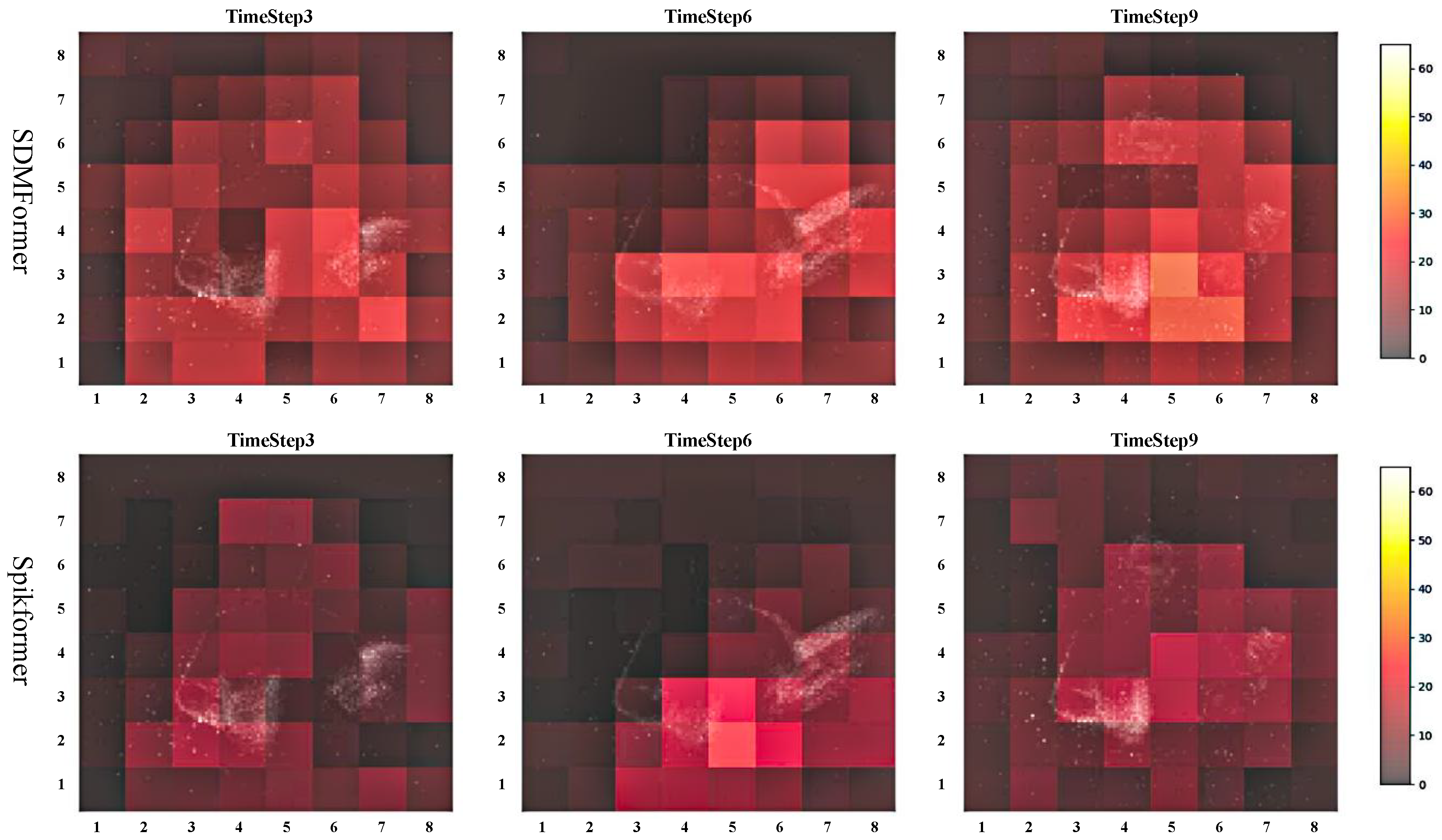

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maass, W. Networks of Spiking Neurons: The Third Generation of Neural Network Models. Neural Netw. 1997, 10, 1659–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, K.; Jaiswal, A.; Panda, P. Towards Spike-Based Machine Intelligence with Neuromorphic Computing. Nature 2019, 575, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, K.; Vo-Ho, V.K.; Bulsara, D.; Le, N. Spiking Neural Networks and Their Applications: A Review. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Wu, Y.; Hu, X.; Liang, L.; Ding, Y.; Li, G.; Zhao, G.; Li, P.; Xie, Y. Rethinking the Performance Comparison between SNNs and ANNs. Neural Netw. 2020, 121, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Tang, H.; Pan, G. Spiking Deep Residual Networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 34, 5200–5205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30, pp. 6000–6010. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image Is Worth 16 × 16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) 2021, Virtual Event, 3–7 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhu, Y.; He, C.; Wang, Y.; Yan, S.; Tian, Y.; Yuan, L. Spikformer: When Spiking Neural Network Meets Transformer. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) 2023, Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, H.; Wu, Y.; Deng, L.; Hu, Y.; Li, G. Going Deeper With Directly-Trained Larger Spiking Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Fifth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI) 2021, Virtually, 2–9 February 2021; pp. 11062–11070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voudaskas, M.; MacLean, J.I.; Dutton, N.A.W.; Stewart, B.D.; Gyongy, I. Spiking Neural Networks in Imaging: A Review and Case Study. Sensors 2025, 25, 6747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Li, X.; Gao, Y.; Niu, Y. Event-Driven Intrinsic Plasticity for Spiking Convolutional Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 33, 1986–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, P.U.; Neil, D.; Binas, J.; Cook, M.; Liu, S.C.; Pfeiffer, M. Fast-Classifying, High-Accuracy Spiking Deep Networks through Weight and Threshold Balancing. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Killarney, Ireland, 12–17 July 2015; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Li, Y.; Shen, J.; Zhang, P.; Liu, J.K.; Tang, H.; Pan, G. Hierarchical Spiking-Based Model for Efficient Image Classification With Enhanced Feature Extraction and Encoding. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 35, 9277–9285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Qiao, G.; Liu, X.K.; Liu, Y.H.; Zhang, C.M.; Zuo, Y.; Zhou, P.; Liu, Y.; Ning, N.; Yu, Q.; et al. A Co-Designed Neuromorphic Chip With Compact (17.9K F2) and Weak Neuron Number-Dependent Neuron/Synapse Modules. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2022, 16, 1250–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Kelber, F.; Vogginger, B.; Liu, C.; Kreutz, F.; Gerhards, P.; Scholz, D.; Knobloch, K.; Mayr, C.G. Efficient SNN Multi-Cores MAC Array Acceleration on SpiNNaker 2. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1223262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Shen, G.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, Q.; Zeng, Y. FireFly v2: Advancing Hardware Support for High-Performance Spiking Neural Network With a Spatiotemporal FPGA Accelerator. IEEE Trans. Comput. Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2024, 43, 2647–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Deng, S.; Dong, X.; Gong, R.; Gu, S. A Free Lunch From ANN: Towards Efficient, Accurate Spiking Neural Networks Calibration. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML) 2021, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; Proceedings of Machine Learning Research. Volume 139, pp. 6316–6325. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, S.; Gu, S. Optimal Conversion of Conventional Artificial Neural Networks to Spiking Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) 2021, Virtual Event, 3–7 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; Xiang, S.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, X.; Shi, Y. Conversion of a Single-Layer ANN to Photonic SNN for Pattern Recognition. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2024, 67, 112403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Deng, S.; Dong, X.; Gu, S. Error-Aware Conversion from ANN to SNN via Post-Training Parameter Calibration. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2024, 132, 3586–3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Chen, Y.; Qu, H. Signed Neuron with Memory: Towards Simple, Accurate and High-Efficient ANN-SNN Conversion. In Proceedings of the Thirty-First International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI) 2022, Vienna, Austria, 23–29 July 2022; pp. 2501–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, T.; Fang, W.; Ding, J.; Dai, P.; Yu, Z.; Huang, T. Optimal ANN-SNN Conversion for High-Accuracy and Ultra-Low-Latency Spiking Neural Networks. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.04347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, F.J.; Rostami, V.; Nawrot, M.P. Efficient Parameter Calibration and Real-Time Simulation of Large-Scale Spiking Neural Networks with GeNN and NEST. Front. Neuroinform. 2023, 17, 941696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, H.; He, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, T.; Zhong, Z.; Yu, J.; Wang, Y.; Tian, M.; Shi, C. High-Accuracy Deep ANN-to-SNN Conversion Using Quantization-Aware Training Framework and Calcium-Gated Bipolar Leaky Integrate and Fire Neuron. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1141701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyasothy, A.; Ramasamy, S.; Sundaram, S. A Gradient Descent Algorithm for SNN with Time-Varying Weights for Reliable Multiclass Interpretation. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 161, 111747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiple, B.; Patwardhan, M. Multi-Label Emotion Recognition from Indian Classical Music Using Gradient Descent SNN Model. Multim. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 8853–8870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Hu, X.; Deng, L.; Wu, Y.; Li, G.; Ding, Y.; Li, P.; Xie, Y. Exploring Adversarial Attack in Spiking Neural Networks With Spike-Compatible Gradient. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 34, 2569–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, F.; Zhao, D.; Zeng, Y. Directly Training Temporal Spiking Neural Network with Sparse Surrogate Gradient. Neural Netw. 2024, 179, 106499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Wang, S.; Gong, Y.; Wang, L.; Duan, S. Surrogate Gradient Scaling for Directly Training Spiking Neural Networks. Appl. Intell. 2023, 53, 27966–27981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.; Tong, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Huang, X.; Ma, Z. Real Spike: Learning Real-Valued Spikes for Spiking Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2022, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Volume 13672, pp. 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathi, N.; Roy, K. DIET-SNN: A Low-Latency Spiking Neural Network With Direct Input Encoding and Leakage and Threshold Optimization. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 34, 3174–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Xie, Y.; Xu, Q.; Pan, G.; Tang, H.; Chen, B. Spiking Neural Networks with Temporal Attention-Guided Adaptive Fusion for Imbalanced Multi-Modal Learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.14535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanojevic, A.; Wozniak, S.; Bellec, G.; Cherubini, G.; Pantazi, A.; Gerstner, W. High-Performance Deep Spiking Neural Networks with 0.3 Spikes per Neuron. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, E.; Studenyak, V.; Auge, D.; Knoll, A.C. Spiking Transformer Networks: A Rate Coded Approach for Processing Sequential Data. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Systems and Informatics (ICSAI) 2021, Chongqing, China, 13–15 November 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Dong, B.; Zhang, H.; Ding, J.; Heide, F.; Yin, B.; Yang, X. Spiking Transformers for Event-Based Single Object Tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 2022, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 8791–8800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Tang, L.; Yu, Z.; Lu, J.; Huang, T.J. Spike Transformer: Monocular Depth Estimation for Spiking Camera. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2022, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Volume 13667, pp. 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; Hu, J.; Zhou, Z.; Yuan, L.; Tian, Y.; Xu, B.; Li, G. Spike-Driven Transformer. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36 (NeurIPS 2023), New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2023; Volume 36, pp. 64043–64058. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.; Hao, Z.; Yu, Z. SpikingResformer: Bridging ResNet and Vision Transformer in Spiking Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 2024, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 5610–5619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, D.; Belatreche, A.; Xiao, Y.; Liang, Y.; Shan, Y.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, E.; Yang, Y. Spiking Vision Transformer with Saccadic Attention. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) 2025, Singapore, 24–28 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sanh, V.; Wolf, T.; Rush, A.M. Movement Pruning: Adaptive Sparsity by Fine-Tuning. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (NeurIPS 2020), Virtual, 6–12 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Frankle, J.; Chang, S.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Carbin, M. The Lottery Ticket Hypothesis for Pre-trained BERT Networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (NeurIPS 2020), Virtual, 6–12 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, M.; Ji, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Tian, Y.; Shao, L. HRank: Filter Pruning Using High-Rank Feature Map. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 1526–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xiao, S.; Li, B.; Yu, Z. Sparsespikformer: A Co-Design Framework for Token and Weight Pruning in Spiking Transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP) 2024, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 14–19 April 2024; pp. 6410–6414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Li, Y.; Kim, Y.; Xiao, S.; Panda, P. Spiking Transformer with Spatial-Temporal Attention. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.19764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Zhao, W.; Liu, B.; Lu, J.; Zhou, J.; Hsieh, C.J. DynamicViT: Efficient Vision Transformers with Dynamic Token Sparsification. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 34 (NeurIPS 2021), Online, 6–14 December 2021; pp. 13937–13949. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, H.; Vahdat, A.; Alvarez, J.M.; Mallya, A.; Kautz, J.; Molchanov, P. AdaViT: Adaptive Tokens for Efficient Vision Transformer. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.07658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Zhang, B.; Liu, J.; Liu, F.; Liu, Y. Dynamic Token Pruning in Plain Vision Transformers for Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) 2023, Paris, France, 2–3 October 2023; pp. 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izhikevich, E.M. Simple Model of Spiking Neurons. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2003, 14, 1569–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neftci, E.O.; Mostafa, H.; Zenke, F. Surrogate Gradient Learning in Spiking Neural Networks: Bringing the Power of Gradient-Based Optimization to Spiking Neural Networks. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2019, 36, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, S.K.; Pearmain, A.J. Unequal Error Protection with the H.264 Flexible Macroblock Ordering. In Proceedings of the Visual Communications and Image Processing 2005, Beijing, China, 12–15 July 2005; Volume 5960, p. 596032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, A.; Taba, B.; Berg, D.J.; Melano, T.; McKinstry, J.L.; di Nolfo, C.; Nayak, T.K.; Andreopoulos, A.; Garreau, G.; Mendoza, M.; et al. A Low Power, Fully Event-Based Gesture Recognition System. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 7388–7397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, H.; Ji, X.; Li, G.; Shi, L. CIFAR10-DVS: An Event-Stream Dataset for Object Classification. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orchard, G.; Jayawant, A.; Cohen, G.; Thakor, N.V. Converting Static Image Datasets to Spiking Neuromorphic Datasets Using Saccades. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1507.07629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library. In Proceedings of the the 33rd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; p. 721. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, W.; Chen, Y.; Ding, J.; Yu, Z.; Masquelier, T.; Chen, D.; Huang, L.; Zhou, H.; Li, G.; Tian, Y. SpikingJelly: An Open-Source Machine Learning Infrastructure Platform for Spike-Based Intelligence. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadi1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, K.H.; So, S.K. Using Admittance Spectroscopy to Quantify Transport Properties of P3HT Thin Films. J. Photonics Energy 2011, 1, 011112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Yu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Masquelier, T.; Huang, T.; Tian, Y. Incorporating Learnable Membrane Time Constant to Enhance Learning of Spiking Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 2641–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, S.; Deng, S.; Hai, Y.; Gu, S. Differentiable Spike: Rethinking Gradient-Descent for Training Spiking Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 34 (NeurIPS 2021), Online, 6–14 December 2021; pp. 23426–23439. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Z.; Yu, L.; Ma, Z.; Zhou, H.; Fan, X.; Tian, Y. Enhancing the Performance of Transformer-Based Spiking Neural Networks by SNN-Optimized Downsampling with Precise Gradient Backpropagation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.05954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Yu, L.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, H.; Ma, Z.; Zhou, H.; Tian, Y. Spikingformer: Spike-Driven Residual Learning for Transformer-Based Spiking Neural Network. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.11954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, K.; Zhou, Z.; Ma, Z.; Fang, W.; Chen, Y.; Shen, S.; Yuan, L.; Tian, Y. Auto-Spikformer: Spikformer Architecture Search. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.00807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, K.; Lu, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Qu, H. Spatial-Temporal Self-Attention for Asynchronous Spiking Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Second International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI) 2023, Macao, China, 19–25 August 2023; pp. 3085–3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.J.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, Q.; Deng, H.; Duan, Y.; Deng, L.J. TCJA-SNN: Temporal-Channel Joint Attention for Spiking Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2025, 36, 5112–5125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Z.; Yu, L.; Huang, L.; Fan, X.; Yuan, L.; Ma, Z.; Zhou, H.; Tian, Y. QKFormer: Hierarchical Spiking Transformer Using Q-K Attention. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 38 (NeurIPS 2024), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 9–15 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- She, X.; Dash, S.; Mukhopadhyay, S. Sequence Approximation Using Feedforward Spiking Neural Network for Spatiotemporal Learning: Theory and Optimization Methods. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) 2022, Virtual, 25–29 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

| DVS128 | CIFAR10-DVS | N-Caltech101 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDMFormer-2-256/Spikformer-2-256 | 40.88% | 42.69% | 37.93% |

| SDMFormer-1-512/Spikformer-1-512 | 39.39% | 39.72% | 37.62% |

| Model | Block | Layer | Energy Consumption |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spikformer | Embedding | First Conv | |

| Other Convs | |||

| SSA | Q,K,V | ||

| MLP | |||

| MLP | MLP1 | ||

| MLP2 | |||

| SDMFormer | Embedding | First Conv | |

| Other Convs | |||

| DMEB | Q,K,V | ||

| MLP | |||

| MLP1 | |||

| MLP2 |

| DVS128 | CIFAR10-DVS | N-Caltech101 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDMFormer-2-256/Spikformer-2-256 | 45.38% | 50.13% | 42.79% |

| SDMFormer-1-512/Spikformer-1-512 | 47.56% | 48.45% | 44.17% |

| Method | Architecture | Params | CIFAR10-DVS | DVS128 | N-Caltech101 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLIF [57] | 5Conv,2FC | 17.22 M | 74.8% | - | - |

| Dspike [58] | ResNet-18 | 11.21 M | 75.4% | - | - |

| Spikformer [8] | Spikformer-2-256 | 2.59 M | 80.9% | 97.22% | 84.59% |

| CML [59] | Spikformer-2-256 | 2.57 M | 80.9% | 98.6% | - |

| Spikingformer [60] | Spikingformer-2-256 | 2.55 M | 81.3% | 98.3% | - |

| Spike-driven Transformer [37] | Spike-driven Transformer-2-256 | 2.55 M | 80.0% | 99.3% | - |

| Auto-Spikformer [61] | Auto-Spikformer | 2.48 M | 81.2% | 98.6% | - |

| STSA [62] | STSAFormer-2-256 | 1.99 M | 79.93% | 98.7% | - |

| TCJA-SNN [63] | MS-ResNet-18 | 1.73 M | 80.7% | 99.0% | 82.5% |

| QKFormer [64] | HST-2-256 | 1.50 M | 84.0% | 98.6% | - |

| STBP-tdBN [9] | ResNet-17 | 1.40 M | 67.8% | 96.9% | - |

| SEW-ResNet [65] | Wide-7B-Net | 1.20 M | 74.4% | 97.9% | - |

| SDMFormer-Cifar10dvs (ours) | SDMFormer-2-256 | 1.09 M | 81.5 ± 0.1% | - | - |

| SDMFormer-DVS128 (ours) | SDMFormer-2-256 | 1.04 M | - | 98.61 ± 0.03% | - |

| SDMFormer-N-Caltech101 (ours) | SDMFormer-2-256 | 0.98 M | - | - | 83.54 ± 0.46% |

| Method | Architecture | Inference Throughput (img/s) |

|---|---|---|

| STSA | STSAFormer-2-256 | 105.78 |

| QKFormer | HST-2-256 | 139.05 |

| TCJA-SNN | MS-ResNet-18 | 144.46 |

| SDMFormer | SDMFormer-2-256 | 196.20 |

| Method | Architecture | Training Throughput (img/s) | Training Memory Usage (MiB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| STSA | STSAFormer-2-256 | 43.49 | 10,328 |

| QKFormer | HST-2-256 | 60.02 | 8409 |

| TCJA-SNN | MS-ResNet-18 | 57.88 | 8776 |

| SDMFormer | SDMFormer-2-256 | 57.37 | 8771 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, S.; Ran, S. SpikingDynamicMaskFormer: Enhancing Efficiency in Spiking Neural Networks with Dynamic Masking. Electronics 2026, 15, 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010189

Li J, Zhao Z, Gao S, Ran S. SpikingDynamicMaskFormer: Enhancing Efficiency in Spiking Neural Networks with Dynamic Masking. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):189. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010189

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jiao, Zirui Zhao, Shouwei Gao, and Sijie Ran. 2026. "SpikingDynamicMaskFormer: Enhancing Efficiency in Spiking Neural Networks with Dynamic Masking" Electronics 15, no. 1: 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010189

APA StyleLi, J., Zhao, Z., Gao, S., & Ran, S. (2026). SpikingDynamicMaskFormer: Enhancing Efficiency in Spiking Neural Networks with Dynamic Masking. Electronics, 15(1), 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010189