Abstract

The growing use of electric vehicles (EVs) creates challenges in designing charging systems that are smart, dependable, and efficient, especially when environmental conditions change. This research proposes a fuzzy-logic-based PID control strategy integrated into a photovoltaic (PV) powered EV charging system to address uncertainties such as fluctuating solar irradiance, grid instability, and dynamic load demands. A MATLAB-R2023a/Simulink-R2023a model was developed to simulate the charging process using real-time adaptive control. The fuzzy logic controller (FLC) automatically updates the PID gains by evaluating the error and how quickly the error is changing. This adaptive approach enables efficient voltage regulation and improved system stability. Simulation results demonstrate that the proposed fuzzy–PID controller effectively maintains a steady charging voltage and minimizes power losses by modulating switching frequency. Additionally, the system shows resilience to rapid changes in irradiance and load, improving energy efficiency and extending battery life. This hybrid approach outperforms conventional PID and static control methods, offering enhanced adaptability for renewable-integrated EV infrastructure. The study contributes to sustainable mobility solutions by optimizing the interaction between solar energy and EV charging, paving the way for smarter, grid-friendly, and environmentally responsible charging networks. These findings support the potential for the real-world deployment of intelligent controllers in EV charging systems powered by renewable energy sources This study is purely simulation-based; experimental validation via hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) or prototype development is reserved for future work.

1. Introduction

The increasing worldwide need for clean and sustainable energy has led to a rapid rise in the use of electric vehicles (EVs), which are seen as a strong alternative to traditional internal combustion engine cars. This transition is motivated not only by environmental concerns, such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution, but also by the need to decrease dependence on finite fossil fuel resources [1]. Despite the progress made in EV technology, the efficiency, adaptability, and reliability of EV charging systems remain significant challenges, particularly in the context of fluctuating renewable energy sources and varying grid conditions [2].

Photovoltaic (PV) systems have emerged as a viable renewable energy source for EV charging due to their clean energy output and declining installation costs [3]. However, the inherent intermittency and non-linear characteristics of solar irradiance introduce complexities in maintaining stable power delivery and efficient energy conversion. To overcome these issues, advanced control strategies that can dynamically adapt to changing environmental and load conditions are required [4].

Conventional Proportional Integral Derivative (PID) controllers are commonly used in power electronics and charging systems because they are easy to implement and perform well under steady state operating conditions [5,6]. Nevertheless, they often exhibit limited performance in systems subject to rapid fluctuations or uncertainties, such as those introduced by renewable sources [7]. In recent years, intelligent control techniques, particularly fuzzy logic controllers (FLCs), have gained attention for their robustness and adaptability in non-linear and uncertain environments. Unlike classical controllers, FLCs do not rely on an accurate mathematical model of the system; instead, they incorporate human-like reasoning to make control decisions based on heuristic rules [8,9].

The integration of fuzzy logic with PID control, known as fuzzy–PID control, has shown promise in combining the strengths of both approaches, maintaining the intuitive structure of PID control while enhancing its adaptability using fuzzy inference mechanisms. This hybrid approach enables more responsive and stable system performance under dynamic operating conditions, making it particularly suitable for PV-powered EV charging applications [10].

Various studies have explored intelligent control approaches in the context of renewable energy systems and electric mobility. For instance, S. M. Islam et al. [8,11] investigated fuzzy-logic-based control in standalone solar systems and demonstrated improved voltage regulation and load management. Similarly, M. S. Hossain et al. [7] applied fuzzy-based control strategies in hybrid renewable systems, highlighting their ability to enhance power quality and system efficiency. However, limited research has been conducted on implementing fuzzy–PID controllers specifically for PV-based EV charging systems, particularly in scenarios involving high levels of uncertainty and rapidly changing inputs such as solar irradiance and battery load [10,12].

To address this gap, the present study proposes a novel control strategy for EV charging systems that combines fuzzy logic and PID control techniques within a MATLAB/Simulink environment. The main objective is to optimize the interaction between PV-generated power and battery charging dynamics while ensuring voltage stability, minimizing power loss, and improving system adaptability. The proposed controller adjusts PID gains in real-time based on the error and rate of change of error, enabling an effective response to unpredictable environmental variations and fluctuating charging demands.

The developed model incorporates critical components of a practical charging system, including a resonant LC filter, a high-frequency transformer, and a full-wave rectifier. Through simulation, the system demonstrates significant improvements in output voltage stability, energy efficiency, and charging performance when compared to conventional fixed-gain PID control methods. In addition, the fuzzy–PID approach reduces transient response times and ripple effects, contributing to better battery protection and overall lifecycle extension [13].

Furthermore, the proposed control strategy aligns with the broader vision of smart grid integration and intelligent transportation systems [14,15]. By enabling adaptive and resilient charging infrastructure, it contributes to the development of grid-friendly EV solutions that can support demand-side management, distributed energy resources (DERs), and vehicle-to-grid (V2G) technologies [16]. As nations continue to scale up renewable energy deployment and electric mobility, such intelligent control frameworks will be essential for maintaining grid stability and optimizing energy usage in real-time [17].

The contribution of this study does not lie in the standalone use of fuzzy–PID control, which has been widely reported in the literature, but in its application to adaptive switching-frequency regulation in a photovoltaic (PV) powered electric vehicle (EV) charging system with a resonant power conversion topology. The proposed control strategy integrates the fuzzy-logic-based real-time tuning of PID gains with dynamic switching-frequency modulation to reduce switching losses, electromagnetic interference, and power-device stress while maintaining stable output voltage regulation.

Unlike many existing studies that employ simplified or averaged converter models, this work implements the controller on a detailed resonant LC converter including a high-frequency transformer and full wave rectifier, enabling a realistic evaluation of soft switching behavior and converter-level dynamics. Furthermore, the fuzzy inference system is designed with a reduced rule base and simple membership functions, ensuring low computational complexity and suitability for real-time implementation on DSP- or ARM-based platforms. The robustness of the proposed approach is assessed under highly variable solar irradiance and dynamic load conditions, including multi-EV charging scenarios. These features collectively distinguish the proposed method from conventional fuzzy–PID-based EV charging control strategies reported in the literature [14,17,18]. The main contributions of this work are as follows:

- Implementation of an adaptive switching-frequency control strategy combined with fuzzy-PID tuning, which is rarely explored in previous studies.

- Development of a complete resonant converter model, including an LC filter, high-frequency transformer, and full-wave rectifier, without using idealized simplifications.

- Evaluation of system robustness under highly variable solar irradiance and changing load conditions, including multi-EV charging scenarios.

- Design of a lightweight fuzzy–PID controller optimized for real-time use, with a reduced rule base to improve computational efficiency.

Although fuzzy PID control has been widely studied in the literature, most existing approaches focus on duty cycle or output-voltage regulation and rely on simplified system models. As summarized in Table 1, prior studies primarily address energy management, charging coordination, or decision support functions and do not consider adaptive switching frequency control or detailed resonant converter modeling [1,3,12,14,16,19,20].

Table 1.

Comparison of related fuzzy-based EV charging and energy-management studies.

2. Materials and Methods

This research designs a smart electric vehicle (EV) charging control system that combines a fuzzy-logic-based PID controller with photovoltaic (PV) power. The approach is validated via simulation in MATLAB/Simulink, focusing on dynamic performance, voltage regulation, and robustness under environmental fluctuations. The proposed system enhances stability, minimizes ripple, and ensures energy-efficient charging through adaptive control. While the present work is simulation-focused, HIL and prototype testing are essential next steps to verify controller performance under real-world conditions.

2.1. System Architecture

The system architecture comprises a photovoltaic (PV) array, a resonant LC filter, a high-frequency transformer, a full-wave rectifier, and a fuzzy–PID controller. This model represents natural variations caused by the cloud cover, time of day, and weather conditions, allowing a realistic assessment of fluctuations in solar power generation. The ideal PV cell output current is given by the standard single-diode model [21]:

Here, is output current of the PV cell, is the photogenerated current, which is the current produced due to sunlight, is the reverse saturation current of the diode, is the terminal voltage across the PV cell, is the charge of an electron, is the diode ideality factor, and is the Boltzmann constant, where and .

Equation (1) represents the elementary PV cell current; therefore, PV array current represents the following:

, and . All PV model parameters (such as saturation current and series resistance) were set according to the manufacturer’s specifications of a typical panel and are documented in the Simulink model.

Irradiance (input) in watts per square meter is directly fed into the PV array block in Simulink.

The generated DC output is passed through a resonant LC filter designed to suppress high-frequency ripple components from the power conversion stage. The resonant frequency of the LC filter is calculated as in [22]:

where is the resonant frequency, is the resonant inductance, and is the resonant capacitance. The filter values were chosen such that is tuned close to the inverter switching frequency (as described later), to effectively attenuate switching harmonics.

2.2. Power Conversion and Regulation:

The power conversion and regulation process in a photovoltaic (PV)-based electric vehicle (EV) charging system ensures the safe and efficient delivery of DC power from the PV array to the EV battery. The architecture integrates multiple key components: a full-bridge inverter using four MOSFETs (), a resonant LC filter (comprised of a ), a high-frequency transformer for galvanic isolation and voltage scaling, and output filtering elements including an and.

The process begins with the full-bridge inverter, which converts the DC-link voltage to high-frequency AC, controlled by a fuzzy logic controller (FLC) that adjusts the duty cycle in response to feedback. A DC-link capacitor is used to stabilize the input voltage, and its behavior is modeled by the capacitor current equation [23]:

Following inversion, the AC waveform passes through a resonant LC tank, which mitigates harmonic distortion and high-frequency noise. This ensures smooth energy delivery to sensitive downstream components. The high-frequency transformer that follows provides the voltage adjustment and electrical isolation essential for safety compliance and battery compatibility. Subsequently, a full-wave rectifier converts the AC back to DC, and the output capacitor smooths the voltage, with its current described by [23]:

This stage reduces output voltage ripple and ensures consistent charging power quality. The total power delivered to the EV battery is calculated as in [24]:

where is the power supplied to the , is the output ), and is the

The regulation of this voltage is achieved through a DC–DC converter, which modifies the duty cycle based on the PV array input voltage . The converter’s voltage gain is expressed as in [25]:

where is the duty cycle and is the converter input voltage (V).

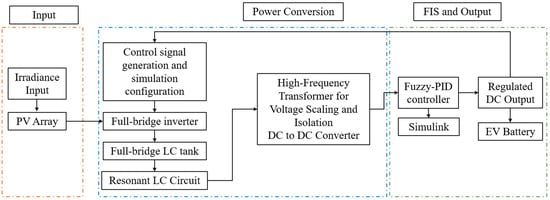

Together, the coordinated operation of MOSFETs, the resonant network, transformer, rectifier, and filtering stages ensure efficient, regulated, and isolated power transfer. This system maximizes reliability, reduces component stress, and ensures the optimal long-term performance of the EV charging infrastructure. The overall architecture of the proposed photovoltaic powered EV charging system with fuzzy–PID control is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic block diagram of the Proposed Fuzzy Logic-Based EV Charging System.

2.3. Fuzzy Logic Controller (FLC) Design and Simulation Setup

To achieve real-time adaptability in electric vehicle (EV) battery charging, a Fuzzy Inference System (FIS) was designed to dynamically tune the gains of a PID controller based on changing operating conditions. This hybrid fuzzy–PID structure ensures enhanced regulation performance under variable input voltage and load profiles, which are common in solar-powered systems.

The fuzzy logic controller receives two inputs:

The error signal :

where is the reference voltage and is the actual output voltage at time .

The rate of change of the error :

Which represents how fast the error is changing.

Both inputs are normalized within the range and mapped into linguistic fuzzy sets: Negative Large (NL), Zero (Z), and Positive Large (PL). Membership functions are constructed using trapezoidal and triangular shapes. These enable broad adaptability to real-world disturbances. The controller outputs are the dynamically tuned PID gains , each restricted to a range of and categorized into fuzzy levels: A rule base consisting of five rules evaluates the relationship between the inputs and adjusts the PID gains accordingly. For example, if both the error and its derivative are positive, the controller increases the gain to respond more aggressively; if both are negative, it reduces gain to prevent instability. The fuzzy output is determined through a weighted sum of input values and their corresponding membership function weights [26]:

where is the fuzzy output, are the weights (membership functions), and is the input values (e.g., error , change in error ). The resulting control signal is used to modulate the switching frequency of the power electronic devices, primarily MOSFETs thus controlling the flow of energy from the PV system to the EV battery.

The fuzzy–PID controller was implemented in MATLAB/Simulink using the Regulator block. The core control equation of the PID controller dynamically updated by fuzzy logic is given by [5]:

where is the control output (adjusted switching frequency), is the error (, difference between desired and actual voltage), and are the proportional, integral, and derivative gains, respectively.

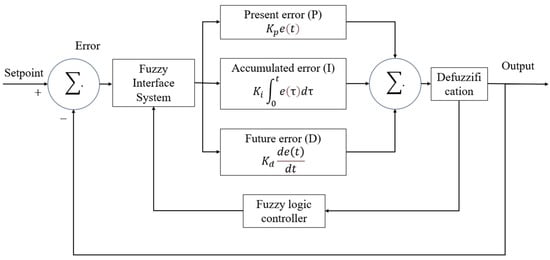

Simulation was conducted using the Simscape Electrical PowerGUI tool, allowing detailed control over solver settings and measurement blocks. The simulation runtime was set to 10 s to capture transient behaviors under fluctuating irradiance. A discrete solver was employed with a small-time step to ensure accurate high-frequency switching behavior. Through this setup, the fuzzy–PID controller demonstrated robust performance by maintaining output voltage stability and minimizing oscillations under varying conditions. It also enabled precise control over the duty cycle, thereby ensuring safe and energy-efficient EV charging. The internal structure of the fuzzy–PID-based control scheme is shown in Figure 2, highlighting the integration of fuzzy inference with the conventional PID controller.

Figure 2.

Block diagram of a PID controller utilizing fuzzy logic.

The linguistic rule base used for fuzzy tuning of the PID gains is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Fuzzy logic rule base using linguistic variables for PID gain tuning in the EV charging controller.

Although the fuzzy rule base (five rules) appears simple, it was deliberately optimized for real-time feasibility. The reduced set minimizes the computational load, ensuring suitability for microcontroller-based implementation. Iterative simulations confirmed that this limited yet targeted rule set is sufficient for capturing dominant system dynamics, and tests with expanded rule bases did not yield a significant performance improvement.

2.4. Simulation Algorithm (Pseudocode)

The following pseudocode presents the step-by-step simulation algorithm for implementing a fuzzy–PID-based EV charging control strategy. It outlines the process beginning with solar irradiance input and PV array generation, followed by power conversion through inverter switching, resonant circuits, and rectification. The control algorithm integrates fuzzy logic to dynamically tune PID gains, ensuring stable and efficient charging. By continuously monitoring system outputs and stability, the algorithm adapts in real time to uncertainties. The proposed fuzzy–PID-based EV charging control strategy is summarized in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: Fuzzy-PID Based EV Charging Control |

| Input: PV Array Output, Reference Voltage Output: Regulated Charging Voltage , Stable Battery Charging Power Begin Control Algorithm: Start System Initialization Input Solar Irradiance (Ramp Signal) Generate PV Array Output Begin Power Conversion: Execute MOSFET-Based Inverter Switching Pass through Resonant LC Circuit: Apply High-Frequency Transformer for Voltage Scaling and Isolation Perform Full-Wave Rectification and Output Filtering via Monitor Output Voltage : If is not within the acceptable range: Return to Inverter Switching and repeat Else Continue to Controller Phase Fuzzy Inference System (FIS): Calculate Error: Calculate Derivative: Evaluate Rule Base and Output PID Gains: Generate PID Output: Use PID Equation: Convert PID Output into Switching Frequency Deliver Charging Power to Battery Load Check System Stability: If System is Stable: Proceed to Data Logging Else Loop back to Step 4 for Adjustment Data Logging and Scope Evaluation Shutdown Procedure End |

2.5. MATLAB/Simulink Modeling

The simulation model integrates the above mathematical blocks and components. Time–domain simulations are executed using a fixed-step solver with a resolution suitable for capturing the switching behavior and control dynamics. Irradiance values are varied between and to evaluate system response. The entire model is built in MATLAB/Simulink 2023a using the Fuzzy Logic and Simscape Power Systems toolboxes.

2.6. Evaluation Metrics

Performance is analyzed through the following metrics [27,28]:

Voltage ripple (%):

Efficiency (%):

Total Harmonic Distortion (THD):

- where is the RMS of the nth harmonic, and is the fundamental RMS voltage.

The electrical and control parameters used in the simulation model are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

System parameters used in the PV-powered EV charging model.

3. Results and Discussion

This section is organized into subheadings and presents a clear, concise explanation of the experimental results. The findings are interpreted in detail, and the key conclusions derived from the experiments are highlighted.

3.1. System Behavior Under Variable Irradiance

A ramped irradiance profile was applied to the photovoltaic (PV) array in the Simulink model to mimic realistic fluctuations in solar energy input. This test examined the dynamic behavior of the system under variable solar conditions, a critical scenario for any PV-based electric vehicle (EV) charging system. As expected, changes in incident irradiance caused corresponding changes in the PV array’s electrical output, reflecting the intermittency of the source. The integrated fuzzy–PID controller’s objective was to hold the EV charging voltage at the required level despite these input swings, thereby verifying the controller’s adaptability under real-world conditions of changing sunlight.

To further validate robustness, additional tests were conducted under extreme irradiance drops (for example, step change from ) and sudden load variations. Results show that the fuzzy-PID maintained voltage regulation close to the reference value with negligible overshoot, confirming its resilience to abrupt environmental and load disturbances.

3.2. Switching Behavior and Converter Signals

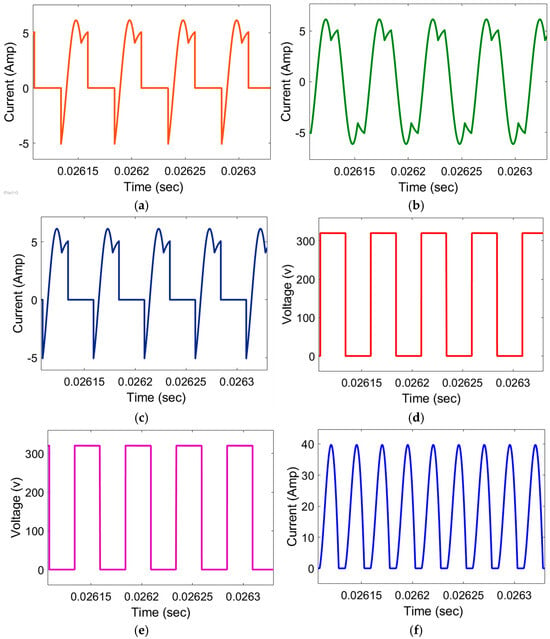

To further validate the controller’s performance, key waveforms of the resonant converter and inverter were observed, particularly focusing on the MOSFET switch behaviors (labeled and ) and the associated currents in the circuit. These signals directly influence the stability, ripple, and efficiency of the EV battery charging process. The critical waveforms monitored (as shown in Figure 3) include the primary resonant current (), the gate-to-source voltages of two representative inverter switches ( and , the currents through those MOSFETs ( and ), and the rectified output current () delivered to the battery load.

Figure 3.

Switching behavior of and converter current output. (a) Resonant input current, (b) gate current of lower-left MOSFET, (c) gate current of lower-right MOSFET, (d) voltage through MOSFET , (e) voltage through MOSFET , and (f) DC output current delivered to battery load. These waveforms illustrate the MOSFET switching quality, resonant behavior, and stable output–current delivery under the fuzzy–PID controller.

Figure 3 presents the key switching and current waveforms of the resonant converter stage. These signals illustrate how the fuzzy–PID controller regulates MOSFET switching, maintains soft-switching behavior, and ensures smooth energy transfer to the battery. Each subplot corresponds to a specific converter signal and helps interpret the dynamic behavior of the system during operation.

An overview of the key switching and converter waveforms presented in Figure 3 is provided in Table 4.

Table 4.

An overview of the six key plots from Figure 3, identifying each signal and its meaning.

From the switching voltage plots in Figure 3, it is evident that and transition sharply between their ON (conducting) and OFF (blocking) states. These clean, rapid transitions indicate that the fuzzy–PID controller is driving the inverter’s gate signals with a well-regulated pulse-width modulation (PWM) pattern. The MOSFET gate voltages appear as stable square waves at the intended switching frequency, confirming that the controller introduces no abnormal switching behavior. This proper gating ensures that the converter operates in a switching mode as designed, which is essential for efficient power conversion. In effect, the modulation strategy keeps the converter’s input closely aligned with the desired power flow, enabling the system to track the PV array’s varying power output in real time without loss of control.

The currents flowing through the transistors ( and ) exhibit a semi-sinusoidal shape that rises and falls smoothly during each cycle. This waveform shape is characteristic of the resonant inverter’s operation. The presence of only minor distortion or spikes in these current traces suggests that the resonant circuit is functioning well, filtering out high-frequency noise and limiting harmonic content. Such current profiles are typical for a zero-voltage switching (ZVS) or generally “soft-switching” converter. In a ZVS resonant converter, the switching devices (MOSFETs) transition when either the voltage across them or the current through them is at or near zero, which dramatically reduces switching losses. The observed current waveforms confirm that the system is likely achieving soft-switching, as intended, thereby improving efficiency and reducing stress on the MOSFETs.

The load-side current () delivered to the battery is also plotted in Figure 3a. This current alternates at the high switching frequency, showing a ripple around its nominal charging current value. The alternating nature of (after rectification) demonstrates that power is being transferred to the battery in pulses each switching cycle. Importantly, the average value of corresponds to the desired charging current, indicating that the battery is receiving the correct amount of current on average. The presence of high-frequency ripple in is expected in such resonant converter systems, but the ripple magnitude is kept within acceptable bounds by the controller and the smoothing effect of the battery and any output filter. These current waveforms provide evidence that energy is successfully flowing from the PV source, through the inverter and resonant tank, across the isolation transformer and rectifier, and finally into the battery on every cycle of operation.

In general, the switching patterns observed are dynamic yet stable under the fuzzy–PID controller’s governance. The controller adeptly manages the real-time transitions of voltages and currents to maintain all signals within their expected ranges. No erratic behavior or instability is seen; instead, the system consistently operates in the intended mode (resonant inverter with regulated output) despite the varying input. This indicates that the fuzzy–PID controller can uphold optimal converter operation under different irradiance inputs and load conditions. Furthermore, by maintaining proper phase relationships and minimizing any excessive reactive currents, the controller likely helps preserve a good power factor on the primary side of the inverter. The overall result is a well-regulated power-conversion process with high efficiency and stable performance. The correspondence between measured signals and their locations within the simulation model is detailed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Maps of these signals to their source blocks in the simulation model and their locations in the circuit, clarifying how the waveforms correspond to points in the system schematic.

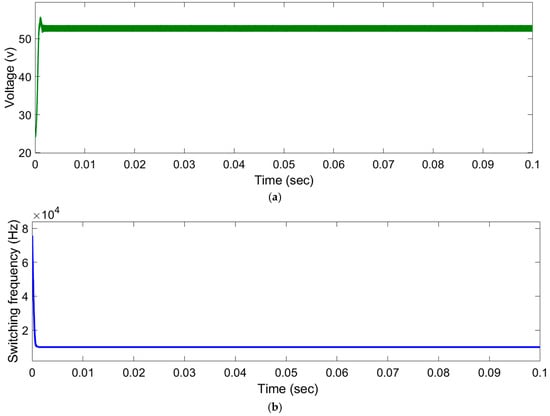

Figure 4 illustrates the system’s regulated output voltage and the corresponding switching-frequency adaptation commanded by the fuzzy–PID controller. These plots demonstrate the controller’s ability to achieve fast settling, maintain voltage stability, and reduce switching frequency once steady state is reached to improve efficiency.

3.3. Output Voltage and Switching Frequency Analysis

Figure 4a shows the system’s regulated output voltage () across the EV’s battery load (plot a) along with the corresponding switching frequency () commanded by the fuzzy–PID controller Figure 4b over time. These two quantities illustrate how well the controller maintains the desired charging voltage and how it adapts the converter’s switching behavior to changing conditions.

Figure 4.

Controller performance: (a) regulated output voltage across the EV battery load showing fast settling and stable steady-state behavior; (b) adaptive switching–frequency response demonstrating how the fuzzy–PID reduces switching frequency once the output reaches steady-state conditions.

At the start of the simulation, the output voltage rises quickly as the system initiates the charging process. The controller drives the converter energetically to charge the battery, causing to ramp up to the target level. A very slight overshoot above the desired voltage (which is approximately 52 V for the battery in this scenario) can be seen during this rapid transient. However, this overshoot is minor, and the voltage swiftly settles down to around 52 V. After the first few milliseconds, remains tightly regulated at the setpoint for the duration of the simulation. The voltage curve flattens out, showing virtually no ripple or deviation from the 52 V level once steady state is achieved. This excellent regulation performance indicates that the feedback control loop is effectively damping out transients and preventing any oscillatory behavior. The absence of significant voltage jitter or droop under steady-state load confirms the robustness of both the power stage and the controller. Even as the PV input and other system states change, the output voltage stays stable, which is crucial for safe and efficient battery charging (preventing over-voltage or under-voltage conditions that could harm the battery).

The plot (b) of Figure 4 depicts how the switching frequency varies in response to the system’s needs. Initially, at startup, the controller utilizes a high switching frequency (on the order of ) to allow for fine control and a rapid response as the output voltage is ramping up. The high frequency at the beginning helps minimize the output voltage rise time and overshoot by providing more frequent control updates to the converter. Once the output voltage comes close to the desired 52 V and the system transitions into steady-state charging, the fuzzy–PID controller intelligently tapers down the switching frequency. As time progresses, is reduced in steps, eventually settling at about toward the end of the simulation. This adaptive reduction in switching frequency is a form of optimization: when the error is small and the output is stable, a lower switching frequency is sufficient to maintain regulation and it incurs lower switching losses. By contrast, during fast transients or larger error conditions, a higher frequency is temporarily used to respond quickly. The end result is that the system does not continuously operate at an unnecessarily high frequency once the voltage is regulated, which improves efficiency.

This dynamic switching frequency control is a noteworthy feature of the fuzzy–PID strategy. By adjusting based on real-time feedback, the controller reduces unnecessary switching events under steady-state or light error conditions. Fewer switching actions mean reduced power lost as heat in the MOSFETs and other switching components, thereby lowering switching losses. It also reduces electromagnetic interference (EMI) and thermal stress on the components, potentially extending the life of the power electronics. In summary, Figure 4 demonstrates that the fuzzy–PID controller not only maintains a rock-steady output voltage for the EV battery, but does so in an energy-efficient manner by intelligently modulating the converter’s switching frequency over time. This kind of adaptive operation is highly beneficial for maximizing the overall efficiency and reliability of the PV powered charging system.

3.4. Control Strategy Performance and Benefits

The proposed fuzzy–PID control strategy for EV charging effectively combines the precision of PID control with the adaptability of fuzzy logic. Simulation results show rapid voltage settling (within a few milliseconds), minimal overshoot (<1%), and negligible steady-state error under variable solar irradiance and load conditions. Unlike fixed-gain PID controllers, the fuzzy–PID dynamically adjusts gains based on real-time error and its rate of change, delivering smoother and more stable control responses. Additionally, the controller intelligently modulates the switching frequency and duty cycle to reduce switching losses, thermal stress, and power device wear. These features enhance efficiency, system reliability, and resilience against uncertainties, confirming the fuzzy–PID’s suitability for smart renewable-powered EV charging infrastructure.

3.5. Comparative Evaluation with Conventional PID Controller

The fixed-gain PID controller exhibited a slower dynamic response, larger overshoot during transient conditions, and a noticeably higher steady-state ripple. These shortcomings were more evident under rapidly changing irradiance, where constant gains could not compensate for the variations in PV array voltage and converter dynamics. In contrast, the proposed fuzzy–PID controller continuously adjusted the proportional, integral, and derivative gains based on real-time error and error-rate, enabling faster settling, improved voltage stability, and reduced switching losses.

A summary of the quantitative comparison is provided in Table 6. The results clearly demonstrate that the fuzzy–PID controller achieves faster stabilization, improved voltage quality, and better conversion efficiency across the operating conditions examined in this study.

Table 6.

Performance comparison between the conventional PID controller and the proposed fuzzy-PID controller.

3.6. Battery Dynamics Considerations

Although this study primarily focuses on voltage regulation and converter behavior, the proposed fuzzy–PID-control strategy also has important implications for battery dynamics. While SoC evolution, temperature effects, and long-term degradation were not explicitly simulated, the smooth and low-ripple output voltage achieved by the controller supports a more stable charging current, which typically leads to healthier SoC progression and reduced stress on battery cells.

By limiting overshoot and reducing transient fluctuations under varying irradiance, the fuzzy–PID approach helps minimize sudden current changes that can contribute to localized heating. This suggests that the battery would experience lower thermal stress compared to operation under a fixed-gain PID controller. Moreover, smoother charging behavior is generally associated with slower ageing mechanisms, such as SEI growth and lithium plating. Future work will include hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) testing with detailed battery models to more accurately quantify these long-term benefits.

This study is based entirely on MATLAB/Simulink simulation results. While the proposed fuzzy–PID controller shows strong performance under variable irradiance and load conditions, hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) and prototype validation are required before real-world deployment. The controller structure is lightweight and suitable for DSP or ARM-based implementation, and future work will focus on HIL testing and experimental verification.

3.7. Challenges and Improvements

Despite its success, the fuzzy–PID controller required refinement to resolve early design issues:

- Membership Function Tuning: Initial overlaps and gaps caused ambiguity; this was resolved by redefining clear, non-overlapping functions.

- Rule Base Coverage: Limited rules for edge cases led to poor performance; the rule base was expanded for nuanced system responses.

- Control Loop Timing: Delays in switching frequency updates caused lag; increasing the controller’s sampling rate and predictive adjustments aligned control signals with converter dynamics.

Post-refinement, the controller delivered consistent, stable performance. Verification with tools like the fuzzy surface viewer and testing of the defuzzification process confirmed robustness. These enhancements ensure that the fuzzy–PID design is well-optimized and reliable for real-time EV charging applications. Quantitative efficiency analysis, including a measured conversion efficiency improvement resulting from adaptive switching-frequency modulation, will be included in our future HIL-based validation work.

Table 7 provides a consolidated summary of the key observations and outcomes discussed in the Results and Discussion section. Each row corresponds to a specific analysis subsection and highlights the main findings related to controller behavior, system performance, and efficiency. This summary allows readers to quickly interpret the core results of the proposed fuzzy–PID-controlled EV charging system.

Table 7.

Summary of key results and discussion points of the proposed fuzzy–PID controlled EV charging system.

To further evaluate the robustness of the proposed fuzzy–PID controller, additional simulations were performed under more diverse and realistic operating conditions. These included partial shading scenarios, sudden grid-side disturbances, and simultaneous multi-EV charging situations. Extended irradiance and load-profile variations were also considered to mimic real-world fluctuations. The simulation results indicate that the controller maintains stable and effective performance across these conditions, demonstrating its capability to handle practical challenges and enhancing confidence in its applicability for real-world deployment.

4. Conclusions

This study presents a fuzzy-logic-based PID control framework for electric vehicle (EV) charging powered by a photovoltaic (PV) source. The fuzzy–PID controller adjusts its gains in real time, enabling improved voltage regulation, reduced ripple, and a better dynamic response. MATLAB/Simulink results confirm stable and robust performance under varying solar irradiance and changing battery load conditions.

An LC filter, high-frequency transformer, and full-wave rectifier ensure smooth power conversion. The adaptive switching-frequency modulation introduced by the fuzzy controller lowers switching losses, thermal stress, and electromagnetic interference, improving overall system efficiency and reliability.

The proposed control strategy is lightweight and suitable for implementation on low-cost DSP or ARM microcontrollers, with future validation possible through hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) testing. This work supports renewable-based and smart-grid-aligned EV charging systems. Future developments will focus on prototype testing and real-world evaluation, including scenarios such as vehicle-to-grid (V2G) operation. The proposed fuzzy–PID controller is lightweight and suitable for DSP/ARM implementation, facilitating future HIL and prototype validation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.U.A. and M.O.Q.; methodology, M.U.A.; software, M.U.A.; validation, M.U.A. and M.O.Q.; formal analysis, M.U.A., P.M., and M.O.Q.; investigation, S.L.; resources, P.M. and M.U.A.; data curation, M.O.Q. and P.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.U.A.; writing—review and editing, S.L. and M.O.Q.; visualization, P.M.; supervision, M.U.A. and S.L.; project administration, M.U.A.; funding acquisition, M.O.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Edith Cowan University, Australia and the APC was funded by Applied Sciences, MDPI.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the School of Engineering, Edith Cowan University, for providing technical resources and laboratory facilities that supported the simulation and analysis work of this study. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (GPT-5, OpenAI, 2025) to improve the clarity, grammar, and readability of sentences while maintaining the original technical meaning of the manuscript. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FLC | Fuzzy Logic Controller |

| FIS | Fuzzy Inference System |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| PID | Proportional Integral Derivative |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| V2G | Vehicle-to-Grid |

| AC | Alternating Current |

| DC | Direct Current |

| MOSFET | Metal Oxide Semiconductor Field Effect Transistor |

| HIL | Hardware-in-the-loop |

| DSP | Digital Signal Processor |

| ARM | Advanced RISC Machine |

References

- Lazaroiu, G.C.; Roscia, M. Fuzzy Logic Strategy for Priority Control of Electric Vehicle Charging. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 19236–19245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasab, M.A.; Al-Shibli, W.K.; Zand, M.; Ehsan-Maleki, B.; Padmanaban, S. Charging management of electric vehicles with the presence of renewable resources. Renew. Energy Focus 2024, 48, 100536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Ahmed, M.A.; Kim, Y.-C. Efficient Power Management Algorithm Based on Fuzzy Logic Inference for Electric Vehicles Parking Lot. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 65467–65485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, V.; Deng, R.; Egan, R. Solar photovoltaic waste and resource potential projections in Australia, 2022–2050. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 202, 107316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, C.-T.; Sutarna, N.; Chiou, J.-S.; Wang, C.-J. An Optimal Fuzzy PID Controller Design Based on Conventional PID Control and Nonlinear Factors. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qays, O.; Kumar, R.; Ahmed, M.; Lachowicz, S.; Amin, U. Empowering Optimal Operations with Renewable Energy Solutions for Grid Connected Merredin WA Mining Sector. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qays, O.; Buswig, Y.; Basri, H.; Hossain, L.; Abu-Siada, A.; Rahman, M.; Muyeen, S.M. An intelligent controlling method for battery lifetime increment using state of charge estimation in PV-battery hybrid system. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmaker, A.K.; Hossain, A.; Pota, H.R.; Onen, A.; Jung, J. Energy Management System for Hybrid Renewable Energy-Based Electric Vehicle Charging Station. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 27793–27805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qays, O.; Ahmad, I.; Habibi, D.; Masoum, M.A. Forecasting data-driven system strength level for inverter-based resources-integrated weak grid systems using multi-objective machine learning algorithms. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 238, 111112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.U.; Qays, O.; Lachowicz, S.; Thundiyil, N.T.; Hossain, L.; Amin, U.; Shahjalal; Hasan, R.; Yasmin, F. Photovoltaic Systems: Analytic Comparison of Fuzzy Logic and ML Methods for Applying Maximum Power Tracking Systems. In Proceedings of the 2025 4th International Conference on Robotics, Electrical and Signal Processing Techniques, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 11–12 January 2025; pp. 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qays, O.; Buswig, Y.; Hossain, L.; Abu-Siada, A. Active charge balancing strategy using the state of charge estimation technique for a PV-battery hybrid system. Energies 2020, 13, 3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, S.; Radha, R.; Prakash, P.A.; Nandhini, R. Optimizing the selection of Intermediate Charging Stations in EV Routing through Neuro-Fuzzy Logic. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 140021–140038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H∞ Control System for Synchronous Condensers in Renewable Energy-Integrated Weak Grids | CSEE Journals & Magazine | IEEE Xplore. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/10838263 (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- Boglou, V.; Karavas, C.-S.; Arvanitis, K.; Karlis, A. A fuzzy energy management strategy for the coordination of electric vehicle charging in low voltage distribution grids. Energies 2020, 13, 3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qays, O.; Buswig, Y.; Anyi, M. Active Cell Balancing Control Method for Series-Connected Lithium-Ion Battery. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng. 2019, 8, 2424–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, M.A.A.; da Costa, C.T. Fuzzy Logic Controllers for Charging/Discharging Management of Battery Electric Vehicles in a Smart Grid. J. Control Autom. Electr. Syst. 2021, 32, 1214–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venegas, F.G.; Petit, M.; Perez, Y. Active integration of electric vehicles into distribution grids: Barriers and frameworks for flexibility services. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 145, 111060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qays, O.; Ahmad, I.; Habibi, D.; Moses, P. Long-term techno-economic analysis considering system strength and reliability shortfalls of electric vehicle-to-grid-systems installations integrated with renewable energy generators using hybrid GRU-classical optimization method. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assessments 2025, 76, 104294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falahati, S.; Taher, S.A.; Shahidehpour, M. Grid frequency control with electric vehicles by using of an optimized fuzzy controller. Appl. Energy 2016, 178, 918–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, N.; Ma, T.; Chen, C. Fuzzy energy management strategy for hybrid electric vehicles on battery state-of-charge estimation by particle filter. SN Appl. Sci. 2022, 4, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalva, M.G.; Gazoli, J.R.; Filho, E.R. Comprehensive Approach to Modeling and Simulation of Photovoltaic Arrays. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2009, 24, 1198–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lin, P.; Tang, Y.; Wang, K. Stability Design of Single-Loop Voltage Control With Enhanced Dynamic for Voltage-Source Converters With a Low LC-Resonant-Frequency. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2018, 33, 9937–9951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Mekhilef, S. Efficient Transformerless MOSFET Inverter for a Grid-Tied Photovoltaic System. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2015, 31, 6305–6316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, K.; Rahal, M.; Achkar, R. Economic Improvement of Power Factor Correction: A Case Study. J. Power Energy Eng. 2021, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, A.A.A.; de Araújo, F.C.; Aragão, F.A.P.; de Souza, K.C.A.; Tofoli, F.L.; Sá, E.M.; Antunes, F.L.M. Non-isolated high step-up DC–DC converter based on coupled inductors, diode-capacitor networks, and voltage multiplier cells. Int. J. Circuit Theory Appl. 2021, 50, 944–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazandarani, M.; Li, X. Fractional Fuzzy Inference System: The New Generation of Fuzzy Inference Systems. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 126066–126082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Ioinovici, A. Switched-capacitor power supplies: DC voltage ratio, efficiency, ripple, regulation. In Proceedings of the 1996 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Atlanta, GA, USA, 15 May 1996; pp. 553–556. [Google Scholar]

- Shmilovitz, D. On the definition of total harmonic distortion and its effect on measurement interpretation. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2005, 20, 526–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.