A Functionally Guided U-Net for Chronic Kidney Disease Assessment: Joint Structural Segmentation and eGFR Prediction with a Structure–Function Consistency Loss

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Proposed Method

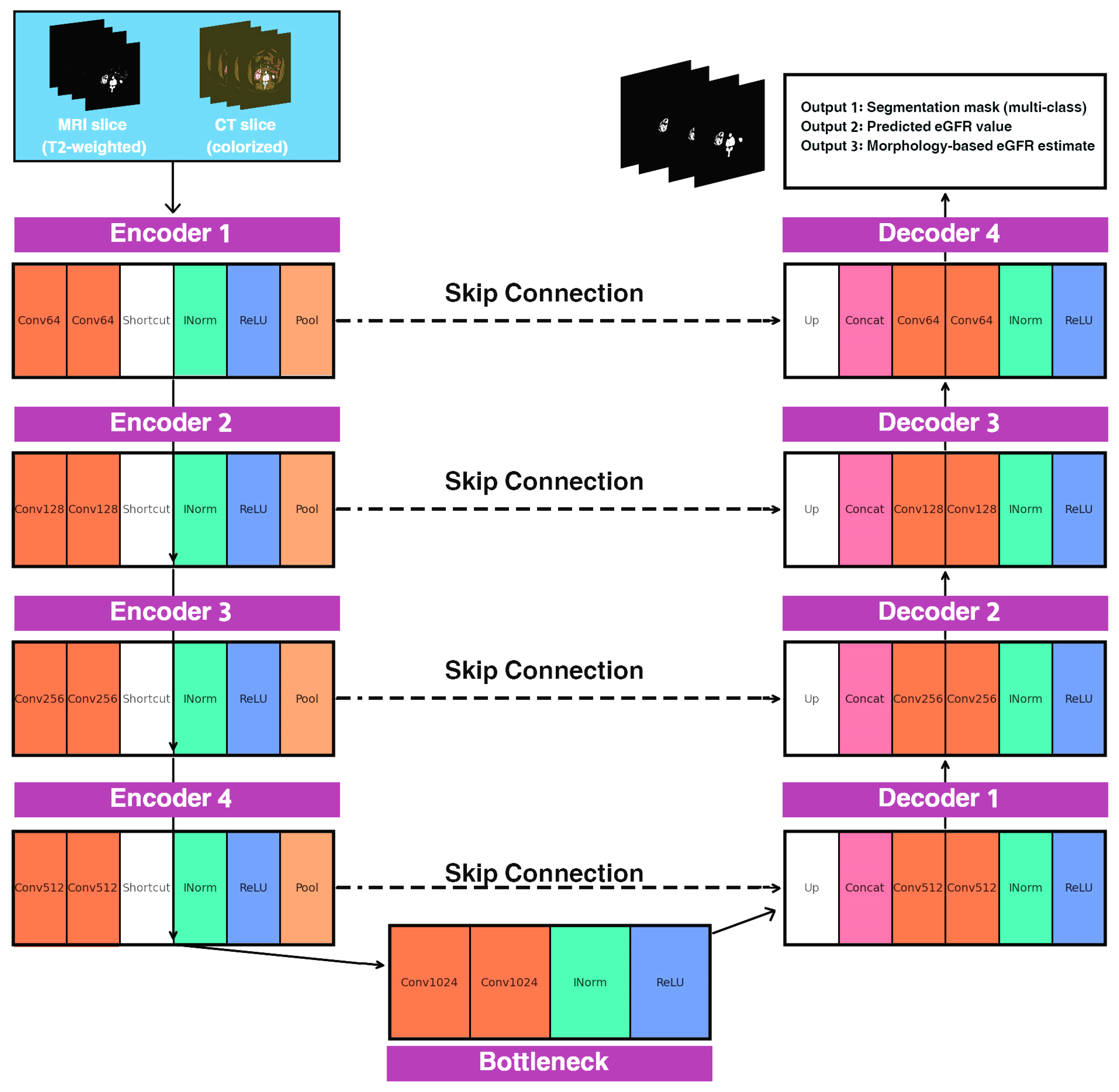

2.1. Overview of the FG-CKD-UNet Architecture

| Algorithm 1. FG-CKD-UNet Architecture. |

| Input: Kidney image X Output: Segmentation mask Ŝ, predicted eGFR ŷ 1: Encoder 2: Initialize encoder with L levels of residual convolution blocks 3: for l = 1 to L do 4: Fe(l) = ResidualBlock(Downsample(Fe(l − 1))) 5: end for 6: Bottleneck 7: Fb = ResidualBlock(Fe(L)) 8: Segmentation Decoder 9: for l = L down to 1 do 10: Fd(l) = Concat(Upsample(Fd(l + 1)), Fe(l)) 11: Fd(l) = ConvBlock(Fd(l)) 12: end for 13: Ŝ = Softmax(Conv1x1(Fd(1))) 14: Morphological Biomarker Extraction 15: Compute binary masks Mk from Ŝ 16: Compute volumetric biomarkers Vk = Σ Mk 17: Compute cortical thickness Tc via distance transform 18: Compute cortex–medulla ratio CMR = Vc/(Vm + ε) 19: B = [Vc, Vm, Tc, CMR, …] 20: Functional Prediction 21: ŷ = MLP(GlobalAveragePooling(Fb)) 22: Morphology-Derived Functional Estimate 23: ŷmorph = g(B) 24: Structure–Function Consistency 25: Lseg = DiceLoss(Ŝ, Strue) + CrossEntropy(Ŝ, Strue) 26: Lfunc = 0.7*MAE(ŷ, ytrue) + 0.3*MSE(ŷ, ytrue) 27: Lsf = α|ŷmorph − ytrue| + β|ŷ − ŷmorph| 28: Final Optimization 29: Ltotal = λ1*Lseg + λ2*Lfunc + λ3*Lsf 30: Update all network weights using AdamW optimizer Return Ŝ, ŷ |

2.2. Encoder Design

| Algorithm 2: Encoder Design |

| Input: Kidney image |

| Output: Multi-scale encoder feature maps and bottleneck representation |

| Initialize Encoder Parameters |

| Set number of encoder levels , convolution kernel size , activation function , and normalization layer = InstanceNorm |

| Initialize convolution weights |

| Stage 1—Initial Feature Extraction |

| Apply two convolutional layers to input : |

| Construct residual output: |

| Stage 2 to L—Hierarchical Feature Encoding |

| For each encoder level : |

| a. Downsample previous output using max-pooling: |

| b. Apply residual block: |

| c. Add residual connection: |

| Stage L—Bottleneck Representation |

| After the final encoder stage, set: |

| Return Encoder Outputs |

| Output multi-scale feature maps |

| and bottleneck embedding |

2.3. Segmentation Decoder

| Algorithm 3: Segmentation Decoder |

| Algorithm 3: Segmentation Decoder of FG-CKD-UNet Input: Bottleneck feature map F_bottleneck, encoder feature maps {F_e(1), …, F_e(L)} Output: Multi-class segmentation mask Ŝ 1: F_d(L) ← UpSample(F_bottleneck) 2: for l = L down to 1 do 3: # Skip Connection Fusion 4: F_concat ← Concat(F_d(l), F_e(l)) 5: 6: # Convolutional Refinement Block 7: F_refine ← σ(Conv3 × 3(W1(l), F_concat)) 8: F_refine ← σ(Conv3 × 3(W2(l), F_refine)) 9: 10: # Prepare for next decoding stage 11: if l > 1 then 12: F_d(l–1) ← UpSample(F_refine) 13: end if 14: end for 15: 16: # Final Projection to Class Probabilities 17: Ŝ ← Softmax(Conv1 × 1(W_out, F_d(0))) 18: 19: return Ŝ |

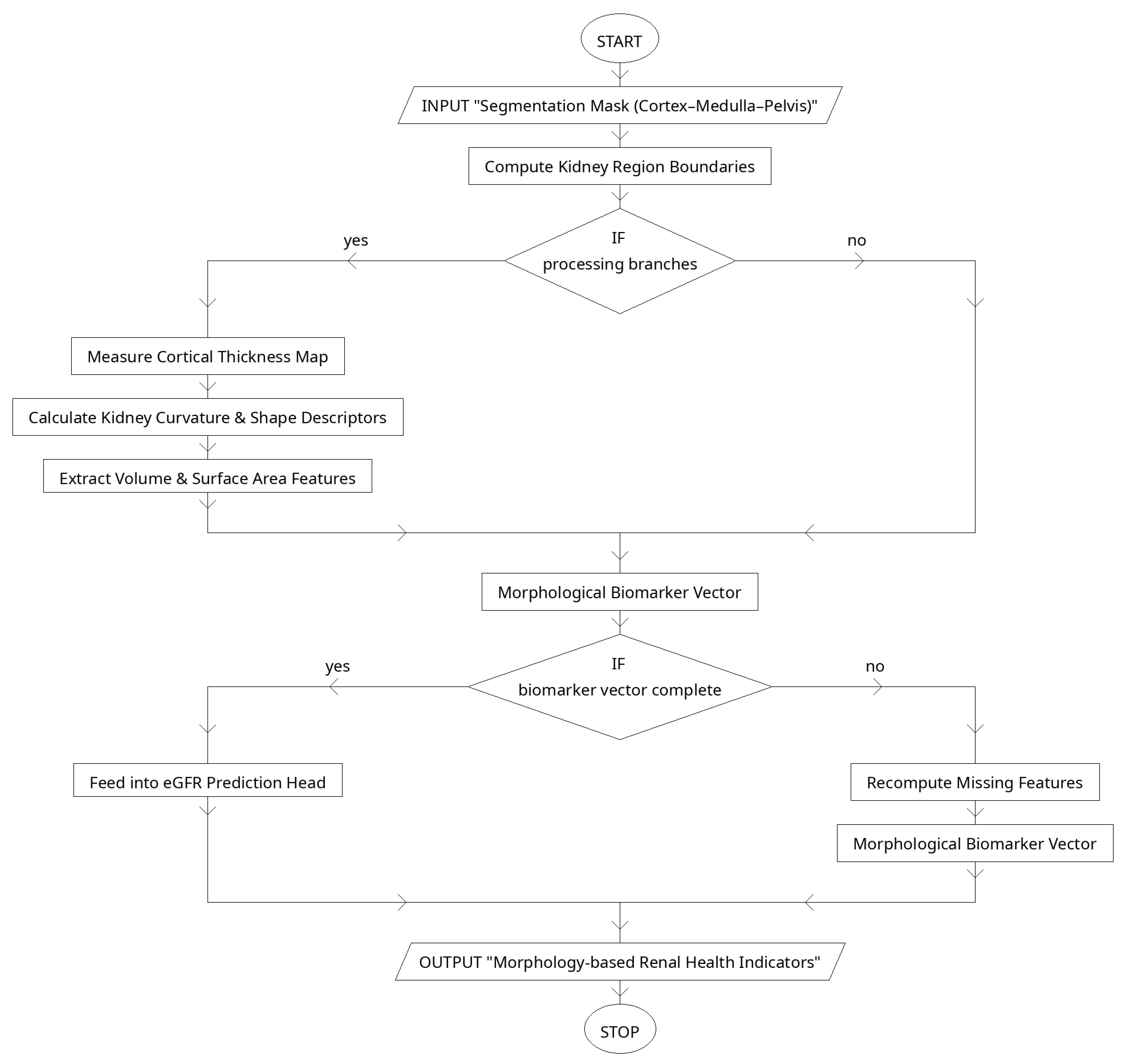

2.4. Morphological Biomarker Extraction

2.5. Structure–Function Consistency Loss

3. Simulation and Results

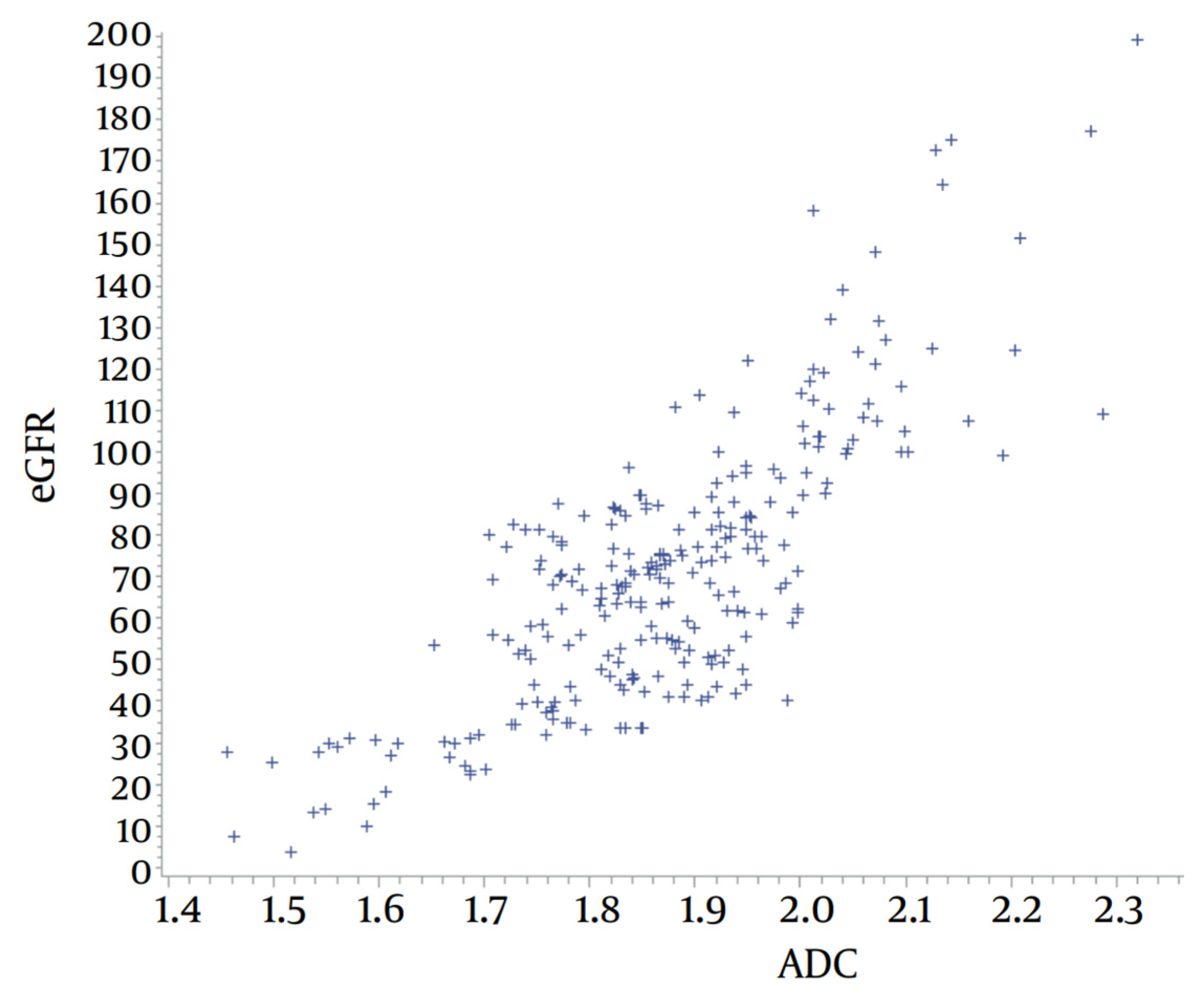

3.1. Datasets Used

3.2. Data Preprocessing and Augmentation

3.3. Experimental Setup/Training Configuration

3.4. Evaluation Metrics

3.5. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Results Analysis

4.2. Longitudinal Extension and Clinical Integration

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zdravkova, I.; Tilkiyan, E.; Ivanov, H.; Lambrev, A.; Dzhongarova, V.; Kraleva, G.; Kirilov, B. Acute Kidney Injury and Chronic Kidney Disease Associated with a Genetic Defect: A Report of Two Cases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charkiewicz-Szeremeta, K.; Sawicka-Śmiarowska, E.; Czarnecka, D.; Dubatówka, M.; Gąsior, Z.; Hryszko, T.; Jankowski, P.; Knapp, M.; Kosior, D.A.; Kubica, A.; et al. Impairment of Kidney Function in Patients with Chronic Coronary Syndromes. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmarathne, G.; Bogahawaththa, M.; McAfee, M.; Rathnayake, U.; Meddage, D.P.P. On the Diagnosis of Chronic Kidney Disease Using a Machine Learning-Based Interface with Explainable Artificial Intelligence. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2024, 22, 200397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovesdy, C.P. Epidemiology of Chronic Kidney Disease: An Update 2022. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2022, 12, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junejo, S.; Chen, M.; Ali, M.U.; Ratnam, S.; Malhotra, D.; Gong, R. Evolution of Chronic Kidney Disease in Different Regions of the World. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezk, N.G.; Alshathri, S.; Sayed, A.; Hemdan, E.E.-D. Explainable AI for Chronic Kidney Disease Prediction in Medical IoT: Integrating GANs and Few-Shot Learning. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obaid, W.; Hussain, A.; Rabie, T.; Mansoor, W. Noisy Ultrasound Kidney Image Classifications Using Deep Learning Ensembles and Grad-CAM Analysis. AI 2025, 6, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zi-An, Z.; Chen, Y.; Mao, Y.-J.; Cheung, J.C.-W. Enhancing thyroid nodule detection in ultrasound images: A novel YOLOv8 architecture with a C2fA module and optimized loss functions. Technologies 2025, 13, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maçin, G.; Genç, F.; Taşcı, B.; Dogan, S.; Tuncer, T. KidneyNeXt: A Lightweight Convolutional Neural Network for Multi-Class Renal Tumor Classification in Computed Tomography Imaging. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulandaivelu, G.; Suchitra, M.; Pugalenthi, R.; Lalit, R. An Implementation of Adaptive Multi-CNN Feature Fusion Model with Attention Mechanism with Improved Heuristic Algorithm for Kidney Stone Detection. Comput. Intell. 2025, 41, e70028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharon, J.J.; Anbarasi, L.J. An attention enhanced dilated bottleneck network for kidney disease classification. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loganathan, G.; Palanivelan, M. An explainable adaptive channel weighting-based deep convolutional neural network for classifying renal disorders in computed tomography images. Comput. Biol. Med. 2025, 192, 110220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaki, J.; Uçar, A. An efficient and robust approach using inductive transfer-based ensemble deep neural networks for kidney stone detection. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 32894–32910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuayqil, S.N.; Abd El-Ghany, S.; Abd El-Aziz, A.A.; Elmogy, M. KidneyNet: A Novel CNN-Based Technique for the Automated Diagnosis of Chronic Kidney Diseases from CT Scans. Electronics 2024, 13, 4981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingol, H.; Yildirim, M.; Yildirim, K.; Alatas, B. Automatic classification of kidney CT images with relief based novel hybrid deep model. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2023, 9, e1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liao, Y.; Gao, L.; Li, P.; Huang, J.; Xu, P.; Fu, B.; Zhu, Q.; Lai, X. MAL-Net: A Multi-Label Deep Learning Framework Integrating LSTM and Multi-Head Attention for Enhanced Classification of IgA Nephropathy Subtypes Using Clinical Sensor Data. Sensors 2025, 25, 1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Lv, W.; Shang, Z. Identifying functional subtypes of IgA nephropathy based on three machine learning algorithms and WGCNA. BMC Med. Genom. 2024, 17, 61. [Google Scholar]

- Jeng, S.-L. U-Net Inspired Transformer Architecture for Multivariate Time Series Synthesis. Sensors 2025, 25, 4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, J.; Man, J. UNet–Transformer Hybrid Architecture for Enhanced Underwater Image Processing and Restoration. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, A.J.; Buchanan, C.E.; Allcock, T.; Scerri, D.; Cox, E.F.; Prestwich, B.L.; Francis, S.T. T2-Weighted Kidney MRI Segmentation (v1.0.0) [Data Set]. Zenodo. 2021. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/5153568 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Basak, S. Kidney CT Colorized (Normal, Cyst, Tumor, Stone). Kaggle Dataset. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/shuvokumarbasakbd/kidney-ct-colorized-normal-cyst-tumor-stone (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Al-Salman, O. Unet-Kidney-eGFR: Official Implementation of the FG-CKD-UNet Framework. GitHub Repository. 2025. Available online: https://github.com/AsharfNadir88/Unet-Kidney-eGFR (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Alenezi, A.; Mayya, A.; Alajmi, M.; Almutairi, W.; Alaradah, D.; Alhamad, H. Application of the U-Net Deep Learning Model for Segmenting Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography Myocardial Perfusion Images. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AL Qurri, A.; Almekkawy, M. Improved UNet with Attention for Medical Image Segmentation. Sensors 2023, 23, 8589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Mei, J.; Li, X.; Lu, Y.; Yu, Q.; Wei, Q.; Luo, X.; Xie, Y.; Adeli, E.; Wang, Y.; et al. TransUNet: Rethinking the U-Net architecture design for medical image segmentation through the lens of transformers. Med. Image Anal. 2024, 97, 103280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Han, Y.; Yao, L.; Wu, X.; Li, K.; Yin, J. MS-UNet: Multi-Scale Nested UNet for Medical Image Segmentation with Few Training Data Based on an ELoss and Adaptive Denoising Method. Mathematics 2024, 12, 2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkharsan, A.; Ata, O. HawkFish Optimization Algorithm: A Gender-Bending Approach for Solving Complex Optimization Problems. Electronics 2025, 14, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Sun, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhao, X. Image segmentation network based on enhanced dual encoder. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 35983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, A.; Viriri, S. FPN-SE-ResNet Model for Accurate Diagnosis of Kidney Tumors Using CT Images. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buriboev, A.S.; Khashimov, A.; Abduvaitov, A.; Jeon, H.S. CNN-Based Kidney Segmentation Using a Modified CLAHE Algorithm. Sensors 2024, 24, 7703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Kidney Foundation. eGFR Calculator for Professionals. Available online: https://www.kidney.org/professionals/gfr_calculator (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Kanpittaya, J.; Jaimook, P.; Thongkrau, T.; Keeratikasikorn, C.; Sawanyawisuth, K. Calculating eGFR Using Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC) Values Obtained Through MR Imaging. Iran. J. Radiol. 2018, 15, e13682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, M.; Shimbo, T.; Horio, M.; Ando, M.; Yasuda, Y.; Komatsu, Y.; Masuda, K.; Matsuo, S.; Maruyama, S. Longitudinal Study of the Decline in Renal Function in Healthy Subjects. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Task/Disease Focus | Methodology | Key Contribution | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rezk et al. [6] | CKD prediction | GANs + Few-shot + Explainable AI | Accurate CKD prediction in low-data IoT settings | No integration of imaging data; cannot capture structural kidney changes |

| Obaid et al. [7] | Kidney classification under noise | Deep ensembles + Grad-CAM | Noise-resilient ultrasound classification with visual interpretation | No segmentation; model depends heavily on image quality and lacks functional correlation |

| Wang et al. [8] | Thyroid lesion detection (transferable concept) | YOLOv8 + C2fA module | Strong example of architectural refinement improving detection | Not kidney-related; does not model multi-task structure–function relationships |

| Maçin et al. [9] | Renal tumor classification | Lightweight CNN (KidneyNeXt) | Computationally efficient multi-class tumor detection | Focuses on tumors only; does not address CKD or functional decline |

| Kulandaivelu et al. [10] | Kidney stone detection | Multi-CNN fusion + Attention + Heuristic optimization | Strong performance via fusion and metaheuristic tuning | Does not consider anatomical segmentation or CKD-specific biomarkers |

| Sharon & Anbarasi [11] | Kidney disease classification | Attention-enhanced dilated bottleneck network | Improved feature extraction and discrimination | Single-task model; no structural insight or morphological analysis |

| Loganathan & Palanivelan [12] | Renal disorder classification | Adaptive channel-weighted CNN | Transparent, explainable channel relevance modeling | Does not integrate segmentation; limited physiological interpretation |

| Chaki & Uçar [13] | Kidney stone detection | Inductive transfer learning + Ensemble DNNs | Strong transferability and generalization | Focuses on stones; no application to chronic kidney disease or structure–function coupling |

| Almuayqil et al. [14] | CKD diagnosis | KidneyNet CNN | Automated CKD detection directly from CT | Lacks anatomical segmentation; cannot explain morphological basis of CKD |

| Bingol et al. [15] | Kidney CT classification | Hybrid DL + Relief feature selection | Enhances feature relevance and reduces redundancy | No multi-task learning; limited clinical interpretability |

| Wang et al. [16] | IgA nephropathy subtype classification | LSTM + Multi-head attention (MAL-Net) | Models complex temporal clinical patterns | No imaging component; cannot capture renal structural changes |

| Ren et al. [17] | IgA nephropathy subtype discovery | ML models + WGCNA | Identifies molecular-level disease subtypes | No imaging or structural analysis; not applicable to CKD segmentation |

| Dataset | Modality | Total Samples | Classes/Labels | Annotations | Resolution | Purpose in Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2-Weighted Kidney MRI Segmentation [20] | MRI (T2-weighted) | 100 subjects (including repeated scans) | Healthy vs. CKD | Manual kidney masks | Varies per subject | Training segmentation, extracting CKD-related morphological biomarkers |

| Kidney CT Colorized (Normal–Cyst–Tumor–Stone) [21] | CT (colorized) | 12,446 images | 4 classes: Normal, Cyst, Tumor, Stone | Image-level labels | 150 × 150 px (average) | Enhancing anatomical variability and robust structural feature learning |

| Category | Specification |

|---|---|

| Operating System | Windows 11 Pro, 64-bit |

| Programming Language | Python 3.10 |

| Deep Learning Framework | PyTorch 2.2.1 (CUDA 12.2) |

| Supporting Libraries | NumPy 1.26, SciPy 1.12, scikit-image 0.22, OpenCV 4.9, TorchIO 0.19 |

| GPU | NVIDIA RTX 4090 (24 GB GDDR6X) |

| CPU | Intel Core i9-13900K (24 cores, 32 threads) |

| RAM | 64 GB DDR5 6000 MHz |

| Storage | NVMe PCIe 4.0 SSD, 2 TB |

| Containerization | Docker 24.0 with CUDA runtime |

| Training Time | ~14.7 h for 120 epochs |

| Parameter | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Learning Rate | 1 × 10−4 to 2 × 10−6 | Cosine annealing schedule with warm restarts |

| Optimizer | AdamW | β1 = 0.9, β2 = 0.999, weight decay = 0.01 |

| Batch Size | 8 (MRI), 16 (CT) | Balanced for memory and convergence stability |

| Epochs | 120 | Sufficient for convergence with multitask objective |

| Loss Weights | λ1 = 1.0, λ2 = 0.75, λ3 = 0.25 | Segmentation, functional, and structure–function consistency |

| Scheduler | Cosine Annealing | Warm-up for 5 epochs |

| Gradient Clipping | 5 | Prevents exploding gradients |

| Dropout Rate | 0.15 | Applied in functional head only |

| Mixed Precision | Enabled (FP16) | Improves training speed and reduces memory use |

| Metric | Cortex | Medulla | Pelvis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dice | 0.94 | 0.91 | 0.89 |

| IoU | 0.89 | 0.84 | 0.81 |

| HD95 (mm) | 9.8 | 12.1 | 14.4 |

| Model | Dice | HD95 (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| U-Net [23] | 0.88 | 15.2 |

| Attention U-Net [24] | 0.9 | 13.1 |

| TransUNet [25] | 0.91 | 12.5 |

| MS-Unet [26] | 0.92 | 11.3 |

| FG-CKD-UNet (Proposed) | 0.94 | 9.8 |

| Model | MAE | RMSE | R2 | Pearson r |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Encoder-only Regression [28] | 0.065 | 0.089 | 0.71 | 0.8 |

| ResNet Baseline [29] | 0.055 | 0.076 | 0.78 | 0.86 |

| CNN + MLP Baseline [30] | 0.048 | 0.067 | 0.82 | 0.87 |

| FG-CKD-UNet (Proposed) | 0.039 | 0.058 | 0.85 | 0.92 |

| Model | Consistency Error (CE) | |ŷ − ŷmorph| | Morphology Correlation (rmorph) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Without Consistency Loss | 0.071 | 0.065 | 0.78 |

| FG-CKD-UNet (With Consistency Loss) | 0.042 | 0.028 | 0.91 |

| Configuration | Dice | MAE | Consistency Error (CE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full FG-CKD-UNet (Proposed) | 0.94 | 0.039 | 0.042 |

| Without Consistency Loss | 0.92 | 0.048 | 0.071 |

| Without Biomarker Extractor | 0.91 | 0.051 | 0.066 |

| Single-Task Segmentation Only | 0.93 | — | — |

| Single-Task eGFR Prediction Only | — | 0.065 | — |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Al-Salman, O.; Cevik, M. A Functionally Guided U-Net for Chronic Kidney Disease Assessment: Joint Structural Segmentation and eGFR Prediction with a Structure–Function Consistency Loss. Electronics 2026, 15, 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010176

Al-Salman O, Cevik M. A Functionally Guided U-Net for Chronic Kidney Disease Assessment: Joint Structural Segmentation and eGFR Prediction with a Structure–Function Consistency Loss. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):176. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010176

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Salman, Omar, and Mesut Cevik. 2026. "A Functionally Guided U-Net for Chronic Kidney Disease Assessment: Joint Structural Segmentation and eGFR Prediction with a Structure–Function Consistency Loss" Electronics 15, no. 1: 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010176

APA StyleAl-Salman, O., & Cevik, M. (2026). A Functionally Guided U-Net for Chronic Kidney Disease Assessment: Joint Structural Segmentation and eGFR Prediction with a Structure–Function Consistency Loss. Electronics, 15(1), 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010176