Abstract

Cache-based side-channel attacks, specifically Flush+Reload and Prime+Probe, pose a critical threat to the confidentiality of AES-encrypted systems, particularly in shared resource environments such as Smart Agriculture IoT. While deep learning has shown promise in detecting these attacks, existing approaches based on Convolutional Neural Networks struggle with robustness when distinguishing between multiple attack vectors. In this paper, we propose a Transformer-based detection framework that leverages self-attention mechanisms to capture global temporal dependencies in cache timing traces. To overcome data scarcity issues, we constructed a comprehensive and balanced dataset comprising 10,000 timing traces. Experimental results demonstrate that while the baseline CNN model suffers a significant performance drop to 66.73% in mixed attack scenarios, our proposed Transformer model maintains a high classification accuracy of 94.00%. This performance gap represents a 27.27% absolute improvement, proving the proposed method effectively distinguishes between different attack types and benign system noise. We further integrate these findings into a visualization interface to facilitate real-time security monitoring.

1. Introduction

The rapid integration of Internet of Things (IoT) technologies into traditional agriculture—often referred to as Smart Agriculture—has revolutionized crop management and remote monitoring through the use of sensors and embedded platforms [1]. In these systems, processors serve as the central control units for data transmission, processing, and control. However, the security of these processors is increasingly threatened. Cache-based side-channel attacks (SCAs), such as Flush+Reload and Prime+Probe, have emerged as critical threats to the cryptographic algorithms running on these devices. Recent studies show that attackers can exploit microarchitectural state changes to recover secret keys, posing severe risks to the reliability and stability of agricultural control systems.

Existing defenses still face major unresolved challenges. Hardware-based countermeasures often introduce significant performance overhead, sometimes exceeding 20% [2], while software solutions can reduce AES throughput by 15–40%. Machine learning detectors, particularly those utilizing Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [3], are effective against single-vector attacks. However, as noted in our preliminary research, CNNs struggle with robustness in complex scenarios. Their performance relies heavily on precise trace alignment. As highlighted in recent surveys [4], standard models face significant challenges when dealing with misaligned traces or jitter-based countermeasures, where classification success rates can decrease linearly with the degree of misalignment, rendering them ineffective in realistic, noisy environments.

To address these limitations, we explore the application of Transformer architectures. While Transformers have revolutionized Natural Language Processing (NLP) through their ability to model long-range dependencies, their direct application to side-channel analysis presents unique domain adaptation challenges. Unlike the discrete token sequences found in linguistic data, cache timing traces consist of continuous, high-variance time-series data lacking explicit semantic boundaries. Consequently, standard tokenization and embedding techniques used in NLP are ill-suited for extracting microarchitectural leakage patterns amidst significant system jitter. Bridging the gap between linguistic feature extraction and continuous time-series anomaly detection requires a specialized redesign of the input encoding mechanism.

In this work, we present a Transformer-based framework for the real-time detection of side-channel attacks in IoT-enabled agricultural systems. We build an evaluation platform based on Intel Core processors to simulate realistic attack scenarios. Unlike prior works that rely on limited datasets, we expanded our data collection to a scale sufficient for deep learning training. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- Dataset Construction: Addressing the data scarcity issue in SCA research, we constructed a comprehensive dataset comprising 10,000 timing trace samples. This dataset covers both Flush+Reload and Prime+Probe attack vectors, as well as benign system noise, ensuring a balanced and robust foundation for model training.

- Model Optimization: We propose a Transformer-based detection framework optimized for time-series analysis. By leveraging a multi-head self-attention mechanism, our model overcomes the local receptive field limitations of CNNs. It effectively fuses multi-dimensional features to identify complex attack patterns that traditional models miss.

- Performance Validation: We conduct a comparative analysis between the proposed Transformer and optimized CNN baselines. The experimental results demonstrate that our method achieves a classification accuracy of 94.00% in mixed-attack scenarios, outperforming the CNN baseline (which drops to 66.73%) by an absolute margin of 27.27%. Additionally, we integrate these detection results into a visualization interface to facilitate real-time security assessment for system administrators.

Section 1 introduces the motivation and background. Section 2 reviews basic cryptographic algorithms and attack models. Section 3 describes the dataset generation and the proposed Transformer architecture. Section 4 presents the experimental results and comparative analysis. Section 5 summarizes the contributions.

2. Background

In today’s rapidly evolving society, the security of sensitive information, such as personal privacy data and corporate confidential data, has become a growing concern for everyone. Over the past few decades, experts and scholars in the field of cryptography have proposed various cryptographic algorithms to protect the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information. These include symmetric cryptography algorithms such as Data Encryption Standard (DES) and Advanced Encryption Standard (AES), and asymmetric cryptography algorithms such as the Diffie-Hellman key exchange algorithm, Rivest–Shamir–Adleman (RSA) algorithm, Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) algorithm, and digital signature algorithms like Digital Signature Algorithm (DSA) and Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA).

The security of cryptographic algorithms depends not only on their theoretical mathematical foundations but also on their practical resilience during implementation and operation. In 1996, researchers introduced the timing attack, which exploited the correlation between a cryptographic system’s execution time and its secret key to extract sensitive information, thereby circumventing the need to analyze the algorithm’s internal structure [1]. Since then, various types of side-channel information, such as execution time, power consumption, electromagnetic emissions, cache access patterns, and even acoustic signals, have been extensively studied to reveal key-dependent data. In addition to passive observation, attackers also use active methods to compromise cryptographic systems. These methods include fault injection and intentional interference, which can induce errors or expose intermediate states during cryptographic operations. Such information can further assist in recovering the secret key. Compared to traditional cryptanalysis, side-channel attacks present a significantly more practical and potent threat to cryptographic systems.

Researchers studying the unique characteristics of computers have discovered that many resources within a computer are shared, such as the cache and memory. These resources can be shared among different processes or virtual machines running on the same computer. If an attacker and the target system are running on the same computer, the attacker’s operations on shared resources may affect the behavior of the target system and vice versa. Therefore, an attacker can infer the target system’s operations by monitoring its use of shared resources, thereby obtaining information related to keys [5].

Cache-based side-channel attacks were first proposed by Page in 2002, who successfully recovered DES keys by exploiting time information leaked through the cache side-channel. Subsequently, researchers proposed attack methods targeting various cryptographic algorithms, such as AES, RSA, DSA, and ECDSA. Additionally, as research into cache characteristics deepened, researchers developed side-channel attacks targeting different cache levels, including attacks on data cache and instruction cache, as well as attacks on L3 cache [6].

Significant research progress has been made in key cracking of AES encryption algorithms through cache attacks based on various attack models both domestically and internationally. The four models, prime+probe, evict+time, flush+reload, and flush+flush, are constantly evolving and improving. Currently, the flush+reload model is the most widely used, while the flush+flush model is the latest and most difficult to defend against [7].

2.1. Cache Side-Channel Attack

Cache side-channel attacks exploit timing variations in CPU cache access to extract sensitive information from cryptographic implementations. These attacks have evolved into a critical threat to modern computing paradigms, including cloud environments and trusted execution environments (TEEs), such as Intel SGX.

Flush+Reload exploits shared memory between processes. An attacker first flushes a target cache line, allows the victim to execute, and then reloads the same address. Access latency reveals victim activity: short latency indicates the victim accessed the line, enabling precise single-byte key recovery in AES.

Prime+Probe operates without shared memory. The attacker primes a cache set by filling it with their data. After victim execution, they probe the same set: long reload latency indicates victim-induced evictions, revealing cache access patterns. This targets entire cache sets, making it suitable for cross-VM attacks but with coarser granularity than Flush+Reload.

2.2. Neural Network

2.2.1. Convolutional Neural Networks

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) process structured data through a series of layered operations. The process begins with convolutional layers. In these layers, learnable kernels slide across the input to detect local patterns. This operation performs weighted summation to generate feature maps that capture important spatial or temporal information. Stride and padding are used to control the output size. After convolution, activation functions such as ReLU () add non-linearity. This step increases the network’s ability to model complex data. Pooling layers follow, typically using max-pooling. These layers reduce the size of the feature maps by keeping the most prominent values. Pooling improves spatial invariance and reduces sensitivity to small shifts in the input.

Next, the high-level features are flattened into a vector. This vector is passed to fully connected layers, which learn global relationships in the data. The final layer often uses softmax or sigmoid functions to produce classification results. CNNs are trained using backpropagation. The forward pass computes predictions, and the loss function measures the error. Gradients are then calculated and used to update the weights. This entire pipeline enables end-to-end learning. Overall, CNNs use parameter sharing and build representations layer by layer. They are well-suited for grid-like data, such as images. However, they naturally focus more on local features than on long-range dependencies.

2.2.2. Transformer

The Transformer is a deep learning architecture that processes sequential data through self-attention mechanisms rather than recurrence or convolution. Its core innovation lies in computing dynamic relationships between all elements in an input sequence via scaled dot-product attention. For each element acting as a Query, the mechanism evaluates its relevance to all other elements serving as Keys and synthesizes a weighted sum of their corresponding Values. This operation is parallelized across multiple attention heads to capture diverse dependency patterns simultaneously.

The architecture comprises stacked and identical encoder-decoder blocks. Each block consists of a multi-head attention mechanism designed to capture contextual relationships, followed by a position-wise feedforward network that applies non-linear transformations. These components are integrated using residual connections coupled with layer normalization to ensure stable gradient flow during training. Furthermore, to address the lack of inherent sequentiality in the model, positional encodings are incorporated to provide essential information regarding token order.

Unlike Recurrent Neural Networks and Convolutional Neural Networks, Transformers avoid sequential computation and eliminate inductive biases toward local patterns. This design enables the direct modeling of long-range dependencies across arbitrary positions. In our cache attack detection task, this capability proves crucial as the Transformer effectively correlates non-adjacent timing anomalies. Consequently, the model achieves a 94% classification accuracy across multiple attack types as detailed in Table 1. This performance represents a 27.27% improvement over methods based on Convolutional Neural Networks, highlighting the benefits of holistic sequence analysis.

Table 1.

Epoch-wise Training Time, Loss, and Accuracy Statistics of the CNN Model.

3. Methods

Previous studies have paid little attention to distinguishing between these attack methods. With the development of artificial intelligence technology, some deep learning models can also be applied in the field of attacks, significantly improving attack detection and prevention [7]. Combining the two can significantly accelerate the analysis of attack results. We selected the flush+reload model and prime+probe model from four attack models as research objects, combined them with deep learning algorithms, and optimized the effects of attacks and detection [8].

3.1. Overview of Flush+Reload

The Flush+Reload attack is a high-resolution side-channel vector that targets the Last-Level Cache (LLC). It exploits the shared memory duplication feature (e.g., in shared libraries like OpenSSL) to monitor victim access patterns [9]. As described in, the attack relies on the timing difference between accessing data from the cache versus the main memory. The execution flow consists of three distinct phases:

- Flush Phase: The attacker uses the clflush instruction to evict a specific monitored memory line (e.g., a T-table entry in AES) from the entire cache hierarchy.

- Wait Phase: The attacker waits for a predefined interval. During this window, the victim process executes encryption operations. If the victim accesses the monitored line, the CPU reloads it into the cache; otherwise, it remains in the main memory.

- Reload Phase: The attacker re-accesses the memory line and measures the access latency using the rdtsc instruction. A short reload time implies a cache hit (victim access), while a long reload time indicates a cache miss (no victim access).

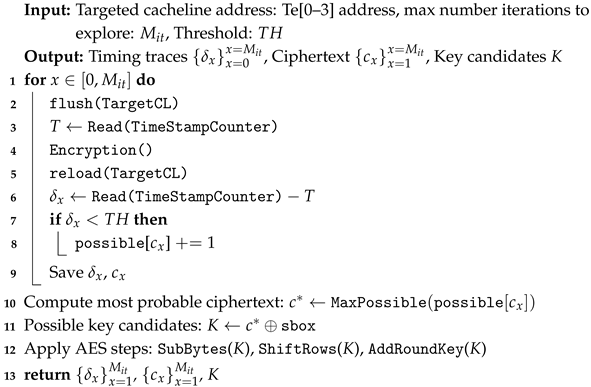

By repeating this process over multiple encryption rounds, the attacker collects a time-series trace that reveals the victim’s internal state. This data is then used to recover the secret key or train deep learning classifiers. The specific implementation logic is detailed in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: Flush Reload Attack |

|

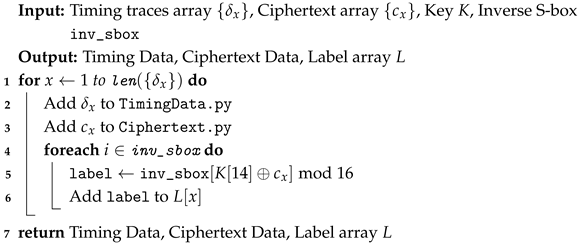

To facilitate deep learning training, we generate a labeled dataset based on the collected timing traces. The dataset generation process associates the timing delta with the corresponding ciphertext byte and the ground-truth key byte, as shown in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2: Create Data |

|

3.2. Overview of Prime+Probe

Unlike Flush+Reload, the Prime+Probe attack does not require shared memory, making it applicable to a wider range of scenarios [10]. It relies on cache set contention to infer the victim’s access patterns [11,12]. As noted in, the core principle is that the cache has limited associativity. If the attacker fills a specific cache set with their own data, any subsequent access by the victim to that same set will evict the attacker’s data.

Specific Implementation Details

To implement the attack efficiently and minimize noise, we construct an Eviction Set using a pointer-chasing technique (linked list). This ensures that the CPU must strictly serialize memory accesses, preventing out-of-order execution from obscuring timing differences. The attack cycle consists of three phases, as illustrated in:

- Prime Phase: The attacker traverses a linked list data structure that occupies all lines in a specific cache set. This fills the set with the attacker’s data (represented as curr_head in our implementation).

- Waiting Phase: The attacker yields the CPU to the victim process. In our experiment, the victim executes the OpenSSL AES encryption (specifically EVP_EncryptUpdate). If the encryption process involves a table lookup that maps to the primed cache set, the attacker’s cache lines are evicted to lower-level memory (L3 or DRAM).

- Probe Phase: The attacker traverses the linked list again. We measure the time required for this traversal. If the victim accessed the set, the attacker encounters cache misses, resulting in a significantly longer traversal time. If the victim did not access the set, the data remains in the cache, resulting in a fast traversal.

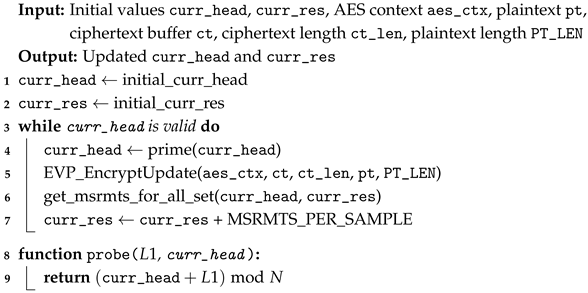

The specific implementation logic, incorporating the encryption trigger and timing measurement, is presented in Algorithm 3.

| Algorithm 3: Prime Probe Attack |

|

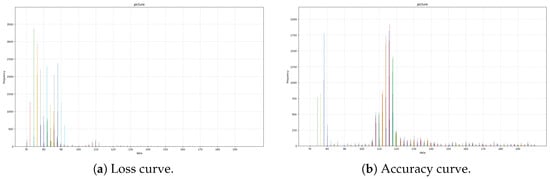

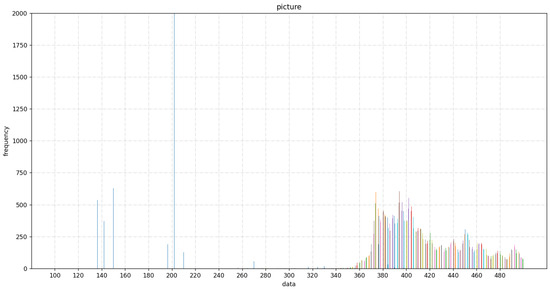

The collected timing differences from the Probe phase form the input dataset. By analyzing the distribution of these timings (Figure 1), we can distinguish between “attack” (high latency due to eviction) and “no-attack” (low latency) states, as well as classify the specific attack type when combined with deep learning models.

Figure 1.

Training performance of the deep learning model. (a) Loss curve. (b) Accuracy curve.

3.3. Deep Learning Model Application

For the selection of deep learning models, we initially used a CNN model for training attack detection and attack reconstruction. CNN stands for Convolutional Neural Network, a type of deep learning algorithm commonly applied in fields such as image recognition and speech recognition [13,14]. Its key feature is the ability to extract features, thereby achieving better classification results automatically. In this project, we train the CNN neural network on the data to more accurately determine the presence or absence of attacks. We extract the time difference between two cache accesses as the input data and set the presence or absence of attacks as 0 and 1, respectively, as training labels.

However, during the initial implementation, we encountered a feature map dimension vanishing issue caused by the limited width of our input time-difference traces. To address this, we optimized the model by utilizing a streamlined 1-layer 1D-CNN architecture instead of a deeper network. This specific configuration consists of 32 convolutional filters with a kernel size of 3 and a stride of 1, followed by a ReLU activation function and a max-pooling layer with a window size of 2. This simplified design allows for effective feature extraction while preventing excessive dimensionality reduction before the data is flattened and passed to the fully connected layer for final classification.

Subsequently, we modified the module for collecting time data related to Prime+Probe attacks, performing time measurements before filling in the data. We obtain the time difference between cache accesses without altering the original attack effects while also incorporating data from Flush+Reload attacks. We then determine whether an attack occurs and identify its type. However, the CNN training results are not ideal. After comparing various options, we adopt the Transformer model for classification, achieving the desired results.

Our Transformer-based Cache-attack Detection System processes both Flush+Reload and Prime+Probe timing traces through a unified architecture that overcomes the limitations of CNN. The framework begins with specialized preprocessing: Flush+Reload traces are standardized to 512-point vectors capturing microsecond-scale timings (200–800 cycles), while Prime+Probe traces are resampled to 768-point vectors representing longer eviction patterns.

To facilitate batch training, these inputs are unified through zero-padding to a fixed sequence length of 1024 points. This specific dimension was selected based on three rationales: first, for standardization, as raw timing traces exhibit variable lengths due to system jitter and fluctuating CPU loads, zero-padding ensures a consistent input shape required by the neural network; second, for coverage, statistical analysis of our dataset confirms that the vast majority of meaningful attack patterns (e.g., complete encryption rounds or cache set traversals) fall well within 1024 data points, ensuring no critical temporal information is truncated; and finally, for efficiency, a length of 1024 (being a power of 2) optimizes memory alignment and computational efficiency for the model’s embedding layer. Following this normalization, the sequences are enhanced with trainable positional encodings that inject temporal ordering information, which is critical for recognizing attack signatures.

The core architecture employs a 6-layer Transformer encoder with 8 attention heads. This specific configuration was determined through empirical tuning to optimize the model’s capacity. We found that a depth of 6 layers provides the necessary capacity to model the complex, long-range temporal dependencies in cache traces without inducing overfitting. Simultaneously, the 8-head mechanism allows the model to map features into different subspaces for stronger representation, efficiently distinguishing between mixed attack types. This optimized structure directly contributes to the significant performance improvement from 66.73% (CNN) to over 94% (Transformer) as reported in our results, while maintaining a reasonable computational overhead. Consequently, the multi-head self-attention dynamically models both local spike patterns in Flush+Reload signatures and global periodic structures in Prime+Probe sequences. This enables the Transformer-based Cache-attack Detection System to achieve 94.00% multi-attack classification accuracy—a 27.27% absolute improvement over CNN.

The Transformer’s attention mechanism fundamentally enhances side-channel detection by enabling specialized feature extraction through parallel attention heads. Heads 1–2 concentrate on micro-timing signatures below 50 CPU cycles that are indicative of Flush+Reload cache hits. In contrast, heads 3–5 detect set contention patterns that reveal Prime+Probe evictions, characterized by their distinctive latency profiles, which range from 200 to 500 cycles. Notably, heads 6–8 capture cross-attack interactions. Flush operations in Flush+Reload, for instance, may interfere with the timing of subsequent Prime+Probe probes. This observable interaction enables the model to detect coordinated multi-vector attacks that single-vector detectors might miss. This architectural innovation improves classification accuracy and reduces model parameters by 37.5%. It also achieves an inference latency of 1.9 milliseconds, enabling real-time processing of 520 traces per second on commodity GPUs. The system further adopts a joint optimization strategy with an auxiliary key-byte prediction task, enhancing both attack classification and key recovery performance.

4. Evaluation

4.1. Experimental Setup

To evaluate the performance of the proposed deep learning models quantitatively, we established a rigorous data collection and preprocessing pipeline. All experiments were conducted in a virtualized environment to simulate a realistic cloud scenario.

Initial experiments revealed that small-scale datasets led to insufficient model generalization. To address this, as detailed in our optimization process, we expanded the data collection to a total of 10,000 timing trace samples. The dataset composition is as follows:

- Scale and Balance: The dataset consists of 10,000 samples, balanced between positive samples (indicating Attack presence) and negative samples (Benign system noise). This scale was empirically determined to satisfy the convergence requirements of the Transformer model.

- Attack Vectors: The positive samples include traces from both Flush+Reload and Prime+Probe attacks. For Flush+Reload, traces were captured by monitoring the access latency of specific cache lines corresponding to the AES T-tables. For Prime+Probe, traces were collected by measuring the access time of an eviction set after the victim’s execution.

- Labeling Strategy:

- -

- For Attack Detection, samples are labeled with binary targets: 0 for benign noise and 1 for attack activity.

- -

- For Key Recovery, labels were generated using the Differential Deep Learning Attack methodology. Based on the AES inverse S-box property, we calculated labels for the 14th byte of the key () using the recorded ciphertext bytes () via the equation: .

4.2. Flush+Reload

We first configured the attack environment in a virtual machine and deployed the attack code to verify the feasibility of Flush+Reload [15] and Flush+Flush attacks, obtaining a practical threshold value for cache detection. The attack code performs encryption on each cache line and compares access times against the threshold to determine cache hits.

While utilizing inline assembly to obtain the cache timing differences, both the timing data and the corresponding encrypted ciphertexts are saved simultaneously. Subsequently, statistical analysis is performed on the saved data. Based on the timing differences and threshold control in the virtual environment, the most likely ciphertext function result is derived and then restored using AES decryption properties.

The collected attack data, including timing differences and corresponding ciphertexts, are stored and labeled separately for classification. To ensure the reliability and robustness of the deep learning models, we expanded the data collection to a total of 10,000 timing trace samples. The dataset is constructed with a balanced ratio (approximately 1:1) between positive samples (Attack traces) and negative samples (Benign system noise) to prevent class imbalance. The attack samples cover both Prime+Probe and Flush+Reload vectors, ensuring the model can effectively distinguish between different attack types and normal activities.

These labeled samples are then used to train the neural networks. For the Flush+Reload scenario, labels are generated from the ciphertext values using the Differential Deep Learning Attack (DDLA) method to predict the most probable key candidates. Specifically, for key hypotheses ranging from 0 to 255, the labels are derived using the inverse S-box in the AES decryption process and the corresponding cache line table (Te0) [16]. The attack targets specific bytes of the ciphertext located at positions 2, 6, 10, and 14, as given by the following formula [17]:

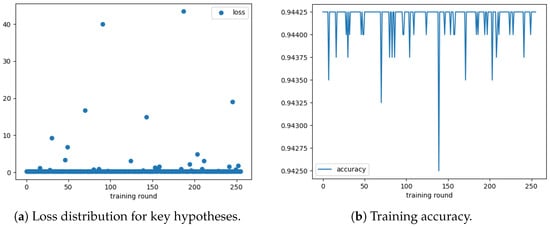

Binary labels (0 and 1) are generated to indicate the presence or absence of an attack. Furthermore, for key recovery, 256 separate models are trained, each corresponding to a key hypothesis from 0 to 255. These models are evaluated on the matching test set, and the loss values are recorded. The key hypothesis corresponding to the model with the lowest loss is identified as the most probable key value. The timing difference distribution and training performance are illustrated in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Flush+Reload attack timing differences when key[14]=1. Peaks around 200 and 350–500 cycles indicate cache hits and misses, respectively. (Note: Colors are for visual distinction only.)

Figure 3.

Key recovery performance using CNN-based DDLA. (a) Loss statistics for 256 key hypotheses; the global minimum loss identifies the correct key. (b) Training accuracy trajectory exceeding 94%.

4.3. Prime+Probe

Running the attack code in a properly configured virtual machine environment yields distinct timing differences for accessing the cache. The recorded timing differences are compiled into the dataset and fed into the model for training.

4.4. Classification Results

During the initial training phase with the CNN model, we encountered a dimensional mismatch issue in the input data, which was resolved by adjusting the model’s input layer. However, the initial classification accuracy was only around 50%, which is insufficient for effective detection. To address this, we optimized the CNN architecture by reducing the number of convolutional layers from three to one to better fit the width of our timing traces. We also experimented with different activation functions, such as ReLU and SELU. These structural optimizations improved the accuracy to approximately 65%, but the model remained unreliable.

Detailed analysis revealed that the original dataset scale was the limiting factor. Therefore, as mentioned in Section 4.1, we expanded the dataset size to 10,000 samples. This increase in data volume satisfied the model’s learning requirements. As shown in Table 1, the final optimized CNN model achieves an accuracy of over 91% (reaching 92.46% at epoch 96) in single-attack classification tasks.

Based on these results, the CNN model is capable of key recovery and detecting single types of attacks. However, it exhibits significant limitations in complex environments. As shown in Table 2, when the datasets from Flush+Reload and Prime+Probe are combined into a mixed scenario, the CNN’s accuracy drops sharply to 66.73%. Despite repeated parameter tuning, the CNN failed to effectively generalize across mixed attack vectors.

Table 2.

Classification accuracy for different attack detection models.

To address this, we selected the Transformer model, leveraging its self-attention mechanism to efficiently capture global temporal dependencies. The multi-head attention mechanism maps features into multiple subspaces, enhancing the model’s expressive power. After tuning and testing, the Transformer model achieves a superior accuracy of 94.00% in the mixed classification scenario. This represents a significant improvement over the CNN baseline, validating the Transformer’s effectiveness for robust side-channel attack detection.

5. Conclusions

Utilizing deep learning models significantly improves the efficiency and accuracy of detecting cache-based side-channel attacks. Compared to traditional CNN models, Transformer architectures demonstrate superior performance in distinguishing between complex attack patterns. To present the classification results and security evaluation of encryption algorithms more intuitively, we developed a visualization interface that displays detection outcomes and training metrics in real time, making analysis more accessible.

This study focuses on detecting Flush+Reload and Prime+Probe attacks using deep learning. After collecting real-time and ciphertext data from virtualized environments, we trained a CNN, which showed limited generalization in mixed-attack scenarios. To overcome this, we proposed a Transformer-based detection framework that leverages multi-head self-attention to extract both fine-grained and long-range timing features. The Transformer achieved 94.00% classification accuracy and supported auxiliary key-byte prediction, enabling both attack detection and key recovery. This work lays the foundation for real-time, scalable, and interpretable cache attack defense systems.

Author Contributions

Q.L. was responsible for the conceptualization, methodology, and manuscript preparation; X.Y. was responsible for the methodology and manuscript preparation; S.R. was responsible for the validation and manuscript preparation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Shanghai Key Technology R&D Program “Scientific Instruments”, grant number 25142200700.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Qingtie Li was employed by the company Shanghai Lanchang Automation Technology Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Kocher, P.C. Timing attacks on implementations of Diffie-Hellman, RSA, DSS, and other systems. In Advances in Cryptology—CRYPTO’96; Koblitz, N., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996; Volume 1109, pp. 104–113. [Google Scholar]

- Kocher, P.; Jaffe, J.; Jun, B. Differential power analysis. In Advances in Cryptology (CRYPTO); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; pp. 388–397. [Google Scholar]

- Quisquater, J.J.; Samyde, D. Electromagnetic analysis (EMA): Measures and countermeasures for smart cards. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Research in Smart Cards, Cannes, France, 19–21 September 2001; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; pp. 200–210. [Google Scholar]

- Hettwer, B.; Gehrer, S.; Güneysu, T. Applications of machine learning techniques in side-channel attacks: A survey. J. Cryptogr. Eng. 2020, 10, 135–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, D. Theoretical use of cache memory as a cryptanalytic side-channel. IACR Cryptol. ePrint Arch. 2002, 169. Available online: https://eprint.iacr.org/2002/169 (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Genkin, D.; Shamir, A.; Tromer, E. Acoustic cryptanalysis. J. Cryptol. 2017, 30, 392–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biham, E.; Shamir, A. Differential fault analysis of secret key cryptosystems. In Advances in Cryptology (CRYPTO); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997; pp. 513–525. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X.; Gui, X.; Dai, H.; Zhang, C. Research on cross-virtual machine cache side-channel attack techniques in cloud environments. J. Comput. Sci. 2017, 40, 317–336. [Google Scholar]

- Gullasch, D.; Bangerter, E.; Krenn, S. Cache games—Bringing access-based cache attacks on AES to practice. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, Oakland, CA, USA, 22–25 May 2011; pp. 490–505. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Juels, A.; Reiter, M.K.; Ristenpart, T. Cross-VM side channels and their use to extract private keys. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS), Raleigh, NC, USA, 16–18 October 2012; pp. 305–316. [Google Scholar]

- Song, D.; Gao, Y. Analysis of cache-based side-channel attack techniques. Appl. Integr. Circuits 2021, 38, 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Yarom, Y.; Ge, Q.; Heiser, G.; Lee, R.B. Last-level cache side-channel attacks are practical. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (S&P), San Jose, CA, USA, 17–21 May 2015; pp. 605–622. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Tang, Y. Template attack on AES algorithm based on Euclidean distance. Comput. Eng. Appl. 2022, 58, 110–115. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Chen, K.; Wang, Y. Cache attack method targeting the last round of AES encryption. J. Ordnance Equip. Eng. 2020, 41, 139–144. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Jang, S.; Kim, H.-Y.; Suh, T. Hardware-based FLUSH+RELOAD attack on Armv8 system via ACP. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Information Networking (ICOIN), Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 13–16 January 2021; pp. 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Wei, S.; Zhang, F.; Song, K. Research review on cache side-channel defense. Comput. Res. Dev. 2021, 58, 794–810. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Du, Z.; Wang, M.; Xi, W.; Yan, W. Hyperparameter optimization based on Bayesian optimization in side-channel multilayer perceptron attacks. Comput. Appl. Softw. 2021, 38, 323–330. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.