4.1. Node Responsibility Value Estimation Based on Load Imbalance

Aiming at the problem of load imbalance, a network node responsibility value estimation algorithm is proposed. The algorithm introduces a static influence factor and a load influence factor to comprehensively estimate the responsibility value of the node with respect to the entire network.

Assuming that the static factors are

and

,

represents the static impact factor corresponding to the normalized network efficiency,

represents the static impact factor corresponding to the normalized degree centrality, and

is the load impact factor. The relationship between the three is

. The node responsibility value based on load imbalance can be expressed as follows:

where

is the node responsibility value based on the comprehensive estimation of load imbalance and static network node properties.

represents the variable service application processing load quota borne by the No.

node, and it can be observed that

represents the variable service application processing load quota borne by the No.

node. To reasonably reallocate the service application processing load quota, a load change step can be set after the initial calculation, thereby further rationalizing the load distribution. The value of the step depends on the urgency of network load allocations and computational costs. A smaller change step should be set to achieve better convergence effects, while a larger change step should be set to ensure timeliness. Ultimately, the responsibilities of each node in the network tend to be consistent, and heterogeneity is reduced.

Using Formulas (1) and (2), (7) can be written as follows:

According to Formula (8), the responsibility value of network nodes in

Figure 4 is calculated. After sorting the data,

Table 1 can be rewritten into

Table 2. Before calculation,

is set to 0.3,

is set to 0.3, and

is set to 0.4.

These three types of influence factors are defined based on different service priorities and different network topology architectures. If the service priority of the current calculation is higher, the value of is increased, the values of and are decreased, and the estimated result of the responsibility value is more affected by load changes. If the network structure of the current calculation is more complex and the network topology sensitivity is higher, the values of and are correspondingly increased, and the value of is decreased such that the estimated result of the responsibility value is less affected by load changes. In practical applications, the factor can be dynamically adjusted according to different network topologies and service load requirements.

The calculation data of several node responsibility value evaluation methods in the chart are plotted (

Figure 5).

It can be observed in

Figure 5 and

Table 2 that the node responsibility value evaluation algorithm based on load imbalance is more comprehensive than other evaluation methods, and it can more comprehensively quantify the responsibility shared by nodes for dynamic networks.

By setting the load change step, each can be changed so that the responsibility value of each node tends to be consistent, which will make each node equally important to the network. From the perspective of network security, this result makes it more difficult for attackers to choose their target of attack, and filtering out high-value target nodes for attacks will not be easy. At the same time, load balancing also introduces another benefit: this approach maintains the loss of each satellite in the network as consistently as possible, preventing excessive loss caused by prolonged overloading on several satellites.

In the next section, a broken-link model that more closely reflects practical engineering applications is presented.

4.2. Analysis of Node Responsibility Value Under the Broken-Link Model

In the satellite constellation network based on inter-satellite links, link interruption is a significant problem affecting network connectivity and service continuity. As shown in

Figure 6, according to the relative orbit relationship of satellites, interruptions can be divided into two categories—inter-satellite link interruptions on the same orbit and inter-satellite link interruptions on different orbits—and their scenarios, causes, and effects are significantly different.

An inter-satellite link outage refers to the failure of a connection between adjacent satellites in the same orbital plane. These links are usually established permanently or semi-permanently, forming a “backbone chain” in the orbital plane. The primary causes of same-orbit inter-satellite link interruptions include physical damage or performance degradation of the transmitting or receiving modules and control units of the space-borne laser communication or radio frequency terminals, which can lead to permanent interruption of the link or anomalies in the satellite attitude control system, preventing the antenna or optical telescope from accurately targeting the adjacent satellite and resulting in loss of link lock. It is also possible that strong space radiation events may result in a single-event effect or instantaneous electronic equipment failure, causing link interruptions.

Inter-satellite link interruption refers to the failure of the connection between satellites located on different orbital planes. In specific space regions, such as polar regions, the establishment, maintenance, and dismantling of inter-satellite links are dynamic processes due to the intense relative motion of satellites, and interruptions occur frequently in this process.

The loss of interstellar visibility is the most fundamental reason for the interruption of inter-satellite links. Due to the high-speed operation of satellites in their respective orbits, the inter-satellite line of sight can be interrupted by Earth’s occlusion. In particular, in the polar regions, the relative velocity of satellites on different orbital surfaces is extremely high, and the visual time window is extremely short and changes rapidly. Other causes of inter-satellite link interruptions may include drastic changes in the relative position and velocity vectors between satellites, exceeding the acquisition, tracking, and pointing technical indicators of the links; link-switching failures; or intentional strategic shutdowns of the system. To save on-board energy, the network may strategically and temporarily close some non-critical inter-satellite links.

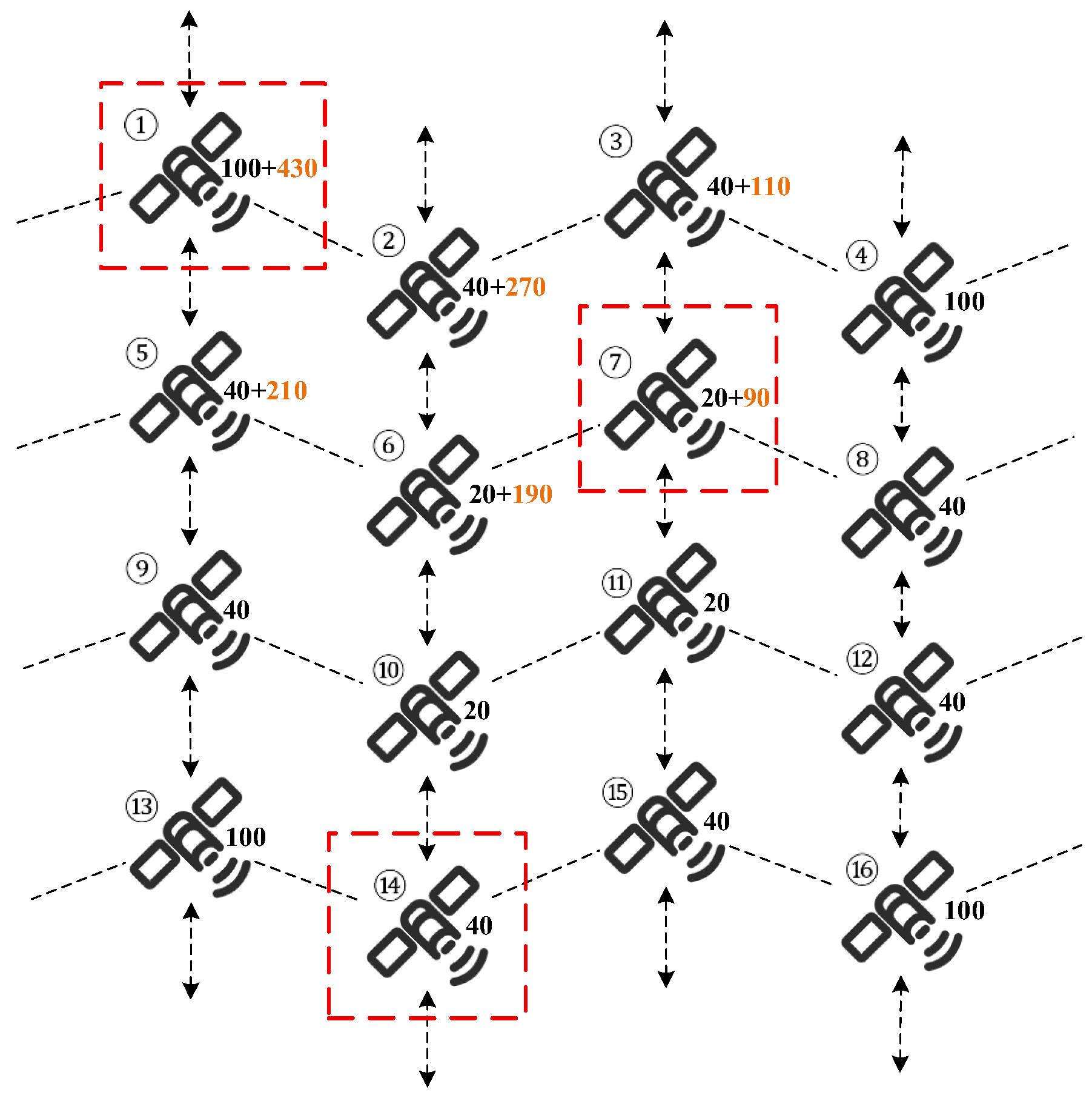

The satellite nodes in

Figure 6 are simplified and edited, and the initial load of each satellite node is given according to the load distribution law (

Figure 7).

Link outages (especially critical out-of-orbit or co-orbit links) cause the betweenness centrality of nodes to undergo a significant transition after the link is broken. Edge nodes with lighter load may become important bottleneck nodes because they become the only bridge connecting two separate network areas. For network connectivity, local congestion nodes may appear in the network, and their cache queues quickly saturate.

Considering practical engineering situations, multiple real-time services may operate simultaneously within the same time period. Under the constraint of the coexistence of multiple real-time services, the initial load distribution of nodes undergoes severe and non-uniform reconstruction. Under this condition, it is more necessary to combine static and dynamic network node attributes to comprehensively consider the responsibility value of satellite network nodes.

In this study, two real-time services are introduced in the broken-link scenario, as shown in

Figure 8. When service A is online, it includes nodes No. 3, No. 4, No. 7, and No. 8 within the load application range. When service B is online, it includes nodes No. 5, No. 6, No. 9, No. 10, No. 11, No. 13, No. 14, and No. 15 within the load application range.

If the general node in the network is transformed into a major relay and overloaded, it can turn into a performance bottleneck and a system vulnerability. Its overload not only results in local service failure but also poses a threat to the global stability and fairness of the network. At the same time, this results in serious differentiations in service quality. Under the differentiated service mechanism, the node scheduler assigns priority to guaranteeing high-priority services. This enables the critical task data flow to be maintained, and a large number of low-priority business traffic suffer serious service degradation and even interruptions. If a general node is transformed into an edge relay and bears a low load, it can be considered to be in a robust state, similar to a silent state. Although its performance does not deteriorate, the idleness of its resources results in a significant opportunity cost and wasted overall capacity.

Although load allocation is an important component of estimating the responsibility value of nodes, it is necessary not only to consider the load factor but also to dynamically adjust the change in load quota in combination with other attributes of the network nodes. Using the results of the node responsibility value evaluation algorithm that integrates multiple factors, the load distribution is further optimized to achieve relative balance.

Using the three responsibility calculation methods and the node responsibility algorithm based on the load imbalance proposed in this study, the network node responsibility values under the model are calculated. The results are shown in

Table 3. For the responsibility value algorithm proposed in this study, before calculations,

was set to 0.3,

was set to 0.3, and

was set to 0.4. In practical applications, due to various factors—such as different network topologies and service business priorities—these three impact factors can be dynamically adjusted in real time to ensure the accuracy and real-time performance of node responsibility calculations.

As shown in

Table 3, the normalized degree centrality calculation results show that the estimated values of multiple nodes are consistent. If decisions are based solely on this data, it becomes difficult to accurately adjust node attributes and further optimize the network. This method only measures the number of a node’s direct connections and completely ignores the position of nodes in the global topology of the network, while the term N − 1 in the formula represents the maximum possible number of connections. In large, sparse networks, even if the node has the highest degree centrality, its normalized value may be very small, which can easily cause misunderstanding in that not all nodes are important. In reality, such nodes still play a crucial role at the local or global level.

For the normalized network efficiency estimation method, although the nodes can be further optimized using the calculated values, the data index calculated by the method is based on the shortest path on the topology rather than the actual load, resulting in calculated values that are too one-sided. Moreover, this estimation method oversimplifies the true state of the disconnected network. The normalization efficiency of a network with a small number of disconnected nodes may drop sharply to near zero, but this substantially exaggerates the degree of failure of the network because it completely ignores the normal communication capabilities within most connected components that still exist in the network. This index fails to distinguish between local isolation and global collapse.

In practical applications, for most networks, there are key node pairs (such as between data centers and between command centers and sensors) and non-key node pairs. The decrease in normalized network efficiency may be due to the disconnection of non-key nodes, while the significant communication path is still intact. This index cannot reflect the difference between business priority and performance requirements, which may result in a serious disconnection between the evaluation conclusion and the real business experience.

The node responsibility value calculated by the load distribution ratio method can accurately indicate the load difference between nodes, but this method assumes that all nodes have homogeneous resources and processing capabilities. For example, the No. 7 node is unimportant in the estimation result of the load distribution ratio method, yet it serves as a core forwarding relay in the network.

The algorithm proposed in this study comprehensively considers the influence of nodes on the connectivity of the entire satellite network. Combined with the load distribution, the calculated node responsibility value is more accurate and can more effectively reflect the influence of the node in the network.

As observed in

Figure 9, the difference between the maximum and minimum values of the node responsibility values obtained using the estimation method proposed in this study is only 0.11129, and the difference between the maximum and minimum values of the node responsibility values obtained using the other three methods is 0.14052. By only relying on the three methods—normalized point degree centrality, normalized network efficiency, and load rate—to estimate the node responsibility value, the node responsibility value varies greatly, and data reliability is low. The use of unreliable data can lead to misjudging the heterogeneity of network nodes as being excessively high. An unreasonable routing planning decision made on this basis affects the stability of network performance. The security strategy based on this data is also unreliable, which introduces risks to network security.

The sensitivity of the algorithm’s estimation results to variations in parameters , and is further discussed in this study. Quantitative analyses were conducted under three conditions: network efficiency priority, degree centrality priority, and service load priority. Specifically, when network efficiency was prioritized, parameter was set to 0.6, while parameters and were both set to 0.2. When degree centrality was prioritized, parameter was assigned a value of 0.6, with parameters and each set to 0.2. When service load was given top priority, parameter was fixed at 0.6, and parameters and were both set to 0.2. The control variable method was adopted to ensure the reliability of the sensitivity tests.

Node No. 1, node No. 7 and node No. 14 were selected as the research objects. The responsibility value estimation results under the three aforementioned scenarios were compared with those obtained when the three types of parameters were assigned equal values, as shown in

Table 4.

For node No. 1, when network efficiency is given top priority (, ), its estimated value decreases significantly. The main reason is that node No. 1 inherently has low network connectivity to the entire network, and its degree centrality and load factors are relatively important factors affecting its responsibility value. When degree centrality is given top priority (, ), its estimated value increases substantially, indicating that node No. 1 has high positive sensitivity to degree centrality. For node No. 7, when network efficiency is prioritized (, ) and when service load is prioritized (, ), its estimated values exhibit the same trend of change with comparable magnitudes of variation. It can be observed that the responsibility value of node No. 7 shows a positive sensitivity to degree centrality, while its sensitivities to network efficiency and service load are nearly identical. Compared with node No. 1 and node No. 7, node No. 14 exhibits smaller magnitudes of variation in its responsibility value estimation results under the three aforementioned scenarios. It can thus be concluded that for any network, different nodes demonstrate heterogeneous sensitivities to these three types of parameters, which depend on the functional role types that the nodes undertake in the network.

For large-scale networks, due to their more complex network topology and a greater number of network nodes, some nodes in the network exhibit higher sensitivity to network efficiency. Moreover, the larger the network scale, the more diverse the service requirements, which leads some nodes to become high-hotspot and high-load nodes—implying that these nodes have stronger sensitivity to service load. Since the estimation results of the algorithm proposed in this paper are affected by heterogeneous sensitivity impacts based on the different functional roles that nodes undertake in the network, this characteristic becomes more prominent in large-scale network scenarios. In the future, the algorithm can be further extended and applied in large-scale network environments to conduct further evaluation and optimization.

Meanwhile, in large-scale network scenarios, to achieve accurate evaluation of the responsibility value of each node using the algorithm proposed in this paper, further exploration still needs to be carried out around the following four directions: first, computational complexity control. It is necessary to reduce the algorithm complexity to a level compatible with the real-time requirements of large-scale networks by means of distributed architectures, lightweight models, or incremental computing strategies. Second, dynamic topology adaptability. A dynamic update mechanism based on topology change perception should be established to avoid evaluation accuracy deviations caused by link switching, node access, or node departure. Third, service-driven indicator weight optimization. It is required to dynamically adjust the weight allocation of evaluation indicators, such as network connectivity and load, in response to heterogeneous service requirements. Fourth, resource constraint compatibility. The algorithm design must be adapted to resource-constrained scenarios, such as on-board satellite nodes. By simplifying the computing logic and optimizing storage overhead, overloading of computing power and energy can be prevented.

The energy-saving strategy can also be continuously optimized according to the estimated accurate node responsibility value. In the light-load period, low-importance nodes can be preferentially placed in sleep or low-power mode, while ensuring that high-importance nodes are always in a ready state to achieve the best balance between energy efficiency and network readiness. In this process, according to the node responsibility value calculated using the algorithm proposed in this study, the load borne by the network nodes is further reasonably allocated such that the task load and loss borne by each satellite node in the network are more consistent.

From the perspective of network security reliability, active defense can be implemented according to accurate and effective node responsibility values to identify and reinforce vulnerable nodes. It can also further achieve resilient routing and rapid self-healing. Before the failure of high-importance nodes, the network can calculate and activate alternate routes in advance to achieve the rapid and smooth migration of services.

The algorithm proposed in this study was experimentally validated under a 4 × 4 network architecture. Its accuracy and performance in larger-scale satellite network architectures still require verification. Currently foreseeable potential research issues include the following: Repeated shortest-path calculations incur high computational costs, and collecting local or global load variations results in substantial delays. In the future, this algorithm can be combined with software-defined networking (SDN) and deep learning to conduct further research, using dynamic network parameters such as network throughput, network latency, and packet loss rate as indicators. This method can be used to estimate local network node responsibility values in a distributed manner while performing centralized estimations of the entire network state at the control layer. The combination of these two approaches can avoid local optima. In the future, further testing can be conducted in large-scale satellite networks (comprising thousands or even tens of thousands of nodes) to further verify the effectiveness and reliability of the algorithm.

A currently popular development direction is to use low-orbit satellite constellations as relay networks to serve low-altitude platforms and other space vehicles in multi-layer space information networks [

27,

28,

29]. In this context, due to the increasing variety of services, node responsibility value estimation based on load imbalance has become more critical, especially for satellite nodes that serve as important gateways [

30,

31]. In the future, the algorithm proposed here can be improved for applications in this scenario.

Inter-orbit optical inter-satellite links (ISLs) are one of the core technologies enabling low Earth orbit satellite constellations to achieve global seamless coverage and high-speed data interconnection [

32]. Due to constraints related to relative motion, pointing, acquisition, and tracking, inter-satellite links in different orbits face greater challenges than inter-satellite links in the same orbit. Future discussions can explore the applicability and performance of the algorithm proposed in this study in such scenarios.