Abstract

Object detection in adverse weather remains challenging due to the simultaneous degradation of visibility, structural boundaries, and semantic consistency. Existing restoration-driven or multi-branch detection approaches often fail to recover task-relevant features or introduce substantial computational overhead. To address this problem, DLC-SSD, a lightweight degradation-aware framework for detecting robust objects in adverse weather environments, is proposed. The framework integrates image enhancement and feature refinement into a single detection pipeline and adopts a hierarchical strategy in which global and local degradations are corrected at the image level, structural cues are reinforced in shallow high-resolution features, and semantic representations are refined in deep layers to suppress weather-induced noise. These components are jointly optimized end-to-end with the single-shot multibox detection (SSD) backbone. In rain, fog, and low-light conditions, DLC-SSD demonstrated more stable performance than conventional detectors and maintained a quasi-real-time inference speed, confirming its practicality in intelligent monitoring and autonomous driving environments.

1. Introduction

With the growing demand for intelligent urban management, video surveillance has become a key tool in monitoring road conditions, ensuring traffic safety, and supporting incident response [1]. Object detection plays a key role in such a real-world system; however, maintaining stable performance under adverse weather conditions, such as rain, fog, low illumination, and night shooting, is challenging because the image quality is severely degraded. Under these conditions, blurring, contrast reduction, particulate noise, and structural distortion caused by scattering occur at the same time, blurring the appearance information of the object and blurring the boundary with the background [2,3]. In particular, since high accuracy, real-time processing power, and lightweight are essential in the actual deployment environment, existing heavy restoration networks or high-cost detection models have practical limitations.

Various approaches have been proposed to address the problem of adverse weather object detection, but fundamental limitations remain. Image restoration-based methods often focus on improving human visual quality, so they cannot sufficiently restore structural and semantic clues required by object detectors [4,5,6]. Recent studies in other imaging domains have also shown that visually pleasing restoration or reconstruction does not necessarily lead to improved task performance, underscoring the importance of task-driven enhancement strategies tailored to downstream detection objectives [7,8]. On the other hand, adding a separate auxiliary decoder or a multi-branch inside the detector is challenging for real-time performance due to increased parameter count and computational cost. In addition, deep CNN-based detectors lose high-frequency information such as boundary and texture during the repetitive downsampling process, and this structural loss is further intensified in adverse weather conditions, making them vulnerable to small objects or objects with blurred boundaries [9,10,11,12,13].

To overcome these limitations, this study proposes a lightweight, unified refinement pipeline that corrects the image-level, structural, and semantic-level degradation in a step-wise manner. The first step minimizes global and low-frequency degradation of the input image at minimum cost; the second step strengthens the boundary cues in shallow, high-resolution features; and the last step performs global context-based semantic alignment in deep features. These three processes do not operate independently of each other. However, they are designed in a complementary manner around detection performance, which simultaneously improves the robustness and expressiveness of single-shot multibox detector (SSD)-based object detectors [14,15]. In the proposed framework, these three stages are instantiated by a task-driven Differentiable Image Processing (DIP) module for image-level enhancement, a Lightweight Edge-Guided Attention (LEGA) mechanism for structural reinforcement, and a Content-aware Spatial Transformer with Gating (CSTG) for semantic refinement.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- A lightweight hierarchical refinement pipeline is proposed for adverse weather object detection, which jointly addresses image-level, structural, and semantic degradations within a single SSD-based detection framework.

- The refinement stages are designed as complementary components under strict efficiency constraints: the first stage performs low-cost image-level enhancement, the second stage reinforces structural cues in shallow high-resolution features, and the third stage refines deep semantic representations with global contextual reasoning.

- A comprehensive experimental study is conducted on rain, fog, and low-light conditions, including comparisons with restoration-driven and high-cost detection baselines as well as ablation studies on the proposed components. These demonstrate that the unified pipeline achieves robust performance while maintaining near real-time efficiency.

2. Related Work

2.1. Adverse Weather Object Detection

Object detection in adverse weather environments has been extensively studied through various structural variations. Networks with two-pronged or multi-branch structures, such as DSNet and D-YOLO, aim to enhance robustness by incorporating recovery subnetworks or by fusing blurred and sharp features [11,12]. AK-Net decomposes weather degradation with multiple sub-degradation factors such as rain, fog, and water droplets to improve the performance of small-object detection in complex environments [13]. Transformer-based techniques, including WRRT-DETR, leverage multi-head self-attention to enhance long-range contextual modeling and semantic discrimination capabilities [16,17]. On the other hand, some techniques, such as ClearSight, adopt a preprocessing-oriented strategy, applying a deep enhancement module and then inputting images into the detector [18]. Representative approaches and their properties are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Representative methods for object detection under adverse weather conditions.

Despite meaningful progress, these approaches have common limitations. Restoration–detection hybrid structures typically require heavy components such as decoders, auxiliary subnetworks, and multipath branches, which significantly increase the number of parameters and computational cost. Models specific to a particular type of degradation generalize poorly to other conditions, and Transformer-based designs incur high memory usage and slow inference speeds, making real-time applications challenging. Preprocessing-based enhancement techniques also exhibit weak task alignment with real-world detection objectives, as the enhancement phase is optimized independently of the detection objectives.

2.2. Differentiable Image Processing and Task-Driven Enhancement

Image-level enhancement has been actively studied to mitigate visibility degradation caused by factors such as rain, fog, and low illumination. Techniques such as ZeroDCE focus on correcting illuminance imbalances and contrast degradation without the need for paired supervised data, demonstrating clear improvements in visual quality [6]. However, since these enhancement-only designs operate independently of detection tasks, they show limitations in providing performance improvements in complex adverse weather environments. Detector-based enhancement techniques such as IA-YOLO, GDIP, and ERUP-YOLO incorporate enhancement modules into the detection backbone, but in many cases depend on decoder-type structures or parameter-rich filtering operations to reduce real-time efficiency [19,20,21]. Furthermore, augmentation-centered approaches also reveal that image-level correction alone does not consistently translate into improvements on detection metrics under real adverse weather conditions [22]. Moreover, pixel-level enhancements alone do not sufficiently restore the structural cues or semantic consistency required for stable detection. Representative enhancement-based techniques and their limitations are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Representative methods based on Differentiable Image Processing and task-driven enhancement.

Task-driven enhancements remain an unsolved problem because existing techniques either operate separately from detection pipelines or incur significant computational costs. The DIP module design proposed in this study resolves this gap by introducing a fully differentiable structure and a lightweight filter-parameter prediction mechanism based on a small CNN. Multi-filter combinations involving noise cancellation, sharpening, and pixel-wise correction are implemented as differentiable operations without relying on high-resolution reconstruction networks. This allows the enhancement process to be co-optimized directly with SSD detection loss and naturally coupled with subsequent structural and semantic refinement modules such as LEGA and CSTG.

2.3. Edge-Aware and Laplacian-Based Structural Refinement

The edges and contours, which are structural clues, are easily damaged in rain, fog, and low-illumination environments. Since the deep CNN backbone gradually loses high-frequency information through iterative downsampling and convolution, the degradation of structural features directly affects the accuracy of small-object detection and position estimation. Previous studies have combined Laplacian filters, edge pyramids, and contour recognition mechanisms to complement structural information. However, these approaches often require multi-scale reconstruction, decoder networks, and additional learning-based gradient extraction, which increases computational cost and limits their use in lightweight detection frameworks. Table 3 summarizes representative edge-aware structural refinement methods.

Table 3.

Representative methods employing edge-aware and Laplacian-based structural refinement.

Many edge-based techniques have been primarily applied in image restoration and have not been fully utilized in the detection backbone. As a result, it does not take full advantage of the opportunity to enforce structural refinement in shallow, high-resolution feature layers, where object boundaries are best preserved. To overcome these limitations, the LEGA module combines parameter-free Laplacian kernels with small-scale gating mechanisms, enabling effective boundary enhancement at a minimal computational cost. The design highlights the structural elements of the degradation layer, complementing the image-unit correction of DIP and the semantic-unit purification of CSTG.

2.4. Transformer and Gated Attention for Weather-Adaptation

Self-attention mechanism was recently introduced to enhance feature representation in complex weather environments. Methods such as Weather-aware RT-DETR, and YOLO-DH leverage multi-head attention modules, Transformer encoders, and gating-based fusion to rearrange fog or noise-damaged deep features [16,27,28]. These designs are highly expressive, improving long-range dependency modeling and semantic discrimination skills.

However, Transformer-based architectures inherently require substantial memory and computational resources. Multilayer encoders, channel expansion, and multi-head attention stacks are not suitable for real-time or edge environments. Furthermore, focusing on the entire backbone or feature pyramid can lead to redundant computations, especially in one-stage detectors where shallow and deep layers play different roles. Table 4 presents a typical Transformer/gating-based approach.

Table 4.

Representative Transformer- and gated-attention-based methods for weather-adaptive detection.

The CSTG module introduced in this work mitigates these constraints by confining Transformer operations to the deep extra layers of SSD and by integrating a lightweight content-aware gating mechanism. This selective refinement strategy maintains the advantages of global context modeling while reducing overhead, enabling effective semantic enhancement in adverse weather conditions.

2.5. Summary of Research Gap

Adverse weather detection has been investigated from three main perspectives: image-level enhancement, structural refinement, and semantic modeling. Image enhancement approaches mitigate visibility degradation caused by rain, fog, or low light, but they are often optimized independently of downstream detectors and do not consistently translate into detection accuracy gains. Edge- and Laplacian-based structural refinement techniques enhance boundary cues but typically depend on multi-scale reconstruction or decoder networks, which increase memory usage and model complexity. Transformer-and attention-based semantic refinement methods improve long-range context modeling; however, reported parameter counts, FLOPs, and inference performance in representative studies indicate that these architectures are substantially heavier than lightweight SSD- or YOLO-based detectors, making real-time deployment on edge devices challenging.

Several recent studies partially bridge multiple degradation levels by combining image-level enhancement with feature- or semantic-level refinement, for example, through detector-integrated enhancement modules or frameworks that jointly address visibility restoration and semantic filtering. Nevertheless, such designs commonly rely on auxiliary subnetworks, multi-branch fusion strategies, or degradation-specific components, which introduce additional computational overhead. Moreover, most of them still lack explicit lightweight mechanisms for reinforcing structural boundaries in shallow high-resolution feature layers while maintaining tight coupling between enhancement behavior and detection objectives.

Consequently, a unified degradation-aware framework that simultaneously addresses image-, structure-, and semantic-level deterioration in a computationally efficient, SSD-compatible manner remains largely underexplored. The proposed DLC-SSD is designed to fill this gap by organizing these three degradation layers into a single hierarchical refinement pipeline, incorporating task-driven image-level enhancement, parameter-free edge-guided structural reinforcement, and compact context-aware semantic refinement to align enhancement with detection objectives while preserving efficiency and robustness under adverse weather conditions.

3. Proposed Method

3.1. Overall Pipeline Architecture

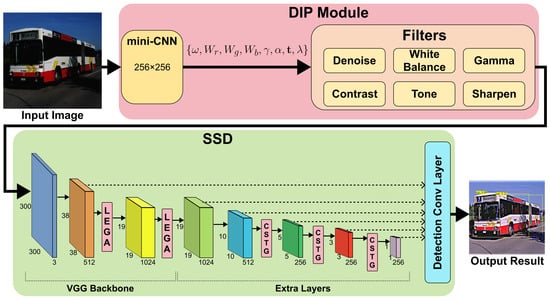

The proposed framework adopts a unified degradation-aware refinement process that restores image, structural, and semantic information affected by adverse weather. An overview of the complete architecture is shown in Figure 1. The primary processing flow is summarized as follows. This unified combination of DIP, LEGA, and CSTG, along with an SSD, forms the proposed DLC-SSD framework.

Figure 1.

Overall architecture of the proposed DLC-SSD framework.

Given an input image, a lightweight mini-CNN first analyzes its global and local characteristics to predict the parameters required by the DIP module. These predicted parameters control a sequence of learnable and differentiable filters, including sharpening, contrast adjustment, tone and gamma correction, white-balance normalization, and denoising, allowing the system to generate a task-driven enhanced image that is directly optimized for downstream detection.

The enhanced image is then processed by a VGG16-based SSD backbone that extracts multi-scale feature maps [29]. At the shallow stage, the LEGA module injects a fixed Laplacian-based structural prior to strengthen boundaries of weakened objects. This improves early feature stability in regions affected by blur or low visibility. At deeper stages, the CSTG module performs semantic refinement by jointly capturing long-range contextual relations and filtering out noise through content-dependent gating. The resulting refined multi-scale features are fed into SSD detection heads for reliable classification and localization under challenging weather conditions.

3.2. Hierarchical Image–Structure–Semantic Refinement

Adverse weather conditions degrade visual information at multiple levels. To address this, the proposed framework applies refinement hierarchically across three complementary stages: appearance-level enhancement, boundary-level structural reinforcement, and semantic-level contextual refinement. Each stage focuses on a distinct type of degraded information, enabling the overall system to adaptively restore relevant cues while maintaining computational efficiency and stable feature progression throughout the detection pipeline.

3.2.1. Differentiable Image Processing

The DIP stage is designed to restore the visual quality of the input image, which has deteriorated in an adverse weather environment, from an early stage. In this process, DIP dynamically determines the intensity of enhancement optimized for the conditions of each image by analyzing global characteristics, such as brightness, color balance, tone, and noise density. This adaptive initial restoration is a key factor in ensuring the stability of subsequent structural and semantic purification steps.

Instead of fixed heuristic settings, DIP operates based on a compact set of trainable filter control parameters predicted by a lightweight mini-CNN. The mini-CNN receives a downsampled input and outputs a parameter vector , where each element directly controls a corresponding differentiable filter. Since these parameters model global scene-level enhancement behavior rather than pixel-dependent modulation, the parameters estimated at are uniformly applied to the original full-resolution input via global broadcasting. This design significantly reduces computational cost while maintaining strong content-aware adaptability. The mini-CNN consists of multi-stage convolutional blocks followed by fully connected layers, contains only 156K parameters, and is suitable for real-time deployment.

The DIP module consists of six differentiable filters, consisting of Denoise, White Balance, Gamma, Contrast, Tone, and Sharpen, all of which are directly optimized through the backpropagation of the network. These filters operate in combination to perform adaptive enhancement tailored to the deterioration pattern of each image, and all mappings are designed to be differentiated, enabling joint optimization based on a single detection loss with the entire detection network. In particular, unlike fixed and task-agnostic enhancement techniques, this DIP module is learnable, detection-aware, and optimized end-to-end via backpropagation. These features make DIP function as a task-driven image enhancement module, closely integrated with the entire detection pipeline beyond simple preprocessing.

Denoise Filter

The proposed Denoise filter is designed to effectively eliminate wet noise, scattering, and blurring occurring in adverse weather by reconstructing the DCP-based restoration technique in a differential form. This filter is based on an atmospheric scattering model, and the input noise image is expressed as follows:

Here, denotes the clean image to be restored, A represents a global atmospheric light, and is a transmission map. The transmission map is defined as follows based on the scene depth and the atmospheric scattering coefficient :

To restore a clean image , it is essential to estimate A and . To this end, the dark channel of the input image is computed, and then A is estimated as the average value of the corresponding region by selecting the top 1000 brightest pixels. Thereafter, the DCP-based transmission map estimation equation is as follows:

Here, c denotes a color channel, and represents a local window. In this study, a learnable parameter was introduced to control the degree of suppression of the transmission map and generalized as follows:

is optimized via backpropagation and enables more robust restoration across various deterioration conditions, such as wet, low-illumination, rain, and fog environments. Since all the above equations are differentiable, the Denoise filter can be trained end-to-end with the entire detection network, enabling detection-aware restoration.

Pixel-Wise Filters

The pixel-wise filters consist of a continuous mapping function that acts directly on the input pixel . It is the most basic and computationally efficient correction operation in DIP. This filter group consists of four types: White Balance, Gamma, Contrast, and Tone, and all parameters are determined by the values predicted by mini-CNN. Since each operation has an independent pixel-wise conversion structure, the amount of computation is small even in a high-resolution image, and all functions are fully differentiated for input and parameter, so end-to-end learning through detection loss is possible.

The White Balance filter adjusts channel-wise color distortions by applying learnable scaling factors to each RGB component. For an input pixel , the corrected output is obtained through a simple linear transformation,

where , , and are the per-channel weighting coefficients predicted by the mini-CNN. This operation provides a stable and differentiable mechanism for balancing color cast under adverse weather conditions.

The Gamma filter modifies global luminance by applying a nonlinear power mapping. For each channel, the output intensity is computed as

with being a learnable gamma coefficient. This enables the model to reshape the brightness distribution of the input image and to emphasize darker or brighter regions depending on the scene illumination.

To enhance contrast, the Contrast filter interpolates between the original pixel value and a nonlinearly enhanced representation :

The enhanced representation is derived from the pixel’s luminance, defined as

which is then passed through a smooth cosine-based nonlinear transform,

and finally projected back to the RGB channels through

This formulation allows the contrast filter to enhance intensity variations while maintaining continuous gradients for stable optimization.

Finally, the Tone filter adjusts tonal characteristics using a learnable piece-wise polynomial mapping. With tone-curve parameters predicted by the mini-CNN, the output is computed as

where is an operation for limiting an input value to between 0 and 1. It is defined as follows:

This operation is not just clamping; it also serves as a soft weight for each section of the tone curve. That is, when is inside a specific section, it linearly increases from 0 to 1, determines the contribution to the tone coefficient of the section, and is saturated with 0 or 1 outside the section to create a smooth transition with the adjacent section. This structure configures tone mapping with continuous and section-specific characteristics. Since all operations are differentiable with respect to both input and learning parameters, the entire DIP can be optimized end-to-end via a detection loss.

Sharpen Filter

The Sharpen filter is inspired by the unsharp masking technique and serves to clearly restore the boundary and microstructure of the object by emphasizing its high-frequency components. The Sharpen operation is defined as the following continuous mapping function:

Here, is an input image, is a Gaussian-blurred image at the exact location, and is a trainable coefficient for controlling sharpening intensity. Since Gaussian blur extracts low-frequency components, extracts high-frequency residuals from inputs, determines how much to emphasize these residuals.

Since this mapping is completely differentiable with respect to both the input x and the scale factor , the degree of sharpening is automatically adjusted during end-to-end optimization of the entire DIP with a detection loss. This can strengthen the blurred object boundaries in challenging weather conditions and provide explicit feature representations that subsequent structural and semantic refinement steps can leverage.

3.2.2. Lightweight Edgie-Guided Attention

In adverse weather conditions, such as rain, fog, and low-light night, the contour and structural cues of the object are blurred, and background noise increases, making the boundary information in the feature map prone to loss. To reduce this structural ambiguity and preserve object shape cues, this study introduces a lightweight structure enhancement module, LEGA. LEGA aims to maintain precise contours and boundaries even when input quality deteriorates. It works in conjunction with CSTG, which performs semantic refinement, to form an image–structured–semantic enhancement flow. In particular, LEGA significantly improves detection stability for small objects or targets with blurred boundaries by directly reinforcing structural information without adding trainable parameters.

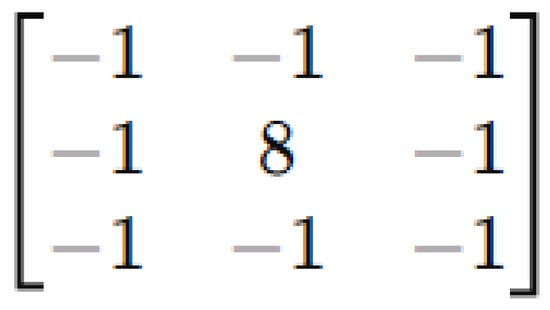

LEGA first performs depth-wise convolution on the input feature map using the non-learnable fixed Laplacian kernel presented in Figure 2. The Laplacian kernel is a classical boundary detection filter that emphasizes the high-frequency components of the central pixel relative to its surrounding pixels, thereby reliably capturing structural discontinuities, such as edges, corners, and textures, in the image. This creates an edge map E for each channel, complementing the low-level structural information that tends to degrade during downsampling.

Figure 2.

Non-learnable fixed Laplacian kernel for structure-aware edge extraction in LEGA.

The extracted edge map is converted into a structure-based attention mask A by passing through the convolution and the sigmoid activation function. This mask highlights structurally important regions and suppresses background noise and low-frequency components. This process can be expressed in an equation as follows:

Here, the is an input feature map, E is a Laplacian-based edge map, and is an attention mask weighted according to structural importance. Finally, the enhanced output feature map is calculated as element-wise multiplication as follows:

where ⊙ means a multiplication operation by position.

LEGA is applied to backbone feature maps at relatively early and intermediate stages, where the spatial resolution is still high enough to retain fine structural details near the input side of the network. A VGG16 backbone is used in the experimental implementation, with LEGA applied after the conv4_3 (the fourth convolutional block, third layer) and the fc7 layer. Since these early-stage feature maps are the stage before structural information is lost through downsampling, they are relatively rich in boundary and outline information and are particularly effective for small objects or targets with blurred boundaries. In addition, LEGA is composed of only a fixed kernel-based depth-wise convolution and a shallow convolution, so it does not add any learning parameters, and the increase in computation is minimal. This design enables LEGA to efficiently reinforce structural cues computationally, improving the clarity of object boundaries under challenging weather conditions and enhancing the robustness of the overall detection pipeline.

3.2.3. Content-Aware Spatial Transformer with Gating

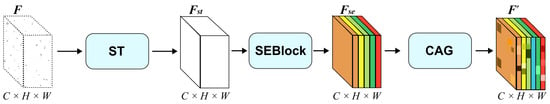

In adverse weather conditions, the boundaries of objects are blurred by rain, fog, and low illumination, background noise increases, and it is difficult to capture such complex deformations with only local convolution-based representations. In particular, the fixed receptive field of CNNs has inherent limitations in utilizing long-range dependence and global contextual information, leading to performance degradation in outdoor scenes with many small or blurred objects. To solve this problem, this study proposes a CSTG module that combines a spatial Transformer (ST) and a content-aware gating (CAG) mechanism. CSTG refines the feature expression across multiple stages by integrating global context alignment, channel readjustment, and semantic-based selective emphasis into a single lightweight structure. Figure 3 demonstrates the entire configuration flow of CSTG.

Figure 3.

Overall architecture of the CSTG module.

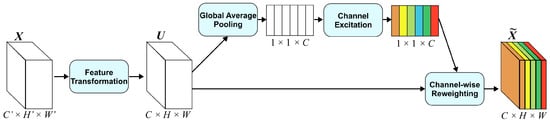

First, the input feature map is reduced in dimension via a convolution, then spread across the spatial dimension and entered into the Transformer encoder. The Transformer encoder includes multi-head self-attention, FFN, and residual connections, and models long-distance interactions across the feature map to reconstruct the global context information needed for blurred areas or obscured objects. The Transformer output is restored to its original spatial structure and projected back to the original number of channels via a convolution. Subsequently, a Squeeze-and-Excitation Block (SEBlock) is applied to re-importance channels based on the global context [30]. SEBlock summarizes the average response across the entire space and reweights the semantic importance of each channel, thereby suppressing noise channels and enhancing meaningful channels. Figure 4 shows the structure of SEBlock.

Figure 4.

SEBlock used in CSTG for channel re-weighting [30].

After global refining through Transformer and SE-based channel rearrangement, the content-based semantic selectivity is further secured by the CAG. The CAG consists of two consecutive gating blocks, each composed of a convolution followed by ReLU and sigmoid activations. It directly calculates the importance of channel and spatial units based on the regional semantic distribution of input features. Unlike SEBlock, based on the global average, it extracts gating weights directly from the original spatial structure, enabling more detailed emphasis in scenes where small objects or regional semantic changes are important. The operation of CAG is expressed as follows:

Here, F is a feature map that has undergone Transformer and SEBlock, and is the final purification output with the gating module’s content-based gate applied.

This structural design enables CSTG to continuously integrate global context, channel importance, and regional semantic information, increase the stability of feature alignment across scales, and make semantic separation between objects and backgrounds more straightforward. Sensitivity is greatly improved, especially in real-world environments with many small, blurred, and partially obscured objects. Despite their lightweight structure, they act as key factors in significantly improving robustness and discrimination in complex outdoor scenes.

3.3. Joint Optimization and Training Objective

In the entire framework proposed in this study, the DIP module that corrects the degraded quality of the input image, the LEGA module that reinforces structural clues, and the CSTG module that performs global-to-regional context alignment are all co-optimized within a single end-to-end learning scheme. At this time, all modules are designed to improve detection performance and do not require additional pre-training or independent auxiliary losses. In other words, all changes in output occurring in each module are backpropagated through the final detection loss, and the parameters of the entire network are jointly updated.

First, the DIP module applies differentiable filters using the parameters predicted by the mini-CNN, and the resulting enhanced image is then transmitted to the subsequent SSD backbone and extra layers. Since the DIP parameter is fine-tuned to enhance object detection performance rather than a fixed rule-based transformation, the entire image quality improvement process is optimized as a task-driven process. The LEGA module highlights structural boundary cues in the backbone’s show stage, improving the ability to detect small objects and blurry boundaries, and CSTG performs global context-based refinement and content-based gating in extra layers to enhance feature alignment and semantic separation across scales.

The target function of the entire network follows the SSD-based standard detection loss. In the training process, classification loss and bounding box regression loss are calculated at the same time, and the final objective function is defined as follows:

Since the DIP, LEGA, and CSTG modules proposed in this study are all completely differentiable and directly connected to detection loss, all parameters are updated together by a single objective function as follows:

Here, is a set of parameters of the entire network, including all of the DIP parameters, convolution weights, Transformer-based parameters, and gating parameters.

Through this integrated training procedure, the three steps of degradation correction–structural emphasis–contextual alignment work complementarily, providing much higher consistency and reliability than the way individual modules are designed independently. As a result, the proposed model can achieve robust detection performance even under adverse weather conditions and maintain stable detection performance across objects of varying scales and complex scene structures.

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Hardware and Software Environment

All experiments were conducted in the Ubuntu 20.04.6 LTS environment, and the server is equipped with 8 NVIDIA Tesla V100 GPUs with 32 GB of memory and AMD EPY 7742 processors. The training code was implemented in Python 3.12, and the model was trained using PyTorch 2.2.1 and CUDA 12.2. Table 5 summarizes the main components of the experimental environment.

Table 5.

Experimental environment configuration.

4.1.2. Dataset Preparation

The nuScenes dataset was used to evaluate the robustness under adverse weather conditions [31]. nuScenes contains real self-driving data collected in Singapore and Boston and includes various weather conditions (rain, fog), illumination conditions (day, night), and complex urban traffic conditions. It is also a large multimodal dataset that provides 6 cameras, a 360-degree LiDAR, and 5 radars. The annotation taxonomy comprises 23 fine-grained object classes that are further grouped into four super-categories: human, vehicle, movable objects, and static objects.

This study focuses on the human and vehicle super-categories, which are key safety-critical dynamic agents that directly interact with the ego vehicle and largely determine collision risk. These categories internally include diverse subclasses (e.g., car, truck, and bus), preserving substantial variability in object shape, size, and motion and preventing oversimplification of the task.

To construct the Filter-nuS subset, scenes in nuScenes were first filtered using the provided scene-level metadata. Specifically, scenes whose textual description field contained adverse weather keywords (e.g., rain) were selected, resulting in 95,630 candidate images. For each candidate image, the official cam_token associations and camera calibration parameters were used to project 3D bounding boxes onto the image plane and generate 2D ground-truth bounding boxes. Among these candidates, only images containing at least one pedestrian or vehicle instance were retained. Within this filtered pool, 34,143 images contained one or more pedestrian or vehicle objects. To construct a balanced and computationally tractable benchmark while emphasizing scenes where human–vehicle interaction is present, all images containing both pedestrians and vehicles were first retained, and additional images were then randomly sampled from the pedestrian-only and vehicle-only subsets. The sampled data were then manually inspected and re-selected to create the final Filter-nuS dataset.

The resulting Filter-nuS dataset contains 9950 training images and 900 test images captured under rain, fog, or low-light conditions, with 2D bounding box annotations for pedestrian and vehicle objects, as summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Filtered dataset derived from nuScenes.

4.1.3. Training Strategy

The Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) optimizer is used for model training, with an initial learning rate of 0.001, a momentum of 0.9, and a weight decay of . A linear warm-up is applied during the first 500 iterations, after which the learning rate follows the step-wise decision schedule. The entire learning was achieved with 200,000 iterations.

Training was conducted with a batch size of 32 in an 8-GPU environment, and the unbalanced anchor distribution was mitigated via hard negative mining (N:P = 3:1), a widely adopted configuration in SSD-based detectors that provides a stable trade-off between suppressing trivial negatives and maintaining sufficient positive learning signals. The prior box follows the basic SSD configuration and uses a predefined aspect ratio across six feature levels.

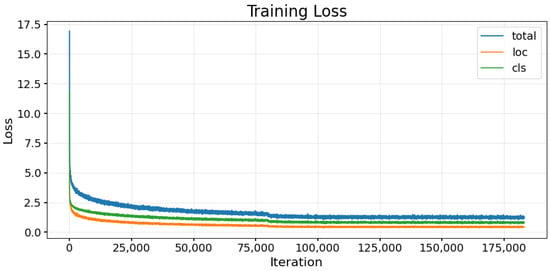

The loss function consists of Smooth L1 regression and Softmax classification losses, as in the existing SSD. Losses are calculated for positive samples and selected hard negatives, and the total loss change is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Training loss curve of the proposed DLC-SSD model on the Filter-nuS dataset.

In the inference stage, Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) with an IoU threshold of 0.45 is applied, and the confidence threshold is set to 0.01 to preserve low-confidence objects that may occur in adverse weather environments.

All reported results are obtained from a single training–testing cycle using the Filter-nuS dataset. The entire pipeline was trained with fixed random seeds and identical hyperparameter settings to ensure reproducibility. Preliminary trials showed stable convergence behavior without irregular fluctuations, and the reported results are representative of the observed performance.

4.1.4. Evaluation Metrics

The performance of the proposed model is evaluated using Mean Average Precision (mAP), a standard in the object detection field. Precision and recall definitions are as follows:

For each class, AP is computed as the area under the precision–recall curve, and the total mAP is defined as the average across all classes.

Here, P and R denote precision and recall, respectively. N is the number of classes, and is the average precision for class i. The IoU calculation formula is as follows:

This indicator is suitable for quantitatively evaluating the performance of small objects in adverse weather environments and boundary preservation in low-light environments.

4.2. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.2.1. Quantitative Comparison with Baselines

This section evaluates the quantitative performance under adverse weather conditions by comparing the proposed model with several recent object detection baselines. For comparison, the mean mAP (Mean-mAP), pedestrian mAP (P-mAP), and vehicle mAP (V-mAP) were measured on the Filter-nuS test set, and the results are summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Comparison of detection performance (mAP) of different methods on the Filter-nuS dataset.

As shown in Table 7, the proposed model achieved the best performance among all comparison methods, with a Mean-mAP of 64.29%. In particular, it attained high accuracy in pedestrian detection at 53.5% and in vehicle detection at 75%, both of which are susceptible to blurring under adverse weather conditions.

The existing image enhancement-based technique, ZeroDCE, effectively improves input image quality, but its improvement in detection performance is limited due to a lack of specialized optimization for object detection. In addition, models dedicated to adverse weather detection, such as D-YOLO, DSNet, ClearSight-OD, and AK-Net, showed lower mean-mAP than the proposed method, despite their complex structures based on feature adaptation or restoration networks. At the same time, strong general-purpose detectors like YOLO11l and RT-DETR-l, which perform well in normal-weather benchmarks, still underperform the proposed method under adverse weather, indicating that high-capacity backbones alone are insufficient without explicit degradation-aware design.

On the other hand, the proposed model obtains multi-filter-based differentiable improvement in response to deterioration factors such as brightness, color, tone, and noise through the DIP module, strengthens the structural boundary of shallow stages through LEGA, and improves global context and semantic selectivity through CSTG in an integrated manner within the SSD-based lightweight structure. In particular, it is confirmed that the total number of parameters is 29 M, which is relatively lightweight compared to existing restoration-combination models and exhibits high parameter efficiency relative to performance, while requiring only 61 GFLOPs.

4.2.2. Qualitative Results

To further assess the effectiveness of the proposed framework under adverse weather conditions, we conducted a qualitative comparison on the Filter-nuS test split. Figure 6 includes an example of visually comparing the results generated by several detection models under various deterioration conditions, such as rain, fog, and low illumination, on the Filter-nuS test set.

Figure 6.

Qualitative visualization of detection results on the Filter-nuS test set.

The existing method frequently blends pedestrians and vehicles with the background because the object outlines cannot be clearly distinguished when the boundaries are blurred. This is the case, in particular, in scenes where fog or non-structures overlap, a phenomenon in which small objects are completely omitted due to the decrease in contrast of the original image and structural loss, or, on the contrary, a change in brightness of the background is incorrectly detected. In low-light scenes, semantic features were not sufficiently expressed due to insufficient illumination, making it challenging to locate and classify objects accurately.

In contrast, the proposed model helps re-expose the basic structure of an object that appeared blurry by stably correcting brightness, color, contrast, and noise via the DIP module in the input stage. LEGA, which is then applied at the show stage, uses Laplacian-based structural signals to strengthen the outlines and boundaries of objects, more clearly reconstructing the silhouettes of small objects or those that have collapsed in shape. In addition, CSTG stabilizes overall scene representation by using global contextual information to more clearly emphasize semantically important areas and to suppress background deterioration factors relatively.

This series of processing results also shows a clear visual difference. In the proposed model, the boundary between the object and the background is clear even in cloudy scenes, and the shapes of difficult-to-recognize objects, such as small pedestrians or distant vehicles, become more evident. The example in Figure 6 shows that the proposed framework simultaneously maintains structural, color, and semantic balance under adverse weather conditions and can stably detect objects even under various deterioration conditions.

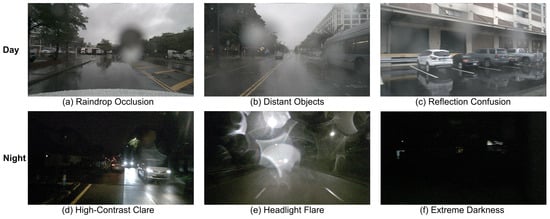

Figure 7 shows typical failure patterns of the proposed model in real adverse weather scenarios. DLC-SSD improves robustness for a wide range of degradations. However, its degradation-aware modules still rely heavily on local intensity and edge statistics to predict filter coefficients and refine features. When rain, lens contamination, extreme illumination imbalance, or severe low-light conditions distort these statistics, the estimated degradation maps and subsequent feature enhancement become unreliable, leading to missed detections, localization errors, or false positive predictions.

Figure 7.

Representative failure cases on the Filter-nuS test set.

In (a), large raindrops and water smear physically occlude key regions, so objects behind them are not visible to the detector at all. In (b), distant targets are heavily blurred and contrast-suppressed, and their weakened signals become almost indistinguishable from background noise, causing the detector to ignore them. In (c), strong reflections on wet roads generate mirror-like pseudo-objects that can be misinterpreted as real vehicles or structures. In (d), the coexistence of saturated bright areas and very dark regions produces extreme local contrast, destabilizing the degradation estimation and confusing the prediction of filter coefficients. In (e), raindrop-induced headlight flare introduces bright, irregular scattering patterns that distort the appearance of the object and create misleading feature cues. In (f), the scene is captured under such extreme darkness that almost no meaningful visual evidence remains, making reliable detection practically impossible.

4.2.3. Ablation Study

An ablation experiment was performed to quantitatively confirm the role of each component of the proposed DLC-SSD framework in the final detection performance. The experiment used the Filter-nuS test set, and performance changes were measured by sequentially combining the DIP, LEGA, and CSTG modules with the SSD basic structure. The overall results are summarized in Table 8.

Table 8.

Ablation study of the proposed components on the Filter-nuS dataset.

A pure SSD model with no enhancement module applied records a mAP of 61.01% as a reference point for basic performance. Applying the CSTG structure, including ST and CAG, slightly increases performance to 61.95%, demonstrating that Transformer-based global contextual information and gating-based semantic filtering improve the expressive power of the deep layer. Although it does not include image restoration or structure enhancement, a performance improvement of about 1%p was observed, with only semantic-level improvement. Adding LEGA to CSTG resulted in higher performance at 62.54%. Since LEGA reinforces boundary and outline information by extracting Laplacian-based structural information from the show feature, the expressive power of objects with blurred boundaries, especially in adverse weather conditions, is improved.

On the other hand, the DIP-SSD structure that uses only the DIP module achieves an mAP of 63.65%. By directly suppressing noise and correcting contrast and tone at the image stage, potential structural information of the object is reconstructed more clearly at the input stage, resulting in a sufficiently significant performance improvement even without feature-level improvement. However, due to the lack of semantic-level adjustment (CSTG) or shallow-edge correction (LEGA), a limit in which feature alignment is not sufficiently stable in certain scenes is also observed.

Finally, the overall model (DLC-SSD), which integrates DIP, LEGA, and CSTG, achieved the highest performance with an mAP of 64.29%. This is 3.28%p higher than the basic SSD, 1.75%p higher than the CSTG-SSD, and 0.64%p higher than the DIP-SSD, and clearly shows that the multilayer correction in the image–structure–meaning stage works in a complementary manner. In particular, the performance difference was more pronounced in subcategories with a high proportion of small objects, meaning that the combination of LEGA and DIP enables stable contour restoration even in structurally weak inputs.

Overall, ablation experiments demonstrate that each module provides meaningful improvements on its own, but the highest consistency and robustness are achieved when the three modules are integrated. This is the key basis for showing that the proposed multi-level unified refinement strategy is not a simple module combination but a practical synergy effect enabled by a complementary structure.

4.2.4. Efficiency Analysis

This section quantitatively verifies the lightweight, real-time performance of the proposed DLC-SSD framework. As can be seen from Table 7, the total number of parameters of the proposed model is about 29 M, which is significantly less than conventional models for adverse weather response, such as D-YOLO (46 M), ClearSight-OD (60 M), and AK-Net (75 M), and is comparable to recent general-purpose detectors such as YOLO11l (25 M) and RT-DETR-l (31 M). In addition, the computational cost of DLC-SSD is 61 GFLOPs, which is lower than that of other models, while maintaining superior detection performance under adverse weather conditions. This is the result that the DIP, LEGA, and CSTG modules are all designed to improve performance without significantly changing the basic structure of the SSD based on a lightweight design.

The DIP module includes various differentiable filters, but each filter is configured as a single operation, so there is little increase in parameters, and the number of operations is also limited because a small mini-CNN predicts the filter parameters. LEGA also maintains a structure with a few additional parameters, using only fixed Laplacian operations and convolutions, and CSTG is designed with a one-layer Transformer encoder and a simple gating block, which is very efficient compared to existing attention-based models.

The inference speed also supports the lightweight nature. In the ablation study of Table 8, the reference time of the proposed model was measured as 19 ms, which is only a slight increase compared to the existing SSD. This efficiency is possible because the DIP operates only in the image input stage, and the CSTG and LEGA are designed to be applied only to a specific layer, not to the entire multilayer feature.

Taken together, the proposed DLC-SSD model maintains the lightweight, high-efficiency structure of the SSD-based model despite including additional modules, and provides performance and processing speed that can be applied immediately, even in a harsh weather monitoring environment where real-time object detection is required. This confirms its value as a practical framework that secures both accuracy and efficiency.

5. Discussion

The proposed DLC-SSD framework demonstrates that organizing image-level enhancement, structural reinforcement, and semantic refinement into a unified hierarchical pipeline can substantially improve robustness under adverse weather while preserving real-time efficiency. Across the Filter-nuS evaluations, DLC-SSD consistently maintains higher detection performance than the baseline detectors under comparable computational budgets, suggesting that explicitly modeling degradation-aware processing is at least as important as simply scaling backbone capacity for this regime. In this sense, the contribution of DLC-SSD is primarily architectural and system-level: it shows how a carefully composed hierarchy of lightweight components can turn a conventional single-frame detector into a more weather-aware detection module without sacrificing deployment-friendly complexity.

The ablation analysis further clarifies the roles of the individual modules. The DIP block provides coarse, image-level compensation that normalizes global contrast and illumination, thus stabilizing subsequent feature extraction under rain, fog, and low-light conditions. LEGA reinforces spatial structures by emphasizing edge-aligned responses, which is particularly beneficial for preserving object contours when small vehicles or pedestrians are partially washed out by degradation. CSTG adaptively modulates spatial attention and channel-wise importance based on scene content, enabling the detector to focus on degradation-resistant cues while suppressing spurious activations. Casting the components as task-specific DIP, LEGA, CSTG modules and integrating them into a unified hierarchy within a lightweight SSD-style detector constitutes an architectural contribution in its own right, yielding substantial robustness gains under adverse weather while maintaining deployment-friendly complexity.

At the same time, qualitative failure analysis reveals several boundaries of the current design. DLC-SSD still struggles when raindrops or water streaks cause severe local occlusions, when distant objects occupy only a few pixels and are easily confused with background noise, and when strong reflections on wet roads or glass surfaces distort object contours. In addition, scenes with extreme contrast between bright light sources and dark surroundings can induce unstable filter responses and attention weights, leading to missed detections or false positives around headlights and specular highlights. These patterns are broadly consistent with known limitations of 2D, appearance-based single-frame detectors, and indicate that even with more advanced image-space operations, such as content-aware contrast enhancement or reflection and artifact suppression, the visual evidence in single RGB frames often remains intrinsically ambiguous under such complex degradations. This suggests that degradation-aware image normalization should be complemented by temporal or multimodal cues, such as depth, LiDAR, and radar, rather than relying on image-space processing alone to fully resolve these challenging cases.

Several constraints should therefore be considered when interpreting real-world applicability. The current evaluation is conducted on a Filter-nuS subset focusing on rain, fog, and low-light scenes and on the human and vehicle super-categories, which limits direct generalization to broader object groups, daytime conditions, and more diverse degradation types. Moreover, DLC-SSD operates on single-frame 2D RGB input, without exploiting temporal continuity, depth cues, or multimodal sensing, such as LiDAR or radar, that are frequently available in practical deployments. From a training perspective, the DIP module is indirectly supervised only through the downstream detection loss, and the hard negative mining policy uses a fixed 3:1 (N:P) ratio following standard SSD practice. While effective and aligned with common configurations, these choices may not be optimal under heterogeneous degradation levels or class imbalance patterns, and the present setting does not explicitly address potential label noise or ambiguous annotations. Finally, although fixed seeds and stabilized optimization are used to reduce stochastic variance, the reported performance is based on a single training run rather than multi-seed statistics, which should be kept in mind when interpreting small performance.

Future work can thus proceed along several complementary directions. On the evaluation side, extending experiments to additional adverse weather benchmarks and broader taxonomies, such as BDD100K-weather, Cityscape variants, or other multi-condition urban driving datasets, would clarify how well the proposed hierarchy transfers across domains and object classes. On the modeling side, learning DIP parameters under explicit degradation supervision, or conditioning them on estimated weather attributes, may enable more fine-grained and adaptive enhancement. Dynamic hard negative mining and noise-aware sample selection strategies, such as progressive sample selection with contrastive learning, could help better accommodate heterogeneous difficulty levels and annotation uncertainty [32]. Finally, integrating DLC-SSD-style degradation-aware modules into temporal or multimodal detection pipelines, including sequence-based and sensor-fusion architectures, is a promising avenue to further improve robustness while preserving the lightweight characteristics that make the framework attractive for road monitoring, intelligent transportation, robotics, and automotive applications.

6. Conclusions

This study introduced DLC-SSD, a lightweight and real-time detection framework designed to mitigate visibility degradation, structural distortion, and semantic inconsistency caused by adverse weather. By hierarchically integrating task-driven image enhancement, parameter-free edge-guided structural reinforcement, and compact content-aware semantic refinement within an SSD-based architecture, the proposed approach improves robustness while preserving efficiency. Experiments on the Filter-nuS benchmark show that DLC-SSD achieves superior accuracy compared with representative adverse weather detection and enhancement-based baselines, while maintaining near real-time inference speed. These results suggest that degradation-aware hierarchical refinement provides a practical and scalable direction for robust detection in resource-constrained systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K., C.J., and Y.S.; methodology, S.P., J.K., C.J., and Y.S.; software, J.K. and H.K. (Hyunsu Kim); validation, S.P., J.K., and Y.S.; formal analysis, J.K. and C.J.; investigation, S.P., H.K. (Hyunsu Kim), and H.K. (Hyunseong Ko); resources, J.K. and H.K. (Hyunseong Ko); data curation, S.P. and J.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P., J.K., and H.K. (Hyunsu Kim); writing—review and editing, S.P., C.J., and Y.S.; visualization, S.P., J.K., and H.K. (Hyunsu Kim); supervision, Y.S.; project administration, C.J. and Y.S.; funding acquisition, C.J. and Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Commercialization Promotion Agency for R&D Outcomes (COMPA) grant funded by the Korea government (Ministry of Science and ICT) (2710086167). This work was supported by the Commercialization Promotion Agency for R&D Outcomes (COMPA) grant funded by the Korea government (Ministry of Science and ICT) (RS-2025-02412990).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The nuScenes dataset is available at https://www.nuscenes.org/nuscenes (accessed on 23 November 2025) [31].

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported by Wonkwang University in 2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Seo, A.; Woo, S.; Son, Y. Enhanced Vision-Based Taillight Signal Recognition for Analyzing Forward Vehicle Behavior. Sensors 2024, 24, 5162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, F.F. Optics of the Atmosphere: Scattering by Molecules and Particles. Phys. Today 1977, 30, 76–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Sun, J.; Tang, X. Single image haze removal using dark channel prior. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Miami, FL, USA, 20–25 June 2009; pp. 1956–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Pan, J.; Xiang, L.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, F.; Yang, M.H. Multi-Scale Boosted Dehazing Network With Dense Feature Fusion. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 2154–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ma, Y.; Shi, Z.; Chen, J. GridDehazeNet: Attention-Based Multi-Scale Network for Image Dehazing. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 7313–7322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Li, C.; Guo, J.; Loy, C.C.; Hou, J.; Kwong, S.; Cong, R. Zero-Reference Deep Curve Estimation for Low-Light Image Enhancement. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 1777–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.T.; Bak, S.H.; Han, S.S.; Son, Y.; Park, J. Non-contrast CT-based pulmonary embolism detection using GAN-generated synthetic contrast enhancement: Development and validation of an AI framework. Comput. Biol. Med. 2025, 198, 111109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Son, Y. Generating Multi-View Action Data from a Monocular Camera Video by Fusing Human Mesh Recovery and 3D Scene Reconstruction. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.C.; Le, T.H.; Jaw, D.W. DSNet: Joint Semantic Learning for Object Detection in Inclement Weather Conditions. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 43, 2623–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, Z. D-YOLO a robust framework for object detection in adverse weather conditions. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.09233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.H.; Huang, S.C.; Hoang, Q.V.; Lokaj, Z.; Lu, Z. Amalgamating Knowledge for Object Detection in Rainy Weather Conditions. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2025, 16, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2016, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Leibe, B., Matas, J., Sebe, N., Welling, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.Q.; Zheng, P.; Xu, S.T.; Wu, X. Object Detection With Deep Learning: A Review. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2019, 30, 3212–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Jin, J.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, C. WRRT-DETR: Weather-Robust RT-DETR for Drone-View Object Detection in Adverse Weather. Drones 2025, 9, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.u.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All you Need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Guyon, I., Luxburg, U.V., Bengio, S., Wallach, H., Fergus, R., Vishwanathan, S., Garnett, R., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, J.; Han, M.; Li, S.; Miao, H. ClearSight: Deep Learning-Based Image Dehazing for Enhanced UAV Road Patrol. In Proceedings of the 2024 5th International Conference on Computer Vision, Image and Deep Learning (CVIDL), Zhuhai, China, 19–21 April 2024; pp. 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Ren, G.; Yu, R.; Guo, S.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, L. Image-Adaptive YOLO for Object Detection in Adverse Weather Conditions. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2112.08088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalwar, S.; Patel, D.; Aanegola, A.; Konda, K.R.; Garg, S.; Krishna, K.M. GDIP: Gated Differentiable Image Processing for Object-Detection in Adverse Conditions. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.14922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogino, Y.; Shoji, Y.; Toizumi, T.; Ito, A. ERUP-YOLO: Enhancing Object Detection Robustness for Adverse Weather Condition by Unified Image-Adaptive Processing. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.02799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.; Kotlyar, O.; Andreasson, H.; Lilienthal, A.J. Robust Object Detection in Challenging Weather Conditions. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2024; pp. 7508–7517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiasi, G.; Fowlkes, C.C. Laplacian Pyramid Reconstruction and Refinement for Semantic Segmentation. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1605.02264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Sun, H.; Liu, N. B2Net: Camouflaged Object Detection via Boundary Aware and Boundary Fusion. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2501.00426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, N.T.; Hoang, D.H.; Nguyen, Q.T.; Tran, M.T.; Le, N. MEGANet: Multi-Scale Edge-Guided Attention Network for Weak Boundary Polyp Segmentation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.03329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Ma, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, S.; Sun, J. BorderDet: Border Feature for Dense Object Detection. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2007.11056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharatappeh, S.; Sekeh, S.; Dhiman, V. Weather-Aware Object Detection Transformer for Domain Adaptation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.10877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Ma, G.; Guo, W.; Sun, Y. YOLO-DH: Robust Object Detection for Autonomous Vehicles in Adverse Weather. Electronics 2025, 14, 4476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Caesar, H.; Bankiti, V.; Lang, A.H.; Vora, S.; Liong, V.E.; Xu, Q.; Krishnan, A.; Pan, Y.; Baldan, G.; Beijbom, O. nuScenes: A Multimodal Dataset for Autonomous Driving. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Cordeiro, F.R.; Chen, Q. PSSCL: A progressive sample selection framework with contrastive loss designed for noisy labels. Pattern Recognit. 2025, 161, 111284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.