Abstract

Driven by technological innovation, service diversification, and the evolution and defects of current networks, the 6th-generation (6G) network architecture is lacking in research. One of the challenges in this research is that the architectural design should take into account multiple factors: customers, operators, and vendors. For service-oriented and network-oriented design requirements, this article proposes a data-driven distributed autonomous architecture (DDAA) for 6G with a three-layer four-plane logical hierarchy. The architecture is simplified as four network function units (NFUs), the interaction among which is carried via dual-bus interfaces, i.e., the service-based interface (SBI) and data transmission interface (DTI). In addition, it is user data-centric and rendered as distributed autonomous domains (ADs) with different scales to better adapt to customized services. Different transition stages from the 5th generation (5G) to 6G are discussed. Network simplification evaluation is further provided by going through several signaling procedures of the 3rd-generation partnership project (3GPP), inspiring advanced research and subsequent standardization of the 6G network architecture.

1. Introduction

Network architecture is an essential issue in 6th-generation (6G) research. It should adapt the requirements of emerging service scenarios and promote the implementation of promising innovative technologies. In addition, 6G is expected to solve the bottlenecks exposed by the current network and consider the friendliness and sustainability of the communication industry’s ecology [1].

According to International Telecommunication Union—Radiocommunication (ITU-R), six typical 6G usage scenarios will be enhanced and expanded on the basis of 5th-generation (5G) scenarios [2], which call for the 6G network to provide higher capabilities. For 5G enhancement, 6G is expected to optimize peak data rate and latency; improve reliability, mobility and connectivity density; and enhance user-experienced data rate and area traffic capability. In addition, it is also supposed to provide new capabilities, e.g., centimeter-precision positioning, radio interface sensing [3], ambient intelligence, seamless coverage, high energy efficiency, and high interoperability. This will realize the 6G vision of “integrated communication and sensing of virtual-reality, all-domain intelligence connectivity” [4].

The above capability requirements have spawned various prospective technologies, while the achievement of these technologies depends on the network architecture’s design. For example, to improve forwarding performance, network programming and segment routing over internet protocol version 6 (SRv6) technology can be deployed on mobile networks, so the redesign of the user plane framework and protocol stack is required. For connection extension and cross-network domain interaction, block chain technology can be combined with discovery and trust mechanisms among distributed networks. To provide seamless coverage, multi-access adaptational design of the access network is required for enabling space–air–ground–sea integration technology [5]. The combination of cloud-native technology with federated learning and semantic communication enriches network AI and also calls for the introduction of an intelligent plane into the network logical function planes [6].

However, existing network capabilities cannot yet meet the requirements of these scenarios, and existing technologies cannot be well penetrated using the current network architecture. First, as the network architecture is complex and the number of network functions (NFs) is large, the launch of new capabilities will involve so many factors that standardization, development, and deployment will be difficult. Moreover, as the network is tightly coupled, its self-detection and self-healing abilities are poor, and its reliability and service guarantee ability need to be significantly improved. In addition, due to deployment demands, technical implementation, and vendor interoperability, numerous redundant data is scattered in multiple NFs, and the diversity of the data scale, reading and write performance, life cycle, and asynchrony of data status will increase the workload and reduce the efficiency of service-based interface (SBI) data transmission.

To address these problems, [7] proposes a 6G logical architecture with three bodies, four layers, and five planes. Distributed small cloud units can support flexible deployment and plug-and-play. More atomic services are introduced into the holistic service-based architecture (HSBA), with better flexibility and management complexity. Refs. [8,9] re-group the control plane as a 3-component core network using procedures instead of network functions, including front-end interaction with UE, workers performing the 5G or 6G procedures, and subscriber states to hold per-subscriber states, thus reducing the complexity of the 6G core network. Our preliminary work [10] adds some functions and a data and intelligence plane in the service-based architecture to support AIaaS (AI as a Service), CPaaS (Computing Power as a Service), and SaaS (Sensing as a Service). However, the deep coupling of data plane and intelligent plane is not conducive to flexible collaboration among multiple service dimensions of 6G, e.g., communication, sensing, intelligence, computing, data, etc. Ref. [11] proposes a virtualized network slicing-based architecture for ensuring 6G flexibility. Cloud slicing, radio access network (RAN) slicing, and application slicing are contained to enable various technologies and applications of the 6G network. Network slicing focuses more on networking and service provisioning rather than functional enhancement. Ref. [12] discusses architectural approaches for 6G networks and concludes that the combination of digital twin and advanced machine learning approaches will benefit 6G network configuration and management. Moreover, ref. [13] also lists distributed ledger technology (DLT) and post-quantum cryptography (PQC) as potential technology trends and analyzes the paradigm shifts from 5G to 6G, e.g., cloud AI to network AI, connection-oriented to task-oriented approaches, and generic bit pipes to user-centric network services.

In general, existing work has revealed the following situation: 6G services tend to be diversified and involve multi-dimensional integration, especially generative AI applications and AI-native networks. NFs are required to support more abundant functionalities and services. Greater volume of user data, NF data, and service status will also need to be maintained by the network. If the 6G network entities are superimposed on the 5G NFs according to the evolutionary roadmap, the 6G network system will be extremely complex, while existing work gives less consideration to network simplification. Therefore, a typical legacy issue lies in how we might balance enriching network services/functionalities and simplifying network architecture.

Based on the simplification principle of high cohesion and low coupling, this article gives some viewpoints on 6G network architecture, and the main contributions are summarized as follows.

- Comprehensive insights into architectural design requirements. Give insights for the architecture design requirements from the service and network perspectives. We consider the following goals: (1) Providing customers with more ubiquitous access and better service experience. (2) Providing operators with more convenient management and deployment. (3) Providing vendors with more scalable function layout and equipment development.

- Novel service framework and physical architecture. To cater to the above design requirements, we propose a data-driven distributed autonomous architecture (DDAA) with a three-layer four-plane logical hierarchy. DDAA drives network tasks around user data. It improves the efficiency of function development and resource utilization and optimizes network performance and user service experience. Distributed autonomy ensures network security and reduces signaling storm via intra-domain autonomy and extends connectivity via inter-domain connectivity.

- Instantiated evaluation of network simplification. The masses of network functions are simplified and restructured into four network function units (NFUs) that interact via dual-bus interfaces. Network simplification and signaling reduction between 5G and 6G is detailed and evaluated by going through 3GPP underlying procedures.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the design requirements for the 6G network architecture, including the service-oriented and network-oriented requirements in Section 2.1 and Section 2.2, respectively. Section 3 provides the network architecture for 6G, including the service framework of the three-layer four-plane in Section 3.1 and the DDAA in Section 3.2. Section 4 demonstrates and analyzes the network performance evaluation. Finally, Section 5 summarizes this paper.

2. Design Requirements for Network Architecture

The design requirements for a 6G network architecture are driven by emerging service scenarios and current 5G network defects, corresponding to service-oriented and network-oriented approaches, respectively. The latter may contribute to the realization of the former.

2.1. Service-Oriented Design Requirements

Integration requirement of services. Emerging services represented by completely immersive XR, digital twins, industrial Internet, multidimensional sensory communication, and brain-computer interface are booming [14]. Meanwhile, higher performance requirements for the 6G network are being put forward, and new service measurement dimensions such as quality of physical experience may be introduced [15]. These burgeoning services will require more than the fundamental connectivity. For example, besides stable connectivity and low-latency high-reliability, tele-surgery in smart healthcare services also requires high-precision sensing for surroundings and physical motions. Large-scale modeling and simulation of this smart system also need ubiquitous intelligence and computing resources. Therefore, the 6G network is supposed to provide integrated services including connectivity, sensing, intelligence, and computing power, etc.

Flexible and customized service requirements of customers and industries. In order to meet the requirements of various customized networks while absorbing more participants to build a more open industrial ecology, the 6G network should be more scalable and agile [16] and needs the enabling of network cloudification and servitization. To enhance the adaptability of the network to services, the 6G network should support on-demand orchestration and deployment, on-demand service loading, and on-demand traffic scheduling. In addition, to-business (2B) and to-customer (2C) networks have obvious differences in service characteristics, network deployment, and management schemes. Different industries and enterprises have significant differences in network requirements, so attention should also be paid to the overall planning of 2B and 2C in the network architecture design.

2.2. Network-Oriented Design Requirements

Simplification requirement of network architecture. With the support of new scenarios and functions, the number of 5G NFs is significantly increasing, and the number of logical interfaces and HTTP signaling links is also increasing substantially. Due to the strong interdependence of NFs in signaling procedures and data interaction, the number of NFs and the workload of interoperability tests involved in malfunction location or new function deployment are huge, and network operation and maintenance are complicated [17,18]. Therefore, the 6G network is expected to achieve flat networking, flexible and dynamic cutting of NFs, data and service separation of interfaces, and micro-service processing of procedures, thereby simplifying the overall network design and the difficulty of operation and maintenance.

User data-centric requirements. Under the current 5G architecture, user provisioning is complicated, and data redundancy is high, resulting in storage waste, data inconsistency, and sharing difficulty. Therefore, the 6G network should provide consistent services for data storage, access, management, and security, and the unified and standard data organization must also be more conducive to exploiting the advantages of professional database technology in simplifying data processing logic. In addition, the reliability of the 5G network mainly depends on disaster recovery at the NF level, which has a large spread range and long recovery time after malfunction. Therefore, stateless design of NFs around data is required to separate data from service logic, reduce storage resource occupation and data interaction overhead, and improve network reliability.

Endogenous intelligence requirement. The intelligence of the 5G network mainly relies on the centralized analysis of independent AI functions, e.g., the network data analytics function (NWDAF), whereas other NFs do not have AI capabilities. Therefore, NWDAF needs to collect mass data and use highly aggregated computing power, occupying excessive communication network resources and leaving plenty of available edge computing power idle. Especially in large-scale networking, real-time operation and efficiency are more difficult to guarantee when using centralized intelligent processing, analysis, and feedback. Therefore, the collaboration of centralized AI and distributed AI, i.e., the mixture of independent AI and embedded AI, is required to achieve on-demand data collection, distributed model training, and multi-point computing power collaboration, thus jointly constructing an intelligent concise 6G network. Endogenous intelligence refers to embedded AI, which can be embedded within NFs and reflected as AI agents. Efficient collaboration among multiple AI agents is required to empower the endogenous intelligence network, based on protocols such as the agent-to-agent (A2A) protocol and model context protocol (MCP) [19] and learning mechanisms such as multi-agent proximal policy optimization (MAPPO) with observation abstraction (OA) [20,21].

Robustness and security requirement. Existing networking mode mainly presents a centralized 2C public network and dispersive 2B customized network. Centralized public network malfunction has a large range of impact and low reliability. Isolation among independent private networks remains to be improved, and security is low. In addition, coverage enhancement should abandon traditional techniques of infinite coverage expansion of one net so as to avoid high coupling among multiple NFs. Therefore, distributed network construction is urgently needed to reduce the signaling storm in the case of network malfunction; improve network isolation and security through intra-domain autonomy; expand the network range through inter-domain connectivity without affecting the original network; and satisfy differentiated network requirements under the premise of high robustness and high security.

3. Network Architecture for 6G

This section describes the 6G network architecture. At the logical level, Section 3.1 provides the three-layer four-plane service framework. At the physical level, Section 3.2 provides the functional entities and their organization architecture, i.e., the proposed DDAA with four NFUs interacting via dual-bus interfaces.

3.1. Service Framework of Three-Layer Four-Plane

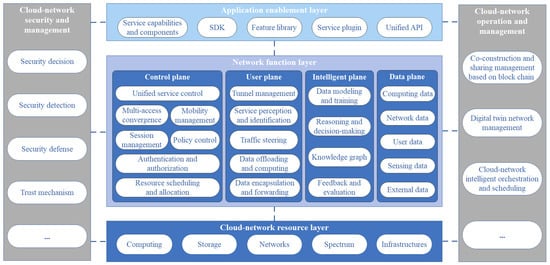

The three-layer four-plane service framework is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Service framework of three-layer four-plane. The four planes belong to the network function layer. Cloud network operation, security, and management penetrate through all the network dimensions to provide network orchestration, management, and security guarantee.

- Three-layer: In line with the trends of cloud network convergence and the service-based network, the three layers from the bottom to the top are the cloud network resource layer, network function layer, and application enablement layer, respectively.

- Cloud network resource layer. As the fundamental bearing of network functions, it integrates the infrastructures and resources, including computing resources (e.g., CPU, GPU, FPGA), storage resources, transport networks, frequency spectrum, and heterogeneous infrastructures.

- Network function layer. It provides network capabilities including the fundamental connectivity capability and the emerging computing, intelligence, sensing, data and other integrated capabilities. This layer can be further divided into the control plane, user plane, data plane, and intelligent plane. The design of the network function layer is of vital importance in the network architecture evolution.

- Application enablement layer. It aggregates network service capabilities and common application service components and provides a feature library, SDK, and service plugin. By means of capability exposure and the application enablement framework, services for the applications and surrounding ecosystems can be supplied, and the integrated application enablement management can be achieved by the unified API.

- Four-plane. Inheriting and enhancing the current control plane and the user plane, the 6G network functional plane will be expanded to the intelligent plane and the data plane for the service requirements of “connectivity plus”.

- Control plane. It is regarded as the network control center. At the service level, it is responsible for the unified control of network services such as connectivity, intelligence, computing, and sensing. At the network function level, it works in close collaboration with other layers to achieve the integrated management and control of multi-access convergence, authentication and authorization, mobility management, session management, policy control, and resource scheduling and allocation.

- User plane. It supports network programming and can flexibly define data processing policies. The specific functions include tunnel management, data flow identification, service perception, data offloading and computing, data encapsulation and forwarding, and traffic steering. The user data, surroundings and physical entity sensing data, and AI and computing task data can be processed and forwarded on the user plane. The on-path processing on the user plane proceeds according to the policies and rules distributed by the control plane, such as traffic detection rules, forwarding action rules, computing action rules, etc.

- Intelligent plane. As the intelligent center of the 6G network, the intelligent plane supports the comprehensive intelligence of core network and access network. The intelligent plane not only serves the intelligence of the 6G network endogenously but also serves the intelligent requirements of users and applications. The intelligent plane provides network AI related functions, including data modeling, model training, reasoning, decision making, knowledge graph, and feedback and evaluation.

- Data plane. The data plane is introduced to realize the separation of data and service logic. The data is presented as a dedicated and purified database, which is decoupled from the data processing. The data plane manages various kinds of data in the network and exposes it to the control plane, user plane, and intelligent plane through the standardized interface. Static data and dynamic real-time data—such as user subscription data, user context data, network status data, connectivity data, resource utilization data, external application data—are included in the data plane.

Cloud network operation, security and management penetrate through all the network dimensions. Driven by the integration trend of cloud and network, 6G network operation and management will introduce new operational functions, such as cloud network intelligent orchestration and scheduling, digital twin network management, and block chain-based co-construction and sharing management based on current network management, service acceptance, and charging and settlement functions. Security is another essential issue in 6G, which can be guaranteed through the trust mechanism, security detection, and defense decisions of cloud network security and management. For example, network security and user privacy can be guaranteed by means of distributed autonomous networking and management patterns, as discussed in the next subsection.

3.2. DDAA for 6G

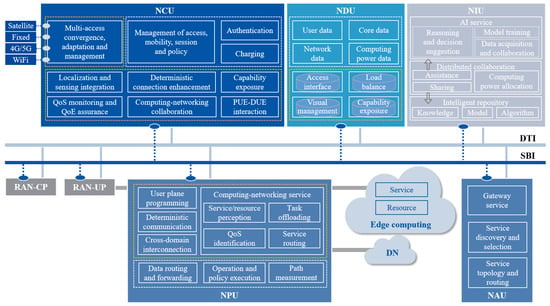

DDAA for 6G is proposed and shown in Figure 2. The masses of NFs are simplified to four NFUs, i.e., the network control unit (NCU), network packet unit (NPU), network intelligence unit (NIU) and network data unit (NDU), respectively, corresponding to the four planes in the network function layer. Moreover, service discovery and selection, service topology, and routing and gateway service among the NFUs are supported by the network assistance unit (NAU). The logical design of these NFUs requires the splitting and reassembling of the original NFs rather than simple stacking of their functionalities. These NFUs are interconnected through the dual-bus interface composed of the SBI and data transmission interface (DTI) in order to adapt to the different transmission requirements of signaling and multiple types/sizes of data in the network.

Figure 2.

DDAA for 6G. NFUs include NCU, NPU, NIU, and NDU, respectively, corresponding to the control plane, user plane, intelligent plane, and data plane in the network function layer. They interact via dual-bus interfaces i.e., SBI and DTI, for different transmission requirements. NAU provides the discovery, topology, and routing and gateway service among NFUs.

Why data-driven? The ultimate service object of the network is the user, to whom the most critical information is data. Therefore, the concept of data-driven operation is proposed. It refers to the rapid iterative development of network functions around user data, and user-centric unified data organization and management to drive network tasks. Based on a data-driven architecture, the control plane can provide capabilities around the user’s full data and can avoid data inconsistency, invalid data redundancy, and waste of storage resources. Unified standard data organization is beneficial in simplifying data processing logic and reducing existing intercall operations among NFs.

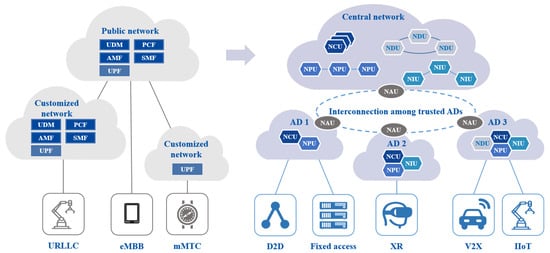

Why distributed autonomy? When upgrading functions or launching new features, collaboration among multiple NFs is required. It is indicated by the 5G current network data that more than 50% of network operations involve coordination among multiple NFs, and 80% of coordination is control plane coordination. As shown in Table 1, the deployment of NFs requires numerous cooperative NFs (up to dozens of times), which limits the rapid commercial usage of new services. To meet robustness and security requirements, distributed autonomous networking, i.e., autonomous domains (ADs), is expected to be deployed. As shown in Figure 3, the NFUs deployed in each AD can be customized according to the differentiated service scenarios. Each AD can provide services independently, which is convenient to deploy across vendors and operators. When the cross-AD communication is required to support more extensive and complex service scenarios, the ADs can interact with each other to integrate multi-dimensional resources. The interaction among ADs is performed by the NAUs while hiding the topology, ensuring security isolation and no private data leakage among ADs. The malfunction of one AD will not affect the running of other ADs. Therefore, when malfunction occurs, the signaling storm range, operation and maintenance difficulty, and recovery time will be reduced.

Table 1.

Reference data for the deployed NFs and cooperative NFs.

Figure 3.

Distributed autonomous networking for 6G. The forms of centralized public network and dispersive customized network are expected to evolve into multiple distributed ADs. Network security and robustness can be better guaranteed in this way.

- NCU in the control plane.NCU covers the basic capabilities of 5G NFs in the control plane and further provides adaptive access, digital twin UE (DUE), and other extended capabilities. First, as the primary element of the network control center, NCU is responsible for signaling interaction and inherits existing network capabilities, such as access management, mobility management, session management, policy management, authentication and charging. Moreover, driven by emerging services, NCU will also provide a variety of scalable on-demand services and flexibly selectable capabilities, such as computing–networking collaboration, localization and sensing integration, deterministic connectivity enhancement, QoS monitoring, and QoE assurance. In addition, based on the principle of compatibility with various access paradigms, NCU provides multi-access adaptor for user equipment (UE) with different access paradigms and capabilities. The access adaptor can flexibly achieve access convergence, adaptation, and management for satellite, fixed, mobile, and WiFi services. From the UE perspective, NCU can realize plug-and-play UE with no perception of multiple access paradigms and no dependence on chip maturity. Last but not least, NCU constructs digital twins revolving around the user’s intact data, i.e., DUE twins the physical UE (PUE) and dynamically presents and manages the PUE in the digital domain. Note that the critical ability of DUE is not only to twin PUEs but also to drive and assist PUEs to accomplish their unattainable tasks. This significantly expands the capabilities of the PUEs from the network side without increasing the requirements of PUEs.

- NPU in the user plane.Following the design principle of control and forwarding separation, NPU implements servitization enhancement based on UPF. NPU inherits the traditional functions of service data routing and forwarding, operation and policy execution, and path measurement. NPU is evolving towards user plane programming, deterministic communication, cross-domain connectivity, and computing–networking services such as resource perception, service perception, task offloading, QoS identification, and service routing. On-demand and scenario-specific network customization can be realized so as to meet the requirements of real-time mobile services such as drones, V2X, and brain–computer collaboration.

- NDU in the data plane.The basic concept of NDU lies in the development of data applciation alongside separation from data. NDU is responsible for the unified storage, management, and access of data. The load balance, access interface, security management, visual management, and capability exposure are supported by the distributed database engine of NDU. The data contains user data, network data, core data, and computing power data. User data refers to the end-to-end data information of users, e.g., access capability, low/medium/high-speed label, real-time tracking, the network capability in use, and the task/service in progress. Network data refers to the management data, running data, and the service-level agreement (SLA) data of network nodes, such as slice management, network node load, and network service SLA data. Core data refers to the user static data, e.g., user subscription data, service policy data, and service subscription data. Computing power data refers to the user’s consumption data of computing power resources, and the service data built on them, including common computing power data, heterogeneous computing power data, computing power service data, etc. The data can be shared with other NFUs and exposed in the form of API interfaces.

- NIU in the intelligent plane.NIU is the enabler for network endogenous intelligence. It can exist independently or be embedded in NCU, NPU, and NDU. Internally, NIU applies AI to the network, so as to improve the intelligence, flexibility, and simplicity of network. Externally, NIU provides flexible AIaaS to assist applications to provide network services such as network performance analysis and prediction, routing selection, and QoS configuration. NIU consists of three major functional modules: AI service, intelligent repository, and distributed collaboration. The AI service includes three layers. The data acquisition and collaboration layer can control and distribute the data of the NDU and intelligent repository required for model training. The model training layer provides model training, evaluation, and management, focusing on federated learning, transfer learning, and multi-agent reinforcement learning based on which, reasoning and decision suggestion layer executes AI reasoning tasks and provides decision-making results and suggestions for load analysis, congestion prediction, resource state prediction, service tailoring, etc. The intelligent repository has a complete algorithm/model repository and knowledge repository to improve learning efficiency and the intelligence level. Distributed collaboration enables cross-layer and cross-domain AI collaboration by interaction between data and model parameters, and it provides functions such as data/knowledge sharing, training/reasoning/decision assistance, and computing power allocation to achieve AIaaS.

Dual-bus interfaces. The dual-bus interface includes SBI and DTI; they can process data asynchronously without affecting each other, so as to achieve more efficient and diverse data services. The dual-bus interface achieves the decoupling between data interaction and signaling interaction. The SBI signaling bus transmits control information that emphasizes the time sequence. The DTI data bus transmits high-volume data that focuses on data throughput and application scenario adaptation.

SBI will evolve towards HTTP 3.0 to deliver low-volume data that can be completed in a single signaling interaction, such as signaling messages on the service interface (generally less than 1304 bytes). SBI will also support the selection of data transmission channels and data transmission protocols.

DTI is dedicated to transferring high-volume data among NFUs, such as sensing data, computing data, AI models, algorithms, etc. According to different data characteristics, DTI can provide extensive and adaptive data access methods (database, block, file, memory, etc.) and data transfer protocols with the assistance of SBI, so as to achieve the data query and processing with high throughput, efficiency, and security. RDMA (Remote Direct Memory Access) technologies [22] for block data migration such as Infiniband, RDMA over Converged Ethernet, the Wide-Area RDMA Protocol, distributed file access technology, and FTP (File Transfer Protocol), for example, can be used for file access and transfer. When the network entities need to transmit data via DTI and need to select the appropriate data transmission protocol, the protocol negotiation can be carried out via SBI. The information elements such as network entity type, data type to be transmitted, requested application layer protocol, and requested transport layer protocol will be exchanged based on HTTP. Then, the protocol stack adaptation and data transmission can be carried out based on DTI and the negotiated protocol type. In this way, flexible and negotiable protocol stacks and efficient customized data transmission among network entities can be achieved.

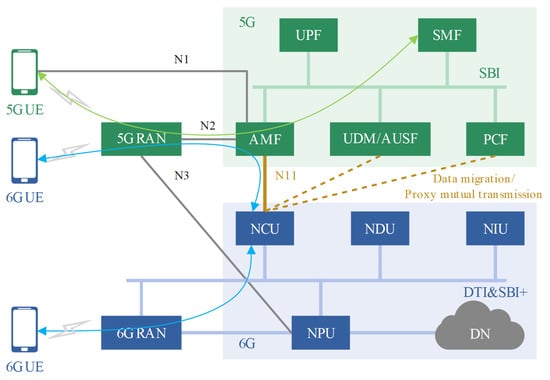

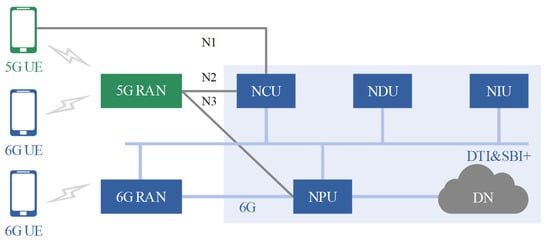

Under the proposed architecture, the transition from 5G to 6G can be carried out in stages. In the early stage of 6G, as shown in Figure 4, 5G UE can access the 5G core network through 5G RAN. Then, 6G UE can indirectly access the 6G core network through the 5G RAN and the 5G core network, which requires data migration or proxy mutual transmission through the interface between the 5G NF and 6G NFU, e.g., N11 between access and mobility management function (AMF) and NCU. Further, 6G UE can also directly access the 6G core network through the 6G RAN. In the long-term stage of 6G, as shown in Figure 5, 5G UE can access the 6G core network through 5G RAN, while 6G UE can access the 6G core network through 5G RAN or 6G RAN. The access adapter of NCU plays an essential role in 5G and 6G interoperation. Moreover, since the abundant functional modules inside each NFU can be developed and implemented by each vendor, only the NFU’s interfaces will be specified and exposed in the long-term stage of 6G. This makes the interoperability of different vendors or operators more convenient and reduces the complexities of network function coordination.

Figure 4.

Interoperation in the early stage of 6G, where 5G entities are shown in green and 6G entities are shown in blue. 5G UE can access the 5G core network through 5G RAN. 6G UE can indirectly access the 6G core network through the 5G RAN and the 5G core network. 6G UE can also directly access the 6G core network through the 6G RAN.

Figure 5.

Unified access in the long-term stage of 6G. 5G UE can access the 6G core network through 5G RAN, while 6G UE can access the 6G core network through 5G RAN or 6G RAN.

4. Network Performance Evaluation and Analysis

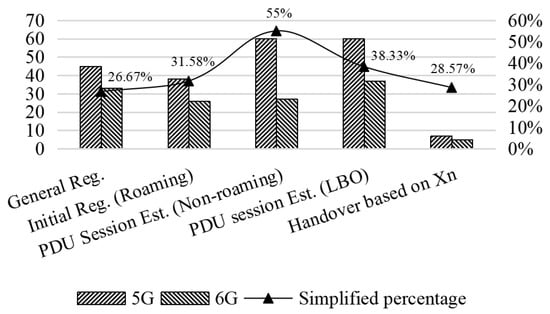

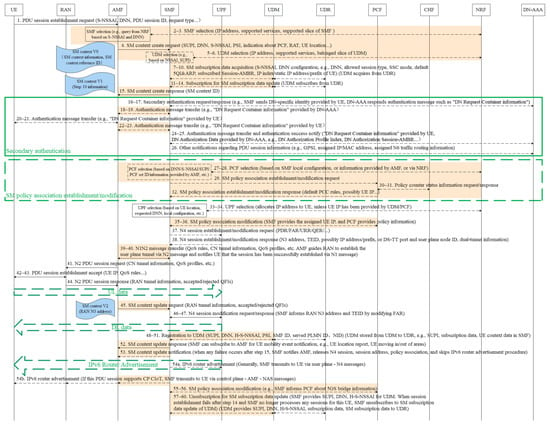

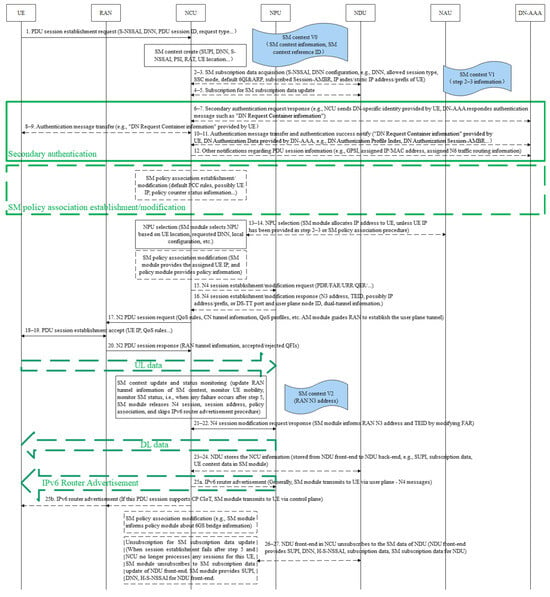

In the DDAA architecture, the functions of numerous coupled NFs are reorganized, and the number of interfaces and the unnecessary redundant data scattered in the NFs are both decreased accordingly. By means of NF aggregation and reorganization, signaling interactions are expected to be significantly reduced, as evaluated in this section. We analyze the UE registration, protocol data unit (PDU) session establishment, and handover procedures in different scenarios as supporting use cases. Note that in order to facilitate the analysis, we tentatively focus on the distinction between the visited and home networks for NFs/NFUs rather than considering the hierarchical deployment of them. The signaling volume of 5G/6G and simplified percentage are shown in Figure 6. It can be seen that the PDU session establishment procedure in the non-roaming case has the highest signaling simplification percentage (55%) due to some NCU internal implementation. Specifically, the simplified signaling in the 5G and 6G procedures is listed in Table 2.

Figure 6.

Simplicity evaluation. The simplified percentage is defined as the ratio of signaling volume difference between 5G and 6G to the signaling volume of 5G. Non-roaming PDU session establishment has the highest simplified percentage due to internal implementation of NCU.

Table 2.

Simplified signaling in the 5G and 6G procedures.

In the general registration procedure, the interaction between authentication server function (AUSF) and unified data management (UDM) for authentication process can be implemented internally by the home-NCU. The UDM selection and home-policy control function (PCF) selection of AMF can be integrated into the selection of home-NCU for authentication. The visited-PCF selection of AMF and the AM/UE policy association establishment process between AMF and PCF can be performed by the visited-NCU.

Figure 7 and Figure 8 present the PDU session establishment procedure. From the exchanged messages and the information elements carried among NFUs, it can be seen that the total number of messages is significantly reduced, and the session context data (such as the information of NFU that serves the UE) to be processed and transmitted by the NFU will be reduced. The dimensions of subscription data and policy data (e.g., user-subscribed services may increase computing service and sensing service, and 6QI may increase computing-QoS and AI-QoS) may be increased, which is brought about by the diversification of 6G services.

Figure 7.

PDU session establishment procedure in the 5G non-roaming scenario. This procedure is based on 3GPP TS 23.502 [23]. The color shading signaling can be omitted with the proposed DDAA in 6G.

Figure 8.

PDU session establishment procedure in the 6G non-roaming scenario. This procedure is based on the proposed DDAA with a three-layer four-plane logical hierarchy. The simplified interactions among NFUs are illustrated.

As detailed in the PDU session establishment procedure of the non-roaming scenario, the session management function (SMF)/PCF/UDM selection can be omitted due to the aggregated session/policy management function of the NCU. The interactions between AMF and SMF are the SM context create/update/status notification; authentication information transfer; and N1 N2 message transfer (where N1 is the interface between UE and the core network, and N2 is the interface between the RAN and the core network).The control plane (CP) internet protocol version 6 (IPv6) router advertisement relies on the NCU internal implementation, as does the SM context update in the Xn-based handover (where Xn is the interface between RANs). However, when the Control Plane CIoT 5GS Optimisation is not supported, CP and user plane (UP) IPv6 router advertisement from NCU to NPU is performed. The interactions between SMF and UDM, such as SM subscription data acquisition, SM subscription data update subscription/unsubscription, and registration of SMF, are omitted due to the aggregation of SMF and UDM. The SM policy association establishment and modification among the SMF, PCF, and charging function (CHF) can also rely on the session/policy management service in the NCU. However, in the case of local breakout (LBO), the UDM selection performed by SMF and the interactions between SMF and UDM cannot be ignored; they should be performed by the interaction between the visited-NCU and home-NCU.

5. Conclusions

Today, the 6G network architecture remains to be converged, and many promising technologies need to be tested and verified. Based on our current understanding and judgment, this article presents preliminary insights into the 6G network architecture, which will be optimized iteratively as academia and industry research advances and technology matures. Adhering to the principles of high cohesion and low coupling, this article proposes DDAA with a three-layer four-plane logical hierarchy. This is achieved by reconstructing and redefining the functionalities of NFs, i.e., reconstructing as NFUs and optimizing the NF boundaries, rather than simply tailoring their functionalities; by designing a dual-bus interface, decoupling data interaction from signaling interaction; and by improving the integration degree of NFs and reducing NF types, interfaces and procedures rather than weakening network and terminal capabilities. The network simplification performance is preliminarily evaluated by comparing the standardized signaling interaction procedures with the potential procedures under the proposed DDAA architecture.

In line with the trends of network simplification and distributed autonomy, end-to-end collaboration between the cross-network-layer and cross-network-domain will be of great significance. It is urgently important that we design a cross-domain cooperation mechanism, cross-protocol information transfer method, and even a cross-industry joint standard design. Currently, the performance evaluation of our proposed architecture and solutions remains in the stage of qualitative analysis, and we still need to perform in-depth research and quantitative analysis. Therefore, in the future, network simplification should be further systematically modeled and comparatively analyzed, considering factors such as message load, failure retransmission probability, deployment location, distribution density, processing delay, and computational overhead of NFUs. In addition, although existing work has proven the potential superiority of emerging transmission protocols (e.g., HTTP 3.0, RDMA, SRv6), improving the efficiency of the data-driven multi-protocol adaptation scheme in the dual-bus architecture compared with the traditional SBI still requires more experimental proof, so as to provide more inspiration for solutions and data support for 6G architecture research and standardization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.G., J.L. and Y.X.; methodology, Q.G.; software, Q.G.; validation, Q.G., J.L. and Y.X.; formal analysis, Q.G.; investigation, Q.G. and Y.X.; resources, Q.G. and J.L.; data curation, Q.G.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.G.; writing—review and editing, Q.G., J.L. and Y.X.; visualization, Q.G.; supervision, Q.G., J.L. and Y.X.; project administration, J.L.; funding acquisition, J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science and Technology Major Project of China (No. 2025ZD1302500).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the 2020 National Key R&D Program “Broadband Communication and New Network” special “6G Network Architecture and Key Technologies” (No. 2020YFB1806700).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 3GPP | The 3rd-Generation Partnership Project |

| 5G | The 5th Generation |

| 6G | The 6th Generation |

| A2A | Agent-to-Agent |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AIaaS | Artificial Intelligence as a Service |

| AD | Atonomous Domains |

| AMF | Access and mobility Management Function |

| AUSF | Authentication Server Function |

| CHF | Charging Function |

| CP | Control Plane |

| CPaaS | Computing Power as a Service |

| CPU | Central Processing Unit |

| DDAA | Data-driven Distributed Autonomous Architecture |

| DLT | Distributed Ledger Technology |

| DTI | Data Transmission Interface |

| DUE | Digital Twin User Equipment |

| FPGA | Field-Programmable Gate Array |

| FTP | File Transfer Protocol |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| HSBA | Holistic Service-based Architecture |

| HTTP | Hypertext Transport Protocol |

| IPv6 | Internet Protocol Version 6 |

| ITU-R | International Telecommunication Union-Radiocommunication |

| LBO | Local Breakout |

| MAPPO | Multi-Agent Proximal Policy Optimization |

| MCP | Model Context Protocol |

| NAU | Network Assistance Unit |

| NCU | Network Control Unit |

| NDU | Network Data Unit |

| NF | Network Function |

| NFU | Network Function Unit |

| NIU | Network Intelligence Unit |

| NPU | Network Packet Unit |

| NWDAF | Network Data Analytics Function |

| PCF | Policy Control Function |

| PDU | Protocol Data Unit |

| PQC | Post-Quantum Cryptography |

| PUE | Physical User Equipment |

| OA | Observation Abstraction |

| QoE | Quality of Experience |

| QoS | Quality of Service |

| RAN | Radio Access Network |

| RDMA | Remote Direct Memory Access |

| SaaS | Sensing as a Service |

| SBI | Service-based Interface |

| SLA | Service Level Agreement |

| SMF | Session Management Function |

| SRv6 | Segment Routing over Internet Protocol Version 6 |

| UDM | Unified Data Management |

| UE | User Equipment |

| UP | User Plane |

References

- Wang, C.-X.; You, X.; Gao, X.; Zhu, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, H.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Haas, H.; et al. On the Road to 6G: Visions, Requirements, Key Technologies, and Testbeds. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2023, 25, 905–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Telecommunication Union (ITU). Framework and Overall Objectives of the Future Development of IMT for 2030 and Beyond, ITU-R Draft New Recommendation; International Telecommunication Union (ITU): Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Demirhan, U.; Alkhateeb, A. Integrated Sensing and Communication for 6G: Ten Key Machine Learning Roles. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2023, 61, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liang, Y.C.; Sun, S.; Kang, S.; Cheng, W.; Peng, M. Vision, Requirements, and Technology Trend of 6G: How to Tackle the Challenges of System Coverage, Capacity, User Data-Rate and Movement Speed. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2020, 27, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordani, M.; Polese, M.; Mezzavilla, M.; Rangan, S.; Zorzi, M. Toward 6G Networks: Use Cases and Technologies. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2020, 58, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letaief, K.B.; Chen, W.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.J.A. The Roadmap to 6G: AI Empowered Wireless Networks. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2019, 57, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.D.; Wang, X.Y.; Lu, L.; Shi, N.X.; Liu, C.; Zhang, T.; Sun, T. 6G Architecture Design: From Overall, Logical and Networking Perspective. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2023, 61, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corici, M.; Troudt, E.; Chakraborty, P.; Magedanz, T. An Ultra-Flexible Software Architecture Concept for 6G Core Networks. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 4th 5G World Forum (5GWF), Montreal, QC, Canada, 13–15 October 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corici, M.; Troudt, E.; Magedanz, T.; Schotten, H. Organic 6G Networks: Decomplexification of Software-based Core Networks. In Proceedings of the 2022 Joint European Conference on Networks and Communications & 6G Summit (EuCNC/6G Summit), Grenoble, France, 7–10 June 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Li, P.; Li, J. Discussion on 6G Network Architecture Based on Evolution. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Information Processing and Network Provisioning (ICIPNP), Beijing, China, 15–16 September 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogra, A.; Jha, R.K.; Jain, S. A Survey on Beyond 5G Network With the Advent of 6G: Architecture and Emerging Technologies. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 67512–67547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkonis, P.K.; Giannopoulos, A.; Nomikos, N.; Trakadas, P.; Sarakis, L.; Masip-Bruin, X. A Survey on Architectural Approaches for 6G Networks: Implementation Challenges, Current Trends, and Future Directions. Telecom 2025, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.; Wu, J.; Tong, W.; Zhu, P.; Chen, Y. 6G Network Architecture Vision. In Proceedings of the 2021 Joint European Conference on Networks and Communications & 6G Summit (EuCNC/6G Summit), Porto, Portugal, 8–11 June 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, L.U.; Saad, W.; Niyato, D.; Han, Z.; Hong, C.S. Digital-Twin-Enabled 6G: Vision, Architectural Trends, and Future Directions. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2022, 60, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, W.; Bennis, M.; Chen, M. A Vision of 6G Wireless Systems: Applications, Trends, Technologies, and Open Research Problems. IEEE Netw. 2020, 34, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Mei, J.; Cui, S.; Wang, C.-X.; Shen, X.S. Realizing 6G: The Operational Goals, Enabling Technologies of Future Networks, and Value-Oriented Intelligent Multi-Dimensional Multiple Access. IEEE Netw. 2023, 37, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karam, G.M.; Gruber, M.; Adam, I.; Boutigny, F.; Miche, Y.; Mukherjee, S. The Evolution of Networks and Management in a 6G World: An Inventor’s View. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2022, 19, 5395–5407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Liu, C.; Zhang, C.; Hu, Z.; Lin, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Liu, X.; Chen, J. Architecture for Self-Evolution of 6G Core Network Based on Intelligent Decision Making. Electronics 2023, 12, 3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tupe, V.; Thube, S. Demonstrating Multi-Agent Collaboration via Agent-to-Agent and Model Context Protocols: An IT Incident Response Case Study. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Service-Oriented System Engineering (SOSE), Tucson, AZ, USA, 21–24 July 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miuccio, L.; Riolo, S.; Samarakoon, S.; Panno, D.; Bennis, M. Learning Generalized Wireless MAC Communication Protocols via Abstraction. In Proceedings of the GLOBECOM 2022—2022 IEEE Global Communications Conference, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 4–8 December 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miuccio, L.; Riolo, S.; Samarakoon, S.; Bennis, M.; Panno, D. On Learning Generalized Wireless MAC Communication Protocols via a Feasible Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning Framework. IEEE Trans. Mach. Learn. Commun. Netw. 2024, 2, 298–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Zhao, M.; Xu, Y.; Liu, C. 6G Distributed Autonomous Core Network with Proxy Architecture and HTTP/3 Transport. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Future Communications and Networks (FCN), Valletta, Malta, 18–22 November 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 3GPP TS 23.502: Procedures for the 5G System (5GS), Stage 2, Release 19, Version 19.5.0. September 2025. Available online: https://portal.3gpp.org/desktopmodules/Specifications/SpecificationDetails.aspx?specificationId=3145 (accessed on 24 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.