1. Introduction

Recent large-scale crowd disasters, such as the Itaewon tragedy in Korea, highlight the urgent necessity of proactive crowd behavior analysis and advanced surveillance solutions in modern cities [

1,

2]. Comparable accidents have been reported globally—for instance, the 2015 Shanghai Bund stampede in China, which caused 36 deaths [

3]; the 2013 Allahabad Kumbh Mela incident in India, leaving more than 36 fatalities and over 100 injuries [

4]; and multiple Hajj-related stampedes in the Middle East, with hundreds of victims due to uncontrolled surges [

5]. These examples illustrate the worldwide demand for intelligent monitoring systems that can provide real-time detection, timely alerts, and early intervention to mitigate casualties [

6].

Detecting anomalies in crowd dynamics requires the capability to capture complex temporal dependencies and to identify irregular behavioral patterns across heterogeneous inputs such as CCTV footage and mobility sensor data [

7,

8,

9]. Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) [

10,

11], particularly Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) architectures, have shown effectiveness in time-series analysis tasks, including activity recognition [

12], traffic flow prediction [

13], and video-based anomaly detection [

14]. Nevertheless, traditional LSTM models face challenges in retaining information over long horizons, especially in highly dynamic and disordered urban environments. To overcome these drawbacks, researchers have introduced improved architectures. ConvLSTM [

15], for example, incorporates convolutional operations to learn spatial-temporal correlations in sequential data, enhancing its applicability to video analysis. More recently, Transformer models [

16] with self-attention mechanisms have achieved superior performance in sequence learning; however, they demand substantial computational resources and large datasets, and their interpretability in safety-critical applications is still debatable.

At the same time, advances in neuroscience-inspired computing have introduced models such as Episodic Memory Networks [

17], Memory-Augmented Neural Networks [

18], and Neural Turing Machines [

7,

19], which are inspired by hippocampal functions in the human brain [

20,

21]. These models demonstrate the utility of episodic memory for capturing and recalling contextual sequences [

22]. Despite these developments, the practical adoption of hippocampal-inspired memory modules for real-world surveillance of crowds remains scarce [

23].

Existing approaches still suffer from several limitations:

Labeled anomaly datasets, which hampers model generalization.

High infrastructure costs, particularly when deploying multi-sensor or multi-camera systems.

Limited capability for real-time deployment due to the computational overhead of state-of-the-art methods.

Lack of interpretability, which weakens user trust in mission-critical scenarios.

To bridge these gaps, we introduce Hippocampal-Inspired Memory-Enhanced LSTM (HiMeLSTM). HiMeLSTM strengthens the temporal modeling power of LSTMs with a hippocampus-inspired Episodic Memory Unit (EMU) that can store and retrieve contextual episodes over extended durations. By operating on zone-level descriptors extracted from raw CCTV footage, HiMeLSTM is able to model both short-term motion patterns and long-range contextual dependencies that are critical for distinguishing between benign crowd formations and genuinely dangerous behaviors.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

Memory-Augmented Recurrent Backbone: We propose HiMeLSTM, a hippocampal-inspired memory-enhanced LSTM that integrates an Episodic Memory Unit (EMU) with an LSTM encoder. The EMU stores compact episode representations with spatial and temporal context, enabling long-term recall that goes beyond standard LSTM and ConvLSTM architectures.

Zone-Level Spatial Context Encoding: We introduce a zone-level spatial mapping module that partitions each scene into semantically meaningful regions and aggregates CNN features into zone descriptors. This design provides structured spatial context for crowd behavior and facilitates interpretable analysis at the zone level.

Performance and Interpretability: Experiments on benchmark datasets built on the HiMeLSTM backbone, consistently outperforms conventional LSTM, ConvLSTM, and Transformer baselines in terms of accuracy, anomaly detection rate, and F1-score. At the same time, the EMU and its attention weights offer a transparent mechanism for identifying which past episodes contributed to each decision.

Real-Time Feasibility for CCTV-Based Surveillance: The overall architecture is lightweight and computationally efficient, relying solely on standard visual data with zone-level mapping. This eliminates the need for expensive multi-sensor infrastructure and makes the framework suitable for real-time deployment in existing CCTV-based urban surveillance systems.

3. Proposed Method

HiMeLSTM denotes the end-to-end crowd anomaly detection pipeline, whereas refers to the core Hippocampal-inspired Memory-enhanced LSTM backbone that couples an LSTM encoder with the Episodic Memory Unit (EMU). At a high level, HiMeLSTM maps an input CCTV video sequence to a sequence of anomaly scores as follows: (i) a CNN encoder extracts appearance- and motion-sensitive feature maps from each frame; (ii) a zone-level spatial mapping module aggregates these feature maps into descriptors for manually defined zones; (iii) the sequence of zone descriptors is processed by the HiMeLSTM backbone, where the LSTM captures short-term temporal dynamics and the EMU stores and retrieves long-term episodic memories; and (iv) an anomaly detection head combines the current hidden state with the retrieved memory context to produce a scalar anomaly score for each time step. An alert is raised whenever the anomaly score exceeds a learned threshold.

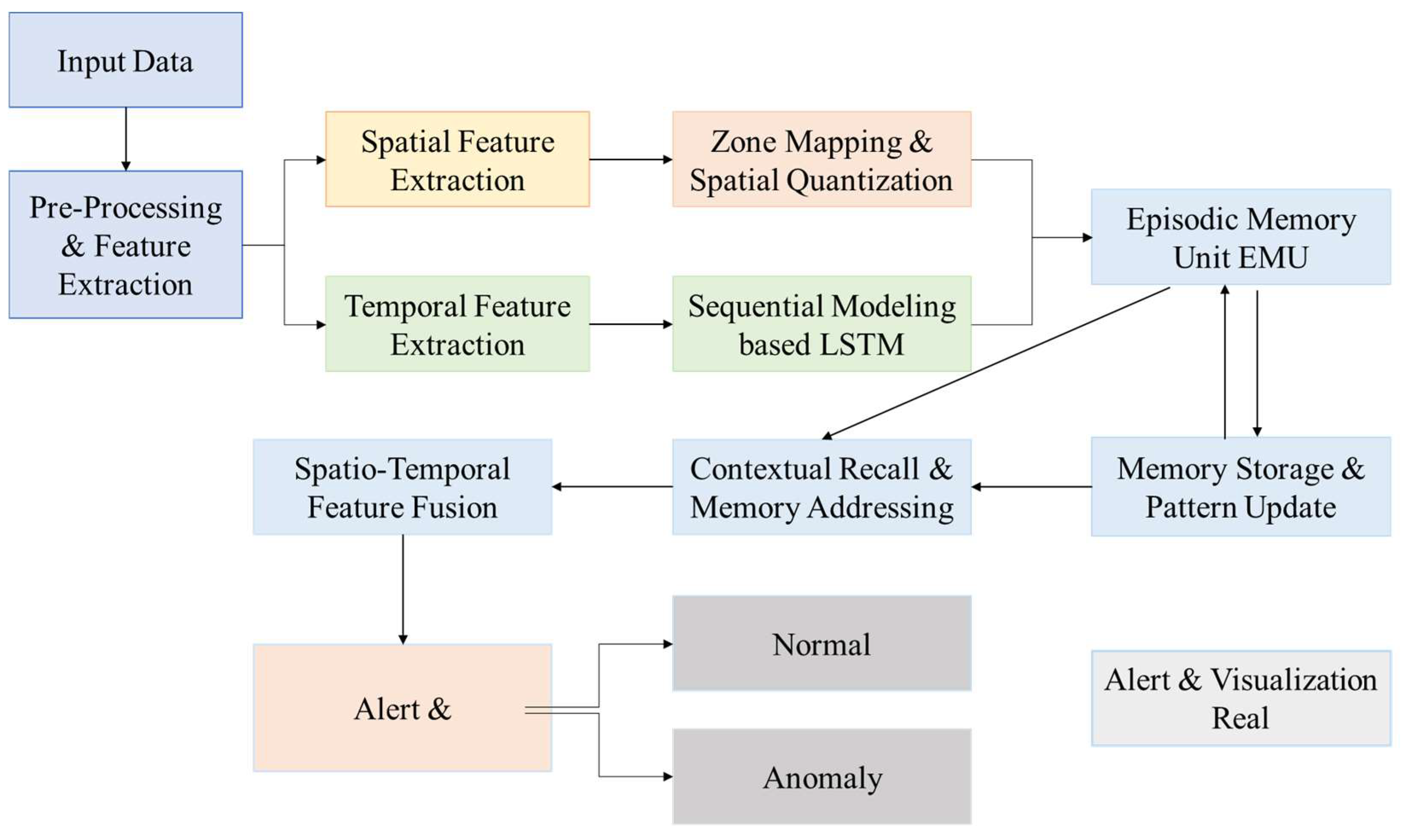

Figure 1 illustrates the overall architecture and data flow. Given an input CCTV video stream, each frame is first processed by a CNN-based encoder to extract appearance and motion-sensitive feature maps. These feature maps are then partitioned into a set of manually defined spatial pooled into compact zone-level descriptors. The resulting sequence of zone descriptors is fed into the HiMeLSTM backbone, where an LSTM encoder models short-term temporal dependencies and the EMU maintains a compact set of long-term episodic memories summarizing past crowd behaviors. At each time step, the current hidden state interacts with the EMU through an attention-based retrieval mechanism that retrieves the most relevant past episodes and produces a contextualized representation. This representation is finally mapped to an anomaly score, and an alarm is raised when the score exceeds a learned threshold, triggering the event classification and alerting module. Because each memory slot stores both the temporal index and zone-level context, the EMU also provides a natural handle for interpretability: operators can inspect which past episodes when were most influential in the decision.

3.1. Input Data Modalities

Visual Data: Raw CCTV video (up to 4K resolution) is processed with CNN-based detectors to extract human-centric features such as bounding boxes, posture descriptors, and motion trajectories. Behavioral indicators such as falling, loitering, sudden running, or crowd surges are embedded into the feature vectors.

Spatial Context: Each scene is subdivided into manually pre-defined zones (entrances, exits, bottlenecks). Events are thus contextualized with respect to location, enabling localized anomaly interpretation.

3.2. CNN Encoder and Zone Mapper

The CNN encoder is responsible for extracting low- and mid-level visual features from each input frame. In our implementation, we adopt a lightweight ResNet-style backbone truncated before the global pooling and classification layers. Concretely, each input RGB frame is first resized to a fixed resolution and passed through a stack of convolutional blocks, where each block consists of a 3 × 3 convolution, batch normalization, and ReLU activation, with occasional stride-2 convolutions for spatial downsampling. The final convolutional stage produces a feature map with C channels and a reduced spatial resolution.

where

is the video frame at time

, and

represents extracted features such as posture orientation and movement direction.

The Zone Mapper then projects these features into predefined zones:

The Zone Mapper then projects these feature maps into a set of predefined spatial zones. The scene is partitioned into semantic or grid-based regions.

where

denotes the spatial partitioning of the frame. This zone-wise representation enables crowd dynamics analysis and interpretability at the level of individual regions without requiring external spatial modeling platforms.

3.3. LSTM Temporal Encoder

The zone-level feature vectors are passed to the LSTM encoder to capture temporal dynamics:

where

is the hidden state and

is the cell state at time

. Each hidden state

becomes a temporal key that links current crowd behavior with the EMU for contextual storage and retrieval.

3.4. Episodic Memory Unit (EMU)

The EMU simulates the hippocampal role in episodic memory formation and recall.

Memory Slots: The EMU maintains a finite set of M memory slots , where each slot stores a compressed tuple representing the hidden state, zone descriptor, and time index of a past episode. Unless otherwise stated, we set M = 256 in all experiments, which we found to provide a good balance between contextual capacity and computational cost.

Memory Encoding: A new episode

is added if the temporal variation exceeds a threshold

:

here,

and

denote the current and previous LSTM hidden states, respectively, and

is a scalar threshold that controls how much temporal change must be observed before a new episode is written into memory.

Memory Retrieval: Attention-based similarity scoring retrieves relevant episodes, given the current hidden state

, the EMU retrieves relevant past episodes through attention-based similarity scoring. We first compute a similarity score

between

and each memory slot

, and then normalize these scores via a softmax to obtain attention weights,

where

can be cosine or Euclidean similarity.

Contextual Recall: contextual embedding is computed as a weighted sum over memory slots as:

which aggregates information from the most relevant past episodes. In this expression,

is the attention weight assigned to memory slot

, and each

is a stored episodic memory vector. Their weighted sum

represents the contextual recall that aggregates information from the most relevant past episodes. The recalled vector

is then combined with the current hidden state ht and passed to the anomaly detection head. In the revised

Figure 1, we explicitly depict these EMU operations—memory slot updates, similarity computation, attention weighting, and contextual recall—to make the internal mechanism more transparent.

3.5. Anomaly Detection Module

The anomaly detection module transforms the internal representation of HiMeLSTM into a scalar anomaly score for each time step. Intuitively, this score should be high when the current crowd behavior deviates significantly from previously observed normal episodes stored in the EMU.

We compute an anomaly score by comparing the current hidden state

with the recalled context

from memory. In our implementation, the concatenated vector (

) is passed through a small fully connected layer to produce a scalar score

. If

, where

is a learned threshold, the corresponding frame is flagged as anomalous.

Typical anomalies include sudden increases in crowd density (stampede-like patterns), irregular movement flows such as counter-directional motion, and unusual events like falling or loitering in restricted zones.

3.6. Architectural Details and Output Dimensions

To facilitate reproducibility and clarify the information flow in HiMeLSTM, we summarize here the main tensor shapes produced by each block in

Figure 1 using symbolic notation.

Let each RGB input frame be denoted by

where

H and

W are the image height and width, respectively. The CNN encoder transforms

into a feature map

where

C denotes the number of channels and

H′ ×

W′ is the spatial resolution of the feature map.

The scene is partitioned into

K non-overlapping spatial zones (e.g., a regular grid or semantically defined regions). For each zone, we perform spatial pooling over the corresponding region in

, yielding a set of zone descriptors:

where each

is a

D-dimensional feature vector summarizing the local crowd dynamics in zone

at time

. The sequence of zone descriptors is then flattened and passed to the LSTM encoder:

where

denotes the dimensionality of the hidden and cell states. The Episodic Memory Unit(EMU) maintains a set of

M memory slots

where each slot stores a tuple

in compressed form. During retrieval, the similarity between the current hidden state

and each memory slot is used to compute attention weights

, which in turn yield a contextual recall

As in

Section 3.4,

denotes the attention weight for the

i-th memory slot and

is the corresponding memory vector, so that recalled representation

is a weighted combination of past episodic memories consistent with Equation (6).

The anomaly detection head receives the concatenated representation

and outputs a scalar anomaly score

where

W and

b are learnable parameters and

denotes a suitable activation function. These symbolic shapes are reflected in

Figure 1 and ensure that the output dimensions of each block are explicitly defined. Each input frame

(1920

1080) is processed by a yolo backbone, yielding features of size 2048

7

7. The Zone Mapper projects these into

, spatial zones, outputting

.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Datasets

We evaluate HiMeLSTM on three benchmark datasets for crowd anomaly detection: UCF-Crime [

32], ShanghaiTech Campus [

33], and our in-house CrowdSurge-1K [

34] dataset.

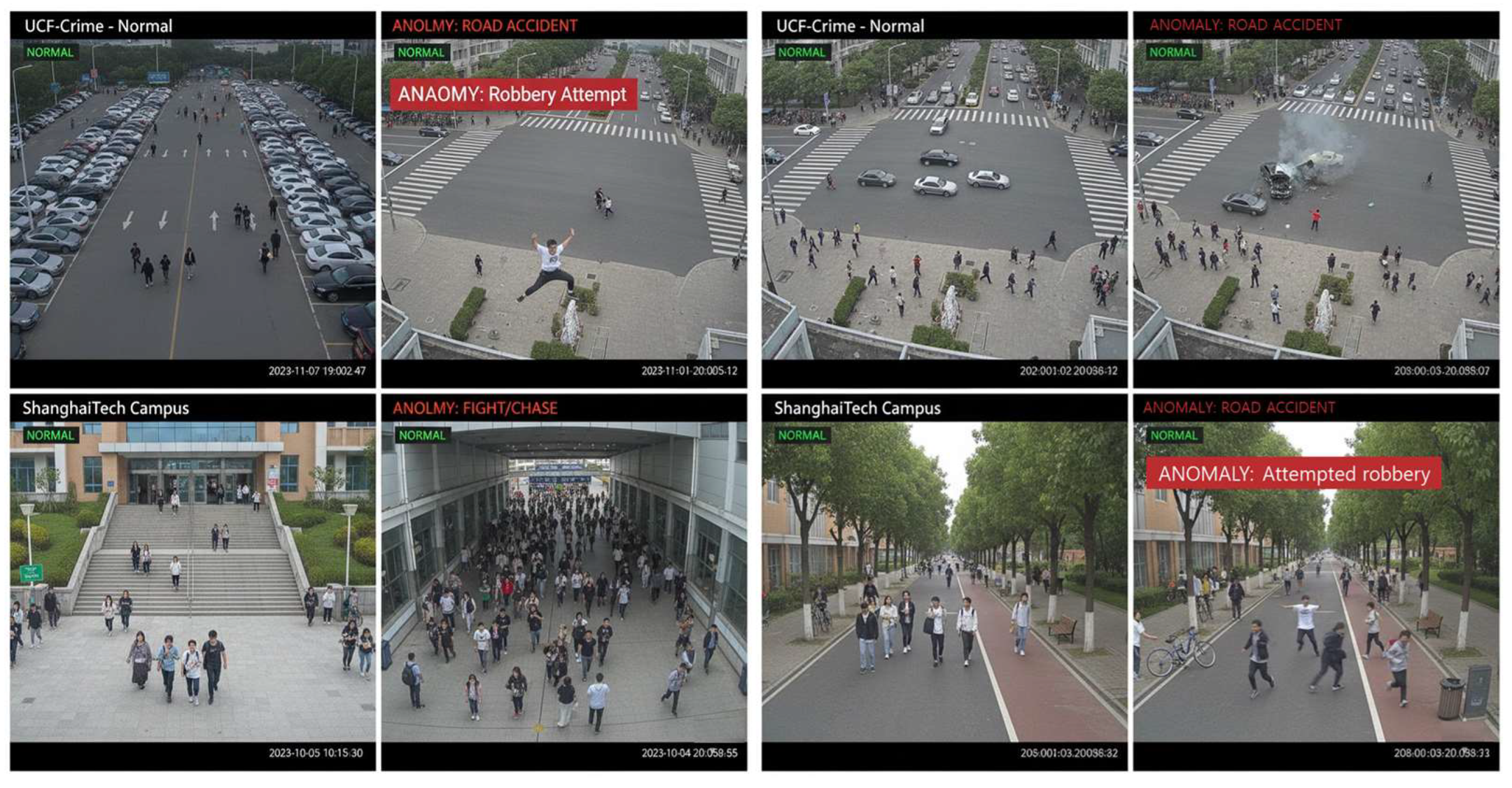

UCF-Crime (samples, as shown in the left panels of

Figure 2) is a large-scale collection of real-world surveillance videos that has become a standard benchmark for video anomaly detection. It contains 1900 long, untrimmed surveillance videos (approximately 128 h in total) captured by fixed CCTV cameras in diverse outdoor and indoor environments such as streets, parking lots, and shops. The dataset covers 13 types of anomalous events, including fighting, road accidents, burglary, robbery, shooting, shoplifting, and other criminal or dangerous activities, as well as normal scenes. We follow the standard semi-supervised protocol introduced by Sultani et al.: only normal videos are used for training, while the test set contains both normal and anomalous videos with frame-level annotations. In this setting, the model must learn normal patterns and detect anomalies in previously unseen test videos.

The ShanghaiTech Campus (samples, as shown in the right panels of

Figure 2) dataset focuses on anomaly detection in a university campus environment. It consists of 330 normal training videos and 107 test videos captured by multiple static cameras covering campus walkways, building entrances, and open squares at a resolution of 480 × 856. The test set includes both normal activities and a variety of anomalous events such as bicycles or motorbikes entering pedestrian areas, people fighting or chasing each other, jumping, and other irregular behaviors. Each anomalous segment is annotated at the frame level. We strictly follow the official train/test split and evaluation protocol, using only normal training videos for model fitting and computing all metrics on the test set.

CrowdSurge-1K (samples, as shown in

Figure 3) is an in-house dataset designed to specifically capture high-risk crowd situations such as sudden density surges near exits, bottlenecks, and confined spaces. It contains 1000 clips (typically 5–20 s each) recorded from fixed surveillance viewpoints in urban public areas, including transportation hubs, stadium surroundings, and pedestrian streets. The dataset includes both normal crowd flows and a diverse set of surge-like anomalies, such as rapid inflow toward a narrow passage, stagnation followed by sudden movement, and disordered motion patterns that may precede crush or stampede events. We split CrowdSurge-1K into training, validation, and test sets with a ratio of 6:1:3, ensuring that scenes do not overlap between splits to test cross-scene generalization.

In all experiments, input frames are resized to a fixed spatial resolution and sampled at a common frame rate so that temporal sampling is comparable across datasets. The official ground-truth annotations provided with each dataset are used for both training supervision and quantitative evaluation.

4.2. Implementation and Evaluation Metrics

Implementation Details. All models were implemented in Python 3.12 using the PyTorch 2.2.0 framework and trained on a workstation equipped with a single NVIDIA RTX-class GPU, an 8-core CPU, and 32 GB of RAM, running a Linux operating system. Unless otherwise stated, input frames were resized to a fixed spatial resolution and sampled at a constant frame rate. We trained HiMeLSTM for 50 epochs using the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 1 × 10−4, a batch size of 8 sequences, and a sequence length of 32 frames. The EMU memory size was set to M = 256 slots by default, and early stopping was applied based on validation performance. The model size and FLOPs reported in the efficiency table reflect this final trained configuration.

Evaluation Metrics. To quantitatively assess the performance of HiMeLSTM and the baselines, we employ standard classification and detection metrics commonly used in video anomaly detection: accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, Receiver Operating Characteristic Area Under the Curve (ROC-AUC), Precision–Recall Area Under the Curve (PR-AUC), and Anomaly Detection Rate (ADR). If

,

,

, and

denote the numbers of true positives, false positives, true negatives, and false negatives, respectively, at the chosen decision threshold, accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score are defined as

ROC-AUC and PR-AUC are obtained by varying the decision threshold over the full range of anomaly scores and computing the area under the corresponding ROC and precision–recall curves, respectively.

The Anomaly Detection Rate (

) focuses specifically on the correct detection of anomalous events. It is defined as

In our experiments, “” correspond to [clips/frames], depending on the granularity of the dataset annotations. We compute ADR by comparing the predicted anomaly labels with the ground-truth labels for all anomalous samples in the test set. This metric directly reflects the model’s sensitivity to true anomalies and complements the threshold-independent ROC-AUC and PR-AUC scores.

4.3. Detection Performance

The primary objective of any anomaly detection system is to achieve high accuracy with a balanced sensitivity to positive cases. As quantitatively summarized in

Table 1, HiMeLSTM demonstrates superior performance across all key metrics, establishing a new state-of-the-art for the task of crowd anomaly detection.

As shown in

Table 1, conventional LSTM-based models focus on sequential temporal modeling and are effective for capturing short-term dependencies, but they suffer from weak long-term memory retention and limited spatial awareness. ConvLSTM models extend LSTMs by incorporating convolutional operations to model spatiotemporal patterns in video data; however, this improvement comes at the cost of increased computational complexity and difficulty in capturing global contextual information. Transformer-based approaches, leveraging self-attention mechanisms, excel at long-range dependency modeling and often achieve high detection accuracy, but they typically require large-scale datasets, incur high computational overhead, and offer limited interpretability in safety-critical applications.

Neuroscience-inspired architectures, such as Neural Turing Machines (NTM), Memory-Augmented Neural Networks (MANN), and other episodic memory-based models, introduce external memory components that enable contextual retention and biologically plausible reasoning. Despite their conceptual advantages, these methods often involve complex training procedures and have seen limited adoption in real-world crowd surveillance scenarios.

In contrast, the proposed HiMeLSTM integrates an Episodic Memory Unit (EMU) with an LSTM backbone, explicitly addressing the shortcomings of existing approaches. As summarized in

Table 1, HiMeLSTM combines strong long-term memory retention with interpretable episodic recall while remaining lightweight enough for real-time deployment. Although it requires careful zone definition and further validation across diverse environments, its design offers a balanced trade-off between performance, interpretability, and computational efficiency.

Quantitatively, HiMeLSTM improves the Anomaly Detection Rate (ADR) by 4.3% over Vanilla LSTM, 2.9% over ConvLSTM, and 4.3% over the Transformer baseline. This performance gain can be directly attributed to the episodic memory mechanism, which enables the model to retrieve and leverage relevant contextual patterns from distant past events. Such capability is particularly important in crowd scenarios, where anomalous behavior is often preceded by subtle and temporally dispersed cues. Furthermore, HiMeLSTM achieves the highest F1-score of 0.89, reflecting an effective balance between precision and recall and underscoring its suitability for real-world surveillance and early-warning applications.

4.4. Computational Efficiency

For real-world deployment, especially on edge devices or systems requiring real-time analysis, computational efficiency is as important as accuracy. A model must be not only accurate but also fast and lightweight.

Table 2 shows the quantitative performance comparison of different crowd anomaly detection models in terms of Accuracy, Anomaly Detection Rate (ADR), and F1-score. Conventional sequential models such as Vanilla LSTM and ConvLSTM show reasonable performance but suffer from limited sensitivity to complex or long-term anomalies. Transformer-based models achieve higher accuracy and ADR by leveraging global attention, yet the improvement is relatively modest considering their higher computational cost.

Reconstruction-based approaches, including MemAE and ST-AE, further improve detection performance by learning compact representations of normal behavior, resulting in higher ADR and F1-scores than recurrent baselines. However, these methods still fall short in capturing long-range temporal dependencies critical for early anomaly detection.

The proposed HiMeLSTM consistently outperforms all compared baselines across all evaluation metrics, achieving the highest accuracy (93.5%), ADR (89.6%), and F1-score (0.89). This performance gain demonstrates the effectiveness of the hippocampal-inspired Episodic Memory Unit in preserving long-term contextual information while maintaining robustness to diverse anomaly patterns. Overall, the results indicate that HiMeLSTM provides a superior balance between detection accuracy and practical deployability for real-time crowd surveillance systems.

Table 3 shows a comparison of the computational efficiency of different crowd anomaly detection models in terms of training cost (GPU-hours), model size, floating-point operations (FLOPs), and inference speed measured in frames per second (FPS) at 1080p resolution. The Vanilla LSTM model exhibits the lowest computational cost and highest inference speed; however, this efficiency comes at the expense of limited detection performance, as shown in the accuracy results.

The Transformer-based model incurs the highest computational overhead, with substantially larger model size, FLOPs, and training cost, resulting in the lowest real-time inference speed. Such characteristics make it less suitable for deployment in resource-constrained or real-time surveillance environments.

The proposed model achieves a favorable trade-off between efficiency and performance. While slightly more computationally demanding than the Vanilla LSTM, it significantly reduces the overhead compared to the Transformer model and maintains a high inference speed of 38.4 FPS. These results indicate that the proposed approach is well suited for real-time crowd anomaly detection on GPU-equipped edge devices, offering both strong detection capability and practical computational efficiency.

These results confirm that HiMeLSTM achieves superior accuracy with moderate computational cost, making it suitable for real-time deployment on resource-constrained devices.

4.5. ROC and Precision-Recall Analysis

To evaluate model robustness beyond fixed-threshold metrics, we analyzed the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) and Precision-Recall (PR) curves. These analyses assess performance across all possible classification thresholds.

As shown in

Figure 4, HiMeLSTM consistently dominates the other methods across the entire operating range. Specifically, HiMeLSTM achieves the highest area under the curve in both evaluations, with a ROC-AUC of 0.95 compared to 0.91 for the Transformer, 0.89 for ConvLSTM, and 0.87 for LSTM. Similarly, in the PR analysis, HiMeLSTM attains a PR-AUC of 0.93, outperforming the Transformer (0.89), ConvLSTM (0.86), and LSTM (0.83).

The superior ROC-AUC indicates that HiMeLSTM has a strong overall ability to discriminate between normal and anomalous crowd behaviors, regardless of the decision threshold. More importantly, the consistently higher PR curve demonstrates that HiMeLSTM maintains high precision even at high recall levels, meaning that it can detect a large proportion of true anomalies while keeping false alarms low. This behavior reflects the benefit of the episodic memory mechanism, which enables robust contextual reasoning over long temporal horizons. Overall, the ROC and PR analyses confirm that HiMeLSTM provides stable and reliable anomaly detection performance under varying operational conditions, making it well suited for real-world crowd monitoring applications.

4.6. Ablation Study

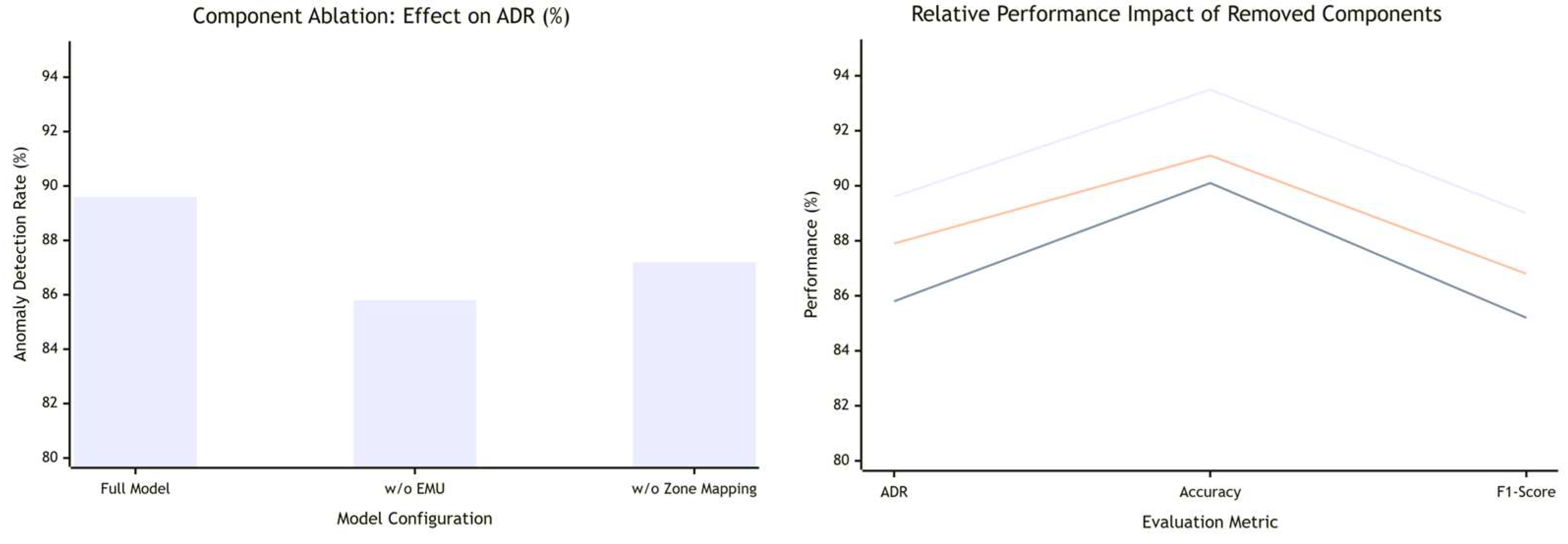

To deconstruct the contribution of each architectural component in HiMeLSTM, we conducted a series of ablation experiments. The results, summarized in

Figure 5, validate our design choices.

- (1)

Without Episodic Memory Unit (EMU): Removing the core EMU module led to a significant drop of 3.8% in ADR. This result directly confirms the hypothesis that contextual recall beyond immediate sequences is vital for accurate anomaly detection. The model without EMU degenerates to a more standard architecture, losing its ability to link current observations with past, similar contexts.

- (2)

Without Zone Mapping: Eliminating the zone-wise spatial mapping caused a 2.4% decrease in overall accuracy. This degradation was most pronounced in areas with high crowd density or overlapping trajectories. The result underscores that zone mapping is not merely for interpretability; it provides a structured spatial prior that helps the model disambiguate local patterns, thereby improving feature learning and detection accuracy.

- (3)

Varying Memory Slot Size: We investigated the impact of the EMU’s memory capacity. The experiment revealed a clear trade-off: an insufficient number of slots (128) led to information loss and poor performance as critical past contexts could not be stored, while an excessive number (512) resulted in increased computational overhead and potential overfitting to noise. An optimal balance was found at 256 memory slots, which provided sufficient capacity for context retention without undue computational cost.

In

Figure 5, the left sub-figure compares configurations with and without the Episodic Memory Unit (EMU) and zone-level mapping. The right sub-figure shows how accuracy, ADR, and F1-score change as the number of memory slots varies; the three broken lines in the plot correspond to accuracy, ADR, and F1-score, respectively, as indicated in the legend. The three curves represent different ablation settings:

Top line: Full model (HiMeLSTM with EMU and zone mapping).

Middle line: HiMeLSTM without zone mapping.

Bottom line: HiMeLSTM without the Episodic Memory Unit (EMU).

The results show that removing EMU leads to the largest performance degradation across ADR, Accuracy, and F1-score, while removing zone mapping causes a moderate but consistent decline, confirming the importance of both components.

As summarized in

Table 4, removing the EMU leads to a noticeable drop in anomaly detection performance, confirming the importance of long-term episodic recall. Eliminating the zone mapping mainly affects accuracy in dense or overlapping crowd regions, highlighting the role of structured spatial context. Varying the memory capacity reveals that too few slots cause information loss, while too many slots increase computational overhead without clear benefits; 256 slots offer a favorable balance between performance and efficiency.

4.7. Error Case Analysis

Despite its strong performance, HiMeLSTM is not infallible. A qualitative analysis of failure cases provides valuable insights into its limitations and outlines promising avenues for future research. The primary error types are categorized and illustrated in

Figure 6.

Error Analysis:

- (1)

False Positives in Structured Crowds: The model occasionally generates false alarms in scenarios involving dense but orderly queues, such as those at ticket counters or security checkpoints. This occurs because the model relies on high crowd density as a key anomaly lacks the finer-grained semantic understanding to differentiate between structured (normal) and unstructured (anomalous) crowding patterns.

- (2)

False Negatives in Subtle or Sparse Events: Conversely, certain rare and subtle anomalies are occasionally missed. These include events like fights within a small group in a sparse zone or an individual’s abrupt change in direction. Such events have a less pronounced effect on global crowd motion patterns and can be overshadowed by dominant, normal activities, making them challenging to detect.

4.8. Interpretability and Memory Visualization

One of the main motivations behind introducing the hippocampal-inspired Episodic Memory Unit (EMU) was to improve the interpretability of crowd anomaly detection. Because each memory slot stores a compact representation of a past episode, together with its spatial context and temporal index, the attention weights used during retrieval can be directly inspected to understand which past events informed the current decision.

For qualitatively selected test cases, we visualize (i) the attention distribution over memory slots, and (ii) the corresponding spatial zones associated with the top-ranked episodes. In typical crowding anomalies, such as sudden density surges near exits, HiMeLSTM assigns high attention to past episodes where local density gradually increased in the same or neighboring zones. This behavior indicates that the model is not reacting to an isolated rather comparing the current pattern to a sequence of contextually similar episodes stored in memory.

In scenarios that lead to false positives—e.g., dense but orderly queues at ticket counters—the attention distribution tends to be more diffuse and often focuses on episodes that share high density but differ in motion regularity. This suggests that the current implementation still overemphasizes local density when distinguishing between structured and unstructured crowding. Conversely, false negatives, such as subtle conflicts within a small group in a sparse region, often exhibit weak or inconsistent attention to truly anomalous episodes, reflecting the fact that their impact on global motion patterns is limited.

Overall, these visualizations demonstrate that the EMU provides a meaningful and human-interpretable mechanism for tracing decisions back to specific past episodes and zones. This property is particularly valuable in safety-critical settings, where operators require not only accurate alarms but also transparent explanations of why a given event has been classified as anomalous.

5. Conclusions

This study introduces HiMeLSTM, a novel and lightweight neural architecture designed for robust and efficient crowd anomaly detection. The model addresses a critical gap in real-world surveillance by combining the temporal modeling strengths of Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks with a computationally inspired episodic memory mechanism, mirroring the contextual recall functions of the hippocampus. This unique integration allows the model to not only process sequential data but also to retain and retrieve relevant long-term contextual information, enabling the detection of subtle and temporally dispersed anomalous behaviors that conventional models often miss.

A key design philosophy behind HiMeLSTM is its operational practicality. The framework relies solely on standard visual data from surveillance feeds, augmented by a straightforward manually defined zone mapping system. This approach deliberately eliminates the dependency on complex, expensive, and often privacy-invasive infrastructure such as distributed sensor networks or detailed digital twins. By doing so, HiMeLSTM significantly lowers the barrier to deployment, offering a solution that is both easier to implement and capable of delivering real-time performance on resource-constrained hardware.

The core innovation, the Episodic Memory Unit (EMU), acts as a dynamic repository of past events. It enhances the model’s contextual awareness by allowing it to cross-reference current crowd dynamics with stored patterns. This is crucial for distinguishing between benign crowd formations (like orderly queues) and genuine threats, thereby reducing false alarms triggered by “structured crowding.”

Comprehensive experimental results on benchmark datasets demonstrate that HiMeLSTM consistently outperforms a range of existing models, including Vanilla LSTM, ConvLSTM, and Transformers, across key metrics such as accuracy, Anomaly Detection Rate (ADR), and F1-score. The model achieves superior anomaly sensitivity without incurring the prohibitive computational overhead of larger architectures, striking an optimal balance between performance and efficiency.

Looking forward, this research opens several promising avenues. Future work will focus on the practical deployment and optimization of HiMeLSTM on edge computing devices, further minimizing latency and power consumption for analysis. Furthermore, we plan to explore multimodal extensions of the architecture, integrating complementary data streams such as audio analysis for detecting auditory anomalies (e.g., screams, crashes) to create a more holistic and robust understanding of complex crowd scenarios, ultimately advancing the frontier of intelligent automated surveillance systems.