Abstract

Video action recognition aims to achieve the automatic classification of human behaviors by analyzing the actions in videos, with its core lying in accurately capturing the spatial detail features of images and the temporal dynamic features among video frames. In response to the problems of limited action recognition accuracy in videos containing complex temporal dynamics and large network model parameters, this paper proposes an innovative multi-feature fusion information modeling method. This paper designs a plug-and-play multi-feature action extraction (MFAE) module. The module adopts a multi-branch parallel processing strategy and integrates the functions of modeling and extracting temporal features, spatial features, and motion features to ensure the efficient modeling of the spatio-temporal information, inter-frame differences, and temporal dependencies of video actions. Meanwhile, the network employs a lightweight channel attention module (TiedSE), which reduces the complexity of the network model and decreases the number of network parameters. Finally, the effectiveness of the model is demonstrated on the Jester dataset, SomethingV2 dataset, and UCF101 dataset, achieving accuracies of 94.01%, 66.19%, and 96.74% with only 1.45 M parameters, significantly fewer than existing algorithms. The proposed method balances accuracy and computational efficiency in video action recognition, overcoming the shortcomings of traditional algorithms in temporal modeling and demonstrating its effectiveness in the task of video action recognition.

1. Introduction

Video action recognition, a prominent research focus in computer vision, is extensively applied in video surveillance, intelligent transportation, sports analysis, virtual reality, automated industrial manufacturing, and other domains [1,2]. Video action recognition technology identifies distinct behavior types, enhancing the intelligence and accuracy of video surveillance systems and optimizing human–computer interaction. Video action recognition typically necessitates substantial computer and storage resources for image processing, feature extraction, classification, and the retention of video frames, feature vectors, classifier parameters, and other related data. Consequently, the consumption of substantial resources is a prevalent issue. Minimizing the computational load and parameters of the model is crucial for the deployment of practical applications.

Mainstream action recognition approaches are categorized into three primary types: 3D convolution-based networks, 2D convolutional networks incorporating temporal variations, and alternative networks exemplified by two-stream architectures. Three-dimensional networks have emerged as the preferred option for video tasks due to the temporal dimension of video and the input being a five-dimensional vector. Tran et al. [3] introduced the seminal 3D network for video interpretation. Carreira et al. [4] introduced I3D, whereas Varol et al. [5] examined the impact of video clip duration and size on action recognition efficacy using the C3D model. Liu [6] input video visual content using I3D processing, extracted rapid and gradual temporal dynamics features through feature sequences, and subsequently input them into the short-term behavior spatio-temporal attention module for action identification. Nonetheless, the intensive computations required by 3D convolutional networks restrict their applicability. Since 2018, the research interest in 3D convolutional networks has diminished. Two-dimensional convolutional networks are extensively utilized in video action recognition owing to their efficiency benefits. Wang et al. [7] posited that TSN employs sparse sampling to integrate inter-frame information for temporal modeling. Lin et al. [8] introduced TSM, wherein select input feature channels are displaced along the temporal axis to attain comparable classification accuracy to 3D convolutional networks; yet, explicit temporal modeling remains insufficient. Weng et al. [9] introduced an improved information filter to detect variations in inter-frame information. Jiang et al. [10] asserted that ESTI emulates short-term and long-term information through local motion extraction and global multi-scale feature enhancement. Yu et al. [11] proposed AMA, which encodes the characteristics of spatio-temporal aggregation and channel excitation structures within a module and integrates them into the standard ResNet architecture. Wang et al. [12] introduced a two-stream 3D convolutional network for the extraction of spatial and motion information. Tan et al. [13] presented a bidirectional LSTM network. Chen et al. [14] developed an end-to-end framework for efficient video action detection utilizing the Vision Transformer (ViT) [15]. However, ViT employs a substantial number of parameters to represent the intricate characteristics and interrelations in the image, resulting in a substantial number of parameters. The effective processing of spatio-temporal information is essential for video action recognition. Disregarding temporal variations can often result in erroneous assessments of symmetrical movements [16], such as clockwise and counterclockwise rotations of the hand.

In summary, current video action recognition systems exhibit issues including elevated computational complexity and substantial model parameters. This research presents an enhanced lightweight model for multi-feature fusion based on a 2D convolutional network, designed to increase recognition accuracy while minimizing computational complexity. This paper proposes an enhanced network model based on the 2D convolutional network, which addresses feature extraction and computational cost, mitigates the limitations of the 2D convolutional network’s weak feature extraction capability, and enhances accuracy while maintaining a low computational load. The most lightweight model in the MobileNet series, MobileNetV3 (MNv3) [17], serves as the backbone network, and a sparse temporal sampling method [7] is incorporated into the domain of video recognition. The main contributions of this work can be summarized as follows:

- Introduction of the SETV module: By decoupling three-dimensional convolutions and employing the SCRU attention mechanism to enhance spatio-temporal feature extraction, computational complexity and redundant information are reduced, while superior recognition performance is achieved;

- Introduction of the LTA module: By utilizing multi-scale information fusion and class residual link technology to address long-term dependence issues, the deficiencies of existing global time modeling methods are rectified;

- The MNV3-TMFE design successfully integrates time, space, and motion feature extraction in a multi-branch parallel configuration. The inter-frame interaction is effectively managed via the feature fusion technique, enabling the automatic locking of important frames, which significantly enhances action recognition precision. Its plug-and-play attributes render it extensively utilized in diverse 2D networks, offering a comprehensive and efficient feature extraction solution for video action detection;

- Introduction of the TiedSE module: This lightweight channel attention module effectively substitutes the conventional SE module, substantially decreasing the parameter count without compromising network performance, thereby enhancing the model’s overall efficiency.

2. Related Works

The MobileNetV3 architecture features fewer parameters and a rapid execution speed, primarily comprising a feature extraction component and a classification head. The feature extraction component incorporates a 2D convolution prior to the block for the initial extraction and transformation of input information. Blocks at all tiers execute profound feature extraction to guarantee the model’s depth and breadth. The bottleneck architecture aids in minimizing the number of model parameters. The 2D convolution subsequent to the block further refines and compresses the transmitted characteristics. The acquired features are transmitted to the classification head for categorization.

2.1. Enhancement of MNv3

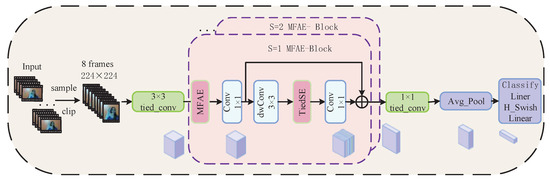

This study creates a plug-and-play multi-feature action extraction module (MFAE) based on MobileNetV3 to add different video feature data to the network model. The MFAE block structure is created by integrating the MFAE module into the block of MobileNetV3. Figure 1 illustrates the enhanced video action processing procedure of the MobileNetV3 network. The enhanced MobileNetV3 incorporates the MFAE block to replace the blocks in the 1st, 5th, 6th, 8th, 10th, and 11th layers of MobileNetV3 with skip connections. This insertion procedure is more economical than inserting all layers. The structure not only preserves the spatial feature learning capability of MobileNetV3 for the current action image but also extracts temporal information from the video stream. Table 1 presents the precise updated network parameters, highlighting the amended MFAE block in red. This research emphasizes network efficiency by replacing the conventional squeeze-and-excitation module (SE module) with the TiedSE module. The precise procedure is as follows: A sequence of dynamic action video frames is sparsely sampled to acquire eight frames of 224 × 224 action images, which serve as input for feature extraction via the enhanced MobileNetV3. Analogously to the image processing methodology of MobileNetV3, the enhanced MobileNetV3 network transmits the deep feature extraction of the block to the classification head for categorization.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the improved MobileNetV3 network processing a video action sequence.

Table 1.

Comprehensive network specification table.

In Table 1, “Block” refers to the basic block in the original MobileNetV3, “MFAE Block” refers to the basic block that includes the multi-feature action extraction module, and “TiedConv2d” refers to the 2D convolution layer that enables the bound block convolution to function. The expansion size denotes the number of convolution kernels utilized during the dimensionalization of the first 1 × 1 convolution in each block. TiedSE denotes the utilization of the TiedSE module. NL denotes the nonlinear type employed, HS signifies the h-swish activation function, and RE indicates the ReLU activation function. NBN signifies the absence of batch normalization. When the stride is set to 1 and the input channel matches the output channel, the block incorporates a residual connection; conversely, when the stride is set to 2, the residual connection is omitted.

2.2. Development of the Multi-Feature Action Extraction Module

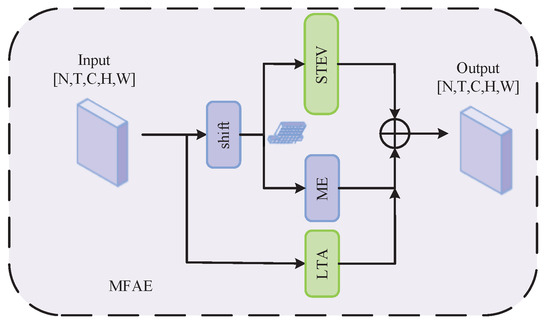

Figure 2 illustrates the design of this paper’s multi-feature action extraction (MFAE) module, which concurrently processes spatio-temporal information, motion data, and long-range temporal information in video actions. A shift operation [8] adds the time dimension. The Redundant Spatial-Temporal Extraction (STEV) module finds important spatio-temporal features. The Motion Excitation (ME) module [18] examines differences between frames, and the Long-distance Time Aggregation (LTA) module makes it easier to model time remotely. Each module collaborates to guarantee the effective extraction and integration of video action elements. We achieve precise recognition and analysis of symmetrical actions by examining the temporal variations and modalities within the video frame. Engineered as a plug-and-play feature extraction component with inherent flexibility, the multi-feature action extraction module yields identical shapes for both its input and output.

Figure 2.

Structure of the multi-feature action extraction module.

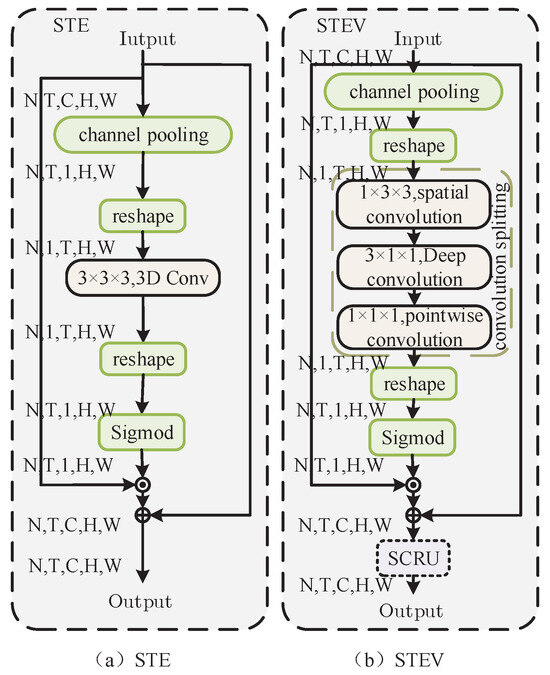

2.2.1. Enhancement of STEV

The de-redundant spatio-temporal extraction (STEV) module employs a 3D convolution to enhance the spatio-temporal information of the video, building upon the foundation of STE [16]. Figure 3b illustrates the configuration. Due to the substantial expense associated with the 3D convolution, this article employs a deep separable (2 + 1)D convolution to decompose the 3D convolution. After receiving an input V , we initially pool the channel dimension to create a space-time tensor , which averages the channel dimension. After undergoing deformation and reshaping to , we transmit it to the depth-separable (2 + 1)D convolution. This process is analogous to performing the initial convolution in both the channel and spatial dimensions, followed by the depth-separable convolution operation in the temporal dimension. Upon sigmoid activation, we revert to V and then fuse it. This paper positions the redundant space-channel reconstruction attention (SCRU) at the end of the STEV module to mitigate inherent redundancy and create a lightweight network model. It employs parallel methods to eliminate spatial and channel redundancy, thereby decreasing the model parameters.

Figure 3.

Comprehensive structural diagram of the spatial-temporal extraction module for redundancy elimination: (a) STE module; (b) STEV module.

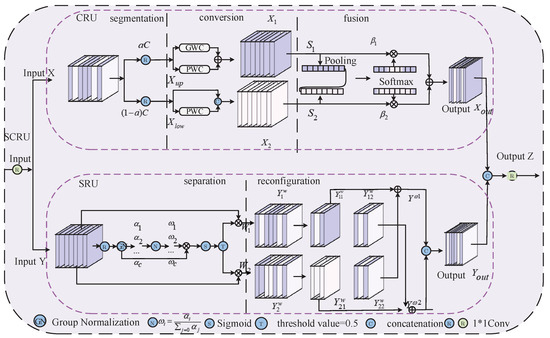

Figure 4 illustrates the SCRU, which encompasses channel reconstruction attention (CRU) and spatial reconstruction attention (SRU) [19]. CRU uses a segmentation–conversion–fusion method to reduce channel redundancy, and SRU uses a separation–reconstruction method to reduce spatial redundancy. This article employs a 1 × 1 convolution to reduce the spatial and channel dimensions by fifty percent, followed by information fusion. We partition the input into and . CRU segments the input based on a segmentation ratio of 0.5; thereafter, it applies a 1 × 1 convolution for channel compression at a ratio of 4. The conversion procedure combines the spatial characteristics and , with representing a high-level feature with reduced redundancy. It then executes convolutions (GWC and PWC) to produce . uses PWC to extract features from superficial details and reutilizes to integrate the two:

The fusion stage employs a pooling procedure to consolidate information. Ultimately, the feature importance vectors and guide the amalgamation of and along the channel direction to derive the channel refinement feature.

The SRU separation operation cuts the feature map in half in the spatial dimension and uses the scale factor in the group normalization (GN) layer to divide the feature map into groups based on the amount of spatial information. After re-weighting, the sigmoid function transforms the weight to the (0, 1) interval and employs a threshold for gating. The threshold designates the information weight as and the non-information weight as . One can articulate the acquisition of weights as follows:

Figure 4.

SCRU module.

The reconstruction operation uses cross-weighted fusion addition to combine information-dense features with less informative ones, thereby producing features that are more information-rich. The extracted information is ultimately reinstated to the original channel by a 1 × 1 convolution, facilitating information interaction to yield the total module output , where , .

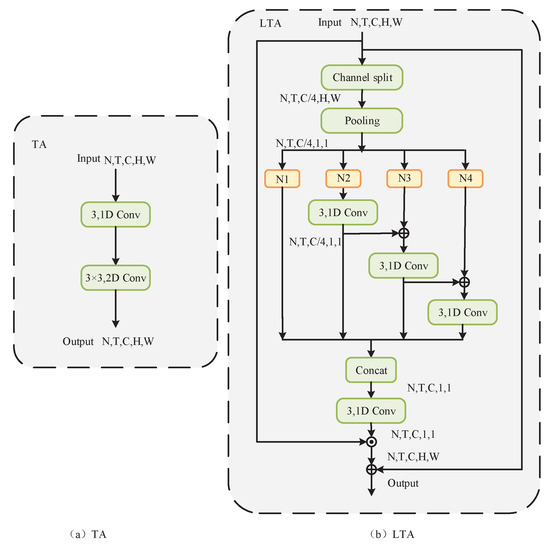

2.2.2. Enhancement of LTA

Time information extraction often employs local time convolution to process adjacent frames simultaneously, as illustrated in the structure in Figure 5a [20]. Only a deep network with numerous stacked local processes can represent the long-term structure. The relayed data from distant frames will gradually diminish, resulting in a limited ability to perceive the overall temporal framework. The Long-time Aggregation (LTA) module improves remote time modeling capabilities by integrating data from several segments, as illustrated in Figure 5b. The module initially partitions the input features into four segments along the channel dimension, with each segment modified using average pooling to accommodate local convolutions:

To carefully record temporal features, the last three segments use a cascaded temporal sub-convolution layer to gradually expand the receptive field. This covers a wider range of temporal contexts and changes the module into a hierarchical cascade structure.

Figure 5.

Structural diagram of the LTA module for long-distance time series: (a) TA module; (b) LTA module.

The class residual structure connection mechanism facilitates information transfer across segments, prevents gradient vanishing, and improves the model’s stability and learning capacity. Various fragments within the LTA module may possess distinct sizes of acceptance domains. The initial fragment directly preserves the information from the input fragment , maintaining its acceptance domain within the minimum dimensions of 1 × 1 × 1. Through the transfer and aggregation of information among fragments, the equivalent receptive field of is considerably enlarged, attaining three times the original receptive field. The multi-segment receptive field design allows the LTA module to pick up on both short-term and long-term temporal dependencies. This makes the output features richer and more complete in terms of space and time, which avoids the problems of older methods that only use one local convolution.

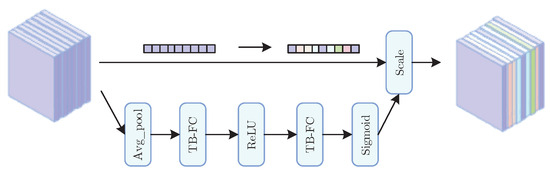

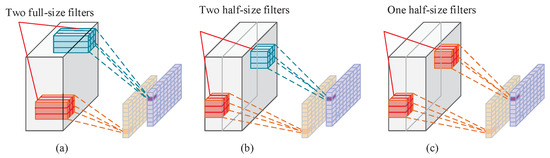

2.3. Lightweight TiedSE Module

The SE module is an attention mechanism that adjusts channel weights. This work replaces the SE module with a lightweight TiedSE module [21]. Figure 6 illustrates the TiedSE module. The TiedSE module uses a bound-block convolution in the fully connected layer, which forms the TB-FC structure. The TiedSE module can significantly decrease the parameter count owing to the bound-block convolution. As an example, we use g = 2 for the number of group convolution groups and B = 2 for the number of bound-block groups. K represents the number of input channels, the size of the convolution kernel, and the size of the output channel. The parameter P of the regular convolution, group convolution, and bound-block convolution is presented in Formula (6), excluding any bias considerations. Figure 7 presents a schematic representation of the convolution process, illustrating the conventional convolution in Figure 7a, the group convolution in Figure 7b, and the bound-block convolution in Figure 7c. Figure 6 illustrates that the theory of the bound-block convolution resembles that of the group convolution; however, the bound-block convolution necessitates only a half-size filter, whereas the standard convolution requires two full-size filters, resulting in parameters that are one-fourth those of the standard convolution. The bound-block convolution decreases the effective filter count by reapplying filters across many feature groups, thereby lowering the parameter count.

This paper additionally implements a bound-block convolution in the 2D convolution layer before and after the initiation and conclusion of the fundamental block layer of MobileNetV3, thereby substantially diminishing the parameter count of the network model. The TiedSE module enhances the efficiency of the overall design.

Figure 6.

TiedSE module.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of the convolution process: (a) regular convolution; (b) group convolution; (c) bound-block convolution.

3. Experiments

3.1. Datasets

The Jester dataset is a dynamic gesture dataset captured from a third-person perspective in RGB mode, with possible applications in human–computer interaction. It contains 27 distinct types of gestures, and the actors’ backgrounds and appearances vary significantly. There are 118,562 training videos, 14,787 verification videos, and 14,743 test videos, with a ratio of 8:1:1. The Jester dataset includes numerous symmetrical motions, including turning the hand clockwise, turning the hand counterclockwise, zooming out with two fingers, and zooming in with two fingers, as well as upward and downhill sliding. Independent gestures include swinging and stopping.

The SomethingV2 dataset is an extensive collection intended for video comprehension and activity identification. The collection comprises 220,847 .webm-formatted video clips encompassing 174 activity types. The dataset encompasses a diverse array of activity categories, including several daily activities, item manipulations, and social interactions. The variety of activities allows the model to acquire features and patterns associated with distinct sorts of actions, hence improving its capacity to comprehend and identify actions in diverse real-world contexts. Given that the video format is .webm, we must perform a frame extraction operation to convert the .webm videos into .jpg format frames for processing, while maintaining an 8:1:1 division ratio.

The UCF101 is a widely utilized video classification dataset with 101 distinct action categories. Each category comprises between 100 and 300 video segments, culminating in a total of around 13,000 video clips. These video segments are derived from actual YouTube videos, with each clip lasting roughly 10 to 30 s. Given that the video format is .avi, we must perform a frame extraction operation to convert the .avi videos into .jpg format frames for processing, while maintaining an 8:1:1 division ratio.

3.2. Training and Setup

This research employs a sparse sampling method for each video during the training process. Initially, eight frames are randomly chosen from each input video. The short side length of each frame is set to 256. During the training phase, the data are augmented utilizing two methods: corner clipping and random scaling. The dimensions of each clipping zone are standardized to 224 × 224 to facilitate data preparation for model training. This research employs the MobileNetV3-small model weights as the pre-training weights. The training parameters for the Jester dataset are as follows: the total number of training rounds is 25, the batch size is 16, the weight decay coefficient is 5 × 10−4, the initial learning rate is 0.01, and the learning rate is reduced by a factor of 10 at the 5th, 10th, and 15th rounds. The training parameters for the SomethingV2 dataset are as follows: the total number of training rounds is 50, the batch size is 32, the weight decay coefficient is 5 × 10−4, the initial learning rate is 0.01, and the learning rate is reduced by a factor of 10 for the 30th, 40th, and 45th rounds. The training parameters for the UCF101 dataset are as follows: the total number of training rounds is 100, the batch size is 16, the weight decay coefficient is 5 × 10−4, the initial learning rate is 0.01, and the learning rate is reduced by a factor of 10 for the 30th, 50th, and 70th rounds.

This article employs the stochastic gradient descent optimization procedure with a momentum of 0.9, using cross-entropy loss as the experimental loss function. The experiment utilizes an Intel Core i9-13900k CPU, an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4080Ti 16G graphics card (Manufacturer: Nvidia, City: Harbin, China), Python version 3.8.16, and the deep learning framework PyTorch 1.8.0 with CUDA 11.1 for training purposes. The network’s input is represented by the final prediction outcome, which is the softmax average score of all segments.

3.3. Results

3.3.1. Ablation Experiments

An ablation experiment was conducted on the Jester and Something V2 datasets to validate the function of the feature extraction blocks within the MFAE module, specifically examining the shift operation, the STEV module, and the ME module. The model’s validity was assessed using four indicators: the number of parameters (Param), the number of floating-point operations (FLOPs), and recognition accuracy (Top-1/Top-5). The Top-1 accuracy denotes the standard accuracy, which pertains to the operation with the highest confidence score, while the Top-5 accuracy encompasses the five actions with the highest prediction scores, including the correct type. The findings are presented in Table 2 and Table 3. Each enhancement module in Table 2 enhanced performance while escalating constrained computational expenses. Notably, Experiments 1 and 2 demonstrated that the change had little impact on computational cost, while accuracy improved from 74.24% to 84.14%, indicating that the STEV module offered efficient spatio-temporal characteristics for the network. Experiments 1 and 3 revealed an increase in accuracy from 74.24% to 93.36%. Experiments 1 and 5 demonstrated that the LTA module effectively captured the long-range temporal link and compensated for the absence of shift information, resulting in an improvement in accuracy from 74.24% to 92.73%. Efficiency was employed to assess the correlation between performance enhancement and additional computations. The formula is presented in Formula (7):

Within this context, F denotes the growth rate of FLOPs, whereas T signifies the increase in the Top-1 accuracy, indicating the percentage of additional FLOPs required for a 1% improvement in the Top-1 accuracy. Clearly, a lower number of FLOPs corresponds to greater efficiency. The data analysis in Table 2 indicates that the efficiencies of Shift, STEV, ME, and LTA were 1.7%, 0.8%, 2.8%, and 1.8%, respectively. The STEV module was the most efficient. Comparing Experiment 1 with Experiment 6 reveals that the final accuracy of the MFAE module was 93.84%, demonstrating the module’s efficacy.

Table 2.

Results of ablation experiment of the MFAE module on the Jester dataset.

Table 3.

Results of ablation experiment of the MFAE module on the SomethingV2 dataset.

Ablation tests were conducted on the Jester and SomethingV2 datasets to evaluate the efficacy of the MFAE and TiedSE modules within the network model. The findings are presented in Table 4. For the Jester dataset, a comparison between Experiments 1 and 2 reveals that the incorporation of the MFAE module resulted in an increase of 0.19 M in the number of parameters, an increase of 1.46 G in FLOPs, and an increase of 19.6% in accuracy. The primary function of the MFAE module is to enhance recognition accuracy, with nearly all improvements attributed to it. A comparison of Experiments 1 and 3 reveals that the inclusion of the TiedSE module resulted in a reduction of 0.4 M in the number of parameters, a decrease of 0.04 G in FLOPs, and an increase of 0.17% in accuracy, suggesting that this module does not significantly enhance recognition accuracy. Its primary function is to diminish the number of parameters in the network. A comparison of Experiments 1 and 4 reveals that the Top-1 accuracy was 94.01% with the incorporation of the multi-feature extraction block’s MFAE and TiedSE modules, representing a 19.77% improvement over the baseline model. Despite a modest increase in FLOPs, the model’s parameter count decreased by 0.24 M following optimization, resulting in fewer additional parameters while fully using the spatio-temporal information of video actions.

Table 4.

Table of results of ablation experiments for the overall network model.

3.3.2. Comparison Experiment

The proposed method was evaluated against established representative methods on the Jester dataset, with the experimental findings presented in Table 5. This paper employed the R (2 + 1) D-34 [22], R3D [23], STASTA [6], TSN, TSM [8], PAN [24], ESTI [10], ACTION-Net [16], ViViT-L, and CvT-MTAM [25] methodologies to assess the efficacy of the experimental outcomes in video action recognition, based on the number of parameters, floating-point operations, frame rate (FPS), and accuracy.

Table 5.

Results of comparison experiments on the Jester dataset.

Table 5 indicates that 3D convolutional networks typically need substantial computational resources, resulting in reduced operational speed. For instance, the parameters of R3D were 44.45 M for model size, 84.33 G for FLOPs, and 3.16 FPS. The parameters of the basic 2D convolutional network experienced a minor reduction, resulting in an increase in processing speed; however, recognition accuracy remained somewhat insufficient. The Top-1 accuracy of TSN was 81%. The 2D convolutional network with temporal modeling offered substantial benefits in terms of network parameters and operational speed. For instance, ESTI exhibited the highest accuracy, with a Top-1 accuracy of 94.47%. Utilizing the Transformer as the variation model, the accuracy, parameter count, and network execution speed closely matched those of the 2D and 3D convolutional networks, while the model remained lightweight. For instance, the parameter count of CvT-MTAM was 24.60 million, and the FLOPs amounted to 64.52 billion. The ResNet architecture possessed considerable depth and a substantial number of parameters; however, its modeling capacity surpassed that of the simpler MobileNet architecture. The proposed method thoroughly extracted video data, enhanced 2D convolutional modeling capabilities, and ultimately achieved a reduced parameter count and increased network processing performance. The final parameter count was 1.45 million, FLOPs were 7.31 billion, FPS was 106.85, and the Top-1 accuracy was 94.01%. The Top-1 accuracy was only 0.46% inferior to that of ESTI. The proposed method attained an optimal equilibrium between the number of parameters and computational efficiency, which is highly significant for practical applications.

This research additionally conducted comparative studies with established representative approaches on the SomethingV2 and UCF101 datasets. The experimental findings are presented in Table 6. The table indicates that the experimental results closely align with the trends observed on the Jester dataset. In the experiment, the ViViT-L technique demonstrated superior performance on the SomethingV2 dataset, indicating that the model utilizing the Transformer architecture possesses distinct advantages in handling large-scale datasets. The approach proposed in this paper demonstrated comparable accuracy while exhibiting significant advantages in the parameter count. The proposed method performed the best on the UCF101 dataset, likely due to the multi-fragment acceptance domain of the LTA module, which effectively captures dependencies across various time scales and aids in processing action information within complex backgrounds.

Table 6.

Results of comparison experiments on the SomethingV2 and UCF101 datasets.

Device compatibility and memory constraints are critical issues in practical applications. The model proposed in this paper can be directly deployed on hardware devices while maintaining superior performance. For memory-constrained hardware devices, the accuracy of the network model during deployment can be ensured by improving data-loading methods, utilizing intermediate-result storage strategies, and exploring model-compression techniques to achieve rapid operation of the model on edge devices.

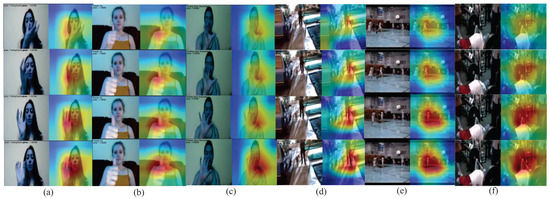

3.4. Visualization Results

This article emphasizes training the entire network model’s attention to focus on gestures, enabling the machine to recognize video motions in the Jester dataset and provide heat maps. Three sets of activities were randomly chosen, as illustrated in Figure 8a–c. The red section of the graphic denotes the portion of the model exhibiting heightened attention. The greater the significance of the hand movement, the more concentrated the model becomes on the hand, demonstrating the model’s efficacy in video action identification. Additionally, the model randomly selected three groups of actions from the UCF101 dataset, as shown in Figure 8d–f. The red part of the figure focuses on the action subject.

Figure 8.

Heat map of video action recognition on the Jester dataset: (a) turning hand clockwise; (b) thumb up; (c) turning hand counterclockwise. Heatmap of video action recognition on the UCF101 dataset: (d) walking with dog; (e) basketball; (f) bench press.

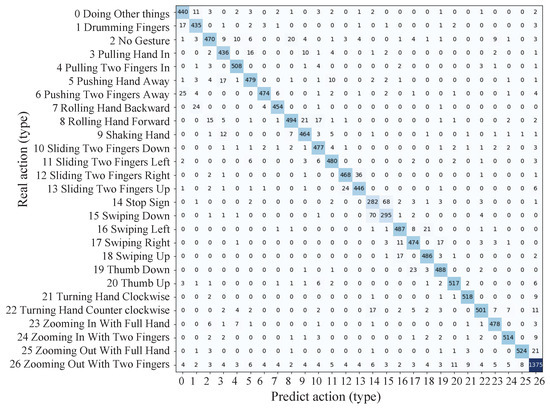

This research utilized 27 types of gesture confusion matrices, as illustrated in Figure 9. The network demonstrated proficient recognition of mirror motions, including 7 instances of rolling the hand backward, 8 instances of rolling the hand forward, 21 instances of turning the hand clockwise, and 22 instances of turning the hand counterclockwise, with a near-zero likelihood of mutual misclassification. The action of zooming out with two fingers was categorized further because of its larger base, which was almost three times the size of the other categories, as shown in the confusion matrix. The number of misclassified items was higher in this category. The 14 stop sign and 15 swiping down motions were more prone to mutual misclassification. The overlap between the concluding action of the stop gesture and the palm-downward gesture was significant, resulting in substantial spatial and temporal similarities, which increased the likelihood of misclassification.

Figure 9.

Confusion matrix for 27-class gesture classification on the Jester dataset.

3.5. MFAE Module Migration Results

The MFAE module functions as a plug-and-play component, facilitating migration across various backbone networks. The datasets utilized were Jester and SomethingV2 to assess the impact. The findings are presented in Table 7. Table 7 demonstrates that the integration of the module into various networks enhanced the accuracy of video action detection, with the optimal insertion point being before the block. The Jester dataset exhibited a 13.6% increase in performance on the ResNet-18 backbone network, an 8.55% increase on the ConvNext backbone network, a 6.82% increase on the CvT backbone network, a 22.74% increase on the MobileNetV2 backbone network, a 19.36% increase on the MobileNetV3-small backbone network, and a 29.73% increase on the MobileNetV3-large backbone network. The experiments demonstrated that the module can adeptly mimic video feature information with few alterations to the original network, thereby enhancing its versatility and reusability.

Table 7.

Results of MFAE migration across different backbone networks.

4. Conclusions

This paper effectively integrates the MFAE module, utilizing a 2D convolutional network, with the TiedSE module to develop an efficient model for video action recognition. The model generation technique efficiently circumvents expensive 3D convolution and optical flow calculations, reducing computational complexity. The meticulously crafted MFAE module enables precise modeling of spatio-temporal information in videos, particularly for symmetrical motions, which is crucial for understanding gesture intentions in human–computer interaction contexts. The model attained an accuracy of 94.01% on the Jester dataset, 66.19% on the SomethingV2 dataset, and 96.74% on the UCF101 dataset. The frame rate reached 106.85 frames per second, with a parameter count of only 1.45 million, thereby achieving an exceptional balance between precision and computational efficiency. This paradigm is competitive in resource-constrained contexts, such as edge devices, and satisfies application scenarios with stringent real-time requirements, such as video surveillance. This enhancement technique demonstrates considerable benefits in scenarios requiring high real-time performance and acceptable accuracy tolerance, offering new opportunities for the advancement of video action detection technology. The model’s applicability potential in intricate circumstances (e.g., overlapping or multi-agent actions) will be further investigated in the future.

Author Contributions

J.L. contributed to the study methodology, the implementation of the experimental design, and the editing of the article for publication. W.L. was responsible for the study strategy, experiments, and core manuscript content. K.H. conducted data analysis and thesis editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by two funding: the Natural Science Foundation of Heilongjiang Province, grant number ‘LH2023E086’, and the Science and Technology Project of Heilongjiang Provincial Department of Transportation, grant number ‘HJK2024B002’.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets (Jester, SomethingV2, UCF101) were analyzed in this study. But The SomethingV2, UCF101 datasets presented in this article are not directly available because [Experiments need to be performed after additional framing processing].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MNv3 | MobileNetV3 |

| MFAE | Multi-Feature Action Extraction |

| STEV | Spatial-Temporal Extraction |

| LTA | Long-distance Time Aggregation |

| ME | Motion Excitation |

References

- Xie, Y.G.; Wang, Q. Summary of Dynamic Gesture Recognition Based on Vision. J. Comput. Eng. Appl. 2021, 57, 68–77. [Google Scholar]

- Bono, F.M.; Radicioni, L.; Cinquemani, S. A novel approach for quality control of automated production lines working under highly inconsistent conditions. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 122, 106149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.; Bourdev, L.; Fergus, R.; Torresani, L.; Paluri, M. Learning spatiotemporal features with 3D convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the 15th IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, ICCV 2015, Santiago, Chile, 13 December 2015; pp. 4489–4497. [Google Scholar]

- Carreira, J.; Zisserman, A. Quo vadis, action recognition? A new model and the kinetics dataset. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1705.07750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varol, G.; Laptev, I.; Schmid, C. Long-Term Temporal Convolutions for Action Recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2018, 40, 1510–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ting-Long, L. Short-Term Action Learning for Video Action Recognition. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 30867–30875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, Z.; Qiao, Y.; Lin, D.; Tang, X.; Van Gool, L. Temporal segment networks: Towards good practices for deep action recognition. In Proceedings of the 21st ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 3–7 November 2014; pp. 20–36. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Gan, C.; Han, S. TSM: Temporal shift module for efficient video understanding. In Proceedings of the 17th IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, ICCV 2019, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 7082–7092. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, J.; Luo, D.; Wang, Y.; Tai, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, J.; Huang, F.; Jiang, X.; Yuan, J. Temporal distinct representation learning for action recognition. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 363–378. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, S. ESTI: An action recognition network with enhanced spatio-temporal information. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 2023, 14, 3059–3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Chen, Y. AMA: Attention-based multi-feature aggregation module for action recognition. Signal Image Video Process. 2023, 17, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, C.; Zhang, R. Dynamic Gesture Recognition Combining Two-stream 3DConvolution with Attention Mechanisms. J. Electron. Inf. Technol. 2021, 43, 1389–1396. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, K.S.; Lim, K.M.; Lee, C.P.; Kwek, L.C. Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory with Temporal Dense Sampling for human action recognition. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 210, 118484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Tong, Z.; Song, Y.; Wu, G.; Wang, L. Efficient Video Action Detection with Token Dropout and Context Refinement. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.08451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexey, D. An Image is Worth 16X16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; She, Q.; Smolic, A. Action-Net: Multipath excitation for action recognition. In Proceedings of the Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2021, Beijing, China, 19 June 2021; pp. 13209–13218. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.; Sandler, M.; Chu, G.; Chen, L.C.; Chen, B.; Tan, M.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Pang, R.; Vasudevan, V.; et al. Searching for mobileNetV3. In Proceedings of the 17th IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, ICCV 2019, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 1314–1324. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Schmid, C. Action recognition with improved trajectories. In Proceedings of the 14th IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, ICCV 2013, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 1–8 December 2013; pp. 3551–3558. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wen, Y.; He, L. Scconv: Spatial and channel reconstruction convolution for feature redundancy. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 6153–6162. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Ji, B.; Shi, X.; Zhang, J.; Kang, B.; Wang, L. TEA: Temporal excitation and aggregation for action recognition. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.01398. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Yu, S.X. Tied Block Convolution: Leaner and Better CNNs with Shared Thinner Filters. In Proceedings of the 35th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, AAAI 2021, New York, NY, USA, 2–9 February 2021; pp. 10227–10235. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, D.; Wang, H.; Torresani, L.; Ray, J.; LeCun, Y.; Paluri, M. A Closer Look at Spatiotemporal Convolutions for Action Recognition. In Proceedings of the 31st Meeting of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2018, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 6450–6459. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, D.; Ray, J.; Shou, Z.; Chang, S.F.; Paluri, M. ConvNet architecture search for spatiotemporal feature learning. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1708.05038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zou, Y.; Chen, G.; Gan, L. PAN: Towards fast action recognition via learning persistence of appearance. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2008.03462. [Google Scholar]

- Jie, L.; Yue, W.; Ming, T. Dynamic Gesture Recognition Network with Multiscale Spatiotemporal Feature Fusion. J. Electron. Inf. Technol. 2023, 45, 2614–2622. [Google Scholar]

- Arnab, A.; Dehghani, M.; Heigold, G.; Sun, C.; Lučić, M.; Schmid, C. ViViT: A Video Vision Transformer. In Proceedings of the 18th IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, ICCV 2021, Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 6816–6826. [Google Scholar]

- Dave, I.R.; Rizve, M.N.; Shah, M. FinePseudo: Improving Pseudo-Labelling through Temporal-Alignablity for Semi-Supervised Fine-Grained Action Recognition. In European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 389–408. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).