Abstract

The digital integrated circuit (IC) design industry is continuously evolving. However, the rapid advancements in technology are accompanied by major reliability concerns. Conventional clock-based synchronous designs become exceedingly susceptible to transient errors, caused by radiation rays, power jitters, electromagnetic interferences (EMIs), and/or other noise sources, primarily due to aggressive device and voltage scaling. quasi-delay-insensitive (QDI) asynchronous (clockless) circuits demonstrate inherent robustness against such transient errors, owing to their unique architecture. However, they are not completely immune. This article presents a hardened QDI Sleep Convention Logic (SCL) asynchronous architecture, which can fully recover from radiation-induced single-event effects such as single-event upset (SEU) and single-event latch-up (SEL). Multiple benchmark circuits are designed based on the proposed architecture. The simulation results indicate that the proposed designs offer substantial energy savings per operation, dissipate substantially less power during idle phases, and have lower area footprints in comparison to designs based on an existing resilient Null Convention Logic (NCL) architecture at the cost of increased latency. In addition, a formal verification framework for the proposed architecture is also presented. The performance and scalability of the proposed verification scheme are demonstrated using several multiplier benchmark circuits of varying width.

1. Introduction

Reliability is a major concern in the design of modern digital integrated circuits (ICs), particularly those that are intended to withstand extreme environmental conditions. Electronic devices are becoming increasingly susceptible to transient errors, otherwise referred to as “soft errors”, which are caused by radiation rays, electromagnetic interference (EMI), power jitters, and/or other noise sources [1]. These errors result in single-event effects (SEEs), which can compromise the circuit’s functionality. SEEs give rise to two notable phenomena: single-event upset (SEU) [2] and single-event latch-up (SEL) [3]. When radiation-induced high-energy particles strike the sensitive circuit nodes, it can trigger the generation of short-duration current spikes. If the current level surpasses a specific threshold, it can cause undesired switching in logic components, resulting in SEUs. SEL occurs when the device’s internal current gets amplified and generates a virtual short circuit between the supply and ground. Failure to cycle the excessive power may cause permanent damage to an IC. Such errors pose major reliability issues in conventional clock-based synchronous designs, particularly for devices operating at scaled technology nodes with minimal or fluctuating supply voltages [4,5]. Aggressive device and voltage scaling make such designs susceptible to process, voltage, and temperature (PVT) variations. Additionally, the SEEs can affect the synchronous digital circuitry’s timing behavior, leading to malfunction. Conversely, quasi-delay-insensitive (QDI) asynchronous circuits are clockless and, by default, insensitive to timing irregularities [6]. Furthermore, they are inherently more resistant to PVT variations, which makes them an exceptional choice for extreme environmental applications, including outer-space research, deep-sea exploration, and aerospace, military, and surveillance applications [7]. However, despite the fact that QDI circuits are more robust than their clocked counterparts, they are not completely resistant to SEU/SEL.

Multi-Threshold NULL Convention Logic (MTNCL) [8,9,10,11], also known as Sleep Convention Logic (SCL), is a QDI implementation paradigm that is a variant of the widely used NCL paradigm. SCL circuits are extremely power-efficient with an excellent ability to withstand PVT variations. Although different error resiliency schemes have been proposed for other QDI paradigms, such as NCL and Pre-Charge Half Buffers (PCHBs), no such schemes exist for SCL at the architecture level. This research focuses on addressing this limitation. The following are the major contributions of this work.

- A redundancy-based error-tolerant SCL architecture has been introduced.

- A categorical proof is presented to illustrate the proposed architecture’s ability to fully recover from an SEU or SEL without compromising functionality.

- The performance of the proposed architecture is evaluated and compared to an existing NCL-resilient scheme on four crucial fronts: transistor count, energy utilization per operation, idle stage power dissipation, and latency.

- A scalable verification scheme is developed for the proposed architecture. QDI asynchronous circuits are generally synthesized from their corresponding synchronous specifications utilizing design automation tools. During the process, the circuit undergoes substantial modification, resulting in an implementation that differs significantly from the specification. We have formalized a verification framework based on equivalence checking, which can verify the safety (functional correctness) as well as the liveness (the absence of deadlock/livelock) of the synthesized error-resilient SCL circuits that are designed based on the proposed architecture.

This paper is divided into seven major sections. Section 2 provides an overview of the conventional SCL architecture and discusses some of the relevant error-tolerant QDI designs. Section 3 details the proposed resilient SCL architecture and provides categorical proof to demonstrate the ability of the circuit to recover from single-event effects, followed by the simulation results, comparison, and discussion in Section 4. The proposed verification scheme is detailed in Section 5, and the verification results are discussed in Section 6. Section 7 concludes the paper.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Conventional SCL Architecture

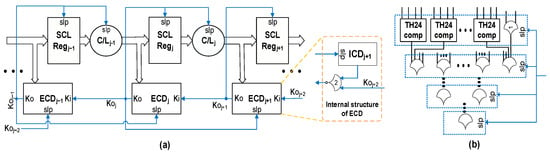

SCL employs a 1-hot data encoding and multi-rail logic, most commonly the dual-rail logic. In dual-rail logic, unlike traditional Boolean logic, each bit of information is encoded using two rails (or wires) [9,12]. A dual-rail signal, D, can assume any of the three possible values from the set {NULL, DATA0, and DATA1}. DATA0 () and DATA1 () are equivalent to Boolean logic 0 and 1, respectively. NULL () is a spacer state, which is used to separate two distinct DATA wavefronts at the input and their corresponding DATA wavefronts at the output. The two rails of a signal cannot be asserted simultaneously, making () an illegal/invalid combination. The conventional SCL framework is depicted in Figure 1a. Although there are a variety of MTNCL architectures, including Early-Completion Input-Incomplete (ECII) and Fixed ECII architecture (FECII), our research focuses on the Sleep Early-Completion and Registration Input-Incomplete (SECRII) framework, which offers the most optimal performance in terms of speed, area, energy utilization, and leakage dissipation [8,10,13].

Figure 1.

(a) SCL SECRII framework. (b) Internal structure of an ICD unit.

The SECRII SCL framework, as depicted in Figure 1a, is similar to the NCL framework in that each stage of an SCL pipeline consists of an SCL combinational logic unit (C/L) that performs the computation and a registration and completion detection unit that maintains the four-phased QDI handshaking protocol for synchronization. However, SCL has the following distinguishing features that separate it from NCL: (a) SCL integrates the multi-threshold CMOS (MTCMOS) technique [14] with NCL to improve power gating within the gates, thereby reducing leakage power dissipation [8,9]. (b) Similar to NCL, SCL has the same set of 27 fundamental threshold gates to implement any function with at most four uncomplemented variables. However, unlike NCL, the SCL gates are hysteresis-free, indicating their inability to hold a state. Thus, SCL gates do not require all their inputs to be de-asserted to de-assert their outputs; rather, each gate’s output is de-asserted by an additional sleep input. (c) SCL employs a modified completion detection structure, referred to as an early-completion detection (ECD) unit, as the conventional structure used for NCL cannot preserve the SCL circuit’s DI property. The ECD unit comprises an internal completion detection unit (ICD), which consists of a series of SCL TH12/TH24comp gates at the first level followed by a tree structure comprising SCL THnn gates, as shown in Figure 1b. The ICD unit functions as a DATA detector for a stage, generating ‘1’ (or ‘0’) when the stage computes a valid DATA (or NULL), respectively. Each ECD unit’s request input (Ki) is derived from the ECD output of the subsequent stage. The ICD output and Ki input are fed into an inverted NCL TH22 gate (with hysteresis and w/o sleep), TH22n, to generate the final ECD output (Ko). The acknowledgment output, Ko, generated by each stage’s ECD unit serves as the sleep signal for the registration and C/L units in that stage, the request signal (Ki) for the preceding ECD unit, and the sleep signal for the ECD unit in the subsequent stage (refer to Figure 1a) [15]. In SCL, early completion resets a stage to NULL by asserting the corresponding sleep signal, and therefore, propagating a separate NULL wavefront is not required. (d) SCL registers, unlike NCL registers, lack request input and acknowledge output. Once an SCL register gets asserted by a particular input, it cannot be de-asserted by the same input. Only the associated sleep signal can de-assert it. And (e) finally, due to their unique sleep-controlled synchronization, SCL circuits are not required to be input-complete or observable to preserve delay insensitivity, as is the case with NCL circuits.

2.2. Impact of Single-Event Effects on SCL Circuits

Single-event effects (SEEs), such as SEL and SEU, can affect the safety of the SCL circuits by causing incorrect outputs and the liveness of the circuits by causing incorrect control signals that lead to circuit deadlock. Two distinct types of transient defects can occur in logic, depending on whether the NMOS or PMOS is affected by radiation particles: a positive glitch (0 → 1 → 0) and a negative glitch (1 → 0 → 1). When the glitches are latched, they can result in a static positive error (0 → 1) or static negative error (1 → 0) [16]. It is straightforward to comprehend how unintended gate switching due to SEU/SEL can result in incorrect outputs and compromise the functionality of the circuit. Therefore, the primary emphasis of this section is to explain how SEU/SEL can cause a deadlock in SCL circuits.

In the SECRII SCL architecture (Figure 1a), the ECD unit in a stage detects and acknowledges a complete DATA/NULL at the inputs of the stage’s registers and only allows it to pass if the subsequent stage requests for DATA/requests for NULL (rfd/rfn). This indicates, under an error-free scenario, that when the jth stage register, Regj, has all its inputs as DATA (detected by the stage’s ICD unit, ICDj) and the ECD unit of the subsequent stage, ECDj+1, is requesting for data (rfd, i.e., koj+1 = 1), ECDj will evaluate to logic 0 (i.e., koj = 0). This will wake up the Regj and C/Lj units, allowing the DATA to propagate through the jth stage and the C/Lj unit to begin its computation. Note that if C/Lj produces a multi-bit dual-rail output, not all output bits may evaluate to DATA at the same time during computation, mostly due to different propagation delays in gates. In that case, C/Lj first transitions to a partial DATA or PDATA (some of the dual-rail signals are DATA, while others are NULL) state before transitioning to a complete DATA state. ECDj+1 will request for NULL (rfn, i.e., koj+1 = 0) only after the complete DATA is available at the Regj+1 input.

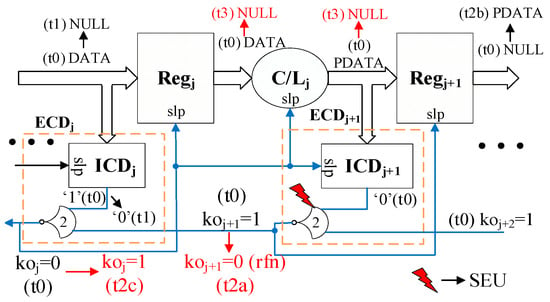

As per the deadlock-free SCL protocol, ECD in each stage must never be rfn before detecting the entire DATA wavefront at the stage’s register inputs. However, an SEL/SEU can corrupt it to cause an early null request, which can violate the SCL control protocol and prevent the circuit from advancing. To explain this further, consider the SCL circuit in Figure 2. Assume that at time t0, the circuit’s Regj+1 is latching a NULL and ECDj+1 is rfd, i.e., koj+1 = 1. A complete DATA set is available at Regj inputs. The ICDj unit outputs ‘1’ to indicate the detection of all DATA at the Regj inputs. Since the subsequent stage is rfd and the DATA is also available at the Regj inputs, the ECDj output, koj, is set to ‘0’. This activates (i.e., awakes) the stagej components and initiates the propagation of DATA through stagej. Once Regj has latched the DATA, the preceding stage, stagej−1, is put to sleep, enabling the next NULL to arrive at Regj’s input at time t1. ICDj unit is also slept to 0, indicating the NULL detection at the Regj inputs. At t2a, an SEU corrupts the ECDj+1 unit and causes koj+1 to become rfn prematurely, while Regj+1 has only PDATA at its inputs. The corrupted koj+1 value prematurely activates/awakes the stagej+1 components and the PDATA gets latched by Regj+1 (at time t2b). This early rfn also causes Koj to become 1 (at time t2c), which prematurely sleeps the stagej components to NULL (at time t3). As a result, the complete DATA will be lost. Consequently, koj+1 will be stuck at rfn and stagej will be stuck at NULL, leading to a deadlock. The SEU fault model assumes the corruption of a single gate, while the SEL model assumes the corruption of multiple gates [17]. Therefore, it follows that both SEU and SEL can affect the circuit’s liveness.

Figure 2.

SEL/SEU-affected SCL pipeline: a visual representation illustrating how the SCL pipeline’s liveliness can be compromised.

2.3. Resilient and Radiation-Hardened QDI Architectures

The conventional error detection, correction, and mitigation techniques applicable to synchronous designs, such as triple modular redundancy (TMR) [18], error correction codes (ECC), etc., are not readily applicable to QDI circuits, mostly because they exhibit different behaviors in the presence of errors due to their event-driven nature [5]. In TMR, for example, the original circuit is replicated three times, and the correct output is determined using a majority voting scheme, which is a straightforward solution for clocked circuits. However, the application of TMR in QDI circuits becomes exceedingly challenging due to their complicated handshaking mechanisms, local feedback (within the gate structures), and global feedback (control path) connections. In addition, QDI implementations inherently require more area, and the need for three copies of the circuit further limits their applications. ECC is also a redundancy-based reliability scheme; however, according to [19], transient errors in the QDI circuit’s control signals cannot benefit from the implementation of ECCs. Over the years, several resiliency schemes have been developed specifically for QDI circuits, addressing the associated challenges. A built-in soft error-correcting (BISEC) NCL architecture, capable of detecting and self-correcting radiation induced incorrect outputs, was proposed in [16]. The method modified the NCL architecture by introducing additional logic components, registration, and delay units per stage for error detection and re-computation. In the event of an SEU, the BISEC NCL framework halts the circuit operation until the error effects are resolved. The method has certain limitations, such as failing to detect errors during a NULL cycle and allowing faulty data to propagate that must be identified and discarded later; [20] addressed these limitations by further modifying the BISEC architecture. However, the architecture still fails to ensure complete resilience [21]. Jang and Martin developed a duplication and double-checking-based methodology for designing soft-error-tolerant QDI Pre-Charge Half Buffer (PCHB) circuits [19,22,23]. A dual-modular redundancy-based radiation-hardened NCL architecture (DMR-NCL) was proposed in [17]. These duplication-based methods have proven to be effective in designing fully resilient QDI asynchronous circuits; however, the robustness comes at the cost of longer latency, a significantly increased area, and energy overhead.

3. Error-Resilient SCL Circuit Design

3.1. Proposed SEL/SEU-Resistant SCL Architecture

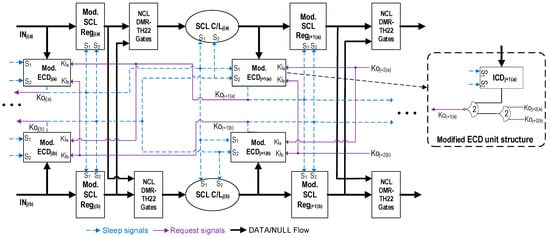

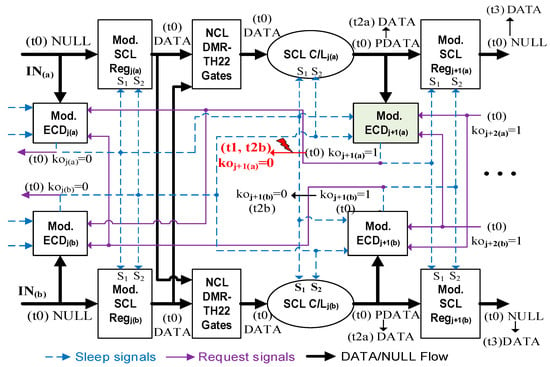

Figure 3 depicts the proposed SEL/SEU-resistant SCL architecture [24]. The following modifications are made to the original SCL architecture in Figure 1a to enable recovery during single-event effects:

Figure 3.

Proposed SEU/SEL-tolerant SCL framework.

- The original SCL pipeline is doubled.At the output of the registers in each stage, a series of additional NCL TH22 gates with hysteresis (referred to herein as DMR-TH22 gates) are added, which accept register outputs from both copies in the same stage as inputs. For instance, consider, in the original copy, a 1-bit SCL register with dual-rail input, D, and dual-rail output, F. The input and output of the corresponding duplicate register are Ds and Fs, respectively (note that ‘s’ in the signal name indicates that the signal is from the shadow/duplicate circuit. This convention will be followed throughout the paper). There will be two NCL-TH22 gates following the registers, one of which will have F.rail0 and Fs.rail0 as inputs, while the other will have F.rail1 and Fs.rail1 as inputs. The C-element [25] nature of NCL TH22 gates ensures that for each stage, the register outputs of both the circuits must match to allow further propagation.

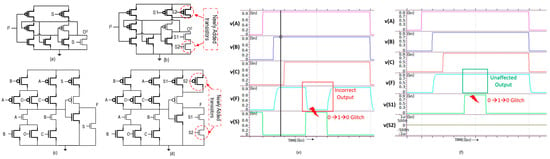

- Each register, C/L, and ICD unit is modified to accept two sleep signals, one from each copy. This is accomplished by adding two extra transistors (one PMOS and one NMOS) to the SCL gates and registers, as shown in Figure 4, preventing the gates from sleeping until both sleep signals are asserted.

Figure 4. (a) The Rail0 network of a traditional SCL register, (b) the Rail0 network of the modified SCL register, (c) a traditional SCL TH23 gate structure, (d) a modified SCL TH23 gate structure. (e) A positive glitch in the sleep signal that affects the traditional SCL TH23 structure in (d), and (f) how the modified structure can address the corruption of a single sleep signal.

Figure 4. (a) The Rail0 network of a traditional SCL register, (b) the Rail0 network of the modified SCL register, (c) a traditional SCL TH23 gate structure, (d) a modified SCL TH23 gate structure. (e) A positive glitch in the sleep signal that affects the traditional SCL TH23 structure in (d), and (f) how the modified structure can address the corruption of a single sleep signal. - One additional NCL TH22 gate is added before the inverting NCL TH22 (TH22n) gate in each ECD unit, which accepts the Ko outputs generated by the subsequent stage ECDs from both the original and duplicate copies, as shown in Figure 3.

Although our method follows a similar dual-modular redundancy (DMR)-based resilience scheme as used by Zhou et al. to design SEU/SEL-resistant NCL circuits in [17], our proposed architecture differs significantly from [17] to account for the substantial structural and behavioral differences between the original SCL and NCL components, as discussed in Section 2.1. As in [17], the pipeline is divided into multiple small groups with separate power supplies, with each group consisting of the newly added DMR-TH22 gates, the subsequent C/L unit, registers, and the ECD unit, as shown in Figure 3 with a green highlight. In the event of a current surge during SEL, an SEL protection unit will temporarily disconnect the supply of the affected group to prevent IC damage. Once the SEL effect subsides, power will be restored. The proposed architecture ensures that the missing information from the affected group due to the power outage will eventually be retrieved correctly from other intact groups. The additional SEL protection unit can be designed using existing methods [26] and is outside the scope of this work; therefore, it is not discussed herein.

In the following section, we demonstrate categorically that the proposed SCL architecture is SEL/SEU-resistant and can recover fully from transient errors without causing incorrect outputs or deadlock.

3.2. Recovering from Single-Event Effects Without Compromising Safety

A multi-stage SCL circuit contains the maximum amount of unique DATA in the pipeline when two consecutive DATA stages are interleaved by one NULL stage. SEL can therefore affect a circuit’s group under two scenarios in the worst case: (1) when the affected group register stores NULL while the preceding stage latches DATA and (2) when it stores DATA while the preceding stage latches NULL. Recovery under both the scenarios is explained herein.

3.2.1. SCL Recovery Under Scenario 1

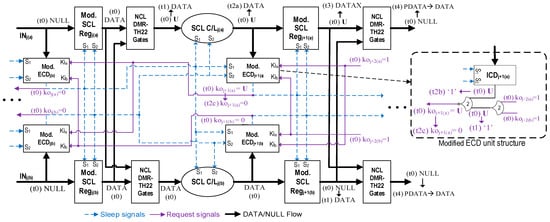

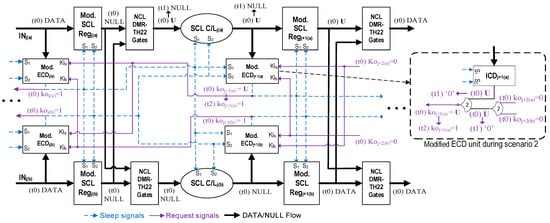

To understand the circuit’s recovery procedure, consider the highlighted NCL DMR-TH22 gates and C/L unit of stagej, as well as the registration and ECD units of stagej+1 in the circuit’s original copy (copy A) (note that any signal that is preceded by the subscript (a) or (b) denotes that it is a part of the original or duplicate copy of the circuit, respectively. This convention will be used throughout the paper) in Figure 5 to be a part of an SEL-affected group that is powered by the same supply. Figure 5 depicts scenario 1, in which the SEL-affected register, Regj+1(a), contains NULL and the preceding stage, stagej, holds DATA prior to disconnecting the power to the highlighted SEL-affected group components.

Figure 5.

SEL recovery procedure without generating incorrect outputs under scenario 1.

At t0, after the error affect has subsided, the group’s power supply is turned back on. At that point, the states of all the gates in that affected group become unknown (U), i.e., the internal gates may be holding logic 1, logic 0, or a voltage in between. However, the matching registers of the duplicated circuit, Regj+1(b), latch the correct NULL; hence, the NCL DMR-TH22 gates in stagej+1 will not permit the unknown values to propagate further. At t1, the outputs of the impacted stage’s NCL DMR-TH22 gates will eventually be rectified using the correct DATA inputs from the unaffected registers of the prior stage. Concurrently, the newly added NCL TH22 gate within the modified ECDj+1(a), which receives correct requests from the subsequent unaffected stage (koj+2(a) and koj+2(b)), will evaluate to logic 1. The C/Lj(a) unit completes the computation of the correct DATA at t2a. The ICDj+1(a) component of the affected ECDj+1(a) will evaluate to logic 1 at t2b, indicating the detection of a complete DATA, followed by correcting the output koj+1(a) to be rfn (i.e., logic 0) at t2c. At t3, Regj+1(a) may become DATAX, which indicates that one rail is asserted correctly by the correct DATA and the other rail is either asserted or partially asserted (i.e., X). In that case, the NCL DMR-TH22 gates at the Regj+1 outputs would allow the correct (matched) rails to flow, as they would be asserted in both copies of the circuit. The other rails (i.e., mismatched rails) would be de-asserted in the duplicate circuit while asserted (or partially asserted) in the original circuit, preventing them from flowing through the NCL DMR-TH22 gates. Consequently, at t4, the correct DATA will be recovered at the output of the NCL DMR-TH22 gates at stagej+1. The DATAX will eventually be flushed when the Regj+1(a) is put to sleep, and the circuit will recover to its correct functionality.

3.2.2. SCL Recovery Under Scenario 2

Figure 6 illustrates the recovery procedure when the affected register latches a DATA prior to SEL (scenario 2). Like the previous scenario, the gates within the affected group components will be in unknown (U) states after reconnecting the supply. Since the register of the duplicate circuit contains the intact DATA, the NCL DMR-TH22 gates of stagej+1 will block the unknown values, thereby preserving the correct DATA at the next stage. At t1, the correct and unaffected ko signals from the preceding stage (koj(a) = koj(b) = 1) will put the gates in the C/Lj(a) and ICDj+1(a) units to sleep. Hence, the correct NULL will be recovered in stagej. The corrected NULL along with the intact ko signals from the subsequent stage will eventually change the ECDj+1(a) to output the correct rfd signal (i.e., koj+1(a) = 1) at t2. This will set the next stage to NULL and flush the unknown values at the output of Regj+1(a), restoring circuit functionality.

Figure 6.

SEL recovery procedure without generating incorrect outputs under scenario 2.

3.3. Recovering from Single-Event Effects Without Compromising Liveness

In the SCL system, a register allows a new DATA at its input to propagate only after the subsequent stage has detected the previous NULL and is rfd (request for data). The next stage should not change the request to rfn (request for null) before the complete DATA gets propagated to the inputs of its own stage registers (case 1). Similarly, a stage is slept to NULL only when a NULL has been detected at the input of the register in that stage and the subsequent stage is rfn (case 2). A deadlock should not occur if this order of action is preserved. It has been established previously in Section 2.2 that the violation of case 1 can causes a deadlock in the SCL pipeline. Herein, we show how our proposed design prevents a premature null request generated by SEU/SEL from causing a circuit deadlock.

Consider the same corner scenario from Section 2.2, as depicted in Figure 7. At t0, C/L units in both copies are still being evaluated based on the new DATA; thus, both Regj+1(a) and Regj+1(b) have PDATA as their inputs. Both next stage detection units are rfd (i.e., koj+1(a) = koj+1(b) = 1), and Regj in both copies of the circuit have the next NULL at their inputs. At t1, due to an error in the original circuit, koj+1(a) gets corrupted and prematurely becomes rfn (i.e., logic 0). However, that erroneous request will not be able to affect the output of the modified ECDj units due to the newly added NCL TH22 gate and the intact koj+1(b) signal from the duplicate copy (refer to the modified ECD’s internal structure in Figure 5 and Figure 6). Therefore, stagej will not be slept by the incorrect request, and eventually, the C/Lj of both copies will evaluate to complete DATA at t2a. The ICDj+1(a) unit within the ECDj+1(a) unit will subsequently evaluate to logic 1 based on the complete DATA. At this point (t2b), the logic 0 output of koj+1(a) is the correct value, and the circuit will move forward as expected. Note that when koj+1(a) becomes rfn prematurely, it wakes up Regj+1 in both copies, which latch the PDATA and propagate that to stagej+1. However, PDATA propagation does not pose a problem [8]. The complete DATA will eventually be available at stagej+1 at t3.

Figure 7.

SEL recovery procedure without causing deadlock.

Another scenario is that ECDj(a) gets corrupted and prematurely generates the sleep signal for stagej components, while the complete DATA is unavailable at the inputs of Regj+1(a) and koj+1(a) is still rfd (case 2 violation). In the proposed architecture, each SCL gate and register is modified to accept two sleep signals, allowing them to sleep only when both signals are logic 1. Therefore, an incorrect sleep request generated by a corrupted copy (i.e., koj(a) = 1) will be unable to sleep stagej components as the uncorrupted duplicate circuit will still hold the correct request (i.e., koj(b) = 0). Eventually, the koj(a) value will be corrected once ECDj+1 detects the complete DATA, getting the circuit back to its correct functionality.

4. Simulation Results

Multiple multistage resilient SCL unsigned array multipliers were modeled in Verilog HDL based on the proposed architecture in Figure 3. The SEL protection hardware was not implemented; however, the various probable effects of SEL/SEU were simulated. The circuit functionality and recovery procedure were validated for each simulated scenario.

4.1. DMR-NCL vs. DMR-SCL: Performance Evaluation and Comparison

A single-stage non-pipelined version of the resilient SCL (umult 4 × 4), (umult 8 × 8), and (umult 10 × 10) unsigned array multipliers were designed based on our proposed architecture at the transistor level using a high-performance CMOS predictive technology model (PTM) at 32 nm [27]. DMR-NCL [17]-based versions of the three NCL multipliers were also implemented for performance comparison. Note, the C/L units of both DMR-NCL and our proposed resilient SCL multiplier were kept identical, i.e., comprising the same number of gates and adder components, for a fair comparison. Our resilient SCL version of the designs utilized transistors with two different threshold voltages (VT) as per [8,9] whereas, the NCL multipliers were designed with all low-VT transistors. The results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Simulation results.

The circuits are compared based on four performance parameters: the DATA-to-DATA propagation delay within the pipeline (TDD), power dissipation during idle stages, average energy utilization per operation, and transistor count. As the designs are not pipelined, TDD indicates the time interval between two consecutive DATA sets when they are ready to propagate, i.e., the interleaving NULL propagation time is also considered [18]. Compared to the resilient NCL version, the proposed resilient SCL multiplier implementation required ~20% fewer transistors and consumed 2.4 times less energy per operation on average. The idle power dissipation was reduced to almost one-third in the proposed design. However, our design had 1.3 times latency overhead compared to its NCL counterpart. For the implementation, the proposed SCL version utilized ~12% fewer transistors and achieved an average energy consumption reduction of 1.7 times per operation. Idle power dissipation was nearly halved compared to the NCL counterpart, with a modest increase in latency by a factor of 1.3×.

Similarly, the proposed resilient SCL multiplier required ~11% fewer transistors and consumed 1.8 times less energy per operation on average. Idle power dissipation was reduced by a factor of approximately 2.5 times. However, like the other multipliers, the proposed SCL design exhibited a latency overhead of 1.4 times compared to the resilient NCL version.

We have the following observation from the simulation results:

- DMR-NCL circuits have an area overhead compared to DMR-SCL circuits. This is because NCL gates require more transistors than the modified DMR-SCL gates with two sleep inputs. Also, DMR-NCL register structures require more transistors than DMR-SCL registers. Therefore, for pipelined implementations, the area savings in DMR-SCL will be even more than DMR-NCL.

- DMR-NCL requires the propagation of a complete NULL wavefront through all the C/L, registers, and completion components in a stage after a DATA propagation, whereas the DATA-to-NULL transition in DMR-SCL is achieved through sleep inputs without the need for a separate NULL wavefront propagation. This results in much fewer switching activities during the NULL transition, reducing the overall energy utilization. In addition, the SCL gates are more energy-efficient due to the integration of MTCMOS technology, which further reduces the energy utilization.

- Despite requiring theoretically less time in the DATA-to-NULL transition, the latency overhead of DMR-SCL circuits has been found to be more than that of DMR-NCL circuits in our simulation. This can be attributed to the inclusion of high-threshold transistors in the SCL gates, resulting in slower switching compared to NCL gates. The speed of the DMR-SCL operation can be further enhanced by determining the optimal transistor sizing and threshold voltage. Also note that the circuits in Table 1 are not pipelined. In finer pipelined implementations, the latency of DMR-NCL is anticipated to have more overhead due to the propagation of the NULL wavefront across all stages [17].

- The integration of MTCMOS technology results in a substantial reduction in leakage in DMR-SCL circuits compared to DMR-NCL circuits, rendering them appropriate for applications that remain idle for an extended period.

4.2. DMR-SCL vs. SCL: Analysis of Overhead

DMR-SCL circuits have significant area overhead compared to their traditional SCL implementations. To conduct an area and energy overhead analysis, we design an SCL version of the for comparison with the equivalent DMR-SCL version. The non-pipelined SCL requires 1834 transistors compared to the equivalent DMR-SCL version that requires 4072 transistors (i.e., 2.22× overhead). This is because, in DMR-SCL, the original SCL circuit gets doubled, additional NCL TH22 gates are added after registration, one additional TH22 gate is added per ECD, and two transistors are added in all SCL gates and register components to accommodate the two sleep signals. Note that the pipelined implementations will have a greater overhead, depending on how finely grained the pipelined stages are.

As mentioned earlier, TDD is the time taken for a stage to finish computation based on a DATA front and resetting to NULL after computation, before accepting the next DATA front. Inverse of TDD gives throughput. In terms of gate/component delays, for all ‘j’ stages, the DMR-SCL circuit’s delay can be computed as,

where is the time taken by the stage’s register to latch the new DATA, requires one-gate delay as there is one level of NCL TH22 gates after registration in each stage, is the C/L unit’s gate delay, is the completion detection unit’s gate delay to detect the DATA at the input of Regj+1 and de-assert the sleep signal of stagej+1 so that Regj+1 can latch the data, is the time taken to put stagej to NULL, where , is the time taken by the completion detection unit in stagej to assert the stage’s sleep signal and is the time taken to put gates to sleep after sleep is asserted. In contrast, the SCL circuits’ delay, for all ‘j’ stages, can be computed as

The critical path of SCL will experience a one-gate delay reduction due to the absence of NCL TH22 gates following the registers. Additionally, the completion components will experience a one-gate delay reduction as the additional TH22 gate in DMR-SCL will not be necessary. For finely grained pipelined implementation, the TDD overhead in DMR-SCL will be greater compared to traditional SCL. Additionally, there will be more redundant switching in the DMR-SCL circuit compared to SCL, resulting in higher energy per operation. For instance, the non-pipelined SCL circuit requires ~25% less energy per operation (~53 fJ) compared to the equivalent DMR-SCL version (66.3 fJ). Note, for pipelined implementations, switching energy overhead will be greater in DMR-SCL.

5. Verification Framework for the SEL/SEU-Resistant SCL Architecture

QDI asynchronous circuits are generally synthesized from their corresponding synchronous specifications utilizing design automation tools. During the process, the circuit undergoes substantial modification, resulting in an implementation that differs significantly from the specification [28,29,30,31,32]. Similar techniques can be employed with a few modifications to synthesize resilient SCL circuits based on the proposed architecture. Equivalence verification is one of the most widely utilized formal methods, which is utilized to guarantee functional correctness and equivalence of logic values between two structurally different specification and implementation components [33,34,35,36,37,38]. We formalize a verification framework for the proposed architecture based on equivalence checking, which can verify the safety as well as liveness of the synthesized error-resilient SCL (DMR-SCL) circuits. Our proposed verification methodology requires two steps. In the first step, our developed verification tool conducts structural abstraction and verifies only the functional correctness of the DMR-SCL circuits. In the second step, we implement a directed graph-based method that verifies all handshaking connections in the circuit, assuring that the four-phased QDI control protocol is maintained. The steps are detailed below.

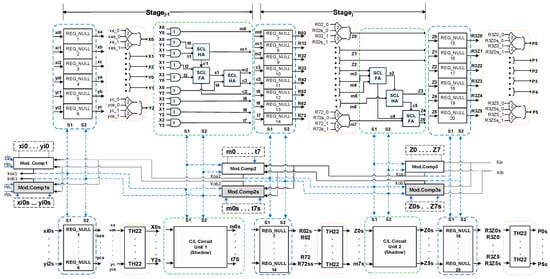

5.1. Safety Check Procedure

A two-stage 3 × 3 DMR-SCL unsigned multiplier based on the proposed architecture is designed as an example circuit to illustrate the safety check procedure, as shown in Figure 8. According to our proposed architecture depicted in Figure 3, there are two copies of the multiplier, one original and one duplicate (highlighted in gray), implementing the output function . Both the original and duplicate circuits are identical, and therefore, the complete structure of the duplicate circuit is not shown in the figure. The inputs and outputs of both the actual and duplicate circuits are dual rails. All the SCL functions comprising the multiplier, i.e., the AND, Half Adder (HA), Full Adder (FA), accommodate two sleep signals as inputs, one from each copy. Each copy of the multiplier circuit contains three sets of registers, input registers, output registers, and intermediate registers, which are all reset to NULL (REG_NULL). Note that the circuit can be designed with only the input and output registers; however, an intermediate register is added to make the circuit more generic and better explain each step of the procedure. Slpa and Slpb are the external sleep inputs for the ECD components in the first stage, and the Kia and Kib are external request signals for the ECD components in the last stage.

Figure 8.

DMR-SCL 3 × 3 unsigned multiplier.

Table 2 displays the netlist structure of the DMR-SCL 3 × 3 multiplier, which will be referred to as SCLInitial. This netlist structure is generated from the circuit’s RTL level description in Verilog HDL and is fed as an input to our safety check tool. The primary inputs and primary outputs of both the original and duplicate circuits are listed in lines 1 and 2, respectively. Following a dual-rail variable, the extensions ‘_0’ and ‘_1’ correspond to the variable’s rail0 and rail1 signals, respectively. The absence of the rail extensions indicates a single rail signal. Lines 3–26 correspond to the NCL DMR-TH22 threshold gates in the first stage. Each NCL DMR-TH22 threshold gate is represented in the netlist in the following manner: the first column specifies the gate_type, the second column lists the gate inputs separated by commas, and the final column specifies the gate output.

Table 2.

Netlist structures of the initial and converted DMR-SCL circuit.

The SCL threshold gates in the C/L units are also represented in a similar manner; the first column corresponds to the gate_type, the second column specifies the gate inputs separated by commas, the third column indicates the two sleep inputs per gate in a comma separated format, and the final column indicates the gate output. Lines 167–206 correspond to dual-rail SCL registers, where the first column indicates the reset_type of the registers (i.e., reset to NULL, DATA0, or DATA1), the second column signifies the register level, with level 1 indicating an input register, the third and fourth columns correspond to the rail0 and rail1 data inputs, respectively, and the fifth column corresponds to the two sleep inputs in a comma separated format, followed by the rail0 and rail1 data outputs in the last two columns. The register level indicates the depth of the path through registers, excluding the C/L in between, which is determined by backtracking every register input. In the 3 × 3 DMR SCL multiplier example, there are three stages of registers with levels 1, 2, and 3, starting from the input registers. Lines 207–212 are the early-completion detection or the ECD units, where ECDn in the first column denotes an early-completion component with ‘n’ being a unique identifier, the second column indicates the inputs in a comma separated format, the third and fourth columns are the Ki request inputs and the sleep inputs in comma separated format, respectively, and the last column is the ECD output. Note that this DMR-SCL netlist in Table 2 is generated by processing the original gate level DMR-SCL Verilog HDL description to order the components as described above and to combine all the completion unit threshold gates into one single ECD module per stage. Each ECD module, such as ECD1, comprises SCL TH24comp/TH12 gates in the first level, a series of THnn SCL gates arranged in a tree structure, one inverting and one non-inverting the NCL TH22 gate.

The SCLInitial netlist is then input to a python-based automated tool that we have developed. The netlist undergoes a conversion algorithm that converts the SCLInitial netlist into an equivalent Boolean netlist, which will be referred to as SCLBool, as shown in Table 2. During the conversion, the reset-to-NULL registers (Reg_NULL) and early-completion units (ECDn) are eliminated because they are only used for control and synchronization and do not impact the functionality. Note that the connection between registers and completion units will be verified as a part of the liveness check, as illustrated later.

Each NCL DMR-TH22 threshold gate gets replaced with their equivalent Boolean SET function without hysteresis. Sleep inputs are removed from the SCL threshold gates. Since SCL threshold gates do not have hysteresis, the equivalent Boolean SET function is similar to the original SCL function without the sleep inputs. Each primary dual-rail input signal is substituted with its matching rail1, as shown in line 1 in SCLBool, because only rail1 of a dual-rail signal is equivalent to its respective Boolean value. Line 2 in the converted netlist corresponds to the primary outputs of both the original and duplicate circuits, which includes both the rails of the output signals. Lines 3 through 14 of the converted netlist contain a collection of inverters that are added to generate signals equivalent to the removed rail0 inputs. As the functionality check only verifies the correct DATA computation, this is carried out to eliminate the need for the NULL spacer and improve the scalability of the process.

The converted Boolean netlist, SCLBool, is then compared against a Boolean specification function (FBool_Spec). The converted netlist is first encoded in the Satisfiability Modulo Theory Library (SMT-LIB) language [39] using an automated encoding algorithm that we have developed, which is then input to the Z3 SMT solver [40] to check for equivalence between the converted Boolean netlist and the specification. To verify the functionality of any DMR-SCL circuit, we check the following generic proof obligation.

Proof Obligation 1 (PO1).

Safety Check

- P1:

- P2: (,…, ) = SCLBoolStep

- P3: (,…, ) = SCLBoolStep

- P4:

- P5:

- PO1a:

- PO1b:

□

The proof obligation, PO1, indicates that for a converted equivalent Boolean DMR-SCL circuit with q original circuit (A) inputs and q duplicate circuit (B) inputs , k SCL gates for the original and duplicate circuits (, …,) and (, …,), respectively, and l original circuit outputs ( and l duplicate circuit outputs (), if the inputs to the original copy A and duplicate copy B of the circuits are the same, then after each step of the circuit’s execution, the rail1 of the outputs of both the copies should match the corresponding Boolean specification (PO1a). In the case of the 3 × 3 DMR-SCL multiplier, this implies that if , then , where the ‘s’ on the variable name indicates that the variable is from the shadow/duplicate copy, <R1> corresponds to rail1 of a variable, and MULT corresponds to the Boolean multiplication function as the specification. In this verification step, only the rail1 outputs need to be checked, as these correspond to the Boolean specification circuit outputs. However, we also need to check the rail0 signals. The rail0 outputs are verified using the proof obligation b (PO1b), which ensures that if the inputs to the original copy A and duplicate copy B of the circuits are identical, then after each step of the circuit’s execution, the rail0 of the outputs of both the copies should be complimentary to that of their corresponding rail1 values. Note that although we utilize the Z3 SMT solver for equivalence checking, other combinational equivalence checkers could also be used for the proposed safety check.

5.2. Handshaking and Liveness Check Procedure

QDI principles and handshaking protocols guarantee the circuits’ forward progress [41,42]. The request acknowledgment-based progression in QDI circuits ensures that each handshake operation proceeds without indeterminate stalling, resulting in a deadlock-free operation [41]. In addition, the event-driven nature of QDI circuits and the four-phased return-to-zero protocol ensure that each communication phase is completed prior to the commencement of the subsequent phase, thereby avoiding indefinite transition cycles and oscillation that cause livelock [41]. In this step of our proposed verification scheme, every possible connection between different circuit components in the circuit is exhaustively verified using our custom-developed handshaking and liveness check procedure. The procedure guarantees the absence of illegal connections that could potentially result in the violation of the four-phased handshaking protocol and cause a deadlock or a livelock. Due to the interdependence between multiple stages, multiple feedback paths, and the presence of two copies within a circuit, the handshaking connections in DMR-SCL circuits are significantly complex. We developed a directed graph-based method for validating all the connections between registers, ECD units, C/L gates, and DMR-NCL TH22 gates. Our python-based tool takes the initial DMR-SCL netlist, SCLInitial, as input and converts it into a graph structure using existing libraries, where each register, gate, and completion components is modeled as a node. The algorithm then traverses the graph and assigns stage values to all the circuit components. Stages are identified in the following manner: each primary input is assumed to be in stage 0, the level column of each register corresponds to their stage values, and the C/L and NCL DMR-TH22 gates are assigned to the stage value of their predecessor registers by backtracking the gate outputs. Consider a DMR-SCL circuit where each copy comprises #N SCL 1-bit registers, #C ECD units, #T DMR-NCL TH22 gates, #G C/L gates, #I dual-rail primary inputs, #O dual-rail primary outputs, one external request input (ki), one external sleep input, and one global reset for initializing the registers. There is a large set of possible connections between the different units in each stage; however, only a few of those are valid as per the four-phased handshaking protocol. For instance, a 1-bit register has four distinct ports: one dual-rail data input port, one dual-rail data output port, and two sleep input ports (refer to Figure 3). The dual-rail data input of a register in a particular stage of copy A can have the following valid connections: (i) each of the two input rails can be derived from C/L gate outputs from the preceding stage in copy A; (ii) each rail of the register input can be derived from an NCL DMR-TH22 output from the preceding stage in copy A; (iii) the dual-rail input can be connected to copy A’s primary inputs (in the case of input registers); and (iv) each rail of the dual-rail register input should be associated with the same variable. The sleep inputs of a register in a particular stage of copy A can only be connected as follows: the two sleep signals must come from the ECD units of the same stage, one from each copy. The dual-rail data output of a register in a particular stage of copy A can have the following valid connection: each register output rail must be connected to two NCL DMR-TH22 gates in the same stage, one in copy A and one in copy B.

Similarly, an ECD unit in each copy has #n dual-rail data input ports, two sleep input ports, two Ki request input ports, and one Ko output port. There are numerous connection possibilities, of which only the following are valid: (i) An ECD unit, except the one in the first stage, should obtain its two sleep input signals from the ECD units in the previous stage, one from each copy of the circuit. (ii) A first-stage ECD unit should obtain its two sleep signals from the external sleep inputs. (iii) An ECD unit, except the one in the last stage, should receive its two Ki request inputs from the ECD units in the succeeding stage, one from each copy of the circuit. (iv) A last-stage ECD unit should receive its two Ki request inputs externally. (v) Each stage’s ECD unit’s data inputs must be exactly same as for the stage’s register’s data inputs (refer to Figure 3). In other words, an ECD unit of a given stage in a copy must receive all the same stage register’s inputs in the same copy as its data inputs, and no additional data inputs should be present. (vi) The Ko output of an ECD unit can be only connected to the sleep inputs of the C/L gates and register units in the same stage in both copies, the Ki request inputs of the ECD units in the preceding stage in both copies, and the sleep inputs of the ECD units in the subsequent stage in both copies. In case of the C/L units, it is verified that there is no signal sharing between the two copies of the circuit and/or between two stages within the circuit. This implies that a C/L gate in copy A of the circuit cannot be connected to any other component in copy B. Similarly, the output of a gate in stagej cannot be directly connected to another C/L gate in stagei where j ≠ i. Note that many of the incorrect connections within the C/L units will also be detected in the safety check, as discussed in the prior subsection.

6. Verification Results and Discussion

To demonstrate the performance of the proposed verification methodology, we have designed multiple DMR-SCL unsigned array multipliers and utilized them as benchmark circuits, as shown in Table 3. Since the gate level and complexity of array multipliers increase exponentially with the width, multiplier circuits of varying widths were chosen to demonstrate the scalability of the proposed method. umultN represents an unsigned multiplier. Note that all multipliers except the umult3 are non-pipelined. The umult3 contains two pipeline stages as shown in Figure 8. The verification is performed on an Intel Core i7 10th generation CPU with a 16GB RAM and 64-bit operating system. The safety check (Z3 SMT Solver runtime) and the liveness and handshaking check timings are recorded in Table 3. Note that the liveness time is the runtime of our liveness and handshake check algorithm, which includes the graph conversion. Table 4 lists the runtimes for SCLInitial-to-SCLBool netlist conversion and SCLBool-to-SMT conversion for all the test circuits.

Table 3.

Verification results for various combinational DMR-SCL circuits.

Table 4.

Netlist conversion and SMT generation runtimes.

Given that umult10 is the largest test circuit, several bugs were injected into it to demonstrate the method’s scalability and efficiency. umult10-B1 represents a buggy 10-bit multiplier with one or more incorrect gate mappings, for example, incorrectly assigning a TH12 gate to a logic function in place of a TH22 gate. umult10-B2 and umult10-B3 correspond to swapped rail errors, where the rail0 and the rail1 of a gate (or multiple gates) are swapped. Both types of bugs are very common during automated synthesis, which will be caught by the safety check procedure, as denoted by (B) in the table. umult10-B4 through umult10-B7 correspond to one or multiple incorrect request and sleep connections between the ECD units, registers, and the gates in the SCL C/L units. umult10-B8 corresponds to a bug in one or more NCL DMR-TH22 gates, including not receiving the same rails of the same variable from both copies, receiving both inputs from the same copy, and/or receiving inputs from two separate variables. These bugs will be detected both through the safety check and liveness and handshaking check procedure, as shown in Table 3. If the safety check fails, the Z3 SMT solver generates counterexamples. If the liveness check fails, the tool generates error messages that are descriptive and indicate the precise error location to facilitate easier debugging.

Since the DMR-SCL architecture is newly proposed, there is currently no existing verification framework for such circuits, suggesting that there are no comparison points. Nevertheless, to demonstrate the superior scalability of our proposed method, we conduct an analytical comparison of our work with two existing QDI verification schemes: a model checking-based verification framework for PCHB circuits [43] and a well-founded equivalent bisimulation (WEB)-based equivalence scheme for NCL circuits [36]. Both [36,43] rely on modeling the QDI circuit as transition systems. However, the non-deterministic nature of such circuits results in a state-space explosion for considerably smaller circuits. To circumvent this issue, our method performs an initial structural abstraction, which results in significantly improved scalability. It is important to note that our verification scheme validates duplicated SCL circuits, whereas [36,43] validate traditional non-duplicated NCL and PCHB circuits, respectively. Despite this, our technique can verify even bigger circuits in a considerably reduced time, as demonstrated by our findings and those from [36,43].

However, there are certain limitations in our proposed scheme. Currently, the proposed verification scheme is applicable to any combinational DMR-SCL circuits. The method can be easily tailored to verify sequential DMR-SCL circuits that lack interactive data feedback paths, such as a multiply and accumulate (MAC) circuit, due to the straightforward register mapping between the converted synchronous/Boolean netlists and the original specification circuits. However, for any arbitrary sequential DMR-SCL circuits with interactive feedback paths, a more complicated mapping algorithm will be required. Furthermore, the datapath feedback will also result in a more complicated handshaking network. We intend to address these limitations in the future as well as explore commercial equivalence checkers, such as Jasper Gold Sequential Equivalence Checker (SEC), Cadence Encounter Conformal EC, etc., instead of an SAT solver, to further improve the scalability and verify much larger benchmarks.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

A duplication-based radiation-hardened QDI asynchronous SCL circuit design methodology, DMR-SCL, was presented in this paper. It was analytically proven that the proposed design can recover from single-event effects (SEL/SEU) without causing deadlock and/or incorrect outputs. Three resilient DMR-SCL array multipliers of varying widths () were implemented at the transistor level using a 32 nm CMOS PTM based on the proposed architecture. Compared to an existing duplication-based NCL version, our proposed resilient SCL implementations required much fewer transistors, demonstrated substantial energy savings per operation, and dissipated significantly less power during idle phases. However, the improvements were achieved at the cost of increased latency.

A formal verification framework for the proposed DMR-SCL architecture was also presented. For industrial adoption, DMR-SCL circuits are expected to be synthesized from their synchronous counterparts using design automation tools. During the synthesis process, the circuit will undergo several transformations, which increases the likelihood of incorrect connections during the synthesis process. We demonstrate that our proposed verification scheme can validate the functional correctness, deadlock-free, and livelock-free operation of the synthesized DMR-SCL circuits. The scalability of the procedure was demonstrated by utilizing a variety of multiplier benchmark circuits with varying widths.

There are a few opportunities for the further development of this work, as mentioned below:

- The proposed DMR-SCL architecture, in its current form, cannot handle concurrent multi-event upsets (MEUs). For example, a deadlock may still occur if both ECD outputs of a specific stage (original and duplicate) are corrupted simultaneously. However, the proposed architecture can be modified to tackle MEUs, which is an area of future research.

- Extensive simulations ensure that the proposed DMR-SCL architecture can mitigate the single-event effects correctly. A hardware implementation with a proper experimental setup would be beneficial to test the architecture in the presence of radiation.

- The proposed verification scheme is directly applicable to the verification of any combinational DMR-SCL circuits, as discussed in Section 6, and, with minor modifications, can be used to verify sequential DMR-SCL circuits without interactive feedback loops. However, this method would require advanced register mapping algorithms to be applicable to verify any arbitrary sequential DMR circuits with interactive loops, which will be addressed in our future research.

- In place of an SAT solver, we intend to utilize commercial equivalence checkers (e.g., Jasper Gold SEC) to enhance the scalability of the verification method and validate larger sequential benchmarks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D. and A.A.S.; methodology, M.D. and A.A.S.; software development, A.C.B.; validation, M.D., D.M. and A.A.S.; formal analysis, M.D., A.A.S. and D.M.; investigation, M.D. and D.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.D.; writing—review and editing, A.A.S.; supervision, A.A.S.; project administration, A.A.S.; funding acquisition, A.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) under Grant No. CCF-2153373.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| QDI | Quasi-delay-insensitive (QDI) |

| NCL | Null Convention Logic |

| SCL | Sleep Convention Logic |

| SEU | Single-event upset |

| SEL | Single-event latch-up |

| SEE | Single-event effect |

| EMI | Electromagnetic Interference |

| MTNCL | Multi-threshold NCL |

| MTCMOS | Multi-threshold complementary metal oxide semiconductor |

| ICD | Internal completion detection |

| ECD | Early-completion detection |

| TMR | Triple-modular redundancy |

| DMR | Dual-modular redundancy |

| ECC | Error correcting code |

| SMT | Satisfiability Modulo Theory |

References

- Baumann, R. Soft errors in advanced computer systems. IEEE Des. Test Comput. 2005, 22, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, P.E.; Massengill, L.W. Basic mechanisms and modeling of single-event upset in digital microelectronics. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2003, 50, 583–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoga, M.; Binder, D. Theory of single event latchup in complementary metal oxide semiconductor circuits. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 1986, 33, 1714–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, C.; Emer, J.; Mukherjee, S.S.; Reinhardt, S.K. Techniques to reduce the soft error rate of a high-performance microprocessor. ACM SIGARCH Comput. Archit. News 2004, 32, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakib, A.A. Soft error tolerant quasi-delay insensitive asynchronous circuits: Advancements and challenges. In Proceedings of the 34th SBC/SBMicro/IEEE/ACM Symposium on Integrated Circuits and Systems Design (SBCCI), Campinas, Brazil, 23–27 August 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Fant, K.M.; Brandt, S.A. Null convention logic: A complete and consistent logic for asynchronous digital circuit synthesis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Application Specific Systems, Architectures and Processors: ASAP’96, Chicago, IL, USA, 19–21 August 1996; pp. 261–273. [Google Scholar]

- Di, J.; Smith, S.C. (Eds.) Asynchronous Circuit Applications; IET: Stevenage, UK, 2019; Available online: https://digital-library.theiet.org/content/books/cs/pbcs061e (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Zhou, L.; Parameswaran, R.; Parsan, F.A.; Smith, S.C.; Di, J. Multi-Threshold NULL Convention Logic (MTNCL): An ultra-low power asynchronous circuit design methodology. J. Low Power Electron. Appl. 2015, 5, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.C.; Di, J. Designing Asynchronous Circuits Using NULL Convention Logic (NCL); Morgan & Claypool: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Smith, S.C.; Di, J. Bitwise MTNCL: An ultra-low power bit-wise pipelined asynchronous circuit design methodology. In Proceedings of the 53rd IEEE International Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems, Seattle, WA, USA, 1–4 August 2010; pp. 217–220. [Google Scholar]

- Alzahrani, A.; Bailey, A.D.; Fu, G.; Di, J. Glitch-Free Design for Multi-Threshold CMOS NCL Circuits. In Proceedings of the ACM 2009 Great Lakes Symposium on VLSI, Boston, MA, USA, 10–12 May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Khodosevych, D.; Sakib, A.A. Evolution of NULL convention logic based asynchronous paradigm: An overview and outlook. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 78650–78666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.C. Speedup of Self-Timed Digital Systems Using Early Completion. In Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Annual Symposium on VLSI, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 25–26 April 2002; pp. 107–113. [Google Scholar]

- Kao, J.T.; Chandrakasan, A.P. Dual-threshold voltage techniques for low-power digital circuits. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2000, 35, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Sakib, A.A.; Srinivasan, S.K.; Smith, S.C. An equivalence verification methodology for asynchronous sleep convention logic circuits. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Sapporo, Japan, 26–29 May 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Kuang, W.; Zhao, P.; Yuan, J.S.; DeMara, R.F. Design of asynchronous circuits for high soft error tolerance in deep submicrometer CMOS circuits. IEEE Trans. Very Large-Scale Integr. (VLSI) Syst. 2010, 18, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Smith, S.; Di, J. Radiation Hardened NULL Convention Logic Asynchronous Circuit Design. J. Low Power Electron. Appl. 2015, 5, 216–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, R.E.; Vanderkulk, W. The use of triple-modular redundancy to improve computer reliability. IBM J. Res. Dev. 1962, 6, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, W.; Martin, A.J. SEU-tolerant QDI circuits [quasi delay-insensitive asynchronous circuits]. In Proceedings of the 11th IEEE International Symposium on Asynchronous Circuits and Systems, New York, NY, USA, 14–16 March 2005; pp. 156–165. [Google Scholar]

- Lodhi, F.K.; Hasan, O.; Hasan, S.R.; Awwad, F. Modified null convention logic pipeline to detect soft errors in both null and data phases. In Proceedings of the IEEE 55th International Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems (MWSCAS), Boise, ID, USA, 5–8 August 2012; pp. 402–405. [Google Scholar]

- Lodhi, F.K.; Hasan, S.R.; Hasan, O.; Awwad, F. Analyzing vulnerability of asynchronous pipeline to soft errors: Leveraging formal verification. J. Electron. Test. 2016, 32, 569–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, W.; Martin, A.J. Soft-Error Tolerant Asynchronous FPGA. In Proceedings of the Dependable System and Network 2005, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 22–25 June 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, W.; Martin, A.J. A soft-error-tolerant asynchronous microcontroller. In Proceedings of the 13th NASA Symposium on VLSI Design, Post Falls, ID, USA, 4–5 June 2007; Citeseer: University Park, PA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Datta, M.; Bodoh, A.; Sakib, A.A. Error Resilient Sleep Convention Logic Asynchronous Circuit Design. In Proceedings of the 2023 21st IEEE Interregional NEWCAS Conference (NEWCAS), Edinburgh, UK, 26–28 June 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, D.E. Asynchronous logics and application to information processing. In Proceedings of the Symposium on the Application of Switching Theory to Space Technology, Sunnyvale, CA, USA, 27–28 February 1962; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 1962; pp. 289–297. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaidis, M.; Torki, K.; Natali, F.; Belhaddad, F.; Alexandrescu, D. Implementation and validation of a low-cost single-event latchup mitigation scheme. In Proceedings of the IEEE Workshop on Silicon Errors in Logic–System Effects (SELSE), Stanford, CA, USA, 24–25 March 2009. [Google Scholar]

- CMOS PTM HP Model. Predictive Technology Model, Arizona State University. Available online: http://ptm.asu.edu (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Ligthart, M.; Fant, K.; Smith, R.; Taubin, A.; Kondratyev, A. Asynchronous design using commercial HDL synthesis tools. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Symposium on Advanced Research in Asynchronous Circuits and Systems (ASYNC 2000) (Cat. No. PR00586), Eilat, Israel, 2–6 April 2000; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 114–125. [Google Scholar]

- Kondratyev, A.; Lwin, K. Design of asynchronous circuits by synchronous CAD tools. In Proceedings of the 39th annual Design Automation Conference, New York, NY, USA, 10 June 2002; pp. 411–414. [Google Scholar]

- Reese, R.B.; Smith, S.C.; Thornton, M.A. Uncle-an rtl approach to asynchronous design. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE 18th International Symposium on Asynchronous Circuits and Systems, Kgs. Lyngby, Denmark, 7–9 May 2012; pp. 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, M.T.; Beerel, P.A.; Sartori, M.L.; Calazans, N.L. NCL synthesis with conventional EDA tools: Technology mapping and optimization. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2017, 65, 1981–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodosevych, D.; Bodoh, A.C.; Sakib, A.A.; Smith, S.C. Combining relaxation with NCL_X for enhanced optimization of asynchronous Null convention logic circuits. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 104688–104699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakib, A.A.; Smith, S.C.; Srinivasan, S.K. Formal modeling and verification of PCHB asynchronous circuits. IEEE Trans. Very Large-Scale Integr. (VLSI) Syst. 2019, 27, 2911–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakib, A.A.; Smith, S.C.; Srinivasan, S.K. An equivalence verification methodology for combinational asynchronous PCHB circuits. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 61st International Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems (MWSCAS), Windsor, ON, Canada, 5–8 August 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 767–770. [Google Scholar]

- Sakib, A.A.; Le, S.; Smith, S.C.; Srinivasan, S.K. Formal verification of NCL circuits. In Asynchronous Circuit Applications; IET: Stevenage, UK, 2018; pp. 309–338. Available online: https://digital-library.theiet.org/content/books/10.1049/pbcs061e_ch15 (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Wijayasekara, V.M.; Srinivasan, S.K.; Smith, S.C. Equivalence verification for NULL Convention Logic (NCL) circuits. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 32nd International Conference on Computer Design (ICCD), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 19–22 October 2014; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 195–201. [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder, D.; Datta, M.; Bodoh, A.C.; Sakib, A.A. A Scalable Formal Framework for the Verification and Vulnerability Analysis of Redundancy-Based Error-Resilient Null Convention Logic Asynchronous Circuits. J. Low Power Electron. Appl. 2024, 14, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, S.N.; Srinivasan, S.K.; Smith, S.C. Exploiting Dual-Rail Register Invariants for Equivalence Verification of NCL Circuits. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 63rd International Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems (MWSCAS), Springfield, MA, USA, 9–12 August 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, C.; Fontaine, P.; Tinelli, C. The SMT-LIB Standard: Version 2.6. Technical Report; Department of Computer Science, The University of Iowa: Iowa City, IA, USA, 2017; Available online: www.SMT-LIB.org (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- de Moura, L.; Bjørner, N. Z3: An efficient SMT solver. In Tools and Algorithms for the Construction and Analysis of Systems (Lecture Notes in Computer Science); Ramakrishnan, C.R., Rehof, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 337–340. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, A.J. Compiling communicating processes into delay-insensitive VLSI circuits. Distrib. Comput. 1986, 1, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.J. The limitations to delay-insensitivity in asynchronous circuits. In Beauty Is Our Business: A Birthday Salute to Edsger W. Dijkstra; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 302–311. [Google Scholar]

- Sakib, A.A.; Smith, S.C.; Srinivasan, S.K. Formal modeling and verification for pre-charge half buffer gates and circuits. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 60th International Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems (MWSCAS), Boston, MA, USA, 6–9 August 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 519–522. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).