Abstract

Internet of Vehicles (IoV) is a concept that combines IoT and vehicular ad hoc networks. In IoV environments, vehicles constantly move and communicate with other roadside units (edge servers). Due to the vehicles’ insufficient computing power, repetitive authentication procedures can be burdensome for automobiles. In recent years, numerous authentication protocols for IoV environments have been proposed. However, there is no study that considers both re-authentication and handover authentication situations, which are essential for seamless communication in vehicular networks. In this study, we propose a chaotic map-based seamless authentication scheme for edge-assisted IoV environments. We propose authentication protocols for initial, handover, and re-authentication situations and analyze the security of our scheme using informal methods, the real-or-random (RoR) model, and the Scyther tool. We also compare the proposed scheme with existing schemes and show that our scheme has superior performance and provides more security features. To our knowledge, This paper is the first attempt to design an authentication scheme considering both handover and re-authentication in the IoV environment.

1. Introduction

Internet of Vehicles (IoV) is a new paradigm that applies Internet of Things (IoT) to vehicular networks [1,2]. IoV can be combined with cloud computing and edge computing to reduce the computational burden on network entities. IoV is considered a key technology to realize high-definition mapping, autonomous driving, and other convenient services. In IoV environments, vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I), vehicle-to-person (V2P), and vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) interactions occur continuously to provide services to drivers. Among these interactions, V2I is the most important and fundamental communication because edge nodes maintain a connection with mobile vehicles and transmit necessary information in real-time.

However, various security attacks can occur in V2I communications. When an adversary is in the network, the adversary can masquerade as a legitimate vehicle or edge node and try to transmit false information to the other party [3,4,5]. Furthermore, an adversary can capture messages transmitted over a wireless channel and try to track the location of a particular vehicle, which can be an invasion of privacy. To prevent these potential threats, designing a mutual authentication protocol for V2I communication is essential to provide reliable autonomous driving services.

In recent years, many authentication schemes have been proposed for secure and efficient communications in edge-assisted IoV networks [6,7,8,9]. Vehicles have much higher mobility than general IoT devices, and handover situations in other regions occur frequently. Moreover, a vehicle is often parked or stopped, and it should re-authenticate with the same edge server (ES) again. If a vehicle repeats the authentication process again, it is inefficient and generates unnecessary computational costs on the ES. Many existing authentication schemes take into account handover, yet they do not handle re-authentication. We are confident that if we can design an authentication protocol by considering the re-authentication situation, the network efficiency would considerably improve. Furthermore, most existing schemes utilize an elliptic curve cryptosystem (ECC), which generates intensive computational costs. Since vehicles perform numerous authentications, the computational costs incurred in authentication needs to be minimized. In this paper, we propose a chaotic map-based seamless authentication scheme for edge-assisted IoV considering both handover and re-authentication situations. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- We propose a chaotic map-based [10] initial authentication scheme for V2I communications. The Chebyshev chaotic map has a lower computational cost than elliptic curve-based authentication. Thus, it can ensure efficient authentication for IoV environments.

- We propose re-authentication and handover authentication schemes to ensure seamless communication in IoV environments. After the initial authentication, the ES stores the pseudo identity of the authenticated vehicle and sets the expiration time. It can lead to authenticating the vehicle quickly during the re-authentication process. In a handover situation, the ES transmits information about the vehicle in advance to the other ES and enables the performance of a quick handover authentication.

- We analyzed the security of our scheme using the Scyther tool and RoR model to show that our scheme can guarantee mutual authentication and session key security. We also compared the proposed scheme with previous schemes in terms of computational costs, communication cost, and security features. We show that the proposed scheme has better security and has lower computational cost than other schemes.

Paper Organization

In Section 2, we introduce the previous research studies and describe their strengths and limitations. In Section 3, we explain the preliminaries of our scheme. In Section 4, we demonstrate the proposed mutual authentication protocols for various situations. In Section 5, we prove the security of our scheme using informal and formal methods. In Section 6, we provide the performance comparison result of the proposed scheme and related schemes. Finally, we provide the conclusions of this paper in Section 7.

2. Related Work

We introduce state-of-the-art authentication schemes proposed in IoV environments.

Wang et al. [11] proposed a V2I initial authentication and handover authentication schemes based on bilinear pairing. Their scheme succeeded in significantly lightening the computational load of handover authentication compared to the load of initial authentication. However, in both authentication situations, vehicles should perform bilinear pairing opearations, which require considerable computational cost.

Bojjagani et al. [12] proposed a secure authentication protocol for fog-based IoV networks. Their scheme considers various situations, including V2V, V2I, and V2R, and proposes an authentication protocol for each scenario. They also analyzed their scheme using the RoR model, Scyther, and Tamarin tools. However, their scheme utilized the elliptic curve cryptosystem (ECC), which requires high computational cost, and they did not consider repeated authentication situations.

Shen et al. [13] proposed a blockchain-assisted authentication scheme for edge computing-based IoV environments. In their scheme, the vehicle’s information is stored in the blockchain after a vehicle is authenticated to an edge node. Then, when the vehicle moves to the region of another edge node, the edge node can authenticate the vehicle quickly by querying the blockchain. However, blockchain can burden the edge server because it has to perform a high degree of computing in addition to vehicle authentication.

Wang et al. [14] proposed an authentication protocol using a chaotic map for electric vehicle charging systems. In their scheme, an electric vehicle authenticates to an aggregator to be provided charging services. They utilized chaotic map for fast authentication. However, there is a vulnerability in that the aggregator authenticates without knowing the pseudo identity of the vehicle; additionally, their scheme struggles to ensure mutual authentication.

Xi et al. [15] proposed a zero-knowledge proof (ZKP)-based anonymous authentication scheme for IoV environments considering fast reconnect situations. In their scheme, a vehicle can authenticate to an authentication server anonymously, and therefore, it can guarantee the privacy of the vehicle. Furthermore, they considered a fast reconnection phase, allowing for seamless communication in IoV environments. However, they used ECC encryption and decryption during the reconnection, and their scheme suffers from high computational cost.

Yang et al. [16] proposed a novel initial authentication and subsequent authentication schemes for IoV. They designed an initial authentication scheme using ECC and designed the subsequent authentication efficiently based on the initial authentication. However, they utilized ECC operations in a subsequent authentication phase, and it did not show a significant advantage in relation to computational costs compared to the initial authentication.

Dwivedi et al. [17] proposed a blockchain-assisted V2I handover scheme. They proposed a novel VANET system model using two blockchains. In their scheme, vehicle location information is stored in the auxiliary blockchain, and an RSU that keeps the auxiliary blockchain can authenticate the vehicle promptly. When a vehicle moves to the other region, the V2I authentication process requires more computational load. However, this approach is not suitable for the VANET environment because vehicles generally have high mobility.

Wang et al. [18] proposed physically unclonable function (PUF)-based authentication and a key agreement scheme for vehicular networks. They utilized various cryptosystems, including ECC, exclusive-OR, PUF, and hash operation, to guarantee privacy of vehicles. However, they did not consider handover and re-authentication situations, and their method could result in network inefficiency.

Rani and Tripathi [19] proposed a blockchain-based authentication scheme for VANET. They utilized consortium blockchain and ECC for secure V2I communication. They integrated a two-level blockchain storage method for reducing the computational cost. Therefore, their scheme prevents re-registration and re-authentication of vehicles in VANET. However, in their scheme, it is inevitable that additional costs arise due to the use of blockchain.

The contributions and limitations of cutting-edge schemes are summarized in Table 1. Overall, the existing schemes have limitations when applied to real IoV environments. In this paper, we propose a secure and seamless authentication protocol compared with existing schemes.

Table 1.

Strengths and limitations of the existing schemes.

3. Preliminary

We introduce the preliminaries of the proposed scheme.

3.1. Chaotic Map

We describe the basic definition of Chebyshev chaotic map and its hardness assumptions [10].

3.1.1. Definition

For a degree n and , Chebyshev polynomial can be defined as the following equation:

Then, Chebyshev polynomial defined in can satisfy the semigroup properties for , a large prime number p, and large numbers a and b as follows:

3.1.2. Hardness Assumptions

Based on Equation (2), the following three hardness assumptions hold for and a large prime p due to the Chebyshev polynomial: “Extended chaotic map-based discrete logarithm problem (CMDL)”, “extended chaotic map-based computational Diffie–Hellman problem (ECMCDH)”, and “extended chaotic map-based decisional Diffie–Hellman problem (ECMDDH)”. They are defined as follows:

- 1.

- ECMDL problem: When a big integer is given, there is no efficient algorithm to find s which satisfies ≡ y in polynomial time.

- 2.

- ECMCDH problem: When p and p for big integers y and z are given, there is no efficient algorithm to calculate p in polynomial time.

- 3.

- ECMDDH problem: When p, p, and for big integers y, z, and r are given, it is hard to determine whether .

3.2. Threat Model

We adopt both Dolev–Yao (DY) [20] and Canetti–Krawczyk (CK) [21] adversary models to analyze the proposed scheme. The adversary has the following capabilities [22,23]:

- The adversary has complete control over the wireless communication channels, and can eavesdrop, modify, and delete the messages transmitted in wireless channels.

- The adversary can act as a middleman between communication entities, performing replay attacks and man-in-the-middle attacks.

- The adversary can try to trace an identity or location of a vehicle using obtained messages from wireless channels.

- The adversary can obtain long-term or short-term keys of the network and try to reveal the session key.

In the informal analysis section, we demonstrate the security of the proposed scheme based on the adversary’s capabilities.

3.3. Design Goal

We designed the proposed scheme to meet the following security goals.

- 1.

- Mutual authentication: A vehicle and an edge server must verify each other’s legitimacy before agreeing to a session key. The communication should be rejected if the other party cannot be authenticated during the authentication phase.

- 2.

- Vehicle privacy: A vehicle’s identity, location, and transmitted data must be hidden in wireless channels. If traceable messages are continuously sent from a vehicle, an adversary may be able to guess the vehicle’s location or personal information.

- 3.

- Perfect forward secrecy: Even if the network is compromised and long-term keys are leaked, previously agreed-upon session keys must not be calculated. This includes session keys in all situations of initial authentication, handover authentication, and re-authentication.

- 4.

- Resistance to ephemeral secret leakage attack: Even if random numbers generated in a session are leaked to an adversary, the adversary cannot calculate the session key.

- 5.

- Seamless authentication: Considering the characteristics of IoV environments, it is necessary to lower the computational cost in repeated authentication situations. Furthermore, security must be guaranteed during the re-authentication and handover authentication processes.

3.4. System Model

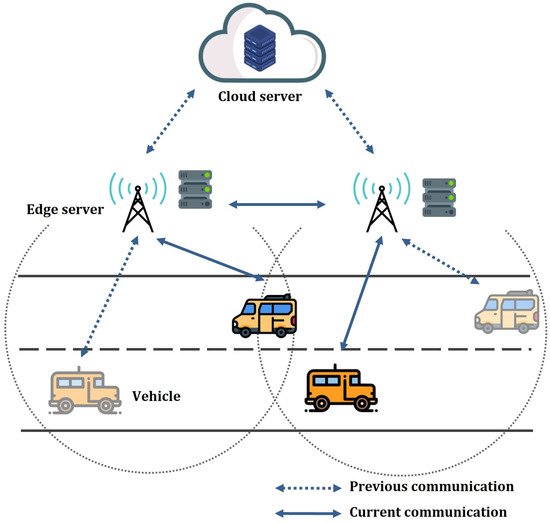

There are three entities in the proposed model: the cloud server (CS), edge server (ES), and vehicle. Figure 1 shows the system model.

Figure 1.

The edge-assisted IoV network model.

- CS: CS is a fully trusted entity that initializes the network, distributes secret keys for edge servers, and registers vehicles.

- ES: ESs communicate with vehicles in real-time and provide services. The transmitted data between an ES and a vehicle may contain sensitive and private data of the vehicle, and the transmission should be carried out after being mutually authenticated. In addition, when vehicles’ handover or re-authentication occurs, ESs should be able to verify vehicles quickly to ensure real-time communication.

- Vehicle: A vehicle with a user registers with CS and participates in the network. Vehicles initially authenticate with a nearby ES, and perform re-authentication and handover authentication with ESs frequently. An adversary may attempt to masquerade as a legitimate vehicle and steal private information.

4. Proposed Scheme

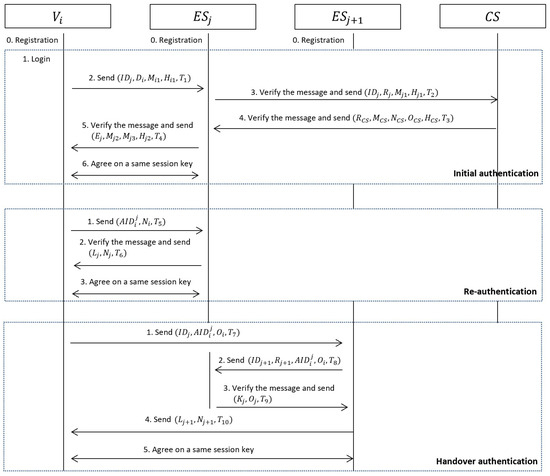

We demonstrate the proposed authentication schemes for IoV environments. The proposed scheme includes system initialization, registration, login and initial authentication, re-authentication, and handover authentication phase. Before providing detailed descriptions for each phase, notations and their meanings are summarized in Table 2, and the flowchart of the proposed scheme is presented in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Notations and meanings.

Figure 2.

The flowchart of the proposed scheme.

4.1. System Initialization

The system is initiated by . chooses a Chebyshev polynomial function with , a large prime number p, cryptographic one-way hash function , and a time threshold ΔT. Then, chooses a random number , computes p, publishes , and keeps s as a secret. Afterwards, chooses and , computes , and sends to . computes , publishes , and stores securely.

4.2. Vehicle Registration

A user chooses and and inputs them to . Then, computes , , and , and sends to . Then, computes and and checks whether is registered. chooses a random number and computes , , and . Then, sends to and transmits to , which is the closest edge server to . computes , chooses a random number , computes , , and , and stores in the memory.

4.3. Login and Initial Authentication

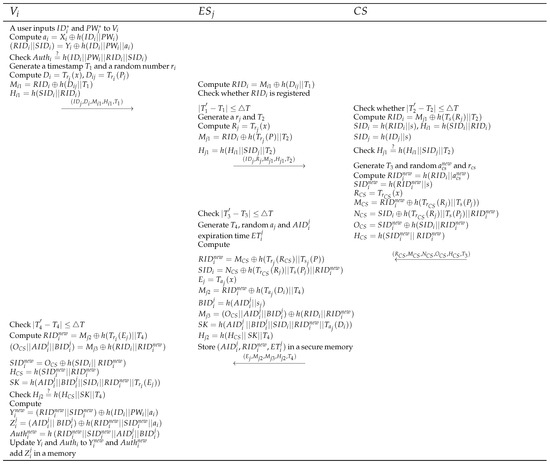

After registration, a user logs in to and authenticates with the nearest to be provided services. First, the user inputs and to , and computes and , and checks . If it is equal, generates a timestamp and a random number , computes , , , and , and sends to . After receives the message, computes , checks whether is registered and ΔT. If it satisfies, generates a random number and a timestamp , , , , and sends to . first checks whether ΔT, computes , , , and , and checks . Then, generates a timestamp and random numbers and , computes , , , , , , and , and sends to . After receives the message, the user checks whether ΔT, and generates a timestamp , random number and , and expiration time . Then, computes , , , , , , , and , sends to , and stores in a secure memory. receives the message, checks whether ΔT, computes , , , , and , and checks . If it is equal, computes , , and . Then, updates and to and and adds in a memory. Figure 3 presents the proposed initial authentication phase.

Figure 3.

Proposed login and initial authentication phase.

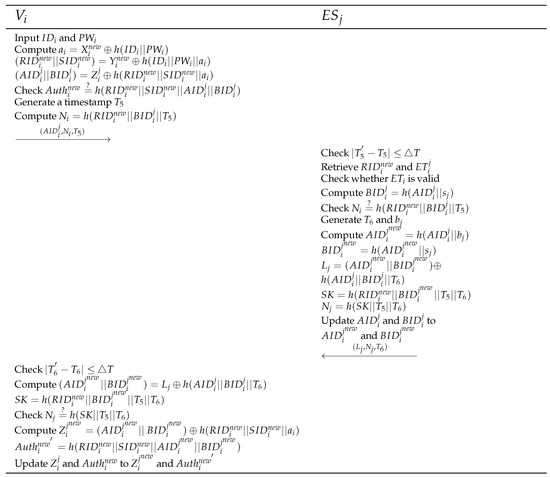

4.4. Re-Authentication

Within the expiration time determined in the initial authentication, can perform fast re-authentication with . When and are input to , computes , , and , and checks . If it is equal, generates a timestamp , computes , and sends to . checks whether ΔT, retrieves and using , and checks is valid. After that, computes and checks . If it is equal, generates a timestamp and a random number , computes , , , , and . sends to and updates and to and , respectively. checks whether ΔT, computes and , and checks . Then, computes and and updates and to and . Figure 4 presents the proposed re-authentication phase.

Figure 4.

Proposed re-authentication phase.

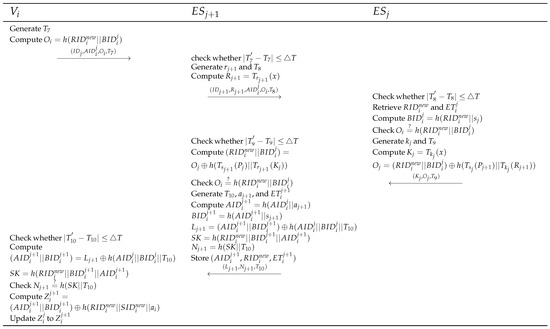

4.5. Handover Authentication

When moves to from , can quickly authenticate to through the proposed handover authentication. generates a timestamp , computes , and sends to . Then, checks whether ΔT, generates a random number and a timestamp , computes , and sends to . After checks whether ΔT and retrieves and using . Then, computes and checks . If it is equal, generates a random number and a timestamp , computes and , and sends to . After checks whether ΔT, computes and checks . If it is equal, generates a timestamp , a random number , and an expiration time , computes , , , , and , sends and stores in secure memory. checks whether ΔT, , and and checks . After that, computes and updates to . Figure 5 presents the propose handover authentication phase.

Figure 5.

Proposed handover authentication phase.

5. Security Analysis

We analyzed the the proposed scheme against different attacks using the informal security analysis and formal security analysis. We denote our proposed scheme as CM-SAS in the analysis sections.

5.1. Informal Analysis

In this section, we demonstrate that our scheme has resistance to various attack scenarios.

5.1.1. Resistance to Replay Attacks

A can intercept messages transmitted in public channels and reuse the message to cause delays or harm the network. In our scheme, every message includes a timestamp and a message hash value such as , , , and . If A transmits the message, the time threshold will be exceeded and the message will not be regarded as valid, and if A arbitrarily modifies the message, the hash value of the message is incorrect and it will be rejected by the other party. Therefore, the proposed protocol can defend against replay attacks.

5.1.2. Resistance to Privileged Insider Attacks

In this attack scenario, we assume that A is a privileged insider of , and A tries to log in to other networks using the information of . In our scheme, A can obtain in the registration phase. However, A cannot know any information about , which is required to log in to another server using . Therefore, A cannot access other networks by impersonating , and the proposed scheme is secure against the privileged insider attacks.

5.1.3. Resistance to Impersonation Attacks

A can impersonate or and try to generate a session key with the other entity. In case of masquerading as , A must be able to generate a legitimate message . is published and and can be generated by A. However, A cannot generate and without knowing and , which can be obtained with correct and . Therefore, A fails to send a message disguised as . On the other hand, A must be able to generate to disguise as . Similarly, A cannot make a legitimate , , and , and the message generated by A will be rejected by . Therefore, the proposed protocol is secure against impersonation attacks.

5.1.4. Support Perfect Forward Secrecy

In the proposed scheme, long-term keys are s, , and and the session key . Among these values, A can calculate = and can calculate . However, A can obtain no more values because cannot be calculated without knowing or or , which are random numbers generated in each session, and and are masked with . Therefore, A cannot know , , , and . It is also impossible to guess the above values simultaneously, and the proposed protocol can guarantee perfect forward secrecy.

5.1.5. Resistance to Ephemeral Session Random Number Leakage Attacks

The session random numbers include . To disclose , A can calculate , , and . Then, A can obtain and using and . However, A can still cannot obtain because it is masked with secret keys s and as well as the random numbers. Therefore, A fails to calculate the session key and the proposed scheme is resistant to ephemeral session random number leakage attacks.

5.1.6. Support Vehicle Anonymity and Untraceability

In the proposed protocol, transmits and receives from . The transmitted messages in a public channel do not include the identity of . Furthermore, when re-authentication or handover authentication occurs, sends , yet it is updated in each session. Therefore, vehicle anonymity is guaranteed in the proposed protocol. Instead, A can try to trace using the transmitted messages. Messages sent in public channels must contain repetitive values to succeed in this attack. In our scheme, the pseudo identity of is updated in every session and A cannot figure out the value to track , and therefore, a vehicle is untraceable in the proposed scheme.

5.2. Formal Security Under RoR Model

We formally analyzed the session key security of the proposed scheme using a Real-or-Random (RoR) model [24,25,26]. We conducted the RoR model-based security analysis of the initial authentication scheme because the re-authentication and handover authentication phases were performed based on the initial authentication. We denote and as network participants representing and , respectively. Under the RoR model, an adversary A executes queries (i.e., attacks) to obtain the agreed session key between network participants. The notations and their descriptions are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Queries and their descriptions.

What we can prove through ROR analysis is that the probability of A successfully distinguishing a session key and a random number when performing a query is not significantly different from 1/2.

Theorem 1.

Let be an advantage function of A to distinguish a random number and the session key after performing the above queries.

- : In , we assume that A has no information about the session key and performs no queries. When denotes the probability of A succeeding in guessing the correct bit c after ends, we can induce the following equation by the definition of the semantic security:

- : A performs and queries in the first game. In our scheme, A cannot obtain any values to calculate through a public channel. In the proposed scheme, the session key is calculated by . A cannot obtain any of the values to calculate through a public channel. Therefore, A has no advantage by executing query for guessing successfully, and we can induce the following equation at the end of :

- : A performs and queries to calculate in this game. Each message transmitted through a public channel includes a timestamp and message hash value, and A cannot arbitrarily modify the message. Therefore, A must find a hash collision to compromise of our scheme. Then, the advantage function of A after the end of can be induced as follows:

- : A can perform query and can obtain the stored values of such as , , and . If A succeeds to log in and sends an authentication request a message to , then A can agree on a session key with disguising as . However, for this attack to succeed, A must successfully guess the correct and , which is mathematically impossible. Assuming that A has and , the probability of successful guessing is

When all the games are over, A performs the query and should guess the correct bit c to win the game. A has no advantages through the above games, and we can obtain . Then, we can obtain the following equation using the triangle inequality:

Finally, the proof is completed.

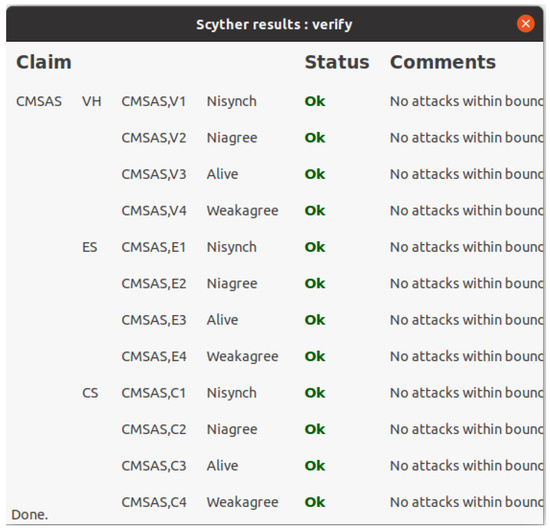

5.3. Scyther Tool

We simulated the CM-SAS using the Scyther tool [27], which is a developed for the automatic verification of security protocols. The Scyther tool verifies security for four statuses: Alive, Weakagree, Niagree, and Nisynch. The Alive status is the most basic level, which means that the communication partner is currently in a connectable state. Weakagree status is for checking whether the communication partner is legitimate. For example, the communication partner can decrypt or sign messages as well as being alive. Niagree is short for non-injective agreement. Niagree status means that the responder apparently previously ran the protocol with the sender, and both agreed on the values of the variables. Finally, Nisynch is short for non-injective synchronization, and it means that all the above conditions are satisfied and all messages are sent in the precise order described in the protocol. If a security protocol cannot satisfy the Nisynch status, it means that the protocol could be vulnerable to replay attacks. When a security protocol satisfies the four statuses, the protocol guarantees mutual authentication and resists replay attacks. The simulation result of the CM-SAS is shown in Figure 6. For all participating entities of the CM-SAS, the four statuses are satisfied, and we can say that the CM-SAS can guarantee mutual authentication and is resistant to replay attacks.

Figure 6.

Scyther simulation results.

6. Performance Analysis

We compare the proposed CM-SAS with the existing schemes [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19] in terms of computational cost, communication cost, and security features.

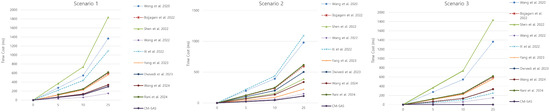

6.1. Computational Cost

Based on Kilinc and Yanik’s report [28], a notation and time cost of each operation is as shown in Table 4. The operations were executed with Ubuntu 12.04.1 LTS 32bit operating system, Intel Pentium Dual CPU E2200 2.20 GHz processor, 2048 MB of RAM. Furthermore, similar to [29], we estimated the time cost of the chaotic map to be one-third of ECC scalar multiplication. We compared the total computational cost in three scenarios: initial authentication, handover authentication, and re-authentication. Some schemes that do not handle handover and re-authentication are considered to repeat the initial authentication in those situations. The computational cost comparison results are summarized in Table 5.

Table 4.

Notation and time cost of each operation.

Table 5.

Computational cost comparison.

In the initial authentication, the CM-SAS has the lowest time cost on the vehicle side compared to the existing schemes, and has the second lowest time cost on the RSU/ES side. Compared to [11,12,14,15], TA/CS participates in the initial authentication and may have additional communication costs, yet it is much more efficient in terms of computational cost. In the handover authentication, the CM-SAS takes an overwhelmingly low computational cost on the vehicle, and on the RSU/ES side, it also takes significantly lower computational cost. Ref. [15] is the only scheme that considers re-authentication, and the CM-SAS is also much more efficient compared to the scheme of [15]. The computational cost of increasing the number of vehicles and RSU/ESs can be seen in Figure 7. In Figure 7, scenarios 1, 2, and 3 represent the initial, handover, and re-authentication situations, respectively. We assume that the existing schemes that do not design handover or re-authentication should repeat initial authentication in scenarios 2 and 3. Although the computational cost of the CM-SAS is similar to the scheme of [14] in the initial authentication, the CM-SAS is more efficient than other schemes. Furthermore, in the handover and re-authentication, the CM-SAS has a remarkably low computational load compared to any other schemes as the number of authentication increases. Overall, the proposed scheme is the most efficient compared to the existing schemes in terms of computational costs.

Figure 7.

Total computational cost as the number of authentication increases.

6.2. Communication Cost

For a communication cost comparison, we assume that a bit length of an identity, a hash output, a random number, an ECC point, a point of pairing-based group, a request, a timestamp, a token, and a chaotic map are, respectively, 160 bits, 256 bits, 256 bits, 320 bits, 1024 bits, 32 bits, 32 bits, 160 bits, and 256 bits. Furthermore, we assume that the AES-256 algorithm is used for symmetric en/decryption. The comparison results are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Communication cost comparison.

In the initial authentication phase, the proposed scheme generates a slightly higher communication cost than other schemes, except the scheme of [13,18]. However, in the handover authentication phase, the proposed scheme has similar communication costs with other schemes that consider handover situations. In the re-authentication phase, the proposed scheme generates much lower communication costs than other schemes, even compared to the scheme of [15], which is the only scheme that considers re-authentication situations. In real IoV environments, handover and re-authentication occur more frequently than the initial authentication, and the proposed scheme has competitive communication cost with existing schemes.

6.3. Security Features

We compare the provided security features of the CM-SAS and existing protocols [11,12,13,14,15]. We consider security and functional features, including A1, “resistance to replay attack”; A2, “resistance to privileged insider attack”; A3, “resistance to impersonation attack”; A4, “preservation of perfect forward secrecy”; A5, “resistance to ephemeral session random number leakage attack”; A6, “preservation of anonymity and untraceability”; A7, “preservation of mutual authentication”; and A8, “considering repeated authentications”. Table 7 shows that the CM-SAS can provide more security features than previous schemes.

Table 7.

Security feature comparison.

As shown in Table 7, the CM-SAS can provide more security features than the existing protocols. Furthermore, the proposed scheme has better performance than existing schemes. Therefore, the proposed protocol is more secure and efficient than other schemes.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, we proposed a chaotic map-based seamless authentication scheme (CM-SAS) for IoV environments. In the CM-SAS, an edge server stores a pseudo identity of a vehicle after initial authentication. Then, the edge server can use the stored information to authenticate the vehicle in re-authentication and handover situations. Therefore, the computational costs occurred in redundant authentication are significantly reduced. We have analyzed the CM-SAS using informal methods, the RoR model, and the Scyther tool to prove that the CM-SAS is resistant to various attacks, guarantees session key security, and provides mutual authentication. We also compared the CM-SAS with cutting-edge schemes, and showed that our scheme has better performance in terms of the computational and communication costs. In the future work, we plan to conduct simulations to apply our plans to a real environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.; methodology, S.S. and D.K.; software, S.S. and D.K.; validation, D.K. and Y.P.; formal analysis, S.S. and D.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.; writing—review and editing, D.K. and Y.P.; supervision, Y.P.; project administration, Y.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (Ministry of Science and ICT) (RS-2024-00450915).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ji, B.; Zhang, X.; Mumtaz, S.; Han, C.; Li, C.; Wen, H.; Wang, D. Survey on the internet of vehicles: Network architectures and applications. IEEE Commun. Stand. Mag. 2020, 4, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Castillo, J.; Zeadally, S.; Guerrero-Ibañez, J.A. Internet of vehicles: Architecture, protocols, and security. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 5, 3701–3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girdhar, M.; Hong, J.; Moore, J. Cybersecurity of autonomous vehicles: A systematic literature review of adversarial attacks and defense models. IEEE Open J. Veh. Technol. 2023, 4, 417–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Wang, C.; Shen, J.; Dev, K.; Guizani, M.; Wang, W. Edge-assisted hierarchical batch authentication scheme for VANETs. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 1253–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.F.; Ni, R. An identity authentication and key agreement protocol for the Internet of Vehicles based on trusted cloud-edge-terminal architecture. Veh. Commun. 2024, 49, 100825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazhar, S.; Rakib, A.; Pan, L.; Jiang, F.; Anwar, A.; Doss, R.; Bryans, J. State-of-the-art authentication and verification schemes in VANETs: A survey. Veh. Commun. 2024, 49, 100804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, P.; Singh, K.D.; Chaouchi, H.; Bonnin, J.M. Wireless sensor networks: A survey on recent developments and potential synergies. J. Supercomput. 2014, 68, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manivannan, D.; Moni, S.S.; Zeadally, S. Secure authentication and privacy-preserving techniques in Vehicular Ad-hoc NETworks (VANETs). Veh. Commun. 2020, 25, 100247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, S.; Lee, J.; Park, Y.; Park, Y.; Das, A.K. Design of blockchain-based lightweight V2I handover authentication protocol for VANET. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2022, 9, 1346–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. Cryptanalysis of the public key encryption based on multiple chaotic systems. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2008, 37, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Shen, J.; Lai, J.F.; Liu, J. B-TSCA: Blockchain assisted trustworthiness scalable computation for V2I authentication in VANETs. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. 2020, 9, 1386–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojjagani, S.; Reddy, Y.C.A.P.; Anuradha, T.; Rao, P.V.V.; Reddy, B.R.; Khan, M.K. Secure authentication and key management protocol for deployment of Internet of Vehicles (IoV) concerning intelligent transport systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 24698–24713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Lu, H.; Wang, F.; Liu, H.; Zhu, L. Secure and efficient blockchain-assisted authentication for edge-integrated internet-of-vehicles. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 71, 12250–12263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Han, Z.; Alazab, M.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Zhou, X.; Su, C. Ultra super fast authentication protocol for electric vehicle charging using extended chaotic maps. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2022, 58, 5616–5623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, N.; Li, W.; Jing, L.; Ma, J. ZAMA: A ZKP-based anonymous mutual authentication scheme for the IoV. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 22903–22913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhu, X.; Wang, X.; Fu, J.; Zheng, J.; Liu, Y. A novel authentication and key agreement scheme for Internet of Vehicles. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2023, 145, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, S.K.; Amin, R.; Vollala, S.; Khan, M.K. B-HAS: Blockchain-assisted efficient handover authentication and secure communication protocol in VANETs. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2023, 10, 3491–3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Fan, Z.; Su, Y.; Zheng, B.; Liu, Z.; Dai, Y. A Lightweight, Efficient, and Physically Secure Key Agreement Authentication Protocol for Vehicular Networks. Electronics 2024, 13, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, D.; Sachin, T. BTTAS: Blockchain-based Two-Level Transferable Authentication Scheme for V2I communication in VANET. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 120, 109767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolev, D.; Yao, A.C.-C. On the security of public key protocols. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1983, 29, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canetti, R.; Krawczyk, H. Analysis of key-exchange protocols and their use for building secure channels. In International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Proceedings of the EUROCRYPT 2001: Advances in Cryptology— EUROCRYPT 2001, Innsbruck, Austria, 6–10 May 2001; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; Volume 2045, pp. 453–474. [Google Scholar]

- Sutrala, A.K.; Obaidat, M.S.; Saha, S.; Das, A.K.; Alazab, M.; Park, Y. Authenticated key agreement scheme with user anonymity and untraceability for 5G-enabled softwarized industrial cyber-physical systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 23, 2316–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Park, Y. A robust authentication protocol for wireless medical sensor networks using blockchain and physically unclonable functions. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 20214–20228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, M.; Fouque, P.A.; Pointcheval, D. Password-based authenticated key exchange in the three-party setting. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Public Key Cryptography, Les Diablerets, Switzerland, 23–26 January 2005; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, J.; Son, S.; Lee, J.; Park, Y.; Park, Y. Design of secure mutual authentication scheme for metaverse environments using blockchain. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 98944–98958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapat, S.; Gautam, D.; Kumar, P.; Jangirala, S.; Das, A.K.; Park, Y.; Lorenz, P. Secure lattice-based aggregate signature scheme for vehicular Ad Hoc networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 12370–12384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scyther Tool. Available online: https://people.cispa.io/cas.cremers/scyther/ (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Kilinc, H.H.; Yanik, T. A survey of SIP authentication and key agreement schemes. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2013, 16, 1005–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasinezhad-Mood, D.; Ostad-Sharif, A.; Mazinani, S.M.; Nikooghadam, M. Provably secure escrow-less Chebyshev chaotic map-based key agreement protocol for vehicle to grid connections with privacy protection. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 16, 7287–7294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).