Abstract

The generation of synthetic cyber threat intelligence (CTI) has emerged as a significant area of research, particularly regarding the capacity of large language models (LLMs) to produce realistic yet deceptive security content. This study explores both the generative and evaluative aspects of CTI synthesis by employing a custom-developed detection system and publicly accessible LLMs. The evaluation combined automated analysis with a human study involving cybersecurity professionals. The results indicate that even a compact, resource-efficient fine-tuned model can generate highly convincing CTI misinformation capable of deceiving experts and AI-based classifiers. Human participants achieved an average accuracy around 50% in distinguishing between authentic and generated CTI reports. However, the proposed hybrid detection model achieved 98.5% accuracy on the test set and maintained strong generalization with 88.5% accuracy on unseen data. These findings demonstrate both the potential of lightweight models to generate credible CTI narratives and the effectiveness of specialized detection systems in mitigating such threats. The study underscores the growing risk of harmful misinformation in AI-driven CTI and highlights the importance of incorporating robust validation mechanisms within cybersecurity infrastructures to enhance defense resilience.

1. Introduction

Over the past few years, the development of artificial intelligence (AI) has progressed very rapidly. AI is omnipresent, performing a wide range of tasks, from the simplest to the most complex. Since its capabilities have expanded significantly, the potential risks they pose are not fully understood. Fabricated or manipulated information on various topics is widely spread on the Internet, especially on social networks. This applies to textual content as well as images, videos, and voice recordings. Text manipulation is one of the simplest forms of spreading misinformation, often leveraging large language models to automatically generate misleading content.

Spreading false information can be referred to as data poisoning, which is a form of cyberattack. A critical aspect of malicious data contamination is the use of artificial intelligence—not only to poison data, but also to weaken AI-based cyber defense systems [1]. Indeed, a single powerful language model, tailored for a specific domain for data poisoning purposes, can mislead numerous other machine learning models as well as cybersecurity experts. Particularly concerning is the fact that many cyber defense systems rely on publicly available data, thus increasing the risk of making incorrect cybersecurity decisions. Various methods can be employed to detect poisoned data, including calculating text similarity using different distance metrics and applying machine learning algorithms. However, no single universal tool exists to identify data poisoning due to the diverse ways in which it can be created and the varying subject matter of the information. Furthermore, verifying open-source data remains a challenge without a reliable reference point.

Large language models (LLMs) can be used to introduce misleading content into a specific type of data—cyber threat intelligence (CTI) data—in a fast and automated manner. For this reason, an investigation was undertaken to assess the ability to generate highly plausible CTI data that could be fed into platforms providing open source intelligence (OSINT), which serves as an essential source for analyzing, predicting, and countering threats. Given that even the unintentional introduction of misleading CTI poses an emerging risk, a study was conducted to develop a synthetic CTI detection model that could potentially be integrated into data acquisition systems. A comprehensive analysis of prior research on false CTI generation and AI-generated content detection was also performed. This is a relatively new and evolving topic that has shown promising results. Therefore, the decision was made to conduct a comparable study, demonstrate the effectiveness of other machine learning models, and expand the current state of knowledge.

This research aims to explore the feasibility of using a language model to generate cyber threat intelligence content and to conduct a thorough evaluation of the data produced. One of the main motivations for generating synthetic CTI was to obtain controlled data containing false or misleading information and to evaluate the ability to detect such content within CTI platforms or enterprise architectures. These platforms should have mechanisms to verify the accuracy of CTI data in order to build reliable content and safely share it with other trusted platforms. This work also attempts to address a methodological gap identified in related research. Previous studies on CTI generation have provided only partial evaluations, often limited to small case studies. In contrast, this study introduces a broader evaluation, which was multifaceted, involving an initial analysis, an evaluation using a different language model, and an examination by cybersecurity professionals, as well as popular large language models. Furthermore, both the generative and detection models were specifically tuned for the cybersecurity domain, requiring the development of a dedicated corpus and extensive hyperparameter optimization. This presents how resource-efficient models can be successfully adapted to the given domain. Finally, both developed models were evaluated, providing relevant conclusions regarding the generation and detection of synthetically created cybersecurity-related content and demonstrating how closely such content can approximate genuine CTI.

This paper provides a detailed description of the research environment and hardware specifications. The entire study was conducted on a personal computer equipped with a 64-bit Windows 11 operating system, powered by a 13th-generation Intel Core i7-13700F processor with 16 cores, 64 GB of RAM (DDR4 type), and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 5080 graphics card with 16 GB of VRAM. The study on the generation and evaluation of synthetic cyber threat intelligence was conducted using Python programming language, version 3.12, which is a common choice for machine learning purposes, including natural language processing. All programming scripts were executed in the form of multiple Jupyter notebooks, due to their flexibility and ease of use. To effectively utilize available resources and optimize resource-intensive operations, the PyTorch library, combined with Compute Unified Device Architecture (CUDA) technology, was employed to accelerate GPU computation [2]. The complete project is available on Github [3].

This paper is composed of seven sections. The following chapter outlines the state-of-the-art in cyber threat intelligence generation and AI-generated text detection. Section 3 introduces the basics of cyber threat intelligence, data poisoning attacks, false content detection, and natural language processing (NLP). Section 4 and Section 5 describe the development processes of the generative and detection models, respectively. The most extensive, Section 6, provides a detailed analysis of the obtained results along with an evaluation of both models, including automated analysis and human-based assessment. The final section concludes the paper.

2. Related Works

The topic of generating and detecting synthetic content is a relatively new and pressing issue, particularly with the increasing use of AI models. There has been extensive research done on the subject; however, the specific field of cybersecurity and generating cyber threat intelligence-related content is relatively niche.

The fundamental research Ranade et al. [4] introduced the use of a transformer-based architecture to create artificial cyber threat intelligence content. The authors note the potential for data poisoning in publicly available data, which can lead to incorrect attack analysis or enable adversary attacks on cyber defense systems. They demonstrated how to generate such descriptions using a fine-tuned GPT-2 model. Similar research was presented by Song et al. [5]. This time, the model used for generation was GPT-Neo. The cybersecurity corpus used in the investigation consisted of two primary sources: AlientVault OTX articles and the Advanced Persistent Threats (APT) attack reports library.

Qian et al. [6] introduced a complex approach to the data poisoning problem. They not only present the fake CTI generation process, but also its detection. For the generation part, the General Language Model was incorporated, which was first pre-trained on a broad range of non-domain-specific texts and then fine-tuned on 5381 cybersecurity blogs and APT reports. The research conducted by Li et al. [7] touches on similar topics. The generation and detection models were developed using a custom STIX-CTIs dataset, which included APT reports, Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVEs), and selected companies’ blogs. Han et al. [8] presented a new architecture for extracting cyber threat intelligence relations and detecting false content. As part of the framework, adversarial training is performed, integrating the generator and discriminator within the Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) architecture, to create a reliable model for assessing the veracity of threat data. An interesting issue regarding the lack of sufficient cyber threat intelligence data was raised Chen et al. [9]. The authors proposed a method for well-formed synthetic data augmentation. It was driven by the desire to enhance the effectiveness of machine learning in the Named Entity Recognition and Relation Extraction tasks in the cybersecurity domain.

The study by Gakpetor et al. [10] focused on AI-generated text detection. The authors developed a system capable of distinguishing between the text generated by AI and written by humans. The dataset comprised diverse essays, both human-written and AI-generated, from the Kaggle platform. An important comparative study on AI-written text detection was conducted by Chandana et al. [11]. The research includes training and evaluation of such models as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), Gated Recurrent Units (GRU), eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), Long Short-Term Memory networks (LSTM) and Random Forest. The authors noted CNN’s superior performance and intend to expand its use in future research on AI-generated text detection, with a focus on countering adversarial attacks. Another comparative study was conducted Nguyen [12]. The research incorporated three machine learning models that aimed to detect AI-generated texts: Random Forest, Support Vector Machines (SVM) and XGBoost. The authors proposed two distinct detection methods: machine learning classification and cosine similarity analysis. The research by Alamleh et al. [13] employed a wide range of models to detect texts generated by ChatGPT 3.0. The dataset created for the study consisted of student and ChatGPT-generated responses, covering both essays and programming tasks. The responses were truncated to equal lengths to prevent models from using the text length feature. The authors explained that deep learning models performed worse than classic machine learning algorithms due to the small dataset size.

Most existing works provide only partial evaluations of generated CTI samples and overlook the generalization of detection systems. They also seldom explore efficient model development under hardware limitations. This paper fills these gaps by presenting a comprehensive evaluation framework, validating model generalization, and showing that resource-efficient generative models can still deliver high performance.

3. Cyber Threats and Natural Language Processing

A predictive approach to cybersecurity focuses on anticipating and mitigating potential threats before they materialize, enabling proactive defense rather than reactive response [14,15,16]. Cyber threat intelligence refers to the process of acquiring, analyzing, and sharing information to recognize, monitor, and predict cyber threats or risks. Data acquisition may be performed as an automated process, collecting the information from various sources, including both internal (within the organization) and external (from open sources) ones. Determining the vulnerabilities prior to their exploitation by attackers introduces proactiveness into cybersecurity strategies. For instance, CTI may be useful in early detection of attack patterns by leveraging knowledge of specific threat actors’ attack techniques or used malware. This intelligence may also be utilized in intrusion detection systems as a particular threat indicator or tactic, technique, and procedure (TTP). In addition, CTI can offer some security strategies adapted to counteract the behaviors used by cybercriminals. Consequently, it serves as a critical component for organizations that want to avoid, identify, and react appropriately to potential cyber threats [17,18].

3.1. Data Poisoning and False Content Detection

Referring to OWASP Foundation [1], data poisoning is an attack that entails data manipulation. While machine learning is used in many systems, this may involve manipulating the model’s training data in order to cause it to make inappropriate decisions. The reason for data poisoning is an insufficient or lack of data validation, which can result in malicious data being injected and learned by the susceptible model. The consequences can be particularly critical for AI-based security systems, causing them to ignore or misclassify attackers’ harmful activities as benign, unpredictably change the security policy directives, or make other erroneous decisions, exposing the organization to attacks. Data manipulation can involve incorrect data labeling or the inclusion of false information. The latter can also be achieved by poisoning open source intelligence, which comprises blogs, social media websites, technical reports, and other sources that are often used in the training process. Many automated tools gather OSINT data for threat intelligence purposes, entailing a risk of injecting poisoned threat-related information into AI-based cyber defense systems. Additionally, in many organizations, security analysts use AI-based security systems to detect new vulnerabilities or attack vectors based on mined data [19]. To prevent data poisoning, particularly when conducted on AI-based systems, several steps must be taken, including rigorous training data validation and auditing, model validation with a distinct validation set, or training various independent models on separate fragments of the training set and employing all of them as an ensemble predictive model.

Misinformation is false or inaccurate information without the intention of causing significant harm [20]. Its detection techniques are continuously developing, but are still inadequate, due to the increasing complexity of misinformation in digital content. To take countermeasures or reduce its impact, defense mechanisms can be employed, including false content detection. This can involve manual data validation, which is a slow process when dealing with large amounts of data, or an automated approach using machine learning in the form of a binary classification task. In practice, the process is more complex and involves the integration of various methods. When examining textual content, natural language processing can be used for semantic analysis and extraction of both text features and relevant information. This is an essential step before feeding the data into the classification model, often based on Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) family models. Then, algorithms are trained to detect misinformation, anomalous content on social networks, or unauthentic accounts [21,22].

3.2. Natural Language Processing

The process of analyzing and interacting with text is referred to as natural language processing. It typically denotes the use of advanced machine learning models that, after processing text and creating its representation, learn to understand and utilize it. These models are often available in base versions that can be customized to meet specific needs.

Before the model processes textual data, text preprocessing is required. This typically includes sentence segmentation, word format normalization, and tokenization. Sentence segmentation is simply the process of splitting a long paragraph into individual sentences. While tokenization refers to dividing text into smaller parts, such as words, sub-words, or even letters [23].

The transformer architecture is applied in various language models, including causal and bidirectional language models. In causal modeling, the following word (token) is predicted based only on the previous words, while bidirectional modeling predicts on all the tokens in the sentence. The transformer is a neural network architecture central to large language models, distinguished by its core component: the self-attention mechanism (or multi-head attention). It helps to create the contextual depiction of each token by paying attention to neighboring tokens and building relations between them. During text processing input and output tokens are transformed into a semantically meaningful vector representation, known as a word embedding. Furthermore, the transformer architecture uses positional encoding to indicate the position of each token along the sequence [23,24].

Large language models are trained with a massive text corpus using a self-supervision algorithm (pre-training). They can be further adapted to a specific domain by a fine-tuning process, which is training with domain-related data. Due to the high cost and time-consuming process, parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) can be employed, where only selected parameters are updated in the process, and the remaining ones are left unchanged. An example of such a method is low-rank adaptation (LoRA), which freezes the model’s layers and approximates the parameter changes using significantly smaller trainable adapters [23]. Moreover, small language models can be trained using large datasets while remaining effective across a broad spectrum of tasks, by reducing costs and memory. Such a model is TinyLlama, which has 1.1 billion parameters and was trained within three epochs cumulatively on almost 3 trillion tokens coming from two principal sources: the SlimPajama corpus and the StarCoder training dataset. It follows the Llama 2 architecture, being a decoder-only transformer, and consists of rotary positional embedding, pre-norm and RMSNorm normalization layers, SwiGLU activation function, and grouped-query attention to decrease memory consumption [25].

4. Generative Model

To generate high-quality cyber threat intelligence samples, a generative model was developed. As the primary purpose was to create realistic text with numerous technical details in the cybersecurity domain, a small open-source language model was utilized. The selected model, called unsloth/tinyllama-bnb-4bit, is a 4-bit quantized TinyLlama model, developed by the Unsloth team, with 631 million parameters [26]. The decision was made to use a pre-trained model, which was subsequently fine-tuned for the cybersecurity domain. This approach was driven by the fact that developing a high-performing language model from scratch is a resource-intensive and expensive process, particularly on a computer with a single GPU. This specific model was selected for several key reasons. Firstly, it was employed in the study to assess the small model’s generation capabilities and ease of adjusting to a new domain. Secondly, this choice enables a comparison of its performance with models used in other research, especially those utilizing GPT models [4,5]. Finally, by implementing the model’s quantization and utilizing the Unsloth framework for fine-tuning large language models [27], a significant reduction in memory usage and acceleration of calculations can be achieved.

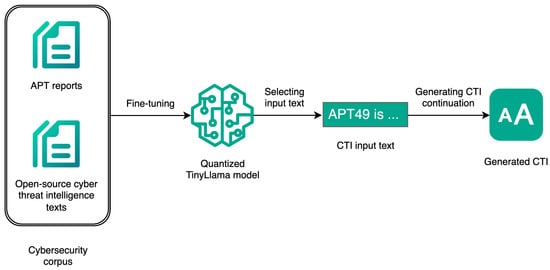

The generation process consisted of two main steps: model fine-tuning with cybersecurity texts and generating new CTI samples. The simple workflow is presented in Figure 1. To develop a high-functioning CTI generative model, the entire process was repeated multiple times. With each subsequent iteration, the cybersecurity corpus, focusing mainly on cyber threat intelligence and attacks, has been expanded. Additionally, the training hyperparameters, such as the number of training steps, batch size, and learning rate, were adjusted empirically each time to achieve the lowest training and validation losses and, consequently, the minimal model’s perplexity. After each refinement phase, the generated samples were evaluated with another fine-tuned language model, which led to the development of the final generative model.

Figure 1.

Workflow for Cyber Threat Intelligence Generation Process.

4.1. Fine-Tuning

Beginning with the first fine-tuning stage, external datasets containing samples in multiple languages were used. The primary focus was on English texts to be able to verify the accuracy of the generated samples. Consequently, text pre-processing was necessary to remove non-Latin characters and other elements that could be misleading. To avoid overfitting and monitor the learning process, the data was divided into training and validation sets in a 70:30 ratio in each iteration, and for the final corpus in an 80:20 ratio. The model was loaded into memory using the Unsloth framework [27], which serves as a wrapper for the HuggingFace transformers [28]. The FastLanguageModel module enables accelerated fine-tuning and outperforms the base Transformers library in efficiency. To facilitate the training process and enable the model to expand its knowledge in cybersecurity, a Continued Pretraining approach was employed with the transformers library [28]. This was achieved by tokenizing raw text inputs without additional instructions, labels, or special prompts. Truncation and padding were also applied to enable effective batch processing.

The first fine-tuning stage was conducted using mainly a corpus of cyberattack reports associated with APT groups. The documents are available in the GitHub repository [29] and were downloaded with dedicated tools [30]. The next step was to perform text preprocessing for use in the fine-tuning process. PDF files were read using the PyPDF2 Python library [31], then, among others, unwanted characters were removed, unicode characters normalized, and footers, headers and captions were eliminated. Each of the 660 documents used was then divided into smaller chunks, with a maximum length of 4096 tokens. The process resulted in a dataset comprising 1256 rows. To include additional text structures, it was combined with the mrminhaz/CTI-Reports dataset, which includes 592 rows [32], and the skrishna/cti-rcm-2021 dataset, which contains 1000 rows [33]. The final dataset consisted of 1993 rows for training and 855 rows for evaluation. As the dataset was not too large, the model was fine-tuned during a single training epoch. The learning rate was set to 2 × 10−5, and the batch size was set to 8. Training was completed after 180 out of 250 steps, with early stopping, resulting in a training loss of 3.44 and an evaluation loss of 3.18. The perplexity was 24.05, which is a satisfactory result for the initial model fine-tuning.

In the second fine-tuning iteration, the dataset was expanded with approximately 10,000 additional rows from the ctitools/orkl_cleaned_10k dataset [34], which also included cyberattack reports and various cybersecurity blogs. Data were again divided into a 70:30 ratio, resulting in 8971 training samples and 3846 evaluation samples. The fine-tuning process began with the previously prepared model. The learning rates tested included 5 × 10−5, 2 × 10−5, and 2 × 10−4, while the batch sizes used were 16, 32, and 64. The model was fine-tuned multiple times, starting from the last model checkpoint each time. The final training process was conducted with a learning rate of 2 × 10−4 and a batch size of 64, and terminated after 140 training steps, resulting in training and evaluation losses of 2.16. Further training would not improve the model’s performance, as the loss began to increase slightly, and some fluctuations occurred. A score of 8.64 was obtained for perplexity, representing a significant improvement over the first iteration of fine-tuning and suggesting a better familiarity of the model with the cybersecurity domain.

The final extension of the dataset was completed for the third fine-tuning stage. Several new publicly available datasets were incorporated, focusing on warranting a diverse range of cybersecurity information. The additional datasets were filtered to include records that are at least 15 words long and contain a notable number of technical details. After the filtering process, approximately 8500 new rows were added, originating from the following collections:

- mrmoor/cyber-threat-intelligence [35],

- mrmoor/cyber-threat-intelligence-splited [36],

- mrmoor/cyber-threat-intelligence-relations-only [37],

- aayushpuri01/threat-intel-dataset [38],

- sarahwei/cyber_MITRE_tactic_CTI_dataset_v16 [39].

The end-stage dataset comprised 16,790 training rows and 4198 evaluation rows. The fine-tuning process began, as in previous iterations, with the last trained model. The batch size was raised to 128, the learning rate was reduced back to 2 × 10−5, and the number of training epochs was increased to 2. The training ended after 260 steps without triggering an early stopping mechanism, resulting in a training loss of 2.50 and an evaluation loss of 2.63, which corresponds to a perplexity of 13.86. This value indicates a decrease in the model’s confidence in predicting next tokens compared to the previous fine-tuning iteration; however, the model has now been provided with significantly more data.

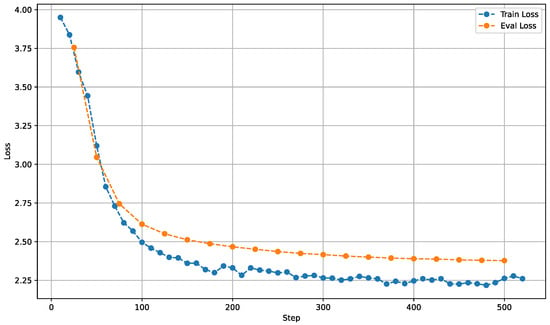

The final fine-tuning stage was conducted to enhance the model’s performance by adjusting the hyperparameters. To prevent the repetition of potentially erroneously learned patterns, it was decided to start the training process from a base model that had not been fine-tuned, using the same final training corpus. The number of epochs was left at the value of 2, as further training did not improve the results, and the loss began to oscillate once the third epoch started. The batch size was reduced to 64, and the learning rate was lowered to 2 × 10−4, utilizing the last set of hyperparameters from the second stage. The training was completed after 526 steps, with a training loss of 2.26 and a validation loss of 2.38. The corresponding loss curves are presented in Figure 2. As can be observed, the model demonstrates consistent learning dynamics, with no indication of overfitting. The adopted approach of fine-tuning the base model yielded improved performance, as the perplexity decreased to 10.78, which is a satisfactory outcome.

Figure 2.

Training and Evaluation Loss Curves of the Final Model.

4.2. Synthetic Cyber Threat Intelligence Generation

After each stage of the fine-tuning process, the new model was tasked with generating synthetic cyber threat intelligence descriptions. To facilitate this process, the evaluation data rows have been specially prepared. First, a several-sentence fragment was drawn from each of the rows with a maximum length of around 100 tokens. The first 15 tokens, which comprise approximately 11 to 13 English words, were then used as input. Finally, each of the inputs was provided to the model along with a custom prompt instructing it to extend the given text by adding 2 to 3 sentences. These sentences were designed to be highly realistic and include technical details while still being manipulated for internal adversarial testing.

The prompt engineering process was crucial, as the model did not always continue the text but sometimes completely altered it. To guide the model successfully, several key instructions were given: assigning the role of a cybersecurity analyst to the model, ensuring that the sentences follow the formal style typical for CTI reports and include some MITRE ATT&CK techniques, names of APT groups, or specific file paths. Most importantly, an example of the input text and expected continuation generated by Chat GPT was provided to the model as a reference. In addition, experiments with generation parameters were crucial for achieving high-quality text generation. The balance between randomness and determinism in the next token generation must have been ensured. However, the parameter values were ultimately left at default, allowing the model to select tokens according to their probabilities. The repetition penalty had to be set to 1.2 to prevent the model from repeating the same tokens or identical fragments.

The final step was to filter the generated CTI samples and create a dataset for detection. The outputs were normalized unicoding when they contained some special characters. Then some unwanted fragments, such as Continuing, were removed from the response. If the processed generated description did not contain any fragments like fake CTI or this is an example of how to generate fake CTI report, etc., it was added to the dataset and labeled as 1. The corresponding real fragment from which the input came, but in length before truncation of 15 tokens, was added with label 0. In this way, four datasets coming from each iteration were obtained to develop a generated CTI samples detector. Additionally, the base model was asked to generate some samples, given the same prompt and inputs as the final model.

5. Detection Model

To build a well-performing detection model capable of accurately distinguishing between CTI descriptions written by humans and those generated by a fine-tuned TinyLlama model, it was essential to select an appropriate model for this task. In this case, the crucial part is understanding the content, as the generated samples may contain misinformation that can mislead not only AI-based analysis and detection systems, but also experienced cybersecurity analysts. For this purpose, an encoder-only transformer model was chosen, which is designed, among others, for text classification. The decision to utilize the transformer-based model, rather than word embeddings, in conjunction with a traditional machine learning classifier, was driven by the need for text understanding. Although techniques such as word embeddings convey the general meaning of texts well, transformers also capture context by analyzing the order of tokens and relations between them. The selected distilbert/distilbert-base-uncased model is a smaller and faster version of the BERT model with 67 million parameters [26]. It has approximately 40% fewer parameters than the full BERT-base model, resulting in faster training and inference while maintaining high performance. Thanks to its smaller size, this model retains approximately 97% language understanding capabilities while operating around 60% faster [40]. The model was fine-tuned utilizing the HuggingFace transformers framework [28] on the previously collected data, as the cybersecurity domain is not a common subject for training such models. This framework provides a unified high-level API, native support for multiple deep-learning backends, and broad availability of pre-trained language models. It also enables efficient experimentation and reproducible training pipelines.

The detection model was developed iteratively, like the generative model, to create efficient models for both generation and detection. After each generation process, the labeled data were provided to the detection model for fine-tuning, followed by testing, and finally adjusting both models. To evaluate the performance of the detection model and monitor it throughout the learning process, several metrics, including precision, recall, and the F1-score, were calculated using the scikit-learn library [41]. The generated data was labeled as 1, and real (human-written) as 0. In each subsequent iteration, a new dataset was added to the previous one, extending the number of samples. Training, validation, and test sets were divided in a ratio of 72:8:20 to ensure sufficient training and testing samples (in a dataset of limited quantity for effective generalization), while also providing data to validate the training process. The base model was fine-tuned every iteration, as no significant improvement was noticed when training from the checkpoint. In Table 1, there are the training, validation and test set sizes for each iteration of the model development process. The training was run for a maximum of three epochs, with an early stopping mechanism enabled and metrics monitored simultaneously. The batch size was set to 16, and the learning rate was set to 2 × 10−5 in the first three stages, then lowered to 1 × 10−5. The weight decay parameter was set to 0.01. The detector performed exceptionally well on the test data each time; therefore, the generator continued to be improved.

Table 1.

Dataset Sizes for Each Generation Iteration.

After the last generation stage, 100 data rows with were selected for further evaluation by cybersecurity specialists. The rows were formatted and truncated to a shorter length, subsequently filtered out from the training and evaluation sets before the last detection model fine-tuning, and finally given for evaluation as test data. Unfortunately, the model incorrectly identified all this data as generated, leading to the decision to rebuild the detection model. As the inputs were shorter, the problem was recognized as incorrect decision-making due to the input length. It was decided to use prajjwal1/bert-tiny, a significantly smaller version of the BERT model with approximately 4 million parameters, which was trained with shorter context texts [26]. Its final training hyperparameters were: a learning rate of 2 × 10−5, a batch size of 32, a weight decay regularization of 0.01, and a cosine learning rate scheduler. The number of training epochs was set at 15, as a smaller model needed more time to achieve satisfactory results. The model obtained slightly worse results for the general test set and significantly better results for the rows designed to be evaluated by humans.

The final step was a generalization check using data with a completely different structure and not previously seen. For this purpose, the generated outputs of the base model were provided to both models for comparison. The first model remarkably outperformed the second. Thereby, it was decided to build the detection system using both BERT models, where the decision on model selection will be made based on the length of the tokenized input. Various token thresholds were tested to achieve the best results for the test data, data prepared for human evaluation, and pre-trained model-generated data. Finally, a value of 100 was empirically determined, which, if exceeded, would result in DistilBERT model decisions. Otherwise, the BERT-Tiny one would be used.

6. Results Analysis and Evaluation

The fine-tuned generative model produced a wide range of cyber threat intelligence descriptions. Because a pre-trained model was used and further fine-tuned, the synthetically generated texts were linguistically coherent. The model was capable of generating a broad spectrum of syntactically correct sentences, which could introduce misinformation solely in terms of their content. However, it remains crucial to test the developed models and evaluate them objectively.

6.1. Detection Model Results

A key part of the research involved evaluating the generated samples using another language model. This enabled an automated approach and the potential to identify patterns invisible to humans. The finally created detection system consisted of two distinct models that distinguished the samples. The results obtained by its detections are outlined in Table 2. The table consists of three distinct types of detection. The first relates to classifying the samples in the test dataset, which were similar to those utilized in the training phase. The second correlates with distinguishing the items in the dataset that contain the generations of the base model. The last one applies to differentiating the carefully selected set of 100 real and generated sentences. The macro-average metrics were utilized, which compute the values for each class separately and then average the values. Taking into account the predictions on the test dataset, all metrics achieved a value of 0.985, indicating a very high performance of the detection model. Evaluating the classifier’s generalization, it predicted on the pre-trained model’s outputs, which it had never seen. The results are slightly worse, falling within the range of 0.884 to 0.885; however, the detection system still demonstrates overall good performance. The most difficult to evaluate was the last dataset, for which the metric values were the most diverse. The model achieved an accuracy of 0.84, a precision of 0.879, and a recall of 0.84, yielding an F1-score of 0.836 and an F2-score of 0.833. The results were worse than those for the previous dataset; nonetheless, in most cases, the model can detect the generated texts, which is already a test of real-world situations.

Table 2.

Final Detection System Results.

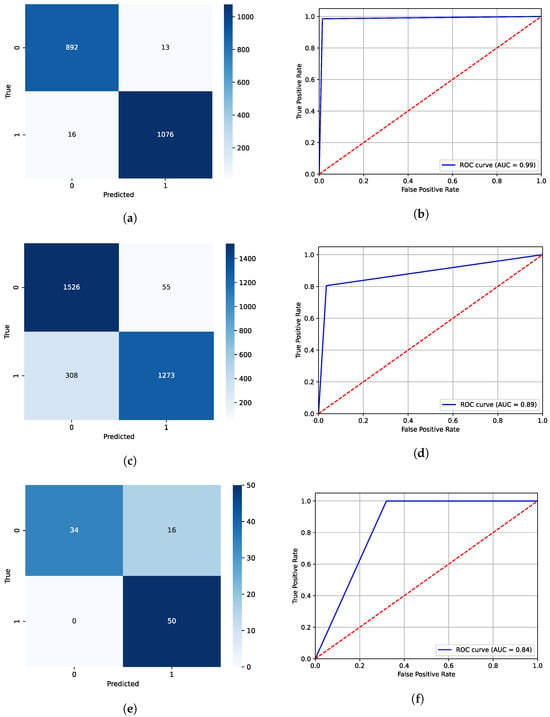

Further analysis can be driven by examining the confusion matrices (where zero denotes Real and one represents Generated CTIs), and the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC AUC) curves for each dataset. Figure 3a,b present the classification results for the test dataset. Then, Figure 3c,d show the confusion matrix and the ROC AUC curve, respectively, based on the detection model predictions for the dataset including the CTIs generated by the base model. Finally, Figure 3e,f depict the corresponding plots for the 100-sample survey dataset. Considering the test dataset, the confusion matrix indicates that the model performs exceptionally well in sample classification, with only 13 false positives and 16 false negatives out of nearly 2000 test samples. The AUC value of 0.99 shows an almost perfect ability to distinguish between the two classes, regardless of the decision threshold set. The low values of both false alarms and oversights prove the model’s operational reliability.

Figure 3.

Comparison of Classification Results for Fine-Tuned Model, Base Model, and Survey Data. (a) Confusion Matrix for Classifier Distinguishing Human and Fine-Tuned Model Texts. (b) ROC AUC Curve for Classifier Distinguishing Human and Fine-Tuned Model Texts. (c) Confusion Matrix for Classifier Distinguishing Human and Base Model Texts. (d) ROC AUC Curve for Classifier Distinguishing Human and Base Model Texts. (e) Confusion Matrix for Classifier Distinguishing Data Selected for Survey. (f) ROC AUC Curve for Classifier Distinguishing Data Selected for Survey.

Regarding the dataset with samples generated by the base model, which the detection model had never seen, it correctly classified 1526 human-written sentences and 1273 Llama-generated ones. The number of false positives reached 55, and the number of false negatives reached 308, which means that 19% of the generated data was overlooked, and 3% of the real data would cause a false alarm. The classification results are worse than those for the test data. However, this dataset tests the real generalization of the detection system, demonstrating that the model, in general, can detect the generated CTI texts with some room for improvement in terms of false negatives. The ROC curve, with a true positive rate of approximately 80%, further suggests that the detection model is more cautious in labeling samples as generated. The AUC, which reached 0.89, confirms that the model can still effectively distinguish between classes.

On the subject of the last dataset, this data was also never seen by the model, as it was filtered out of the entire dataset and excluded from training. This evaluation was conducted to assess the performance of the detection system in real-world scenarios and compare its results with those of large language models and human decisions. In this case, sentences were, on average, shorter, and thus a smaller BERT model was primarily used to make decisions. This time, the model correctly classified all the generated samples, resulting in a recall of 1.0 for the generated class. However, it produced a relatively high number of false positives, meaning that 32% of the real samples would trigger false alarms—a better case than overlooking generated CTI texts. The AUC value of 0.84 indicates a moderate ability to distinguish between the classes, which is lower than in the previous cases, but still satisfactory. The ROC curve shows a perfect true positive rate, but unfortunately a high false positive rate, suggesting that the decision threshold should be increased. For precision improvement, the model should be further optimized.

Taking into account all the results achieved, an analysis can be performed of both the quality of the generated CTI descriptions and the effectiveness of the detection system under various constraints. The developed detection system constructively differentiates between real and synthetically generated cybersecurity content, particularly in cases where the test data have the same distribution as the training data. In most cases, the model correctly detects generated sentences with a moderate degree of generalization. The data generated by the pre-trained model, which lacks cybersecurity domain knowledge, can be less predictable and more chaotic, resulting in decreased classification accuracy. However, the set with the best generations of the fine-tuned model constitutes the biggest challenge for the detection system. The decrease in classification results from almost 99% to nearly 84% suggests that while among the mass-generated texts, many may be of average quality and easy to detect, their appropriate selection makes it difficult to distinguish the real text from the generated one. This indicates that the created generative model can produce high-quality and realistic-looking adversarial CTI descriptions that are deeply misleading. As many as 32% of the real data were incorrectly classified as generated. Although the detector correctly identified all the artificial samples, it exhibited uncertainty and misclassified the authentic texts that were very similar to the synthetic ones. This suggests that, given the most realistic generated data, the model makes decisions based on probably erroneous conclusions. Considering all datasets, the detection system is reasonably effective but would require further refinement, especially with larger amounts of high-quality generated data. If only the DistilBERT model had been utilized for detection, better results would have been achieved for the first two datasets. However, for the key real-world case, its results were useless, further underscoring the quality of the generated data. It was decided to retain the hybrid approach, opting for a compromise between results and the model’s generalization to new data.

6.2. Human-Based Assessment

The final human-based assessment of the generated CTIs was conducted using an expert survey approach. The evaluation involved 21 experts selected based on their competencies in the field of cybersecurity. Among them, 11 were cybersecurity students, and 10 were professionals with extensive experience in CTI content analysis. The sample size was intentionally limited due to the auxiliary nature of this assessment and the specific expertise required from the participants. The survey was carried out using the 100 real and generated sentences mentioned in Section 6.1. These instances were carefully chosen to include the most realistic outputs produced by the final fine-tuned TinyLlama model, as well as representative human-written samples from the latest dataset prepared for the detection model. An equal number of generated and authentic descriptions was used to enable a balanced and meaningful analysis.

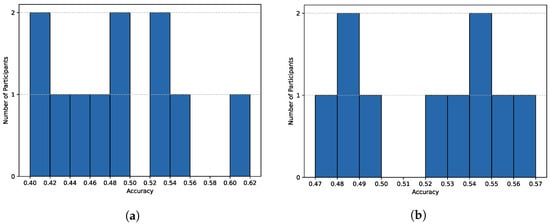

The results of human-based assessment will begin with the distributions of achieved accuracies, followed by the respective counts of true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives. The results were astonishing, showing that even experienced analysts struggled to identify artificially generated CTIs. Figure 4a,b present the accuracy distributions (i.e., all correctly identified samples) among students and analysts. Among all participants, most of the scores are centered around 50%, indicating random choices. Eight scores fall in the range from 45% to 50%, and nine fall in the range from 52% to 57%. Three scores were below 45%, and only one participant achieved a score above 60%. Most results range between 47% and 55%, which constitutes 66.67% of all responses. None of the respondents exceeded 65%, which highlights the difficulties in identifying the generated texts. Particularly interesting are the scores below 45%, which are even worse than random guessing. The average score is 49.95%, with a standard deviation of 5.08 and a median of 49%. When analyzing student responses, the results vary, with a lack of clear patterns, ranging from 40% to 56%, with one score of 61% being the highest. Regarding analysts, their scores are divided into two groups: one ranging from 47% to 50%, and the second from 52% to 57%. Although their responses are generally better, with most scores above 50%, it still shows that even experienced cybersecurity analysts and threat hunters cannot distinguish between human-written and AI-generated CTI descriptions. The higher diversity among cybersecurity students may be due to limited experience.

Figure 4.

Accuracy Distributions Across Different Groups of Respondents. (a) Cybersecurity Students. (b) Cybersecurity Analysts.

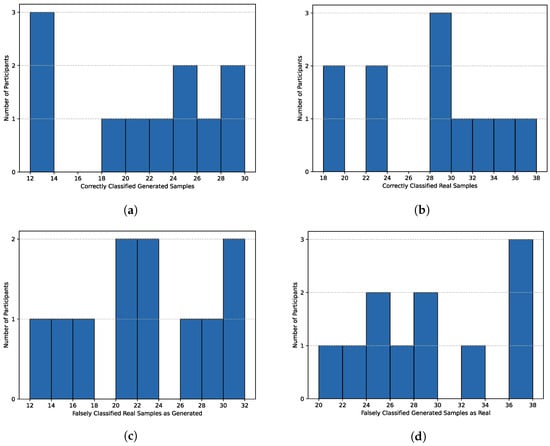

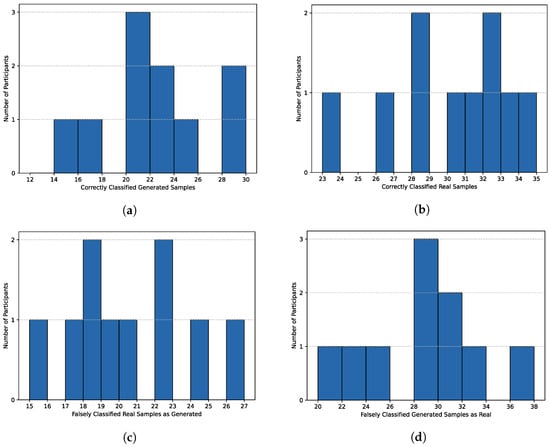

Figure 5a and Figure 6a present the distributions of true positives, representing correctly identified TinyLlama-generated samples, for students’ and analysts’ responses. The results range from 12 to 30 out of 50 for all participants, with 33.33% of the scores falling within the range of 20–23. The average number of correctly classified generated samples is 21.33 with a standard deviation of 5.47. Remarkably, only seven respondents, constituting 33.33% of all participants, correctly identified at least 50% of synthetically created CTIs. This indicates that 66.67% of the respondents incorrectly labeled more than half of the generated samples. Analyzing students’ scores reveals that their results again span the lowest and highest achieved scores among all, with the greatest concentration at the lowest score of 12, which is a surprisingly poor result. Furthermore, 45.45% of their scores lie in the range of 24 to 30. Regarding analysts, their scores fall within the range of 14 to 30, with 50% of the results between 20 and 24, which is still below the bounds of chance. True positives analysis, in particular, highlights the quality of the generated text and the extent to which, despite factual misinformation, it can mislead individuals with knowledge of cybersecurity.

Figure 5.

Distribution of Classification Outcomes Across Cybersecurity Students. (a) True Positives Distribution. (b) True Negatives Distribution. (c) False Positives Distribution. (d) False Negatives Distribution.

Figure 6.

Distribution of Classification Outcomes Across Cybersecurity Analysts. (a) True Positives Distribution. (b) True Negatives Distribution. (c) False Positives Distribution. (d) False Negatives Distribution.

Figure 5b and Figure 6b demonstrate the distribution of true negatives, characterizing correctly recognized human-written CTIs for students and analysts, respectively. The results are slightly better compared to true positives, falling in the range 19–37 out of 50. The most significant number of participants scored a value of 28. This time, only 23.81% of all respondents misclassified more than half of the real samples. The average score is 28.62 with a standard deviation of 4.99, with most responses concentrated in the range of 28–34. Considering the students’ scores, their results are more scattered, with four representatives scoring between 18 and 24, and seven scoring between 28 and 38. This indicates that 63.64% of the students correctly recognized at least 56% of the real CTIs. Taking into account the analysts’ results, the lowest value achieved was 23, and the highest was 35. The average results are better than those of the students, with 90% of the responses exceeding the threshold of 50% correct classifications. These results indicate better stability in the answers of the experienced respondents. Although participants performed better with real text recognition compared to generated text, a significant number of misclassifications still occurred, even for authentic samples. However, it was generally easier to identify the real text than the artificial one, which suggests that the generated texts convincingly imitate the real ones.

Figure 5c and Figure 6c illustrate the distribution of false positives, which are incorrectly classified human-written instances as generated ones. The histograms are presented for all participants, as well as separately for students and analysts. The scores range from 13 to 31, resulting in a notably dispersed distribution of the results. The situation is the opposite of the one previously described, meaning 76.19% of the respondents incorrectly considered the real text as generated in less than half of the cases. In particular, only 14.29% of the individuals correctly labeled 70% or more human-written CTIs. The average number of false positives was 21.38 with a standard deviation of 4.99. The highest concentration of results falls within the range of 17 to 23, indicating that 57.14% of the respondents. The students responded differently again, with 45.45% having unique results. The highest number of authentic texts considered synthetic was in the range of 30 to 32 out of 50, and this result was obtained by 18.18% of students. Additionally, seven out of 11 students misclassified at most 48% of the examples. In contrast, eight out of 10 analysts incorrectly identified no more than 46% of the real CTIs, resulting in fewer extreme mistakes. The analysts’ experience allowed them to recognize real texts more accurately, thanks to their familiarity with cybersecurity reports, and misclassify them less frequently.

The final analysis includes Figure 5d and Figure 6d, demonstrating the distribution of false negatives, which are AI-generated texts classified as human-written. These plots present the scores for all representatives, students, and analysts accordingly. This analysis is deemed the most interesting, as it depicts the number of misleading CTIs that resemble the real ones, resulting in astonishing results. The score distribution ranged from 20 to 38 out of 50, with four individuals misidentifying 36 to 38 generated texts as written by humans. As many as 16 of 21 respondents misclassified more than half of the synthetic texts, while eight of them labeled at least 70% of the generated samples as real. The average false negatives score was 28.67 with a standard deviation of 5.47. Regarding the students, 72.73% of them erroneously identified between 40% and 68% of the generated CTIs, while the rest of them misclassified as much as 76%. In addition, 7 out of 11 students achieved the false negatives score above 50%. Contrasting these results with analysts’ responses, 60% of them fall within the range of 28 to 34, with three others achieving 20 to 26 false negatives, and the remaining one with a surprising value of 36. This indicates that 80% of the cybersecurity analysts labeled at least 50% of the synthetically created samples as genuine ones. Although the students generally performed worse, this time a larger percentage of analysts were misled by the output of the prepared CTI generator in at least half of the cases.

Analyzing all human responses, which included only people with knowledge of cybersecurity, they encountered significant difficulties in identifying AI-generated CTI samples. Although experienced in this field, only a few were not misled. Even though the information included in the selected samples was not always factually correct, it effectively resembled the real ones. This highlights the possibility of a data poisoning attack being conducted on open-source data, also indicating AI’s potential. Regarding the best and worst generated texts, the samples predominantly classified as real included personal voice expressions or a large number of technical terms with proper names. On the other hand, descriptions with a significant amount of extensive enumerations were more often considered generated. When it comes to misclassified real samples, respondents tended to lean toward the generated label, likely influenced by strange and unpredictable term names or a lack of technical details.

6.3. Large Language Models’ Evaluations

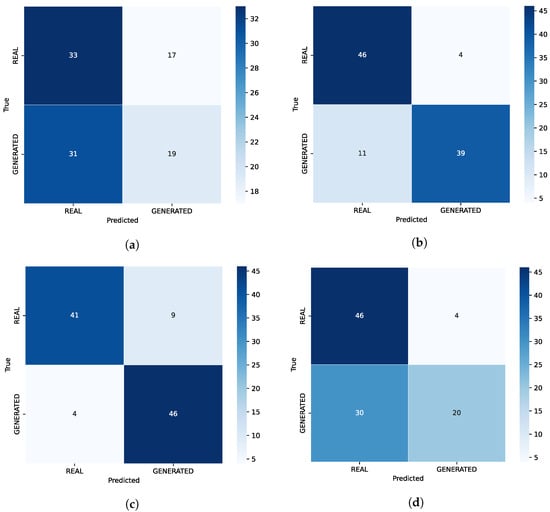

Additionally evaluation was performed using four large language models, each tasked with identifying the same 100 samples as real or generated. The answers came from Chat GPT 4o, Claude Sonnet 4, Gemini 2.5 Flash, and Llama 4, whose confusion matrices are presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Confusion Matrices for Different Large Language Models on the Survey Dataset. (a) Chat GPT 4o. (b) Claude Sonnet 4. (c) Gemini 2.5 Flash. (d) Llama 4.

The first model—Chat GPT 4o—achieved an accuracy of 52%, including 33 true negatives and 19 true positives. More than 60% of the generated samples were misclassified as human-written, and 34% of the real samples were labeled as artificial. This suggests that the predictions of a popular language model about synthetic samples were worse than those of average humans, even though the model performed better in genuine CTI recognition. The Claude model correctly classified as many as 46 human-written CTIs and 39 of the generated ones, achieving an accuracy of 85%. Only four of the real samples were incorrectly labeled as artificial, and merely 11 of the synthetic texts were identified as real. The results are very satisfactory. Accuracy reached by Gemini model is 87%, with 9 false positives and only four false negatives. Despite not being fine-tuned with cybersecurity-domain data, the model was able to immediately distinguish most of the given samples. This confirms that sometimes using large models gives better results than using smaller ones, as they may possess more background knowledge. Llama model achieved an accuracy of 66%. It correctly classified 46 real samples, matching the true negatives value of the Claude model. However, it missed 60% of the generated CTIs, resulting in the second-worst result among the evaluated models. The study using this particular model was also interesting, since the model belongs to the Llama family as the generator, but with significantly more parameters.

6.4. Discussion

Upon a discussion of all the results, it can be stated that the generative model was effectively fine-tuned to the cybersecurity domain. It produced high-quality and extremely misleading cyber threat intelligence texts. The most satisfying result is the high rate of incorrect classification for both cybersecurity students and cybersecurity analysts, as well as for two large language models. However, two other models were able to distinguish between generated and real content exceptionally well. These models are not open-source models that could be fine-tuned for experiments. To further improve the generator, interactions and tests using those could be conducted.

This research introduces several innovations compared to previous research. Primarily, it provides a comprehensive and thorough evaluation of the generated CTI samples using a custom-developed detection system, cybersecurity experts, and available large language models. This approach offers a broader and more objective evaluation scope than prior studies. Additionally, it demonstrates the detection system’s generalization capabilities, rather than relying only on the evaluation with the test set. Furthermore, it shows that a high-quality generative model tailored for the cybersecurity domain can be built with limited hardware resources and a small language model. Last but not least, the research environment and hardware specifications used in the study are described in detail.

Regarding the GPT-2 generator from, its perplexity result was 35.9, while TinyLlama, fine-tuned in this work, achieved 10.78, indicating the model’s greater confidence in the generated content. Comparing their human evaluations, the results are similar: the average precision was 47.5%, while in this research it was 49.95%. The authors mentioned that 78.5% of the synthetic samples were classified as real. Considering detection system performance, the test data achieved results similar to those inthe research by Gakpetor et al. [10], where an accuracy of 99.59%, an F1-score of 99.4%, and an AUC of 0.99 were reported. Although this research achieved both accuracy and F1-score of 98.5%, and an AUC of 0.99, these results are slightly worse, but with well-balanced classes and domain-specific data. Also inthe research by Nguyen et al. [12], Random Forest and XGBoost models scored an accuracy and F1-score above 99%; however, these models were also trained and tested on general texts (e.g., from Wikipedia). Compared to the study by Qian et al. [6], the developed hybrid detection system outperformed the researchers’ model, which achieved an F1-score of 95.6% for synthetic CTI samples and 90.9% for human-written ones. Also Li et al. study [7] results were worse: F1-score of 96.9% for detecting synthetic CTIs and 88.4% for the real, while in the study conducted by Han et al. [8] GAN’s average accuracy score was 90%. Contrasting with the CNN model from the work by Chandana et al. [11], it achieved an accuracy and F1-score of 97%, being the best score of that research. In the research by Alamleh et al. [13], Random Forest also had lower performance and achieved an accuracy of around 93%, while BERT was at 70%.

During testing on a pre-trained model-based dataset, the detector achieved the metrics values in the range of 88% to 89%. Drawing a comparison between the developed detection system and the tested large language models, Claude and Gemini excelled on the survey-based dataset. They achieved a better balance of precision and recall between the real and generated CTI samples. However, these models have a deeper understanding of the general data, due to their significantly larger sizes. To enhance the effectiveness of the detection system, a greater amount of high-quality cybersecurity data is needed, which is challenging to obtain with AI-limited hardware. Although detection accuracy was high, many of the generated samples were of low quality. Furthermore, the decision to switch models in the hybrid detection system is purely an empirical choice and may not generalize across all data. This suggests a need for further refinement to more reliably detect misinformation based on substantive analysis of the underlying content. Most problems arise from the limitations of the dataset, including its size and diversity.

Regarding human-based assessment, our results (mean accuracy approx. 50%) align with recent studies, showing that even experts struggle to discriminate artificially generated CTI from authentic ones. This is reflected in research by Jakesch et al. [42], which demonstrates that people rely on flawed heuristics and frequently judge AI text as “more human than human,” helping to explain our elevated false negatives. Similar misperception appears in the study by Herbold et al. [43] where ChatGPT essays were rated higher than human-written ones, showing how polished machine prose can mask factual weaknesses. A reviewby Kehkashan et al. [44] concludes that effective detection is achievable only when multiple techniques and provenance cues are combined and adapted to context—mirroring our detector’s advantage over human assessment. Complementing this, Cohen et al. [45] show that reciprocal human-AI collaboration improves CTI detection accuracy and experts’ conceptual understanding over time, supporting integrated human-AI validation. It is also worth to mention a study conducted by Ranade et al. [4] where the 10 specialists in the surveys received 28 human-written samples and 28 generated samples to label as real or generated—the results show that only 47.5% of the samples were correctly classified, while 78.5% of the generated samples were incorrectly recognized as genuine.

On the one hand, recent studies show that human evaluation of AI-generated content remains unreliable. On the other hand, LLMs are more and more integrated into information systems and everyday communication. Therefore, rigorous empirical research comparing human judgment with automated detection becomes crucial for the social sciences. Our hybrid detection model’s strong performance demonstrates a technical advance and necessary social intervention helping preserve epistemic integrity, i.e., maintain the capacity to reliably distinguish truth from falsehood in a world where synthetic texts proliferate. Only through ongoing, interdisciplinary studies we can map how trust, perceived credibility, and AI-generated content co-evolve over time and in various contexts [46,47].

7. Conclusions

The term of synthetic cyber threat intelligence generation is continuously growing, with scientific interest in the current study landscape, especially regarding the contribution of language models to this topic. The research presented in this paper focused not only on the generation process but also on the multifaceted evaluation, which included a self-developed detection system, four publicly accessible large language models, and a human assessment involving more than 20 cybersecurity-related participants. The results demonstrated that even the use of a small language model, fine-tuned on a relatively limited corpus of threat reports, can mislead cybersecurity specialists and some AI systems. However, the developed detection system, as well as two of the employed LLMs, were able to identify most of the generated texts.

The evaluation performed indicates that the fine-tuned TinyLlama can generate high-quality misinformation on cyber threats. The most substantial indications of this are human assessment scores, with an average accuracy of 49.95 ± 5.08% in distinguishing between 50 human-written and 50 TinyLlama-generated CTI descriptions. In particular, an average of 57.33 ± 10.94% of generated samples were misclassified as genuine ones. Additionally, the Chat GPT and Llama models also encountered issues in CTIs’ identification. However, Gemini and Claude Sonnet performed exceptionally well. Furthermore, a developed hybrid BERT-based detection model demonstrated efficiency in detecting synthetic samples, scoring 98.5% for various metrics, including accuracy, F1-score, and F2-score, on the test set. The results of the generalization test show an accuracy of 88.5% and 88.4% for both the F1 and F2 scores. Slightly lower performance was observed on the survey set; however, none of the other models was able to recognize all generated samples, as the introduced model did. The results obtained demonstrate satisfactory performance of both models, especially when developed with limited resources.

In order to further improve the generative model, it could be optimized using the best-performing detection model on the selectively chosen survey samples—the Gemini model. It turned out to be excessively powerful, even though its purpose is text generation, not classification tasks. TinyLlama could also be fine-tuned with an extended corpus, including additional threat intelligence details such as attack techniques from the MITRE ATT&CK framework. The detection system refinement should first focus on gathering significantly more training data, notably highly realistic samples, rather than all possible generations, and should also include revising the model-switching process. Additionally, the outputs of other models could also be utilized to enhance the detector’s flexibility and versatility.

In conclusion, cybersecurity-related misinformation generation can be easily achieved by employing even resource-effective and quantized language models. This poses a significant risk to currently used AI-based cyber defense systems, as well as to experienced threat hunters. Since verifying content-rich open-source platforms is almost impossible, validation should be performed at the entry point of the corporate infrastructure. It is noteworthy that such research can play a crucial role in outlining the possible threat landscape, as well as in preparing for even more difficult-to-detect data poisoning attacks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.P. and M.N.; methodology, Z.P., K.M. and M.N.; software, Z.P.; validation, Z.P. and M.N.; formal analysis, Z.P.; investigation, Z.P. and M.N.; resources, Z.P.; data curation, Z.P.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.P., K.M. and M.N.; writing—review and editing, Z.P., K.M. and M.N.; visualization, Z.P.; supervision, K.M. and M.N.; project administration, M.N.; funding acquisition, M.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by the Research Council of Lithuania (LMTLT) under Grant Agreement no. P-ITP-25-12.

Data Availability Statement

The code for presented work can be fount at https://github.com/zuza571/AI-Generated-CTI (accessed on 22 October 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- OWASP Foundation. ML02:2023 Data Poisoning Attack. 2023. Available online: https://owasp.org/www-project-machine-learning-security-top-10/docs/ML02_2023-Data_Poisoning_Attack (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak, Z. AI Generated CTI. Available online: https://github.com/zuza571/AI-Generated-CTI (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Ranade, P.; Piplai, A.; Mittal, S.; Joshi, A.; Finin, T. Generating Fake Cyber Threat Intelligence Using Transformer-Based Models. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Shenzhen, China, 18–22 July 2021; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Z.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hao, Y. Generating Fake Cyber Threat Intelligence Using the GPT-Neo Model. In Proceedings of the 2023 8th International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Signal Processing (ICSP), Xi’an, China, 21–23 April 2023; pp. 920–924. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, J.; Zhao, Y.; Cheng, S.; Li, Z. Data-Poisoning-Attack Oriented Fake Cybersecurity Threat Intelligence Detection Models and Algorithms. Technical Report, SSRN. 2025. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5113282 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Li, Z.; Yu, X.; Zhao, Y. A Web Semantic Mining Method for Fake Cybersecurity Threat Intelligence in Open Source Communities. Int. J. Semant. Web Inf. Syst. 2024, 20, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Jiang, R.; Li, C.; Huang, Y.; Chen, K.; Yu, H.; Li, A.; Han, W.; Pang, S.; Zhao, X. AT4CTIRE: Adversarial Training for Cyber Threat Intelligence Relation Extraction. Electronics 2025, 14, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Gao, Y.; Li, X. DACTI: A Generation-Based Data Augmentation Method for Cyber Threat Intelligence. In Proceedings of the 2023 8th International Conference on Data Science in Cyberspace (DSC), Hefei, China, 18–20 August 2023; pp. 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gakpetor, J.M.; Doe, M.; Damoah, M.Y.S.; Damoah, D.D.; Arthur, J.K.; Asare, M.T. AI-Generated and Human-Written Text Detection Using DistilBERT. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE SmartBlock4Africa, Accra, Ghana, 30 September–4 October 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chandana, I.; Reshma, O.M.; Sree, N.G.; Reddy, B.J.; Shareefunnisa, S. Detecting AI Generated Text. In Proceedings of the 2024 2nd World Conference on Communication & Computing (WCONF), Raipur, India, 12–14 July 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Hatua, A.; Sung, A.H. How to Detect AI-Generated Texts? In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 14th Annual Ubiquitous Computing, Electronics & Mobile Communication Conference (UEMCON), New York, NY, USA, 12–14 October 2023; pp. 0464–0471. [Google Scholar]

- Alamleh, H.; AlQahtani, A.A.S.; ElSaid, A. Distinguishing Human-Written and ChatGPT-Generated Text Using Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 Systems and Information Engineering Design Symposium (SIEDS), Charlottesville, VA, USA, 27–28 April 2023; pp. 154–158. [Google Scholar]

- Borylo, P.; Cholda, P.; Domzal, J.; Jaglarz, P.; Jurkiewicz, P.; Lason, A.; Niemiec, M.; Rzepka, M.; Rzym, G.; Wojcik, R. SDNRoute: Integrated system supporting routing in Software Defined Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 19th International Conference on Transparent Optical Networks (ICTON), Girona, Spain, 2–6 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kurek, T.; Niemiec, M.; Lason, A. Taking back control of privacy: A novel framework for preserving cloud-based firewall policy confidentiality. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2015, 15, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemiec, M.; Kościej, R.; Gdowski, B. Multivariable Heuristic Approach to Intrusion Detection in Network Environments. Entropy 2021, 23, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ettinger, J.; Barmer, H.; Kane, J.; Evans, H.; Brandon, E.; Mellinger, A.O. Cyber Intelligence Tradecraft Report: The State of Cyber Intelligence Practices in the United States (Study Report Only); Educational Material; Software Engineering Institute: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, S.; Suayyid, S.A.; Al-Ghamdi, M.S.; Al-Muhaisen, H.; Almuhaideb, A.M. A Systematic Literature Review on Cyber Threat Intelligence for Organizational Cybersecurity Resilience. Sensors 2023, 23, 7273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khurana, N.; Mittal, S.; Joshi, A. Preventing Poisoning Attacks on AI based Threat Intelligence Systems. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.07418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Service, E.P.R. Automated Tackling of Disinformation; Technical Report; European Parliament, Directorate-General for Parliamentary Research Services: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- EDPS. Fake News Detection; Technical Report, TechSonar Report; EDPS: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Zhao, H.; Liu, W.; Ding, X. Research on False Information Detection Based on Multimodal Event Memory Network. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Consumer Electronics and Computer Engineering (ICCECE), Guangzhou, China, 6–8 January 2023; pp. 566–570. [Google Scholar]

- Jurafsky, D.; Martin, J.H. Speech and Language Processing: An Introduction to Natural Language Processing, Computational Linguistics, and Speech Recognition with Language Models; 3rd edition (draft); 2025; Available online: https://web.stanford.edu/~jurafsky/slp3/ed3book_aug25.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All You Need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Zeng, G.; Wang, T.; Lu, W. TinyLlama: An Open-Source Small Language Model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.02385. [Google Scholar]

- Face, H. Hugging Face Transformers Documentation. Available online: https://huggingface.co/docs/transformers/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Han, D.; Han, M.; Unsloth Team. Unsloth. 2023. Available online: http://github.com/unslothai/unsloth (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Wolf, T.; Debut, L.; Sanh, V.; Chaumond, J.; Delangue, C.; Moi, A.; Cistac, P.; Rault, T.; Louf, R.; Funtowicz, M.; et al. Transformers: State-of-the-Art Natural Language Processing. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing: System Demonstrations, Online, 16–20 October 2020; pp. 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- APT Notes Repository. Available online: https://github.com/kbandla/APTnotes (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Tools for APT Notes Downloading. Available online: https://github.com/aptnotes/tools (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Team, P.D. PyPDF2: A Python Library for PDF Files. Available online: https://github.com/py-pdf/pypdf (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Rahman, M. CTI-Reports Dataset. Available online: https://huggingface.co/datasets/mrminhaz/CTI-Reports (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Satya. CTI RCM 2021 Dataset. Available online: https://huggingface.co/datasets/skrishna/cti-rcm-2021 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Tools, C.A. ORKL Cleaned 10k Dataset. Available online: https://huggingface.co/datasets/ctitools/orkl_cleaned_10k (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Schwankner, A. Cyber Threat Intelligence Dataset. Available online: https://huggingface.co/datasets/mrmoor/cyber-threat-intelligence (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Schwankner, A. Cyber Threat Intelligence Splited Dataset. Available online: https://huggingface.co/datasets/mrmoor/cyber-threat-intelligence-splited (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Schwankner, A. Cyber Threat Intelligence Relations Only Dataset. Available online: https://huggingface.co/datasets/mrmoor/cyber-threat-intelligence-relations-only (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Puri, A. Threat Intel Dataset. Available online: https://huggingface.co/datasets/aayushpuri01/threat-intel-dataset (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Wei, C.H. Cyber MITRE Tactic CTI Dataset. Available online: https://huggingface.co/datasets/sarahwei/cyber_MITRE_tactic_CTI_dataset_v16 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Sanh, V.; Debut, L.; Chaumond, J.; Wolf, T. DistilBERT, a distilled version of BERT: Smaller, faster, cheaper and lighter. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1910.01108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Jakesch, M.; Hancock, J.T.; Naaman, M. Human heuristics for AI-generated language are flawed. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2208839120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbold, S.; Hautli-Janisz, A.; Heuer, U.; Kikteva, Z.; Trautsch, A. A large-scale comparison of human-written versus ChatGPT-generated essays. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kehkashan, T.; Riaz, R.A.; Al-Shamayleh, A.S.; Akhunzada, A.; Ali, N.; Hamza, M.; Akbar, F. AI-generated text detection: A comprehensive review of methods, datasets, and applications. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2025, 58, 100793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.; Te’eni, D.; Yahav, I.; Zagalsky, A.; Schwartz, D.; Silverman, G.; Mann, Y.; Elalouf, A.; Makowski, J. Human–AI Enhancement of Cyber Threat Intelligence. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2025, 24, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Q.; Li, G. Unveiling trust in AI: The interplay of antecedents, consequences, and cultural dynamics. AI Soc. 2025, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, M.T.; Aichner, T. In generative artificial intelligence we trust: Unpacking determinants and outcomes for cognitive trust. AI Soc. 2025, 40, 5849–5869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).