Abstract

Recycling education is important for promoting pro-environmental sustainable behavior, yet traditional approaches often lack engagement and impact, particularly among younger audiences. This study presents a digital, turn-based card strategy game designed to teach recycling principles and concepts through interactive city-building mechanics. Set in an augmented reality environment, the game challenges players to balance population growth, resource use, and waste management to maintain a high well-being score for their city. Players construct digital buildings (houses, recycling facilities, resource infrastructures), each influencing waste production, recycling efficiency, and overall well-being. The game integrates educational content with engaging decision-making, aiming to foster system thinking and eco-conscious behavior. Unlike prior AR approaches, this game focuses on digital interaction, leveraging immersive game-based learning. Usability and engagement were evaluated using the in-game version of the Game Experience Questionnaire (GEQ). Findings support that users responded positively to the prototype’s game experience, suggesting that the digital game is promising. The study contributes to the growing field of digital pro-environmental education, providing insights into how interactive gameplay can support environmental awareness and laying groundwork for future evaluation of its educational impact.

1. Introduction

The serious games field is evolving rapidly, driven by technological advancements such as new mobile technologies and the bloom of augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR). The growing demand for interactive and engaging learning tools across different disciplines has resulted in a significant global acceleration in serious games’ popularity and has created a market size of 13 billion USD in 2024 [1]. Along with the worldwide increased interest in serious games, environmental serious games have also grown. An analysis of serious games for pro-environmental sustainable education revealed a significant increase in scholarly interest, with a sharp surge becoming evident in the number of relevant publications from 2021 onwards [2].

A substantial body of research has highlighted multiple benefits of using serious games in environmental awareness and education. More specifically, it has been documented that environmental serious games can effectively foster greater ecological concern [3], enhance environmental-related knowledge [4,5], encourage critical thinking skills for addressing sustainability challenges [6] and promote pro-sustainable and pro-environmental actions and behaviors [7,8].

An overview of the available serious games on environmental issues revealed that among the most common subjects were climate change, waste management, urban planning, and ecosystem management [9]. In the overview, the serious games narratives varied vastly; however, it was noteworthy that many of these games portray ordinary citizens tasked with making pro-environmental sustainable choices in their daily lives, such as recycling, conserving energy, or water. Regarding the design features of environmental serious games, a recent review highlights that the most effective examples tend to incorporate a distinct set of characteristics. These include immersive experiences, meaningful player engagement, active learning through doing, realistic simulations of environmental challenges, decision-making autonomy, and the presence of a guiding host [10]. Collectively, these features support deeper learning, sustained interest, and stronger behavioral outcomes in players.

A state-of-the-art short review reveals a number of serious games designed to promote pro-environmental behaviors, particularly recycling and waste management, as well as the use of AR to enhance user’s engagement and learning outcomes. Examples include city management simulation games, competitive recycling challenges, and AR-based interactive games that combine physical and digital elements [11,12,13]. These prior initiatives provide a foundation for understanding how game mechanics and immersive technologies can support pro-environmental sustainable education and motivate our approach of integrating AR in a board game context.

Given the increasing need to provide new ways to engage and involve young people in pro-environmental behaviors, and to increase the efficiency of environmental awareness and education [14], we decided to develop a recycling themed serious game integrating educational content with engaging decision-making to foster system thinking and eco-conscious behavior in young people. The topic of the serious game was selected due to the persistent and pressing nature of waste management as a global environmental challenge. Indeed, the United Nations supports that global solid waste generation is projected to increase by 81% between 2020 and 2050 as a result of economic growth and unsustainable consumption, highlighting this environmental urgency and the need to address it [15].

Furthermore, managing waste responsibly is something every person can contribute to in their daily life, and recycling is a tangible action. Although public awareness on the matter is not low, meaningful engagement is limited. An AR game is considered as a promising medium of behavioral change, since young players can directly apply what they learned in the serious game in real life, leading to measurable impacts. This attribute has been emphasized by several studies [16,17] that reported that AR can influence behavioral change, particularly in environmental education and alter attitudes towards sustainability encouraging pro-environmental actions. Furthermore, AR technology affects learners’ spatial awareness, which is crucial for behavioral change in real-world contexts [18].

Considering all the above, we designed and developed an AR city builder game that promotes sustainable recycling behaviors, while at the same time, it provides a fun and engaging city planning experience. The game is a turn-based card strategy game featuring a user-centered AR interface, designed for city building and waste management infrastructure planning allowing students to place recycling facilities, optimize waste flows, and observe simulated environmental outcomes overlaid on their physical environment. The aim of this study was twofold: (1) to engage players in pro-environmental sustainable urban planning decisions and (2) to encourage recycling behaviors through an immersive and interactive game. Overall, this paper describes the design principles, development, and implementation of the “Bin There, Built That: The Game”, highlighting how AR as an end-user technology can be leveraged to foster environmental awareness while remaining user-friendly and contextually grounded.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Game Design

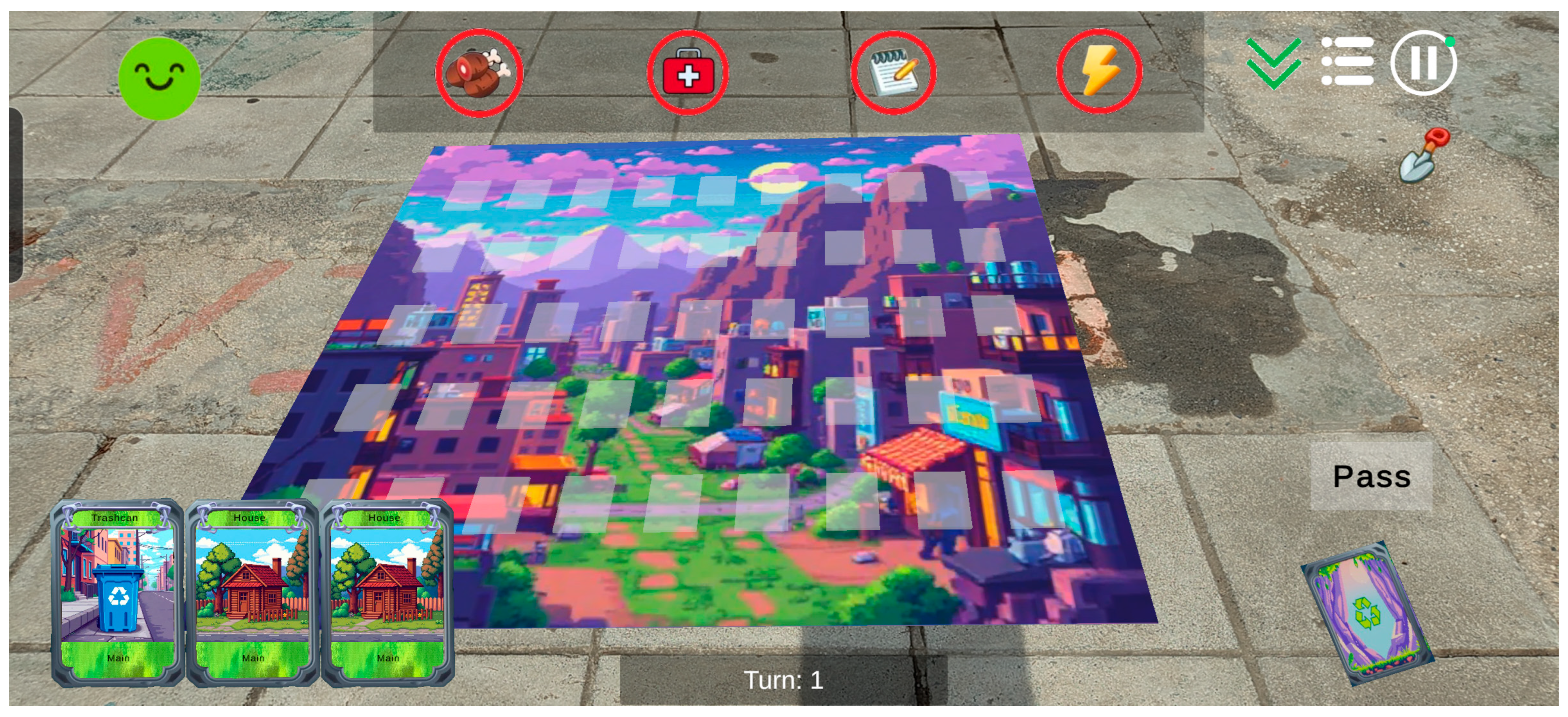

The game is a single-player, turn-based, and relaxing strategy experience where the player’s primary goal is to build and manage a sustainable city (see Figure 1). At the start of each session, the player begins with five cards and draws one additional card per round. During each turn, the player can either play a card or skip the turn to draw another one. The objective is to achieve the highest possible happiness score, ranging from 0 to 100, by effectively managing population growth, resources, waste, and recycling. The game concludes when the happiness score remains below 40 for more than five consecutive rounds, signifying that the city’s population has become unhappy and the player’s management strategy has failed.

Figure 1.

Starting the game with an empty board and 3 random drafted cards.

The happiness system serves as the core metric of the city’s well-being and reflects the player’s ability to maintain a balance among population, resources, and waste management. The happiness score starts at a predefined value, defined as 70, and fluctuates between 0 and 100 depending on player decisions. Several factors influence happiness: the types of buildings constructed, the adequacy of essential resources, and the effectiveness of waste management actions. A lack of resource buildings or excessive accumulation of waste results in a steady decline in the happiness score, while well-balanced resource allocation and waste reduction contribute to its increase.

The game’s cards were divided into 3 categories: the main cards, special cards, and basic cards. The main cards include bins, houses and recycling facilities. The special cards contain buildings required for a functioning society (hospitals, schools, energy facilities and restaurants). Basic cards are buildings that upgrade the quality of life (such as playgrounds, gas stations and shops).

House cards, representing population units, are essential for expanding the city and enabling the construction of more complex buildings. Each house card placed increases the population but also generates waste. Houses can be upgraded through three levels, with each level improving waste efficiency. A Level 1 house accommodates five people and produces three units of waste. Upgrading to Level 2 adds five more residents (a total of ten) while reducing waste to two units, and Level 3 increases the total population to fifteen while generating only one unit of waste. Upgrades require specific conditions such as a minimum population size or the existence of previous upgrade levels. Certain other building types, such as resource and happiness buildings, also require a minimum population before construction can begin.

Waste management plays a critical role in sustaining the city’s happiness. Garbage bins are used to store the waste generated by buildings, but they can only be emptied if recycling facilities are operational. When bins exceed half of their capacity, the city enters a first penalty stage, resulting in a gradual decline in happiness. If the bins become completely full, a second penalty stage is triggered, causing a sharper decrease in happiness. Recycling facilities mitigate these penalties by processing waste, increasing bin capacity, and improving recycling efficiency. Upgraded recycling centers also reduce waste produced by happiness buildings, further stabilizing the city’s well-being.

Resource buildings (including supermarkets, hospitals, schools, and energy factories) are essential to maintaining population baseline happiness. If any of these are absent, the city suffers a penalty of losing two happiness points per round for each missing building. When present, each building contributes two happiness points per round. These effects can be further enhanced through recycling upgrades: for example, supermarkets gain an additional one to two happiness points when plastic or organic waste recycling is active, hospitals benefit from textile and medical waste recycling, schools improve through paper and textile recycling, and energy factories gain bonuses from metal and electronic waste recycling. These synergies emphasize the link between sustainable resource management and overall happiness.

Buildings that increase happiness (such as restaurants, gas stations, playgrounds, and stores) provide a direct increase in happiness score but at the same time produce waste. Each building contributes two happiness points but also generates three units of waste. The waste can be reduced by one unit through recycling system upgrades, although such upgrades do not enhance the happiness itself. This balance forces players to consider not only how to increase happiness, but also how to offset the waste consequences of doing so. Figure 2 presents the game at a later stage with upgraded buildings as well as resource buildings and budlings for increasing happiness levels. Additionally, it presents the waste carrier truck picking the garbage from the trashcans transferring them into recycle facility.

Figure 2.

Game at advanced level with many buildings created around the board.

The building types and the game rules in “Bin There, Built That” were designed to create a meaningful connection between the card-strategy mechanics and real-world recycling and pro-environmental sustainable behaviors. Each building in the game (houses, resource buildings, and happiness-increasing buildings) was chosen to represent key aspects of urban management, including population growth, resource allocation, and waste production and management. The rules governing their construction, upgrades, and interactions emphasize the consequences of unsustainable practices: for example, unchecked population expansion or failure to provide recycling facilities leads to increased waste and a decline in overall city happiness.

The card-draw and turn-based mechanics encourage strategic planning, requiring players to make decisions that balance growth with environmental responsibility. By linking happiness directly to the adequacy of resources and effectiveness of waste management, players experience firsthand how sustainable decisions affect overall city well-being. Recycling facilities and upgrades are embedded within the gameplay to reinforce cause-and-effect relationships.

Overall, the game’s design simulates real-world trade-offs in a simplified but meaningful way, allowing players to internalize sustainability principles through interactive decision-making. The rules and building types are thus not arbitrary; they were specifically designed to create an educational experience where players’ strategic choices reflect the challenges of balancing population needs, resource management, and environmental responsibility. This alignment ensures that the “Bin There, Bult that” card-strategy game supports learning objectives related to recycling behavior and pro-environmental urban planning.

The player loses the game if the happiness score remains below 40 for more than five consecutive rounds. Poor waste management and lack of recycling can also lead to a rapid decline in happiness, ultimately resulting in the collapse of the city. Consequently, success depends on the player’s ability to balance population growth, waste reduction, and resource availability. These interconnected systems make the gameplay both challenging and rewarding, encouraging players to think strategically about pro-environmental sustainability, resource use, and environmental responsibility while striving to achieve the highest happiness score possible.

2.2. Game Development

The game was developed in Unity using AR Foundation, enabling physical-digital interactions through the mobile touchscreen. The game utilizes the platform’s default plane detection, which is SLAM for Android. Visual feedback is provided for the detected planes, and once the user places the board, users have the option to hide it. The board is then anchored to a fixed world location, and plane detection continues in the background to enhance environmental understanding and improve tracking stability.

Players interact with the virtual board by dragging and placing cards, with each turn terminating when a card is played. Visual assets for buildings and cards were created in Blender and integrated to ensure a clear and aesthetically pleasing presentation. Animations enhance the gameplay by providing visual feedback when buildings are spawned or upgraded, adding a sense of “action” to the otherwise turn-based mechanics. Gameplay elements, including cards, buildings, and their properties, were defined using Scriptable Objects for scalability and ease of modification. Waste management is represented dynamically through a garbage truck that traverses the board at the end of each turn, collecting waste from bins and transporting it to recycling facilities; the truck remains inactive if no recycling facility exists, reinforcing the importance of proper waste infrastructure in the game. Iterative playtesting was conducted to ensure that the mechanics, visual feedback, and AR interactions were intuitive and engaging for players.

2.3. Game Evaluation

To assess the initial usability, engagement, and learning potential of the game, a small-scale study within the Natural Interactive Learning Games and Environments Lab—Nile lab (https://nile.hmu.gr/, accessed on 31 October 2025) was conducted. The study aimed to provide formative insights into gameplay mechanics, AR interactions, and the clarity of educational content, rather than measuring long-term learning outcomes. Game usability and engagement were evaluated using the in-game Game Experience Questionnaire (GEQ). In-game GEQ is a standardized short questionnaire consisting of 14 quantitative items that assess the player’s experience and emotions. It is an effective tool for assessing game experience at multiple intervals after a game session, comprising seven components, mirroring those of the original GEQ questionnaire. Two items are used to assess each component, which are competence, Sensory and Imaginative Immersion, Flow, Tension, Challenge, Negative Affect and Positive Affect [19].

Participants were students, teachers, or research assistants who were asked to participate in the study via email, social media, or direct contact on campus. The participants were informed about the study’s objectives and provided informed consent before completing the questionnaire, which was provided by Google Forms. To protect their privacy, the study did not request personal identification information, and all collected data remained anonymous. Participants were allowed to use their own devices or to borrow one provided by the research team. The research team offered a device for the evaluation, while participants with their own could perform the evaluation remotely. The study was conducted in an uncontrolled environment, meaning participants engaged with the application in their natural environments rather than a controlled laboratory setting. The application addressed Android devices, and participants could download and install it through a shared Android Package Kit (APK) file. After exploring and interacting with the application’s activities, participants completed the GEQ scale and an additional qualitative survey including the questions presented in Table 1, allowing us to obtain a deeper understanding of participants’ insights and experiences beyond the structured questionnaire.

Table 1.

Qualitative Questions.

3. Results

A total of 8 participants (62.5% male and 37.5% female), aged between 24 and 49, took part in the pilot evaluation study. Study included a convenience sample of students and teachers/research collaborators that was deliberately chosen based on participants’ literacy in information technology and previous experience with serious games. Those characteristics enabled the participants to provide a comprehensive review of the game’s design aspects, identify inconsistencies, and uncover potential usability or interaction issues.

Each participant received a brief introduction to the game and its objectives, followed by a play session of approximately 10 min to validate interface design, navigation, stability, and overall user experience. During gameplay, participants interacted with the virtual board via the mobile touchscreen, playing cards, managing resources, and observing the effects of waste and recycling mechanics. Evaluation focused on players’ understanding of the rules, engagement with the AR interface, and ease of managing happiness and resources.

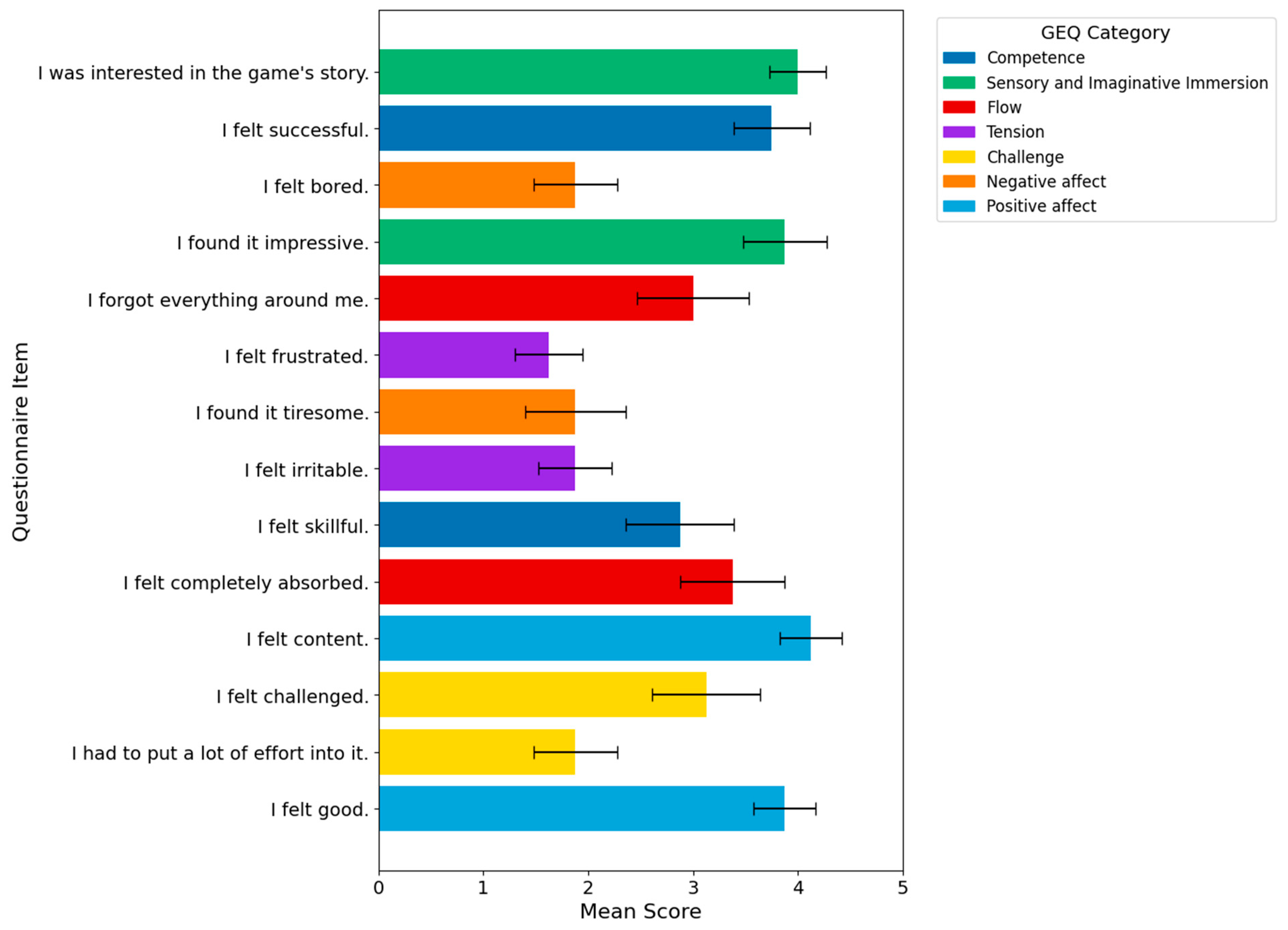

After the play session, participants completed the evaluation survey. The GEQ tool assessed players’ subjective experience across seven dimensions: Immersion, Flow, Competence, Challenge, Tension, Negative Experience (Boredom), and Positive Affect. Fourteen items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 5 = extremely) were administered to eight participants. For the quantitative analysis (see Table 2), we computed the average (Avg), standard deviation (SD), and standard error (SE) for each question using NumPy and visualized the results with Matplotlib.pyplot (3.10.0). All computations were performed in Google Colab, which provided a convenient and reproducible environment for data processing and visualization.

Table 2.

GEQ results (Average-Avg, Standard Deviation-SD, and Standard Error-SE).

According to the results, the players overall experience in “Bin There, Built That: The Game” was generally positive across GEQ dimensions. Immersion (Questions 1, 4, 5, 10) scores were moderate (M = 3.52), suggesting that players were interested in the game’s story and experienced a reasonable sense of absorption. Flow (Questions 10, 11, 14) was relatively strong (M = 3.80), indicating that players often felt content, good, and absorbed during gameplay. Competence (Questions 2, 9) levels were above the midpoint (M = 3.31), implying that players felt moderately skilled and successful. Challenge (Questions 12, 13) scores were low (M = 2.00), suggesting that the game did not require substantial effort and was not perceived as difficult. Negative affect/Tension (Questions 6, 8) was also very low (M = 2.00), with players rarely reporting frustration or irritability. Boredom (Questions 3, 7) indicators were similarly low (M = 1.88), showing that the game-maintained players’ interest throughout. Positive effect (Questions 11, 14) was the highest-scoring dimension (M = 3.94), indicating that players generally had a satisfying and enjoyable experience (Figure 3). Overall, the GEQ results suggest that the game produced a pleasant, low-stress, moderately immersive experience with strong positive emotional outcomes.

Figure 3.

Diagram presenting the mean response value per GEQ question (with Standard Error).

Participants also provided open-ended feedback on their understanding of the game mechanics, clarity of educational content, and AR interactions. This mixed-method approach allowed for a quick yet informative assessment of player experience and the educational potential of the game.

This pilot evaluation serves as an initial validation of the game prototype, providing actionable insights into usability, engagement, and educational clarity, and guiding the next stages of refinement and potentially larger-scale studies.

Using a thematic analysis, six themes were extracted from the qualitative responses, offering insights into players’ experiences with the AR-based eco-friendly city-building game. The first theme, Visual Appeal and Aesthetic Enjoyment, reflects the consistently positive reception of the game’s graphical style, with participants praising the bright colors, clear visuals, and satisfying animations that contributed to an engaging and playful atmosphere. The second theme, Enjoyable Core Mechanics, describes players’ appreciation of the simple yet rewarding interactions, such as dragging objects, placing buildings, and upgrading structures, which were reported as particularly engaging once the mechanics became clear. In contrast, the third and most dominant theme, Lack of Guidance and Tutorial, highlights a major usability gap. Many players expressed confusion about the game’s objectives, rules, and building requirements, indicating that the absence of an onboarding mechanism significantly hindered their ability to progress and reduced overall enjoyment. The fourth theme, AR Usability Challenges, reflects mixed experiences with the AR component; while some participants found the AR board accurate and immersive, others reported difficulties related to object placement, board stability, physical movement within the play space, and, in isolated cases, motion discomfort. The fifth theme, Feedback and Sensory Responsiveness, concerns the limited feedback provided by the system; players noted the lack of sound effects, unclear responses to interaction attempts, and insufficient cues regarding changes in city happiness or successful upgrades, which collectively reduced clarity and moment-to-moment satisfaction. Finally, the sixth theme, Desire for Feature Expansion and Increased Complexity, illustrates participants’ interest in deeper gameplay, including additional building types, more levels, improved environmental constraints, moving characters, and refined AR navigation features. Overall, while the game concept and aesthetic qualities were well-received, the findings indicate that user experience would be significantly improved by addressing guidance, interaction usability, and feedback clarity, thereby supporting more sustained engagement and deeper learning within the AR environment.

4. Discussion

Due to their immersive narrative and interactive nature, serious environmental games have significant potential to engage young audiences with complex future environmental sustainability challenges by enabling them to play characters who must think strategically, plan effectively, and make environmentally impactful decisions [20]. The most common pattern in existing recycling games within the pro-environmental sustainability domain involves structuring the game scenario around a central challenge that is divided into a series of progressively more difficult missions [9]. Generally, the overall aim of these games is to raise awareness, while at the same time they are designed to encourage shifts in attitudes and promote behavioral change.

Comparison to prior state-of-the-art reveals a number of serious games specifically designed to promote recycling behaviors; several representative examples are outlined below. The game “Gaea” [11] is a serious game centered around the task of recycling virtual objects spread around a virtual world. Upon recycling each item, players are provided with information related to that object. The game supports team-based, competitive play, aiming to influence specific pro-environmental behaviors. In the online serious game “Garbage Dreams”, players are responsible for managing Cairo’s city waste starting with one neighborhood, one factory, and one hungry goat. They have to build their recycling empire and maximize profits by recycling as much waste as possible. Players can invest in capabilities to recycle different types of materials, thereby enhancing their performance and experiencing the consequences of those decisions within the game context [12].

In the “Dumptown Game”, the player’s role is a newly appointed city manager tasked with transforming a heavily polluted and wasteful town into a sustainable community. The game involves implementing up to ten waste reduction and recycling programs, each with immediate visual and statistical feedback on the town’s environmental improvement. Players must balance environmental outcomes with budgetary constraints, fostering decision-making skills related to resource management, sustainability planning, and civic engagement [13].

In contrary to the above environmental game initiatives, we chose to integrate AR technology in the “Bin There, Built That: The Game” since it is proven that AR can significantly increase user engagement in board games by combining physical and digital elements [21] while at the same time enhancing retention and comprehension, reducing frustration and improving immersion [22]. Both studies suggest that AR creates a more interactive learning environment, which aligns with our goal of engaging students and improving their understanding of recycling and sustainability concepts. Additionally, literature suggests that sustainable education can be enhanced with AR technology, fostering more active participation and enhancing learning outcomes [23].

AR has also proven effective in simplifying complex educational content and making it more accessible. The integration of AR in a board game for teaching computational thinking showed a boost in students’ problem-solving abilities [24]. Similarly, another study demonstrated the potential of AR to improve waste sorting knowledge in Indonesia, with positive user feedback indicating its effectiveness in environmental education [17]. Finally, “Wasteworld” is another AR game where players are tasked with identifying and sorting virtual waste. Via AR animated trash bins placed in users’ rooms, it teaches children about waste sorting in a playful and engaging way [25].

Our project builds on these by using AR to simplify and gamify the process of learning about recycling and waste management, making it more accessible and engaging for children via an AR card board game. In general, board games are identified as effective learning environments for cultivating cognitive skills like problem-solving and teamwork, and AR is shown to enhance these benefits [17]. Indeed, literature supports that integrating AR into traditional game formats leads to a more interactive and engaging experience [21,24]. By combining AR with a physical board game, our project seeks to enrich the learning process and provide a more immersive educational experience in recycling. Additionally, AR in board games enhances education (such as health-related learning), contributing to the overall effectiveness of AR in educational game design [26]. Hence, literature emphasizes the impact of AR in learning environments even in difficult subjects such as chemistry [27], underscoring its potential to foster increased engagement in all kinds of educational activities including environmental education.

4.1. Limitations

This pilot study aimed to test the prototype version of the AR board game, utilizing a convenience sample enrolling members of the academic society (university students, teachers, researchers) who already possess higher technological literacy. The aim was to test game mechanics and game balance while validating interface design, navigation, stability, and overall user experience, which we considered essential prerequisites for responsibly involving younger audiences. Hence, the small number of the study sample size along with the lack of diversity in their background limits the generalizability of the findings, which should be interpreted as preliminary indicators rather than strong evidence. Furthermore, the pilot study focused on evaluating the game mechanics and overall game experience and did not assess changes in participants’ environmental knowledge, attitudes or behaviors. A follow-up study involving a larger, age-appropriate and more diverse sample is required to draw more robust and generalizable conclusions about the effectiveness of the game mechanics and user experience satisfaction along with examining the game’s effectiveness in enhancing environmental awareness and promoting pro-environmental sustainable behaviors.

4.2. Future Work

Upon completing this study, the first important step is to refine and improve the “Bin There, Built That: The Game” mechanics and gameplay according to the valuable feedback received during the prototypes’ pilot study. Future work should aim to address the limitations identified in the previous paragraph by providing a stronger and more comprehensive evaluation method. A larger scale study involving a more diverse and age-appropriate population is needed to enhance the generalizability of the findings and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the game’s effectiveness both in terms of usability but also of short term and long-term educational impact. This study should focus on the games’ effectiveness in fostering environmental knowledge and pro-environmental sustainable attitudes, offering valuable insights into the potential of AR-based games as tools for environmental education and behavioral change.

Finally, based on participants’ feedback, future versions of the game should integrate in-game tutorials and contextual guidance mechanisms. These features will provide clear instructions and support for new players, helping them understand game mechanics and objectives more quickly, and enhance overall engagement and user experience.

5. Conclusions

The present study aimed to evaluate overall game experience and assess game mechanics and balance of the “Bin there, Built That: The Game”, an AR turn-based card strategy game designed to support environmental awareness in young audiences. Unlike prior AR approaches, game innovation focuses on digital interaction and immersive game-based learning, with the results of the prototypes’ pilot study indicating that the game produced a pleasant, low-stress, moderately immersive experience with strong positive emotional responses. However, the current research did not measure changes in users’ environmental attitudes or behaviors. Future research is required to evaluate the game’s educational impact and measure changes in environmental behavior, both short and long-term, to prove that it is an easily accessible and highly engaging educational tool that can empower young users to redesign the world by playing today for the cities of tomorrow.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.L. and N.V.; methodology, I.L., I.A. and N.V.; investigation, I.L., I.A. and V.E.C.; data curation, I.L. and V.E.C.; writing—original draft preparation, I.L. and V.E.C. writing—review and editing, I.A., A.S. and N.V.; visualization, I.A. and I.L.; supervision, N.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived as the study involved non-interventional research with informed consent and anonymized data.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AR | Augmented Reality |

| APK | Android Package Kit |

| Avg | Average |

| GEQ | Game Experience Questionnaire |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SE | Standard Error |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

References

- Research and Markets. Serious Games Market Size, Share, Trends and Forecast by Gaming Platform, Application, Industry Vertical, and Region, 2025–2033. Available online: https://www.researchandmarkets.com/report/serious-gaming (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Ahmadov, T.; Karimov, A.; Durst, S.; Saarela, M.; Gerstlberger, W.; Wahl, M.F.; Karkkainen, T. A two-phase systematic literature review on the use of serious games for sustainable environmental education. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2024, 33, 1945–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, M.; Fernandes, J. Environmental sustainability: A study on the impact of information systems on game-based learning and gamification. In Proceedings of the 14th International Multi-Conference on Society, Cybernetics and Informatics Proceedings, Online, 13–16 September 2020; Callaos, N.C., Muirhead, B., Robertson, L., Sanchez, B., Savoie, M., Eds.; International Institute of Informatics and Systemics (IIIS): Winter Garden, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 203–207. [Google Scholar]

- Juan, Y.K.; Chao, T.W. Game-based learning for green building education. Sustainability 2015, 7, 5592–5608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, W.M. Increasing student engagement and comprehension of the global water cycle through game-based learning in undergraduate courses. J. Geosci. Educ. 2022, 70, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janakiraman, S. Digital games for environmental sustainability education: Implications for educators. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing Multiculturality, Salamanca, Spain, 21–23 October 2020; pp. 542–545. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V.; Tissenbaum, M.B.; Kim, T. Procedural collaboration in educational games: Supporting complex system understandings in immersive whole class simulations. Commun. Stud. 2021, 72, 994–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, T.H.C. Investigating effects of interactive virtual reality games and gender on immersion, empathy and behavior into environmental education. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 608407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouariachi, T.; Olvera-Lobo, M.D.; Gutiérrez-Pérez, J. Serious Games and Sustainability. In Encyclopedia of Sustainability in Higher Education; Leal Filho, W., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, C.K.W.; Nurul-Asna, H. Serious games for environmental education. Integr. Conserv. 2023, 2, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centieiro, P.; Romão, T.; Dias, A.E. A Location-Based Multiplayer Mobile Game to Encourage pro-Environmental Behaviours. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Advances in Computer Entertainment Technology—ACE ’11, Lisbon, Portugal, 8–11 November 2011; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Roussos, G.; Dovidio, J.F. Playing below the poverty line: Investigating an online game as a way to reduce prejudice toward the poor. Cyberpsychology 2016, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The United States Environmental Protection Agency. Dumptown Game. Available online: https://19january2017snapshot.epa.gov/www3/recyclecity/gameintro.htm (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Boncu, Ș.; Candel, O.-S.; Popa, N.L. Gameful Green: A Systematic Review on the Use of Serious Computer Games and Gamified Mobile Apps to Foster Pro-Environmental Information, Attitudes and Behaviors. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Global Waste Management Outlook 2024 Executive Summary: Beyond an Age of Waste—Turning Rubbish into a Resource; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2024; Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/handle/20.500.11822/44992;jsessionid=918E2AFCF436F7D4DB95F5D5FCB009F7 (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Feigl, T.; Porada, A.; Steiner, S.; Löffler, C.; Mutschler, C.; Philippsen, M. Localization Limitations of ARCore, ARKit, and Hololensin Dynamic Large-scale Industry Environments. In Proceedings of the VISIGRAPP (1: GRAPP), Valletta, Malta, 27–29 February 2020; pp. 307–318. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, M.Z.; Mangina, E.; Campbell, A.G. Current Challenges and Future Research Directions in Augmented Reality for Education. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2022, 6, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, T.; Hughes, N.G.J.; Fiebrink, R. How Boardgame Players Imagine Interacting with Technology. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2024, 8, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IJsselsteijn, W.A.; de Kort, Y.A.W.; Poels, K. The Game Experience Questionnaire; Technische Universiteit Eindhoven: Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ouariachi, T.; Olvera-Lobo, M.D.; Gutiérrez-Pérez, J. Analyzing climate change communication through online games: Development and application of validated criteria. Sci. Commun. 2017, 39, 10–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglino, O.; Di Ferdinando, A.; Di Fuccio, R.; Rega, A.; Ricci, C. Bridging Digital and Physical Educational Games Using RFID/NFC Technologies. J. E-Learn. Knowl. Soc. 2014, 3, 83–104. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Huang, C.I.; Wang, H.C.; Yu, L.F. Enriching Physical-Virtual Interaction in AR Gaming by Tracking Identical Real Objects. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.17399v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czok, V.; Krug, M.; Müller, S.; Huwer, J.; Weitzel, H. Learning Effects of Augmented Reality and Game-Based Learning for Science Teaching in Higher Education in the Context of Education for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baykal, G.E.; Torgersson, O.; Ruijten-Dodoiu, P.; Eriksson, E. Teaching Design of Technologies for Collaborative Interaction in Physical-Digital Environments. Interact. Des. Archit. 2023, 58, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manalac, A. Wasteworld. Available online: https://www.virtualrealitymarketing.com/case-studies/wasteworld/ (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Lin, H.C.K.; Lin, Y.H.; Wang, T.H.; Su, L.K.; Huang, Y.M. Effects of Incorporating AR into a Board Game on Learning Outcomes and Emotions in Health Education. Electronics 2020, 9, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, A.M.; Romão, T. Encouraging Chemistry Learning Through an Augmented Reality Magic Game. In Proceedings of the 18th IFIP Conference on Human-Computer Interaction (INTERACT), Bari, Italy, 30 August–3 September 2021; pp. 12–21. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).