Abstract

As encrypted traffic analysis becomes increasingly vital for network security, the conventional reliance on centralized classification faces growing challenges due to data privacy regulations and data silos across heterogeneous nodes. Federated learning (FL) emerges as a solution by training models locally and sharing only parameter updates, thus preserving privacy. However, its performance is significantly degraded by data heterogeneity (i.e., non-IID data) among participants. To address this critical challenge, this paper proposes a Federated Learning framework based on Deep Mutual Learning (FLDML). In this method, clients first train local models on their private traffic data and then upload them to a server. There, they engage in deep mutual learning through co-training on a shared public dataset to enhance robustness and mitigate data heterogeneity. Subsequently, a global classifier is generated by averaging the model parameters. When evaluated on the ISCX VPN-NonVPN 2016 dataset, FLDML demonstrates significantly superior performance in handling non-IID traffic data compared to classical FL algorithms. This study concludes that the proposed framework not only effectively mitigates data heterogeneity in federated scenarios but also provides a scalable and improved solution for distributed network traffic classification.

1. Introduction

With the widespread use of the internet and the growing sophistication of cyberattacks [1], cybersecurity has become a critical concern for businesses and individuals alike [2,3]. Therefore, as a vital technique, network traffic classification enables the detection of threats, efficient resource allocation, and informed network planning [4]. Meanwhile, the rapid deployment of Internet of Things (IoT) devices has led to increasingly heterogeneous network traffic [5]. For instance, traffic from IoT sensors, video streaming platforms, and cloud services varies significantly in data formats, statistical distributions, and quality of service (QoS) requirements [6].

Although conventional network traffic classification methods, such as port-based approaches, deep packet inspection (DPI) [7], and traditional machine learning techniques [8], perform well in specific scenarios, they struggle with new traffic types, encrypted flows, and non-independent and identically distributed (non-IID) data. These methods rely heavily on manual feature engineering, which demands domain expertise for constructing effective representations from increasingly complex data. While deep learning demonstrates strong potential in traffic classification, its reliance on centrally collected large datasets introduces privacy concerns and increases the risk of data leakage during training [9].

In practical network environments, such as cross-organizational security operation collaborations, multi-tenant cloud infrastructures, or joint analysis between internet service providers and content providers, the traffic data held by different participants often cannot be centralized due to privacy regulations, commercial confidentiality, or administrative boundaries. Traditional centralized classification methods face compliance risks and data silos in such scenarios. Federated learning (FL) [10] provides a collaborative paradigm of “moving models, not data,” in which participants train models locally and only exchange model updates, thereby offering a feasible approach for distributed network traffic classification that balances privacy preservation with collaborative learning capabilities [11,12].

Thus, federated learning has emerged as a promising decentralized machine learning paradigm. It enables multiple participants to collaboratively train a shared model without exchanging raw data. This approach not only preserves data privacy but also addresses the challenges posed by inherently distributed data sources. Owing to these advantages, federated learning has become a pivotal tool for network traffic classification research.

A predominant challenge in conventional federated learning stems from non-independent and identically distributed (non-IID) data across clients. This means that the local datasets held by different clients exhibit distinct statistical properties [13,14]. This data heterogeneity leads local models to overfit their respective client-specific data patterns, thereby degrading their overall performance. The issue is particularly acute in network traffic classification, where the core objective is to build models capable of generalizing to the global data distribution. Overfitting to localized client patterns directly undermines this goal, leading to poor performance on unseen traffic.

To address the critical challenges of data heterogeneity (non-IID data) and privacy preservation in federated learning, this paper introduces a novel federated network traffic classification framework based on deep mutual learning, which we term the FLDML framework. The proposed FLDML framework is designed to effectively mitigate data heterogeneity, enhance inter-client collaboration, and maintain strict data privacy—all within a unified federated learning process.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- Mitigating Data Heterogeneity: We introduce a deep mutual learning mechanism to mitigate the performance degradation of conventional federated learning under non-IID data. This mechanism fosters knowledge exchange among clients, enhancing model generalization across diverse distributions by preventing overfitting to localized patterns.

- The FLDML Framework: We propose the FLDML framework. Its core innovation is a server-side mutual learning phase, where client models are co-trained on a public dataset to assimilate a more robust and generalized representation, complementing their local training on private data.

- A Lightweight Local Model: We design a lightweight local model architecture that integrates a 1D-CNN with Batch Normalization (BN), termed BN-CNN. This design is tailored for efficient feature extraction from preprocessed traffic sequences. Experiments on the ISCX VPN-NonVPN 2016 dataset confirm that BN-CNN achieves superior accuracy and F1-score over traditional baselines.

- Comprehensive Validation: Through extensive comparative experiments on the ISCX dataset, we demonstrate that FLDML achieves higher traffic classification accuracy than both a centralized BN-CNN baseline and classical federated algorithms like FedAvg, effectively balancing performance with the privacy benefits of decentralized training.

2. Related Work

This section reviews the background and theoretical foundations of federated learning-based traffic classification, structured around three key perspectives. First, we analyze the limitations of conventional methods, which are constrained by data silos and privacy issues inherent in centralized architectures. Second, we discuss how federated learning addresses these challenges through decentralized, privacy-preserving collaboration. Third, we examine the synergistic benefits of integrating deep mutual learning with federated learning to mitigate data heterogeneity and enhance model generalization. Collectively, this review clarifies the motivation and theoretical underpinnings of our proposed approach.

2.1. Conventional Network Traffic Classification

Network traffic classification is crucial for network security and management [15,16]. Traditional methods, including port-based and payload-based techniques [17,18], have suffered from declining accuracy and escalating computational costs due to the proliferation of encrypted protocols and evolving network technologies. This has spurred a shift toward machine learning. However, conventional algorithms such as Support Vector Machines (SVMs) [19], Naive Bayes [20], and K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) [21] are limited by their reliance on manual feature engineering and their inability to capture complex, high-dimensional patterns.

Deep learning, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [22], offers automated feature extraction and superior pattern recognition. Yet, its effectiveness depends on large-scale, centralized labeled datasets, raising significant privacy and data aggregation concerns.

Federated learning (FL) [23] emerges as a solution by enabling collaborative model training across decentralized nodes without sharing raw data. This paradigm not only preserves data privacy but also alleviates the dependency on centralized data pools, directly addressing key challenges like data heterogeneity and privacy in traffic classification.

2.2. Federated Learning for Network Traffic Classification

Data heterogeneity is a critical challenge in network traffic classification. While most existing studies focus on single-technique approaches, they struggle to simultaneously ensure privacy protection and effectively model heterogeneous data distributions. Conventional centralized deep learning relies on data aggregation, which raises compliance risks due to potential privacy violations. Moreover, confining training to a single node restricts the model’s exposure to the global data distribution, ultimately leading to suboptimal classification performance. Although federated learning [23] offers a promising solution, techniques such as hierarchical clustering and weighted aggregation only partially address data heterogeneity, with inter-model collaboration mechanisms remaining underexplored.

Recent studies have applied federated learning to traffic classification [24]. For instance, Bakopoulou et al. [25] proposed a federated learning-based framework for packet classification, employing Federated Averaging (FedAvg) [26] to aggregate local models. Their experiments on three real-world datasets demonstrated superior performance in classification accuracy, communication efficiency, and computational cost. Similarly, Mun and Lee [27] developed FLIC, a privacy-preserving protocol for classifying emerging traffic types. However, the non-IID (non-Independent and Identically Distributed) distribution of traffic categories across clients causes slow convergence and limited accuracy in federated learning models [28]. To overcome these limitations, this paper introduces a novel approach aimed at enhancing the accuracy of federated traffic classification under heterogeneous (non-IID) data conditions.

2.3. Deep Mutual Learning

Both Deep Mutual Learning (DML) [29] and Knowledge Distillation (KD) [30] represent two prominent paradigms for model enhancement through knowledge transfer, moving beyond conventional single-model training. By facilitating interactions between models, they can achieve objectives such as model compression, improved generalization, and adaptation to heterogeneous data [31]. However, their underlying architectures and operational mechanisms diverge significantly.

KD is characterized by an asymmetric teacher–student framework. A pre-trained, high-performance teacher model unidirectionally transfers knowledge (e.g., via softened outputs or intermediate representations) to guide the training of a typically smaller student model. This paradigm is highly effective for model compression and cross-modal transfer tasks. In contrast, DML operates on a peer-to-peer basis, where multiple student models of similar capacity are trained collaboratively and synchronously. They engage in bidirectional knowledge exchange, learning from each other’s outputs throughout the training process. This symmetrical cooperation makes DML particularly suitable for mitigating data heterogeneity [32], as it fosters a consensus among models without imposing a hierarchical structure.

Notably, DML’s peer-to-peer architecture offers distinct advantages in federated learning scenarios. Specifically, in federated learning with non-IID data, a single teacher model in KD may become biased toward the data distribution of certain clients, thus failing to fairly represent the heterogeneous knowledge across all participants. In contrast, the peer-to-peer mutual learning paradigm enables all client models to collaboratively negotiate and distill a consensus representation through bidirectional knowledge exchange. In federated traffic classification, after initial local training on private data, client models can further refine their knowledge through mutual learning on a shared public dataset. This process allows each model to preserve local data characteristics while assimilating global patterns. Critically, it avoids the limitation inherent in KD where a single, potentially biased teacher model may not adequately represent all clients’ heterogeneous data. Consequently, DML demonstrates greater adaptability and robustness in dynamic, non-IID federated environments compared to the unidirectional knowledge flow of KD.

Capitalizing on this synergy, this paper innovatively integrates DML into the federated learning framework and proposes the FLDML method. FLDML is designed to enhance local model generalization through structured bidirectional interactions. By enabling models to learn collaboratively from public data, it directly compensates for the distributional discrepancies present in their private datasets, thereby addressing the core challenge of data heterogeneity in federated traffic classification.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Overview

Deep learning has advanced end-to-end network traffic classification by reducing both human intervention and false alarm rates [33]. However, increasingly stringent privacy regulations limit data availability for centralized model training. While federated learning (FL) presents a compelling privacy-preserving alternative, its efficacy is severely undermined by performance degradation under non-IID data distributions. This creates a core dilemma: how to simultaneously guarantee strict privacy, maintain model efficiency, and achieve robust generalization in federated traffic classification.

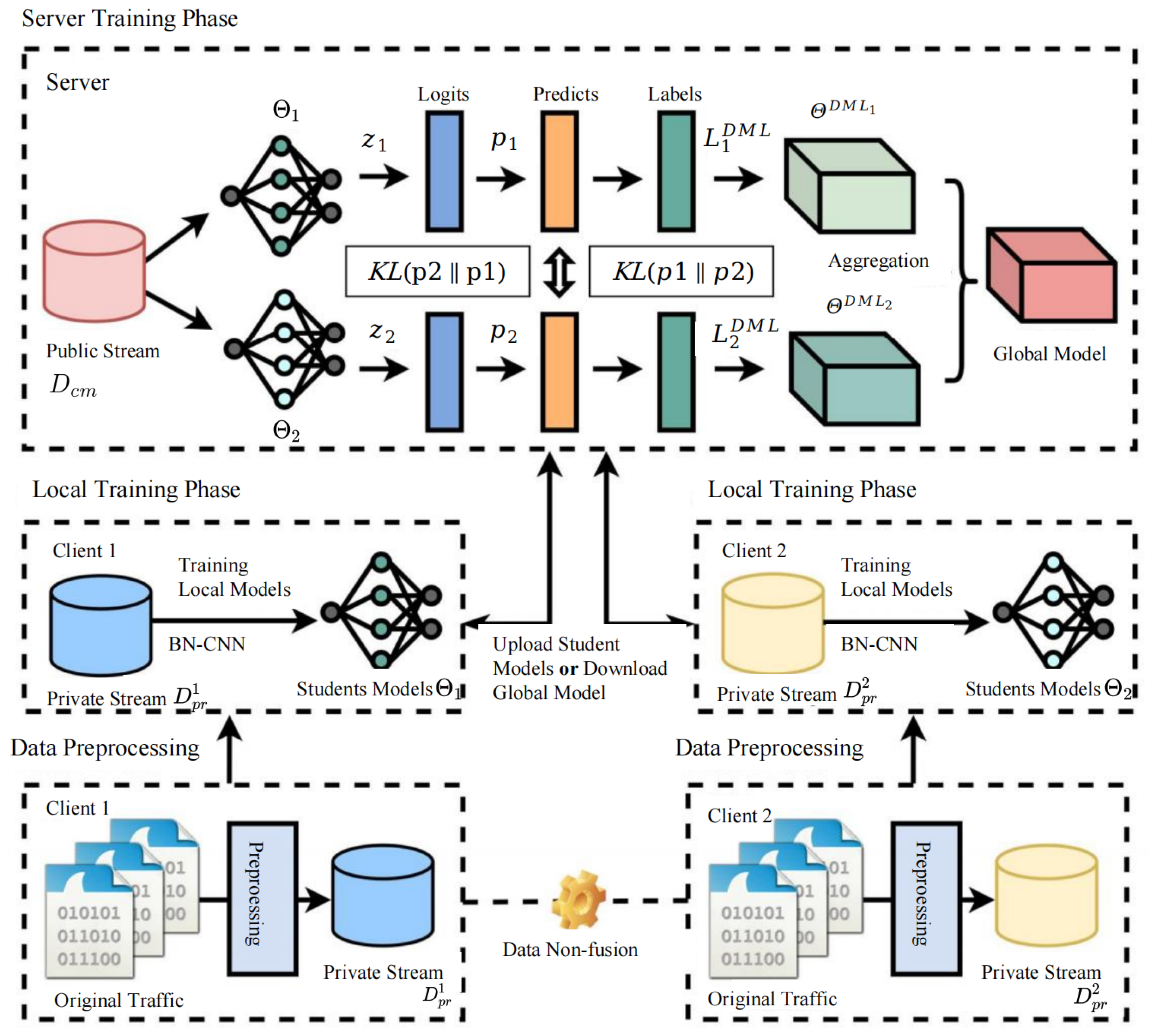

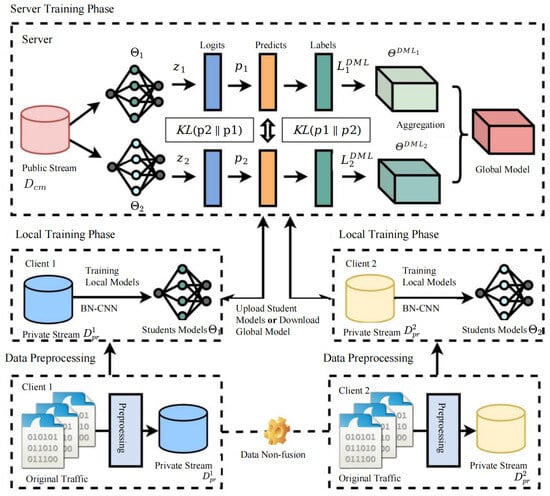

To address the performance degradation caused by non-IID data in federated learning, this paper introduces a novel framework that integrates deep mutual learning, termed the Federated Deep Mutual Learning (FLDML) method. As illustrated in Figure 1, the FLDML framework preserves data privacy by design, requiring no exchange of raw client data. The process comprises three sequential stages: (1) Local Training: Each client trains a local model (student) on its preprocessed private traffic flows. (2) Server-side Mutual Learning: Clients upload their local models to a central server, where they undergo a deep mutual learning process by co-training on a shared public dataset. This bidirectional knowledge exchange enhances model robustness and mitigates data heterogeneity. (3) Model Aggregation: The server performs weighted averaging on the mutually refined models to produce an updated global model.

Figure 1.

A framework for federated distributed network traffic classification based on deep mutual learning.

3.2. Datasets

Addressing the critical challenge of data preprocessing in heterogeneous federated network traffic classification, our experiments are conducted on the ISCX VPN-NonVPN 2016 encrypted dataset [34], which contains 28 GB of real-world traffic collected by the University of New Brunswick’s Cybersecurity Laboratory using Tcpdump V4.9 and Wireshark V2.2. As shown in Table 1, the dataset contains 12 distinct service types (6 conventional and 6 VPN-encrypted), is stored in standard pcap/pcapng formats, and possesses an inherently imbalanced distribution. To accommodate encrypted video/audio streams and ensure privacy compliance, we implement comprehensive preprocessing including data segmentation, cleansing, restructuring, and partitioning.

Table 1.

ISCX VPN and Non-VPN traffic service types.

3.3. Client-Side Data Preprocessing

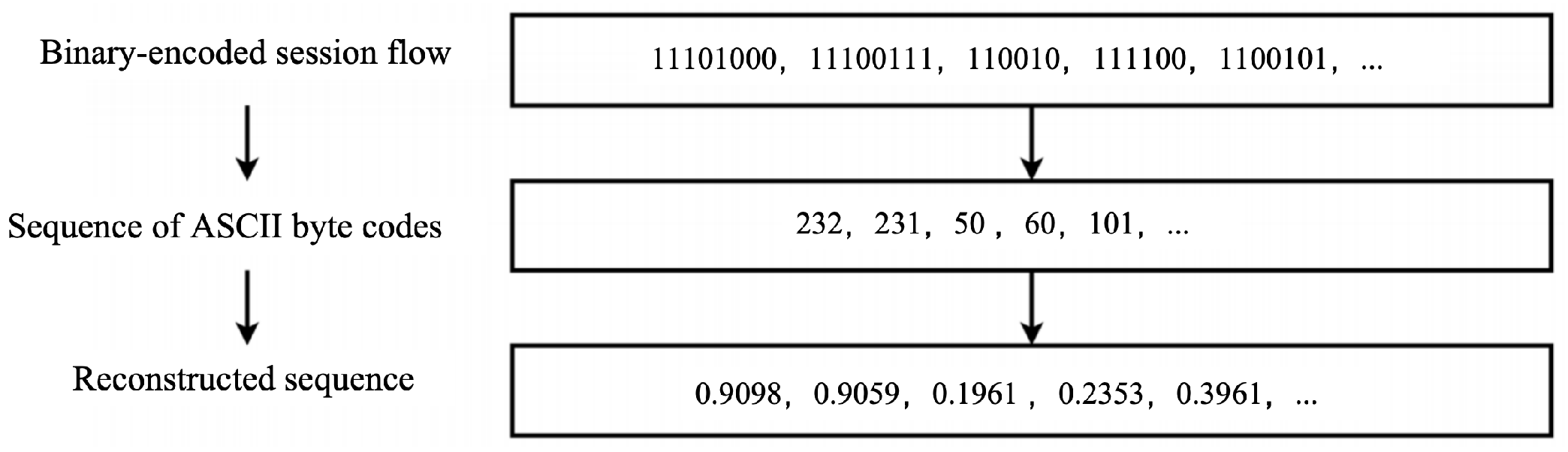

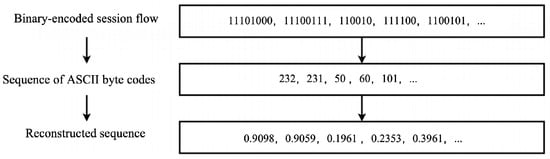

The client-side preprocessing pipeline comprises four distinct stages to transform raw traffic data into standardized session-level inputs. (1) Traffic Splitting: Session-level flows are extracted from pcap/pcapng files through quintuple-based packet aggregation (source/destination IP, ports, protocol) using SplitCap V1.9. (2) Data Cleaning: Flows undergo purification by removing duplicates and anomalies, followed by full anonymization through MAC/IP address zeroing. (3) Feature Restructuring: Each session is encoded into a normalized 784 × 1 vector through ASCII conversion, min-max scaling to [0, 1], and length standardization via truncation/zero-padding as shown in Figure 2. (4) Dataset Partitioning: Processed sequences are organized into training/testing splits stored in NPZ format. This pipeline enables each client K to generate private training streams with and .

Figure 2.

Data reconstruction procedure.

3.4. Client-Side Local Model Training

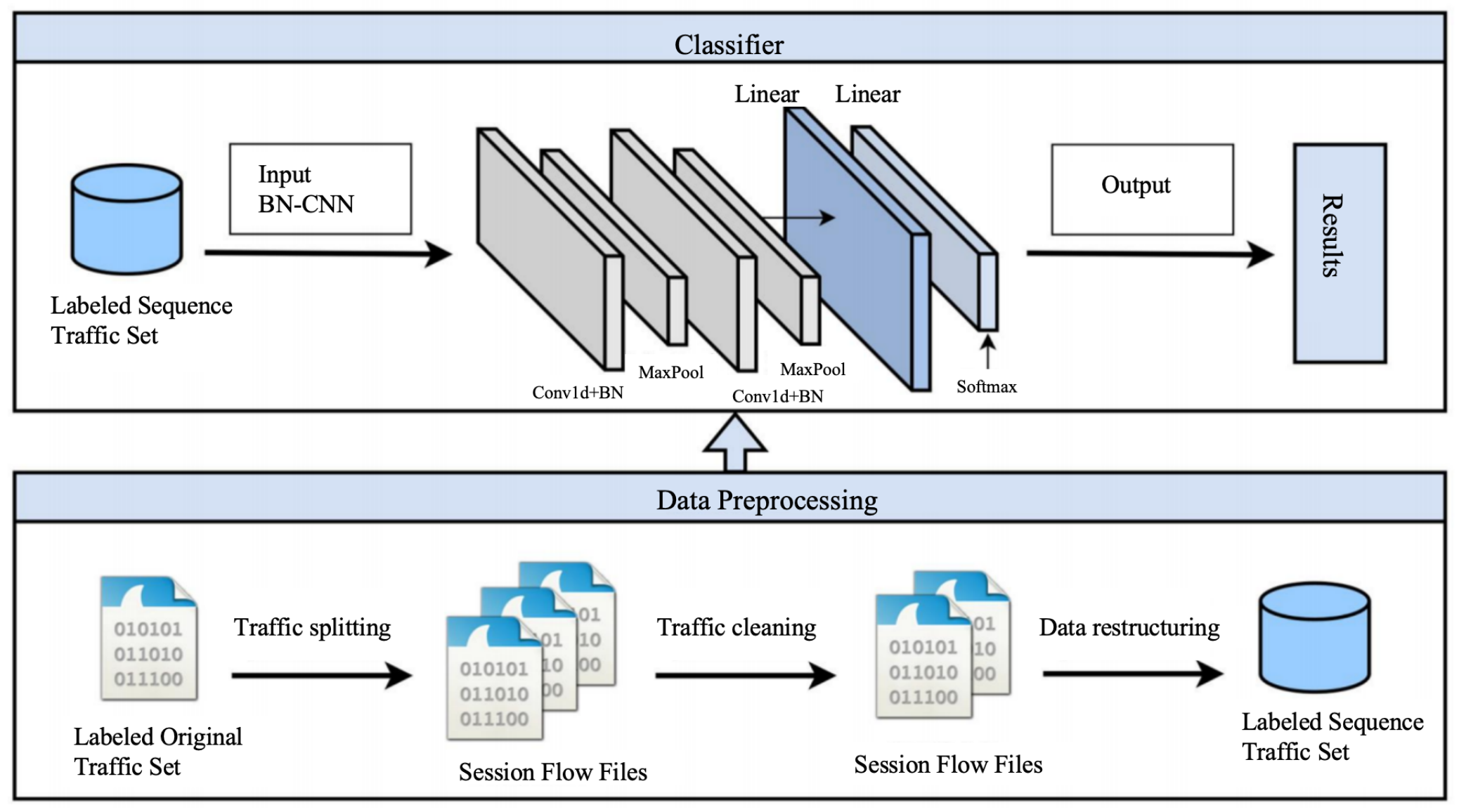

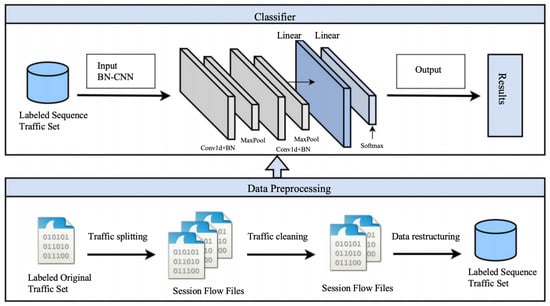

At the t-th communication round, the server randomly selects clients to form set A using , where controls participant fraction. Each client downloads the global model and parameters from the server to initialize its local model with parameters .

As illustrated in Figure 3, each client employs a BN-CNN classifier for local training. Preprocessed traffic data (Section 3.3)—converted to session-level sequences normalized to [0, 1]—is fed into the model. The architecture comprises stacked Conv1D, Batch Normalization (BN), and MaxPooling layers, enabling efficient extraction of temporal features from traffic flows while accelerating convergence and reducing initialization sensitivity. The output layer utilizes Softmax to generate classification probabilities, with the highest value indicating the predicted traffic class.

Figure 3.

Local classification model framework.

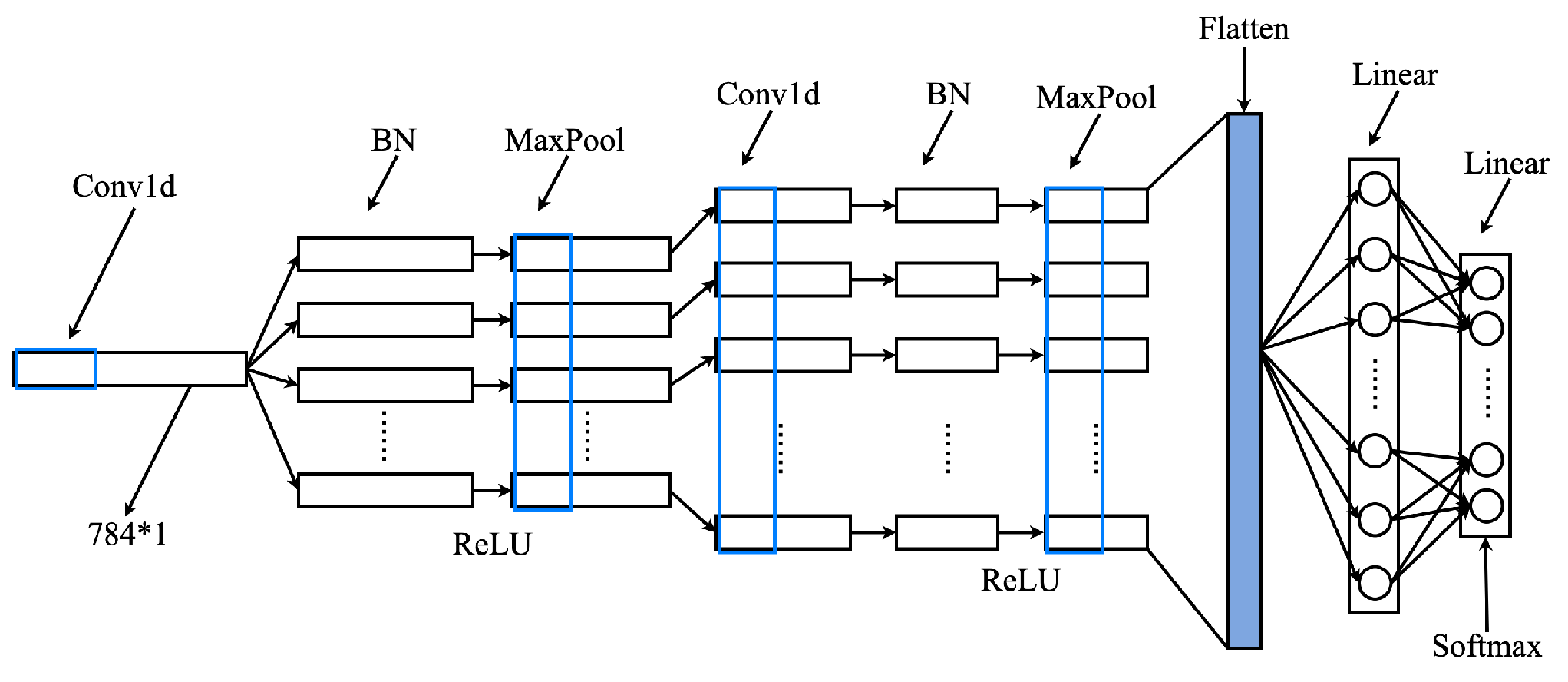

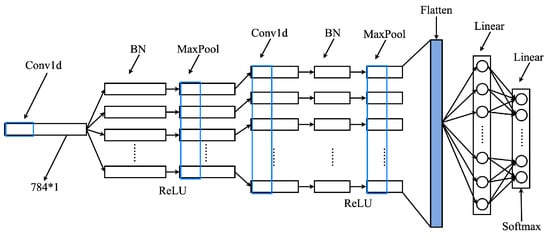

The BN-CNN design (Figure 4, Table 2) incorporates two Conv1D layers (kernel sizes 41 and 31), two BN layers, ReLU activations, MaxPooling (window size 3), and two fully connected layers. This configuration leverages 1D convolution’s translation invariance to recognize shifted temporal patterns, multi-scale kernels for hierarchical feature extraction, and BN for regularization—effectively stabilizing gradients, mitigating overfitting, and enhancing test-set generalization [35,36].

Figure 4.

BN-CNN model structure.

Table 2.

Network structure and parameter setting of BN-CNN model.

The BN-CNN model structure and parameter settings are as shown in Table 2. Client k iteratively trains the local model using the private stream for E epochs to obtain an updated student model and model parameters . The probability of class m for sample given by the student model is calculated as , which can be expressed by Formula (1).

Here, is the logistic output of the model . For a multi-class classification task on network traffic, the objective function for training the local model is defined as the cross-entropy error between the predicted values and the correct labels. The cross-entropy loss can be expressed by Formula (2).

Here, the function can be defined by Formula (3).

3.5. Server-Side Student Models Learn from Each Other and Model Average Aggregation Stages

Each client k uploads the student model and its model parameters to the server. On the server, the student model undergoes mutual learning using a small public dataset , where . Then, after iterative training for F rounds, we obtain the updated model and model parameters . The cross-entropy loss of the student model on the public dataset can be expressed by Formula (4).

Additionally, another student model and its posterior probability are used to provide training experience for . To quantify the difference between the predictions and of the two student models, the Kullback–Leibler divergence is used to measure the distance between the distributions and , which is expressed in Formula (5).

Through deep mutual learning, each heterogeneous student network learns to correctly predict the true labels of the public data stream (supervised loss ), as well as to match the probability estimates of its peer ( divergence loss), thereby improving the performance of the student models.

The overall loss functions for models and at communication round t are and respectively, which are expressed in Formulas (6) and (7).

Here, , , and are hyperparameters that control the proportion of knowledge coming from the data or from other models. Therefore, for client k’s model during the t-th communication process, the overall loss function can be expressed by Formula (8).

Here,

Finally, the model parameters from multiple models are averaged to obtain the local model parameters at the end of the t-th communication round, which can be expressed by Formula (9).

Repeat the steps described for the t-th communication round until the local model parameters converge, at which point the network traffic classification task based on the FLDML method is completed.

3.6. The FLDML Algorithm

Algorithm 1 will detail the three learning phases of the proposed FLDML algorithm. Steps 1–3 of the data preprocessing phase (Section 3.3): Each client obtains their local private training stream , where , through four steps: data partitioning, data cleaning, data restructuring, and data splitting.

| Algorithm 1 FLDML Algorithm |

| Require: K, Number of clients of the network operator; B, Small batch size; E, Client model training rounds; F, Students model rounds of learning from each other; , Learning rate; ,, Private stream, public stream Data preprocessing: for each client k = 1, 2, …, K do end for Server-side training: for each epoch t = 1, 2, …, T do for each client in paralled do end for for each client , do for each epoch do end for end for end for Client local training: for each local epoch from 1 to E do for each do end for end for return |

Steps 1–14 of the server training phase: During the t th communication round, the server first transmits the local model parameters to a randomly selected set of clients A for local model training (LocalUpdate). Then, the server receives the student models from the clients and uses them for mutual learning (DMLUpdate) on the public stream . The total loss for a client can be represented by Formula (8). Finally, an average aggregation is used to compute the local model parameters , where the local model is the BN-CNN model described in Section 3.4.

Steps 1–7 of the client local training phase, corresponding to Step 6 of the server training phase: Within a single epoch, the local model is trained on batches of size b samples and iteratively trained E times to obtain updated student model parameters . These model parameters are then uploaded to the server. The supervised loss function for the local model is defined in Formula (2).

4. Experimental Results and Discussion

4.1. Experimental Settings

Federated Averaging (FedAvg) is the most classic and widely used aggregation algorithm in federated learning, renowned for its simplicity and efficiency. Consequently, it serves as a standard baseline for comparison across FL studies. To validate the performance improvement of FLDML under non-IID data conditions, we select FedAvg as the primary baseline, using identical communication and training settings.

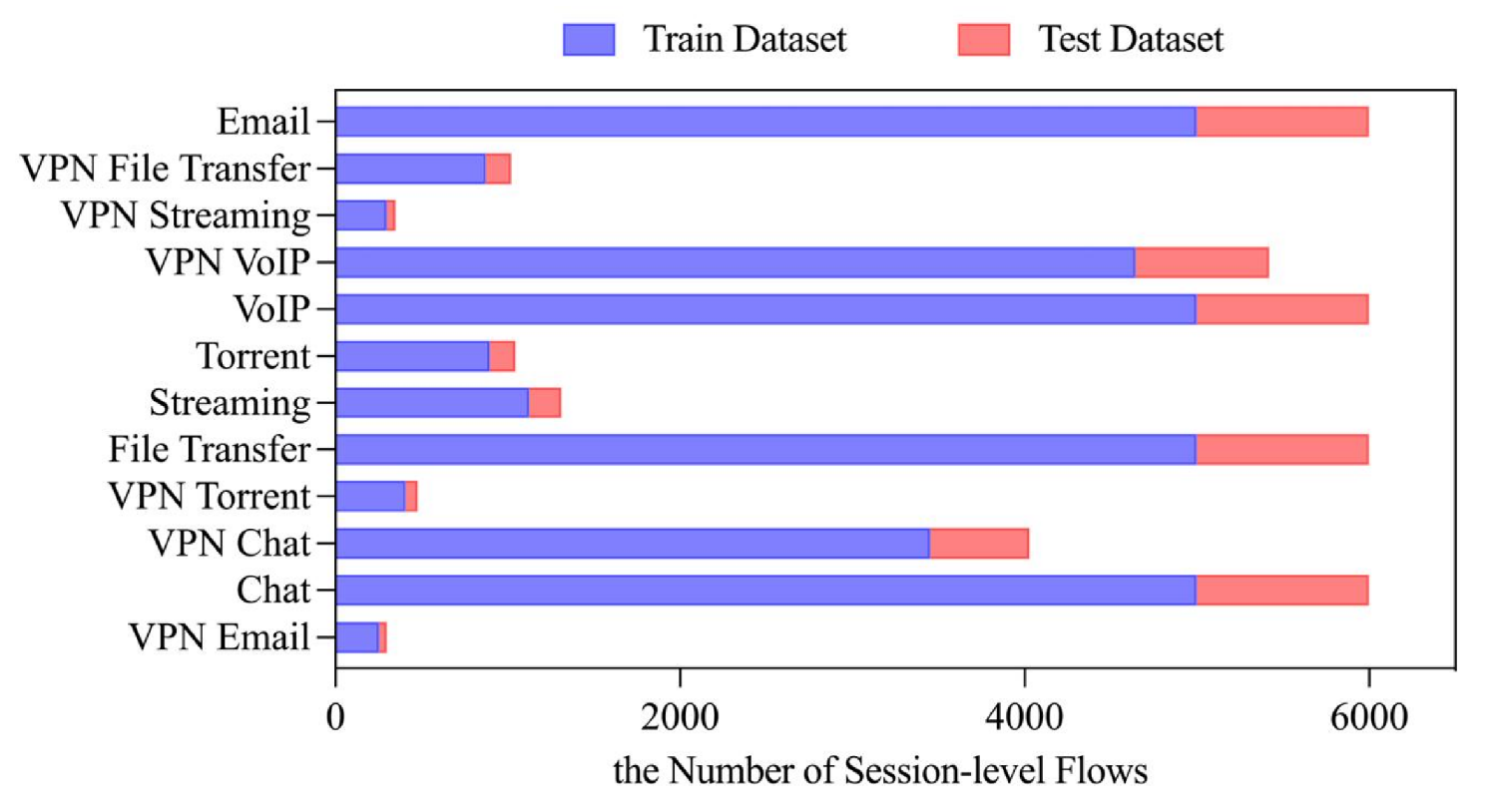

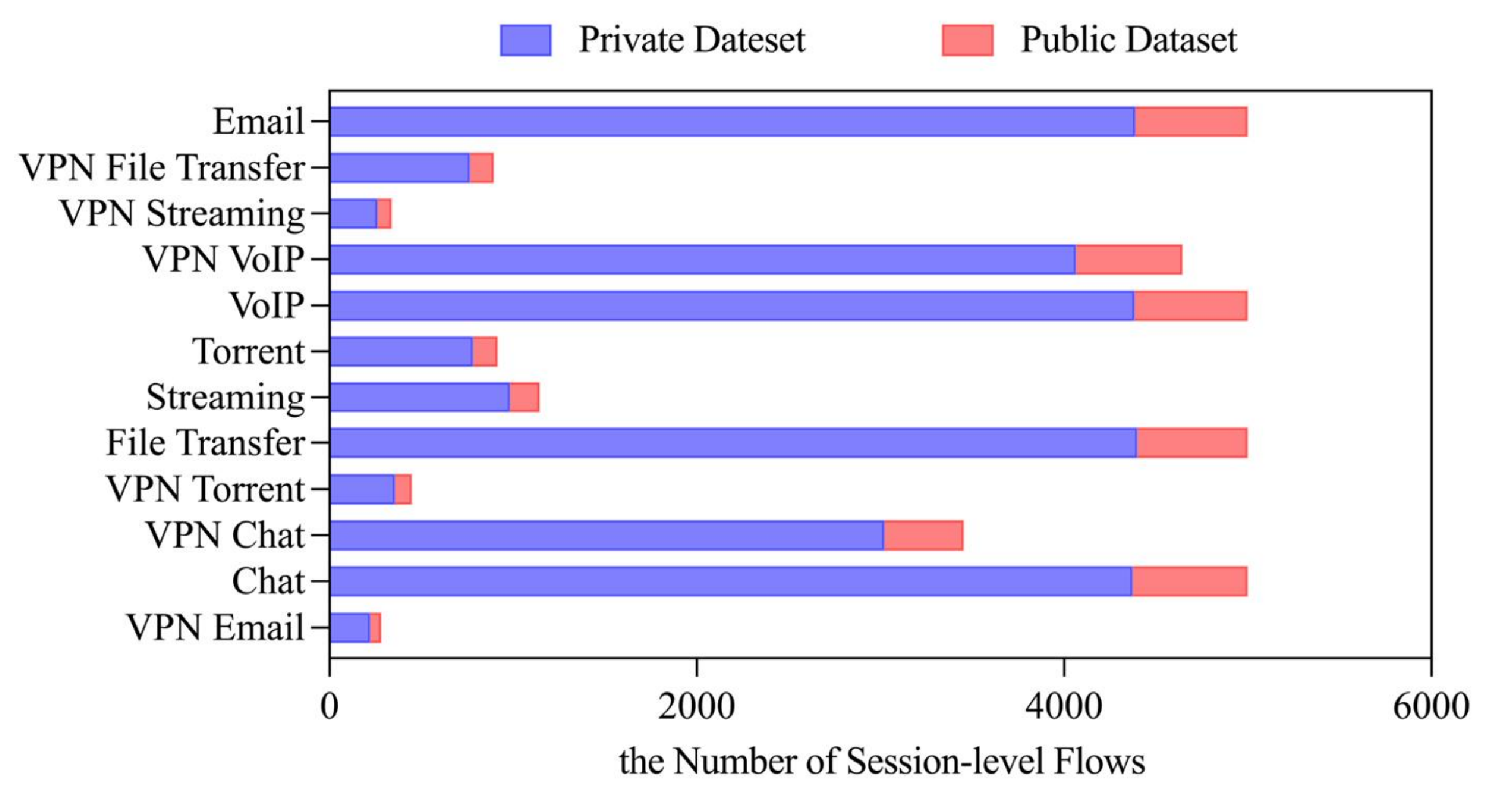

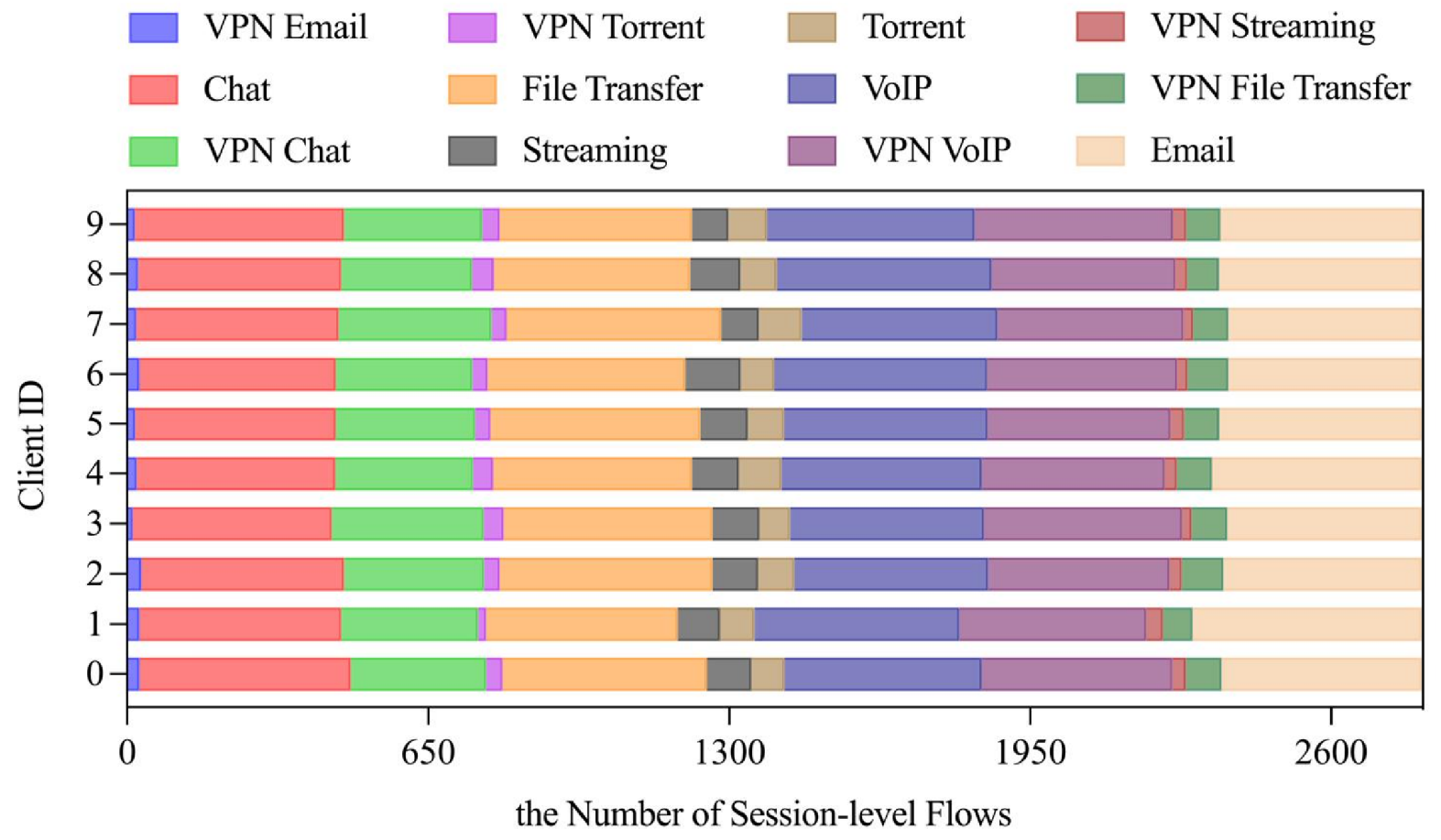

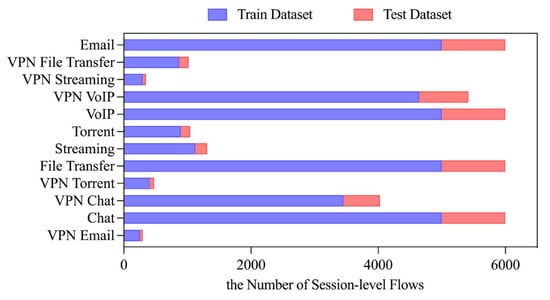

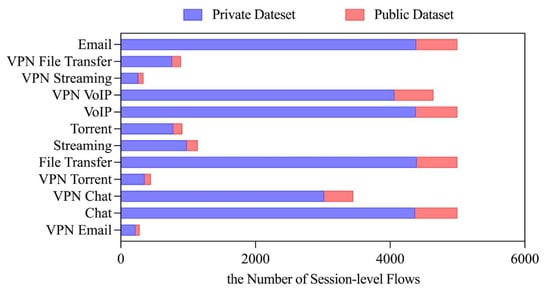

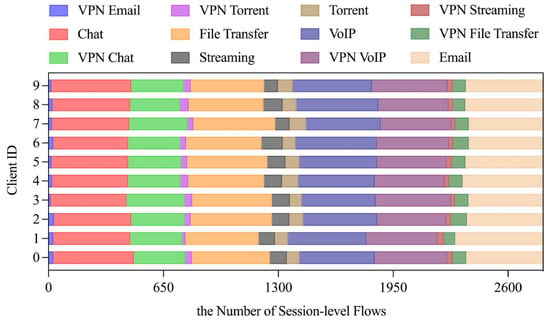

We evaluated our approach in the ISCX VPN-NonVPN 2016 dataset following the preprocessing methodology described in Section 3.3. After preprocessing, the dataset contains approximately 1.5 million session samples covering 12 classes (6 conventional and 6 VPN-encrypted traffic types), which exhibit a significantly imbalanced class distribution as shown in Figure 5. The resulting sample distribution after preprocessing is further illustrated in Figure 5. Figure 6 demonstrates the partition ratio between the public dataset and the private datasets across clients in the FLDML framework.

Figure 5.

Preprocessed sample distribution across 12 traffic classes in the ISCX VPN-NonVPN 2016 dataset.

Figure 6.

Distribution of public dataset and private datasets across 10 clients (private-to-public ratio = 7:1).

For standalone BN-CNN classification, we employed a 6:1 train-test split with a batch size of 128, cross-entropy loss [37], and an SGD optimizer [38] at a learning rate of 0.01.

For the FLDML framework, we extended this configuration with client–server data partitioning (7:1 private-to-public ratio, Figure 6) using batch size 28. We set the number of clients to 10 () to simulate distributed participants with heterogeneous network traffic characteristics (e.g., different service types, temporal patterns, and traffic volumes), such as different enterprises, branch offices, or user groups. The BN-CNN architecture (Table 2) served as the local model across 10 clients (), with participant fraction . Training executed for local and federated rounds, optimized by SGD (lr = 0.01) with combined cross-entropy and KL-divergence objectives.

4.2. Experimental Evaluation

To comprehensively assess classification performance under class imbalance, we employ accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score as evaluation metrics. These metrics are derived from the confusion matrix (Table 3) and formally defined as follows:

Table 3.

Confusion matrix.

All metrics range between [0, 1], with higher values indicating better performance. Accuracy measures overall correctness, precision reflects positive prediction fidelity, recall quantifies positive class coverage, and F1-score represents their harmonic mean.

4.3. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.3.1. Evaluation of the Local Model

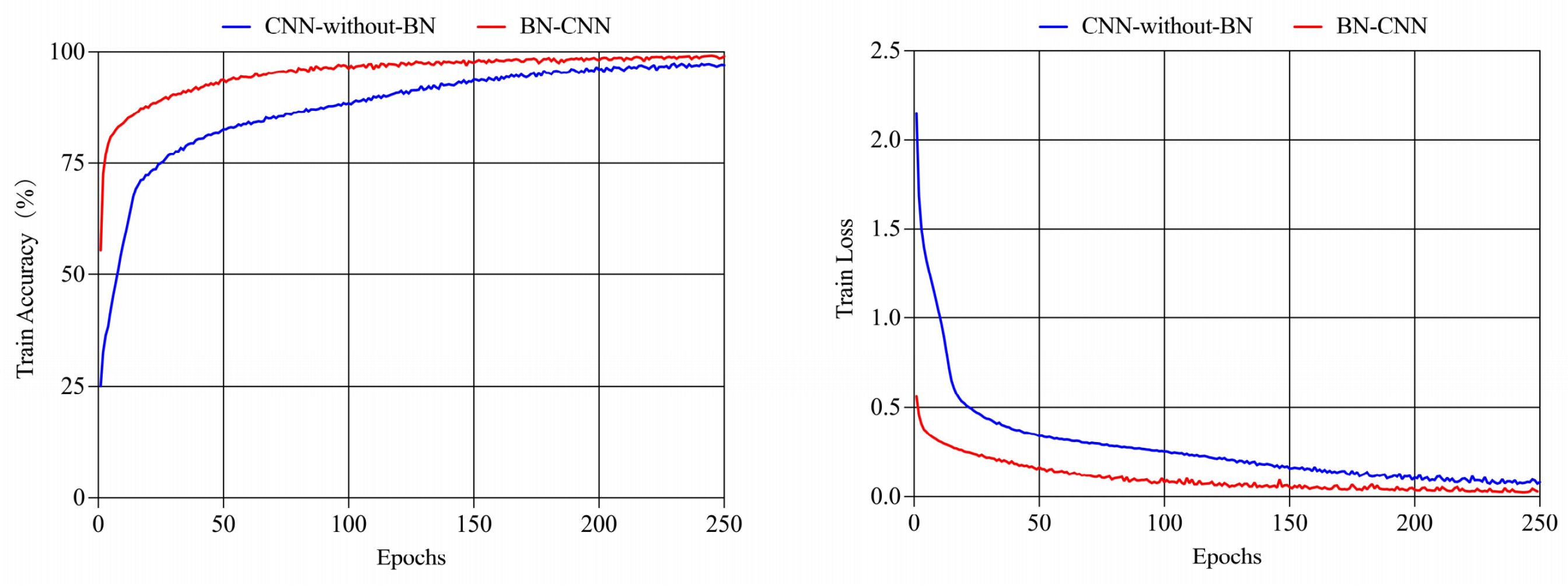

We evaluated the BN-CNN model on the ISCX VPN-NonVPN 2016 encrypted traffic dataset through comprehensive comparisons with C4.5, KNN, 1D-CNN, and CNN-LSTM baselines. The validation focused on two key aspects: BN layer efficacy and comparative performance.

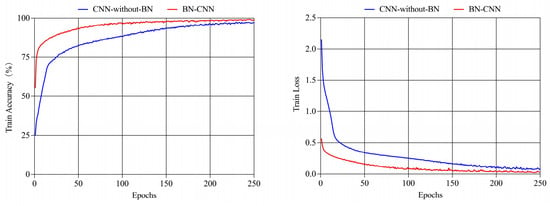

BN Layer Impact. Our ablation study compared BN-CNN against an architecturally identical CNN-without-BN. Figure 7 demonstrates BN-CNN’s accelerated convergence and marginally superior final accuracy. Quantitative results (Table 4) confirm consistent improvements: +0.7% accuracy, +0.7% precision, +0.5% recall, and +0.8% F1-score, validating BN’s role in enhancing temporal feature extraction and model stability.

Figure 7.

Changes in training accuracy and loss values across different models.

Table 4.

Classificationperformance of CNN-without-BN vs. BN-CNN.

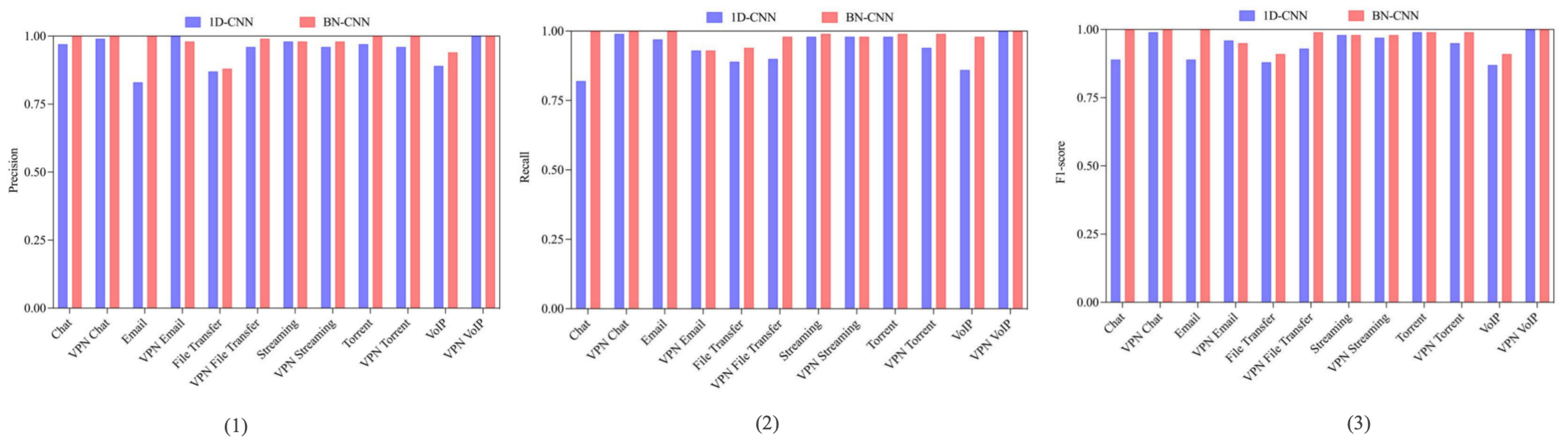

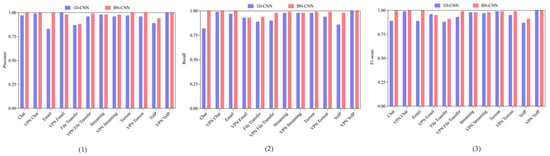

Comparative Performance. Against the 1D-CNN baseline [39] under identical input configurations (session-level 784 × 1 sequences), BN-CNN achieved notable gains (Figure 8): Email (17%) and VoIP (5.1%) precision improvements; Chat (18%) and VoIP (12.2%) recall enhancements; and superior F1-scores for Chat (+11.2%) and Email (+11%). Extended benchmarking (Table 5) shows BN-CNN outperforming machine learning (C4.5, KNN) and deep learning alternatives (DP-CNN, CNN-LSTM), with particular advantages over DP-CNN (+1.7% accuracy) and CNN-LSTM (+3.8% accuracy). These results substantiate our preprocessing pipeline’s efficacy for temporal traffic characterization.

Figure 8.

Comparison across different models. (1) Precision comparison across different models. (2) Recall comparison across different models. (3) F1 comparison across different models.

Table 5.

Comparison experimental results of BN-CNN with other methods.

4.3.2. Evaluation of FLDML

We evaluate the proposed FLDML approach under both IID and non-IID federated learning scenarios to validate its effectiveness in network traffic classification.

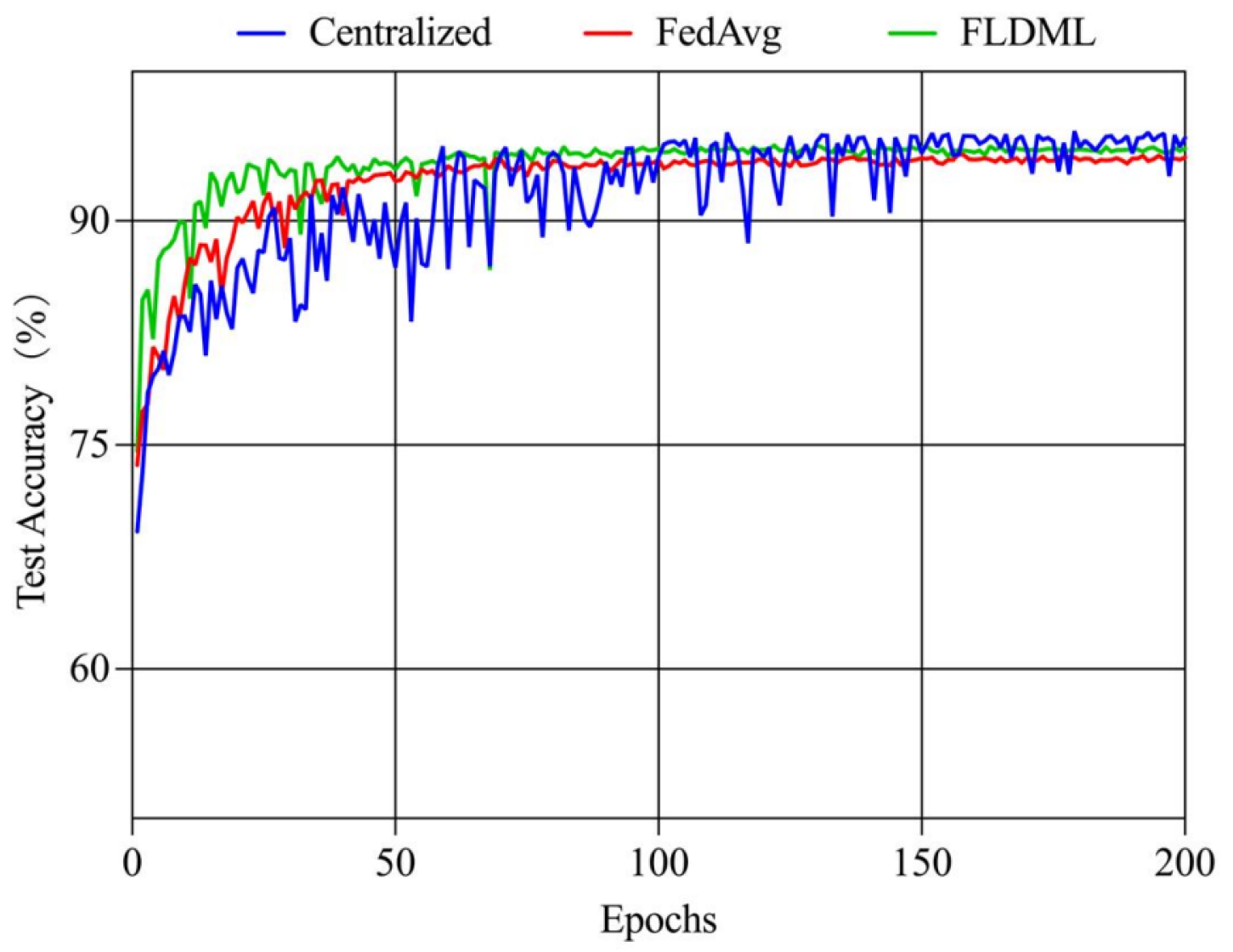

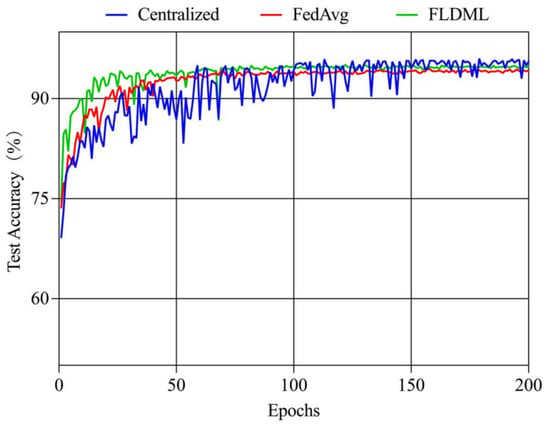

IID Scenario. Under IID settings, private data samples were randomly and uniformly distributed across 10 clients (Figure 9). Comparative experiments against centralized training and FedAvg demonstrate FLDML’s competitive performance. As shown in Figure 10, FLDML achieves faster convergence during early training stages and comparable final accuracy to the centralized approach while outperforming FedAvg. Quantitative results (Table 6) confirm FLDML’s marginal performance gap versus centralized training (−1% accuracy, −1.4% precision) while surpassing FedAvg across all metrics (+0.4–0.5%). This demonstrates FLDML’s ability to maintain model performance while providing enhanced data privacy.

Figure 9.

Visualization of sample data statistics in clients under IID scenario.

Figure 10.

Changes in test accuracy over training rounds for different methods.

Table 6.

Comparison of classification performance across different methods.

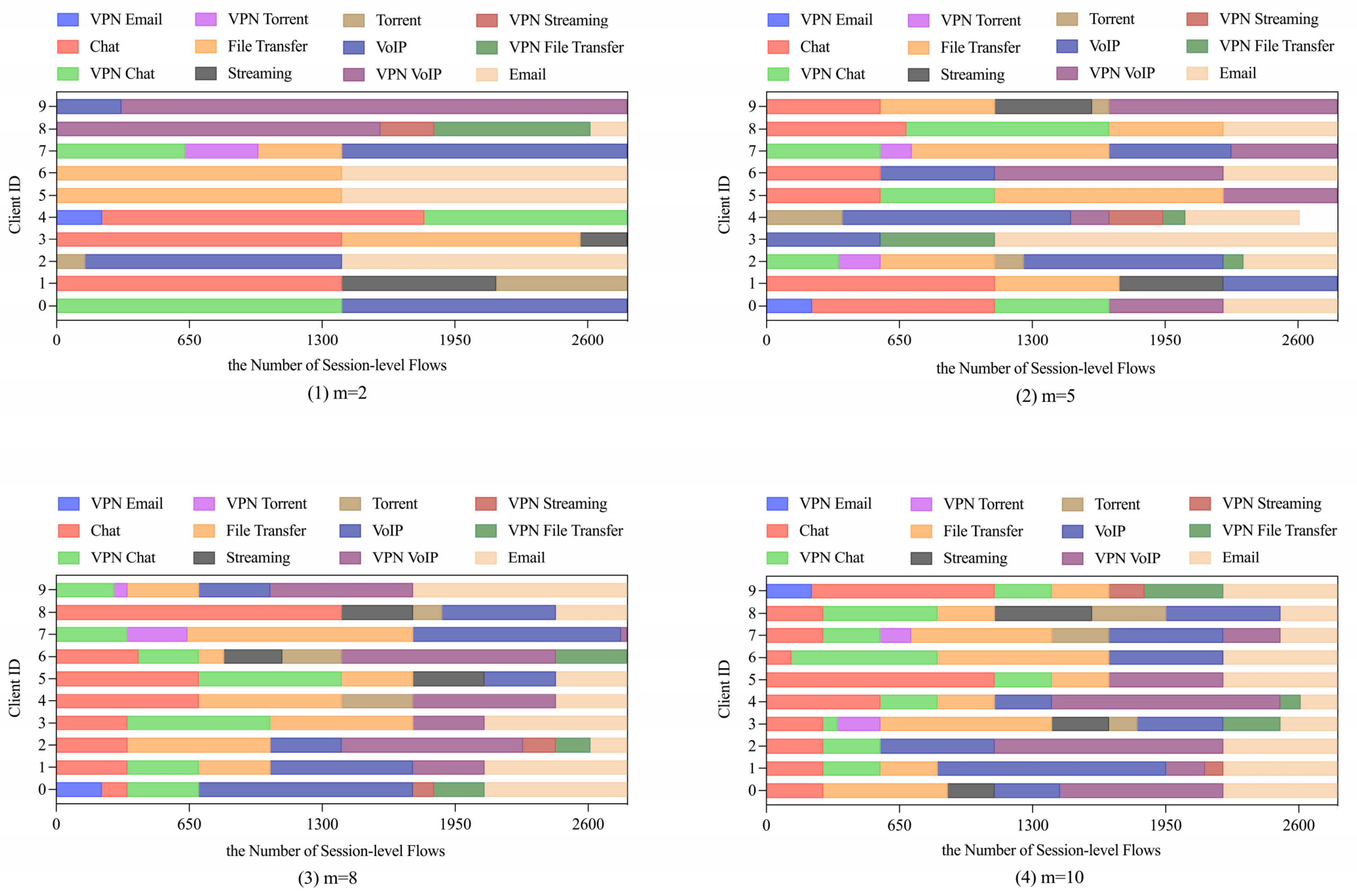

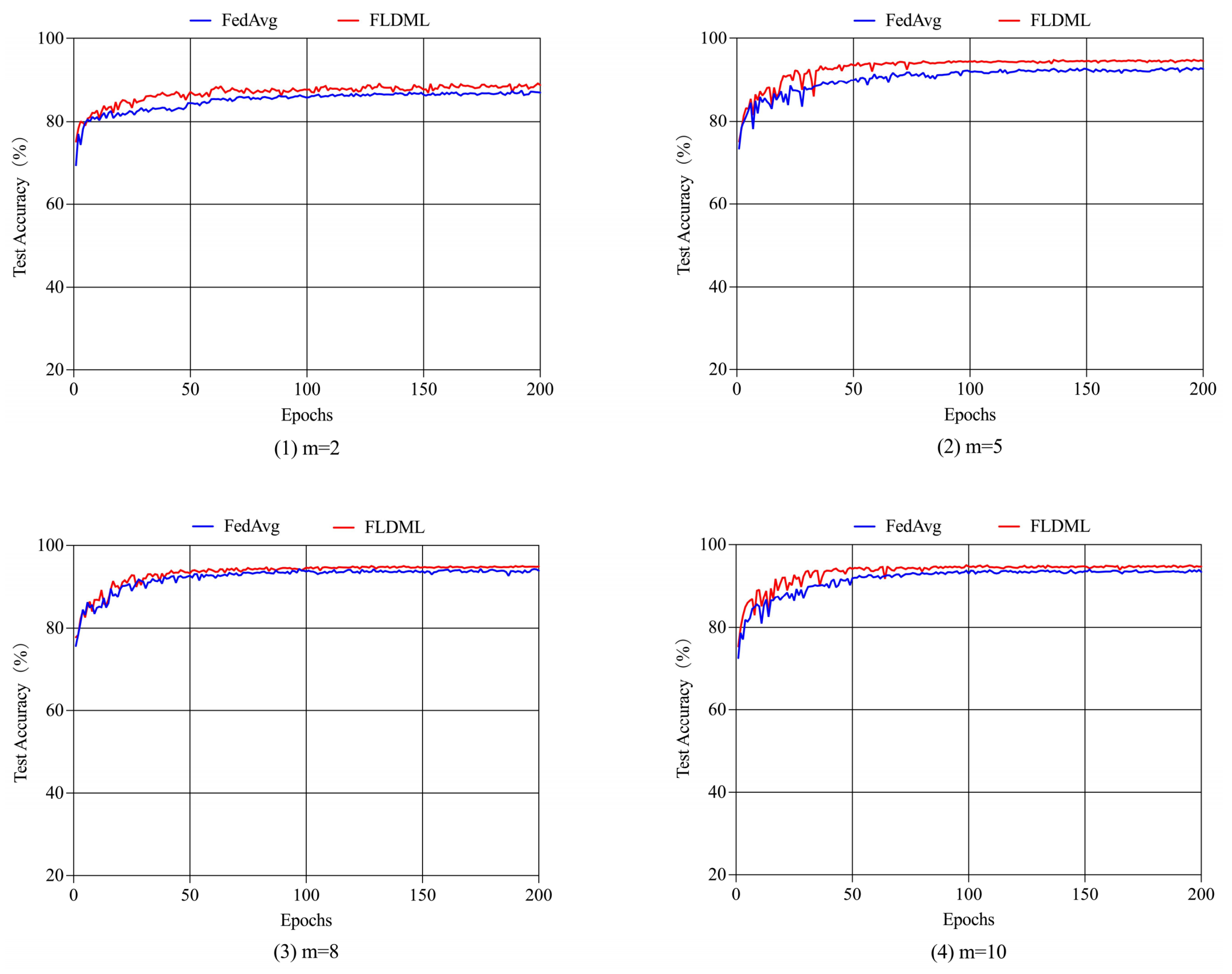

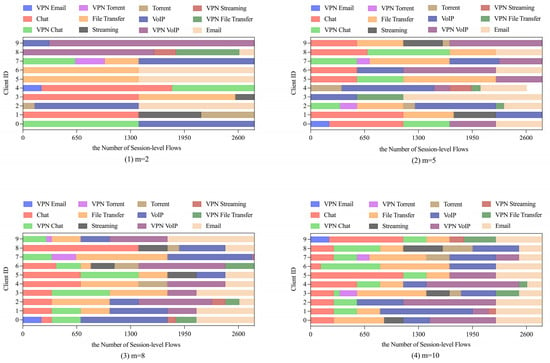

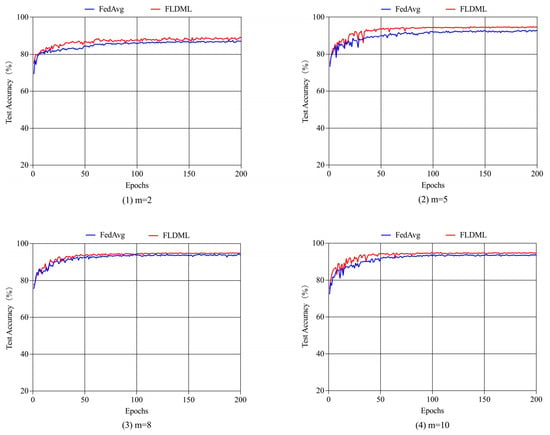

Non-IID Scenario. We construct four non-IID scenarios through sorted partitioning, creating data distributions with m = 2, 5, 8, 10 label classes per client (Figure 11). FLDML consistently outperforms FedAvg across all heterogeneity settings (Table 7), with particularly notable gains under extreme heterogeneity (m = 2: +1.9% precision, +2.3% recall). Convergence analysis (Figure 12) reveals FLDML’s stable superiority in final accuracy across all non-IID configurations. The integration of deep mutual learning enables knowledge transfer through soft labels, effectively regulating student model outputs and enhancing aggregation effectiveness in heterogeneous environments.

Figure 11.

Visualization of sample data statistics in clients under non-IID scenario.

Table 7.

Comparison of classification performance across different methods under various non-IID scenarios.

Figure 12.

Trends in test accuracy over communication rounds for different methods under various non-IID scenarios.

The mutual learning phase on the public dataset serves as an effective regularizer, compelling each client model to distill and align generalized feature representations that transcend their locally skewed data distributions. This process not only mitigates overfitting to client-specific patterns but also enhances the semantic consistency across models, thereby improving the stability and generalization capability of the aggregated global model, especially under high heterogeneity.

5. Conclusions

This paper proposes FLDML, a federated learning method incorporating deep mutual learning to address non-IID data challenges in network traffic classification. Experimental results in the ISCX VPN-NonVPN 2016 datasets demonstrate its superiority over conventional federated approaches.

Future work will focus on the following promising directions: (1) enhancing the framework’s robustness under more realistic and dynamic federated conditions, including client drop-out, network latency, and adversarial presence; (2) investigating adaptive or meta-learning strategies to automatically tune the hyperparameters that balance the local, mutual, and consensus loss components; and (3) extending FLDML to semi-supervised or unsupervised federated learning scenarios, aimed at handling unknown or emerging traffic types without fully labeled data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W. and H.X.; methodology, H.X.; software, Y.H.; validation, Y.W., H.X. and Y.H.; formal analysis, Y.H.; investigation, Y.H.; resources, H.X.; data curation, H.X.; writing—original draft preparation, H.X.; writing—review and editing, H.X.; visualization, Y.H.; supervision, Y.W.; project administration, H.X.; funding acquisition, Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (U21A20463) and Science and Technology Project of Guangzhou (2024A03J0403).

Data Availability Statement

The dataset analyzed in this study is the publicly available ISCX VPN-Non VPN 2016 dataset. It can be accessed from the University of New Brunswick’s website at: https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/vpn.html (accessed on 11 December 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Stojmenovic, I.; Wen, S.; Huang, X.; Luan, H. An overview of Fog computing and its security issues. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2016, 28, 2991–3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Liu, W.; Huang, Z.; Yu, F.R. Task Decomposition and Hierarchical Scheduling for Collaborative Cloud-Edge-End Computing. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2024, 17, 4368–4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Gleerup, T.; Tan, J.; Wang, Y. A security enhanced android unlock scheme based on pinch-to-zoom for smart devices. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2023, 70, 3985–3993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azab, A.; Khasawneh, M.; Alrabaee, S.; Choo, K.K.R.; Sarsour, M. Network traffic classification: Techniques, datasets, and challenges. Digit. Commun. Netw. 2024, 10, 676–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Ma, W.; Han, Q.; Zhou, W.; Zhu, X.; Wen, S.; Xiang, Y. Exploring DeepSeek: A Survey on Advances, Applications, Challenges and Future Directions. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2025, 12, 872–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahaei, H.; Afifi, F.; Asemi, A.; Zaki, F.; Anuar, N.B. The rise of traffic classification in IoT networks: A survey. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2020, 154, 102538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujlow, T.; Carela-Español, V.; Barlet-Ros, P. Independent comparison of popular DPI tools for traffic classification. Comput. Netw. 2015, 76, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Armitage, G. A survey of techniques for internet traffic classification using machine learning. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2008, 10, 56–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Wei, Z.; Luo, J. ICS Anomaly Detection based on Sensor Patterns and Actuator Rules in Spatiotemporal Dependency. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informantics 2024, 20, 10647–10656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wen, Z.; Wu, Z.; Hu, S.; Wang, N.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; He, B. A survey on federated learning systems: Vision, hype and reality for data privacy and protection. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2021, 35, 3347–3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Fu, M.; Ye, Y.; Wang, P. Network traffic classification based on federated semi-supervised learning. J. Syst. Archit. 2024, 149, 103091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, C.; Wang, D.; Wen, S.; Zhang, J.; Nepal, S.; Xiang, Y.; Ren, K. Android HIV: A study of repackaging malware for evading machine-learning detection. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2019, 15, 987–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, S.D.; Wu, D.; Hu, X.; Wang, Y. ARDST: An Adversarial-Resilient Deep Symbolic Tree for Adversarial Learning. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2024, 2024, 2767008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Sun, R.; Xue, M.; Ma, W.; Wen, S.; Nepal, S.; Yang, X. Hardening LLM Fine-Tuning: From Differentially Private Data Selection to Trustworthy Model Quantization. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2025, 20, 7211–7226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, W.; Wei, G.; Yang, L.T. Internet Traffic Classification Using Constrained Clustering. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2014, 25, 2932–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Sun, R.; Xue, M.; Wen, S.; Camtepe, S.; Nepal, S.; Xiang, Y. Leakage-Resilient and Carbon-Neutral Aggregation Featuring the Federated AI-Enabled Critical Infrastructure. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2025, 22, 3661–3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roughan, M.; Sen, S.; Spatscheck, O.; Duffield, N. Class-of-service mapping for QoS: A statistical signature-based approach to IP traffic classification. In Proceedings of the 4th ACM SIGCOMM Conference on Internet Measurement, Taormina Sicily, Italy, 25–27 October 2004; pp. 135–148. [Google Scholar]

- Finsterbusch, M.; Richter, C.; Rocha, E.; Muller, J.A.; Hanssgen, K. A survey of payload-based traffic classification approaches. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2013, 16, 1135–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumano, Y.; Ata, S.; Nakamura, N.; Nakahira, Y.; Oka, I. Towards real-time processing for application identification of encrypted traffic. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Computing, Networking and Communications (ICNC), Honolulu, HI, USA, 3–6 February 2014; pp. 136–140. [Google Scholar]

- Okada, Y.; Ata, S.; Nakamura, N.; Nakahira, Y.; Oka, I. Application identification from encrypted traffic based on characteristic changes by encryption. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Workshop Technical Committee on Communications Quality and Reliability (CQR), Naples, FL, USA, 10–12 May 2011; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Yanai, R.; Langberg, M.; Peleg, D.; Roditty, L. Realtime classification for encrypted traffic. In Proceedings of the Experimental Algorithms: 9th International Symposium, SEA 2010, Ischia Island, Naples, Italy, 20–22 May 2010; Proceedings 9. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 373–385. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Zhu, M.; Zeng, X.; Ye, X.; Sheng, Y. Malware traffic classification using convolutional neural network for representation learning. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Information Networking (ICOIN), Da Nang, Vietnam, 11–13 January 2017; pp. 712–717. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Xie, Y.; Bai, H.; Yu, B.; Li, W.; Gao, Y. A survey on federated learning. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2021, 216, 106775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Liang, Z.; He, M.; Peng, Y.; Xue, H.; Wang, Y. A federated semi-supervised learning approach for network traffic classification. Int. J. Netw. Manag. 2023, 33, e2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakopoulou, E.; Tillman, B.; Markopoulou, A. A Federated Learning approach for mobile packet classification. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.13113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Huang, K.; Yang, W.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Z. On the convergence of fedavg on non-iid data. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.02189. [Google Scholar]

- Mun, H.; Lee, Y. Internet traffic classification with federated learning. Electronics 2020, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, D. Feat: A federated approach for privacy-preserving network traffic classification in heterogeneous environments. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 10, 1274–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiang, T.; Hospedales, T.M.; Lu, H. Deep mutual learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 4320–4328. [Google Scholar]

- Gou, J.; Yu, B.; Maybank, S.J.; Tao, D. Knowledge distillation: A survey. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2021, 129, 1789–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukman, A.; Yang, C.K. Improving Deep Mutual Learning via Knowledge Distillation. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, P.; Yan, D.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z. Deep knowledge distillation: A self-mutual learning framework for traffic prediction. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 252, 124138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Lang, B. Machine learning and deep learning methods for intrusion detection systems: A survey. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper-Gil, G.; Lashkari, A.H.; Mamun, M.S.I.; Ghorbani, A.A. Characterization of encrypted and vpn traffic using time-related. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP), Rome, Italy, 19–21 February 2016; pp. 407–414. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioffe, S.; Szegedy, C. Batch normalization: Accelerating deep network training by reducing internal covariate shift. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Lille, France, 7–9 July 2015; pp. 448–456. [Google Scholar]

- De Boer, P.T.; Kroese, D.P.; Mannor, S.; Rubinstein, R.Y. A tutorial on the cross-entropy method. Ann. Oper. Res. 2005, 134, 19–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottou, L. Stochastic gradient descent tricks. In Neural Networks: Tricks of the Trade, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 421–436. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Zhu, M.; Wang, J.; Zeng, X.; Yang, Z. End-to-end encrypted traffic classification with one-dimensional convolution neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Intelligence and Security Informatics (ISI), Beijing, China, 22–24 July 2017; pp. 43–48. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).