Abstract

Wireless sensor networks (WSNs), including Software-Defined Wireless Sensors, are particularly vulnerable to Denial-of-Service (DoS) attacks. Trust models are widely acknowledged as an effective strategy to mitigate the threat of successful DoS attacks in WSNs. However, existing trust models commonly rely on threshold configurations that are based on the network administrator’s experience and leave the challenging task of weight allocation for various trust metrics to network users. This limits the widespread application of trust models as a WSN defence mechanism. To address that issue, this study proposes and theoretically analyses an Adaptive, Threshold-Free, and Automatically Weighted Trust Model (ATAW-TM) for SDWSNs. The model architecture is aligned with the layered centralized management architecture of SDWSNs, which makes it flexible and enhances its responsiveness. The proposed model does not require manual threshold configuration and weight allocation and allows for rapid trust system recovery. It has significant advantages compared to existing trust models and is potentially more feasible to implement on a large scale.

1. Introduction

A wireless sensor network (WSN) comprises spatially distributed sensor nodes, which include sensing, data processing, and communication components [1]. These nodes self-organize to create a multi-hop wireless network. The sensors can be used to detect and collect environmental or physical data, such as humidity, sound, and temperature [2]. These data are transmitted through the network to a centralized hub (a base station or a sink node) and subsequently forwarded to an Internet-based server for analysis and processing [3,4]. WSNs are widely used in a large variety of applications including military, environmental monitoring, smart homes, agriculture, animal husbandry, and health monitoring.

With Internet of Things (IoT) technology continuously evolving, WSNs have become more widely used. At the same time, their various limitations have become increasingly clear, such as when applications require the WSNs to be tailored to meet unique functional and performance requirements, and the nodes are self-configuring distributed management. These limitations create challenges in terms of dynamic network management, scalability, and node recycling. Incorporating the concept of Software-Defined Networking (SDN) (which facilitates more dynamic and manageable network operations through the functional separation of the control and the forwarding planes) into WSNs has helped meet these challenges and given rise to a new type of WSN: Software-Defined Wireless Sensor Networks (SDWSNs) [5].

1.1. Operational Features and Characteristics of SDWSNs

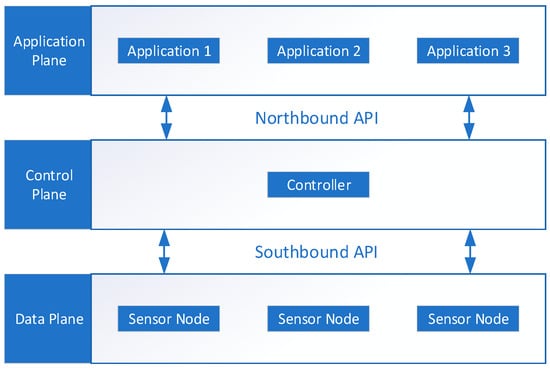

SDWSNs incorporate a centralized controller that maintains a global view of the network and dynamically configures sensor nodes through southbound interfaces, similar to OpenFlow. Figure 1 presents the basic structure of an SDWSN, which includes a data plane, an application plane, and a central controller [6].

Figure 1.

The basic structure of an SDWSN.

Unlike conventional WSNs, where decisions are distributed and often rigid, SDWSNs support the following operational features [5,6]:

- Control–data plane separation:The control plane houses the network intelligence, makes global decisions, and manages data plane behaviour. The controller builds global network views, calculates optimal paths and policies. The data plane is responsible for actual packet processing, forwarding, and data transmission based on predefined rules.

- 2.

- Flow table-based forwarding:The controller installs flow rules in data plane devices’ flow tables. These store matching rules and actions. The nodes process packets based on installed flow rules.

SDWSNs combine the flexibility of SDNs with the specific features of WSNs, which makes SDWSNs suitable for a broad range of applications. Compared to WSNs, SDWSNs have the following advantaged characteristics [6,7]:

- 1.

- Flexibility and ProgrammabilitySDWSNs provide increased flexibility and programmability by segregating control plane activities from the data plane. The decoupling supports network adjustments and optimization in response to real-time requirements.

- 2.

- Centralized ManagementSDWSNs enable centralized management, including network configuration. The behaviour and data flow of sensor nodes are coordinated by SDN controllers, which improves network management efficiency.

- 3.

- Dynamic OptimizationThe control layer enables SDWSNs to dynamically optimize the use of network resources and to adjust data routing strategies. This improves network performance and reliability.

- 4.

- Enhanced ScalabilityThe entire set of sensor nodes across the data plane is visible to the central controller, which facilitates efficient network management. This is especially beneficial in the case of large-scale network expansion.

1.2. Application Scenarios of SDWSNs

Due to these advantages, SDWSNs are increasingly considered for mission-critical and dynamic application domains [8,9], such as the following:

- Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT), where a rapid reconfiguration and reliability are crucial.

- Environmental and structural health monitoring, requiring adaptive routing in large-scale deployments.

- Emergency and disaster response, where nodes may be mobile and the network topology frequently changes.

- Military and tactical sensing, which demand centralized coordination and strict security controls.

These scenarios highlight the necessity of an architecture capable of handling dynamic conditions and enforcing fine-grained and flexible security policies.

1.3. Security Challenges and DoS Vulnerabilities in SDWSNs

Despite their advantages, SDWSNs introduce unique security risks. The centralized controller, while improving coordination, also becomes a prime target for Denial-of-Service (DoS) attacks [10]. Attackers may overwhelm the controller with excessive requests, inject false control messages, manipulate routing rules, or exploit multi-hop wireless communication to generate traffic flooding.

Furthermore, traditional cryptographic mechanisms alone cannot defend against insider nodes that behave maliciously yet possess valid keys [11]. This limitation is particularly problematic in SDWSNs, where compromised nodes can exploit controller–node interactions to degrade network performance or disrupt global routing operations.

1.4. Necessity of Trust-Based DoS Mitigation in SDWSNs

Trust models, which establish a network of trust among entities by evaluating and predicting their behaviour based on observed interactions [11], can provide effective defence against DoS attacks under uncertain conditions. These models consider the node behaviour and reputation when making decisions about trustworthiness (like how trust and reputation are established in the context of human behaviour, through continuous interaction and observation). Trust-based mechanisms can differentiate legitimate nodes from misbehaving or compromised ones, thereby achieving the following [10,12,13]:

- Detecting internal DoS behaviours that cryptography cannot address;

- Protecting the controller from unnecessary or malicious traffic;

- Supporting adaptive responses through flow rule adjustments issued by the controller.

Thus, integrating trust evaluation with the SDWSN architecture is a natural and necessary solution for mitigating DoS threats.

1.5. Target Scenario of This Study

This study focuses on a typical SDWSN deployment consisting of a central controller and multiple static sensor nodes operating in a multi-hop wireless topology. Nodes forward sensing data toward the controller, and the controller manages routing through flow table updates. The network is assumed to face internal DoS threats, such as flooding attacks, blackhole attacks, and vampire attacks caused by compromised nodes.

Our work investigates how a trust-based mechanism can be integrated into this SDWSN architecture to detect and mitigate the 14 types of DoS attacks in SDWSNs [14], ensuring stable communication.

Trust models in WSNs have gained increasing recognition and have been widely studied. Numerous trust models have been proposed, with some specifically addressing the challenges of DoS attacks. However, trust models in WSNs are still new and have not set any standards yet [15,16]. There has been extensive research on mechanisms leveraging trust evaluation to defend against DoS threats in traditional WSN environments [11,14], especially in addressing threshold limitations in trust evaluation [10,17], the assignment of weights to trust metrics [18,19,20,21], and the loss of trust information [10,22,23,24,25].

1.6. Contributions

This study addresses the research gaps above in the context of SDWSNs. It explores the design of innovative trust mechanisms applicable to SDWSNs and proposes a solution to mitigate all the 14 types of DoS attacks identified. This study makes the following research contributions:

- A three-layer trust framework (node, cluster head, and controller) to address a wide range of DoS attacks in SDWSNs.

- A combined method of outlier detection and the Bayesian Beta approach to calculate direct trust values within the layered architecture of SDWSNs’ trust model. This approach eliminates the dependency on threshold-setting algorithms that rely on network administrators’ prior knowledge of specific SDWSNs.

- A method for integrating reciprocal weighting and entropy-based weighting to automatically assign adaptive weights to various trust metrics across the control and data planes of SDWSNs. This approach eliminates the inaccuracies in combined trust value calculations caused by fixed weights and the difficulties users face in assigning weights.

- A method for referencing the logistic function that converts the difference between historical combined trust values and current combined trust values into an aging factor. Within the centralized control framework of SDWSNs, this allows for dynamic automatic adjustment of the aging factor. Consequently, when a node exhibits malicious behaviour, its trust value decreases rapidly, and when it returns to normal behaviour, its trust value increases slowly.

- A trust information retrieval mechanism tailored for SDWSNs’ hierarchical structure that enables both member nodes and cluster head (CH) nodes to quickly recover lost trust information from the controller or cluster level. This feature leverages the centralized control and global visibility of SDWSNs to ensure the robustness and resilience of the trust management system after information loss.

The structure of the remainder of this paper is as follows: Section 2 provides an overview of related work. Section 3 presents the proposed trust model (ATAW-TM). Section 4 analyses ATAW-TM within the context of the existing literature, highlighting its contributions. Section 5 discusses the results and concludes the paper; directions for future research are also outlined.

2. Related Work

There has been extensive research on mechanisms leveraging trust evaluation to defend against DoS threats in traditional WSN environments, including the identification of trust evidence necessary for trust models to effectively detect DoS attacks [18,22,26,27], developing methods for trust evidence extraction [28,29,30], and the trust computing techniques that facilitate the design of robust and reliable trust mechanisms to defend against DoS attacks [23,31,32]. In our extensive literature review [14], we identified existing approaches and challenges in developing adaptive trust mechanisms for detecting and defending WSNs against diverse DoS threats. However, research on using trust-driven approaches to address DoS vulnerabilities in SDWSNs remains limited, with only four studies available to date [10,12,13,33].

2.1. ETMRM: Trust-Based Routing and Management in SDWSNs

In 2018, Wang et al. [10] developed a trust-based routing and management scheme (ETMRM) that was designed to enhance energy efficiency in SDWSNs, aimed at mitigating new flow attacks and selective forwarding attacks. This study leverages trust management methodologies initially designed for conventional WSNs. These techniques are combined with SDN flow tables and reporting mechanisms. The integration is carried out within the SDN-WISE model [8,34], an SDN-based framework for wireless sensor networks. Through this approach, the study establishes an initial trust model specifically designed for SDWSNs. This model has seven steps: recording trust, evaluating local trust, reporting trust, combining trust values, evaluating global trust, finding and isolating malicious nodes, and calculating routes based on trust.

To collect trust evidence, the trust record leverages an enhanced flow table to monitor successful and unsuccessful transmissions, encompassing both data and control packets, as well as new flow packets that do not align with existing rules. During the local trust evaluation phase, forwarding trust is determined using a Bayesian Beta approach, while new flow trust is assessed through a threshold-limiting technique. Nodes compile their local trust values for all neighbours into SDN-WISE messages, which are subsequently sent to an aggregation node. This node consolidates the data and relays it to the controller. The controller evaluates network-wide trust scores, identifies nodes exhibiting malicious behaviour, and issues packet drop policies to neighbouring nodes impacted by the threat. When a new flow packet arrives, handling of the relevant rule request is delegated to the controller. It determines the routing path by referencing trust values, considering the node’s network-wide trust score and remaining energy level.

The model has undergone prototyping, with experimental results demonstrating its capability to mitigate the effects of new flow and selective forwarding attacks while ensuring more balanced energy consumption. Nevertheless, the model evaluates trust solely within a single cycle during the local calculation phase, disregarding historical trust data. Incorporating past behaviours could enhance the robustness of trust assessments. Furthermore, the model’s defence is limited to control plane DoS attacks (new flow attacks) and does not address data plane DoS attacks, as it lacks mechanisms to log and analyse non-new flow data packets.

2.2. Hierarchical Trust Management for SDWSNs

Bin-Yahya et al. [12,33] proposed a hierarchical trust management scheme (HTM) for secure communications in SDWSNs. This model calculates and records the trustworthiness of each node at various levels (node, CH, and controller) to promptly detect malicious nodes. In this approach, distinct trust values are maintained for control traffic and data traffic, where the trust evidence is derived from metrics including successful versus unsuccessful forwarding of control and data messages, together with their associated transmission rates.

Forwarding trust is assessed using a Bayesian method, while sending trust is evaluated through a threshold-limiting technique. Each node computes trust values for its neighbours and initiates trust update messages. The cluster head aggregates these updates, forwards them to the sink node, and finally transmits them to the controller. Trust aggregation is performed at both the cluster head and controller levels, with lower weights assigned to outliers based on score reliability during the aggregation process. To enhance responsiveness to malicious activities, the scheme integrates reward and penalty factors into the Bayesian model. It also capitalizes on specific characteristics of SDWSNs, such as leveraging flow table statistics collected by the controller and using designated control messages to evaluate intermediate nodes’ behaviour. This scheme demonstrates high effectiveness in detecting a range of attacks and shows a superior performance compared to ETMRM [10] in detecting DoS attacks.

2.3. SDWSN Trust Management Framework with an Intrusion Detection System

Isong et al. [13] introduced an innovative Trust Management Framework (TMF) tailored for SDWSNs. This scheme incorporates two levels of trust evaluation: sensor-to-sensor (S2S) and controller-to-sensor (C2S) trust. It is structured into three key components: the information tracking component, the trust evaluation component, and the control logic component. The information tracking component gathers data from two sources: packet forwarding information collected via the sink node and network statistics obtained from the controller. This information is retained by both the controller and the sink node for further analysis. The trust evaluation component calculates a trust score through both observed and inferred methods. The observed trust relies on the quantity of packets the individual node successfully forwards and receives, while inferred trust is derived through traffic data analysed by an Intrusion Detection System (IDS) model. To ensure continuous monitoring, the controller periodically retrieves statistical data from all network nodes. Finally, the decision-making unit utilizes the computed trust values to determine appropriate actions, such as isolating or monitoring nodes identified as malicious. This systematic approach allows the framework to enhance security by effectively detecting and addressing potential threats.

Although researchers have developed many IDSs based on anomaly detection, signature matching, and deep packet inspection, their applicability in SDWSNs remains limited for several reasons. First, SDWSNs operate under stringent resource constraints, and deep packet inspection or complex machine-learning-based IDS modules often exceed the computational and energy budgets of sensor nodes [35]. Second, most IDS techniques assume stable and high-bandwidth links, whereas SDWSNs frequently involve dynamic topologies, intermittent connectivity, and distributed wireless interference [36]. Third, IDSs typically react after malicious traffic is observed, while DoS attacks in SDWSNs can rapidly exhaust critical control-plane resources [12], such as flow-table entries or southbound communication channels, before IDS mechanisms can respond.

2.4. Research Gaps

A major limitation of the models reviewed above is the lack of focus on the integrity of the trust evidence. Moreover, the impact of variations in communication channel conditions on the reliability and precision of trust assessment is overlooked by all above existing approaches. Additionally, the first two implemented and evaluated models have three research gaps we previously identified: setting a threshold in trust evaluation, assigning weights to trust metrics, and addressing the loss of trust information. In the last model, the responsibility for trust evaluation is delegated to the IDS module, but the specific evaluation methods within the IDS module are not discussed in depth. SDWSNs require proactive and lightweight security mechanisms capable of detecting or mitigating DoS behaviour early and continuously, rather than relying solely on traditional IDS approaches. This motivates the exploration of trust-based models.

3. Materials and Methods

The proposed Adaptive, Threshold-Free, and Automatically Weighted Trust Model (ATAW-TM) is a trust model specifically designed for SDWSNs to detect DoS attacks within these networks. It eliminates the reliance on human prior knowledge during application, enhancing its usability, and incorporates trust information backup and rapid recovery mechanisms to improve stability. The model is implemented using SDN-WISE as the underlying architecture, with the SDN controller embedded within the sink node to simplify network design and reduce overheads.

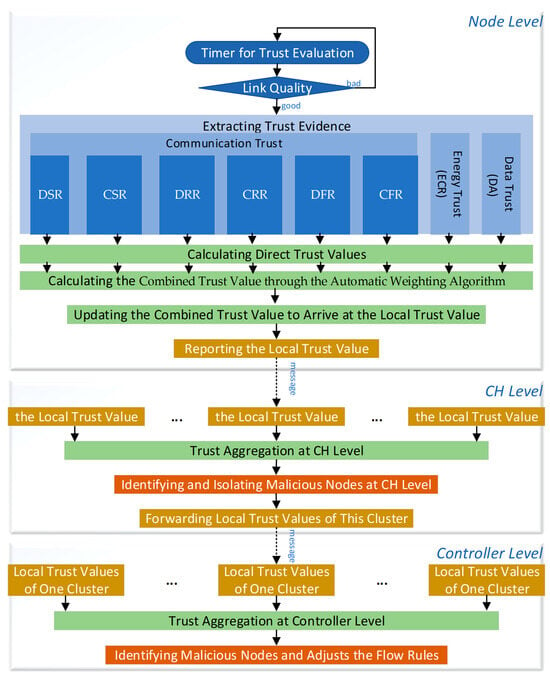

ATAW-TM adopts a three-tier hierarchical architecture, comprising the node level, cluster head (CH) level, and controller level. Each level contributes to a layered and cooperative trust evaluation and decision-making process. An overview of the ATAW-TM is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Overview of the ATAW-TM. Different colours in the figure represent distinct functional categories in the trust management process: blue blocks denote different sources of trust evidence; dark blue blocks represent initial trust evaluation inputs such as link quality and timer operations; green blocks indicate trust com-putation and aggregation procedures; yellow blocks represent reporting or forwarding operations, such as transmitting local trust values; and orange blocks denote security-related decision actions, specifically identifying and isolating malicious nodes and adjusting flow rules.

At the node level, each sensor node performs its own node-level evaluation process. First, start a timer for trust evaluation to perform periodic trust assessments. Second, nodes are tasked with extracting trust evidence and performing direct trust computation locally. At the beginning of each trust evaluation, assess the link quality between the node and its neighbouring nodes. If the link quality is good, continue with the evaluation process; if the communication link becomes unstable or weak, wait for the next evaluation round. During the evaluation, nodes extract trust evidence and compute the direct trust value locally. Trust evidence encompasses communication, energy, and data indicators. Communication-related trust indicators include metrics such as the transmission and reception rates of both data and control packets, as well as their respective forwarding rates. These indicators were identified in [14] as the eight types of trust evidence, including the data packet sending rate (DSR), control packet sending rate (CSR), data packet receiving rate (DRR), control packet receiving rate (CRR), data packet forwarding rate (DFR), control packet forwarding rate (CFR), energy consumption rate (ECR), and data accuracy (DA).

Next, each direct trust value corresponding to these metrics is then employed to calculate the combined trust value through an automatic weighting algorithm that integrates the direct trust values derived from individual metrics. The historical and current trust metrics are weighed using an aging factor to reflect temporal relevance, resulting in the local trust value. Finally, nodes periodically send their local trust value to the CH of its respective cluster.

The CH is responsible for collecting the local trust value reported by each node and forwarding the report message to the controller. It calculates the aggregated trust value by weighted averaging of the local trust values received from each node using its own calculated local trust value, and it relays trust values to the controller. The CH uses the aggregated trust value to recognize node maliciousness. Subsequently, it halts forwarding any messages to and from malicious nodes, thus segregating detected malicious nodes.

The controller, positioned within the sink node, gathers trust values from all nodes and computes their aggregated trust values from a global perspective. It identifies malicious nodes according to their aggregated trust scores. It then adjusts the flow rules to isolate the identified malicious nodes.

3.1. Node-Level Operations: Extracting Trust Evidence

3.1.1. Assessing Link Quality

Before each trust evaluation, it assesses the quality of connections linking the node with its neighbouring nodes to avoid a low link quality affecting the trustworthiness scores of legitimate nodes. Because of the openness of WSNs’ wireless communication, the links between sensor nodes are unstable and can be influenced by the environment. With low-quality links, the communication capability decreases, causing reductions in the rates of packet transmission, reception, and forwarding, thus resulting in a lower calculated trust value.

In ATAW-TM, we use the method proposed in [19] to evaluate the link quality, which relies on the Link Quality Indicator (LQI). In the widely adopted CC2420 ratio, the LQI is calculated from the first eight symbols of a received packet, ranging between 0 and 255. The proposed method involves the evaluation node collecting LQI data over a specific period of time, followed by the calculation of the mean value. If the calculated mean surpasses the threshold, such as 220, the link is considered normal, and the evaluation process continues. If the mean value is below the threshold, the link is considered unstable, and the assessment is temporarily halted and resumed in the next cycle to re-evaluate the link quality.

To prevent attackers from intentionally manipulating link quality indicators (LQIs) to evade trust evaluation, we use a robustness mechanism. This conducts neighbour consistency checks by comparing LQI patterns across adjacent nodes. If a single node’s LQI decreases while most of its neighbours (more than a threshold θ) remain normal, the node’s degraded LQI is treated as suspicious, and it continues to undergo trust evaluation. In contrast, if LQI degradation is observed across most nodes in the neighbourhood, the drop is likely caused by environmental interference, and trust evaluation for all nodes in that neighbourhood is suspended. This prevents attackers from exploiting LQI manipulation to bypass detection.

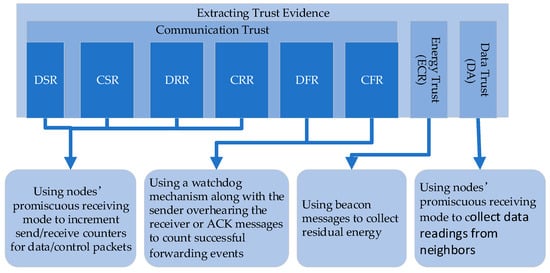

3.1.2. Extracting Trust Evidence

Figure 3 below illustrates the trust evidence included in our trust model, along with the corresponding extraction methods.

Figure 3.

Trust evidence and the corresponding extraction methods.

The rates at which data and control packets are sent and received are extracted using the sensor node’s promiscuous receiving mode. When this mode is enabled, any packet within the node’s receiving range (whether intended for it or another node) is processed. The packet count for a given node is raised by one whenever a data or control packet from that node is identified. Additionally, by examining each incoming packet’s destination address and type, the system determines the target node and updates its associated count.

The forwarding rates for data and control packets are determined using listening methods as follows. Promiscuous receiving mode is activated on the sensor node to allow the capture of all surrounding traffic. Once the node is ready to monitor forwarding behaviour, it transmits a packet and starts a watchdog timer. During this monitoring window, the node observes the actions of the intended recipient. Successful forwarding is recorded if the target recipient relays the packet prior to the expiration of the timer; otherwise, failed relaying is logged. Furthermore, to assess the control packet forwarding rate, the ACK-based mechanism can be employed as a supplementary technique alongside the listening method. Forwarding is considered successful if the forwarded packet or its corresponding ACK message is detected.

Using the remaining energy information embedded in beacon messages, the ECR of a node is calculated. This rate is then compared to the ECRs of other nodes to identify any differences.

For data trust evidence, the sensor node collects readings from all its neighbouring nodes using the open receiving mode. It then determines whether there is data deviation by comparing these readings with the neighbourhood data references.

3.2. Node-Level Operations: Calculating, Updating, and Reporting Trust Values

3.2.1. The Process of Direct Trust Value Calculation

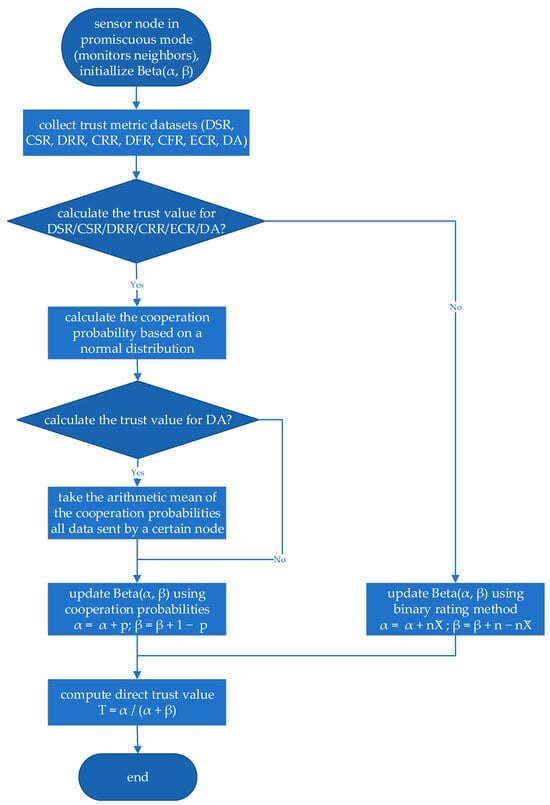

To overcome the obstacle of threshold setting in the threshold limitation approach that relies on the network administrator’s a priori knowledge of the particular network, we assign a cooperation probability to each value through the outlier detection method when calculating the direct trust values for DSR, CSR, DRR, CRR, ECR, and DA, and then we use the Bayesian Beta method to derive the direct trust values.

In contrast, the forwarding-related metrics, DFR and CFR, represent fundamentally different types of evidence. Forwarding is not a continuous measure but a discrete binary event: a packet is either forwarded successfully or it is not. Consequently, it is neither meaningful nor necessary to compute a probabilistic cooperation value based on distributional assumptions. Instead, forwarding trust is modelled using a binary assignment, where successful forwarding (observed through listening or ACK mechanisms) is assigned a cooperation value of 1 and unsuccessful forwarding is assigned a value of 0. These binary outcomes are then directly incorporated into the Bayesian Beta method. The processes of direct trust value calculation are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The processes of direct trust value calculation.

The evaluation is conducted over a defined period of time using the following framework for each metric. At the start of an evaluation period, we initialize the Beta distribution parameters for each metric: the count of cooperative interactions (α) and the count of non-cooperative interactions (). These two parameters form the basis for calculating trust values. The initial state for all nodes and all metrics is set to zero ( = 0, = 0), indicating no prior history.

Next, the node collects trust metric datasets for each metric. The cooperation probability () is calculated using a Gaussian distribution model based on the collected trust metric datasets. This allows the node to determine the likelihood that its neighbours are behaving cooperatively. It is used to update the and parameters. The direct trust value () is computed from and as the expected value of the Beta distribution at the end of the period, representing the trustworthiness of a node in a specific metric.

3.2.2. The Method of Cooperation Probability Calculation

Multiple studies, through experiments or simulations, have verified that in WSNs where node behaviour is independent, homogeneous, and static, the traffic of nodes and the collected sample data approximately follow a Gaussian distribution when the number of nodes is large enough [37,38,39]. Therefore, we adopt a cooperation probability calculation method based on a Gaussian distribution.

The packet size is a common feature in traffic analysis and intrusion detection [40]. However, it is not included in the proposed trust model because DoS attacks typically manifest through abnormal transmission rates and forwarding behaviours rather than size anomalies [14]. This design choice reduces the computational overhead while maintaining detection effectiveness. Let us assume that the evaluation node is node , and the set of all neighbouring nodes being evaluated is represented as . In an evaluation period, node monitors its neighbours to build datasets for calculating the cooperation probabilities. The specific data collected for each metric is outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Dataset for each metric.

This method assumes that the data follows a Gaussian distribution, meaning most data points are concentrated around the mean, and the probability of data points appearing decreases as they deviate further from the mean. Assume the data sample set collected by the sensor node is . First, it is necessary to calculate the mean and standard deviation of the dataset as shown in Equations (1) and (2),

which are the basic parameters required for calculating the Gaussian distribution. For each data point , the probability density value can be calculated using the Gaussian distribution probability density function as shown in Equation (3):

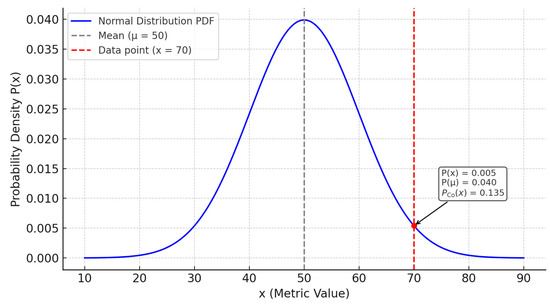

where is the normalization constant of the Gaussian distribution, ensuring the total probability is 1, and is the probability density value for each data point, reflecting the degree of deviation of the data point from the mean. is not the actual probability but the probability density value, indicating the relative frequency of occurrence near that point. The higher the density, the closer the data point is to the center (mean), and the higher the probability of occurrence; the lower the density, the further it is from the mean, possibly indicating an outlier. The curve of a Gaussian distribution probability density function is shown in Figure 5. In this figure, the mean (μ) is 50 and the standard deviation (σ) is 10.

Figure 5.

Gaussian distribution PDF curve.

Then, we define the cooperation probability of a data point as the ratio between its probability density and that of the mean, as shown in Equation (4),

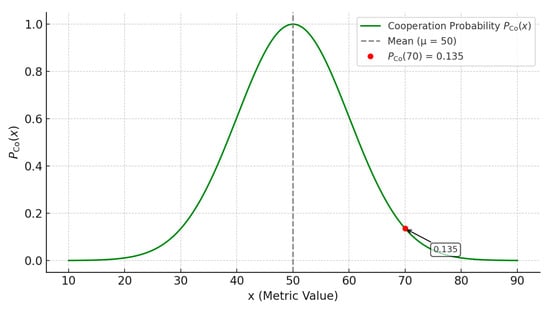

where represents the cooperation probability of . The function curve of our cooperation probability is shown in Figure 6. In this figure, the values of paraments μ and σ are the same as in Figure 5.

Figure 6.

Cooperation probability function curve.

From this figure, we can see the range of the cooperation probability is from 0 to 1. The closer the value is to the mean, the closer its cooperation probability is to 1; the further away from the mean, the closer its cooperation probability is to 0.

Since a single node sends multiple data packets ( packets, where varies per node), a unique method is used to compute its overall DA cooperation probability. The final for a node is the arithmetic mean of the cooperation probabilities calculated for each individual data packet it sent during the period, as shown in Equation (5),

where represents the DA cooperation probability of node , represents the cooperation probability of the DA for the kth data transmitted by node , and represents the total number of items sent by node during the evaluation period.

3.2.3. The Method of Direct Trust Value Calculation

The direct trust value is then computed using the classical Bayesian Beta approach. Ganeriwal et al. [11,41] provided a detailed investigation into how Bayesian formulations and Beta distributions can be applied to trust modelling within WSNs. They extended the cooperation metric from a binary rating to an interval rating, meaning it is no longer simply cooperative or non-cooperative but is a probability. They applied the Dirichlet process and derived that the parameter update formulas for binary ratings are similarly applicable to interval ratings. After a single transaction, if the assigned cooperation probability is , the Beta parameters are updated as shown as Equation (6).

From the viewpoint of node , the parameters and characterize the cooperative and non-cooperative behaviours observed between nodes and at the initiation of a transaction. Similarly, and characterize the cooperative and non-cooperative behaviours of nodes and as observed by node upon the completion of a single transaction. The trust score of node computed from node ’s perspective is the expected value of the beta distributions, which can be easily computed, as shown in Equation (7).

We consider the behaviour of sending or receiving packets within an evaluation period as a single transaction. By substituting Equation (6) into Equation (7), we can derive the method for calculating the direct trust values for DSR, CSR, DRR, CRR, ECR, and DA at the end of an evaluation period, as shown in Equation (8),

for each metric , where represents six behavioural metrics (DSR, CSR, DRR, CRR, ECR, and DA), respectively.

and represent the count of cooperative interactions and the count of noncooperative interactions of metric of node . represents the assigned cooperation probability for node with metric . This probability is calculated based on observed behaviours. It is used to update the and parameters. represents the direct trust value of node in metric . This value is computed from and at the end of the period. The relationship between these parameters for all six metrics is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

The relationship between these parameters for all six metrics.

3.2.4. The Specific Case of DFR and CFR

The direct trust values for DFR and CFR are also calculated using the classical Bayesian Beta method, as shown in Equation (5). However, unlike other trust metrics, there is no need to calculate the cooperation probability of the dataset. Instead, the cooperation probability is defined as a binary number, either 1 or 0, as in Equation (4), where is 1 or 0. When it is confirmed through monitoring or ACK methods that node has successfully forwarded a packet, is assigned a value of 1; otherwise, it is assigned a value of 0. At the end of the evaluation period, the Beta parameters are updated, as shown in Equation (9),

where represents the total number of data or control packets that node either successfully forwarded or failed to forward during the evaluation period. For each forwarding action, a cooperation rating is assigned: if the packet was forwarded successfully, and otherwise. These ratings form the set: = {, , , …, } ∈ {0, 1}. By substituting Equation (9) into Equation (5), the formula for the direct trust values of DFR and CFR at the end of an evaluation period is obtained, as in Equation (10),

where and represent the direct trust values of DFR and CFR for node respectively. The parameters , , and represent the counts of cooperative and non-cooperative forwarding actions for data and control packets, respectively, at the beginning of an evaluation period. For initialization, all Beta parameters are set to zero.

3.2.5. Calculating the Combined Trust Value

When calculating the combined trust value, we use a method that combines the reciprocal method and entropy-based method [42] to assign weights to the direct trust values of each trust metric.

By taking the reciprocal of the direct trust values, we assign higher weights to lower trust values, accelerating the decline of combined trust for anomalous nodes. This helps achieve the goal of quickly identifying malicious nodes. We form a dataset of all direct trust values, organized according to the trust metrics in the sequence: , , , , , , , represented as . The weighting scheme for each trust metric, illustrated in Equation (11),

is derived by applying the reciprocal function to each trust value. represents the weighting factor assigned to the direct trust value from node to node j

for the rth trust metric. The values of ranges from 1 to 8. is a very small number serving to prevent division by zero.

Building on the reciprocal method, we further use the entropy-based method to adjust the final weights. Entropy-based weighting is often interpreted as reducing the weight of highly uncertain information sources. In contrast, our design adopts a security-oriented interpretation: when a specific trust metric exhibits high volatility within a neighbourhood, this volatility frequently reflects a stronger discriminative power for identifying abnormal behaviour. Thus, after reciprocal weighting penalizes low trust values, entropy is used to amplify metrics that better separate benign from malicious behaviours. By calculating the “volatility” (entropy) of each metric, we automatically identify which metrics are more important in the network scenario and accordingly increase the weights of these trust values. This allows the trust evaluation to automatically adapt to different network or attack scenarios. For example, in scenarios where the attack affects transmission rates, such as alarm systems, the trust value weights of communication metrics are automatically strengthened. In scenarios where the attack aims to affect DA, such as medical monitoring systems, the impact of DA metrics is automatically amplified.

Shannon’s information theory defines entropy as a fundamental metric for quantifying uncertainty in a system [42]. If a random variable has a set of possible values with a corresponding probability distribution , then the entropy is defined as shown in Equation (12):

where ) represents entropy of the random variable ; represents the probability of the event and represents the base of the logarithm, typically (for bits), (for natural entropy, in nats), or . The more uniform the probability distribution, the greater the entropy, and the higher the uncertainty of the system. The choice of the logarithmic base in entropy calculation significantly affects the sensitivity and discrimination of the resulting weights. In this study, we choose base for the entropy function, as it offers higher sensitivity to ‘probability imbalance’. To illustrate the effect of the logarithm base, consider a simple probability distribution: Let . Then, entropy values computed with different bases are show in Table 3.

Table 3.

Entropy values computed with different bases.

Among these three entropy values, the binary entropy value is the largest, indicating that it is more sensitive to the degree of value fluctuation. Furthermore, we calculate the information entropy with bases , , and for the probability distributions (0.8, 0.2), (0.6, 0.4), and (0.5, 0.5), respectively, and perform a comparative analysis, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Entropy values of different probability distributions computed with different bases.

From Table 4, we can see that the difference in entropy values for different probability distributions is the largest when the base is . Therefore, in our trust model, when using base for the entropy function, can more clearly distinguish which trust metrics are more important. For normalization, we use the factor , which ensures that the entropy values are scaled to the [0, 1] interval.

First, we ‘normalize’ each trust metric to form a pseudo-probability distribution, so that it can be used as an input for information entropy to measure the fluctuation of each metric. Suppose the dataset of the rth trust metric collected by node from all its neighbouring nodes is . Normalize this trust metric as shown in Equation (13),

where denotes the count of immediate neighbours of node . is the pseudo-probability distribution corresponding to , .

To quantify uncertainty in the rth trust metric, we employ Equation (12) to compute its entropy and normalize it as shown in Equation (14),

where represents the normalized entropy of the rth metric calculated by node within its neighbourhood. The smaller the , the greater the variation, and the more important the metric, which should be given a higher weight. The entropy weight factor calculation method is shown in Equation (15),

where represents the entropy weight factor for the rth metric calculated by node within its neighbourhood.

3.2.6. Combining Reciprocal Weighting and Entropy-Based Weighting

Following the reciprocal computation, the weights are modified using the adjustment factor , and normalized to produce the final set of weights, as illustrated in Equation (16),

where represents the weight of the rth trust metric.

Finally, to derive the combined trust score, we compute the weighted average of all trust metrics, as specified in Equation (17),

where denotes the combined trust score assigned by node to node j.

3.2.7. Updating the Local Trust Value at the Node

We adopt an asymmetric update strategy in which trust values drop rapidly upon detecting abnormal behaviour and recover gradually during normal operation. This design follows common principles in trust management for WSNs, where rapid decay improves responsiveness to potential attacks while slow recovery prevents malicious nodes from regaining trust too quickly [11]. Previous research showed that the unified decay–recovery strategy provides a stable performance across these behaviours without requiring attack-specific tuning [21,43].

By weighing the historical and current combined trust values with an aging factor, we derive the local trust value. To achieve a rapid decline in trust value when a node exhibits malicious behaviour and a slow recovery of trust value after the node returns to normal behaviour, we use a dynamically and automatically adjusted aging factor. Based on the logistic function [44] we perform a nonlinear transformation to convert the change from the historical to the current combined trust value into an aging factor. We introduce explicit parameters for the slope () and midpoint (), making the behaviour of the aging factor more transparent and tunable, as shown in Equation (18),

where denotes the current moment, and denote the combined trust values from the previous and current evaluation periods, respectively, denotes the evaluation period, and denotes the aging factor.

As indicated by the formula, a higher current combined trust value relative to the historical value results in an aging factor close to 1, while a lower value leads it closer to 0.

Then, the combined trust value updated through the aging factor is used as the local trust value, as shown in Equation (19),

where represents the value of local trust. When a node exhibits malicious behaviour, the current combined trust value decreases, the aging factor becomes smaller, and the weight of the current combined trust value increases, causing the local trust value to decline rapidly. Conversely, when the node returns to normal behaviour, the current combined trust value increases, the aging factor becomes larger, and the weight of the historical combined trust value increases, causing the local trust value to rise slowly.

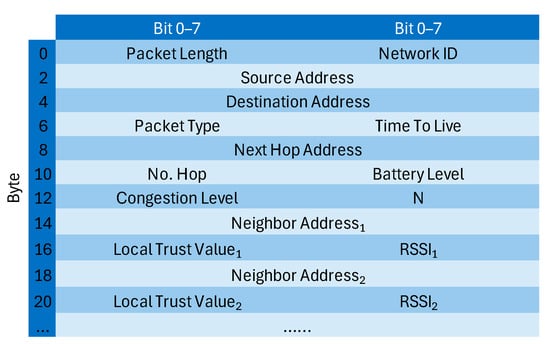

3.2.8. Reporting the Local Trust Value

Each node needs to periodically send its local trust values for all its neighbours to the CH and the controller for trust aggregation. To avoid introducing an additional transmission overhead, we use the method from ETMRM [10] for reporting local trust values. Instead of generating separate trust packets, each node embeds the trust values into the SDN-WISE report messages that are sent to the controller as part of the standard control-plane operation. As in the native SDN-WISE architecture, the cluster head forwards the report messages from all nodes in the cluster to the controller, enabling centralized trust aggregation. SDN-WISE report messages use a compact binary format optimized for resource-constrained sensor nodes. Figure 7 shows the message structure used in this work.

Figure 7.

The format of the SDN-WISE report message.

To ensure that trust dissemination remains lightweight, the real-valued trust scores computed in the previous section (ranging from 0 to 1 and represented as 4-byte floating-point numbers) are converted into 1-byte unsigned integers in the range of [0, 100], following the approach in ETMRM [10], as shown in Equation (20).

This compression significantly reduces the size of the embedded trust data and enables the inclusion of multiple trust values without increasing the overall packet size beyond SDN-WISE’s normal control-message budget. Consequently, the trust-reporting mechanism integrates seamlessly with existing SDN-WISE control-plane messages and incurs negligible communication costs.

3.3. CH-Level Operations

3.3.1. Collecting the Local Trust Values of Cluster Member Nodes

The CH node also calculates local trust values for its neighbours. After receiving the SDN-WISE report message from its cluster member nodes, the CH node reads the reported local trust values from these messages. These secondhand trust values, along with the local trust values calculated by the CH node itself, are stored in the global array of the CH in the form of a matrix, as shown in Equation (21),

where denotes the local trust value that node assigns to node , its neighbour. is the total number of nodes within the cluster, . If node j

is not within the neighbourhood of node , then node cannot perform a trust evaluation on node . In this case, equals 0. Node is not allowed to evaluate itself, so its self-trust value is set to 0.

3.3.2. Trust Aggregation at CH Level

In the trust aggregation process, we adopt the approach proposed by Bin-Yahya et al. [12], which incorporates two key metrics: score reliability and node reliability. To compute score reliability, we measure how much a local trust value deviates from the average of all local trust values assigned to the evaluated node by its neighbours. We then use this metric to calculate node reliability and to assign weights to each trust value during aggregation.

To determine node reliability, we take the arithmetic mean of the score reliability values corresponding to a node’s trust evaluations of all its neighbours. This metric enables us to identify nodes that may be engaging in trust manipulation behaviours, such as good-mouthing or bad-mouthing attacks.

To calculate the score reliability metric, we first need to compute the arithmetic mean of the local trust values of node given by all its neighbour nodes within the cluster. We take all elements greater than 0 in the jth column of the matrix and calculate their arithmetic mean, as shown in Equation (22),

where represents the group of neighbouring nodes associated with node , and represents the total count of node ’s neighbours. Then, we calculate the score reliability of the local trust value assigned by node to node using Equation (23).

Then, to compute the node reliability metric, we use the score reliability metrics as inputs, as shown in Equation (24),

where represents the node reliability metric of node , represents the set of neighbour nodes of node , and represents the total count of node ’s neighbours. The node reliability metric is iteratively updated using the historical and current values according to the method in Equation (19).

To aggregate local trust values based on the score reliability metric and the node reliability metric, we set a lower threshold for the node reliability metric, and we only aggregate the local trust values given by nodes whose node reliability metric exceeds this threshold. We derive the aggregated trust value using the method outlined in Equation (25),

where C represents the group of node ’s neighbour nodes within the cluster whose node reliability metric exceeds the threshold. is the local trust value given by node of node , and is the score reliability metric of that local trust value. is the aggregated trust value of node at the CH level.

3.3.3. Forwarding the Local Trust Values

CH periodically sends its local trust values for all its neighbours to the controller through the SDN-WISE report message. Additionally, it forwards the SDN-WISE report messages from the cluster member nodes to the controller. These messages contain the local trust values computed by each node for its immediate neighbours.

3.3.4. Identifying and Isolating Malicious Nodes at CH Level

The CH detects malicious nodes by analysing the aggregated trust values of cluster members. It then stops forwarding any messages to the malicious nodes and stops forwarding any messages from the malicious nodes.

3.4. Controller-Level Operations

3.4.1. Collecting the Local Trust Values of All Nodes in the Network

Upon receiving an SDN-WISE message from a network node, the controller extracts the local trust values of neighbouring nodes embedded in the message. These values are then organized into a matrix and stored in the controller’s global array, following the method outlined in Equation (21). This trust matrix offers a comprehensive global view of the network’s trust landscape.

3.4.2. Trust Aggregation at Controller Level

In conducting trust aggregation at the controller level, we apply the same approach as that used at the CH level. The computation is grounded in the trust matrix, which provides a global perspective, as previously introduced.

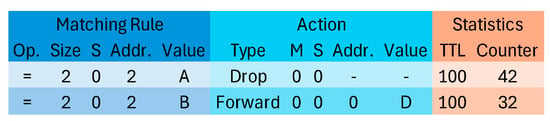

3.4.3. Identifying and Isolating Malicious Nodes at Controller Level

The controller detects malicious nodes by evaluating the aggregated trust values within the network. It then adjusts flow rules. If the detected malicious node is the CH, a new CH needs to be selected, and the network topology needs to be re-established. When a malicious node is identified as a regular node, a control message with a drop rule is sent by the controller to the CH of the corresponding cluster. The CH then propagates the control message throughout its cluster by forwarding it to each member node. Upon receiving this control message, the member nodes modify the flow table stored locally. This modification includes inserting a drop rule <src_addr = ‘j’, action = ‘Drop’> into the flow table and removing the rule with <next_hop = ‘j’> from the flow table to avoid forwarding packets to the malicious node. In SDN-WISE, the flow table includes three parts: Matching Rules, Actions, and Statistics. Figure 8 is an example of a flow table in SDN-WISE. For specific explanations of each field, please refer to SDN-WISE [8,34].

Figure 8.

An example of a flow table in SDN-WISE. Different background colours in the table represent different functional categories: the blue back-ground indicates the matching-rule fields used for packet comparison; the light blue background denotes the action fields specifying how the packet is processed; and the orange background rep-resents statistical information related to the rule, such as TTL and the packet counter.

3.5. Retrieval of Trust Information

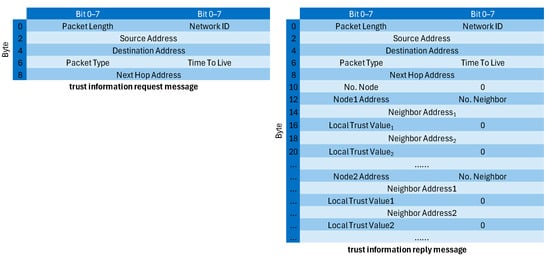

We assume that the controller has unlimited storage resources, allowing for full backup of trust information, and the single point of failure problem of the controller is not addressed in our work. Therefore, only ordinary sensor nodes and CH nodes need to retrieve trust information after it is lost. Since the controller acts as a global repository of trust information for the entire network and each CH manages the trust data of its respective cluster, both cluster heads and ordinary nodes have the ability to recover missing trust records by accessing the controller or the CH. Therefore, we define a pair of new messages based on the existing SDN-WISE messages to request and return trust information. These messages are only exchanged when trust information is lost and do not burden normal communication. The trust information request message does not carry any payload, while the trust reply conveys either cluster-wide trust information or the trust record of the requesting node. The message structures are shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

The format of the trust information request/reply message.

The “No. Node” field in the trust information reply message indicates the number of nodes whose trust information is included in the message. If a node requests trust information from the CH, the value of this field in the CH’s reply message is 1. When a cluster head (CH) requests trust data from the controller, the reply message contains a field specifying the number of nodes that belong to the CH’s cluster. Within the message format, “Node1 Address” identifies the address of Node 1, while “No. Neighbour” indicates how many neighbouring nodes are associated with Node 1. Following this, the reply provides the detailed addresses and trust values of each neighbouring node. Node 2’s trust information is added sequentially after Node 1’s in the same structure, and this continues until the trust records of all cluster nodes are included.

We incorporate a set of lightweight protection mechanisms suitable for the security of this recovery mechanism. First, all trust retrieval requests and replies should be authenticated by cryptography technologies [45] to prevent forgery. Second, the controller and cluster heads enforce per-node rate limiting through token-bucket mechanisms [46] to restrict excessive requests. Third, suspicious request patterns (e.g., bursts of retrieval messages) are monitored by the controller and can trigger temporary throttling or blacklist actions. These mechanisms provide protection without incurring significant overheads.

4. Results and Analysis

In this section, we present the theoretical analysis of the key algorithm in ATAW-TM. We implemented these algorithms in Python 3.13.9 and applied them to representative datasets to analyse and evaluate their performance.

4.1. Theoretical Analysis Using Cooperation Probability and Bayesian Inference

We begin by analysing the calculation of direct trust values of eight trust metrics using cooperation probabilities and Bayesian inference. We take the DSR metric as an example. Cooperation probabilities are computed using a Gaussian distribution-based formula, and trust values are subsequently calculated through Bayesian inference.

4.1.1. Arithmetic Mean and Standard Deviation Calculation

The dataset consists of data packet sending counts from 20 neighbouring nodes in one evaluation period. The values are as follows:

The mean () and standard deviation () of the dataset are calculated using Equations (1) and (2). The result is , .

4.1.2. Cooperation Probability Calculation

The cooperation probability for each node is computed using Equation (4).

4.1.3. Using Bayesian Inference to Calculate Direct Trust Values

The Bayesian inference process is used to calculate the trust values of each node. Initially, the parameters of the Beta distribution are set to and . We use Equation (6) to update the parameters of the Beta distribution and use Equation (8) to calculate the direct trust values. The calculated direct trust values for each node are as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Direct trust values for each node.

4.1.4. Direct Trust Value Calculation Analysis

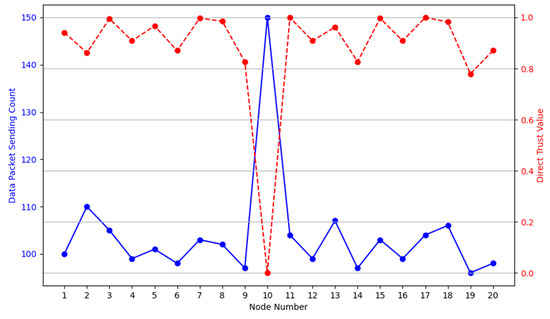

The calculated direct trust values indicate the level of trust each node has within the network based on their observed cooperation behaviour. The number of data packets sent by Node 10 is 150, much higher than the average of 103.9, which is inconsistent with the behaviour of other nodes. The calculated direct trust value of Node 10’s DSR is close to 0. This effectively identifies Node 10 as a potential malicious node exhibiting a flooding attack. For clarity, we have plotted the data from Table 5 in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Data packet sending count vs. direct trust value in scenario 1. Different colours in the figure represent different metrics: the blue line shows the data packet sending count for each node, and the red line represents the corresponding direct trust value. The sharp deviation at Node 10 highlights the malicious node in this scenario.

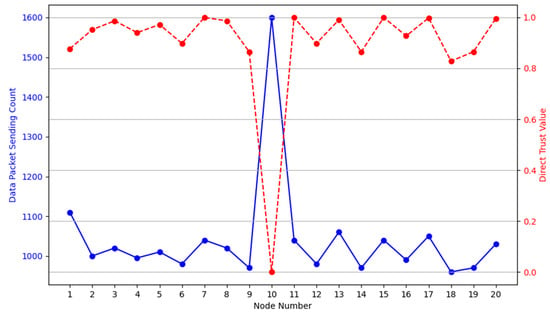

To demonstrate the model’s adaptability, we applied it to a second scenario with a higher baseline data rate:

In this scenario, the model similarly identified the outlier (Node 10 with a count of 1600), as shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Data packet sending count vs. direct trust value in scenario 2. Different colours in the figure represent different metrics: the blue line shows the data packet sending count for each node, and the red line represents the corresponding direct trust value. The sharp deviation at Node 10 highlights the malicious node in this scenario.

These results demonstrate ATAW-TM’s ability to function effectively across different network conditions without manual threshold reconfiguration.

4.2. Theoretical Analysis of the Hybrid Reciprocal and Entropy-Based Weighting Strategy

This subsection analyses the hybrid weighting strategy that dynamically assigns importance to the eight-trust metrics, enabling ATAW-TM to adapt to various network conditions and attack patterns.

4.2.1. Direct Trust Value Calculations

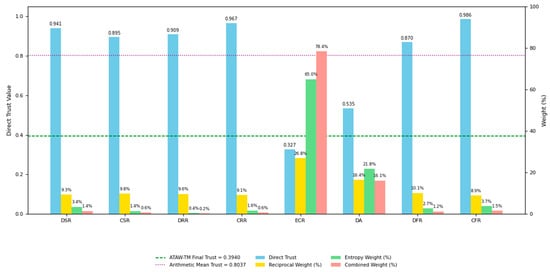

Assume we have calculated the direct trust values for eight trust metrics (DSR, CSR, DRR, CRR, ECR, DA, DFR, CFR) for a specific node from the perspective of node . The trust values are as follows:

where represent the eight trust metrics, respectively. The low ECR (0.3269) and moderate DA (0.5350) trust values suggest potential malicious activity in energy consumption and data accuracy. Other metrics’ trust values are very high.

4.2.2. Reciprocal Weighting Calculation

The reciprocal weighting factors are computed using Equation (11), where to prevent division by zero. The calculated reciprocal weights are as follows:

4.2.3. Entropy-Based Weight Calculation

To compute entropy weights, we first collect trust metric datasets from all neighbouring nodes. Assume node has five neighbours with the following trust values for each metric; among them, the volatility of ECR and DA is relatively high, as shown in bold:

We normalize these values using Equation (13) to form pseudo-probability distributions. The normalized entropy is calculated using Equation (14). The entropy weight factors are computed using Equation (15):

4.2.4. Combined Weight Calculation

The final weights are computed by combining reciprocal and entropy weights using Equation (16):

4.2.5. Combined Trust Value Calculation

The combined trust score is calculated using Equation (17):

Table 6.

Weighting analysis results.

Figure 12.

Direct trust value and weight comparison.

4.2.6. Analysis

The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the hybrid weighting strategy. The ECR metric, despite having the lowest direct trust value (0.3269), receives the highest final weight (0.784) due to the combined effect of reciprocal weighting (emphasizing low values) and entropy weighting (reflecting its importance in energy-constrained scenarios). The ECR metric and DA metric have higher entropy weighting due to their higher volatility. Although the direct trust values of most metrics are very high, the combined trust value (0.3940) calculated using our weighting method accurately reflects the node’s overall malicious behaviour. Compared to fixed-weight averaging (0.8037), ATAW-TM achieved a combined trust score of 0.3940, representing a 51% increase in detection sensitivity.

4.3. Theoretical Analysis of the Dynamically Adjusted Aging Factor

Finally, we analyse the aging factor mechanism, which enables the trust model to respond rapidly to malicious behaviour while allowing for slow, stable recovery. In this subsection, we set the parameters in the aging factor calculation equation (Equation (18)) to and . A parameter and sensitivity analysis will be conducted in the next subsection.

4.3.1. Trust Value Inputs

Assume that for a given node , the historical combined trust value from the previous evaluation period is , and the current combined trust value is . These values reflect a significant decline in trust, suggesting potential malicious activity during the current period.

4.3.2. Aging Factor Calculation

The aging factor is computed using Equation (18):

4.3.3. Updating the Local Trust Value

The local trust value is then updated using Equation (19):

To further illustrate the behaviour of the aging factor under different scenarios, we consider two additional scenarios:

Scenario 1: Trust Improvement

If and , then

Scenario 2: Stable Trust

If and , then

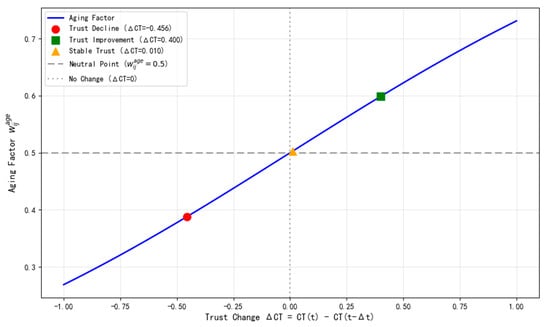

The results are summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Trust change vs. the aging factor.

We have plotted the relationship between the trust change and the aging factor in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Trust change vs. aging factor.

4.3.4. Parameter and Sensitivity

This subsection investigates the impact of the logistic aging parameters and and evaluates their sensitivity.

- Parameter interpretation:

- Slope parameter : A larger increases the steepness of the logistic curve. This leads to faster trust decay when becomes negative, improving attack responsiveness but making the model more sensitive to transient noise.

- Midpoint parameter : This value determines the tolerance centre. A positive shifts the logistic curve so that only sufficiently large negative deviations trigger rapid trust decay.

- Sensitivity study:

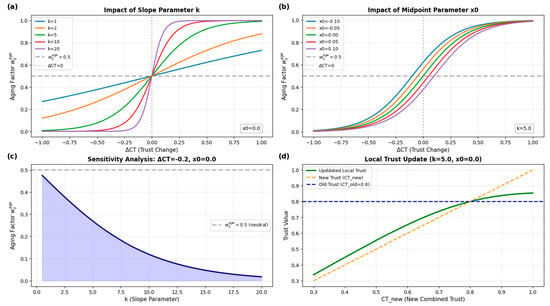

To further analyse the impact of the logistic aging parameters and justify the selection of , Figure 14 presents a detailed sensitivity study of the aging factor and its effect on the local trust update process.

Figure 14.

Sensitivity analysis of the logistic aging function under different slope parameters , midpoints , and trust update behaviours. (a) Impact of slope parameter : Larger makes the aging factor curve steeper and increases the sensitivity of the system to trust changes, while smaller produces smoother transitions. (b) Impact of midpoint parameter : Shifting moves the logistic curve horizontally, adjusting the tolerance range so that small fluctuations near can be either emphasized or suppressed. (c) Sensitivity analysis: When ΔCT is fixed (e.g., ), increasing leads to a monotonic decrease in the aging factor, revealing how controls the reaction strength to a given trust change. (d) Local trust update: The updated local trust reflects the weighted combination of historical trust and new trust.

Panel (a) shows that the slope parameter directly controls the steepness of the logistic curve. A small results in a smooth and gradual change in , making the system tolerant to small fluctuations in . As increases, the curve becomes sharper, allowing the model to react aggressively to deviations in trust behaviour. This capability is beneficial when rapid isolation of malicious nodes is required, but it may introduce false positives in traffic with high variability.

Panel (b) illustrates how the midpoint shifts the logistic response horizontally. A positive delays the decrease in , providing resilience against bursty but benign traffic patterns, whereas a negative increases the sensitivity of the trust decay mechanism. For instance, when ranges from to , the aging factor with decreases faster than that with . This parameter therefore allows the trust system to be tuned for different SDWSN deployments and levels of environmental noise.

Panel (c) quantitatively evaluates the sensitivity of with respect to under a representative trust decrease . As increases, drops sharply toward zero, demonstrating how steep logistic functions accelerate the suppression of trust values after anomalous behaviour is observed. This analysis supports selecting moderate values (e.g., ) to maintain a balance between responsiveness and robustness.

Panel (d) shows the resulting impact on the local trust update process. When and , the updated trust curve remains stable under small negative fluctuations but reacts more firmly when continuous negative trust evidence accumulates. This behaviour aligns with the design goal of penalizing persistent malicious behaviour while avoiding excessive punishment for normal variation. It also reflects the design goal of a quick response to malicious activity coupled with a slow, steady recovery.

Overall, Figure 14 demonstrates that the logistic aging mechanism provides tuneable flexibility. By appropriately selecting and , the proposed model can balance responsiveness to actual attacks and robustness to transient fluctuations, ensuring reliable operation in diverse SDWSN environments.

If the deployment environment is prone to transient fluctuation or bursty traffic, smaller values are advisable to avoid unnecessary trust oscillation. Conversely, if rapid identification of malicious nodes is critical, larger values help accelerate trust decay.

4.3.5. Dynamic Ageing Mechanism Analysis

In terms of robustness, the results demonstrate the effectiveness of the dynamically adjusted aging factor in balancing historical and current trust values. When trust declines significantly (e.g., due to malicious behaviour), the aging factor decreases, giving more weight to the current low trust value. Conversely, when trust improves, the aging factor increases, emphasizing historical trust. Importantly, this asymmetric aging factor also can mitigate false positives during transient disturbances by incorporating historical trust values into the final trust score. For example, in the Trust Decline scenario shown in Table 7, when trust drops from 0.850 to 0.394, the adjusted final local trust value becomes 0.570, which smooths the abrupt change compared to using only the current value. This mechanism enhances the model’s robustness in dynamic SDWSN environments.

In terms of detection sensitivity, this dynamically adjusted aging factor is a crucial defence against On–Off Attacks, where a malicious node switches between good and bad behaviour to build trust and then exploit it. ATAW-TM counters this with an asymmetric response:

- During the “Off” (malicious) phase, a sharp drop in current trust leads to a small aging factor, causing the local trust value to plummet rapidly for quick detection and isolation.

- During the “On” (normal) phase, recovery is intentionally slow. A larger aging factor prioritizes the node’s poor history, preventing it from quickly regaining trust after brief good behaviour.

This mechanism significantly raises the cost and reduces the effectiveness of on–off attacks, thereby mitigating the associated risk.

As discussed above, this dynamic aging mechanism achieves a balance between model robustness and detection sensitivity.

4.4. Computational Complexity Analysis

A key advantage of the proposed trust model is its low computational complexity, which makes it suitable for resource-constrained SDWSNs. The local trust computation for each node is based on lightweight operations, including counting forwarding events, calculating simple deviations, and performing scalar updates of trust values. For a node with neighbours, the complexity of local trust evaluation is , as each neighbour is processed once per trust update cycle.

The cooperation probability calculation also relies on basic arithmetic using pre-computed mean and deviation terms, avoiding expensive operations such as matrix computation or iterative training as required in learning-based approaches. Trust aggregation at the cluster head only involves summing or averaging trust values received from cluster members, resulting in complexity, where is the number of nodes in the cluster.

The overall computational cost of the full trust update process is therefore linear in the number of neighbour relationships in the network and does not depend on the network size beyond local connectivity. This lightweight design ensures that the model can operate efficiently on SDWSN sensor nodes with limited CPU, memory, and energy resources, while maintaining responsiveness to DoS-related misbehaviour.

5. Discussion

The ATAW-TM model proposed above was designed specifically for SDWSNs. The model addresses key limitations of existing trust models, particularly those related to threshold configurations, weight allocation, and the loss of trust information in the presence of DoS attacks. ATAW-TM enhances the detection of DoS attacks and supports dynamic, self-adjusting trust evaluations by adopting a layered architecture with components at the node, CH, and controller levels. While the sensor nodes in the node layer evaluate their trust locally by assessing the link quality, extracting trust evidence, and calculating direct trust values, in the CH layer, these values are processed to calculate aggregated trust scores and to identify and isolate malicious nodes. IN the controller layer, the process of global trust aggregation isolates malicious nodes by adjusting flow rules.

The core principle of ATAW-TM is adaptability in response to changing node network behaviour; the depictable trust evaluation mechanism removes the need for manual threshold configuration, through outlier detection and Bayesian inference. The model automatically computes trust values and assigns weights to various trust metrics using a hybrid reciprocal and entropy-based weighting strategy. This ensures that the model can dynamically adjust its focus based on the prevailing network conditions, making it highly adaptable to different attack types. Additionally, the incorporation of a logistic function-based aging factor balances the influence of historical and current trust valueS, allowing for more accurate evaluations of node behaviour over time. The model features a trust information retrieval mechanism as well to facilitate rapid recovery when trust information is lost, ensuring the resilience and stability of the network. ATAW-TM improves reliability in dynamic SDWSN environments by integrating link quality checks and trust information retrieval mechanisms, ensuring robustness against intermittent connectivity.

5.1. Comparison with Other Models

We propose a resilient trust model for SDWSNs, designed to effectively identify various types of DoS attacks. Compared to the previous trust models designed for SDWSNs [10,12,13,33], the proposed model has the following advantages.

First, our trust model considers and addresses the issue of wireless link qualities between sensor nodes being affected by the environment, while others did not consider link qualities at all. Moreover, our trust model is comprehensively designed to account for multiple types of DoS attacks, whereas other models typically consider only a subset of these attacks.

Second, our trust model does not use thresholds for evaluating packet transmission behaviour, eliminating the need for network administrators to configure thresholds, thus making it easily applicable to various WSNs. Previous models such as the ones described in [10,12] used threshold-based algorithms, which had issues with threshold configuration. The model proposed in [13] did not use threshold-based algorithms but considered using a complex IDS module, whereas our model is more lightweight.

Third, in our trust model, the weights of various trust metrics are dynamically and automatically assigned based on their values through an algorithm when calculating the combined trust value. This prevents a malicious node’s good performance in one aspect from masking its malicious behaviour in another aspect. In previous trust models [12,33], researchers left the task of assigning weights to users, which raised a significant obstacle standing in the way of the widespread application of trust models. In [10], fixed weights were used for the metrics of the data packet forwarding rate and control packet forwarding rate, resulting in poor flexibility and accuracy. The model proposed in [13] did not involve this weight assignment issue but considered using a complex IDS module.

Furthermore, our trust model uses a dynamically adjusted aging factor in the iterative update process of historical and current trust values, effectively balancing historical and current trust values. The models described in [10,13] did not consider historical trust values, while the model introduced in [12] considered historical trust values but used a fixed aging factor, resulting in poor flexibility and accuracy.

Additionally, we designed a trust information retrieval mechanism that allows for the quick retrieval of trust information for sensor nodes and cluster head nodes after trust information is lost, enabling rapid recovery of the trust system. Previous models did not consider the issue of trust information loss.

Finally, for ATAW-TM, local trust computation yields a per-node time complexity of . Cluster head aggregation incurs operations for a cluster of size . The communication overhead is bytes per reporting interval due to 1-byte trust compression. ETMRM and HTM exhibit similar per-node computational costs. Compared to ETMRM and HTM, ATAW-TM introduces two additional steps, namely Gaussian collaboration and entropy weighting, while still preserving linear time complexity. Moreover, the constant factor related to exponential operations can be reduced using lookup table methods.

5.2. Limitations and Directions for Further Research

While the theoretical analysis of the ATAW-TM trust model provides insights into its practical application for evaluating node trustworthiness in SDWSNs, a major limitation of this work is that the ATAW-TM has not yet been implemented or evaluated experimentally. This limitation will be addressed in our future work, including the implementation and evaluate of ATAW-TM in real-world scenarios and conducting an in-depth analysis of its performance. The first step is to develop a prototype using the SDN-WISE platform and the Contiki operating system within the Cooja simulation environment. The second step will involve simulating various (14) attack scenarios to test the effectiveness of the proposed trust model. Following this, we will evaluate the model using performance metrics such as detection accuracy, false positive/negative rates, trust convergence speed, communication overhead, and energy efficiency. A rigorous analysis will be conducted through quantitative simulation experiments.

Furthermore, we will explore the integration of the ATAW-TM trust model with SDWSN routing protocols to improve their efficiency and expedite the network’s response to DoS attacks, ensuring stable operations even during malicious disruptions.

Additionally, future work will explore controller redundancy and failover strategies to complement ATAW-TM’s trust retrieval mechanism.

Although Gaussian modelling was selected based on prior studies demonstrating its suitability for large-scale WSN traffic patterns, many WSN applications generate bursty or event-driven traffic that may follow Poisson or heavy-tailed distributions [47,48,49]. Our future work will investigate these alternative distributions to enhance adaptability in diverse environments. We also acknowledge that Gaussian modelling may introduce false positives under highly bursty workloads, where mean–standard-deviation-based outlier detection can misclassify legitimate traffic spikes as malicious. To mitigate this risk, non-parametric outlier detection techniques will be explored in future work to relax the normality assumption and better accommodate heavy-tailed or event-driven traffic patterns.

In addition, integrating adaptive trust update strategies that adjust decay rates or penalty weights based on the detected anomaly type represents a valuable direction for future work. Such adaptive mechanisms could incorporate behaviour signatures or temporal characteristics to further improve detection accuracy and reduce false positives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.W., M.L.Y. and K.P.; methodology, L.W., M.L.Y. and K.P.; validation, M.L.Y.; formal analysis, L.W.; investigation, L.W.; resources, M.L.Y.; data curation, L.W.; writing—original draft preparation, L.W., M.L.Y. and K.P.; writing—review and editing, L.W., M.L.Y. and K.P.; visualization, L.W.; supervision, M.L.Y. and K.P.; project administration, M.L.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the text.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Akyildiz, I.F.; Su, W.; Sankarasubramaniam, Y.; Cayirci, E. Wireless sensor networks: A survey. Comput. Netw. 2002, 38, 393–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]