Abstract

Analyzing the evolution of trajectory topics is fundamental to understanding urban mobility and human activity. Existing methods, however, often struggle to capture complex spatio-temporal semantics and are constrained by fixed time windows, which limits multi-scale temporal analysis. This paper presents a novel method to model the dynamic topics of trajectories to address these limitations. The proposed method combines a domain-specific trajectory embedding strategy, a flexible dynamic topic modeling pipeline, and an interactive visualization system to address these limitations. Firstly, the method introduces a novel embedding method that uses a retrained RoBERTa model with a word-level tokenizer on Morton-coded trajectories to effectively learn spatial context and sequential patterns. Secondly, a BERTopic-based approach is employed for topic modeling, featuring an adjustable time window that allows for flexible analysis of topic dynamics across different temporal scales without model retraining. Furthermore, an interactive visualization system with coordinated spatio-temporal views translates abstract model outputs into an intuitive format, enabling direct exploration of evolving trajectory topics. Experiments on a large-scale taxi trajectory dataset demonstrate the proposed method’s effectiveness in identifying coherent and meaningful patterns of dynamic trajectory topics.

1. Introduction

Trajectory data hold rich information about spatio-temporal behavior [1]. Analyzing trajectory data is fundamental to understanding urban mobility and human activity [2]. The underlying patterns, or topics, within trajectory data are not static. Trajectory topics often correlate with temporal cycles. For instance, commute flows differ significantly between weekdays and non-workdays. An understanding of dynamic changes is essential to applications in traffic management, public service optimization, and urban planning. A clear need, therefore, exists for methods to effectively model and interpret trajectory topic evolution.

Modeling trajectories to effectively capture features is a fundamental step for analyzing dynamic topics. Existing modeling approaches often use representation learning to generate high-dimensional embeddings for trajectory sequences. RNN-based methods [3] employ a recurrent structure to process sequences. However, for long trajectories, the recurrent structure struggles to propagate information from the start to the end of a sequence [4,5,6,7]. Transformer-based methods [8] offer an alternative but require supervised training for specific tasks. Consequently, the resulting trajectory representations become task-dependent [9,10,11,12,13]. A new trajectory embedding strategy is required to produce effective semantic representations that preserve spatial context.

Many existing topic modeling methods lack flexibility for analyzing topic dynamics across different temporal scales. These methods often rely on fixed time windows for analysis. An analysis based on fixed windows limits the scope of inquiry. A predefined interval may be too coarse to capture short-term events or too fine to reveal long-term trends. Such limitations prevent a comprehensive, multi-scale understanding of movement dynamics. The dynamic topic model (DTM) [14], a dynamic extension of Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) [15], exemplifies these challenges. While DTM allows topics to evolve over time, the model requires a fixed number of time slices to be set before analysis. This requirement reduces flexibility, especially for temporally uneven data. Any adjustment to the modeling goal in DTM requires a full retraining of the model with a new time slice configuration. Such retraining is computationally expensive. DTM also requires pre-specifying the number of topics and offers limited semantic modeling capabilities. A clear need, therefore, exists for a more flexible topic modeling approach. Such an approach should permit dynamic adjustment of the temporal scope to match different behavioral patterns and analytical goals.

Visual analytics systems use interactive interfaces to help users explore and interpret dynamic trajectory topics [16]. Existing visualization tools for trajectory analysis often focus on presenting statistical information [17,18,19]. A key limitation is the lack of support for exploring the various components of a topic to understand its underlying meaning. Effective visual analysis of trajectory topics thus requires intuitive components designed for interactively exploring multi-level semantics.

To address these challenges, this paper presents a new method for constructing dynamic topic models from trajectory data. The proposed method consists of three main components. First, the method introduces a new embedding strategy to capture complex trajectory semantics while preserving spatial context. This strategy uses a modified RoBERTa model and a word-level tokenizer to generate context-aware embeddings from Morton-coded trajectories. Second, the method employs BERTopic [20], a data-driven neural topic model, for a more flexible modeling of dynamic topics. BERTopic clusters the trajectory embeddings and then generates topic representations using a class-based TF-IDF procedure. Then, a visualization system centered on trajectory topic words and features is developed for the interactive exploration of dynamic movement topics. The system translates abstract model outputs into an intuitive interface, enabling the direct exploration and interpretation of evolving trajectory topics. The proposed method applies established text processing methods to the challenge of topic modeling for unstructured spatio-temporal data. The main contributions of this work are as follows:

(1) A domain-specific trajectory embedding method to effectively capture both spatial context and sequential patterns. This addresses the limitations of information decay in RNN-based approaches and task-dependent representations in standard Transformer models.

(2) A flexible dynamic topic modeling method using an adjustable time window to support multi-scale temporal analysis. This overcomes the constraint of fixed time slices found in traditional dynamic topic models.

(3) An interactive visualization system to translate abstract model outputs into an intuitive interface for the direct exploration and interpretation of evolving trajectory topics.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: We introduce related work on modeling dynamic topics of trajectories in Section 2. Then, we give the detail of the proposed method for dynamic modeling trajectory topics in Section 3. Extensive experiments are performed in Section 4. Next, we present a discussion and mention future work in Section 5. Finally, we conclude this paper in Section 6.

2. Related Work

In this section, we briefly introduce related works. Specifically, we introduce works on the dynamic topics of trajectories first, and then, we introduce works of modeling trajectories. Finally, we detail related work about trajectory visualization.

Methods for modeling dynamic trajectory topics are generally classified into static and dynamic approaches. Static topic models such as LDA [15], NMF [21], and BTM [22] can identify global movement patterns across an entire dataset [23,24,25,26,27,28]. A primary limitation of static models is the inability to capture temporal topic dynamics. Dynamic extensions like Dynamic NMF [29] and dynamic topic models (DTMs) [14] were developed to explicitly model topic evolution. However, a common limitation is the requirement to fix the number and duration of time slices prior to model training. Furthermore, traditional topic models including LDA and DTMs employ a bag-of-words assumption. This assumption ignores the sequential order of trajectory points, preventing the capture of complex spatial movement semantics. BERTopic [20] presents a modern deep learning paradigm for this problem. The method adapts text modeling techniques to capture both sequential patterns and spatial context in trajectory data. Moreover, BERTopic enhances analytical flexibility through a modeling process that supports adjustable time windows. Unlike traditional DTMs, which require computationally expensive retraining whenever time slices are altered, this approach allows for dynamic window adjustments during the inference phase without retraining, thereby offering superior computational efficiency for multi-scale analysis. Representation learning is a key component within BERTopic for capturing sequence features. The following section details relevant methods for trajectory sequence modeling.

Effective trajectory modeling forms the basis for dynamic topic analysis. Existing methods for learning trajectory representations [30] are generally classified into two categories: RNN-based [3] and Transformer-based [8] approaches. RNN-based methods [4,5,6,7] use a recurrent structure to process sequential information. For long trajectory sequences, however, this structure struggles to propagate information from the start to the end of a sequence, resulting in information decay. Standard Transformer-based methods [9,10,11,12,13] typically require supervised training on downstream tasks. The resulting trajectory representations are, therefore, task-specific. Consequently, applying these methods to trajectory topic modeling introduces the risks of information decay and task-dependent feature representations. To address these limitations, the proposed method leverages RoBERTa [31]. The approach combines RoBERTa with structural encoding and a word-level tokenizer [32] to learn contextual trajectory embeddings while preserving the semantic independence of individual locations.

Converting abstract trajectory topics into interpretable insights depends on effective visualization. Visual analytics is a common approach for exploring features from trajectory data [17,18,19]. Many existing methods use visual components to analyze traffic trajectories. For instance, He et al. [33] developed a visual filter, a form of coordination between views, to explore the spatio-temporal evolution of topics. Gao et al. [34] employed visualization to guide the trajectory clustering process. However, a comprehensive interpretation of dynamic topics requires integrating a topic’s multi-level semantics, from individual topic words and trajectory segments to the overall theme. Existing approaches often lack this deep integration needed to explain dynamic topic behavior. The proposed visualization system is designed based on the core attributes of trajectories. The approach presents trajectory topics by centering on two semantic levels: topic words and trajectory segments. A system of coordinated views displays topic features across different time slices. This design yields clear visual representations of topic characteristics and allows analysts to explore dynamic topic evolution from macro- to micro-scales.

3. Methodology

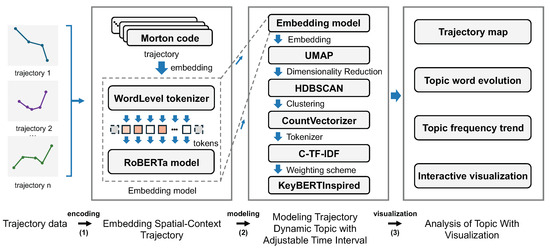

The primary research problem is to capture dynamic semantics from unstructured trajectory data. The main goal is to build a flexible framework for analyzing topic evolution. Based on this goal, we introduce the details of our dynamic topic modeling method for trajectory data in this section. Figure 1 illustrates the pipeline of the proposed method. There are three steps to modeling dynamic topics in trajectory data and analyzing the dynamic topics in trajectory data with visualization. Basically, after generating trajectory embeddings with a domain-specific embedding strategy, we incorporate the adjustable topic modeling method to generate trajectory dynamic topics. Then, we develop a visualization system to interactively analyze the details of the dynamic topics of the trajectory.

Figure 1.

The pipeline of proposed dynamic topic modeling method for trajectory data: (1) trajectory embedding with spatial-context feature, (2) dynamic trajectory topic modeling with adjustable time interval, and (3) visualization for dynamic topic modeling.

3.1. Trajectory Embedding with Spatial-Context Feature

3.1.1. Morton Encoding for Spatial Discretization

The trajectory is composed of a series of trajectory coordinates in sequential order, and it is necessary to simplify the trajectory data structure. The trajectory coordinates are encoded by Morton codes [35]. The following formulation is the definition of the Z-order curve of Morton codes:

where x and y are the longitude and latitude coordinates in binary format, and represent the bit at position i, and l is used to quantify the number of digits of the coordinates. Morton encoding simplifies the structure of trajectory data because its dimensions are encoded from a multi-dimensional space to a single-dimensional space. Basically, Morton encoding adapts the Z-curve to fill the space, which keeps the spatial information. The length of a Morton code remains 12 bits with an accuracy of 10 m. Additionally, Morton encoding provides the benefit of keeping the related spatial feature in nearby GPS coordinates. In detail, near trajectory GPS coordinates are encoded into the near digital space, which improves the calculation efficiency. We convert all trajectory coordinates with the expression of longitude and latitude into the string word with Morton encoding, establishing the bridge from trajectory sequence to the following RoBERTa method.

3.1.2. Tokenizer and Vocabulary Design

The tokenizer converts the trajectory sequence into a discrete signal sequence. The WordLevel tokenizer is suitable in the task of trajectory embedding because the WordLevel tokenizer preserves the integrity of Morton identifiers and domain terms. Additionally, The WordLevel tokenizer avoids the semantic damage caused by sub-word splitting and preserves the spatial encoding granularity.

The training process of WordLevel tokenizer is present in Algorithm 1. Let the trajectory be represented as a sequence , where each denotes a Morton code. Algorithm 1 aims to construct a WordLevel tokenizer that satisfies

where the maximum sequence length is represented as . The training pipeline includes three phases. Firstly, we construct the vocabulary by combining the special tokens with the unique Morton codes tokens extracted from all trajectories. Then, with the configurations of whitespace splitting at Morton code boundaries and the length limitation , the mapping function is constructed to initialize the WordLevel tokenizer .

| Algorithm 1 WordLevel tokenizer training. |

| Require: Trajectory set , Max trajectory length , Vocab size Ensure: Tokenizer

|

The WordLevel tokenizer has better adaptability to the trajectory. Compared with the BPE tokenizer, the WordLevel tokenizer generates the complete token from the trajectory sequence. The complete token of Morton codes maintains the local spatial pattern. The object with minimal byte character given by the BPE tokenizer causes difficulties in learning the trajectory pattern. In the experimental section, we compare the modeling performance of two topic modeling approaches. These two topic modeling approaches are respectively equipped with a BPE tokenizer and a word-level tokenizer.

3.1.3. Domain-Specific RoBERTa Training

RoBERTa is a Transformer-based language model and presents an optimized iteration of BERT. RoBERTa benefits from the self-attention mechanism and generates a contextualized representation of words. To capture the spatial context of a trajectory, we train RoBERTa with the WordLevel tokenizer. We use a trajectory dataset to train RoBERTa and aggregate the outputs from RoBERTa by mean pooling to generate trajectory embeddings. Unlike general-purpose models, this retraining strategy allows the model to learn domain-specific features. The retrained RoBERTa model adapts the vocabulary distribution of trajectory text.

The RoBERTa model is trained with the Masked Language Modeling (MLM) strategy. When training the RoBERTa model, we randomly mask a trajectory coordinate with a special token [MASK] and make the RoBERTa model predict the masked trajectory coordinate. The MLM training strategy makes the RoBERTa model learn the sequence pattern and does not need any notation. Additionally, the task of mask prediction forces the model explore the context of trajectory and strengthens the understanding of the trajectory sequence. In addition, the random mask acts as the trajectory noise during the training process with the MLM strategy, increasing the robustness of model encoding. For a trajectory token , the MLM loss is defined as

where M is the set of masked token indices, is the correct trajectory token, and denotes the output vector corresponding to the masked position.

RoBERTa captures the spatial relationship between nearby trajectory coordinates and learns the semantics from the whole trajectory, which offers trajectory embeddings with rich semantic information. Additionally, the position encoding of RoBERTa can capture the order of trajectory coordinates, complementing the spatial proximity of Morton codes. In the Experiments Section, the topic modeling performance of two kinds of RoBERTa models, a RoBERTa model trained with trajectory data and a RoBERTa model fine-tuned with trajectory data, is compared.

3.2. Adjustable Dynamical Topic Modeling for Trajectory Data

To overcome the limitations of the bag-of-words model and fixed time windows, we construct a flexible method for the dynamic topic modeling of trajectories based on BERTopic. During the inference phase, the capability for dynamic time window adjustment expands the boundaries of trajectory topic modeling. The core phases of the adjustable dynamic topic modeling method include embedding, dimensionality reduction, clustering, and topic representation. Let represent the document collection of a trajectory. Document d could be split into the set of trajectory sequences , where is the sentence count of document d. We detail the adjustable dynamic topic modeling method in the following content.

3.2.1. UMAP Dimensionality Reduction

Operating directly on raw trajectory embeddings from RoBERTa for modeling topics encounters dimensionality-induced obstacles. Basically, the high-dimensional embedding space characterizing trajectory data fundamentally hinders direct topic modeling by introducing semantic sparsity and computational intractability. UMAP achieves non-linear dimensionality reduction based on manifold learning, enabling tasks for dimension reduction for trajectory embeddings. We could divide UMAP into two main steps. Basically, UMAP learns the manifold structure in high-dimensional data spaces and constructs its low-dimensional representation. As a result, the inherent manifold learning preserves the local and global patterns of the trajectory embeddings.

3.2.2. HDBSCAN Density-Based Clustering

HDBSCAN performs hierarchical clustering on trajectory embeddings, yielding clusters of similar trajectory embeddings [36]. Let denote a trajectory embedding generated from UMAP reduction. HDBSCAN processes trajectory embedding and preserves the principal topological structures within the embedding space. HDBSCAN generates the cluster labels , where denotes noise. HDBSCAN automatically determines the optimal number of clusters while avoiding parameter sensitivity issues. This reveals the core advantage of using HDBSCAN for trajectory topic clustering: it establishes membership relationships between trajectory-embedded documents and their corresponding clusters. Additionally, HDBSCAN detects semantically coherent trajectory topics by identifying core points to locate high-density regions and marking low-density areas as noise. HDBSCAN identifies arbitrarily shaped trajectory embeddings using density-reachable principles, effectively adapting to dynamically changing movement patterns.

3.2.3. CountVectorizer Frequency Quantization

CountVectorizer is an essential step in trajectory topic calculation. It links the trajectory clustering results with keywords. Given the trajectory document and vocabulary . CountVectorizer constructs a sparse matrix , where denotes the frequency of word in document .

3.2.4. c-TF-IDF Topic Representation

c-TF-IDF calculates the weight of trajectory words at the cluster level. c-TF-IDF takes as input the clusters from the output of HDBSCAN, where each cluster is a document collection. Then, term frequency and inverse document frequency for the trajectory words are computed, yielding the importance score for word in the cluster:

c-TF-IDF achieves semantic consistency and enhances discriminability through . For trajectory embeddings, the method applies normalization to eliminate the effect of length variation, enabling fair cross-topic comparisons. Additionally, c-TF-IDF employs to suppress high-frequency geographical noise.

3.2.5. KeyBERTInspired Contextual Topic Representation

KeyBERTInspired operates as an essential plug-in and a re-ranker for c-TF-IDF results to enhance the consistency of trajectory semantics. It ensures that the selected topic words closely represent the cluster centroid. Let denote the representation documents of the t-th topic and be candidate keywords, where is the -th keyword in the t-th topic. KeyBERTInspired conducts the semantic ranking of candidate keywords by computing spatial similarity between representative documents and keyword embeddings. Let denote the encoder from RoBERTa; the centroid of the trajectory topic is calculated with . Subsequently, compute the cosine similarity between trajectory embeddings and centroids with

where . KeyBERTInspired selects keywords by maximizing the similarity scores , enforcing directional alignment between trajectory words and the trajectory topic. The collaboration between KeyBERTInspired and c-TF-IDF improves trajectory topic modeling while maintaining computational efficiency and semantic precision.

3.2.6. Dynamic Time-Window Parameterization

Our topic modeling method outperforms traditional approaches by dynamically adjusting the temporal range for analysis, optimizing time windows for different behavioral patterns. Time window is defined as

where represents a trajectory document, is its associated time, denotes the size of the time window, and is the start time of the window. This formula defines a time window containing all events points meeting specific temporal conditions. Specifically, each must be included in , where denotes the start time and the interval duration. Adjustable time windows enable multi-scale temporal analysis, balancing short-term events with long-term trends through flexible scaling.

3.3. Interactive Visualization for Trajectory Dynamic Topic

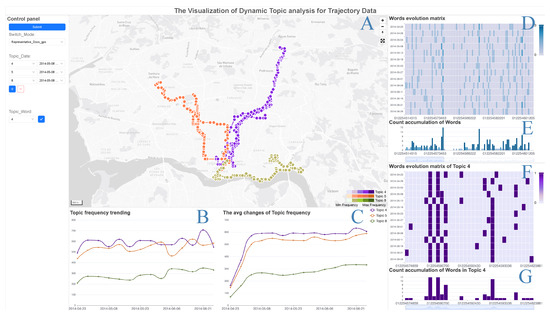

To provide an intuitive dynamic analysis of trajectory topics, we develop an interactive visualization system. Figure 2 illustrates the user interface of the proposed system, which presents the dynamics of trajectory topics in both spatial and temporal dimensions. Specifically, the system consists of three main components: a trajectory topic map, a topic frequency trend view, and a topic word evolution view. We describe each component in detail below.

Figure 2.

The overview of the proposed interactive visualization system. This system presents the visualization of topic analysis for trajectory data with three visual parts: trajectory topic map (component (A)), topic frequency trend (components (B,C)), and word evolution matrix (components (D–G)).

3.3.1. Trajectory Topic Map

The interactive trajectory map view is designed to support the geospatial exploration and analysis of the semantic information embedded in trajectory topics. As illustrated in Figure 2A, this component visualizes the spatial distribution of trajectory topics. Specifically, after a user selects topics from a target time interval using the control panel on the left of the map view, the map view renders the corresponding GPS sequences onto the basemap. The GPS sequences represent the most frequent trajectories for the selected time interval and topic. Each sequence is rendered as a colored line, and the line color identifies the trajectory topic. To avoid visual clutter, our design follows Tufte’s principle of maximizing the data–ink ratio. Consequently, we use a grayscale basemap to ensure that the colored trajectories stand out. For visual representation, each trajectory topic is assigned a distinct color, creating a clear visual hierarchy. Furthermore, the topic frequency, a quantitative value, is mapped to a sequential color scale within the same hue, where higher topic frequency corresponds to a darker and more saturated color. The map supports standard interactions such as panning, zooming, and filtering to facilitate interactive exploration.

3.3.2. Topic Frequency Trend

To complement the spatial analysis of trajectory topics, we designed a topic frequency trend chart for revealing the temporal dynamics of different trajectory topics. This chart serves as a supplement to the map view, providing users with a linked component for coordinated spatial temporal analysis. To support the goals of identifying periodic patterns and comparing temporal dynamics, the chart’s visual encoding is organized through the time dimension. Specifically, we compute the frequency of each topic over time to generate multiple time-series plots for topic frequency. Figure 2B displays the topic frequency trend as a line chart, where the x-axis represents time and the y-axis represents the topic frequency. Furthermore, to better illustrate the trend of frequency changes over time, we compute and plot the average changes in topic frequency, as shown in Figure 2C. To ensure consistency across views, the color encoding is kept consistent with that of the map view. Furthermore, to address the visual challenges of displaying multiple trend lines, we provide interactive features such as highlighting on mouse hover and displaying details on demand, which helps users focus on information of interest.

3.3.3. Topic Word Evolution

To refine the exploration granularity from the topic level to the individual topic word level, a topic word evolution view is proposed. The view supports analysis of the evolutionary trends of topic words over time. Specifically, the component is a composite view consisting of a temporal heatmap and an aggregated bar chart. These two coordinated views reveal both the overall dynamics and the detailed composition of topic word frequencies. Figure 2D,E present the evolution for all topic words, while Figure 2F,G illustrate the evolution for a single topic word. As shown in Figure 2D,F, the temporal frequency heatmap displays the frequency of each word within every time interval at fine granularity. Frequency values are encoded using a color channel. The heatmap is intended for identifying periodic and trend-based patterns and discerning co-occurrence relationships among trajectory words. Figure 2E,G show the aggregated bar chart. The x-axis of the aggregated bar chart in Figure 2E is aligned with the x-axis of the heatmap in Figure 2D, with both axes representing topic words. The length of each bar in the aggregated bar chart encodes the total frequency of a topic word summed across all time intervals. The aggregated bar chart provides an overview of the frequency intensity for each topic word. The temporal heatmap and the aggregated bar chart are tightly coupled through strict alignment and a shared x-axis. Such coupling enables efficient visual correlation analysis. Additionally, the two views implement a classic focus and context design. The temporal frequency heatmap serves as the high-resolution focus view, displaying details of interest, while the underlying aggregated bar chart acts as a summarized context view. A focus and context design allows for a balanced exploration between microscopic details and macroscopic trends.

4. Experiments

4.1. Dataset and Setup

The experiments were conducted on a server with an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU. The software environment included Python 3.10 and PyTorch 2.6. The dataset in this experiment includes Porto taxi trajectories [37]. This dataset contains 1,704,770 data records and records the taxi trajectory with GPS coordinates over one year from 1 July 2013 to 30 June 2014. Each record of the dataset comprises trip ID, a list of GPS coordinates, timestamp, and other types of attribute information. We employed the Porto dataset for the RoBERTa model with different training strategies, with training from scratch and fine-tuning. Basically, when training RoBERTa from scratch, we allocated 80% of the dataset records to training or fine-tuning the RoBERTa model, dividing this portion into 70% training, 15% validation, and 15% test sets. The remaining 20% served for trajectory dynamic topic modeling. For RoBERTa fine-tuning, we kept the same data partitioning strategy except for the training partition. The training partition was adapted to fine-tuning the RoBERTa model, while the validation and test partitions remained unchanged. We kept the same hyperparameters for the two training strategies.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

To evaluate the quality of trajectory topics, we employed multiple metrics, including coherence, diversity, stability, and distinctness. These metrics quantify the performance of dynamic topic modeling under various combination of components.

Topic coherence quantifies the interpretability of a trajectory topic [38]. For comparing the coherence of topics, we employed pointwise mutual information (PMI) for each term in a topic [39], which is defined as follows:

The formulation presents the PMI of two words and from the same document. PMI quantifies term association within topics, providing an intuitive metric to evaluate BERTopic models. Topic coherence is calculated as follows:

Topic diversity is the proportion of distinct words among the first N words of a topic. We evaluated the diversity of the top 10 words of the topic, and the topic diversity is defined as follows:

where is the keywords for topic .

Topic stability is adapted to measuring the degree of change in topic strength within a time window. Specifically, topic stability is represented as the average of the variance of topic frequencies across all time windows, and finally, the normalized stability score is calculated. Let denote the frequency sequence of topic k and p denote the window size. The topic stability of topic k in the i-th window is defined as , where is the mean value in window i. The average variance of all windows is denoted by . The normalized stability score of topic k is calculated as , where represents the average standard deviation across all windows. The global topic stability can be calculated with the following formula:

4.3. Results and Analysis

In this part, we evaluate the performance of trajectory topic modeling on the Porto dataset. Specifically, we first compare the topic modeling performance of the proposed method with traditional topic modeling methods. Then, we conduct ablation studies to determine how different parts of the model contribute to the proposed model. We quantify the influence of different components on the performance of the proposed method. Finally, we analyze the effects of different hyperparameters settings on the performance of the proposed method.

4.3.1. Ablation Studies with Different Components

To validate the performance contribution of components including the trajectory embedding model and the representation model from adjustable dynamic topic modeling, we compare the performance of dynamic topic modeling with two training strategies, two tokenizers, and two representation models. The performance metrics include topic coherence, topic diversity, topic stability, and the number of topics. The performance results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Execution time comparison of modeling dynamic topics of trajectories with different training strategies, tokenizers, and representation models.

Topic coherence achieves the peak point at 3.546 for the component configuration of retraining strategy, WordLevel tokenizer, and KeyBERTInspired representation model. This demonstrates that the model captures adjacent movement patterns using domain-specific retraining and word-level tokenization. Notably, retraining from scratch yields significantly higher topic coherence metrics than fine-tuning the pretrained model. Specifically, with identical tokenizer and representation model settings, the retraining strategy achieves 40.16% higher average coherence scores than fine-tuning pretrained models. These results are competitive compared with traditional static models like LDA reported in previous studies [24].

The improvement suggest that retraining captures adjacent movement patterns of trajectories more effectively than pretraining.

Topic diversity exceeds 0.9 across all training component configurations. Our method uses a RoBERTa encoder and BERTopic for trajectory topic modeling. The high topic diversity scores demonstrate its effective topic separation. Our method uses a retraining strategy and a word-level tokenizer for dynamic topic modeling. However, it shows slightly lower topic diversity than other method combinations. This trade-off is acceptable. Our method produces finer-grained topics with the KeyBERTInspired representation model and achieves the best coherence scores.

Topic stability consistently exceeds 0.982, as shown in Table 1. This metric validates the temporal stability of our trajectory topics across time slices. Additionally, the model achieves the highest stability with the retraining strategy, WordLevel tokenizer, and KeyBERTInspired components. Moreover, the retraining strategy slightly improves topic stability, and the type of tokenizer has minimal impact.

The number of topics shows significant variation. As shown in Table 1, the model generates 25.2 topics for trajectory modeling with the retraining, WordLevel tokenizer, and KeyBERTInspired components. This is 740% higher than the fine-tuning training strategy configuration with three topics. The Porto dataset contains complex movement semantics. A small number of trajectory topics cannot fully cover all movement patterns. The difference in topic model quantity directly reflects our model’s effectiveness in capturing trajectory topics. Additionally, with only the retraining strategy but keeping BPE tokenization, the number of topics is small. This shows that retraining alone is insufficient and requires combining with the WordLevel tokenizer.

4.3.2. Hyperparameter Optimization for Components

To quantify the impact of different hyperparameters on the BERTopic model, this section compares diversity and stability results under various hyperparameter settings.

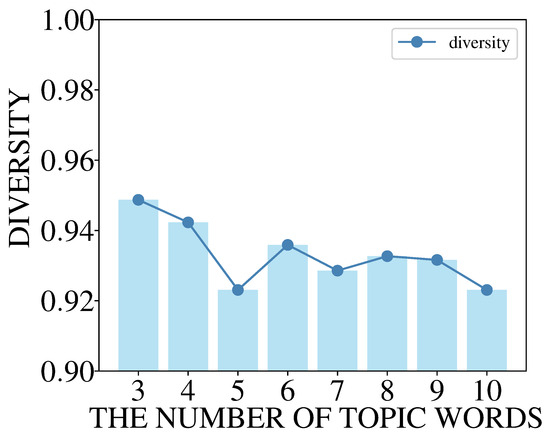

The first experiment evaluates the effect of the number of topic words on topic diversity. Topic diversity measures the uniqueness across different topics and is calculated as the proportion of unique words among the top N words of all topics. The experiment computes topic diversity scores for a topic word count ranging from 3 to 10.

Figure 3 illustrates the topic diversity scores for different numbers of topic words, revealing a slight downward trend as the word count increases. The diversity score reaches a peak of approximately 0.949 when using the top three words. As the number of included words increases to 10, the diversity score decreases to 0.923. The relationship is not strictly linear. The diversity score exhibits minor fluctuations. For example, when the word count increases from five to six, the score rises from 0.923 to 0.936. However, the overall trend remains downward, suggesting that adding more topic words slightly reduces the collective diversity of the topic set. The highest-probability words in a topic are generally highly unique and representative, yielding a higher diversity value. In contrast, lower ranked words are often common or background terms prevalent across multiple topics. The inclusion of such common words reduces the proportion of unique terms among topics, thus causing a decrease in the diversity score.

Figure 3.

Topic diversity trend with increasing number of topic words.

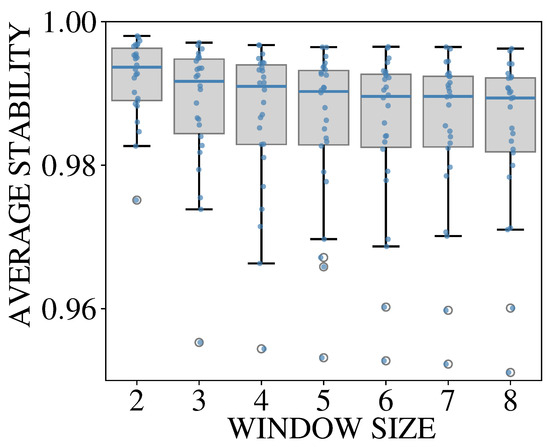

Topic stability measures the degree of topic change over a specified time window. This experiment evaluates the differences in topic stability across various time-window lengths. Figure 4 presents a box plot of the topic stability score distribution for time windows ranging from 2 to 8. Figure 4 indicates a significant impact of window length on topic stability. The general trend shows a decrease in the median topic stability as the time-window size increases. For example, a window length of 2 yields a median stability score of 0.9937, the highest value among all tested settings. When the window length increases to 8, the median drops to 0.9894. This downward trend is particularly pronounced when the window length increases from 2 to 4, after which the decline becomes more gradual.

Figure 4.

The box plot of topic stability with increasing window size.

In addition to the central tendency, data dispersion also increases with window length. For a window length of 2, the distribution of stability scores is the most concentrated, with an Interquartile Range (IQR) of 0.0073. This low IQR value indicates the highest result consistency. As the window length increases, data dispersion also increases. For instance, at a window length of 4, the IQR grows to 0.0111, and the minimum observed value drops from 0.9751 to 0.9544, for window lengths of 2 and 4, respectively. A larger window size, therefore, leads to greater result fluctuation and lower stability. In summary, smaller time windows compare adjacent time slices. The content and topic distributions of adjacent slices have naturally higher similarity, thus yielding higher stability scores. When the window expands, the analysis incorporates texts from a longer time span with potentially greater content variation. A longer time span leads to lower similarity between computed topic distributions and a lower stability score.

4.4. Case Study

4.4.1. The Comparison of Trajectory Topics Across Time Slices

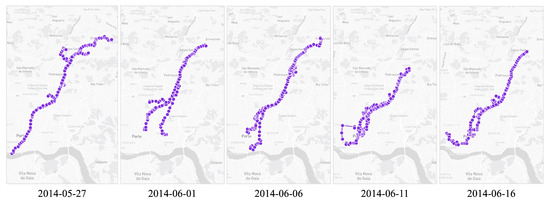

This case study demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed visualization system for analyzing trajectory topic evolution by examining feature changes across adjacent time slices. Specifically, the analysis uses the proposed dynamic trajectory topic algorithm to compute dynamic topics from the Porto dataset. Figure 5 presents a comparison of the spatial distributions for the most frequent representative trajectories within trajectory topic 4, using a 5-day time interval. Trajectory topic 4 exhibits a spatial distribution from the southwest to the northeast, passing through commercial and residential areas, and primarily represents urban commute flows. As shown in Figure 5, the spatial distribution of topic 4 appears generally stable across different time slices.

Figure 5.

Spatial distribution of trajectory topic 4 across adjacent time slices.

The key dynamic change within topic 4 manifests as a difference in commute distance between weekdays and non-workdays. Specifically, on weekdays (e.g., 27 May 2014 and 6 June 2014), the trajectories of topic 4 extend significantly farther to the southwest than trajectories on non-workdays (e.g., 1 June 2014). In summary, the visualized changes in the spatial distribution of representative trajectories for topic 4 clearly reveal the topic’s dynamic evolution. This clear presentation reflects the effectiveness of the proposed method in modeling dynamic trajectory topics.

4.4.2. The Comparison of Different Trajectory Topics

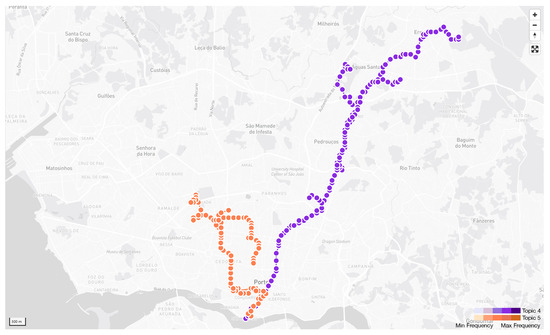

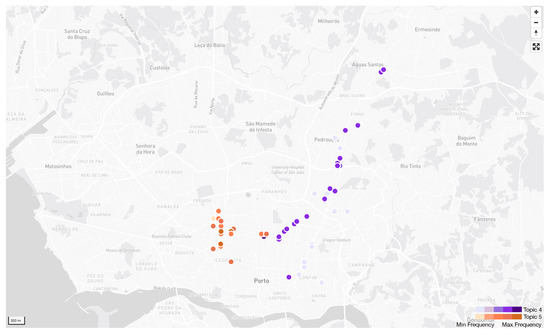

This case study compares the details of different trajectory topics by examining differences in spatial distribution. The analysis again uses the proposed dynamic topic modeling method on the Porto dataset to compare trajectory topic 4 and trajectory topic 5.

First, a spatial comparison reveals distinct patterns. Figure 6 shows the spatial distributions for the most frequent representative trajectories of topic 4 and topic 5 within the same time slice. The orange trajectories, representing topic 5, exhibit regional clustering near tourist attractions (e.g., museums and squares), restaurants, and accommodations. The spatial flow of topic 5 radiates from a central accommodation area, primarily representing tourism flows. As shown in Figure 6, the overall difference in spatial distribution between topic 4 and topic 5 is clearly visible. For a more direct comparison, Figure 7 plots the representative topic words for both topics. Representative topic words denote high-frequency GPS points. The map in Figure 7 illustrates that the topic words for topic 4 are distributed along a southwest-to-northeast commute corridor, whereas the topic words for topic 5 are clustered around the tourist areas.

Figure 6.

The comparison of spatial distribution of trajectories. The purple line and orange line in the map present the trajectories of topic 4 and topic 5, respectively.

Figure 7.

The spatial distribution of trajectory topic 4 and trajectory topic 5. The purple points and orange points in the map present the high-frequency topic words of topic 4 and topic 5, respectively.

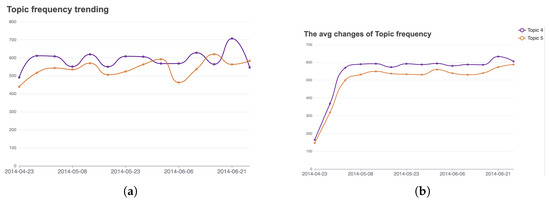

Second, a statistical frequency analysis provides further insights. Figure 8 presents the frequency trends for topic 4 and topic 5. The chart in Figure 8a shows that the frequency of topic 4 is higher than the frequency of topic 5 in 85.71% of the time intervals. This observation suggests that the commute flow from topic 4 constitutes a larger portion of the city’s overall trajectory flow than the tourism flow from topic 5. Additionally, Figure 8b displays the rate of frequency change. In this chart, the frequency change line for topic 4 is consistently above the line for topic 5, indicating a higher rate of change for topic 4 within each time slice.

Figure 8.

The frequency trend of trajectory topics. The purple line represents topic 4, and the orange line represents topic 5. (a) The topic frequency trends of topic 4 and topic 5. (b) The change in frequencies for topic 4 and topic 5 over several time intervals.

In conclusion, although topic 4 and topic 5 show similar frequency trends at a statistical level, the two topics possess markedly different spatial distributions. Therefore, significant differences exist between distinct trajectory topics even within the same time slice. This finding reflects the effectiveness of the proposed method in establishing and analyzing trajectory topics.

5. Discussion

The proposed method holds significant value for the analysis of trajectory data. By combining a domain-specific language model with a flexible topic modeling method, this work provides a powerful analytical tool for discovering dynamic movement patterns from raw GPS sequences. The method has substantial potential impact across multiple domains. Urban planners and traffic engineers can use the system to understand the evolution of commute patterns and identify traffic characteristics. In tourism and commerce, the approach enables the identification of changing visitor flows and the analysis of activity hotspots around commercial centers. Furthermore, the integration of such analytics with IoT platforms could further transform automation in these sectors [40].

Furthermore, the interactive visualization system allows stakeholders without extensive data science expertise to perform complex spatio-temporal analysis, bridging the gap between advanced data mining and practical decision making. The unsupervised nature of the method also reduces dependency on manually labeled data, increasing the applicability of the method to diverse trajectory datasets.

While the proposed method shows strong performance, several areas offer opportunities for improvement. First, the current trajectory representation relies solely on geospatial coordinates encoded via Morton codes. Future work could incorporate richer contextual information and multimodal data, such as timestamps or external factors, to obtain more specific topic representations and to add greater semantic depth to the generated topics. Second, the evaluation is conducted on a single large-scale taxi trajectory dataset from Porto. Validating the method on diverse trajectory datasets is necessary to ensure generalization. The characteristics of taxi movement, being demand-driven, may differ from other forms of mobility like public transportation, pedestrian movement, or logistics. Extending and validating the method on datasets from these other domains remains an important direction for future research. Finally, training the RoBERTa model is computationally intensive. Future work will investigate strategies like model pruning or quantization to reduce training costs. Additionally, we plan to use optimization algorithms, such as MFO, SOA, or HBA, to tune hyperparameters for better efficiency. Future work should, therefore, consider the trade-off between performance and efficiency for practical implementations.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents a complete method for the modeling, analysis, and visualization of dynamic topics in trajectory data. A core contribution of this work is the development of a dynamic topic model. The model uses domain-specific RoBERTa embeddings and a BERTopic-based pipeline to overcome the limitations of static methods and to capture the complex spatial context of movement patterns. The proposed method effectively identifies semantically coherent topics from raw GPS sequences. Another key contribution is the incorporation of an adjustable time window. This feature provides flexibility for analyzing trajectory dynamics across multiple temporal scales. Finally, the work introduces an interactive visualization system with spatio-temporal views. The system successfully transforms abstract model outputs into an intuitive format, supporting the direct exploration and clear understanding of how trajectory topics evolve across space and time. The entire method provides an effective solution for dynamic trajectory topic analysis. Future research will focus on two main directions: (1) integrating multimodal data, such as timestamps and POIs, to enrich trajectory semantics and (2) employing model compression strategies and optimization algorithms to improve computational efficiency for large-scale applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.C. and Y.W.; software, J.L. (Jing Lei) and G.W.; data preparation, G.W. and J.L. (Jing Liao); evaluation, H.C., W.Z. and F.W.; manuscript, H.C. and G.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research study was funded by Key Research and Development Program of Sichuan Province under grant number 18ZS2152, Doctoral Research Fund of Southwest University of Science and Technology under grant number 25ZX7125, and University-Industry Collaborative Education Program under grant number 219-25SJJG21.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available online [37].

Conflicts of Interest

Author Jing Lei was employed by the Technical Center, Mianyang Xinchen Engine Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Hu, D.; Chen, L.; Fang, H.; Fang, Z.; Li, T.; Gao, Y. Spatio-temporal trajectory similarity measures: A comprehensive survey and quantitative study. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2023, 36, 2191–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Bao, Z.; Culpepper, J.S.; Cong, G. A survey on trajectory data management, analytics, and learning. Acm Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2021, 54, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherstinsky, A. Fundamentals of recurrent neural network (RNN) and long short-term memory (LSTM) network. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2020, 404, 132306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, T.Y.; Lee, W.C. Trembr: Exploring road networks for trajectory representation learning. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. (TIST) 2020, 11, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.B.; Guo, C.; Hu, J.; Tang, J.; Yang, B. Unsupervised path representation learning with curriculum negative sampling. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.09373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.B.; Guo, C.; Hu, J.; Yang, B.; Tang, J.; Jensen, C.S. Weakly-supervised temporal path representation learning with contrastive curriculum learning. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 38th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 9–12 May 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 2873–2885. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Han, J.; Fu, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, K.; Xiong, H. Unified route representation learning for multi-modal transportation recommendation with spatiotemporal pre-training. VLDB J. 2023, 32, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 6000–6010. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Cong, G.; Bao, Z.; Long, C.; Liu, Y.; Chandran, A.K.; Ellison, R. Robust road network representation learning: When traffic patterns meet traveling semantics. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, Queensland, Australia, 1–5 November 2021; pp. 211–220. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, D.; Bai, L.; Zhao, R. Jointly contrastive representation learning on road network and trajectory. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, Atlanta, GA, USA, 17–21 October 2022; pp. 1501–1510. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.B.; Hu, J.; Guo, C.; Yang, B.; Jensen, C.S. Lightpath: Lightweight and scalable path representation learning. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Long Beach, CA, USA, 6–10 August 2023; pp. 2999–3010. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Xiang, L.; Chen, L.; Zhong, Q.; Wu, X. Learning universal trajectory representation via a siamese geography-aware transformer. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Shang, S.; Chen, L.; Jensen, C.S.; Kalnis, P. RED: Effective Trajectory Representation Learning with Comprehensive Information. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2024, 18, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blei, D.M.; Lafferty, J.D. Dynamic topic models. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Machine Learning, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 25 June 2006; pp. 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; Jordan, M.I. Latent dirichlet allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Z.; Weng, D.; Liu, S.; Tian, Y.; Xu, M.; Wu, Y. A survey of urban visual analytics: Advances and future directions. Comput. Vis. Media 2023, 9, 3–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Wang, G.; Wang, Z.; Liu, L.; Wei, X.; Wu, Y. A uncertainty visual analytics approach for bus travel time. Vis. Inform. 2022, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Jiang, H.; Tang, K.; Pei, W.; Wu, Y.; Qayoom, A. Knotted-line: A visual explorer for uncertainty in transportation system. J. Comput. Lang. 2019, 53, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.; Sheets, D.A.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Yang, J.; Zheng, M.; Chen, G. Visualizing hidden themes of taxi movement with semantic transformation. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Pacific Visualization Symposium, Yokohama, Japan, 4–7 March 2014; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Grootendorst, M.R. BERTopic: Neural topic modeling with a class-based TF-IDF procedure. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.05794. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:247411231 (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Lee, D.; Seung, H.S. Algorithms for non-negative matrix factorization. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2000, 13, 535–541. [Google Scholar]

- Wallach, H.M. Topic modeling: Beyond bag-of-words. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Machine Learning, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 25 June 2006; pp. 977–984. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, L.; Wu, J.; Zou, F.; Pan, J.; Li, T. Trajectory topic modelling to characterize driving behaviors with GPS-based trajectory data. J. Internet Technol. 2018, 19, 815–824. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Wen, Y.; Guo, W.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, F.; Zhu, M. Mobility pattern analysis of ship trajectories based on semantic transformation and topic model. Ocean. Eng. 2020, 201, 107092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Xu, P.; Ren, L. TPFlow: Progressive partition and multidimensional pattern extraction for large-scale spatio-temporal data analysis. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2018, 25, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Jin, S.; Yan, Y.; Tao, Y.; Lin, H. Visual analytics of taxi trajectory data via topical sub-trajectories. Vis. Inform. 2019, 3, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Tang, Y. Progressive visual analysis of traffic data based on hierarchical topic refinement and detail analysis. J. Vis. 2023, 26, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhan, H.; Liu, J.; Man, J. Visual analysis of traffic data via spatio-temporal graphs and interactive topic modeling. J. Vis. 2019, 22, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadiha, N.; Smaragdis, P.; Panah, G.; Doclo, S. A State-Space Approach to Dynamic Nonnegative Matrix Factorization. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2015, 63, 949–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, D.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, Z.; Huang, J.; Bi, J. Trajectory clustering via deep representation learning. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Anchorage, AK, USA, 14–19 May 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 3880–3887. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Ott, M.; Goyal, N.; Du, J.; Joshi, M.; Chen, D.; Levy, O.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. RoBERTa: A Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.11692. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/1907.11692 (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Mielke, S.J.; Alyafeai, Z.; Salesky, E.; Raffel, C.; Dey, M.; Gallé, M.; Raja, A.; Si, C.; Lee, W.Y.; Sagot, B.; et al. Others. Between words and characters: A brief history of open-vocabulary modeling and tokenization in nlp. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.10508. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Chen, C. Spatio-temporal analytics of topic trajectory. In Proceedings of the 9th International Symposium on Visual Information Communication and Interaction, Dallas, TX, USA, 24–26 September 2016; pp. 112–116. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Liao, C.; Chen, C.; Li, R. Visual exploration of cycling semantics with GPS trajectory data. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, G.M. A Computer Oriented Geodetic Data Base and a New Technique in File Sequencing; International Business Machines Company: Armonk, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.F.; Liu, W.; Suhaim, S.B.; Thirumuruganathan, S.; Zhang, N.; Das, G. Hdbscan: Density based clustering over location based services. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1602.03730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, C. Taxi Trajectory Data. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/crailtap/taxi-trajectory/data (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Mimno, D.; Wallach, H.; Talley, E.; Leenders, M.; McCallum, A. Optimizing semantic coherence in topic models. In Proceedings of the 2011 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Edinburgh, UK, 27–31 July 2011; pp. 262–272. [Google Scholar]

- Aletras, N.; Stevenson, M. Evaluating topic coherence using distributional semantics. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Computational Semantics (IWCS 2013)–Long Papers, Potsdam, Germany, 19–22 March 2013; pp. 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Addula, S.R.; Tyagi, A.K.; Naithani; KKumari, S. Blockchain-empowered Internet of things (IoTs) platforms for automation in various sectors. Artif.-Intell.-Enabled Digit. Twin Smart Manuf. 2024, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).