Adaptive Prescribed-Time Recursive Sliding Mode Control of Underactuated Bridge Crane Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

- 1.

- A novel nonlinear recursive sliding mode controller based on an explicit time term was designed, achieving prescribed time convergence of the system state while reducing controller complexity and enhancing algorithm portability;

- 2.

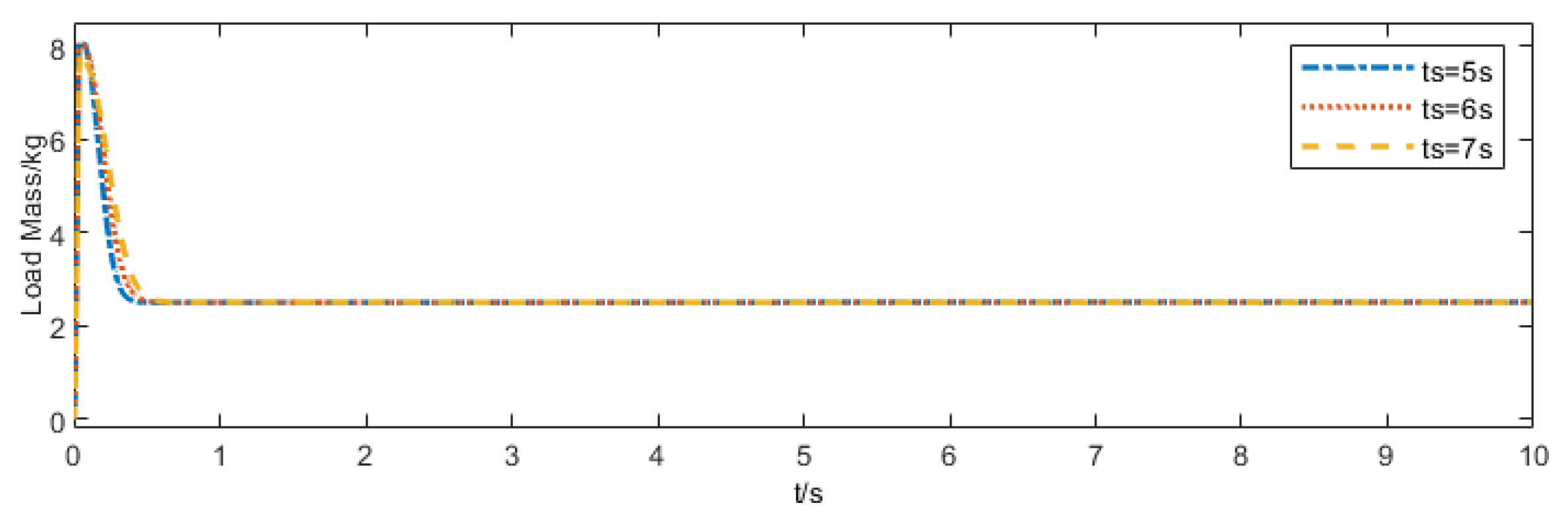

- Focusing on the practical engineering challenge where load masses are not fully known with precision, a mass-adaptive law was designed to estimate load masses online while ensuring convergence within a prescribed time frame. This approach mitigates the impact of unknown mass disturbances on control performance, thereby enhancing engineering applicability;

- 3.

- Simulation experiments validate the prescribed-time convergence performance of the proposed control algorithm, demonstrating its superiority over existing alternative control strategies in both crane positioning and sway suppression.

2. Problem Description and Preparatory Work

2.1. System Dynamics Model

2.2. Preliminary

3. Controller Design

3.1. Recursive Structure Prescribed Time Sliding Surface Design

3.2. Prescribed-Time Sliding Mode Controller Design

4. Stability Analysis

5. Simulation Analysis

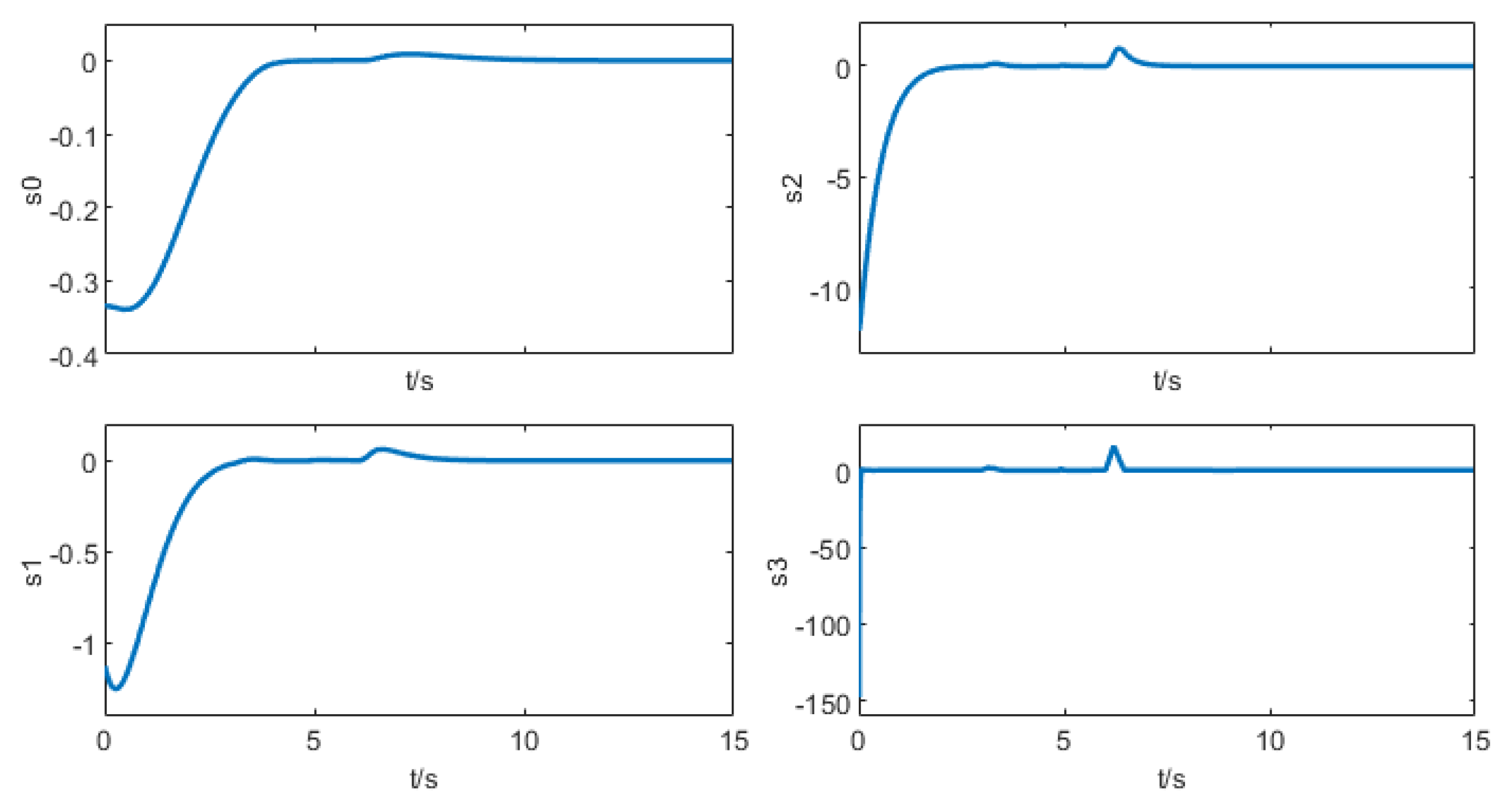

5.1. Performance Evaluation of the PTSMC Algorithm

- 1.

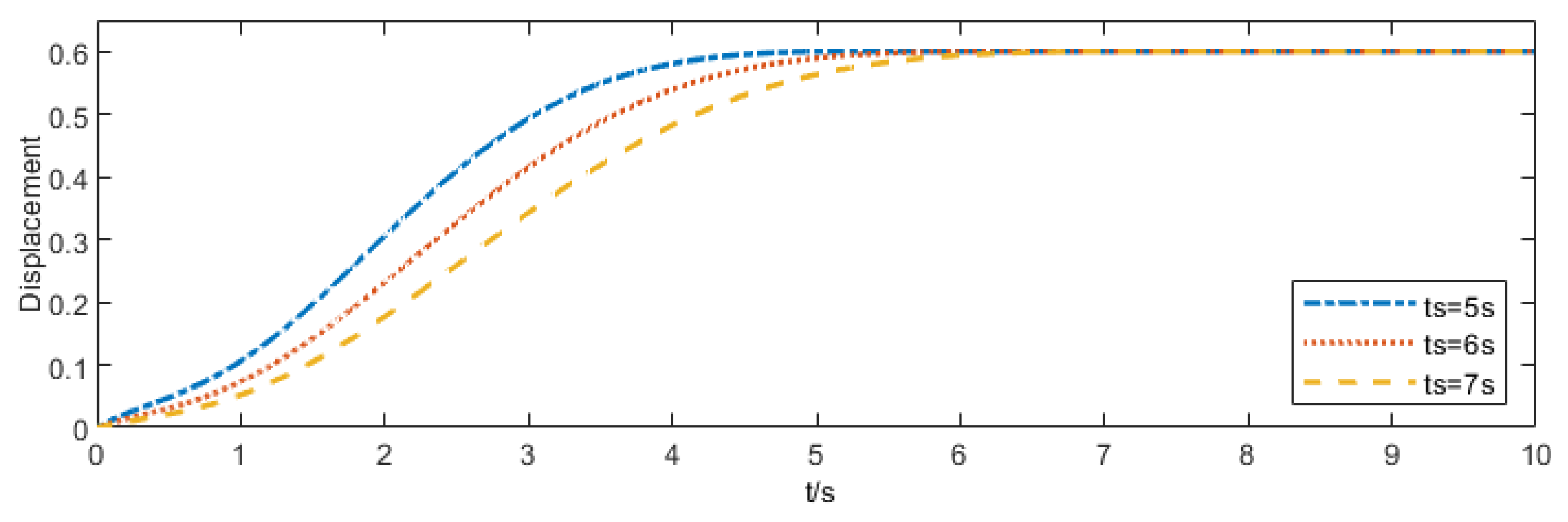

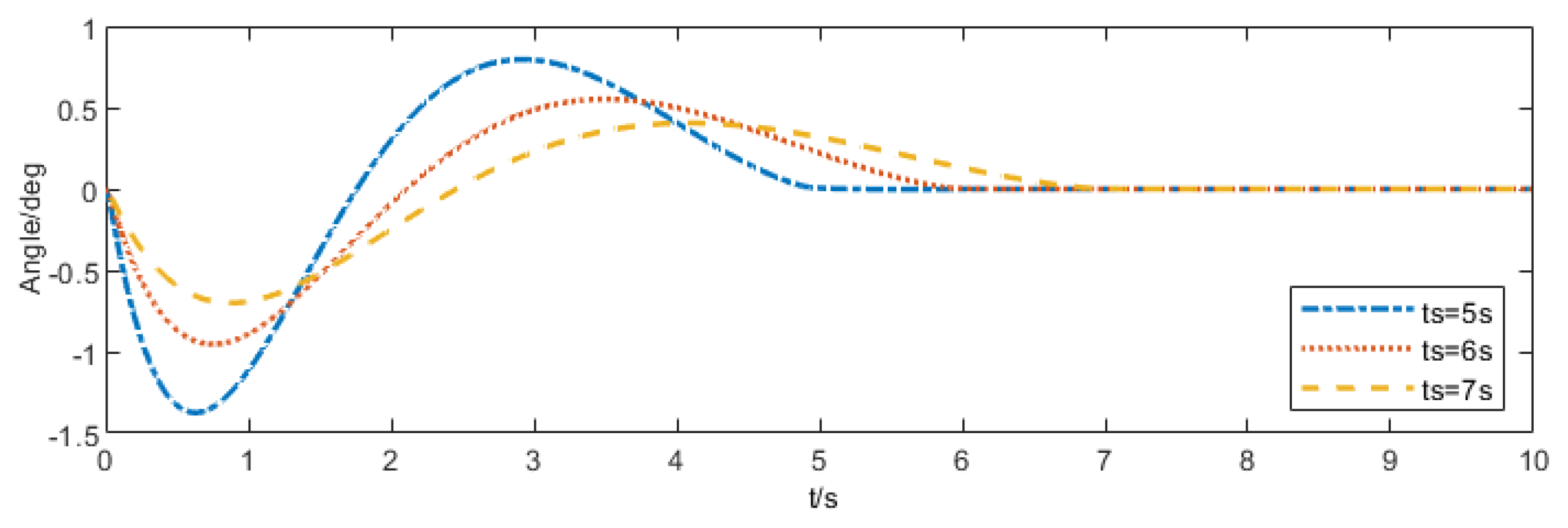

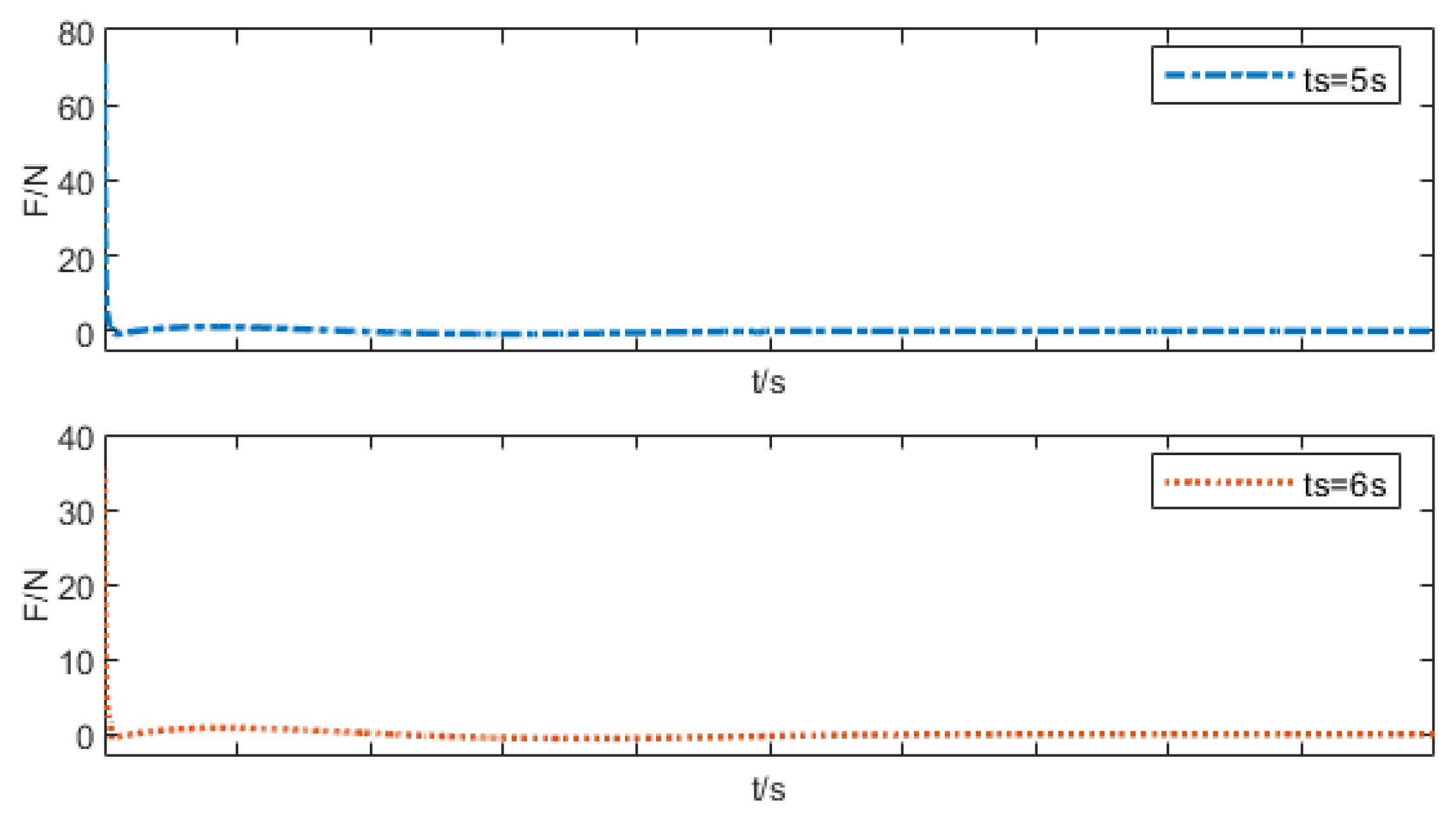

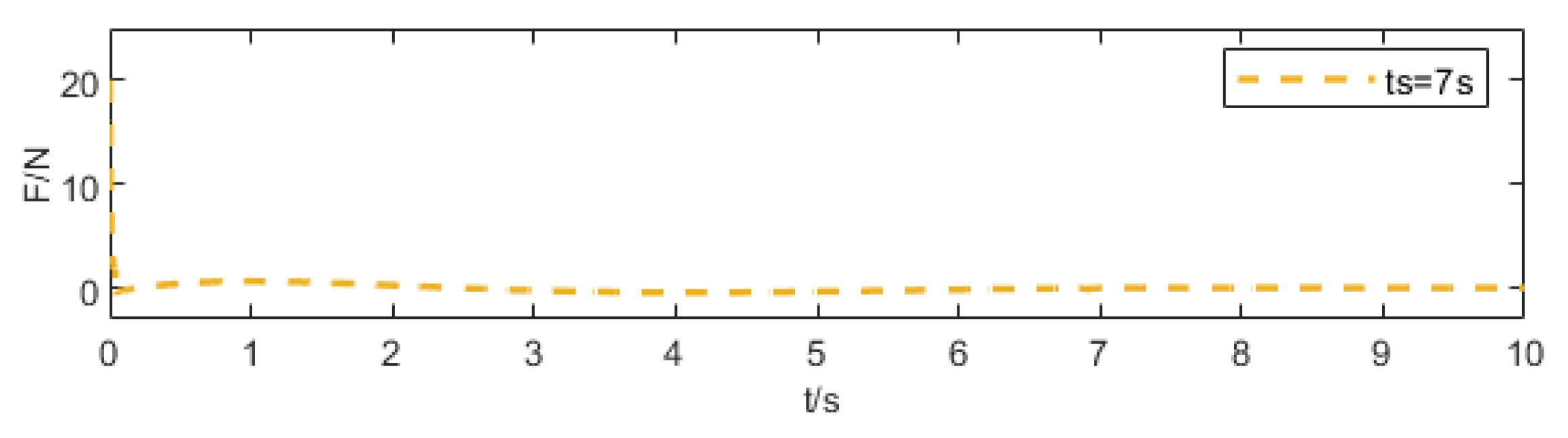

- Convergence Validation at Different Prescribed Times: This test verifies that the proposed control algorithm enables the system state to converge directly and accurately at the specified time under various prescribed time conditions;

- 2.

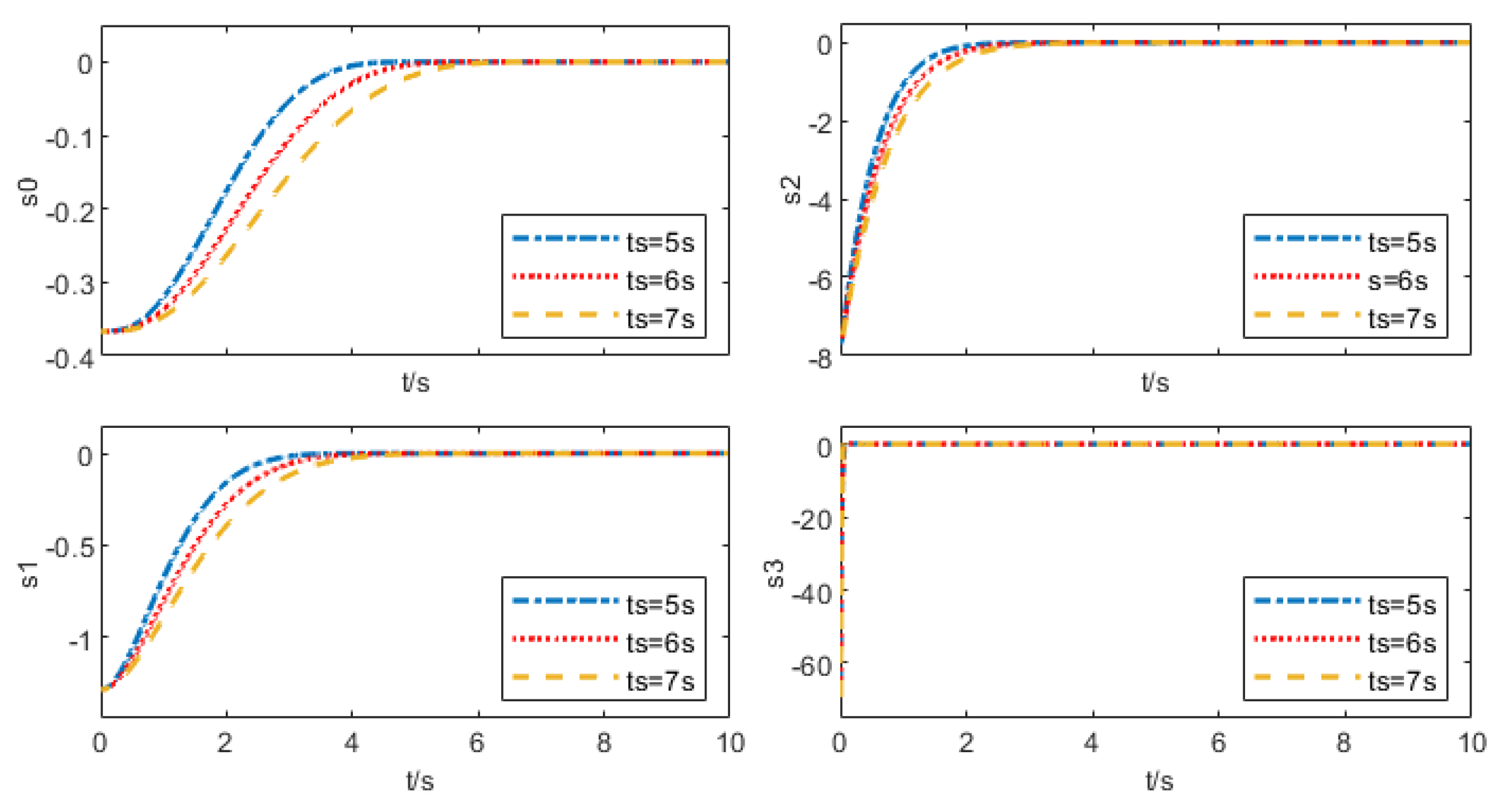

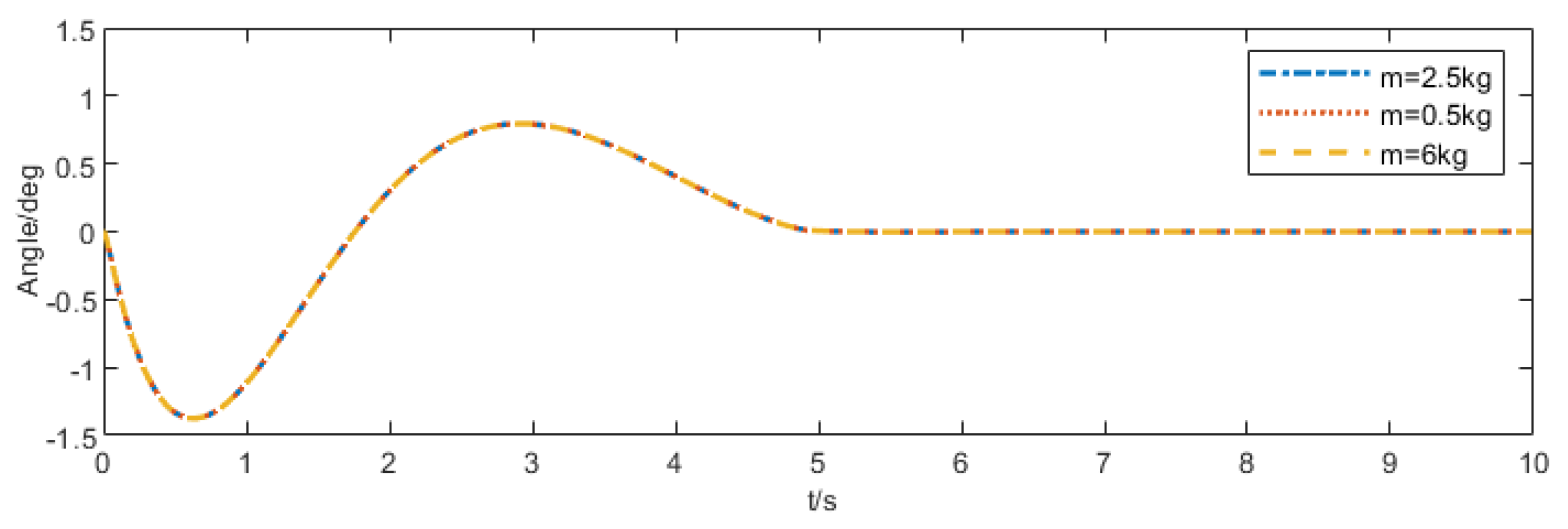

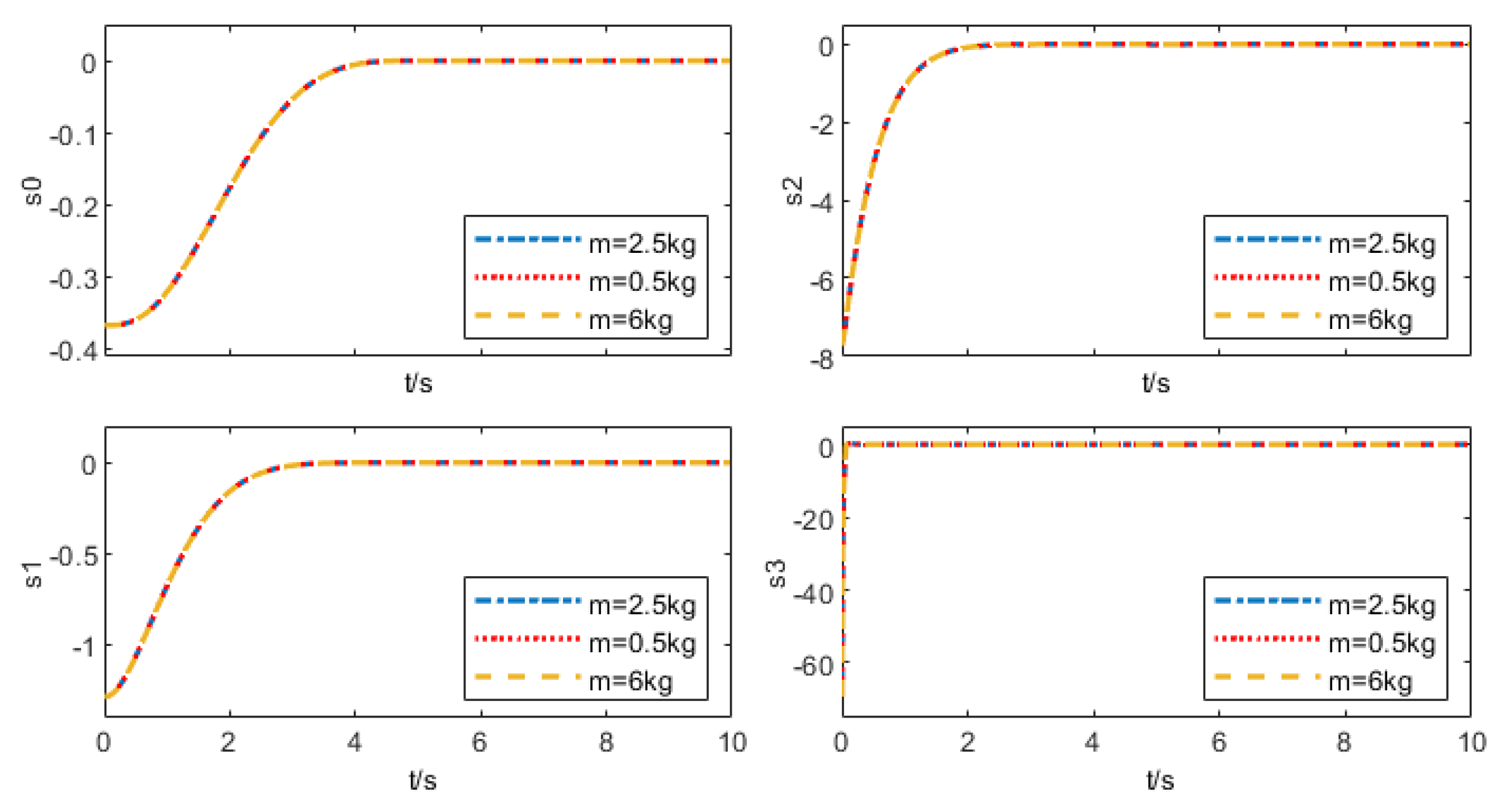

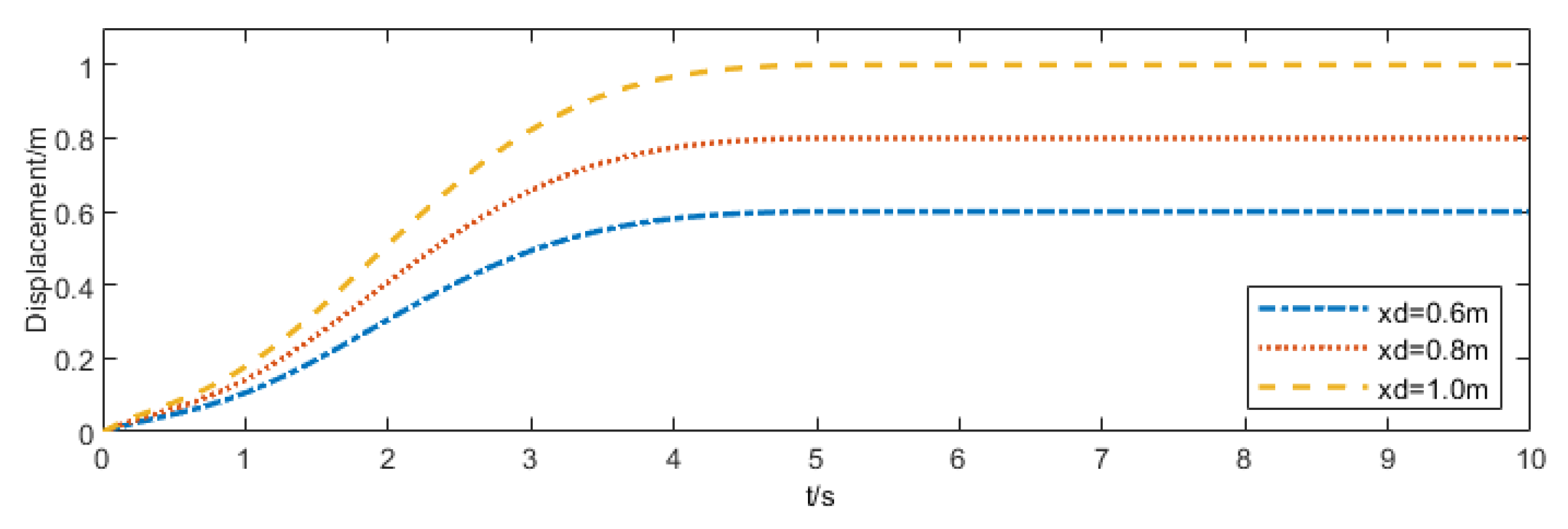

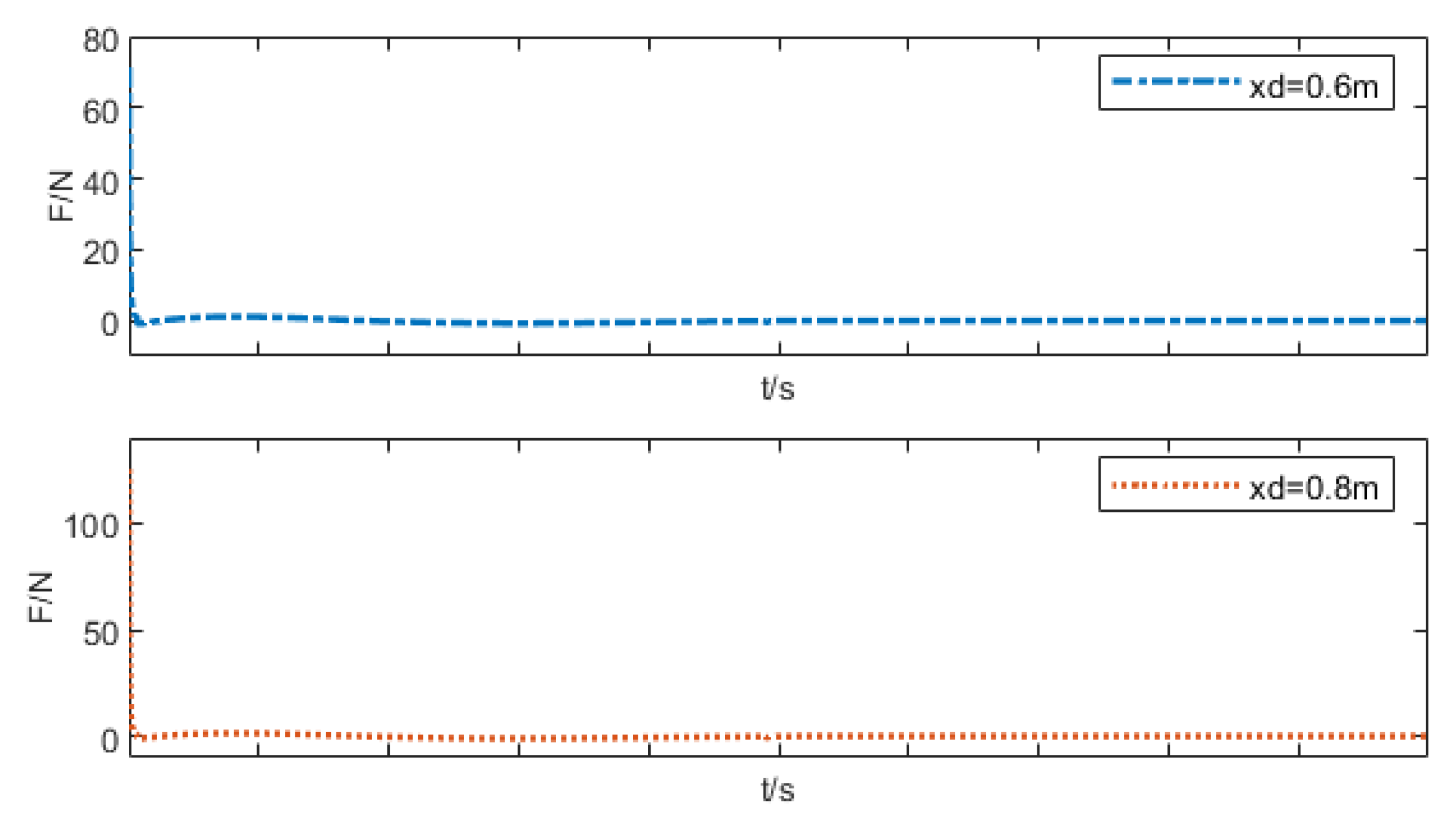

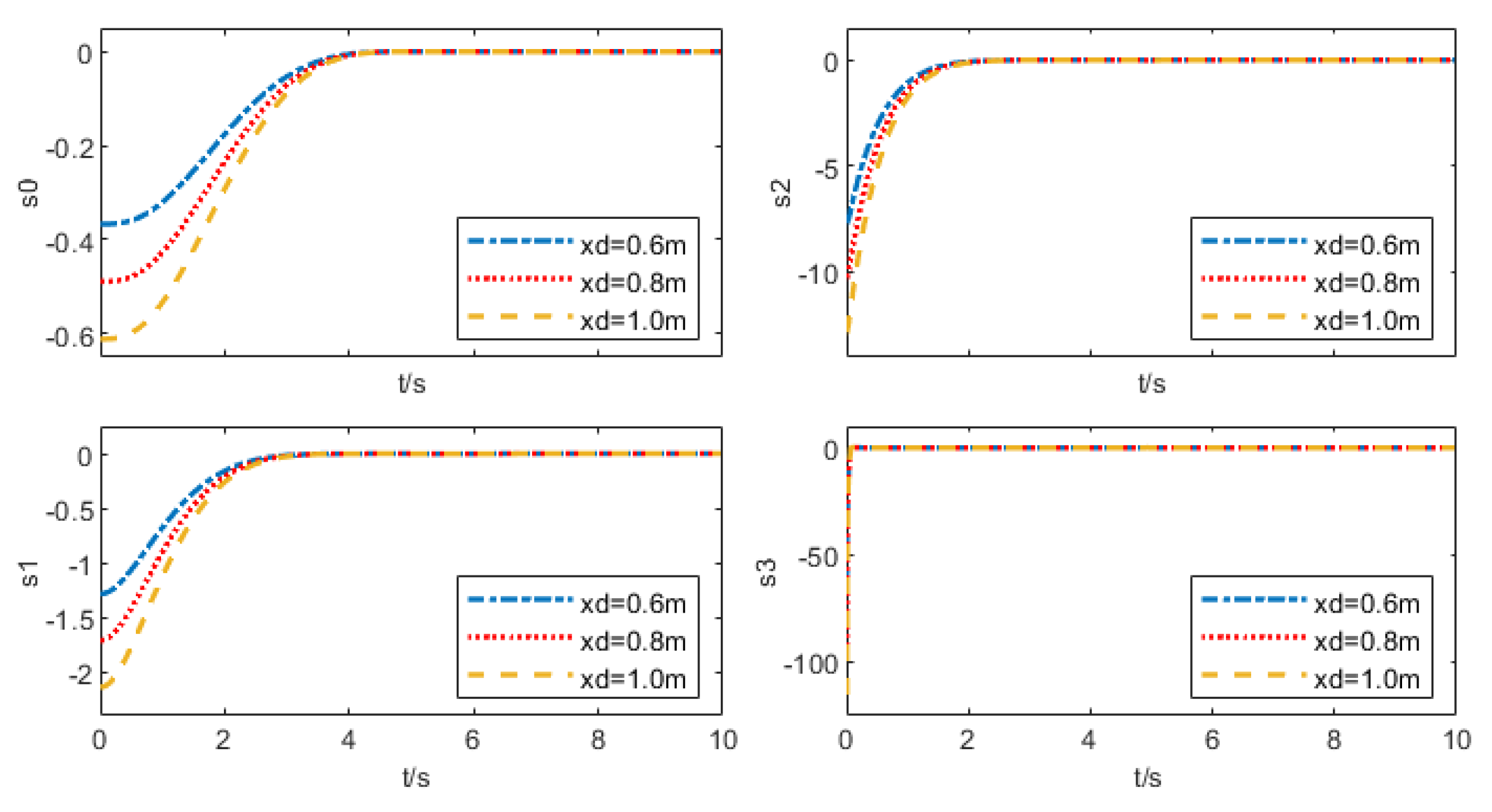

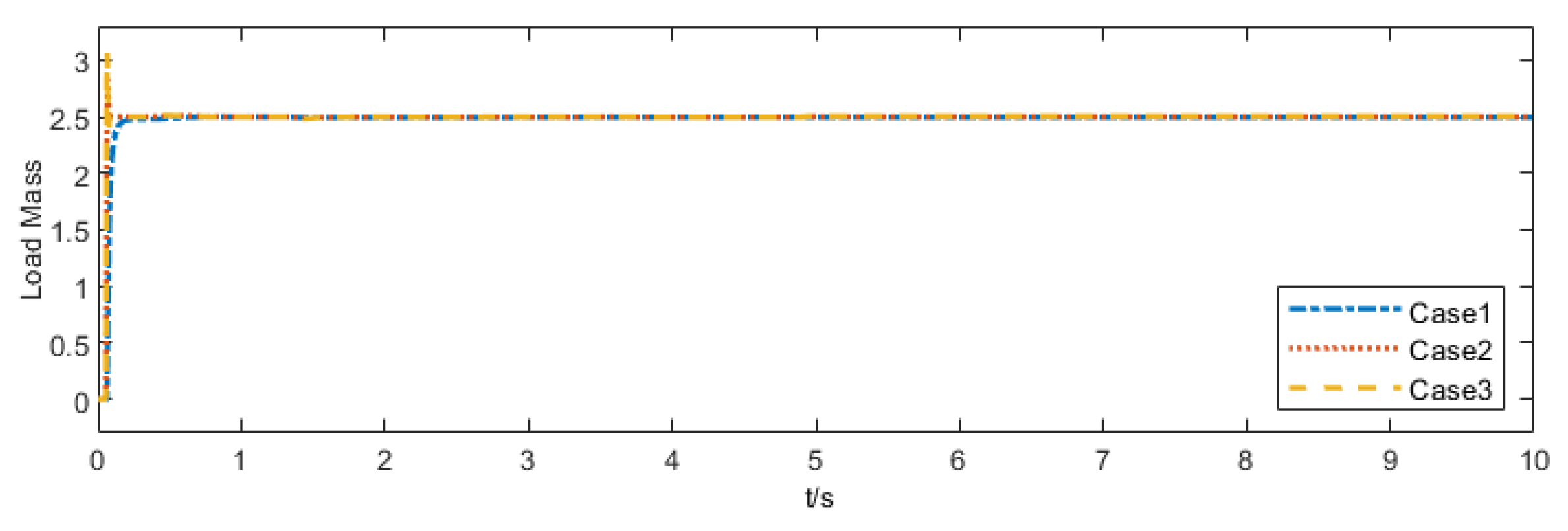

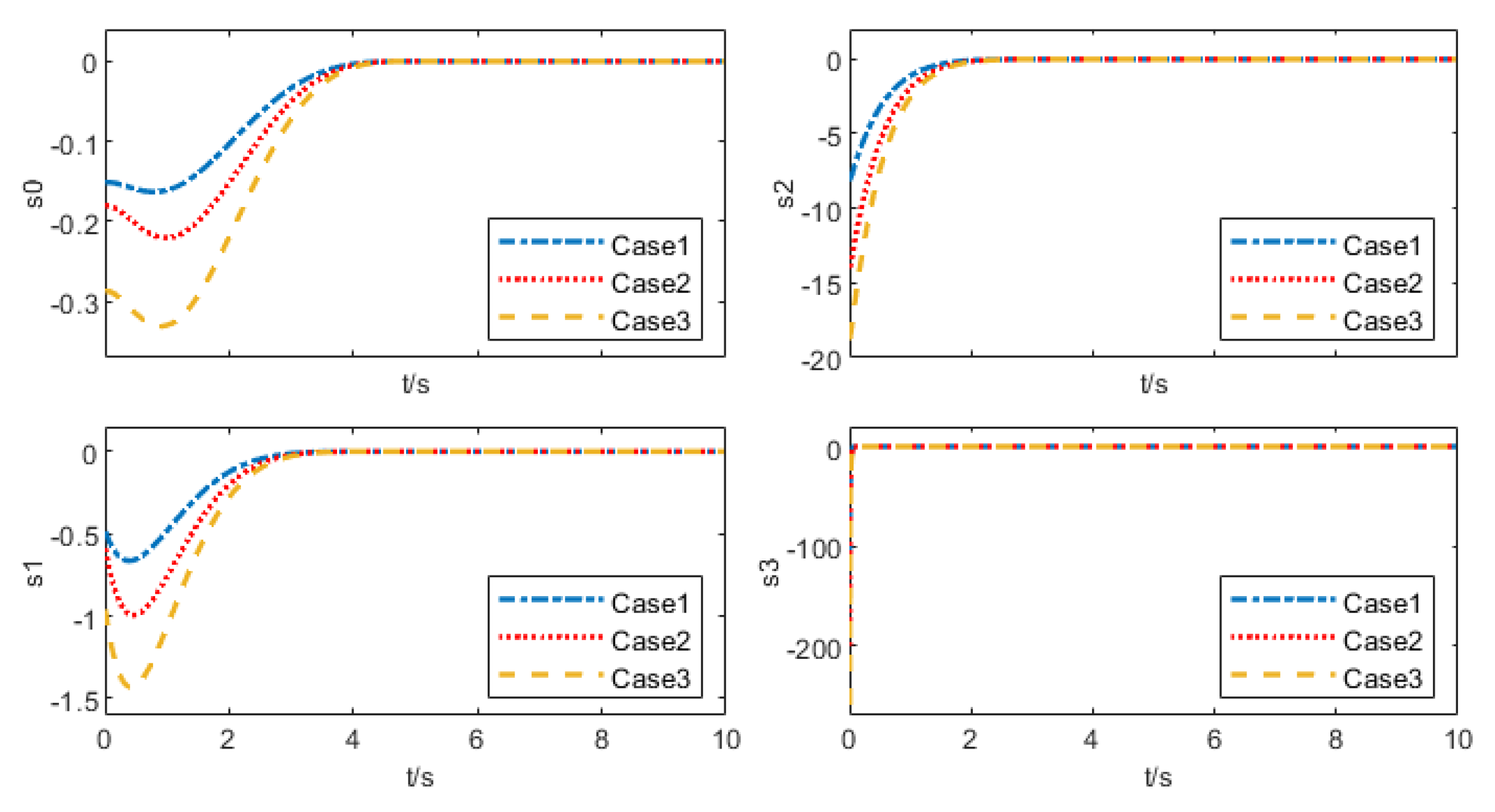

- Robustness Test: Considering that the transfer car performs diverse transport tasks in complex and variable operating environments, its robustness is verified by altering target positions, load masses, and setting non-zero initial conditions.

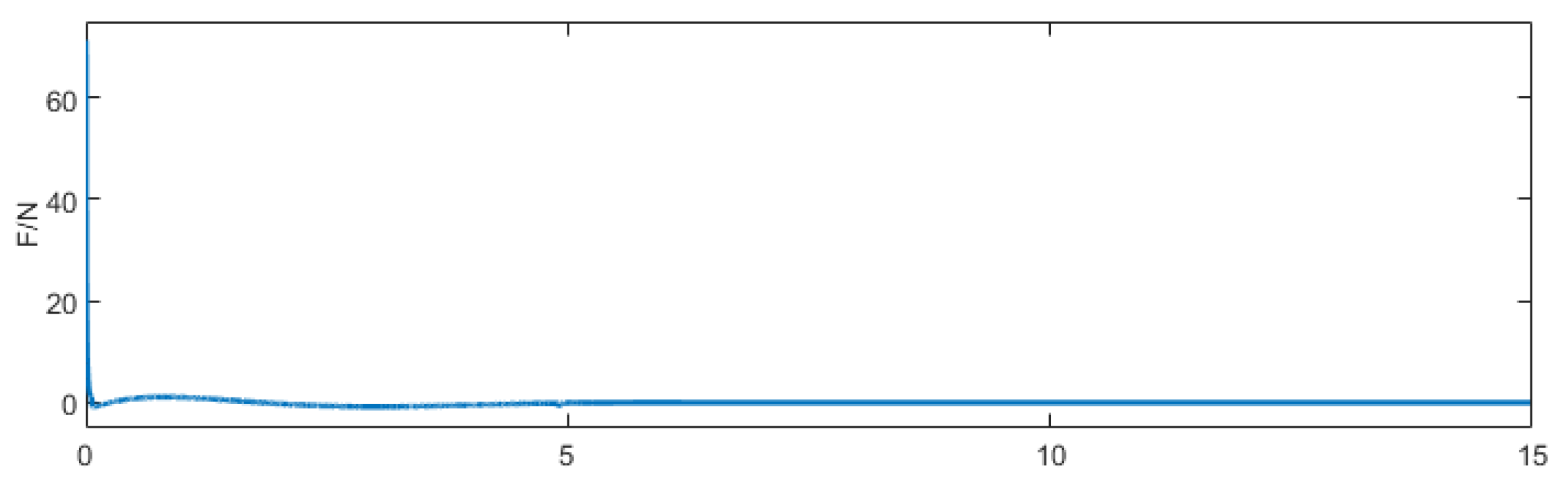

5.1.1. Convergence Validation at Different Prescribed Times

5.1.2. Robustness Test

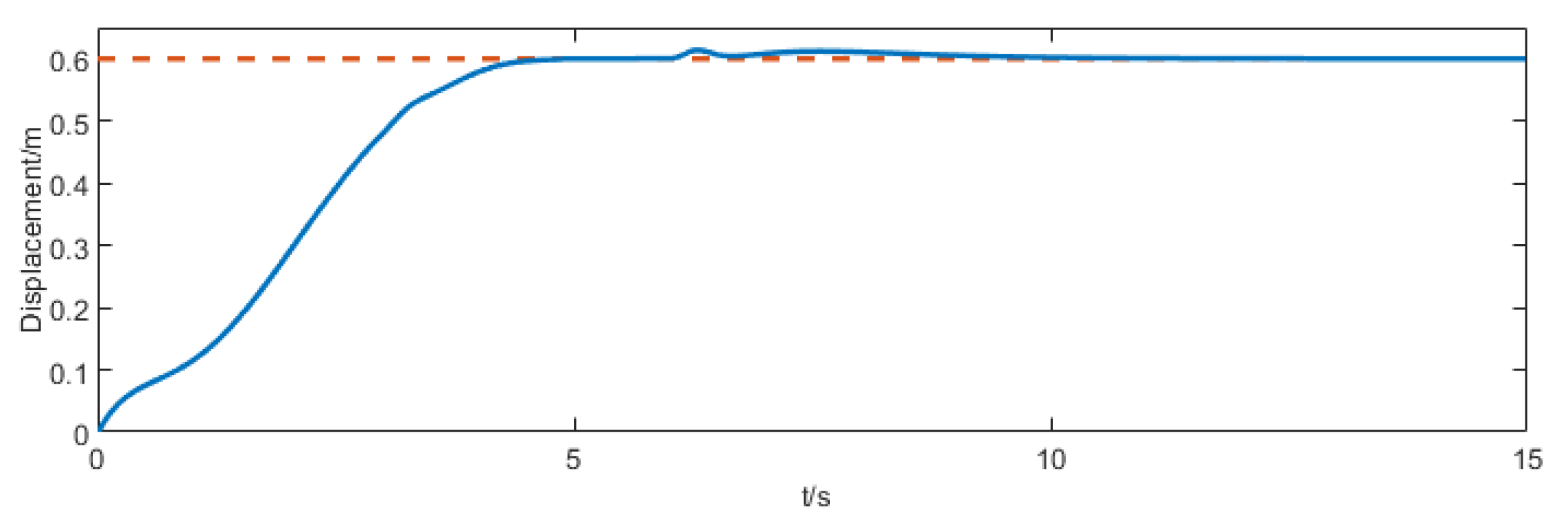

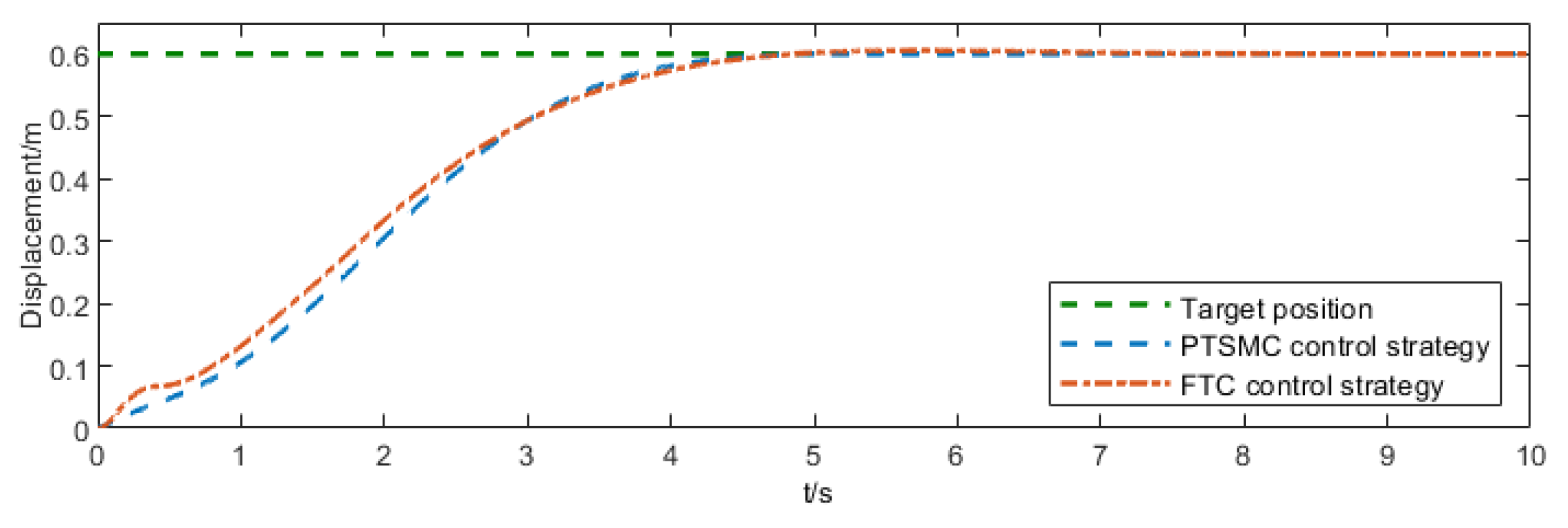

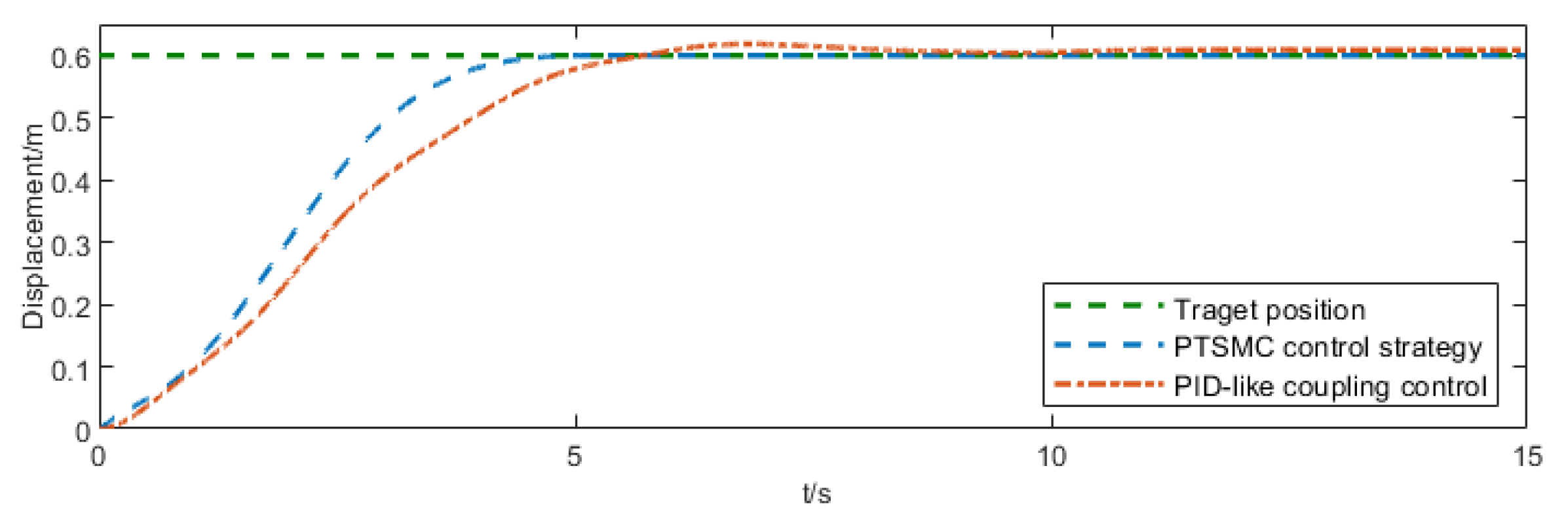

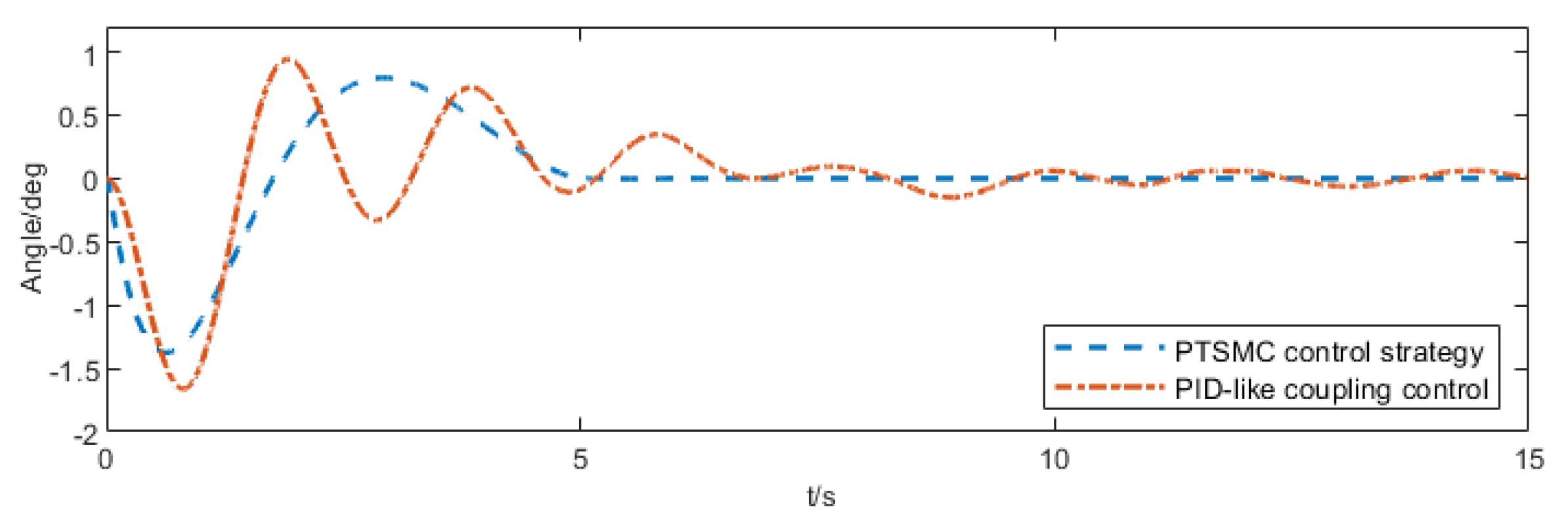

5.2. Comparative Experiments of Different Control Strategies

6. Conclusions

- 1.

- The adaptive prescribed-time sliding mode controller designed in this paper ensures that the state of the bridge crane system converges accurately within a predetermined time. This controller not only exhibits strong robustness but also adapts to diverse transportation task requirements and varied convergence time demands.

- 2.

- The mass-adaptive control law designed in this paper can accurately estimate unknown load masses and adapt to varying loads, significantly enhancing the system’s robustness and adaptability under conditions of unknown load mass;

- 3.

- Simulation results confirm that this control strategy achieves rapid trolley positioning and swing suppression within 5 s. Compared to the FTC strategy and PID-like coupling control strategy documented in existing literature, positioning time is reduced by approximately 2.87 s and 5.9 s, respectively. while swing angle convergence time is reduced by approximately 3.2 s and 5.35 s, respectively. Under this controller, the crane system exhibits minimal swing amplitude during transfer operations, significantly enhancing the operational efficiency and safety of the bridge crane.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdullahi, A.M.; Mohamed, Z.; Selamat, H.; Pota, H.R.; Abidin, M.Z.; Fasih, S.M. Efficient control of a 3D overhead crane with simultaneous payload hoisting and wind disturbance: Design, simulation and experiment. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2020, 145, 106893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.G.; Wang, H.D.; Li, W.; Han, K. Improved Active Disturbance Rejection Control for Positioning and Anti-Swing of Bridge Crane. IET Control Theory Appl. 2023, 40, 574–582. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Wang, W.; Zhou, J. Adaptive control design for underactuated cranes with guaranteed transient performance: Theoretical design and experimental verification. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 69, 2822–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Xie, T.; Li, G.; Yao, J.; Hu, S. Adaptive coupling tracking control strategy for double-pendulum bridge crane with load hoisting/lowering. Nonlinear Dyn. 2024, 112, 8261–8280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Niu, W. Flatness-based backstepping antisway control of underactuated crane systems under wind disturbance. Electronics 2023, 12, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Zhao, E.; Sun, L.; Gao, H. An active swing suppression control scheme of overhead cranes based on input shaping model predictive control. Syst. Sci. Control Eng. 2023, 11, 2188401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; He, Z.; Liu, C.; Du, W. Anti-Sway Adaptive Fast Terminal Sliding Mode Control Based on the Finite-Time State Observer for the Overhead Crane System. Electronics 2024, 13, 4709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.J.; Su, W.H.; Li, J.B. Trajectory Tracking Control of A Lower Limb Rehabilitation Robot with Predefined Time. Control Eng. China 2025, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.P.; Li, W.F.; Chen, Z.L. Fast Terminal Sliding Mode Control of Parameters Uncertain Manipulator Under Disturbance Condition. Mach. Des. Manuf. 2024, 12, 264–269. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.; Lei, M.; Wu, X. Output feedback control of overhead cranes based on disturbance compensation. Electronics 2023, 12, 4474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, G.; Zhang, J.; Leon, J.I.; Wu, L.; Franquelo, L.G. Finite-time sliding mode control for NPC converters with enhanced disturbance compensation. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Regul. Pap. 2025, 72, 1822–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, C.-Y.; Yang, G.; Zhang, C. Finite-time SMC-based admittance controller design of macro-micro robotic system for complex surface polishing operations. Robot. -Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2025, 92, 102881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Liu, G.; Liu, J.; Gao, Y.; Leon, J.I.; Wu, L.; Franquelo, L.G. Fixed-time sliding mode control for NPC converters with improved disturbance rejection performance. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2025, 21, 4476–4487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Tan, N.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, C.; Zhi, Y. A novel anti-swing positioning controller for two dimensional bridge crane via dynamic sliding mode variable structure. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 131, 626–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xu, W. Model-free robust adaptive control of overhead cranes with finite-time convergence based on time-delay control. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control 2023, 45, 1037–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Chen, J.; Xu, D.; Yan, X. Hierarchical global fast terminal sliding-mode control for a bridge travelling crane system. IET Control Theory Appl. 2021, 15, 814–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyakov, A. Nonlinear feedback design for fixed-time stabilization of linear control systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2011, 57, 2106–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Li, J. A novel nonsingular fixed-time control for uncertain bridge crane system using two-layer adaptive disturbance observer. Nonlinear Dyn. 2023, 111, 14001–14013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.H.; Zhou, L.; Zheng, H.B. Swing suppression strategy of bridge crane based on fixed time sliding mode control. J. Mech. Electr. Eng. 2025, 42, 153–163. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, X.T.; Hong, M.Q.; Lu, Y.Y.; Guo, Y. Research on anti-sway and positioning of tower cranes based on fixed-time terminal sliding mode control. J. Nanjing Univ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 47, 533–541. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Yang, T.; Zhou, L.; Fang, Y.; Sun, N. Fixed-Time Tracking Control of 3-D Collaborative Double Boom Cranes with Obstacle Avoidance and Prescribed Performance. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man, Cybern. Syst. 2025, 55, 4175–4187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Ye, H.; Lewis, F.L. Prescribed-time control and its latest developments. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2023, 53, 4102–4116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, K.; Li, X.; Li, K.; Zou, Y. Distributed predefined-time control for cooperative tracking of multiple quadrotor UAVs. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2024, 11, 2179–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Duan, N.; Pei, H. Singularity-free predefined time tracking control for quadrotor UAV with input saturation and error constraints. Nonlinear Dyn. 2025, 113, 13225–13242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, K.; Jia, Y. Appointed-time velocity-free prescribed performance control for space manipulators. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2024, 144, 108783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, J.; Li, L.; Xia, Y. Distributed prescribed-time leader-follower tracking consensus control for high-order nonlinear MASs. Nonlinear Dyn. 2024, 112, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Gu, C. The Prescribed-Time Sliding Mode Control for Underactuated Bridge Crane. Electronics 2024, 13, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.X.; Le, A.V.; Nguyen, L. Adaptive fuzzy observer based hierarchical sliding mode control for uncertain 2D overhead cranes. Cyber-Phys. Syst. 2019, 5, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; He, X. Enhanced damping-based anti-swing control method for underactuated overhead cranes. IET Control Theory Appl. 2015, 9, 1893–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, J.; Han, K.; Shao, C. Finite time controller design for single inverted pendulum system. In Proceedings of the 31st Chinese Control Conference, Hefei, China, 25–27 July 2012; pp. 1468–1472. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Yi, J.; Zhao, D.; Wang, W. Adaptive sliding mode fuzzy control for a two-dimensional overhead crane. Mechatronics 2005, 15, 505–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.X.; Man, Y.C.; Liu, Y.G. Adaptive Finite-Time Control for Underactuated Overhead Bridge Cranes. In Proceedings of the 40th Chinese Control Conference (Session 15), Shanghai, China, 26–28 July 2021; pp. 528–533. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Song, Y.; Hill, D.J.; Krstic, M. Prescribed-time consensus and containment control of networked multiagent systems. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2018, 49, 1138–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Ju, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, Q. The prescribed time sliding mode control for attitude tracking of spacecraft. Asian J. Control 2022, 24, 1650–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; He, X.; Zhu, H.; Chen, Q.; Feng, Y. Partially saturated coupled-dissipation control for underactuated overhead cranes. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2020, 136, 106449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; He, X.; Zhu, H.; Li, X.; Liu, X. PID-like coupling control of underactuated overhead cranes with input constraints. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 178, 109274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Physical Meaning | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| M | Trolley mass | kg |

| m | Load mass | kg |

| l | Rope length | m |

| x | Trolley displacement | m |

| Load swing angle | rad | |

| F | Driving force | N |

| g | Gravitational acceleration | m/s2 |

| Maximum Load Swing Angle | Initial Control Input | |

|---|---|---|

| m = 0.5 kg | 1.374 | 71.33 |

| m = 2.5 kg | 1.374 | 71.33 |

| m = 6 kg | 1.374 | 71.33 |

| Maximum Load Swing Angle | Initial Control Input | |

|---|---|---|

| xd = 0.6 m | 1.375 | 71.33 |

| xd = 0.8 m | 1.831 | 125.20 |

| xd = 1.0 m | 2.288 | 194.62 |

| Initial Position of the Trolley | Initial Swing Angle of the Load | Initial Angular Velocity of the Load | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 0.3 m | 0.035 rad | 0.01 rad/s |

| Case 2 | 0.2 m | 0.07 rad | 0.01 rad/s |

| Case 3 | 0 m | 0.087 rad | 0.01 rad/s |

| Maximum Load Swing Angle | Initial Control Input | |

|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 0.933 | 186.52 |

| Case 2 | 1.557 | 578.00 |

| Case 3 | 2.135 | 973.31 |

| Control Strategy | Trolley Displacement Convergence Time (t/s) | Swing Angle Convergence Time (t/s) | Peak Swing Angle (deg ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PTSMC control strategy | 4.95 | 4.98 | 1.374 |

| FTC control strategy | 7.82 | 8.18 | 2.167 |

| PID-like coupling control | 10.85 | 10.33 | 1.655 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gu, C.; Pei, C.; Feng, Y. Adaptive Prescribed-Time Recursive Sliding Mode Control of Underactuated Bridge Crane Systems. Electronics 2025, 14, 4874. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244874

Gu C, Pei C, Feng Y. Adaptive Prescribed-Time Recursive Sliding Mode Control of Underactuated Bridge Crane Systems. Electronics. 2025; 14(24):4874. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244874

Chicago/Turabian StyleGu, Chan, Chenyang Pei, and Yin’an Feng. 2025. "Adaptive Prescribed-Time Recursive Sliding Mode Control of Underactuated Bridge Crane Systems" Electronics 14, no. 24: 4874. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244874

APA StyleGu, C., Pei, C., & Feng, Y. (2025). Adaptive Prescribed-Time Recursive Sliding Mode Control of Underactuated Bridge Crane Systems. Electronics, 14(24), 4874. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244874