Abstract

The present paper discusses extended reality (XR) applications specifically designed to enhance experiential location-based learning in outdoor spaces, which are utilized in the context of an environmental education program of the Education Center for the Environment and Sustainability (E.S.E.C.) of Kastoria. With the use of augmented, mixed, and virtual reality technologies, an attempt is made to enrich the knowledge and experiences of the students during their visit to the representation of the Neolithic settlement (open-air museum) and their active participation in the learning process. Students take on roles such as those of an archeologist, a detective, and an explorer. By utilizing mobile devices and leveraging GPS technology, students search for and identify virtual findings at the excavation site, travel through time, and investigate the resolution of a mystery (crime) that occurred during the Neolithic period, exploring and navigating the space of the neolithic representation interacting with real and virtual objects, while through special VR glasses they discover the lifestyle of neolithic man. The design of the applications was based on the ADDIE model, while the evaluation was conducted using a structured questionnaire for XR experiences. The fundamental constructs of the questionnaire were defined as follows: Challenge, Satisfaction/Enjoyment, Ease of Use, Usefulness/Knowledge, Interaction/Collaboration, and Intention to Reuse. A total of 163 students were involved in the study. Descriptive statistics showed consistently high scores across factors (M = 4.21–4.58, SD = 0.41–0.63). Pearson correlations revealed strong associations between Challenge—Satisfaction/Enjoyment (r = 0.688), Usefulness/Knowledge—Intention to Reuse (r = 0.648), and Satisfaction—Intention to Reuse (r = 0.651). Regression analysis further supported key relationships such as Usefulness/Knowledge—Intention to Reuse (β = 0.31, p < 0.001), Usefulness/Knowledge—Interaction/Collaboration (β = 0.34, p < 0.001), Satisfaction/Enjoyment—Usefulness/Knowledge (β = 0.42, p < 0.001) and Challenge—Satisfaction/Enjoyment (β = 0.69, p < 0.001). Overall, findings suggest that well-designed XR experiences can support higher engagement, perceived cognitive value, and intention to reuse in authentic outdoor learning contexts.

1. Introduction

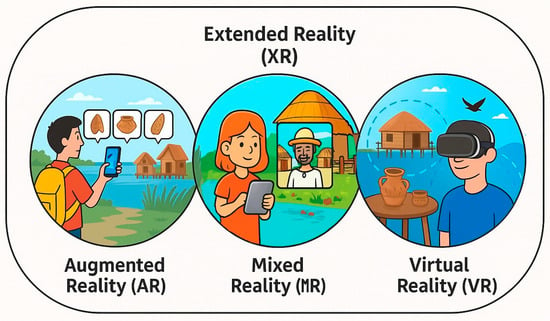

In recent years, the convergence of educational technology, cultural heritage, and environmental education has led to the development of innovative learning experiences that exceed the boundaries of traditional teaching. One of the most significant innovations is Extended Reality (XR), a comprehensive term that includes Augmented Reality (AR), Mixed Reality (MR), and Virtual Reality (VR) [1,2,3].

Augmented Reality (AR) enhances the real environment with digital content, such as texts, images, videos, 3D models, or audio, which are displayed through smart mobile devices or portable AR systems. AR can be categorized into three principal forms [4]:

- Marker-based, where the augmentation is triggered by a virtual marker or object.

- Markerless, in which the augmentation is situated on surfaces of the natural environment.

- Location-based, in which the augmentation is triggered upon the user’s arrival at designated points of interest, with the assistance of GPS sensors.

Virtual Reality (VR) provides complete immersion in a three-dimensional virtual world, eliminating physical stimuli and enhancing the sense of presence (telepresence) [5].

Mixed Reality (MR) facilitates the coexistence of tangible and virtual objects that interact in real time [6].

XR applications have significantly progressed over the last decade, particularly in the sectors of education, tourism, and cultural heritage. Within the educational sector, XR technologies are fundamentally connected to the concepts of active and experiential learning, as they provide students with opportunities to engage in interactive, research-oriented, and multisensory experiences that enhance both cognitive and emotional engagement, thus moving the focus of learning from passive observation to active participation [3,7,8,9].

The current study highlights the development, application, and assessment of a thorough XR educational program, implemented at the Prehistoric Lakeside Settlement of Dispilio, situated in Kastoria. This archeological site, which can be traced back to the 6th millennium B.C., is a remarkable example of a Neolithic settlement that has been preserved along the shores of Lake Orestiada. Currently, the site acts as an open museum, presenting opportunities for experiential and environmental education.

The Education Center for the Environment and Sustainability (E.S.E.C.) of Kastoria, in collaboration with the Digital Media and Communication Strategy Laboratory of the Department of Communication and Digital Media at the University of Western Macedonia, has developed a series of XR digital applications that integrate archeological research, environmental education, and contemporary technology. For the systematic development of digital experiences, the ADDIE model (Analysis–Design–Development–Implementation–Evaluation) was applied [10,11,12,13,14]. The program “Prehistoric Lakeside Settlement of Dispilio” was designed to engage students with the Neolithic past through processes of discovery, exploration, and creative interaction.

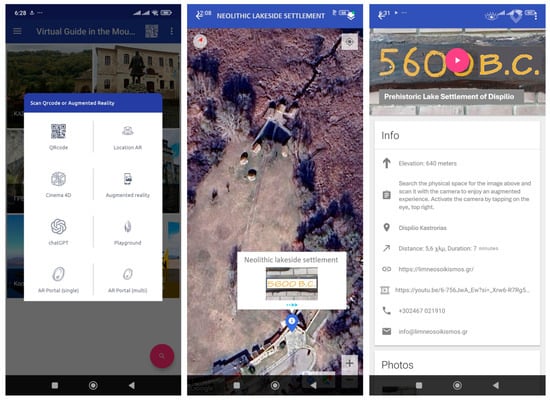

The applications that were developed include the following (Figure 1):

- The augmented reality applications “Virtual Findings in Dispilio”, “Crime in the Lakeside Settlement”, and “Once Upon a Time in Dispilio”, leveraging TaleBlazer (MIT STEP Lab) and geolocation-based navigation [15].

- The MR application “Virtual Guide for the Mountainous Areas of Western Macedonia and the City of Kastoria,” which provides 3D models, avatar narratives, and interactive videos [16].

- The virtual reality experiences titled “Representation of the Settlement” and “Through the Eyes of a Bird” (360° drone view) provide full immersion into the prehistoric setting.

Figure 1.

Extended Reality (XR)—The Case of Dispilio.

The aforementioned digital applications are not functioning independently; instead, they are incorporated into a cohesive three-hour educational program within the framework of the Education Center for the Environment and Sustainability (E.S.E.C.) of Kastoria. The learning process encompasses:

- Preparatory phase, involving guidance and familiarization with the applications.

- Investigation of the field through AR/MR activities.

- Immersion through VR videos.

- Reflection and evaluation, accompanied by discussion, worksheets, and questionnaires.

The educational program is associated with several theoretical and pedagogical contexts:

- Constructivism and experiential learning [17,18], which emphasize learning through action;

- Situated learning [19], where knowledge is constructed within the real context;

- Game-based learning and storytelling [20,21], which enhance experiential engagement through puzzles, narratives, and missions.

Simultaneously, the educational approach of the program aligns with four Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the UN [22], contributing to:

- quality education (Goal 4),

- sustainable development and employment (Goal 8),

- the preservation of cultural identity and sustainable communities (Goal 11), and

- responsible consumption and production (Goal 12).

By integrating digital content, physical space, and experiential interaction, XR applications in Dispilio exemplify a holistic learning approach that connects technology, culture, and the environment. This study aims to highlight how digital storytelling and gamification, when integrated into authentic learning environments, can enhance cognitive understanding, foster empathy, and empower students’ connection to their cultural heritage.

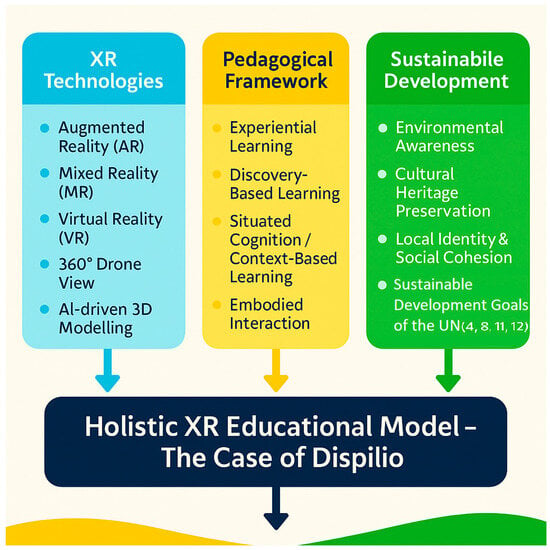

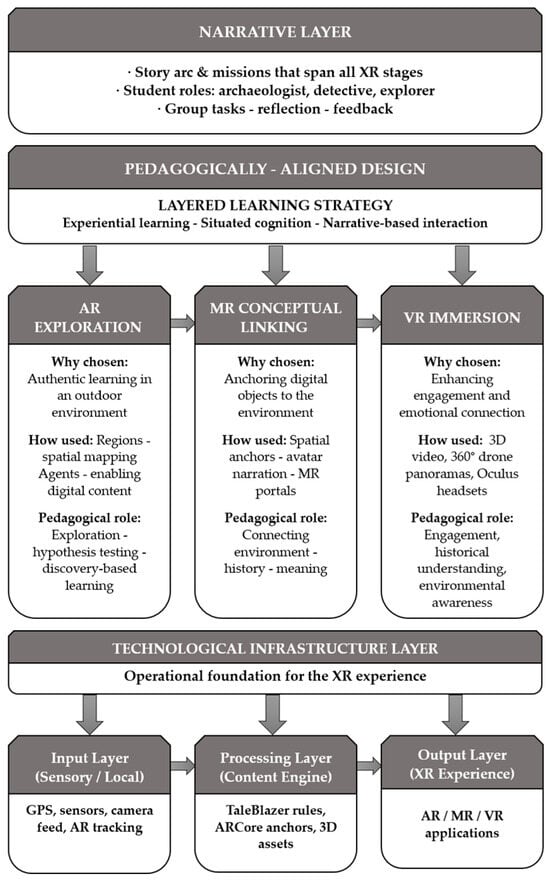

In summary, the proposed Holistic XR Educational Model (see Figure 2) illustrates the interconnection of three fundamental pillars—technological, pedagogical, and sustainable—which collectively form a comprehensive framework for experiential learning through extended reality (XR) technologies in the Prehistoric Lakeside Settlement of Dispilio.

Figure 2.

Holistic XR Educational Model—The Case of Dispilio.

The convergence of the three axes results in a holistic XR learning model, where technology serves as a means of immersion and interactivity, pedagogy acts as a framework for meaning-making, and sustainability is the aim of social and cultural empowerment [23,24].

The present study is directed by the subsequent research inquiries:

- To identify the appropriate software tools and technological platforms for the development of XR educational applications with a pedagogical focus.

- To determine the key design principles that render an XR experience attractive, functional, and educationally effective.

- To assess the educational, cultural, and social impact of XR applications within the context of environmental education and sustainable development.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a concise overview of the literature, while Section 3 describes the educational program. Materials and methods are described in Section 4. Section 5 contains an extensive overview of XR digital applications. The evaluation process and the results of the evaluation are presented in Section 6 and Section 7, respectively. In Section 8, the results and research findings are discussed, limitations are mentioned, and the final conclusions are presented.

2. Related Work

2.1. XR Technologies in Cultural Heritage and Education

The integration of Extended Reality (XR) technologies, which encompass Augmented Reality (AR), Mixed Reality (MR), and Virtual Reality (VR), has garnered significant research interest over the past decade, particularly in the fields of cultural heritage education and museum learning. The rapid advancement in computing power, portable devices, and interactive technologies has fundamentally transformed the presentation of cultural knowledge, transitioning from passive observation of items to experiential, participatory, and immersive learning [25,26]. XR applications enable users to interact effortlessly with their physical and digital surroundings, enhancing spatial understanding, multi-sensory experience, and emotional connection to the cultural space. Consequently, visitors and learners are able to investigate archeological sites and museum collections in a manner that is interactive, narrative-driven, and pedagogically focused, which enhances their knowledge and cultural empathy [27,28].

In a recent systematic review, Dordio et al. [29] assessed 52 academic articles focused on cultural heritage education through XR technologies, showcasing their value as essential teaching instruments in both formal and informal educational contexts. The research indicates that technologies of virtual, augmented, and mixed reality are applied throughout all educational stages, promoting access to cultural, historical, and archeological heritage. The results indicate that the use of XR enhances student interest, engagement, and performance compared to traditional methods. At the same time, it emphasizes the necessity for interdisciplinary collaborations that will strengthen research and innovation in the field of educational utilization of cultural heritage.

Similarly, the study by Anwar et al. [30] proposes a structured framework for leveraging immersive technologies (XR, metaverse) in cultural heritage education, focusing on enhancing user experience, learning, and emotional connection. The text outlines assessment methodologies, investigates the influence of international standards on the creation of immersive environments, and suggests an architectural framework for XR/metaverse that promotes interactivity and collaborative learning.

In addition, the analysis conducted by Tromp et al. [31] showcases ten global case studies investigating the integration of XR technologies with archeological dissemination practices and the management of cultural heritage. The study highlights the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration among computer science, human–computer interaction (HCI) design, and cultural institutions, emphasizing both the curation and dissemination of information as well as the enhancement of usability in XR applications.

Another significant review is by Lin et al. [32], which examines the emotional dimension of XR experiences in the field of cultural heritage. The research, which draws from an analysis of 60 pertinent studies, indicates that most applications are centered on depicting material cultural heritage—like historical structures and museum collections—while the strengthening of users’ enduring emotional ties to intangible heritage is overlooked. Through thematic analysis, researchers identify an imbalance in the study of emotional interaction, primarily focusing on interface stimuli and visual design. The review concludes that the integration of gamification elements and emotional design can significantly enhance the experiential and educational value of XR experiences, thereby contributing to the preservation and transmission of intangible cultural heritage.

The research conducted by Innocente et al. [33] suggests a theoretical framework for utilizing XR technologies in the realm of cultural heritage, derived from an examination of 65 studies. It highlights the advantages of immersive devices (head-mounted displays—HMDs) in enhancing presence, learning, and emotional engagement of visitors, while also pointing out challenges such as technical complexity, accessibility, and user experience evaluation.

The research conducted by Silva and Teixeira [34] offers a comprehensive overview of XR applications within museums, highlighting the multimodal use of digital media for the dissemination and communication of cultural heritage. The authors investigate the ways in which the incorporation of AR, MR, and VR technologies is reshaping the museum experience, offering immersive, interactive, and multisensory methods that surpass conventional exhibitions. The review, based on data from Scopus and Web of Science, summarizes case studies, historical developments, and trends of XR in museum environments, emphasizing its growing role in the education and interpretation of cultural heritage.

Finally, the study by Wang et al. [35] presents a systematic review of 177 research papers, analyzing the applications, technological approaches, and devices utilized for the immersive presentation of cultural heritage. The research highlights the role of XR technologies in the live and interactive representation of cultural experiences, while also pointing out the challenges and obstacles associated with their adoption—such as technical incompatibilities, high costs, and ethical issues. Finally, the authors identify critical directions for future research, aiming to enhance understanding, security, and innovation in immersive applications of cultural heritage.

2.2. Design Approaches, Evaluation, and Challenges in XR for Cultural Heritage

The design, development, and evaluation of extended reality (XR) applications represent a field of intense interdisciplinary research, where human–computer interaction (HCI), pedagogical theory, and technological innovation are interconnected [28,36].

User interface (UI) and user experience (UX) are critical elements in the development of immersive applications, significantly affecting cognitive load, usability, and users’ emotional involvement [37]. Optimal practices recommend interfaces that adapt to the requirements of different age demographics, learning styles, and degrees of technological proficiency [38].

According to Komianos et al. [39], successful XR applications for museums and cultural spaces are associated with factors such as ease of use, real-world connectivity, and interaction quality. These factors significantly influence the acceptance and sustainability of immersive applications by the public. Similarly, Vlachou et al. [40] emphasize the importance of accessibility and metadata standardization to ensure that XR experiences are interoperable and facilitate collaboration among cultural institutions, educational entities, and technology providers.

The study conducted by Kourtesis et al. [41] presents a comprehensive interdisciplinary overview of XR applications in the Metaverse, emphasizing the capabilities of multimodal interfaces (haptics, eye tracking, brain–computer interfaces) as well as the ethical and psychological issues related to privacy, data security, addiction, and cybersickness. The authors emphasize that the increasing coexistence of XR and artificial intelligence (AI) necessitates new ethical and regulatory frameworks, particularly in applications that concern vulnerable social groups, students, or visitors to cultural spaces.

Similar concerns are articulated by Upadhyay et al. [42], who investigate the technological and organizational challenges faced during the application of XR in educational environments, highlighting the importance of technical reliability (system stability), software and hardware maintenance, and comprehensive training for users and instructors. It is noteworthy that despite the growing acceptance of immersive technologies, the learning curve and cognitive load continue to pose significant challenges to learning effectiveness.

Similarly, Davari and Bowman [43] propose the “Context-Aware Adaptation Framework,” which focuses on the adaptability of content based on the environment, lighting, and user behavior, aiming for a dynamic learning experience that adjusts in real time. The research conducted by Chandramouli et al. [44] highlights that the design of XR applications must strike a balance between ‘interface learning’ and ‘conceptual learning’, ensuring that users concentrate on the learning experience without being distracted by the technical aspects of the interface. Simultaneously, Choi et al. [45], within the context of cultural education, propose a “user-centered participatory design” model for XR applications in archeological sites, which is founded on co-creation with students and visitors, ensuring higher levels of engagement, authenticity, and sustainability.

Contemporary research approaches utilize mixed methods for the pedagogical assessment of Extended Reality (XR) experiences, integrating qualitative data such as observations and semi-structured interviews with quantitative indicators to evaluate both the cognitive and emotional engagement of participants, such as:

- Immersion [46], the degree of feeling present in the virtual environment.

- Presence and Co-presence [47], the personal sensation of immersion in a space or environment, along with the awareness of the existence of other individuals in the same space and the interaction with them.

- Usability and User Experience [48], referring to the usability and the experience of an individual during interaction.

- The concepts of Flow experience and Satisfaction [49] refer to the flow experience as a condition of total engagement in an activity, accompanied by feelings of satisfaction.

- Learning Effectiveness [50], the degree to which learning and cognitive objectives are achieved and the skills acquired.

Despite the rapid development, research in the field of XR [28,36,41,51,52,53,54,55] also highlights significant technical, pedagogical, and ethical challenges, such as:

- Accuracy of georeferencing and calibration of GPS/SLAM, particularly in outdoor locations with limited satellite coverage.

- Battery and computational power limitations of portable devices.

- Interoperability between development tools (e.g., Unity vs. Unreal) and platforms (iOS, Android, WebXR).

- Administration and refreshment of digital content to maintain scientific accuracy and educational consistency.

- Ethical considerations and accessibility issues concerning the equal participation of individuals with mobility or sensory difficulties.

- The phenomenon of cybersickness and psychological exhaustion, potentially affecting acceptance and prolonged use.

The demand for interdisciplinary partnerships is now crucial. The most successful educational applications arise from the collaboration of specialists in archeology, education, Human–Computer Interaction (HCI) design, and XR technology, combined with active involvement of end users from the design phase [31,56,57].

2.3. Storytelling and Educational Frameworks in XR for Cultural Heritage

Narration is a foundational aspect of human communication and learning, enabling the organization of experiences and knowledge into logically coherent forms. Within the realm of immersive technologies, interactive storytelling allows users to shift from a passive viewing role to that of an engaged participant and co-creator of the story [58,59]. In XR applications, the narrative combines spatial, visual, and auditory elements, creating multimodal experiences that foster cognitive immersion and emotional connection with the content [60,61,62].

In XR environments, storytelling can act as a “bridge” linking the digital realm with the physical world—users engage with narratives that relate to the place and the items present in the environment. The application of transmedia storytelling in museums and immersive exhibitions, where the narrative extends across multiple media (image, sound, VR/AR), has proven effective in enhancing emotional connection and the sense of presence [63]. The research conducted by Brunetti et al. [64] emphasizes that immersive education relies on interactive storytelling, allowing users to become active participants in the narrative, with learning emerging within the framework of the scenario. Additionally, the study conducted by Wang et al. [65] merges narrative, environmental education, and immersive technologies, suggesting a holistic learning framework in which participants, via symbolic characters and interactive components, are motivated to take on roles and responsibilities, thus cultivating a sense of agency and personal influence.

The incorporation of storytelling components within XR cultural heritage applications is intended not merely for the depiction of events, but also for the transmission of meanings and cultural values [32,66]. Narratives assist students and visitors of archeological and cultural sites in understanding complex historical contexts, recognizing cause-and-effect relationships, and developing empathy towards the individuals or communities depicted [29,67]. The immersive narratives also serve as “cognitive maps” that facilitate a comprehensive understanding of the cultural context, integrating content, space, and storytelling into a cohesive interactive whole [68].

The relational aspect of storytelling in XR environments is founded on the interaction among the user, the system, and the environment. The user engages in narrative nodes that are activated through exploration or action, making each experience non-linear and personalized. This method endorses the idea of embodied learning, which posits that knowledge is gained through both physical and digital interactions within a space [68,69,70].

In XR environments, interactive storytelling employs a range of techniques, including branching narrative, environmental storytelling, and procedural narrative generation. In virtual reality settings, the story’s design adapts to the user’s actions and decisions, facilitating agency and self-definition in the digital realm [71,72].

Additionally, modern XR platforms enable the development of complex narrative experiences that combine geospatial data, three-dimensional models, and AI avatars for scenario simulation. Avatar-based narratives depict historical figures, providing an emotionally charged dimension of interaction, where the visitor engages in conversation, asks questions, or experiences the space through the ‘eyes’ of another character [73].

The effectiveness of narrative XR experiences largely depends on their ability to evoke emotional immersion, which is linked to cognitive processing and the long-term retention of information [74,75]. Studies indicate that XR narratives, which engage the user in the roles of both observer and participant, result in higher levels of empathy and retention compared to traditional teaching methods [76].

Recent advancements integrate artificial intelligence (AI) to facilitate the development of adaptive storytelling experiences, in which the content is altered dynamically according to the user’s behavior, interests, or emotions [77,78,79]. These techniques are founded on sentiment analysis, user modeling, and real-time narrative branching, thereby creating new opportunities for personalized cultural education experiences [80,81].

In the context of culture, AI-driven XR systems facilitate the creation of collective narratives, where numerous users co-create a shared story within the physical space. This converts visitors of museums or archeological sites into co-storytellers, promoting participation and experiential learning [30,82,83,84].

Despite the significant potential, interactive narratives in XR environments face challenges related to maintaining narrative consistency in non-linear scenarios, balancing user freedom with story structure, and addressing ethical issues arising from the use of AI for the creation or representation of cultural content [31,85]. The design of such experiences necessitates interdisciplinary skills and sensitivity to the sociocultural aspects of the content.

2.4. Gamification Mechanisms and Theoretical Foundations in XR for Cultural Heritage

The integration of gamification elements into extended reality (XR) environments for cultural heritage has emerged as one of the most effective strategies for enhancing user engagement, motivation, and experiential learning [86,87,88]. In contrast to the simple digital display of cultural content, gamified XR experiences convert cultural education into an engaging, cooperative, and narratively enriched process. Participants do not merely “observe” an exhibit or a narrative; rather, they engage in action, discovery, and problem-solving within an immersive framework [32,87,89].

The main gamification strategies utilized in XR cultural heritage settings consist of gathering points or objects, levels of progress, challenges, leaderboards, feedback, and achievements. These mechanisms are integrated with narrative and exploratory elements, resulting in a multimodal learning experience that enhances intrinsic motivation—that is, the internal drive for learning [30,90].

Research data confirms that gamified XR experiences enhance engagement, the sense of presence, and satisfaction, while also contributing to knowledge retention through experiential repetition. In cultural and archeological sites, gamification has been employed to encourage visitors to engage with exhibits, solve historical “mysteries,” or reconstruct cultural narratives, thereby enhancing cognitive and emotional involvement [15,31,62,91,92,93,94].

The design of gamified Extended Reality (XR) experiences is theoretically grounded in the principles of constructivism, which posits that knowledge is not passively transmitted but is actively constructed by the individual through experience, reflection, and interaction with the environment [95].

An important development of this theoretical approach is the situated learning theory proposed by Lave and Wenger [19], which asserts that learning is most effectively achieved when it occurs within authentic contexts of action and is enhanced by social interactions.

In this context, XR environments provide users with the opportunity to “learn by doing” within culturally meaningful and realistic settings, taking an active role in exploration, discovery, and problem-solving [4,29,68].

Consequently, gamified XR environments exemplify the principles of constructivism in action, presenting opportunities for:

- Active construction of knowledge through action and interaction.

- Education within genuine settings (situated practice), in which the space and the storytelling influence the comprehension context.

- Collaborative participation in accordance with the “communities of practice.”

- Reflective engagement through immediate feedback and narrative consequences within the digital environment.

In summary, XR experiences are reshaping the teaching and learning landscape into a process that is embodied, multimodal, and socially mediated, connecting theoretical knowledge with experiential comprehension.

2.5. Summary of Findings and Research Gaps in XR for Cultural Heritage

From the aforementioned tasks, it is evident that the field of extended reality (XR) in cultural education has already established a robust research foundation, encompassing various approaches that address the technical, pedagogical, and emotional dimensions of the experience.

Nevertheless, there remain significant unresolved issues that require further investigation, such as the assessment of user experience and learning effectiveness, the maintenance of emotional engagement over time, the adaptability of applications to the needs of diverse users and contexts, the interoperability between systems and devices, as well as the documentation of best design practices that integrate technological and pedagogical innovation.

Overall, the international literature indicates that XR has the potential to transform cultural learning into an experiential, participatory, and emotionally enriched process, provided that future research focuses on interdisciplinary collaborations, universal design standards, continuous evaluation of immersive experiences, and how AI-driven adaptive XR frameworks can enhance experiential learning.

3. The Educational Program

On the southern bank of Lake Kastoria, a Neolithic archeological site reveals to researchers an invaluable wealth of findings and information concerning the civilization of the people who resided in the area nearly 7500 years ago [96].

The Prehistoric Lakeside Settlement of Dispilio is recognized as one of the most important instances of prehistoric settlement in a water environment, revealing how Neolithic humans coordinated their lives in close engagement with the natural surroundings.

Situated close to the excavation site, the “Open Museum” of Dispilio presents a reconstruction of the settlement, giving visitors the opportunity to “explore” the past and understand the aspects of the social, productive, and cultural organization of the prehistoric community [97,98] (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

A representation of the prehistoric settlement in Dispilio.

The Education Center for the Environment and Sustainability (E.S.E.C.) of Kastoria, embracing contemporary global guidelines for promoting sustainable development and enhancing education regarding the environment and cultural heritage, has designed and implemented the educational program “Prehistoric Lakeside Settlement of Dispilio.”

The educational program explores the historical relationship between humans and the environment through the example of the Neolithic culture that developed along the shores of Lake Kastoria, providing students with an experiential connection to the past and local heritage.

In collaboration with the Department of Communication and Digital Media at the University of Western Macedonia, a series of extended reality (XR) digital applications has been developed, which have been organically integrated into the educational program, transforming the archeological site of Dispilio into an open learning laboratory.

The program, lasting three instructional hours, takes place exclusively outdoors. The stages of implementing the educational activity are:

Stage 1: Exploration and Digital Immersion

The learning activity commences with the utilization of three augmented reality (AR) applications: “Virtual Findings in Dispilio,” “Once Upon a Time in Dispilio,” and “Crime in the Lakeside Settlement”, which are based on location-based AR, guiding students in an exploratory investigation of the archeological site (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Groups of students at the site of the representation of the lake settlement at Dispilio.

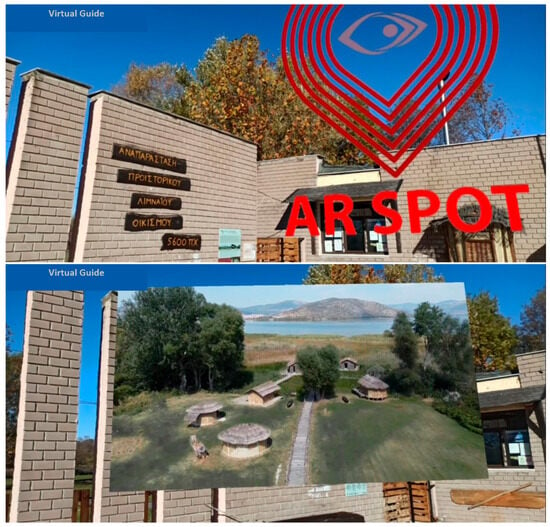

Subsequently, the students utilize the application “Virtual Guide for the Mountainous Areas of Western Macedonia,” which employs mixed reality (MR) technologies and location-based augmented reality (AR). Through this application, they gain access to three-dimensional (3D) models, multimedia content, transparent videos, and narratives featuring avatar characters that bring to life the daily life of the Neolithic period, allowing for the visualization of the constructions and activities of prehistoric inhabitants (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

AR Spot detection at the entrance to the representation of the lake settlement in Dispilio.

Finally, by wearing Oculus glasses, students experience a fully immersive virtual reality (VR) experience within a digitally reconstructed environment of a prehistoric lake settlement. This virtual environment includes human figures, animals, and objects, realistically depicting the daily life of the era. Additionally, the 360° panoramic experience “Through the Eyes of a Bird,” developed through drone aerial shots, provides an alternative visual approach to the landscape, linking spatial perception with emotional engagement and environmental awareness (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Students experience a fully immersive virtual reality (VR) experience.

Stage 2: Self-reflection and Cognitive Connection

Students are working with worksheets that encourage linking Neolithic life to today’s reality:

- “The story of Linus Xelinos, a detective who solves riddles” (for elementary school students), linking Neolithic existence with natural resources and ecosystems

- “Utilize It Again” (for Secondary Education students) examines sustainable management practices and compares the past with the principles of linear and circular economy.

Through this process, environmental sensitivity, systemic thinking, and empathy towards Neolithic society are cultivated.

Stage 3. Expression and Evaluation

The students express their conclusions concerning life and the organization of the prehistoric settlement, while the program’s evaluation is conducted through questionnaires that assess the usability, usefulness, and experiential value of XR applications.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Educational Activity Design Framework

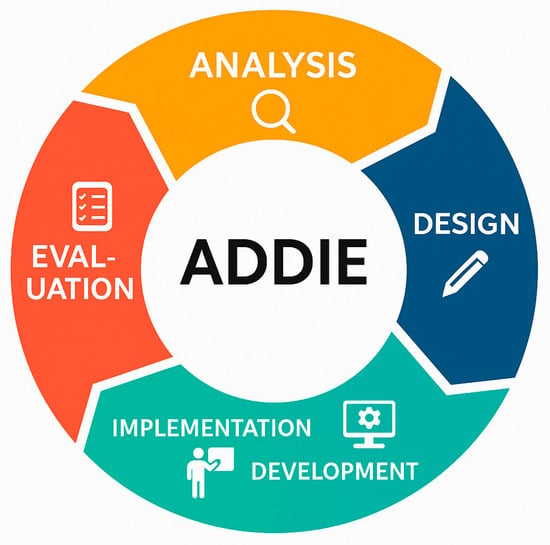

In the context of designing and developing extended reality (XR) applications for the educational program “Prehistoric Lakeside Settlement of Dispilio,” the ADDIE model [10,11,12,13,14] (Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, Evaluation) was employed as a reference point (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

ADDIE model.

Throughout all phases of execution, the educational team members of the Education Center for the Environment and Sustainability (E.S.E.C.) of Kastoria worked in close partnership with the scientific personnel of the Digital Media and Communication Strategy Laboratory of the Department of Communication and Digital Media at the University of Western Macedonia. This collaboration ensured the integration of educational, technological, and cultural parameters at all stages of the project.

4.2. Analysis Stage

During the analysis phase, a thorough examination of the needs and prerequisites for the design of the XR educational experience was carried out, with the objective of:

- the identification of instructional objectives and the intended learning results,

- the evaluation of the level of knowledge and skills possessed by the participating students,

- the assessment of technological parameters (GPS accuracy, connectivity, lighting, external conditions),

- and ensuring the appropriateness and validity of the content based on its scientific and educational value.

Emphasis was placed on the flexibility of AR, MR, and VR technologies in outdoor environments, as well as their capacity to foster experiential learning, collaborative exploration, and a sense of empathy with the surroundings and historical context.

4.3. Design Phase

In the design stage, the framework for the learning activities and their associated XR applications was defined. The subsequent elements were reviewed:

- the forms of interaction (tactile input, mobility, GPS activation, voice directives),

- the narrative structure of each application (exploratory, narrative, mystery),

- the various forms of multimedia content (3D models, sound, video, explanatory texts),

- and the elements of gamification (points, challenges, puzzles, avatars, feedback).

The design was based on the principles of storytelling-based learning and context-based education, enhancing the connection between knowledge and the real-world environment.

By employing the Google Maps API, the regions of interest were mapped out, and the Agents were specified, which are the points at which the digital content is engaged.

For instance, in the application “Virtual Discoveries at Dispilio,” these points correspond to virtual discoveries, whereas in the application “Crime in the Lakeside Settlement,” they serve as “nodes” of mystery and narrative.

4.4. Development Stage

In the course of the development stage, three applications of Augmented Reality (AR), one application of Mixed Reality (MR), and two applications of Virtual Reality (VR) were created, employing different software environments.

Each application operates independently and has not been integrated into a single unified XR system. However, it is pedagogically organized as an app-oriented XR ecosystem, where each application functions as a module within a broader narrative and learning flow. Thus, the XR experience was not implemented as a single-platform solution, but rather as an orchestrated sequence of autonomous XR applications, structured into distinct phases of learning: Exploration → Conceptual linking → Immersion.

The independent functioning of applications did not disrupt the educational experience; instead, it allowed for a flexible, expandable, and adaptable design that can be reshaped according to the context, the student audience, and the learning objectives. For instance, in younger age groups, a specific application is chosen from the three AR applications. Thus, the system is capable of functioning as both an integrated XR learning flow and a selective toolkit, appropriate for scaffolded implementation across different levels of familiarity.

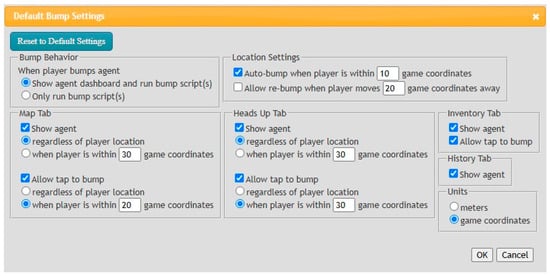

For the development of AR/MR/VR applications, various software solutions were utilized.

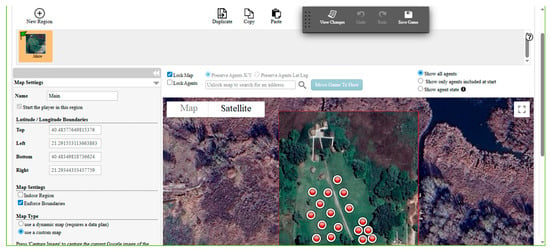

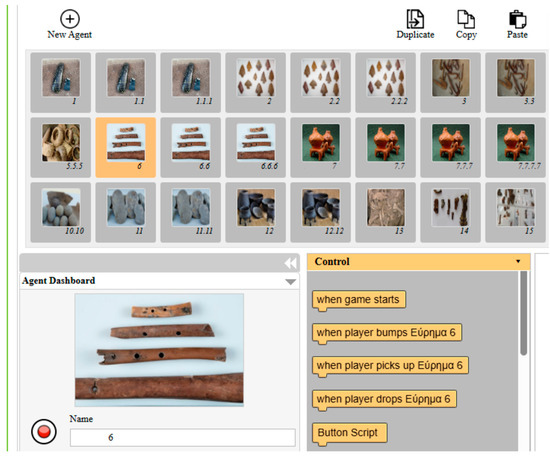

The TaleBlazer (MIT STEP Lab) was employed for the projects “Virtual Discoveries at Dispilio,” “Crime in the Lake Settlement,” and “Once upon a Time in Dispilio”. The foundation of TaleBlazer (https://taleblazer.org/, accessed on 1 October 2025) lies in visual programming, which facilitates the creation of interactive games based on GPS, utilizing the elements of Regions and Agents. The Regions define the map of the area (see Figure 8), while the Agents activate the content (texts, images, sounds, activities) when the user approaches the location (see Figure 9). Tablet devices were equipped with the applications and evaluated in the setting of the prehistoric lake settlement to verify GPS accuracy, stability, and user-friendliness.

Figure 8.

Screenshot of the development environment: Regions.

Figure 9.

Screenshot of the development environment: Agents.

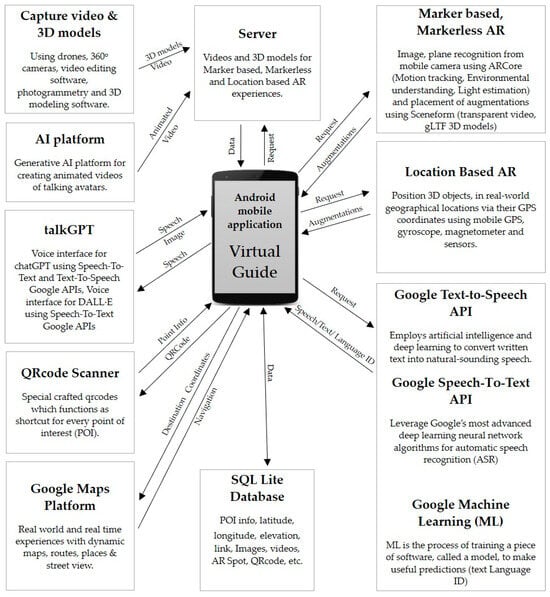

The Mixed Reality application “Virtual Guide” was developed using Android Studio and the ARCore SDK (https://developers.google.com/ar, accessed on 1 October 2025), and it supports marker-based, marker-less, and location-based augmented reality. It includes 3D objects, transparent videos, Google Street View, audio narratives, and chatbot communication (ChatGPT 4.1) (see Figure 10). The “Virtual Guide” was piloted in the representation of the prehistoric lake settlement of Dispilio, demonstrating the effectiveness of MR technology in cultural interpretation and educational immersion.

Figure 10.

«Virtual Guide» App Functionality.

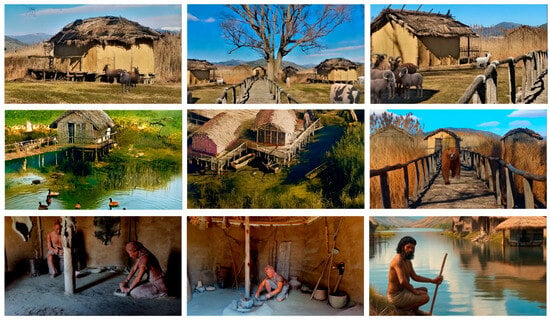

The development of Virtual Reality (VR) 3D video and 360° Drone View applications was accomplished through the use of Blender and Adobe Premiere Pro. The virtual reality experience illustrates the everyday lives of prehistoric residents via videos produced with the aid of artificial intelligence (AI-assisted modeling). Furthermore, the app “Through the Eyes of the Bird” includes panoramic aerial views of the settlement at different times of the year. These experiences were implemented on Oculus Quest glasses, offering full immersion and spatial comprehension.

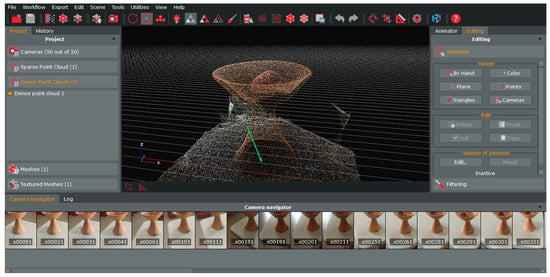

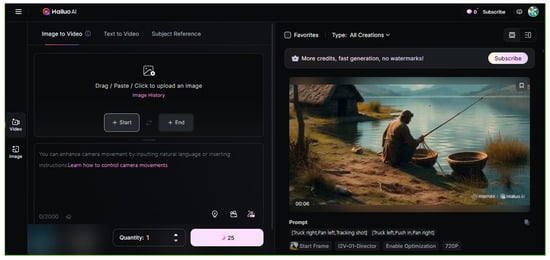

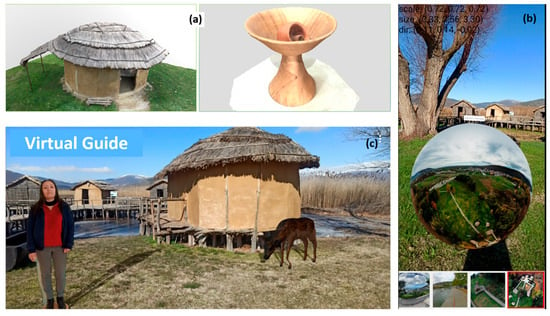

To generate the three-dimensional models of the Prehistoric Lakeside Settlement of Dispilio along with the archeological artifacts, a blend of photogrammetry methods and 3D modeling software was utilized, specifically 3DF Zephyr 7.507 (see Figure 11), Blender 3.4, Polycam (see Figure 12) (https://poly.cam/, accessed on 1 October 2025) and Sketchfab (see Figure 13) (https://sketchfab.com/, accessed on 1 October 2025). This procedure included the acquisition of high-resolution images and videos, the creation of a dense point cloud, the production of a mesh and texture, and the optimization of models for application in XR environments (ARCore, TaleBlazer, and MR headsets). The software AI Heygen (https://www.heygen.com/, accessed on 1 October 2025) and AI Hailuo (https://hailuoai.video/, accessed on 1 October 2025) were utilized for the creation of virtual characters (see Figure 14). The final models have been integrated into AR, MR, and VR applications, offering a high level of realism and interactivity.

Figure 11.

Screenshot of the development environment: 3DF Zephyr (accessed on 1 October 2025).

Figure 12.

Screenshot of the development environment: Polycam (accessed on 1 October 2025).

Figure 13.

Screenshot of the development environment: Sketchfab (accessed on 1 October 2025).

Figure 14.

Screenshot of the development environment: AI Hailuo (accessed on 1 October 2025).

The selection of the aforementioned tools was not solely based on their availability or technical ease, but rather on a pedagogically substantiated design rationale that aligns with the principles of experiential learning, situated cognition, and narrative-based interaction.

The integration of the tools followed a layered design logic, where learning progresses gradually from exploration to deepening and ultimately to an embodied emotional understanding: AR Exploration → MR Conceptual Connection → VR Immersion.

4.4.1. Exploration Phase (AR)—TaleBlazer (MIT STEP Lab)

The selection of TaleBlazer was made because of its GPS-based visual programming architecture, enabling the entire archeological site to be approached as a learning map. The Regions and Agents converted the locations in space into narrative nodes and points of discovery, an aspect that is closely associated with the theories of situated learning and embodied interaction.

Introduced by Lave et al. [19] in 1991, situated learning emphasized that learning should occur within the same context in which it will be applied, that is, an authentic, real-world setting. Unlike traditional classroom-based approaches, situated learning does not prioritize theoretical or abstract knowledge; instead, it encourages learners to engage with practical, real-world problems, fostering learning through hands-on experiences and active participation in authentic environments. The importance of context in learning has been known for many years [99]. Collins et al. [100], in their description of situated learning, emphasize the notion of learning and acquiring skills in contexts that resemble real-life situations.

Taleblazer is also an ideal tool for developing applications that involve narrative cartography. Research on narrative cartography has highlighted how mapping itself can become a medium for storytelling and cultural interpretation [101,102]. Narrative cartography may include, among other things:

- maps with embedded stories, such as historical accounts, personal experiences, or cultural narratives,

- spatial storytelling, where events or experiences unfold across geographic space, and

- the expression of subjective or emotional experiences that are connected to specific places.

Reason for selection: It supports authentic learning in an outdoor environment through the use of geolocation.

How it was utilized: Regions → spatial mapping/Agents → enabling digital content.

Pedagogical role: Exploration—hypothesis—discovery-based learning.

4.4.2. Conceptual Connection Phase (MR)—ARCore and Android Studio

Following the initial exploration, ARCore, through the virtual guide application, facilitated the transition from observation to the interpretation of the space. The application of markerless AR, 3D models, Street View, and educational avatars has established a level of mixed reality (MR) through which students can “reconstruct” mentally the Neolithic settlement as it might have appeared in its original form.

The MR interaction provides the opportunity to incorporate digital elements that are no longer visible or accessible to the public, such as:

- archeological findings that are stored in the laboratories,

- digital guides (avatars) that provide information,

- narrative characters that represent the inhabitants of the settlement and tell stories.

Thus, the space functions not merely as a location for observation but as a “narrative carrier,” allowing students to link history, place, and meaning through active, embodied, and cognitively centered exploration.

- Reason for selection: The ability to anchor digital objects in space.

- How it was utilized: Spatial anchors—avatar narration—MR portals.

- Pedagogical role: Connecting environment—history—meaning.

4.4.3. Immersion Phase (VR)—Oculus Quest, Blender, and Premiere

The VR immersion was not introduced at the beginning, but rather at the end of the learning experience, serving as an emotional climax. The 3D videos and 360 aerial view (Drone View) have enhanced the sense of presence and confirmed that immersion can strengthen empathy, understanding, and reflective thinking.

- Reason for selection: VR fosters engagement and emotional connection with the content.

- How it was utilized: Video editing and spatial reconstruction.

- Pedagogical role: Historical embodied understanding—environmental awareness.

4.4.4. Narration and Interaction (Narrative Support)—AI Heygen and Hailuo

Rather than employing a static audio commentary, avatars generated through generative AI were used to make the storytelling more human-centric and dialogic. The avatars functioned as “digital guides,” transforming the narrative from passive listening into co-presence, thereby making the experience more active and cognitively focused.

According to Mayer’s principles [103] of Multimedia Learning, talking avatars (also called pedagogical agents) can support the personalization principle because they can increase engagement and enhance the sense of social presence in students, as they feel that a real person is guiding them through the learning process. When a character speaks in a conversational tone, learners feel more socially supported. Avatars can humanize the experience. A friendly, on-screen agent can make the material feel less abstract and more personal. Virtual agents with human appearance in XR applications have proved their effectiveness in many studies (e.g., [104,105,106,107]).

- Reasons for selection: Pertinent to affective XR learning and embodied storytelling.

- How they were utilized: Avatar narration—interactive “guides” in the space.

- Pedagogical role: Engagement—identification—narrative with emotional depth.

In conclusion, the technologies of AR, MR, and VR were not utilized in isolation; rather, they were integrated into a sequential learning strategy (Figure A1). AR enhanced exploratory investigation, MR facilitated conceptual connections with space, while VR offered emotional immersion and historical empathy. Avatars functioned as narrative agents, linking the various levels and enhancing the memory and involvement of the participants.

The development was accompanied by continuous testing, feedback, and optimization, with active participation from both educators and students, ensuring the functionality and pedagogical coherence of the applications.

4.5. Implementation Stage

In the initial phase of the educational activity, students receive fundamental information regarding the content of extended reality applications, as well as usage instructions on how they operate. This preparatory process ensures that students understand the capabilities of the applications, enabling them to actively participate without technical difficulties in the subsequent learning experience.

Following the initial phase, the student groups are provided with tablet devices that have pre-installed extended reality applications. Through the screens of their devices, students can access digital maps that depict the layout of the Prehistoric Lakeside Settlement. Displayed on the maps are colored dots, which represent the successive destination points in the area. Each point is accompanied by usage instructions to facilitate navigation and understanding of the activity. Consequently, the process is transformed into a guided exploration, wherein students undertake a journey of discovery in the space, while at the same time engaging with the digital elements that enhance the authentic experience.

4.6. Evaluation Stage

A structured questionnaire was designed for the evaluation of the XR experience, based on existing studies and models of educational technology and gamification [11,92,108,109,110,111,112].

The questionnaire consisted of three sections:

- Demographic information (gender, age, prior experience with XR technologies).

- Evaluation of the educational activity (organization, participation, collaboration).

- Evaluation of digital applications employing a five-point Likert scale, across the subsequent categories: Challenge, Satisfaction/Enjoyment, Ease of use, Usefulness/Knowledge, Interaction/Collaboration, and Intention to reuse.

5. Description of the XR Applications

Taking advantage of XR technology’s capabilities, the applications were designed with specific goals in mind:

- To serve as innovative educational tools, integrating physical spaces with digital representations.

- To recreate the daily life of prehistoric people by integrating 3D models of their homes, tools, and activities into the real setting of the settlement

- To enhance experiential learning by allowing students to engage with historical contexts as if they were living in that period

- To foster collaboration and active participation through the use of digital devices (mobile phones, tablets, and MR headsets) familiar to students.

- To promote the development of observation skills, critical thinking, and digital literacy.

Although the applications primarily target students involved in educational programs, they also serve as an innovative cultural and tourist resource for every visitor to Dispilio, enhancing the understanding and attractiveness of the archeological site.

5.1. Augmented Reality (AR) Application—Virtual Discoveries at Dispilio

The augmented reality digital application “Virtual Discoveries at Dispilio” is an innovative educational resource aimed at promoting experiential learning and facilitating direct engagement of students with archeological research.

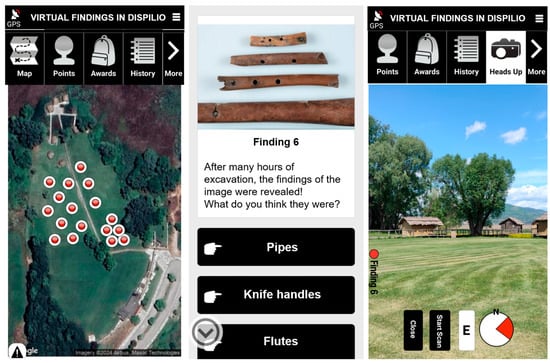

Participants take on the role of archeologist-researchers, navigating the site to identify virtual points and findings. At each location, participants are invited to discover an object, identify it, determine its possible material of construction (e.g., wood, bone, stone), and hypothesize its potential uses in the daily life of the prehistoric society of Dispilio. Through multiple-choice questions, students engage cognitively and participate in a playful exploration that integrates the physical space with the digital environment (see Figure 15).

Figure 15.

Sample images from the app «Virtual Findings in Dispilio».

The theoretical framework of the application is based on the principles of experiential and discovery learning, where knowledge is not passively transmitted but acquired through active participation, exploration, and interaction. Simultaneously, the development of observation skills, critical thinking, and collaboration is being promoted, while the understanding of archeology as a science is being enhanced.

5.2. Augmented Reality (AR) Application—Crime in the Lake Settlement

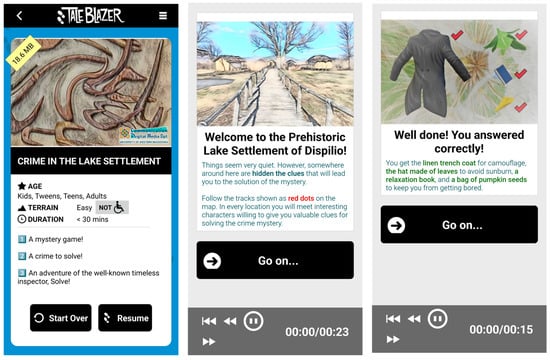

The augmented reality application “Crime in the Lake Settlement” offers students and visitors of the Prehistoric Lakeside Settlement of Dispilio a unique exploratory experience through a mystery game.

Participants assume the role of detectives and are invited to resolve a crime that seems to have taken place in the prehistoric community. Each point reveals signs, riddles, items, and characters that provide essential information and challenges to be addressed (see Figure 16).

Figure 16.

Sample images from the app «Crime in the Lake Settlement».

By following this procedure, the students:

- participate in an interactive mystery adventure,

- strengthen experiential learning by linking the physical environment to digital content,

- cultivate observation skills, collaboration, and critical thinking,

- discover elements of prehistoric life in Dispilio in a playful and engaging manner.

This application converts a visit to the archeological site into an educational journey of discovery, where the past is brought to life through games, exploration, and interaction.

5.3. Augmented Reality (AR) Application—Once upon a Time in Dispilio

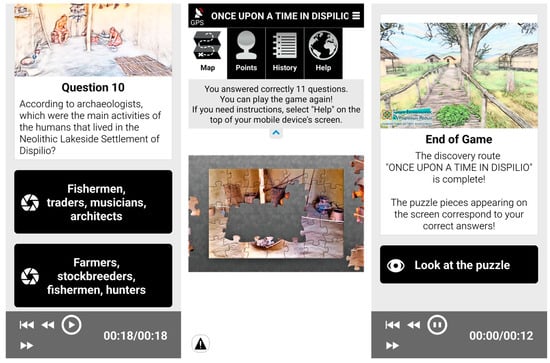

The augmented reality digital application “Once upon a Time in Dispilio” utilizes location-based AR and gamification elements to provide students with an interactive learning experience within the representation of the prehistoric lake settlement. Participants navigate the area, and at each point of interest, digital content (texts, images, sounds) is activated, accompanied by multiple-choice questions (see Figure 17).

Figure 17.

Sample images from the app «Once upon a Time in Dispilio».

The procedure promotes attentive observation of the area and links information to the real components of the archeological setting. For every accurate response, learners accumulate points and segments of a puzzle, which is progressively filled in, offering a feeling of advancement and accomplishment.

Using the digital application, pupils are introduced to knowledge concerning:

- the era when the settlement emerged and the methods for its chronological dating,

- the archeologists engaged in the excavations,

- the trees that existed in the area during the Neolithic period,

- the rationale behind the building of houses on stilts,

- the substances employed in the creation of the houses,

- the daily activities of prehistoric inhabitants (fishing, hunting, agriculture, animal husbandry),

- the outcomes of the archeological excavations (figurines, flutes, tools, etc.), the materials utilized in their making, and their significance.

The digital AR application “Once upon a Time in Dispilio” features 16 e-multiple-choice questions, providing feedback for each answer, so that the process serves not only as an assessment but also as a means of active learning.

5.4. Mixed Reality (MR) Application—Virtual Guide

The digital application of mixed reality, “Virtual Guide for the Mountainous Regions of Western Macedonia and the City of Kastoria”, serves as an innovative digital guide based on Mixed Reality (MR) and Location-based augmented reality (AR), utilizing mobile devices. It was designed to guide visitors to points of cultural and environmental interest, providing personalized information and interactive experiences (see Figure 18).

Figure 18.

Introductory images of the application environment «Virtual Guide».

In the Prehistoric Lakeside Settlement of Dispilio, the application was utilized and piloted as a digital virtual guide, enhancing the educational visit with multimedia and three-dimensional content. The students were guided to selected points within the archeological site, where virtual elements were activated:

- historical and archeological information,

- 3D models of objects, findings, and constructions,

- audio narratives and storytelling by avatar characters,

- videos related to the topic,

- VR portals, or “gates,” that allow users to immerse themselves in 360° virtual scenes,

- markerless AR models, capable of being placed in the physical space.

Participants walk among the huts of the prehistoric era, while around them, three-dimensional representations, videos, and avatar characters come to life, narrating stories from the past (see Figure 19). Each point becomes a gateway to knowledge, where the real landscape meets the digital world, and learning transforms into discovery.

Figure 19.

Sample images from the app «Virtual Guide»: (a) 3D models, (b) AR portal, (c) virtual tour guide avatar.

5.5. Virtual Reality (VR) Applications

Furthermore, in addition to the aforementioned applications of mixed and augmented reality, students have the opportunity to wear Oculus glasses and fully immerse themselves in virtual reality (VR) experiences.

Through the specialized glasses, the students are transported to a digitally reconstructed environment of the prehistoric lake settlement. Depictions of individuals, animals, and artifacts of the era contribute to a sense of realism and movement, offering a unique opportunity for students to experience the daily life of the prehistoric inhabitants as if they were actually there (see Figure 20).

Figure 20.

Sample images from the app «Video 3D».

Within the virtual landscape of the video, the settlement’s area is brought to life:

- The huts are positioned on stilts within the lake, reflecting the architecture of the settlement.

- People are depicted engaging in daily activities such as fishing, cooking, tool-making, etc.

- Animals move through space, capturing the interaction between humans and the environment.

- Objects and tools are presented in a manner that highlights their materials and potential uses.

This experience acts not just as a visual illustration, but it also transforms the student into an active observer of history. The immersion provided by the Oculus glasses enhances the sense of presence, creating the impression that the visitor is within the prehistoric settlement itself.

An additional application, 360° Drone View—“Through the Eyes of a Bird,” offers students the opportunity to explore the area of the Lakeside Settlement of Dispilio from a unique perspective. With the assistance of Oculus glasses, participants can ‘fly’ over the area, enjoying panoramic views throughout all seasons: the snow-covered winter landscape, the lush green landscapes of spring, the radiant light of summer, and the ambiance of autumn.

The 360° panoramic images create a virtual tour video in which students can rotate their view in all directions, observe the changes in the landscape over time, and connect the natural environment of the lake with its historical significance (see Figure 21).

Figure 21.

Sample images from the app «360° Drone View» Representative images from the “360° Drone View” app.

Beyond the pleasure of aesthetics, the experience provides considerable pedagogical value:

- students become familiar with the geographical location of the settlement,

- they recognize the strategic importance of the lake and its surroundings,

- and they gain a better understanding of the conditions under which the prehistoric community developed.

Digital applications of virtual reality perfectly complement mixed and augmented reality applications, providing a holistic learning approach that combines research in the real world, interaction with digital elements, and complete immersion in the virtual realm.

6. Evaluation

During the academic year 2024–2025, a total of 163 students from elementary schools, middle schools, and high schools participated in the educational program “Prehistoric Lakeside Settlement of Dispilio.” The students’ impressions and experiences from their involvement in the educational activity were evaluated using a well-structured questionnaire, grounded in the current literature [11,92,108,109,110,111,112], with the objective of capturing quantitative data.

The questionnaire consisted of thirty questions (Table A1), of which four pertained to the demographic information of the students, four addressed the organization of educational activities, two open-ended questions related to what the students enjoyed the most and what was lacking in the educational program’s activities, while twenty questions focused on the evaluation of XR digital applications.

The twenty questions designed to evaluate XR digital applications were assessed on a 5-point Likert scale (where 1 means strongly disagree and 5 means strongly agree) and focused on six categories: “challenge”, “satisfaction/enjoyment”, “ease of use”, “usefulness/knowledge”, “interaction/collaboration”, and “intention to reuse”.

To be precise, the “challenge” category encompassed 3 questions that depicted the emotions a student experiences as they engage with the games (proud, pleased, excited, etc.) at the initiation of the educational activity. The “satisfaction/enjoyment” category featured 3 questions that examined the extent of satisfaction and enjoyment among students during the educational activity. The category of “ease of use” (4 questions) focused on the usability and familiarity of the specific digital applications, the effort exerted by the students, and the level of assistance or guidance they may have required in order to operate the applications. The category titled “usefulness/knowledge” (3 questions) involved evaluating the usefulness of digital applications for educational aims, their effectiveness in enhancing users’ knowledge about the prehistoric lake settlement, and, in a broader sense, prehistory. The “interaction/collaboration” category consists of three questions that mirror the degree of collaboration fostered among students throughout the experience, along with the incentives offered by the digital application for user cooperation. In conclusion, the category “intention to reuse” (4 questions) evaluated the intent to reuse digital applications or similar ones with either related or different subject matter (Table A1).

7. Results

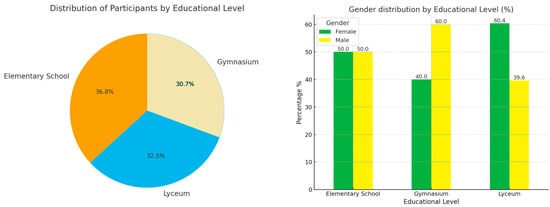

7.1. Demographic Statistics and Educational Activity

From the total of 163 pupils in primary and secondary education who took part in the educational program “Prehistoric Lakeside Settlement of Dispilio,” 81 were male, and 82 were female. To be precise, the total comprised 60 pupils from Primary School, 50 from Secondary School, and 53 from High School (see Figure 22).

Figure 22.

Gender and educational level of participants.

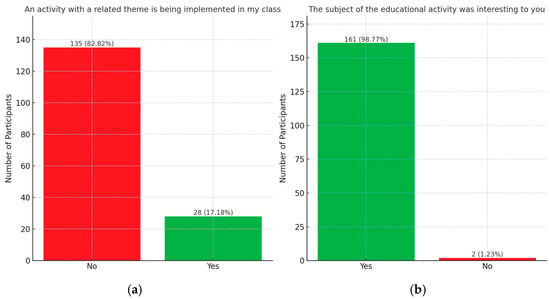

Among the participants, only 28 students (17%) had engaged in activities related to the program’s theme at their school prior to their involvement in the educational program of the Education Center for the Environment and Sustainability (E.S.E.C.) of Kastoria, while the majority (99%) indicated that the educational program piqued their interest (see Figure 23).

Figure 23.

(a) Implementing an activity with a relevant topic in the classroom, (b) Evaluation of the educational activity regarding the interest of its thematic focus.

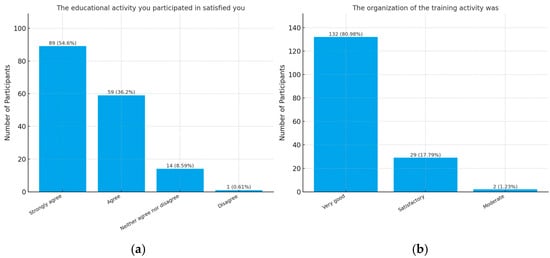

The organization of the educational activity was deemed successful by the participating students, with 132 students (81%) indicating that it was very good, 29 students (18%) rating it as satisfactory, and only 2 students (1%) stating that it was average.

The educational activity fully satisfied the majority of participants, with 55% and 36%, respectively, indicating that they were “very satisfied” and “satisfied” (see Figure 24).

Figure 24.

(a) Evaluation of the organization of the educational activity, (b) Evaluation of the educational activity in terms of the satisfaction it provides to the participants.

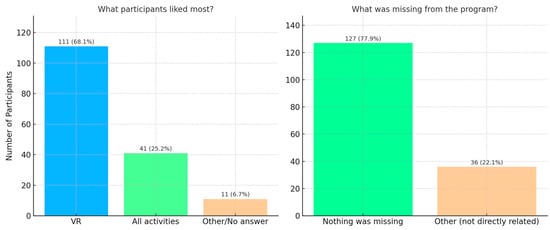

In response to the open-ended question, “What did you enjoy most about the activities of the educational program?” 111 students (68%) indicated that their favorite aspect was the VR experience, while 41 students (25%) stated that they enjoyed all the activities. The remaining 11 students (7%) either did not respond or provided varied individual answers. To the inquiry, “What do you think was lacking in the educational program?” 127 students (78%) responded that there was nothing absent from the educational program, while the remaining 22% offered comments that did not pertain directly to the educational program (see Figure 25).

Figure 25.

Assessment of what participants enjoyed the most from the educational program’s activities, along with what was missing.

According to the above, the educational program generated significant interest among the participants (almost 99% found it engaging) and satisfied them to a very high degree (over 90% agreed or strongly agreed), while its organization was rated as ‘very good’ by the overwhelming majority (81%). However, only 17% engage in related activities in the classroom, highlighting the necessity to enhance the practical integration of the educational program within the school context. From the open-ended questions, it is evident that the most favored element was VR (68%), while 25% appreciated all activities equally, highlighting the appeal and diversity of the educational program. Additionally, most respondents (78%) reported that nothing was missing, corroborating that the program was considered to be complete and fully developed.

7.2. Data Analysis and Achievement of Research Objectives

To analyze the data and achieve the research objectives, a series of steps was followed, which are described below.

7.2.1. Reliability Analysis (α Cronbach) and Descriptive Statistical Analysis

The responses of the participating students to the evaluation questions regarding the XR digital applications were analyzed for their internal reliability using Cronbach’s alpha, employing SPSS software version 23.0, and demonstrated excellent internal reliability with a value of a = 0.912. All categories/scales demonstrated satisfactory internal reliability (a > 0.7), including “challenge” (a = 0.749), “satisfaction/enjoyment” (a = 0.862), “ease of use” (a = 0.714), “usefulness/knowledge” (a = 0.774), “interaction/collaboration” (a = 0.731), and “intention to reuse” (a = 0.774).

The descriptive statistical values for the six categories mentioned and the questions included are illustrated in Table 1. The average values of the cumulative scales for the six categories are obtained by summing the values of the relevant questions and dividing by the number (count) of questions in each category. Based on the analysis shown in Table 1, and taking into account that the assessment ratings for the questions were on a 5-point Likert scale (1–5), it can be concluded that the mean values of the individual questions were quite high (M > 4.15). The average values are correspondingly high (>4.30) in all categories, suggesting that XR digital applications were broadly embraced and generally generated positive emotions and experiences for the participants.

Table 1.

Mean scores, standard deviation.

In particular, an analysis of the average values and standard deviations for each category, as illustrated in Figure 26 and Table 1, led to the following conclusions about the participating students.

Figure 26.

Mean scores and Standard Deviation of constructs.

- Challenge (M = 4.41, SD = 0.53): The responses were generally positive and relatively homogeneous, with minimal variation. The participants felt that the XR digital applications sparked their interest and provided satisfaction.

- Satisfaction/Enjoyment (M = 4.33, SD = 0.64): Participants exhibit a wider range of views concerning the impact of XR digital applications on knowledge enhancement, although the average perspective remains favorable. A number of participants may have considered the XR digital applications to be either less enjoyable or more enjoyable; however, the average evaluation remains elevated.

- Ease of use (M = 4.37, SD = 0.43): The responses were predominantly focused on the positive perspective that XR digital applications were user-friendly. The low standard deviation signifies that most participants had a uniformly positive experience.

- Usefulness/Knowledge (M = 4.30, SD = 0.58): A high and relatively uniform score indicates that collaboration and interaction were among the strengths of the XR digital applications, with few discrepancies in the responses.

- Interaction/Collaboration (M = 4.45, SD = 0.47): A consistently high score reflects that collaboration and interaction were significant strengths of XR digital applications, with only a few deviations in the responses.

- Intention to reuse (M = 4.33, SD = 0.63): There is a broader spectrum of views, but the general direction is optimistic. Some participants may not be as inclined to repeat the XR digital applications (M = 4.15, SD = 1.04); however, they generally exhibit a strong willingness to engage with similar digital applications featuring related or different themes.

7.2.2. Normality Testing and Data Correlations

The corresponding values of skewness and kurtosis (Table 2) in the specified categories fall within the acceptable range of −2 to +2, as per George and Mallery (2010). This indicates that the distributions are relatively symmetrical, do not exhibit significant deviations from normality, and are suitable for parametric tests.

Table 2.

Values for asymmetry and kurtosis.

The Pearson correlation coefficient (r) was chosen for testing the correlation between the six categories. The Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated to examine the relationship between the categories: challenge, satisfaction/enjoyment, ease of use, usefulness/knowledge, interaction/collaboration, and intention to reuse of digital applications. The findings are displayed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Correlations between constructs.

According to Table 3, all correlations are statistically significant at the p < 0.01 level, with a sample size of N = 163.

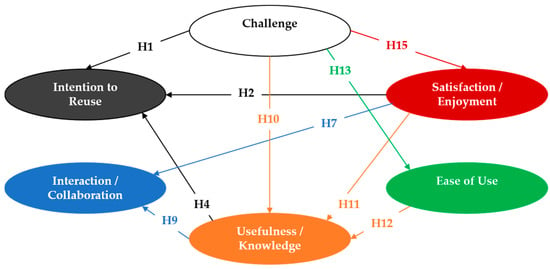

The Pearson analysis revealed strong positive correlations between Challenge and the variables of Satisfaction/Enjoyment (r = 0.688), Usefulness/Knowledge (r = 0.591), and Intention to Reuse (r = 0.603). Additionally, it showed moderate correlations with Ease of Use (r = 0.333) and Interaction/Collaboration (r = 0.384). The variable Satisfaction/Enjoyment showed significant correlations with Usefulness/Knowledge (r = 0.649) and Intention to Reuse (r = 0.651), whereas moderate correlations were noted with Interaction/Collaboration (r = 0.482) and Ease of Use (r = 0.320).

The Ease of Use demonstrated a moderate correlation with Usefulness/Knowledge (r = 0.428) and weak correlations with the variables Interaction/Collaboration (r = 0.294) and Intention to Reuse (r = 0.274). The Usefulness/Knowledge demonstrated a strong positive correlation with the Intention to Reuse (r = 0.648) and a moderate to strong correlation with Interaction/Collaboration (r = 0.525). Finally, the Interaction/Collaboration was associated with the Intention to Reuse with a moderate correlation (r = 0.479).

Overall, the most significant associations were noted between the variables Challenge, Satisfaction/Enjoyment, Usefulness/Knowledge, and Intention to Reuse, creating a coherent pattern of positive relationships in the assessment of the XR experience.

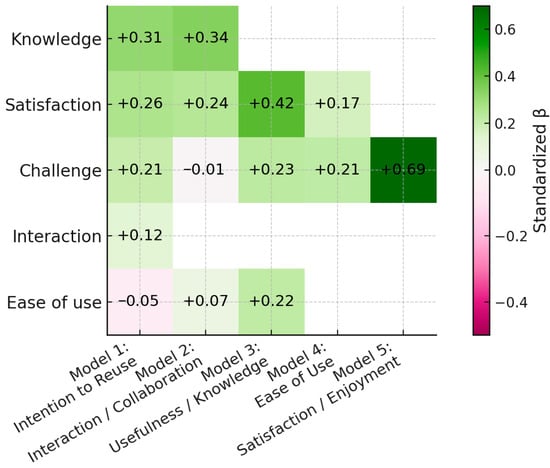

7.2.3. Multiple Regression Analysis

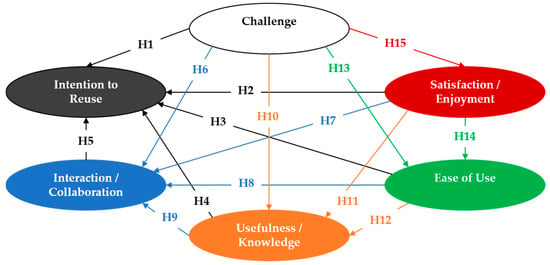

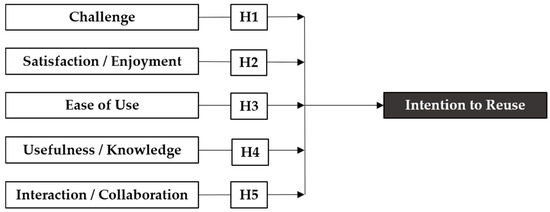

In order to better explore the relationships among the categories, a series of multiple regressions was conducted based on a conceptual framework with hypothetical associations (H1 to H15) between the six categories, as illustrated in Figure 27.

Figure 27.

Hypothetical Correlations: A Conceptual Framework for Multiple Regression Analysis.

The initial multiple regression analysis (H1, H2, H3, H4, H5) was conducted to investigate the correlation between intention to reuse as the dependent variable and the other categories as independent variables, as illustrated in Figure 28.

Figure 28.

Conceptual Framework for Multiple Regression Analysis with Intention to Reuse as the dependent variable.

According to the values presented in Table 4, multiple regression demonstrated a strong statistical correlation between the independent variables and the dependent variable (Intention to Reuse). The multiple coefficient R = 0.737 indicates a strong level of linear relationship, while the R2 index = 0.543 shows that approximately 54.3% of the variance in the intention to reuse is associated with the five variables of the model (Challenge, Satisfaction/Enjoyment, Ease of Use, Usefulness/Knowledge, Interaction/Collaboration).

Table 4.

Model Summary 1 (Dependent Variable: Intention to Reuse).

The further analysis of model 1 based on the values in Table 5 revealed that three out of the five categories were statistically significant. Specifically, the variable Usefulness/Knowledge (β = 0.312, p < 0.001) demonstrates the strongest positive correlation with the Intention to Reuse, followed by Satisfaction/Enjoyment (β = 0.262, p = 0.002) and Challenge (β = 0.206, p = 0.008). Conversely, the factors Ease of Use (β = −0.048, p = 0.424) and Interaction/Collaboration (β = 0.124, p = 0.060) did not demonstrate a statistically significant relationship with the Intention to Reuse at the significance level of p < 0.05, although the latter variable shows a marginally positive trend.

Table 5.

Coefficients (Model 1, Dependent Variable: Intention to Reuse).

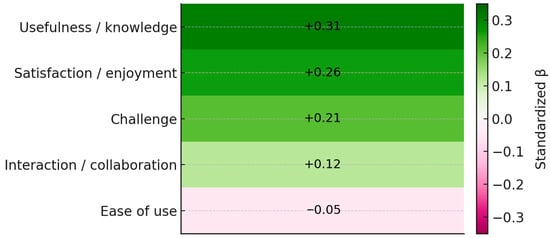

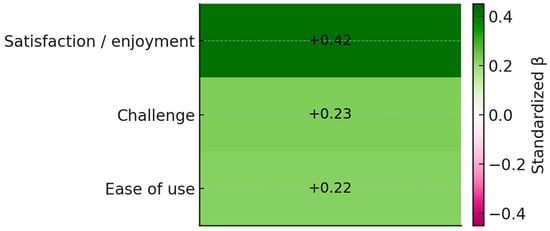

In conclusion, the hypothetical correlations H4, H2, and H1 are favored, while H5 and H3 are rejected, as clearly illustrated in the heat map in Figure 29.

Figure 29.

Heat map of standardized regression coefficients (Model 1, Dependent Variable: Intention to Reuse).

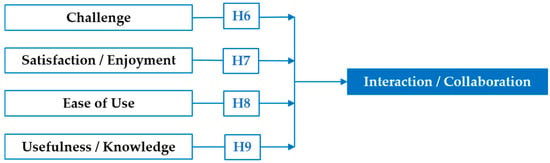

The second multiple regression analysis (H6, H7, H8, H9) was conducted to investigate the correlation between interaction/collaboration as the dependent variable and the categories of challenge, satisfaction/enjoyment, ease of use, and usefulness/knowledge as independent variables, as illustrated in Figure 30.

Figure 30.

Conceptual Framework for Multiple Regression Analysis with interaction/collaboration as the dependent variable.

According to the values presented in Table 6, the multiple regression analysis indicated that the model comprising four independent categories exhibits an overall moderate positive correlation with Interaction/Collaboration, (R = 0.561, F(4, 158) = 18.141, p < 0.001), accounting for approximately 32% of its total variance (R2 = 0.315, Adjusted R2 = 0.297).

Table 6.

Model Summary 2 (Dependent Variable Interaction/Collaboration).

The further analysis of model 2, based on the values presented in Table 7, revealed that two out of the four categories were statistically significant. Specifically, the usefulness/knowledge (β = 0.341, p < 0.001) is positively correlated with interaction/collaboration, as well as satisfaction/enjoyment (β = 0.245, p = 0.015). At the same time, the categories of ease of use (β = 0.073, p = 0.318) and Challenge (β = −0.010, p = 0.915) did not demonstrate a statistically significant relationship with interaction/collaboration Reuse at the significance level of p < 0.05.

Table 7.

Coefficients (Model 2, Dependent Variable: Interaction/Collaboration).

In conclusion, the hypothetical relationships H9 and H7 are favored, while H6 and H8 are rejected, as clearly illustrated in the heat map in Figure 31.

Figure 31.

Heat map of standardized regression coefficients (Model 2, Dependent Variable Interaction/Collaboration).

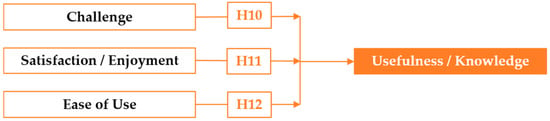

The third multiple regression analysis (H10, H11, H12) was conducted to investigate the correlation between usefulness/knowledge as the dependent variable and the categories of challenge, satisfaction/enjoyment, and ease of use as independent variables, as illustrated in Figure 32.

Figure 32.

Conceptual Framework for Multiple Regression Analysis with Usefulness/Knowledge as the dependent variable.

According to the values presented in Table 8, the multiple regression analysis indicated that the model comprising three independent categories demonstrates a significant positive correlation with usefulness/knowledge (R = 0.709, F(3, 159) = 53.441, p < 0.001), accounting for approximately 40% of its total variance (R2 = 0.502, Adjusted R2 = 0.493.

Table 8.

Model Summary 3 (Dependent Variable Usefulness/Knowledge).

The further analysis of model 3, based on the values presented in Table 9, indicated that all three categories were statistically significant. Specifically, ease of use was positively correlated with usefulness/knowledge (β = 0.217, p < 0.001), as well as satisfaction/enjoyment (β = 0.422, p < 0.001) and challenge (β = 0.228, p = 0.004).

Table 9.

Coefficients (Model 3, Dependent Variable: Usefulness/Knowledge).

In summary, the hypothetical relationships H10, H11, and H12 are prioritized, as depicted clearly in the heat map shown in Figure 33.

Figure 33.

Heat map of standardized regression coefficients (Model 3, Dependent Variable Usefulness/Knowledge).

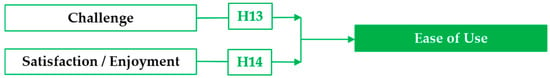

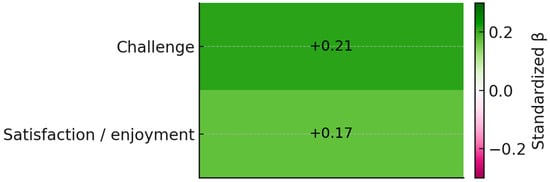

The fourth multiple regression analysis (H13, H14) was conducted to examine the correlation between ease of use as the dependent variable and the categories of challenge and satisfaction/enjoyment as independent variables, as illustrated in Figure 34.

Figure 34.

Conceptual Framework for Multiple Regression Analysis with Ease of Use as the dependent variable.