Abstract

The article proposes a concept for a mobile robot designed to detect hazardous and explosive materials in airport parking lots. The problem with operating such a robot is twofold. Firstly, it must move in a dynamic environment, between vehicles that are parked or also in motion, but without stopping vehicles that are in motion. The second problem is the detection of hazardous and explosive materials. For robot mobility solutions, an obstacle analysis system based on popular, low-cost LIDAR sensors and cameras was proposed. For the detection of hazardous and explosive materials, a dual vehicle monitoring system was proposed for airport parking lots. The first is based on vision techniques, where cameras and image recognition procedures are used to examine the undercarriages of parked vehicles. This system is designed to detect unusual objects mounted on vehicle undercarriages. The second is based on the analysis of volatile substances produced by explosives and hazardous materials found under or inside car chassis and gasoline and oils. The aim of the project is to develop a functional prototype of such a robot and describe its capabilities. The article describes the preliminary findings of the research.

1. Introduction

In today’s highly urbanized world, automated systems improving safety must play an increasingly important role. The advancement of mobile robotics technologies has significantly contributed to improving safety in industrial, warehouse, and transportation environments where the risk of exposure to hazardous materials is present. In this context, mobile ground robots (MGRs) play a crucial role in inspection and monitoring systems, enabling autonomous or semi-autonomous detection of chemical, toxic, and explosive threats while minimizing risk to human operators [1,2]. Explosive materials mounted beneath vehicles, including so-called sticky bombs and improvised explosive devices (IEDs), pose a significant threat to public safety due to their concealability and catastrophic consequences of detonation [3,4]. In response to this threat, a variety of detection and inspection technologies have been developed for vehicle undercarriage scanning, including radar, magnetic, and vision-based systems that enable the identification of structural anomalies [5,6]. Ground penetration radars (GPRs), often integrated with mobile platforms or aerial drones, allow for rapid scanning of vehicle undersides and the detection of concealed explosive materials without exposing operators to direct risk [7]. The development of mobile robots, such as inspection platforms deployed in China and other countries for undercarriage control at checkpoints, airports, and government facilities, has significantly improved the efficiency of such operations. These robots support high-resolution visual inspection and can be equipped with additional chemical or magnetic sensors [6]. The deployment of mobile inspection robots not only the rapid identification of potential threats, but also a substantial reduction in risk to personnel [7,8]. Mobile ground robots are used in various areas of security. Under Vehicle Inspection Systems (UVIS) enable the inspection of vehicle undercarriages, detecting hazardous materials or hidden objects [9]. Issues similar to those described in this study, related to robot threat detection, also appear in the field of rescue operations (medical, chemical). For example, gas or toxic substance leaks are monitored, with data transmitted to crisis management centers [1]. In warehouses and industrial facilities, mobile platforms autonomously navigate operational spaces, identifying chemical hazards, and supporting safety management processes [2]. Mobile ground robots are characterized by a modular design, and their construction system comprises three main modules: the mobility module, the sensory module, and the computational module. The mobility module enables the robot to move through various environments and can be implemented using traditional wheels, tracks, or omnidirectional wheels that allow movement in any direction without rotating the entire vehicle. Such solutions are essential in confined spaces, such as during under-vehicle inspections or in narrow industrial corridors [1,2]. The authors in [10] present an advanced control system for a four-wheeled mobile robot designed for autonomous obstacle avoidance under motion uncertainties. As part of their research, they developed the Obstacle-Circumventing Adaptive Control (OCAC) method, which integrates adaptive control with a dynamic target tracking algorithm. The test robot featured a maximum driving speed of up to 2 m/s, the ability to overcome obstacles up to 30 cm in height, and maneuverability with a turning radius ranging from 0.3 to 0.5 m, enabling effective navigation in complex environments. The experimental results demonstrated high stability of the system, rapid adaptation of the trajectory, and robustness against disturbances, making the solution promising for applications in inspection and industrial robotics. The sensory module integrates various detection technologies, including sensors for toxic gases and volatile chemicals, RGB cameras, thermal imaging cameras, and hyperspectral sensors, enabling real-time detection, classification, and localization of hazardous substances. Additional support may come from distance sensors, such as LIDAR, which facilitate obstacle avoidance and mapping of the operational environment. Example sensor parameters include RGB camera resolutions ranging from 1 to 5 MP at 30–60 fps, thermal cameras with resolutions of 160 × 120 to 320 × 240 pixels and temperature ranges from −20 °C to 150 °C, hyperspectral sensors covering 50 to 200 bands in the 400–1000 nm range and gas sensors capable of detecting concentrations in the ppm–ppb [11,12]. The computational module serves as the central data processing system and includes processors, operational memory, and computational algorithms. Its main tasks include analyzing sensory data, classifying threats, planning trajectories, and communicating with the operator or supervisory systems. Modern robots utilize deep learning algorithms to detect HAZMAT signs and identify hazardous materials in complex operational scenarios. An example of advanced architecture is the “Brick” concept, in which sensory, mobility, and computational modules operate autonomously and communicate wirelessly. This approach allows for independent upgrades or replacements of modules, scalable system configuration based on operational requirements, and increased resilience to single-component failures [2,13]. The article [14] presents the concept of a mobile inspection robot designed to monitor explosion-prone environments such as mines or industrial areas. This robot, developed by the Industrial Institute for Automation and Measurements and the Institute of Innovative Technologies, is equipped with appropriate sensors for gas concentration measurement, cameras, a transmission system, control, and visualization systems. Its mobility and ability to operate in harsh conditions make it a valuable tool for detecting and monitoring hazardous substances in industrial environments. A similar approach has been applied in other mobile robot projects aimed at detecting hazardous materials. For example, the Hazardous Materials Emergency Response Mobile Robot (HAZBOT), developed by NASA, is a mobile rescue robot designed to respond to emergencies involving hazardous substances. The latest designs of CBRN/HAZMAT robots are based on integrated perception systems that combine various types of sensors: from optical and thermal cameras to gas sensors and gamma and neutron radiation detectors. The UGV-CBRN project [15] exemplifies a modern approach, incorporating LiDAR, radiation sensors, a manipulator, and trajectory planning algorithms, enabling semiautonomous reconnaissance and sample collection tasks. Similar conclusions are presented in the report by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security [16], which emphasizes the importance of multifunctional platforms (Multifunctional Unmanned Ground Vehicles, MUGV) in ensuring the safety of responders during interventions. The literature analysis indicates that the main research trends in the field of hazardous material detection by mobile robots include the following: Expansion of autonomy—transitioning from full teleoperation to semiautonomous and autonomous systems capable of real-time mapping [7,16]. Advanced data analysis methods—employing deep learning and artificial intelligence techniques for symbol recognition, threat source identification, and contamination spread prediction [6]. Multi-sensor integration—combining chemical, biological, radiological, and optical sensors into a unified perception system [5,15]. Interoperability—adapting robots to existing rescue procedures and safety standards [17,18]. A typical example of a mobile inspection robot designed in China for inspection in high-security operational environments is the ZA-UVBOT-I [19]. The device features a compact design that allows efficient maneuvering in confined spaces, which is particularly important when inspecting hard-to-reach vehicle components [7]. The robot is equipped with an electric drive powered by a battery, providing adequate speed, mobility, and extended operating time without frequent recharging. Its sensory systems include high-resolution cameras and LED lighting for precise observation under various lighting conditions, and optionally sensors capable of detecting hazardous materials [5,15]. An intuitive control interface enables smooth platform operation and real-time data analysis. Due to these features, the ZA-UVBOT-I is used in critical infrastructure locations such as checkpoints, airports, fuel stations and government facilities, supporting preventive and inspection activities by increasing efficiency and reducing risk to personnel [16]. In the article [20], the authors analyze the role of the ‘car bomb’ as a means of distributing explosive charges against transportation infrastructure, particularly metro stations, railway terminals, and airports, and document that such attacks represent a significant and persistent threat to passenger infrastructure. Statistical analysis covering incidents in metro systems indicates a high vulnerability of these facilities to explosions delivered via vehicles, as well as a diversity of delivery methods, which the authors classified and ranked according to threat level. Based on this classification, the “car bomb” was identified as one of the highest-risk methods in the context of public transportation. The conclusions emphasize the need to integrate preventive systems (infrastructure design, mechanical barriers, monitoring) with risk analysis and continuous testing of protective solutions in real-world conditions to effectively reduce the vulnerability of transport networks to such events. In a global analysis of terrorist acts targeting metro systems (with the study period extending from the late twentieth century to the early twentieth century, and data cited up to 2015). The structure and severity of threats posed by IEDs and the methods used to deliver them to transport facilities. According to the authors, IEDs accounted for a significant portion of incidents in the analyzed sample, approximately 35% of all metro-related events, with around 17% of these cases involving vehicles (that is, car bombs). In terms of humanitarian impact, the authors note that car bomb attacks were associated with a high number of casualties: the median/average losses in such incidents were significantly higher than for other attack methods, with reported figures reaching dozens of fatalities (averaging over 50 deaths per incident in the most lethal cases) and hundreds of injuries (around 200) in the most powerful explosions at transport hubs. The authors also document a temporal trend: an increase in vehicle-based attacks after the year 2000, with a rise in incidents in conflict-affected regions (including the Middle East and South Asia). This increase is described as over 40% compared to previous decades.

Based on the analysis of existing solutions, it can be indicated that the solutions currently used and developed in the form of target applications do not constitute comprehensive systems for detecting threats in facilities such as parking lots. This article describes mobile inspection robots designed to detect hazardous and explosive materials in airports. These robots are intended to operate in various task configurations. They are organized into swarms depending on current needs or the context of an emergency situation at the airport. The swarm concept involves the use of several universal mobile platforms (Waveshare), which are configured according to operational requirements. The functionality of the robots is modified based on changes in the spatial and functional characteristics of the monitored airport. Robots are intended to detect hazardous and explosive materials, as well as fuel leaks and other consumables from road vehicles that may pose safety risks at the airport. It is important to note that IEDs are also constructed using diesel fuel. The functionality of the mobile robots presented in this paper has been investigated in the context of their deployment at civilian and military airports. The article also describes the design and intended operation of the management and control system for these robots. Beyond airport environments, the proposed mobile robots and their management system can be applied to large public parking areas, such as those surrounding supermarkets, multiplex cinemas, and similar facilities. Their use becomes particularly relevant during mass events, where increased vehicle activity and a high degree of heterogeneity in vehicle accumulation patterns are observed. Operating these robots in real time within such dynamic environments, characterized by the presence of vehicles and their users, poses a significant research challenge. This is especially true for autonomous navigation systems, which will be addressed in future publications. In this paper, we focus on presenting the robots themselves, their core functionalities, and the foundational assumptions for their management system.

In this study, we present three distinct types of mobile robots, each designed with varying levels of physical, technical, and cost-related complexity and equipped with different embedded software configurations. Robots range from the simplest and smallest units, tasked with the preliminary identification of potentially hazardous objects, to more advanced systems responsible for verifying and confirming the presence of actual threats. Most of the robots developed in this project utilize the most affordable components available on the market, resulting in unit costs ranging from €100 to €200. These include selection robots (also referred to as sniffers) and vision-based robots. Additionally, a specialized robot is under development, priced significantly above €1000, which will be described in detail in a separate publication. However, this price point remains competitive compared to similar systems currently available. A key aspect of the proposed system is the synergy between all types of robots, both within individual categories and across them. The specialized robot is designed to validate the findings of the selection and vision-based robots, ensuring a reliable threat assessment process.

2. Threat Detection System

The proposed incident detection system comprises three key elements. The first is the system’s structure, divided into components responsible for specific tasks. The second area of system performance analysis involves determining threat potential based on assumed and developed probabilities. The third element of the system involves hazard recognition based on the adopted classification of both hazardous materials and objects with significant potential threat.

2.1. Description of System Components and Structure

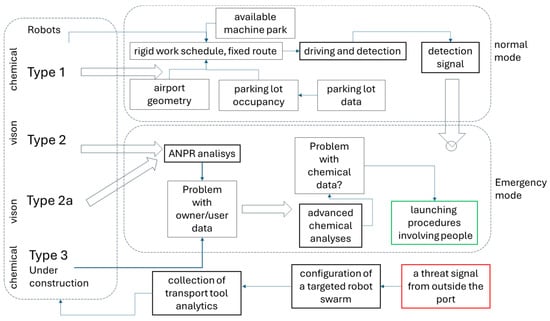

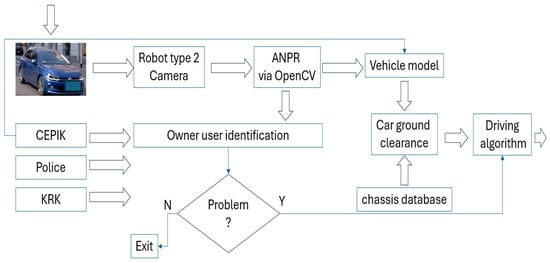

The previously described selection robots enable the detection of hazardous substances or those commonly associated with the presence of explosives (e.g., compounds released during the decomposition of dangerous materials). These robots use simple and inexpensive environmental sensors characterized by low power consumption, typically in the range of several tens of milliamps. This design choice addresses the power supply challenge posed by the long distances these robots must travel between airport parking areas, which can span several or even over ten kilometers. These robots are used to monitor airport parking areas as part of routine inspections of the airport and its surroundings, following fixed routes and work schedules. They can also be deliberately grouped into task-oriented swarms in response to an identified emergency situation (e.g., a terrorist threat alert, usually originating from external security agencies rather than airport personnel). This requires intentional changes to their routes and schedules. Upon detection of a potential threat source by level 1 robots, higher-tier robots (levels 2 and 3) are summoned to carry out further actions in emergency scenarios, such as identifying hazardous substances or verifying discrepancies in vehicle license plates or other unusual events. These higher-category robots are equipped with technical means for image capture and processing using vision-based techniques (level 2, referred to as vision robots). They help determine additional context related to the results of the selection procedures. Initial sniffing robots operate based on chemical analysis of the surrounding air, while level 2 vision robots identify vehicle license plates using Automated Number Plate Recognition (ANPR) technology and can navigate under the vehicle to inspect the undercarriage for suspicious objects that may be explosive devices [21,22,23]. The ANPR system allows verification of the registration data of vehicles flagged as potentially dangerous by the sniffing robots, cross-referencing them with databases maintained by relevant authorities, such as Poland’s Central Vehicle and Driver Registry (CEPIK) or police and national security agencies like Internal Security Agency (ABW). If a vehicle is stolen or registered with individuals flagged in national security databases as potentially dangerous or linked to terrorist activity, this significantly raises the priority level of the threat analysis procedure at the airport. These robots are also intended for use in passenger terminals and baggage handling areas, although this will be addressed in a separate publication due to the specificity of the topic. The undercarriage inspection performed by the vision robot involves comparing the actual image of the vehicle’s underside with a reference model from a database of known vehicle structures. The vehicle model is determined through ANPR analysis and is linked to catalog data from reference databases. This vision-based inspection allows the detection of unusual objects attached to the vehicle’s undercarriage. The system also assesses the mounting context of the identified object, namely whether it is a typical aftermarket component not installed by the manufacturer in that specific model. The vehicle model is determined using ANPR, and the system can also detect deliberate changes in the plate. If anomalies are found between the visual inventory and the reference data, a specialized robot is deployed. This robot is equipped with significantly more advanced environmental sensors and is an order of magnitude more expensive than the others (level 3, environmental robot). This robot is not described in this article. The general system operation scheme is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

General system operation diagram.

The operation of the management system for these three types of robots can be divided into three modes. Mode 1 refers to the regular work schedule, in which level 1 robots perform daily monitoring based on predefined routes and fixed work schedules covering airport parking areas (the schedule is linked to the number of vehicles parked at the airport). This mode will be described separately due to the interesting context of modeling the movement of such robots within a spatially nonuniform facility like an airport. In this mode, a suspicious object may be detected during routine operations along a strictly defined route, which triggers the activation of level 2 and possibly level 3 robots, if the probability of a threat is assessed to be sufficiently high.

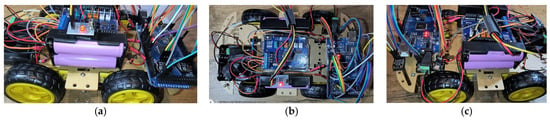

There is also an incidental swarm mode, which is activated in the event of a real threat and aims to quickly search large areas of the airport in the shortest possible time. This mode typically applies when threat information originates from external sources, such as law enforcement or security agencies, for example, reports of terrorists or other suspicious individuals present at the airport. In such cases, fixed schedules and routes are not used; instead, the swarm is concentrated in designated areas using a purposeful structure (topics related to ML and AI are discussed in subsequent publications). This is not about using standard patrol procedures with robots organized in a three-level hierarchy, but rather about optimizing the swarm so that it can search the suspected threat area as quickly and thoroughly as possible. It is important to note that an explosion near an airport, even if it does not pose a major threat to large groups of people, can cause significant smoke and disrupt airport operations for hours, leading to operational chaos. Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 presents three robots representing models of types 1, 2, and 3. Such a targeted concentration or dispersion of the swarm can also be used to create a radio barrier that prevents the remote detonation of explosive devices. In this case, the sniffing robots emit noise in specific radio frequency bands.

Figure 2.

Robot models used, type 1: (a) right side; (b) top view; (c) left side.

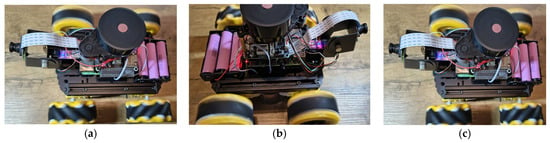

Figure 3.

Robot models used, type 2: (a) right side; (b) top view; (c) left side.

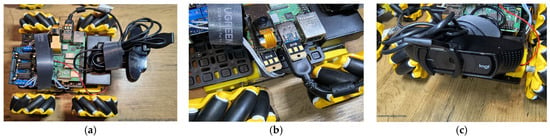

Figure 4.

Robot models used, type 3: (a) right side; (b) top view; (c) left side.

As shown in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4, there are three types of robots: sniffers, vision-based robots, and chemical robots. However, within type 2 (vision-based), there are various technical series of these vehicles, differing in functionality. An important design issue in the developed robots is the durability of the drive wheels operating in diverse environments. This topic is discussed in more detail in the publication [24]. Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 below demonstrate the components of each robot type.

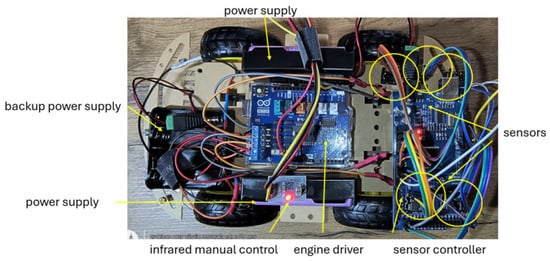

Figure 5.

Identification of components of robot type 1.

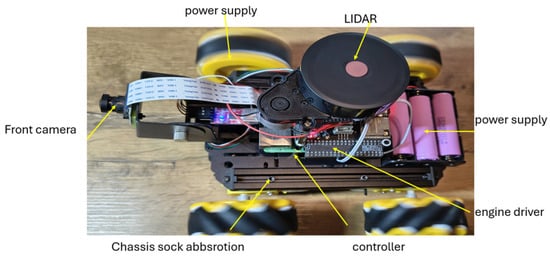

Figure 6.

Identification of components of robot type 2.

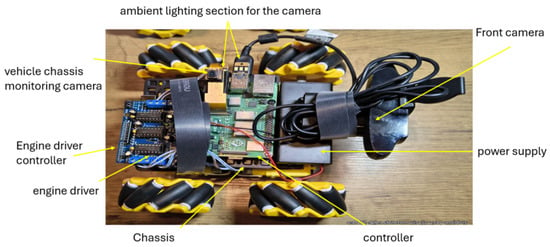

Figure 7.

Identification of components of robot type 3.

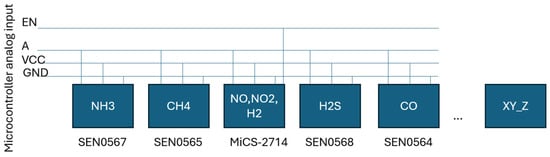

Figure 8 shows the connection of commonly used environmental sensors to popular microcontrollers via their analog pins. This setup allows for the connection of up to 16 sensors using, for example, the Arduino Shield—Extension Board Sensor V2, Mega 2560. This configuration is sufficient for most applications.

Figure 8.

Robot sensor diagram.

2.2. Incident Probability

The probability of an incident (such as an explosion or terrorist attack) is primarily calculated on the results of analyses performed by robots operating within individual swarms. External data sources are also used for this purpose. In the first step of the methodology, the so-called chemical probabilities are calculated. The selection robot vehicle is equipped with a set of n sensors. Each sensor has a detection range from a to b ppm for a specific substance or group of substances. It is assumed that the upper limit of the scale corresponds to exceeding permissible values (since the sensor no longer detects beyond that point). A given sensor that detects a substance classified as hazardous or associated with explosive materials registers a level c within the range of a to b. Therefore, the probability of a threat for each sensor is determined as follows (1):

For n sensors operating in a given configuration on a single sniffing robot, the total probability of a threat is calculated as follows (2):

The robot equipped with a camera (vision-based, type 2) is dispatched in response to a potential threat identified by environmental sensor measurements from a sniffing robot. Based on visual analysis, it determines whether there are objects attached to the vehicle’s undercarriage that do not belong to the original structure. In the case of the sniffing robot, the threat is identified through the concentration levels of hazardous substances. Let us pose a relevant question: what determines the level of threat in this case? First, the size of the object. Large foreign objects attached to the undercarriage may indicate a large payload. If we correlate the size of the payload with its destructive power, which is true in most cases, then this becomes a key factor. Any visible wires or electronic components on the surface of the object further increase the likelihood that it is an explosive device. Another factor is the location of the object’s placement; certain areas of the undercarriage allow for the mounting of heavy payloads. These probabilities can be defined as follows (3):

The probability of detecting a large, mounted payload is calculated as follows, where S1 denotes the surface area representing the payload, determined by OpenCV image processing using OpenCV and converted to square meters [m2]; S denotes the undercarriage surface area suitable for mounting a payload [m2].

In practice, robots will use databases to estimate these probabilities. It can be cautiously assumed that no more than one payload will be placed under a single vehicle, so the probability is modified by the location of the payload. This probability increases with distance from the edge of the vehicle and in proximity to mounting points (4).

where de denotes the mounting distance from the nearest edge (determines the visibility of the payload from the outside); d denotes the maximum mounting distance from the nearest edge; pfix denotes the probability associated with the presence of potential mounting points for heavy payloads, reflecting the feasibility of attaching such payloads (values: 0.1, 0.2, … 1.0).

The next probability factor arises from the recognition of typical components associated with electrical and electronic systems on the body of the suspended object, such as wires, diodes, and other electronic elements. This measure reflects the complexity of the payload. Appropriate HAAR classifiers are used to identify these components. The probability is calculated using Formula (5):

where L1 denotes the number and count of categories of electronic components identified in the image [-]; L denotes the maximum number of categories aggregated in reference databases of explosive device components, considering their spatial packing.

After the initial identification of a potential incident threat, a specialized chemical robot is deployed to assess the probability using more precise sensors equipped with independent probes (factory-calibrated heads). Therefore, the probability is calculated as shown in Equation (6), but here we will refer to it as

Based on the data obtained from mobile robots operating in three interdependent swarm sniffers, visionaries, and recorders, the probability of an incident involving an explosion threat is determined using Formula (7):

It should be noted that we also have access to license plate readings, which can be used to refine the probability of an incident. Information about the vehicle owner from central databases such as CEPIK, as well as data from security services, can help validate the threat. These can be supplemented with data from airport and national security systems. The probability of an incident based on informational data is expressed as Equation (8):

where pANPRP denotes the probability of an incident resulting from comparing the license plate with data from CEPIK and law enforcement or other security databases; pAP denotes the probability of an incident based on data from airport security services; pCOUNTP denotes the probability of an incident based on data from national security services.

Therefore, the probability of an incident is calculated as in Equation (9):

As mentioned above, to avoid false alarms, more than one vision robot and a specialized chemical robot can be dispatched to the location of the identified threat. Therefore, Equation (10) becomes

where e denotes the number of specialized environmental robots dispatched to the location, and f denotes the number of specialized vision robots dispatched to the location.

In such a procedure, beyond the standard routine inspection schedule, critical incident cases are of particular importance. In these situations, based on the available information, it is necessary to inspect the threat areas in the shortest possible time. This introduces the issue of optimization of operation time, which can be achieved, among other methods, by optimizing the movement paths of individual swarm components across the airport area, as well as optimizing the structure of each swarm.

2.3. Hazardous and Explosive Materials

The inspection robots of the first and third levels should be able to identify threats based on the analysis of the available chemical information. Level two robots rely on geometric data and references stored in domain-specific databases. In the first case, threat recognition primarily involves detecting trace amounts of hazardous volatile substances. According to the classification adopted in the EU, hazardous substances are divided into the following categories from National Research Institute:

- H1–H2: acutely toxic substances;

- H3: substances with toxic effects on target organs—single exposure;

- P1a: explosive materials;

- P2: flammable gases;

- P4: oxidizing gases;

- P5a, P5b, and P5c: flammable liquids;

- P6a, P6b: self-reactive substances and organic peroxides;

- P7: pyrophoric solids and liquids;

- P8: oxidizing solids and liquids;

- E1, E2: hazardous to the aquatic environment;

- O1: substances or mixtures with hazard statement EUH014;

- O2: substances and mixtures that release flammable gases upon contact with water;

- O3: substances or mixtures with EUH029 hazard statement.

Among the categories listed above, the most relevant for fire safety in airport parking areas are P1a, P2, and P5a–c. In this context, the ability to detect potential fire (or explosion) threats during continuous vehicle monitoring (system mode 1) is critical.

Unlike hazardous substances, an explosive charge consists of a substance (either chemically homogeneous or a mixture) capable of a rapid exothermic chemical reaction accompanied by the release of a large volume of gaseous products in the form of an explosion (detonation or deflagration), along with other components such as a detonator. The oldest known explosive material used by humans is black powder, which still finds various applications today. The initiation of an explosive reaction occurs with the application of a stimulus—mechanical, thermal, electrical, or chemical. In some cases, high-energy electromagnetic radiation (e.g., intense light) is sufficient to trigger the explosion. The practical use of an explosive material requires the preparation of an explosive charge, which consists of three basic components: the explosive material itself, an initiating element, and a casing that integrates them into a single unit. The most dangerous explosive materials include brisant explosives, such as picric acid, trinitrotoluene (TNT), nitroglycerin, dynamite, and hexogen (RDX) [25]. These materials are characterized by extremely rapid detonation (short reaction time), resulting in the highest destructive force.

In vehicles equipped with internal combustion engines, which still represent the largest group of vehicles, the most common cause of fire is a leak in the fuel system. Leaking fuel poses a significant hazard, as elevated temperatures and, for example, a spark from electrostatic discharge are sufficient to cause ignition. Therefore, detecting fuel system leaks is crucial from a safety point of view. Leak detection involves confirming elevated concentrations of hydrocarbon mixtures, which rise in the form of fuel vapors around the vehicle with a compromised fuel system. All flammable and easily ignitable liquids are classified in categories P2 as well as P5a, P5b, and P5c. In the case of motor vehicles, these are primarily fuels (both liquid and gaseous). An additional group of hazards includes flammable substances that may leak from systems such as air conditioning.

3. Threat Detection Methods Used in the Designed System

The proposed threat recognition system relies on specialized robots. Different types of threats require different recognition strategies. The proposed system utilizes three main methods: image analysis, chemical compound analysis, and their combined use.

3.1. Chemical Technique

Explosive material detection is the process of identifying the presence of explosives using detectors that analyze solid particles and vapors of substances in the environment. The most widespread detection methods are based on Ion Mobility Spectrometry (IMS), which uses ionization followed by ion separation in an electric field to identify substances. Another commonly used method is Raman spectroscopy, a technique that uses laser light to identify chemical substances based on their unique spectral signatures [26,27].

Type 1 robots use inexpensive MEMS-series sensors. Within this product line (e.g., Fermion), there are currently 11 different types of gas sensors available. These sensors qualitatively detect substances such as HCHO, CO, CH4, VOCs, NH3, H2S, EtOH, smoke, odor, H2, NO2 [28]. These sensors can be combined into sets depending on the application. In this case, the sensors provide only qualitative measurements. These robots are designed solely to establish an initial probability of the presence of hazardous substances. If a threat is identified with higher probability, type 2 and type 3 robots are deployed. Type 3 robots are capable of performing highly accurate quantitative measurements using factory calibrated sensors. Unfortunately, these sensors are significantly more expensive, often an order of magnitude higher than those used in type 1 robots. In this case, the cost of a Type 3 robot exceeds €1000. An example of such a sensor is the Gravity series 400.

3.2. Vision Technique

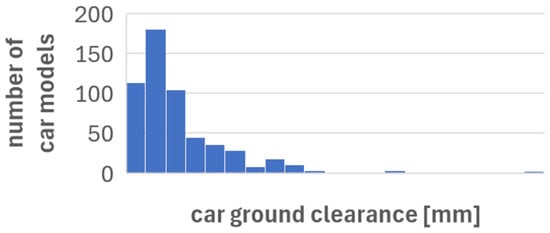

Type 2 robots respond when type 1 robots detect the presence of hazardous substances or those associated with explosive materials. When elevated values of the measured characteristics are observed, type 1 robots initiate procedures to summon type 2 robots. Using vision-based techniques, type 2 robots assess potential threats based on whether the vehicle owner has been identified. For this purpose, national data resources such as CEPIK are used. Secondly, based on the identification of the vehicle model, the body type is determined and the physical space and reference images of the undercarriage plates are identified for the operation of type 3 robots. These robots are slightly more expensive than type 1 and must not be exposed to damage. Therefore, it is important to assess the parameters of the inspected vehicle, such as ground clearance and areas prone to hazardous substance leakage that could affect the robot. To support this, a catalog of vehicle undercarriages with images is prepared and continuously expanded. This catalog provides guidance for type 2 robots on which undercarriage elements pay special attention in terms of potential explosive devices. In particular, it helps determine the clearance available for the robot, where it should not enter, and why, for example, to avoid damaging the vehicle, malfunctioning, or being flooded. Assuming the possibility of inspecting the undercarriages of all vehicles using the airport parking area, the robot design must account for various clearance ranges. The smallest clearances are found in sports cars designed for track driving. The minimum clearance for city cars is typically around 14–15 cm, which allows safe navigation over curbs and other obstacles. This range is acceptable for type 1 and type 2a robots.

Popular passenger vehicles, such as SUVs, usually have higher clearance values (around 20 cm), similar to off-road vehicles, and these parameters are acceptable for all robot types. Example clearance values by vehicle class are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Ground clearance of selected road vehicle type.

In addition to factory-standard vehicle versions, user-modified versions can also be encountered, where ground clearance has been altered outside of manufacturer specifications. An analysis of ground clearance values for popular vehicle models from various manufacturers, with a maximum allowed total weight of up to 3.5 tons, is presented in the following chart. The analysis is based on technical data from 550 vehicle models (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Statistical analysis of the ground clearance values of vehicles with a total weight of up to 3.5 tons.

In the field of vision-based techniques for detecting unusual objects, a vehicle owner identification module is used. For this purpose, the camera of a type 2 robot captures the vehicle’s license plate data. To identify the owner or user of the vehicle, a vision-based technique from the OpenCV library called ANPR is applied. This serves to answer several key questions. First and foremost: What is the type of vehicle model? This information also provides data on ground clearance and procedures that determine the following questions: How can the robot navigate safely under the vehicle without damaging itself or the vehicle? How should it behave if the vehicle is started or begins to move while parked?

Second, by connecting to the CEPIK database and other databases held by national security services, the vehicle owner is identified. This individual may also appear in central registries such as Interpol, which can help assess potential threats posed by the vehicle owner. The vehicle may be listed on stolen vehicle registries, increasing the risk level, or may have altered license plates, which can be detected with a certain probability. All of these factors contribute to determining the probability of a threat in each individual case. Calculations of the probability of a terrorist incident are presented in this article as part of a procedural method. The analysis scheme using vision-based techniques is illustrated in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Analysis diagram using vision techniques.

3.3. Notes on Environmental Robots

The Sniffer robots, during their analysis, examine the air composition beneath vehicles located in the parking area(s) under investigation. Any detection of hazardous substances or explosive materials triggers the deployment of specialized robots. These robots can operate based on the license plate numbers of vehicles associated with the incident. Alternatively, they can act on hazardous substance density maps developed within the central swarm management system, using data transmitted by the sniffer robot units.

By utilizing these density maps or identifying vehicles classified as potential threats, the specialized robots can search not only by license plate numbers but also navigate using concentration density maps prepared specifically for them. Based on references from these maps, they move using the A algorithm, which relies on pre-established heuristics. These heuristics take into account the type and location of the threat, as well as the spatial layout of airport infrastructure and access roads. In cases where sniffer robots confirm the likelihood of an incident, such as elevated concentrations of substances cataloged as hazardous or related to explosives, specialized robots are dispatched to the scene of the incident. Among these are robots equipped with visual detection technologies and robots with advanced environmental sensors.

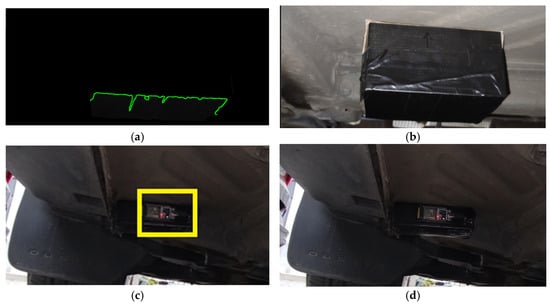

3.4. Mixed Detection

To avoid errors, both visual- and chemical-type robots are organized into micro-swarms, which enhance the reliability of detecting hazardous substances or explosive materials. Initial operations are carried out by visual robots. One of them first reads the license plate data using ANPR technology, if the plate is available. Based on this reading, information about the vehicle’s owner or user is determined and incorporated into the overall procedure. The vehicle may also be identified by specific distinguishing features. At the same time, to save time, another visual robot begins analyzing any objects attached to the vehicle undercarriage that deviate from the standard appearance of the vehicle model’s undercarriage, as determined from the ANPR-based license plate reading. Background extraction techniques are used in this process. This is illustrated in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Visual techniques for extracting objects from the standard background representing the factory vehicle undercarriage: (a) object detected using background feature subtraction, (b) original photo, (c) object detected using HAAR feature-based methods, (d) original photo.

Figure 11b,c show the original image of a simulated explosive device magnetically attached to the undercarriage of a test vehicle. One image presents a black box simulating an explosive charge (b), while the other depicts a device simulating an explosive equipped with electronic components, including light-emitting elements (d). Figure 11a shows a processed image using simple background feature subtraction, revealing the presence of a suspended object. This method produces an image of elements attached to the vehicle undercarriage. The result of this process is presented in Figure 11. Figure 11c,d demonstrate the application of Haar-based procedures. In this case, Haar cascades are used to identify all elements that match the image patterns of various electronic systems. Visual robots operate on wheels equipped with Mecanum wheels, allowing them to maneuver under the vehicle from any angle. Given the known sensitive components integral to the undercarriage structure (e.g., brake lines) for a specific vehicle model, this enables trajectory planning that avoids damaging any part of the inspected vehicle while also reducing inspection time.

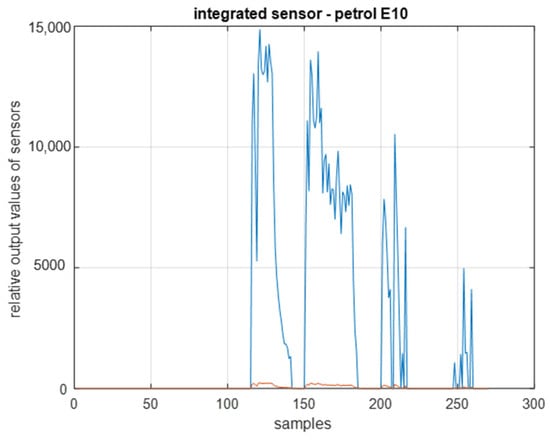

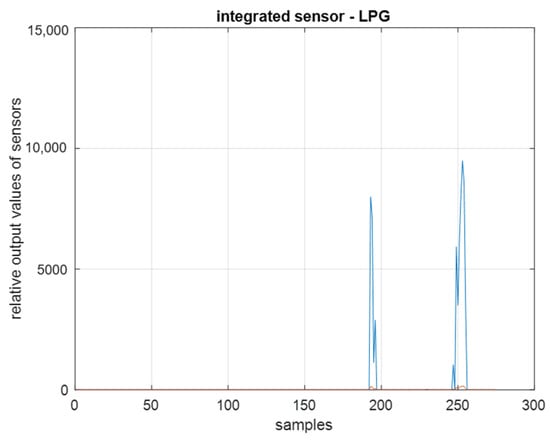

A specific challenge from the perspective of airport and aviation security is the case of vehicles filled with explosive material. These are often vans, where visual and chemical techniques may fail. The material, which varies from tens of kilograms to several tons, fills the opaque and sometimes sealed interior of the vehicle, preventing the substance from escaping in detectable quantities. In such cases, the inspection of the suspension element becomes relevant. The goal is to verify how heavily loaded the vehicle is. This involves examining the condition of visible suspension components, which may indicate a heavy load in the cargo area (assuming the vehicle does not use hydraulic suspension). The visual robot may also assess vehicle load externally by analyzing the correlation between the upper edge of the fender and the tire outline, and the differences between the drive and non-drive axles. Additionally, the robot can examine the axial alignment on both axes using visual techniques based on the overall contour of the vehicle. Simultaneously with the visual robot, an environmental robot equipped with professional chemical sensors operates. These robots enter beneath the vehicle involved in the incident and analyze the chemical composition of the air under the vehicle, with particular attention to areas of potential substance attachment or leakage. Sample signals from the chemical sensors of type 1 robots are shown in Figure 12 and Figure 13.

Figure 12.

Results of environmental measurements in the parking area, with deliberately introduced gasoline pollutants—data from the MISC sensor. Blue indicates CH4, red indicates NH3.

Figure 13.

Results of environmental measurements in the parking area, with deliberately introduced pollutants in the form of LPG—data from the MISC sensor. Blue indicates CH4; red indicates NH3.

As can be observed in the charts presenting the results of successive recorded samples during fuel leaks, only changes in the readings for methane and ammonia are visible.

4. Robot Sensors

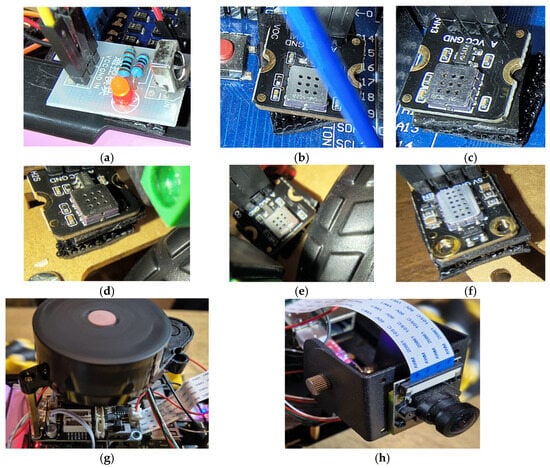

In type 1 robots, inexpensive so-called qualitative sensors are used (as described by the manufacturer DFRobot, Shanghai, China). This economical approach is justified by the large number of type 1 robots required, which depends on the area covered by a given airport and the spatial structure of its terminals. It is important to note that terminals can sometimes be significantly spaced apart. Such a cost-effective solution helps keep the overall cost of the system as low as possible, especially when operations involve hundreds of these robots. For the construction of robots, sensors from DFRobot’s Gravity and Fermion series were selected (https://www.winsen-sensor.com, accessed on 21 September 2025) [28]. The first sensor is designed to detect volatile organic compounds (VOCs): VOC—MEMS, DFRobot SEN0566. This sensor enables qualitative measurements of VOC concentrations in the air, with a detection range from 1 to 500 ppm. The manufacturer estimates the module’s lifespan at approximately 5 years, similar to the other sensors presented here. Why is the lifespan of the sensor important? Type 1 robots are expected to operate continuously, both in open environments (exposed to weather conditions) and under vehicle undercarriages, where they may encounter various chemical compounds. For this reason, protective covers with servomechanisms have been designed for robots. In addition to air monitoring, this sensor can also be used for fire detection. The next sensor is a methane (CH4) sensor—MEMS DFRobot SEN0565, with a detection range from 1 to 10,000 ppm. Its estimated lifespan is also around 5 years, and it operates at low current consumption (~20 mA). Another sensor detects nitrogen dioxide (NO2)—MEMS DFRobot SEN0574, with a measurement range of 0.1 ppm to 10 ppm. It is used to monitor vehicle emissions and detect toxic gas leaks in industrial processes. The next sensor detects ammonia (NH3)—MEMS DFRobot SEN0567—with a detection range from 1 ppm to 300 ppm. Like the previous sensors, it consumes less than 20 mA and has an estimated lifespan of 5 years. Another module is a multi-gas sensor for NO, NO2, and H2—MEMS MiCS-2714, DFRobot SEN0441—capable of detecting hydrogen (H2) in the range of 1 ppm to 1000 ppm, and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) from 0.05 ppm to 10 ppm. The carbon monoxide (CO) sensor—MEMS DFRobot SEN0564—detects CO concentrations in indoor environments within the range of 5 ppm to 5000 ppm. The hydrogen sulfide (H2S) sensor—MEMS DFRobot SEN0568—is designed to measure H2S concentrations from 0.5 ppm to 50 ppm. It is used in underground detection and industrial monitoring of large-scale facilities. The final sensor is a hydrogen (H2) sensor—MEMS DFRobot SEN0572—with a detection range of 0.1 ppm to 1000 ppm. Figure 14 presents all sensors used in the project, not only the environmental ones.

Figure 14.

Photos of the sensors used in robot type 1 and 2: (a) PIR, (b) VOC, (c) Nh3, (d) H2S, (e) CO, (f) MISC, (g) LIDAR, (h) Camera.

In the area of forward-field detection for the robot, a wide range of LiDAR devices are used. One example is the Wave share D200 360° 8 m laser LiDAR scanner (model 24659). This is a low-cost laser scanner based on ToF (Time-of-Flight) technology, priced under €60 in 2025. It performs measurements at a defined frequency with a detection range of up to 8 m and communicates via a UART interface. A slightly more expensive option is the RPLIDAR A2M8, which operates in a 360-degree range. This laser scanner performs 4000 measurements per second and has a detection range of up to 12 m. For airport parking areas (excluding main roads), these detection distances are sufficient. The measurement error for this type of device is approximately 0.1%, and its cost does not exceed € 300. The IR sensor shown in Figure 14a is used for manual control of the robot, outside marker-based navigation and autonomous driving modes. In general, the system includes four types of robots, each with different chassis configurations and equipment. Additional components include GPS modules and data loggers.

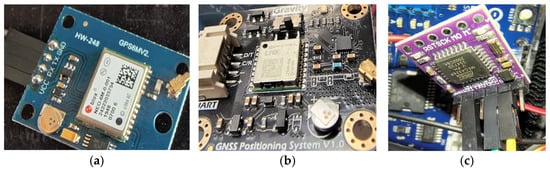

The GPS system is used to record the positions of robots for possible spatial reconfiguration (in threat mode) and to identify hazardous locations. It is also used to configure a radio barrier that prevents the remote detonation of explosive devices. Additionally, in robots equipped with cameras, visual references are created to enable sequential monitoring of the surroundings in potentially dangerous areas.

Two GPS modules are used for this purpose, both offering positioning accuracy of less than two meters (verified through control tests using fixed spatial references and GIS systems). The first module is the GY-NEO6MV2 GPS communication module with an external antenna. It communicates via a UART interface, with a supply voltage of 3.3–5 V and a logic voltage of 3.3 V. The second module is the Gravity GNSS GPS BeiDou receiver—DFRobot TEL0157—which supports multisystem positioning: BeiDou, GPS, and GLONASS. It offers high precision and faster performance compared to traditional GPS positioning. The data logger shown in Figure 15c records the position readings of the selection robot and sensor output for archival purposes. This enables the creation of reference maps to compare natural background concentrations around the parking area with incidental ones. Procedures for robot management based on archival data will be presented in a separate article.

Figure 15.

Additional equipment: (a) GPS, (b) Glonass, (c) Beidu.

In summary, the operation of robots at the airport is organized on several levels. The first level of swarm organization consists exclusively of the so-called sniffer robots (type 1). Their task is to preliminarily identify potentially hazardous areas within the airport and its immediate surroundings. It is important to note that an explosion that occurs outside the airport but near the runway can pose a direct threat to air traffic.

The second level includes a swarm of specialized robots of types 2, 2a, and 3, which intervene on request from type 1 robots, in coordination with data recorded by the airport’s robot management system. Each robot type uses entirely different techniques and serves different purposes. The algorithm for simultaneous search and deployment of all robot types relates to the creation of an ad hoc spatially distributed swarm. This procedure is activated when a threat signal originates outside the airport, not from type 1 or type 2 robots, but from national security systems. For example, a report may indicate that a vehicle carrying an explosive device is located in a specific parking area or that a terrorist is present in a terminal. Such threats are sudden and require urgent intervention, involving the search of large areas within a limited time frame. To address this, a swarm is formed with a structure and a number of units optimized to verify the threat as quickly as possible. Robot movement control is implemented in several ways. The project includes two levels of control for mobile robots of types 1 to 3. The first level, used during testing, involves infrared (IR) control. This mode is used exclusively for testing, where robots move according to commands issued by an operator using an IR remote or via WiFi/Bluetooth. In the latter case, control is performed via a mobile app. Alternatively, during scheduled operations, a fixed route is defined along precisely marked paths (surface and side markers), and the robot may use line-following or marker-tracking procedures. However, this limits the flexibility of the proposed solution. Ultimately, full autonomy will be implemented using LiDAR sensors and cameras, as seen in robots of types 2 and 3a. At this stage, LiDAR sensors are installed on Type 2 and 3a robots. Achieving full autonomy is challenging due to the dynamic environment in which the robots operate. Robot movement must account for the movement of vehicles, pedestrians, and airport infrastructure, especially in parking areas. On the apron, it must also consider the specialized service vehicles used for aircraft operations.

5. Research Results

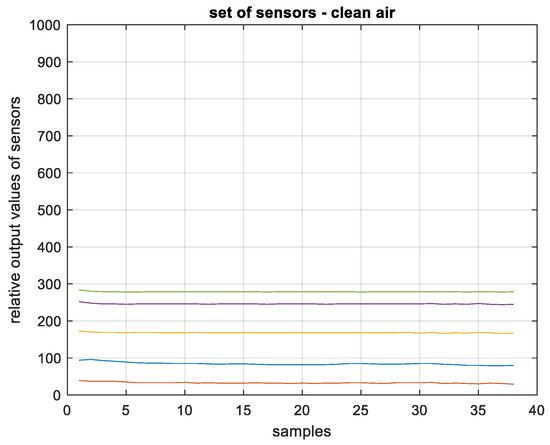

To verify the functionality of the type 1 robot, experiments were conducted in an airport parking area. The robot was deployed to several specific locations around selected vehicles where the emission of hazardous substances is likely to occur. The first stage of the test involved checking sensor readings while the robot operated in a neutral zone, clean air, without artificially introduced chemical agents. The results obtained from the MiCS sensor showed values equal to zero. For the remaining sensors used by the robot to detect threats, the results are presented in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

Environmental measurement results in the airport parking area under neutral atmospheric conditions. Sensor data are color-coded as follows: CO—blue, NH3—red, H2S—cyan, VOC—violet, CH4—green.

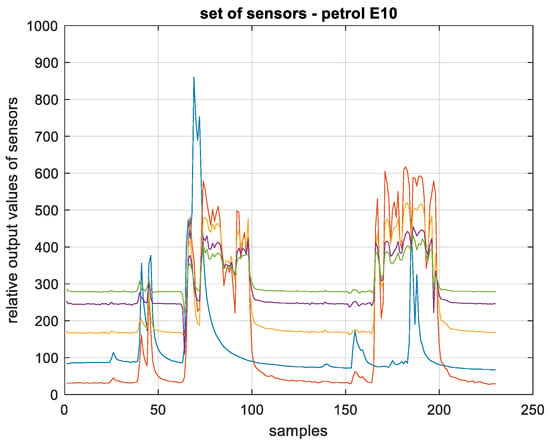

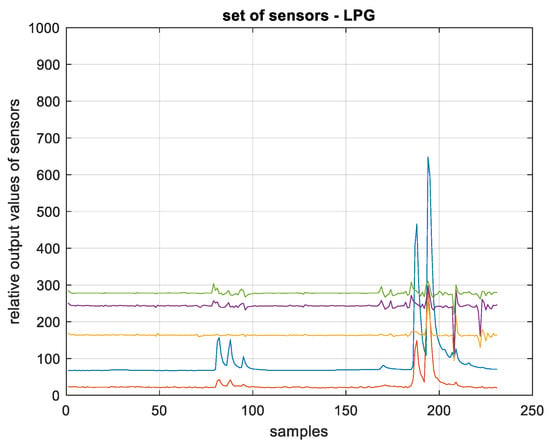

As part of the research, simulated events were conducted that involved fuel leakage. The robot was placed under a vehicle tested in locations similar to fuel line ruptures. Two types of fuel were tested in the simulations: petrol E10 (Figure 17) and LPG (Figure 18).

Figure 17.

Environmental measurement results in the airport parking area with intentionally introduced contamination in the form of petrol (E10). Sensor data are color-coded as follows: CO—blue, NH3—red, H2S—cyan, VOC—violet, CH4—green.

Figure 18.

Environmental measurement results in the airport parking area with intentionally introduced contamination in the form of LPG. Sensor data are color-coded as follows: CO—blue, NH3—red, H2S—cyan, VOC—violet, CH4—green.

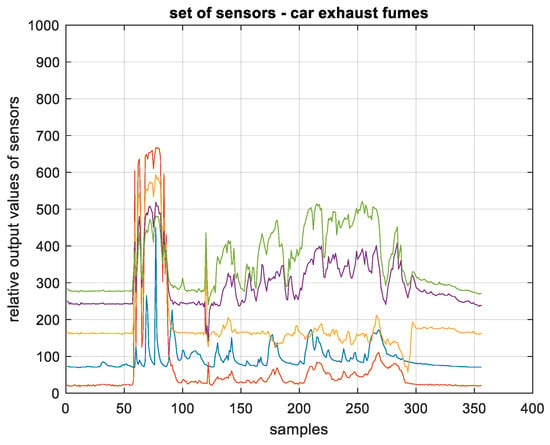

During the investigation, simulated fuel leak events were conducted. All sensors used in the robot responded to the fuels tested. Detection of changes in air composition caused by the presence of flammable or even explosive substances was consistently signaled. Considering that the primary task of this robot module is to detect potential threats without detailed identification, the selected sensors perform their function effectively. An additional test involved evaluating sensor responses to the presence of exhaust fumes, such as those emitted by a vehicle engine that is running while stationary.

Example results obtained from the sensor set during exhaust exposure are presented in Figure 19. High sensor readings were observed when the robot approached the exhaust outlet directly. This can be clearly identified by simultaneously analyzing the image captured by the robot camera.

Figure 19.

Environmental measurement results in the airport parking area with intentionally introduced contamination in the form of exhaust fumes. Sensor data are color-coded as follows: CO—blue, NH3—red, H2S—cyan, VOC—violet, CH4—green.

In cases where alarm-level readings are detected, a procedure can be proposed. According to EU regulations, the operation of a combustion engine while stationary is prohibited for more than one minute. In each test case, based on sensor readings, it was possible to indicate areas within the parking zone where potentially hazardous substances may be present during robot movement. The research experiments and results presented above in Figure 19 aimed at evaluating the functionality of the selection robot (type 1). The goal was to determine whether it fulfills its primary function of identifying potentially hazardous locations. Further studies will examine the impact of spatial distribution of such robots and whether synchronous operation adds value to the analysis. To verify the performance of the type 2 robot, experiments were conducted in the airport parking area. The robot performed several runs through the parking lot to recognize the license plates of selected vehicles. It successfully identified 99.5% of the license plates. Although this is a relatively high result, it is not particularly impressive considering that most of the vehicles were stationary or moving at low speeds regulated by signage within the parking area. Ultimately, this robot must be equipped with a communication interface to access databases, or, more likely, it will transmit the recognized license plate number to a central control and management system, where the data will be verified.

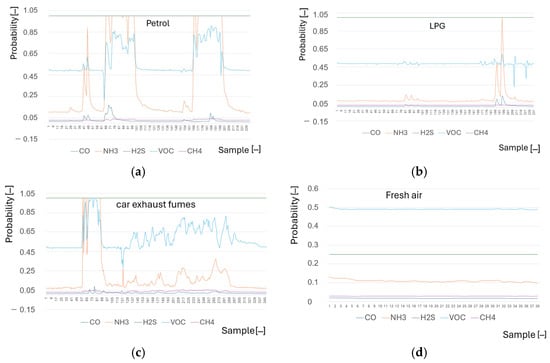

In the scope of hazard identification using rules defined for assessing the probability of a hazardous event, sample results obtained by type 1 robots were developed. The determined probabilities are summarized for the various tested substances in Figure 20.

Figure 20.

Incident probability for: (a) gasoline, (b) LPG, (c) car exhaust fumes, (d) clear air.

Each time, the probability is determined within the measurement range of a given sensor. In this context, exceeding the permissible concentration on a single sensor triggers a hazardous incident. Hence, the proposed method for calculating the probability of an incident. In further work, such a system will be based on appropriate weights. Below (Table 2) are sample results for the analysis, taking into account data from the selection sensors and a vision robot that found a package with the dimensions specified in the table under the chassis.

Table 2.

Example of calculating the probability of an incident.

6. Conclusions

In essence, the tests we conducted indicate the feasibility of identifying potential incident locations at airports using selective mobile robots. Further work will focus on exploring the synergy of swarms of such robots. Efforts will be made to optimize the number of units deployed in operational schedules for airport parking areas of defined capacity or surface area. Despite the use of low-cost environmental sensors in selective robots, they enable a preliminary, coarse assessment of potential hazard zones due to the presence of dangerous or explosive materials. Future research will investigate patterns of hazardous substance concentration distributions detected by these robots using machine learning techniques. Vision-based robots are capable of reading the license plates of vehicles parked in airport parking lots under various lighting conditions, which is often challenging. This task is relatively simple, as the ANPR procedure is applied primarily to stationary vehicles. In addition, selective robots can move beneath parked vehicles and detect objects that simulate explosive devices. Further work will focus on implementing YOLO-based procedures [29,30]. At this stage, detection of potential explosive devices is carried out using either background extraction techniques based on known or unknown vehicle models or via Haar-based procedures. Images of electronic systems potentially used in explosive devices are utilized for this purpose. Thus, the practical functionality of these two types of robots has been demonstrated to identify areas potentially at risk of terrorist incidents or other hazardous situations at airports. Future studies will employ a double-blind test, where the detection team will not be informed which devices are real and which are mock-ups. This lack of knowledge prevents both conscious and unconscious influences on the course and outcome of the study.

Further research will focus on evaluating the functionality of a third type of robot, as well as the development of subsystems for robot navigation, communication, cloud and edge data processing, and swarm configuration. During the development phase, a concept was proposed for deploying minefield-like zones in airports in the event of a terrorist threat. Selective robots that form such zones would generate radio noise using small transmitters to prevent remote detonation of explosive devices [18,31]. A separate type of robot may be developed to monitor radio frequencies and deploy such mine-like zones. This is not a trivial problem due to the conditions of airports in terms of means of communication. In conclusion, security systems are always best tested in practice, not in theory, because practice is its confirmation. The problem of detecting threats in airport parking lots is socially and economically significant. Currently used solutions lack the ability to provide 100% and continuous threat detection. The proposed robotic threat detection system will fill the gap between the needs of improved security and currently used solutions.

In this version, mobile robots have significantly simplified navigation, primarily operating via manual control, wireless infrared control, and line-following (marker control). Vehicle cameras also can follow designated routes. This does not account for the complex dynamics of the airport traffic scene, which is characterized by numerous objects with stochastic motion. This will be the subject of future publications on integrated vehicle navigation based on a dynamic model. This approach should solve many existing challenges in mobile robot navigation, which we will also describe in this upcoming publication.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.C., J.W., T.O.; methodology, I.C., J.W.; software, I.C.; validation, I.C., T.O.; investigation, I.C., J.W., T.O.; writing—original draft preparation, I.C., J.W., T.O.; writing—review and editing, I.C., J.W., T.O.; visualization, I.C., J.W.; supervision, I.C., T.O.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| MGRs | Mobile Ground Robots |

| IEDs | Improvised Explosive Devices |

| GPRs | Ground Penetration Radars |

| UVIS | Under Vehicle Inspection System |

| OCAC | Obstacle-Circumventing Adaptive Control |

| HAZBOT | Materials Emergency Response Mobile Robot |

| MUGV | Multifunctional Unmanned Ground Vehicles |

| ANPR | Automated Number Plate Recognition |

| CEPIK | Poland’s Central Vehicle and Driver Registry |

| ABW | Poland’s Internal Security Agency |

| IMS | Ion Mobility Spectrometry |

References

- Flann, N.; Moore, K.L.; Ma, L. A small mobile robot for security and inspection operations. Control Eng. Pract. 2002, 10, 1265–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.; Page, D.; Koschan, A.; Abidi, M. A “Brick”-architecture-based mobile under-vehicle inspection system. Proc. SPIE-Int. Soc. Opt. Eng. 2005, 5804, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Twumasi, J.O.; Le, V.Q.; Ren, Y.-J.; Lai, C.P.; Yu, T. Roadside IED detection using subsurface imaging radar and rotary UAV. Proc. SPIE 2016, 9823, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevelyan, J.; Hamel, W.R.; Kang, S.C. Robotics in Hazardous Applications; Springer Handbook of Robotics; Siciliano, B., Khatib, O., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Hernandez Bennetts, V.; Schaffernicht, E.; Lilienthal, A.J. Towards gas discrimination and mapping in emergency response scenarios using a mobile robot with an electronic nose. Sensors 2019, 19, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifi, A.; Zibaei, A.; Rezaei, M. DeepHAZMAT: Hazardous Materials Sign Detection and Segmentation with Restricted Computational Resources. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsitsimpelis, I.; Taylor, C.J.; Lennox, B.; Joyce, M.J. A review of ground-based robotic systems for the characterization of nuclear environments. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2019, 111, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, C.; Veras, J.C.; Vidal, R.; Casals, L.; Paradells, J. A sigfox energy consumption model. Sensors 2019, 19, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukumar, S.R.; Page, D.; Koschan, A.; Abidi, M.A. Under Vehicle Inspection with 3D Imaging; W: Advances in image and video technology (ss. 105–116); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Wang, S.; Xie, Y.; Wu, H.; Zheng, S.; Li, H. Adaptive control of a four-wheeled mobile robot subject to motion uncertainties. Front. Mech. Eng. 2023, 18, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosin, P.L.; Lai, Y.K.; Zong, Z. RGB-D Image Analysis and Processing: Trends and Challenges; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz Ulloa, C.; Prieto Sánchez, G.; Barrientos, A.; Del Cerro, J. Autonomous Thermal Vision Robotic System for Victims Recognition in Search and Rescue Missions. Sensors 2021, 21, 7346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.R. A Comparison of the Sensor Brick Concept as a Modular System Architecture for Intelligent Mobile Robotic Systems. Master’s Thesis, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA, 2005. Available online: https://trace.tennessee.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3818&context=utk_gradthes (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Kasprzyczak, L.; Trenczek, S.; Cader, M. Robot for monitoring hazardous environments as a mechatronic product. J. Autom. Mob. Robot. Intell. Syst. 2012, 6, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Schwaiger, S.; Muster, L.; Novotny, G.; Schebek, M.; Wöber, W.; Thalhammer, S.; Böhm, C. UGV-CBRN: An unmanned ground vehicle for chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear disaster response. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.14385. [Google Scholar]

- DHS. Multifunctional Unmanned Ground Vehicles for Emergency Responders. PNNL. [Report]. 2025. Available online: https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/2025-05/25_0520_st_mugvmsr.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- National Fire Protection Association. NFPA 1072: Standard for Hazardous Materials/Weapons of Mass Destruction Emergency Response Personnel Professional Qualifications, 2017th ed.; National Fire Protection Association: Quincy, MA, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.nfpa.org (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- U.S. Department of Transportation. Emergency Response Guidebook (ERG 2024); U.S. Department of Transportation, Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.phmsa.dot.gov/training/hazmat/erg/emergency-response-guidebook-erg (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Available online: https://secuzoan.com/uvbot/1195.html (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Shvetsov, A.; Shvetsova, S.; Kozyrev, V.A.; Spharov, V.A.; Sheremet, N.M. The Car Bomb as a Terrorist Tool at Metro Stations, Railway Terminals, and Airports; Crime Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; Available online: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s12198-016-0177-y.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Chakraborty, A. Real time face detection and recognition system using Haar cascade classifier and neural networks. Inf. Technol. Ind. 2021, 9, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmad, C.; Andrie, R.; Putra, D.; Dharma, I.; Darmono, H.; Muhiqqin, I. Comparison of Viola-Jones Haar Cascade classifier and histogram of oriented gradients (HOG) for face detection. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 732, 012038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Wu, J.; Tang, M.; Xiong, P.; Huang, Y.; Guo, H. Combining YOLO and background subtraction for small dynamic target detection. Vis. Comput. 2025, 41, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorzym, M.; Markuszewski, D. Laboratory tests of rolling resistance of different tread profiles for the wheel of Martian rover. Adv. Sci. Technol. Res. J. 2024, 18, 280–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, I.R.; Daniel, N.W.; Chaffin, N.C.; Griffiths, P.R.; Tungol, M.W. Raman spectroscopic studies of explosive materials: Towards a fieldable explosives detector. Spectrochim. Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 1995, 51, 1985–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenta, S.; Alcalá, M.; Blanco, M. A review of recent, unconventional applications of ion mobility spectrometry (IMS). Anal. Acta 2011, 703, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuehn, M.; Bates, K.; Davidson, J.T.; Monjardez, G. Evaluation of handheld Raman spectrometers for the detection of intact explosives. Forensic Sci. Int. 2023, 353, 111875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winsen Sensor. Available online: https://www.winsen-sensor.com (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Yuan, Y.; Wei, Y.; Zhou, X.; Guo, Y.; Chen, J.; Jiang, T. YOLO-SBA: A multi-scale and complex background aware framework for remote sensing target detection. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Jung, H.G.; Suhr, J.K. BGI-YOLO: Background image-assisted object detection for stationary cameras. Electronics 2025, 14, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanis, M.; Shaheen, E.; Samir, M. The impact of different jamming techniques on OFDM communication systems. Int. Conf. Electr. Eng. 2018, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).