1. Introduction

To respond to climate change caused by global warming, the Paris Agreement has spurred global efforts towards decarbonization, leading to a faster transition to renewable energy. However, the inherent intermittency and volatility of major renewable energy sources such as solar and wind power necessitate the adoption of energy storage systems (ESS) to ensure a stable and reliable power supply. Of many ESS technologies, pumped storage hydropower (PSH) systems are gaining attention as a key energy storage technology for addressing the output volatility of renewable energy sources because they can store large amounts of energy for long periods and have rapid response characteristics [

1,

2].

In order to adapt to the variability of renewable energy output, pumped storage power plants must adopt more improved operating methods than in earlier times. In the past, pumped storage plants primarily utilized surplus electricity during the night to store water in an upper reservoir, and generated power during peak hours to meet surging electricity demand. In recent years, pumped storage plants have faced challenges operating during the week, even when surplus renewable power is abundant, and switching between generating and pumping modes several times a day to balance sudden output fluctuations [

3]. Frequent and rapid switching between operating modes places extreme thermal and mechanical stress on the synchronous motor–generator and core equipment of the pumped storage power system, and this problem has emerged as a significant issue that directly affects the system’s stability and lifespan.

In particular, large motors used in pumped-storage power generation exhibit substantial heat generation due to high current density and electromagnetic losses, while their large internal thermal mass causes significant temperature gradients between components and results in slow thermal response behavior. These thermal characteristics are considerably more complex than those of small motors, making precise and reliable cooling design essential for stable operation. Although pumped-storage systems have relatively few constraints in terms of space and size, allowing for the application of various cooling configurations, high efficiency operation requires an optimized cooling design that maintains internal temperatures below the permissible limits while minimizing the power consumed for cooling. Simply increasing the fan speed or adding excessive internal flow channels may enhance cooling performance, but such approaches increase the power required to drive the cooling system and ultimately reduce the overall generation efficiency. Therefore, a thermal management strategy that balances cooling performance and operational efficiency is crucial for ensuring the reliability and performance of large motors used in pumped-storage applications.

In generator motor design, thermal management is one of the most critical factors determining a generator motor’s performance, efficiency, and reliability. Copper losses in the stator and rotor windings and iron losses in the core generate significant amounts of heat during operation [

4,

5]. In particular, heat from copper and iron losses is significant in high-power applications like pumped-storage power generation, leading to two critical problems due to insufficient thermal management.

Firstly, it shortens the lifespan of the winding insulation system. Rising winding temperature is a major factor that accelerates insulation material degradation, increasing the risk of insulation breakdown and leading to a shorter device lifespan. Typically, electrical insulation systems follow the 10-degree rule, which states that for every 10 °C increase in operating temperature above the permissible level, the lifespan of the insulation is approximately halved [

6]. Therefore, international standards such as IEC 60034-1 [

7] establish strict temperature rise limits for winding types to ensure the reliability of electrical machines, and compliance is a critical consideration from the design stage.

Secondly, recent studies on electric machine technologies highlight that the electromagnetic performance and thermal stability of both synchronous and asynchronous motors are closely interrelated. Heidari et al. [

8] analyzed the latest advancements in the electromagnetic structure and drive technologies of synchronous reluctance motors (SynRMs), emphasizing that thermal management is a key factor in maintaining motor performance. Konuhova [

9,

10] investigated the electromagnetic–thermal interactions that occur in induction motors during voltage sags and direct starting, demonstrating that accurate thermal analysis is essential for ensuring machine reliability.

Elevated temperature also affects the overall electromagnetic performance of electric machines. As temperature increases, the resistance of the windings rises, resulting in reduced efficiency and increased current demand to achieve the same output, thereby increasing total losses [

11]. In addition, the magnetic properties of core materials—such as permeability and iron-loss coefficients—vary with temperature; thus, high-temperature operation accelerates performance degradation by leading to easier magnetic saturation and increased iron losses [

12]. These thermal effects influence not only long-term durability but also short-term output stability. Therefore, in the thermal design of generator motors, maintaining appropriate temperatures in both the windings and the magnetic core is essential, rather than focusing solely on insulation protection [

13].

Since pumped-storage power generation motors generate significant heat during operation, the motors are cooled using a variety of cooling methods, including air and water cooling. Of these, air cooling is a popular choice because it is cost-effective and easy to maintain. Since air-cooled systems offer relatively lower cooling performance than water-cooled systems, a sophisticated thermal design is crucial for optimizing internal flow paths, fan performance, and heat exchange area to fully meet thermal constraints. Ghahfarokhi et al. [

14] conducted an in-depth analysis of the influence of rotor pole shape on cooling efficiency using a steady-state thermal model of a salient-pole synchronous motor–generator. In particular, they confirmed that a salient-pole generator creates a radial airflow circulation effect during rotation, and proposed that this effect can be used as a cooling channel. In a previous study on the optimization of the cooling system for a hydroelectric synchronous motor–generator, Amoresano et al. [

15] and Lee et al. [

16] identified that the layout of cooling ducts critically affected the device’s temperature distribution. To maximize cooling performance utilizing internal flow circulation, a cooling duct was designed to be placed between the stator cores and verified through experiments and 1D modeling.

To verify the cooling performance of an electric motor’s cooling channels, a conventional thermal analysis of electric equipment has been performed using a lumped parameter thermal network (LPTN) model composed of equivalent thermal resistance and heat capacity. Although the LPTN model is fast for calculations, it limits the ability to predict the location of local hot spots or precise temperature gradients [

17,

18]. To overcome these limitations, computational fluid dynamics (CFD) analysis has been used. The CFD analysis allows for the precise calculation of complex internal flow patterns created by the fan rotation, the velocity distribution of the air moving through cooling ducts, and convective heat transfer coefficients at the surface of each component. Therefore, the CFD analysis can be used to verify the thermal validity of a design before it is built and to suggest ways to optimize it.

According to Gammaidoni et al. [

19], a CFD analysis of the overheating in a 250 kW permanent magnet synchronous motor (IPMSM) identified that a loss of airflow through a specific vent in the cooling air conveyor was the root cause. Galloni et al. [

20] used CFD to modify baffle and duct designs for better cooling efficiency by optimizing a motor’s internal airflow, and to eliminate stagnant areas of airflow that interfere with cooling.

Research efforts to enhance convective heat transfer in electric motors through internal fan design and cooling-flow optimization have been actively conducted using CFD-based approaches. However, large generator motors possess highly complex internal cooling passages and multiple solid components—such as the rotating shaft, rotor, windings, stator, and iron core—with intricate solid–fluid interfaces. In addition, medium- and large-scale windings typically exhibit high aspect ratios, requiring extremely fine meshes and substantial computational resources. Consequently, previous conjugate heat transfer (CHT) studies have been largely limited to simplified geometries or small-scale motors [

21,

22]. The thermal behavior of large generator motors arises from strongly coupled multi-physics phenomena: airflow characteristics within the cooling channels, heat conduction in solid components, and heat-flux continuity at all solid–fluid interfaces. Such interactions cannot be accurately captured by single-physics CFD analysis or lumped-parameter thermal network (LPTN) models. Therefore, a comprehensive CHT analysis is essential to reliably predict detailed temperature distributions and local hot spots in large rotating electrical machines.

To overcome these limitations, the present study constructs a full CHT model of a 1 MW generator motor without geometric simplification, capturing the actual geometry of all major components. Since direct simulation of the entire MW-class model requires significant computational cost, the 36° rotational symmetry of the motor was exploited to develop a 1/10 periodic CHT model, enabling a substantial reduction in computational time while retaining the physical fidelity of the full system. Using this computationally efficient framework, a systematic parametric study was conducted by varying key operating and design parameters, including the internal cooling fan height (resulting in different mass flow rates), total heat generation levels (88% of design value), and ambient temperature (26.8–40 °C). Through these analyses, detailed temperature fields, component-wise peak temperatures, and a logarithmic correlation between cooling-air mass flow rate and maximum temperature were quantified.

This approach addresses the limitations inherent in conventional LPTN and single-physics CFD methods, and provides high-resolution thermal predictions across all components of a large generator motor. Furthermore, the results offer valuable insights for the design of cooling channels and casing structures, and provide foundational data for developing thermal management strategies that ensure the long life of winding insulation and stable operation of rotating electrical machines with similar capacities and configurations.

2. Subject and Method of Study

2.1. Geometry and Components of the Analyzed Motor

The subject of this study is a large 1 MW synchronous motor–generator with a rotating shaft of approximately 2.66 m, and the axial and radial cross-sections are shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. As shown in

Figure 1, the radius is about 645 mm, and the interior consists of the seven major components, ordered from the center outwards: rotor shaft, rotor core, rotor coil, insulation layer, stator coil, stator core, and outer casing. In addition, the material, thermal properties and dimensions of each component are summarized in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

The rotor shaft is positioned at the very center of the rotor, serving as the main part that transmits torque and power for rotational motion. The rotor core, made of electrical steel, is positioned around the shaft. The rotor coils are wound around the rotor core in four copper layers. The rotor coils are a major source of heat from copper loss generated during operation.

Due to the nature of rotating machinery, a gap between the rotor and stator is essential. For this reason, the motor used in this study had a radial gap of 11 mm. The air gap is a crucial passage for convection-based cooling, which removes heat generated in the rotor and stator.

The stator coils are arranged on the outside of the rotor and are made of copper. They are also a major heat source by producing considerable heat due to copper loss. The stator core that surrounds the stator coils is made of a laminated electrical steel plate structure. The stator coils are wrapped with insulating material between the coils and the core. In this study, a simulation was performed through a modeling of an insulator filled between the core and coils. An internal core passage with flow guide vanes is installed between the stator core laminates to ensure cooling air flow.

Outside the stator core, the stator core supports are positioned at regular angular intervals to connect the stator core to the outer casing, and their arrangement forms ten external cooling channels created along the stator’s outer wall. The outer casing is the outermost part of the stator that supports the entire structure and manages cooling by channeling air flow.

In this study, a composite heat transfer analysis was performed in this complex structure to simultaneously consider the characteristics of heat generation from copper and iron losses and convective heat transfer of air in the cooling channel. The simulation setup was done by modeling the rotor, stator, and coils as solid domains, and the cooling channel as a separate fluid domain for air flow.

2.2. Cooling Fan Structure and Airflow Path

This motor used an air cooling system where an annular fan mounted on the top of the shaft circulates air through the motor’s internal components. Our motor was designed to have rotational symmetry at 36° intervals around the central axis, and the cooling fan consists of 10 straight blades. Each blade was evenly spaced at 36° intervals in a direction perpendicular to the rotation axis. As shown in

Figure 2a, the fan blades are straight blades that are 70 mm high and 110 mm in chord length.

As shown in

Figure 1, as the motor rotates, the fan attached to its spinning shaft draws in outside air from beneath the motor and channels it through two main airflow paths along the shaft to cool the motor’s components.

The 11 mm radial gap between the rotor and the stator is the first main cooling path for the motor, as shown in

Figure 2b. The gap on the rotor side is the space between the rotor core’s outermost surface and the stator core’s insulation.

An external cooling path for a stator core is another main cooling path formed between the stator core supporter and the outer casing. The axial stator core supporter connects the stator core to the outer casing at 36° intervals, while creating ten cooling paths along the outer wall of the stator core. Outside air is drawn into the external cooling path through two cooling holes, each with a radius of 12.5 mm, located in the radially installed transverse supporter at the lowest end of the stator core.

The gap passage and external cooling passages are connected through the internal passages located between the stacked laminations of the stator core.

Figure 2c represents ten guide vanes installed per cycle in the stator core with internal passages that connect to two main cooling passages to ensure smooth airflow.

Through this flow path, air enters from the bottom, travels axially through the air gap between the rotor and stator, moves over the stator core, is pushed out by a fan and is discharged externally. This study described the fluid domains by focusing on this airflow path, and performed a composite heat transfer analysis by modeling the thermal coupling between solid domains, such as the rotor, stator, casing and their contact points.

2.3. Numerical Model Configuration and Analysis Method

2.3.1. Modeling Process and Interface Configuration

This study performed a conjugate heat transfer (CHT) analysis to precisely analyze the thermal behavior of a large 1 MW generator motor. However, our study model consists of several components including a rotating shaft, rotor, stator, coil, insulation layer, casing, and cooling channels, and the boundaries between the fluid and solid domains are highly complicated. For these reasons, an accurate analysis is challenging with simplified models. To address this issue, the CHT modeling in this study followed a clearly defined modeling workflow to ensure that all solid–fluid interfaces were constructed in a fully conformal manner.

In the first step, the contact surfaces of each component were identified based on the manufacturing drawings, and the geometry was carefully adjusted so that all interfaces shared identical edges and faces. In the second step, individual components were divided into multiple volumes when necessary to accurately reconstruct matching contact surfaces for conformal interface generation. In the third step, all shared faces were verified for consistency before defining the interfaces, and finally, a high-quality conformal mesh was generated while maintaining the integrity of the conformal structure.

Therefore, this study created hundreds of conformal interfaces by carefully adjusting the contact surfaces between solid and fluid domains to maximize the accuracy of a heat transfer analysis at solid–fluid boundaries. Furthermore, this study aimed to improve the numerical stability and physical validity of a large-scale CHT model to overcome previous challenges that made simulations difficult.

Since the target motor had a periodic, repeating axial geometry, as shown in

Figure 3, the entire 360° motor model was simplified to a 1/10 computational domain of the full model. This allowed for computational resources to be saved and the physical behaviors of the whole system to be reproduced. Periodic boundary conditions were applied to its interfaces. Furthermore, as described in the previous section, the motor model was divided into solid domains (

Figure 1: rotor, stator, coils, insulation, casing, etc.) and fluid domains (

Figure 3: red area, air gap, internal cooling channels, and outer channels).

Microscopic gaps and overlaps between components in the initial CAD model degraded mesh quality. To solve this problem, the model was modified to create a continuous mesh by using a shared topology at all contact interfaces. Furthermore, precise thermal resistance was simulated by modeling the insulation between a motor’s stator coils and core.

To reflect the effects of motor and fan rotation, the rotating components (including the rotating shaft, rotor core, coils, and fan) and the surrounding fluid region were defined as the rotating domain, while the remaining zone of stationary components was defined as the stationary domain. The interaction between the two domains was considered by applying a Frozen-Rotor interface that accounts for the unsteady flow characteristics resulting from relative motion. This approach was selected because it preserves the circumferentially non-uniform flow structures generated by rotor motion, such as swirl patterns and secondary flows, which are essential for accurately predicting local heat-transfer characteristics and hot-spot behavior. Unlike the Stage (mixing-plane) model, which circumferentially averages the flow and may smooth out critical velocity gradients, the Frozen Rotor method maintains the detailed flow field across the interface. Therefore, it is more suitable for achieving high-fidelity CHT analysis in a large generator motor with complex cooling passages. Setting up these rotational-periodic, solid–fluid, and rotating–stationary interfaces in a fully conformal manner is particularly challenging for large and complex rotor systems. This study successfully overcame these difficulties through the conformal interface–based modeling procedure described above.

2.3.2. Mesh Generation and Governing Equations

A hybrid mesh was constructed using ANSYS Meshing version 2024 R1 by combining structured and unstructured meshes. As shown in

Figure 4, an inflation layer was applied to enhance the accuracy of heat transfer at solid-fluid interfaces, and a y

+ value was adjusted to 1 or less in all walls. In addition, at least five mesh layers in the thickness direction were used for high aspect ratio components like copper coils to ensure the accurate analysis of the conductive heat transfer.

A computational fluid dynamics (CFD) analysis was performed using the commercial software Ansys CFX version 2024 R1. This analysis simultaneously solves the Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) equations for fluid flow and energy equations for both solid and fluid domains based on the conjugate heat transfer (CHT) technique. For this purpose, the governing equations are structured as follows:

Continuity Equation for a Fluid:

Here, ρ is density, u is velocity, p is pressure, μeff is the coefficient of viscosity, keff is thermal conductivity, T is temperature, and Sh is volumetric heat source.

For a solid, the convection term is removed, conductive heat transfer and internal heat generation are considered, and the governing equation is used as shown in Equation (4).

Here, α is thermal diffusivity, q‴ is volumetric heat capacity, and cp is specific heat capacity.

In CHT analysis, the continuity of both temperature and heat flux must be guaranteed at fluid-solid interfaces. In this study, a conformal mesh was used at all interfaces to ensure that the heat flux continuity condition was accurately enforced.

The Shear Stress Transport (SST) k-ω model was used to analyze turbulent flows in the fluid domain. This model combines the high accuracy of the k–ω model near the wall with the stability of the k–ε model in the free-flow region, and demonstrates excellent performance in interpreting complex rotating flows and boundary layer separation. The SST k-ω model is well-suited for CHT simulations involving narrow gaps and complex rotating flows. Moreover, this model improves heat transfer calculations by allowing a direct wall analysis without the need for wall functions using a y+ < 1. Therefore, to ensure that the wall y+ values remained below 1, a five-layer inflation mesh was applied. As a result, the maximum y+ value on all solid–fluid walls was 0.96, satisfying the near-wall resolution requirement.

2.3.3. Boundary Conditions

Boundary conditions were specified by applying volumetric heat sources to major components that generate heat. The major source of heat is copper loss from the rotor and stator coils, and copper loss of 30.9 kW accounts for a substantial amount of the total heat generated. Moreover, since the coils are smaller than the motor core, the heat generation per unit volume is expected to be greater, leading to an increase in the actual internal temperature of the motor.

A total heat generation of 8.3 kW due to iron losses in the rotor and stator was applied as a volumetric heat source in the boundary conditions. Mechanical losses from shaft–bearing friction were not considered, as they have a negligible thermal impact. The bearings are located over 0.4 m away from the primary heat-generating components, and any heat produced at the bearings can be transferred only through the shaft. Because the motor operates at a relatively low speed of 720 rpm, mechanical losses are small, and the shaft is directly exposed to internal cooling airflow, which further dissipates heat. Therefore, the contribution of bearing-related mechanical losses to the internal thermal field was judged to be insignificant and was excluded from the analysis.

The test conditions were set such that the rotor and internal cooling fan rotated at 720 RPM, while the external environment was maintained at an atmospheric temperature of 40 °C and 1 atm pressure. Under these conditions, both the inlet and outlet were modeled using the CFX Opening boundary condition with a reference static pressure of 1 atm. The Opening setting allows fluid to enter or exit depending on the pressure field generated by the rotating fan, resulting in natural inflow through the lower opening and outflow through the upper opening. Although optional turbulence specification fields are available for opening boundaries, explicit inputs were not required because the flow distribution is primarily governed by the fan-induced pressure difference. In addition, no backflow treatment was necessary, as Opening boundaries inherently handle reverse flow by automatically switching to an inflow condition when backflow occurs.

Since the external surface of the outer casing is exposed to the external atmosphere, the convective heat transfer coefficient is an input on the outer wall surface. Using the expected external surface temperature and characteristic length, the Grashof (Gr) and Rayleigh (Ra) numbers can be calculated to infer the convective heat transfer coefficient value. Since no external forced airflow is applied to the housing, the external heat transfer was treated as natural convection. By supposing that the external characteristic length of the motor was 1 m, which corresponds to the distance from the lower inlet to the upper outlet and represents the main flow-development region along the motor’s outer surface, the external temperature was set to 40 °C and the outer casting temperature to 60 °C. Under these conditions, the Gr and Ra numbers can be calculated using Equations (5) and (6) below.

Since the Ra number exceeds 104, the Nusselt (Nu) number can be calculated from the Ra number using Equation (7) below.

When the value C was 0.1 [

23] considering a vertical plate, the Nu number was calculated to be 118, and the h value was calculated to be approximately 3.26 W/m

2K. This value was used as the external surface convection heat transfer coefficient.

Since the insulating coating was 250 μm thick on a copper coil exposed to the air, the thermal resistance of the thin insulating layer was modeled by applying thickness and thermal conductivity without a direct mesh division in the Thin Film function of Ansys CFX.

To evaluate cooling performance at different flow rates, the fan size was changed to vary the flow rate. Typically, flow rate and fan size have a proportional relationship based on fan similarity. For this reason, the analysis was performed by varying the height of a fan, starting from 70 mm to achieve a flow rate deviating by ±30% from a baseline of 1.96 kg/s.

Furthermore, since generator temperature distribution varies with operating conditions across its components, the changes in internal temperature under different operating conditions were analyzed by varying ambient temperature and heat generation in each component. In particular, the heat generation was set to 88% of the maximum possible value through additional calculation, and the impact of changing operating conditions on cooling performance was evaluated by comparing and analyzing the outcome with that of the maximum heat generation condition. Likewise, the key parameters of an actual motor were replicated as precisely as possible by applying the specific operating conditions, geometry, and insulation conditions. The detailed boundary conditions of each motor component are summarized in

Table 3.

2.3.4. Mesh Independence and Validation

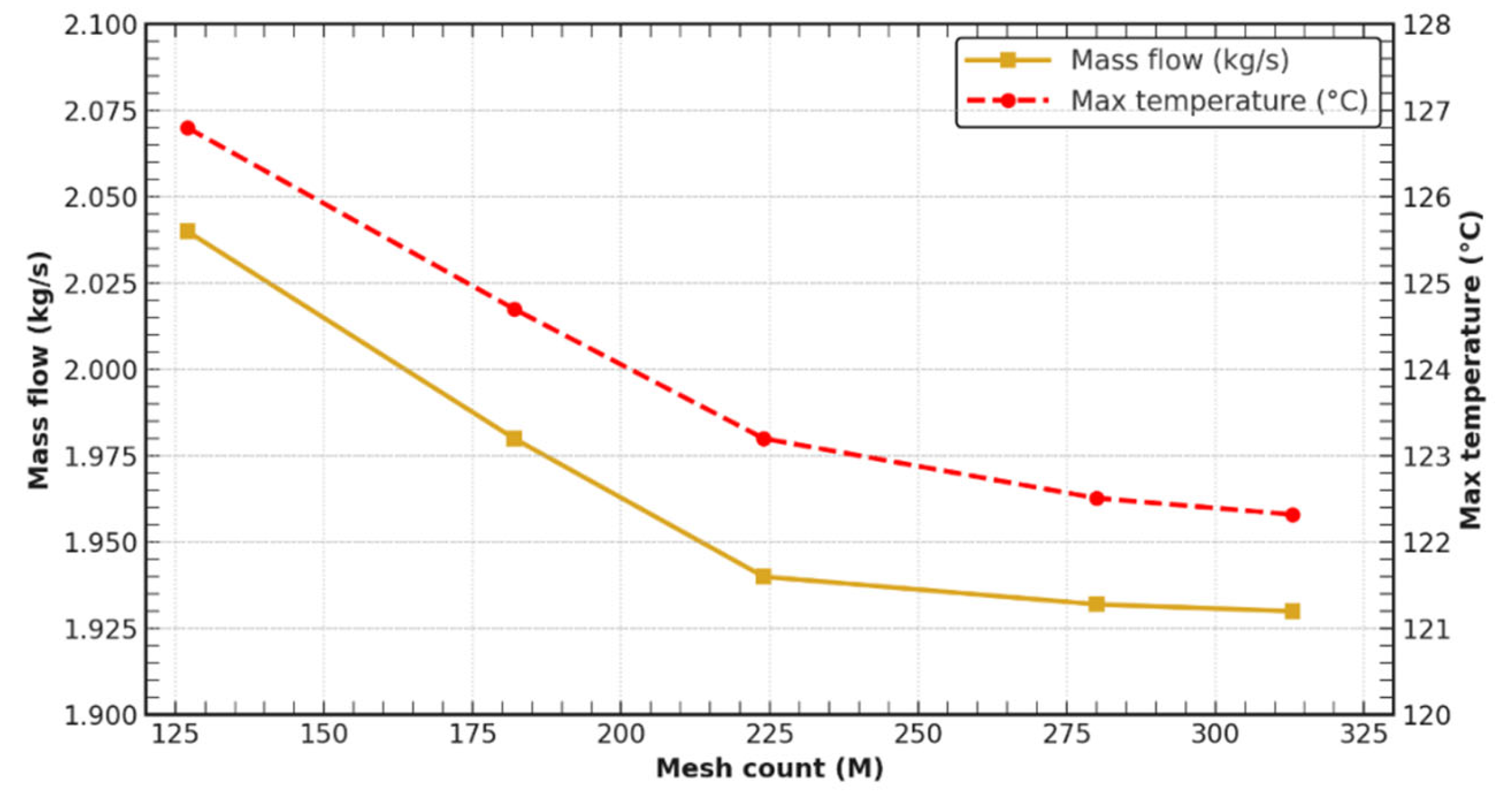

After completing the motor CHT modeling and mesh configuration, flow rate results were compared to the design value by varying the number of meshes to verify the reliability of the mesh. As shown in

Figure 5, when the number of mesh reached 28 million, the flow rate converged to 1.93 kg/s and the maximum temperature to 122.51 °C. Since this study analyzed conjugate heat transfer and spinning machinery, changing the number of mesh affected the convergence of flow rate and energy amount.

A sufficient number of meshes is essential for achieving the convergence of flow rate and maximum temperature. Considering the complexity of this analysis, this implies that the analysis was performed with a high degree of consistency following fundamental principles such as conservation of mass and energy. The CHT model for motor analysis was developed to ensure reliability and was built on a foundation of highly consistent modeling and mesh configuration. Through this process, detailed interpretation and analysis of thermal characteristics were carried out according to the temperature and cooling of each motor component.

3. Research Result

3.1. Temperature Distribution of Generator Components Under Design Point Conditions

This study used a three-dimensional CHT analysis to identify the heat-flow characteristics of a 1 MW synchronous motor–generator and simultaneously analyzed the effect of cooling flow rate changes on the temperature distribution.

First, the temperature distribution across different parts of a generator was determined based on design parameters. The design conditions were set to a fan blade height of 70 mm, a rotational speed of 720 RPM, and an air flow rate of 1.96 kg/s. Furthermore, the test conditions were a total heat generation of 39.2 kW and an ambient temperature of 40 °C.

This describes a fan-assisted cooling system where air is drawn in through an open inlet, circulated by fan rotation, and expelled through an open outlet to cool a component, such as an electrically excited motor. Setting the inlet and outlet to “open conditions” is a common setup in computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations to allow for a natural inflow and outflow of air.

In the analysis, the air inlet and outlet boundaries were set to open conditions, and the air drawn in by the fan’s rotation was used as the cooling fluid. The inflow air flow rate was calculated to be approximately 1.93 kg/s at a given condition of a fan blade height of 70 mm. This value closely matched an actual design value of 1.96 kg/s.

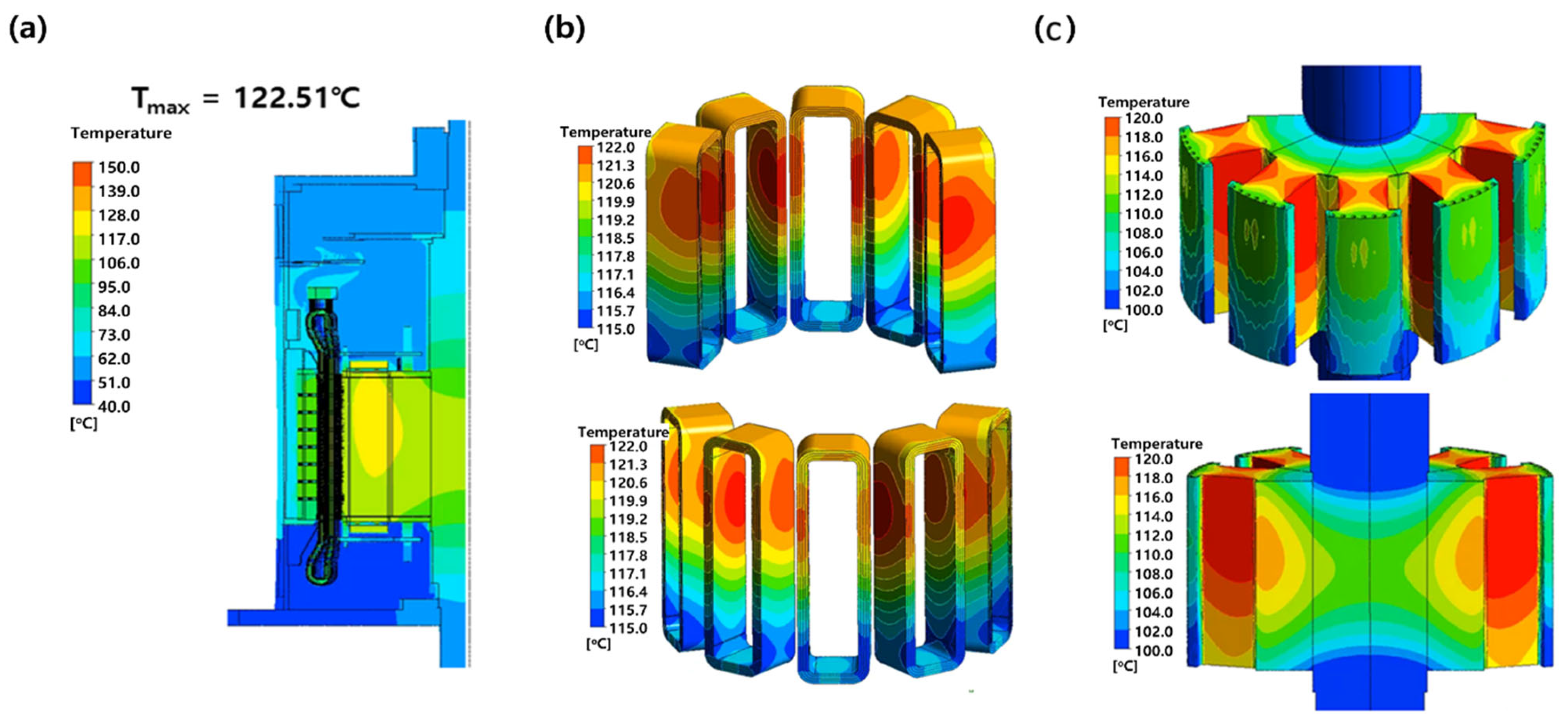

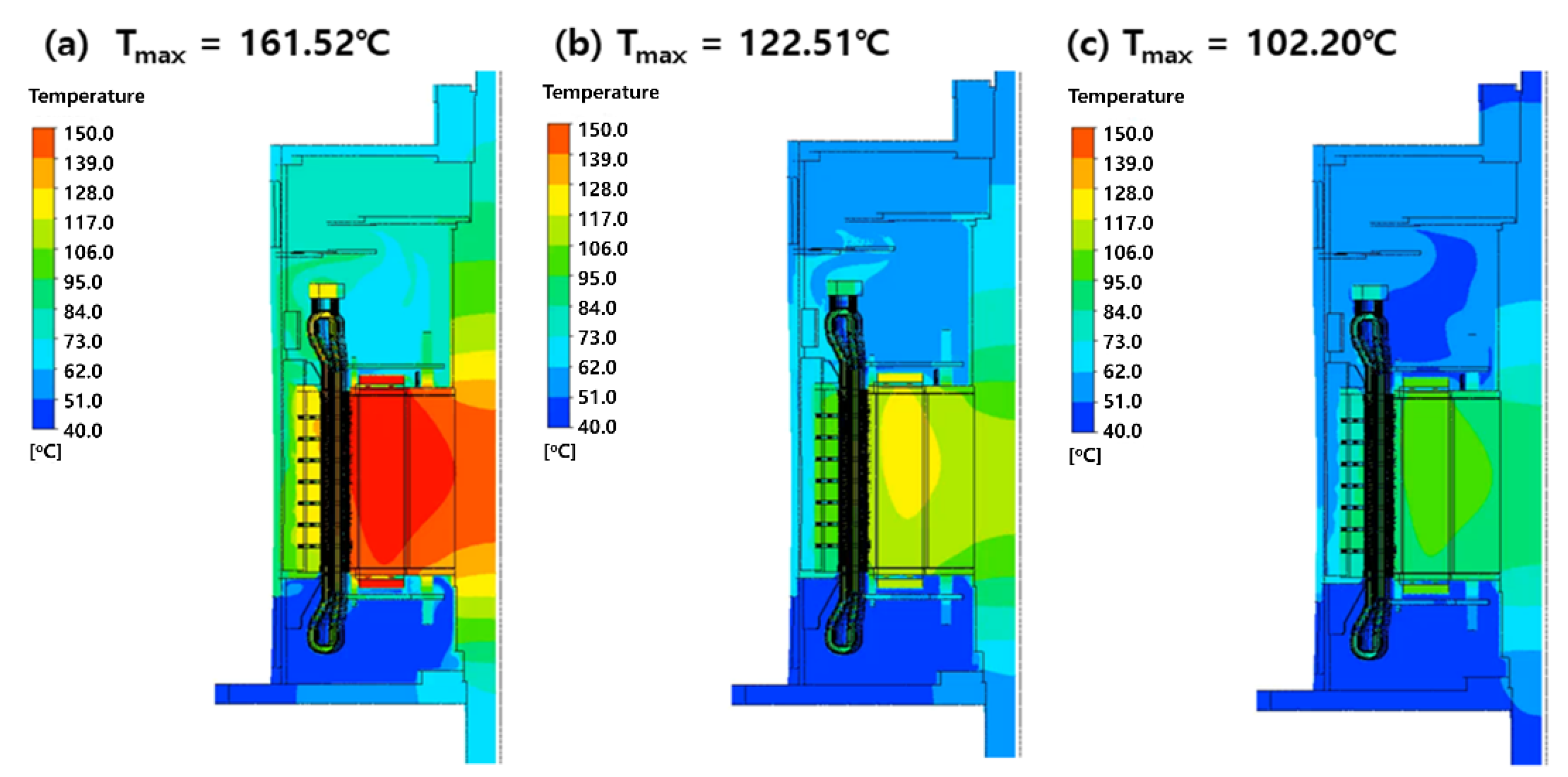

As shown in

Figure 6a, under the condition of 1.93 kg/s, the heat distribution in a generator is primarily formed in the rotor and stator coils, which are the main heat sources. To facilitate visualization of the full circumferential distribution, the 1/10 sector geometry was replicated five times during the CFD post-processing stage using the periodic condition. It should be noted that the thermal results were computed only for the 1/10 model and the repeated temperature patterns. The overall highest temperature was approximately 122.5 °C, and as the cooler air introduced at the bottom rose to the top, a distinct temperature gradient was created with the bottom temperature ranging between 80 and 100 °C and the top at 110–120 °C. This is because temperature gradually increases as the rising air absorbs heat built up at the top, and this heat accumulation causes the cooling performance to decrease. The heat transfer trend demonstrated that temperature decreased in the order of components from rotor coil → rotor core → stator coil → stator core → outer casing.

The rotor coil is one of the primary heat sources in a motor. As shown in

Figure 6b, the temperatures were 122.5 °C at maximum, 119.4 °C on average, and 115 °C at minimum. The temperatures ranged between 115 and 117 °C in the lower part because of the direct cooling effect of the incoming air, but exceeded 120 °C in the upper part due to reduced cooling efficiency. The heat generated in the coil was concentrated on the inner parts of the rotor core and shaft by conduction, creating a high-temperature region, while the outer surface maintained a relatively lower temperature because of the cooling air moving via convection. These results indicate that there is a need to improve cooling performance in the upper part so as not to exceed a design target temperature of 120 °C in the future.

The temperature of the rotor coils directly influences the rotor core. As heat generated from the rotor coils was conducted and transferred to the rotor core, the temperature rose to the hottest at 120 °C near the center and the axis, 102–106 °C at the bottom, and 114–120 °C at the top, as presented in

Figure 6c. The center of the rotor core tended to be hotter because heat transfer was concentrated towards the center, but the outer region had relatively cooler temperatures ranging between 104 and 110 °C because of the convection of cooling air.

The reason the rotor and coil temperatures reach or exceed 120 °C is that the cooling air entering from the bottom heats up, causing their temperatures to rise, and at the same time, a large portion of the flow diverges into internal and external channels of a stator core. This results in a reduced absolute flow rate of cooling air passing through the rotor coils and the upper rotor core and will cause insufficient cooling of the upper portion and a temperature rise.

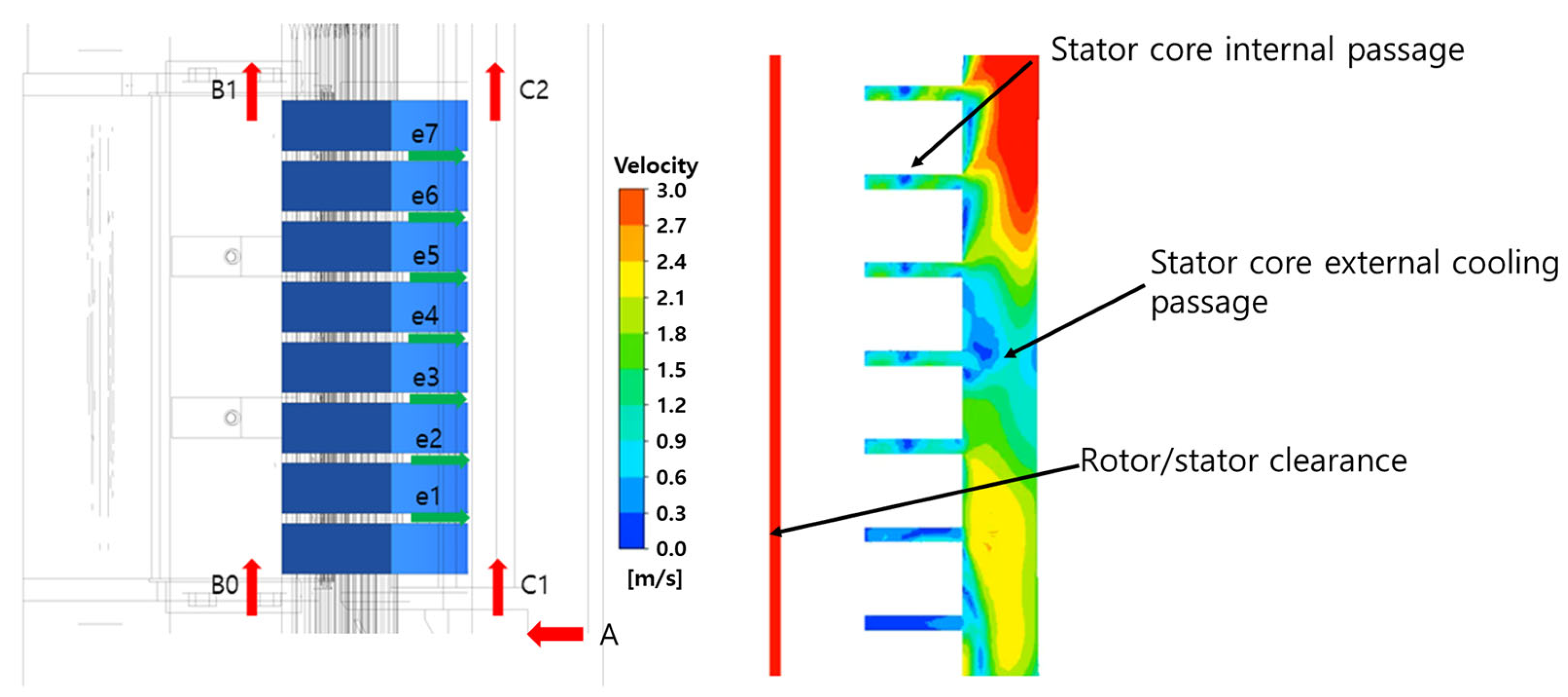

As shown in

Figure 7 and

Table 4, a specific amount of flow was observed to escape to the outside through the internal passages of the stator core. At the initial inflow point, approximately 93% of the total cooling air flow flowed into the narrow gap between the rotor and stator, and effectively cooled the lower part of the rotor region. However, approximately 46% of the total flow was diverted to the seven laminated internal passages (e1–e7) and directed to the external passages of the stator, significantly reducing the coolant flow rate for the rotor core and the upper coil. This outcome deteriorates cooling performance and causes high temperatures in the upper region of the rotor.

Due to the distribution characteristics of the cooling air flow, the stator and rotor have different temperature distributions. In a rotor, cooling air flowing from the bottom and rising creates a clear vertical temperature gradient, with the air being cooler at the bottom and warmer at the top. In contrast, the stator coils and core have a small vertical temperature gradient, as shown in

Figure 8, because heat is mainly concentrated at the center. Although air picked up heat as it moved upward, leading to a temperature rise and reduced cooling performance, at the same time, it can be interpreted that an increased air flow rate into the stator core suppressed excessive temperature rise at the top. Thus, the stator maintained a relatively uniform temperature distribution because the increased cooling flow rate partially offset the negative performance effects of increased cooling air temperature.

Since the stator coil and core are in direct contact with the outer casing and core support structure, this direct physical contact facilitates heat dissipation. For this reason, the support contact area maintains a lower temperature than the surrounding environment, and because of this structural characteristic of heat dissipation, a periodic low-temperature region is created. In addition, a temperature difference of approximately 5 °C or greater can exist between the inside and outside of a stator core due to active cooling of the stator core’s outer surface using an external flow path. Even though the stator coil produced more heat than the rotor coil because of the configuration and flow paths of the generator cooling channels, a 15 °C lower maximum temperature and a 23 °C lower average temperature were achieved due to the influence of the heat dissipation path and cooling flow distribution.

3.2. Temperature Variation with Cooling Air Mass Flow Rate

To determine the required cooling air flow rate to maintain a generator’s target temperature limits, we analyzed the effect of different cooling air mass flow rates on the temperature distribution of the generator. The fan blade height was varied to alter the cooling air flow rate. In general, as the fan blade height increases, the effective area of the fan outlet expands linearly, and consequently, the mass flow rate also increases linearly with blade height according to the fan affinity law. Therefore, this study varied fan blade heights to analyze the performance with three different heights: 35 mm, 70 mm (the design value), and 110 mm. As a result, cooling air mass flow rates were calculated to be 0.93 kg/s, 1.93 kg/s, and 3.03 kg/s, respectively, confirming the theoretical relationship that mass flow rate is linearly proportional to the fan blade height. Furthermore, this analysis used the fixed thermal boundary conditions for a generator simulation: a heat generation rate of 39.2 kW and an ambient temperature of 40 °C, matching the design conditions.

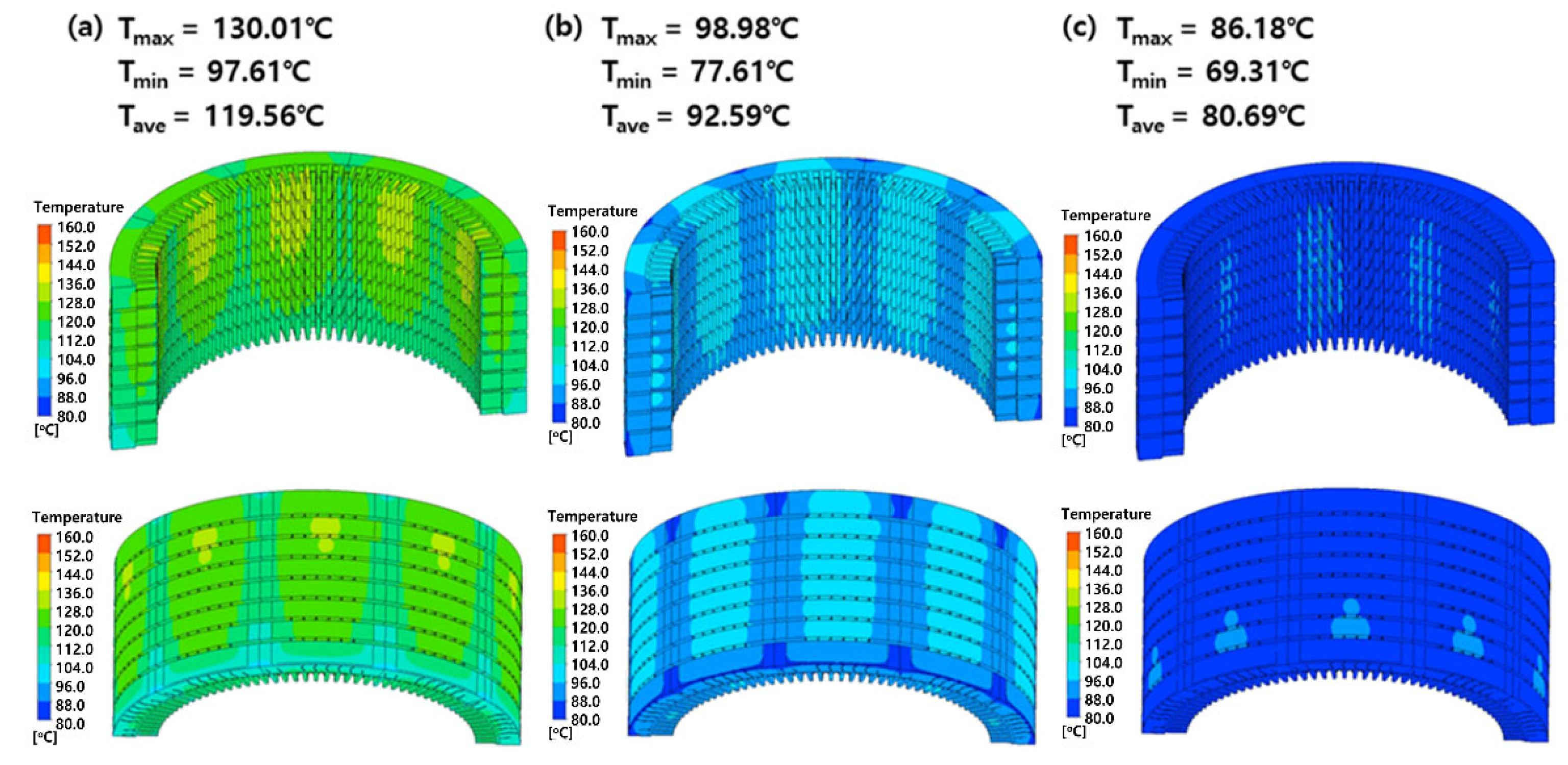

As shown in

Figure 9, increasing the cooling air flow rate reduces the overall and peak temperatures inside a generator. A decrease in airflow rates in a rotor coil led to a wider high-temperature zone with a highest temperature of 161.52 °C, and created a large vertical temperature gradient between the upper and lower parts. On the contrary, when the flow rate increased to 3.03 kg/s, the peak temperature decreased by approximately 60 °C, and the temperature difference between the upper and lower parts was significantly reduced. This is because the self-temperature rise of the air passing through a motor is limited under high-flow conditions, ensuring sufficient cooling performance.

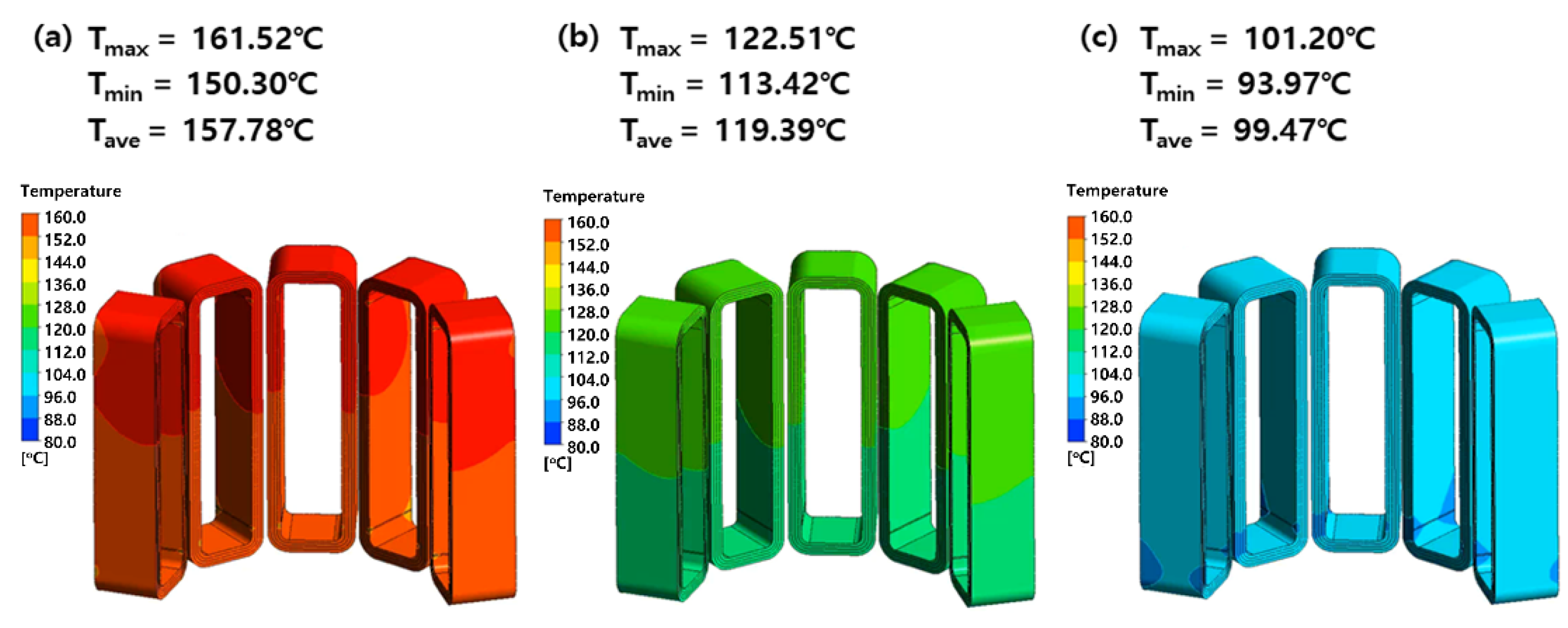

The rotor coil (

Figure 10) is the component that constantly exhibits the highest temperature due to significant heat generation from copper loss. A cooling flow rate of 2 kg/s or higher was sufficient to cool a coil by lowering the peak temperature to approximately 120 °C within the acceptable temperature range. The temperature difference between the upper and lower parts reached up to 11 °C at low flow rates, and decreased to about 7 °C at high flow rates. In other words, increasing the flow rate simultaneously contributes to both lowering the coil’s peak temperature and achieving temperature uniformity.

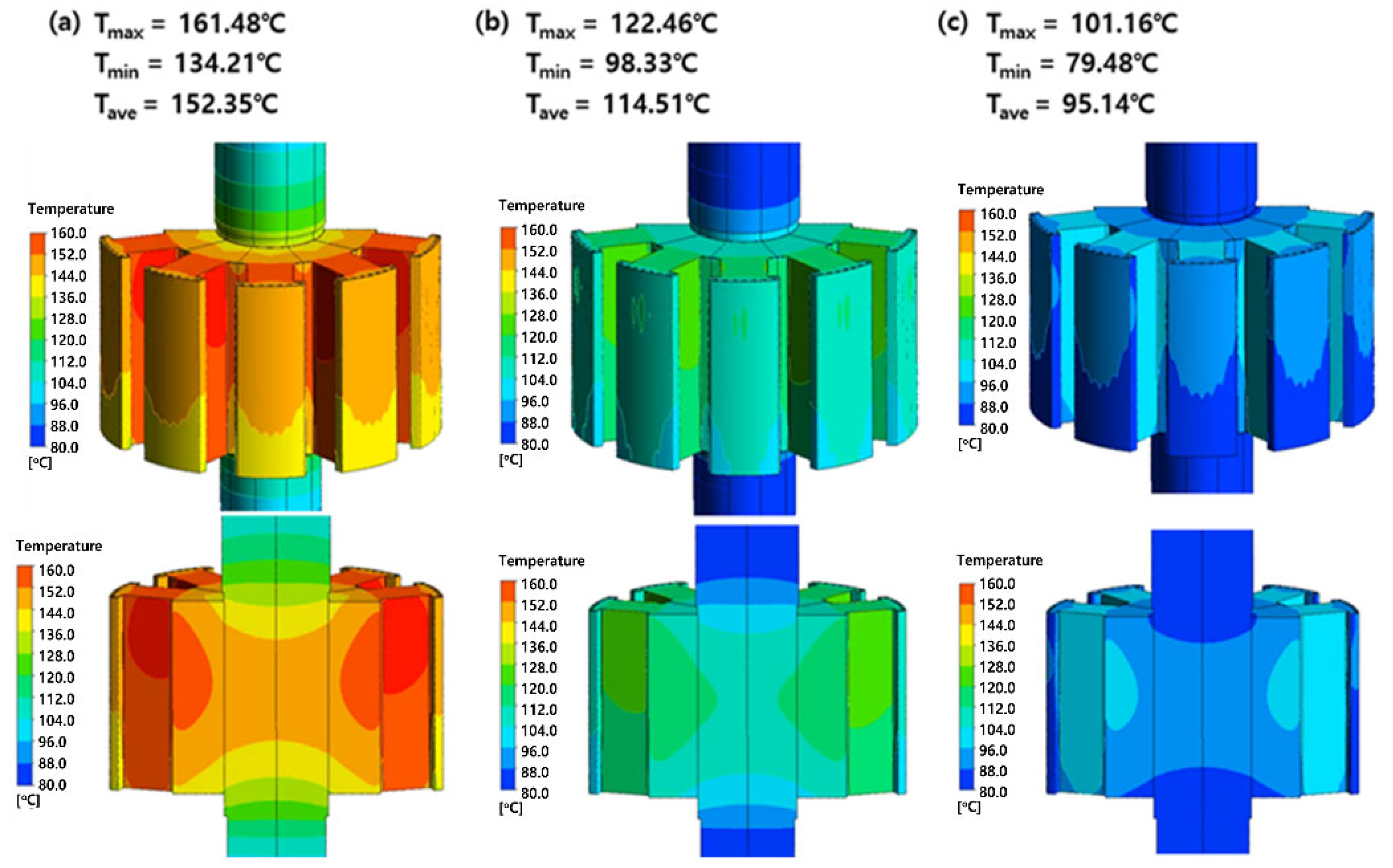

The rotor core (

Figure 11) exhibits a peak temperature similar to the coil’s temperature at their contact point, because it receives heat from both its own iron losses and conduction, as heat is being conducted directly from the coil to the core and then to the shaft. The outermost surface maintains a relatively lower temperature than the core through convection to the outside air, but a temperature difference arises between the upper and lower surfaces even on the outer surface due to the upward movement of the incoming air. Conversely, the inner surfaces near the shaft are insignificantly affected by external convection, leading to a high-temperature region at the center.

At low flow rates, temperature non-uniformity between a hot rotor coil and core is significant. As the flow rate increases above a certain point, the flow becomes turbulent, leading to a more uniform temperature distribution. Although two components share heat transfer characteristics through contact, temperature behavior varies by location due to different boundary conditions, including the rotor shaft and external cooling airflow path. Therefore, when determining cooling flow rates, it is essential to consider both the highest temperature and local temperature indicators, such as local temperature difference and location with the highest temperature.

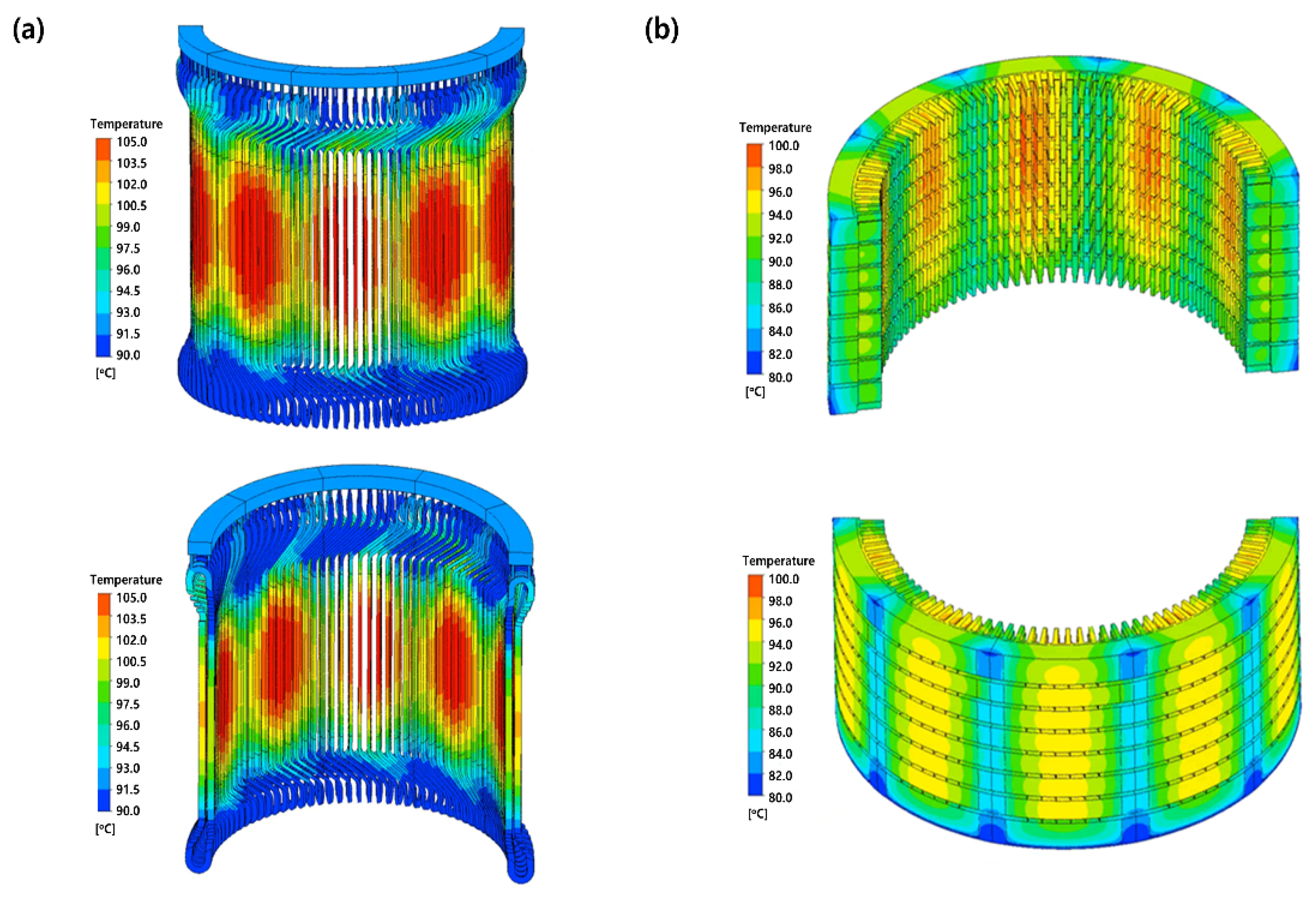

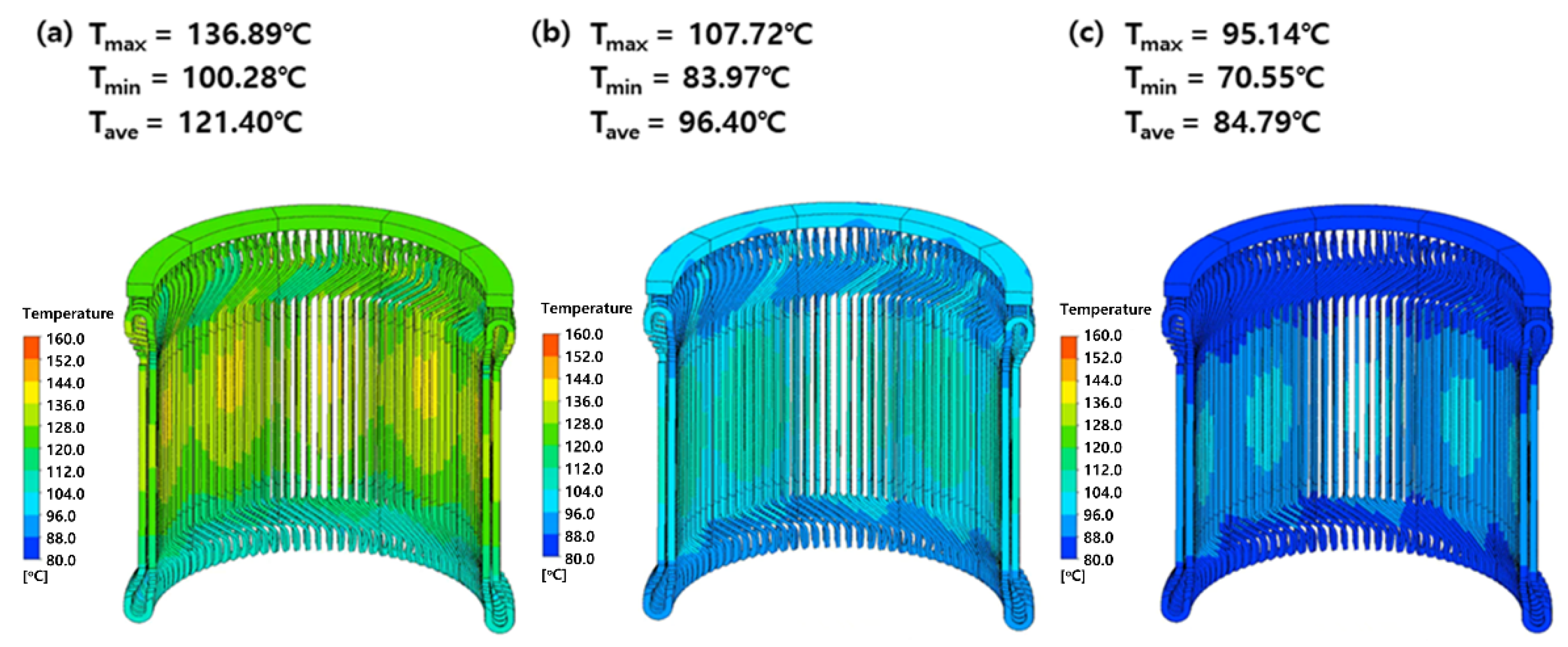

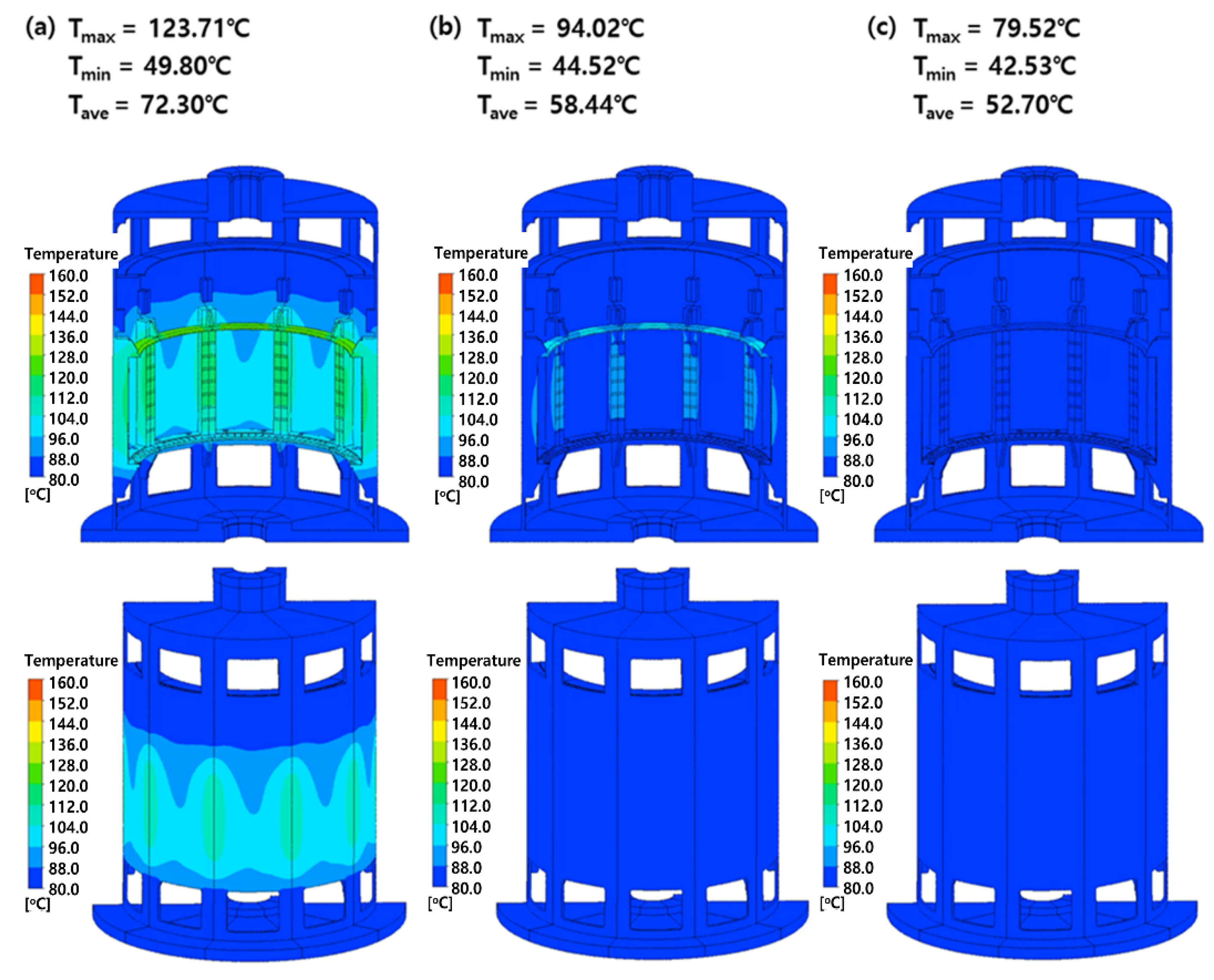

The stator core support closely connects the stator core, coil, and outer casing by creating a conductive thermal path shared by these three parts. For this reason, unlike the rotor, which maintains a more uniform temperature distribution in circumferential directions due to its annular design, the stator-related components exhibit the periodic temperature pattern along the stator core support as shown in

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14. The stator core support contact area actively dissipates heat to the casting, creating a localized low-temperature area on the casing. Consequently, a small vertical temperature gradient from the top to the bottom and the highest temperature at the center of a coil are likely to be seen.

As shown in

Figure 12, although the stator coil generates more heat than the rotor coil and is surrounded by insulation, its peak temperature is lower than that of the rotor coil due to multiple heat dissipation paths, including direct contact with the core and casing. On the other hand, the rotor coil is more sensitive to flow rate changes than the stator coil. When the flow rate increased from low (ṁ ≈ 0.93 kg/s) to high (ṁ ≈ 3.03 kg/s), the peak temperature of the rotor coil decreased by about 60 °C (a 35–40% reduction), but that of the stator coil only decreased by about 40 °C (a 25–35% reduction). This is interpreted as because the cooling of a stator coil primarily relies on the conduction path to the core and the casing instead of improving convection with increasing flow rate.

As shown in

Figure 13, the temperature distribution in a stator core has a distinct difference between the inner and outer surfaces. This is because the outer surface of the core is effectively cooled by an external cooling passage created by the outer wall of the stator core and a core support structure. The inner surface of a stator core is hotter than the outer surface due to heat generated within the core, and the cooling air heats up as it moves through the rotor–stator gap, and this rising temperature creates a high-temperature region at the top of the gap. In contrast, the outer surface typically has a lower temperature than the inner surface. The lower surface is cooler because the cool incoming air lowers the temperature, and the temperature increases towards the top of the stator core, but the rate of increase is lower than on the inner surface. This is because the cooling air directed through internal channels in the stator core branches off to flow along external passages for additional cooling from the outside. As a result, a gentler vertical temperature gradient is created on the outer surface.

As shown in

Figure 14, heat generated internally is transmitted to the outer casing in areas with low fluid flow and causes the external casing to exceed a critical temperature of 123 °C. Conversely, a separate casing from the coil area experiences a temperature drop of about 49 °C, creating a large temperature gradient of up to approximately 74 °C across the outer surface. Meanwhile, high fluid flow within a casing reduces internal temperature differences to about 37 °C and minimizes thermal non-uniformity across the outer surface.

These local temperature differences can cause mechanical deformation by creating uneven thermal expansion in different parts of a casting. In rotating machinery, accurate alignment between the shaft and stator bearing is crucial. Large thermal gradients can lead to shaft micro-misalignment in the shaft and increased bearing load, resulting in higher friction, vibration, and noise. Over time, this can degrade lubrication, shorten bearing life, and increase mechanical losses. Thus, internal heat generation in a motor can cause flux loss or winding deterioration, and external heat may increase the risk of mechanical friction and loss, leading to fatigue and cracking.

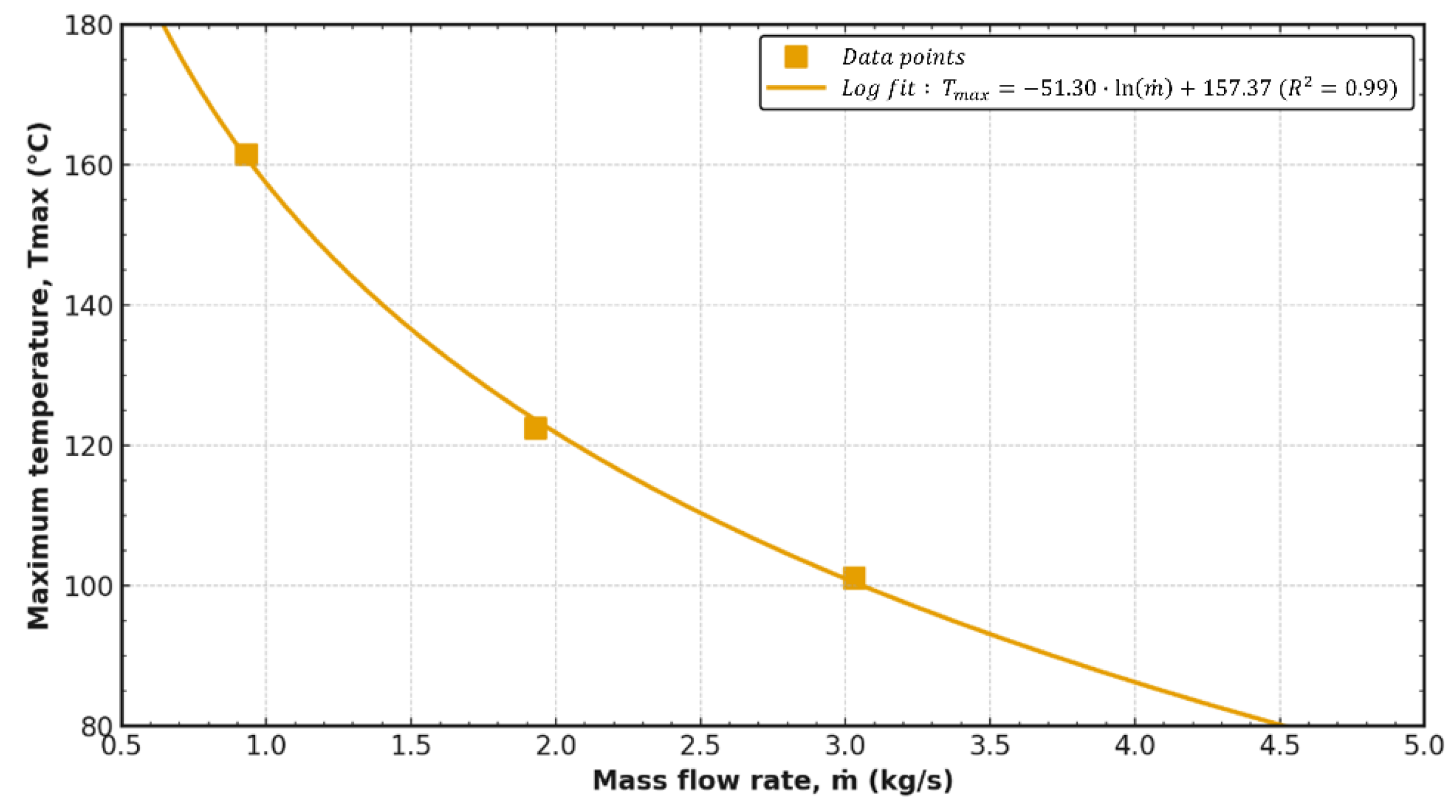

As shown above, the local temperature changes with changing flow rate, and the peak and average temperatures of each component change non-linearly.

Figure 15 presents a graph of the change in the maximum temperature (T

max) according to the mass flow rate of cooling air. As the mass flow rate increases, the peak temperature change decreases to a more gradual temperature rise and eventually converges toward a steady-state temperature. These changes in the flow rate and peak temperature are because the convective heat transfer coefficient at the wall increases with the increase in flow rate. The relationship between the convective heat transfer coefficient and the flow in a pipe is described by the relationship between the Nusselt number (Nu) and the Reynolds number (Re), and can be expressed as an exponential correlation in Equation (8) shown below.

Here, since the heat transfer coefficient is proportional to the Nu number (h ∝ Nu), the convection resistance decreases as the flow rate increases. An initial sharp decrease in peak temperature followed by a more gradual decrease was consistent with the combined effects of convection resistance.

Reflecting these characteristics, the relationship between peak temperature and cooling flow rate can be expressed as a correlation equation having a high coefficient of determination (R

2 = 0.99), as shown in Equation (9), using the logarithmic function.

Based on this equation, the peak temperature inside a generator can be predicted reliably even under off-design flow conditions.

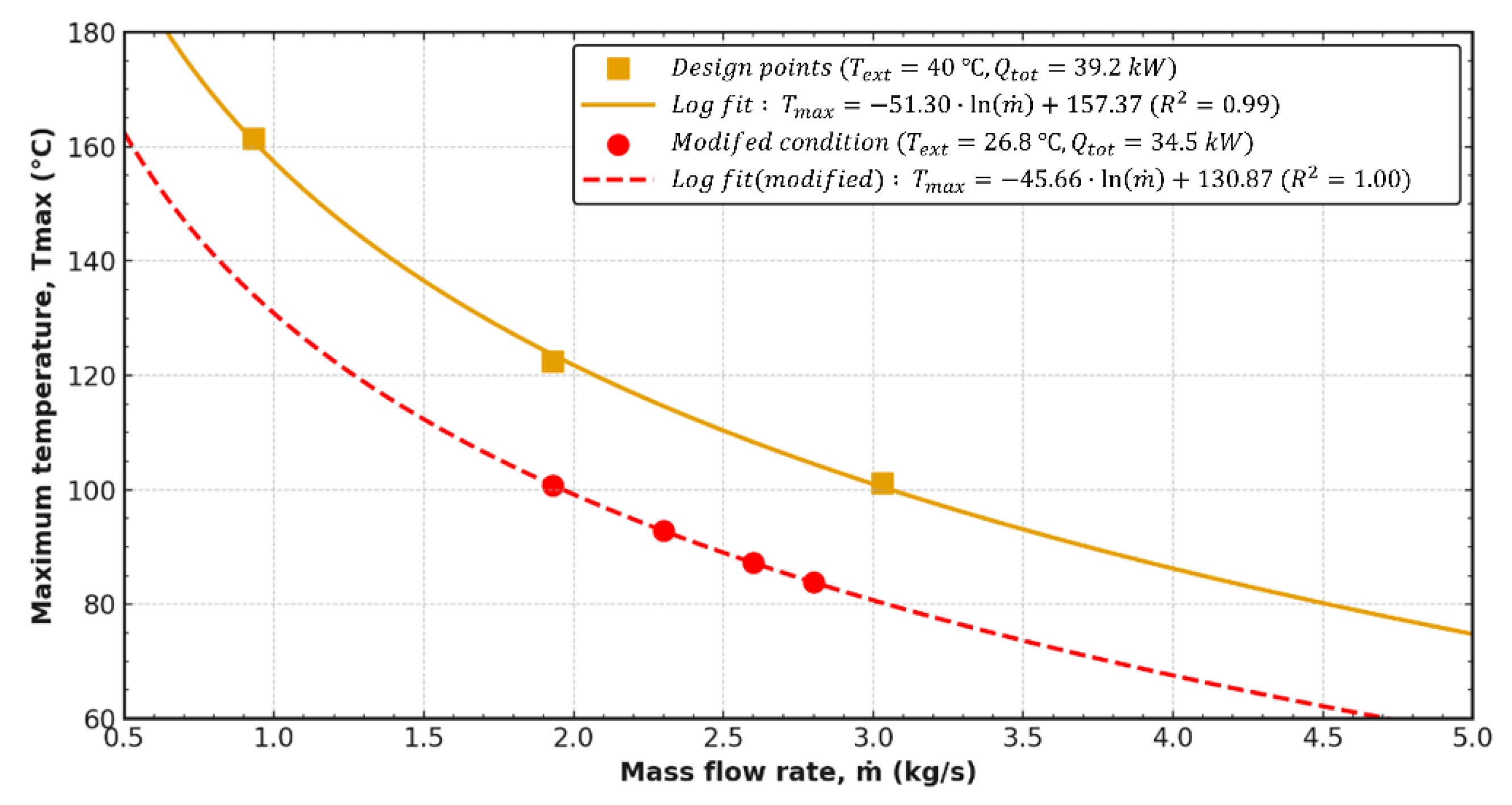

3.3. Temperature Variation Under Different Operating Conditions of the Generator

Figure 16 shows the results of comparing the peak motor temperature by changing the mass flow rate after adjusting for total heat output and outside temperature. The design points are an external temperature of 40 °C and a total heat output of 39.2 kW. The modification conditions include reduced heat output to 34.5 kW, which is 88% of the design value, and lowered outside temperature to 26.8 °C. Under both conditions, as the mass flow rate increases, the peak temperature decreases logarithmically and the rate of temperature change becomes more gradual, approaching a saturation trend.

The log correlation equation under changing operating conditions is shown in Equation (10).

Coefficient changes revealed that the slope preceding a logarithmic term in a mass flow rate decreased from 51.30 under design conditions to 45.66 under modified conditions. The ratio of these two values was approximately 0.89, very close to a heat generation ratio of 0.88. This outcome implies that if the heat load is reduced by approximately 1%, when the mass flow rate is reduced, the rate of peak temperature drop is also reduced at the same rate. In other words, the temperature sensitivity to flow rate changes decreases almost proportionally to heat load size.

The y-intercept is 26.5 °C lower than the design value. When compared after adjusting external temperature differences, the intercept of the design condition minus the outside temperature is 117.37 °C (=157.37 − 40), and the change condition is 104.07 °C (=130.87 − 26.8). Therefore, the ratio of the adjusted y-intercepts relative to the initial design value is 0.89. This means the y-intercept has been reduced to approximately 89% of its original value after the outside temperature adjustment and directly corresponds to a reduction in heat load like the slope.

Based on these results, when the design point correlation (Equation (11)) is given, the coefficients of the correlation for off-design conditions under varying outside temperatures and heat generation levels can be calculated by using Equations (12) and (13). The analysis of a generator modeled in this study requires rotational conditions and complex heat transfer, leading to a large mesh configuration and high computational costs. Nevertheless, using the above logarithmic correlation and correlation between coefficients (Equations (12) and (13)), the peak generator temperature can be quickly predicted without additional computational analysis, despite heat generation and ambient air changes. This study is expected to provide important reference information in making rapid condition prediction and cooling design decisions for various operating scenarios.