Abstract

Accurate short-term and medium-term wind speed and wind direction forecasting are crucial for aviation safety, renewable energy management, and environmental planning, particularly in coastal areas with complex terrains. In this study, four machine learning models (Temporal Fusion Transformer (TFT), LightGBM, CatBoost, and a multi-head Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)) were used for multi-horizon (1–24 h) forecasting in Kastelli, Crete, near the new Heraklion International Airport, using a high-resolution multivariate meteorological dataset (2015–2023). For the wind speed forecasting, the best mean absolute error (MAE) values at each horizon are 1 h = 1.89 m/s (LightGBM), 6 h = 3.12 m/s (CatBoost), 12 h = 3.44 m/s (TFT), and 24 h = 3.38 m/s (TFT). For the wind direction forecasting, the best angular MAE values are 1 h = 8.66° (CatBoost), 6 h = 30.71° (CNN), 12 h = 35.29° (TFT), and 24 h = 25.65° (TFT). Overall, the study indicates that different models outperform at different horizons, with the tree-based models being the most effective for short-term forecasts, the convolutional network performing best at intermediate horizons, and the transformer-based architecture offering stronger performance over longer horizons. Compared to recent literature, the proposed framework achieves measurable improvements and confirms the feasibility of deploying ML-based forecasting tools.

1. Introduction

Wind speed and wind direction forecasting is a challenging problem in time-series analysis because of the complex, dynamic, and often nonlinear behavior of atmospheric conditions [1,2,3,4]. Wind behavior is influenced by several factors, including terrain characteristics, temperature gradients, and pressure systems, leading to significant short-term and long-term variability. This variability can be particularly significant in regions with complex terrain and mixed coastal and island climatic conditions [1,2,3,4]. The study area is located in Kastelli, Crete, which is in close proximity to the new Heraklion International Airport construction site. This location exhibits diverse topographic and climatic conditions, making it suitable for studying the spatial and temporal variability of the wind. Accurate forecasting in such regions is essential for aviation safety, particularly during takeoff and landing operations that are affected by crosswinds. Additionally, improved forecasting contributes to energy management and operational planning.

In recent years, wind speed forecasting has evolved from traditional statistical and physical models to advanced data-driven approaches. Classical methods, such as ARIMA or numerical weather prediction (NWP), often struggle to capture nonlinear and multiscale atmospheric dynamics, particularly in regions with complex terrain and coastal variability [5,6]. To address these limitations, machine learning techniques, including support vector regression, random forests, and ensemble tree-based models such as LightGBM and CatBoost, have demonstrated improved short-term forecasting accuracy, especially in capturing localized temporal patterns [7,8,9,10].

Deep learning architectures have advanced predictive capabilities by modeling temporal dependencies in multivariate meteorological data. Recurrent networks (RNN, LSTM, and GRU) have been widely applied to time-series forecasting, but their performance can deteriorate over longer horizons, and in extreme cases, training can stall as a result of vanishing or exploding gradients [11]. Alternatively, Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) architectures have been used in either standalone or hybrid frameworks to extract hierarchical temporal features and capture local patterns [12]. CNN-based models typically impose an inductive bias of locality, because each convolution operates within a finite temporal window, and the same learned filters are applied across all time steps. This implies a local stationarity assumption that temporal patterns tend to repeat throughout the sequence, and that statistics within nearby windows remain approximately constant. Multi-head CNNs, encoder–decoder LSTMs, and model selection frameworks have also been applied to Mediterranean datasets, often combining recursive and multiple-output strategies, leveraging novel cloud indices, and emphasizing feature importance and time resolution to enhance robustness [13,14,15].

With the emergence of attention mechanisms [16], transformer-based architectures have become state of the art in time-series forecasting owing to their ability to model long-range dependencies and complex feature interactions and even accommodate multimodal data such as spatial, textual, or auxiliary contextual information. Therefore, the Temporal Fusion Transformer (TFT) [16] and related models, such as WindTrans [17], MSTformer [18], and GAOformer [19], have shown significant performance gains in both short-term and medium-term wind speed forecasting, often incorporating spatial encoding via graph neural networks or signal decomposition techniques, such as variational mode decomposition (VMD) and empirical mode decomposition (EMD).

Furthermore, while most studies focus solely on wind speed forecasting, few studies address the more challenging task of wind direction forecasting, which involves handling angular discontinuities and modeling periodicity in the output space [20,21]. Several recent approaches have employed sine–cosine transformation to represent wind direction in a continuous space vector, enabling regression-based learning without discontinuities [22]. Recent studies have highlighted that the direct prediction of wind direction using standard machine learning models often fails because of these properties, motivating the use of indirect strategies or circular transformations [23]. To the best of our knowledge, few studies have systematically compared wind speed and wind direction forecasting across multiple horizons in real-world coastal environments. This study contributes to this line of research by evaluating and benchmarking state-of-the-art models, including deep learning and gradient-boosting methods.

The objective of this study is to evaluate the performance of advanced machine learning and deep learning models for short-term and medium-term wind speed and wind direction forecasting. In particular, four models were compared, namely, the Temporal Fusion Transformer (TFT), LightGBM, CatBoost, and Multi-head CNN, using a real-world dataset collected from a high-resolution weather station located in the study area. The models were trained to predict both the wind speed and wind direction up to 24-h horizon.

The main contributions of this paper are:

- A comparative evaluation of four machine learning models (TFT, LightGBM, CatBoost, and CNN) for wind speed and wind direction forecasting up to 24-h horizon.

- Development of a real-world forecasting framework using high-resolution multivariate meteorological data collected near a coastal airport site in Crete, Greece, over an eight-year period (2015–2023).

- Demonstration of the complementary strengths of the four models across horizons, with transformer-based architectures (TFT) achieving superior performance at medium horizons, tree-based models (LightGBM, CatBoost) performing best in very short-term predictions, and convolutional networks (CNN) showing competitive results at intermediate horizons, supported by multi-step metrics and wind rose analysis.

- The assessment of model performance in a complex coastal airport environment provides insights into how machine learning architectures handle wind speed and wind direction under challenging microclimatic conditions that are underrepresented in the wind forecasting literature.

The proposed approach aims to assess the robustness and generalizability of these models in a real operational environment, thereby providing insight into their applicability in domains such as aviation forecasting and renewable energy scheduling. Through comprehensive evaluation and visualization, the strengths and limitations of each model were explored to capture both the magnitude and directionality of wind patterns in a complex Mediterranean environment.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the dataset, preprocessing techniques, and formulation of the forecasting problem. Section 3 outlines the machine learning models and their configuration details. Section 4 presents the evaluation metrics and experimental setup. Section 5 discusses the results of the performance comparisons and visual analyses. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper and provides directions for future research.

2. Data Description and Forecasting Methodology

2.1. Data Description

The dataset used in this study was obtained from a high-resolution automatic weather station located in the region of Roussochoria, Heraklion, Crete (Greece), which is situated in immediate proximity to the site of the new Heraklion International Airport in Kastelli. The station continuously recorded meteorological variables at 30-min intervals over multiple years, resulting in a total of 135,408 observations covering the period from 23 July 2015, to 12 April 2023. The dataset is publicly available through the official open data portal of the Crete region.

The features of the dataset are listed in Table 1. This multi-featured dataset captures the atmospheric variability influenced by complex topography and seasonal changes.

Table 1.

Dataset parameters measured.

Table 2 shows the statistical data for each measured meteorological parameter, including the maximum, minimum, mean, and standard deviation values over the entire observation period.

Table 2.

Dataset Max, Min, Mean, Std values.

The wind direction was treated as a circular variable and transformed into its sine and cosine components to address discontinuities around the 0°/360° boundary and facilitate regression modeling. The evapotranspiration (ETo) represents the amount of water lost from a well-watered reference surface (typically grass) through the combined processes of evaporation and plant transpiration. It is derived from key meteorological variables and is expressed in millimeters of water per unit time.

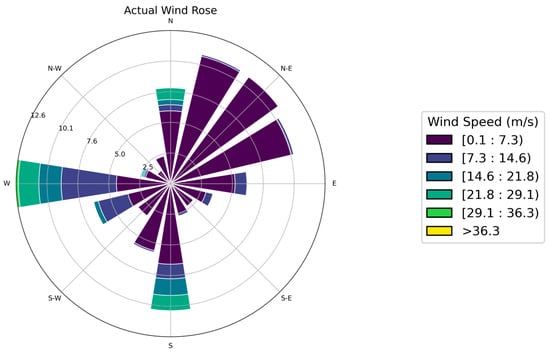

Figure 1 shows the wind rose diagram for the entire 2015–2023 dataset, providing a climatological overview of the wind speed and direction at the Roussochoria station located near Kastelli. The distribution revealed dominant N–NE and W wind patterns, characteristic of the region, with secondary modes observed in the S–SW sector. This climatological baseline illustrates the forecasting problem, as the models are required to reproduce both the prevailing directionality and directional distribution of wind speed. Such reference diagrams are particularly important in coastal and complex terrain environments where wind variability directly affects aviation safety and energy management.

Figure 1.

Wind rose diagram illustrating the observed distribution of wind speed and direction over the entire 2015–2023 dataset.

2.2. Forecasting Problem Formulation

This task was formulated as a multivariate sequence-to-sequence forecasting problem. Given a window of past observations, the goal is to predict the wind speed and wind direction up to the next 24 h (48 time steps at 30-min intervals). This setting captures both short-term and medium-term forecast horizons, which are critical in operational meteorology and energy scheduling.

Each horizon-specific model outputs a sequence at 30-min intervals covering its respective forecast horizon (2, 12, 24, or 48 steps for 1 h, 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h, respectively), along with two vectors representing the sine and cosine components of the predicted wind direction. After the prediction, the inverse trigonometric function arctan2(sin, cos) was used to reconstruct the directional values in degrees.

2.3. Machine Learning Models

The study investigates the performance of four machine learning models with distinct architectures.

The Temporal Fusion Transformer (TFT) represents a state-of-the-art deep learning architecture designed for interpretable, multi-horizon time-series forecasting. It integrates gated residual networks, variable selection networks, and multi-head attention to capture both short-term and long-term dependencies across multivariate inputs. In this study, TFT was applied separately for wind speed and the sine/cosine components of wind direction, providing insights into feature relevance at each time step, which is an important aspect of meteorological forecasting [16].

The CatBoost algorithm is a gradient boosting decision tree method optimized for efficient handling of categorical features and reduced overfitting in small or noisy datasets. It introduces ordered boosting and symmetric tree structures to enhance model stability and generalization, making it suitable for real-world tabular meteorological data with strong local dependencies [9].

The LightGBM framework is another gradient-boosting approach that employs histogram-based decision tree learning and leaf-wise tree growth with depth limitations. Its efficiency and low computational cost make it well suited for short-term forecasting applications, where rapid training and adaptability are required [8,9].

A Multi-head Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) is a deep learning model composed of multiple parallel one-dimensional convolutional branches with varying kernel sizes designed to capture multiscale temporal patterns. The outputs of each branch were concatenated and passed through fully connected layers for sequence prediction, thereby enabling the effective extraction of localized temporal features. Such architectures have been successfully applied to renewable energy forecasting tasks [12,13].

All the models were trained using the same data-partitioning protocol (80% training, 10% validation, and 10% testing) and evaluated on horizon-specific configurations. The assessment focused on the forecast accuracy for both magnitude (wind speed) and direction (angular prediction reconstructed from sine and cosine components).

3. Wind Data Preprocessing and Forecasting Model Configurations

Wind direction, which is a circular variable, poses challenges for regression tasks. The use of sine and cosine decompositions enables smooth modeling of angular transitions across the 0°/360° boundary, following the best practices adopted in recent transformer-based architectures [17,18,21].

All continuous variables were standardized using z-score normalization based on the training set. Time-based features, such as hour of day, day of the week, and month, were also included in the input feature space through cyclical encoding, and the last 10% of the data, corresponding to 4 July 2022–12 April 2023, were used as the test set for model evaluation.

This encoding maps directional values onto the unit circle, transforming the angular variable into a continuous two-dimensional representation that enables regression models to learn directional trends smoothly across the 0°/360° boundary. After the prediction, the sine and cosine outputs were mapped back to the angular degrees using the arctangent function. This approach has been successfully adopted in other wind direction forecasting studies based on deep learning [20,21] and is particularly beneficial in transformer architectures, where the continuity and smoothness of the target variable enhance learning stability.

Following this preprocessing step, the forecasting models were implemented and configured for horizon-specific training. Four separate models were trained: one for each forecast horizon (1, 6, 12, and 24 h). Each model was optimized independently, receiving an input window whose length matched the respective horizon, and directly produced all forecast steps for that horizon (2, 12, 24, and 48 half-hour steps). This ensured that each model specialized in its forecast range, avoiding the limitations of a single model that jointly predicts all horizons.

The selection of the input features varies depending on the forecasting target. For wind-speed forecasting, the input variables included the recent history of wind speed, with a look-back window equal to the forecasting horizon (1, 6, 12, or 24 h), along with Temperature, Pyranometer, and Relative Humidity, while the target variable was wind speed.

For wind direction forecasting, the targets were the sine and cosine of the measured wind angles. The corresponding input variables included the recent history of these sine and cosine components together with Barometric Pressure as an additional meteorological predictor.

The feature selection process combines domain knowledge and empirical correlation analysis with lagged dependencies evaluated across multiple offsets to identify relevant time windows. Redundant or collinear predictors were excluded to maintain compact and informative input sets.

Hyperparameter tuning was primarily manual and supported by the early stopping of the validation loss to prevent overfitting. While the initial experimental plan included an Optuna-based search with 20 trials per model, the final configurations were stabilized through light manual adjustments. For tree-based models, the parameters included the learning rate, maximum depth, number of leaves (LightGBM), and iterations (CatBoost). For the CNN, the kernel size, number of filters, and learning rate are adjusted within a narrow range. For the TFT, the configurations included hidden size, number of attention heads, dropout rate, and learning rate. Deep learning models were trained using the Adam optimizer and early stopping to ensure convergence and generalization.

The Temporal Fusion Transformer (TFT) was implemented using the PyTorch Forecasting library (version 1.4.0), with hidden sizes between 4 and 16, 2–4 attention heads, dropout values of 0.2–0.3, and early stopping after 20–30 epochs (batch size 64). For wind speed forecasting, the model was trained using NormalDistributionLoss, whereas for wind direction forecasting, QuantileLoss was applied to sine and cosine targets. CatBoost models were trained with 100–150 iterations, learning rates between 0.12 and 0.25, and a maximum tree depth of 8. The LightGBM models used 100–200 boosting rounds, maximum depths of 5–8, learning rates of approximately 0.058–0.07, and 79 leaves. The multi-head CNN consisted of three parallel 1D convolutional branches (kernel sizes of 3, 5, and 7), each with 55 filters, followed by concatenation and a dense output layer. The CNN was trained using the Adam optimizer (learning rate = 0.0047) with an MSE loss function.

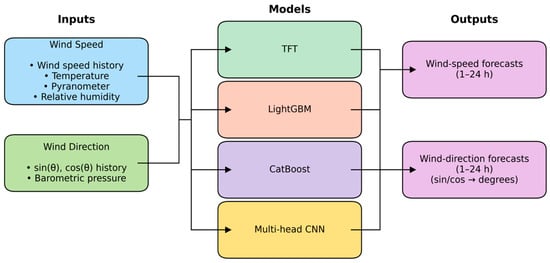

Figure 2 provides an overview of the proposed forecasting framework, illustrating the two input feature groups, the four machine learning models considered in this study, and the resulting multi-horizon predictions for wind speed and wind direction.

Figure 2.

Overall model architecture for the proposed multi–horizon forecasting framework.

4. Evaluation Metrics and Training Procedure

4.1. Evaluation Metrics

To assess the forecasting performance across different horizons and targets for both wind speed and wind direction, a combination of classical regression and angular error metrics was used, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Evaluation metrics.

The forecasting performance was assessed using a combination of classical regression and angular error metrics, where denotes the observed (actual) values and denotes the corresponding forecasted values. In all metrics, is the total number of observations, while for the angular error metrics, represents the observed angle, and the forecasted angle both expressed in degrees.

The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) measures the average absolute difference between the forecasted and observed values, providing an intuitive interpretation of the model’s average error in physical units. The Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) penalizes larger deviations more heavily than MAE, highlighting errors that may strongly affect short-term forecast reliability. The coefficient of determination (R2) measures how well the predicted values explain the variance of the observed data, with values closer to 1 indicating higher predictive accuracy. For the wind direction, the Angular Mean Absolute Error (MAEθ) computes the average angular difference between the predicted and actual directions, considering the circular nature of the data around the 0°/360° boundary. Similarly, the Angular Root Mean Squared Error (RMSEθ) squares the angular deviations before averaging, making it more responsive to large directional errors.

Together, these metrics provide a comprehensive understanding of model behavior, highlighting both its predictive accuracy and robustness over different time horizons and forecasting tasks.

4.2. Training Procedure

All models were trained using the same multivariate input–output structure, with the input sequence length adjusted according to the forecast horizon. Specifically, for the 1 h, 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h forecasts, the input window was aligned with the corresponding past interval, ensuring a consistent temporal context across all training configurations. The dataset was chronologically divided into 80% for training, 10% for validation, and 10% for testing.

Forecast performance was assessed using a per-step evaluation, where errors were averaged across all forecast steps within each horizon (e.g., all 48 half-hour steps for the 24 h horizon), allowing an analysis of how accuracy typically degrades as the forecast horizon increases. This approach provides a detailed view of short-term variability and helps identify horizons where model performance begins to deteriorate, which is particularly important for operational forecasting applications such as aviation and energy management.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Overview of Model Performance

All models were trained and evaluated on the same dataset, predicting wind speed and direction at 30-min resolution across multiple horizons (1 h, 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h, i.e., 2 to 48 forecast steps). The evaluation metrics used (MAE, RMSE, angular MAE, and angular RMSE) provided a comprehensive quantitative comparison of the ability of each model to capture both the magnitude and directionality of wind behavior across short- and medium-term forecast intervals.

All four evaluated models achieved satisfactory forecasting accuracy across the tested horizons, each exhibiting distinct strengths depending on the prediction interval and the target variable.

5.2. Wind Speed Forecasting

The comparison of forecasting accuracy across horizons, as shown in Table 4, indicates that LightGBM achieved the best performance at the 1 h horizon, confirming its capability to capture short-term local dependencies effectively. At the 6 h horizon, CatBoost slightly outperformed the other models, providing the most accurate wind speed predictions. For longer horizons (12 h and 24 h), the Temporal Fusion Transformer (TFT) exhibited the highest stability and accuracy, maintaining reliable performance as the forecast range increased. The multi-head CNN performed competitively at shorter horizons, but its accuracy degraded more rapidly than those of the other models at longer forecast intervals.

Table 4.

Wind speed performance metrics for all models and per forecasting horizon.

Overall, the results confirm that tree-based models are well-suited for short-term wind speed forecasting, whereas transformer-based architectures provide superior robustness and generalization for medium-term horizons. Table 4 presents the complete set of performance metrics for wind speed forecasting across all models and forecast horizons, including average values over forecast steps and aggregated scores over the full horizon, allowing a direct comparison of short-term and medium-term accuracies.

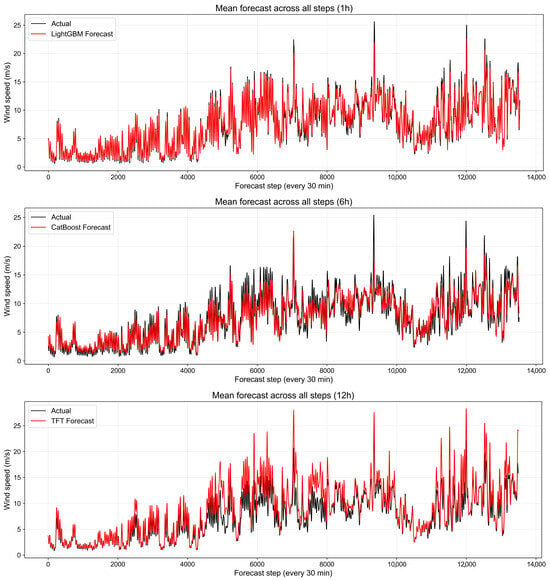

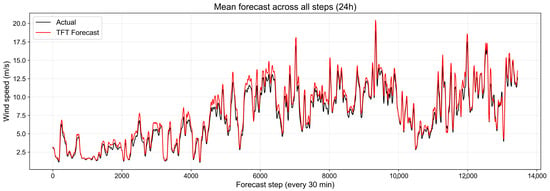

To complement the quantitative evaluation, Figure 3 illustrates the wind speed forecasts of the best-performing model for each horizon, highlighting the models’ ability to track short-term fluctuations and capture medium-term trends.

Figure 3.

Wind speed forecasting of the best model for all the horizons.

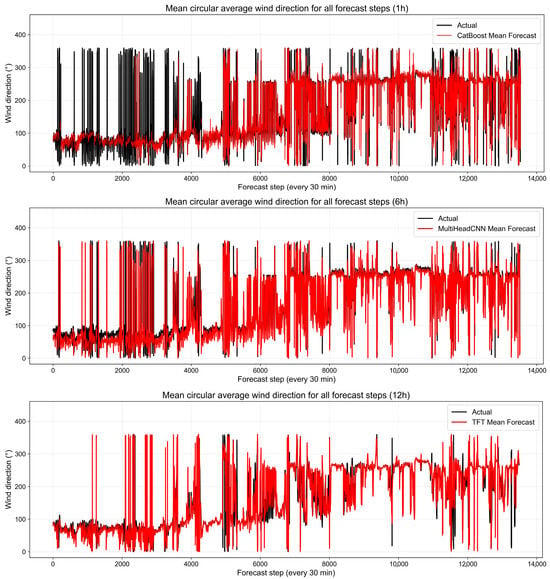

5.3. Wind Direction Forecasting

The comparative results for wind direction forecasting in Table 5 show that CatBoost achieved the best performance at the 1 h horizon, effectively capturing short-term directional variability. At the 6 h horizon, the multi-head CNN provided the most accurate predictions, outperforming both the gradient boosting models and the transformer-based approach. For longer horizons (12 h and 24 h), the Temporal Fusion Transformer (TFT) clearly dominated, delivering more stable and accurate angular forecasts than the other models.

Table 5.

Angular wind direction performance metrics for all models and per forecasting horizon.

Overall, the findings confirm a complementary pattern across horizons: CatBoost is best suited for very short-term forecasts, multi-head CNN excels at intermediate timescales, and TFT offers superior robustness and accuracy for medium-term wind direction prediction.

Following the numerical results in Table 5, Figure 4 presents time-series plots of the predicted versus observed wind direction for the best-performing model at each forecast horizon. These visualizations provide an intuitive view of short-term and medium-term forecast accuracy, illustrating each model’s ability to track directional changes and capture prevailing patterns over time.

Figure 4.

Wind direction forecasting of the best model for all the horizons.

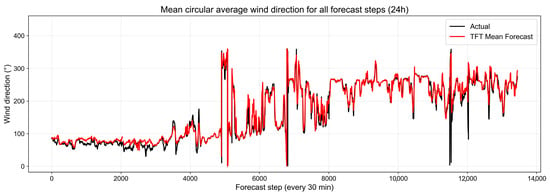

5.4. Visual Comparison with Wind Rose Diagrams

Figure 5 presents a visual comparison of the model forecasts using the wind rose diagrams generated for the test set period (4 July 2022–12 April 2023). The observed distribution revealed dominant W and E–NE wind components with secondary flows from the S–SW sector, consistent with the prevailing local climatology.

Figure 5.

Wind roses based on the test set period (4 July 2022–12 April 2023) for the actual data and the best model for each forecasting horizon.

At very short horizons, the tree-based models (LightGBM for 1 h wind speed, CatBoost for 1 h wind direction, and CatBoost for 6 h wind speed) reproduced the main directional structure with compact and accurate flow representation. The multi-head CNN captured the 6 h directional distribution more effectively than the other models, confirming its relative advantage at this intermediate horizon.

At medium and longer horizons (12 h and 24 h), the Temporal Fusion Transformer (TFT) provided the most consistent representation of the observed test-set wind rose, accurately reproducing secondary directional modes and the overall sectoral distribution of wind speed. In contrast, gradient-boosting models tended to oversimplify the directional pattern at longer horizons, whereas CNN showed increased dispersion.

This analysis highlights the value of complementing quantitative error metrics with qualitative visualization tools, such as wind rose diagrams, which offer additional insight into the spatial and directional consistency of forecasts.

Although LightGBM achieved the lowest MAE for wind speed at the 1 h horizon, CatBoost produced the most accurate directional forecasts (angular MAE = 8.66°). Because wind roses depict both wind speed and directional variability, the selection of CatBoost for 1 h provides a more representative visualization of the joint wind behavior. At the 6 h horizon, CatBoost yielded the best wind speed forecasts, whereas the Multi-head CNN produced the lowest directional errors, making the combination of the two models more suitable for capturing overall wind characteristics at this timescale. For the 12 h and 24 h horizons, TFT was superior in both magnitude and direction, and was therefore selected for the corresponding wind rose plots.

5.5. Comparison

Table 6 presents a comparison between the forecasting results obtained in this study and the typical values reported in the literature (2020–2024) for wind speed and wind direction. Literature benchmarks were drawn from high-quality peer-reviewed studies to ensure fair and meaningful performance comparisons.

Table 6.

Comparison with other related research.

5.6. Discussion

The comparative analysis reveals that the relative strengths of the examined models depend strongly on both the forecast horizon and the target variable.

For wind speed, LightGBM was the most effective in the very short term (1 h), confirming its ability to capture localized temporal dependencies. At the 6 h horizon, CatBoost achieved the lowest overall errors, whereas the Temporal Fusion Transformer (TFT) clearly dominated at the 12 h and 24 h horizons. These findings indicate that although gradient boosting methods perform well for short-term prediction, transformer-based architectures offer superior robustness and generalization for medium-term horizons.

For wind direction, the results showed a more complex pattern of performance. CatBoost achieved the best short-term accuracy (1 h), whereas the multi-head CNN performed best at the intermediate 6 h horizon. At longer horizons (12 and 24 h), TFT provided the most stable and accurate directional forecasts, whereas the tree-based and convolutional models gradually lost precision. This confirms that boosting models are optimal for very short-term angular prediction, CNNs can effectively capture intermediate-horizon structures, and transformers are better suited for maintaining accuracy over extended lead-times.

These results underscore the potential of hybrid approaches: gradient boosting models can serve immediate operational needs (e.g., aviation scheduling), CNNs add value at intermediate horizons, and transformers provide reliable medium-term forecasts for energy management and flight planning.

Recent reviews [1] have emphasized the growing dominance of ensemble and deep learning architectures, particularly CNNs and transformers, in renewable energy forecasting. Concurrently, emerging graph-based and reinforcement learning methods [28] have highlighted new directions for incorporating spatiotemporal dependencies across multiple sites. These results are consistent with these trends.

In addition to the main predictors, the additional meteorological variables used in our models, such as temperature, solar irradiance, relative humidity, and barometric pressure, also influence the evolution of wind speed and direction. These factors affect atmospheric stability, air density, and pressure patterns, which play an important role in shaping local wind behavior, especially in coastal areas with complex terrains such as Crete.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that advanced machine learning approaches can deliver accurate and operationally relevant forecasts of wind speed and direction in a complex coastal Mediterranean setting. Among the four evaluated models, LightGBM provided the best short-term wind speed accuracy at the 1 h horizon, while CatBoost achieved the most accurate wind speed forecasts at 6 h. At longer horizons (12–24 h), the Temporal Fusion Transformer (TFT) consistently achieved superior performance for wind speed. For wind direction, CatBoost excelled in the very short term (1 h), the Multi-head CNN was most effective at the 6 h horizon, and the TFT dominated at 12–24 h. All models successfully reproduced the dominant W and E–NE wind patterns observed in the test set, with the TFT showing the closest agreement to secondary modes at longer horizons. Specifically, LightGBM achieved the lowest MAE for 1-h forecasts (1.89 m/s), CatBoost performed best at 6 h (3.12 m/s), and the TFT model outperformed all others at 12–24 h (3.44–3.38 m/s). For wind direction, the lowest angular MAE values were 8.66°, 30.71°, 35.29°, and 25.65° at 1, 6, 12, and 24 h, respectively.

Compared to the recent literature, the best-performing models in this study achieved measurable improvements in wind speed accuracy. These results confirm the feasibility of deploying ML-based forecasting frameworks to support aviation safety, renewable energy scheduling, and infrastructure planning in coastal airport zones.

Future work will explore ensemble approaches that combine the complementary strengths of gradient boosting, convolutional, and transformer-based models, integrate spatial information from additional stations or reanalysis products, and incorporate probabilistic forecasting to improve decision-making under uncertainty. Further research can also investigate graph neural network-based ensembles, advanced CNN–LSTM hybrids, and emerging quantum machine learning algorithms, which have recently been shown to deliver low forecasting errors and strong generalization capabilities [14,18,28,29].

In addition, future studies may consider cross-attention mechanisms for multimodal data fusion, including not only sensor-derived variables but also textual observations from human operators, enabling the integration of qualitative, human-like descriptions alongside quantitative sensor inputs. Further directions include physics-informed or hybrid modeling to embed domain constraints, and explainable attention-based visualization to improve interpretability and trust in operational settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.B. and Y.K.; methodology, K.B. and S.P.; software, K.B. and S.P.; validation, K.B. and S.P.; formal analysis, K.B.; investigation, K.B. and S.P.; resources, K.B.; data curation, K.B.; writing—original draft preparation, K.B.; writing—review and editing, K.B., S.P., E.K., F.M. and Y.K.; visualization, K.B.; supervision, Y.K.; project administration, E.K., F.M. and Y.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from the project “Enhancing resilience of Cretan power system using distributed energy resources (CResDER)” (Proposal ID: 03698), financed by H.F.R.I.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying the results presented in this study are publicly available at https://data.apdkritis.gov.gr/dataset/meteorologika-dedomena-meteorologikoy-stathmoy-roysohoria, accessed on 3 March 2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, Z.; Guo, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zuo, Z. A Comprehensive Review of Wind Power Prediction Based on Machine Learning: Models, Applications, and Challenges. Energies 2025, 18, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benti, N.E.; Chaka, M.D.; Semie, A.G. Forecasting Renewable Energy Generation with Machine Learning and Deep Learning: Current Advances and Future Prospects. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Chen, Q.; Jiang, T.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Xi, W.; Huang, S. Review of AI-Based Wind Prediction within Recent Three Years: 2021–2023. Energies 2024, 17, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajibade, S.-S.M.; Bekun, F.V.; Adedoyin, F.F.; Gyamfi, B.A.; Adediran, A.O. Machine Learning Applications in Renewable Energy (MLARE) Research: A Publication Trend and Bibliometric Analysis Study (2012–2021). Clean Technol. 2023, 5, 497–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, K.L.; Shaker, H.R. Wind Power Forecasting Using Machine Learning: State of the Art, Trends and Challenges. In Proceedings of the IEEE 8th International Conference on Smart Energy Grid Engineering (SEGE), Oshawa, ON, Canada, 12–14 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, W.-C.; Hong, C.-M.; Tu, C.-S.; Lin, W.-M.; Chen, C.-H. A Review of Modern Wind Power Generation Forecasting Technologies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, S.B.; de Oliveira, R.C.L.; Affonso, C.M. Short-term Wind Speed Forecasting using Machine Learning Algorithms. In Proceedings of the IEEE Madrid PowerTech, Madrid, Spain, 28 June–2 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.-Y. LightGBM: A Highly Efficient Gradient Boosting Decision Tree. In Proceedings of the 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2017), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Prokhorenkova, L.; Gusev, G.; Vorobev, A.; Dorogush, A.V.; Gulin, A. CatBoost: Unbiased Boosting with Categorical Features. In Proceedings of the 32nd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2018), Montréal, QC, Canada, 2–8 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, R.; Cerveira, A.; Pires, E.J.S.; Baptista, J. Advancing Renewable Energy Forecasting: A Comprehensive Review of Renewable Energy Forecasting Methods. Energies 2024, 17, 3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.B.; Nookesh, V.M.; Saketh, B.S.; Syama, S.; Ramprabhakar, J. Wind Speed Prediction Using Deep Learning-LSTM and GRU. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Smart Electronics and Communication (ICOSEC), Trichy, India, 7–9 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Su, H.; Wang, R.; Deng, J.; Wang, Y.; Guo, W.; Li, R. Short-term forecast method of wind power output based on multi-scale CNN-LSTM in extreme weather. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2025, 172, 111191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazakis, K.; Katsigiannis, Y.; Stavrakakis, G. One-Day-Ahead Solar Irradiation and Windspeed Forecasting with Advanced Deep Learning Techniques. Energies 2022, 15, 4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazakis, K.; Katsigiannis, Y.; Schetakis, N.; Stavrakakis, G. One-Day-Ahead Wind Speed Forecasting Based on Advanced Deep and Hybrid Quantum Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the Frontiers of Artificial Intelligence, Ethics, and Multidisciplinary Applications (FAIEMA 2023), Athens, Greece, 25–26 September 2023; Farmanbar, M., Tzamtzi, M., Verma, A.K., Chakravorty, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Blazakis, K.; Schetakis, N.; Bonfini, P.; Stavrakakis, K.; Karapidakis, E.; Katsigiannis, Y. Towards Automated Model Selection for Wind Speed and Solar Irradiance Forecasting. Sensors 2024, 24, 5035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, B.; Arık, S.Ö.; Loeff, N.; Pfister, T. Temporal fusion transformers for interpretable multi-horizon time series forecasting. Int. J. Forecast. 2021, 37, 1748–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; He, S.; Liu, H.; Chen, J.; Dong, H. WindTrans: Transformer-Based Wind Speed Forecasting Method for High-Speed Railway. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 4947–4963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wu, J.; Wang, X.; Yuan, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, G. Multi-Scale Spatio-Temporal Transformer-Based Imbalanced Longitudinal Learning for Glaucoma Forecasting from Irregular Time Series Images. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2024, 29, 2859–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Wang, S.; Xu, X.; Li, R.; Shi, P. GAOformer: An adaptive spatiotemporal feature fusion transformer utilizing GAT and optimizable graph matrixes for offshore wind speed prediction. Energy 2024, 292, 130404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Li, S. ABFL: Angular boundary discontinuity free loss for arbitrary oriented object detection in aerial images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Yang, G.; Xing, H.; Shi, Y.; Liu, T. Temporal Convolutional Network with Attention Mechanisms for Strong Wind Early Warning in High-Speed Railway Systems. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modé, P.; Demartino, C.; Georgakis, C.T.; Lagaros, N.D. Short-Term Extreme Wind Speed Forecasting Using Dual-Output LSTM-Based Regression and Classification Model. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2025, 259, 106035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Ye, X.W.; Guo, Y. A multistep direct and indirect strategy for predicting wind direction based on the EMD-LSTM model. Struct. Control. Health Monit. 2023, 2023, 4950487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z. Short-Term Nacelle Orientation Forecasting Using Improved ICEEMDAN and LSTM Networks. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9, 780928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, D.; Mendonça, F.; Mostafa, S.S.; Morgado-Dias, F. Low Tropospheric Wind Forecasts in Aviation: The Potential of Deep Learning for Terminal Aerodrome Forecast Bulletins. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2024, 181, 1781–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugware, F.W.; Sigauke, C.; Ravele, T. Evaluating Wind Speed Forecasting Models: A Comparative Study of CNN, DAN2, Random Forest and XGBOOST in Diverse South African Weather Conditions. Forecasting 2024, 6, 672–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuillan, K.A.; Allen, G.H.; Fayne, J.V.; Gao, H.; Wang, J. Estimating Wind Direction and Wind Speed over Lakes with SWOT and Sentinel-1 Satellite Observations. Earth Space Sci. 2025, 12, e2024EA003971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Chen, Q.; Jiang, T.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Xi, W.; Huang, S. Applying Ensemble Models Based on Graph Neural Network and Reinforcement Learning for Wind Power Forecasting. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.16591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhussan, F.A.; Alhussan, S.A.; Kumar, A. DWDTO-Based Optimized Hybrid Deep Learning Ensemble Model for Accurate Wind Power Forecasting. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 11, 1174910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).