Abstract

High brittleness severely restricts the practical use of nanocrystalline cores in low-frequency power electronics. To enhance mechanical strength and facilitate cutting and transportation, curing techniques are commonly employed, yet their influence on the magnetic properties of the cores remains unclear. In this work, three curing techniques, namely, fluid-phase adhesive curing, gel-phase adhesive curing, and vacuum-evacuated gel-phase adhesive curing (VGAC), are applied to prepare cores with varying curing degrees. The magnetic properties of them are quantitatively compared with those of uncured cores within the range of 50–550 Hz. Results show that all three curing techniques demonstrably reduce the eddy current losses of the cores. Specifically, the VGAC-based core exhibits a 50% reduction in eddy current loss compared to the uncured core at 550 Hz and 0.8 T. Meanwhile, high saturation flux density is retained in all cured samples. However, curing also reduces permeability and raises coercivity. Furthermore, cured cores demonstrate increased hysteresis and residual losses, leading to higher total losses. The relationship between core losses and temperature rise is also investigated to provide important guidance for the safe operation of cured cores. In addition, microscopic images under 200× magnification are presented to elucidate the mechanisms underlying these observed influences.

1. Introduction

Compared with traditional silicon steel and ferrites, nanocrystalline soft magnetic materials offer several advantages for low-frequency electronics. Firstly, nanocrystalline soft magnetic materials have higher permeability and lower coercivity than silicon steel [1]. Their initial permeability μ0 can reach the 105 level, while their coercivity Hc is below 1 A/m, which reduces magnetization energy and core losses during cyclic excitation. Secondly, compared with ferrites, they provide a higher saturation flux density Bs, with Bs exceeding 1.2 T, enabling operation at higher induction without premature saturation; this supports device miniaturization and light-weighting and improves power density under the same thermal constraints [2]. Thirdly, the co-existence of high permeability, low core loss, and high Bs—combined with excellent thermal stability—provides clear advantages for long-term, high-efficiency operation in low-frequency electronics. As a result, power transformers, current transformers, and common-mode inductors designed with nanocrystalline materials can be made more efficient and more compact [3,4,5]. Among various material formulations, Fe-based nanocrystalline alloys are especially prominent for their excellent magnetic properties and cost-effectiveness and have thus become mainstream choices for industrial low-frequency power electronics systems [6].

These outstanding magnetic properties have attracted substantial research attention. Through coordinated optimization of composition, annealing, and manufacturing processes, magnetic properties including permeability, coercivity, and core losses of Fe-based nanocrystalline materials have been significantly improved to meet diverse application requirements. Elemental doping (e.g., Si, B, Cu, Nb) improves magnetic characteristics by controlling grain size and phase stability, which influences domain-wall motion and spin rotation [7]. For example, Cu promotes the nucleation and uniform dispersion of α-Fe nanograins, while Nb inhibits grain coarsening and stabilizes the nanocrystalline phase; jointly, these effects lower Hc by ~40–60%, raise μ by roughly 1.5–2×, and slightly improve Bs. Stress annealing is preferred when adjusting permeability, DC-bias behavior, and frequency response, which benefits current transformers and high-precision sensors [8,9]. Magnetic-field annealing is more suitable when low coercivity and high permeability are prioritized, as in power transformers and inductors [10,11]. In addition, nanocrystalline ribbons generate substantial eddy current losses due to fringing flux at discrete air gaps. To mitigate these losses, lamination combined with interlayer insulation is commonly employed. Various interlayer insulation methods, such as resin coating, oxidation treatment, and SiO coating have been proposed, among which oxidation treatment can reduce eddy current losses by approximately 30% [12]. In [13], an epoxy resin was employed as an insulating matrix coated on the surface of nanocrystalline ribbons, and the cores were assembled using a cross-lamination splicing process, which effectively shortened eddy current paths and reduced eddy current loss. Recently, a novel crushing technique has demonstrated potential for significant eddy current loss reduction [14]. Nevertheless, this approach considerably decreases the permeability of ribbons to less than one third of the original value, or even less, due to disrupted magnetic path continuity and increased effective gaps [15,16]. Additionally, controlled crushing processes have shown feasibility in tailoring the relative permeability within the range of 800 to 3000 by adjusting applied pressure patterns and magnitudes [17].

In addition to the optimization of magnetic properties, addressing engineering challenges of nanocrystalline materials, mainly the poor mechanical strength, is critical for their practical application. In Refs. [18,19], nanocrystalline ultra-thin ribbons exhibit high brittleness. Industrial curing techniques, such as epoxy resin impregnation and surface coating, have been commonly adopted to enhance mechanical robustness and provide interlayer electrical insulation, thereby facilitating machining processes such as electrical discharge machining (EDM) [20,21,22]. In [23], the mechanical strength of nanocrystalline cores was enhanced by applying an external epoxy coating and adding a protective case, thereby preventing damage to the nanocrystalline cores during operating. Despite these advantages, curing processes inevitably influence the magnetic performance of nanocrystalline ribbons. Although previous studies have compared core losses of cured and uncured cores at specific frequencies, systematic frequency-dependent analyses and comprehensive evaluations of magnetic parameters have not yet been reported [24]. Furthermore, the underlying mechanisms through which different curing techniques affect magnetic properties remain insufficiently explored, especially in low-frequency applications.

In this paper, Fe-based nanocrystalline cores prepared by three curing techniques, namely, fluid-phase adhesive curing (FAC), gel-phase adhesive curing (GAC), and vacuum-evacuated gel-phase adhesive curing (VGAC), are investigated. Based on the low-frequency application background, the magnetic properties directly determining the practical performance, including initial permeability, maximum permeability, coercivity, saturation flux density, and loss densities (both total losses and loss separation) of the three associated cured cores are characterized and compared quantitatively with an uncured core within the range of 50–550 Hz, and 0–0.8 T. In addition, the microstructural characterization results are employed to elucidate the mechanism by which curing techniques influence magnetic properties by modifying adhesive phase distribution and resistivity. These studies quantitatively reveal the impact of different curing techniques on the magnetic properties of nanocrystalline cores and provide a theoretical basis for material selection and process optimization in the design of low-frequency magnetic components for power electronics.

2. Curing Techniques for Nanocrystalline Cores

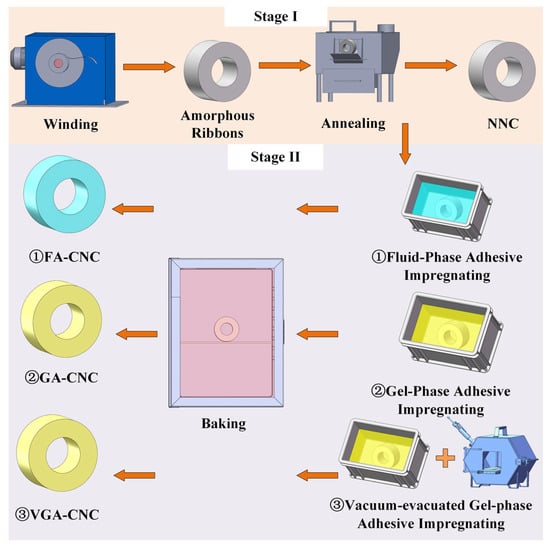

The fabrication process of nanocrystalline toroidal cores involves winding, annealing, and curing, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Manufacturing process of toroidal cores.

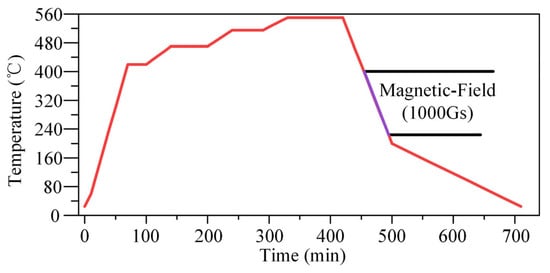

In Stage I, amorphous ribbons (~20 μm thickness) with a composition of Fe73.5Cu1Nb3Si15.5B7 are wound (typically ~300 turns of amorphous ribbons) into toroidal shapes and annealed to achieve nanocrystallization (the annealing process shown in Figure 2), resulting in a nanocrystalline normal core (NNC, annealed without curing and incompatible with EDM).

Figure 2.

The annealing process.

In Stage II, three curing methods, namely, FAC, GAC, and VGAC, are applied to address the brittleness of NNC in stage I. These techniques also enhance electrical resistivity and, consequently, insulation performance.

For FAC, the cores are immersed in water-based alkyd resin adhesive for 30 min and cured by baking at 100 °C for 2 h, resulting in fluid-phase adhesive cured nanocrystalline core (FA-CNC). FAC slightly increases mechanical strength and successfully makes FA-CNC preserve magnetic properties after annealing, but FA-CNC is also incompatible with EDM. For GAC, cores are immersed in an epoxy resin and curing agent mixture for 10 min, then cured at 150 °C for 5 h, producing gel-phase adhesive cured nanocrystalline cores (GA-CNC). GAC improves mechanical strength, making GA-CNC suitable for shape customization through EDM. As for VGAC, it uses the same adhesive as GAC but adds a vacuum impregnation step in a vacuum chamber for 20 min after the 10 min immersion, followed by curing at 150 °C for 2 h. This ensures deeper adhesive penetration, leading to better insulation and higher resistivity. The resulting product is referred to as a vacuum-evacuated gel-phase adhesive cured nanocrystalline core (VGA-CNC). VGA-CNC is also suitable for shape customization through EDM.

In addition, taking advantage of the EDM machinability of GA-CNC and VGA-CNC, a shape-customization stacked core manufacturing process is introduced.

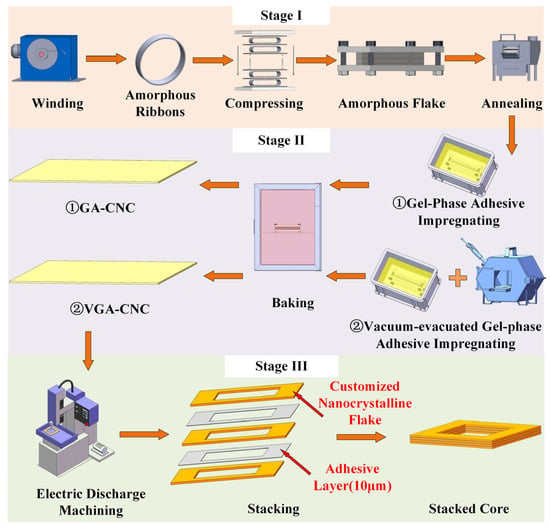

The manufacturing process of stacked cores involves the preparation of nanocrystalline flakes, curing of the flakes, shape customization with EDM, and stacking, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Manufacturing process for stacked cores.

In Stage I, amorphous ribbons are also wound into toroidal shapes, but only 1–5 turns of amorphous ribbons, so that they can be compressed into flakes using a dedicated mold. They are then annealed to achieve nanocrystallization (the annealing process shown in Figure 2), resulting in nanocrystalline flakes.

In Stage II, two curing methods, namely, GAC, and VGAC, are applied to address the brittleness of the annealed nanocrystalline flakes in Stage I. The process of GAC and VGAC are identical to those described above, resulting in EDM-machinable GA-CNC and VGA-CNC.

In Stage III, the GA-CNC and VGA-CNC are processed into the required core geometries and dimensions using EDM. These customized flakes are subsequently stacked into laminated cores utilizing 10 μm thick double-sided adhesive films.

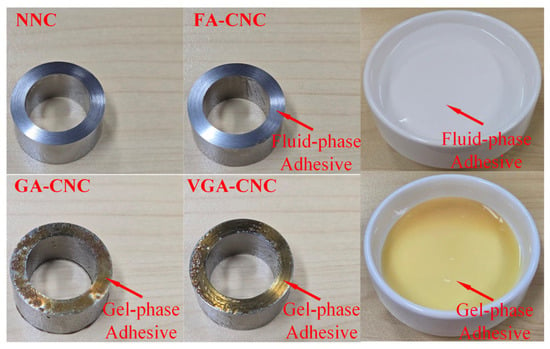

For the evaluation of magnetic properties in this study, four types of toroidal cores with dimensions of 20 × 30 × 15 mm: NNC (annealed without curing), FA-CNC, GA-CNC, and VGA-CNC, are prepared as shown in Figure 4. The manufacturing process for the nanocrystalline cores used in experiment is shown in Figure 1. The curing degree can be reflected by electrical resistivity, which means that higher resistivity indicates a higher curing degree. The higher the resistivity, the higher the degree of curing. The measurement of resistivity is carried out using the four-point probe method for the flake nanocrystalline. The measured resistivities are 1.49 × 10−6 Ω·m for NNC, 1.60 × 10−6 Ω·m for FA-CNC, 2.70 × 10−6 Ω·m for GA-CNC, and 3.00 × 10−6 Ω·m.

Figure 4.

Four types of nanocrystalline cores.

3. Magnetic Property Analysis and Comparison

3.1. B-H Curve

The B–H curve offers a comprehensive characterization of magnetic properties, including permeability, saturation flux density, coercivity, and hysteresis losses, which are the focus of this study. For the four nanocrystalline toroidal cores, B–H curves are measured using a soft magnetic DC tester MATS-2010SD (Linkjoin, Loudi, China) based on the volt-ampere method.

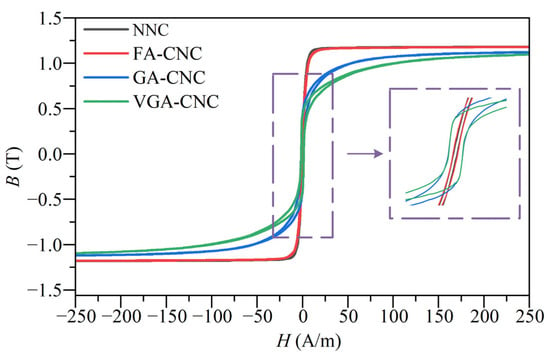

Figure 5 illustrates the comparative B–H curves for the four cores. As observed, all three cured cores exhibit larger hysteresis loop areas compared to the NNC, indicating higher hysteresis losses. Moreover, the hysteresis loss tends to increase with the degree of curing. The curing techniques also adversely affect the initial permeability, maximum permeability, and coercivity, particularly evident in the GA-CNC and VGA-CNC, as quantitatively summarized in Table 1. This deterioration can be attributed to the adhesive material obstructing the mobility and rotation of magnetic domains during both magnetization and demagnetization processes. Fortunately, despite these adverse effects, the advantage of high saturation flux density remains preserved; the variation in saturation flux density among the four cores is less than 0.05 T.

Figure 5.

B-H curve measurement.

Table 1.

Magnetic properties of cores under test.

3.2. Loss Density Versus Peak Magnetic Flux Density

Core losses directly influence the efficiency, thermal safety, and reliability of magnetic cores in practice. For quantitative analysis, experiments are conducted using a soft magnetic AC dynamic tester RikenDenshi (Tokyo, Japan), illustrated in Figure 6a. The principle of core loss density measurement based on the dual-winding method can be expressed mathematically as

where T is the period of dynamic magnetization, mc is the mass of the core, Ae is the effective cross-sectional area, and Le is the magnetic circuit length [25].

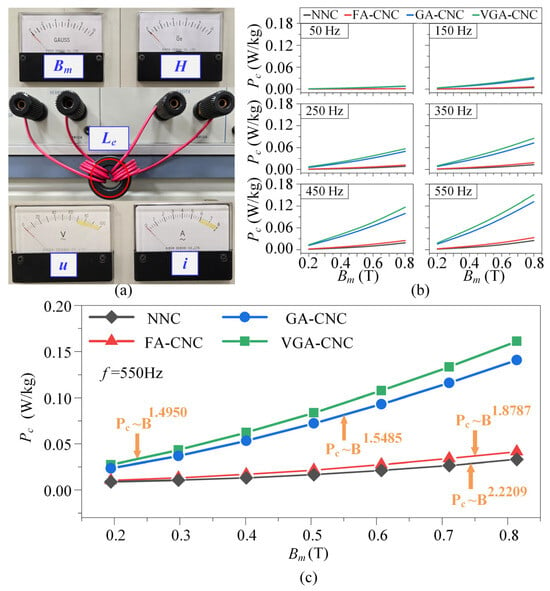

Figure 6.

Core loss results (a) experimental setup (b) core loss of four cores (c) the variation law of core loss with Bm.

Considering typical operating conditions of nanocrystalline cores in power electronics, measurements are conducted within 50–550 Hz frequency and 0.2–0.8 T peak magnetic flux density Bm. The measured Pc values for four nanocrystalline cores under these conditions are presented in Figure 6b. As expected, the Pc values generally increase with higher f and higher Bm. As Bm increases, the difference in Pc between highly cured cores (GA-CNC and VGA-CNC) and the less-cured cores (NNC and FA-CNC) becomes significantly more pronounced. To quantitatively analyze this phenomenon, the relationship between Pc and Bm is fitted using the Steinmetz equation as

where Cm, a, and β are experimentally determined parameters, and Dc is the material density. In Figure 6c, the fitted loss curves exhibit a power-law relationship with Bm, resulting in β of 2.2209 for NNC, 1.8787 for FA-CNC, 1.5485 for GA-CNC, and 1.4950 for VGA-CNC, respectively. These values indicate that at the same f, the influence of Bm on Pc becomes stronger as the curing degree increases. Specifically, Pc in FA-CNC remains relatively close to that in NNC. At 0.8-T Bm, Pc in FA-CNC is only approximately 29.1–32.3% higher than in NNC across the tested frequency range. However, GA-CNC and VGA-CNC exhibit significantly higher Pc values compared to NNC and FA-CNC. At 0.8-T Bm, Pc values in GA-CNC and VGA-CNC cores can exceed those in NNC by up to six times.

3.3. Loss Separation

In this section, the Pc values of the four cores are separated and analyzed to identify which components are elevated due to the curing techniques, thereby contributing to the overall increase in core loss. The underlying causes of these changes are also investigated.

The total loss Pc consists of hysteresis loss Ph, eddy current loss Pe, and excess loss Pex.

To determine Ph at a specific f and Bm, it is first measured at 30 Hz. This value is then divided by 30 and multiplied by the desired frequency to estimate the Ph at other frequencies. This linear relationship between Ph and f is valid within the frequency range considered in this study and is widely adopted in industrial practice for core loss estimation.

The Pe is calculated through

where d is the ribbon thickness, and ρc is the electrical resistivity. Then, Pex is the result of Pc minus Ph and Pe.

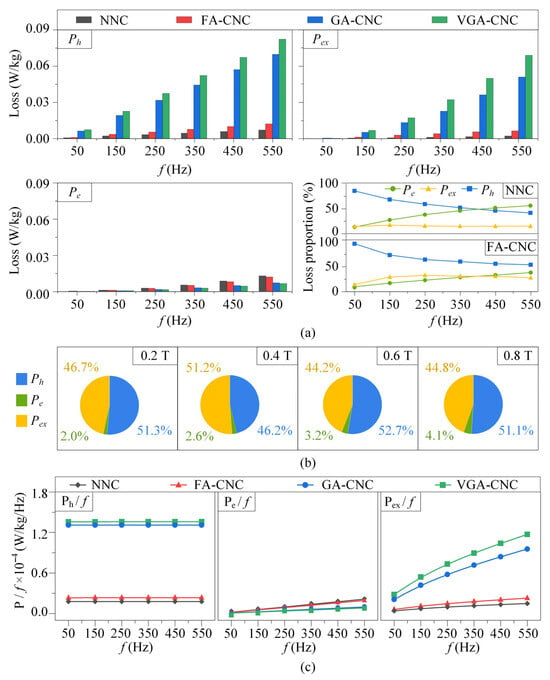

Across the tested frequency and flux density ranges, it is observed that the comparison of separated loss components among the four cores exhibit consistent trends. The hysteresis loss and excess loss increase with curing degree. Fortunately, the eddy current loss decreases as the curing degree increases. Therefore, the increase in total core loss in cured cores is primarily due to the elevated hysteresis loss and excess loss.

Figure 7 shows the separated loss components and their proportions for all cores. In Figure 7a, at the fixed 0.8 T, for GA-CNC and VGA-CNC, Pe can be up to 50% lower than for NNC, demonstrating strong suppression of eddy current loss by curing. The reduction in Pe is mainly attributed to the increase in resistivity in all three cured cores. According to Equation (3), Pe is inversely proportional to the electrical resistivity, which explains why the eddy current loss is lower in the cured cores. Meanwhile, Ph can be up to six times higher than NNC because the B–H loop areas of the cured cores in Figure 5 are larger than that of uncured NNC, indicating greater energy dissipation during the magnetization process. Pex in highly cured GA-CNC and VGA-CNC can exceed NNC by more than ten times. The reason for the increase in Pex is described in the following part regarding Figure 8. The fourth panel of Figure 7a highlights that the ranking of loss components can change with f. For NNC, as f increases, Pe grows rapidly and overtakes Ph at around 400 Hz, becoming the largest component. In contrast, for FA-CNC, although Pe increases with f, it never surpasses Ph within the measured range, indicating that curing effectively restricts the growth of Pe. Figure 7b uses VGA-CNC as an example to illustrate that the conclusions regarding the f dependence of loss components hold across 0.2–0.8 T. As shown, the proportions of Ph, Pe, and Pex change very little with increasing Bm. Figure 7c displays the normalized loss densities Ph/f, Pe/f, and Pex/f as functions of f, showing that within our tested low-frequency range, Ph/f remains constant, Pe/f varies linearly with f, and Pex/f follows a square-root dependence on f, which agrees well with the expected power-law relationships of the three separated losses.

Figure 7.

Core loss separation results: (a) Ph, Pe, Pex, and respective proportions at fixed 0.8 T with varying f. (b) The variation law of loss proportions of VGA-CNC at fixed 550 Hz with varying Bm (c) relationship between Ph/f, Pe/f, Pex/f, and frequency at fixed 0.8 T.

Figure 8.

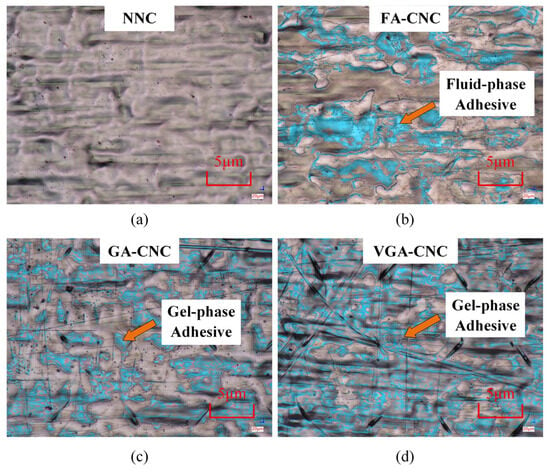

Microscopic magnification image: (a) Microscopic image of NNC. (b) Microscopic image of FA-CNC. (c) Microscopic image of GA-CNC. (d) Microscopic image of VGA-CNC.

Figure 8 shows CCD microscopy performed at 200× magnification in order to observe the internal adhesive distribution in different samples. The images reveal that NNC has no adhesive coverage, FA-CNC contains sparsely distributed fluid-phase adhesive, GA-CNC exhibits scattered gel-phase adhesive, and VGA-CNC shows a denser distribution of gel-phase adhesive. Accordingly, the adhesive used in all three curing techniques increases the resistivity of the cured cores and consequently reduces Pe. However, at low frequencies, Pex is primarily caused by the magnetic after-effect. The magnitude of excess loss is strongly influenced by factors such as the obstruction of domain wall motion by impurities. The introduced adhesive contributes to this obstructive effect, leading to a more pronounced magnetic after-effect, and thus results in higher Pex.

3.4. Thermal Analysis

The temperature rise caused by core losses plays a critical role in ensuring the stable and safe operation of magnetic cores. If the core temperature exceeds the maximum operating threshold, it may result in degradation of magnetic properties, increased losses, and even structural failure. In this study, the maximum allowable operating temperature of the cores is 125 °C.

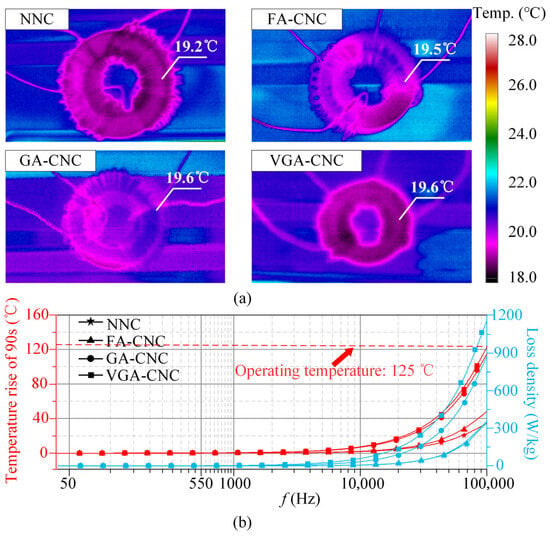

The core temperature is primarily determined by the internal core losses, which in turn affect magnetic properties, core losses, structural stability, and operational safety. Figure 9a shows thermal images of four different cores after 90 s of operation at 550 Hz and 0.8 T. The results indicate that the temperature rise is merely less than 2 °C above the ambient temperature of 18 °C. Figure 9b presents the variation in core temperature rise and core loss with frequency at 0.8 T. It can be seen that the temperature rise in the VGA-CNC core reaches 125 °C at 95 kHz only when operating for 90 s. As shown in Table 2, the same risk is observed for operation times of 300 s for 50 kHz and 600 s for 30 kHz, respectively. In contrast, the temperature of VGA-CNC core, which is associated with the highest losses, remains at 23 °C after 600 s at 550 Hz. Therefore, within the frequency range of 50–550 Hz investigated in this study, there is no thermal risk, and the cores can be used safely without concerns of overheating.

Figure 9.

Thermal observation and analysis (a) thermal image of four cores at 550Hz and 0.8T (b) the variation laws of loss density and temperature rise with frequency at 0.8 T.

Table 2.

The temperature performance of VGA-CNC at 0.8 T.

4. Conclusions

This paper investigated the influence of three curing techniques on the low-frequency magnetic properties of nanocrystalline cores and provided explanations for the underlying mechanisms. Firstly, the machinability differences among three curing techniques were reveled. Fe-based nanocrystalline cores prepared by three curing techniques, namely, FAC, GAC, and VGAC, are investigated. FAC is incompatible with EDM. In contrast, GAC and VGAC make nanocrystalline cores suitable for complex shape customization via EDM, which is crucial for practical core design in applications.

Secondly, the magnetic properties of the cured cores were systematically evaluated. The magnetic properties, including initial permeability, maximum permeability, coercivity, saturation flux density, and loss densities (both total losses and loss separation) of the three associated cured cores are characterized and compared quantitatively with an uncured core within the range of 50–550 Hz, and 0–0.8 T. These quantitative analyses reveal the influence of curing techniques on magnetic properties of the cores, addressing a gap in systematic research in this area.

Thirdly, the effect of curing techniques on eddy current loss suppression was demonstrated. Results show that curing techniques reduce eddy current losses of the cores, primarily due to the adhesive used in all three curing techniques increasing the resistivity of the cured cores. Especially at 550 Hz and 0.8 T, the eddy current loss in VGAC-based cores is reduced by 50% compared to uncured cores. This reduction in eddy current loss is beneficial for improving energy efficiency, mitigating heat generation, and enabling more compact or higher-power-density magnetic designs in low-frequency applications.

Fourthly, the mechanism behind the influence of curing techniques on magnetic properties was elucidated. High saturation flux density is retained across all cured samples, and the other magnetic properties of FAC-based cores also remain largely preserved. However, GAC and VGAC significantly reduce permeability and raise coercivity. The adhesive used in curing hinders the motion and rotation of magnetic domains, contributing to lower permeability. Cured cores also exhibit higher hysteresis and excess losses within 50–550 Hz, leading to higher total core losses. Enlarged B-H loop areas in cured samples indicate increased hysteresis loss. The adhesive induces a more pronounced magnetic after-effect, leading to increased excess loss. These findings clarify the trade-off introduced by curing techniques: while machinability and eddy current suppression are improved, additional hysteresis and excess losses must be considered. This mechanism-level understanding provides useful guidance for selecting appropriate curing techniques according to different design priorities.

Finally, thermal safety assessment and operational guidance for the cured cores were investigated. Thermal imaging analysis confirms that although curing increases total core loss, the temperature rise within the studied low-frequency range (50–550 Hz) is minimal (approximately 2 °C) and remains well below the risky threshold. This finding provides essential guidance for the safe and reliable operation of cured nanocrystalline cores under low frequency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.W. and L.J.; validation, F.W. and Q.Z.; formal analysis, F.W., Q.Z., and S.N.; writing—original draft preparation, F.W. and Q.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.L. and L.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Jiangyin-SUSTech Innovation Fund, grant number OR2404021.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ruiz-Robles, D.; Moreno-Goytia, E.L.; Venegas-Rebollar, V.; Salgado-Herrera, N.M. Power Density Maximization in Medium Frequency Transformers by Using Their Maximum Flux Density for DC–DC Converters. Electronics 2020, 9, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhang, P.; Li, P.; Liu, Z.; Li, W.; Zhang, J. Research on Magnetic-Thermal-Force Multi-Physical Field Coupling of a High-Frequency Transformer with Different Winding Arrangements. Electronics 2023, 12, 5008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Reyes, J.; Ponce-Silva, M.; Cortés-García, C.; Lozoya-Ponce, R.E.; Parrilla-Rubio, S.M.; García-García, A.R. High-Power-Factor LC Series Resonant Converter Operating Off-Resonance with Inductors Elaborated with a Composed Material of Resin/Iron Powder. Electronics 2022, 11, 3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.S.; Choi, B.G. Calculation Methodologies of Complex Permeability for Various Magnetic Materials. Electronics 2021, 10, 2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Sotelo, D.; Rodriguez-Licea, M.A.; Soriano-Sanchez, A.G.; Espinosa-Calderon, A.; Perez-Pinal, F.J. Advanced Ferromagnetic Materials in Power Electronic Converters: A State of the Art. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 56238–56252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Robles, D.; Figueroa-Barrera, C.; Moreno-Goytia, E.L.; Venegas-Rebollar, V. An Experimental Comparison of the Effects of Nanocrystalline Core Geometry on the Performance and Dispersion Inductance of the MFTs Applied in DC-DC Converters. Electronics 2020, 9, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashgari, H.R.; Chu, D.; Xie, S.; Sun, H.; Ferry, M.; Li, S. Composition Dependence of the Microstructure and Soft Magnetic Properties of Fe-Based Amorphous/Nanocrystalline Alloys: A Review Study. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2014, 391, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, N.M.; Adoo, N.A.; Meakins, E.; Keylin, V.; Feichter, G.E.; Noebe, R.D. The Effect of Stress-Annealing on the Mechanical and Magnetic Properties of Several Fe-Based Metal-Amorphous Nano-Composite Soft Magnetic Alloys. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2023, 600, 122037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Zhang, J.; Demidenko, O.; Sun, H.; Wang, C.; Wang, J. Influence of Stress-Induced Anisotropy on Domain Structure and Magnetic Properties of Fe-Based Nanocrystalline Alloy under Continuous Tension Annealing. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2023, 600, 122035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Li, J.; Zhang, R.; He, A.; Dong, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zheng, J.; Li, X.; Liu, X. Effect of Transverse Magnetic Field Annealing on the Magnetic Properties and Microstructure of FeSiBNbCuP Nanocrystalline Alloys. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2022, 560, 169628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Y.-C. Influence of Magnetic Field Annealing Methods on Soft Magnetic Properties for FeCo-Based Nanocrystalline Alloys. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2015, 51, 2004704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szynowski, J.; Kolano, R.; Kolano-Burian, A.; Polak, M. Reduction of Power Losses in the Tape-Wound FeNiCuNbSiB Nanocrystalline Cores Using Interlaminar Insulation. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2014, 50, 6300704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Han, R.; Li, F.; Pan, X.; Chu, Z. Design and Analysis of Magnetic Shielding Mechanism for Wireless Power Transfer System Based on Composite Materials. Electronics 2022, 11, 2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jiang, C.; Zhao, H.; Wen, B.; Jiang, Y.; Long, T. Novel Flexible Nanocrystalline Flake Ribbons for High-Frequency Transformer Design. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition (APEC), Phoenix, AZ, USA, 14 June 2021; pp. 2891–2896. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, S.; Liu, W.; Liu, C.; Lyu, J. Wireless power transfer for IoT bolts in railways: Overcoming coupling challenges due to conductive and ferromagnetic rails. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2026. Early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Li, X.; Jiang, C.; Li, Z.; Long, T. Permeability-Adjustable Nanocrystalline Flake Ribbon in Customized High-Frequency Magnetic Components. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 3477–3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Jiang, C.Q.; Ma, T.; Zhang, B.; Xiang, J.; Zhou, J. Core Loss Optimization for Compact Coupler via Square Crushed Nanocrystalline Flake Ribbon Core. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 9095–9099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theisen, E.A. Recent Advances and Remaining Challenges in Manufacturing of Amorphous and Nanocrystalline Alloys. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2022, 58, 2001207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enomoto, Y.; Deguchi, K.; Imagawa, T. Development of an Ultimate-High-Efficiency Motor by Utilizing High-Bs Nanocrystalline Alloy. IEEJ J. Ind. Appl. 2020, 9, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, T.; Zeze, S.; Makino, S.; Ohto, M. Research on Motor with Nanocrystalline Soft Magnetic Alloy Stator Cores. J. Eng. 2019, 2019, 4158–4162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, N.; Inoue, M.; Fujisaki, K.; Itabashi, H.; Yano, T. Iron Loss Reduction in Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor by Using Stator Core Made of Nanocrystalline Magnetic Material. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2017, 53, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Li, X.; Ghosh, S.S.; Zhao, H.; Shen, Y.; Long, T. Nanocrystalline Powder Cores for High-Power High-Frequency Power Electronics Applications. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 10821–10830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, A.; Victoria, J.; Torres, J.; Martinez, P.A.; Alcarria, A.; Perez, J.; Garcia-Olcina, R.; Soret, J.; Muetsch, S.; Gerfer, A. Performance Study of Split Ferrite Cores Designed for EMI Suppression on Cables. Electronics 2020, 9, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, Q.; Li, Y. The Effects of Processing Technologies on Magnetic Properties of Nanocrystalline Soft Magnetic Materials. In Proceedings of the 2019 22nd International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems (ICEMS), Harbin, China, 11 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, C.; Jiannong, H.; Xiangdong, Y. Novel Accurate Core Loss Test Method for Powder Core Materials in Power Electronics Conversion. In Proceedings of the 2013 4th IEEE International Symposium on Power Electronics for Distributed Generation Systems (PEDG), Rogers, AR, USA, 8–11 July 2013; IEEE: Rogers, AR, USA; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).