Abstract

Breast cancer (BC) mortality rates remain high in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) due to limited awareness, poverty, and inadequate medical facilities that hinder early detection. Although deep learning models have achieved high accuracy in BC detection (BCD), they require substantial computational resources, making them unsuitable for deployment in remote or rural areas. This study proposes a lightweight convolutional neural network (CNN) using Knowledge Distillation (KD) for BCD, where a large Teacher Model (TM) transfers learned representations to a smaller Student Model (SM), which is better suited for deployment on low-power devices. We compare it with two prominent model compression techniques: pruning and quantization. Experimental results indicate that the TensorFlow Lite (TFLite)-optimized Student Model (SM_TFLite) achieved 97.67% accuracy, representing a 2.33% relative loss to its teacher, a result comparable to other compression techniques. Its mean accuracy is 73.97% with a 95% Confidence Interval of [65.04%, 82.90%] in a cross-dataset experiment. However, SM_TFLite was the most compact (5.21 kB) and fastest (3.3 ms latency), outperforming both pruned (2924.31 kB, 13.68 ms) and quantized models (746–751 kB, 4–5 ms). Evaluation on a Raspberry Pi 4 Model B demonstrated that all models exhibited similar CPU and memory usage, with SM_TFLite causing only a minor increase in device temperature. These results demonstrate that KD combined with TFLite conversion offers the best trade-off between accuracy, compactness, and speed.

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines Breast Cancer (BC) as a life-threatening malignancy characterized by the uncontrolled growth of abnormal cells forming a tumor in the breast, which, if left untreated, can metastasize (spread) to vital organs through the bloodstream and lymphatic system, ultimately becoming fatal [1]. Most cases of BC begin in the ducts that carry milk to the nipple or in the lobules that produce milk. These changes often result from genetic mutations that activate growth-promoting genes or disable tumor-suppressing ones, allowing cells to divide unchecked. While some mutations, such as in the BRCA1, BRCA2, or PALB2 genes, are inherited, most occur spontaneously during a person’s lifetime [2]. BC is not a single disease but a group of disorders originating from different cells within the breast tissue. The cancer cells can spread to lymph nodes and distant organs such as the lungs, liver, brain, or bones, as the tumor progresses from localized (in situ) to invasive and eventually metastatic stages. Therefore, BC can become potentially fatal if not detected and treated early. Table 1 summarizes the significant forms of breast cancer and their diagnosis technique [1,2,3].

Table 1.

Summary of the Different Types of Breast Cancer.

A recent global analysis of 2022 BC data from GLOBOCAN, Cancer Incidence in Five Continents Plus (CI5plus), and the WHO Mortality Database reported 2.3 million new cases and 670,000 deaths, accounting for 25% of all new cancer diagnoses and 15% of cancer-related deaths among women, respectively [4]. The study found that incidence rates were highest in Australia and New Zealand (approximately 100 cases per 100,000 women), followed by Northern America and Northern Europe, and lowest in South-Central Asia, Middle Africa, and Eastern Africa (below 30 cases per 100,000). These regional differences show variations in lifestyle choices, productive habits, and access to healthcare. On the one hand, countries with a high Human Development Index (HDI) report higher counts due to factors such as obesity, alcohol consumption, delayed childbirth, lower fertility rates, and increased case identification through various screening programs. On the other hand, Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) record fewer cases of breast cancer. However, they experience higher death rates due to late diagnosis and limited access to treatment options [4]. The reports also reflect that, by the next 25 years, BC cases are likely to rise by nearly 40% and deaths by almost 70%, with the steepest increases in LMICs. If early detection and treatment do not improve, these growing differences may make it harder to lower breast cancer deaths worldwide.

Researchers are increasingly using Artificial Intelligence (AI) to improve early Breast Cancer Detection (BCD). One U.S. study [5] compared an AI-based BCD system to ten board-certified radiologists. The radiologists reviewed breast ultrasound images with complete clinical information, while the AI system had only the images. Even with this difference, the AI performed better, showing higher diagnostic accuracy (AUROC = 0.962, AUPRC = 0.752), greater sensitivity (94.5%) and specificity (85.6%), a 4.5% reduction in unnecessary biopsies, and a 5.4% increase in positive predictive value (PPV). These findings show that AI can detect BC more accurately and reduce false positives. Similarly, another extensive study in Germany [6] involving over 460,000 women at 12 screening sites also showed that AI-supported double reading led to a 17.6% higher BCD rate than standard screening, with a similar or slightly lower false positive rate. The AI system also increased the PPV of both recalls and biopsies, detecting more true cancers per procedure, and reduced radiologists’ workload by up to 56.7% through efficient triaging of normal mammograms.

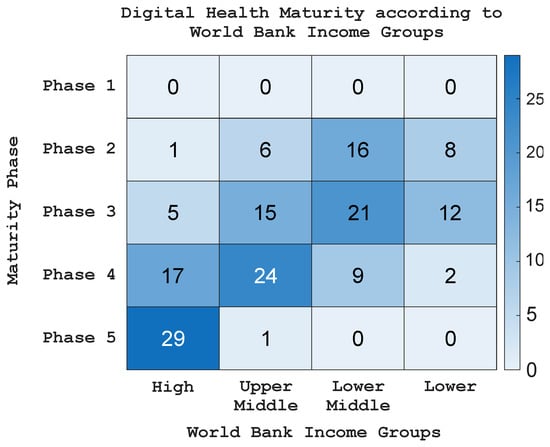

However, the adoption of technology in healthcare remains limited across LMICs. Figure 1 presents a heatmap illustrating the state of digital health maturity according to World Bank income groups in 2023 [7]. The findings demonstrate a strong correlation between digital health maturity and national income levels. High-income countries tend to fall within the most advanced stages (phases 4–5), where digital health systems are already well established. In comparison, many upper- and lower-middle-income nations are still developing, usually positioned around the middle phases (2–4). Most low-income countries are at the early stages (phases 1–2), which shows that digital infrastructure is still limited and that the use of digital technologies, including AI for breast cancer detection, is progressing more slowly. Many LMICs still struggle with poor internet connectivity, limited access to modern imaging tools, and a shortage of trained healthcare workers [8]. Financial barriers make the situation even more difficult, as setting up, maintaining, and upgrading these systems can be costly [9]. Addressing these challenges is key to ensuring that AI-based BCD becomes more accessible and equitable in healthcare settings with limited resources.

Figure 1.

Heatmap of WHO’s Digital Health Maturity Phase according to the World Bank Income Groups in 2023.

Lightweight Machine Learning (ML) for BCD can help increase early detection rates in LMICs. An ML model is lightweight if it possesses low computational requirements, a small model size, a low memory footprint, and high energy efficiency [10]. These features make it suitable for real-time-based classification systems for resource-constrained environments. Deploying such models on low-cost Single-board Computers (SBCs) such as the Raspberry Pi (RPi) can help address the primary challenge of implementing AI in LMICs. These models require minimal computational power and can operate offline, addressing infrastructure limitations such as unreliable internet and limited hardware. Their low cost and energy efficiency reduce financial burdens, while their portability enables deployment in remote or underserved areas. Moreover, lightweight ML systems are easy to maintain. They can assist healthcare workers with limited AI expertise, making them a practical solution for improving access to BCD in resource-constrained settings.

This paper presents a lightweight Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)-based BCD model using the Knowledge Distillation (KD) technique. KD is one of the approaches used to develop lightweight Deep Learning (DL) models by transferring knowledge from a pre-trained deep CNN (the Teacher Model (TM)), to a smaller/shallow model (the Student Model (SM)). This technique allows the SM to learn key features from the TM while maintaining high accuracy and energy efficiency. In our previous work [11], we developed a lightweight CNN for BCD using KD, achieving an 87% reduction in trainable parameters while maintaining high performance (99.3% accuracy, 100% precision, and 99% recall). Building on that, this study further improves the SM with the TensorFlow Lite (TFLite) framework, creating the SM_TFLite model that offers faster inference, smaller file size, and better deployment efficiency than pruning and quantization techniques. These improvements make lightweight AI more practical for BCD in IoT-based healthcare systems. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- Design and implementation of a KD-based lightweight CNN model that achieves high detection accuracy while maintaining a significantly reduced model size, making it suitable for deployment on resource-constrained devices.

- Extensive evaluation across three diverse BC datasets, demonstrating consistently high performance, robustness, and generalization capability.

- Cross-dataset evaluation of the proposed model by training it on one dataset and applying it to another with different feature distributions, showing the proposed model outperforms the SM without KD despite the expected accuracy drop under domain shift.

- Comparative analysis of the proposed KD-based SM with other lightweight conversion techniques, including TFLite conversion, pruning, post-training quantization (PTQ), and quantization-aware training (QAT), extending our previous work in [11].

- Preliminary deployability assessment on a RPi 4 Model B, confirming low memory footprint and low-latency inference, underscoring its potential for real-time telemedicine applications in resource-limited environments.

The remaining parts of this paper are as follows: Section 2 reviews related work on lightweight ML-based BCD systems identified from the Scopus database. Section 3 presents a short background on KD, PTQ, and QAT techniques, as well as the datasets, Primary Breast Cancer vs. Normal Breast Tissue (PBCNT), Breast Cancer Dataset (BCDD), and Breast Cancer Wisconsin (Diagnostic) Dataset (WDBC), which form the foundation of this study. Section 4 describes the proposed model and its design. Section 6 presents the experimental setup and performance evaluation of the model. Section 7 discusses the limitations of the proposed model. Finally, Section 8 concludes the paper and outlines potential directions for future research.

2. Related Works

In this section, we review the existing lightweight BCD-based ML methods. There is no generally accepted definition of lightweight ML. Thus, different authors have put forward different criteria. Li et al. [12] define Lightweight ML as a technique that can run on a standard computer with a single processor core. In contrast, Kim et al. [13] define it as a model that can run on resource-constrained IoT devices without reducing system performance. We will use the latter definition in this paper, where a resource-constrained device is one with limited memory and computational power. Table 2 shows the summary of the performance of the models investigated in the literature review.

Many studies have focused on creating lightweight models to detect BC with the help of transfer learning, architecture adjustments, or multi-stage approaches: Ahmed et al. [14] used DenseNet201 in a mammogram analysis study with fine-tuning, which indicates that pre-trained models can be successfully tailored to medical imaging tasks at only a small amount of computational resources. These approaches highlight the trend toward combining efficient architectures, such as MobileNet, with transfer learning to create practical, low-latency diagnostic tools. Pramanik et al. [15] employed SqueezeNet 1.1 combined with genetic and grey wolf optimizers for feature selection. Whereas Laxmisagar et al. [16,17] used MobileNet for feature extraction followed by a CNN classifier, and further enhanced the pipeline with stain-removal preprocessing. Similarly, Ahmad et al. [14] demonstrated that data augmentation significantly improves the performance of MobileNetV1, ResNet50, and DenseNet201. Abdelli et al. [18] further showed that combining the BreakHis and IDC datasets boosts model performance. Other lightweight variants integrate auxiliary networks or simplified CNNs; for instance, Liu et al. [19] used a U-net for Region of Interest (ROI) localization together with a CNN for prediction, Oliveira et al. [20] combined ResNet50 and VGG16 with contour refinement, and Elbashir et al. [21] designed a compact CNN with only two convolutional and two dense layers.

Table 2.

Performance of Lightweight Methods in the Literature.

Table 2.

Performance of Lightweight Methods in the Literature.

| Ref. | Year | Dataset | Technique | Acc. (%) | Prec. (%) | Recall (%) | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [12] | 2018 | ICPR2012 | Random forest + CNN | 78 | 79 | 0.784 | |

| [21] | 2019 | TCGA | CNN | 98.76 | 100 | 91.42 | 0.955 |

| [20] | 2019 | INbreast | ResNet50 + VGG16 | 85 | |||

| [18] | 2020 | BreakHis, IDC | MobileNet | 94.42 | 94.99 | 94.42 | 0.9449 |

| ResNet50 | 97.03 | 97.41 | 97.03 | 0.9705 | |||

| [19] | 2020 | Camelyon16 | U-net + CNN | ||||

| [16] | 2021 | BACH | MobileNet2.10ex + CNN | 88.92 | |||

| [22] | 2022 | BreakHis | LightXception (Averaging) | 96.89 | 99.1 | 96.35 | 0.977 |

| LightXception (Threshold) | 97.69 | 98.15 | 98.54 | 0.9833 | |||

| LightXception (Whole) | 96.59 | 97.85 | 97.23 | 0.9751 | |||

| Xception (Averaging) | 99 | 99.86 | 98.69 | 0.9926 | |||

| Xception (Threshold) | 99.05 | 99.86 | 98.76 | 0.993 | |||

| Xception (Whole) | 99.7 | 99.78 | 99.78 | 0.9978 | |||

| [17] | 2022 | BACH | MobileNet1.40 + CNN | 87.5 | |||

| MobileNet1.40ex + CNN | 72.91 | ||||||

| MobileNet2.00 + CNN | 75 | ||||||

| [15] | 2023 | DMR-IR | SqueezeNet 1.1 + GA + GWO + k-nn | 100 | 100 | 100 | 1 |

| [23] | 2023 | IDC | MobileNetV2 + CNN | 92.3 | 84.09 | 88 | 0.86 |

| BreakHis | MobileNetV2 + CNN | 98.56 | 96.42 | 98.18 | 0.9729 | ||

| BACH | MobileNetV2 + CNN | 92 | 92.16 | 91.94 | 0.9215 | ||

| [24] | 2023 | BreakHis | MobileViT | 95.3 | 98.8 | 99.8 | 0.969 |

| [25] | 2023 | BreakHis | Separable CNN | 97.23 | 98.11 | 97.71 | 0.9798 |

| [26] | 2023 | ICIAR | Deep CNN + Separable Conv | 96.25 | 99.8 | 99.4 | 0.995 |

| BreakHis | Deep CNN + Separable Conv | 99.4 | |||||

| Brac | Deep CNN + Separable Conv | 72.2 | 75.8 | 74.4 | 0.755 | ||

| [27] | 2024 | BreakHis | PCSAM + ResCBAM | 98.74 | 99 | 99 | 0.99 |

| INCIAR2018 | PCSAM + ResCBAM | 97.5 | 97.5 | 97.62 | 0.975 | ||

| [28] | 2024 | Not Available | MD-VACNet | 98.47 | 98.31 | 98.42 | |

| [29] | 2024 | Proprietary | CNN | 85 | 81.98 | 97.88 | 0.8923 |

| [30] | 2020 | PUSH Ultrasound | CNN + KD | 96.33 | 89.25 | ||

| [12] | 2018 | ICPR 2012 | Random forest + CNN | 78 | 79 | ||

| [31] | 2023 | Self-supervised KD | 85 | ||||

| [32] | 2023 | BreakHis | Resnet-50 + Quantization aware | 94.26 | |||

| VGG19 + Quantization aware | 94.81 | ||||||

| [33] | 2024 | KD | 90.63 | 99.68 | 98.74 | 99.21 |

In addition to architectural optimization, researchers have also achieved complexity reduction through KD, separable convolutions, or hybrid learning strategies. Zhang et al. [30] proposed a lightweight CNN to classify ultrasound-based lesions. They applied KD to train their model as the SM using YOLOv3 as the TM. They also employ an asynchronous calculation strategy that processes only a quarter of the network per image frame, reducing the model’s computational power requirements. Wang et al. [34] employed KD with EfficientNet to train a lightweight student model for histopathology image classification, significantly lowering memory requirements while maintaining strong accuracy. Li et al. [12] proposed a multi-stage framework using random forests and CNNs, and Ashraf et al. [35] combined a shallow ResNet50 with an Inception module via self-supervised contrastive learning. Scientists have also investigated ensemble and federated learning approaches, such as MobileNetV2 with a shallow CNN in Garg et al. [23] and federated learning with MobileViT in Yan et al. [24]. Additional lightweight designs include CNNs with separable and bottleneck convolutions [25,26], SqueezeNet-based transfer learning [36], patch-level feature fusion networks [27], and mobile-integrated DL systems for cytology images [29].

The literature shows that pruning and quantization reduce redundancy in CNN models, making them lighter and deployable on edge devices with limited capacity [37]. Kim et al. [22] introduced LightXception. The technique prunes the original Xception model, removing 65% of its layers and convolutional filters while maintaining an accuracy of up to 97.69%. Kumar et al. [38] applied Post-Training Quantization (PTQ) to MobileNetV2 for histopathological image classification to form MobiHisNet. They achieved an 84.09% reduction in model size (from 12.82 MB to 2.04 MB) while increasing accuracy by up to 3 percentage points. However, when they compressed the model further, reducing it by 91.73% of its original size, the accuracy fell by up to 22 percentage points. Another study [32] successfully deployed VGG19- and ResNet-50-based models optimized using joint sparsity Quantization-Aware Training (QAT) on embedded systems.

Yan et al. [27] integrated attention mechanisms into lightweight models to improve feature selection without substantially increasing computational costs. Similarly, Nissar et al. [39] improved the MobileNetV3 framework by incorporating channel attention to enhance feature representation. Their technique achieved a 99% accuracy, precision, and recall. However, adding the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) would increase the model size and complexity. Another study proposed a Multi-Disease Visual Attention Condenser Network (MD-VACNet) with Self-attention and spatial pyramid pooling [28] for edge computing devices. The self-attention is a mechanism that allows a model to weigh the importance of different spatial or temporal features relative to one another. Hence, it allows MD-VACNet to localize cancer features and improve the model performance. The authors reported a 98.99% accuracy with 25% fewer parameters than MobileNet-V1.

Despite the aforementioned advances in lightweight BCDs, several challenges remain: Some models [18,20,22,40] claim to be lightweight, yet their parameter counts remain too large for efficient deployment on low-resource devices such as the RPi and mobile phones. Others [16,17,19,29,41] reduced model size at the cost of diagnostic accuracy. Also, many studies rely on a single dataset or lack evidence of real-world deployability. Furthermore, while pruning and quantization have been widely studied in other domains, to the best of our knowledge, there are no systematic comparative analyses with KD in the context of BCD. This paper addresses these gaps by developing a KD-based lightweight CNN for BCD and comparing it against pruning- and quantization-based models within a unified evaluation framework. It tested the models across multiple benchmark datasets. It also evaluated their inference latency, memory footprint, and power consumption on a RPi 4 Model B, assessing the model’s deployability on resource-constrained devices.

3. Background

This section presents the foundations of this paper. It introduces the concept of KD. It discusses the basics of pruning and quantization. It also presents three key text-based datasets used in our research: the PBCNT, BCDD, and WDBC. These datasets help us investigate the effectiveness of KD techniques in improving BCD.

3.1. Knowledge Distillation

KD is an ML compression technique that transfers knowledge from a large model to a smaller one [42]. The large model is known as the Teacher model (TM), while the small one is called the Student Model (SM). In other words, KD distills the TM’s knowledge and stores it in the SM. Conventional ML technique tries to fit a neural network to the training data, while KD aims to train an SM to replicate the predictions of a TM [43]. Thus, it finds application where large models cannot be deployed due to resource constraints, necessitating compression by transferring their knowledge to a smaller model [43,44].

KD offers several benefits. It increases system speed and efficiency by reducing model size and complexity. Thereby, allowing deployment on resource-constrained devices, such as mobile phones, SBCs, and drones [45]. It can also transfer knowledge without using the complete dataset, improving data security and privacy [42]. This method has been successfully applied across various fields, including natural language processing, speech recognition, and image recognition [43]. Additionally, KD finds application in scenarios where rapid inference is crucial, such as real-time applications in autonomous vehicles or real-time video analysis, where the speed and efficiency of the model are critical [45].

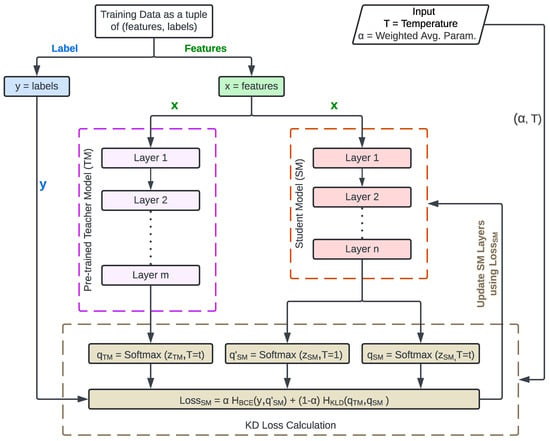

Pytorch and Keras have KD libraries [45,46]. This paper uses the Keras implementation [46]. The technique minimizes a loss function that incorporates both the teacher’s softened logits and the ground-truth labels during training. Figure 2 is the flowchart for teaching the SM using KD. Intel® Labs inspired it [44]. The process starts with inputting the dataset features (X) into a pre-trained TM and the SM. The TM and the SM produce the and the logits, respectively. KD also collects the softmax Temperature (T) and weighted average parameter () from the developer. It uses the softmax function (see Equation (1) proposed by Hinton et al. [47] to create TM soft labels, SM soft predictions, and SM hard predictions as , , and , respectively.

Figure 2.

SM Learning Process using KD.

Hinton et al. [47] introduced the parameter T into the softmax function to obtain information beyond the dataset’s ground-truth labels (y). As T grows, the softmax function’s probability distribution becomes softer, providing more information about the teacher’s prediction. The authors tested T values ranging from 1 to 20. They found that lower values work better when the SMs are lighter than the TMs, because higher temperatures may provide too much information for the student to capture effectively. However, Intel® Labs argues that there are no methods for predicting the capacity of information the SM acquires.

Our proposed model uses Keras’s Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence loss function () to minimize the squared difference between the soft logits of the TM and SM (i.e., and , respectively). It also uses the Binary Cross Entropy loss function () to calculate the Loss between the SM’s hard prediction () and the ground-truth (y). In the last step, the system uses a weighted average on and losses with as the weighing parameter to calculate the SM’s Loss (). Hinton et al. [47] typically used a small in their weighted average. Smaller values enable the student model to place greater emphasis on the teacher’s softened predictions, thereby improving generalization.

In this paper, we used and for the KD hyperparameters. Section 6.1 justifies the selection of the aforementioned values through an ablation study, which evaluates the influence of different and T combinations on model performance.

3.2. Prunning

Pruning is a process that removes unnecessary parts of an ML model, simplifying and reducing its size. This paper adopts the definition of Vadera et al. [48], which defines pruning as the process of reducing the size and complexity of a trained neural network by removing redundant or less important parameters, such as weights, neurons, filters, or channels, while maintaining model accuracy. It is used in Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) to reduce size and latency, in Decision Trees to prevent overfitting, in Random Forest to simplify ensembles, and in Rule-Based models to improve interpretability.

There are several forms of pruning in neural networks, such as structured pruning, which removes entire filters or channels, and unstructured (magnitude-based) pruning, which removes individual weights. In this paper, we adopt magnitude-based pruning because it is practical, widely used, and easily transferable across models [48]. We applied the low-magnitude pruning technique from the TensorFlow model optimization framework [49], which automatically increases the sparsity of the model’s layers during training by setting low-importance weights to zero. Alternatively, users can specify the desired sparsity level. For example, assigning a target sparsity of 50% forces half of a layer’s weights to become zero, reducing model complexity while preserving the network structure. This pruning mechanism is versatile, as it can be applied to individual layers, groups of layers, or entire models. However, it raises an error when it encounters unsupported or unrecognized layer types.

3.3. Quantization

Quantization is the conversion of high-precision values in weights or activations into lower-precision ones. It converts real numbers (float or double data types) to integer values (INT8 or INT4 data types) [50]. DDNs are tolerant to precision reduction due to their over-parameterized structure, which allows them to maintain accuracy even when many parameters are quantized [50]. The quantization function in Equation (2) expresses the transformation process:

where r is a real-valued parameter or activation, S is a scaling factor, and Z is a zero-point used for mapping real numbers to integers.

Quantization offers several advantages for efficient deployment of DNN on resource-constrained devices [50,51,52]: It reduces model size by replacing 32-bit floating-point values with 8-bit integers, achieving up to a 4× smaller memory footprint and enabling deployment on embedded or edge hardware. It accelerates inference by up to 4× due to faster integer computations and lower memory bandwidth requirements. Quantization also improves energy efficiency, delivering up to 16× better performance per watt, extending battery life for edge devices and reducing operational costs in cloud environments. Modern AI accelerators such as Google Edge TPU and NVIDIA Tensor Cores are optimized for integer arithmetic, allowing quantized models to utilize available hardware resources while maintaining near-original accuracy fully.

Several quantization approaches exist, each with different implementation complexity, accuracy trade-offs, and deployment constraints. In this work, we adopt PTQ and QAT. PTQ provides fast, low-cost model compression suitable for real-time or embedded systems, whereas QAT is essential when maintaining diagnostic reliability is critical and minor accuracy losses are unacceptable [50]. The following subsections introduce the specific PTQ and QAT techniques we used.

3.3.1. Weight-Based and Full Integer PTQ

PTQ can be weight-only, dynamic-range, or full-integer quantization [53]. Weight-only quantization converts only the weights to integers (INT8), while the remaining parameters, such as activations, inputs, and outputs, remain in real numbers (FLOAT32). The integer computations of the weights reduce latency. However, the technique needs quantization and dequantization steps for integer-based data to work correctly with floating-point data.

The dynamic range quantization technique is similar to its weight-only counterpart. It converts weights to integers while leaving other tensors in their real number format. However, it dynamically quantizes activations to integers at runtime, enabling computations between weights and activations to be performed in integer format. This technique does not fully compress the model, since it stores activations in floating-point format (i.e., real numbers). Furthermore, this technique requires an additional dequantization operation since the input and output tensors also remain in floating-point format.

Full-integer PTQ converts all floating-point tensors, including inputs and outputs, into integers. This technique leads to the highest reductions in model size and improvements in inference speed [53]. The technique is useful for devices that support only integer values, such as 8-bit microcontrollers and the Coral Edge TPU. However, the range of values for variable tensors must be determined by running computations with a representative dataset for calibration.

In this paper, we adopt weight-only and full-integer PTQ to evaluate the two extremes of this technique. The TFLite Converter was used to implement these approaches [54]. We compare PTQ results with our KD model in Section 6.5.

3.3.2. Quantization-Aware Training (QAT)

QAT quantizes the model during training by simulating low-precision (integer) arithmetic. It introduces fake quantization operations on the weights and activations and uses the results to optimize the quantization parameters [55]. In other words, QAT quantizes the model during training to enable it to optimize its parameters under the given low-precision constraints. This process allows QAT to maintain the model’s accuracy and integrity despite reduced precision. However, it has a higher computational overhead than PTQ.

We implemented QAT and compared its performance with the proposed KD model in Section 6.6. It was implemented using custom quantizers and layer-level annotations from the TensorFlow model optimization framework [56]. This technique produces a lighter model than other QAT methods by using special wrappers. The wrappers are used during training to introduce the fake quantization operations we mentioned earlier, allowing the DNN to adapt to 8-bit quantization constraints. After the training, the final model was further optimized by converting it to TFLite format.

3.4. Datasets

This paper used the PBCNT, BCDD, and WDBC datasets to test the performance of the proposed model. Using multiple datasets enabled us to assess the model’s generalization and robustness. This section describes the datasets used in this paper to test the model.

3.4.1. Primary Breast Cancer vs. Normal Breast Tissue Dataset (PBCNT)

The PBCNT dataset was generated using microarray-based profiling to compare primary breast cancer tissues with normal breast tissue based on tumor signature miRNA profiles [57,58]. The dataset contains 133 rows and 1928 columns. The first 1926 columns represent normalized microRNA (miRNA) expression features, while the last two columns, named target and target actual, encode the class labels: target contains a binary value (1 = primary breast cancer, 0 = normal breast tissue), and target actual contains the textual class names (primary breast cancer, or normal breast tissue). The sample distribution is skewed, with 122 (91.7%) as normal breast tissue samples and 11 (8.3%) as primary BC samples. Some features correspond to negative control probes (e.g., hsa_negative_control_6-8) for internal calibration and experimental validation.

This dataset can be used for supervised learning and binary classification, enabling researchers to train and test models for cancer detection and biomarker identification. It is high-dimensional and class-imbalanced, making it suitable for evaluating feature selection, dimensionality reduction, and lightweight DNN schemes based on KD, pruning, and quantization-aware training. Biologically, it captures the main patterns of miRNA dysregulation, a crucial factor in tumor initiation and metastasis. It also provides a reproducible benchmark for computational and biomedical studies of miRNA-based BCD and AI research. The dataset is freely and publicly available under the CC0 Public Domain license on Kaggle: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/rhostam/primary-breast-cancer-vs-normal-breast-tissue (Kaggle PBCNT Dataset) (accessed on 2 November 2025) [58].

3.4.2. Wisconsin Breast Cancer Database (BCDD)

The BCDD dataset was collected at the University of Wisconsin Hospitals in Madison and assembled by Dr. William H. Wolberg [59]. The abbreviation used in this paper is BCDD in order to distinguish its acronym from the term BCD (Breast Cancer Detection) and the dataset WDBC (Breast Cancer Wisconsin (Diagnostic) Dataset). It is a reputable dataset in the study and diagnostic modeling of breast cancer. All its records are cytological observations from Fine-Needle Aspirates (FNAs) of breast masses. FNA is a diagnostic procedure that uses a fine needle to collect cellular material from suspicious breast lesions. The data contains 699 instances (samples), each represented by a sample ID, and ten numerical features that define cell characteristics of the breast tissue. These are clump thickness, cell size and shape uniformity, marginal adhesion, single-cell size of the epithelial cell, bare nuclei, bland chromatin, normal nucleoli, and mitoses, each rated out of 10.

The attributes represent morphological changes of cell nuclei between benign and malignant tumors. The last column of the dataset is the class label, which can take two values: benign or malignant. The distribution of the classes is relatively unbalanced, having 458 benign samples (65.5%) and 241 malignant samples (34.5%) [60]. There are only 16 cases of missing attribute values, denoted by a question mark. It has a clean, well-documented structure, ensuring the dataset can be used for statistical analysis, classification, and feature selection in biomedical ML experiments. The data is publicly available on Kaggle under the CC0 Public Domain license: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/uciml/breast-cancer-wisconsin-data (Kaggle BCDD Dataset) (accessed on 2 November 2025) [60], which grants open-access and reproducibility to scholars.

3.4.3. Breast Cancer Wisconsin (Diagnostic) Dataset (WDBC)

The WDBC dataset, like BCDD, is also based on FNA images of breast masses [61], providing a numeric description of these extracted cells. However, BCDD describes cellular cytology (what cells appear to look like under the microscope), whereas WDBC measures cellular morphology (how cells’ shapes and textures are quantified algorithmically) in relation to benign and malignant tumors. The instances represent samples of morphological and textural measurements of the cell nuclei. It consists of 569 cases—357 benign (62.74%) and 212 malignant (37.26%)—with no missing data.

The dataset contains 10 fundamental features calculated from the nuclei in the FNA images: radius, texture, perimeter, area, smoothness, compactness, concavity, concave points, symmetry, and fractal dimension. All these base attributes are further represented by their averages, standard errors, and worst (maximum) values. Hence, 30 numerical features are generated per sample. The dataset is a benchmark that combines size-, shape-, and texture-related information, making it suitable for building advanced ML models to support early BCD. It provides insights into feature extraction, dimensionality reduction, classification, and the detection of possible morphological biomarkers associated with malignancy. It is accessible on the Kaggle site under the CC0 license: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/uciml/breast-cancer-wisconsin-data (Kaggle WDBC Dataset) (accessed on 2 November 2025) [62].

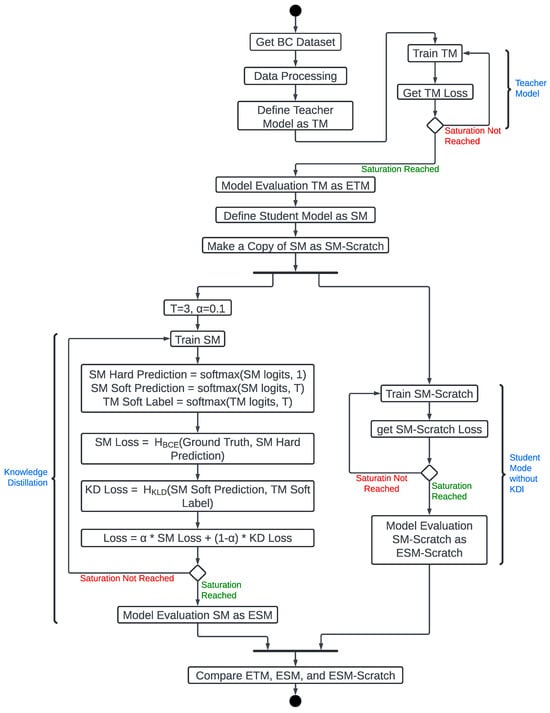

4. Proposed System

This section presents our proposed model, describing the models we developed, trained, and tested. Figure 3 explains the processes. It starts with obtaining and preprocessing the dataset (i.e., PBCNT, BCDD, or WDBC). The preprocessing stage allows us to inspect for missing values and non-informative columns (e.g., id) and remove them. Then the features are separated from the class columns, because they require different preprocessing techniques. The class is then mapped to binary values (B = 0, M = 1, where B and M represent Benign and Malignant, respectively) and converted to one-hot encoding for training. It is vital to convert the categorical data to one-hot coding to enable the model to learn more accurately. The features were normalized to ensure consistent feature scaling across the training and test splits and to support an accurate Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for dimensionality reduction. Then PCA was applied to remove features that did not add information to the data. Finally, the processed feature matrix was reshaped into a format suitable for the input layer of TM and SM.

Figure 3.

Experiment Carried Out.

We used the preprocessed dataset to train the TM. We also developed a lighter model with fewer parameters than the TM that can run on embedded or IoT devices. This light model is called the SM. SM was duplicated to create SM_Scratch. Then, we used the TM to teach SM about the dataset using the KD technique. However, SM_Scratch was trained from scratch without using the KD technique, serving as a control for our experiment to assess how well SM performed.

The details of this model can be found in Table 3. It shows the model summary of TM and SM on the WDBC dataset without any dimensionality reduction. To construct an effective TM, we used the hyperband grid search technique. It identifies the optimal hyperparameters, including the number of hidden layers, filter sizes, dropout units, and learning rate.

Table 3.

Teacher and student model summary.

The resulting TM consists of an input layer, three hidden layers, and an output layer. The hidden layers are two Conv1D (1D convolutional) layers and a dense layer. Conv1D layers perform convolutional operations in which the kernel iterates over the feature vector and computes dot products with adjacent feature values to generate informative feature maps. To stabilize learning and enhance accuracy, batch normalization is applied after each convolution. Both Conv1D layers use ReLU activation with a kernel size of 2. The first convolutional layer has 64 filters and transforms the 30-by-1 input into a 29-by-64 tensor. The second convolutional layer uses 448 filters to process these representations into a 28-by-448 tensor further.

Dropout layers follow the convolution blocks. They randomly deactivate 10% of neurons during training, reducing overfitting and improving generalization. The model then flattens the final 28-by-448 feature map into a single vector of 12,544 elements and feeds it into two dense layers with ReLU and sigmoid activations. Therefore, the total number of parameters in the TM is 863,042, of which 862,018 are trainable, and 1024 are non-trainable.

The SM is a shallow CNN model with significantly fewer parameters than the TM. As shown in Table 3, it contains two lightweight Conv1D layers, each followed by batch normalization and dropout, and a final dense classification layer. Using the same kernel size of 2, the first Conv1D layer transforms the input into a 29-by-4 tensor, and the second expands it to 28-by-8, capturing only the essential patterns needed for classification. The output is then flattened into a 224-dimensional vector and passed to a single sigmoid-activated dense layer. Unlike the TM, the SM contains no intermediate dense layers, reflecting its intentionally shallow architecture. The SM has 582 total parameters, of which 558 are trainable, and 24 are non-trainable, corresponding to a 99.93% reduction relative to the TM while preserving strong predictive performance when trained with knowledge distillation.

To provide a clear, step-by-step representation of the proposed approach, Algorithm 1 outlines the complete workflow of our KD framework for lightweight BCD. This pseudocode complements the flowchart in Figure 3 by formalizing the operations involved in preprocessing, training the Teacher Model (TM) and Student Model (SM), and applying knowledge distillation.

| Algorithm 1 Knowledge Distillation for Lightweight CNN in Breast Cancer Detection |

|

5. Materials and Methods

This section describes the experiments used to obtain the results in Section 6. All the experiments were carried out using the procedures in this section; the slight variations are discussed in the respective subsections of Section 6.

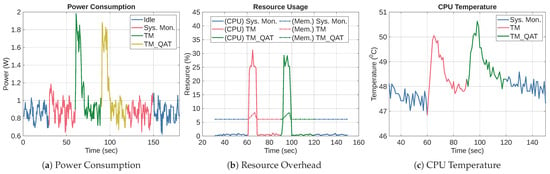

The initial experiment investigates the diagnostic performance of the proposed system, which was assessed using three primary evaluation metrics: accuracy, precision, and recall, computed according to Equations (3)–(5). They measure the system’s capability to correctly identify malignant and benign breast tissue samples, assess the reliability of its positive predictions, and determine its sensitivity in detecting cancerous cases. The deployability test measures the file size, inference time, percentage CPU and memory usage, CPU temperature, and power consumption on an SBC. Raspbbery Pi 4 Model B was the SBC used in the experiments. Additionally, the section compares the proposed model with the PTQ and QAT techniques in terms of accuracy, file size, number of parameters, inference time, CPU and memory usage percentages, CPU temperature, and power consumption. The codes for these experiments are publicly available on GitHub [63].

where

- = number of malignant cases correctly classified as malignant,

- = number of benign cases misclassified as malignant,

- = number of benign cases correctly classified as benign,

- = number of malignant cases misclassified as benign.

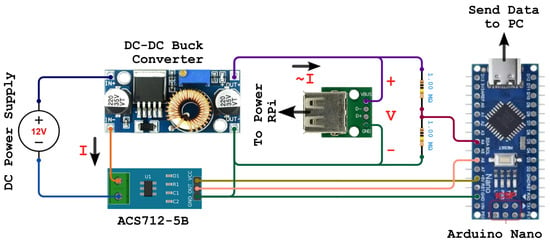

The deployability performance was evaluated by analyzing inference latency, power, CPU, and memory usage on a RPi Model 4 B. Figure 4 shows the experimental setup for measuring power consumption on the RPi. It features a RPi Model 4B as the embedded computing system. It represents IoT devices that could host the proposed model. We connected to the RPi from a second computer via SSH over Wi-Fi. A DC-DC buck converter powers the RPi. We connected the buck converter, the ACS712-5B current sensor input, and a 12 V DC power supply in series to measure the load’s current consumption (i.e., the RPi). This connection allows the current sensor to measure the current (I) drawn by the RPi from the power supply during the experiment and send it to an Arduino Nano for analysis. The Arduino Nano also measures the voltage drop (V) across the RPi. The Arduino sends the measurement through USB to a laptop for collation. We used Equation (6) to measure the power (P) consumption of the RPi. The power consumption measurements were averaged across five experiments to reduce noise.

Figure 4.

Deployability Experimental Setup.

For the latency measurement, we run the code in Algorithm 2. It loads the data and the model. Then it typecasts the data and tests a single data instance against the model. We used Python’s Time v0.0.17 package to record the time immediately before and after loading the model (), loading the input and output tensors (), data type casting (), and inference () and subtracting the before and after time as shown in Equations (7), (8), (9), and (10), respectively. We noticed low latency variation, so no average was taken. Rather, the value of the fifth iteration was recorded. Additionally, all model evaluations on the RPi 4 Model B were performed in CPU-only mode under the default RPi OS (Raspbian 11) installation. The Python scripts were executed directly without any custom compilation or backend reconfiguration. The TFLite v2.18.0 automatically employed the XNNPACK CPU delegate, which internally utilizes the ARM NEON instruction set for optimized matrix operations. No GPU, OpenCL, NNAPI, or TensorRT delegates were enabled, ensuring that all inference was executed solely on the CPU.

| Algorithm 2 Inference Evaluation Experiment |

|

Regarding the CPU and memory usage, a Python-based monitoring script was developed to record the Raspberry Pi’s performance metrics, including CPU utilization, memory usage, and CPU temperature. The script periodically sampled the device’s hardware statistics and stored them in a structured format at one-second intervals. It runs on an indefinitely loop until manually stopped. The monitoring script was executed in a manner that redirected its output to a log file, allowing the performance measurements to be continuously recorded. This experiment was also averaged over five iterations to reduce noise from background processes.

6. Results and Discussion

This section presents and discusses the performance of the proposed model. It investigates its diagnostic and deployability performances. It is organized into five subsections for clarity and completeness. Section 6.1 presents an ablation study on the KD hyperparameters to investigate their influence on model performance. Section 6.2 examines the efficacy of KD as an extension of our previous work [11], evaluating performance across folds in a 10-fold cross-validation. It also benchmarks the SM against related studies, assesses its deployability on the RPi, and evaluates its cross-dataset performance under domain shift. Section 6.3 investigates the benefits of optimizing the model using the TFLite framework in terms of accuracy, file size, architectural compactness, and deployability on embedded devices such as the RPi 4 Model B. Section 6.4, Section 6.5 and Section 6.6 analyze the performance of the pruning technique, PTQ, and QAT, respectively, focusing on their impact on accuracy, compression, and deployability on embedded systems, and comparing their results with the TFLite version of SM.

6.1. Ablation Study on Distillation Hyperparameters

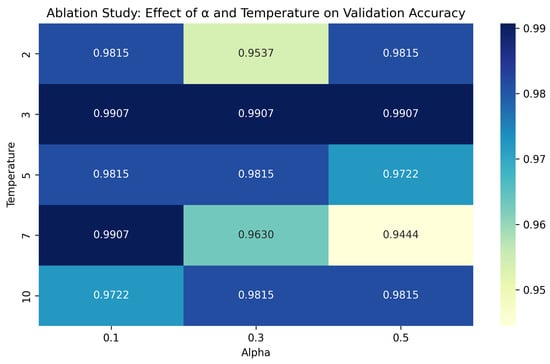

This section presents an ablation study to investigate optimal values for the KD hyperparameters: the distillation coefficient () and the temperature (T). The coefficient controls the trade-off between the hard label loss () and the soft label loss (), while T determines the smoothness of the teacher’s output probabilities [47]. Thus, it is necessary to determine the optimal combination of the two hyperparameter values. The experiment uses and . We selected lower values for T because researchers posited that lower T values tend to produce sharper probability distributions, which can benefit smaller student models [47]. The results of the experiments are visualized as a heatmap in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Heatmap of validation accuracy (%) for different and T values in the distillation process.

The heatmap in Figure 5 shows the validation accuracy of proposed models for different values of and T. It shows that the highest validation accuracy is 99.07% and it was achieved when across all values of (i.e., , , or ). These results show that consistently delivers top performance for all values and that it is the optimal value that strikes a balance between preserving informative soft targets and avoiding overly smooth probability distributions. Regarding the values, we can see that the highest validation accuracy was recorded at and . Additionally, the column shows that it consistently outperforms other combinations, except for only one case (). Hence, lower values (e.g., 0.1) produced more stable performance. This result indicates that placing too much emphasis on the hard label loss can diminish the benefits of distillation when the teacher’s outputs are overly smoothed. Therefore, we selected and for all KD experiments in this research.

6.2. Performance Evaluation of KD

This section evaluates the proposed model (SM) by comparing it with the TM and SM_Scratch. It also compares the proposed SM with existing literature, using three key performance metrics: accuracy, precision, and recall. The experiments evaluated the models across three benchmark datasets: WDBC, PBCNT, and BCDD. Evaluating performance across multiple datasets provides a broader assessment of the model’s robustness and verifies its predictive consistency across different data distributions. Finally, this section presents a cross-dataset analysis in which the models are trained on WDBC and tested on BCDD to examine their behavior under distributional shift.

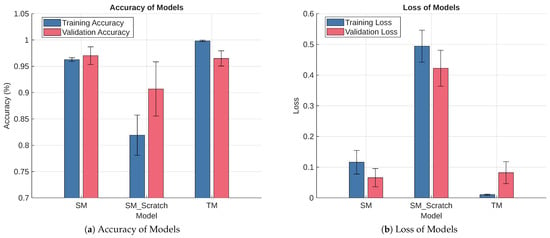

6.2.1. Diagnostic Performance of KD

This section uses 10-fold cross-validation on the WDBC dataset to provide an excellent balance between bias and variance in the models’ performance estimate. Figure 6 presents the results of the experiments over 30 epochs. It shows the training and validation accuracy and loss for the TM, SM_Scratch, and SM. The comparison highlights the performance differences among the three models during both training and validation phases. The error bars represent 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) for the mean values across the ten folds, reflecting the stability and consistency of each model. This visualization provides an overview of how effectively KD improves the student model’s learning behavior compared to the teacher and the standalone student network.

Figure 6.

Diagnostic Performance of TM, SM_Scratch, and SM in a 10-Fold Cross-Validation Setting.

Figure 6a shows the training and validation accuracies of the 10-fold cross-validation experiment. The results indicate that TM achieved the highest training and validation accuracies of 99.82% ± 0.14% and 96.49% ± 1.45%, respectively. Notice that the CIs are small, indicating strong convergence and generalization. This outcome is intuitive because TM has a larger network capacity than SM_Scratch and SM, allowing it to capture complex, subtle, and high-dimensional patterns. SM has the second-best performance. It reaches 96.27% ± 0.34% and 97.02% ± 1.68% for training and validation accuracy, respectively. The CIs are also small, indicating that the SM converges and generalizes well.

Additionally, the training and validation accuracy CIs of SM overlap the validation accuracy CI of TM, indicating that their performance is statistically comparable at the 95% confidence level. However, SM_Scratch performed significantly worse, with a training accuracy of 81.92% ± 3.82% and validation accuracy of 90.69% ± 5.16%. The wide CIs for both accuracies in SM_Scratch reflect high fold-to-fold variability, slower learning, and weaker generalization. The partial overlap of its validation accuracy CI with those of TM and SM (and its training accuracy) suggests that the observed differences in mean accuracy may not be statistically significant, given the limited sample size. Comparing SM and SM_Scratch shows that SM effectively learned from the TM.

Figure 6b shows the loss results of the models. The loss evaluation mirrors the accuracy trends. TM recorded the lowest training loss of 0.010 ± 0.002 and the validation loss of 0.082 ± 0.036, confirming its well-fitted learning behavior. SM achieved a slightly higher training loss of 0.116 ± 0.039 but a lower validation loss of 0.066 ± 0.030, suggesting better generalization to unseen data. Similar to the accuracy results, the training and validation CIs of SM overlap, and both overlap the validation loss CI of TM, reinforcing the conclusion that the performance of TM and SM is statistically comparable at the 95% confidence level. SM_Scratch again showed the weakest performance, with high losses of 0.494 ± 0.052 for training and 0.422 ± 0.059 for validation, consistent with underfitting. Its CIs are well above those of TM and SM, supporting the interpretation that its apparent overlap in accuracy is likely due to limited sample size rather than comparable performance. In general, these results demonstrate that KD stabilizes training, improves generalization, and enables the student model to achieve teacher-level accuracy with substantially reduced complexity.

6.2.2. Benchmarking Against Related Work

In this section, the SM was trained without cross-validation, using 85% of each preprocessed dataset for training and the remaining 15% for validation, with 30 training epochs. KMeans-SMOTE was applied to ensure class balance while preventing data leakage. Although six experiments were initially conducted (with and without oversampling for each dataset), we report results only for configurations that yielded unique outcomes. Specifically, oversampling did not affect the WDBC and PBCNT datasets. The oversampled and baseline models achieved identical performance. So we report only the baseline results for these datasets. For the BCDD dataset, oversampling eliminated a single false negative observed in the baseline model; therefore, both SM-BCDD and SM-BCDD-O are included. Table 4 summarizes the experiment nomenclature.

Table 4.

Nomenclature for the Experiments Reported.

Table 5 summarizes the performance of the proposed KD-based student models alongside recent related work using the same numerical breast cancer datasets. Oversampling did not produce a measurable change in the WDBC and PBCNT datasets, indicating that they are either naturally balanced or sufficiently separable. For the BCDD dataset, oversampling removed the single false negative observed in the baseline configuration, resulting in a modest improvement in recall. Across all experiments, the student model achieved very low false-positive and false-negative counts (≤1), demonstrating high diagnostic reliability and sensitivity.

Table 5.

Performance comparison with related works.

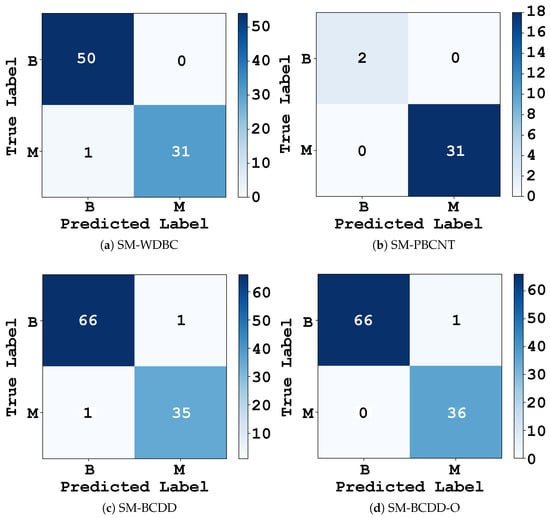

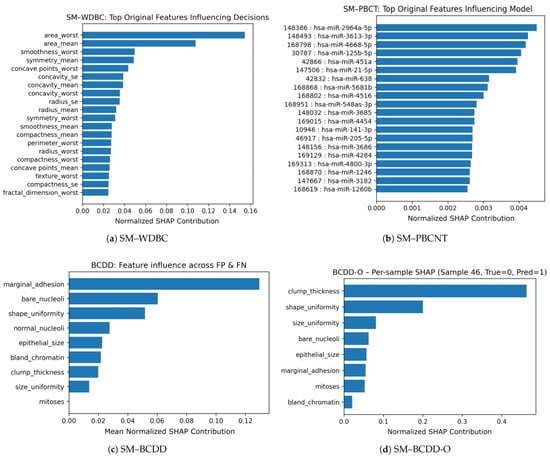

Qualitative Error Analysis and Feature-Level Explainability

This section provides a qualitative analysis of the FPs and FNs observed across the four SM configurations in Table 4. Confusion matrices are first used to characterize each model’s classification behavior and to identify any misclassified samples. To better understand the factors contributing to these errors and to assess whether the SM relied on clinically meaningful patterns, we complemented this analysis with feature-level attribution using Shapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP). Figure 7 presents the confusion matrices for the four models, while Figure 8 shows the normalized SHAP contributions of the features that most strongly influenced the misclassifications.

Figure 7.

Confusion Matrices for SM Across the Four Evaluated Datasets.

Figure 8.

Feature-level SHAP Importance for the Four Reported Experiments.

Figure 7a presents the confusion matrix for SM–WDBC. It shows one FN, where a malignant case was misclassified as benign, and no FPs. To investigate which features contributed to this misclassification, Figure 8a displays the SHAP values computed for the misclassified sample. The plot indicates that area_worst and area_mean were the most influential features in misleading the model, with additional contributions from smoothness_worst and symmetry_mean. These features collectively reduced the predicted malignancy probability and pushed the model’s decision toward the benign class. Thus, the FN corresponds to a borderline case with only mildly abnormal morphology, an ambiguity that is challenging even for experienced cytopathologists.

Unlike the other configurations analyzed in this section, SM–PBCNT produced no misclassifications, as shown in Figure 7b. Because this is the only case without FPs or FNs, we examined borderline correct predictions by computing SHAP values for the samples with the lowest predicted probabilities. Figure 8b presents the resulting SHAP values for these least-confident correctly classified instances. The feature-level analysis revealed that hsa-miR-2964a-5p, hsa-miR-3613-3p, hsa-miR-4668-5p, hsa-miR-125b-5p, hsa-miR-451a, and hsa-miR-21-5p were the most influential contributors, helping the model correctly classify these borderline cases. These miRNAs also aligned strongly with the principal components identified through PCA, indicating that SM–PBCNT captured biologically meaningful expression patterns rather than overfitting.

Figure 7c shows that the SM–BCDD model produced one FP and one FN, resulting in two separate SHAP explanations. For the FP case, the misclassification was driven primarily by high values of marginal_adhesion and bare_nucleoli. For the FN case, the misclassification was influenced mainly by high marginal_adhesion and shape_uniformity, causing the malignant sample to exhibit benign-like patterns and thereby suppressing its predicted malignancy score. Notably, marginal_adhesion was the strongest contributor in both cases. Figure 8c presents the mean SHAP values across the FP and FN cases, providing a unified view of the features contributing to misclassification. The aggregated contributions highlight marginal_adhesion, bare_nucleoli, and shape_uniformity as the three most influential features.

For the SM-BCDD-O experiment, a single FP was observed as shown in Figure 7d. The SHAP values in Figure 8d indicated that clump_thickness was the dominant contributor, accounting for nearly half of the total attribution, followed by shape_uniformity, size_uniformity, bare_nucleoli, and epithelial_size. This benign sample exhibited unusually high epithelial clustering and nuclear changes, making it appear more similar to malignant cases and triggering an overly sensitive malignant prediction. Compared to SM-BCDD, the oversampled model placed greater emphasis on clump thickness and shape-related features, trading a slight increase in FPs for the complete removal of FNs.

Therefore, across all four datasets, the qualitative error analysis and SHAP-based feature attributions confirm that the distilled SM relies on domain-consistent miRNA expression features in PBCNT and well-known morphological descriptors in WDBC and BCDD. The remaining errors are mainly found in cytologically borderline cases.

Operating Points

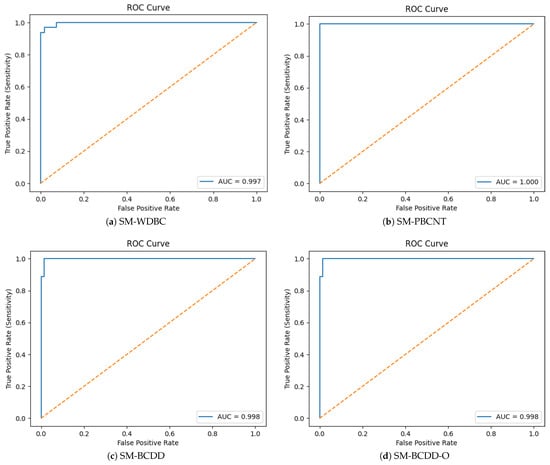

To further evaluate diagnostic reliability, we assessed both discrimination and probabilistic calibration using the predicted probability of the malignant class. The ROC curve was generated by comparing the predicted malignant probability against the ground-truth labels, and the area under the curve (AUC) was computed from the obtained set of False-Positive Rates (FPRs) and True-Positive Rates (TPRs). As shown in Figure 9, the SM demonstrates excellent separability between benign and malignant samples, with across all datasets.

Figure 9.

ROC Curves.

Because screening applications prioritize sensitivity, we selected clinically meaningful operating thresholds by enforcing a minimum recall of 95%. This was implemented by scanning the whole ROC curve and extracting all thresholds where .

From this subset, we selected the threshold with the lowest FPR, thereby maximizing specificity while preserving the required sensitivity. Table 6 reports the optimal thresholds and corresponding performance values. The SM consistently achieved ≥96% sensitivity while maintaining extremely low FPRs (≤0.0185), demonstrating suitability for real-world screening workflows.

Table 6.

Thresholds and Performance Metrics at ≥95% sensitivity.

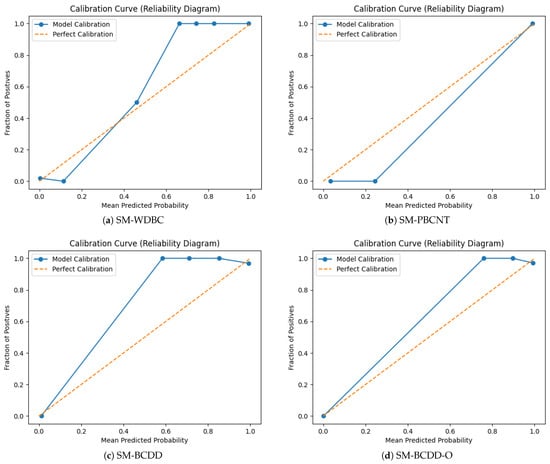

Calibration Analysis

Calibration was evaluated using reliability (calibration) curves, which compare the model’s predicted probabilities with the observed frequency of positive cases. To construct these curves, we divided the predicted probabilities from each configuration into 10 bins and, for each bin, computed the mean predicted probability and the empirical fraction of malignant cases. Perfect calibration corresponds to points lying on the diagonal reference line. As shown in Figure 10, all four configurations align closely with this diagonal, indicating good probability calibration. The SM-BCD-O configuration exhibits the best alignment, with predicted probabilities closely matching true outcome frequencies; its slight upward deviation in the mid-probability range indicates minor underconfidence.

Figure 10.

Calibration Curves.

6.2.3. Deployability Test for KD

This section studies the resource usage of the proposed model. Table 7 summarizes the resource usage results of the experiment on the RPi from our previous work [11], where we tested the TM, SM_Scratch, and SM. The first column contains the measured metrics, and the subsequent columns show the results for the TM, SM_Scratch, and SM. The results show that the proposed SM trains 2.7 times faster than the TM and 1.8 times slower than the SM_Scratch. However, the proposed model has a data preprocessing and inference time of 4.2 ms and 500 ms, respectively. These results are acceptable for non-real-time telemedicine applications. During training, power consumption increased to 3.0–4.5× the nominal device power, while CPU utilization peaked at 88% and memory usage remained below 12% of available RAM. The CPU temperature reached approximately 60 °C without active cooling but remained stable during inference.

Table 7.

Resource Experiment Summary from Previous Work.

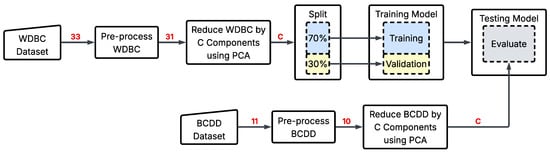

6.2.4. Cross-Dataset Evaluation

This section evaluates how well the models generalize when trained on one dataset and tested on another. It examines how the SM behaves under substantial distributional and feature-mismatch shift. Here, the models TM, SM_Scratch, and SM were trained on WDBC and tested on BCDD. We follow the process in Figure 11 for each model: both WDBC and BCDD were pre-processed independently, including the removal of non-informative identifiers (e.g., id) and normalization. Since the two datasets contain different numbers and types of morphological features, we applied PCA separately to each dataset and reduced them to the same number of components C. This stage enables a consistent input size for all models without imposing an artificial shared feature basis. Then, WDBC was split 70–30% for training–validation partition to allow us to investigate whether the considerable feature reduction has degraded the models’ performance. Finally, the trained models were then evaluated on the PCA-reduced BCDD dataset.

Figure 11.

Cross-Dataset Evaluation Experiment.

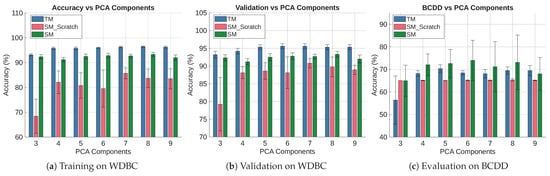

Figure 12 summarizes the cross-dataset experiment at a 95% confidence level over ten repetitions. The training accuracy of the three models is shown in Figure 12a. It shows the TM accuracy is consistently higher than the other models, albeit slightly falling (from 96.23% to 93.12%) with the value of C. The SM_Scratch model performs the worst. It also has lower accuracy and a wider CI due to higher trial-to-trial variation. However, the accuracy of SM shows slight variation across C. It also outperforms SM_Scratch in all cases, showing that it is learning from the TM.

Figure 12.

Performance of TM, SM_Scratch, and SM when Trained on WDBC and Tested on BCDD.

Figure 12b shows the validation results of the experiment. The results follow the same trend as the training accuracy. It shows that the TM validation accuracy closely mirrors its training accuracy. This trend is also true for the SM and SM_Scratch, suggesting that PCA reduction does not cause appreciable overfitting or divergence between training and validation performance. The result also shows that the SM outperforms SM_Scratch at because it has enough features to perform better. However, there is no statistical difference between the two models for , because the Ci of the two overlap in each case. However, as the models are starved of features (), the SM performs better again, likely because the distillation process provides additional informative structure that compensates for the reduced feature space.

Figure 12c depicts the performance of the models when tested on the BCDD dataset. The results show that all models perform poorly on the test dataset. SM_Scratch performs the worst, consistently achieving 65.00–65.33% accuracy with slight variation across trials, as shown by the small CIs. It indicates that the model collapses toward majority-class predictions (i.e., Neural Collapse [70]), reflecting poor transferability across distinct feature domains. The TM accuracy (68.08–70.37%) is statistically the same for . However, it performs the poorest at with a wide CI (), because it removes too much discriminative information for the TM to generalize effectively. The SM shows a wide CI throughout the experiment. Although its mean accuracy (64.99–73.97%) outperforms the TM across all PCA dimensions, they are statistically indistinguishable because their CIs overlap in every case. For the same reason, we are sure that SM outperforms SM_Scratch at and . The figure also shows SM collapsing towards the majority class at , behaving like SM_Scratch rather than the TM, indicating that the feature representation at this dimensionality is insufficient for effective knowledge transfer.

6.3. TM Versus TFLite of TM, SM_Scratch, and SM

In this experiment, we converted the SM into its TFLite version (SM_TFLite). The experiment employed the same TM and SM_Scratch architectures described in Table 3. Following the procedure in Figure 3. However, after training, all three models were saved in both Keras and TFLite formats. This dual-savings process enabled us to assess differences between models stored in their native Keras format and those optimized for deployment on IoT and embedded devices via TFLite conversion.

6.3.1. Accuracy and Size Performance for TFLite

The experimental results, including accuracy, parameter counts, sparsity, and file sizes, are summarized in Table 8. The results of the TFLite conversion are summarized in Table 8. The first three rows present the accuracy, validation accuracy, and TFLite evaluation accuracy for the TM, SM_Scratch, and SM models. In this experiment, we used TensorFlow 2.18.0, but we were unable to obtain validation accuracy during training using the Distiller class. Thus, this value is omitted for the SM.

Table 8.

Performance comparison of TM, SM_scratch, and SM in Keras and TFLite formats.

The table also shows a significant reduction in file size when the model is converted to TFLite. Rows four and five compare the file sizes of the models saved in both Keras and TFLite formats, achieving reductions of 66.81%, 89.30%, and 85.13% for TM, SM_Scratch, and SM, respectively. These reductions highlight TFLite’s effectiveness in reducing model storage requirements, which is valuable for IoT and embedded systems with limited memory. Rows six and seven further analyze the total and zero weights of the models. The results show that no weights were pruned or removed during optimization, confirming that the conversion to TFLite does not change the number of parameters or introduce sparsity. Therefore, TFLite conversion significantly reduces the model size while preserving the model structure.

6.3.2. Deployability Test for TFLite

The deployability test was carried out using the setup in Section 5 and the following procedure:

- Record the system for 30 s to obtain the baseline profile of the RPi.

- Start the system monitor (Sys.Mon.), a Python script that logs CPU temperature along with CPU and memory usage.

- Execute the TM_TFLite inference code and wait for the remainder of the 30 s.

- Execute the SM_Scratch_TFLite inference code and wait for the remainder of the 30 s.

- Execute the SM_TFLite inference code and wait for the remainder of the 30 s.

- Continue recording for 30 s with only the system monitor running in the background before closing it.

- Finally, record for another 30 s to capture any transient responses after closing the system monitor.

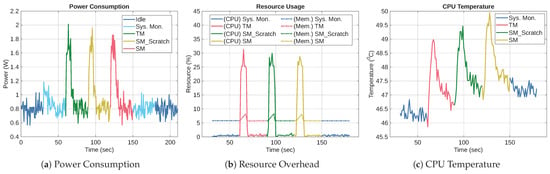

To ensure a fair comparison and eliminate transient effects, 30 s intervals were inserted between each stage of the experiment. Figure 13 shows the power consumption, CPU, and memory performances of the TFLite versions of the three models on RPi. The figures were obtained by repeating the aforementioned experiment 5 times and averaging the results. We labeled the TFLite versions of TM, SM_Scratch, and SM as TM_TFLite, SM_Scratch_TFLite, and SM_TFLite, respectively. Figure 13a presents their power consumption profiles. It shows that TM_TFLite has the highest peak at approximately 2.01 W. It is followed by SM_Scratch_TFLite at 1.96 W and SM_TFLite at 1.86 W. It also shows that all models quickly returned to the baseline idle level of around 0.8 W. The total energy consumption during execution was 6.77 J, 7.12 J, and 5.83 J for TM_TFLite, SM_Scratch_TFLite, and SM_TFLite, respectively. TM_TFLite and SM_Scratch_TFLite have higher energy consumption than that of SM_TFLite, albeit the inference durations of SM_Scratch_TFLite and SM_TFLite were slightly longer than that of TM_TFLite. Consequently, SM_Scratch_TFLite consumed the most energy because it exhibited both high power draw and extended inference duration.

Figure 13.

Performance of TM_TFLite, SM_Scratch_TFLite, and SM_TFLite on RPi.

Figure 13b shows CPU and memory utilization, where CPU usage peaked at 31.3%, 29.9%, and 28.7% for TM_TFLite, SM_Scratch_TFLite, and SM_TFLite, respectively, while their respective memory usage peak at 8.16%, 8.20%, and 8.06%. The memory usage trend has a triangular waveform, revealing the model inference pattern. The waveform’s incline, peak, and decline correspond to data loading, model inference, and memory deallocation, respectively. The memory waveform is in phase with the power waveform, validating the start and end of the inference window.

Figure 13c depicts the CPU temperature. TM_TFLite reached a maximum temperature of 48.98 °C, SM_Scratch_TFLite reached 49.46 °C, and SM_TFLite peaked at 49.95 °C. Although SM_TFLite has the highest temperature, the difference among the three models is less than 1 °C, indicating negligible thermal variation. Therefore, all three models remained within safe operational limits of a passive cooling system.

6.3.3. Latency Test for TFLite

Table 9 compares the latency of TM_TFLite, SM_Scratch_TFLite, and SM_TFLite across different stages of the inference execution. The results show that TM_TFLite required 10.66 ms to load, while SM_Scratch_TFLite and SM_TFLite loaded much faster at 1.99 ms and 2.04 ms, respectively. This result is intuitive since TM_TFLite is larger than the others. The second and third stages contributed minimally and were nearly identical across all three models. The most notable difference appears in the single-sample inference stage. The results show that SM_Scratch_TFLite and SM_TFLite have the same latency, while TM_TFLite takes twice as long to make a prediction. This latency is due to TM_TFLite being larger than the student models. Moreover, the total latency of TM_TFLite is even worse, 76% slower than the student models. These results demonstrate that KD reduced model size and improved responsiveness on the RPi.

Table 9.

Latency breakdown (in milliseconds) for TFLite versions of TM, SM_Scratch, and SM on the RPi.

6.4. TM Versus Pruning (TM_Prune)

This section evaluates the performance of pruning on the TM using the WDBC dataset. The TM was pruned after training to form TM_Prune. In this experiment, TM_Prune was fine-tuned for an additional 50 epochs to mitigate performance loss.

6.4.1. Accuracy and Size Performance for Pruning

Table 10 shows the results of the experiment, comparing the original TM and pruned TM_Prune. Rows 1 and 2 of Table 10 show the accuracy of TM and TM_Prune before and after conversion to TFLite. The results indicate that pruning degrades accuracy, resulting in a 2.49% drop in performance. Rows 3 and 4 present the file sizes of the two models in Keras and TFLite formats. Since the Keras format stores models without optimization, pruning reduced the file size by 66.35%. However, converting the TM directly to TFLite reduced its size by 66.81%, making it more effective than pruning. Moreover, converting TM_Prune to TFLite resulted in a file size only 1.36% smaller than its Keras counterpart, and the difference between the TFLite formats of TM and TM_Prune was just 0.0041%. From a file size perspective, it is therefore more advantageous to convert the TM to TFLite than to prune it.

Table 10.

Performance comparison of TM and TM_Prune in Keras and TFLite formats.

Rows 5–7 present the effect of pruning on the model weights. It reduced the number of active weights by 49.82%, assigning zero to 372,864 parameters. This result has two theoretical benefits: (1) Pruning compressed the TM in its native Keras format from 8811.23 kB to 2964.86 kB, making it easier to store and distribute before deployment. (2) It also introduced sparsity to reduce the inference latency. However, exploiting model sparsity requires specialized hardware, such as GPUs, TPUs, or custom accelerators. Its benefits include reducing computational load and memory access costs.

Comparing the results in Table 8 and Table 10 shows that TFLite conversion alone achieves comparable, or even slightly greater, storage reduction than pruning. In addition, pruning requires specialized hardware capable of sparse operations, which can degrade performance and reduce expressiveness [71].

6.4.2. Deployability Test for Pruning

For the deployability test of the pruned models (see Section 5), the experimental procedure is similar to the TFLite experiment, with a few modifications as follows:

- Record the system for 30 s to establish the baseline power and resource profile of the RPi.

- Start the system monitor (Sys.Mon.), a Python script that logs CPU temperature, CPU utilization, and memory usage.

- Execute the TM inference code and wait for the remainder of the 30 s interval.

- Execute the pruned teacher model (TM_Prune) inference code and wait for the remainder of the 30 s interval.

- Continue recording for 30 s with only the system monitor running in the background before closing it.

- Finally, record for an additional 30 s to capture any transient behavior after stopping the system monitor.

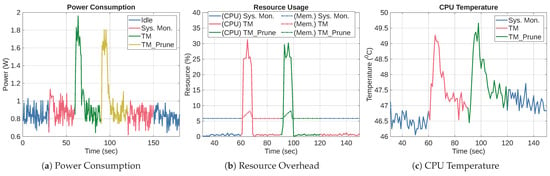

Figure 14 presents the power consumption, CPU, and memory performance of TM and TM_Prune averaged over five runs to reduce random error. Figure 14a shows the power consumption profiles of both models. TM reached a maximum of 1.96 W, while TM_Prune peaked at 1.81 W. Although TM_Prune consumed slightly less power, the difference is too small to be considered an improvement. The total energy consumption of TM and TM_Prune was 6.53 J and 5.27 J, respectively. This result shows that TM_Prune consumes less energy than TM. In addition, the TM energy value is consistent with the result reported in Section 6.3.2, validating the reliability of both TM experiments.

Figure 14.

System Performance Metrics During Execution of TM and TM_Prune.

Figure 14b shows the CPU and memory utilization trends. The results show the characteristic pulse waveforms similar to the TFLite experiment in Section 6.3.2. It also shows TM and TM_Prune peaking at 31.26% and 30.2%, respectively. The graph also shows that TM and TM_Prune have CPU usage similar to TM_TFLite, which is higher than SM_Scratch_TFLite and SM_TFLite. In addition, the memory usage waveform follows a similar pattern to the TFLite experiment, peaking at 8.3% for both TM and TM_Prune. Thus, the CPU and memory overhead of TM and TM_Prune are effectively the same as those of TM_TFLite.

Figure 14c illustrates the CPU temperature behavior during the experiment. TM and TM_Prune produced similar thermal responses, with peak temperatures of 49.27 °C and 49.66 °C, respectively, under passive cooling at a room temperature of 23 °C. The result is similar to the heat dissipation of the TFLite experiment, with a change in temperature of TM, TM_Prune, TM_TFLite, SM_Scratch_TFLite, and SM_TFLite being 2.44 °C, 2.74 °C, 2.82 °C, 2.82 °C, and 2.63°C, respectively. Therefore, the temperature changes for all experiments are similar. In conclusion, these results show that pruning led to a slight reduction in power and total energy consumption without any notable change in CPU load, memory usage, or thermal behavior.

6.4.3. Latency Test for Pruning

Table 11 compares the latency of TM and TM_Prune across the different stages of inference on the RPi. We did not report dataset loading latency because it is independent of the models’ performance. The TM and TM_Prune load the dataset in 2.23 ms and 2.21 ms, respectively. The table shows that the load time of the TFLite model is nearly identical for both models, with TM at 10.54 ms and TM_Prune slightly higher at 10.72 ms. Similarly, the other stages are almost indistinguishable. The total latency for TM_Prune is 13.68 ms, compared to 13.49 ms for TM, representing no improvement from pruning.

Table 11.

Latency breakdown (in milliseconds) for different stages of inference on TM and TM_Prune.

6.5. TM Versus Post-Training Quantization (TM_PTQ, and TM_PTQ_INT)

In this section, we evaluate the effectiveness of PTQ on the TM using the WDBC dataset. After training the TM, we applied the TFLiteConverter with to create TM_PTQ, a weight-only quantized version of the TM. We also applied full-integer quantization to TM to produce TM_PTQ_INT.

6.5.1. Accuracy and Size Performance for PTQ

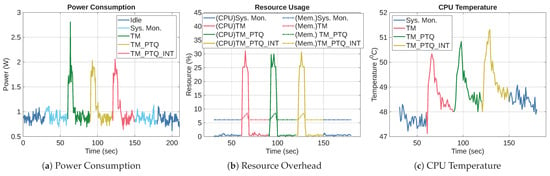

Table 12 shows the accuracy and file sizes of TM, TM_PTQ, and TM_PTQ_INT. The results show that TM_PTQ preserves the original TM’s accuracy at 96.51%, demonstrating that weight-only quantization has no impact on predictive performance on the WDBC dataset. In contrast, the integer-only TM_PTQ_INT shows a 2.32 percentage points reduction in accuracy. This reduction is expected because converting all parameters and activations to integers introduces quantization error and reduces numerical precision. It illustrates the trade-off inherent in full-integer quantization. On the one hand, it enables the model to run entirely in the integer domain, which is necessary for deployment on some resource-constrained hardware. On the other hand, the conversion degrades accuracy.

Table 12.

Performance comparison of TM, TM_PTQ, and TM_PTQ_INT.

The second row of Table 12 shows the TFLite file sizes for TM, TM_PTQ, and TM_PTQ_INT. It shows that TM_PTQ and TM_PTQ_INT are 74.48% and 74.34% smaller than TM, respectively. Interestingly, TM_PTQ_INT is 4.10 kB larger than TM_PTQ despite being fully quantized. To investigate this counter-intuitive result, we implemented a Python script (see tflite_visualization.ipynb in [63]) to analyze the contents of the two files. The breakdown is provided in Table 13. It shows that TM_PTQ_INT is larger because it contains two additional buffers and one extra operator code compared to TM_PTQ. Both models rely on the same core operators (CONV_2D, FULLY_CONNECTED, MUL, ADD, RESHAPE, LOGISTIC, and SOFTMAX) to implement the CNN layers and activations.

Table 13.

TFLite file content analysis of TM_PTQ and TM_PTQ_INT.