Abstract

To address the high computational cost and significant resource consumption of radar Doppler-based target recognition, which limits its application in real-time embedded systems, this paper proposes a lightweight CNN (Convolutional Neural Network) approach for radar target identification. The proposed approach builds a deep convolutional neural network using range-Doppler maps, and leverages data collected by frequency-modulated continuous wave (FMCW) radar from targets such as drones, vehicles, and pedestrians. This method enables efficient object detection and classification across a wide range of scenarios. To improve the performance of the proposed model, this study incorporates a coordinate attention mechanism within the convolutional neural network. This mechanism fine-tunes the network’s focus by dynamically adjusting the weights of different feature channels and spatial regions, allowing it to concentrate on the most informative areas. Experimental results show that the foundational architecture of the proposed deep learning model, RangDopplerNet Type-1, effectively captures micro-Doppler features from range-Doppler maps across diverse targets. This capability enables precise detection and classification, with the model achieving an impressive average recognition accuracy of 96.71%. The enhanced network architecture, RangeDopplerNet Type-2, reached an average accuracy of 98.08%, while retaining a compact footprint of only 403 KB. Compared with standard lightweight models such as MobileNetV2, the proposed architecture reduces model size by 97.04%. This demonstrates that, while improving accuracy, the proposed architecture also significantly reduces both computational and storage overhead.The deep learning model introduced in this study is specifically tailored for deployment on resource-constrained platforms, including mobile and embedded systems. It provides an efficient and practical approach for development of miniaturized low-power devices.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the rapid growth of the consumer drone market has made the surveillance of low-altitude, non-cooperative targets—such as drones—increasingly challenging [1,2,3]. This trend poses significant threats to low-altitude security in urban environments.

In urban environments, the absence of comprehensive regulatory frameworks has contributed to a rise in unauthorized drone operations—commonly referred to as “black flights”—which have caused airspace disruptions, personal injuries, and significant socio-economic damage. Conventional monitoring approaches are proving increasingly insufficient to address the evolving challenges of urban security management.

Current technologies struggle to effectively monitor “low, slow, and small” aerial targets, such as drones and tethered balloons, posing significant challenges to low-altitude surveillance. These limitations highlight an urgent need for more accurate and efficient solutions to safeguard public spaces and critical infrastructure [4,5].

Drone detection technologies generally fall into four main categories. The first is radar-based detection, which offers accurate long-range tracking and identification capabilities. The second involves signal analysis, where systems monitor the communication links between drones and their remote controllers. The third category is visual surveillance, using cameras to detect, classify, and follow drone movements. Lastly, acoustic detection identifies drones by analyzing the unique sound patterns generated by their propellers.

Dumitrescu et al. [6] introduced an acoustic-based system for drone detection and localization, utilizing a spiral array of MEMS (Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems) microphones to capture audio signals. These signals are then processed using machine learning algorithms, enabling accurate identification and classification of drone targets.

However, acoustic-based drone detection systems are highly sensitive to factors such as distance and environmental conditions, which can substantially compromise their accuracy and reliability.

Aydin and Singha [7] developed a vision-based drone monitoring system utilizing the widely adopted YOLOv5 computer vision algorithm. By incorporating pre-trained weights and applying data augmentation strategies, the system achieves efficient detection and tracking of drones. However, the complexity and variability of background environments present substantial challenges to visual accuracy. Drones often blend seamlessly into their surroundings, making it difficult to differentiate them from natural objects or other visual elements.

Allahham et al. [8] proposed a drone detection and identification system utilizing radio frequency (RF) sensing. The system identifies drones by analyzing the communication signals exchanged with their remote controllers. However, its performance may be constrained in scenarios where drones operate autonomously along pre-programmed GPS paths, involving minimal RF interaction with ground control stations.

In recent years, radar micro-Doppler signatures and lightweight convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have gained significant attention across a variety of applications. In [9], Han et al. proposed enhancing drone detection by overlaying multiple Range-Doppler (RD) images, thereby improving the visibility of drone signatures and effectively suppressing noise to boost detection robustness. In [10], Sadeghi et al. introduced a novel approach that replaces traditional batch normalization (BN) layers in CNNs with whitening layers, which not only standardize but also decorrelate feature activations, leading to improved feature learning. In [11], Li et al. employed a Mobile Vision Transformer (MobileViT) to classify radar-derived speech signal images, achieving a balance between high accuracy and low computational cost—making the method well-suited for edge devices. In [12], Li et al. presented RadarTCN, a lightweight model that combines 2D convolution for spatial feature extraction with 3D temporal convolutional networks (TCNs) for modeling temporal dynamics. By avoiding resource-intensive 3D convolutions and multi-view inputs, RadarTCN significantly reduces memory consumption and processing overhead. Lastly, in [13], Xu et al. proposed a compressed and optimized version of ConvNeXt-Tiny, incorporating a multi-scale feature fusion module to enhance fine-grained feature extraction. Their CNNA model demonstrates high classification accuracy while maintaining low computational complexity.

Roldan et al. [14] proposed a drone identification and classification system that leverages micro-Doppler features extracted from radar signals. Micro-Doppler refers to subtle frequency shifts caused by rapid oscillations or rotations of moving components—such as drone propellers or human limbs—during motion. Because different objects (e.g., vehicles, drones, pedestrians) exhibit unique movement patterns, their micro-Doppler signatures also differ. Through spectral analysis of radar echoes, these signatures can be visualized as distinct frequency components and modulation patterns in spectrograms. Such features offer rich information for target recognition, enabling precise classification through detailed signal interpretation.

Through a series of comprehensive and controlled experimental trials, Ignacio et al. developed the RDRD (Real Doppler RAD-DAR) dataset, consisting of more than 17,000 range-Doppler radar samples encompassing drones, vehicles, and pedestrians.Based on this open-source RDRD range-Doppler radar dataset, this study proposes two fully convolutional neural network architectures to investigate drone target recognition and classification.

This paper first presents the architecture of the proposed deep learning model, RangeDopplerNet. It then introduces the data acquisition and signal processing methods used in the RDRD dataset, followed by a description of the preprocessing techniques and the performance evaluation metrics adopted in this study. Subsequently, experimental results are provided and analyzed. Finally, the research is summarized, and key conclusions are drawn.

2. RangDopplerNet Model Architecture

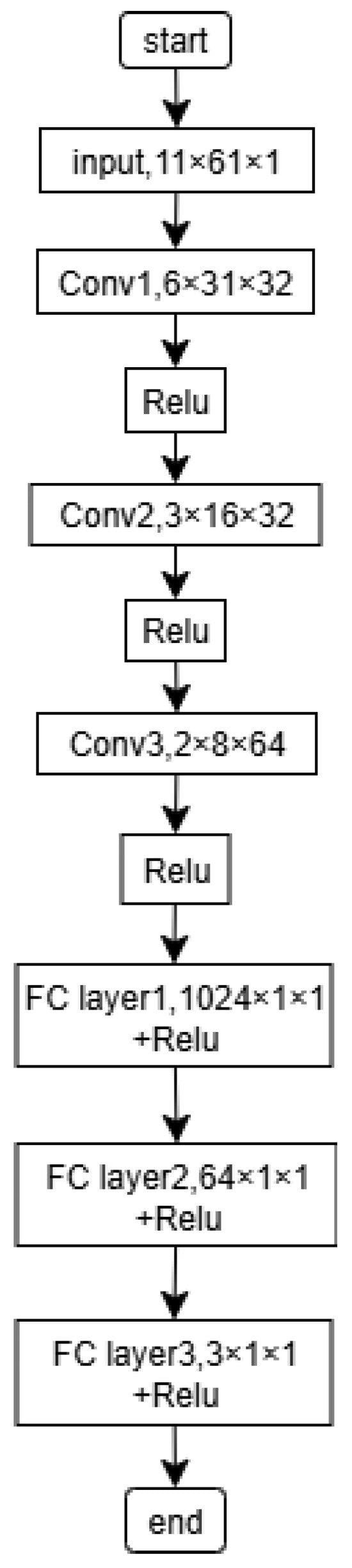

To effectively classify the range-Doppler matrices derived from the test targets, this paper introduces a fully convolutional neural network. The detailed architecture of the proposed model is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameters of RangDopplerNet Type-1.

As shown in Table 1, the RangeDopplerNet Type-1 network is built on a deep convolutional architecture with two main modules: feature extraction and classification. The extraction module uses three convolutional layers with 3 × 3 kernels (32, 32, and 64 channels), each followed by batch normalization and ReLU. These layers progressively transform raw micro-Doppler inputs into higher-level semantic features, capturing target distance, velocity, and motion dynamics while downsampling to reduce complexity and avoid overfitting. The resulting feature map (2 × 8 × 64) encodes essential spatial and velocity information. This is passed to the classification module, which consists of three fully connected layers. The first flattens and reduces dimensionality, the second models complex feature interactions, and the third outputs class probabilities. Together, this layered design enables the network to learn discriminative target representations efficiently, moving from raw signals to meaningful categories in a bottom-up fashion.

Traditional convolution operations are limited by fixed-size receptive fields and depend exclusively on local interactions via sliding windows, which restrict the model’s capability to adaptively emphasize important regions. To address this bottleneck observed in the Type-1 model under complex conditions and to further improve overall system performance, we integrate a Coordinate Attention [15] module into the network architecture. This enhancement effectively addresses the limitations of traditional convolutional networks by reinforcing the integration of spatial positional information with channel-specific feature representations. Figure 1 presents the Type-2 model with the incorporated Coordinate Attention module.

Figure 1.

RangDopplerNet Type-2 Architecture.

The coordinate attention mechanism captures the three-dimensional interaction between spatial coordinates (H × W) and feature channels (C), forming a dual-attention framework that integrates both spatial and channel-level information. This mechanism generates a two-dimensional attention map that adaptively reweights each position within the original feature map. By incorporating this approach, the model enhances its ability to recognize fine-grained local features—such as subtle texture variations—while also improving its comprehension of broader contextual patterns. The resulting architecture, empowered by coordinate attention, is referred to as the RangeDopplerNet Type-2 network.

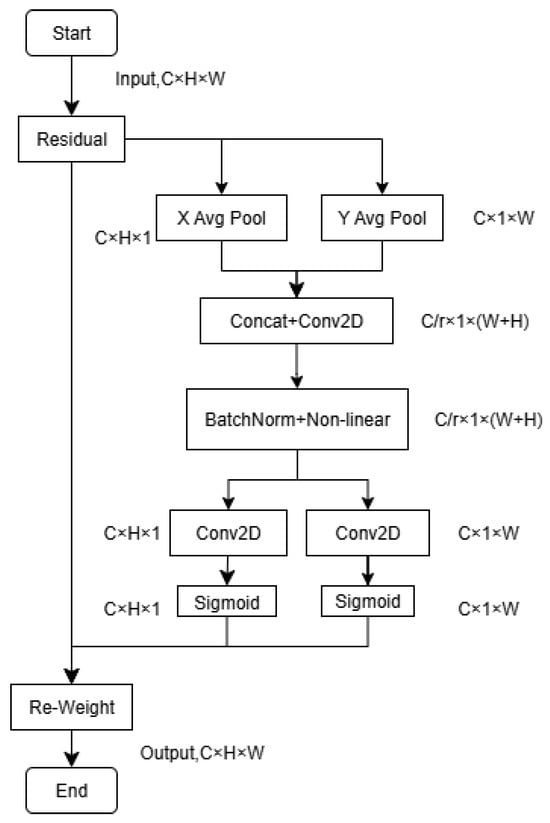

Figure 2 illustrates the architecture of the Coordinate Attention (CA) module, an advanced attention mechanism designed to enhance the feature representation capabilities of deep learning models through spatial coordinate encoding. The core concept of CA lies in embedding positional information directly into channel attention, while simultaneously modeling long-range dependencies across both spatial and channel dimensions.

Figure 2.

Coordinate Attention Module Structure.

The working principle of the coordinate attention mechanism is as [15]:

- 1.

- Decomposing channel attention into direction-aware feature encodingBy applying 1D pooling, the output feature map is aggregated separately along the horizontal (X-axis) and vertical (Y-axis) directions to generate two direction-aware feature vectors. For example: horizontal pooling (X Avg Pool) extracts vertical features of each channel into a tensor with shape C × 1 × W; vertical pooling (Y Avg Pool) extracts horizontal features of each channel into a tensor with shape C × H × 1.Assume the output feature map of the convolutional layer can be expressed as a C × H × W tensor, where C stands for the number of channels, H stands for the height and W stands for the width of the feature map. The horizontal and vertical pooling can be expressed as:where is the horizontal pooling result of the c-th channel; Variable h stands for the h-th row; 1/W stands for the average over W elements; stands for the value at h-th row, i-th column and c-th channel, respectively. Similarly, stands for the vertical pooling result of the c-th channel; Variable w stands for the w-th column; 1/H stands for the average over H elements; stands for the value at j-th row, w-th column and c-th channel, respectively.

- 2.

- Cross-Directional Feature Fusion and Encoding [16]After 1D pooling, we obtain a feature representation along the width direction, denoted as , with a tensor shape of . Similarly, pooling along the height direction yields , shaped as . These two directional feature vectors are then concatenated to form a unified feature tensor of shape . It is combined through a shared 1 × 1 convolutional layer for nonlinear transformation and channel compression. The above-mentioned operation can be expressed as:where stands for the concatenation operation along the spatial dimension. stands for the transpose of . stands for the convolution. stands for the non-linear activation function. f denotes the intermediate feature. And is the number of channels after the channel compression.

- 3.

- Attention Map Construction and Feature Recalibration [17,18]:The intermediate feature f can be split along the horizontal and vertical dimensions into and , respectively. Two separate convolution, are applied to generate the corresponding attention weights along the horizontal and vertical directions. This operation can be expressed as:where and stands for convolution, they are used to transform and back to C channels (same channel number as input) and generate attention map along height (denote as ) and width (denote as ) direction.Finally, the computed attention weights are applied to the original feature map through element-wise multiplication, producing a refined feature map of dimensions C × H × W that emphasizes critical regions more effectively. This operation can be expressed as:where denotes the new feature map after applying coordinate attention, while represents the original feature map. It is evident that the dimension of the feature map remains unchanged after introducing coordinate attention, while the local details within the feature map are selectively enhanced.

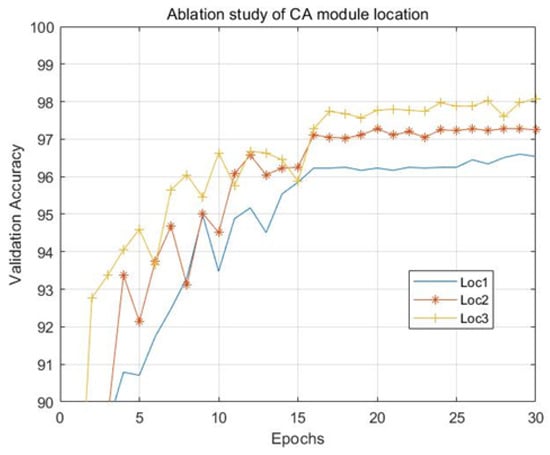

During the development of the RangeDopplerNet Type-2 architecture, we explored various embedding strategies to integrate the Coordinate Attention (CA) module at different depths throughout the network. Specifically, the CA module was applied to the outputs of the initial convolutional layer (Conv1), the intermediate layer (Conv2), and the deeper layer (Conv3), with performance evaluated using the RDRD dataset. Experimental findings indicate that embedding the CA module after Conv3 delivers the highest validation accuracy. This suggests that deeper layers capture more abstract semantic features and exhibit stronger inter-channel dependencies, which the CA module effectively enhances to improve representational power. As shown in Figure 3, the final RangeDopplerNet Type-2 architecture incorporates the CA module directly after Conv3, enabling dynamic reweighting of feature maps and enhancing the model’s directional sensitivity to fine-grained details such as edges and textures.

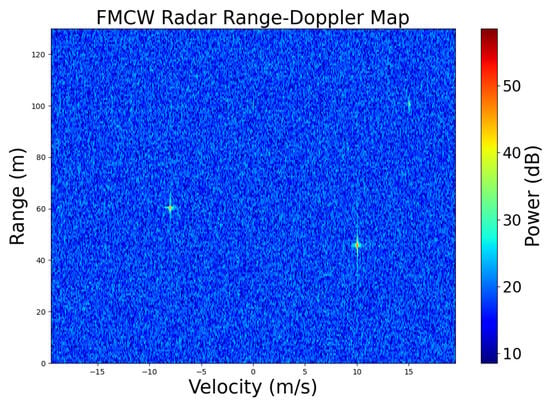

Figure 3.

Doppler Map (simulation).

3. Experimental Data

The RDRD dataset was constructed using a frequency-modulated continuous wave (FMCW) radar system operating at 8.75 GHz with a maximum bandwidth of 500 MHz. This system is built upon the RAD-DAR (Digital Array Receiver) architecture introduced by Duque et al. [19], incorporating a single transmitting antenna and eight receiving antennas. Each receiving antenna consists of eight elements, collectively forming a 64-element 8 × 8 array. Leveraging digital beamforming, the system can simultaneously generate multiple receive beams, eliminating the need for mechanical scanning. This design ensures an optimal trade-off between dwell time and target refresh rate, enabling high-performance detection of small radar cross-section and slow-moving targets such as drones.

Table 2 presents the main parameters of the radar system.

Table 2.

Parameters of Radar System.

Analysis of the motion characteristics of three target types—vehicles, drones, and pedestrians—reveals significant differences in their micro-Doppler signatures. Specifically, these differences manifest as follows:

- Drone Target Characteristics: Drones generally possess a low radar cross-section (RCS), which leads to diminished echo signal strength. Due to their compact design and small physical footprint, the reflected radar energy is confined to a limited set of range cells. Additionally, their micro-Doppler signatures typically exhibit a stable and tightly clustered distribution, reflecting consistent motion patterns from rotating components such as propellers.

- Vehicle Target Characteristics: Vehicles generally possess a high radar cross-section (RCS) owing to their substantial physical size, leading to significant energy dispersion across multiple range cells. Due to their rigid construction and absence of moving parts with relative motion, the resulting Doppler energy distribution tends to be concentrated and stable, reflecting consistent velocity profiles.

- Pedestrian Target Characteristics: Pedestrians generally produce moderate echo signal strength. Their distinctive micro-Doppler signatures stem from gait-induced motion, characterized by relative movement between body parts—most notably, the arms swinging at a higher frequency than the torso. Leg movements exhibit cyclical acceleration and deceleration patterns. Consequently, the Doppler energy is broadly dispersed, capturing the intricate and dynamic nature of human walking behavior.

Micro-Doppler features of a target are typically extracted through spectral analysis of radar echo signals. One widely adopted technique is the Range-Doppler Map (RDM), which simultaneously captures both range and velocity information. This approach offers a detailed representation of the target’s motion dynamics, making it especially effective for the identification and classification of moving objects.

The computation of a range-Doppler map (RDM) involves a structured sequence of radar signal processing operations. Echoes of frequency-modulated continuous wave (FMCW) transmissions are first acquired, providing raw information on target range and velocity. These signals are subsequently demodulated into beat signals, which encode motion parameters essential for downstream analysis. A dual fast Fourier transform (FFT) framework is then applied: the first FFT along the fast-time axis yields range profiles, while the second FFT along the slow-time axis extracts Doppler frequency components, enabling estimation of radial velocity. The resulting two-dimensional frequency-domain representation is visualized as an RDM, with distance cells mapped to the vertical axis, Doppler frequencies to the horizontal axis, and pixel intensity corresponding to signal power expressed in dBm.

Figure 3 presents a simulated range-Doppler map containing three distinct targets. The range and radial velocities of these targets are as follows: Target A (60 m, –8 m/s), Target B (45 m, 10 m/s), and Target C (30 m, 15 m/s). As shown in the figure, three bright spots appear on the range-Doppler map, each corresponding to the specific range and velocity of the respective targets. A negative velocity indicates that the target is moving toward the radar, while a positive velocity signifies motion away from the radar.

The Constant False Alarm Rate (CFAR) detector [20,21] is utilized to process the range-Doppler matrix, offering adaptive thresholding based on ambient noise levels. By dynamically adjusting its detection threshold, CFAR reliably identifies targets even in environments with significant noise or interference, thereby improving detection robustness. The original range-Doppler matrix, sized 4092 × 512, is refined through CFAR processing and cropped to a focused 11 × 61 matrix that isolates the target of interest. This matrix is then fed into the proposed light-weight convolutional neural network (CNN), which autonomously extracts critical spectral features—such as micro-Doppler modulation patterns and energy distribution characteristics—via its convolutional kernels. This approach eliminates the need for manual time-frequency feature engineering and enhances overall classification performance.

4. Model Training

4.1. Training Parameter Settings

This study utilizes the open-source RDRD database to train and evaluate the network. The original dataset contains a total of 17,485 distance-Doppler matrices, categorized into three classes: vehicles, drones, and pedestrians. Specifically, there are 5720 vehicle samples, 5065 drone samples, and 6700 pedestrian samples. The sample sizes across the three categories are relatively balanced, so there is no issue of class imbalance.

The dataset is divided into two parts: a training set (80%) and a validation set (20%). The validation set consists of 3497 samples, including 1143 vehicle samples, 986 drone samples, and 1368 pedestrian samples.

In this experiment, both the training and validation datasets were processed with a batch size of 128. A complete pass through the training dataset is referred to as one epoch, and the network was trained for a total of 30 epochs. The model was optimized using the stochastic gradient descent (SGD) algorithm, with a momentum of 0.9 and an initial learning rate of 0.01. The learning rate was decayed to 10% of its original value every 15 epochs. The training was conducted in an Anaconda environment using the PyTorch 2.7 deep learning framework. To accelerate the convergence of the gradient descent algorithm and prevent issues such as vanishing or exploding gradients during training, the input data was normalized. The data was scaled to follow a distribution with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. The normalization was performed using the formula: where represents the mean of the training dataset and denotes its standard deviation. Based on calculations, the mean and standard deviation used in this study were and , respectively.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

The primary metrics used to evaluate the performance of object detection models include precision, recall, and the F1 score [22]. To compute these metrics, we first define the key components of the confusion matrix. TP (True Positive): The number of samples correctly predicted as positive. TN (True Negative): The number of samples correctly predicted as negative. FP (False Positive): The number of samples incorrectly predicted as positive when the true label is negative. FN (False Negative): The number of samples incorrectly predicted as negative when the true label is positive.

Precision is defined as follows:

Precision quantifies the proportion of true positive predictions among all instances the model classified as positive. Its value spans from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicating greater accuracy in identifying relevant positive cases.

Recall is defined as follows:

Recall, also referred to as sensitivity, quantifies the proportion of true positive instances that the classifier successfully identifies out of all actual positive cases. It ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values reflecting a greater ability to detect relevant positive samples.

F1 Score represents the harmonic mean of precision and recall, offering a balanced metric that captures a model’s overall classification performance.

F1 score can be defined as follows:

5. Results and Analysis

5.1. Experimental Results

To assess the performance of the proposed model, two well-established lightweight convolutional neural networks—MobileNetV1 and SqueezeNext—were selected as baseline references. Notably, both architectures are configured to accept input dimensions of 224 × 224, while the original dataset used in this study consists of matrices sized 6 × 11. To ensure compatibility with these networks, the input data was resized to 224 × 224 using PyTorch’s built-in resize function prior to training and evaluation. MobileNetV1 and SqueezeNext exhibit relatively high model complexity, which is disproportionate to the size of the training dataset and may lead to overfitting. To mitigate this issue, we applied data augmentation techniques to the input samples, including random rotation, cropping, and horizontal flipping. These methods enhance the diversity of the training data and improve the model’s generalization capability.

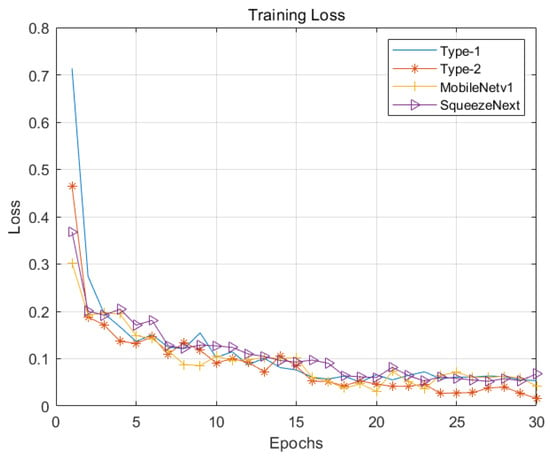

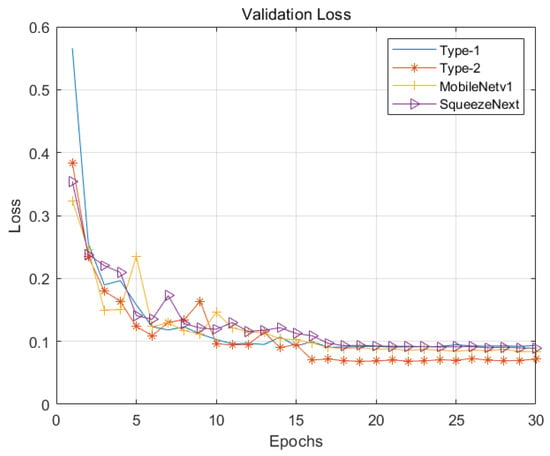

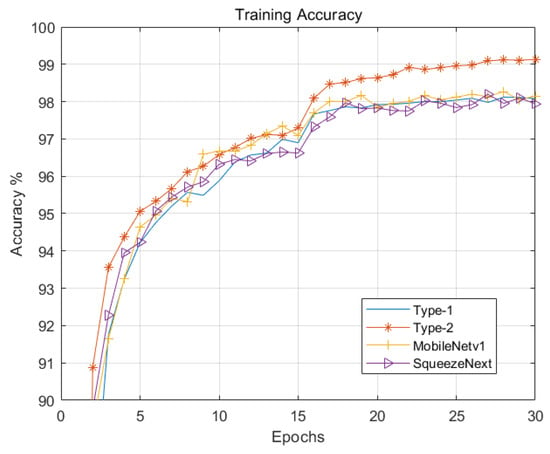

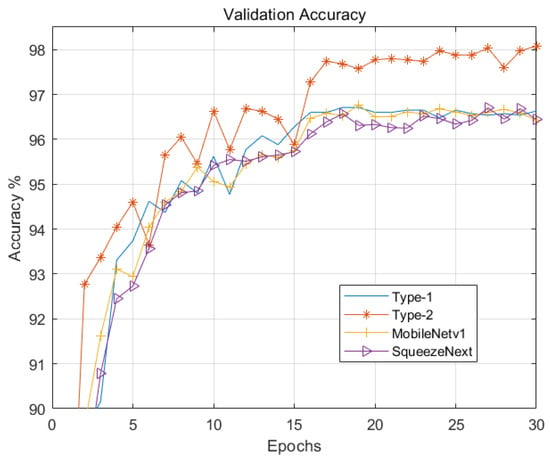

Figure 4 and Figure 5 illustrate the loss curves of the four models on the training dataset and validation dataset, respectively. Figure 6 and Figure 7 illustrate the accuracy curves of the four models on the training dataset and validation dataset, respectively. As shown, the Type-2 model—enhanced with the coordinate attention mechanism—demonstrates slightly better performance than Type-1 in both loss reduction and accuracy. MobileNetV1 and SqueezeNext exhibit comparable performance to Type-1; however, their model sizes are significantly larger, at 12.6 MB and 2.6 MB respectively, compared to just 400 KB for Type-2. Additionally, a noticeable rise in accuracy is observed at epoch 16 in Figure 5, which corresponds to a scheduled reduction in learning rate from 0.01 to 0.001. This adjustment facilitates model convergence and stabilizes training.

Figure 4.

Training loss curve.

Figure 5.

Validation loss curve.

Figure 6.

Training accuracy curve.

Figure 7.

Validation accuracy curve.

Figure 7 compares the validation accuracy of four different models. When the learning rate is relatively high (0.01), all four networks converge rapidly but exhibit significant fluctuations. As the learning rate is reduced to 0.001 (after 15 iterations), the models begin to stabilize. The peak validation accuracies of RangDopplerNet Type-1 and Type-2 are 96.71% and 98.08%, respectively. This 1.37 percentage point improvement in Type-2 demonstrates the effectiveness of incorporating the coordinate attention mechanism in enhancing model performance.

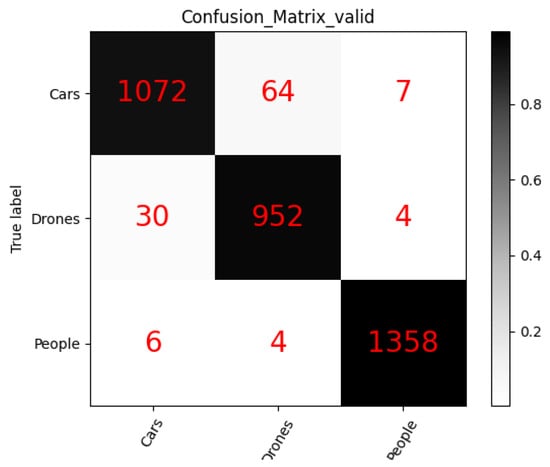

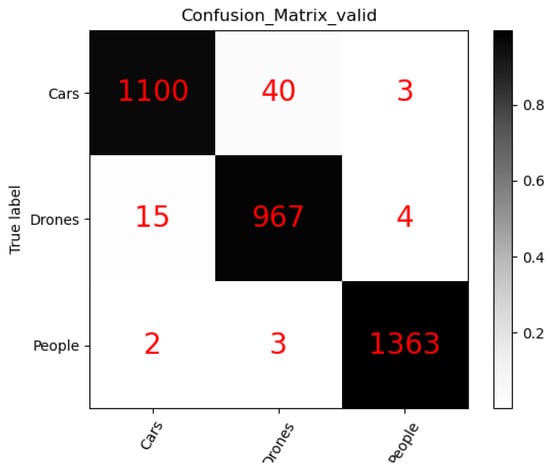

Figure 8 and Figure 9 show the confusion matrices for RangDopplerNet Type-1 and Type-2, respectively [23]. In each matrix, rows correspond to the true class labels, while columns represent the predicted labels. To facilitate understanding, Figure 7 is used as an illustrative example. The second row represents samples with a true label of UAV, totaling 986 instances. Among them, 952 were correctly classified as UAVs, while 30 were misclassified as vehicles and 4 as pedestrians.

Figure 8.

Confusion matrix of RangeDopplerNet Type-1.

Figure 9.

Confusion matrix of RangeDopplerNet Type-2.

The second column of the matrix shows all samples predicted as UAVs. RangDopplerNet Type-1 classified 1020 samples under this category, of which 952 were true UAVs, while 64 were actually vehicles and 4 were pedestrians. Based on Equation (7), the precision for UAV classification is calculated as 952 ÷ 1020 = 93.3%. According to Equation (8), the recall is 952 ÷ 986 = 96.55%. Using Equation (9), the resulting F1 score for UAV classification is 94.92%.

The overall accuracy of RangDopplerNet Type-1 is determined by dividing the total number of correctly classified samples by the total number of samples: 3382 ÷ 3497 = 96.71%.

A comparison of the first rows in Figure 8 and Figure 9 highlights a marked improvement in vehicle classification performance following the integration of the coordinate attention mechanism in RangDopplerNet Type-2.

Specifically, the number of vehicle samples misclassified as UAVs decreased from 64 to 40, and those misclassified as pedestrians dropped from 7 to 3. As a result, correctly identified vehicle samples increased from 1072 to 1100. Based on Equation (8), this corresponds to a recall rate of 1100 ÷ 1143 = 96.24%. According to the first column in Figure 8, the model predicted 1117 samples as vehicles, of which 1100 were accurate, yielding a precision of 1100 ÷ 1117 = 98.48%. These metrics collectively demonstrate that RangDopplerNet Type-2 delivers significant gains over Type-1 in terms of precision, recall, and F1 score for vehicle classification [24].

Figure 10 presents the result of the ablation study on the placement of the CA module. Specifically, Loc1, Loc2, and Loc3 correspond to applying the CA module to the outputs of Conv1, Conv2, and Conv3, respectively. The Y-axis represents the validation accuracy achieved under each configuration. Among the three, Loc3 yields the highest validation accuracy. Furthermore, the results suggest a clear trend: placing the CA module at deeper layers leads to improved performance. A plausible explanation is that deeper layers such as Conv3 capture high-level semantic features that are more pertinent to the classification task. Applying the CA module at these stages allows it to refine representations that are more predictive, thereby improving the model’s focus on critical spatial and channel dimensions. Table 3 summarizes the ablation study results. Loc2 exhibits lower FLOPs compared to Loc1 due to its smaller feature map dimensions. The reduced spatial resolution directly decreases computational requirements. Conversely, Loc3 achieves the highest accuracy despite marginally increased computational complexity. This outcome arises from Loc3’s 64-output-channel configuration, which introduces additional parameter interactions while maintaining compact spatial dimensions. The trade-off between channel depth and spatial resolution demonstrates how architectural choices impact both efficiency and performance. Based on this observation, we adopt the configuration where the CA module is applied to the output of Conv3.

Figure 10.

Result of ablation study on the placement of CA module.

Table 3.

Summarize of Ablation Study Results.

To evaluate the impact of network architecture design, we compared the performance of the proposed model under two configurations: 1, Convolutional Kernel Size: Testing with a larger kernel (7 × 7) versus the baseline (3 × 3). 2, Channel Expansion: Doubling the number of output channels in Layer 2 and Layer 3. The experimental results are summarized in Table 4, which highlights the trade-offs between accuracy, computational efficiency, and model complexity. It can be observed that, larger kernel size (7 × 7) achieves better performance (98.23% vs. 98.08%) due to enhanced spatial feature extraction from broader receptive fields. However, its number of parameters almost doubled compare with the baseline, while its computational complexity surged by 3.5 times compare with the baseline (FLOPs increase from 1.24 M to 4.43 M), primarily due to increased kernel operations. For channel expansion configuration. The model size almost tripled (from 101 k to 375 k) and the computational complexity doubled (FLOPs increase from 1.24 M to 2.48 M) while its performance slightly dropped to 98.03%. It shows that excessive channel scaling (e.g., doubling channels in all layers) amplifies parameter redundancy, leading to overfitting on small datasets.

Table 4.

Summarize of network architecture study.

Table 5 presents a detailed comparison of the confusion matrix results for the two neural network models. According to the F1 scores, RangDopplerNet Type-2 achieved 97.53% accuracy in the vehicle category, surpassing Type-1 by 2.28 points. In the UAV category, Type-2 outperformed Type-1 by 1.97 points. The pedestrian category showed a smaller gain of 0.33 points, which can be attributed to the distinct and easily identifiable characteristics of pedestrians—allowing both models to achieve consistently high recognition performance.

Table 5.

Performance comparison on confusion matrix.

To offer a thorough comparison between the two network architectures, Table 5 presents a side-by-side analysis of their parameter counts and validation performance. To evaluate model complexity, we examine the number of parameters across different architectures, computed using the Torchsummary library. Additionally, to assess the generalization capability and overall effectiveness of the proposed model, this study adopts the architecture introduced by Ignacio et al. as a benchmark. It is worth highlighting that both experimental setups utilized the same publicly available real-world Doppler radar dataset—RDRD (Real Doppler RADAR). This dataset offers a comprehensive collection of radar echo signals along with annotated data from actual scenarios, establishing itself as a vital benchmark in Doppler radar target analysis research.

To more intuitively demonstrate the parameter scale differences among the models, NasNetMobile is selected as the baseline model (denoted as 100%), and the parameter sizes of the other models are expressed as relative percentages. The results are shown in Table 6. It can be observed that the RangDopplerNet Type-1 retains only 2.29% of the parameters of the baseline model. Furthermore, based on RangDopplerNet Type-1, the RangDopplerNet Type-2 not only reduces the parameter size to 2.37% (the proposed architecture reduces model size by 97.04%), but also improves the average accuracy to 98.08%, indicating that the proposed structural modifications effectively reduce model complexity while enhancing recognition performance.

Table 6.

Comparison of number of parameters.

As shown in Table 6, the proposed RangDopplerNet model contains significantly fewer parameters compared to classical architectures such as NasNetMobile and MobileNetV2. Notably, the Type-2 variant of RangDopplerNet has only 101,419 parameters—approximately 3% of MobileNetV2 and just 2.65% of DopplerNet. Despite its compact size, the model delivers performance that is largely comparable to these more complex deep learning networks. Its accuracy is only 0.86 percentage points lower than MobileNetV2, and just 1.4 points below the best-performing DopplerNet.

Compared to the RangDopplerNet Type-1 model, the Type-2 variant achieves a 1.37 point improvement in average accuracy, while its number of parameters increases by only 3.5%. This indicates that RangDopplerNet Type-2 strikes an effective balance between performance and complexity. With its high efficiency and favorable trade-off between accuracy and resource consumption, it is particularly well-suited for deployment on resource-constrained embedded systems.

5.2. Limitations and Prospects

Despite achieving promising recognition performance, this study has notable constraints: 1, Runtime and Power Metrics on Embedded Devices: Current evaluations lack runtime and power consumption measurements on embedded platforms (e.g., Jetson, ARM). These metrics are critical for real-world UAV detection applications where energy efficiency and computational constraints are paramount. 2, Generalization in Multi-Class Scenarios: The model’s robustness in scenarios with coexisting multi-class targets (e.g., mixed UAVs and ground objects) remains underexplored. This limitation stems from dataset constraints and project timelines, which restricted the generation of large-scale multi-class synthetic data. To address these limitations and enhance practical applicability, we propose the following steps in our future work: 1, Embedded Platform Evaluation: Deploy the model on edge devices (e.g., NVIDIA Jetson, ARM Cortex-M) to quantify inference speed, power efficiency, and resource utilization. Additionally, we aim to assess the robustness of the model under varying signal conditions, including different levels of noise, clutter, and interference, which are critical factors for operational UAV detection. 2, Multi-Class Generalization Enhancement: (a) Construct or simulate datasets with diverse multi-class coexistence scenes. (b) Explore domain adaptation and data augmentation strategies to enhance generalization. (c) Benchmark the proposed model against such scenarios to provide a more rigorous evaluation.

6. Conclusions

This study is based on the open-source real-world radar dataset RDRD (Real Doppler RAD-DAR) and it explores the application of deep learning in the detection and identification of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). To meet the real-time signal processing requirements of embedded systems, a lightweight deep learning model is proposed and further optimized. Experimental results demonstrate that the light-weight CNN model developed in this work features a low parameter count and minimal computational overhead, making it highly suitable for deployment on resource-constrained embedded platforms. The proposed model maintains a compact footprint of only 403 KB, corresponding to just 2.37% of the parameters of the classical NasNetMobile network, while achieving an impressive average accuracy of 98.08% across three target categories: vehicles, UAVs, and pedestrians. In the experiments, the enhanced model not only maintains or improves the average accuracy but also significantly reduces the number of parameters. This indicates that the proposed network architecture not only enhances recognition performance but also substantially lowers computational and storage demands, providing a feasible solution for deploying UAV detection models in resource-constrained environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Z. and G.T.; methodology, L.Z.; software, L.Z.; formal analysis, L.Z.; investigation, L.Z.; resources, G.T.; data curation, L.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, L.Z.; writing—review and editing, G.T.; supervision, G.T.; project administration, G.T.; validation, X.Z. and Y.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Startup Foundation for Introducing Talent of NUIST (Grant No. 2022r073), Joint Fund of the Ministry of Education for Equipment Pre-Research (Innovative Teams) (Grant No. 8091B042319) and 173 Plan Project (Grant No. 2021-JCJQ-JJ-0277).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study are openly available. The datasets were downloaded from the following website: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/iroldan/real-dopler-raddar-database accessed on 12 May 2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sun, X.; Wang, S.; Zhang, X.; Wandelt, S. LAERACE: Taking the policy fast-track towards low-altitude economy. J. Air Transp. Res. Soc. 2025, 4, 100058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakhatreh, H.; Sawalmeh, A.H.; Al-Fuqaha, A.; Dou, Z.; Almaita, E.; Khalil, I.; Othman, N.S.; Khreishah, A.; Guizani, M. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs): A Survey on Civil Applications and Key Research Challenges. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 48572–48634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Menouar, H.; Eldeeb, A.; Abu-Dayya, A.; Salim, F.D. On the Detection of Unauthorized Drones—Techniques and Future Perspectives: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 11439–11455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Current Status and Development of Low-Slow-Small Target Surveillance Technology. Radar Sci. Technol. 2020, 18, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Z.; Ma, H.; Qu, Y.; Mao, X. UAV Detection with Passive Radar: Algorithms, Applications, and Challenges. Drones 2025, 9, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrescu, C.; Minea, M.; Costea, I.M.; Cosmin Chiva, I.; Semenescu, A. Development of an Acoustic System for UAV Detection. Sensors 2020, 20, 4870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydin, B.; Singha, S. Drone Detection Using YOLOv5. Eng 2023, 4, 416–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahham, M.S.; Khattab, T.; Mohamed, A. Deep Learning for RF-Based Drone Detection and Identification: A Multi-Channel 1-D Convolutional Neural Networks Approach. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Informatics, IoT, and Enabling Technologies (ICIoT), Doha, Qatar, 2–5 February 2020; pp. 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.K.; Lee, J.H.; Jung, Y.H. Convolutional Neural Network-Based Drone Detection and Classification Using Overlaid Frequency-Modulated Continuous-Wave (FMCW) Range–Doppler Images. Sensors 2024, 24, 5805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi Adl, Z.; Ahmad, F. Whitening-Aided Learning from Radar Micro-Doppler Signatures for Human Activity Recognition. Sensors 2023, 23, 7486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Geng, Y.; Gao, Y.; Ding, Q.; Li, D.; Liu, N.; Chen, J. Doppler Radar-Based Human Speech Recognition Using Mobile Vision Transformer. Electronics 2023, 12, 2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, M.; Jing, H.; Liu, Z. RadarTCN: Lightweight Online Classification Network for Automotive Radar Targets Based on TCN. Sensors 2024, 24, 2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Gao, Z.; Zhai, Y.; Wang, Q.; Gao, Z.; Xu, Z.; Zhou, Y. A CNNA-Based Lightweight Multi-Scale Tomato Pest and Disease Classification Method. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldan, I.; del Blanco, C.R.; Duque de Quevedo, Á.; Ibañez Urzaiz, F.; Gismero Menoyo, J.; Asensio López, A.; Berjón, D.; Jaureguizar, F.; García, N. DopplerNet: A convolutional neural network for recognising targets in real scenarios using a persistent range–Doppler radar. IET Radar Sonar Navig. 2020, 14, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Q.; Zhou, D.; Feng, J. Coordinate Attention for Efficient Mobile Network Design. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 13708–13717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yao, L.; Chen, L.; Lin, B.; Cai, D.; He, X.; Liu, W. CrossFormer: A Versatile Vision Transformer Hinging on Cross-scale Attention. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2108.00154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahdanau, D.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1409.0473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque de Quevedo, Á.; Ibañez Urzaiz, F.; Gismero Menoyo, J.; Asensio López, A. Drone detection and radar-cross-section measurements by RAD-DAR. IET Radar Sonar Navig. 2019, 13, 1437–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkler, G.; Minkler, J. Cfar: The Principles of Automatic Radar Detection in Clutter; Magellan Book Company: Bamberg, Germany, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z.; Li, J.; Song, C.; Xu, Z.; Wang, X. Compressed Sensing-Based Multitarget CFAR Detection Algorithm for FMCW Radar. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 9160–9172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep Learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swaminathan, S.; Tantri, B.R. Confusion Matrix-Based Performance Evaluation Metrics. Afr. J. Biomed. Res. 2024, 27, 4023–4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, D.M.W. Evaluation: From precision, recall and F-measure to ROC, informedness, markedness and correlation. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.16061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).