Abstract

Active-control coils on Keda Torus eXperiment (KTX) are used to suppress error fields and mitigate MHD instabilities, thereby extending discharge duration and improving plasma confinement quality. Achieving effective active MHD control imposes stringent requirements on the coil power supplies: wide-bandwidth and high-precision current regulation, deterministic low-latency response, and tightly synchronized operation across 136 independently driven coils. Specifically, the supplies must deliver up to ±200 A with fast slew rates and bandwidths up to several kilohertz, while ensuring sub-100 μs control latency, programmable waveforms, and inter-channel synchronization for real-time feedback. These demands make the power supply architecture a key enabling technology and motivate this work. This paper presents the design and simulation of the KTX active-control coil power supply. The system adopts a modular AC–DC–AC topology with energy storage: grid-fed rectifiers charge DC-link capacitor banks, each H-bridge IGBT converter (20 kHz) independently drives one coil, and an EMC filter shapes the output current. Matlab/Simulink R2025b simulations under DC, sinusoidal, and arbitrary current references demonstrate rapid tracking up to the target bandwidth with ±0.5 A ripple at 200 A and limited DC-link voltage droop (≤10%) from an 800 V, 50 mF storage bank. The results verify the feasibility of the proposed scheme and provide a solid basis for real-time multi-coil active MHD control on KTX while reducing instantaneous grid loading through energy storage.

1. Introduction

The Reversed Field Pinch (RFP) is a magnetic confinement fusion device characterized by a toroidal magnetic field that reverses direction at the plasma edge, offering advantages such as lower external magnetic field requirements and natural capability for high plasma beta operation [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. The Keda Torus eXperiment (KTX) is a RFP device independently designed and constructed by the University of Science and Technology of China [9,10]. It represents one of the major non-tokamak magnetic confinement fusion facilities in China, alongside stellarator-type experiments. With a design plasma current of up to 1 MA and a stored magnetic energy of 25 MJ, KTX provides a versatile platform for investigating magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) instabilities and developing active control techniques under the RFP configuration [11,12]. Active MHD control aims to suppress both magnetic error fields and plasma instabilities, thereby extending discharge duration and improving plasma confinement performance [13,14,15,16,17,18]. Realizing such control requires an integrated system consisting of active control coil, high-precision and wide-bandwidth power supplies, magnetic sensors, and a real-time feedback control network. Among these components, the power supply system is of central importance, as it must deliver rapidly varying current waveforms under stringent dynamic and synchronization requirements [19,20,21,22,23,24,25].

Several key technical challenges must be addressed [26]. First, each of the 136 active-control coils is driven by an independent power supply, demanding precise multi-channel synchronization with deterministic latency below 100 µs. Second, to achieve high-bandwidth feedback control with microampere-level current precision up to several kilohertz, the system must reconcile the trade-off between fast dynamic response and fine current resolution. Finally, stable operation of such a large-scale distributed control system requires effective coordination among control, protection, and communication subsystems.

To meet these challenges, the KTX active-control coil power supply system is designed to support a variety of plasma operation scenarios, including magnetic error-field compensation and feedback stabilization of MHD instabilities. These physics objectives define the key performance requirements—current amplitude, response speed, regulation accuracy, and synchronization tolerance. The developed system adopts a modular, energy-storage-based AC–DC–AC topology and employs a hierarchical control architecture integrating FPGA-based synchronization with DSP-based current regulation. The system’s performance and control effectiveness are validated through detailed circuit-level and system-level simulations, confirming its capability to satisfy the stringent dynamic requirements of active MHD control in the RFP configuration.

The following section presents the system model, simulation methodology, and analysis results used to evaluate the proposed power supply design under representative operation scenarios.

2. Power Supply Requirements

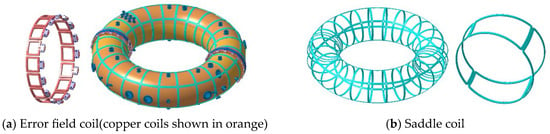

The active control system of the KTX device is designed to provide comprehensive magnetic field regulation and instability suppression. It consists of two principal subsystems, as shown in Figure 1. The first is the error-field active control subsystem, implemented by 16 × 2 sets of local correction coils, which are employed to compensate for intrinsic magnetic field errors and to enable detailed investigations of error-field-induced plasma instabilities. The second is the plasma instability active control subsystem, realized through 104 sets of global control coils, which are utilized to actively suppress or mitigate various forms of plasma instabilities during discharge operation.

Figure 1.

Active control coil.

The parameters of active control coil on the KTX device are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Coil parameters.

During system operation, sufficient current must be delivered to the active control coils to generate the desired magnetic field strength. To achieve this, the active-control coil power supply system is required to fulfill the following functional specifications:

- (1)

- High-power and high-frequency operation: The power supply must be capable of delivering high-power (up to 160 kW) and high-frequency (up to 3 kHz) AC/DC output.

- (2)

- Wide-bandwidth current control: The system should provide current regulation with an effective control bandwidth of up to 3 kHz to meet dynamic plasma control requirements.

- (3)

- Independent multi-channel operation: Each coil shall be powered by an independent channel, enabling customized current waveforms and timing sequences according to different control objectives.

- (4)

- Fast transient response: The system must exhibit a rapid response to control commands, enabling the output current to transition from its initial state to the required target value within 100 µs, thereby supporting real-time feedback control.

- (5)

- Flexible and precise control capability: The control system should offer high flexibility and precision, ensure full compatibility with the KTX central control system, and support programmable current waveform generation and parameter configuration.

Although the power supply parameters for error field coils and saddle coils are different, as shown in Table 2, a unified modular design is considered to cover the requirements of two types of coils, achieving control of load currents with different characteristics by configuring different control parameters. In addition, considering the limited installation space and high reliability requirements within the KTX hall, the power units must adopt a modular and scalable architecture, supporting hot-plug, fault isolation, and networked control. These requirements collectively form the basis for the subsequent circuit topology and control strategy design.

Table 2.

Power supply performance requirements.

3. Main Circuit Design

The power supply for active control coils is characterized by short duration and high power. Considering the power limitations of the electrical grid and the requirements for magnetic fields of different intensities and frequencies in physical experiments, the output current value and frequency of the power supply need to be continuously adjustable. Therefore, the hardware topology of the power supply adopts an AC-DC-AC structure based on energy storage technology, which can charge the energy storage module with relatively low power before energizing the coils. After the energy storage module is fully charged, it serves as the energy source to provide high-power energy to the coil loads, thereby reducing the power load on the electrical grid.

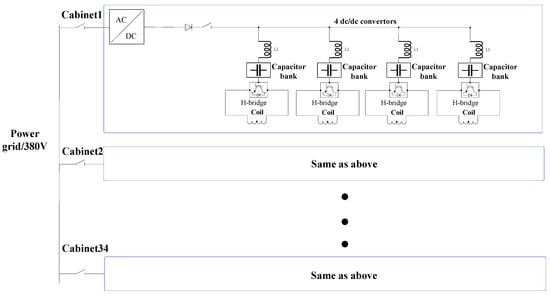

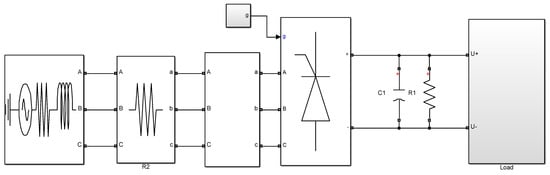

As shown in Figure 2, there are 136 load coils in total that require independent power supply, with a one-to-one power supply configuration between power supplies and coils. The main circuit adopts an H-bridge converter structure based on high switching frequency IGBTs, which can increase the switching frequency and achieve low latency and fast response load characteristics through feedback control algorithms.

Figure 2.

Main circuit topology (Ellipsis “…” indicates repetition of identical circuit modules for cabinets 2–33).

The power supply is directly fed by the electrical grid. The grid output is rectified by a rectifier to charge capacitor banks, with each capacitor bank providing DC power for a single H-bridge converter. Finally, the H-bridge converters output the required current to supply power to the coil loads. Power cabinets 1–34 have identical circuits, with each cabinet including one charging power supply and four power modules. The 34 power cabinets provide a total of 136 sets of H-bridge converters to supply power to 136 sets of active control coils. Filters are connected at ends of the loads to filter out high-frequency harmonics caused by IGBT switching du/dt.

The power supply operates in full energy storage repetitive pulse mode. The energy of the capacitor banks is replenished by the charging power supply before discharge. The charging time from 0–100% energy is 60 s. After the capacitor banks are fully charged, the switch connecting to the charging power supply is opened, and the energy stored in the capacitor banks supplies power to the active control coil loads. After each experiment is completed, the switch between the capacitor banks and charging power supply is closed again, and the charger refills the capacitor banks with energy, repeating this cycle continuously.

Four sets of DC support capacitors are connected in parallel and powered by one charging power supply. The advantage of this design is that it enables automatic current sharing among the internal DC support capacitors of the 4 sets of DC/AC power supplies in the same group. The current waveforms of the four coils exhibit phase differences and display complementary peaks and troughs. Owing to this complementary behavior, a smaller capacitance in the preceding stage can effectively sustain the energy output required by the subsequent stage. During operation, the four DC supporting capacitors achieve automatic energy balancing, thereby enhancing the overall performance and output capability of the power supply system.

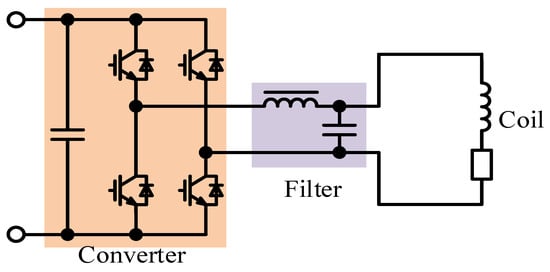

As shown in Figure 3, each power module unit mainly consists of DC support capacitors, H-bridge converter, and EMC filter. The DC support capacitors provide energy for the coils, the H-bridge converter is responsible for converting the energy from the DC support capacitors into time-varying current required by the coils, and the EMC filter performs smooth filtering on the output current of the H-bridge converter and reduces interference.

Figure 3.

Power module topology.

The EMC filter is designed as a second-order LC low-pass filter to attenuate high-frequency switching harmonics generated by the IGBT H-bridge operating at 20 kHz. The filter cut-off frequency fc is designed to be approximately 1/10 of the IGBT switching frequency (20 kHz) to ensure effective attenuation of switching ripple while maintaining the required control bandwidth up to 3 kHz. This gives fc ≈ 10 kHz. Once the cut-off frequency is determined, the inductance L and capacitance C values are selected through practical component availability and engineering considerations rather than pure calculation. Inductance selection L = 25 μH, Capacitance selection C = 10 μF.

Maximum energy consumption per coil:

The coil current is:

The voltage value required for each coil is:

Therefore, the maximum voltage of the coil does not exceed 400 V. To improve the power supply output current change rate, the output voltage is set to 800 V. To maintain the relative stability of DC voltage, setting the maximum voltage drop of the capacitor during each discharge to not exceed 20%, then the capacitance value C can be calculated as:

where E is the energy stored in the capacitor; C is the capacitance value; U is the voltage value across the capacitor.

Considering a certain margin, 50 mF is selected. Under this condition, the maximum voltage drop in a single discharge is 10%.

As described in the system architecture (Figure 2), the 136 H-bridge modules are organized into 34 power cabinets, with each cabinet containing 4 independent power modules, where each module is equipped with its own 50 mF capacitor bank. Therefore, each cabinet has a total capacitance of 4 × 50 mF = 200 mF, and the entire system comprises 136 × 50 mF = 6.8 F of total energy storage capacity.

At the nominal DC-link voltage of 800 V, the total stored energy across all 136 modules is calculated as:

This substantial energy storage provides several key advantages: First, each module operates independently with its own energy buffer, eliminating concerns about shared capacitor depletion when multiple coils are activated simultaneously. Second, the distributed energy storage architecture enhances system reliability—a failure in one capacitor bank affects only one coil rather than multiple coils. Third, the 2.176 MJ total energy capacity far exceeds the worst-case energy requirement for 100 ms operation at maximum current, providing significant safety margin.

The maximum charging voltage of the capacitor is 800 V, using 300 A/1200 V high-frequency IGBT modules as the inverter bridge. The voltage margin of the IGBT is 1200 V, the current of a single IGBT is 300 A, and considering a continuous operating time of 100 ms, the margin is sufficient. The operating frequency of the IGBT directly affects the high-frequency output capability of the power supply.

Regarding network load balancing, the energy storage approach reduces grid power requirements from a potential 21.8 MW (136 × 800 V × 200 A ≈ 21.8 MW) peak to a manageable total of 100 kW for recharging all 136 capacitor banks (listed in Table 2). The 60 s recharge cycle and 120 s discharge interval ensure that the grid loading remains constant and predictable.

4. Control Architecture Design

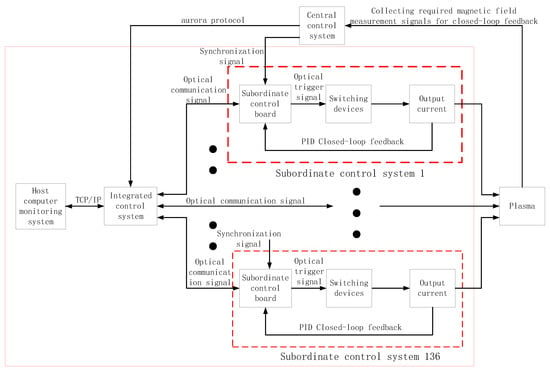

The power supply is primarily controlled by the KTX central control system, which sends data to the power supply control system through the Aurora protocol. The power supply control system provides rapid response according to the given signals to meet the required experimental requirements. Meanwhile, the power supply control system can accept remote parameter settings from the host computer control system and transmit fault status to the host computer control system for display. The entire control system can implement both remote and local control operations, with the structure shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Control architecture block diagram (Arrows indicate signal flow direction; red boxes represent functional grouping; ellipsis “…” indicates additional subordinate control systems 2–135 with identical structure).

The power supply control system is implemented using an FPGA-based comprehensive control system and DSP-based lower-level control systems. The comprehensive control system and central control system transmit control data through the high-speed communication protocol Aurora. The comprehensive control system receives serial control data and operational logic control system signals from the central control system, then outputs them in parallel to each lower-level control system through FPGA with low latency, achieving an overall control delay of less than 100 μs for power supply control.

The system adopts a PID-based closed-loop real-time control method. The power supply detects the difference between the output current and the current setpoint from the central control system. After PID parameter calculation, the IGBT switching duty cycle is obtained, generating optical pulse trigger signals to control the IGBT switching on and off, thus achieving the desired power supply output current.

Each H-bridge converter operates in direct current-control mode using PID feedback. The output current is measured by a high-precision current sensor (Hall effect sensor with 0.1% accuracy) and compared with the setpoint current received from the central control system via the Aurora protocol. The error signal drives the PID controller, which directly modulates the IGBT switching duty cycle to regulate the output current. Although no explicit voltage control loop is used, the control algorithm incorporates feedforward compensation based on real-time DC-link voltage measurement. The PID controller output (duty cycle command) is automatically scaled by the factor 800 V/Vdc(t) to compensate for voltage variations, ensuring consistent current control performance throughout the discharge cycle.

Before the power supply system operates, the host computer control system can remotely set the power supply’s operating parameters (such as discharge time, power protection values, etc.), and can manually set given signals on the host computer interface to coordinate with local power supply debugging experiments. The accompanying host computer control software has a user-friendly human–machine interface. During the discharge process, the comprehensive control system uploads the power supply’s operating parameters (including given signals from the central control system) to the host computer control monitoring system via TCP/IP communication and saves them.

During the discharge process, the central control system calculates the power supply setpoints in real-time based on plasma conditions and sends discharge data to the comprehensive control system through the Aurora protocol. Simultaneously, the central control system sends synchronization signals to the lower-level control systems. The comprehensive control system distributes the received data to each lower-level control system via optical communication signals. The lower-level control systems send optical trigger signals to the switching devices according to the given data at the moment of synchronization signal triggering. The power supply outputs the required current through the switching device actions while collecting output current signals for closed-loop feedback. The power supply output current directly affects the plasma state. The central control system collects plasma state signals for closed-loop feedback and sends the calculated setpoint signals to the power supply control system, completing one control cycle.

5. Simulation

Based on the circuit topology and control system design, an analog simulation model was built, as shown in Figure 5. The power supply circuit of each coil is completely identical, one module is selected for simulation.

Figure 5.

Simulation model.

The key simulation parameters used in the Matlab/Simulink model are summarized in Table 3. The IGBT switching frequency is set to 20 kHz, corresponding to a PWM period of 50 μs. The control loop operates at the frequency with a sampling time of 1 μs. The PID controller parameters are tuned as follows: proportional gain Kp = 1, integral gain Ki = 20, and derivative gain Kd = 0.0001. These values are optimized through iterative simulation to achieve fast response while minimizing overshoot and steady-state error.

Table 3.

Key simulation parameters.

The DC-link capacitor bank has a total capacitance of 50 mF with an equivalent series resistance (ESR) of 2 mΩ, representing realistic electrolytic capacitor characteristics. The EMC output filter consists of a second-order LC filter with L = 25 μH and C = 10 μF, providing effective attenuation of switching harmonics above 20 kHz.

PID closed-loop feedback control was adopted, with three types of setpoint methods selected: DC setpoint, AC sinusoidal setpoint, and arbitrary waveform setpoint. The simulation results are shown as follows.

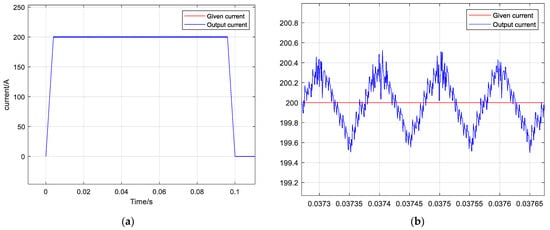

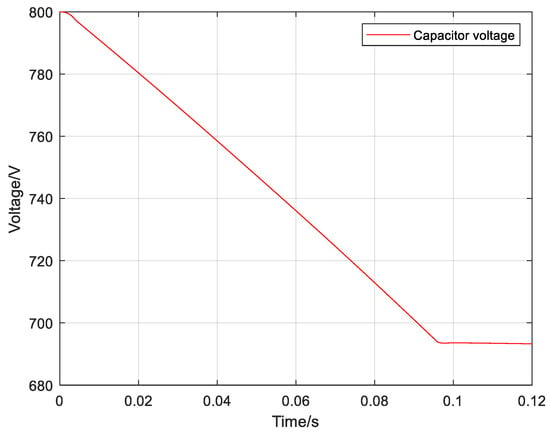

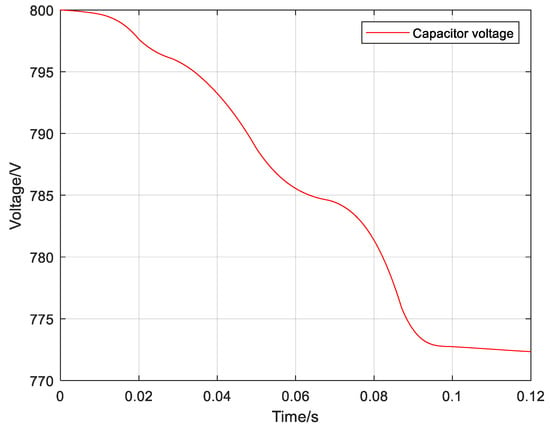

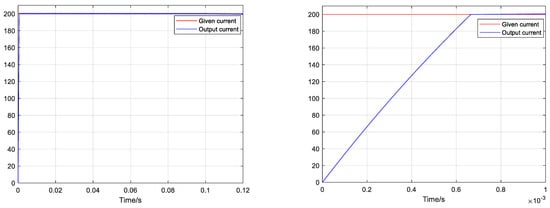

When the setpoint signal is a DC waveform, the simulation waveforms are shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7. The output current value can rapidly follow the changes in the setpoint current value. The maximum output current is 200 A, the steady-state ripple is 0.5 A, and the capacitor voltage drops from 800 V to 695 V.

Figure 6.

Output current waveform with DC setpoint. (a) Overall current response showing setpoint tracking; (b) Current flat-top ripple waveform (±0.5 A steady-state ripple).

Figure 7.

Capacitor voltage waveform with 200 A DC setpoint.

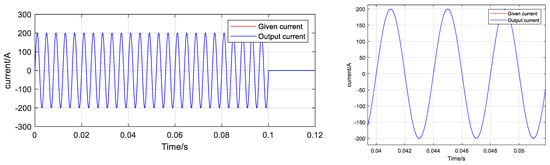

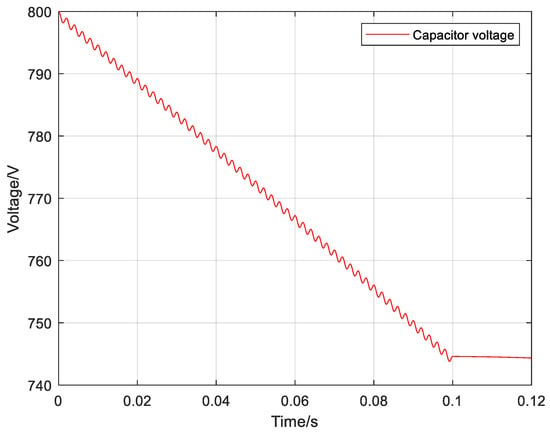

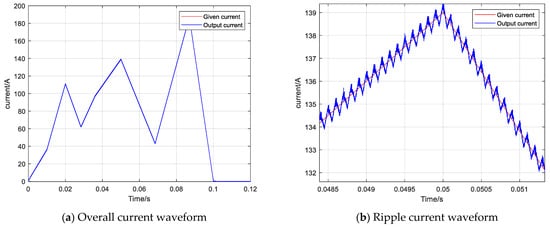

When the setpoint signal is an AC sinusoidal waveform, the simulation waveforms are shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9. The maximum output sinusoidal current is 200 A, the output current frequency is 250 Hz, the capacitor voltage drops from 800 V to 745 V, and the output current can rapidly follow the changes in the setpoint signal.

Figure 8.

Output current waveform with AC setpoint.

Figure 9.

Capacitor voltage waveform with AC setpoint.

When the setpoint signal is an arbitrary waveform, the simulation waveforms are shown in Figure 10 and Figure 11. As the red line coincides with the blue line, the output current value can rapidly follow the changes in the setpoint current value. The maximum output current is 200 A, the ripple is 0.5 A, and the capacitor voltage drops from 800 V to 695 V.

Figure 10.

Output current waveform with arbitrary waveform setpoint.

Figure 11.

Capacitor voltage waveform with arbitrary waveform setpoint.

To explicitly validate the dynamic performance specifications, dedicated step-response simulations were conducted. As shown in Figure 12, the current is set to 200 A, the output current value can rapidly follow the changes in the setpoint current value. Current response showing rise time tr~530 μs (10–90%) and current is increase from 20 A to 180 A. Instantaneous current slew rate di/dt showing peak value of 340 A/ms, ten times exceeding the ≥30 A/ms requirement.

Figure 12.

Current step-response waveform.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents the design and simulation of an active control coil power supply system for the Keda Torus eXperiment (KTX), a key reverse field pinch device for magnetic confinement fusion research. The system employs an AC-DC-AC topology based on IGBT technology, providing independent power to 136 coils through modular H-bridge converters for flexible control of error field and saddle coils. It achieves high performance with fast response (≤100 μs), precise current control accuracy (0.5 A), and an energy storage-based design that reduces grid load while delivering high instantaneous power. A hierarchical control architecture combining FPGA-based comprehensive control and DSP-based local control, integrated with the Aurora protocol and PID feedback, ensures real-time plasma feedback control with a total delay of less than 100 μs.

A performance comparison with existing fusion power supply systems is provided in Table 4. Although the KTX active control power supply has lower parameters than RFX in terms of current and duration, it offers certain advantages in bandwidth, voltage, and response time, which are critical for real-time MHD feedback control in the RFP configuration.

Table 4.

Comparison with existing fusion power supply systems.

This work provides a solid foundation for the implementation of active MHD control in KTX, which is crucial for suppressing plasma instabilities and improving confinement performance. The successful design and simulation verification demonstrate that the proposed power supply system can effectively support the advanced plasma control requirements of the KTX device, contributing to the advancement of magnetic confinement fusion research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.R. and Y.W.; methodology, Q.R. and Y.W.; software, Q.R. and X.L.; validation, Q.R., H.L., T.L. and W.L.; formal analysis, Q.R. and Y.W.; investigation, W.L. and H.L.; resources, Y.W., H.L. and T.L.; data curation, Q.R., H.L. and Z.T.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.R.; writing—review and editing, Y.W. and W.L.; visualization, Q.R. and Z.T.; supervision, Y.W., X.L., H.L. and T.L.; project administration, Y.W.; funding acquisition, Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China, grant number 2017YFE0301700.

Data Availability Statement

The simulation data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ongoing research and proprietary considerations related to the KTX experimental facility. The Matlab/Simulink simulation models and parameters used in this work are described in detail in Section 5 and Table 3, allowing for reproduction of the results.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge the Power Supply Team of the KTX as well as members who have participated mega-ampere plasma operation and made great contribution to the KTX Project.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Qinghua Ren, Yingqiao Wang, Xiaolong Liu, Weibin Li were employed by the company China National Nuclear Corporation. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Peruzzo, S.; Agostini, M.; Agostinetti, P.; Bernardi, M.; Bettini, P.; Bolzonella, T.; Canton, A.; Carraro, L.; Cavazzana, R.; Dal Bello, S.; et al. Design Concepts of Machine Upgrades for the RFX-mod Experiment. Fusion Eng. Des. 2017, 123, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piovan, R.; Agostinetti, P.; Bustreo, C.; Cavazzana, R.; Escande, D.; Gaio, E.; Lunardon, F.; Maistrello, A.; Puiatti, M.E.; Valisa, M.; et al. Status and Perspectives of a Reversed Field Pinch as a Pilot Neutron Source. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2020, 48, 1708–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigatto, L.; Baruzzo, M.; Bettini, P.; Bolzonella, T.; Manduchi, G.; Marchiori, G.; Villone, F. Control System Optimization Techniques for Real-Time Applications in Fusion Plasmas: The RFX-mod Experience. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2017, 64, 1420–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsell, P.R.; Kuldkepp, M.; Menmuir, S.; Cecconello, M.; Hedqvist, A.; Yadikin, D.; Drake, J.R.; Rachlew, E. Reversed Field Pinch Operation with Intelligent Shell Feedback Control in EXTRAP T2R. Nucl. Fusion 2006, 46, 904–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettini, P.; Marrelli, L.; Voltolina, D.; Cavazzana, R.; Marchiori, G.; Marconato, N.; Specogna, R.; Spizzo, G.; Torchio, R.; Zanca, P.; et al. Error Fields’ Computation in the RFX-mod2 Reversed Field Pinch. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2021, 57, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnesotto, F.; Miano, G.; Rubinacci, G. Numerical Analysis of Time-Dependent Field Perturbations Due to Gaps and Holes in the Shell of a Reverse Field Pinch Device. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1985, 21, 2400–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanpei, A.; Okamoto, T.; Masamune, S.; Kuroe, Y. A Data-Assimilation Based Method for Equilibrium Reconstruction of Magnetic Fusion Plasma and its Application to Reversed Field Pinch. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 74739–74751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manduchi, G.; Luchetta, A.; Taliercio, C.; Rigoni, A.; Martini, G.; Cavazzana, R.; Ferron, N.; Barbato, P.; Breda, M.; Capobianco, R.; et al. The Upgrade of the Control and Data Acquisition System of RFXMod2. Fusion Eng. Des. 2021, 167, 112329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Lan, T.; Mao, W.; Li, H.; Xie, J.; Liu, A.; Wan, S.; Wang, H.; Zheng, J.; Wen, X.; et al. Overview of Keda Torus eXperiment initial results. Nucl. Fusion 2017, 57, 116038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Mao, W.; Li, H.; Xie, J.; Lan, T.; Liu, A.; Wan, S.; Wang, H.; Zheng, J.; Wen, X.; et al. Progress of the Keda Torus eXperiment Project in China: Design and mission. Plasma Phys. Control. Fusion 2014, 56, 094009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Li, H.; Tu, C.; Deng, T.; Li, Z.; Luo, B.; Xie, J.; Lan, T.; Liu, A.; Mao, W.; et al. MHD Mode Analysis Using the Unevenly Spaced Mirnov Coils in the Keda Torus eXperiment. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2019, 47, 3298–3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Song, S.; Li, H.; Yolbarsop, A.; Song, K.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, W.; Chen, Z.; Rao, X.; et al. Real-time MHD feedback control system in Keda Torus eXperiment. Fusion Eng. Des. 2023, 195, 113968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hender, T.C. Chapter 3: MHD stability, operational limits and disruptions. Nucl. Fusion 2007, 47, S128–S202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavinato, M.; Gregoratto, D.; Marchiori, G.; Paccagnella, R.; Brunsell, P.; Yadikin, D. Comparison of Strategies and Regulator Design for Active Control of MHD Modes. Fusion Eng. Des. 2005, 74, 549–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchiori, G.; Luchetta, A.; Manduchi, G.; Marrelli, L.; Soppelsa, A.; Villone, F.; Zanca, P. Advanced MHD Mode Active Control at RFX-mod. Fusion Eng. Des. 2009, 84, 1249–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, D.; Vitelli, R.; Zaccarian, L.; Zabeo, L.; Neto, A.; Sartori, F.; McCullen, P.; Card, P. The New Error Field Correction Coil Controller System in the Joint European Torus Tokamak. Fusion Eng. Des. 2011, 86, 1034–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, E.A.; Brunsell, P.R. Error Field Correction in Reversed Field Pinch with Feedback Stabilization of Resistive Wall Mode. Plasma Phys. Control. Fusion 2025, 67, 025017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, P.T.; Suttrop, W.; Belonohy, E.; Bernert, M.; McDermott, R.M.; Fischer, R.; Hobirk, J.; Kardaun, O.J.W.F.; Kocsis, G.; Kurzan, B.; et al. High-Density H-Mode Operation by Pellet Injection and ELM Mitigation with the New Active In-Vessel Saddle Coils in ASDEX Upgrade. Nucl. Fusion 2012, 52, 023017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Xiong, Z.; Liu, P.; Wang, Y.; Xuan, W.; Li, B.; Chen, Y. Vertical Instability Active Controlled Power Supply of HL-3 Tokamak. Fusion Eng. Des. 2025, 220, 115311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toigo, V.; Gaio, E.; Piovan, R.; Barp, M.; Bigi, M.; Ferro, A.; Finotti, C.; Novello, L.; Recchia, M.; Zamengo, A.; et al. Overview on the Power Supply Systems for Plasma Instabilities Control. Fusion Eng. Des. 2011, 86, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitarin, G.; Bello, S.D.; Grando, L.; Peruzzo, S. The design of 192 saddle coils for RFX. Fusion Eng. Des. 2003, 66–68, 1055–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griva, G.; Musumeci, S.; Bojoi, R.; Zito, P.; Bifaretti, S.; Lampasi, A. Cascaded Multilevel Inverter for Vertical Stabilization and Radial Control Power Supplies. Fusion Eng. Des. 2023, 189, 113473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Gao, G.; Wang, S.; Zhang, L. Design and Analysis of a Pulsed Coil Power Supply for the DIII-D Tokamak. Fusion Eng. Des. 2023, 194, 113740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, A.; Gaio, E.; Novello, L.; Matsukawa, M.; Shimada, K.; Kawamata, Y.; Takechi, M. Reference Design of the Power Supply System for the Resistive-Wall-Mode Control in JT-60SA. Fusion Eng. Des. 2015, 98-99, 1053–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaio, E.; Zamengo, A.; Toigo, V.; Zanotto, L.; Rott, M.; Suttrop, W. Conceptual Design of the Power Supply System for the In-Vessel Saddle Coils for MHD Control in ASDEX Upgrade. Fusion Eng. Des. 2011, 86, 1488–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toigo, V.; Gaio, E.; Balbo, N.; Tescari, A. The power supply system for the active control of MHD modes in RFX. Fusion Eng. Des. 2003, 66–68, 1143–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).