Abstract

Radar coincidence imaging (RCI) is widely used in military reconnaissance, hovering unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), and non-local Earth observation due to its superior super-resolution imaging performance. However, in portable radar exploration or UAV remote sensing scenarios, the imaging resolution may be limited by the size constraints of the radar’s aperture. Moreover, although the resolution of RCI depends on the randomness of the signal, an excessively random signal setup may be difficult to implement in engineering applications due to rapid frequency jumps and related issues. Therefore, it is essential to achieve super-resolution imaging while maintaining a small aperture and an effectively random signal. In this paper, an amplitude-random linear frequency modulation (AR-LFM) waveform is employed in RCI using a dual-frequency, dual-phase-center, and dual-polarized antenna (DDPA). A multi-channel structure is introduced, and different frequencies and polarization modes are combined using the proposed method, which provides more independent signal information while maintaining a small aperture and effectively reducing signal coherence. This approach increases the singularity between grid points in the target area, thereby enhancing the effective rank of the reference matrix. The simulation results show that the angular resolution of the proposed imaging method is 15 times higher than that of conventional radar imaging. Furthermore, the proposed structure can improve the resolution improvement factor (RIF) by more than two times compared with the traditional RCI method using a conventional antenna and random signals.

1. Introduction

Recently, ghost imaging (GI), based on statistical correlations of light fields, has attracted widespread attention [1,2,3]. In GI, a bucket detector without spatial resolution records the total intensity after interaction with the target, while a detector array in the reference path measures the corresponding illumination pattern. Meanwhile, a detector array in the reference optical path measures the corresponding illumination pattern. Correlating these two signals enables the reconstruction of the target’s spatial structure even without conventional imaging conditions.

RCI is a radar imaging technique inspired by ghost imaging (GI) [4,5,6]. It uses multiple transmit antennas emitting time–space-independent, mutually uncorrelated random waveforms so that each target scatterer is tagged with unique random information in the echoes. By correlating the transmitted and received signals, the receiver reconstructs the target scattering distribution from a single pulse. Unlike traditional synthetic aperture radar (SAR) and inverse SAR (ISAR), which require relative motion to synthesize angular resolution, RCI achieves high-resolution imaging purely from the statistical independence of its random waveforms and is thus insensitive to transmitter–receiver motion, enabling short imaging times, independence from target dynamics, and relaxed requirements on uniform angular sampling. Moreover, RCI offers high sensitivity [7,8], super-resolution capability [4,9], and strong robustness to complex scattering [4,10], and it has been applied to three-dimensional imaging, remote sensing, multispectral imaging, and atmospheric turbulence imaging.

In multi-channel RCI research, multiple transmitting channels are typically employed to radiate independent random illumination patterns, thereby enhancing imaging resolution. Li et al. [9] proposed a random-excitation-array-based imaging system, which eliminates the dependence on target motion and achieves a tenfold super-resolution reconstruction purely through the statistical independence of random waveforms among antenna elements. Sun et al. [8] demonstrated a photonics-based multiple-input multiple-output (MIMO) radar digital coincidence imaging system that attains three-dimensional super-resolution by exploiting the spatiotemporal independence and broadband fusion of multi-channel optically modulated waveforms. Shafai et al. [4] proposed a frequency-diverse Cassegrain antenna designed to generate spatially uncorrelated radiation fields, thereby improving angular resolution through multi-channel differential reconstruction. Such multi-channel configurations expand the information dimensionality through independent channel emissions and markedly improve imaging resolution, but at the cost of larger physical apertures and increased synchronization complexity.

To mitigate aperture expansion, frequency-diverse RCI schemes transmit random radiation fields sequentially at distinct frequencies to emulate multi-channel observations. H. Saeidi-Manesh et al. [10] proposed a method employing multi-frequency random radiation to generate independent observation matrices at different frequency bins, achieving joint range–angle super-resolution reconstruction in the frequency domain. Lin et al. [7] proposed a phase-coded stochastic frequency radiation field, which enhances the rank of the observation matrix through frequency-domain randomness, thereby achieving high-resolution reconstruction under a single-pulse condition.

Meanwhile, several imaging schemes exploit dual-polarization information to further enhance resolution. Y. Liu et al. [11] used polarization modulation to adapt to the target distribution and radar angular requirements, thus improving imaging resolution. He et al. [12] used the polarization matrix to describe target echoes under different polarization states, thereby enhancing the information dimensionality through dual polarization. Liu et al. [13] proposed a polarization–modulation spectral method that uses fully polarized signals and a polarization filter bank to separate different target information and improve spatial resolution.

These dual-polarization imaging methods require highly consistent signals, so polarization channels must be aligned, compensated, or modulated, which increases algorithmic complexity. Additionally, these polarization methods either assign different polarization directions to distinct array elements or alternate the transmission of different polarization signals over time to capture the multi-dimensional scattering information of the target, thereby improving imaging resolution and structural recognition capability. However, the former increases the spatial complexity of the array, effectively expanding the aperture, whereas the latter lengthens the observation period and inevitably complicates system implementation.

To further enhance the angular resolution and imaging quality of RCI without enlarging the physical aperture, this work proposes a DDPA and its corresponding imaging method. The dual-polarization information in this method can be directly combined and processed. First, dual LFM signals are multiplied by time-varying random amplitude vectors derived from stochastic sequences to ensure the temporal independence and randomness of the transmitted signals, thereby enriching the diversity of the observation matrix and improving imaging accuracy. Benefiting from the dual-frequency operation of the proposed antenna, different array elements operate at different frequencies, forming frequency-diverse illumination patterns in space. Each element adopts a high-isolation dual-feed structure for which its two ports realize independent phase centers with orthogonal polarization directions, enabling dual-polarization and dual-phase-center operation on a single patch and, thus, dual-frequency dual-polarization transmission without aperture expansion. The high isolation performance allows both polarizations to function concurrently within a compact structure, significantly enhancing angular and polarization resolution.

This study is organized as follows. In Section 2, the signal model for RCI is presented, followed by the imaging method involved in the proposed structure and the corresponding resolution analysis. In Section 3, the design principle and simulation results of the proposed antenna are described. In Section 4, the imaging results obtained by applying the antenna design from Section 3 to the imaging model in Section 2, together with a comparison against conventional imaging methods, are provided. Finally, the conclusions are summarized in Section 5.

2. Imaging Model

2.1. Signal Model

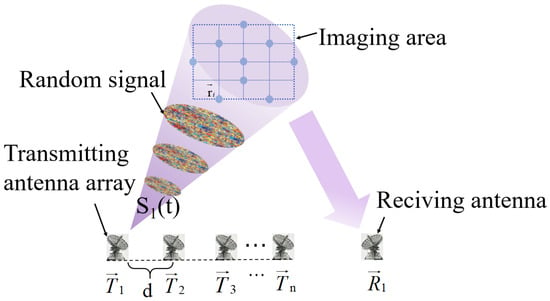

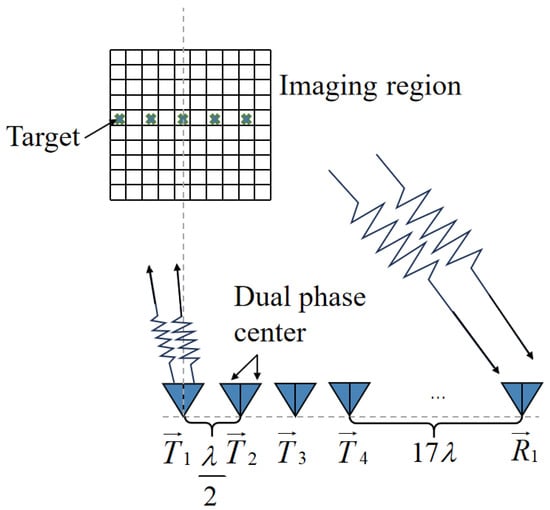

The RCI system consists of N transmitters and a single receiver. As shown in Figure 1, the spacing between array elements is denoted by d. represents the discrete-time excitation signal emitted by the nth transmitter. As discussed in the previous section, the signals transmitted in the RCI system are random in nature. The advancement of high-speed DAC technology enables the realization of signals with controllable random amplitude modulation. In the proposed signal model, a stochastic process is applied to the amplitude of the linear FM signals to ensure the randomness of the transmitted signals, as expressed in (1).

where is the stochastic process function in a linear FM signal, modulated by zero-mean Gaussian noise on the amplitude. denotes the center frequency at which the system operates, and represents the slope of the linear FM. RCI is based on the principle of ghost imaging, in which the heat source is completely independent in both time and space; therefore, the radar transmission signal is also independent in time and space. The cross-correlation function of the radar transmission signal is expressed as (2):

Figure 1.

Geometry of the RCI system.

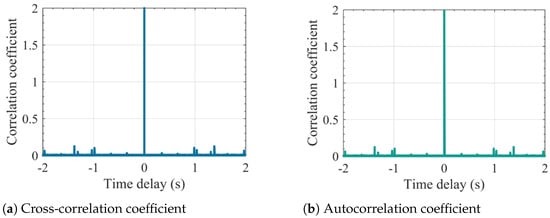

Among them, when , represents the cross-correlation function of the transmitted signals from different transmitters. In this case, for , indicating that the transmitted signals from different transmitters are uncorrelated and, therefore, spatially independent. When , represents the autocorrelation function of the transmitted signal from the same transmitter at different time delays. only when , implying that signals transmitted at different times are uncorrelated and thus temporally independent. Figure 2 shows the autocorrelation and cross-correlation functions of the transmitted random waveforms, in which the signals exhibit strong independence in both space and time. The magnitude of the correlation peak reflects the performance of the imaging resolution. A smaller correlation peak corresponds to a higher degree of time-domain signal independence, which in turn indicates higher imaging resolution.

Figure 2.

Correlation coefficient of the transmitted signal. (a) Cross-correlation coefficient; (b) autocorrelation coefficient.

2.2. Imaging Method

The signal at a target point within the imaging region can be expressed as (3)

where denotes the position vector of the ith target point in the imaging region, and denotes the position vector of the nth transmitter.

The imaging region is divided into L grids, and each grid corresponds to a scattering coefficient , where represents the scattering coefficient at the center of each grid. The time delay is determined by the distance vector from the center of the grid to the transmitter (or receiver). The signal received by the receiver can be written as (4):

where denotes the echo signal, and represents the scattering coefficient of the grid located at position . If this grid does not contain a target, the value of is zero.

The actual received echo signal with noise can be expressed as (5):

where N denotes the noise vector composed of all time-domain sampling points.

To illustrate the imaging principle in greater detail, the equation is expanded into a matrix form. The time domain is discretized as shown in (6). The imaging region is divided as described in (7) based on the smallest resolvable grid, and the scattering coefficients are defined in (8):

Among them, . Substituting Equations (6)–(8) into (9) yields the observation matrix expressed in (10), where the column vectors represent the samples of the time domain corresponding to the same scattering cell, and the row vectors represent the samples of the spatially partitioned grids at a given sampling time:

After this, Equation (9) can be written as (10):

The observation matrix is used as prior information, and the echo signal matrix is correlated with the observation matrix. Equation (11) is then solved to obtain the scattering coefficients of the target, thereby reconstructing the target image.

The number of samples in the time domain must be at least equal to the number of discretization cells in the imaging region to guarantee that the system’s matrix is non-singular and that the equation admits a unique solution. The rank of the equation is influenced by the degree of independence of the transmitted signals in the time domain, while the rank of the columns is affected by the degree of independence of the transmitted signals in the spatial domain. This highlights the importance of maintaining the space–time independence of transmitted signals in the RCI imaging algorithm.

The overall imaging reconstruction process is summarized as follows:

- Design a transmission signal with random characteristics such that the transmitted signals satisfy the property of space–time independence.

- Divide the imaging region into L grids, where each grid is assigned a scattering coefficient corresponding to the center point of the grid.

- Calculate the distance from each transmitting source to every grid in the imaging region.

- Compute the received signal by modeling the propagation of the transmitted signal after reflection from the target in the imaging region to the receiving source.

- Sample k signals in the time domain to formand solve the equation to obtain the scattering coefficients and reconstruct the image.

2.3. Analysis and Comparison of Resolution

Improving resolution relies on extracting more independent information from the reference matrix, which is directly related to its rank [14]. If the rank is limited, the information contained in the reference matrix becomes more redundant and cannot adequately distinguish the target details, resulting in low imaging resolutions. As mentioned in [9], the effective rank of the observation matrix is constrained by the number of transmitting antennas. Based on the transmitted signal waveform given in (1), Equation (10) can be rewritten as (11):

where is defined in (12), is defined in (13), and D is defined in (14):

The amplitude–phase matrix and the time–delay–frequency matrix in the reference matrix are determined by the amplitude, phase, time delay, and frequency of the transmitted signal. From (13) and (14), it can be seen that the number of time-domain samples k and the number of scattering grids L are much larger than the number of transmitting elements ; therefore, the rank of the conventional observation matrix satisfies (15):

where n denotes the number of channels of the transmitting antennas. The effective rank of the observation matrix determines the number of independent scattering points that the imaging system can resolve. As shown in (15), the effective rank of the observation matrix is limited by the number of transmitting antennas.

The effective rank of the observation matrix reflects the degree of linear independence among its column vectors. Enhancing the effective rank necessitates reducing column-wise correlation within the observation matrix to increase the independence of transmitted information. Diversity introduced in frequency, polarization, and phase-center position decorrelates the reference matrix, thereby decreasing its condition number and improving its effective rank.

To further enhance the effective rank, we increase the dimensionality of the reference matrix by designing the radar with a dual-frequency, dual-phase-center configuration. In this architecture, different phase centers are associated with different polarization directions to acquire richer target information. The dual-frequency dual-phase-center configuration thus increases the effective rank of the reference matrix. Based on this, Equation (10) is written as Equation (16):

In this configuration, different phase centers correspond to different polarizations; thus, in theory, there are two transmission channels, and . The measurements at different polarizations are stacked and processed jointly. It should be noted that the measurements from different polarizations ( and ) are concatenated along the column dimension of the reference matrix rather than combined in power. In other words, the dual-polarization data are stacked to expand the observation matrix and increase its rank, thereby enhancing the amount of independent information available for imaging. This stacking operation differs from incoherent power summation, as each polarization channel retains its complex phase information and contributes independently to matrix diversity.

Adding signals at different frequencies makes the row vectors more independent from one another, and the effective rank reflects the amount of independent information that can be distinguished within the matrix. The newly introduced frequency components provide supplementary and statistically independent information relative to the original signals, thereby enhancing the effective rank of the observation matrix by increasing the number of linearly independent row vectors and improving the matrix’s information diversity. The principle of the dual-polarization dual-phase-center configuration follows the same concept.

The condition number of the reference matrix can be defined as (17):

Here, and denote the maximum and minimum singular values of , respectively. According to the properties of matrices, can be decomposed as (18):

where D is the time-sampling unit’s diagonal matrix, is the amplitude–phase modulation matrix, and is the time-delay–frequency phase matrix. Since D is a unit-modulus diagonal matrix (i.e., ), the main contribution to the condition number arises from and . Because the randomness of (as shown in Equation (12)) and is primarily determined by the design of , it is necessary to control the phase matrix to reduce the condition number.

To analyze the condition number, the column coherence is first introduced, which measures the correlation between two column vectors corresponding to the angles and , as defined in (19):

where denotes the signal vector at angle , which contains all relevant signal information associated with that angle. This signal may include information from multiple domains, such as time, frequency, and polarization. Similarly, denotes the signal vector at angle , corresponding to the signal information at a different angle. These vectors are typically used to analyze the correlation between signals observed at two different angles.

Based on this, for any two columns of the Gram matrix, the condition number can be expressed as (20):

According to this formula, the condition number increases as the correlation between the two signal vectors increases, which consequently reduces the numerical stability of the matrix.

Further analysis indicates that the maximum coherence governs the condition number of the matrix. Therefore, (21) can be derived as follows:

Consequently, decreasing correlations lead to an increased effective rank and a lower condition number, indicating the enhanced numerical stability of the observation matrix.

On the other hand, in classical radar signal processing, it is assumed that the main-lobe width of the ambiguity function of the transmitted waveform determines the time-delay resolution of the radar. In the RCI system, the resolution is determined by the accumulated main-lobe width of the ambiguity functions of the waveforms emitted by different transmitting antennas. The ambiguity function of the radar waveform for a single transmitter is given by (22), assuming a constant-modulus envelope such that :

The ambiguity function of the array signal after coherent summation across all transmitters is given by (23):

represents the propagation time-delay difference produced by the nth transmitter between two look directions, and it is related to the path-length difference by , where c denotes the speed of light.

As discussed in [15], the range resolution of RCI is still influenced by factors such as signal bandwidth and SNR. Here, the factors affecting the angular resolution of RCI are analyzed in detail. Assume that the position coordinates of two independent point targets are denoted as and . Then, the time-delay difference between the signals transmitted from the nth antenna and received after reflecting from and , respectively, is given by (24).

where denotes the effective baseline (or phase-center spacing) of the nth transmitter. Substituting (24) into (23) yields

Since the width of the main lobe of the ambiguity function corresponds to the distance from the main peak to the first zero, the phase term in the above equation can be expressed as (26).

From (27), it can be seen that the main-lobe width is determined by the carrier frequency , the modulation rate , and the baseline . A narrower main lobe corresponds to a smaller angular difference and a higher correlation between the corresponding signal components. In other words, the main-lobe width can be regarded as dependent on the coherence . Thus, the main-lobe width decreases as the coherence magnitude decreases, and the condition number of the matrix decreases accordingly. Specifically, as shown in (28), we have the following:

Therefore, reducing the condition number of the observation matrix improves its numerical stability. This demonstrates that both the improvement in numerical stability and the reduction in the condition number originate from the same underlying mechanism, namely, the reduction in signal correlation, which simultaneously explains the physical and mathematical origins of the improved imaging quality.

Let and . Taking the derivative with respect to , we have the following:

Since in the numerator, both the numerator and the denominator are positive; therefore, .

Therefore, as increases, the main-lobe width becomes narrower, and the minimum resolvable angle decreases accordingly. The DDPA proposed in this paper employs dual polarization to realize a dual-phase-center configuration, in which the electromagnetic field radiated by the antenna is emitted from two distinct points. Compared with a single-phase-center antenna, is increased, and the clarity of the radar image is improved by more than a factor of three, as demonstrated in Section 4.

To verify the advantages of the proposed DDPA–RCI imaging method in terms of angular resolution and numerical stability, this subsection presents a theoretical baseline analysis based on a conventional synthetic aperture radar (SAR) imaging model under identical geometric and parameter conditions. The SAR system employs the same parameter settings as those used in the simulations in Section 4, including center frequencies of 7.63 GHz and 11.6 GHz, an aperture size of , and an angular interval of .

For a uniform linear aperture , the angular resolution of a traditional SAR system can be approximated by its half-power beamwidth (HPBW), as given in (30):

Taking , we obtain at 7.63 GHz and at 11.6 GHz. These results are clearly inferior to the RCI value of , indicating an improvement of approximately 8–13 times.

The observation matrix of an SAR system can be regarded as a Fourier-type operator with a limited aperture and field of view. Its effective rank can be approximated by the spatial–bandwidth product:

where denotes the imaging field of view. Using , the results yield at 7.63 GHz and at 11.6 GHz. In contrast, the proposed DDPA–RCI configuration employs dual-frequency, dual-polarization, and dual-phase-center expansion, as formulated in (16), to increase the effective rank to above eight. This expansion effectively enhances system decorrelation and consequently improves the overall imaging performance.

For the SAR linear-aperture model, the column coherence between two steering vectors at angles and can be expressed via (32):

The corresponding condition number of the subspace can be written as (33).

Substituting and yields and at 7.63 GHz and and at 11.6 GHz. These results indicate strong inter-column correlation and a large condition number, which implies poor numerical stability. By introducing additional phase diversity through dual-frequency and dual-polarization operation, the proposed DDPA–RCI method significantly reduces the worst-case coherence , resulting in a nearly well-conditioned matrix with .

The DDPA–RCI method achieves an angular resolution of , which is approximately 8–13 times finer than that of the SAR baseline (). Moreover, the proposed observation matrix exhibits a higher effective rank and a substantially smaller condition number, confirming that the DDPA–RCI approach offers not only higher angular resolution under the same aperture but also superior numerical stability and robustness to noise.

3. Design of the Proposed Antenna

Antenna Geometry and Operating Principle

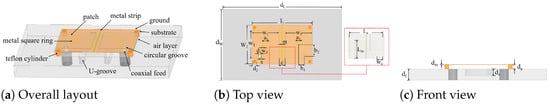

To achieve frequency diversity, the geometry of the DDPA designed in this paper is illustrated in Figure 3. The front view is shown in Figure 3c, where an air layer of thickness is placed between a Rogers 4003 dielectric substrate of thickness (relative permittivity of 3.55 and loss tangent of 0.0027) and a ground plane of thickness . A U-shaped slot of thickness d is etched from the interface between the ground plane and the air layer.

Figure 3.

Geometric structure of the antenna: (a) overall layout; (b) top view; (c) front view.

The top view is shown in Figure 3b. Each square patch has a width of and is fed at distances (along the x-axis) and (along the y-axis) from the patch center. The feed probe has a diameter of , and its top is flush with the metal patch, which acts as a circular metallic element of the same diameter . A slot of width s is cut around the feed probe. The distance between the two square patches is , and a metal strip of length and width m connects the two patches.

On the back side of the dielectric substrate, beneath each patch, there is a square metal frame of width . Four Teflon posts of diameter are positioned around the perimeter of the dielectric plate to provide mechanical support. The dielectric plate measures , whereas the ground plane measures . The U-shaped slot in the ground plane, highlighted by the red dashed box in Figure 3, consists of two side slots of length and width and a central slot of length and width . The optimized design parameters are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Antenna parameter.

To achieve frequency diversity, thereby mitigating multipath interference and increasing the randomness of the transmitted signal, a slot of width s is etched at the feed port, as shown in Figure 3. Etching the slot is equivalent to locally extending the current path, thereby generating multiple resonant modes. The main resonance frequency is determined by the overall antenna dimensions, whereas the additional resonance frequencies are governed by the slot length and the variation in the electric field around the slot.

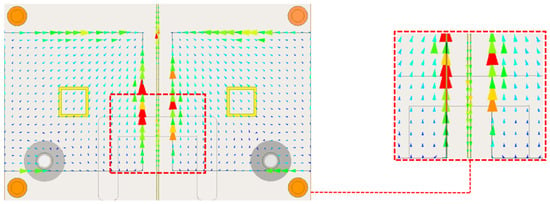

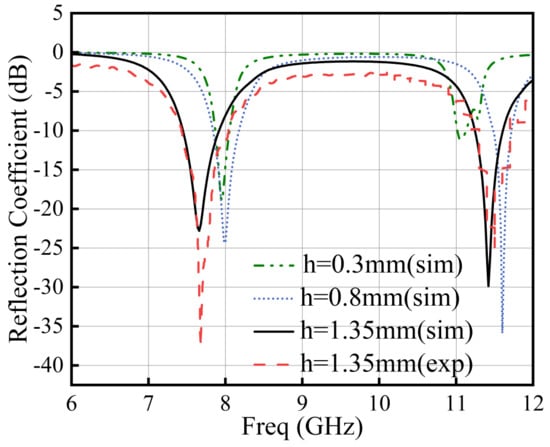

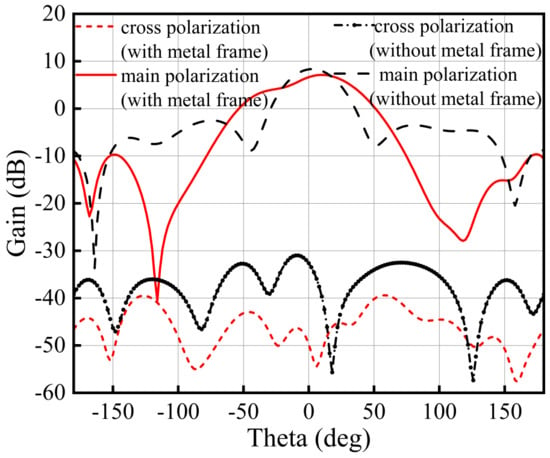

In addition, since the dielectric constant of the air layer is and that of the Rogers RO4003 substrate is 3.55, the introduction of the air layer effectively reduces the overall equivalent dielectric constant. This reduction smooths the input impedance curve of the antenna and improves its impedance bandwidth. In the proposed structure, the two signals from the dual-phase centers are designed to be orthogonal in polarization, as illustrated in Figure 4. The current on the upper-left patch flows at an angle of 45° to the right, whereas that on the upper-right patch flows at an angle of 45° to the left, forming an orthogonal polarization with a 90° separation between them. The antenna was simulated using *Ansys HFSS* software, and the results are presented in Figure 5. As the height of the air layer increases from 0.3 mm to 1.35 mm, the bandwidths of the two operating frequency bands increase by 430 MHz and 450 MHz. Consequently, two operating bands are obtained, centered at 7.3 GHz and 11.2 GHz, with bandwidths of 610 MHz and 580 MHz, respectively. The red dashed line in Figure 5 represents the measured reflection coefficient. The experimental results show good agreement with the simulations, confirming the accuracy of the antenna fabrication and design. To satisfy the spatial and temporal independence requirements of the emitted signals in RCI, it is essential to minimize the mutual interference between the signals radiated by the two phase centers while simultaneously acquiring more target information. A metal frame with a width of 0.125 mm is placed on the back of each patch. This frame acts as a reflector, redirecting the backward electromagnetic waves toward the front of the antenna. As a result, the radiated energy becomes more concentrated along the main radiation direction, reducing energy scattering in the cross-polarization direction and thereby suppressing cross-polarization components. The black solid line in Figure 6 represents the main-polarization radiation without the metal frame, with a gain of 8.53 dB, whereas the black dashed line shows the orthogonally polarized radiation without the frame, with a gain of 40.93 dB. The red solid line in Figure 6 corresponds to the main-polarization radiation with the metal frame. Since the electromagnetic wave reflected from the metallic frame also contributes to the co-polarization component, the overall radiation gain decreases by 1.54 dB (from 8.53 dB to 6.99 dB), whereas cross-polarization isolation improves by 15.46 dB, reaching 50.93 dB.

Figure 4.

Current distribution on the metal strip. (The arrows indicate the direction of the current flow).

Figure 5.

Reflection coefficient of the antenna element.

Figure 6.

Simulation results of main and orthogonal polarization.

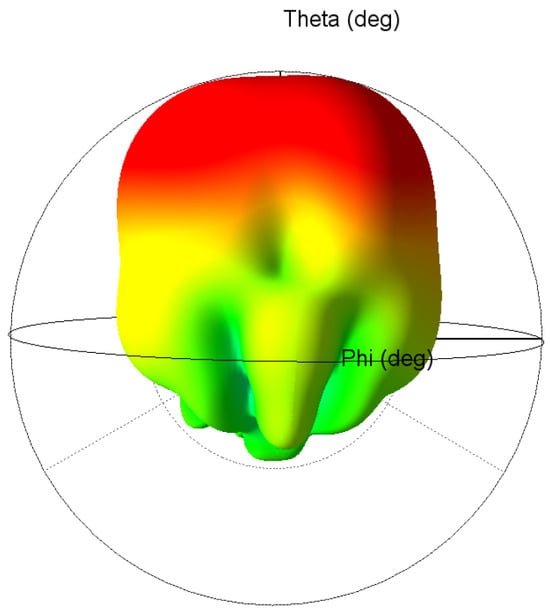

The gain of the DDPA was measured in a microwave anechoic chamber. The measured peak gain of the DDPA is 6.7 dB, with a cross-polarization isolation of 47.55 dB. The experimental results are in good agreement with the simulations, confirming the effectiveness of the proposed design. Under these conditions, mutual interference between the two polarized signals is minimized. Consequently, when one feed port is used for the main polarization, the other corresponds to the cross polarization. In Figure 6, the main and cross-polarizations represent the horizontal and vertical polarizations, respectively.Since the two patch antennas in the DDPA are mirror-symmetric, each feed port excites a different polarization. When the horizontal (vertical) polarization port is excited, the main polarization in Figure 6 corresponds to the horizontal (vertical) polarization, while the cross-polarization corresponds to the vertical (horizontal) polarization. The beamwidth is approximately , and the sidelobe level is about . The three-dimensional radiation pattern of the DDPA is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Three-dimensional radiation pattern.

Secondly, to minimize inter-signal crosstalk and mitigate radiation pattern distortion, which could otherwise degrade the achievable imaging resolution, a metallic strip of length and width m is embedded within the proposed antenna configuration. The presence of this metallic element partially confines the surface current distribution, effectively reducing the mutual electromagnetic coupling between the fields excited by distinct feed points.

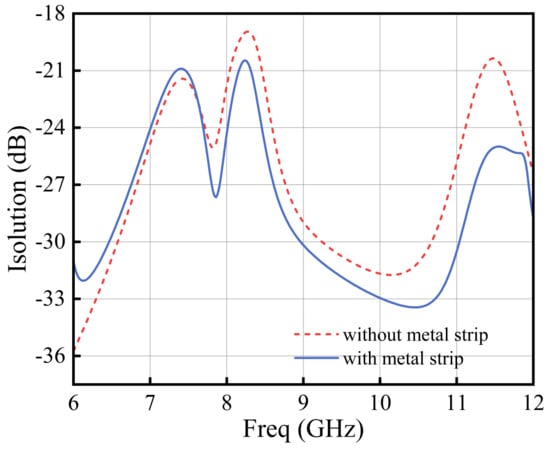

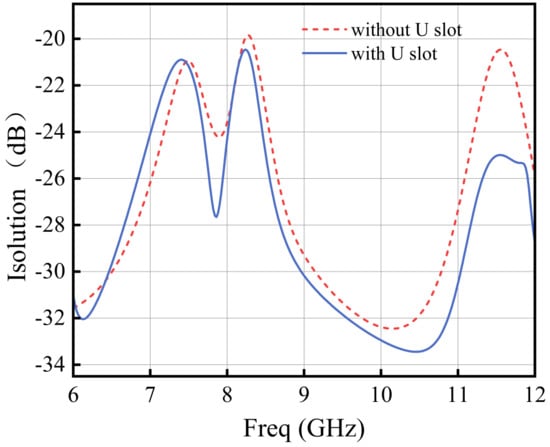

In addition, due to multimode resonance, the induced current coupled to the metal strip exhibits two opposite current directions. The current flowing in the lower portion of the patch is opposite to that at the patch edge, resulting in partial cancellation between the electromagnetic fields generated by the metal strip and those produced by the patch. This effect slightly reduces the isolation between the two feed ports, as illustrated in Figure 8, where the patch spacing is 3 mm (). The simulated results shown in Figure 8 confirm that the overall isolation performance is improved after introducing the metal strip.

Figure 8.

Port isolation with or without metal strip.

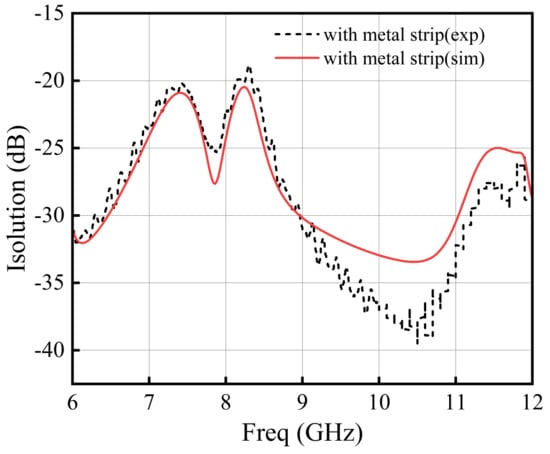

To further improve the isolation, a U-shaped slot was etched into the ground plane. The introduction of an air layer reduces the propagation of the electromagnetic field within the dielectric substrate. When electromagnetic waves propagate from a medium with a higher dielectric constant to an air layer with a lower dielectric constant, stronger reflections and higher impedance occur. The U-shaped slot causes the electric field to concentrate locally near the slot edges, thereby increasing the impedance. As a result, the electromagnetic waves traveling from one patch to the other are more strongly reflected, which reduces mutual coupling. In addition, the U-shaped slot alters the current distribution between the ground plane and the dielectric substrate, introducing diffraction and scattering effects along the slot boundaries. This modification lengthens and redistributes the current paths, thereby reducing the direct coupling of electromagnetic energy between the two feed ports, as illustrated in Figure 9. Figure 10 presents a comparison of the simulated and measured port isolations, showing good agreement between the two results and confirming the effectiveness of the proposed isolation design.

Figure 9.

Port isolation with or without U-shaped slot.

Figure 10.

Comparison of port isolation between simulated and experimental results.

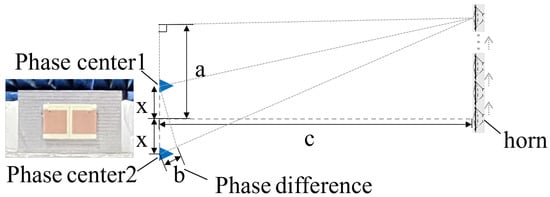

Since the proposed dual-phase-center antenna is intended for RCI applications, the simulation verifies that the dual-phase centers play a crucial role in imaging performance. Therefore, the distance between the two phase centers of the designed antenna was measured to experimentally confirm the existence of the dual-phase-center configuration. As shown in Figure 11, the antenna element was placed on a turntable inside an anechoic chamber, while a horn antenna was used as a far-field signal source to transmit plane waves toward the designed antenna. By continuously moving the horn antenna and recording the corresponding displacement at each position, the effective distance between the two phase centers was determined.

Figure 11.

Schematic diagram of phase center calculations.

The phase difference (in degrees) was recorded each time using a vector network analyzer inside the anechoic chamber, and the corresponding phase difference b (in centimeters) between the two phase centers after each movement was calculated according to (34). The experimental setup is illustrated in Figure 11. The blue triangles represent the two phase centers. Here, a denotes the displacement of the horn antenna, c represents the horizontal distance from the midpoint of the line connecting the two phase centers to the horn motion plane, and b is the phase difference measured between the two ports.

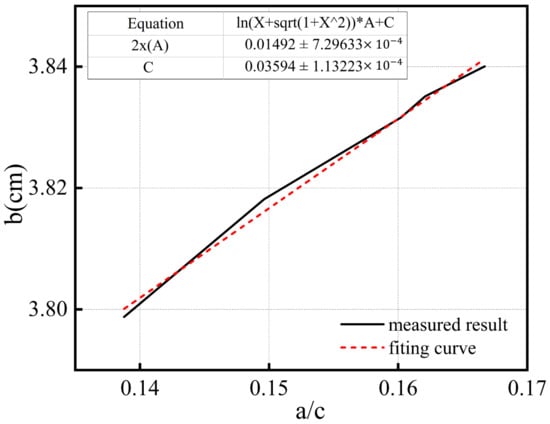

Integrating the first equation below gives the second equation:

The result of the calculation is (38):

According to (38) and the measured data from 25 samples, the original data (solid black line) and the fitted results (red dashed line) are shown in Figure 12. The calculated distance between the two phase centers, denoted as , is 0.01492 m, with a measurement error of less than 0.000729 m, considering the effects of turntable positioning accuracy, horn antenna movement error, and system phase drift. These results confirm the existence of two distinct phase centers. All validation reported in this paper is based on controlled indoor experiments on a laboratory testbed, and no field or airborne deployment has yet been conducted.

Figure 12.

Result diagram of data fitting.

4. Joint Simulation of Antenna and Imaging Algorithm

The analysis presented in Section 2 is validated through an RCI simulation of a static target. The antenna designed in Section 3 is employed in the imaging scene, and the basic simulation parameters are listed in Table 2. The simulated imaging configuration is illustrated in Figure 13. The simulations were carried out on a computing platform equipped with an Intel Core i7-10700 CPU and an NVIDIA RTX 3080 GPU. Under this hardware configuration, the runtime of the imaging simulation is approximately 7 s. An antenna array consisting of four DDPAs is used as the transmitting source, while a single DDPA serves as the receiver. The spacing between adjacent DDPAs in the transmitting array is half a wavelength (0.0195 m). The distance between the receiver and the transmitting array is 0.65 m, and the separation between the centers of the imaging plane and the transmitting array is 0.8 m. The imaging plane has a size of and is divided into 144 grids (). The imaging area is fully within the main lobe width, and the gain variation is less than 2 dB. Therefore, in the imaging simulation, the antenna pattern is modeled as uniform within the main lobe, while the gain outside this region is attenuated according to the measured sidelobe level of −20 dB.

Table 2.

Radar parameter settings for RCI.

Figure 13.

Schematic diagram of a scene using DDPA for imaging.

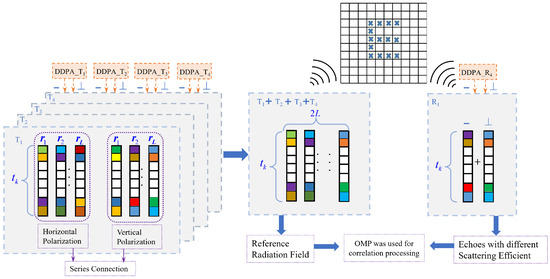

Each DDPA has two feed ports, indicated by the orange arrows in the Figure 14, and each port corresponds to a specific polarization. The symbol “−” denotes horizontal polarization, whereas “⊥” represents vertical polarization. As illustrated in the Figure 14, each orange arrow indicates a single-polarization random signal. The results from the four antennas correspond to the four gray boxes, which are directly superimposed in the imaging process. Each small grid in the imaging area corresponds to a scattering unit denoted as .

Figure 14.

Flowchart of DDPA-RCI imaging principle.

Since the four DDPAs transmit four independent random signals, the signals received at each grid point are random. The resulting reference radiation field corresponds to the purple dashed boxes, each representing a single polarization mode. Owing to the relatively weak responses of the cross-polarized channels (horizontal to vertical and vertical to horizontal), only the co-polarized components ( and ) are utilized in the imaging analysis. By concatenating the horizontal and vertical polarization channels, a measurement matrix with columns and rows is constructed. DDPA_R1 acts as the receiver and combines the horizontal and vertical polarization signals to form an echo dataset with rows and one column. The echo data are then correlated with the reference matrix to produce the final reconstructed image.

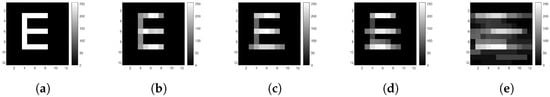

At an SNR of 20 dB, Figure 15 presents a comparative analysis of different imaging configurations. (a) shows the original image as a reference, where all details are clearly visible. (b) illustrates the imaging result obtained with the dual-frequency, dual-polarization, and dual-phase-center (DD) configuration, which delivers the highest imaging quality characterized by sharp edges, well-preserved fine structures, and substantially suppressed noise, thereby demonstrating the pronounced performance enhancement achieved by this configuration. In contrast, (c) displays the result for the dual-frequency, single-polarization, and single-phase-center (DS) configuration. Although the use of dual-frequency improves spectral diversity, the absence of multiple polarizations and phase centers leads to noticeable detail loss, particularly in low-contrast regions, where blurring and noise are evident. (d) shows the result for the single-frequency, dual-polarization, and dual-phase-center (SD) configuration. While dual polarization and dual-phase centers improve image clarity compared with DS, the single-frequency constraint limits performance, resulting in partially blurred edges and residual noise. Finally, (e) illustrates the single-frequency, single-polarization, and single-phase-center (SS) configuration, which yields the poorest image quality, characterized by severe blurring, substantial detail loss, and strong noise interference.

Figure 15.

Imaging results with a SNR of 20 dB. (a) Original image. (b) DD. (c) DS. (d) SD. (e) SS.

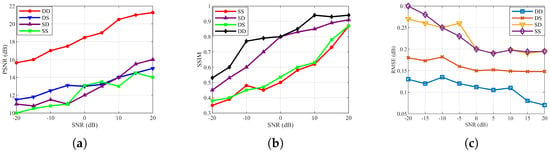

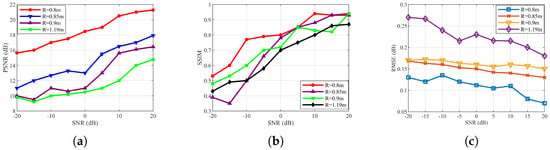

As shown in Figure 16, the imaging performance of different antenna configurations varies distinctly across the three quantitative metrics: PSNR, SSIM, and RMSE. In general, all configurations exhibit performance improvements as the SNR increases, with the DD configuration consistently demonstrating the best overall results. Specifically, in Figure 16a, DD achieves the highest PSNR, exceeding 20 in the high-SNR region, which indicates superior signal fidelity and strong noise suppression capability. In contrast, the SS configuration yields the lowest PSNR, reflecting its limited imaging quality. As illustrated in Figure 16b, DD maintains the highest SSIM value, approaching 0.9, which shows improved structural preservation compared with the other configurations. The RMSE results in Figure 16c further confirm this trend, where DD exhibits the lowest and most rapidly decreasing error, suggesting enhanced numerical stability and reconstruction accuracy. In summary, the DD configuration provides the highest imaging fidelity, stability, and robustness, whereas low-dimensional configurations such as SS perform relatively poorly under noisy conditions.

Figure 16.

Comparison of imaging quality under different antenna configurations. (a) PSNR. (b) SSIM. (c) RMSE.

To quantify the differences in imaging performance across different antenna configurations, the scattering coefficients of all grid points within the imaging area are extracted and used to compute the RIF, as defined in (39). Specifically, represents the scattering coefficient of the p-th grid point among the P target grid points, while denotes the scattering coefficient of the q-th grid point among the Q non-target grid points. The RIF is obtained by first computing, for each target point, a weighted average of its increment relative to all non-target points, and then performing a second weighted average over all target points:

where , . The RIF values for the imaging results shown in (b) to (e) of Figure 15 are calculated with . The results are presented in Table 3. The resolution improvement factor for the dual-frequency, dual-polarization, dual-phase-center configuration is the highest, being 2.5 times that of the single-frequency, single-polarization, single-phase-center configuration.

Table 3.

RIF comparison results across different scenarios and algorithms.

As shown in Figure 17 and Figure 18, imaging quality depends jointly on imaging distance R and the SNR. When , the reconstructed letter “E” exhibits clear strokes and high contrast. As the imaging distance increases to , , and , the image edges gradually become blurred, blocky artifacts appear, and fine structural details and hierarchical information are lost.

Figure 17.

Imaging results at different imaging distances. (a) Original imaging. (b) m. (c) m. (d) m. (e) m.

Figure 18.

Comparison of imaging quality at different focusing distances. (a) PSNR. (b) SSIM. (c) RMSE.

The quantitative evaluation further confirms this trend. PSNR increases monotonically with SNR and maintains a clear separation among different imaging distances. Specifically, the case of achieves the highest PSNR (exceeding 20 dB in the high-SNR region), followed by and , while yields the lowest PSNR (slightly above 10 dB in the low-SNR region). This indicates that a shorter imaging distance mitigates noise amplification and distortion accumulation.

Similarly, SSIM rises from approximately 0.3–0.5 to around 0.9 as SNR increases. Among all cases, and exhibit higher structural similarity in the high-SNR region, suggesting the better preservation of geometric structure and grayscale consistency. Conversely, RMSE exhibits the opposite trend, decreasing as SNR increases. The curve corresponding to remains the lowest, whereas shows the highest RMSE, indicating that longer imaging distances cause stronger pixel-level deviations due to noise and model mismatch.

In summary, both qualitative and quantitative assessments indicate that, for a given SNR, shorter imaging distances, especially , yield higher imaging fidelity and greater reconstruction stability. At low SNR levels, the performance gap among different distances becomes more pronounced, whereas in the high-SNR region, the ranking remains consistent though the overall image quality improves. Simultaneously, the RIF results were calculated for scenarios at different distances. The results are shown in Table 3. As the distance increases, the RIF value gradually decreases.

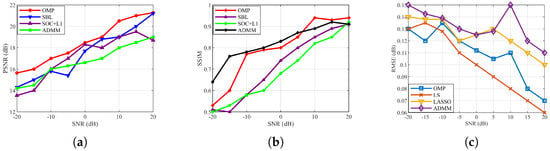

As shown in Figure 19 and Figure 20, different reconstruction methods exhibit consistent trends in both visual performance and quantitative metrics, though with varying degrees of improvement. Subjectively, the image reconstructed using the orthogonal matching pursuit () method displays the most complete and high-contrast letter “E,” characterized by sharp edges and smooth texture transitions. OMP achieves fast convergence when the sparsity and low-coherence conditions are met. The sparse Bayesian learning () method recovers the overall outline but produces an over-smoothed and slightly blurred image with lower contrast in fine details. The second-order correlation plus -norm () method, influenced by sparse regularization, introduces blocky or stair-step artifacts and discontinuities in fine structures. The alternating direction method of multipliers () achieves the best noise suppression, yielding fewer speckles and better structural preservation, although slight over-smoothing remains noticeable at very low SNR levels.

Figure 19.

Imaging results at different methods. (a) Original imaging. (b) OMP. (c) SBL. (d) SOC + L1. (e) ADMM.

Figure 20.

Comparison of imaging quality with respect to different methods. (a) PSNR. (b) SSIM. (c) RMSE.

The quantitative results further corroborate these observations. PSNR increases monotonically with SNR and maintains a clear separation among the methods. The and curves consistently occupy the top tier, the curve lies in the middle, and the curve performs the worst. At high SNR, and exhibit the most significant advantage, indicating stronger robustness against noise amplification and model mismatch. SSIM rises from approximately 0.3–0.5 to nearly 0.9 as SNR increases, following a similar performance hierarchy: and maintain higher structural similarity in the medium-to-high SNR range, demonstrating the superior preservation of geometric structure and grayscale consistency, while achieves moderate results and performs the weakest due to its blocky artifacts. Conversely, RMSE exhibits the opposite trend—decreasing as SNR increases. Among all methods, and achieve the lowest and fastest-converging error curves, remains intermediate, and yields the highest RMSE, indicating larger pixel-level deviations and localized distortions.

Overall, both subjective and objective evaluations indicate that and achieve the highest performance in terms of fidelity and stability. At low SNR levels, the exhibits superior robustness due to its constrained iterative optimization framework. As SNR increases, the advantage of in accurate atom selection becomes more pronounced, making its performance comparable to that of the .

The method offers a reasonable trade-off between computational complexity and stability but struggles to preserve fine details and contrast. In contrast, the method fails to effectively balance noise suppression and detail preservation under the given conditions, resulting in the weakest overall performance. In summary, and are the most suitable approaches for achieving high-fidelity and stable imaging, while can serve as a reliable baseline. The method, however, requires further parameter optimization or model refinement to mitigate block artifacts and detail loss. The RIF calculation results for different algorithms are shown in Table 3. The RIF values for different algorithms are reported in Table 3. The RIF value for is slightly higher than that for , whereas the values for and are comparable.

Table 4 summarizes a comparison between the imaging results of the proposed method and those reported for other and conformal radar systems. For consistency, the angular separation between the two closest resolvable targets is computed for each method.

Table 4.

Comparison of imaging results.

Following the small-angle approximation described in [20], when the target range is large and the spacing between adjacent targets is small, the angular resolution can be approximated as (40):

The conventional diffraction-limited angular resolution is also given by (41):

As shown in Table 4, denotes the radar operating frequency, B is the system bandwidth, D is the transmitting array aperture, represents the angular resolution achieved by each method, is the traditional angular resolution under the same radar parameters, and M denotes the improvement factor of angular resolution compared with the conventional system. The last two columns of Table 4 list the reconstruction algorithm employed and its corresponding computational complexity (CC).

As shown in Table 4, denotes the radar operating frequency, B denotes the system bandwidth, D denotes the transmitting array aperture, denotes the angular resolution achieved by each method, denotes the traditional angular resolution under the same radar parameters, and M denotes the improvement factor in angular resolution relative to the conventional system. The hybrid method “SOC + ” combines statistical correlation imaging with -norm sparse optimization to further enhance resolution.

The CC expressions listed in the table are written in big- notation, where denotes the number of iterative steps, denotes the number of transmitting antennas, K denotes the number of sampling points, L denotes the number of discretized imaging grids, and denotes the number of operating modes. For instance, the ADMM algorithm exhibits a complexity of due to iterative matrix updates in each optimization step, whereas SOCM has a complexity of , dominated by second-order correlation accumulation across transmit–receive pairs. The SBL approach, owing to covariance matrix inversion at every iteration, involves a cubic term . In contrast, the proposed OMP-based dual-frequency, dual-polarization, and dual-phase-center coincidence imaging method achieves a computational complexity of .

Although the inclusion of dual frequencies, dual polarizations, and dual-phase centers introduces an approximately fourfold increase in computational load, this growth remains strictly linear with respect to the key variables () and is therefore computationally manageable. In theoretical terms, the scaling implies that the additional signal diversity contributes only a constant multiplicative factor rather than an order-of-magnitude increase (e.g., quadratic or cubic). Practically, this means that while the total computation increases moderately, the multi-frequency and multi-polarization diversity significantly enhance the rank and conditioning of the reference matrix, thereby improving imaging resolution and numerical stability. Notably, the proposed method achieves an angular resolution of without requiring ultra-wide bandwidths or large physical apertures, corresponding to a fold improvement over the conventional diffraction limit. This demonstrates that the proposed dual-frequency, dual-polarization, and dual-phase-center design delivers substantial resolution gains while maintaining near-linear computational scalability—making it both computationally efficient and physically realizable.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents a stochastic-based RCI framework employing DDPA arrays for achieving super-resolution imaging. The theoretical principle of RCI was first analyzed to identify the key factors influencing imaging resolution. Based on this analysis, a dual-frequency antenna structure with dual-phase centers was proposed, where orthogonal polarizations are used to represent different phase centers. Simulations and controlled indoor measurements demonstrate the existence of dual-phase centers, indicating that random signals are radiated from distinct antenna locations under the tested conditions. Further simulations involving four transmitting antennas show that the proposed DDPA configuration achieves more than a 2.5-fold improvement in RIF compared with a conventional antenna structure. When the SNR is higher than 20 dB, the RCI reconstruction attains an approximately fifteen-fold enhancement in angular resolution in these simulated and indoor scenarios. In summary, the proposed dual-frequency, dual-polarization, and dual-phase-center antenna design provides a new perspective for radar imaging and shows the potential for substantial resolution improvement without increasing physical aperture size. Future work will extend the proposed DDPA–RCI framework to full two-dimensional complex scenes, incorporate two-dimensional error maps for enhanced characterization of spatial errors, and further investigate its robustness under real-field deployment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-Y.W. and C.M.; methodology, S.-Y.W.; software, S.-Y.W.; validation, S.-Y.W., C.M. and S.-S.Q.; formal analysis, S.-Y.W.; investigation, S.-Y.W.; resources, W.W.; data curation, S.-Y.W.; writing—original draft preparation, S.-Y.W.; writing—review and editing, C.M. and S.-S.Q.; visualization, S.-Y.W.; supervision, W.W.; project administration, W.W.; funding acquisition, S.-S.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62271257, Grant 62301254, and Grant 62171464 and in part by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation under Grant 2023M731700.

Data Availability Statement

The MATLAB R2022a simulation codes, Ansys HFSS 2024R1 antenna models, and key parameter configurations used in this study will be provided upon request for academic and non-commercial research purposes without additional restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pittman, T.B.; Shih, Y.H.; Strekalov, D.V.; Sergienko, A.V. Optical imaging by means of two-photon quantum entanglement. Phys. Rev. A 1995, 52, R3429–R3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatti, A.; Brambilla, E.; Bache, M.; Lugiato, L.A. Ghost imaging with thermal light: Comparing entanglement and classical correlation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 93, 093602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erkmen, B.I.; Shapiro, J.H. Ghost imaging: From quantum to classical to computational. Adv. Opt. Photon. 2010, 2, 405–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafai, L.; Sharma, S.K.; Balaji, B.; Damini, A.; Haslam, G. Multiple phase center performance of reflector antennas using a dual mode horn. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2006, 54, 3407–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Zhao, M.; Dong, X.; Shi, H.; Lu, R.; Chen, X.; Zhang, A. Differential coincidence imaging with frequency diverse aperture. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2018, 17, 964–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Zhu, S.; Fromenteze, T.; Abbasi, M.A.B.; Chen, X.; Huang, Y.; Yurduseven, O. Dual-polarized frequency-diverse metaimager for computational polarimetric imaging. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2024, 72, 5479–5488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Liu, H.; Cheng, Y.; Xu, K.; Liu, K.; Yang, Y. Microwave coincidence imaging with phase-coded stochastic radiation field. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Zhou, Y.; He, Y.; Yu, X.; Zhang, F.; Pan, S. Photonics-based MIMO radar with broadband digital coincidence imaging. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2024, 72, 6996–7003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, M.; Nian, Y.; Zhao, M.; Chen, X.; Yi, J. Synthetic beam scanning and super-resolution coincidence imaging based on randomly excited antenna array. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 2002414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi-Manesh, H.; Zhang, G. High-isolation, low cross-polarization, dual-polarization, hybrid feed microstrip patch array antenna for MPAR application. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2018, 66, 2326–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, S.L.; Wu, G.; Wu, Z.; Wang, P.; Li, Y. Adaptive polarization modulation for subarray-based monopulse radar angular superresolution. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2025, 61, 14262–14275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Liu, T.; Shan, J.; Xu, X. Calibration of polarimetric millimeter MIMO radar for near-field ultrawideband imaging measurement. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 8500914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhou, X.; Xu, X.; Qin, Y.; Wang, H. Radar coincidence imaging with stochastic frequency modulated array. IEEE J. Sel. Topics Signal Process. 2017, 11, 414–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Zhang, F.; Pan, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Y. Adaptive super resolution array radar imaging based on sparse reconstruction and effective rank theory. In Proceedings of the 24th International Radar Symposium (IRS), Berlin, Germany, 24–26 May 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhu, S.; Chen, X.; Zhang, A.; Xu, Z. Polarization-sensitive-metasurface-based microwave computational ghost imaging. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2023, 56, 125002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, Q.; Wang, H. Microwave coincidence imaging based on attributed scattering model. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2022, 29, 1694–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Zhang, A.; Xu, Z.; Dong, X. Radar coincidence imaging with random microwave source. IEEE Antennas Wireless Propag. Lett. 2015, 14, 1239–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, S.L.; Wu, G.; Liu, K.; Wu, Z.; Wang, P.; Li, Y. Polarization modulation spectral approach for multichannel radar forward-looking superresolution imaging. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2025, 61, 14764–14781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, N.; Zhu, S.; Chen, X.-M.; Zhao, M.; Kishk, A.A. Resolution analysis of coincidence imaging based on OAM beams with equal divergence angle. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2023, 71, 2891–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookner, E. Radar signal processing and adaptive systems [Book Review]. IEEE Aerosp. Electron. Syst. Mag. 2000, 15, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).