1. Introduction

Remote sensing change detection (RSCD), serving as a fundamental technology in Earth observation, detects surface changes by analyzing multi-temporal remote sensing imagery. Its applications are critically important across diverse fields, ranging from monitoring urban expansion and assessing ecological environments to supporting disaster emergency response [

1]. The recent progress in high-resolution satellite and unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technologies has greatly facilitated the collection of large-scale multi-source remote sensing data. Nevertheless, change detection remains challenging due to complexities such as diverse terrain scenes, varying imaging conditions (e.g., illumination and seasonality), and targets of different sizes. These issues often lead to false alarms, missed detections of small objects, and limited capability in capturing long-range contextual relationships [

2].

While conventional change detection techniques depend on pixel-level statistics or feature engineering, such as image differencing and principal component analysis, their underlying principles, though well-established, are often inadequate for semantic understanding in complex scenes. The advancement of deep learning has catalyzed technological innovations in this field, and methods based on CNNs have substantially enhanced detection accuracy by leveraging end-to-end learning frameworks. The Siamese network, a prominent architecture, utilizes shared-weight branches to extract features from bi-temporal images. Change detection is subsequently performed by comparing or integrating the derived feature representations [

3]. Nevertheless, the inherent locality of convolutional operations in CNNs restricts their ability to model global spatio-temporal context. This limitation can result in the misclassification of spectral differences as genuine changes in heterogeneous regions (e.g., urban areas or vegetated terrain), or cause the model to overlook long-range change dependencies due to constrained receptive fields.

In recent years, the breakthroughs of the transformer architecture [

4] in computer vision have opened up new avenues for remote sensing change detection. Its self-attention mechanism captures global dependencies among pixels, effectively modeling long-range semantic relationships and thereby mitigating the inherent limitations of CNNs. For instance, hybrid architectures that integrate transformers with CNNs (e.g., SUT [

5], BIT [

6]) incorporate spatio-temporal feature enhancement modules to suppress false alarms in complex scenarios. On the other hand, pure Transformer-based architectures such as ChangeFormer [

7] and SwinSUNet [

8] enhance detection robustness by leveraging hierarchical feature extraction and fusion. These methods have delivered state-of-the-art results on widely used benchmarks including LEVIR-CD [

9] and WHU-CD [

10], highlighting the promising capability of transformers in RSCD.

However, the following research questions are still exist in RSCD:

(1) How can we effectively distinguish genuine changes from pseudo-changes caused by spectral variations and semantic complexity in high-resolution remote sensing imagery?

(2) How can we enhance the detection of small objects and preserve fine-grained details while maintaining computational efficiency?

(3) How can we design a lightweight yet powerful change detection model that is suitable for resource-constrained environments without sacrificing accuracy?

To tackle these questions, we introduce a hybrid change detection architecture that integrates CNN and Transformer mechanisms. The key contributions of our work are as follows:

(1) A Hybrid CNN-Transformer Architecture for Robust Change Detection, we propose a novel hybrid framework that synergistically combines the local feature extraction capability of CNNs with the global contextual modeling strength of Transformers. This design effectively mitigates false alarms caused by spectral variations and enhances the detection of long-range dependencies in complex remote sensing scenes.

(2) Spectral-Attention Cooperative Encoder for Local-Global Feature Fusion, we design a cooperative encoder comprising a Spectral layer and an Attention layer. The Spectral layer captures high-frequency components (e.g., edges and textures) in the Fourier domain, while the Attention layer models global semantic dependencies. This dual-path mechanism ensures complementary local-global feature representation.

(3) DyT Module for Enhanced Training Stability and Efficiency, we replace traditional normalization layers with a learnable DyT module, which adaptively adjusts activation thresholds. This innovation improves training stability and convergence speed while reducing computational overhead, making the model suitable for resource-constrained environments.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews related work.

Section 3 details the proposed methodology.

Section 4 presents experimental results and analysis.

Section 5 presents the discussion and suggests future research directions.

2. Related Work

2.1. Traditional CD Algorithms

Early CD techniques are broadly categorized into three groups: algebra-based, image transformation-based, and image classification-based approaches. Algebra-based CD algorithms operate directly on pixel values through arithmetic operations to identify changed regions. Typical techniques include image differencing (e.g., Change Vector Analysis, CVA), image ratioing, and regression analysis, which produce difference images. These are then combined with thresholding algorithms such as OTSU to extract change areas [

11]. A major drawback of these methods is their high sensitivity to radiometric differences and noise. Image transformation-based methods involve mathematical transforms applied to the image data to project it into a new feature space where change information is enhanced. Commonly used techniques include Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [

12], Kauth-Thomas transformation (K-T) [

13], and Canonical Correlation Analysis [

14]. While these approaches can reduce data dimensionality and highlight major change components, their performance remains limited in complex scenarios. This category of methods identifies changes by analyzing discrepancies in the thematic maps produced by classifying multi-temporal images separately. A typical strategy is post-classification comparison, where images from two time points are classified separately, and the results are compared to identify changes in type and location [

15]. This method can provide categorical change information and reduce impacts from atmospheric conditions, but its accuracy heavily depends on classification performance and requires a sufficient number of high-quality training samples. Alternatively, simultaneous classification of multi-temporal images integrates temporal data into a single feature set, treating time as an additional dimension. Although this approach can better capture temporal change patterns, it involves processing large volumes of data and suffers from high computational complexity.

2.2. CD Methods with CNNs

Recently, deep learning techniques have achieved remarkable progress in RSCD. Unlike conventional approaches, deep learning methods are capable of automatically learning hierarchical feature representations from data without manual feature engineering. This data-driven characteristic renders them highly effective in capturing the complex and nuanced patterns present in high-resolution remote sensing imagery. Among deep learning architectures, the Siamese network has been extensively adopted for change detection tasks. It consists of two weight-sharing subnetworks that process bi-temporal images separately. Features extracted from both branches are compared to compute differences, and a classifier is then used to identify changed regions. Commonly used backbone networks include U-Net [

16], FCN [

17], and densely connected feature fusion networks [

18], among others. U-Net, with its classic encoder–decoder design, has been widely used in semantic segmentation and serves as a foundational structure for many change detection models-for instance, Siamese_AUNet [

19]. Fully Convolutional Networks (FCN), which utilize convolutional layers in place of fully connected ones, support inputs of arbitrary size and generate corresponding spatial outputs, making them suitable for pixel-level prediction tasks. Numerous enhancements have been integrated into FCN-based approaches, including attention modules and multi-scale fusion mechanisms, to improve detection performance. To mitigate the loss of spatial details caused by downsampling, Pan et al. introduced a change detection method employing dense feature fusion [

20]. Their model uses a Siamese network to extract multi-scale features from image pairs, densely connects and concatenates these features during upsampling with the difference feature map, and incorporates an attention mechanism to refine feature representation.

2.3. Transformer-Based Change Detection Methods

Originally developed for natural language processing, transformer architectures have recently achieved substantial progress in computer vision and remote sensing image analysis. Compared to CNNs, transformers demonstrate a strong capacity for modeling global contextual relationships, thereby offering distinct advantages in capturing long-range dependencies inherent in high-resolution remote sensing images [

21]. Several innovative transformer-based approaches have been proposed for change detection. Reference [

22] introduced a method based on a multi-scale Swin Transformer with deep supervision, which incorporates three key modules: a wider and deeper aggregation module, a multi-scale Swin Transformer-based metric module, and a deep supervision module. In [

23], a dual-branch framework combining CNNs and Transformers was presented, featuring a flow and attention-guided bi-temporal alignment module that captures inter-temporal discrepancies through flow-guided feature alignment and attention mechanisms. To address class imbalance and false alarms in change detection, Reference [

24] proposed a Spatio-Temporal Attention Network with Difference Enhancement (STADE-CDNet). This method includes a Change Detection Difference Module (CDDM) that enhances differential features during training to improve learning capability and mitigate class imbalance, along with a Temporal Memory Module (TMM) for extracting spatio-temporal information.

2.4. Dynamic Activation Functions

Activation functions are pivotal in introducing nonlinearity to deep neural networks. While traditional functions like ReLU and its variants (e.g., Leaky ReLU, PReLU) are widely used, they possess fixed operational forms. Recently, there has been a growing research interest in dynamic or learnable activation functions, which adapt their behavior based on the input data or learned parameters, potentially enhancing representation capacity and training dynamics.

Parametric Activations: The Parametric ReLU (PReLU) [

25] can be seen as an early precedent, which introduces a learnable slope for the negative part. Similarly, the Adaptive Piecewise Linear (APL) unit [

26] offers a more complex, learnable shape.

Search-Based and Composable Activations: Methods like Swish [

27] (and its search-derived variant, Mish [

28]) demonstrated that smoother, non-monotonic functions can often outperform ReLU. Building on this, techniques like ACON [

29] propose to meta-learn the activation function’s form by adaptively switching between linear and nonlinear regimes.

Normalization-Activation Intersection: The relationship between normalization and activation has also been explored. TANH [

30] replaces the affine transformation in Layer Normalization with a tanh-based scaling, highlighting the potential of hyperbolic tangent in stabilizing transformers. Most closely related to our work, ref. [

31] (the foundation of our DyT) directly replaces normalization layers with a learnable, bounded activation (DyT), arguing that normalization layers implicitly learn an S-shaped, tanh-like mapping in deep models. This positions DyT not merely as an activation function but as a unified replacement for normalization-activation pairs.

Our proposed DyT module builds upon and distinguishes itself from this lineage. Unlike PReLU or ACON which modify the core activation within a fixed post-normalization structure, DyT is designed as a direct, plug-in replacement for the normalization layer itself. It leverages the stable, bounded properties of the tanh function but injects adaptability through a learnable scaling factor α and affine parameters (γ, β). This design directly targets the training stability and efficiency challenges inherent in deep Transformer-based CD models, offering a novel perspective on simplifying network architecture while maintaining performance.

Notwithstanding these advances, CD in high-resolution remote sensing images still faces several challenges. Variations in imaging conditions-such as illumination, season, and atmospheric effects-often introduce extensive pseudo-changes, which can obscure genuine changes. Furthermore, deep learning-based methods typically demand substantial computational resources and memory, especially for large images and complex network architectures, hindering their deployment in real-time or resource-constrained scenarios. Additionally, detecting small targets-such as minor constructions and road cracks—remains difficult due to their limited pixel coverage and weak feature representation, often leading to missed or false detections. To address this, this paper proposes a change detection framework that fuses CNN and Transformer. It also introduces DyT to replace normalization layers, significantly improving computational efficiency while maintaining detection accuracy.

3. Methods

3.1. Overall Pipeline

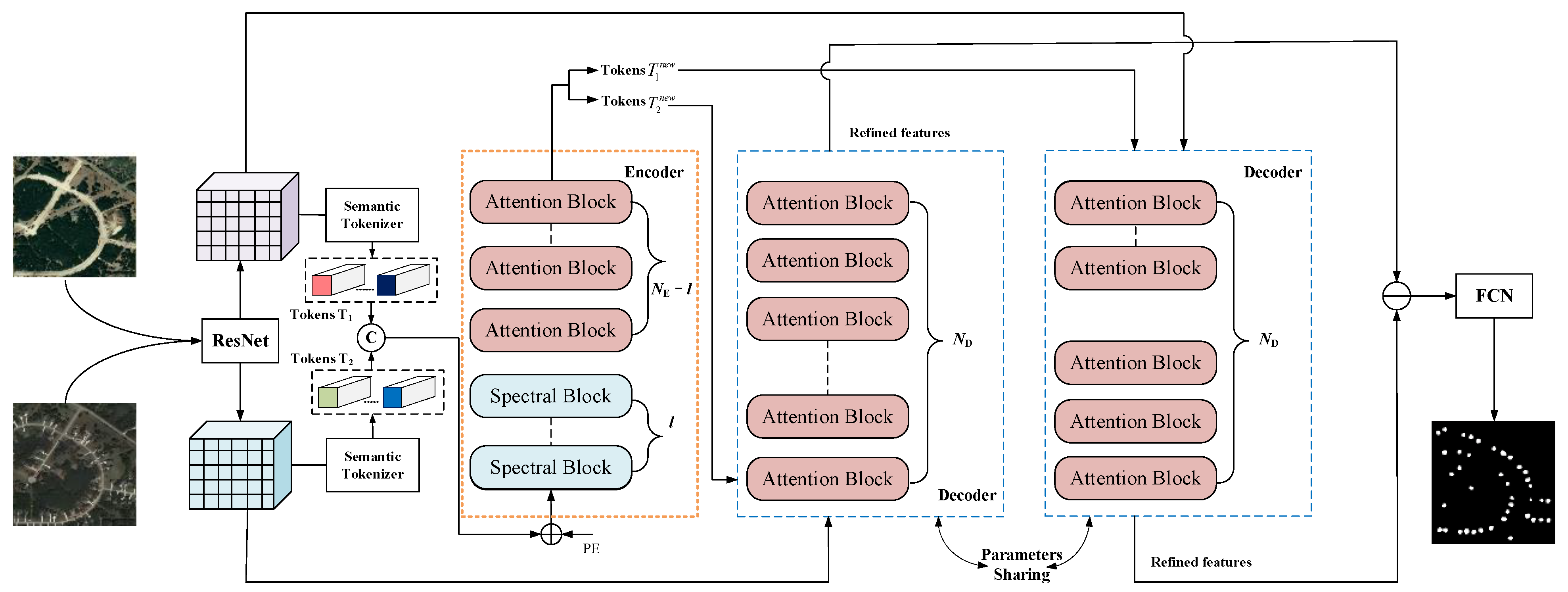

The overall pipeline of the proposed efficient remote sensing image change detection method is illustrated in

Figure 1. Firstly, the input pair of high-resolution optical remote sensing images from two time periods is fed into a ResNet backbone network to extract high-level semantic features, transforming the raw image data into feature maps with semantic information. Subsequently, the Semantic Token Generator processes the feature maps of each time phase. It divides the feature maps into L semantic groups via pointwise convolution and then utilizes the SoftMax function to compute a spatial attention map, which reflects the importance of features at different locations. Finally, through a weighted average operation, a compact set of semantic tokens

is extracted from the feature maps, achieving efficient compression and abstract representation of the image features. The semantic token sets from the two time phases are then concatenated into a unified token set

and fed into the encoder. The encoder consists of a Spectral layer and a Multi-Head Self-Attention layer, which effectively learns optimal transformations for periodic and non-periodic signals, leading to performance improvement. Finally, the context-rich token set processed by the encoder is passed to a Normalization-Free Transformer decoder, which projects the information from the token set back to the pixel space, refining the original pixel-level features. The refined features are processed by a prediction head, which is a lightweight Fully Convolutional Network (FCN) that generates pixel-level change predictions based on feature differences, outputting a change probability map. The final binary change detection result is obtained through threshold segmentation.

3.2. Network Architecture

3.2.1. Semantic Token Generator

The Semantic Token Generator operates based on a spatial attention mechanism and weighted aggregation of image features. For the feature map

of each temporal phase, the process begins by applying pointwise convolution

to partition the features into

L semantic groups. This operation transforms the channel dimensions while preserving the spatial resolution of the feature maps, enabling the extraction of semantic information across different representations. Drawing on the idea of “regional probability aggregation” [

3], the generator employs a spatial attention-based compression mechanism. A spatial attention map

is computed using the SoftMax function σ(·), where each element indicates the importance of the corresponding spatial location within the current semantic group. The SoftMax function normalizes the feature values to a [0, 1] range, providing a normalized measure of feature significance. Finally, a weighted averaging operation is applied to produce the semantic token set. The computation is defined as follows:

where

denotes pointwise convolution,

is the softmax function, and

represents the attention map.

This probabilistic aggregation strategy not only reduces the feature dimensionality (from

to

) but also enhances the token’s ability to represent critical change information-such as building contours-by preserving feature values in high-probability semantic regions [

3,

6].

Subsequently,

and

are concatenated, and positional embeddings are added to retain spatiotemporal positional information:

where

represents the learnable positional embedding parameters, which encode the temporal and spatial semantic positional information of the tokens.

serves as the input to the encoder.

Figure 2a shows the original high-resolution remote sensing image. In contrast,

Figure 2b presents the visualization of the aggregated features from the semantic tokens generated by the proposed Semantic Token Generator. This visualization demonstrates that while fine-grained texture details are lost due to the extreme compression, the most critical discriminative information—specifically, the prominent edges and contours of the buildings—is effectively preserved and highlighted. This confirms the token’s ability to capture essential structural features necessary for accurate change detection.

3.2.2. Encoder

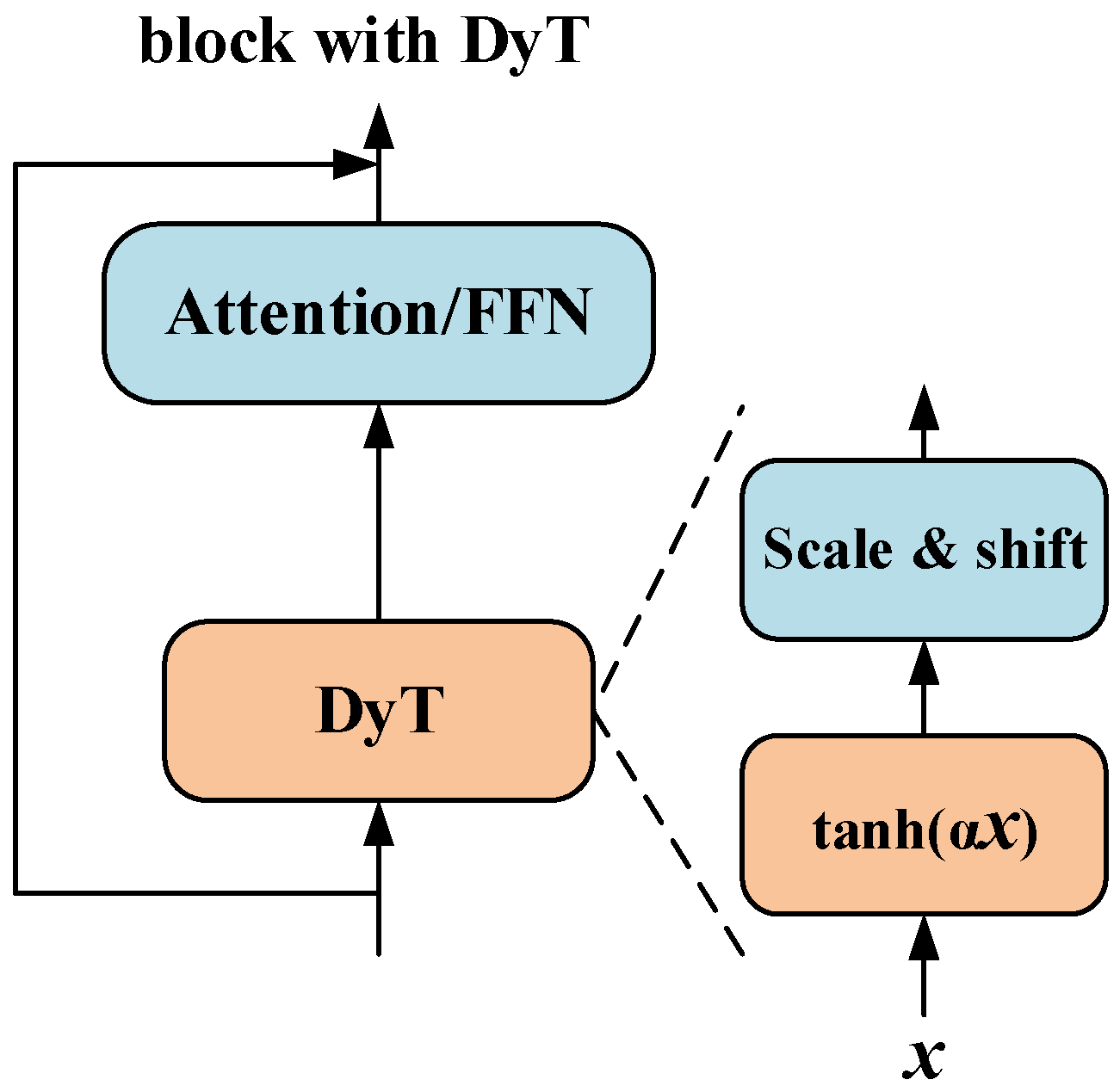

The encoder is composed of one Spectral layer and one Attention layer stacked sequentially. Meanwhile, the Layer Normalization (LN) in both the Spectral layer and Transformer layer is replaced with DyT. This modification aims to enhance frequency information capture capability and training efficiency while preserving spatiotemporal context modeling capacity.

The sequential stacking of the Spectral and Attention layers, combined with residual connections, ensures that inter-spectral correlations learned in the frequency domain are preserved and enhanced. The DyT module introduces a bounded nonlinearity that adaptively modulates activations, preventing feature attenuation while maintaining gradient flow.

Since the introduction of Batch Normalization (BN) in 2015, normalization layers-such as Layer Normalization (LN) and RMSNorm-have become core components of modern neural networks and are widely regarded as essential for effectively training deep networks. These layers accelerate convergence and stabilize training by computing the mean and variance of activations and applying an affine transformation. Zhu et al. observed that in deep transformer models, the input-output mapping of LN exhibits a tanh-like

S-shaped curve rather than a simple linear transformation. Based on this insight, they proposed DyT as a plug-in replacement for normalization layers [

31]. Given an input tensor

, the DyT layer is defined as follows:

where

is a learnable scalar parameter that adapts to different input ranges (dynamic scaling),

and

are learnable channel-wise vector parameters, functioning identically to the affine transformation parameters in normalization layers.

The DyT module ensures gradient stability through the properties of the tanh function and the learnable scaling parameter α. The derivative is bounded and non-zero, preventing gradient instability under large-magnitude activations. This allows DyT to maintain stable gradients during training.

The structure of DyT is illustrated in

Figure 3. Integrating DyT into existing architectures is straightforward: one DyT layer replaces one normalization layer. This substitution can be applied within attention blocks, within FFN blocks, and to the final normalization layer. Only the normalization layers are replaced with DyT, while all activation functions and other components of the original architecture remain unchanged.

- 2.

Spectral layer

As shown in

Figure 4a, the Spectral layer transforms the input token sequence into the frequency domain via the Fourier Transform, modulates the features using learnable complex weights, and then transforms back to the spatial domain via the Inverse Fourier Transform.

First, after passing

through the DyT layer, the Fourier Transform is applied:

where

denotes the discrete Fourier transform.

The result is then fed into the Spectral Gating Network (SGN):

is the activation function (e.g., GELU). Considering that both

and

are complex numbers, Equation (6) is extended by applying complex multiplication rules. The expanded equations are as follows:

where

,

. The signal is then transformed back to the spatial domain via the Inverse Fourier Transform. The final output features are

- 3.

Attention layer

The input to this layer is the output

from the Spectral layer. It first passes through a DyT layer:

The result is then fed into the Multi-Head Self-Attention (MSA) layer:

A residual connection is applied:

The final output features are

Finally, is decomposed to obtain two context-enriched tokens , which serve as the input to the decoder.

The fusion function is defined through residual connections, ensuring gradient consistency across domains. The gradients flow directly from the Attention layer back to the Spectral layer via the residual path, avoiding domain-specific shifts. The DyT module, with its learnable parameters, further stabilizes gradients by providing a smooth and adaptive activation function.

This design enhances local feature extraction capability and optimizes the normalization mechanism while retaining the global modeling power of the Transformer, making it suitable for resource-constrained remote sensing change detection tasks.

3.2.3. Decoder

The paper employs an improved Siamese Transformer Decoder (TD) [

15] to refine the image features of each temporal phase. As shown in

Figure 1, given the feature sequence

, the TD leverages the relationship between each pixel and the tokens

to obtain the refined features

. The queries are derived from the image features

, while the keys and values come from the tokens

.

Formally, at each layer, the Multi-head Cross-Attention (MCA) is defined as

where

,

,

are linear projection matrices,

h is the number of attention heads.

The DyT module is also used to replace the normalization layers within the Transformer decoder.

3.3. Network Details

The feature extraction network is based on ResNet, with the stride in the last two stages set to 1 to mitigate excessive loss of spatial information and retain richer detailed features. Subsequently, the network is augmented with a pointwise convolution layer and a bilinear interpolation layer. The pointwise convolution reduces the feature dimensionality, thereby decreasing computational overhead in subsequent processing. The bilinear interpolation layer upscales the feature maps to match the spatial size of the original input image, effectively preserving fine spatial details while maintaining reduced dimensionality.

The key hyperparameters were determined through a grid search on the validation set of LEVIR-CD. The token length L was evaluated from the set {2, 4, 8, 16}, with L = 4 providing the optimal balance between performance and computational cost. The number of attention heads h was searched over {4, 8, 16}, and the number of decoder layers over {4, 8, 12}. The configuration (L = 4, h = 8, decoder layers = 8) consistently yielded the best results and was subsequently fixed for all experiments. The layer number of the Transformer encoder is set to 1, maintaining essential contextual modeling capability while minimizing model complexity. In contrast, the Transformer decoder employs 8 layers to thoroughly refine features through multi-stage decoding, thereby enhancing the capability to capture change-related information. This configuration enables the extraction of diverse feature representations across different subspaces, strengthening the model’s expressive power.

A very shallow FCN serves as the prediction head for change discrimination. Given the two upsampled feature maps

, the prediction head generates a predicted change probability map

, denoted as

where D represents the feature difference image,

represents the change classifier, and

is the softmax function. The change classifier comprises two 3 × 3 convolutional layers with BatchNorm, having output channels of 32 and 2, respectively. During inference, the predicted mask

is generated by applying an Argmax operation along the channel dimension of P on a pixel-wise basis.

Loss Function: The cross-entropy loss is used to optimize the network during training. This loss quantifies the disparity between the predicted probabilities and ground truth labels, defined as

where

and

represents the ground truth label at pixel

. Minimizing this loss enables the model to align its predictions progressively closer to the true change distribution.

4. Results

The implementation and training of the model were carried out using PyTorch on an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3050Ti Laptop GPU. We adopted a linearly decaying learning rate strategy, starting from an initial value of 0.01 and reducing to zero over the course of 100 epochs. After every training epoch, validation was conducted, and the model achieving the highest performance on the validation set was selected for final evaluation on the test set.

4.1. Experimental Data

To ensure a comprehensive evaluation, experiments are performed on three widely used public benchmarks for remote sensing change detection: LEVIR-CD, WHU-CD, and DSIFN-CD. The main characteristics of these datasets are provided in

Table 1.

LEVIR-CD [

9] serves as a large-scale benchmark for building change detection, focusing on urban dynamic monitoring. It contains 637 pairs of high-resolution optical remote sensing images (0.5 m resolution), each with a size of 1024 × 1024 pixels. The dataset covers diverse urban and suburban areas, including structured changes such as building construction, demolition, and expansion, as well as interfering factors like shadow shifts and vegetation changes. It provides pixel-level change labels, with a focus on annotating changes in building outlines, making it suitable for evaluating the ability of models to detect regular geometric structures. For the experiments, images were cropped into 256 × 256 patches to match the model input size, balancing computational efficiency and detail preservation. The dataset was randomly divided into training, validation, and test sets. Small buildings (e.g., those with an area < 50 pixels) are susceptible to shadow interference, and illumination variations between time points may cause spectral shifts, testing the model’s sensitivity to subtle changes and robustness against disturbances.

WHU-CD [

10] is a post-earthquake reconstruction monitoring dataset released by Wuhan University. It contains aerial images from 2012 and 2016, covering an area of 20.5 km

2, with geographically corrected high-precision building vector/raster labels. The dataset focuses on building damage, reconstruction, and mixed land cover changes (e.g., spectral overlap between ruins, temporary structures, and unpaved roads) in post-disaster areas. Changes are multi-category and exhibit irregular boundaries. Semantic ambiguity in post-disaster scenes (e.g., distinguishing debris from natural terrain) and significant vegetation spectral differences due to cross-seasonal imaging require the model to have strong semantic discrimination and cross-domain feature adaptability. Images were cropped into non-overlapping 256 × 256 patches and randomly split into training, validation, and test sets.

DSIFN-CD [

32] is a high-resolution dataset designed for natural disaster response, consisting of bi-temporal images from six Chinese cities sourced from Google Earth. It includes abrupt changes caused by floods, earthquakes, etc. Images were cropped to 512 × 512 pixels and augmented (e.g., rotation, noise injection) to enhance model generalization. The final dataset contains 3600 training pairs, 340 validation pairs, and 48 test pairs. It primarily contains unstructured abrupt changes (e.g., flooded areas, landslide boundaries), with irregular shapes, blurry edges, and significant noise (e.g., cloud occlusion, sensor noise). The dataset emphasizes noise robustness and accurate localization of irregular boundaries, requiring the model to effectively suppress interference (e.g., distinguishing water bodies from clouds) and completely capture the topology of changed regions.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

The primary evaluation criterion was the F1-score, complemented by precision, recall, Intersection over Union (IoU), and Overall Accuracy (OA). The corresponding formulas are provided below:

where TP, FP, FN, and TN denote true positives, false positives, false negatives, and true negatives, respectively.

4.3. Comparison Methods

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed method, comparative experiments were conducted with the following methods:

FC-EF [

33]: combines an early fusion strategy with a U-Net architecture. The input is formed by concatenating a pair of bi-temporal images along the channel dimension, processed by a network with only 4 max-pooling and 4 upsampling layers (differing from U-Net’s 5). Its advantage lies in leveraging bi-temporal information early, but direct image fusion may introduce redundancy, and it lacks targeted feature selection and long-range dependency modeling for dynamic changes in complex scenes.

FC-Siam-Diff [

33] employs a feature-level fusion strategy based on a Siamese fully convolutional network (FCN). This architecture derives multi-level spatial features through dual-branch encoding and integrates bitemporal information by computing feature differences between the paired inputs.

FC-Siam-Conc [

33]: based on a Siamese network architecture processing pre- and post-change images with shared parameters. Features from different temporal phases are extracted separately and concatenated at the decoder layer. While it captures feature differences to some extent, the lack of an effective global modeling mechanism limits its use of long-range contextual information, leading to missed or false detections in changes with complex spatial distributions.

BIT [

6] employs a Transformer encoder–decoder architecture to augment the contextual representation of CNN features through semantic tokens. Change maps are subsequently generated through feature differencing.

ChangeFormer [

7], a hierarchical Transformer architecture based on a Siamese network, efficiently accomplishes remote sensing image change detection tasks by incorporating a lightweight decoder.

4.4. Experimental Results and Analysis

The specific evaluation metrics are presented in

Table 2, the best metric(s) are highlighted in bold.

Table 2 shows the quantitative comparison results between the proposed method (Ours) and five existing change detection methods on three test datasets: LEVIR-CD, WHU-CD, and DSIFN-CD. As can be seen from the table, the proposed method significantly outperforms other methods in terms of F1-score across all datasets, achieving 86.78%, 91.49%, and 79.36%, respectively, which are 1.21, 1.51, and 2.18 percentage points higher than the second-best method. Furthermore, it also demonstrates excellent performance in terms of IoU and OA, achieving optimal results especially on the WHU-CD and DSIFN-CD datasets, validating the robustness and generalization capability of the proposed method in complex scenarios.

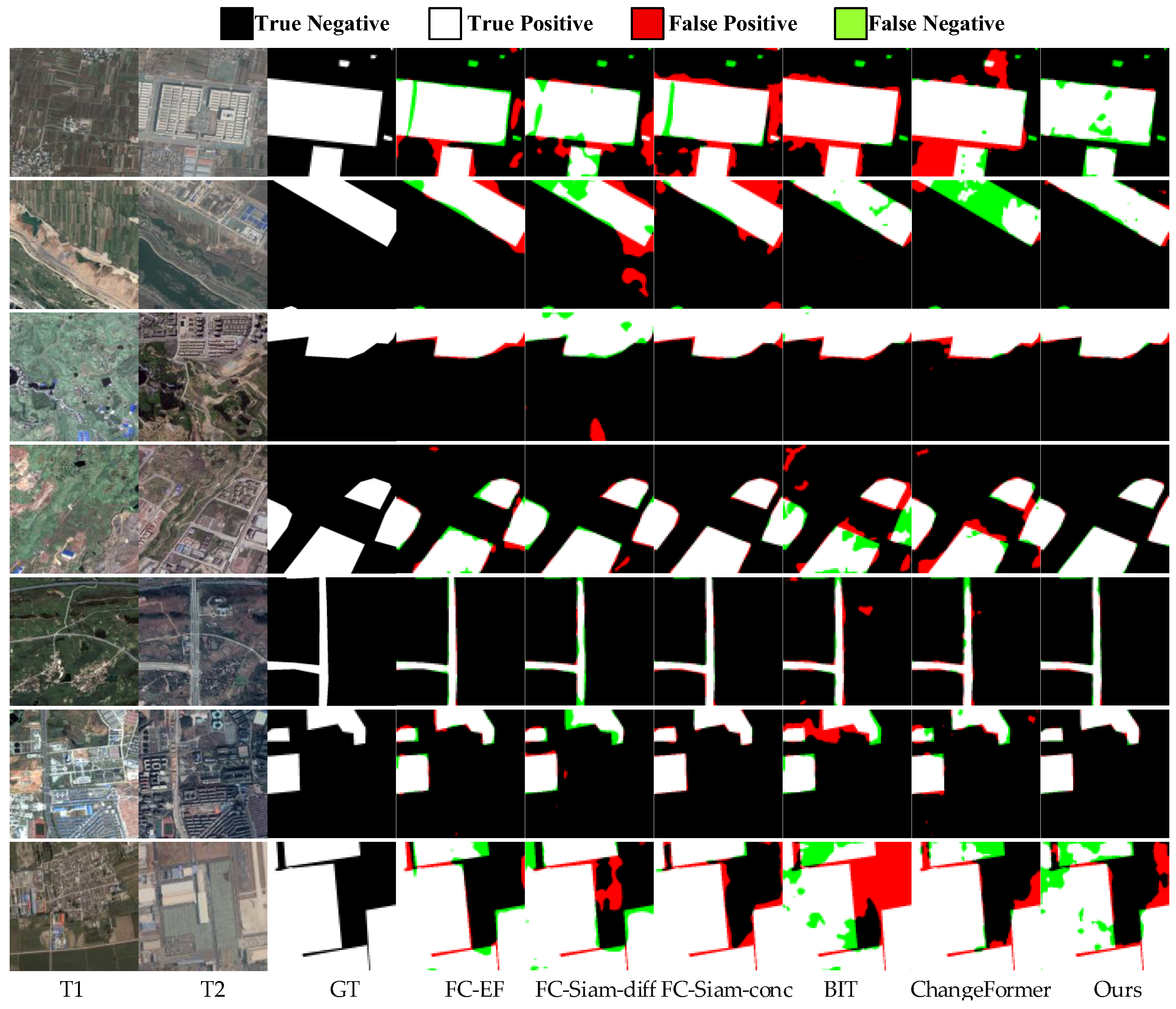

To visually demonstrate the detection performance of each method, the visualization results on the LEVIR-CD, WHU-CD, and DSIFN-CD datasets are presented in

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, respectively. For ease of analysis, different colors are used to denote the detection results: white indicates True Positives (TP), black indicates True Negatives (TN), red indicates False Positives (FP), and green indicates False Negatives (FN). It can be observed that the proposed method excels in suppressing false alarms and missed detections, showing distinct advantages particularly in the following three types of scenarios:

(1) Robustness against Pseudo-change Interference: Convolutional-based methods (e.g., FC-EF, FC-Siam-Conc) and some Transformer-based methods (e.g., BIT, ChangeFormer) are prone to generating false alarms in unchanged areas (e.g., shadows, roads). In contrast, the proposed method, through the synergistic modeling of the Spectral and Attention layers, effectively suppresses pseudo-change responses caused by spectral variations.

(2) Detection of Small Objects and Boundary Integrity: The proposed method demonstrates a more complete detection capability for small buildings and irregular change areas, significantly reducing missed detections. This indicates the advantage of the proposed encoder structure in preserving high-frequency details and modeling long-range dependencies.

(3) Cross-Seasonal and Noise Robustness: Under the interference of seasonal variations and sensor noise present in WHU-CD and DSIFN-CD, the proposed method still maintains high detection accuracy, highlighting the role of the DyT module in dynamically adapting feature distributions and enhancing the model’s generalization capability.

The performance improvement of the proposed method stems not only from the global modeling capability of the Transformer but also from the synergistic effect of the local-global feature complementary mechanism and the dynamic activation adjustment strategy as follows:

Global Modeling as the Foundation: The self-attention mechanism constructs long-range dependencies between pixels, enabling the model to understand the logic of changes (e.g., “building expansion-road extension”, “post-disaster reconstruction-land cover conversion”) from a semantic level.

Dynamic Mechanism as the Key: The DyT module adaptively adjusts activation thresholds through learnable scaling factors and bias parameters, significantly enhancing the model’s training stability and feature discrimination capability under complex imaging conditions.

In the failure cases illustrated in the last rows of

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, the proposed method exhibits limitations under complex scenarios characterized by spectral variability, semantic ambiguity, and strong noise interference. Specifically, in LEVIR-CD (

Figure 5, last row), false positives occur in shadow-affected areas and false negatives in small or occluded buildings due to insufficient suppression of spectral variations and loss of fine-grained details during token compression. For WHU-CD (

Figure 6, last row), cross-seasonal imaging leads to misclassification of spectrally similar unchanged regions (e.g., vegetation and ruins) as changes, while irregular boundaries of actual changes are partially missed, reflecting challenges in local-global feature integration. In DSIFN-CD (

Figure 7, last row), noise and cloud occlusion cause false alarms, and blurred change boundaries (e.g., flood areas) remain undetected, highlighting the model’s sensitivity to extreme environmental disturbances. These failures underscore the need for enhanced robustness in handling non-stationary feature distributions and optimizing the trade-off between local detail preservation and global semantic modeling.

4.5. Ablation Experiments

To validate the effectiveness of the key components in the proposed method, we designed a systematic ablation study, focusing on analyzing the role of the Spectral layer in the encoder, the synergistic effect of combining the Spectral and Attention layers, and the contribution of the DyT module to performance and computational efficiency. The experiments were conducted on the WHU-CD dataset, and the results are presented in

Table 3, the best metric(s) are highlighted in bold.

- (1)

Effectiveness of the Spectral Layer

The Spectral layer transforms the input features into the frequency domain via the Fourier Transform and modulates high-frequency components (e.g., edges, textures) using learnable complex weights, thereby enhancing the model’s ability to capture local structures and periodic features in remote sensing imagery. Comparing Variant 3 (Spectral only + LN) with Variant 1 (Attention only + LN), the introduction of the Spectral layer increases the F1-score from 88.64 to 89.59 and the IoU from 81.19 to 83.27, indicating its advantage in suppressing pseudo-changes and enhancing detail perception. Further comparing Variant 4 (Spectral only + DyT) with Variant 2 (Attention only + DyT) shows an F1-score improvement of 4.59 percentage points, demonstrating the irreplaceable role of the Spectral layer in modeling high-frequency information.

- (2)

Synergistic Effect of Combining Spectral and Attention Layers

The Spectral layer focuses on local frequency features, while the Attention layer models global semantic dependencies through the self-attention mechanism. The combination of these two forms a “local-global” complementary feature extraction mechanism. Variant 6 (Spectral + Attention + DyT) achieves the best performance (F1 = 91.52, IoU = 85.35), outperforming the single-module Variants 2 and 4. This indicates that their synergistic effect can more comprehensively capture change information: the Spectral layer enhances the discrimination of edges and textures, while the Attention layer correlates semantic information across regions, jointly improving detection robustness in complex scenes.

- (3)

Contribution of DyT to Performance and Computational Efficiency

The DyT module replaces traditional normalization layers with learnable dynamic parameters, enhancing training stability and convergence speed while maintaining the nonlinearity of the activation function. In terms of computational efficiency, comparing Variant 5 (Spectral + Attention + LN) with Variant 6 (Spectral + Attention + DyT), DyT reduces the number of parameters from 12.37 M to 12.16 M and FLOPs from 1.3706 G to 1.2168 G, while simultaneously increasing the F1-score by 2.66 percentage points.

The superior performance of Variant 4 (Spectral + DyT) over Variant 5 (Spectral + Attention + LN) suggests that the DyT module is particularly effective at conditioning the features from the Spectral layer. While replacing LN with DyT in a pure Attention encoder (Variant 2) led to a performance drop, its integration within the full Spectral-Attention encoder (Variant 6) yielded the best results, indicating that DyT’s dynamic adaptation is particularly effective at processing the hybrid features produced by our cooperative encoder.

The ablation study demonstrates that the Spectral layer is key to enhancing local feature perception, its combination with the Attention layer achieves efficient fusion of global and local features, and the DyT module significantly optimizes computational efficiency while maintaining accuracy. Together, these three components constitute the competitive advantage of the proposed method in terms of both performance and efficiency.

To ensure the statistical robustness and reproducibility of our results, all experiments were conducted over three independent runs with a fixed random seed (42) for weight initialization and data shuffling. The detailed experimental setup and key hyperparameters are listed in

Table 4. The reported results are the mean values of these runs. Furthermore, to evaluate the model’s practicality, we measured its average inference time per image and peak GPU memory consumption during training on the LEVIR-CD test set and during a full training cycle, respectively.

5. Discussion

The experimental results presented in this study consistently demonstrate the superiority of the proposed CNN-Transformer hybrid network with DyT across multiple challenging change detection benchmarks. The performance gains, particularly in terms of F1-score and computational efficiency, can be attributed to the synergistic interplay of the model’s core components. Beyond the quantitative metrics, several profound implications and insights warrant further discussion.

First and foremost, the success of the Spectral-Attention Cooperative Encoder validates a pivotal design philosophy for remote sensing image analysis: the necessity of a dual-path strategy that explicitly models both local high-frequency signals and global semantic contexts. Remote sensing scenes are inherently multi-scale; changes manifest as fine-grained alterations in texture and edges (e.g., a new building’s outline) while being governed by large-scale semantic logic (e.g., urban expansion patterns). Traditional CNNs often blur the former, while pure Transformers can be computationally prohibitive and may underfit local details. Our encoder elegantly bridges this gap. The Spectral layer, operating in the Fourier domain, acts as a highly efficient and dedicated edge/texture enhancer, making the model more sensitive to the precise spatial discontinuities that often delineate change boundaries. Concurrently, the Attention layer constructs the “big picture,” understanding that a spectral shift in a large, contiguous area is more likely to be a genuine change (e.g., construction) than noise. This complementary mechanism is the cornerstone of our model’s robustness against pseudo-changes and its ability to preserve boundary integrity.

Secondly, the introduction of the DyT module represents a significant step towards adaptive and efficient deep learning for remote sensing. Our ablation studies confirm that DyT is not merely a drop-in replacement for Layer Normalization but a performance and efficiency enhancer. We posit that its learnable scaling parameter α allows the model to dynamically adjust the saturation boundaries of the activation function based on the feature distribution of complex remote sensing imagery, which is often non-stationary due to varying illumination, seasonality, and sensor characteristics. This adaptive property contributes to superior training stability and faster convergence. More importantly, by simplifying the network operations (replacing the mean-variance calculations of LN with a single hyperbolic tangent), DyT directly reduces the computational footprint, making the entire framework notably more suitable for practical, resource-conscious applications. This finding aligns with the growing pursuit of “normalization-free” architectures in the broader computer vision community and showcases its particular value in compute-intensive fields like remote sensing. Furthermore, while DyT demonstrated consistent advantages over LayerNorm, a more comprehensive comparison with other advanced normalization techniques like RMSNorm and ScaleNorm remains an valuable avenue for future research to fully establish its relative superiority.

However, no framework is without its limitations. Firstly, while the Semantic Token Generator effectively reduces computational complexity, it operates as a form of bottleneck. The model’s performance is dependent on key hyperparameters. An analysis of token length L revealed that while L = 4 offers a good efficiency-accuracy trade-off, performance degrades if L is set too low (e.g., L = 2), failing to capture sufficient semantic diversity, or too high (e.g., L = 8), introducing noise and computational burden. Similarly, the model shows a preference for a specific number of attention heads (8), with deviations leading to sub-optimal feature representation. These sensitivities underscore the importance of careful hyperparameter tuning for optimal deployment. Secondly, our model, like most deep learning-based CD methods, remains a 2D image analysis tool. It does not explicitly model the 3D geometry of scenes or the photometric conditions during acquisition. While it shows robustness to shadow and illumination variations, extreme geometric differences (e.g., significant viewpoint changes) or interactions between geometry and illumination could still pose challenges. Integrating digital surface models (DSM) or physics-informed constraints could be a promising avenue to address this. Finally, the current framework is designed for bi-temporal analysis. The growing availability of multi-temporal satellite image time series (SITS) calls for architectures capable of modeling temporal dynamics beyond two time points.

In a broader context, this work contributes to the paradigm shift from merely pursuing higher accuracy on benchmarks to developing accurate and efficient models for real-world deployment. The demonstrated efficiency makes it a strong candidate for on-board processing on satellites or UAVs, enabling real-time monitoring for disaster response, illegal construction detection, and precision agriculture. Furthermore, the principles of semantic tokenization and hybrid local-global modeling are highly transferable. The framework holds substantial promise for cross-modal change detection tasks, such as between optical and SAR imagery, where establishing a common, robust feature representation is the key challenge.