Abstract

Existing model watermarking methods fail to provide adequate protection for edge intelligence models. This paper innovatively integrates the characteristics of model fingerprinting, proposing a model watermarking method named FingerMarks that enables both model attribution and traceability of edge node users. The method initially constructs a uniform trigger set and an encoding scheme through fingerprint extraction, which effectively distinguishes the host model from independently trained models. Based on the encoding scheme, distinct user IDs are converted and mapped into specific labels, thereby generating distinct watermark-embedded trigger sets. Watermarks are embedded using a progressive adversarial training strategy. Comprehensive evaluation across multiple datasets confirms the method’s performance, uniqueness, and robustness. Experimental results show that FingerMarks effectively identifies the watermarked model while maintaining superior robustness compared to state-of-the-art alternatives.

1. Introduction

Thanks to the continuous innovation in model algorithms, the widespread adoption of dedicated AI chips, and the support of AI development strategies and policies in various countries, deep neural networks (DNN) have achieved cross-domain, pervasive development in recent years in fields such as medical diagnosis [1], industrial applications [2], and finance [3]. As deep learning models are increasingly shared or distributed via APIs, verifying model ownership and detecting unauthorized copies is essential [4,5,6,7]. With the rapid proliferation of edge computing technologies, lightweight DNN models deployed on terminal devices have become core components in application scenarios such as smart cities and the Industrial Internet of Things [8]. However, the accessibility of such distributed deployment models further exacerbates the risk of copyright infringement [9,10,11]. This research focuses on addressing the copyright protection issues of DNN models under distributed deployment conditions.

Model watermarking and model fingerprinting are two primary methods for protecting the intellectual property of models. Model watermarking involves embedding watermark information representing intellectual property during model training. In the event of copyright disputes, the watermark information is extracted to prove copyright ownership [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Depending on whether internal model information is required during extraction, it can be categorized into black-box watermarking and white-box watermarking. Since black-box watermarking only requires the model’s output results for verification, it has better application prospects compared to white-box watermarking. Traditional black-box watermarking is zero-bit watermarking, where a customized set of trigger templates is used for different models, and the presence of watermark information is determined based on the extent to which the classification results meet the criteria. Model fingerprinting, on the other hand, involves extracting unique fingerprint information representing the individual model after training. By comparing the fingerprints extracted from a suspicious model, it can be verified whether it is the host model or has a derivative relationship with the host model [20,21,22,23,24,25,26].

Currently, traditional model watermarking and model fingerprinting methods are unable to meet the requirements for copyright protection in distributed model deployment scenarios. White-box watermarking cannot achieve watermark verification in remote access settings of distributed deployment because it requires access to the model’s internal information. Black-box model watermarking methods rely on a specific trigger set to determine model copyright. After the watermark information is embedded during the training phase and the model is distributed, distinguishing between distributed models requires embedding different watermarks, and verification involves multiple accesses to traverse different trigger sets. Model fingerprinting does not alter the model itself and thus cannot differentiate between distributed models.

To meet the need for authenticating edge users, recent research advances have proposed multi-bit watermarking algorithms [27,28,29]. Chen et al. [27] introduced the first black-box multi-bit watermarking method, which generates a trigger set corresponding to the user ID through adversarial attacks. However, this method can only distinguish single users and fails to effectively address the requirements of copyright protection in multi-model distributed deployment scenarios. Li et al. [28] proposed a multi-bit watermarking method that does not rely on specific inputs. However, the information extraction process of this method requires the model’s softmax output rather than just the label results, limiting its applicability. Moreover, like Chen et al. [27], it is not effectively equipped to handle multi-model distributed deployment scenarios. Leroux et al. [29] uses the same trigger set to distinguish between different users by analyzing the responses of different models. However, this introduces a new issue: once models embedded with watermarks are allowed to return different results, how can we prevent models without watermarks from producing similar outcomes? Additionally, the robustness of current multi-bit watermarking algorithms still requires improvement.

Model fingerprinting technology, on the other hand, does not require modifying the original model but merely extracts fingerprint information that represents the unique identity of the model. This technology typically demands high robustness. This paper proposes a multi-bit model watermarking method that incorporates fingerprinting technology, mapping watermark information representing different models into fingerprint information. This approach ensures strong robustness of the watermarking method while effectively distinguishing between different model instances. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- We propose FingerMarks, a novel black-box multi-bit model watermarking method that enables simultaneous verification of independent models and identification of end-users.

- This method is the first to utilize fingerprint samples as watermark triggers and incorporates a new watermark embedding algorithm designed to balance embedding efficiency with watermark robustness.

- The proposed method has been validated on multiple datasets and models. Experimental results demonstrate that our approach can effectively determine the user attribution of models while exhibiting strong robustness in embedded information.

2. Related Work

To protect the intellectual property of deep learning models, current research primarily focuses on two paradigms: active and passive protection. As an active protection mechanism, model watermarking operates by embedding a specific, identifiable signature into the model during training or fine-tuning. This field was initially inspired by multimedia watermarking techniques [30]. Uchida et al. [12] drew on spread spectrum communication principles to first propose embedding watermark information directly into neural network weights. Subsequently, Adi et al. [14] innovatively introduced the concept of backdoor attacks into watermarking tasks. By selecting a set of specific images as trigger samples and assigning them outputs different from those of the normal model, they enabled verification of model ownership. Existing watermarking techniques can be broadly categorized into white-box watermarking and black-box watermarking. White-box watermarking embeds the watermark or related information directly into the model parameters. Black-box watermarking constructs a trigger set composed of specific data points. When a watermarked model receives these inputs, it exhibits anomalous prediction behavior.

In recent years, the research focus has expanded beyond improving watermark robustness against attacks such as model extraction, fine-tuning, and compression, also to include broadening the application scope of watermarking techniques. Currently, most watermarking schemes are still primarily designed for classification tasks, with only a few works exploring other machine learning domains such as image processing networks [31], large language models [32], diffusion models [16], and multimodal models [33]. Therefore, developing watermarking schemes suitable for a wider range of machine learning applications represents an important direction for future research. In the field of large language model, the importance of multi-bit watermarking has gradually been recognized, and several important research findings have been proposed [34,35,36].

In contrast to active watermarking, model fingerprinting is a passive identification paradigm. It does not modify the model’s parameters or structure; instead, it extracts intrinsic and unique behavioral characteristics to serve as identity markers. For instance, refs. [20,21,22] customized adversarial examples as model fingerprints or components of fingerprints using gradient-based methods. Xu et al. [25] constructed trigger samples near the decision boundary and within the model’s stable regions, forming fingerprints by comprehensively leveraging the model’s duality and conviction factors. Other studies, such as Lin and Wu [37], identified sets of samples sensitive to model modifications by analyzing prediction discrepancies across submodels in deep ensemble models under tampering behaviors such as model compression and fine-tuning. Additionally, works like Wu [38] and Hu et al. [26] leveraged model privacy leakage characteristics as fingerprints, uniquely identifying a model by analyzing differences in its predictive behavior on specific data subsets.

The main advantage of fingerprinting techniques is their non-intrusive nature, which preserves the model’s original functionality. However, a persistent challenge is ensuring that fingerprints possess sufficient distinctiveness to effectively distinguish between independently trained yet functionally similar models, while also maintaining consistency across version updates. Therefore, one of the most promising future directions is the construction of hybrid protection systems that synergistically combine the verifiability of active watermarks with the stealth and resilience of passive fingerprints [39].

3. Threat Model and Requirements

In addition to providing access through open APIs, neural network models can also be directly sold. With the continuous enhancement of computational capabilities in edge devices, edge intelligence has gained increasing attention. However, this also brings risks of model copyright infringement. After obtaining the model, edge users may provide unauthorized access for profit, or models deployed on edge devices might be stolen by attackers and disguised as their own to offer services. This paper focuses on image classification network models. The watermarking method can only determine copyright ownership and identify the specific edge user from whom the model originated based on the label classification results obtained from a limited number of images via remote access. To achieve this objective, the watermarking method must meet the following requirements:

Performance: The watermarking framework, building upon a pre-trained model, must be designed with computational and functional efficiency as a primary concern. The process of generating user-specific models with embedded watermarks should be significantly more efficient than training from scratch, enabling rapid deployment and scalability. Critically, this efficiency must not come at the expense of the model’s primary function. The act of watermark embedding should introduce negligible degradation to the model’s performance on its original task.

Uniqueness: The watermarking scheme must confer a unique identity to the host model, allowing for unambiguous differentiation from any independently trained models of similar architecture and capability. This property of uniqueness is fundamental to preventing false attribution of ownership. The embedded signature should act as a distinctive fingerprint, ensuring that the verification mechanism yields a strongly positive response only for the specific watermarked host model. The method’s uniqueness should be empirically validated by demonstrating a clear statistical gap in the detection confidence between the genuine watermarked model and a cohort of non-watermarked, independently trained counterpart models, thereby ensuring the credibility of the ownership claim.

Robustness: Robustness serves as the critical benchmark for any practical model watermarking scheme. It requires that the embedded watermark remains persistent and verifiable under a spectrum of challenges, from routine model optimizations like fine-tuning and pruning to malicious attempts at removal via adversarial training. The ultimate objective is the development of an extraction algorithm that can reliably authenticate ownership with high statistical confidence after such transformations, thus providing a durable claim of ownership that withstands the model’s evolution and hostile actions.

4. Proposed Approach

4.1. Global Flow

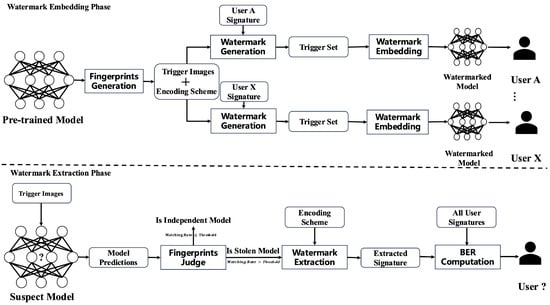

As shown in Figure 1, the entire method consists of two stages: watermark embedding and watermark extraction. In the watermark embedding stage, fingerprints are first extracted from the pre-trained model to generate trigger input images and an encoding scheme. In previous fingerprinting methods, each image corresponded to a fixed label. However, to simultaneously distinguish the pre-trained model from other independently trained models and express different watermark information, the fingerprint data extracted in our method allows each image to correspond to multiple labels. By encoding and mapping these multiple labels, multi-bit information can be represented. Subsequently, user fingerprints and the encoding method are combined to form watermark trigger data that reflects user identity. Watermark embedding is then achieved by fine-tuning the model.

Figure 1.

Overflow of FingerMarks. Watermark Embedding Phase (upper part): we assign a unique identifier to each distributed user and embed it into the pretrained model. All distributed models share a common set of verification triggers. A to X represent different authorized distribution users. Watermark Extraction Phase (bottom part): the classification label results of the trigger set are obtained through remote access, and models screened as suspicious are further verified to trace the source of distributed users. User ? represents the suspected user identity determined based on the watermark detection results.

In the watermark extraction stage, the images from the triggers are input remotely, and the model’s prediction label results are collected. The first step is to verify whether the prediction results appear in the label set of the model’s fingerprints. The proportion of matching results is compared to a threshold to determine whether the model is relevant. A low matching value indicates that the model is independent. Otherwise, user fingerprint information can be further extracted using the encoding scheme. By identifying the closest matching user fingerprint information, the specific distribution user from which the model originated can be determined.

4.2. Fingerprint Generation

Upon completion of model training, the model fingerprinting technique is first employed to extract images that capture the unique characteristics of the model, along with their corresponding labels. This extraction process leaves the host model entirely unchanged. For a DNN model, the output of the last fully connected layer is a logits vector , where m is the number of classes. Given an image x, the predicted class label is . If traditional adversarial example methods are used to generate model fingerprints, and assuming the number of fingerprints is n, then n adversarial examples need to be generated sequentially based on the input images. For an image x, its corresponding adversarial example satisfies the condition , and the difference between and x is small enough to be imperceptible to the human eye. The pair consisting of and its output label forms a single model fingerprint. Denoting the output label as y, the set of model fingerprints can be represented as S:

The model fingerprints generated by this method can only distinguish individual models, with each distinct model possessing a unique fingerprint. To enable the same trigger set to both verify the host model and discriminate among different distributed models, we extend the concept of model fingerprinting. Originally designed to output a single deterministic label per image, our enhanced approach allows each image to output either of two potential label values. These dual-purpose labels can represent binary digits—0 or 1—enabling the embedding of traceable information directly into the model’s predictions. The extended model fingerprint is denoted as .

The output labels used in model fingerprints must satisfy at least two critical requirements. First, when presented with the same input image, the likelihood of other independently trained models producing an identical classification label should be sufficiently low to ensure strong model discriminability. Second, the embedded label value should not substantially degrade the model’s original classification performance.

While labels derived from adversarial examples inherently meet both conditions, identifying an alternative label value possessing similar properties remains challenging. Our analysis shows that although the ground-truth label of the original image adequately satisfies the second requirement (minimal performance impact), it fails to fulfill the first condition (model discriminability) reliably. To address this limitation, our approach enhances the model-specific discriminability of the ground-truth label by systematically minimizing its classification probability in adversarial examples. The resulting fingerprint image set can be formally defined as follows:

Clearly, obtaining a sufficient number of such images is infeasible through exhaustive search of training data or random generation. Inspired by the gradient descent optimization used in model training, we instead perform gradient descent directly on input images by optimizing a specifically designed loss function. To enhance adversarial robustness, we adapt the approach from Cao et al. [22] with modifications to ensure minimization of the original label’s classification probability. Let denote the logits output of the image x for label z, i denotes the original label of the image, j denotes the label with the least likelihood for the original image, and represents the perturbation applied to the image. The designed loss function is as follows:

Throughout the iterative process, images are randomly sampled from the training set as inputs. The hyperparameter k controls the margin between the logit value of label j and the second-highest logit value. Gradient descent is applied iteratively until the desired number of images is generated. During this process, the corresponding label values of i and j are recorded, and a mapping relationship between label categories and watermark bits is established to form an encoding scheme. This mapping can be assigned randomly or follow a specific pattern. Typically, we can simply map the original label i to binary 0 and the adversarial sample label j to binary 1. The encoding scheme E can be represented as follows:

4.3. Watermark Embedding

Prior to model distribution, a unique identifier is encoded into the model for each authorized user, representing their distinct identity information. This identifier is formally defined as follows:

Based on the binary-to-label mapping defined in the encoding scheme E, the watermark information is determined and organized into a trigger set :

The watermark embedding methodology is inspired by adversarial training principles. To achieve an optimal balance between embedding efficiency and robustness, we implement a dynamic strength adjustment mechanism. Samples in the watermark trigger set can be categorized into two types according to their embedded bit values:

- Samples Satisfying Classification Requirements—where the model’s current prediction aligns with the target adversarial label. These samples inherently exhibit fingerprint characteristics and require no model modification, as further adjustments could undermine their robustness. Thus, samples meeting this criterion are initially excluded from fine-tuning. However, as watermark embedding progresses, even these samples become affected by model changes. The embedding method must therefore resume fine-tuning when the target label’s classification probability decreases significantly to maintain fingerprint validity.

- Samples requiring model fine-tuning—where the target label corresponds to the original label of the image. To enhance robustness, adversarial examples are generated using the DeepFool method [40] and incorporated into the training data. However, to mitigate potential degradation of model accuracy, embedding strength is carefully controlled: we begin with a small subset of training samples and progressively increase the embedding ratio during fine-tuning.

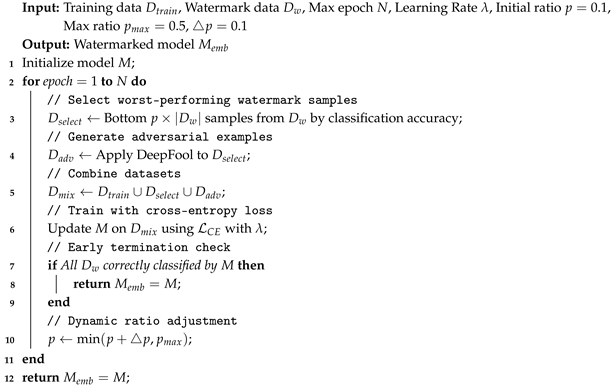

The embedding process is performed using stochastic gradient descent with a cross-entropy loss function. The embedding stops as soon as the watermark is successfully classified. The complete embedding procedure is outlined in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: Dynamic-Ratio Watermark Embedding with Adversarial Training |

|

The embedding strength is primarily controlled by three tunable parameters: the initial embedding ratio p, the maximum embedding ratio , and the ratio increment step size . Through experimental exploration, we provide recommended empirical values for these three parameters in Algorithm 1.

5. Experiments and Analysis

5.1. Implementation Details

This section outlines the experimental setup and procedures used to validate the FingerMarks. The evaluation employs three widely recognized image benchmarks: CIFAR-10 [41], CIFAR-100 [41], and ImageNet [42]. For the target models, our study utilizes GoogLeNet [43], ResNet-34 [44], and VGG-11 [45] architectures. The proposed framework was implemented in Python 3.10, leveraging the PyTorch 1.10.2 library [46] for development.

5.1.1. Datasets

CIFAR-10: The CIFAR-10 dataset is a widely adopted benchmark in image classification, comprising 60,000, 32 × 32 color images distributed across 10 mutually exclusive classes, such as airplanes, automobiles, birds, cats, and deer. The dataset is split into 50,000 training and 10,000 test images, providing a standardized framework for evaluating model performance on small-scale, low-resolution visual tasks. A GoogLeNet architecture model is trained on the CIFAR-10 as one of our target models.

CIFAR-100: The CIFAR-100 dataset extends the CIFAR-10 by introducing finer-grained categorization, consisting of the same 60,000, 32 × 32 images but organized into 100 classes grouped into 20 superclasses. This hierarchical structure enables investigations into transfer learning, meta-learning, and fine-grained recognition, as models must discern subtle distinctions between semantically similar categories. A ResNet-34 architecture model is trained on the CIFAR-100 as one of our target models.

ImageNet: The ImageNet dataset contains over 1.2 million high-resolution training images spanning 1000 diverse object categories, ranging from natural entities to human-made objects. The dataset’s scale and diversity drive progress in large-scale supervised learning, transfer learning, and robustness evaluation. Models pre-trained on ImageNet, such as ResNet, EfficientNet, and Vision Transformers, have become de facto feature extractors for downstream tasks, establishing them as an indispensable resource for benchmarking state-of-the-art visual recognition systems. We use the 50,000 validation examples for testing. A pre-trained VGG-11 model from PyTorch is used as one of our target models.

5.1.2. Metrics

We evaluate FingerMarks across three aspects: performance, uniqueness, and robustness. Performance is primarily measured by comparing the watermark embedding time and its impact on model accuracy. Watermark embedding is typically accompanied by fine-tuning on the training data. Therefore, the longer the training epochs, the smaller the impact on model accuracy, but the longer the watermark embedding time will be. Existing model watermarking methods often only consider the requirement of minimizing the decline in model accuracy. However, considering the application scenario of FingerMarks, which involves generating multiple edge AI models, it is necessary to achieve watermark embedding with as few training epochs as possible while maintaining high model accuracy.

Uniqueness and robustness are primarily measured by the model’s trigger set matching rate. The calculation of the matching rate requires collecting the model’s classification results for each trigger data and computing the proportion of data with the same classification label. Although both uniqueness and robustness are measured by the matching rate, their standards are opposite. Uniqueness requires the matching rate of the trigger dataset generated by the watermark verification method on independent models to be as small as possible. In contrast, robustness requires the matching rate on derived models to be as large as possible.

Regarding the security of the FingerMarks, as detailed in Section 4.2, the trigger set images, encoding scheme, and user identification information constitute confidential data exclusively held by the owner. Even if adversaries become aware of the adversarial attack methodology employed for watermark generation, they cannot reconstruct the original trigger set due to the vast search space involved. Consequently, FingerMarks demonstrates effective resistance against brute-force attacks initiated by malicious actors.

5.1.3. Baselines

FingerMarks is characterized by two key features. First, it functions as a multi-bit black-box model watermarking method, capable of encoding multiple bits of information through a set of triggers. Second, its verification results exhibit fingerprint-like properties, enabling clear discrimination between models with embedded watermarks and independently trained ones. To comprehensively evaluate the superiority of the proposed approach, we compare it against the most representative methods in two categories: multi-bit model watermarking and model fingerprinting.

The method in Leroux et al. [29] pioneered multi-bit watermarking for edge intelligence models. Its key characteristic lies in fine-tuning pre-trained models to rapidly generate distributed models embedded with different user identity information, with all distributed models sharing a uniform trigger set. For ease of comparative analysis, this method will hereafter be abbreviated as MBW. From the perspective of model watermarking requirements, FingerMarks is primarily compared with MBW on performance and robustness. Following the approach in Leroux et al. [29] and to facilitate a fair comparison, the number of trigger images was uniformly set to 30 in the experiments.

IPGuard [22] serves as a highly representative model fingerprinting method. It constructs model fingerprints by measuring the distance k between the two most probable classes. Through iterative evaluation across k values, it assesses fingerprint performance at varying distances to the decision boundary. For comparative analysis, we adopt the optimal k values reported in their work: 10 for CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100, and 100 for ImageNet. From the perspective of model fingerprinting requirements, FingerMarks and IPGuard are primarily compared on uniqueness and robustness.

5.2. Results

5.2.1. Performance

As summarized in Table 1, the proposed watermarking method achieves an effective balance between computational efficiency and model fidelity. Across multiple datasets and model architectures—including GoogLeNet on CIFAR-10, ResNet-34 on CIFAR-100, and VGG-11 on a streamlined version of ImageNet—our approach completes the embedding process within a practically acceptable duration, with only a marginal decrease in model accuracy. It is noteworthy that all experiments were conducted under limited hardware conditions, utilizing an Intel Core i5-8500 CPU and an NVIDIA GTX 1080Ti GPU. To accommodate resource constraints, the ImageNet dataset was reduced to 100 samples per class during training, which may partially account for the observed accuracy drop in this case. Nevertheless, our method consistently exhibits less performance degradation compared to the baseline, underscoring its advantage in preserving the functional integrity of the original model.

Table 1.

Performance obtained by watermarking different models.

When embedding watermarks, MBW only fine-tunes the trigger set data without considering the model’s original dataset. This approach cannot guarantee that the model’s accuracy after embedding will still meet requirements. Although the baseline technique achieves faster embedding speeds—as evidenced by the sub-second times reported—this gain comes at the cost of greater accuracy reduction, particularly noticeable in the CIFAR-10 and ImageNet experiments. In contrast, the FingerMarks method requires fine-tuning on the model’s training dataset, resulting in longer embedding times compared to MBW. This time difference becomes even more pronounced on large-scale training datasets. However, the progressive embedding process proposed by FingerMarks can effectively minimize the number of fine-tuning iterations. When embedding watermarks, MBW only fine-tunes the trigger set data without considering the model’s original dataset. This approach cannot guarantee that the model’s accuracy after embedding will still meet requirements. In contrast, the FingerMarks method requires fine-tuning on the model’s training dataset, resulting in longer embedding times compared to MBW. This time difference becomes even more pronounced on large-scale training datasets. However, the progressive embedding process proposed by FingerMarks can effectively minimize the number of fine-tuning iterations. More importantly, in subsequent robustness evaluations against common model attacks such as fine-tuning, pruning, and parameter noise, our watermark demonstrated significantly stronger survivability and detectability. This suggests that the slightly longer embedding time is a worthwhile trade-off, as it contributes to a more resilient and durable watermark, better suited for real-world deployment where model integrity and long-term authentication are critical.

In our experiments, we demonstrated the watermark embedding time for a single user across different datasets. As explained in Section 4.3, the configuration of the embedded information correlates with embedding efficiency. In extreme scenarios, if the trigger set matches the fingerprint exactly, no embedding is necessary, resulting in zero embedding time. Conversely, if none of the labels in the trigger set align with those in the fingerprint, each bit of information requires model fine-tuning during embedding, leading to the maximum embedding duration. Given that the trigger set dataset size is 30, the supported number of users reaches , which is sufficiently large. Therefore, we disregard extreme cases and assign distributed user IDs through random generation. Additionally, it should be noted that the embedding times for different users remain comparable and operate independently without mutual interference, enabling concurrent execution.

5.2.2. Uniqueness

The uniqueness property is crucial for a watermarking scheme, as it requires the verification results of the watermark trigger set to exhibit significant discrimination between models with embedded watermarks and independently trained, unrelated models. This discriminative capability ensures that unrelated models are not falsely identified as stolen or watermarked instances.

The independent models were each trained separately on identical training data. These models may share the same architecture as the target model or employ different architectures. For each dataset, we trained six models with an architecture identical to the target model and six with distinct architectures. All models for the CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 benchmarks were trained from scratch. Due to our limited computational resources, we do not train the same architecture neural network classifiers for ImageNet and leverage popular pre-trained models that are available in PyTorch as different architecture models.

As illustrated in Table 2, the proposed FingerMarks method demonstrates markedly low matching rates across a diverse set of independent models, including those with both identical and different architectures. For instance, the maximum matching rate observed on CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and ImageNet models is only 0.5, 0.16, and 0.06, respectively, with mean values as low as 0.33, 0.06, and 0.02. These results confirm that the proposed method effectively minimizes false positive verifications, a limitation observed in prior works such as Leroux et al. [29], where verification outputs from unrelated and watermarked models were indistinguishable.

Table 2.

Matching rates on independent models.

Furthermore, the experimental evidence highlights the scalability of FingerMarks in maintaining uniqueness as model complexity and the number of classification categories increase. The matching rate is shown to approach zero in models with larger output spaces, such as those evaluated on ImageNet, where even architecturally similar models like different VGG variants exhibit near-zero matching rates. This trend underscores the method’s robustness in distinguishing independent models across varying architectures and datasets. In contrast, baseline methods such as IPGuard show consistently higher discriminative ambiguity, as reflected in their higher mean and maximum matching rates. These findings validate that FingerMarks not only fulfills the uniqueness requirement but also adapts effectively to diverse and complex deployment scenarios, providing a reliable mechanism for model authentication without compromising specificity.

5.2.3. Robustness

To comprehensively evaluate the robustness of FingerMarks, as proposed in Leroux et al. [29], Lukas et al. [47] and Cao et al. [22], we conducted multiple attack experiments, including FTAL (fine-tune all layers), FTLL (fine-tune last layer), RTAL (retrain all layers), WP (weight pruning), AT (adversarial training), and IN (input noising).

FTAL and FTLL: Fine-tuning methods utilize training data and are divided into two categories based on whether only the last layer is trained: Fine-tune Last Layer (FTLL) and Fine-tune All Layers (FTAL).

RTAL: Retraining methods randomly reinitialize the last layer of the model, and then all layers are fine-tuned on the training set.

WP: One common approach for model compression while maintaining functionality is weight pruning [48]. In our experiments, we gradually increased the pruning rate from to .

AT: Following the adversarial training framework of Madry et al. [49], which is known to disrupt model decision boundaries, we leverage the approach from Wang and Chang [23] to train the piracy models. The training process is capped at 270 iterations. In each iteration, 128 new adversarial examples are generated via the FGSM method [50] and incorporated into the training set.

IN: As a preprocessing method to resist fingerprint detection, Input Noising [51] is employed. It operates by perturbing input images with additive Gaussian noise before the model processes them.

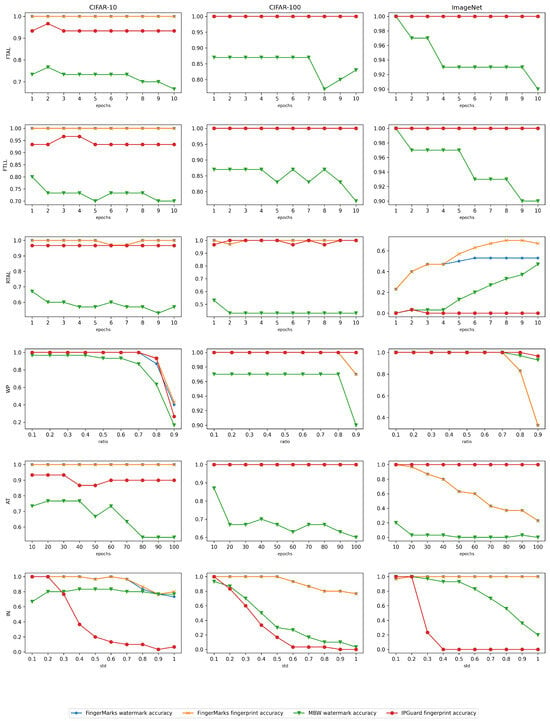

The experimental results are presented in Figure 2. From the results, it can be observed that FingerMarks achieves significant improvement in robustness compared to the baseline method, particularly in the RTAL, AT, and IN experiments.

Figure 2.

Robustness Assessment of Watermarks against Model Modification Attacks. To ensure fairness, both the proposed method and the comparative methods employ identical parameter settings for their respective watermarked models across all attacks.

In both the FTAL and FTLL experiments, it can be observed that the verification accuracy of FingerMarks across three datasets at different fine-tuning epochs is higher than that of MBW. The robustness performance of IPGuard is comparable to FingerMarks, indicating that FingerMarks can maintain robustness on par with or even superior to IPGuard when defending against fine-tuning attacks, thereby achieving improved robustness compared to MBW. This is further highlighted in the RTAL experiment, where the watermark verification accuracy of MBW drops significantly under retraining attacks. Under identical conditions across the CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and ImageNet datasets, FingerMarks achieves approximately 25%, 15%, and 5% higher verification accuracy compared to the MBW method, respectively.

In the WP experiment, it can be observed that even when 70% or even 80% of the weights are pruned, FingerMarks maintains a verification accuracy of nearly 100%, demonstrating its capability to withstand model compression attacks effectively. It is noteworthy that the other two methods, MBW and IPGuard, also exhibit commendable performance.

In the AT experiments, it can be observed that MBW demonstrates relatively poor robustness across all three datasets, showing high vulnerability to adversarial training attacks. In contrast, both FingerMarks and IPGuard exhibit strong performance on the CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets, maintaining stable verification accuracy without significant decline as training epochs increase. On the ImageNet dataset, IPGuard achieves optimal performance, whereas FingerMarks experiences a gradual degradation in verification accuracy with increasing training epochs.

The MBW method shows a progressive performance decline on the CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and ImageNet datasets. This occurs because, as the number of classes increases, the absolute difference between the two largest classes selected by MBW diminishes relative to other classes. As adversarial training progresses, the discriminative margins between different classes expand, gradually overshadowing the distinguishing margin of MBW. The IPGuard method, which employs the optimal distance parameter experimentally validated in the original study, maintains robustness across different datasets. FingerMarks incorporates some advantages of IPGuard but may sacrifice a degree of robustness due to the need to balance model classification accuracy and embedding efficiency when embedding multiple bits of information. For instance, on ImageNet, FingerMarks underperforms compared to IPGuard. Another critical factor is that, due to computational constraints, our fine-tuning on ImageNet utilized only a subset of the training data, preventing the full exploitation of the adversarial training advantages in the FingerMarks method.

The IN experiments fully demonstrate the superior robustness of FingerMarks. As Gaussian noise intensifies, the verification accuracy of FingerMarks remains largely unaffected. MBW shows acceptable performance only on the CIFAR-10 dataset, while its verification accuracy declines progressively on the other two datasets with increasing noise intensity. IPGuard is the most vulnerable to IN attacks among the three methods, with its fingerprint verification capability almost entirely compromised when the standard deviation (std) of Gaussian noise increases to 0.5.

The robustness of IPGuard, as a model fingerprinting method, is inherently affected by input perturbations since its fingerprints are generated through image manipulation. Consequently, it exhibits significant vulnerability under IN attacks. In contrast, FingerMarks demonstrates consistent resilience against IN attacks across all three datasets, which can be attributed to its adversarial training during watermark embedding that inherently builds resistance to image perturbations, while MBW shows acceptable performance on datasets with limited classes, its robustness declines markedly as the number of categories increases. This trend reveals that in multi-class scenarios, the model’s logits output becomes increasingly sensitive to image variations. Such sensitivity particularly impacts methods like MBW that rely on minimal adjustments to class outputs for watermark embedding, explaining its performance deterioration in more complex classification environments.

Based on the comprehensive comparative results of robustness experiments presented above, it can be observed that FingerMark demonstrates exceptionally strong robustness and effectively resists various attacks. This advantage primarily stems from its well-designed watermark data composition. The watermark dataset consists of both adversarial examples and minimally perturbed original samples that retain their original labels.

The first category—adversarial examples—is generated using a method inspired by IPGuard’s fingerprint extraction, which inherently provides a baseline level of robustness. Moreover, unlike model fingerprinting approaches that prohibit model modifications, FingerMark further enhances robustness through adversarial training during the embedding process. Another critical factor is that the labels of images in the trigger set are consistent with those of the adversarial examples. When the label derived from the encoding scheme matches the trigger set label, no model update is required. This allows the method to retain the advantages of model fingerprinting while improving embedding efficiency.

The second category—perturbed benign samples—can be viewed as data generated during adversarial training. Their robustness is reinforced through such training, and since the true labels of these samples align with the embedded watermarks, fine-tuning the model on them has minimal impact on classification accuracy. This also enables the model to converge rapidly during embedding.

In contrast, both MBW and IPGuard exhibit certain limitations in terms of robustness. MBW emphasizes embedding efficiency by slightly adjusting the two largest logits to rapidly alter model predictions. However, this excessive focus on efficiency makes the decision boundary highly vulnerable to adversarial perturbations. IPGuard, as a model fingerprinting method, does offer inherent robustness in its fingerprint data. Nevertheless, its constraint of leaving the host model unmodified imposes an upper bound on robustness. This highlights the flexibility of model watermarking approaches such as FingerMark, which can proactively enhance robustness through strategies like adversarial training.

An important additional advantage of FingerMarks, though not explicitly highlighted in the preceding three-dimensional analysis (performance, uniqueness, and robustness), is its unique capability to simultaneously embed multi-bit watermarks while utilizing the same trigger set to distinguish between relevant and irrelevant models. Notably, all experimental results across different datasets were achieved using this unified trigger set. This demonstrates that FingerMarks effectively integrates the strengths of both traditional black-box watermarking and multi-bit watermarking into a cohesive framework—a feature not achieved by any existing watermarking method.

6. Conclusions

This paper introduces FingerMarks, a novel black-box multi-bit DNN watermarking algorithm designed to address the dual challenges of model copyright authentication and distributed user tracking. The core innovation of FingerMarks lies in its strategic integration of model fingerprinting and watermarking principles through the construction of a shared trigger set. This design allows for efficient two-step verification upon collecting model predictions: the first step confirms the model’s intellectual property ownership, while the second traces the specific user to whom the model was distributed. This integrated approach provides a comprehensive protection mechanism, enabling model owners to not only assert their copyright but also identify the source of a leaked model in real-world deployment scenarios.

Extensive experimental evaluations confirm the superiority of FingerMarks over state-of-the-art methods across three critical dimensions. The algorithm exhibits high performance, achieving watermark embedding with minimal computational overhead and negligible impact on the host model’s accuracy. More importantly, it demonstrates effective uniqueness, successfully distinguishing between independently trained models and the watermarked host model, thereby preventing false ownership claims. Furthermore, FingerMarks showcases superior robustness, maintaining detectable watermark signals even after the model undergoes various attacks, including fine-tuning, pruning, and input noising. Despite being constrained by limited resources which prevented comprehensive testing on large-scale datasets, the conducted experiments sufficiently demonstrate the superiority of FingerMarks. It is anticipated that this work will catalyze further research into copyright protection for edge-deployed models, guiding future efforts toward developing watermarking solutions that offer even greater embedding efficiency and robust resilience against evolving threats.

While the current study demonstrates the effectiveness of our method on convolutional neural networks for image classification tasks, its generalization to other architectures and domains remains an open question. Future work will systematically evaluate the proposed approach across a broader spectrum of scenarios, including different model architectures (such as Transformers) and tasks beyond image classification (e.g., natural language processing and object detection). This will help establish the universality and applicability of the approach.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Q.L.; software, Q.L. and G.X.; validation, Q.L., G.X. and X.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.L.; supervision, Q.L. and X.Q.; funding acquisition, G.X. and X.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62431020.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this article are publicly available.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate the editors and reviewers of this journal for their valuable suggestions on this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- UrRehman, Z.; Qiang, Y.; Wang, L.; Shi, Y.; Yang, Q.; Khattak, S.U.; Aftab, R.; Zhao, J. Effective lung nodule detection using deep CNN with dual attention mechanisms. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavanasi, G.; Neven, D.; Arteaga, M.; Ditzel, S.; Dehaeck, S.; Bey-Temsamani, A. Enhanced Vision-Based Quality Inspection: A Multiview Artificial Intelligence Framework for Defect Detection. Sensors 2025, 25, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Irsoy, O.; Lu, S.; Dabravolski, V.; Dredze, M.; Gehrmann, S.; Kambadur, P.; Rosenberg, D.S.; Mann, G. BloombergGPT: A Large Language Model for Finance. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, K.; Tomar, G.S.; Parikh, A.P.; Papernot, N.; Iyyer, M. Thieves on Sesame Street! Model Extraction of BERT-based APIs. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.J.; Schiele, B.; Fritz, M. Towards reverse-engineering black-box neural networks. In Explainable AI: Interpreting, Explaining and Visualizing Deep Learning; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 121–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orekondy, T.; Schiele, B.; Fritz, M. Knockoff nets: Stealing functionality of black-box models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 4954–4963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramèr, F.; Zhang, F.; Juels, A.; Reiter, M.K.; Ristenpart, T. Stealing machine learning models via prediction APIs. In Proceedings of the 25th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 16), Austin, TX, USA, 10–12 August 2016; pp. 601–618. Available online: https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity16/technical-sessions/presentation/tramer (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Shankar, V. Edge AI: A Comprehensive Survey of Technologies, Applications, and Challenges. In Proceedings of the 2024 1st International Conference on Advanced Computing and Emerging Technologies (ACET), Ghaziabad, India, 23–24 August 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez Real, M.; Salvador, R. Physical Side-Channel Attacks on Embedded Neural Networks: A Survey. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, B.; Cheng, X.; Binh, H.T.T.; Yu, S. PoisonGAN: Generative Poisoning Attacks Against Federated Learning in Edge Computing Systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 3310–3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroux, S.; Simoens, P.; Lootus, M.; Thakore, K.; Sharma, A. TinyMLOps: Operational Challenges for Widespread Edge AI Adoption. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium Workshops (IPDPSW), Lyon, France, 30 May–3 June 2022; pp. 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, Y.; Nagai, Y.; Sakazawa, S.; Satoh, S. Embedding watermarks into deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM on International Conference on Multimedia Retrieval, Bucharest, Romania, 6–9 June 2017; pp. 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Rouhani, B.D.; Fu, C.; Zhao, J.; Koushanfar, F. Deepmarks: A secure fingerprinting framework for digital rights management of deep learning models. In Proceedings of the 2019 on International Conference on Multimedia Retrieval, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 10–13 June 2019; pp. 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adi, Y.; Baum, C.; Cisse, M.; Pinkas, B.; Keshet, J. Turning your weakness into a strength: Watermarking deep neural networks by backdooring. In Proceedings of the 27th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 18), Baltimore, MD, USA, 15–17 August 2018; pp. 1615–1631. Available online: https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity18/presentation/adi (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Le Merrer, E.; Perez, P.; Trédan, G. Adversarial frontier stitching for remote neural network watermarking. Neural Comput. Appl. 2020, 32, 9233–9244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Li, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X. Watermarking for Stable Diffusion Models. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 35238–35249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, H.; Lu, S. FedCRMW: Federated model ownership verification with compression-resistant model watermarking. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 249, 123776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, T.; Ma, Y.; Zheng, N.; Wu, H.; Chen, Y.; Xu, M.; Luo, X. A novel model watermarking for protecting generative adversarial network. Comput. Secur. 2023, 127, 103102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Feng, F.; Zhang, G.; Xu, L. Robust and Imperceptible Watermarking Framework for Generative Audio Models. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2025, 32, 3196–3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Hu, Q.; Liu, G.; Ma, X.; Chen, F.; Hassan, M.M. AFA: Adversarial fingerprinting authentication for deep neural networks. Comput. Commun. 2020, 150, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukas, N.; Zhang, Y.; Kerschbaum, F. Deep Neural Network Fingerprinting by Conferrable Adversarial Examples. arXiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Jia, J.; Gong, N.Z. IPGuard: Protecting intellectual property of deep neural networks via fingerprinting the classification boundary. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Virtual Event, 7–11 June 2021; pp. 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chang, C.H. Fingerprinting Deep Neural Networks—A DeepFool Approach. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Daegu, Republic of Korea, 22–28 May 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Li, S.; Chen, G.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, H.; Xue, M. Fingerprinting Deep Neural Networks Globally via Universal Adversarial Perturbations. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 13420–13429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Zhong, S.h.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y. Intellectual Property Protection for Deep Models: Pioneering Cross-Domain Fingerprinting Solutions. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2025, 20, 3587–3600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, A.; Lu, Z.; Xie, R.; Xue, M. VeriDIP: Ownership of Deep Neural Networks Through Privacy Leakage Fingerprints. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2024, 21, 2568–2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Rouhani, B.D.; Koushanfar, F. BlackMarks: Blackbox Multibit Watermarking for Deep Neural Networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.00344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, W.; Barni, M. Universal BlackMarks: Key-Image-Free Blackbox Multi-Bit Watermarking of Deep Neural Networks. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2023, 30, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroux, S.; Vanassche, S.; Simoens, P. Multi-bit, Black-box Watermarking of Deep Neural Networks in Embedded Applications. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Seattle, WA, USA, 17–18 June 2024; pp. 2121–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podilchuk, C.; Delp, E.J. Digital watermarking: Algorithms and applications. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2001, 18, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, D.; Liao, J.; Ma, Z.; Fang, H.; Zhang, W.; Feng, H.; Hua, G.; Yu, N.H. Robust Model Watermarking for Image Processing Networks via Structure Consistency. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 6985–6992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, M.; Wei, D.; Chen, Z.; Fang, X.; Chau, M. Watermarking Large Language Models: An Unbiased and Low-risk Method. In Proceedings of the 63rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Vienna, Austria, 27 July–1 August 2025; pp. 7939–7960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, H.; Lu, S. Securing IP in edge AI: Neural network watermarking for multimodal models. Appl. Intell. 2024, 54, 10455–10472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.Y.; Pan, S. BiMark: Unbiased Multilayer Watermarking for Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Forty-Second International Conference on Machine Learning, Vancouver, ON, Canada, 13–19 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, W.; Li, W. Reliable Multi-bit Watermark for Large Language Models via Robust Encoding and Green-Zone Refinement. In Advanced Intelligent Computing Technology and Applications; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 148–159. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, A.; Hoover, A.; Schoenbach, G. Watermarking Language Models for Many Adaptive Users. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Francisco, CA, USA, 12–15 May 2025; pp. 2583–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Wu, H. Verifying Integrity of Deep Ensemble Models by Lossless Black-box Watermarking with Sensitive Samples. In Proceedings of the 2022 10th International Symposium on Digital Forensics and Security (ISDFS), Istanbul, Turkey, 6–7 June 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H. Robust and Lossless Fingerprinting of Deep Neural Networks via Pooled Membership Inference. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 24th Int Conf on High Performance Computing & Communications; 8th Int Conf on Data Science & Systems; 20th Int Conf on Smart City; 8th Int Conf on Dependability in Sensor, Cloud & Big Data Systems & Application (HPCC/DSS/SmartCity/DependSys), Hainan, China, 18–20 December 2022; pp. 1042–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, D.; Mishra, N. Invisible Traces: Using Hybrid Fingerprinting to identify underlying LLMs in GenAI Apps. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosavi-Dezfooli, S.M.; Fawzi, A.; Frossard, P. DeepFool: A Simple and Accurate Method to Fool Deep Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2574–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Hinton, G. Learning multiple layers of features from tiny images. In Handbook of Systemic Autoimmune Diseases; 2009; Available online: http://www.cs.utoronto.ca/~kriz/learning-features-2009-TR.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Russakovsky, O.; Deng, J.; Su, H.; Krause, J.; Satheesh, S.; Ma, S.; Huang, Z.; Karpathy, A.; Khosla, A.; Bernstein, M. ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2015, 115, 211–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 1–9. Available online: https://www.cv-foundation.org/openaccess/content_cvpr_2015/papers/Szegedy_Going_Deeper_With_2015_CVPR_paper.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. Available online: https://openaccess.thecvf.com/content_cvpr_2016/papers/He_Deep_Residual_Learning_CVPR_2016_paper.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2015, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2019, NeurIPS 2019, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; Wallach, H.M., Larochelle, H., Beygelzimer, A., d’Alché-Buc, F., Fox, E.B., Garnett, R., Eds.; 2019; pp. 8024–8035. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2019/file/bdbca288fee7f92f2bfa9f7012727740-Paper.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Lukas, N.; Jiang, E.; Li, X.; Kerschbaum, F. SoK: How Robust is Image Classification Deep Neural Network Watermarking? In Proceedings of the 43rd IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, SP 2022, San Francisco, CA, USA, 22–26 May 2022; pp. 787–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Pool, J.; Tran, J.; Dally, W. Learning both Weights and Connections for Efficient Neural Network. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–12 December 2015; Cortes, C., Lawrence, N., Lee, D., Sugiyama, M., Garnett, R., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2015; Volume 28. [Google Scholar]

- Madry, A.; Makelov, A.; Schmidt, L.; Tsipras, D.; Vladu, A. Towards Deep Learning Models Resistant to Adversarial Attacks. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2018, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 April–3 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Shlens, J.; Szegedy, C. Explaining and harnessing adversarial examples. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zantedeschi, V.; Nicolae, M.I.; Rawat, A. Efficient Defenses Against Adversarial Attacks. In Proceedings of the AISec ′17: 10th ACM Workshop on Artificial Intelligence and Security, Dallas, TX, USA, 3 November 2017; pp. 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).