Abstract

The convergence of Internet of Things (IoT), embedded microcontrollers, and robotics has significantly transformed industrial and service applications under the Industry 5.0 paradigm. IoT-enabled automation not only reduces human intervention but also improves system efficiency, safety, and adaptability across multiple domains. The growing integration of automation technologies in manufacturing lines has significantly reduced human intervention while improving productivity and operational safety. Robotic arms play a crucial role in modern industrial environments, particularly for repetitive, hazardous, or precision-demanding tasks. This study presents a cost-effective robotic arm system for product selection, sorting and processing in automated production lines. The system operates in both automatic and manual modes and utilizes an ESP32-based controller, radio frequency identification (RFID) modules, and low-cost sensors to identify and transport products on a conveyor. A mobile, IoT-enabled interface provides remote real-time monitoring and control, while integrated safety mechanisms, current-voltage protections, and emergency stop circuitry enhance operational reliability. Using cost-effective components to reduce total cost, the system has been successfully validated through experiments to reduce labor dependency and operational errors, proving its scalability and economic viability for industrial automation. Compared to similar systems, this study presents an Industry 5.0 approach for low-cost IoT-based automated production lines.

1. Introduction

The convergence of Internet of Things (IoT), embedded controllers, and robotics is reshaping automation across energy, manufacturing, health, agriculture, and smart-home domains. Low-cost microcontroller structures, especially the ESP32, provide IoT-enabled, real-time observability and data-driven control, while edge computing and lightweight artificial intelligence (AI) provide autonomy for constrained devices. In energy systems, reviews of AC microgrids highlight how IoT-enabled Energy Management Systems (EMS) and machine learning (ML) support stability, predictive optimization, and resilience within decentralized architectures [1]. An ESP32-based, artificial intelligence-supported virtual caregiver framework can be integrated into home automation. Automation can be used to create an IoT-based life support system that synthesizes information collected for home patient assessment, emergency response, and encouraging physical and cognitive exercise [2].

ESP32 is preferred for algorithm applications thanks to its integrated Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and dual-core Microcontroller Unit (MCU). Small-scale project implementations have shown that ESP32 can run computer vision projects with competitive error rates even when working with limited resource budgets [3]. Embedded real-time object detection is also seen in various studies with autonomous applications [4]. ESP32 is preferred for multi-sensor platforms. Wearable biosensing arrays using multiple ESP32 boards show high compatibility with commercial sensors across 18 physiological indicators [5]. ESP32 is also used in practical control and monitoring systems. For example, it is used in IoT photovoltaic systems to perform cleaning and cooling tasks [6]. It enables physiotherapy sleeves with Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU)-based motion tracking [7] and CO2 monitoring over Wi-Fi in smart home systems [8].

In a control study using an ESP32-based control board, a robot capable of omnidirectional motion via active disturbance rejection was demonstrated to achieve robust trajectory tracking. Tracking was improved under potential disturbances and model uncertainty, and an observer control structure was provided using Lyapunov stability analysis [9]. Multi-Agent Systems (MAS) offer solutions for applications such as logistics, wide-area sweeping and cleaning, and unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) surveillance by combining task scheduling with pathfinding. One proposed method utilizes an intelligent planner that plans the optimal route for area coverage by multiple agents, and a central scheduler that assigns tasks according to different priority queues. In a prototype study, a simple robot is driven in a controlled environment using readily available IoT components. Image processing is used to both predict the expected reward for the planned path and to collect feedback after task execution [10]. ESP32’s integrated Wi-Fi and Bluetooth support enables interoperability in the IoT by combining different protocols into a single, low-cost edge controller. To reduce the latency and scalability issues of cloud-centralized architectures, minimizing data exchange as much as possible provides speed and energy efficiency for constrained IoT applications. At the application level, this ESP32-based approach facilitates the deployment of flexible, scalable, and budget-friendly IoT solutions in various fields [11]. In the context of the rapid development of the Tiny Machine Learning approach in edge computing and IoT devices, the study investigated the combined use of multiple model compression techniques on a custom 1D CNN model for the Electrical Impedance Tomography-based Hand Gesture Recognition scenario. Significant gains in execution speed and energy efficiency were achieved on edge devices with limited processing power. While power consumption provides significant gains for different platform microcontrollers, an approximately 94% speed increase was achieved on the ESP32-based board [12].

Identification and low-cost sensing are increasingly important in IoT robotic applications and RFID-tagged crop tracking systems. Printed, flexible RFID tags measure soil moisture, oxygen, and temperature. They can be read by robots in the field, enabling scalable, low-cost designs for agricultural monitoring [13]. Extensive research on smart agriculture has led to the adoption of IoT robotic drones as a way to increase yields while reducing environmental impact [14].

IoT studies are impacting industrial reliability and predictive maintenance beyond identification. Modular, end-to-end off-the-shelf sensing platforms offer innovative approaches with expandable sensor input/output (I/O), and low-latency processing times [15]. Computer vision research in warehouse automation is exploring prototypes for high-performance distribution robots, edge AI hardware, autonomous vehicles or robotic arms, and standardized benchmarks [16]. In energy storage, long-range active battery management system (BMS) monitoring, cloud-based voltage, current, charge status and health status monitoring with simulation-assisted power modeling for long-range, low-bit and high-speed communication can be designed with low-cost microcontrollers [17].

Industrial process monitoring demonstrates the scope of IoT. An IoT solar dryer with forced convection, load cell mass tracking, and imaging supports remote monitoring while improving the drying quality of agricultural products [18]. An open-source 3D anemometer with environmental sensors enables indoor airflow and indoor air quality characterization with precise angular/velocity resolution, supporting health-conscious ventilation assessment [19]. Localized weather stations combining IoT sensing, long-range backhaul, and incremental machine learning can offer site-specific designs that can outperform general application programming interfaces for micro-scale decision-making [20].

In line with the increasing demands and requirements, low power and energy efficiency have become the most important parameters in all fields of study. Flexible thermoelectric generators, adjusted via generation parameters, can harvest waste heat to power autonomous IoT nodes for industrial monitoring with a positive energy balance [21]. In a study investigating the effectiveness of virtual reality interfaces for controlling robotic arms in Internet of Things (IoT) education, a 5-degree-of-freedom robotic arm equipped with MG996R servo motors and controlled via an Arduino microcontroller and Raspberry Pi wireless communication was examined using both control methods. Its controllability and user interface interactions were demonstrated through hands-on experiments by engineering students [8]. In the smart home and security field, edge AI frameworks reduce bandwidth and storage space by detecting motion on the device and providing low-latency alerts. Local IoT applications demonstrate cost-latency gains compared to cloud data streaming in various applications [22]. ESP32-class edge devices, along with their low-cost, scalable, and adaptable features, are interoperable with RFID-tagged product tracking and IoT designs, making them a preferred choice for robotics and automation solutions. A flexible robotic arm design can be implemented for product feeding and sorting in production lines. By combining ESP32-based control, RFID product identification, and IoT remote control, they can create desired customer-centric designs [13], directly enable collaborative planning [10], edge interoperability [11], and provide compatibility with energy-aware applications [1,6,21,23].

During industrial production, fast and accurate product sorting and separation remains a significant challenge. Detection and reliable removal of defective or substandard products on the line can be addressed by programmable logic controllers (PLCs) [24] and computer-based robotic arms, providing high-throughput sorting with minimal errors. A cable-driven facade cleaning robot powered by an ESP32 module can be designed [25], demonstrating how low-cost, connected microcontrollers can support robust field operations. The manipulation tasks to be performed in robotic arm applications [26] are considered, and the controller structures and system designs to be used are selected. By considering a comparative analysis of the ESP32 with competing microcontrollers, the hardware capabilities, basic functions, and programming aspects can be described in detail. As a real-world application, a portable wireless oscilloscope and mobile interface application based on the ESP-WROOM-32 can be implemented [27]. To generate profit, an Intelligent Robotic Arm (ARO) equipped with sensors can be designed as a food processor and have the ability to cook food. It can use OpenCV and Python 3.11 to recognize objects, identify containers and ingredients, and then autonomously pick and place them. It can be used in homes with simple structures or in industrial kitchens with more complex structures [28]. Low-cost ESP32 and related microcontrollers with measurement and data processing capabilities can be used for robotic tasks. Data can be transferred to higher-level systems by integrating with IoT modules and smart sensors [29]. With a low-cost ESP32 microcontroller, a bioreactor can be transformed into a high-end device with IoT support for biochemical studies. A pilot anaerobic bioreactor requires daily monitoring and regular and frequent maintenance. Evaluating anaerobic digestion performance requires remote data collection and online monitoring of various parameters. All of these studies can be accomplished using low-cost ESP32 and IoT technology [30]. The design and implementation of ESP32-based IoT devices demonstrate the flexibility, real-time control capability, and cost-efficiency offered by such embedded platforms [31]. CNN-MLP-based configurable robotic arms show that machine learning can enhance adaptability, precision, and performance in smart agriculture applications [32]. The integration of BIM–IoT with autonomous mobile robots highlights the potential of IoT-enabled robotic solutions for precise positioning and autonomous operation in complex industrial environments [33]. Wheelchair-mounted robotic systems emphasize the importance of user-centric and low-cost robotic solutions for assisting patients with upper-limb impairments [34]. The use of simulation and virtual commissioning approaches in robotic automation illustrates how system performance can be optimized while reducing deployment risks [35]. Taken together, these studies show that ESP32 and IoT-based embedded controllers are increasingly adopted in low-cost, scalable, and versatile robotic applications, providing a strong foundation for the proposed robotic arm system.

In this study, an IoT-based, user-friendly, adaptable, low-cost robotic arm and conveyor design that increases efficiency and reduces human intervention and errors in industrial production workflows such as product feeding, sorting and packaging is presented. In automatic mode, products moving on a conveyor are guided using predefined RFID tags and transported to designated interaction points by the robotic arm. This design ensures that products are quickly and accurately sorted according to label information and delivered to their destination. The system is supported by a second manual mode, which allows operators to monitor direct controls and record robot arm position information when necessary. Manual mode can be used by individual operators if necessary, and it also records the necessary parameters for the robotic arm and peripherals for automatic mode. The system incorporates an emergency stop circuit that automatically shuts down in cases of excessively low voltage, high current, reaching axis limits, and uncertainty. The design includes IoT connectivity, enabling remote monitoring, tracking, and rapid response in the event of anomalies. Its low cost, IoT design capabilities, and Wi-Fi and Bluetooth modules offer flexible design possibilities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. System Architecture

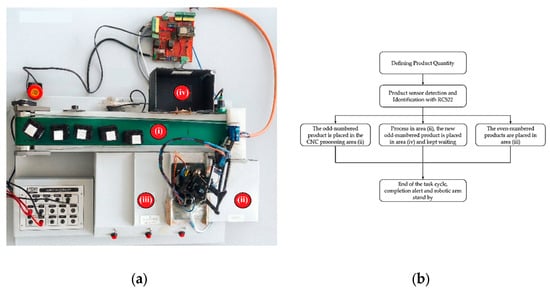

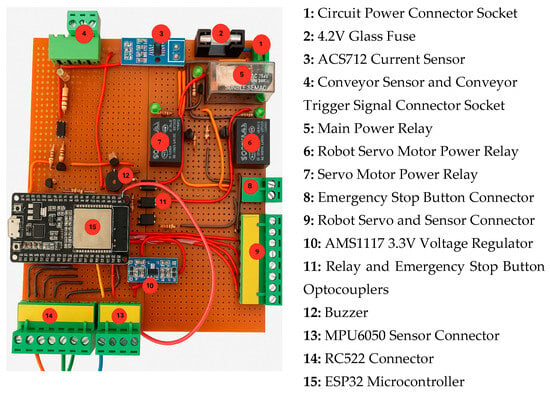

ESP32’s embedded IoT and web interface allow the system to be quickly adapted to meet industrial needs. The designed system provides unmanned, fast, and error-free product feeding and sorting capabilities for production lines. Considering similar needs in industrial environments, the system’s code structure and hardware are designed for a scenario involving product processing and rapid product sorting on a CNC line. The 4-Degrees-of-Freedom (4-DOF) robotic arm also provides access to four interaction points: (i) a conveyor pickup point, (ii) a CNC station, (iii) Drop-off point-1, and (iv) Drop-off point-2. Areas (i), (ii), (iii), and (iv) on the conveyor are marked with red dots in Figure 1a. Area (iii) is reserved for products whose CNC processing has been completed or that will not be processed, and area (iv) is reserved for waiting for products undergoing CNC processing. The 4-Degrees-of-Freedom (4-DOF) robotic arm is mounted on a fixed base and automatically picks up labeled products from the conveyor area (i) and transports them to the required areas. The robotic arm automatically repeats the product pickup positions in area (i) and drop-off positions in other areas, in line with the information defined on the product labels.

Figure 1.

(a) Robotic Arm and Conveyor (b) System Operation Flowchart.

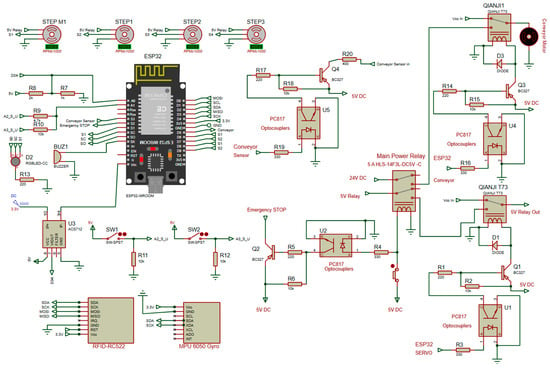

All detection, actuation, and safety interlocks are handled by the ESP32-based controller. Initial product detection is performed by a Pepperl & Fuchs retroreflective sensor, codenamed GLV18-55/73/120, which reads and selects products on the conveyor. The 24 V sensor is connected to the ESP32 controller using optocouplers, resistors, and transistors. The product ID is then retrieved by the RC522 reader. The product coming from the conveyor is detected and its ID is read. After initial detection, the RC522 RFID reader transmits the product’s tag information and (i) its location to ESP32. The controller operates relay-isolated outputs for the conveyor and servo power lines and monitors bus current and voltage to enforce safe operating limits. An emergency stop button (E-Stop) can disconnect power to the hard-wired actuator regardless of the firmware status. As shown in Figure 2, optocouplers on the designed Printed Circuit Board (PCB) isolate external signals (e.g., sensor outputs and emergency stop) from the microcontroller area. The ESP32 study provides low-cost, IoT-enabled control features that provide real-time data interfaces, manual operation, and audible alarms. The flowchart of the system operation is presented in Figure 1b.

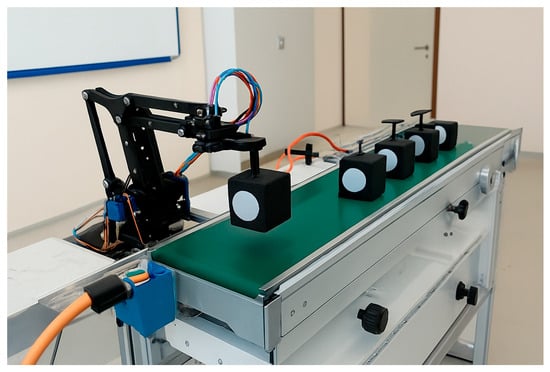

Figure 2.

The Proteus-Based Circuit Diagram of Our Selected System Model.

In automatic operation, after the RFID tag on the conveyor is read, a rule-based routing policy is applied. Products are transported directly to the CNC station, area (ii), for processing based on their tag IDs, or, in the case of CNC-processed products, sent to Drop Point 2, area (iv), for waiting. While a CNC job is in progress, the ESP32 controller continues monitoring operations and transfers newly arrived products to the relevant areas. It returns to the standby mode to monitor unloading and loading operations. The robotic arm repeats these operations until predefined counting targets for “processed” and “sorted” products are reached based on the predefined number of incoming products and the RFID tag information. When the tasks for the defined products are completed, the ESP32 emits an audible alert and enters a safe standby state. Manual mode allows the same hardware to be used for setup, calibration, and special transfers via the web user interface. Both modes are designed with all security locks enabled.

The developed hardware and software architecture holistically separates the layers of detection, decision-making, and action. A retroreflective sensor and RFID are used for detection. The software, developed via ESP32, prioritizes the CNC station as required by the scenario, accelerating the decision-making process. Motion, control, and physical operations are provided by the conveyor and robotic arm. Safety features within the system are provided at relevant levels in both hardware and software. The hardware includes an emergency stop button, power relays, and fuses. Furthermore, safety parameters provided by the software include emergency situations such as overcurrent, overvoltage, alarms, and limit sensors. The electrical and control connections necessary for the integration of the conveyor with the robotic arm have been carefully designed, and an emergency stop button has been added. The retroreflective sensor, initially positioned on the conveyor, signals the “ready to read” status. The RC522 RFID reader sensor waits for the product to come within detection range to read the product tags on the belt. When the RFID tag is read, the conveyor stops. The product is picked up by the robotic arm for transport to the designated area. Conveyor and servo power lines are switched and isolated via relays. The conveyor and servo power lines are switched and isolated via relays. Before proceeding to the physical installation and assembly phase, the planned layouts for the ESP32 controller and robotic arm were simulated in Proteus and Factory I/O environments using the workflow. The simulation studies facilitated the physical integration of the study, including wiring, component alignment, product movement timing, and safety interlocks. The Proteus circuit diagram for the simulation study is shown in Figure 2. To reduce the complexity of the circuit connections on the Proteus, the inputs and outputs are labeled and shown in Figure 2.

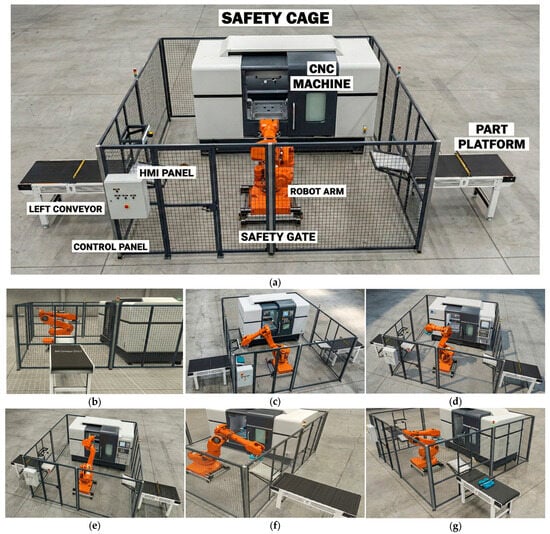

The virtual commissioning phase of the production cell was conducted using Factory I/O (Figure 3). The interaction between the conveyor line and the robot manipulator was pretested by mapping sensor-actuator I/O labels to PLC logic, scheduling the task flow, and verifying safety interlocks. Conveyor speed and buffer capacities were parametrically swept in the scenarios, assessing the robot’s accessibility against product arrival distributions, grasp/release delays, stop-start synchronization, and potential collision risks. Simulated cycle times, queue lengths, and station utilization rates were determined. The findings provided the basis for refining the wiring plan, sensor placement, and mission times prior to physical installation, significantly reducing trial-and-error time in the field.

Figure 3.

Three-dimensional Modeling of the System in Factory I/O Program (a) Overall System View (b) Movement of the product on the conveyor system (c) Pickup of the product by the robotic arm (d) Transporting the product to the processing point (e) The product being placed at the CNC station (f) Picking up the product from the CNC station (g) The product being placed at the exit point.

The system can be used in manual or automatic modes during routine operation. In manual mode, the robotic arm joint movements and conveyor control provide the user with parametric data for setup and calibration via the web interface. This allows for automated design opportunities for differentiated production lines using the recorded parameters. In automatic mode, once the number of parts to be sorted and processed is entered, the controller initiates the product sorting process with the conveyor movement.

The controller reads each tag information arriving at the robotic arm from the conveyor and applies the defined routing rule: in the scenario, it was created for five defined product IDs. Odd-numbered IDs in the generated catalog are sent directly to area (ii) for CNC processing, while even-numbered IDs are transferred directly to area (iii) without any CNC processing. If another odd-numbered part arrives during a CNC job, the robot either waits, taking into account the completion time of the CNC task, or directs the part to the waiting area (iv). It then returns to complete the CNC’s unloading/loading cycle. This cycle continues until the target quotas are reached. When the quotas are full, the system gives an audible warning and goes into safe standby mode.

2.2. System Hardware

2.2.1. ESP32 Microcontroller

In the implemented conveyor-robot system, decision-making, communication with field devices, and security interlocking are performed by an ESP32-based controller. Thanks to built-in Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, sufficient processing power, and a large number of peripherals, ESP32 can host both an embedded IoT web interface and successfully handle real-time I/O tasks with low latency. In the dual-core architecture, one core is dedicated to user interface communication, while the other is dedicated to time-critical functions such as servo drives, sensor sampling, and relay control [26].

The product recognition and detection layer consists of an RFID reader positioned at the end of the conveyor. Adhesive NTAG215 tags are easily integrated into the product; identification data is read by an RC522 RFID reader via Serial Peripheral Interface (SPI) and transmitted to the controller with a typical detection range of 1–5 cm [36]. To synchronize the reading timing, a GLV18-55/115/120 retroreflective sensor, placed at the end of the conveyor before the RC522, is triggered when the part reaches the “readable” position. Once the part reaches this position, the conveyor is stopped, ensuring the safe transfer of the part to the target area. Robotic arm movements are monitored using X/Y/Z rotation and acceleration data transmitted to ESP32 via an Inter-Integrated Circuit (I2C) connection from an MPU6050 accelerometer-gyroscope module integrated into the axes. This data is used to verify the joint tip angle, monitor stabilization during rapid transitions, and apply soft limits [37]. The power and safety architecture is relay-based: ESP32 first activates the main power relay; the servo feed and conveyor relays can only be activated when the main relay is active. This means that when the emergency stop button is pressed, all actuators are immediately de-energized, regardless of software. Signals from field devices with NPN outputs are isolated and transferred to the ESP32 input pins via PC817 optocouplers driven by the BC327 (PNP). The same driver structure is used for the relay coils to ensure ESP32 secure signal reading. The ACS712 current sensor similarly monitors the total line current; if the threshold is exceeded, the controller triggers the relevant relay, recording this event for security purposes, and generating an audible alarm [38]. Voltage reduction is achieved from the 5V DC voltage line for the ESP32 input signals and power supply using an AMS1117-3.3V regulator. This separation reduces the risk of voltage drop and overheating, contributing to stable ESP32 operation [39]. In summary, the ESP32-based controller integrates RFID-based product identification and retroreflective sensor location sensing, IMU-supported angular/positional status monitoring, relay-based power-off safety, and IoT-based Human Machine Interface (HMI) components to create a secure, scalable, and real-time control infrastructure.

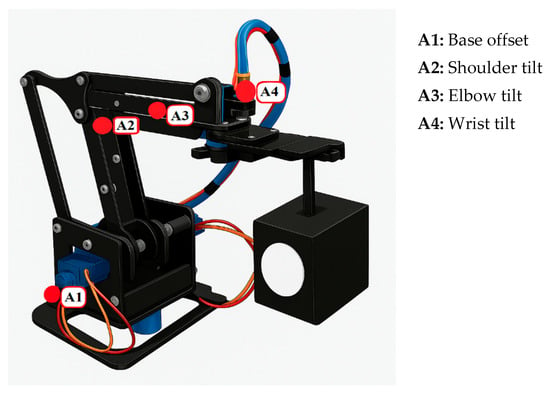

2.2.2. Mechanical Design of ARM

The robotic arm is constructed from laser-cut acrylic Polymethyl Methacrylate (PMMA) mounting plates with aluminum mounting brackets on a rigid base aligned with the conveyor axis. The robot arm uses SG90 servo motors, which can be controlled via a PWM signal and rotate through 180 degrees. The robot arm also uses limit switches to send event notifications to the ESP32, and an MPU6050 gyroscope and acceleration sensor are located on the top of the robot. The MPU6050 gyroscope and acceleration sensor, communicating via I2C, are used to control servo drift and obtain the robot’s current rotation angles. These sensors are integrated into the system to monitor servo error conditions. As shown in Figure 4, it consists of four joints: base offset (A1), shoulder tilt (A2), elbow tilt (A3), and wrist tilt (A4). A parallel-jaw gripper with compliant pads can grip box-shaped objects. The grip width is set during setup and applied with a short dwell stroke in automatic cycles. Each axis is protected by mechanical hard stops and limit switches, which also allow for return to standby position. The cables are secured with loose loops at their connection points, preventing any possible restrictions on the robotic arm’s movement. Electromagnetic interference is reduced by physically isolating the high-current servo wiring from the RFID reader by following the connection centerlines [37].

Figure 4.

A1–A4 Joints and Gripper Mechanism of the Robotic Arm.

2.2.3. Electronics and Power

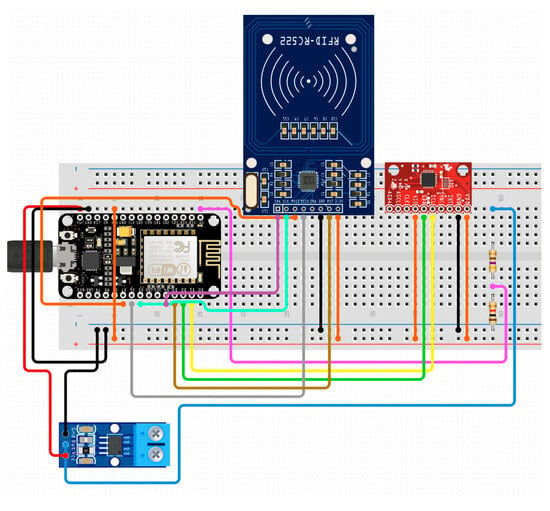

A custom control PCB was designed and is shown in Figure 5. The PCB houses the ESP32, AMS1117 3.3V regulation, ACS712 current sensing, and three relays: main power, servo power, and conveyor driver. External signals are isolated via PC817 optocouplers; the reverse protection switch is driven by transistors with relay coils. The main relay shuts off the downstream power supplies. Thus, an emergency stop immediately de-energizes the actuators, regardless of the firmware “safety relay” logic. Separate 5V and 12V DC lines are designed to power the servos, conveyor motor, and relays. Star grounding is used to minimize coupling. All field elements can be individually connected to the circuit to simplify troubleshooting should any circuit problems occur. Connectors are regularly inspected and labeled for maintenance and quick replacement. The PCB layout of the entire circuit and associated components is numbered and presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Assembled controller PCB, labeled I/O.

2.2.4. Functional Safety and Interlocks

Safety is ensured at both hardware and software levels. The hardware structure includes a mushroom-type emergency stop, a glass fuse for the relevant line, a main relay cutout, axis limit switches, and protected pinch points. When the emergency stop button is pressed, the system shuts down without needing any confirmation from ESP32. The double-contact main relay ensures the safety of the entire system. This relay stops both the conveyor and the robot’s servos. Thanks to the double-contact structure of the main relay, the outputs used by the ESP32 to control other smaller relays pass through the main relay’s contacts. When the main relay is closed, the other smaller relays are disabled, preventing both the robot’s servos and the conveyor from operating, causing an electrical lockout of the system. The PCB and related details are shown in Figure 5.

2.2.5. Sensing and Identification

NTAG215 RFID tags are used to identify which product the robotic arm is processing and which action to perform. RFID tags must be pre-attached to the products and identified by the tags. The RC522 reads the IDs from a distance of 1–5 cm when the products reach the reading window. A retroreflective sensor on the front of the RC522 marks the “ready to read” position and synchronizes the data acquisition timing. An MPU6050 IMU mounted near the robotic arm’s wrist provides angular rate/pitch control for diagnostics and soft-limited motion verification during rapid traverses. All sensor input signals are processed through ESP32 software to provide control.

2.2.6. PCB Design of Control Board

Prior to modeling and prototyping, the controller and work cell workflow were tested in simulation programs to reduce installation errors. Circuit diagrams, signal input/output, and field element integrity simulations were performed using Proteus (Figure 2), and structural operation and timing modeling were performed using Factory I/O (Figure 3). Simulation studies have significantly reduced the problems that may be encountered during physical design. Based on these models, a custom controller PCB was designed and the conveyor and robotic arm were assembled. The elements and connection points on the designed PCB are marked with numbers 1–15 and are shown in Figure 5.

The microcontroller on the PCB control board is the ESP32 processor (15). Circuit elements such as the ACS 712 current sensor, power relays, buzzer, and optocoupler, along with their connection sockets, are shown on the PCB in Figure 5. The main input level to the circuit is provided by power (1). In section (2), a glass fuse is used for overcurrent protection, and in section (3), a current sensor is used to detect overcurrent. The conveyor sensor and conveyor trigger signal connector sockets that enable the forward movement of the conveyor are numbered (4). The main power relay is indicated by number (5). The servo motor power of the conveyer relay and servo motor power relay of the robotic arm are shown with numbers (6) and (7), respectively. Emergency Stop Button Connector and Robot Servo and Sensor Connectors (8) and (9), respectively. The ESP32 controller AMS1117 3.3V Voltage Regulator (10) is shown as number. Optocoupler circuits are used to prevent the effects of high current and voltage at the connection points affecting the ESP32 microcontroller and possible signal interference and are shown with connection point (11). Number (12) indicates the buzzer component which is used to alert the user in emergency situations. Number (13) indicates the Robotic arm MPU6050 Sensor Connector and number (14) indicates the RC522 connector which reads RFID tags on products and transmits them to the ESP32 port. The ESP32 output is connected first to control the contacts of the relay (5). After that (6) and (7) are connected to the ESP32 output. This way, even if the ESP32 output is received, if relay (5) is closed, the other relays are not activated. The purpose of this connection is to shut down the system without requiring a microcontroller when the emergency stop button is pressed.

Figure 6 shows the conveyor and robotic arm. An MPU6050 accelerometer/gyroscope sensor was used for precise movement on the robotic arm.

Figure 6.

Robotic Arm and Feeding Unit Structural Design.

An ESP32-based test setup was created on Circuit.IO, and connections and initial verification tests were performed for the RC522 RFID card reader, ACS712 current sensor, and MPU6050 accelerometer/gyroscope, and Figure 7 is presented.

Figure 7.

ESP32 Microcontroller, RC522 RFID Card Reader, ACS712 Current Sensor, MPU6050 Accelerometer and Gyro.

In the schematic, the MPU6050 is connected to ESP32 via the I2C bus (SDA/SCL). The RC522 is integrated with the SPI (SCK, MOSI, MISO, SS). The ACS712’s analog output is routed to the ESP32’s ADC pin, and all modules operate with a common ground reference. The setup was used to verify wiring integrity and pin mappings, and to test RFID tag reading, current measurement, and axis inertial data flow before deployment in the field, providing a reliable preliminary validation for hardware integration.

As in the Circuit.io study, the system’s circuit designs were implemented by dividing it into subunits and then presenting it as the Proteus circuit shown in Figure 2. The notable subunits consist of relay and optocoupler elements. The relay circuits provide both power line security and logic-power separation. As detailed in Figure 2, the HLS-14F3L-DC5V-C (DPDT) “Main Power Relay” is driven by isolating the command from the ESP32 via the PC817 optocoupler. The optocoupler is limited to LED R4 = 330 Ω and has a value of 3.3 V~6.36 mA. PC817 transistor Q2 (BC327) supplies current to the 5 V coil, switching the driver; a diode is added to the coil to suppress back-EMF. Two poles of the Main Power Relay switch the 24 V distribution, while the second pole is reserved for a conveyor line. The circuit diagram for the conveyor line is identical to the Servo Relay circuit. The QIANJI T73 servo relay in Figure 2 is similarly driven by the PC817 optocoupler and Q1 (BC327). R1 = 220 Ω determines the base current, and R2 = 10 kΩ determines polarity stability against leakage current. Therefore, if Output 2 is not active, the QIANJI T73 coil cannot be energized. The servo stage cannot operate without the main power circuit being activated, thus providing fail-safe locking. This structure provides galvanic isolation, EMI and back-EMF suppression, and sequential switching between the ESP32 and the 24 V power stage.

2.3. System Software

The code structure of the robotic arm automation project utilizes the capabilities of the ESP32 microcontroller, combining a web-based IoT interface with physical control. The overall code structure was developed in the Arduino IDE environment, organized around standard Arduino functions, but customized to take advantage of the ESP32’s dual-core architecture.

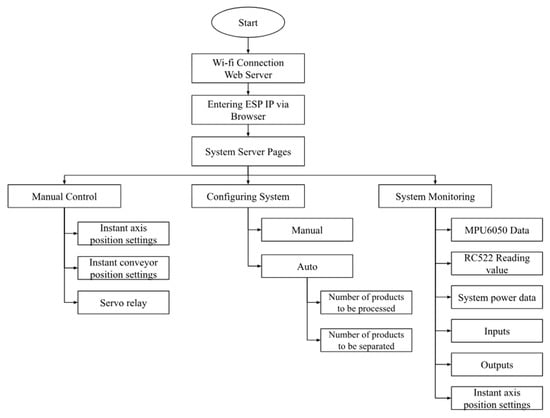

The IoT Design and Integration constitutes the core and most important part of the project, and the IoT interface was implemented using custom HTML. HTML code for the HTML definitions, login, settings, system status, and Manual Control pages was defined in the program memory (PROGMEM) using the char data type and raw literals. This HTML code comprises approximately one-third of the project’s code. The Web Server Interface program is accessed via Wi-Fi, and an asynchronous web server was created using the ESPAsyncWebServer.h library. This server handles HTTP requests and sends the designed HTML pages. The block structure of the system’s software is given as the Function Table of the Code, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Function Table of the Code.

2.3.1. Software Architecture and Scope

The ESP32’s dual-core architecture allows multiple operations to be executed simultaneously. This structure allows background tasks to be managed while the main program is running. Task definitions are defined at the beginning of the code structure using a task variable to run the main automation algorithm and system management. Task 1, given in the code structure, creates an infinite loop structure that manages the system’s automatic functionality. This loop continuously checks for system alerts, provides both manual axis control, and runs the automatic algorithm. All necessary libraries and definitions have been added within the code structure. Variables are defined at the beginning of the code, before the installation and loop functions.

Standard libraries (WiFi.h, AsyncTCP.h, ESPAsyncWebServer.h, ESP32Servo.h) are used for Wi-Fi communication, asynchronous TCP connections, a web server, and servo motor control. Relevant libraries for RFID, NFC, and MPU6050 sensors have also been added. Pin Definitions indicate which pins (input/output) each circuit element is connected to on the ESP32. For example, “conveyor_relay” is defined as pin 33 and “emergency_stop” is defined as pin 13.

Data Variables, which are servo angles received from the IoT interface (servo_1_angle, etc.), are defined as both text-based (String) and numeric-based (int). Boolean variables are used to manage system alarm types, microcontroller calibrations, and the tag read logic status.

Following the definitions of Auxiliary Functions and Logic Management, various functions that implement the basic functions of the system have been added. Examples of System Control Functions include “system_control_typ,” which returns the user-selected mode (Automatic or Manual), and “tag_read,” which determines the product number by reading the RFID tag. Furthermore, the “read_voltage_value” and “read_current_value” functions, as their names suggest, read and calculate voltage and current values. These functions produce analog readings that are then printed on the user screen after averaging and scaling. In Warning and Limit Control, the “buzzer_warning” function triggers a buzzer in the event of warning conditions. “robot_switch” controls the robot’s axis limits. “system_warning” returns text-based warnings based on voltage, current, or emergency stop conditions. Debug provides debugging and system monitoring by periodically printing data received from the IoT interface, MPU6050 data, pin states, and self-control variables to the serial monitor.

In MPU Calibration, the “MPU6050_calibrate” function, which performs the calibration of the MPU6050, which is critical for the correct operation of the robotic arm, activates the digital motion processor (DMP) by obtaining offset values from the sensor.

Robot Motion Functions are defined as complex sequences of arm movements and are coded as discrete functions.

- Motion Algorithm: The robot’s product pick-up and drop-off operations (robot_conveyor_CNC, product_transport_from_CNC_to_first_drop_point) were created based on angle values obtained from manual tests.

- Analog Motion: A key feature of these functions is their extensive use of for loops to prevent the robot from making sudden digital movements. For loops gradually increase and decrease angle values, resulting in slower analog motion.

The main code block runs only once at program startup, making the initial settings. These include initiating serial communication, setting all pin modes (INPUT/OUTPUT), initiating NFC communication, starting the web server (server.begin()), and issuing HTTP requests to all HTML pages and IoT functions (receiving data, printing status).

Following the main function is the infinite loop function, which runs continuously and executes tasks that need to be executed cyclically within the system. The code flow and function structure can be seen in Figure 8.

2.3.2. HMI Program

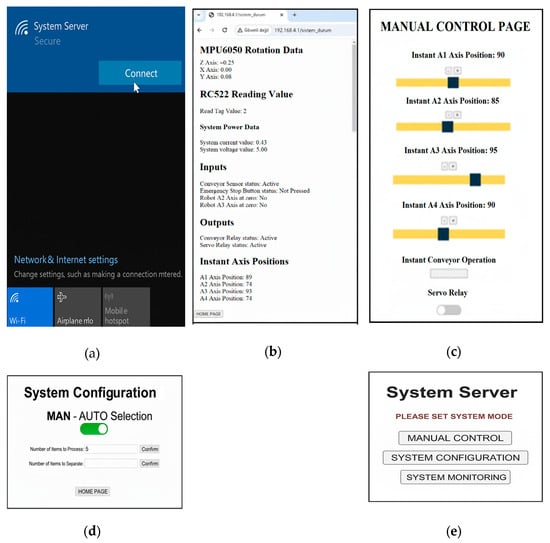

System software is implemented using the Arduino IDE. IoT usage in the system is implemented through HTML design. The web interface on the ESP32 is implemented as HTML pages served via raw strings embedded in flash memory. This allows large HTML content to be stored without consuming RAM, eliminates the need for an external file system, and simplifies distribution. When the ESP32 is powered on, it launches a local web server in Figure 9a and defines a Wi-Fi access point for initial setup. After connecting from any client device (Windows/macOS/Android/iOS), the operator opens a browser to the device’s fixed IP address, 192.168.4.1, to load the welcome page and access the operating screens. The network name is “System Server,” and the password is defined in the code for security purposes (Figure 9e). This access point mode workflow standardizes commissioning and enables the HMI to be used without external infrastructure (Figure 9a–e).

Figure 9.

Commissioning and Network Access (a) Connecting to the system network via Wi-Fi from a Windows computer (b) Buttons for accessing other pages on the welcome screen (c) System Monitoring Page (d) System Configuration Screen (e) Manual control page.

Details of the system codes are explained in Section 2.3.1 Software Architecture and Scope, which serves as an introduction to the system software. The flowchart, Function Table, and code for the system code are presented in Figure 9. First, the code required to access the system login page is defined. The code written for the login page includes the necessary buttons and features for “Manual Control,” “System Configuration,” and “System Monitoring.” The system can be operated in two modes: automatic and manual.

2.3.3. Operating Modes and Safety

The system is designed to operate in two modes: manual and automatic. The interface selection screen is shown in Figure 9d.

Manual mode is designed for setup, calibration, learning system behavior, and intervening in the event of a fault. The system user can control the robot’s A1–A4 connections and the conveyor via the web interface. Servo motors are activated only after safe startup checks are completed. Robot movements are speed-limited to prevent sudden movements and collisions. System parameters can be viewed in real time and this provides parameter information for adapting the system to automatic mode Figure 9b.

Recorded positions are stored in memory for reuse by the automatic cycle of acquisition, CNC loading, dwell, and release. All inputs are returned, and range verification is performed. If the user reaches the limit switches, safety interlocks are activated, and excessive movements are rejected and displayed to the user. An emergency stop opens the main relay to de-energize the actuators, and any fault shuts down the system. It records the fault event and requests confirmation from the operator before recommissioning. After selecting Automatic Mode in the system, the target processing quantity and separation quantity are entered in the “System Configuration” screen. Once these two values are confirmed, the robot arm returns to its home position and the MPU6050 accelerometer– gyroscope sensor is automatically calibrated. This calibration is crucial for determining the starting reference and interpreting the movements correctly.

Once calibration is complete, the conveyor is activated and moves forward until the product detection sensor detects a product. When the product reaches the sensor, it identifies the product by reading the NTAG215 tag on the RC522 RFID reader. Five different product IDs are defined in the system, and each product undergoes a specific process:

Odd-numbered products are taken directly to area (ii) for processing at the CNC processing station.

Even-numbered products are not processed by the CNC, so they are deposited directly into area (iii).

If a new odd-numbered product arrives on the conveyor while the CNC process is in progress, the robot immediately holds the product in area (iv) to prevent the line from stopping. The robotic arm first waits for the current CNC operation to complete, moves the processed product to area (iii), and then retrieves the product waiting in area (iv) and transfers it to area (ii) for CNC processing. This cycle continues fully automatically until the specified quantities are completed, unless an error occurs and an emergency stop is triggered. In automatic mode, warnings are indicated by an audible warning and a visual status LED. When the emergency stop button is pressed, all actuators are immediately de-energized, following industrial safety relay logic. This unconditionally guarantees user and system safety.

In addition, the cybersecurity aspect of the system is addressed in terms of protecting control signals against unauthorized access in both manual and automatic modes, preventing potential external interference with the robot arm and conveyor system, and ensuring data and device integrity. The system allows access only to authorized operators and is reinforced with security measures such as encrypted connections, user authentication mechanisms, and emergency stop buttons, thereby enhancing both data security and physical safety. As a result, operations can be conducted in a secure, controlled, and predictable manner.

2.3.4. System Monitoring Page

The System Monitor page provides real-time data for operator situational awareness (Figure 9b). It displays the latest RFID tag, conveyor retroreflective sensor status, emergency stop status, conveyor/servo relay outputs, linkage locations, and supply voltage/current. Low-latency updates allow for rapid detection of out-of-range behavior and immediate operator response. While all fault conditions are pre-addressed through firmware alarms, this real-time view provides additional protection against unexpected anomalies. Data corresponding to the variables captured and presented on-screen can be exported and saved for later analysis and traceability. Thanks to the IoT interface used in the robotic arm and conveyor design, the availability of real-time data streams enables faster adaptation and operational optimization in desired areas.

2.3.5. Experimental Setup and Validation

This section describes the experimental procedures used to validate the prototype in both Automatic and Manual modes. Possible scenarios were implemented on the robotic arm and conveyor.

In the Automatic mode scenario, after selecting “Automatic Mode” on the system configuration page, the operator entered and confirmed the target number of products to be processed and sorted as 5. The robot waits in the starting position. After the number of products is confirmed, the conveyor begins moving. The product is detected as it passes in front of the retroreflective sensor and reaches the RFID reader location, the conveyor stops, and the product tag is identified. Real-time data can be monitored as the product moves on the conveyor, as shown in Figure 9b. A scenario was planned and run as a demo where the product tag numbers were 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively. In the planned scenario, the product with the odd-numbered ID number is placed directly into the CNC processing area (ii). The product with the even-numbered RFID tag number is transferred to area (iii). The label for product number 1 was detected on the conveyor and taken from area (i) by the robotic arm to the CNC processing area (ii). When the label for product number 2 was read and detected by the robotic arm, it was transferred to area (iii) because its label was an even number. When product number 3 reached the robotic arm, it was placed in area (iv), and it was observed that product number 1 was waiting for the CNC processing to be completed. The program cycle ended by repeating the same process for products number 4 and 5. When the cycle ended, meaning that the transfer of five products from the conveyor to the relevant areas by the robotic arm, the system emitted an audible warning and a visual alert with a status LED. The robotic arm returned to its safe standby position. The emergency demo test of the system was performed in automatic mode as follows: The system was restarted for the same scenario and five products. While product number 1 was being transferred to the CNC area by the robotic arm, the emergency button for area (ii) was pressed. It was observed that the system stopped completely during the emergency stop, and the emergency buzzer operated.

For the manual mode scenario, connections A1–A4 were configured using the manual control page using a slider on the interface screen. The product was placed on the conveyor and activated. When the robotic arm reached the access point, the conveyor was stopped, and the product was removed using the manual control page (Figure 9c). The emergency stop was tested again for manual mode, and the system stopped and the buzzer worked.

2.3.6. Performance Evaluation Methods

In this study, various measurement methods were employed to quantitatively evaluate the system performance. During the experimental process, different test scenarios were conducted to determine the levels of accuracy, efficiency, and reliability of the system. Key performance parameters such as power consumption, servo response time, RFID reading accuracy, and emergency stop response time were measured. The collected data were analyzed, and the resulting findings that reflect the overall performance of the system are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

System Performance Metrics.

During the experiments, the following procedures and measurement methods were employed: all tests were conducted using an automatic sorting scenario involving five products; RFID reading accuracy was determined as the average over 30 consecutive repetitions; power consumption was measured and recorded based on current and voltage sensor readings; servo response times were evaluated using a stopwatch for a 60° movement; and emergency stop tests were performed 10 times, with the average system response time calculated.

The experimental results indicate that the designed system offers high accuracy and efficiency. The average cycle time, defined as the time required for a product to be separated from the conveyor by the robotic arm, was measured at 4.8 ± 0.3 s, while the RFID reading accuracy was 98.7% and the servo motor positioning error was ±1.2°.

The system requires energy to operate the robot arm’s axis motors, the conveyor motor, and the control electronics. Measurements indicate that the system consumes a minimum of 2.5 W and a maximum of 5.3 W. In manual mode, only the actuators controlled by the operator are active, so power consumption generally remains at the lower end. In automatic mode, continuous movement of the robot arm, operation of the conveyor, and active sensors increase power consumption toward the maximum value. The system is designed with speed limitations for servo motors and relay-based controls to enhance energy efficiency and prevent sudden movements. Additionally, the emergency stop response time was recorded as 45 ms and emergency stop and safety mechanisms reduce unnecessary energy use, thereby improving both user safety and overall energy efficiency.

The manual mode provides quick and easy positioning and programming for adjustments to the automatic mode. These findings support the fact that the system offers a repeatable and cost-effective solution.

2.3.7. Comparison of the Proposed System with Existing Robotic Control Architectures

To evaluate the effectiveness, cost-efficiency, and practical usability of the proposed ESP32-based robotic arm, a comparative analysis was conducted against industrial PLC-controlled robotic arms and other Arduino/ESP32-based robotic arm platforms. Table 2 presents a structured comparison across key performance criteria, including control architecture, cost, power consumption, sensor capabilities, safety features, expandability, and scalability. This comparative framework highlights the economic advantages and operational flexibility of our system while also identifying its limitations relative to industrial-grade solutions. The analysis provides a clear context for understanding the unique contributions of the proposed design within existing robotic automation approaches.

Table 2.

Comparative Analysis of the Proposed ESP32-Based Robotic Arm and Existing Robotic Arm Systems.

The comparative analysis presented in Table 2 highlights the fundamental distinctions between industrial PLC-controlled robotic systems, generic Arduino/ESP32-based robotic arms, and the proposed ESP32-based robotic arm. While PLC-controlled systems offer superior reliability, certified safety mechanisms, and high-precision operation, their significantly higher cost and lower expandability limit their suitability for low-budget or prototype-oriented applications [40,41]. In contrast, Arduino/ESP32-based systems provide low-cost and flexible platforms but typically lack advanced safety features and industrial-grade robustness [42,43,44,45]. Our proposed ESP32-based system demonstrates a balanced architecture by combining low cost, minimal power consumption (2.5–5.3 W), RFID-based product identification, IoT-enabled remote control, and integrated safety measures such as emergency stop and limit switches. Additionally, its high scalability and web-based expandability make it a strong candidate for educational laboratories, research environments, and small-scale automation tasks where flexibility and economic efficiency are prioritized.

2.3.8. Mathematical and Control Models

The mathematical parameters of the control on the system are presented through the two main motors, the conveyor motor driver and the servo driver structure. Mathematical models of the dynamic control structure of the conveyor motor driver system are presented below.

The conveyor dynamics are established by considering first order plus dead time (FOPDT) and Proportional Integral (PI) control dynamics. The FOPDT model describes the reliable driving of a voltage-frequency (V/f) driven conveyor. The asynchronous motor that turns the conveyor is driven by a frequency converter that operates by keeping V/f constant. The plant transfer function of the conveyor Gc(s) is given Equation (1).

with drive reference, U, belt speed V, gain Kc, time constant Tc, dead time L. Identification step and ratio of Pseudo-Random Binary Sequence (PRBS) test which means Step/PRBS test. v[k] is given in Equation (2) to express the value of the conveyor belt speed in the kth sample in the sampled discrete-time model.

With Internal Model Control, kp and ki for PI adjustment can be calculated as in Equation (3).

u(k) is the kth sample of the input/command signal applied to the system in the discrete-time model. For the PI form, it is presented as in Equation (4).

is an estimate of the measured speed. It reduces the effect of noise/EMI in the controller to calculate the error more robustly. It is given in Equation (5).

The servo’s commanded position and the transfer function , which shows the actual position response , are given in Equation (6). A servo structure with internal current and speed loops is modeled by . It can also be expressed as a quadratic equivalent function. It can be expressed as is the natural frequency and ks is the damping ratio.

is the output speed in the discrete-time model, that is, the kth sample of the conveyor belt speed. It is given in Equation (7).

In axis or servo position control, the controller output signal is represented by . It can also be calculated as PD sensitivity in Equation (8).

3. Discussion

When studies in the literature are examined, it is seen that low-cost microcontrollers with IoT-based support are preferred by more small and medium-sized industrial enterprises (SMEs) in the industrial field. They also stand out in academic studies due to their real-time monitoring and remote management capabilities. Robotic arms increase efficiency and safety in production processes by enabling the efficient execution of repetitive, precision-demanding, and risky tasks [8,14,38]. ESP32-based controllers provide a reliable, scalable, and economical platform with integrated Wi-Fi/Bluetooth support, low power consumption, and sufficient processing capacity [30,46]. RFID-based solutions, on the other hand, accelerate automation processes and minimize error rates with their fast, contactless, and reliable identification features [47]. In this study, a low-cost, IoT-enabled automation unit capable of performing product feeding, labeling, and sorting operations by combining the integration of the IoT infrastructure, ESP32-based controller, RFID-based identification system, sensors, and robotic arm was designed and validated through tests [27,29,48]. In addition to offering the individual advantages of these components, the system also stands out with its integrated structure, high availability, real-time monitoring, remote control, and secure operation. This provides efficiency, security, and flexibility in production processes compared to existing designs, while the combination of RFID, IoT, a user interface program, automatic and manual modes, and data recording and monitoring capabilities demonstrates a remarkable achievement. Furthermore, the IoT robotic arm and conveyor design demonstrates that a successful application can be developed using ESP32 capabilities [38,46,49].

The success of the designed and developed IoT Robotic Arm and Conveyor system can be highlighted as follows:

Stage 1. Virtual modeling and requirements generation: Controller schematics and cell logic were initially tested using Proteus and Factory I/O simulation programs. The physical layout and electronic compatibility of the circuit elements were established in Proteus. The Factory I/O program verified the feasibility of product routing and safety applications. Models reduced integration risk and guided the final bill of materials.

Stage 2. Electronic, power, and safety integration: Relays and optocouplers were used on the ESP32 to eliminate risks posed by field elements. Overcurrent/voltage protection, limit monitoring, emergency stop, and instantaneous cutoff features were implemented to create a robust security layer suitable for industrial environments.

Stage 3. Software and IoT HMI: The source code developed in the physical system was mapped to an embedded web interface. Access point mode, commissioning, page navigation (Manual Control, System Configuration, System Monitoring), and real-time data monitoring were implemented and operated as intended, enabling remote control and supervision.

Stage 4. Manual mode trials: The robotic arm joints (A1–A4) were operated safely, and position information was used for automatic mode, taking into account the arm’s movements. Limit switches and acceleration sensors were used to appropriately program the robotic arm’s movements.

Stage 5. Automatic mode trials: After configuring target counts, the system implemented tag-based routing for five product IDs. Product separation and product tracking for the CNC machining station were successfully implemented in automatic mode.

Stage 6. Safety Verification: The emergency stop trigger immediately de-energized all actuators by opening the main relay, independent of the firmware. Alarms for overcurrent, overvoltage, timeout, and limit violations were included in the fault latching by the firmware. Events were recorded and the robotic arm and conveyor movements were halted until confirmed, ensuring the system was safe and compliant.

Stage 7. Economic Viability and Usability: The use of affordable controllers, sensors, and relay hardware enabled the target price point to be achieved without sacrificing core functionality. The browser-based HMI required no additional software and facilitated rapid commissioning and operator training.

Although the proposed IoT-based robotic cell demonstrated promising performance in terms of reliability, cost efficiency, and operational speed, several limitations remain. The experimental validation was conducted under controlled laboratory conditions, with a limited range of product types and test repetitions. Environmental factors such as temperature, humidity and electromagnetic interference have not been evaluated under laboratory conditions and should be considered in industrial environments. Additionally, the current system was operated with a single robotic arm and a fixed conveyor speed, which opens up development opportunities for multi-robot and variable speed conveyor systems. In addition, stress tests performed on the system demonstrated that it operates reliably under standard product flow conditions, while revealing potential bottlenecks in high-load scenarios, such as increased processing time at the RFID reading stage or during simultaneous robot arm operations, suggesting areas for further optimization. These results highlight both the practical effectiveness of the system and the need for targeted improvements under peak operating conditions.

Future research will focus on extending the system to multi-robot collaborative environments, implementing adaptive conveyor control, and integrating AI-based modules. Industrial-scale validation, long-term operation, and scalability assessments for SMEs will also be conducted. A hybrid RFID-image architecture could enable product integrity-based decision-making, while security and operability can be enhanced through certified relays, event log analysis, and HMI integration. In addition, in this study focuses on control architecture, IoT and timing/EMI verification, comprehensive experimental investigations on multi-actuator scalability and SG90–RC522 EMI shadowing are excluded; these topics are limited to practical wiring/load-budget guidelines and are planned as future work.

4. Conclusions

The findings of this study demonstrate that a low-cost robotic cell with RFID-based ID-based guidance can safely and reproducibly perform product feeding, sorting, and sorting tasks. The embedded web-based HMI simplifies mode selection and status monitoring, while the hardware Emergency Stop and relay interlock architecture enables software-independent safe shutdown. The cycle time, sorting accuracy, and RFID reading performance reported during experimental validation make the system suitable for small and medium-sized industrial enterprises (SMEs). Therefore, it offers a practical performance solution to complex problems for industrial production line integration. Low-cost proposals for similar tasks exist in the literature, replacing PLC (or CNC)-based solutions with higher hardware complexity. While PLC-like designs provide high precision and rich sensing capabilities, initial investment and commissioning costs can be often limiting for SMEs. The architecture, which utilizes accessible ESP32 and peripherals, offers a meaningful alternative to meet the product selection and sorting needs of production lines. Furthermore, ESP32’s embedded HMI offers a facility that simplifies maintenance and parameter updates in the field. On the other hand, in lines where visual quality control is required, RFID’s reliable authentication capability can complement visual inspection.

From an application perspective, the identity-based rule enforcement approach has been applied in studies of flexible prioritization scenarios for different stations on the line. For example, when the CNC station is busy, routing products to a secondary drop point increases production line efficiency. Furthermore, the double-contact structure of the E-stop, which directly releases the main relay, provides a safety contribution independent of software errors. Providing robotic arm movement and product tracking via a real-time HMI contributes to the best practices highlighted in the literature in terms of safety capabilities and real-time safe commissioning and maintenance processes. The measured accuracy and cycle time values indicate that the performance achieved with low-cost components can compete with higher-cost industrial solutions, within certain limits. In summary, this study demonstrates that a low-cost robotic cell combining RFID tag-based product tracking with hardware security layers is a viable option for rapid commissioning and sustainable maintenance at the SME scale. Furthermore, the security features it offers at both hardware and software levels are gaining value in industrial applications for high security.

5. Pseudo Code

| Parameters, State, and Counters | HMI → Logical Effects (Events) | Safety & Validation |

| PARAMS: N_PROCESS //total items to process (AUTO) N_SORT //total items to sort/divert T_AX_DELAY //per-axis settle delay (ms) T_STEP_DELAY //inter-step delay (ms) STATE: MODE ∈ {AUTO, MAN} FLAGS: system_ready, tag_ok, item_present, goal_reached COUNTERS: cnt_processed ← 0 cnt_sorted ← 0 | EVENT HMI.set_mode(AUTO) => MODE ← AUTO; LOG(“mode=AUTO”) EVENT HMI.set_mode(MAN) => MODE ← MAN; LOG(“mode=MAN”) EVENT HMI.set(N_PROCESS = k) EVENT HMI.set(N_SORT = m) EVENT HMI.axis_set(i, angle) //manual axis nudge EVENT HMI.relay(name, on_off) //servo/conveyor power | FUNCTION SAFETY_OK(): RETURN (E_STOP == OFF) AND (LIMIT_SWITCHES == OK) FUNCTION RFID_VALIDATE(): IF RFID.TAG ∈ ALLOWED_SET THEN tag_ok ← TRUE; RETURN TRUE ELSE tag_ok ← FALSE; RETURN FALSE |

| Automatic Task Sequence | Helper Routines (Abstractions) | Manual Mode Loop |

| PROCEDURE AUTO_RUN(): REQUIRE SAFETY_OK() FLAGS.system_ready ← TRUE WHILE cnt_processed < N_PROCESS: WAIT UNTIL item_present == TRUE IF NOT RFID_VALIDATE(): LOG(“warn: invalid_tag”); CONTINUE //PICK (from conveyor) MOVE_AXES(A1..A4, pose_PICK); WAIT T_STEP_DELAY GRIPPER(CLOSE); WAIT T_AX_DELAY //TRANSFER (to CNC/target) MOVE_AXES(A1..A4, pose_TARGET); WAIT T_STEP_DELAY //PLACE GRIPPER(OPEN); WAIT T_AX_DELAY MOVE_AXES(A1..A4, pose_HOME); WAIT T_STEP_DELAY cnt_processed ← cnt_processed + 1 LOG(“cycle_done”, cnt_processed) IF cnt_sorted < N_SORT: SORT_BRANCH() //optional divert END WHILE FLAGS.goal_reached ← TRUE | PROCEDURE MOVE_AXES(A1..A4, pose): FOR axis ∈ {A1, A2, A3, A4}: GO(axis, pose[axis]) WAIT T_AX_DELAY PROCEDURE SORT_BRANCH(): MOVE_AXES(A1..A4, pose_SORT) GRIPPER(OPEN/CLOSE) //as required by path cnt_sorted ← cnt_sorted + 1 PROCEDURE CONVEYOR(run: BOOL): RELAY(conveyor, run) | PROCEDURE MANUAL_LOOP(): REQUIRE SAFETY_OK() LOOP: EVT ← HMI_NEXT_EVENT() MATCH EVT: CASE AXIS_SET(i, angle): GO(Ai, angle); LOG(“axis”, i, angle) CASE RELAY(name, v): RELAY(name, v); LOG(“relay”, name, v) CASE EXIT: BREAK |

| Telemetry, Logging, and Error Handling | Notes on Reproducibility | Extensibility Hooks |

| ON EVERY CRITICAL_STEP: LOG(timestamp(), step_id, MODE, A1..A4_actual, cnt_processed, cnt_sorted) ON ERROR (E_STOP || LIMIT_FAULT || TIMEOUT): RELAY(servo, OFF); RELAY(conveyor, OFF) HALT_MOTION() MODE ← MAN LOG(“safe_stop”) | Timing: Publish final values for T_AX_DELAY and T_STEP_DELAY; include tolerance ranges. Thresholds: Document detection thresholds for item_present and RFID acceptance criteria. Safety gating: Explicitly state that SAFETY_OK() is required before and between critical steps. Trace format: Fix a canonical log schema (timestamp, step_id, mode, axes, counters). HMI mapping: Provide a table in the main text listing HMI routes ↔ events (e.g., set_mode, axis_set, relay). |

|

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Y., C.A. and F.K.; methodology, S.Y. and C.A.; software, S.Y., C.A. and F.K.; validation, S.Y. and C.A.; formal analysis, F.K.; investigation, S.Y., C.A. and F.K.; resources, S.Y., C.A. and F.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Y., C.A. and F.K.; writing—review and editing, S.Y., C.A. and F.K.; visualization, C.A. and F.K.; supervision, S.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tasmant, H.; Bossoufi, B.; Alaoui, C.; Siano, P. A Review of Machine Learning and IoT-Based Energy Management Systems for AC Microgrids. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2025, 127, 110563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeas, J.; Tudela, A.; Pons, Ó.; Bandera, J.P.; Bandera, A.; Bustos, P. CRDT-Based Knowledge Synchronization in an Internet of Robotics Things Ecosystem for Ambient Assisted Living. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2025, 259, 104437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Schmid, L.; Klaiber, M.; Rössle, M. Extraction of Measurement Device Information on an ESP32 Microcontroller: TinyML for Image Processing. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 246, 2002–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, M.; Doležal, P.; Budík, O.; Ptáček, L.; Geyer, J.; Davídková, M.; Prokýšek, M. Intelligent Inspection Probe for Monitoring Bark Beetle Activities Using Embedded IoT Real-Time Object Detection. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2024, 51, 101637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaad, R.H.; Mohammadi, M.; Poudel, O. Developing an Intelligent IoT-Enabled Wearable Multimodal Biosensing Device and Cloud-Based Digital Dashboard for Real-Time and Comprehensive Health, Physiological, Emotional, and Cognitive Monitoring Using Multi-Sensor Fusion Technologies. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2025, 381, 116074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touaref, F.; Seres, I.; Farkas, I. IoT-Enabled Thermal and Surface Management System for PV Modules Coupled with a Cylindro-Parabolic Collector. Energy Rep. 2025, 14, 2075–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumaiya, M.N.; Vachanamruth, G.S.; Naveen, V.; Varshitha, C.; Yashaswini, V.P. Wearable Sleeve for Physiotherapy Assessment Using ESP32 and IMU Sensor. In Computational Intelligence and Deep Learning Methods for Neuro-Rehabilitation Applications; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 101–119. [Google Scholar]

- Ciungan, D.-A.; Mîș, E.-O.; Rusu, D.-Ș.; Bratosin, I.-A.; Popovici, A.-F.; Popovici, R.; Goga, N.; Goga, M.; Pomană, L.-N.; Bordea, C.-A.; et al. Enhancing IoT Education through Hybrid Robotic Arm Integration: A Quantitative and Qualitative Student Experience Study. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Neria, M.; Madonski, R.; Hernández-Martínez, E.G.; Lozada-Castillo, N.; Fernández-Anaya, G.; Luviano-Juárez, A. Robust Trajectory Tracking for Omnidirectional Robots by Means of Anti-Peaking Linear Active Disturbance Rejection. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2025, 183, 104842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, A.; Branco, D.; Di Martino, B.; Fedele, C.; Venticinque, S. IoT-Robotics for Collaborative Sweep Coverage. Internet Things 2024, 28, 101417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, T.; Newton, M.H.; Trevathan, J.; Sattar, A. IoT Edge Network Interoperability. Comput. Commun. 2025, 236, 108125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnif, M.; Sahnoun, S.; Saad, Y.B.; Fakhfakh, A.; Kanoun, O. Combinative Model Compression Approach for Enhancing 1D CNN Efficiency for EIT-Based Hand Gesture Recognition on IoT Edge Devices. Internet Things 2024, 28, 101403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Gijón, S.; Salmerón, J.F.; Falco, A.; Loghin, F.C.; Lugli, P.; Morales, D.P.; Rivadeneyra, A. Printed RFID Sensing System: The Cost-Effective Way to IoT Smart Agriculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 232, 110116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahab, H.; Iqbal, M.; Sohaib, A.; Khan, F.U.; Waqas, M. IoT-Based Agriculture Management Techniques for Sustainable Farming: A Comprehensive Review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 220, 108851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dera, P.; Talaśka, T.; Długosz, R. A New, Cost-Efficient Modular Sensor Platform for IoT and Predictive Maintenance in Industrial Applications. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2026, 473, 116777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, A.; Serôdio, C.; Briga-Sá, A.; Valente, A. Next-Generation Smart Homes: CO2 Monitoring with Matter Protocol to Support Indoor Air Quality. Internet Things 2025, 32, 101649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, P.; Goel, S.; Puthooran, E. Edge AI Enabled IoT Framework for Secure Smart Home Infrastructure. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 235, 3369–3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa-Medina, J.F.; Porta-García, M.Á.; Gutiérrez, J.; Porta-Gándara, M.Á. Solar Forced Convection Dryer for Agriproducts Monitored by IoT. Internet Things 2025, 31, 101566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ospina-Rojas, E.; Botero-Valencia, J.; Betancur-Vasquez, D.; Pearce, J.M. Open-Source Three-Dimensional IoT Anemometer for Indoor Air Quality Monitoring. HardwareX 2025, 23, e00656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayor, J.J.A.M.; Shishir, N.T.; Barmon, B.B.; Ahemed, S.; Rahman, M.M. IoT-Driven Real-Time Weather Measurement and Forecasting Mobile Application with Machine Learning Integration. Array 2025, 27, 100474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobpant, J.; Klongratog, B.; Rudradawong, C.; Sakdanuphab, R.; Limsuwan, P.; Sakulkalavek, A. Optimizing Fabrication Processes for Scalable Production of Flexible Thermoelectric Modules: A Case Study on Self-Powered IoT Systems. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 106150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadjine, C.; Ouafi, A.; Benlamoudi, A.; Taleb-Ahmed, A. Computer Vision in Warehouse Management Automation: A Survey on Implemented Methods with Prototyping Hardware. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 160, 111886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, G.; Singh, R.; Gehlot, A.; Shaik, V.A.; Twala, B.; Priyadarshi, N. IoT-Based Real-Time Analysis of Battery Management System with Long Range Communication and FLoRa. Results Eng. 2024, 23, 102770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, F.; Ugarte Querejeta, M.; Hellewell, J.; Ur Rehman, H.; Illarramendi Rezabal, M.; Chaplin, J.C.; Sanderson, D.; Ratchev, S. PLC Orchestration Automation to Enhance Human–Machine Integration in Adaptive Manufacturing Systems. J. Manuf. Syst. 2023, 71, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaria, S.; Zalama, E.; Gómez, R.; Muñoz, P.; Gómez-García-Bermejo, J. Robot de Cables para la Limpieza de Fachadas. Rev. Iberoam. Autom. Inform. Ind. 2023, 20, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runnaware, M.; Chaudhari, D.; Muddamwar, K.; Muddamwar, S.; Shende, H.; Ansari, M.H.; Gyanchandani, N.N. A Review on Robotic Arm Vehicle with Object and Facial Recognition. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2022, 10, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, A.; Sharp, A.; Vagapov, Y. Comparative Analysis and Practical Implementation of the ESP32 Microcontroller Module for the Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the 2017 Internet Technologies and Applications (ITA), Wrexham, UK, 12–15 September 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 143–148. [Google Scholar]

- Ban, P.; Desale, S.; Barge, R.; Chavan, P. Intelligent Robotic Arm. ITM Web Conf. 2020, 32, 01005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiuch, M.; Foltýnek, P.; Smutný, P. Using the ESP32 Microcontroller for Data Processing. In Proceedings of the 2019 20th International Carpathian Control Conference (ICCC), Kraków, Poland, 26–29 May 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kalamaras, S.D.; Tsitsimpikou, M.A.; Tzenos, C.A.; Lithourgidis, A.A.; Pitsikoglou, D.S.; Kotsopoulos, T.A. A Low-Cost IoT System Based on the ESP32 Microcontroller for Efficient Monitoring of a Pilot Anaerobic Biogas Reactor. Appl. Sci. 2024, 15, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hercog, D.; Lerher, T.; Truntič, M.; Težak, O. Design and Implementation of ESP32-Based IoT Devices. Sensors 2023, 23, 6739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wu, F.; Wang, F.; Zou, T.; Li, M.; Xiao, X. CNN-MLP-Based Configurable Robotic Arm for Smart Agriculture. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, F.; Ahmed, S.; Amin, F.; Qayyum, S.; Ullah, F. Integrating BIM–IoT and Autonomous Mobile Robots for Construction Site Layout Printing. Buildings 2023, 13, 2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, S.; Giunta, L.; Rino, V.; Mellace, S.; Sozzi, A.; Lago, F.; Curcio, E.M.; Pisla, D.; Carbone, G. Design of a Wheelchair-Mounted Robotic Arm for Feeding Assistance of Upper-Limb Impaired Patients. Robotics 2024, 13, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.; Lee, S.H.; Oh, S.E. Conceptual Design of Simulation-Based Approach for Robotic Automation Systems: A Case Study of Tray Transporting. Processes 2024, 12, 2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Huang, X.; Zhuang, J.; Xu, J.; Shao, Z. CIoT-Robot Cloud and IoT-Assisted Indoor Robot for Medicine Delivery. In Proceedings of the 2018 Joint International Advanced Engineering and Technology Research Conference (JIAET 2018), Bangkok, Thailand, 17–18 March 2018; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2018; pp. 85–89. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, W.; Liu, T.; Wang, Y.; Ge, Y.; Zhu, M.; Jiang, R. Design of Home Robot Based on MPU6050 Six-Axis Robotic Arm. In Proceedings of the 2025 Asia-Europe Conference on Cybersecurity, Internet of Things and Soft Computing (CITSC), Singapore, 12–14 January 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Gaetani, F.; Primiceri, P.; Zappatore, G.A.; Visconti, P. Hardware Design and Software Development of a Motion Control and Driving System for Transradial Prosthesis Based on a Wireless Myoelectric Armband. IET Sci. Meas. Technol. 2019, 13, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Luan, Y.; Dong, X.; Zhou, H.; Chen, X.; Yu, X. Design of Automatic Controller System for Three-Axis 3D Printing Platform. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 2095, 012050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efe, E.; Özcan, M.; Haklı, H. Building and cost analysis of an industrial automation system using industrial robots and PLC integration. Avrupa Bilim Ve Teknol. Derg. 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Naib, A.M. Design an industrial robot arm controller absed on PLC. Przegląd Elektrotechniczny 2022, 98, 105–109. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A.S.; Marzog, H.A.; Abdul-Rahaim, L.A. Design and Implement of Robotic Arm and Control of Moving via IoT with Arduino ESP32. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2022, 12, 24625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emad, E.; Alaa, O.; Hossam, M.; Ashraf, M.; Shamseldin, M.A. Design and implementation of a low-cost microcontroller-based an industrial delta robot. WSEAS Trans. Comput. 2021, 20, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L. Research on Education Robot Control System Based on ESP32. J. Educ. Educ. Res. 2024, 7, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenchireddy, K.; Dora, R.; Mulla, G.B.; Jegathesan, V.; Sydu, S.A. Development of robotic arm control using Arduino controller. IAES Int. J. Robot. Autom. (IJRA) 2024, 264, 1024–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokovic, M.; Bozic, D.; Lukic, D.; Milosevic, M.; Sokac, M.; Santosi, Z. Physical Adaptation of Articulated Robotic Arm into 3D Scanning System. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulkawi, W.M.; Nizam-Uddin, N.; Sheta, A.F.A.; Elshafiey, I.; Al-Shaalan, A.M. Towards an Efficient Chipless RFID System for Modern Applications in IoT Networks. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzus, J.; Trawiński, T.; Kielan, P.; Szczygieł, M. Design and Implementation of a Tripod Robot Control System Using Hand Kinematics and a Sensory Glove. Electronics 2025, 14, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcés, H.O.; Godoy, J.; Riffo, G.; Sepúlveda, N.F.; Espinosa, E.; Ahmed, M.A. Development of an IoT-Enabled Smart Electricity Meter for Real-Time Energy Monitoring and Efficiency. Electronics 2025, 14, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]