1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic forced teaching and research staff to rapidly switch to remote delivery of courses [

1,

2]. While this shift posed significant challenges, it also created opportunities to rethink and modernize educational approaches. It should be noted that distance learning did not appear with the pandemic; it has long provided educational opportunities for individuals who are geographically remote, ill, or otherwise unable to attend in-person classes [

3,

4,

5].

Distance teaching, however, is highly dependent on the subject area. In technical disciplines, the lack of access to laboratory equipment constitutes a major obstacle to effective learning. One way to overcome this limitation is the use of simulation software, which can replicate laboratory conditions virtually. Such tools have proved particularly useful in courses such as electrical engineering or electronics [

6,

7,

8,

9].

In addition to the challenges introduced by the pandemic, distance learning has its own inherent characteristics and demands. A key advantage is its flexibility: students can access learning materials asynchronously, adjust their pace of study, and participate from diverse geographical and personal circumstances. However, this temporal flexibility has direct implications for the design of remote laboratories. In this context, the tools supporting online laboratory work differ in the level of time dependence they impose. Solutions relying on real-time instructor support operate in a synchronous mode, requiring students to attend at specific time slots and interact live with the instructor. In contrast, tools providing delayed or automated assistance operate in an asynchronous mode, enabling students to complete laboratory tasks at any convenient time, fully aligning with the concept of temporal flexibility.

This distinction is particularly important in engineering and technology-oriented disciplines, where practical, experiment-based learning forms an integral component of the curriculum and must be carefully adapted to remote delivery conditions.

The increasing integration of digital tools into engineering education has significantly transformed the way technical subjects are taught, especially in fields that require access to complex laboratory setups. Simulation-based learning environments have become indispensable in modern teaching methodologies, providing students with opportunities to visualize and analyze physical phenomena that are otherwise difficult to demonstrate experimentally. In automatics, electronics, and optoelectronics, interactive simulations support both conceptual understanding and the development of practical skills, linking theory with hands-on experimentation [

10,

11,

12,

13].

Distance learning, which gained particular importance during the pandemic, has also underlined the need for adaptable and flexible educational tools capable of maintaining the quality of laboratory-based courses without requiring physical access to equipment. In this context, software platforms that integrate simulation, visualization, and user interaction play a key role. They enable students to perform meaningful, platform-mediated experiments, receive immediate feedback, and explore system behavior independently [

14,

15,

16].

OptiPerformer, a freely available optical system simulation software, exemplifies such a platform. It offers a user-friendly interface and a rich set of predefined components, making it particularly suitable for educational purposes. Users can model optical communication systems, including transmitters, fibers, amplifiers, and receivers, while visualizing signal propagation and key performance parameters. OptiPerformer thus functions as a domain-specific educational platform, providing a consistent and accessible interface for both remote and in-lab teaching, and enabling students to explore complex optical phenomena with minimal technical barriers.

Despite the widespread use of simulation tools in engineering education, existing literature rarely provides a fully structured and pedagogically validated framework for conducting complete fiber-optic laboratory classes using freely available software. The innovative contribution of this work lies in integrating a coherent set of optical-communication laboratory exercises, covering, e.g., eye-diagram analysis, chromatic dispersion, dispersion compensation, and pulse propagation, into both distance and face-to-face teaching. Importantly, the approach is evaluated over several academic years on a large cohort of students, enabling a systematic assessment of learning outcomes and teaching effectiveness. This multi-year validation demonstrates that simulation-based laboratories originally implemented under pandemic constraints can successfully support, and in some cases enhance, traditional in-lab teaching. Thus, the novelty of the present study is pedagogical and methodological: it offers a scalable, hardware-independent, and empirically tested model for teaching fiber-optic communication.

The aim of this paper is to present experiences from four consecutive semesters (two remote and two in-lab) of teaching optical fiber system fundamentals using OptiPerformer and to evaluate its effectiveness in supporting learning outcomes in both remote and traditional classroom settings. Selected laboratory exercises are presented, covering fiber-optic system design, dispersion compensation, and Gaussian pulse propagation. These exercises highlight how a platform-based approach can deliver practical, hands-on learning experiences without the need for physical laboratory infrastructure. Student feedback and learning outcomes demonstrate that using OptiPerformer supports high-quality education in optoelectronics, promoting engagement, conceptual understanding, and the development of analytical and problem-solving skills, irrespective of whether instruction is delivered in-person or remotely.

2. Methodology

The methodological framework integrates the design of laboratory exercises and a multi-year pedagogical evaluation. The approach was developed to ensure that OptiPerformer can be effectively used as a standalone platform for teaching optical fiber communication systems in both distance and in-class learning environments.

2.1. Preparation of Simulation Materials

All laboratory activities were based on predefined OptiPerformer (.osd) simulation files derived from educational examples provided by Optiwave. Each file was reviewed and adapted to match the intended learning outcomes of the optoelectronics course. Only selected parameters were exposed to students to ensure controlled and repeatable experimentation.

2.2. Structure of Laboratory Exercises

Each exercise followed a structured sequence:

Reviewing the theoretical background of the topic;

Performing preliminary analytical calculations;

Running simulations with appropriate parameter adjustments;

Comparing theoretical predictions with simulation results;

Formulating conclusions.

Every exercise included a detailed instruction sheet and a protocol template with empty tables for parameters, calculations, plots, and conclusions.

2.3. Implementation in Distance and In-Class Settings

The methodology was applied in both remote and traditional laboratory classes (two semesters online and two in-person). In all cases, students worked individually and could request assistance from the instructor at any time, either directly or via online tools such as video conferencing, text chat, and screen sharing. For distance learning, instructions were delivered through online platforms, and simulation files were distributed prior to each class.

2.4. Multi-Year Evaluation and Data Collection

The effectiveness of the proposed methodology was assessed over four academic years, involving more than 200 students. Pedagogical evaluation consisted of two components:

Anonymous surveys completed after each laboratory sequence, assessing perceived clarity, engagement, and usefulness of the simulations;

Analysis of final laboratory grades, treated as an objective measure of achieved learning outcomes.

3. OptiPerformer in Optical Communication Education

3.1. Description of Optoelectronics Course

The Optoelectronics course discussed in this study aims to provide students with fundamental knowledge of optical and optoelectronic devices and systems, with an emphasis on the principles governing optical signal transmission and detection. The learning objectives include understanding the operation of fiber-optic components, analyzing the impact of attenuation and dispersion on signal integrity, and developing skills in designing and evaluating basic optoelectronic systems.

The laboratory section of the course is structured around key areas that mirror the theoretical content. Students begin by exploring the essential parameters governing guided optical transmission, followed by investigations into fiber attenuation and its measurement. The program then addresses dispersion and its impact on signal integrity, along with strategies for mitigating these effects through, e.g., compensation techniques. Further activities include modeling fiber properties to extract critical parameters, ending with an analysis of optical receiver performance with a focus on sensitivity considerations.

3.2. Selection of Simulation Environment

To support these learning outcomes, an appropriate simulation environment is essential, particularly in distance-learning scenarios where physical access to laboratory equipment is limited. Several candidate platforms were initially considered, including OptSim, Lumerical, PyNLO, and MEEP. While these tools offer extensive modeling capabilities, they either require commercial licenses, involve a steep learning curve, or demand significant computational resources, i.e., factors that are critical when students need to install and use the software on their own computers.

OptiPerformer emerged as the most suitable solution. It provides an intuitive interface and immediate access without licensing restrictions, making it highly accessible for students. Importantly, its functional scope aligns closely with the course content: it allows students to model fiber attenuation, analyze dispersion and dispersion-compensation techniques, visualize pulse propagation, and evaluate receiver performance using eye diagrams and sensitivity metrics. For these reasons, OptiPerformer was adopted as the primary platform supporting both remote and on-campus laboratory classes.

3.3. Features and Educational Role of OptiPerformer

OptiPerformer is a freeware simulation environment developed by Optiwave Systems Inc. (Ottawa, ON, Canada) as a complement to its professional-grade software, OptiSystem 18. While OptiSystem provides comprehensive capabilities for designing, testing, and simulating virtually any type of optical link within a wide range of communication networks, OptiPerformer offers a simplified, yet fully functional version intended primarily for educational and demonstration purposes.

Unlike OptiSystem, which allows full project creation and component customization, OptiPerformer is designed to load and execute pre-prepared simulation files. Nevertheless, it enables users to perform complete simulations, modify selected parameters, and analyze results through a clear graphical interface. This functionality makes it an effective and practical tool for teaching optical communication systems, particularly when access to full laboratory infrastructure is limited.

An important advantage of OptiPerformer is its accessibility and ease of use. The software can be freely downloaded from the Optiwave website and installed on standard personal computers without the need for additional licenses or advanced hardware. Its intuitive interface allows students to focus on understanding system behavior rather than on software configuration, which is particularly valuable in distance-learning scenarios.

From an educational perspective, OptiPerformer provides opportunities to conduct simulation-based laboratory activities that closely reflect the content of traditional experiments. Even without access to the full OptiSystem package, instructors and students can use the set of exemplary simulation files available on the Optiwave webpage [

17]. These examples cover a broad range of topics relevant to fiber-optic education, including:

Fundamentals of optical fiber systems;

Attenuation and dispersion analysis;

Power budget calculations;

Dispersion compensation techniques;

Gaussian pulse propagation;

Receiver sensitivity studies.

Together, these examples can form the basis for at least six different laboratory assignments, effectively supporting the teaching of fiber-optic communication principles both in-class and remotely.

In addition, OptiPerformer supports a blended teaching model, in which instructors distribute simulation files (.osd) and guide students through analytical tasks involving parameter changes and result interpretation. This approach encourages independent problem solving and deepens understanding of the relationships between optical components and system performance.

In the further part of this paper, selected examples are presented and discussed. The aim is to demonstrate how OptiPerformer can be successfully incorporated into the teaching of optical fiber systems, enabling instructors to easily adopt the presented methods in their own educational practice.

It should be noted that the models used in OptiPerformer rely on standard analytical descriptions, reproducing classical behaviors documented in fiber-optic communication theory. The parameters applied in the laboratory exercises, such as fiber dispersion coefficients, pulse widths, link lengths, and attenuation values, correspond closely to those encountered in practical transmission systems, enabling students to analyze system responses that reflect real-world operation. Importantly, OptiPerformer is derived from the commercial OptiSystem platform, which is widely adopted in both research and industrial environments for modeling, optimization, and experimental verification of optical communication links. Numerous studies have utilized OptiSystem for the design and simulation of optical communication systems, illustrating its effectiveness and broad adoption in the field [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. In this context, the simulation environment provides a trustworthy approximation of experimental conditions and can be effectively combined with hands-on laboratory work.

4. Example Laboratory Exercises

Below, three examples of OptiPerformer use are presented, accompanied by insights from teaching practice and resulting recommendations. The first case study illustrates a basic fiber-optic system, while the second and third, more advanced, focus on dispersion compensation and Gaussian pulse propagation. The full set of exercises covers a broader range of topics relevant to fiber-optic education, as outlined in the previous section.

All three simulation examples presented in

Section 4.1,

Section 4.2 and

Section 4.3 were performed under consistent operating conditions. In each case, the transmission bit rate was fixed at 2.5 Gbit/s and the fiber model used in OptiPerformer employed parameters corresponding to a standard Corning SMF-28 single-mode fiber, ensuring realistic dispersion and attenuation characteristics representative of contemporary telecommunication links.

The reproducibility of the presented exercises is guaranteed by standardized OptiPerformer (.osd) project files derived from Optiwave’s instructional example library.

4.1. Basic Fiber-Optic System

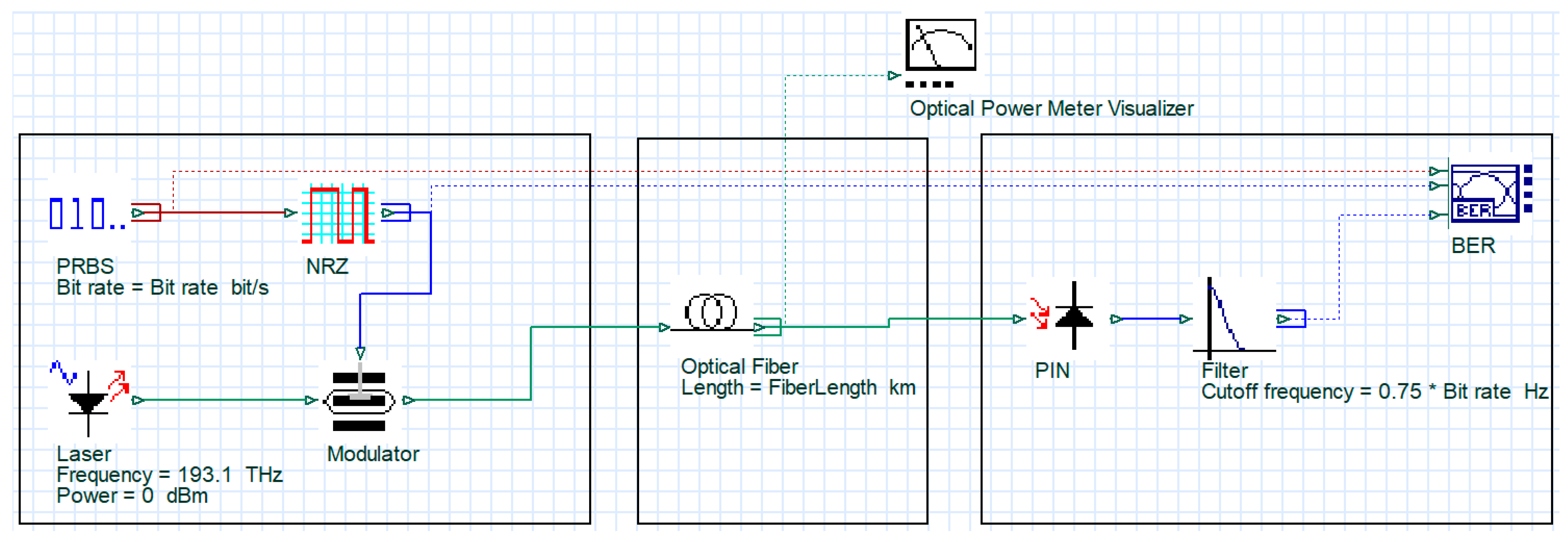

The system shown in

Figure 1 consists of a transmitter, an optical fiber (transmission channel), and a receiver. It is one of the exemplary files available for downloading from the Optiwave webpage. The system is equipped with virtual measurement devices, including an optical power meter at the receiver input (equivalent to the fiber output) and a bit error rate (BER) analyzer.

The system is divided into three main blocks, representing the key elements of any fiber-optic link. The transmitter block contains a pseudo-random bit sequence (PRBS) generator, a laser diode, and a modulator. The receiver block includes a photodiode, a low-pass filter, and the BER analyzer. The optical fiber serves as the central transmission channel. Key simulations parameters used in this system are given in

Table 1.

The simulation is run through five iterations, corresponding to fiber lengths from 50 to 150 km. By switching between iterations, students can observe the impact of fiber length on received power, BER, Q-factor, and the eye diagram. The BER analyzer provides access to the eye diagram, a fundamental and intuitive tool for analyzing digital transmission parameters [

23,

24,

25,

26]. An example eye diagram obtained through simulation is shown in

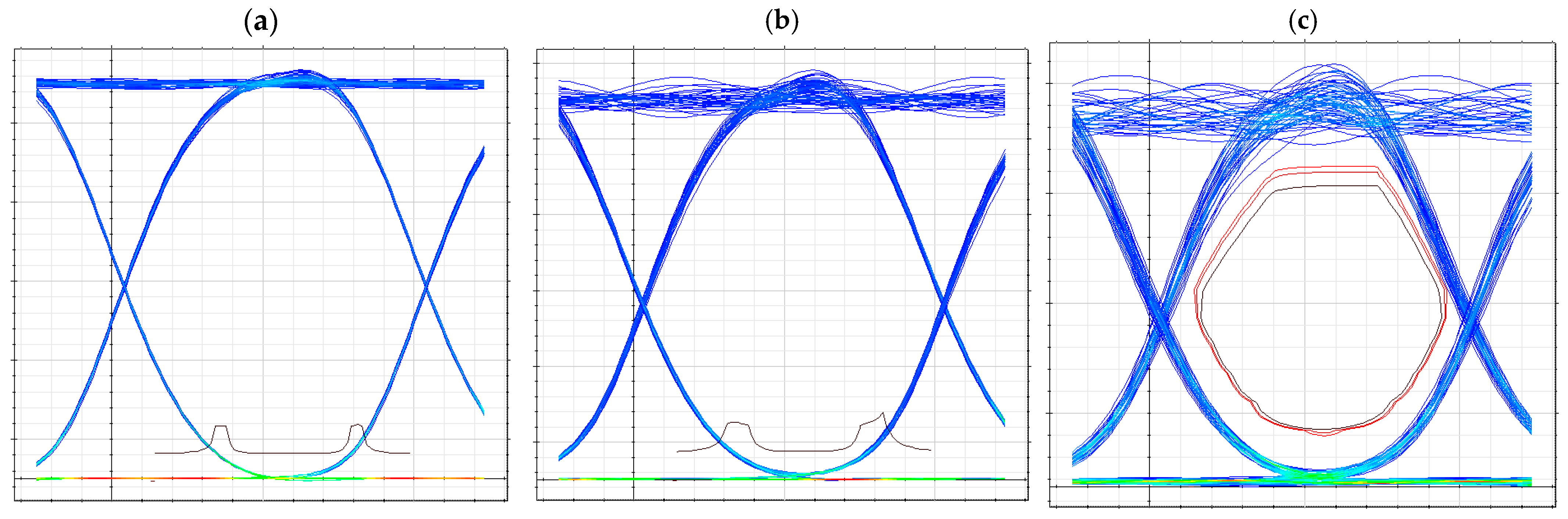

Figure 2.

The eye-diagram representation makes key transmission parameters easily interpretable, including the signal-amplitude scale, which enables direct observation and precise measurement (using the built-in markers available in the BER analyzer) of quantities such as rise time, fall time, eye height, eye width and jitter. Based on these primary measurements, additional metrics such as noise level, eye opening and the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) can be calculated. These parameters are essential for evaluating signal integrity and overall system performance, and students are encouraged to extract them directly from the eye diagram to reinforce their understanding of fiber-optic signal characteristics.

As shown in

Figure 2, in addition to the eye diagram, the BER analyzer reports the quality factor (Q-factor) and the bit error rate (BER). The BER quantifies the accuracy of data transmission and is defined as the probability that a transmitted bit is incorrectly received [

27,

28].

Figure 3 presents three eye diagrams corresponding to fiber lengths of 50 km, 100 km, and 150 km, illustrating how transmission distance affects signal quality.

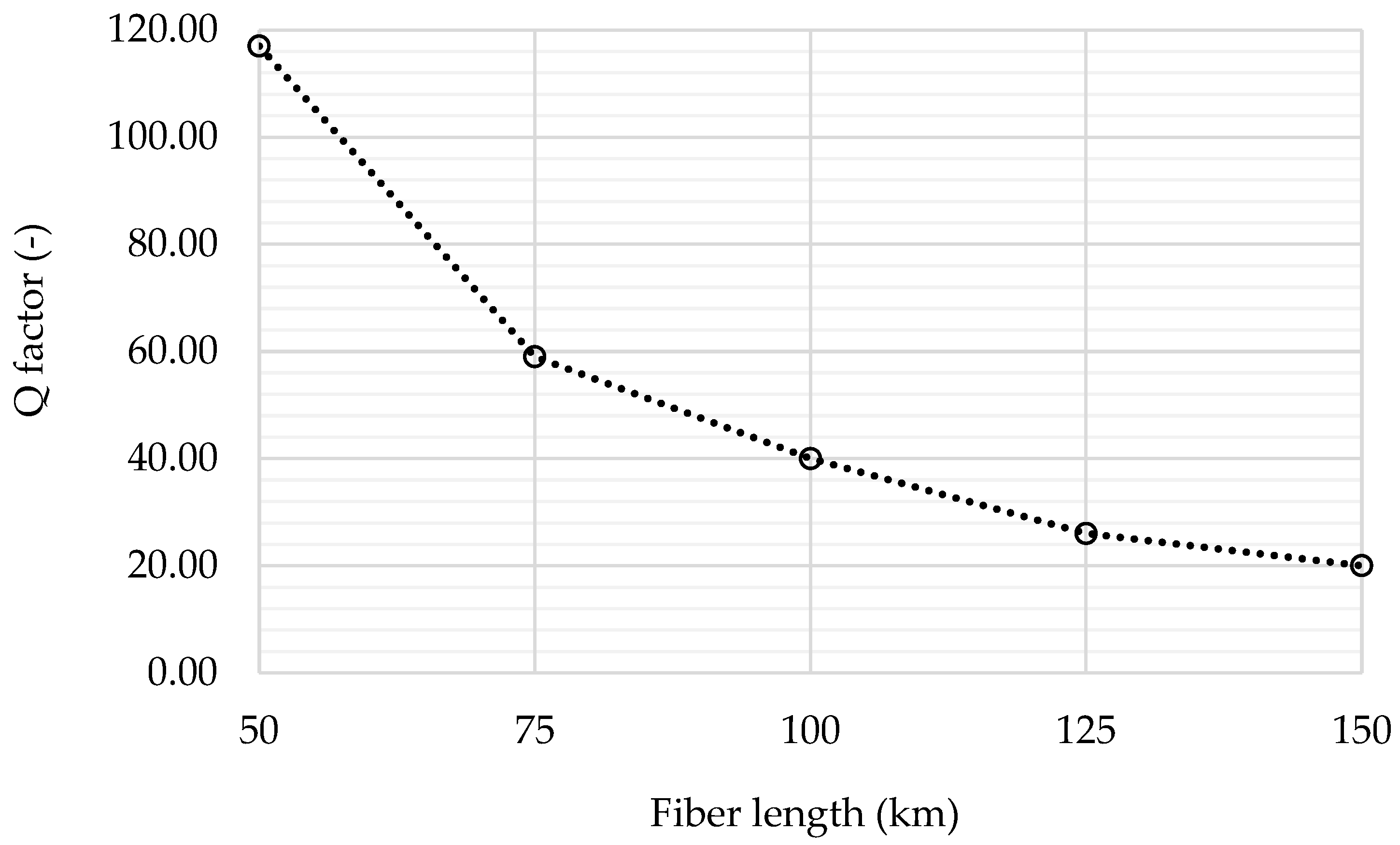

To further illustrate the impact of transmission distance on system performance,

Figure 4 shows the Q-factor as a function of fiber length. As the distance increases from 50 km to 150 km, the Q-factor decreases significantly, from approximately 120 at 50 km to about 20 at 150 km. This trend reflects the progressive degradation of signal quality caused by chromatic dispersion and attenuation over longer fiber spans, leading to higher intersymbol interference and reduced system performance.

Even this basic optical transmission system can be highly effective in teaching. Eye diagram analysis actively engages students and allows instructors to verify comprehension. The low hardware requirements and free availability of OptiPerformer enable students to install it on personal computers. In distance learning, students can share their screens (e.g., via MS Teams or Zoom) and submit exercise reports electronically. In classroom settings, the learning outcomes are nearly identical, with the main difference being in-person clarification of doubts and paper-based reporting. This flexibility is particularly valuable in times of frequently changing teaching conditions.

4.2. Dispersion Compensation

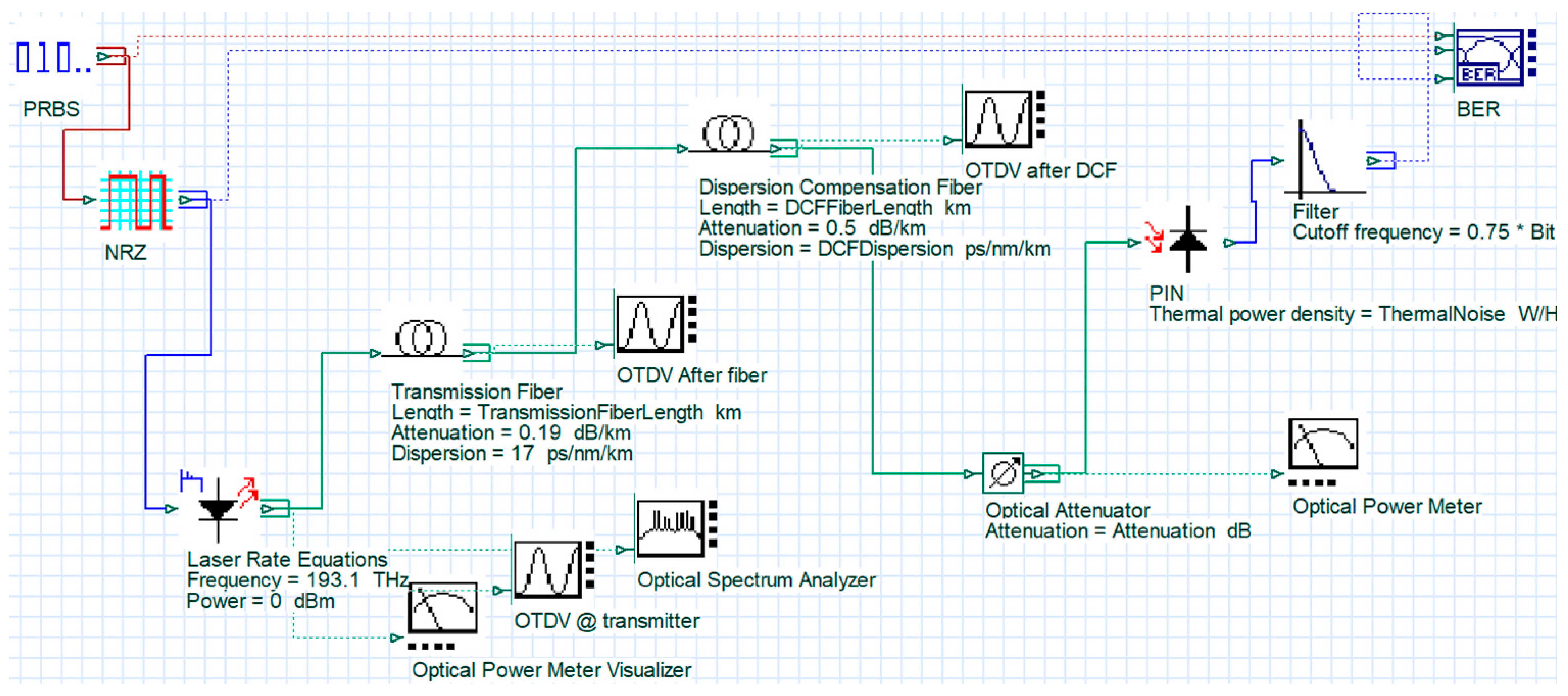

The second exemplary system, shown in

Figure 5, is a more complex fiber-optic setup that enables the design and simulation of a link using dispersion-compensating fiber (DCF) to reduce chromatic dispersion [

29,

30,

31].

Chromatic dispersion in the transmission fiber is counteracted by the negative dispersion of DCF, and the total dispersion is calculated using the relationship [

32,

33]:

where

and

are the chromatic dispersion coefficients of the transmission and compensating fibers, respectively, and

is the transmitter spectral width. Total allowable attenuation is also considered in determining optimal fiber lengths.

The system is simulated in OptiPerformer with the same virtual measurement tools as in the previous case study (optical power meter, BER analyzer, and additionally Optical Time Domain Visualizer—OTDV). Key simulations parameters used in this system are given in

Table 2.

Before starting the simulation, each student calculates the lengths of the transmission fiber (L

TF) and the dispersion-compensating fiber (L

DCF) based on standard formulas from the literature [

30,

31] and provided system parameters, including transmitter wavelength, bit rate, fiber attenuation, and receiver sensitivity. To ensure independent work and foster deeper understanding, students can manipulate multiple parameters, including transmission fiber length, DCF length, and wavelength. Slight variations in input data among students (e.g., different wavelengths or fiber characteristics) further promote individualized exploration, which is particularly beneficial in distance-learning scenarios.

Students record results in tables, including simulated and calculated power losses, and analyze the effect of varying fiber lengths and wavelength on dispersion and signal quality. Visualization of the transmitted signal using the eye diagram and OTDV further enhances understanding of pulse broadening and compensation, while the BER provides a quantitative measure of transmission fidelity, directly linking design choices to system performance. This hands-on approach engages students in both computational and experimental analysis, fostering critical thinking and reinforcing theoretical knowledge. Despite the manipulable parameters, the exercise is structured so that students can safely explore the system without risk of invalid configurations, making it intuitive and approachable even for beginners.

The exercise allows students to directly compare theoretical predictions of power loss and dispersion with simulation results, reinforcing their understanding of how DCF can compensate for chromatic dispersion in a transmission link. Importantly, students can observe in real time how changes in fiber lengths and wavelength affect performance metrics such as BER and the eye diagram, providing immediate feedback on the impact of their design decisions.

Beyond theoretical validation, this approach demonstrates that even complex fiber-optic systems can be effectively taught using simulation software, with outcomes comparable in distance and in-lab settings, thanks to the manipulable parameters, real-time performance feedback, and accessibility of OptiPerformer.

4.3. Gaussian Pulse Propagation

The third exemplary exercise focuses on the propagation of Gaussian pulses through a single-mode optical fiber [

34,

35], allowing students to compare theoretical predictions of pulse broadening with simulation results. The fiber is modeled as a linear system characterized by an approximately Gaussian transfer function

. When a directly modulated laser diode with a spectral width much larger than the signal bandwidth is used, the system response can be expressed as [

34,

35]:

where

represents the RMS width of the fiber impulse response, calculated as [

34,

35]:

with

being the fiber length,

the chromatic dispersion coefficient, and

the RMS spectral width of the source. A Gaussian chirped pulse serves as the input signal, with RMS width

and chirp factor

. The RMS width is related to the FWHM by

[

36,

37]. The output pulse RMS width is then given by [

34,

35]:

Students first calculate theoretical values for , , , and using provided system parameters (bit rate, fiber length, chirp factor, operating wavelength, and fiber dispersion constants). These calculations allow them to anticipate pulse broadening due to chromatic dispersion.

Next, the exercise is performed in OptiPerformer.

Figure 6 shows the transmission system used for this purpose. Key system parameters are given in

Table 3.

The simulation generates the input and output pulses, which can be visualized using the Optical Time Domain Visualizer. Students measure pulse width (full width at half maximum—FWHM) and signal power at both input and output and examine spectral broadening using the Optical Spectrum Analyzer. Results are recorded in laboratory reports and compared with theoretical predictions.

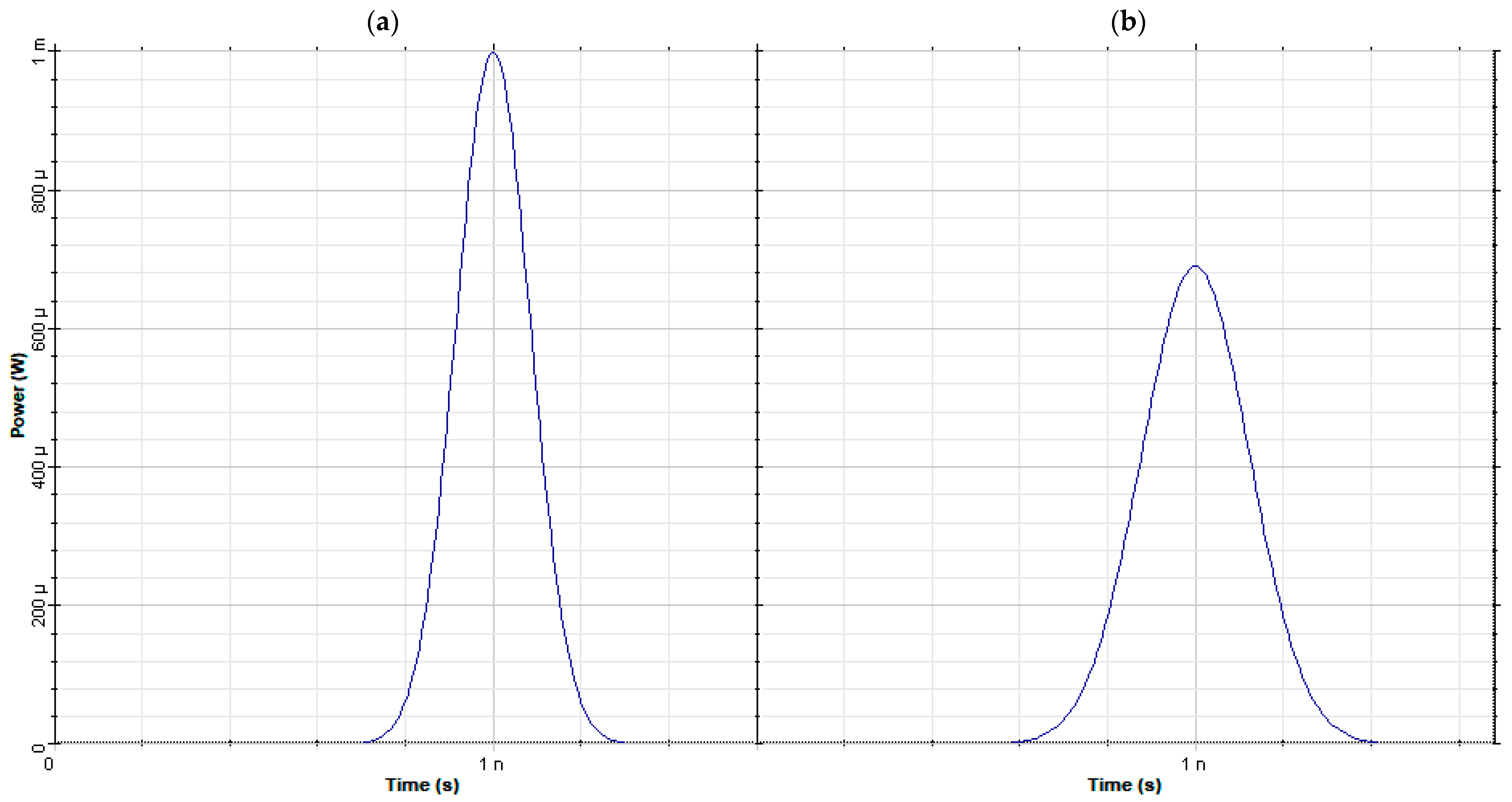

Figure 7 shows the time-domain representation of the two pulses, clearly illustrating that the waveform has broadened during propagation. The left plot presents the input Gaussian pulse with a narrow temporal width and high peak power, representing the initial condition before transmission. The right plot shows the corresponding pulse after propagation through the optical fiber. The waveform exhibits significant broadening and a reduction in peak amplitude, caused primarily by chromatic dispersion and fiber attenuation. Dispersion spreads the pulse in time, increasing intersymbol interference, while attenuation reduces its optical power. These effects become more pronounced with longer fiber lengths or higher dispersion coefficients, demonstrating the critical influence of fiber parameters on signal integrity.

In the optical time-domain visualizer panels of OptiPerformer (such as those shown in

Figure 7), built-in measurement markers allow for precise determination of the temporal and amplitude characteristics of both the input and output pulses, ensuring that the mathematical analysis can be directly verified within the simulation environment.

This exercise additionally allows students to visually and quantitatively connect the spectral width of the pulse with its temporal broadening, reinforcing the link between theoretical calculations and intuitive understanding. It provides a hands-on demonstration of pulse broadening in optical fibers, bridging analytical models and simulated signals. By integrating both computational and visualization tools, students gain an intuitive understanding of dispersion effects and develop critical skills in fiber-optic system analysis.

4.4. Summary of Laboratory Exercises

The presented set of laboratory exercises demonstrates how OptiPerformer can be employed to teach both fundamental and advanced aspects of fiber-optic communication systems. Starting from a basic optical link with eye diagram analysis (

Section 3.1), progressing through dispersion compensation using DCFs (

Section 3.2), and concluding with Gaussian pulse propagation and spectral broadening analysis (

Section 3.3), students engage with both theoretical and practical aspects of optical transmission.

Across all exercises, students perform calculations based on established formulas, simulate the systems in OptiPerformer, and compare theoretical predictions with simulated outcomes. This consistent link between theory and simulation not only reinforces conceptual understanding but also highlights the educational value of using simulation tools. The integrated approach fosters a deeper comprehension of fiber-optic principles, including signal attenuation, chromatic dispersion, pulse broadening, and eye diagram interpretation.

It should be noted that despite lacking detailed runtime reporting, OptiPerformer executed all configurations in under one second. This near-instant feedback is pedagogically beneficial, enabling students to iterate rapidly between theoretical calculations and simulation outcomes.

The low hardware requirements and free availability of OptiPerformer allow these exercises to be conducted on personal computers, enabling seamless integration of distance learning and on-site instruction. By combining hands-on simulation with theoretical analysis, the exercises not only reinforce core concepts in optical communications but also cultivate critical thinking and problem-solving skills, preparing students for more advanced coursework and practical applications in optoelectronics.

5. Evaluation of Learning Experiences

To evaluate students’ perceptions and the educational impact of using OptiPerformer in teaching fiber-optic systems, data were collected through systematic, university-wide surveys conducted at the University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn (UWM). These surveys are fully anonymous, computer-based, and accessible via smartphone, tablet, or personal computer, allowing students to complete them remotely while ensuring confidentiality of responses.

Student feedback was obtained using a standardized institutional questionnaire administered at the end of each semester. The survey included both closed and open-ended questions. Closed questions employed Likert-type scales (1–5 or 1–3) and Yes/No responses to assess key aspects such as clarity of instructions, alignment with the syllabus, effectiveness of teaching methods, achievement of learning outcomes, and teacher–student interaction. Open-ended questions provided space for additional comments and suggestions.

It should be noted that the instructor does not have access to the number of responses submitted. Survey results become available only after analysis by the Faculty Committee for Teaching Quality Assurance which verifies that the data are representative and significant before releasing aggregated results to instructors. This ensures the reliability and validity of the evaluation process.

This approach ensured that the evaluation process was systematic, transparent, and directly informed continuous improvement of the learning experience.

The surveys analyzed in this study specifically relate to the Optoelectronics course offered within the Mechatronics program at the Faculty of Technical Sciences, UWM, covering four academic years: 2020/2021 (distance learning), 2021/2022 (distance learning), 2022/2023 (in-class), and 2023/2024 (in-class). Student participation numbers are summarized in

Table 4.

After completing the course, students filled out standard course surveys providing detailed feedback on laboratory exercises, teaching methodology, and the overall learning experience. The anonymity and digital format encouraged honest and independent responses, offering reliable insights into students’ engagement, comprehension, and satisfaction with both remote and in-lab learning environments. These responses provide a strong evidence base for evaluating the effectiveness of OptiPerformer as a platform-based educational tool and informing improvements in the design and delivery of laboratory sessions.

5.1. Survey Results

Quantitative results were analyzed using mean and median values, while qualitative comments were reviewed to identify recurring themes. Representative positive feedback emphasized the clarity of laboratory instructions and the usefulness of simulation tools, including the possibility of screen sharing with the instructor via external software (e.g., MS Teams). Constructive feedback primarily concerned expanding the instructor’s comments on submitted reports and was incorporated into subsequent iterations of the laboratory.

The quantitative survey results consistently indicate that learning outcomes were independent of teaching mode, highlighting the robustness of the OptiPerformer platform. All students reported that the course content was fully aligned with the syllabus (100% positive responses) and that laboratory sessions were effectively timed and structured (100% positive responses). Students found the exercises understandable, engaging, and motivating, and they recognized the value of active interaction with simulation tools for developing practical skills and analytical competencies (100% positive responses).

The platform allowed students to explore system behavior, adjust parameters, and immediately observe the effects of their decisions on key performance indicators such as BER, eye diagrams, and spectral characteristics, thereby reinforcing conceptual understanding through interactive, hands-on learning.

5.2. Instructor’s Perspective

From the instructor’s perspective, OptiPerformer provides significant advantages as a flexible, platform-mediated teaching environment. Each student can independently execute laboratory exercises, ensuring full individual engagement—an important improvement over traditional laboratory settings, where practical work often relies on group collaboration and can result in unequal participation. The platform supports seamless interaction between students and instructors: learners can share their screens during online sessions, submit screenshots or digital reports, and receive immediate feedback. These features enable personalized guidance and continuous monitoring of student progress, independent of physical location.

5.3. Adaptive Learning

The platform also enables parameterized and adaptive learning experiences, allowing instructors to create exercises that can be adjusted to individual student inputs, such as fiber length, wavelength, or dispersion-compensating fiber properties. By combining real-time visualization, immediate feedback, and pre-defined safe configurations, OptiPerformer functions as a controlled yet flexible digital laboratory platform, allowing students to experiment confidently while developing problem-solving skills.

5.4. Grade Analysis

In addition to survey-based feedback, analysis of final course grades provides further quantitative evidence of the platform’s effectiveness.

Table 5 presents the average final grades across the four academic years.

As shown in

Table 5, across the four academic years, the average final grades in the Optoelectronics course were consistently high, with a mean of 4.09 for the distance-learning semesters and 4.04 for the in-class semesters. The small difference between these averages suggests that students’ learning outcomes were comparable regardless of the teaching mode, indicating that the use of OptiPerformer effectively supports the acquisition of practical knowledge and skills in both remote and traditional laboratory environments. This consistency further confirms that the software can be a reliable tool for flexible teaching while maintaining high educational standards.

5.5. Key Attributes of OptiPerformer

Taken together, the survey and grade analysis underscore several key attributes of OptiPerformer as a platform technology for education:

Accessibility and inclusivity—the software is free, low in hardware requirements, and can be installed on personal devices, enabling broad participation;

Integration of theory and practice—students can compare calculated theoretical outcomes with simulated results, strengthening conceptual understanding through active exploration;

Flexibility across teaching modes—both remote and in-lab students engage with the same platform, enabling seamless transitions between modalities;

Real-time interactivity—immediate visualization of system responses to parameter changes supports experiential learning and the development of analytical reasoning;

Individual accountability and engagement—each student independently completes exercises, ensuring full participation and measurable learning outcomes.

By providing a unified, interactive environment for both distance and in-person education, OptiPerformer exemplifies a specialized educational platform that integrates simulation, visualization, and interactive feedback. It enables instructors to deliver high-quality laboratory experiences while allowing students to engage actively with system behavior, independently explore configurations, and internalize complex concepts. This combination of flexible accessibility, platform-mediated interactivity, and measurable learning outcomes showcases how digital platforms can bridge theoretical knowledge and practical application in technical education.

Overall, the results confirm that OptiPerformer serves not merely as simulation software, but as a robust platform for teaching, learning, and experimentation in optical communications, supporting both effective knowledge acquisition and skill development.

6. Conclusions

The article presents the use of OptiPerformer software in simulation-based laboratories for optical fiber systems. While the initial focus was on distance learning, the demonstrated methods are equally applicable in traditional classroom and laboratory settings, allowing rapid adaptation of teaching in response to unexpected circumstances, such as a pandemic or instructor absence. The capabilities of OptiPerformer were illustrated through exercises covering fundamental fiber-optic systems, dispersion compensation, and Gaussian pulse propagation, with a strong emphasis on students’ independent engagement, including computational tasks and analysis of simulation results. The discussion draws on four semesters of teaching experience, encompassing both student feedback and final course grades.

The findings indicate that OptiPerformer provides a highly effective and accessible approach to teaching optical fiber systems and optoelectronics. The software enables visualization and simulation of complex optical phenomena, supporting students’ understanding of key concepts such as attenuation, chromatic dispersion, pulse broadening, and signal distortion. Its free availability and low hardware requirements remove common barriers in engineering education, allowing students to engage with realistic, interactive simulations that closely reflect real-world experimental conditions, whether in remote or in-person learning contexts.

Survey results and final grades across the four academic years consistently highlight the educational value of this approach. Students reported clear, engaging, and motivating laboratory experiences, and learning outcomes were consistently high, with minimal differences between distance and in-class teaching. These findings confirm that combining guided simulation tasks with independent exploration enhances analytical thinking, problem-solving skills, and self-directed learning. The integration of theoretical calculations with hands-on simulation, as emphasized in prior studies [

38,

39,

40], further reinforces conceptual understanding and practical competencies.

Based on these results, the implementation of OptiPerformer in optoelectronics and fiber-optic courses is strongly recommended. It enhances flexibility, accessibility, and learning outcomes while fostering both conceptual knowledge and practical skills. Beyond supporting traditional and remote teaching, OptiPerformer exemplifies how platform-based educational technologies can bridge theoretical understanding with interactive, application-oriented learning, aligning with broader trends in digital education and smart learning environments. Future work may explore integration with advanced e-learning platforms, virtual reality (VR), or augmented reality (AR) to further enrich the interactive experience and expand the scope of simulation-based education.

In addition to its pedagogical value, the presented work carries direct significance for the field of fiber-optic communication. The simulation tasks implemented in OptiPerformer reflect core mechanisms that underpin modern optical systems, including attenuation, dispersion management, pulse shaping, receiver sensitivity, and system-level performance evaluation. By engaging with realistic link configurations and analyzing system responses, students develop competences that are directly transferable to engineering practice, particularly in areas such as link design, dispersion compensation strategies, and assessment of transmission impairments. In this way, the proposed simulation-based laboratory framework contributes to strengthening the training pipeline for future fiber-optic communication specialists.