Abstract

Three-dimensional human pose estimation (3D HPE) refers to converting the input image or video into the coordinates of the keypoints of the 3D human body in the coordinate system. At present, the mainstream implementation scheme of a 3D HPE task is to take the 2D pose estimation result as the intermediate process and then return it to the 3D pose. The general difficulty of this scheme is how to effectively extract the features between 2D joint points and return them to 3D coordinates in a highly nonlinear 3D space. In this paper, we propose a new algorithm, called TSHDC, to solve the above dilemma by considering the temporal and spatial characteristics of human joint points. By introducing the self-attention mechanism and the temporal convolutional network (TCN) into the 3D HPE task, the model can use only 27 frames of temporal receptive field to make the model have fewer parameters and faster convergence speed when the accuracy is not much different from the SOTA-level algorithm (+6.8 mm). The TSHDC model is deployed on the embedded platform JetsonTX2, and by deploying TensorRT, the model inference speed can be greatly improved (13.7 times) with only a small loss of accuracy (5%). The comprehensive experimental results on representative benchmarks show that our method outperforms the state-of-the-art methods in quantitative and qualitative evaluation.

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of machine learning, people have gradually come to understand human–computer interaction as a multimodal form of human–computer interaction [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. It is in this context that a large number of computer vision tasks have been proposed, and human pose estimation (HPE) is one of the fundamental and challenging research directions. With the rapid development of neural networks in computer vision, the emergence of new algorithms has provided more solutions for 3D human pose estimation tasks. However, applying the best neural network algorithms to 3D human pose estimation remains a key research topic with broad research prospects. Furthermore, the ability of human pose estimation technology to be implemented in embedded systems is a key indicator of its application value. Considering the advantages of embedded systems, such as their small size, high real-time performance, and scalability, combining human pose estimation technology with them allows for the application of human pose recognition systems in more complex environments with higher performance requirements. Research on embedded implementations of 3D human pose estimation technology has great application value.

2. Background

In the following content, we mainly introduce the main problems faced by 3D human pose estimation based on monocular video, the research content and results of predecessors, and the main contributions of the new human pose intelligent detection algorithm.

2.1. Main Problems

Currently, there are three main problems in 3D human pose estimation based on monocular video:

The first problem is the depth ambiguity problem. In principle, the 3D HPE task based on monocular video aims to recover the three-dimensional joint coordinates of the human body from the monocular video. In essence, it is to infer high-dimensional information through low-dimensional information. But there is a problem that runs through the whole process; that is, a point in two-dimensional space has multiple points corresponding to it in three-dimensional space. This means that even if the three-dimensional posture restored by the model is consistent with the detection image in the two-dimensional plane projection, it may be different from the spatial posture of the target image. Some researchers have added constraints to the model through model-based methods, or solved it from the perspective of the time domain, using continuous multi-frame image prediction in the time domain to exclude those points whose Euclidean distance in adjacent time domains is too large.

The second issue is occlusion. This means that areas of the human body in the detected video may be obscured, thus affecting the accuracy of pose estimation. Occlusion problems can be categorized into three types, depending on the source of the occlusion: self-occlusion, occlusion by other human bodies, and occlusion by other objects. The loss or even misleading of true joint information will significantly impact 3D HPE tasks. Missing keypoint regions not only affect the prediction of individual joints. For example, many model-based algorithms rely on modeling the human body or partial limbs, and missing keypoints can affect the overall model prediction. When the occlusion problem originates from other human bodies, the impact is even more severe because the joints of other human bodies may be used to predict the current human body model. Therefore, the occlusion problem requires the algorithm to be able to predict the target joints based on other human joints or to eliminate incorrect joints, requiring the extraction of more complex features.

This paper aims to design a regression algorithm, TSHDC, that can comprehensively consider both temporal and spatial features between 2D joints and map them to 3D joints. Using 2D keypoints as an intermediate step, 2D to 3D lifting undoubtedly provides a better solution for the 3D HPE task. On the spatial side, the processing involves learning spatial features between 2D keypoints through a multi-head self-attention mechanism [10]. On the temporal side, a sequence of consecutive 2D keypoint frames is used as input instead of a single frame, allowing the model to learn the dynamic temporal structure between the keypoints of the predicted frame and the preceding and following frames.

2.2. Preparation of Knowledge

2.2.1. Model-Based 3D Human Pose Estimation Method

Considering that the posture of the human body comes from the spatial orientation of the bones and the movement of the human body, researchers often estimate the posture of the human body by establishing kinematic models or volume models. Many methods estimate 3D human pose by establishing prior knowledge of kinematic models such as bone length constraints, joint rotation constraints, and joint point position constraints [11,12,13]. A typical approach for this type is to parameterize the 3D part segments by embedding a set of joint positions and limb orientation or manikins as constraints into the network layer. With the deepening of research, researchers often do not stick to the fixed structure but instead use some more subtle parameters to adjust the original model. For example, the degree of freedom of some joint points in the human body [14] (Degrees of Freedom, DOF) is added, and the fixed model is preserved by judging local motion characteristics [15]. Some researchers have found that the noise of 2D keypoints affects the accuracy of 3D poses [16], so they designed kinematic models for 2D unreliable points to refine the structure. Since simple human skeletal models are difficult to recover human shape information, other researchers use volumetric models to reconstruct human pose grids [17,18,19]. Unlike kinematic models that only require partial joint points, volume models tend to require more joint point information or contour information. The skinned multi-person linear model (SMPL) [20] is the most widely used volume measurement model today. A human mesh model and a skeleton model are defined in the SMPL model, and the standard human pose network is obtained by calculating the skin weight of each vertex and skeleton and the deformation variables with identity shape parameters, and the pose network is returned to the human keypoints. Most of the attitude estimation work relying on the SMPL model is regression to the SMPL grid parameters.

2.2.2. Mixed Dilated Convolution

Dilated convolution was first proposed in the field of image segmentation, where it increases the receptive field by inserting spaces between adjacent elements of the convolution kernel. Similar effects to dilated convolution can be achieved through downsampling and increasing the depth of convolutional layers; however, downsampling involves sampling at intervals, which undoubtedly leads to a loss of data integrity and reduces spatial resolution. Furthermore, merely increasing the depth of convolutional layers often results in problems such as overfitting and vanishing gradients. Dilated convolution effectively resolves these issues by employing convolutional kernels of varying scales and dilation rates, thereby enhancing the learning of contextual relationships while maintaining data integrity. In the one-dimensional case, let the input signal be denoted as , and let the filter of length l be denoted as , with r representing the dilation rate. The dilated convolution formula can be expressed by Equation (1).

where g(i) is the value of the output signal at position (i), f is the input signal, h(l) is the weight of the L-length filter at position l, r is the expansion rate, and indicates the location of the expansion filter receptive field.

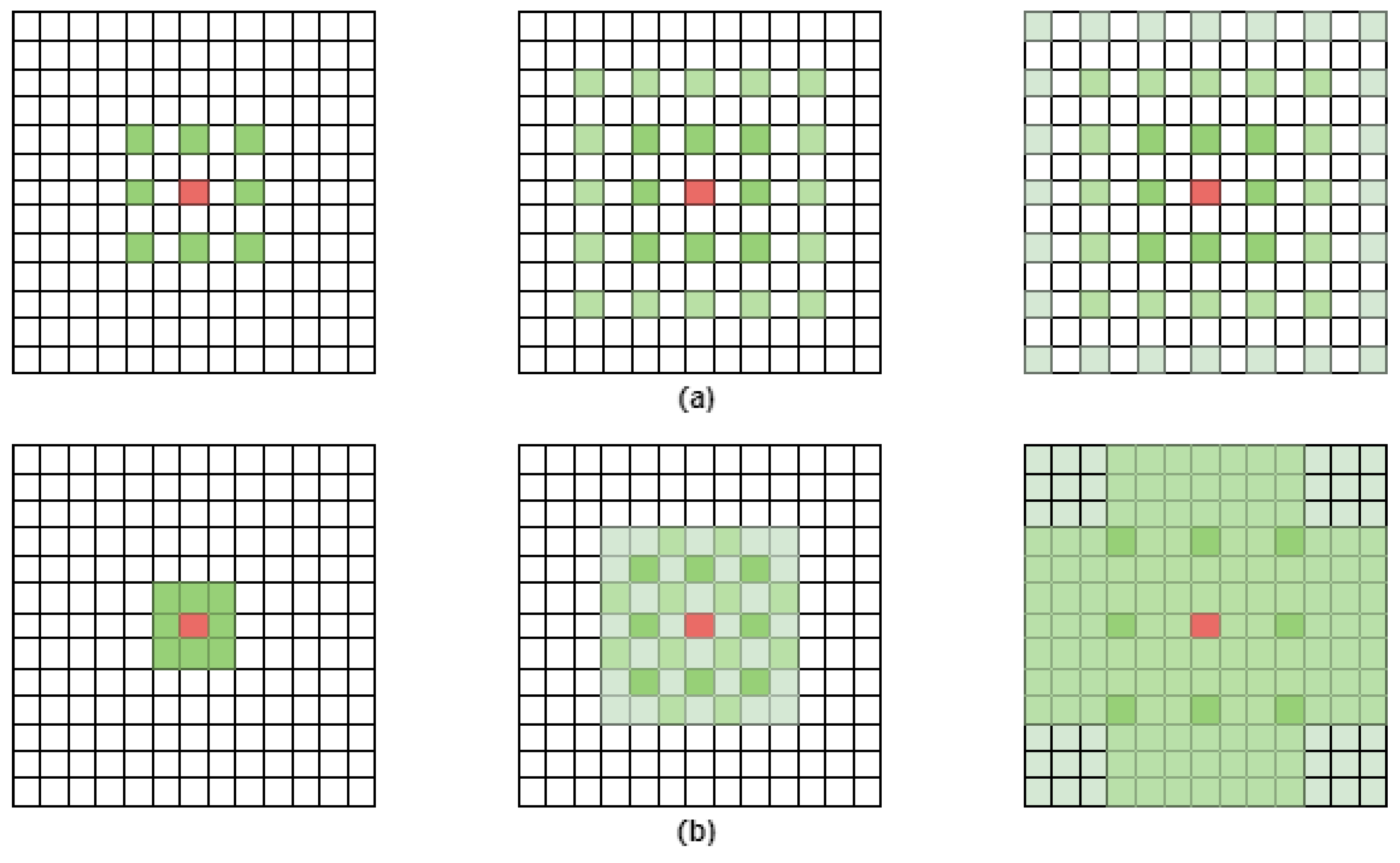

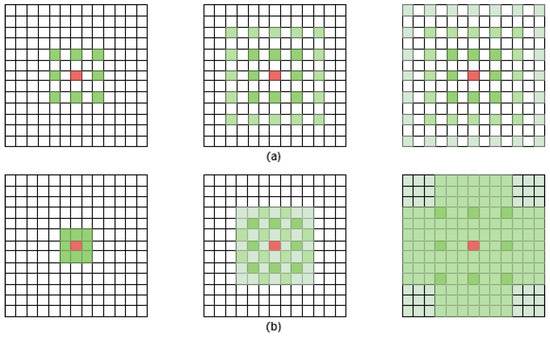

However, dilated convolution results in two main problems. The first issue is the grid effect. For a matrix employing dilated convolution, as illustrated in Figure 1a, the information around pixel P, the multiplied weight of 0, leads to the loss of most of the surrounding information. As the number of layers increases, the input samples become very sparse in the initial layers, which hinders learning. The second issue is that long-distance information may be irrelevant, which does not benefit learning. In light of this, Wang et al. [21] proposed a simple yet effective hybrid dilated convolution (HDC). The paper demonstrates that to ensure that the final size of the receptive field after convolution covers a square area without any gaps or missing edges, the maximum distance between two non-zero values should satisfy Formula (2).

Figure 1.

(a) ordinary convolution receptive field (b) receptive field in HDC.

We compared the sizes of the receptive fields between standard convolutions and those in HDC.

Reference [21] has been experimentally verified to demonstrate that designing a sawtooth-shaped dilation rate can meet the condition of setting the dilation rates to [1, 3, 5, …]. The sawtooth-shaped dilation coefficients can increase the receptive field while keeping the top-level receptive field unchanged. As shown in Figure 1b, the receptive field of the HDC preserves the integrity of the data. Moreover, HDC exhibits strong generalizability and can be integrated into other networks without the need for additional modules.

3. Spatiotemporal Mixed Dilated Convolution Model for Human Pose Intelligent Detection Algorithm

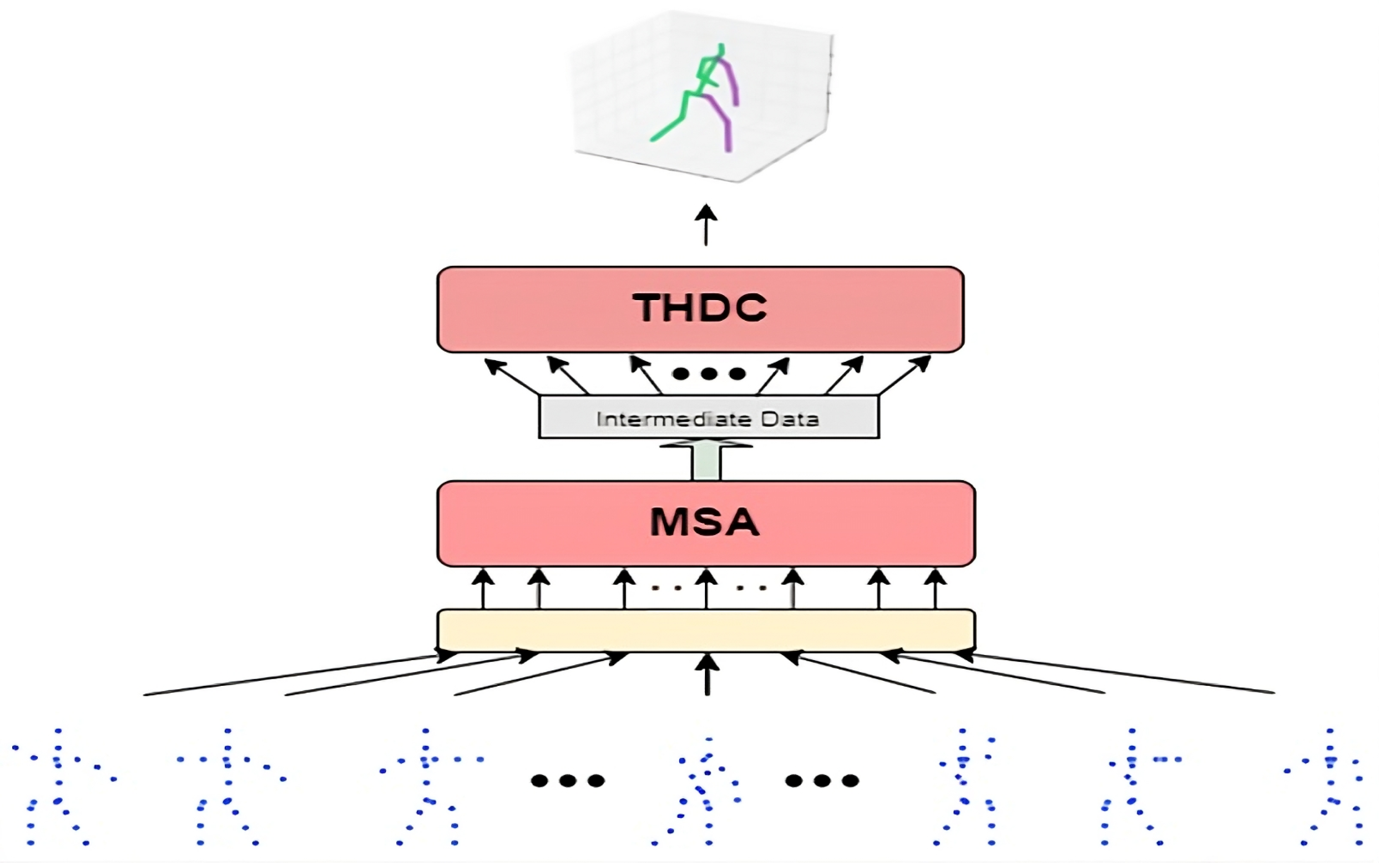

3.1. System Model

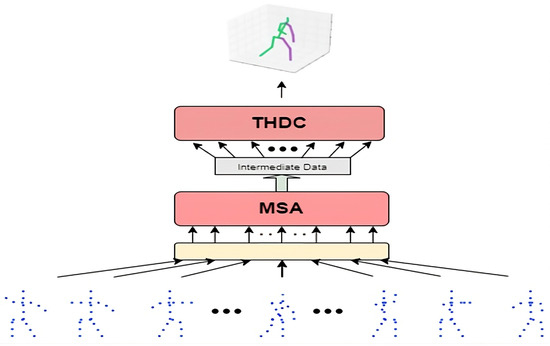

The main part of the spatiotemporal hybrid dilated convolution model (TSHDC) consists of a cascade of the Multi-head Self Attention Layer (MSA) and the temporal hybrid dilated convolution network (THDC). The core design concept of the TSHDC model is derived from Reference [22], an approach that has already proven effective across various cross-domain multimodal processing tasks. The overall network structure is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

System model.

The introduction of the MSA layer can, on the one hand, better learn the latent spatial features between 2D joints, and on the other hand, in the proposed TSHDC architecture, the MSA layer achieves competitive performance with a parameter count favorable to some traditional deep CNN structures, especially exhibiting greater parameter efficiency when modeling long-range spatial dependencies. In the MSA layer, the original data is preprocessed and divided into multiple subspaces, each processed using a deep Scaled Dot-Product Attention network, capturing richer feature information. Additionally, by incorporating a multilayer perceptron (multi-layer perception, MLP) structure, the mapping is transformed into a nonlinear function. The subsequent THDC model employs a TCN network for keypoint regression. Compared with traditional RNNs, the TCN network can have a more compact architecture by adjusting the depth of convolutional layers, filter sizes, and dilation rates, and it effectively mitigates the issues of gradient explosion and vanishing commonly found in RNNs. Since the output of the MSA layer remains temporally continuous 2D keypoint frames, hybrid dilated convolutions are incorporated into the TCN network to enlarge the receptive field to capture more global features while preventing gridding effects. The network is overall structured as a cascaded multi-layer residual network, where the input of every two layers is sliced and mapped to the output, further ensuring the network’s effectiveness and computational efficiency.

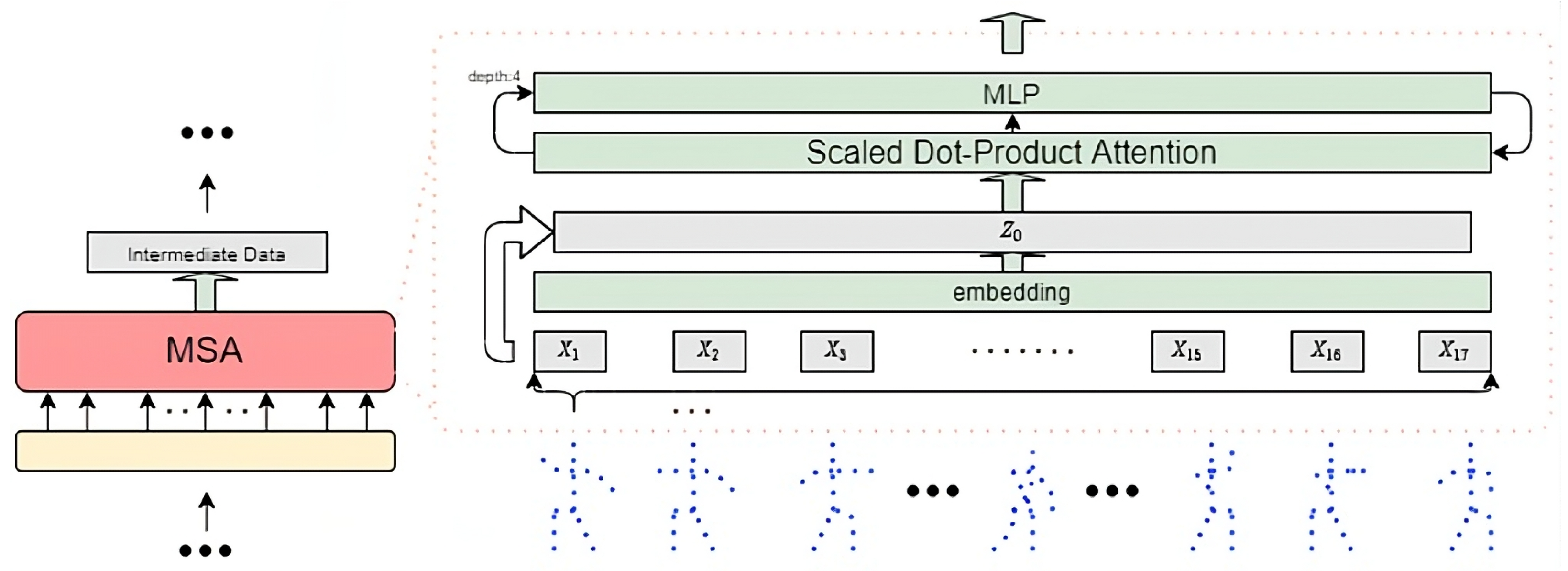

3.2. Multi-Head Self-Attention Layer

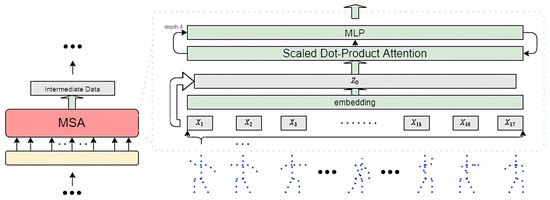

The network structure of the MSA layer is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

MSA layer network structure.

In order for the subsequent THDC network to perform temporal modeling and prediction on 2D keypoints, the MSA layer will simultaneously learn self-attention between keypoints for a sequence of consecutive 2D keypoint frames and produce outputs. In the MSA layer, the largest input unit is a frame of 2D keypoints, and the smallest data unit is a single 2D keypoint vector, which is shown in Figure 3. The maximum input unit is defined as , where J represents the 17 joint points. In 2D space, the set of 2D joint point frames is defined as . In order to amplify the features of joint point vectors and distinguish general characteristics, each keypoint vector is linearly embedded into a high-dimensional space. Meanwhile, considering the gradient vanishing problem during backpropagation in the embedding layer, inspired by ResNet [23], the joint point vectors are skip-connected to the output of the embedding layer. Let D be the dimension after mapping, then the linear mapping matrix is , the skip-connection matrix is , and the processed output matrix is . The entire process can be expressed by Formula (3).

After processing, is fed into the multi-subspace deep Scaled Dot-Product Attention network layer for feature extraction. According to the Scaled Dot-Product Attention flowchart, the multi-head self-attention computation satisfies Formulas (4) and (5).

A deep feature extraction network is established here, repeating the aforementioned process depth times. Similarly, considering the gradient vanishing problem, the input mapping of the current MSA layer is added to its output. The overall structural formulas are shown in Formulas (6) and (7).

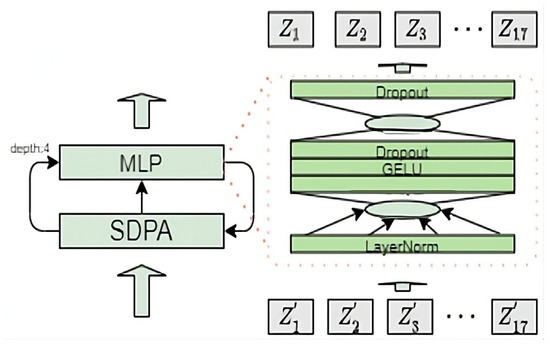

A multilayer perceptron (MLP) structure is incorporated into the attention processing mechanism. The MLP structure in this design is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The MLP structure in MSA layer.

The MLP consists of three layers: an input layer, a hidden layer, and an output layer. Each layer is fully connected to the next. In this network, represents a mini-batch of f samples, with each sample containing 17 joint point features learned through the MSA layer. Let the total input dimension be d, the number of hidden units be h, the weight matrices be and , and the bias matrices be and . The GELU activation function is employed, and a Dropout layer can be added after the activation layer to prevent network overfitting, yielding Formula (8):

The multi-head self-attention layer can be expressed by Formulas (9)–(11).

where represents a single batch normalization layer, namely the LayerNorm function.

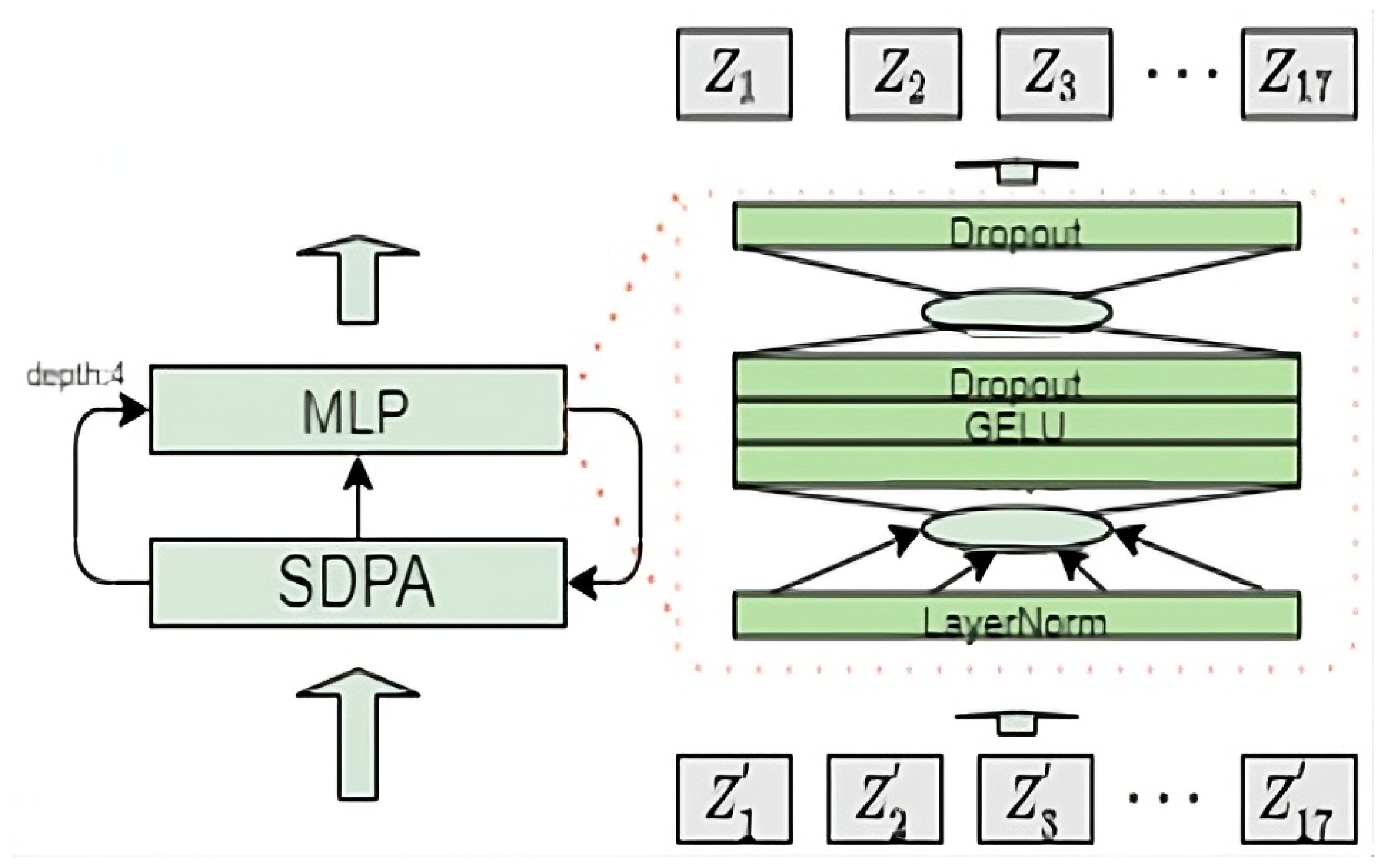

3.3. Time-Domain Hybrid Dilated Convolutional Network

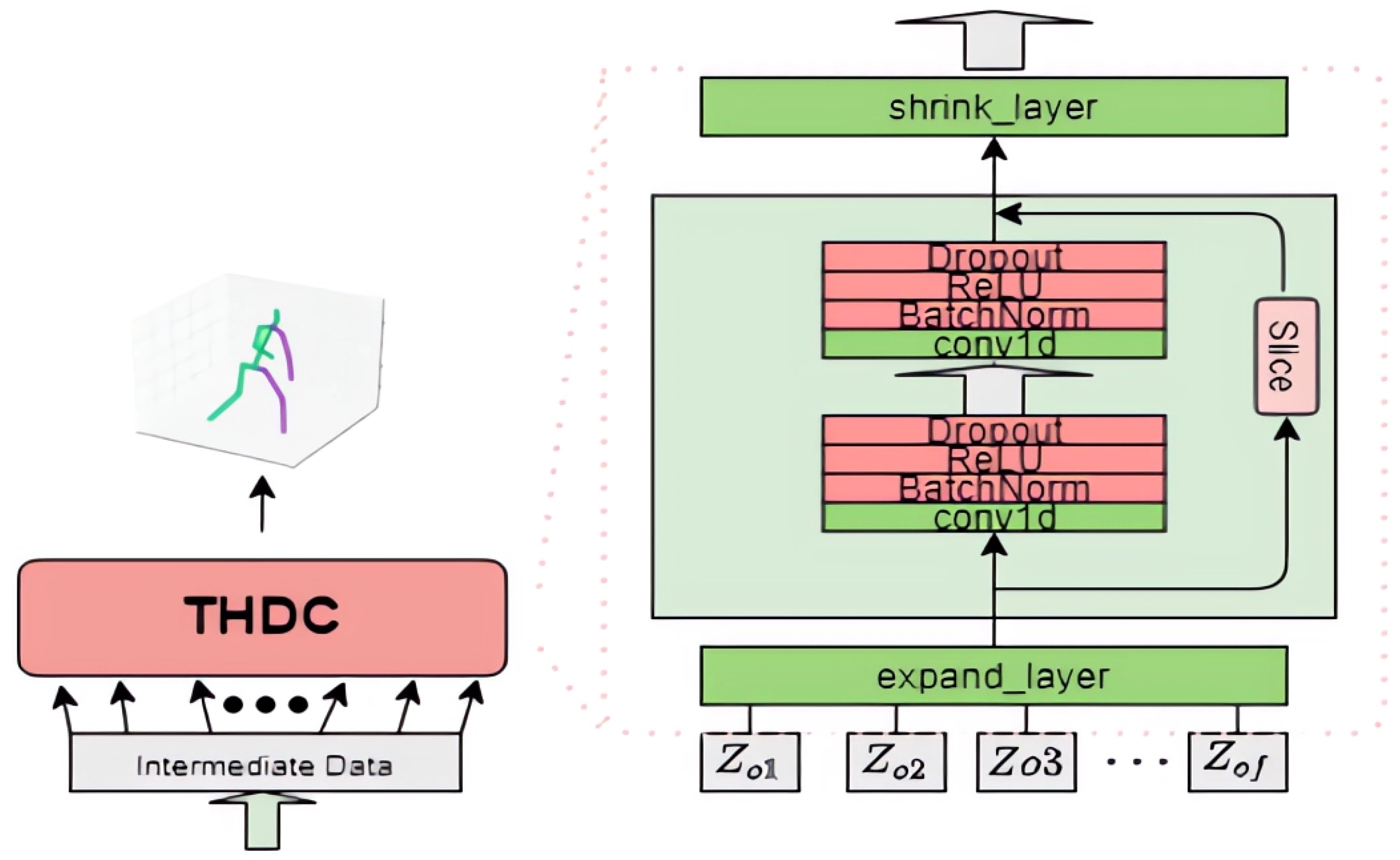

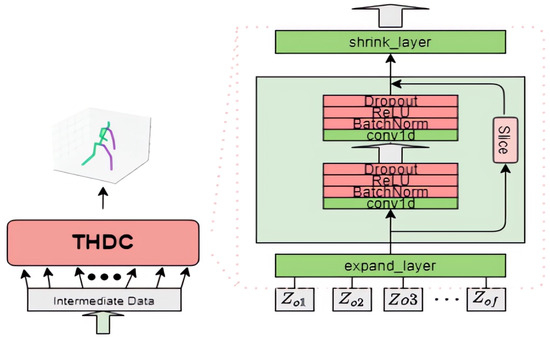

The overall architecture of the time-domain hybrid dilated convolution network (THDC) is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The overall architecture of THDC network.

This model is a hybrid dilated convolution architecture based on a TCN network, with multiple layers of residual fully connected networks. The upper-level module is the MSA layer, which outputs a sequence of learned spatial feature 2D keypoint frames. These frames are then fed into the HTCN model for temporal learning, regressing the 2D keypoints to 3D keypoints. The HTCN model can process batch samples and a series of temporal data in parallel, and during gradient computation, it has equally long gradient paths, which can effectively optimize the memory and gradient issues of RNN models. Through the design of the TCN network, this model can precisely control the receptive field, thereby introducing the crucial temporal dimension into the features learned for the 3D HPE task. At the same time, the deep residual network is applied in the overall architecture, slicing the output of the hybrid dilated convolution (HDC) with sawtooth patterns at each layer and skipping connections to the output of that layer, thereby ensuring information integrity and learning efficiency.

For the input data part, considering that the TCN network cannot directly adjust the input and output data to synchronize the time steps, the initial data should be padded to satisfy the relationship. Assuming that the receptive field is , then each batch needs to be padded with data points on both sides, using neighboring values by default.

Regarding the convolutional layers, considering that the output data of the MSA layer is not suitable for direct input into the HDC model and that the model’s output stage requires mapping the output features back to 3D joints, expand and shrink layers are designed on both sides of the main network to adjust the data accordingly. Considering that both past and future joint pairs in the 3DHPE task affect the 3D points to be predicted, non-causal temporal convolution is chosen here. The backbone network parameters follow the HDC model design. In total, there are six convolutional layers, four of which belong to the backbone network.

Let the receptive field be , the current convolutional layer index be i, the dilation factor be , the kernel size be S, the input tensor height be , and the output tensor height be . Then, the dilation factor and the input channel dimension (which corresponds to the input tensor height in the one-dimensional case) should satisfy Formulas (12) and (13).

For the input data (27, 34), the 14th frame is the center frame to be predicted. First, the data passes through the expand layer (also known as the expansion layer), which reduces the size of the original input data (to eventually regress to the center frame). For convolution operations with a dilation factor of 1, the output tensor height (i.e., the one-dimensional sequence length) can be expressed by the formula . In the first layer, is 27, F is 1, and S is 3. Therefore, the output sequence length is 25. Since the output channel number of the convolution layer is 1024, the output data after the expand layer is (25, 1024). Similarly, subsequent convolution layers undergo corresponding transformations. When passing through the second layer in the deep structure, both the kernel size S and dilation factor F are 1, so the sequence length remains unchanged. Due to the convolution operation causing differences between input and output sequence lengths, the input sequence is sliced and mapped to the output sequence. Finally, in the shrink layer (also known as the contraction layer), the one-dimensional data with 1024 channels is mapped to a one-dimensional matrix with 51 channels. After matrix transformation, the required 3D pose matrix with dimensions (17, 3) is obtained. When designing the number of input and output channels for each layer of a convolutional network, one should consider the tensor size changes caused by temporal convolution; that is, when passing through a convolutional layer with a dilation factor not equal to 1 (even-numbered layers, not considering the 6th layer which is a shrink layer), the number of output channels is not the same as the number of input channels. Two-dimensional joint video frames are regarded as one-dimensional data along the temporal dimension, with a depth of 17. The convolution kernel has a size of 3 and a depth of 17. The kernel moves along the temporal dimension with a dilation factor of 1.

4. Experimental Results and Data Analysis

4.1. Experimental Setup

The experimental environment is a PC with an X86 architecture, running Ubuntu 18.04. The GPU model is NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090. The CUDA version is 11.4. The Python version is 3.8.16. The Torch and torchvision versions are 1.11.0 and 0.12.0, respectively.

This experiment was tested on the most widely used dataset for 3D HPE tasks, HUMAN3.6M. The HUMAN3.6M dataset contains over 3.6 million video frames from 11 subjects. Among them, 3D pose data of seven subjects were annotated, while the data collected from the other four subjects were only used for testing. Each subject was required to perform 15 different actions, including sitting, lying down, walking, and others. These actions were not strictly constrained, allowing the subjects to perform more naturally. The scenes were captured by four cameras from different angles, and the pose data were collected using sensors and 10 distributed motion capture cameras.

In this experiment, the data from seven subjects annotated with 3D poses are divided into two subsets: and . The former subset is used for training, while the latter subset is reserved for testing. All training procedures employ the TSHDC model, with differences between models being solely in training parameters such as epoch.

This study adopts the mean per joint position error (MPJPE) as the evaluation metric. MPJPE is the most commonly used evaluation metric in 3D HPE tasks, defined as the average Euclidean distance between predicted joint coordinates and ground truth coordinates. Let S represent the human skeleton, denote the number of joint points in skeleton S, and f be the number of video frames. MPJPE can be expressed by Formula (14).

4.2. Comparison with Existing Technical Methods

In Table 1, the performance of some of the main 3D HPE algorithms and the TSHDC model on the HUMAN3.6M dataset in recent years is presented.

Table 1.

Comparison of TSHDC algorithm with state-of-the-art methods on Human3.6M dataset (MPJPE in mm).

As shown in Table 1, the TSHDC model still lags behind the current state-of-the-art 3D human pose estimation (3DHPE) algorithms, but it achieves reasonably good accuracy (48.4 mm). Compared with methods that utilize structures similar to multilayer perceptrons for high-dimensional mapping, the MSA layer introduced in the TSHDC model can more precisely extract spatial features among keypoints, leading to faster model convergence. In addition, the experimental results demonstrated that increasing the receptive field from 17 to 27 frames yielded a significant improvement in MPJPE. However, further expansion to 51 or 81 frames provided diminishing returns (e.g., MPJPE improvement less than 1 mm) while substantially increasing the model’s parameter count, computational latency, and memory footprint. Thus, the TSHDC algorithm adopts a 27-frame temporal receptive field as the optimal configuration, which, compared to networks using hundreds of frames, offers advantages in detection speed and data requirements, thus possessing higher practical application value.

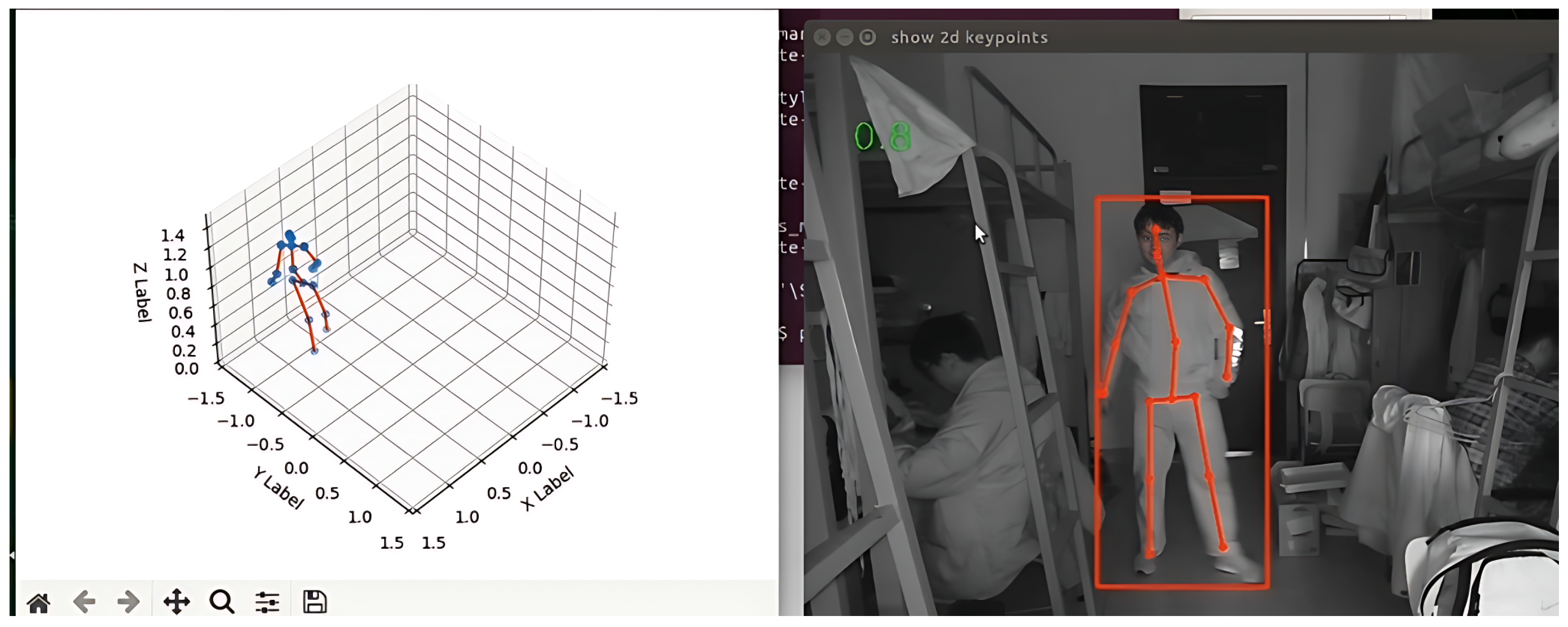

4.3. Implementation of Visual 3D HPE on the Jetson TX2 Platform

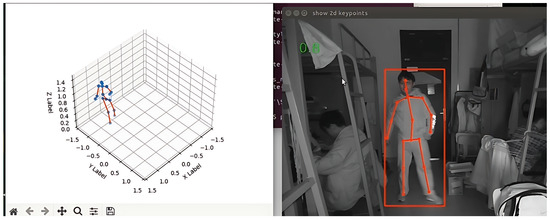

On the Jetson TX2 platform, a comprehensive scheme for visualizing real-time 3D human pose estimation (3DHPE) tasks is designed using YOLOv3 and HRNet as the 2D detection frameworks and the TSHDC model as the 3D point enhancement mode [24].

The task is divided into three stages: In the first stage, YOLOv3 is employed as a preliminary detection framework to determine whether human targets are present in the image, and based on the detected bounding boxes, the resolution of the data containing the objects is adjusted to (256, 256). In the second stage, the resulting new array (as the HRNet network requires specific input image dimensions) is fed into the HRNet network to extract 2D keypoints. In the third stage, the 2D keypoints are then input into the TSHDC model to infer the 3D keypoints. Finally, the visualization feature is implemented. The results output by the TSHDC model are 3D detection points in the camera coordinate system. By rotating the coordinates using a rotation matrix, one can obtain the 3D joint points in the world coordinate system. To implement the visualization feature, it is necessary to use arrays of human rotation chains from HUMAN3.6M, such as the rotation chains for the left leg, left hand, right hand, etc. Once the rotation chains are obtained, the chain coordinates can be easily connected using Matplotlib3.9.0 to create the visualizations. Figure 6 shows the results of a real-time 3D HPE task using the TSHDC model on the Jetson TX2. The left side shows the human skeleton in 3D space, while the right side shows the 2D detection results of the yolov3 detection framework and Hrnet on the camera input images.

Figure 6.

The real-time 3D HPE task is performed on JetsonTX2 using the TSHDC model.

4.4. Related Tests

4.4.1. Testing and Analysis of TensorRT Acceleration Effect

This experiment used the TSHDC model as the test model and evaluated the acceleration effect and accuracy loss of TensorRT on JetsonTX2. The experimental results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

TensorRT acceleration experiments.

From the data in Table 2, it can be observed that the improved model without TensorRT acceleration achieves an inference speed of 20.8 FPS, which basically meets the basic requirements for real-time detection. However, prolonged operation leads to performance degradation on embedded devices, making it unable to consistently satisfy real-time detection demands. After applying TensorRT optimization, the inference speed is significantly improved across all precision levels. Considering the trade-off between accuracy and real-time performance, this paper ultimately selects the FP16-precision TensorRT model as the optimal solution.

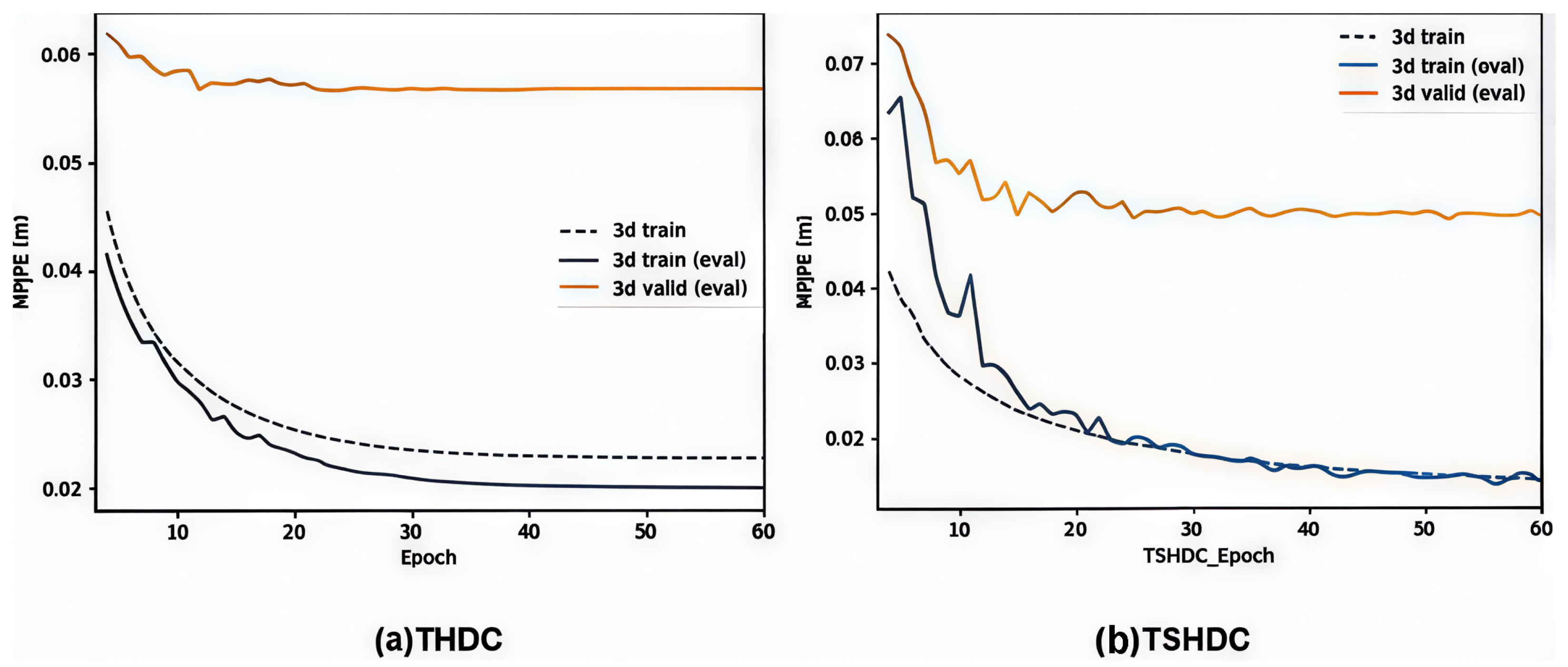

4.4.2. Ablation Experiment and Analysis of MSA Layer

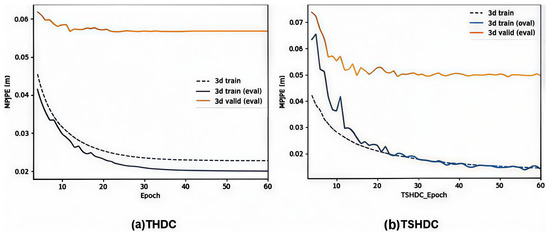

Under identical conditions including epoch number, learning rate, decay factors, and related structures for both THDC and TSHDC models, experiments were conducted to compare model convergence speed, accuracy, and generalization performance. In order to better reflect the performance of the model, the loss function will be calculated separately for the three objects [25]. Here, 3d_train represents MPJPE on the partitioned training set without updating parameters, 3d_train(eval) represents MPJPE on the non-partitioned training set after updating the parameters, and 3d_valid(eval) represents MPJPE calculated on the test set (S9, S11) after updating the parameters.

Figure 7a shows the training curve of the THDC model trained for 60 epochs (data from the first three epochs are not plotted), and Figure 7b shows the training curve of the TSHDC model under the same conditions.

Figure 7.

Training curves of THDC (a) and TSHDC models (b).

As can be seen from Figure 7, for the THDC model on the training set, after 20 epochs of training, its convergence speed begins to decrease significantly. After 30 epochs, the training speed tends to flatten. At 40 epochs, the MPJPE reaches an accuracy of 21.5 mm. On the test set, the MPJPE metric of THDC gradually flattens after 20 epochs. After 40 epochs, the accuracy changes at a rate of less than 0.01 mm, reaching the convergence limit of 56.2 mm after 60 epochs. For the TSHDC model, after 10 epochs of training, its accuracy on the test set has already converged to around 52–53 mm. After 60 epochs, its convergence accuracy reaches 49.4 mm. In comparison, the TSHDC model with the added MSA layer shows significant improvements in both convergence speed and final accuracy compared to the THDC model.

Here, we briefly describe the ablation experiment comparing the proposed hybrid dilation strategy with standard dilated convolution, aiming to validate the superiority of the sawtooth-like dilation pattern (dilation rates [1, 3, 9]) in hybrid dilated convolution (HDC) over the standard fixed dilation pattern [2, 2, 2]. The results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Ablation comparison between standard and hybrid dilated convolution.

As can be seen from the table, the hybrid dilation strategy eliminates the gridding artifact common in standard dilated convolution through its sawtooth-like dilation pattern. It enlarges the temporal receptive field from 21 frames to 27 frames while better preserving the spatiotemporal correlations of the keypoints. Experiments show that this strategy improves accuracy by 4.3 mm and increases inference speed by 27.9%, demonstrating the effectiveness of the sawtooth dilation pattern in enhancing the integrity of feature extraction.

4.4.3. Ablation Study and Analysis on Receptive Field Frames

Keeping all other structures of the TSHDC model unchanged, we only vary the number of input frames (i.e., the size of the temporal receptive field) and evaluate the MPJPE accuracy, inference latency, and GPU memory consumption (MB) on the Human3.6M test set to determine the optimal frame number configuration. The tested frame numbers are 9, 27, 81, and 243 (all odd numbers). The experimental results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Ablation study on receptive field frame numbers.

The results show that when increasing the frame number from 9 to 27, accuracy improves significantly by 5.8 mm, while inference latency increases by only 2.1 ms. When further increasing from 27 to 81 frames, accuracy improves by merely 0.8 mm, yet latency rises sharply by 12.5 ms. When the frame number reaches 243, the accuracy gain is less than 0.3 mm, whereas latency increases by 37.5 ms, making it unable to meet real-time application requirements. Therefore, this paper selects **27 frames** as the optimal trade-off configuration between accuracy and real-time performance.

5. Conclusions

This paper conducts research from both the algorithmic and hardware perspectives. First, a spatiotemporal hybrid dilated convolution model (TSHDC) based on the multi-head self-attention mechanism is designed, employing the temporal convolution network (TCN) for 3D human pose estimation tasks. This algorithm achieves a faster convergence speed while only slightly improving the MPJPE metric compared to state-of-the-art algorithms. Additionally, the model demonstrates better generalization capabilities when the dataset is limited. Meanwhile, ablation experiments of the multi-head self-attention layer (MSA) and the TSHDC model were designed, proving that the introduction of the MSA layer significantly accelerates model convergence. Subsequently, this paper investigates the implementation of the TSHDC model and real-time 3D HPE on the Jetson TX2 embedded development board. By compiling and installing the relevant packages on the TX2, the deployment of the TSHDC model was successfully achieved, and the inference process of the TSHDC model was significantly accelerated using the TensorRT framework. In addition, multiple real-time 3D HPE task schemes were designed. Among them, the scheme based on the TSHDC model comprehensively utilizes several different models to accomplish real-time 3D HPE tasks, which holds certain research value. Although this study has achieved the above results, there are still certain limitations. For example, the new organizational structure design and the reconstruction of loss functions have not yet reached optimal outcomes. Future research will focus on addressing these limitations through in-depth optimization. On the one hand, we will explore more efficient network architectures to enhance the model’s performance ceiling; on the other hand, we will develop loss functions better suited to the characteristics of 3D human pose estimation tasks, further improving the research framework and expanding its application value.

Author Contributions

Methodology, L.Z.; Software, S.D.; Resources, L.S.; Writing—original draft, S.D.; Writing—review & editing, L.S.; Visualization, S.D.; Project administration, S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, Y.; Wen, G.; Mi, S.; Zhang, M.; Geng, X. A review of two-dimensional human pose estimation based on deep learning. J. Softw. 2022, 33, 4173–4191. [Google Scholar]

- Toshev, A.; Szegedy, C. DeepPose: Human pose estimation via deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 1653–1660. [Google Scholar]

- Pavllo, D.; Feichtenhofer, C.; Grangier, D.; Auli, M. 3D human pose estimation in video with temporal convolutions and semi-supervised training. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 7745–7754. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Y.; Li, Q.; Li, Q.; Huang, H. 3D Human Pose Estimation with a Spatio-Temporal Cross Attention-GCN Network. In Proceedings of the 2025 5th International Conference on Neural Networks, Information and Communication Engineering (NNICE), Guangzhou, China, 10–12 January 2025; pp. 717–720. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Liu, H.; Tang, H.; Wang, P.; Van Gool, L. MHFormer: Multi-Hypothesis Transformer for 3D Human Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 13137–13146. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, L.; Huang, X.; Ma, L. 3D Human Pose Estimation in Spatio-Temporal Based on Graph Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 4th International Conference on Information Technology, Big Data and Artificial Intelligence (ICIBA), Chongqing, China, 6–8 December 2024; pp. 1252–1256. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Z.; Yang, S.; Yang, W.; Xia, S.T.; Zhou, E. TokenPose: Learning Keypoint Tokens for Human Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 11293–11302. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Guo, Y.; Ye, L.; Yuan, P.; Peng, D.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Liu, Q. 3D-UGCN: A Unified Graph Convolutional Network for Robust 3D Human Pose Estimation from Monocular RGB Images. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th Asian Conference on Artificial Intelligence Technology (ACAIT), Fuzhou, China, 8–10 November 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Hu, J. 3D Human Pose Estimation with Two-Step MixedGraph Convolution Transformer Encoder. In Proceedings of the 2025 5th International Conference on Neural Networks, Information and Communication Engineering (NNICE), Guangzhou, China, 10–12 January 2025; pp. 1479–1484. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, C.; Qu, B.; Miao, R.; Wang, X. Cost-Efficient Fall Risk Assessment With Attention Augmented Vision Machine Learning on Sit-to-Stand Test Videos. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 145373–145386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, F.; Jiang, P. On Boosting Single-Frame 3D Human Pose Estimation via Monocular Videos. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 2192–2201. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.; Wu, C.; Zhang, X. Improving 3D Human Pose Estimation with Enhanced Body Feature Representation. In Proceedings of the 2025 8th International Conference on Advanced Algorithms and Control Engineering (ICAACE), Shanghai, China, 21–23 March 2025; pp. 2255–2258. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y.; Ge, L.; Liu, J.; Cai, J.; Cham, T.J.; Yuan, J.; Thalmann, N.M. Exploiting Spatial-Temporal Relationships for 3D Pose Estimation via Graph Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 2272–2281. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Huang, S.; Wang, X.; Tao, D. Not All Parts Are Created Equal: 3D Pose Estimation by Modelling Bi-directional Dependencies of Body Parts. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 7770–7779. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.; Kang, J. Double Discrete Representation for 3D Human Pose Estimation from Head-mounted Camera. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics (ICCE), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 6–8 January 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Akhtar, N.; Mian, A. Adversarial Attack on Skeleton-based Human Action Recognition. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 33, 1609–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.; Kolotouros, N.; Pavlakos, G.; Zhou, X.; Daniilidis, K. Coherent Reconstruction of Multiple Humans from a Single Image. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 5578–5587. [Google Scholar]

- Jena, S.; Multon, F.; Boukhayma, A. Monocular Human Shape and Pose with Dense Mesh-borne Local Image Features. In Proceedings of the 2021 16th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition (FG 2021), Jodhpur, India, 15–18 December 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W. Adversarial Learning Enhancement for 3D Human Pose and Shape Estimation. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2022—2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Singapore, 22–27 May 2022; pp. 3743–3747. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Li, F.; Chen, X.; Yang, L. Pressure-Based In-Bed Pose Estimation Methods Using the Skinned Multi-person Linear Model. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th Asia Conference on Information Engineering (ACIE), Singapore, 26–28 January 2024; pp. 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Tian, L.; Du, Q. Multi-Resolution Convolution for 3D Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Intelligent Robotics and Automatic Control (IRAC), Guangzhou, China, 29 November–1 December 2024; pp. 274–278. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H.; Li, Z.; Zhang, D.; He, S.; Tang, J. Divide-and-Conquer: Confluent Triple-Flow Network for RGB-T Salient Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2025, 47, 1958–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaleghi, L.; Sepas-Moghaddam, A.; Marshall, J.; Etemad, A. Multiview Video-Based 3-D Hand Pose Estimation. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2023, 4, 896–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, H. Image recognition based on deep residual shrinkage Network. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Electromechanical Automation (AIEA), Guangzhou, China, 14–16 May 2021; pp. 334–337. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar, M.; Tanveer, M.; Arshad, M. RoBoSS: A Robust, Bounded, Sparse, and Smooth Loss Function for Supervised Learning. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2025, 47, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).