Abstract

Blockchain oracles, as data intermediaries between on-chain and off-chain environments, have opened up a wide range of application scenarios for blockchain technology. The dependability of a blockchain oracle system will affect the dependability of blockchain systems. However, the dynamic and heterogeneous nature of blockchain oracle systems poses challenges to assessing their dependability. Furthermore, how to comprehensively analyze the dependability of blockchain oracle systems from multiple dimensions of transient availability, steady-state availability, and reliability is also a challenge. In order to solve these challenges, this paper proposes three models based on a semi-Markov process (SMP): (1) the SMP model for steady-state availability analysis; (2) the hierarchical model for transient analysis; and (3) the SMP model with absorption states for reliability analysis. Then, we derive the formulas for calculating the dependability metrics, which can be used to evaluate the dependability of blockchain oracle systems composed of any number of oracle nodes. Finally, based on the comparative experiments to verify the approximate accuracy of the proposed model and formulas, we analyze the impact of system parameters and the number of oracle nodes on the dependability metrics. The experimental results reveal that the key factor affecting availability is the failure time and recovery time of the threshold oracle, while the key factor affecting MTTF is the failure time of the threshold oracle.

1. Introduction

Blockchain, as a decentralized and immutable digital ledger, is increasingly being used by researchers as an underlying platform [1]. It stores transaction data across a vast network of nodes, disrupting existing business models and infrastructure in many industries to eliminate the problems associated with centralization [2]. Furthermore, blockchain has wide applications in finance [3], the Internet of Vehicles [4], healthcare [5], and the Industrial Internet of Things [6] through smart contracts. Smart contracts require data from outside the blockchain system [7,8,9]. However, the closed nature of blockchain networks prevents them from directly sensing real-world data, thus limiting their potential and scope in practical applications. To address this limitation, third-party data providers—blockchain oracles—have emerged [10,11,12]. As data intermediaries between on-chain and off-chain environments, oracles are responsible for retrieving and verifying data from the real world and submitting it to the blockchain. This crucial role unlocks broader application scenarios for blockchain technology.

Based on network administration, oracles can be divided into centralized oracles and decentralized oracles. Centralized oracles are managed by a single entity and are responsible for providing the necessary data to smart contracts. Since the validity of the contract depends entirely on the entity controlling the centralized oracle, it is subject to a single point of failure. Decentralized oracles consist of multiple oracle servers, where the oracle nodes generate partial signatures, and these signatures are aggregated into a complete legal signature in the threshold oracle. When oracles introduce external data into the blockchain, a distributed oracle system can obtain data from multiple data sources, effectively solving the problem of data source reliability [13]. However, as off-chain components, the dependability guarantees of the blockchain system do not apply to oracle systems. Moreover, most research focuses on the selection of oracle nodes, while few studies address the dependability issues of blockchain oracle systems. Therefore, it is necessary to quantitatively evaluate the dependability of oracles to provide a reference for improving the dependability of blockchain systems. The evaluation results can also provide a theoretical basis for the selection of oracle nodes.

- Oracle systems are dynamic. Oracle nodes may become unavailable due to being offline, DDoS attacks, and unexpected failures, causing the number of oracle nodes in the oracle system to change dynamically. Furthermore, the available oracle node threshold for ensuring system reliability varies as the total number of nodes changes. Therefore, analyzing the dynamic behavior of oracle systems is a challenge that needs to be addressed.

- Transient availability, steady-state availability, and reliability metrics focus on different aspects of oracle system dependability. Therefore, how to collaboratively analyze these metrics to comprehensively analyze the dependability of the oracle system is a challenge that needs to be addressed.

- Oracle systems consist of threshold oracles and oracle nodes. Different nodes perform different functions, resulting in node heterogeneity. That is, different nodes are in different states at the same time. Therefore, capturing the heterogeneity of nodes in an oracle system is a challenge that needs to be addressed.

In order to address the above challenges, this paper proposes a semi-Markov process (SMP)-based oracle system dependability evaluation approach that can characterize the behaviors of the oracle system from initial operation to failure and perform recovery operations. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to comprehensively analyze the dependability of an oracle system consisting of an arbitrary number of oracle nodes from three perspectives: steady-state availability, transient availability, and reliability. The blockchain oracle system’s dependability refers to its ability to provide trustworthy services. Reliability refers to the ability of a blockchain oracle system to operate continuously without failure, while availability refers to its ability to provide effective services. Steady-state analysis is used to assess the blockchain oracle system’s dependability after long-term operation. Transient analysis is used to assess the instantaneous dependability of a blockchain oracle system when encountering sudden situations during operation. The innovations of this paper are as follows:

- We propose three models for analyzing the dependability of oracle systems. Specifically, (1) an SMP model captures the failure and recovery behaviors of each oracle node in the oracle system. (2) An SMP model with absorbing states captures the oracle system’s behaviors from initial operation to failure, and (3) a hierarchical model consisting of multiple SMP models captures the behaviors of the oracle system at different points in time. In particular, these models are multidimensional, which allows them to capture the behavior of different nodes in the system.

- We derive formulas for calculating transient availability, steady-state availability, and reliability, providing a comprehensive assessment of the oracle system’s dependability. The steady-state availability formula reveals the relationship between oracle node failure and recovery parameters, which can be used to evaluate the system’s behaviors as it approaches a steady state. The transient availability formula reveals the relationship between oracle node failure, recovery parameters, and time, which can be used to evaluate the dynamic behavior of the oracle system. The reliability formula reveals the sojourn time of the oracle system in each available state, which can be used to evaluate the executable time of the oracle system. In particular, these formulas are closed-form formulas, which can help service providers identify key factors affecting the dependability of the oracle system.

- We compare simulation and numerical analysis experiments to verify the approximate accuracy of the proposed formulas and models. We also perform sensitivity analysis experiments to analyze the sensitivity of various evaluation metrics with respect to different parameters. In addition, we evaluate the impact of different oracle node numbers on the oracle system’s dependability.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 discusses the differences between our work and existing work. Section 3 describes the system’s behavior, the constructs, and three models and derives the calculation formulas for various metrics. Section 4 presents the results of the simulation and numerical analysis experiments. Section 5 summarizes this paper and proposes future work.

2. Related Work

This section discusses the existing work from two aspects: dependability assessment approaches and blockchain oracle dependability analysis.

2.1. Dependability Assessment Approaches

Recently, a model-driven approach has been widely used in the field of dependability assessment of various complex technical systems and devices.

Tola et al. [14] proposed multiple stochastic activity network (SAN)-based models to analyze the availability of various management and orchestration deployment configurations. Ghosh et al. [15] constructed a stochastic Petri net (SPN)-based resiliency model to evaluate cloud storage service resiliency, which can capture the impact of possible disruptions. Torquato et al. [16] evaluated the availability and security of a system that uses VM migration as rejuvenation and moving target defense-based SPNs and compared these metrics under different migration intervals. They [17] modeled the host-based attack behaviors and VM migration-based defense behaviors based on SPNs and evaluated the attack success probability and system availability. These studies [14,15,16,17] can only investigate the dependability of a system with a fixed number of nodes and are not applicable to analyzing the dependability of systems with a variable number of oracles.

Pereira et al. [18] proposed a hierarchical model for analyzing the availability of the edge–fog–cloud continuum based on fault trees and continuous-time Markov chains (CTMCs) and identified the key elements affecting availability improvement by sensitivity analysis. Araujo et al. [19] combined reliability block diagrams (RBDs) and CTMCs to evaluate the availability of the mobile cloud environment while considering redundancy mechanisms. Simone et al. [20] analyzed the aging and rejuvenation behaviors of softwarized multi-tenant 5G architectures and developed an availability model based on CTMCs and the multidimensional universal generating function (MUGF). They [21] proposed a hierarchical model to assess the availability of Open5GS, which can capture the relationships between nodes based on RBDs and model the failure and repair behaviors of each node based on the stochastic reward network (SRN). These studies [18,19,20,21] employed hierarchical models to address the challenges of analyzing the dependability of large-scale systems. However, the studies [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21] based on the exponential distribution assumption still have limitations in practical applications; namely, they cannot capture the failure behaviors with increasing failure rates over time.

Ivanchenko et al. [22] compared the CTMC model against the SMP model, which were used to evaluate the availability of cloud server systems, while considering failures of their components. Zheng et al. [23] proposed SPN and non-Markov models to analyze the impact of software aging and human-error-related system failures on the system’s availability and determine the optimal software rejuvenation trigger timing. The authors in [24] conducted a sensitivity analysis for the loss probability of transactions based on the Markov regenerative process. Bhardwaj et al. [25] constructed an SMP-based dependability evaluation model for a virtualized computing system that may be subject to software aging, with two hosts used for operation and backup, respectively. These studies [22,23,24,25] relaxed the assumption of exponential time intervals between event occurrences, but they failed to provide a comprehensive analysis of system dependability in terms of transient availability, steady-state availability, and reliability. In addition, blockchain oracle systems consist of multiple oracle nodes, each with distinct behaviors that may change over time. These models have limitations in capturing the dynamic and heterogeneous behaviors of blockchain oracle systems.

2.2. Blockchain Oracle Dependability Analysis

There are few studies on the dependability evaluation of blockchain oracles, and more researchers should pay attention to the selection of blockchain oracles.

Lo et al. [26] constructed fault tree diagrams to evaluate oracle reliability and identified the key factors affecting the improvement of oracle reliability. Zhu et al. [27] analyzed the dependability of a heterogeneously distributed oracle system based on the CTMC model. They assumed that the time intervals between all events follow the exponential distribution and ignored the transient dependability analysis. In contrast, we propose an SMP model to analyze the dependability of a system composed of an arbitrary number of oracles from three aspects, transient availability, steady-state availability, and reliability, under the condition that the recovery time intervals follow the general distribution.

Liu et al. [28] achieved joint optimization of security and service quality for oracle selection by using a verifiable random function and a reputation mechanism. Taghavi et al. [29] designed a reinforcement learning model for selecting the most reliable and economical oracles. Zhang et al. [30] proposed an oracle selection approach that can optimize the cost and ensure trust based on deep reinforcement learning. Ahmadjee et al. [31] used a multi-criteria decision-making approach to select secure and cost-effective oracles. The dependability assessment of the oracle system proposed in this paper can be complemented with these studies to help select optimal oracles.

3. System Description and Dependability Analysis

This section first describes the oracle system’s behaviors. Then, we construct an SMP model for capturing the failure and recovery behaviors of oracle nodes. Based on the proposed model, we derive the formulas to calculate the transient availability, steady-state availability, and reliability of the oracle system, which can be used for dependability analysis.

3.1. System Dependability

The oracle system consists of a threshold oracle and N oracle nodes. The oracle node obtains data from various data sources and generates a partial signature. M oracle nodes each generate partial signatures for the same aggregation result, and these signatures are aggregated into a complete legal signature in the threshold oracle (M < N). Each node operates independently and does not affect the others.

After a period of operation, both oracle nodes and the threshold oracle can be unavailable due to various reasons such as being offline, DDoS attacks, and unexpected failures. The threshold oracle’s unavailability causes the entire system to fail because partial signatures from various oracle nodes cannot be aggregated, while the oracle node’s unavailability does not cause the entire system to fail. Because each node operates independently, the failure of one node will not affect the other nodes. If the oracle node is unavailable, this node will be rebooted after the fix is complete. If the threshold oracle is unavailable or more than oracle nodes are unavailable, all nodes in the oracle system will be rebooted after the failed node is fixed. We assume that the recovery time intervals follow the general distribution and that the failure time intervals follow the exponential distribution [27].

3.2. System State

We define a -tuple index to denote the oracle system’s state. Here, and denote the states of the threshold oracle and the kth oracle node, respectively. There are two states, Healthy and Failed, as denoted by H and F, respectively. The meaning of each state is as follows:

- State H (Healthy): In this state, the oracle node can function normally. A failed oracle node can return to this state after performing the recovery operation.

- State F (Failed): In this state, the oracle node is unavailable due to various reasons such as being offline, DDoS attacks, and unexpected failures.

Based on the descriptions above, the total number of system states is (n is odd) or (n is even), and the meaningful system states are shown in Table 1. We use to illustrate the meaningless system state. This state denotes that the threshold oracle is unavailable and that the remaining oracle nodes are available. In fact, when the threshold oracle is unavailable, the function of aggregating partial signatures cannot be completed. Even if other oracle nodes are available, the oracle system cannot be used to retrieve and verify data. Therefore, these meaningless system states can be ignored.

Table 1.

The meaningful system state’s definition.

3.3. Notation and Conventions

This section introduces the notations and conventions that were used in the models and matrixes. Table 2 shows the definition of variables used in the model and matrixes. It is important to note that represents the system state and is used as a subscript for elements in a matrix. The subscript of an element in a matrix consists of two system states and is used to identify the transition from one state to another.

Table 2.

The definition of variables used in the model.

3.4. Steady-State Availability Analysis

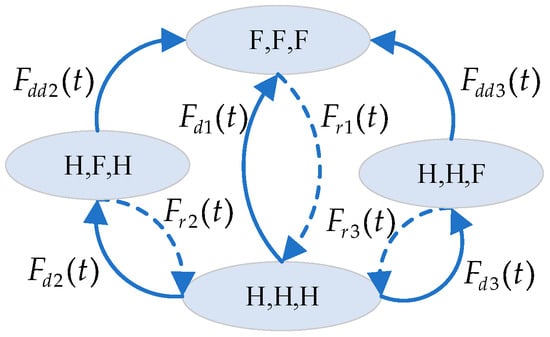

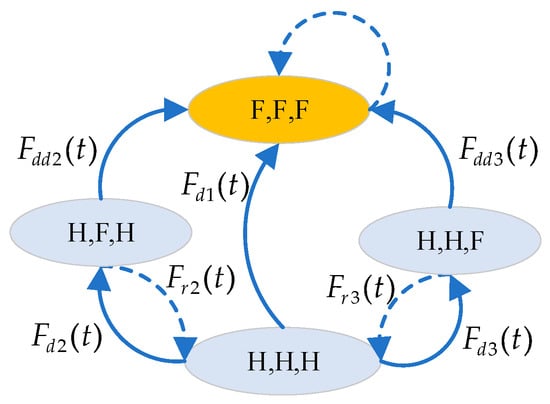

The SMP model can be used to capture the behaviors of the oracle system considered in this paper. Figure 1 shows the SMP model for the oracle system with one threshold oracle and two oracle nodes, as shown in Figure 1. Table 2 shows the definitions of the variables used in the model. The steady-state availability of the oracle system can be calculated by summing the steady-state probabilities of all available system states, as shown in Equation (1).

Figure 1.

The SMP model for analyzing the steady-state availability of the oracle system consisting of one threshold oracle and two oracle nodes.

In Equation (1), is the steady-state probability of the system state in the embedded discrete time Markov chain (EDTMC), which is calculated by and subject to . The one-step transition probability matrix P can describe the EDTMC, as shown in Equation (2). denotes the probability that the EDTMC will then transition to state if it is already in system state .

where the non-null elements are given in Equations (3)–(10).

In Equation (1), is the mean sojourn time for each state, which is calculated by . is the sojourn time distribution for each state. Equations (11)–(14) provide the detailed process for calculating .

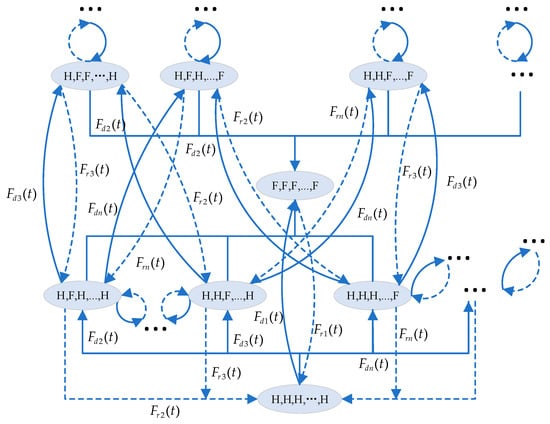

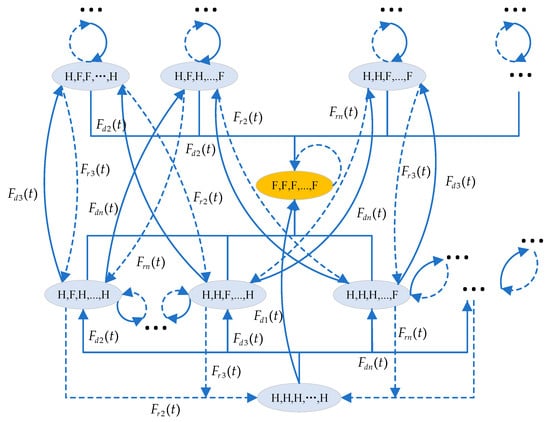

Based on a three-dimensional model, we propose the SMP model for the oracle system with one threshold oracle and N oracle nodes, as shown in Figure 2. Table 2 shows the definitions of the variables used in the model. The steady-state availability of the oracle system can be calculated by summing the steady-state probabilities of all available system states, as shown in Equation (15).

Figure 2.

The SMP model for analyzing the steady-state availability of the oracle system consisting of any number of oracle nodes.

The one-step transition probability matrixes are shown in Equations (16) and (17), corresponding to the cases where n is odd and even, respectively.

where the non-null elements are given in Equations (18)–(39). ().

Equations (40)–(44) provide the detailed process for calculating , where .

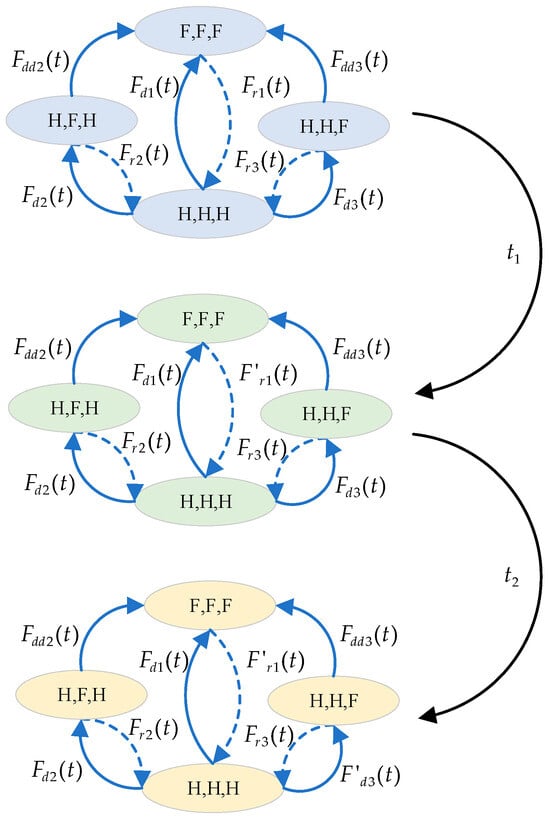

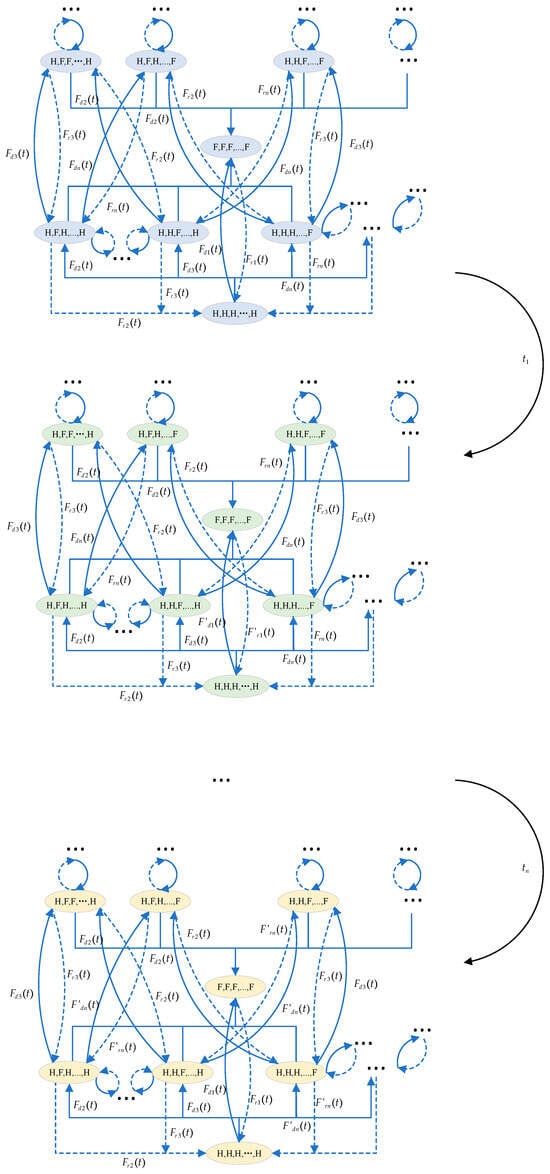

3.5. Transient Availability Analysis

The hierarchical model consisting of multiple SMP models can be used to capture the dynamic behaviors of the oracle system considered in this paper. Figure 3 shows the hierarchical model for the oracle system with three nodes. Furthermore, we extend this model to the multidimensional model to analyze the oracle system with one threshold oracle and N oracle nodes, as shown in Figure 4. The definitions of the variables used in the model are shown in Table 2. The transient availability of the oracle system can be calculated by summing the transient probabilities of all available system states at time t, as shown in Equation (45).

Figure 3.

The hierarchical model for analyzing the transient availability of the oracle system consisting of one threshold oracle and two oracle nodes.

Figure 4.

The hierarchical model for analyzing the transient availability of the oracle system consisting of any number of oracle nodes.

In order to obtain , we can solve , where is the initial probability vector, and can be solved by taking the inverse Laplace–Stieltjes transform (LST) . can be obtained by Equations (46) and (47), corresponding to the cases where n is odd and even, respectively. is a diagonal matrix and can be obtained by .

3.6. Reliability Analysis

In this paper, we use the mean time to oracle system failure for evaluating the oracle system’s reliability. In order to calculate the MTTF of the oracle system, we need to consider an oracle system without recovery operations. The SMP model with absorbing states can be used to capture the behaviors of the oracle system without recovery operations. Figure 5 shows the SMP model for the oracle system with three nodes. Furthermore, we extend this model to the multidimensional model to analyze the oracle system with any number of nodes, as shown in Figure 6. The system state’s definition is shown in Table 1. The definitions of the variables used in the model are shown in Table 2. The assumptions involved in the model are consistent with those described in Section 3.1 and Section 3.2. The MTTF of the oracle system can be calculated by Equation (48).

where is the expected number of visits to the system state until absorption and can be derived by or . is the initial probability of the system state. is the one-step transition probability matrix and can be obtained by Equations (49) and (50), corresponding to the cases where n is off and even, respectively. Compared to , lacks a description of the transition probability from the failure system state to the healthy system state .

Figure 5.

The SMP model for analyzing the reliability of the oracle system consisting of one threshold oracle and two oracle nodes.

Figure 6.

The SMP model for analyzing the reliability of the oracle system consisting of any number of oracle nodes.

4. Experiment Results

This section first describes the comparison results between the simulation and numerical analyses. Then, we gives the sensitivity of different metrics with respect to system parameters. Finally, we analyze how oracle dependability varies with the number of oracle nodes.

4.1. Experimental Configuration

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed models and formulas in the experiment, we set and as the CDFs of the threshold oracle failure time and the oracle node failure time, respectively. and are set as the CDFs of the threshold oracle recovery time and the oracle node recovery time, respectively. Table 2 gives the default parameter settings. Note that our models are also applicable to other types of CDFs and other parameter settings. We develop a simulator in the Maple language to verify the approximate accuracy of the proposed model and formulas. The simulation experiments were run 10,000 times. The results were averages of 10,000 simulation experiments. Based on the formulas derived in Section 3, we perform the numerical experiments. Simulation and numerical experiments are conducted on MAPLE. When performing the inverse LST in Maple, the first state uses table lookup. If it cannot be solved, it will proceed to the second state, which will perform factorization, transforming the original problem into a known problem. If it still cannot be solved, the third stage proceeds to solve it using algorithms such as Talbot. When calculating the solution, the digits are set to 100 to ensure that the error in the numerical results is very small and can be ignored.

4.2. Comparison of Simulation and Numerical Experiments

To verify the effectiveness of the model and formula, we develop a simulator. Table 3 shows the comparison of simulation and numerical results under different oracle node recovery times. We can observe from Table 3 that the simulation results are approximately close to the numerical results, which demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed model and formula. The error between simulation results and numerical results is caused by the randomness of the simulation experiments.

Table 3.

The comparison of simulation and numerical results.

4.3. Sensitivity Analysis

To analyze the impact of system parameters on dependability metrics, we conduct the sensitivity analysis experiment. The scaled sensitivities of availability and the MTTF can be calculated by . Table 4 shows the sensitivities of dependability metrics with respect to system parameters, where ‘--’ indicates that the MTTF is not affected by the corresponding parameter. Table 5 and Table 6 show the specific changes in dependability metrics under different failure times and recovery times, respectively. Availability can reflect the time that the blockchain oracle system is unavailable within a year, which is known as downtime. A decrease in availability of 0.00001 will increase downtime by approximately 5 min, and a decrease in availability of 0.0000001 will increase downtime by approximately 3 s. We can observe from Table 4 that availability and the MTTF are both negatively correlated with the parameters. That is, as failure time increases, the MTTF and availability increase, while as recovery time increases, the MTTF and availability decrease. We can also observe that the key factor affecting the MTTF is the failure time of the threshold oracle, and the key factor affecting availability is the failure time and recovery time of the threshold oracle.

Table 4.

The sensitivities of dependability metrics.

Table 5.

The dependability metrics under different failure times.

Table 6.

The dependability metrics under different recovery times.

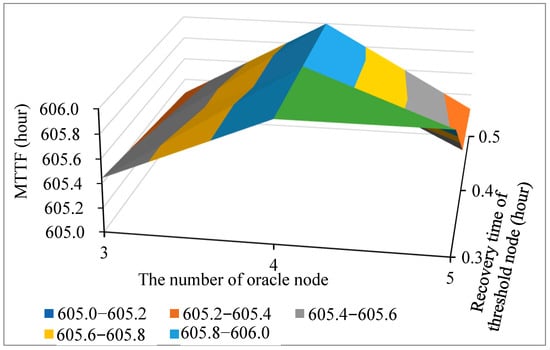

4.4. Impact of the Number of Oracle Nodes on Dependability Metrics

In this section, we conduct dependability assessment experiments under the oracle node numbers of three, four, and five, respectively. Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9 show the availability of the blockchain oracle system under different node numbers. Table 10 and Figure 7 show the MTTF of the blockchain oracle system under different node numbers. These experimental results are attributed to the different conditions under which the blockchain oracle system becomes available across different node numbers. We can observe that as the number of oracle nodes increases, availability increases slightly. This is because the increase in the number of oracle nodes leads to more available system states.

Table 7.

The availability of the blockchain oracle system under different node numbers and failure times.

Table 8.

The availability of the blockchain oracle system under different node numbers and threshold node recovery times.

Table 9.

The availability of the blockchain oracle system under different node numbers and oracle node recovery times.

Table 10.

The MTTF of the blockchain oracle system under different node numbers and failure times.

Figure 7.

The MTTF of the blockchain oracle system under different node numbers and recovery times of the threshold node.

5. Discussion

This paper takes a first step towards quantitatively assessing the dependability of a blockchain oracle system consisting of an arbitrary number of oracle nodes from the point of view of steady-state availability, transient availability, and reliability. However, our approach still has some limitations. Next, we will discuss how to extend our model to address these limitations.

- Our models employs SMP technology, providing a reference for capturing the behaviors of blockchain oracle systems composed of multiple oracle nodes. However, we assume that failure time follows an exponential distribution, which limits the wide applicability of our models. To address this limitation, our models can be extended to models built using the Markov regenerative process, in which non-regenerative states can capture failure behaviors.

- In our model, the state space is represented by multidimensional tuples, which helps capture the heterogeneous behavior of nodes in blockchain oracle systems. The derived formulas can be used to analyze dependability under different numbers of oracle nodes. However, as the variety of components in the system increases, model construction becomes more difficult. Therefore, our models can be extended to hierarchical models, where our models captures fine-grained node behaviors, while RBD captures the relationships between components, effectively enhancing the model’s scalability.

- Our models describe the failure and recovery behaviors of nodes in the blockchain oracle system. However, oracle node failures can be caused by factors such as attacks. Therefore, our models can be extended to describe fine-grained attack behaviors, such as reconnaissance, intrusion, lateral movement, and execution, and to capture recovery behaviors at different attack stages.

- Our dependability assessment model only considers the impact of node failures and recovery on the dependability of blockchain oracle systems. However, network latency and data source reliability also affect system dependability. In the future, we will deploy a real-world platform to capture the impact of network latency and data source reliability on failure time and recovery time, thereby incorporating more accurate parameters into the model for dependability analysis.

- Our research focuses on the theoretical analysis of the dependability of blockchain oracle systems. The gap between theoretical analysis and practical measurements has not yet been assessed. However, considering the difficulty of deploying a practical platform and the time required to conduct experiments, we leave this for future work. It is important to note that our research can complement practical measurement experiments by analyzing the reasons behind the measurement results.

6. Conclusions

This paper analyzes the dependability of the blockchain oracle system composed of an arbitrary number of oracle nodes by constructing SMP-based models. The proposed approach can be used to comprehensively analyze the dependability of the blockchain oracle system from three perspectives: steady-state availability, transient availability, and reliability. Experimental results demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed model and formulas. In the future, we will explore the development of more fine-grained models to characterize the behaviors of oracle nodes under attack and their defense behaviors, thereby analyzing the security of blockchain oracle systems.

Funding

This research was supported by Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, University of International Relations, 3262025T38.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CTMC | Continuous-time Markov chain |

| MUGF | Multidimensional universal generating function |

| RBD | Reliability block diagram |

| SAN | Stochastic activity network |

| SMP | Semi-Markov process |

| SPN | Stochastic Petri net |

| SRN | Stochastic reward network |

References

- Maesa, D.D.F.; Mori, P. Blockchain 3.0 applications survey. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2020, 138, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Apu, K.U. Decentralized vs. Centralized Database Solutions in Blockchain: Advantages, Challenges, and Use Cases. Glob. Mainstream J. Innov. Eng. Emerg. Technol. 2024, 3, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Tiwari, C.K.; Behl, A. Blockchain Technology in Financial Services: A Comprehensive Review of the Iiterature. J. Glob. Oper. Strateg. Sourc. 2021, 14, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, S.; Yu, H.; Badshah, A.; Waqas, M.; Halim, Z.; Ahmad, I. Secure Internet of Vehicles (IoV) with Decentralized Consensus Blockchain Mechanism. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 11227–11236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGhin, T.; Choo, K.K.R.; Liu, C.Z.; He, D. Blockchain in healthcare applications: Research challenges and opportunities. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2019, 135, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, R.; Zeng, S.; Wang, Z.; Shang, J.; Chen, W.; Huang, T.; Wang, S.; Yu, F.R.; Liu, Y. A Comprehensive Survey on Blockchain in Industrial Internet of Things: Motivations, Research Progresses, and Future Challenges. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2022, 24, 88–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.N.; Loukil, F.; Ghedira-Guegan, C.; Benkhelifa, E.; Bani-Hani, A. Blockchain Smart Contracts: Applications, Challenges, and Future Trends. Peer-to-Peer Netw. Appl. 2021, 14, 2901–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taherdoost, H. Smart Contracts in Blockchain Technology: A Critical Review. Information 2023, 14, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Parizi, R.M.; Zhang, Q.; Choo, K.K.R.; Dehghantanha, A. Blockchain Smart Contracts Formalization: Approaches and Challenges to Address Vulnerabilities. Comput. Secur. 2020, 88, 101654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzat, S.K.; Saleh, Y.N.; Abdel-Hamid, A.A. Abdel-Hamid: Blockchain Oracles: State-of-the-art and Research Directions. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 67551–67572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasdar, A.; Lee, Y.C.; Dong, Z. Connect API with Blockchain: A Survey on Blockchain Oracle Implementation. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldarelli, G. Understanding the Blockchain Oracle Problem: A Call for Action. Information 2020, 11, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, J.; Berryhill, R.; Veneris, A.; Poulos, Z.; Veira, N.; Kastania, A. Astraea: A Decentralized Blockchain Oracle. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Internet of Things (iThings) and IEEE Green Computing and Communications (GreenCom) and IEEE Cyber, Physical and Social Computing (CPSCom) and IEEE Smart Data (SmartData), Halifax, NS, Canada, 30 July–3 August 2018; pp. 1145–1152. [Google Scholar]

- Tola, B.; Jiang, Y.; Helvik, B.E. Model-Driven Availability Assessment of the NFV-MANO with Software Rejuvenation. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2021, 18, 2460–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Lakshmi, J. End-to-end Resiliency Analysis Framework for Cloud Storage Services. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 28th Pacific Rim International Symposium on Dependable Computing (PRDC), Singapore, 24–27 October 2023; pp. 134–141. [Google Scholar]

- Torquato, M.; Maciel, P.; Vieira, M. Software Rejuvenation Meets Moving Target Defense: Modeling of Time-Based Virtual Machine Migration Approach. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 33rd International Symposium on Software Reliability Engineering (ISSRE), Charlotte, NC, USA, 31 October–3 November 2022; pp. 205–216. [Google Scholar]

- Torquato, M.; Maciel, P.; Vieira, M. Evaluation of time-based virtual machine migration as moving target defense against host-based attacks. J. Syst. Softw. 2025, 219, 112222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.; Melo, C.; Araujo, J.; Dantas, J.; Santos, V.; Maciel, P. Availability model for edge-fog-cloud continuum: An evaluation of an end-to-end infrastructure of intelligent traffic management service. J. Supercomput. 2022, 78, 4421–4448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, J.; Oliveira, D.; Matos, R.; Alves, G.; Maciel, P. Availability and reliability modeling of mobile cloud architectures. In IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- De Simone, L.; Di Mauro, M.; Natella, R.; Postiglione, F. Performability Evaluation of Softwarized Multi-Tenant 5G Architectures with Rejuvenation. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Reliable Networks Design and Modeling (RNDM), Pompei (Napoli), Italy, 25–27 November 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- De Simone, L.; Di Mauro, M.; Natella, R.; Postiglione, F. Performance and Availability Challenges in Designing Resilient 5G Architectures. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2024, 21, 5291–5303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanchenko, O.; Kharchenko, V.; Moroz, B.; Ponochovnyi, Y.; Degtyareva, L. Availability Assessment of a Cloud Server System: Comparing Markov and Semi-Markov Models. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Workshop on Intelligent Data Acquisition and Advanced Computing Systems: Technology and Applications (IDAACS), Cracow, Poland, 22–25 September 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, J.; Okamura, H.; Dohi, T. Availability analysis of software systems with rejuvenation and checkpointing. Mathematics 2021, 9, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Okamura, H.; Dohi, T. Sensitivity Analysis of Software Rejuvenation Model with Markov Regenerative Process. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Software Reliability Engineering Workshops (ISSRE Wksp), Wuhan, China, 25–28 October 2021; pp. 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj, R.K.; Sharma, L. Analytical model of a virtualized computing system using semi-markov approach. Life Cycle Reliab. Saf. Eng. 2025, 14, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, S.K.; Xu, X.; Staples, M.; Yao, L. Reliability Analysis for Blockchain Oracles. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2020, 83, 106582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Bai, J.; Misic, J.; Misic, V.B.; Chang, X. On Dependability of Heterogeneous Distributed Oracle System in Blockchain. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC), Denver, CO, USA, 9–13 June 2024; pp. 782–787. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Xian, Y.; Yao, C.; Wang, P.; Wang, L.E.; Li, X. A Trustworthy and Consistent Blockchain Oracle Scheme for Industrial Internet of Things. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2024, 21, 5135–5148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghavi, M.; Bentahar, J.; Otrok, H.; Bakhtiyari, K. A Reinforcement Learning Model for the Reliability of Blockchain Oracles. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 214, 119160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, S.; Bao, H.; Wu, S.; Li, J. A Trust-Aware and Cost-Optimized Blockchain Oracle Selection Model with Deep Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.16133. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadjee, S.; Mera-Gómez, C.; Farshidi, S.; Bahsoon, R.; Kazman, R. Decision Support Model for Selecting the Optimal Blockchain Oracle Platform: An Evaluation of Key Factors. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2025, 34, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).