Balancing Specialization and Generalization Trade-Off for Speech Recognition Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Analysis of the specialization–generalization trade-off in ASR—We systematically study how finetuning affects a model’s ability to retain general ASR capabilities while adapting to new tasks, particularly in low-resource and domain-specific scenarios.

- Evaluation of model merging as a forgetting mitigation strategy—We find that model merging effectively balances adaptation and knowledge retention, especially when no prior task data is available, but struggles for tasks with low relatedness.

- Demonstration of experience replay as a simple yet powerful baseline—Our results show that even a small memory buffer significantly improves retention, often outperforming more complex regularization methods.

- Code release—We release our code to enable reproduction of our work and further investigation.

2. Related Work

3. Method

4. Experimental Setup

4.1. Experiments

- Adaptation to Polish (PL) language while preserving the pretrained model recognition capabilities in the English (EN) language.

- Similar to the above, but adaptation is performed to the Slovak (SK) language. Here, we are experimenting with a very low-resource language adaptation, with an order of magnitude smaller number of utterances than for the PL language.

- Adaptation to specialized medical jargon in the PL language while investigating forgetting in the PL language. This experiment allows us to study the generalization–specialization trade-off when there is a similarity between the two tasks.

4.2. Data

4.3. Models

- (1)

- Finetuning—naively adapts the model to the target. This is a highly plastic model that will perform well on new tasks but forget much of the previous knowledge.

- (2)

- Frozen—we additionally report the results of the frozen model which favors stability (knowledge preservation).

- (3)

- Learning without forgetting (LwF) [11]—it is a popular Continual Learning method, which was previously successfully applied also in ASR [43,44]. During finetuning it adds a distillation loss to minimize the KL divergence between outputs for the () and the model from the previous task ():We run a parameter search for the optimal value in Section 5.3.

- (4)

- EMAteacher. The LwF is a strong Continual Learning approach; however, it can limit learning of the new task [36]. Therefore, to improve its flexibility, we also experiment with a variant where we allow the teacher to slightly adapt towards the target task. Specifically, we present a EMAteacher strategy, which is a similar strategy to the LwF, but here the teacher is set to be an exponential moving average (EMA) of the current model:The EMA was first proposed by Tarvainen & Valpola [45] in the semi-supervised setting. The same strategy was later used in self-supervised learning [46,47] and more recently to online continual learning [48], which inspired us to use it in our setting. Following popular approaches in this area, we set [48,49].

- (5)

- Model Merging—we also experiment with merging approaches [12,50]. More specifically, in the first stage, a simple finetuning procedure is applied, and then the weights of the new model are computed as follows:where in our case, refers to the downstream task, and refers to the pretraining stage. Similar, as in other works [32], we set . We also experiment with Model Merging combined with LwF regularization, following [32].

- (6)

- Experience Replay (ER)—we additionally optionally equip all methods with a small budget of memory of previous task in Section 5.3, as commonly used in Continual Learning [29,31]. The specific type of data used for experience replay varies depending on the experiment and is detailed later in the paper.

4.4. Methodology

5. Results

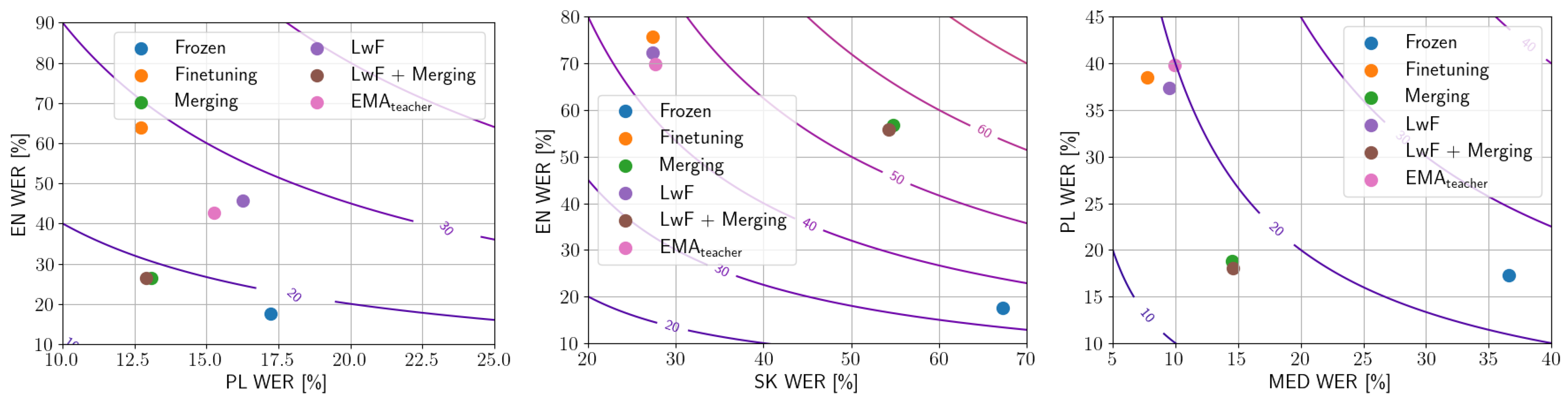

5.1. Forgetting in ASR Models

- The target and retention tasks are disjointed. We analyze finetuning in low-resource downstream tasks (PL and SK) and evaluate forgetting on retention tasks (EN).

- The target and retention tasks are similar. For this purpose, we finetune the model on a specialized dataset of Polish medical speech and evaluate forgetting in the PL language (retention task).

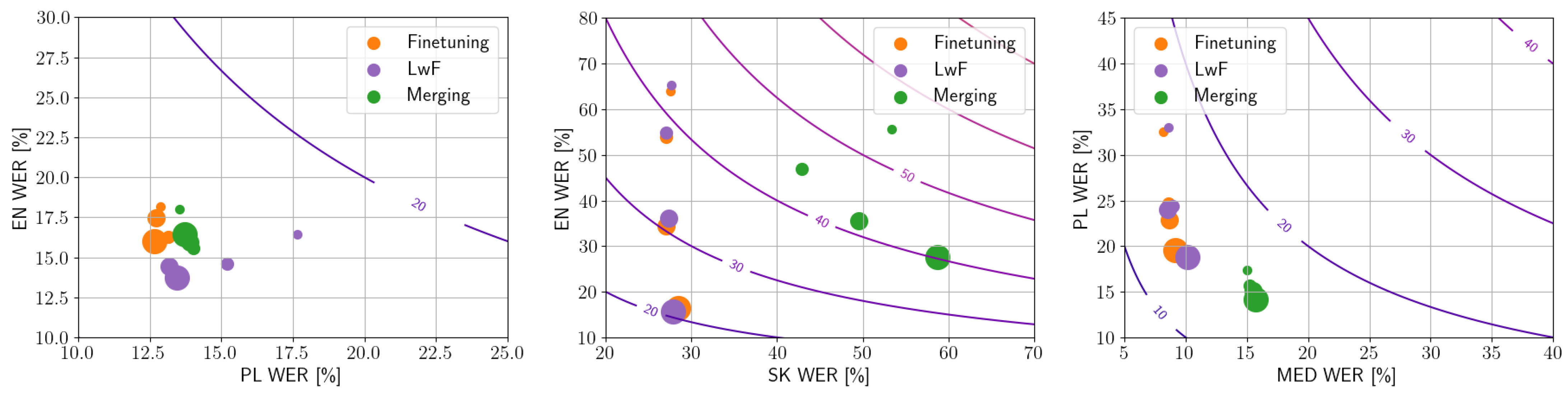

5.2. Impact of Experience Replay

- When finetuning PL and SK languages, we also used additional data for EN language.

- When finetuning on the Medical dataset, we also used PL data.

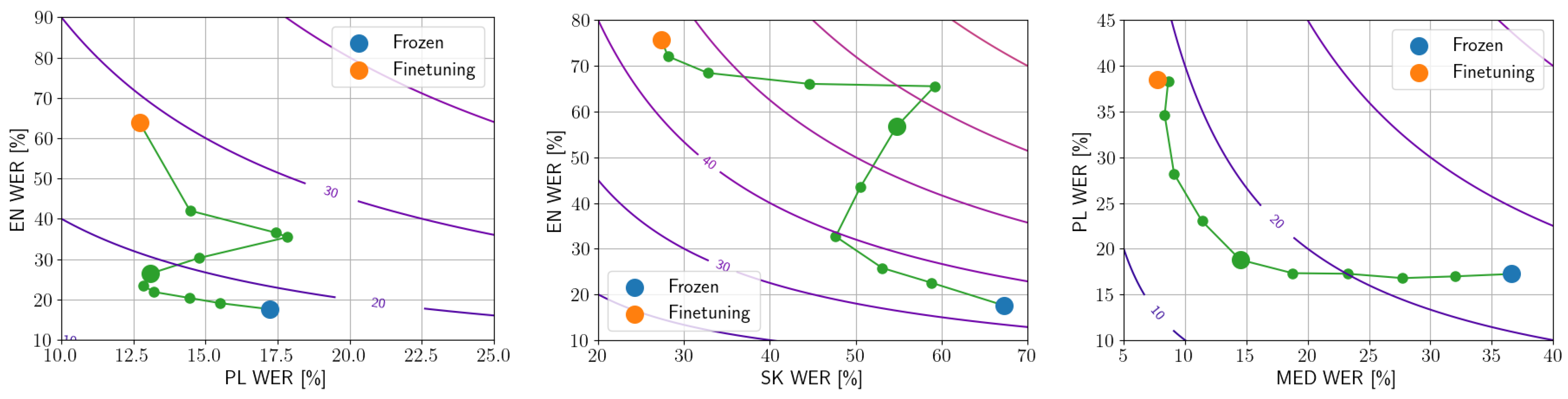

5.3. Detailed Analysis

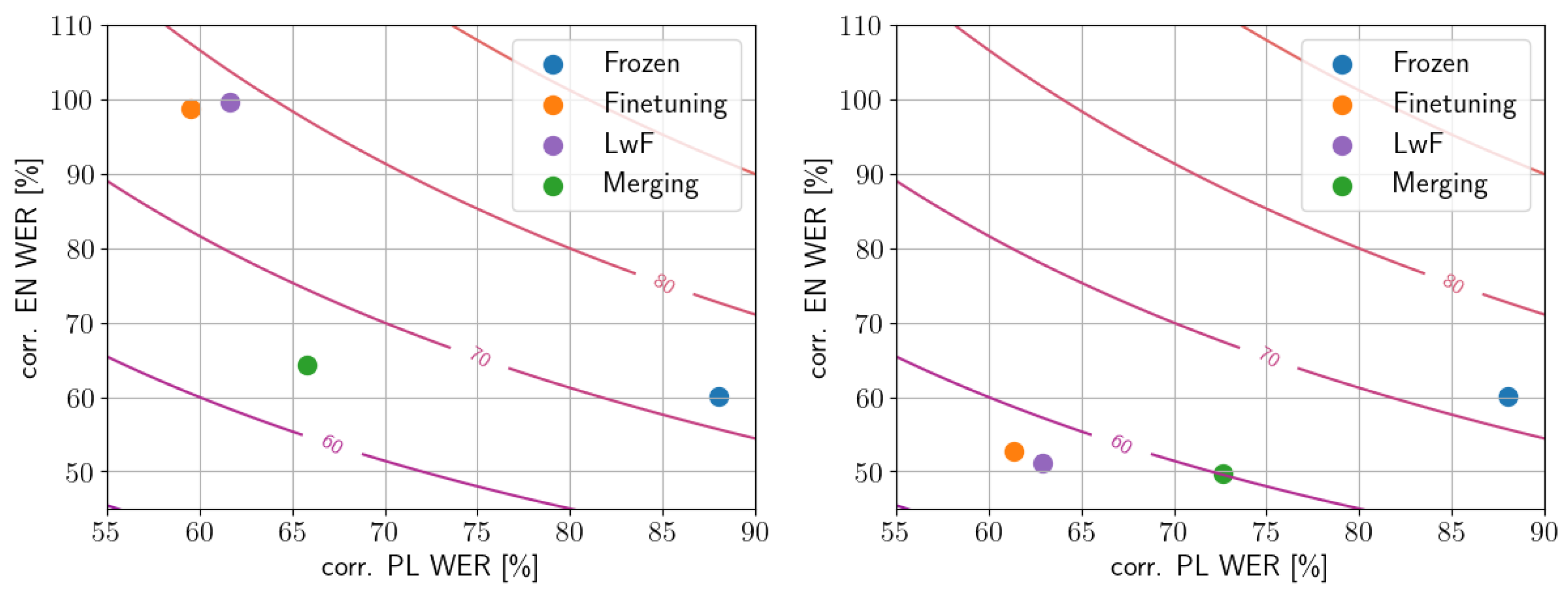

5.3.1. Corruption Robustness

5.3.2. Similarity Analysis

- Merging models, when there is a limited access to the data of the pretrained task,

- Experience Replay when sufficient buffer of data is available.

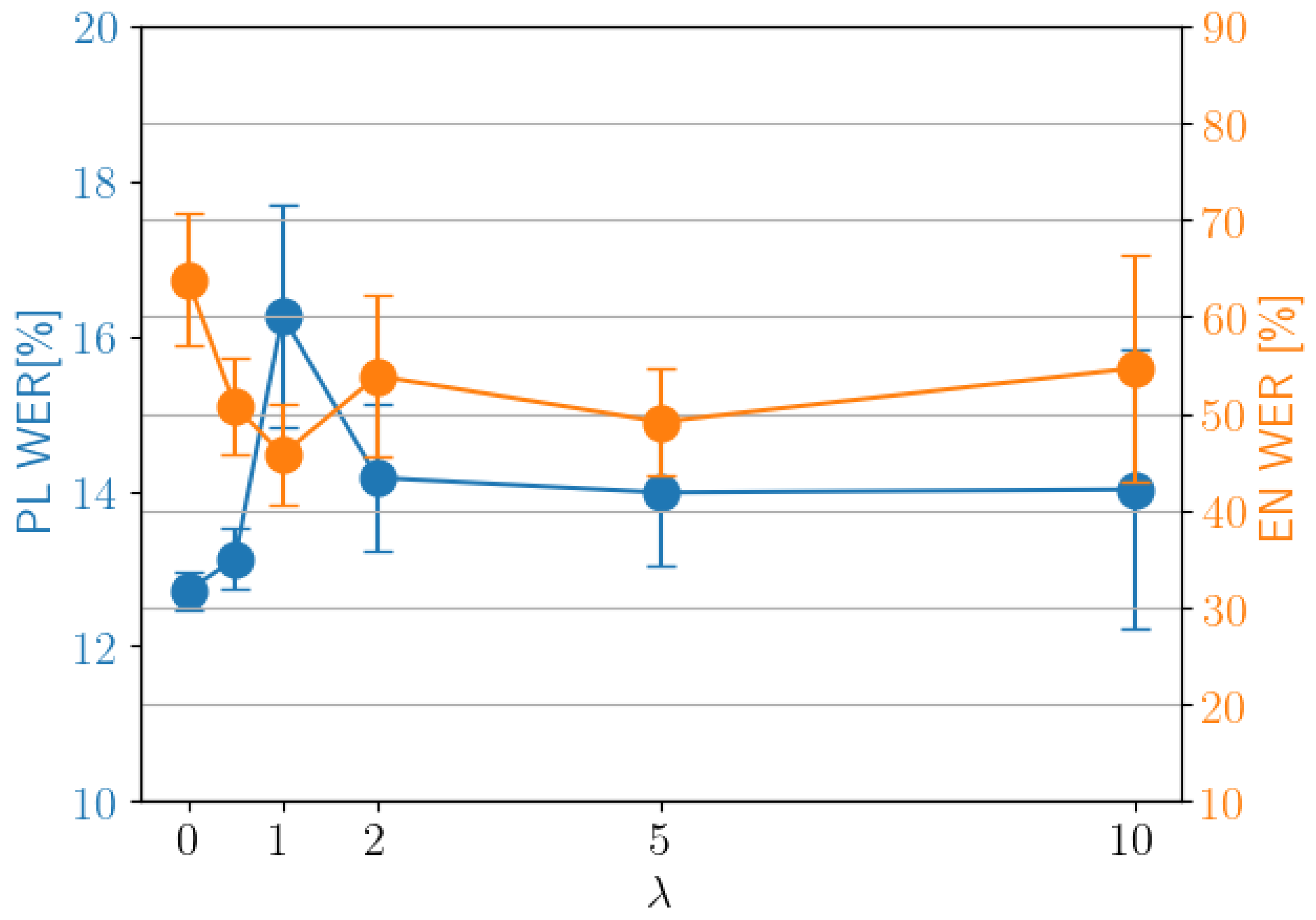

5.3.3. Hyperparameter Sensitivity

6. Discussion

- Model Merging consistently performs well across tasks, data quantity, and quality.

- When some memory buffer is available, simple finetuning achieves competitive results.

- Forgetting is a key issue, influenced by the pretrained model’s initial difficulty.

- Model Merging improves CKA alignment and reduces L2 distance; memory buffer slightly impacts these metrics but significantly boosts accuracy.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASR | Automatic Speech Recognition |

| CKA | Centered Kernel Alignment |

| CL | Continual Learning |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| WER | Word Error Rate |

References

- Brown, T.B.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems NeurIPS, Virtual, 6–12 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All you Need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Xu, T.; Brockman, G.; McLeavey, C.; Sutskever, I. Robust speech recognition via large-scale weak supervision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; pp. 28492–28518. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.; Ma, M.; Wang, K.; Qin, Z.; Yue, X.; You, Y. Preventing zero-shot transfer degradation in continual learning of vision-language models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 19125–19136. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Raghunathan, A.; Jones, R.M.; Ma, T.; Liang, P. Fine-Tuning can Distort Pretrained Features and Underperform Out-of-Distribution. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR, Virtual, 25 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; Volume 139, pp. 8748–8763. [Google Scholar]

- French, R.M. Catastrophic forgetting in connectionist networks. Trends Cogn. Sci. 1999, 3, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCloskey, M.; Cohen, N.J. Catastrophic interference in connectionist networks: The sequential learning problem. In Psychology of Learning and Motivation; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, J.; Pascanu, R.; Rabinowitz, N.; Veness, J.; Desjardins, G.; Rusu, A.A.; Milan, K.; Quan, J.; Ramalho, T.; Grabska-Barwinska, A.; et al. Overcoming catastrophic forgetting in neural networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 3521–3526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzega, P.; Boschini, M.; Porrello, A.; Abati, D.; Calderara, S. Dark experience for general continual learning: A strong, simple baseline. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 15920–15930. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Hoiem, D. Learning without forgetting. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 40, 2935–2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wortsman, M.; Ilharco, G.; Kim, J.W.; Li, M.; Kornblith, S.; Roelofs, R.; Lopes, R.G.; Hajishirzi, H.; Farhadi, A.; Namkoong, H.; et al. Robust fine-tuning of zero-shot models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 7959–7971. [Google Scholar]

- Baevski, A.; Zhou, Y.; Mohamed, A.; Auli, M. wav2vec 2.0: A framework for self-supervised learning of speech representations. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 12449–12460. [Google Scholar]

- Kheddar, H.; Hemis, M.; Himeur, Y. Automatic speech recognition using advanced deep learning approaches: A survey. Inf. Fusion 2024, 109, 102422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Cheng, G.; Li, T.; Zhang, P.; Yan, Y. Self-Supervised Pre-Training for Attention-Based Encoder-Decoder ASR Model. IEEE ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2022, 30, 1763–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Park, D.S.; Han, W.; Qin, J.; Gulati, A.; Shor, J.; Jansen, A.; Xu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, S.; et al. Bigssl: Exploring the frontier of large-scale semi-supervised learning for automatic speech recognition. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2022, 16, 1519–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Pang, R.; Sainath, T.N.; Gulati, A.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, J.; Haghani, P.; Huang, W.R.; Ma, M.; Bai, J. Scaling end-to-end models for large-scale multilingual ASR. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Automatic Speech Recognition and Understanding Workshop (ASRU), Cartagena, Colombia, 13–17 December 2021; pp. 1011–1018. [Google Scholar]

- Pratap, V.; Tjandra, A.; Shi, B.; Tomasello, P.; Babu, A.; Kundu, S.; Elkahky, A.; Ni, Z.; Vyas, A.; Fazel-Zarandi, M.; et al. Scaling Speech Technology to 1000+ Languages. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2024, 25, 4798–4849. [Google Scholar]

- Fatehi, K.; Torres Torres, M.; Kucukyilmaz, A. An overview of high-resource automatic speech recognition methods and their empirical evaluation in low-resource environments. Speech Commun. 2025, 167, 103151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, W. Improving Automatic Speech Recognition Performance for Low-Resource Languages With Self-Supervised Models. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2022, 16, 1227–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Berrebbi, D.; Chen, W.; Hu, E.; Huang, W.; Chung, H.; Chang, X.; Li, S.; Mohamed, A.; Lee, H.; et al. ML-SUPERB: Multilingual Speech Universal PERformance Benchmark. In Proceedings of the 24th Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association, Interspeech 2023, Dublin, Ireland, 20–24 August 2023; ISCA: Singapore, 2023; pp. 884–888. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, X.; Gao, X.; Qian, X.; Li, H. Adapting Pre-Trained Self-Supervised Learning Model for Speech Recognition with Light-Weight Adapters. Electronics 2024, 13, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naini, A.R.; Kohler, M.A.; Richerson, E.; Robinson, D.; Busso, C. Generalization of Self-Supervised Learning-Based Representations for Cross-Domain Speech Emotion Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, ICASSP, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 14–19 April 2024; pp. 12031–12035. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhoti, J.; Gal, Y.; Torr, P.; Dokania, P.K. Fine-Tuning Can Cripple Your Foundation Model; Preserving Features May Be the Solution. Trans. Mach. Learn. Res. 2024, 1–26. Available online: https://openreview.net/forum?id=kfhoeZCeW7 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Wortsman, M.; Ilharco, G.; Gadre, S.Y.; Roelofs, R.; Lopes, R.G.; Morcos, A.S.; Namkoong, H.; Farhadi, A.; Carmon, Y.; Kornblith, S.; et al. Model soups: Averaging weights of multiple fine-tuned models improves accuracy without increasing inference time. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning—ICML, Baltimore, MD, USA, 17–23 July 2022; Volume 162, pp. 23965–23998. [Google Scholar]

- Ilharco, G.; Ribeiro, M.T.; Wortsman, M.; Schmidt, L.; Hajishirzi, H.; Farhadi, A. Editing models with task arithmetic. In Proceedings of the ICLR, Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Duggal, R.; Singh, A.; Kundu, K.; Shuai, B.; Wu, J. Robustness Preserving Fine-Tuning Using Neuron Importance. 2024. Available online: https://assets.amazon.science/71/58/65a2cad64759bddb8fe34525ae03/robustness-preserving-fine-tuning-using-neuron-importance.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Yu, J.; Zhuge, Y.; Zhang, L.; Hu, P.; Wang, D.; Lu, H.; He, Y. Boosting Continual Learning of Vision-Language Models via Mixture-of-Experts Adapters. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 23219–23230. [Google Scholar]

- Pekarek Rosin, T.; Wermter, S. Replay to Remember: Continual Layer-Specific Fine-Tuning for German Speech Recognition. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks, Heraklion, Greece, 26–29 September 2023; pp. 489–500. [Google Scholar]

- van de Ven, G.M.; Tuytelaars, T.; Tolias, A.S. Three types of incremental learning. Nat. Mac. Intell. 2022, 4, 1185–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masana, M.; Liu, X.; Twardowski, B.; Menta, M.; Bagdanov, A.D.; Van De Weijer, J. Class-incremental learning: Survey and performance evaluation on image classification. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 45, 5513–5533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eeckt, S.V.; hamme, H.V. Weight Averaging: A Simple Yet Effective Method to Overcome Catastrophic Forgetting in Automatic Speech Recognition. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2023, Rhodes Island, Greece, 4–10 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Vander Eeckt, S.; Van Hamme, H. Using adapters to overcome catastrophic forgetting in end-to-end automatic speech recognition. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2023—2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Rhodes Island, Greece, 4–10 June 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Rolnick, D.; Ahuja, A.; Schwarz, J.; Lillicrap, T.P.; Wayne, G. Experience Replay for Continual Learning. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; pp. 348–358. [Google Scholar]

- Robins, A. Catastrophic forgetting, rehearsal and pseudorehearsal. Connect. Sci. 1995, 7, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rypesc, G.; Cygert, S.; Khan, V.; Trzcinski, T.; Zielinski, B.; Twardowski, B. Divide and not forget: Ensemble of selectively trained experts in Continual Learning. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2024, Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Goswami, D.; Liu, Y.; Twardowski, B.; van de Weijer, J. FeCAM: Exploiting the Heterogeneity of Class Distributions in Exemplar-Free Continual Learning. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Diwan, A.; Yeh, C.F.; Hsu, W.N.; Tomasello, P.; Choi, E.; Harwath, D.; Mohamed, A. Continual learning for on-device speech recognition using disentangled conformers. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2023—2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Rhodes Island, Greece, 4–10 June 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Bahdanau, D.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ardila, R.; Branson, M.; Davis, K.; Henretty, M.; Kohler, M.; Meyer, J.; Morais, R.; Saunders, L.; Tyers, F.M.; Weber, G. Common Voice: A Massively-Multilingual Speech Corpus. In Proceedings of the 12th Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2020), Marseille, France, 11–16 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Panayotov, V.; Chen, G.; Povey, D.; Khudanpur, S. Librispeech: An ASR corpus based on public domain audio books. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), South Brisbane, Australia, 19–24 April 2015; pp. 5206–5210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyżewski, A.; Cygert, S.; Marciniuk, K.; Szczodrak, M.; Harasimiuk, A.; Odya, P.; Galanina, M.; Szczuko, P.; Kostek, B.; Graff, B.; et al. A Comprehensive Polish Medical Speech Dataset for Enhancing Automatic Medical Dictation. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eeckt, S.V.; hamme, H.V. Continual Learning for Monolingual End-to-End Automatic Speech Recognition. In Proceedings of the 30th European Signal Processing Conference, EUSIPCO, Belgrade, Serbia, 29 August–2 September 2022; pp. 459–463. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.; Lee, H.; Lee, L. Towards Lifelong Learning of End-to-End ASR. In Proceedings of the 22nd Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association, Interspeech, Brno, Czech Republic, 30 August–3 September 2021; pp. 2551–2555. [Google Scholar]

- Tarvainen, A.; Valpola, H. Mean teachers are better role models: Weight-averaged consistency targets improve semi-supervised deep learning results. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 1195–1204. [Google Scholar]

- Grill, J.B.; Strub, F.; Altché, F.; Tallec, C.; Richemond, P.; Buchatskaya, E.; Doersch, C.; Avila Pires, B.; Guo, Z.; Gheshlaghi Azar, M.; et al. Bootstrap your own latent-a new approach to self-supervised learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 21271–21284. [Google Scholar]

- Caron, M.; Touvron, H.; Misra, I.; Jégou, H.; Mairal, J.; Bojanowski, P.; Joulin, A. Emerging properties in self-supervised vision transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 9650–9660. [Google Scholar]

- Soutif-Cormerais, A.; Carta, A.; van de Weijer, J. Improving Online Continual Learning Performance and Stability with Temporal Ensembles. In Proceedings of the Conference on Lifelong Learning Agents, Montréal, QC, Canada, 22–25 August 2023; Volume 232, pp. 828–845. [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Brotons, D.; Vogels, T.; Hendrikx, H. Exponential Moving Average of Weights in Deep Learning: Dynamics and Benefits. Trans. Mach. Learn. Res. 2024, 1–27. Available online: https://hal.science/hal-04830859v1 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Marczak, D.; Twardowski, B.; Trzcinski, T.; Cygert, S. MagMax: Leveraging Model Merging for Seamless Continual Learning. 2024. Available online: https://www.ecva.net/papers/eccv_2024/papers_ECCV/papers/11489.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Prabhu, A.; Torr, P.H.S.; Dokania, P.K. GDumb: A Simple Approach that Questions Our Progress in Continual Learning. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision-ECCV 2020—16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vedaldi, A., Bischof, H., Brox, T., Frahm, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 12347, pp. 524–540. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, M.A.; Noguero, D.S.; Heikkila, M.A.; Kourtellis, N. Speech Robust Bench: A Robustness Benchmark For Speech Recognition. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.07937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornblith, S.; Norouzi, M.; Lee, H.; Hinton, G.E. Similarity of Neural Network Representations Revisited. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2019, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; Proceedings of Machine Learning Research. Volume 97, pp. 3519–3529. [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi, S.; von Platen, P.; Rush, A.M. Distil-Whisper: Robust Knowledge Distillation via Large-Scale Pseudo Labelling. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.00430. [Google Scholar]

- Sanh, V.; Debut, L.; Chaumond, J.; Wolf, T. DistilBERT, a distilled version of BERT: Smaller, faster, cheaper and lighter. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.01108. [Google Scholar]

- Marczak, D.; Magistri, S.; Cygert, S.; Twardowski, B.; Bagdanov, A.D.; van de Weijer, J. No Task Left Behind: Isotropic Model Merging with Common and Task-Specific Subspaces. In Proceedings of the 42nd International Conference on Machine Learning, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 13–19 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gargiulo, A.A.; Crisostomi, D.; Bucarelli, M.S.; Scardapane, S.; Silvestri, F.; Rodolà, E. Task Singular Vectors: Reducing Task Interference in Model Merging. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR, Nashville, TN, USA, 10–17 June 2025; pp. 18695–18705. [Google Scholar]

| Speakers | Source | Train Split Size | Test Split Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PL | 2823 | CV and LS | 41.5 k | 8.8 k |

| SK | 137 | CV | 3.01 k | 2.24 k |

| EN | 55,574 | CV and LS | 216.0 k | 19.0 k |

| MED-PL | 181 | Private | 42.9 k | 4.8 k |

| Method | PL | SK | MED-PL | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PL | EN | L2-Dist | CKA | SK | EN | L2-Dist | CKA | MED-PL | PL | L2-Dist | CKA | |

| Finetuning | 11.25 | 0.77 | 4.38 | 0.82 | 17.83 | 0.64 | ||||||

| Merging | 5.63 | 0.84 | 2.19 | 0.85 | 8.91 | 0.81 | ||||||

| LwF | 11.55 | 0.77 | 4.38 | 0.80 | 17.55 | 0.59 | ||||||

| Finetuning + ER | 10.89 | 0.81 | 4.48 | 0.77 | 18.8 | 0.66 | ||||||

| Merging + ER | 5.45 | 0.86 | 2.24 | 0.83 | 8.91 | 0.80 | ||||||

| LwF + ER | 11.11 | 0.76 | 4.51 | 0.78 | 18.56 | 0.64 | ||||||

| Train time | 50% | 75% | 100% | 125% | 150% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Downstream Task WER (PL) | 13.4 | 12.8 | 13.3 | 13.3 | 18.1 |

| Pretrained Task WER (EN) | 26.1 | 25.4 | 26.4 | 29.9 | 38.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cygert, S.; Despot-Mładanowicz, P.; Czyżewski, A. Balancing Specialization and Generalization Trade-Off for Speech Recognition Models. Electronics 2025, 14, 4792. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244792

Cygert S, Despot-Mładanowicz P, Czyżewski A. Balancing Specialization and Generalization Trade-Off for Speech Recognition Models. Electronics. 2025; 14(24):4792. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244792

Chicago/Turabian StyleCygert, Sebastian, Piotr Despot-Mładanowicz, and Andrzej Czyżewski. 2025. "Balancing Specialization and Generalization Trade-Off for Speech Recognition Models" Electronics 14, no. 24: 4792. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244792

APA StyleCygert, S., Despot-Mładanowicz, P., & Czyżewski, A. (2025). Balancing Specialization and Generalization Trade-Off for Speech Recognition Models. Electronics, 14(24), 4792. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244792