Abstract

Homomorphic encryption enables computations to be performed directly on encrypted data, ensuring data confidentiality even in untrusted or distributed environments. Although this approach provides strong theoretical security, its practical adoption remains limited due to high computational and memory requirements. This study presents a comparative evaluation of three representative homomorphic encryption paradigms: partially, somewhat, and fully homomorphic encryption. The implementations are based on the GMP library, Microsoft SEAL, and OpenFHE. The analysis examines encryption and decryption time, ciphertext expansion, and memory usage under various parameter configurations, including different polynomial modulus degrees. The goal is to provide a transparent and reproducible comparison that illustrates the practical differences among these approaches. The results highlight the trade-offs between security, efficiency, and numerical precision, identifying cases where lightweight schemes can achieve acceptable performance for latency-sensitive or resource-constrained applications. These findings offer practical guidance for deploying homomorphic encryption in secure cloud-based computation and other privacy-preserving environments.

1. Introduction

The growing reliance on cloud computing, wireless communication, and large-scale data analytics has brought unprecedented opportunities for innovation, along with new challenges in ensuring data confidentiality and security. Modern distributed systems routinely process sensitive information such as personal records, medical measurements, or financial transactions across heterogeneous and often untrusted infrastructures. Although conventional encryption secures data during storage and transmission, it fails to protect privacy once decryption is required for computation. This fundamental limitation exposes data to potential misuse, particularly when processing is outsourced to third-party or shared cloud resources. Recent security incidents and data breaches highlight the pressing need for cryptographic methods that maintain privacy even during active computation.

Homomorphic encryption (HE) [1] provides a promising solution to this challenge. It enables mathematical operations to be performed directly on encrypted data, ensuring that the underlying plaintext remains hidden throughout the entire computational process. Since the foundational work of Rivest, Adleman, and Dertouzos [2] and Gentry’s first fully homomorphic construction [3], HE has evolved into one of the most powerful techniques for privacy-preserving computation. It is now widely studied in applications such as secure cloud analytics, privacy-preserving machine learning, and encrypted data sharing across healthcare and financial domains.

Despite its strong theoretical guarantees, practical deployment of HE remains challenging. Encrypted computations are computationally demanding, ciphertexts are substantially larger than plaintexts, and performance depends heavily on scheme parameters. Understanding these trade-offs between computational cost, precision, and security is crucial for adapting HE to latency-sensitive and resource-constrained environments, such as those found in wireless communication and Internet of Things (IoT) systems.

HE schemes are typically categorized by the operations they support. Partially Homomorphic Encryption (PHE) [4], including schemes such as Paillier and ElGamal, efficiently supports a single algebraic operation, either addition or multiplication, making it suitable for lightweight aggregation tasks. Somewhat Homomorphic Encryption (SWHE) [5] extends this capability to a limited number of additions and multiplications, but becomes unreliable once accumulated noise exceeds a threshold. Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE), first realized by Gentry [3], enables arbitrary computations through a costly bootstrapping process that refreshes ciphertexts and restores decryptability.

A concise comparison of these three categories, including their computational properties, supported operations, and representative schemes is provided in Table 1. This summary highlights the progression from a simple additive or multiplicative homomorphism toward fully expressive encrypted computation, illustrating the trade-off between functionality and performance.

Table 1.

Comparison of homomorphic encryption categories.

While these categories and their trade-offs are well understood conceptually, few empirical studies have compared their performance under identical experimental conditions. Most previous works focus either on theoretical foundations or isolated implementations, leaving a lack of reproducible benchmarks across multiple HE schemes.

This study aims to fill that gap by conducting a unified performance evaluation of representative HE schemes using three established cryptographic libraries: GMP (for PHE), Microsoft SEAL (for BFV/SWHE), and OpenFHE (for CKKS/FHE). By implementing and benchmarking all three HE types under identical experimental conditions, this work provides a reproducible and comparative framework that enables a deeper understanding of the trade-offs between performance, precision, and security. The experimental analysis measures key metrics such as encryption and decryption latency, arithmetic operation speed, ciphertext expansion, and memory utilization under varying parameter settings. The findings offer new practical insights into the performance and scalability of HE in realistic computing environments, and provide clear guidance for designing efficient, privacy-preserving systems in modern cloud, edge, and wireless communication infrastructures.

To summarize, the main contributions of this work are as follows:

- To develop a unified and reproducible experimental framework for evaluating representative PHE, SWHE, and FHE schemes (Paillier, ElGamal, BFV, CKKS) implemented using GMP, Microsoft SEAL, and OpenFHE under comparable 128-bit security settings.

- To perform a systematic empirical comparison under identical hardware and software conditions, focusing on encryption and decryption time, homomorphic operation latency, ciphertext expansion, memory usage, and noise behaviour across different parameter configurations.

- To analyse how specific parameter choices and design characteristics influence practical efficiency, numerical precision, and security across the three HE paradigms.

- To provide practical recommendations indicating when lightweight PHE or SWHE methods are sufficient and when FHE is required, especially in cloud, edge, and wireless environments.

2. Related Work

Research on HE has advanced considerably over the past decade, addressing both theoretical developments and practical implementation challenges. Several comprehensive surveys provide valuable overviews of the field. Cheon et al. introduced the CKKS scheme for approximate arithmetic, which has since become the de facto standard for real-number computations in FHE [6]. Marcolla et al. presented an extensive survey of FHE theory and applications, emphasizing issues such as noise management, bootstrapping efficiency, and parameter selection [7]. Likewise, Acar et al. offered an early but influential overview summarizing PHE, SWHE, and FHE schemes, together with their implementation status and security assumptions [8].

Alabdulmohsin et al. [9] conducted a performance-oriented review of modern FHE systems, analyzing both theoretical aspects and real-world implementations such as SEAL, HElib, PALISADE, Lattigo, and TFHE. They identified key bottlenecks, including ciphertext expansion, bootstrapping latency, and the absence of standardized benchmarks, issues that motivate the experimental approach of this study.

Practical implementations now form the core of HE research. Microsoft SEAL remains one of the most widely used frameworks, providing optimized BFV and CKKS implementations and serving as a reference for parameter tuning [10]. OpenFHE, the open-source successor to PALISADE, extends this functionality with CKKS bootstrapping and hybrid key switching [11]. These libraries underpin most contemporary experimental evaluations.

Benchmarking frameworks have been developed to enable objective cross-library comparisons. Intel’s HEBench [12] provides a standardized environment for evaluating HE workloads across software and hardware platforms, while FHEBench [13] offers reproducible assessments of runtime, memory, and precision trade-offs. Gong et al. [14] further categorize optimization efforts into algorithmic, architectural, and hardware levels, illustrating the breadth of ongoing work on FHE performance.

At the hardware level, accelerators such as ARK [15] and F1 [16] significantly reduce bootstrapping latency and energy use, while Zhang et al. [17] survey GPU-, FPGA-, and ASIC-based designs. Despite this progress, most hardware-oriented studies focus solely on FHE, with limited consideration of lighter-weight PHE or SWHE schemes.

Applied research extends the use of HE to domains such as healthcare, biometrics, and the IoT. Crihan and Dobre [18] compare HE algorithms for privacy-preserving biometric computation, while Temirbekova et al. [19] evaluate the feasibility of FHE in IoT analytics. Mahato and Chakraborty [20] survey HE-based secure data analytics and advocate hybrid architectures combining HE with lightweight or symmetric encryption. Hybrid HE–MPC frameworks have also been proposed to reduce computational and communication overhead in distributed or resource-constrained environments [21,22].

In summary, existing work shows substantial progress across software, hardware, and application domains. However, most studies focus exclusively on FHE or use non-uniform experimental setups. A reproducible benchmark comparing PHE, SWHE, and FHE schemes under identical conditions is still lacking. This work fills that gap through a unified C++ framework and empirical evaluation of latency, ciphertext expansion, and memory usage, key metrics for secure and efficient cloud computation.

3. Homomorphic Encryption Overview

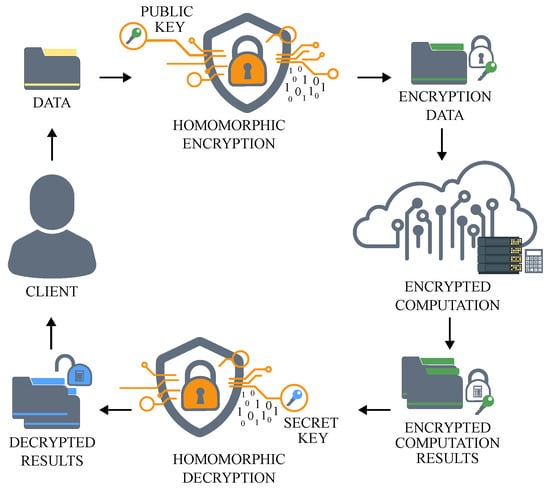

Homomorphic encryption enables computation on ciphertexts such that the result, after decryption, matches the outcome of the same computation on the corresponding plaintexts. As illustrated in Figure 1, this property allows computations to be performed directly on encrypted data, producing a ciphertext that decrypts to the same (or approximately the same) result as the corresponding plaintext operation [8].

Figure 1.

Homomorphic encryption process: data are encrypted, processed in encrypted form, and decrypted to reveal a result equivalent to the plaintext computation.

Formally, if is an encryption function and ∘ a plaintext operation, an HE scheme provides an efficient ciphertext operation ⊗ satisfying

where the symbol “≈” indicates exact equality for exact schemes (e.g., integer arithmetic) or approximate equality when the scheme supports approximate arithmetic (e.g., CKKS) [6,10].

3.1. From Partially to Fully Homomorphic Encryption

HE schemes can be categorized according to the set of algebraic operations they support. PHE schemes enable only a single type of operation, either addition or multiplication, on encrypted data. Representative examples include the Paillier scheme, which provides an additive homomorphism over the ring , and the ElGamal scheme, which achieves a multiplicative homomorphism over a cyclic group [18]. These properties can be expressed as

or, in the multiplicative case,

PHE schemes are computationally efficient but limited in expressiveness, as they cannot support mixed or nested operations.

SWHE schemes extend this capability to both addition and multiplication, but only for a limited number of operations. Each homomorphic multiplication increases the internal noise in the ciphertext, and once this noise exceeds a certain threshold, decryption fails. To mitigate this limitation, FHE introduces a process known as bootstrapping [23], which homomorphically evaluates the decryption function on encrypted data to remove accumulated noise and restore decryptability [3,7]. This innovation allows an unlimited number of operations to be performed on ciphertexts, marking a major milestone in privacy-preserving computation and secure cloud processing.

3.2. Bootstrapping: Concept and Implementation

Bootstrapping is the mechanism that transforms a somewhat homomorphic ciphertext into a refreshed ciphertext with a reduced noise level, thereby enabling additional homomorphic computations. Conceptually, bootstrapping generates a new ciphertext such that while the internal noise of is reset to a low level [3,6]. In other words,

From an implementation perspective, bootstrapping is carried out by homomorphically evaluating the decryption function on encrypted data, that is, executing without revealing the secret key. The decryption function is represented as an arithmetic circuit and evaluated under encryption, producing a new ciphertext that encrypts the same plaintext but with a refreshed noise parameter [6,11].

It should be noted that the specific procedure and internal representation of bootstrapping vary across different HE schemes. For instance, TFHE performs bit-level gate evaluations, BGV and BFV rely on modulus switching, and CKKS uses approximate arithmetic to refresh ciphertexts [24]. In practice, bootstrapping remains substantially more computationally demanding than basic homomorphic operations and typically dominates the overall runtime in FHE workloads. The detailed performance measurements obtained in our experiments are reported in Section 5.

3.3. Lattice Foundations and Security Assumptions

Modern efficient HE schemes are based on hard lattice problems, inheriting post-quantum security from the presumed hardness of the Learning With Errors (LWE) problem and its ring variant, Ring-LWE (RLWE) [25,26]. In the ring setting, let

denote the polynomial ring modulo with coefficients reduced modulo q. An RLWE sample consists of a pair defined as

where is chosen uniformly at random, is the secret (typically small) polynomial, and is an error polynomial sampled from a discrete Gaussian or another narrow distribution. The RLWE assumption states that distinguishing such samples from uniformly random pairs in is computationally intractable under worst-case lattice hardness reductions. This assumption underpins the security of prominent HE schemes, including BFV, BGV, and CKKS [27,28,29].

Parameter Selection and Equivalent Cryptographic Security

The cryptographic security of a HE scheme depends on both its underlying hardness assumption (e.g., Decisional Composite Residuosity for Paillier, Discrete Logarithm for ElGamal, or RLWE for lattice-based schemes) and the appropriate choice of implementation parameters. These parameters determine the scheme’s effective resistance to known attacks, including integer factorization, discrete logarithm computation, and lattice reduction.

To ensure a fair and reproducible comparison across all tested schemes, the parameters in this study were selected to achieve an equivalent 128-bit security level, in accordance with the HE Security Standard [30] and the NIST SP 800-57 recommendations [31]. This level corresponds to the protection strength of AES-128 and represents the current practical baseline for secure applications.

For classical number-theoretic schemes such as Paillier and ElGamal, the primary security parameter is the modulus size, which defines the difficulty of the corresponding mathematical problem. As summarized in Table 2, 3072-bit moduli provide approximately 128-bit security, while 2048-bit parameters correspond to about 112-bit security, in line with NIST recommendations for RSA- and DLP-based systems.

Table 2.

Recommended parameter sizes for classical (partially homomorphic) schemes.

For modern lattice-based schemes, such as BFV, BGV, and CKKS, security is primarily determined by the ring dimension N and the total coefficient modulus size . The ring dimension defines the polynomial space and directly affects both security and computational complexity. The modulus size determines how many homomorphic operations can be performed before noise growth renders decryption unreliable. Together, these parameters define the hardness of the RLWE problem and the achievable multiplicative depth for a given security level.

Table 3 lists representative parameter ranges for 128-, 192-, and 256-bit security levels. Each configuration specifies the polynomial degree N, the total coefficient modulus size , and a typical modulus chain structure. For CKKS, the scaling factor is also shown, as it determines the precision of approximate arithmetic.

Table 3.

Representative parameter ranges for RLWE-based HE schemes. N—polynomial modulus degree; —total coefficient modulus size; —CKKS scaling factor.

In summary, the polynomial modulus degree N affects both security and performance: larger N increases the number of ciphertext slots but also the cost of polynomial arithmetic. The total modulus size defines the supported computation depth before noise prevents correct decryption, while in CKKS, the scaling factor (typically –) balances precision and efficiency. The parameter sets in Table 2 and Table 3 provide balanced configurations ensuring 128-bit security and form the basis of the experimental evaluation in Section 5.

3.4. The CKKS Scheme for Approximate Arithmetic

The CKKS (Cheon–Kim–Kim–Song) scheme enables approximate arithmetic over encrypted real or complex vectors. It encodes plaintext values as elements of a polynomial ring, supporting efficient privacy-preserving numerical computation widely used in data analytics and machine learning applications [6,11].

CKKS represents a plaintext vector m as a polynomial in the ring and applies a scaling factor to map real (or complex) numbers to integer coefficients before encryption. This scaling embeds approximate values into the finite ring rather than using a fixed-point representation. A simplified view of the encryption process (notation aligned with OpenFHE) is

where is uniformly random and are small error polynomials. Decryption reconstructs an approximate plaintext as

yielding due to the presence of noise and rounding errors.

The scaling factor controls the trade-off between numerical precision and noise growth. Typical parameter choices, such as , provide sufficient precision for most machine-learning and statistical workloads while maintaining efficient computation and 128-bit security [6,10].

Homomorphic Operations, Rescaling, and Noise Management

The CKKS scheme supports both homomorphic addition and multiplication of encrypted values. Each ciphertext in CKKS is represented as a pair of ring elements , which together encode an approximate plaintext with a given scale . This scale determines how real numbers are mapped to integers within the finite ring.

Homomorphic addition preserves both the scale and noise level, whereas multiplication increases them. After multiplying two ciphertexts, the resulting scale is approximately , and the ciphertext modulus q must be adjusted accordingly. To prevent uncontrolled growth of the scale and modulus, CKKS performs a rescaling step, which divides the ciphertext coefficients by a fixed factor p corresponding to the last prime modulus in the chain.

Formally, for a ciphertext , rescaling is defined as

where denotes rounding to the nearest integer coefficient. This operation removes one modulus from the chain () and proportionally reduces the scale (), thereby maintaining a stable ratio between plaintext precision and ciphertext magnitude.

Intuitively, rescaling can be viewed as a normalization step that restores numerical balance after multiplication and prevents excessive noise accumulation. Without it, the scale would grow exponentially with each multiplication, eventually making decryption imprecise or impossible. When the remaining modulus or noise budget becomes insufficient for further computation, a bootstrapping procedure (as described previously) is applied to refresh the ciphertext and restore its computational depth [6,11].

3.5. Performance Characteristics and Practical Observations

The performance, numerical precision, and security level of the CKKS scheme are mainly determined by three key parameters:

- Polynomial modulus degree (N): Defines the ring dimension. Increasing N expands the ciphertext space and the number of available plaintext slots (i.e., parallel encoding capacity), but also proportionally increases computation time, memory usage, and ciphertext size.

- Coefficient modulus (q): Represents the product (or chain) of moduli used in the scheme. A larger q enables deeper multiplicative circuits by providing a higher noise budget, but also results in slower arithmetic and larger ciphertexts.

- Scaling factor (): Determines the trade-off between numerical precision and noise growth. Larger values improve precision but cause faster noise accumulation and require larger coefficient moduli.

Polynomial arithmetic dominates the computational cost in CKKS. Homomorphic additions scale linearly as , whereas multiplications and key-switching operations rely on the Number Theoretic Transform (NTT) with complexity [32]. Bootstrapping involves a series of NTTs, key-switching, and polynomial evaluations, and is therefore several orders of magnitude slower than basic homomorphic operations [6,11].

In our experimental setup (Section 5), a single CKKS bootstrap with polynomial modulus degree required approximately 2.2–4.4 s, depending on the parameter configuration. For comparison, typical homomorphic multiplications are completed in under , while additions and decryptions required less than . After bootstrapping, ciphertext size increased from approximately to , while peak RAM consumption remained nearly constant. Detailed measurements and variability analyses are provided in Section 5.

3.6. Applications and Deployment Considerations

HE is increasingly being incorporated into practical privacy-preserving systems across cloud, edge, and wireless environments. Recent studies demonstrate its use in several real deployment scenarios. In cloud-based analytics, HE enables the processing of sensitive medical or population-level data without exposing the underlying records [33]. In edge-oriented machine learning pipelines, encrypted inference and aggregation help protect locally collected data on resource-constrained devices [34]. In wireless sensor networks, HE-based aggregation combined with learning-based control has been shown to improve robustness and security in distributed sensing platforms [35]. Together, these examples indicate that HE is gradually moving from theoretical models toward practical use across diverse computing domains.

The ability to perform computations directly on encrypted data makes HE particularly useful for handling sensitive or regulated information without compromising confidentiality. Its most common application areas include

- Encrypted analytics and machine learning: HE supports privacy-preserving regression, classification, and secure aggregation over sensitive datasets such as medical or financial records. The CKKS scheme is well suited for approximate arithmetic and real-valued inference, while hybrid approaches combining CKKS and BFV have been explored for mixed workloads [19,36].

- Federated learning and secure aggregation: In federated learning, model updates from multiple participants remain local. HE enables encrypted aggregation on the server without exposing individual contributions, thereby strengthening confidentiality in distributed training [21,22].

- Regulatory compliance: Computing on encrypted personal data facilitates compliance with privacy regulations such as GDPR and HIPAA by preventing plaintext exposure during processing [7,20].

In practical deployments, HE must be configured with respect to latency, bandwidth, and hardware capabilities, as ciphertext expansion can significantly increase communication and storage overhead. For this reason, many real-world systems rely on lightweight hybrid architectures, where symmetric encryption is used for bulk data, PHE supports secure aggregation, and FHE is applied selectively for more complex operations. Such combinations often provide a balanced compromise between strong security guarantees and practical performance requirements [19,20].

In addition to concrete application examples, several recent survey studies provide a broader overview of how HE is being adopted across different computing environments. For encrypted analytics and machine learning, Yuan et al. [37] review approximate HE methods and their role in privacy-preserving model training and inference. In the context of federated learning, Caruccio et al. [38] offer a comprehensive categorization of existing approaches, including schemes that integrate HE for secure aggregation of model updates. Regulatory and compliance aspects are discussed in detail by Heinz et al. [39], who examine how HE can support GDPR-aligned processing of personal data within modern IoT and cloud platforms. These studies help situate the application areas within a broader research landscape and highlight how HE is being used in practice across cloud, edge, and wireless systems.

3.7. Hardware Acceleration and Scalability

Many core operations in HE are inherently parallelizable due to the independence of polynomial coefficients and ciphertext slots. Modern implementations exploit multi-threading, vectorization, and hardware acceleration on GPUs, FPGAs, and ASICs to improve performance and energy efficiency. The most demanding primitives, polynomial multiplication, key switching, and bootstrapping, benefit greatly from fine-grained parallelism and optimized memory hierarchies.

Recent accelerators such as ARK [15] and F1 [16] demonstrate large reductions in bootstrapping latency and energy use through dedicated datapaths, pipelined modular arithmetic, and on-chip NTT engines. GPU-based implementations [17,40,41] achieve order-of-magnitude speedups for NTT and ciphertext arithmetic by leveraging massive parallelism and memory bandwidth. At the system level, frameworks such as HEBench [12] enable reproducible, cross-library benchmarking and guide the optimization of parameters, hardware offloading, and runtime scheduling.

Scalability is achieved by distributing ciphertext operations across threads, devices, or nodes. Because ciphertext slots are processed independently, HE computations parallelize naturally, supporting encrypted analytics and privacy-preserving computation at scale in both cloud and edge environments.

Several benchmarking efforts have examined HE from different perspectives, including hardware acceleration, software optimization, and cross-library evaluation. Frameworks such as HEBench provide standardized workloads for comparing specific operations across implementations, while other studies focus primarily on FHE performance or analyze hardware-assisted speedups on GPUs, FPGAs, and ASICs. Compared with these approaches, the methodology adopted in this work offers a unified and directly comparable evaluation of PHE, SWHE, and FHE schemes under identical security levels and a consistent experimental configuration. This broader coverage enables a clearer view of the relative strengths and limitations of the three paradigms as they arise in practical deployments, and complements existing benchmarking efforts by situating the schemes within a common measurement framework.

3.8. Comparative Overview of Homomorphic Encryption

HE schemes can be broadly categorized according to the types of algebraic operations they support and their underlying mathematical hardness assumptions. Classical PHE schemes, such as RSA and ElGamal, rely on modular arithmetic and enable only multiplicative operations, whereas the Paillier scheme achieves additive homomorphism based on the Decisional Residuosity assumption [42], which states that distinguishing n-th residues modulo is computationally hard. Somewhat or leveled homomorphic schemes, including BFV and BGV, extend functionality to both addition and multiplication, though their circuit depth is limited by ciphertext noise growth. In contrast, the CKKS scheme enables approximate arithmetic over real or complex numbers under the RLWE assumption, supporting continuous-valued computations with controllable precision loss.

Table 4 summarizes representative HE schemes along key dimensions such as supported data types, bootstrapping capability, and underlying security assumptions. It highlights the evolution from simple algebraic homomorphisms toward general-purpose encrypted computation, illustrating the trade-offs between performance, precision, and expressiveness. These comparative insights provide the foundation for the experimental evaluation in Section 5.

Table 4.

Representative homomorphic encryption schemes and their core properties.

4. Implementation and Testing of Homomorphic Encryption

This section outlines how we built and tested the components needed for HE in practice. Our goal was to keep the codebase simple to reproduce while still reflecting realistic performance. We therefore used mainstream C++ libraries for PHE, leveled HE, and FHE, and compiled everything with a modern GCC toolchain and consistent CMake presets.

4.1. Development Environment and Libraries

Three families of HE schemes were implemented and evaluated using widely adopted open-source libraries:

- GNU Multiple Precision Arithmetic Library (GMP) (https://gmplib.org/, accessed on 15 October 2025): utilized for PHE primitives such as Paillier. GMP provides efficient multi-precision and modular arithmetic, essential for PHE-style aggregation and number-theoretic operations.

- Microsoft SEAL (https://github.com/microsoft/SEAL, accessed on 15 October 2025): employed for leveled homomorphic encryption with the BFV scheme. SEAL offers robust parameter management (ring dimension, coefficient moduli) and optimized polynomial arithmetic, facilitating reproducible and consistent experiments.

- OpenFHE (https://github.com/openfheorg/openfhe-development, accessed on 15 October 2025): used for CKKS-based FHE, supporting rescaling, key switching, and bootstrapping, thus enabling approximate arithmetic directly on encrypted vectors.

All projects were configured with CMake and compiled using the GNU Compiler Collection (GCC 15.2) with -O3 optimizations enabled for release builds. Where supported, link-time optimization (-flto) and native instruction tuning (-march=native) were enabled to minimize runtime overhead in NTT and big-integer arithmetic routines.

For each library, correctness was verified through encryption–decryption round-trip tests and consistency checks between plaintext and decrypted outputs. Timing measurements were averaged over multiple independent runs to mitigate short-term system variability. This unified build and evaluation environment ensures fair and directly comparable performance results across PHE, SWHE, and FHE configurations.

In this study, the selection of cryptographic libraries follows the goal of providing a consistent and representative comparison across the main categories of HE. GMP is used for PHE schemes such as Paillier and ElGamal because it offers reliable and efficient support for large-integer arithmetic. Microsoft SEAL serves as a stable, widely adopted platform for evaluating the BFV scheme, making it a suitable representative implementation of SWHE. OpenFHE, as the successor of PALISADE, provides comprehensive support for the CKKS scheme, including an efficient bootstrapping mechanism, and is therefore well-suited for experiments requiring FHE functionality. Other libraries, including HElib [43], Lattigo [44], or TFHE [45], were also considered; however, they either target different workloads or introduce additional integration complexity, which would reduce the uniformity of the experimental setup. The selected set of libraries, therefore, offers a balanced and reproducible foundation for comparing PHE, SWHE, and FHE under comparable conditions.

While these libraries provide representative implementations of PHE, SWHE, and FHE, the selected schemes do not cover the full breadth of modern HE. Other frameworks, such as TFHE for bit-level Boolean computation, HElib for BGV-style arithmetic, PALISADE as an earlier generation of lattice-based HE libraries, and generalized BFV variants, support different computation models and may exhibit distinct performance characteristics, particularly in hardware-accelerated or application-specific deployments. A broader evaluation of these alternative schemes lies beyond the scope of the present study, which focuses on a unified comparison of widely used representatives under consistent security and implementation conditions, but they remain important candidates for future benchmarking work.

4.2. Implementation Details

In the case of PHE, algorithms such as Paillier and ElGamal were implemented using GMP. The implementation included the generation of key pairs, encryption and decryption procedures, and verification of homomorphic addition or multiplication properties. Performance testing focused on the encryption and decryption time for increasing numbers of input values.

For the SWHE implementation, the Microsoft SEAL library was employed to realize the BFV scheme. Parameters such as the polynomial modulus degree and coefficient modulus were carefully tuned to balance between computational depth, noise growth, and security level. The library’s native functionalities enabled direct execution of homomorphic addition and multiplication, as well as performance evaluation for various input sizes.

The FHE implementation was based on the CKKS scheme within OpenFHE. This scheme supports arithmetic operations over encrypted real numbers by encoding floating-point data into complex number space. The implemented procedures included key generation, encoding and encryption, homomorphic addition and multiplication, and finally decryption to recover the plaintext. Additionally, the bootstrapping process was tested to restore computational depth after multiple operations.

4.3. Testing and Performance Evaluation

All implementations were tested under identical hardware and software conditions to ensure a fair and reproducible comparison. The experiments were carried out on a workstation running Windows 11 (64-bit) and equipped with an Intel Core i5-9300H CPU (4 cores, 8 threads, 2.40 GHz) and 16 GB of DDR4 RAM. All code was written in C++ and compiled using the GCC 15.2 through CMake in release mode with the -O3 optimization flag. The same compiler toolchain and build configuration were applied to GMP, Microsoft SEAL, and OpenFHE to ensure consistency across all experiments.

The evaluation focused on several practical metrics, including encryption and decryption time, ciphertext size, memory consumption, and the impact of different parameter configurations on overall performance. These metrics were selected because they capture the key factors that influence the feasibility of deploying HE in real systems. Encryption and decryption time determine the responsiveness of applications that frequently process new encrypted inputs. Ciphertext size directly affects bandwidth requirements and storage overhead, which becomes critical in cloud, edge, or wireless environments with constrained communication resources. Memory consumption impacts the usability of HE on resource-limited platforms, including IoT and edge devices. The behaviour of performance under different parameter selections, such as changes in modulus size or polynomial degree, is essential for understanding how security choices translate into computational cost. Together, these metrics provide a comprehensive view of how HE schemes behave in realistic deployment scenarios.

The aim of the testing phase was to examine the practical behavior of the three HE paradigms under a unified experimental setup, rather than to optimize any specific implementation. The selected libraries provided a consistent basis for evaluating representative PHE, SWHE, and FHE schemes and allowed us to observe how each paradigm responds to changes in security levels and parameter settings.

5. Experimental Results

This section presents the empirical results obtained from benchmarking the PHE, SWHE, and FHE schemes under the unified experimental setup described in Section 4. The measurements quantify the impact of different parameters on runtime, memory consumption, ciphertext expansion, and noise behaviour. The results also illustrate how the three HE paradigms differ in terms of computational cost and functional capacity, forming the basis for the analysis discussed in Section 6.

5.1. Experimental Setup

All experiments were conducted on a workstation equipped with an Intel Core i5-9300H CPU (4 cores, 8 threads, 2.40 GHz), 16 GB of DDR4 RAM, running Windows 11 (64-bit). All implementations were written in C++ and built using CMake with the GNU Compiler Collection (GCC 15.2). Programs were compiled in release mode with the -O3 optimization flag to ensure consistent and comparable execution times across the evaluated libraries. Two HE libraries were used: Microsoft SEAL (v4.1) implementing the BFV scheme and OpenFHE (v1.1.1) implementing the CKKS scheme. All reported results represent the mean of ten independent runs, accompanied by the corresponding standard deviation. Measured quantities included key generation, encryption, decryption, homomorphic addition, multiplication, relinearization, and bootstrapping times. Relinearization denotes the post-multiplication step that reduces a ciphertext from three to two components using evaluation keys, thereby preventing an increase in both computational cost and accumulated noise.

5.2. Baseline Partially Homomorphic Schemes

For reference, PHE schemes such as Paillier and ElGamal were implemented using the GMP library. These implementations serve as a baseline for comparison with more advanced HE schemes. Both algorithms were evaluated on datasets of increasing size, corresponding to batches of 100, 1000, and 10,000 encrypted values. Each experiment measured the average time required for key generation, encryption, decryption, and homomorphic aggregation over these datasets.

The Paillier cryptosystem was implemented following its standard mathematical formulation [46]. It provides an additive homomorphic property, enabling the computation of plaintext sums through ciphertext multiplication. In this study, the implementation relied on the GMP to efficiently handle large integer operations and modular exponentiation.

The Paillier cryptosystem operates over a composite modulus , where p and q are two large, distinct prime numbers. The security of the scheme relies on the difficulty of solving problems related to modular arithmetic over this composite modulus.

The key generation process defines two main keys:

- Public key: , where is a generator used during encryption. The public key is shared with all users who need to encrypt data.

- Private key: , used for decryption. Here, represents the least common multiple of and ; this value ensures compatibility between the two prime factors. The term denotes the modular inverse of modulo n, which enables recovery of the original plaintext during decryption.

A plaintext message is encrypted using a random value as

The random factor r guarantees that encrypting the same message twice produces different ciphertexts, which prevents attackers from detecting repeated plaintexts.

Decryption uses the private key to recover m from c:

The auxiliary function extracts information from values modulo and is essential for reconstructing the original plaintext.

The Paillier scheme supports additive homomorphism: multiplying two ciphertexts corresponds to adding the underlying plaintexts, i.e.,

This property allows computations such as summations or averages to be performed directly on encrypted data, without revealing individual plaintext values.

In our prototype implementation, the Paillier cryptosystem was used to demonstrate and validate the additive homomorphic property in practice. For realistic deployments, cryptographic security requires large prime moduli, typically at least 1024 bits, to prevent factorization attacks and ensure compliance with modern security standards [8]. This implementation serves as a baseline for comparing PHE with more advanced SWHE and FHE schemes in Section 5.

The ElGamal cryptosystem [47] operates over a multiplicative cyclic group defined by a large prime modulus p. It provides a multiplicative homomorphic property, meaning that the product of ciphertexts corresponds to the product of the underlying plaintexts after decryption. This characteristic makes it useful for secure aggregation and computations that rely on multiplication in privacy-preserving applications.

The key generation process defines two main keys:

- Public key: , where g is a generator of the group , and . The public key parameters are shared with all parties performing encryption.

- Private key: x, a randomly selected integer from the range . The value x must remain secret and is used during decryption.

A plaintext message is encrypted using a randomly chosen ephemeral key . The encryption process produces a ciphertext pair:

The random value y ensures that encrypting the same message multiple times produces distinct ciphertexts, which prevents attackers from recognizing identical plaintexts.

Decryption is performed using the private key x. The recipient computes an auxiliary value and then recovers the plaintext as

where denotes the modular inverse of s modulo p, i.e., the value satisfying .

The multiplicative homomorphism of ElGamal encryption is verified by the relation:

where denotes the ciphertext pair corresponding to plaintext . The component-wise multiplication of two ciphertexts,

produces a valid encryption of the product of the two plaintexts. In other words, multiplying ciphertexts results in the encryption of .

For experimental evaluation, the ElGamal implementation was used to validate the multiplicative homomorphism and to benchmark core cryptographic operations, including key generation, encryption, decryption, and ciphertext multiplication. As with the Paillier cryptosystem, the GMP was employed to efficiently handle modular exponentiation and large-integer arithmetic.

In practical deployments, secure configurations rely on large prime moduli (typically at least 2048 bits) and cryptographically secure random number generators (CSPRNGs) for generating the ephemeral key y. These measures are essential to ensure resistance against discrete logarithm attacks and to comply with modern cryptographic security recommendations [8].

As shown in Table 5, both the time and memory requirements increase approximately linearly with the number of encrypted values. Since the size of a single ciphertext remains constant, the overall data volume scales proportionally to the input size.

Table 5.

Average performance comparison of Paillier and ElGamal encryption schemes.

To extend the previous analysis, the same methodology was applied to the ElGamal scheme, which provides a multiplicative rather than additive homomorphism. When compared with Paillier, ElGamal achieves notably shorter encryption and decryption times for an equal number of inputs. For instance, when processing 10,000 values, ElGamal encryption was about 2.3× faster and decryption about 12× faster than Paillier.

The ciphertext size and memory usage were comparable for both schemes, as each ElGamal ciphertext consists of two components with a total size of roughly 256 bytes. Overall, ElGamal is more efficient in terms of computational cost, particularly for large datasets and multiplicative operations, whereas Paillier remains an effective choice for applications requiring homomorphic addition.

5.3. Baseline Somewhat Homomorphic Schemes

The performance of the BFV scheme was evaluated using the Microsoft SEAL library (v4.1), an open-source framework for HE that enables computations to be carried out directly on encrypted data. This approach ensures that plaintexts remain confidential throughout all stages of computation and allows the development of fully encrypted end-to-end processing pipelines and secure cloud services without exposing decryption keys to external entities.

The efficiency and accuracy of BFV computations depend on a set of key cryptographic parameters that jointly determine the trade-off between performance, security, and noise tolerance. In this study, the polynomial modulus degree was set to , providing a balance between computational cost and the depth of supported operations. The coefficient modulus followed SEAL’s default configuration for approximately 128-bit security, while the plaintext modulus was fixed at , which offers efficient integer arithmetic for typical encrypted workloads. The plaintext modulus t defines the numeric range in which plaintext arithmetic is performed: all BFV computations occur modulo t, meaning that values wrap around this modulus. Larger values of t allow a broader representable range of plaintexts but may increase noise growth, whereas smaller values reduce noise at the cost of a narrower arithmetic domain. All timing results represent the average of ten runs using identical random plaintext vectors of 1000 integers.

Table 6 demonstrates that the available noise budget decreases after each homomorphic operation, particularly following multiplications and relinearizations. Larger polynomial modulus degrees provide higher residual noise budgets, enabling deeper computational circuits at the cost of increased runtime and memory consumption. As expected, the runtime of all operations grows approximately linearly with the polynomial modulus degree, consistent with the complexity of polynomial arithmetic. These results highlight the inherent trade-off between computational depth and performance in the BFV scheme, emphasizing the need for parameter tuning based on application-specific latency and accuracy requirements.

Table 6.

Noise budget (in bits) and average runtime (in milliseconds) of BFV operations evaluated under different polynomial modulus degrees N.

The polynomial modulus degree N plays a crucial role in balancing computational efficiency and numerical stability. Smaller degrees () offer faster execution but quickly deplete the available noise budget, limiting the number of homomorphic operations that can be performed without bootstrapping. Conversely, higher degrees () support a greater multiplicative depth and improved resistance to noise accumulation, albeit at the cost of increased computational and memory overhead.

Among the evaluated operations, multiplication is the most computationally demanding (≈18.6 ms for ), while addition and decryption remain relatively lightweight. These findings are consistent with the theoretical behavior of the BFV scheme, where noise growth scales with the multiplicative depth and is inversely related to the polynomial modulus size.

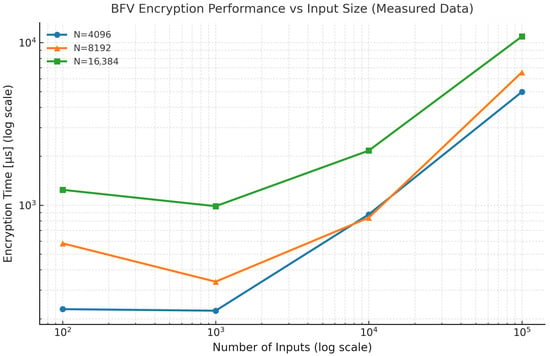

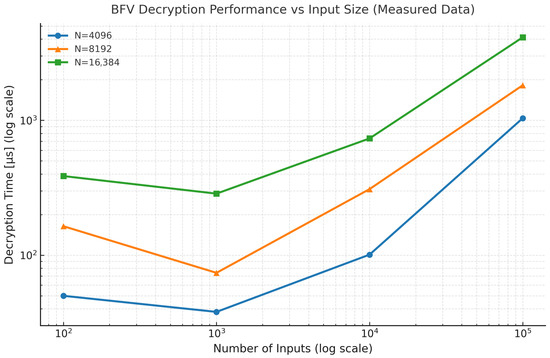

5.3.1. Scaling Behavior and Parameter Impact on BFV Performance

The effect of the polynomial modulus degree (N) and input size on the computational efficiency of the BFV scheme was analyzed using the Microsoft SEAL library. Random integer datasets of varying sizes (100, 1000, 10,000, and 100,000 elements) were encrypted and decrypted to evaluate execution time (in µs), ciphertext size (in MB), and peak memory consumption (in MB). This experiment aimed to assess the scalability of BFV encryption with respect to the number of inputs and parameter configuration.

For all tested configurations, the runtime scaled approximately linearly with the number of inputs and nearly quadratically with the polynomial modulus degree N. The smallest configuration () provided the fastest execution at the cost of a smaller noise budget and lower security margin, while N = 16,384 achieved higher precision and security at a higher computational cost. Memory consumption increased modestly (from approximately 12 MB to 130 MB), remaining within practical limits for standard computing platforms. These findings confirm that the BFV scheme exhibits predictable scalability, balancing performance, accuracy, and cryptographic strength. Encryption results are shown in Figure 2, and the corresponding decryption results in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Measured encryption time of the BFV scheme for different polynomial modulus degrees (N = 4096, 8192, 16,384). Both axes are in logarithmic scale. Each marker represents the average runtime for encrypting datasets of 100–100,000 values. The results show near-linear scaling of execution time with input size and proportional growth with larger N values.

Figure 3.

Measured decryption time of the BFV scheme for different polynomial modulus degrees (N = 4096, 8192, 16,384). Both axes are in logarithmic scale. Each marker corresponds to the average decryption time for the same dataset sizes as in Figure 2. The trends confirm that runtime increases consistently with N, reflecting the computational cost of polynomial arithmetic in higher-dimensional rings.

5.3.2. Impact of Homomorphic Operations on Runtime and Noise Budget

The performance of homomorphic addition and multiplication operations was evaluated at with a plaintext modulus . The experiments measured runtime, noise budget, and memory usage during consecutive encrypted computations.

Homomorphic addition causes negligible noise growth, with the noise budget remaining effectively constant across repeated operations. The average runtime per addition is approximately 220 µs, and the memory footprint remains stable around 109 MB, indicating that addition is computationally lightweight and predictable. The measured characteristics of homomorphic addition are summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

BFV addition: noise budget and performance characteristics.

In contrast, homomorphic multiplication incurs a substantially higher computational cost and memory demand. Each multiplication reduces the noise budget by roughly 30 bits and increases runtime by about two orders of magnitude compared to addition. The measured characteristics of homomorphic multiplication are summarized in Table 8. The required relinearization step adds further overhead but is essential to maintain ciphertext size and ensure correct decryption.

Table 8.

BFV multiplication: noise budget and performance characteristics.

Overall, these results confirm that addition operations in the BFV scheme are nearly noise-free and highly efficient, whereas multiplication introduces rapid noise consumption and significant computational overhead. Proper parameter selection and circuit-depth optimization are therefore critical for maintaining decryptability and runtime efficiency in practical applications.

5.4. Performance Evaluation of Fully Homomorphic Encryption

The performance evaluation of FHE was conducted using the CKKS scheme implemented in the OpenFHE library (version 1.1.1). All experiments were executed on the same workstation configuration described earlier (Intel Core i5-9300H, 16 GB DDR4 RAM, Windows 11 64-bit). CKKS was chosen because it supports approximate arithmetic over real numbers, making it particularly suitable for encrypted analytics and privacy-preserving computation on continuous data. The OpenFHE framework provides an optimized implementation of bootstrapping, a mechanism that refreshes ciphertexts and restores the noise budget after multiple homomorphic operations.

5.4.1. Cryptographic Parameter Configuration

The cryptographic context was initialized with the following parameters:

- Ring dimension : defines the size of the polynomial ring and determines both computational parallelism and the number of encoding slots ().

- Secret key distribution: ternary uniform distribution , providing efficient sampling and balanced noise.

- Security level: manually selected to balance precision and performance rather than using predefined security presets.

- Key switching method: Brakerski–Fan (BF) for lightweight operations such as addition, and hybrid switching for computationally intensive operations such as multiplication and bootstrapping.

- Scaling and modulus sizes: flexible automatic scaling using 59-bit prime moduli and a 60-bit initial modulus, ensuring stable precision while maintaining a reasonable noise margin.

- Activated features: public-key encryption, key switching, leveled and bootstrapped operations, enabling the full FHE workflow.

Key generation and evaluation-key setup were performed prior to execution to support multiplicative operations of higher depth. During experiments, the environment automatically managed ciphertext levels, modulus switching, and scaling, ensuring that the noise budget remained within decryptable limits throughout all computations.

5.4.2. Data Encoding and Encryption Process

Plaintext data were represented as real-valued vectors of length not exceeding , corresponding to the number of available encoding slots in the CKKS scheme. Each vector was encoded into a plaintext polynomial and then encrypted to produce the ciphertext representation. During encryption, the following metrics were recorded:

- encryption time,

- ciphertext size (in bytes),

- peak memory consumption (in MB).

Decryption was subsequently applied to verify computational correctness by comparing the decrypted outputs with the original plaintext values, confirming the reversibility of the homomorphic processing pipeline.

5.4.3. Effect of Ring Dimension on Performance

To assess the scalability of CKKS, encryption was tested for two ring dimensions ( and ), corresponding to 2048 and 8192 available slots. Table 9 summarizes encryption and decryption performance, ciphertext size, and memory usage. A larger ring dimension increases ciphertext capacity but also linearly increases computational cost and memory footprint.

Table 9.

Effect of ring dimension on CKKS encryption and decryption performance.

As observed, increasing the ring dimension results in larger ciphertexts (from 120 kB to nearly 500 kB) and higher memory usage, yet encryption and decryption times remain within a few milliseconds, demonstrating good scalability.

5.4.4. Homomorphic Addition and Multiplication Analysis

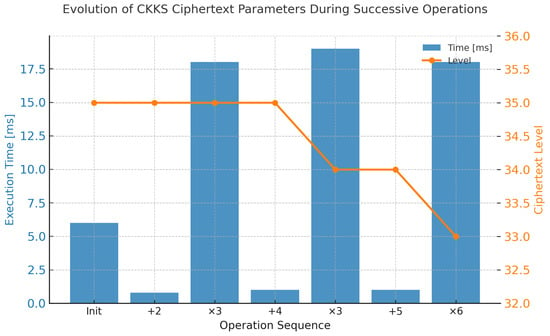

Homomorphic addition and multiplication were evaluated to illustrate their computational asymmetry and level reduction behavior in the CKKS scheme. Figure 4 shows that multiplication dominates execution time due to rescaling and key-switching overhead, while addition remains nearly instantaneous.

Figure 4.

Evolution of CKKS ciphertext parameters during consecutive operations. Multiplication (·) operations are significantly slower and reduce the ciphertext level, whereas additions (+) are nearly instantaneous. Ciphertext size slightly decreases with each rescaling, while memory usage remains nearly constant, confirming efficient management of intermediate buffers during homomorphic computation.

Each multiplication reduces the ciphertext level by one, consistent with modular chain reduction, and slightly decreases the ciphertext size as coefficients are rescaled. Throughout all operations, the ciphertext memory footprint remains stable (around 660–670 MB), indicating efficient in-place processing and key reuse within the evaluator.

5.4.5. Bootstrapping and Level Restoration

When repeated multiplications exhausted the available ciphertext levels, a bootstrapping procedure was applied to refresh the ciphertext and restore its computational depth. The corresponding performance metrics are summarized in Table 10.

Table 10.

Parameter evolution during the CKKS bootstrapping process.

Bootstrapping successfully restored the ciphertext level from 2 to 16, enabling additional homomorphic operations without re-encryption. Although the process introduced a latency of approximately 2.2 s and temporarily increased the ciphertext size nearly fivefold, it preserved decryptability and continuity of computation. Memory usage remained stable (around 670 MB), demonstrating efficient resource management by the underlying implementation.

5.4.6. Numerical Precision and Comparative Analysis

Numerical precision and performance for representative CKKS operations with are summarized in Table 11. The mean squared error (MSE) between plaintext and decrypted results remained below for all evaluated operations, confirming the suitability of the CKKS scheme for approximate analytics in practical settings.

Table 11.

Numerical precision and ciphertext size for CKKS operations with . MSE values are computed between plaintext and decrypted outputs.

As expected, bootstrapping dominates the computational cost, being roughly six orders of magnitude slower than basic arithmetic operations. Nevertheless, this step is essential to restore full homomorphic depth and enable continued computation on encrypted data. The observed MSE values indicate negligible precision loss, validating CKKS as an efficient and accurate scheme for approximate encrypted computation.

5.4.7. Plaintext vs. Homomorphic Computation

To quantitatively assess the computational overhead introduced by HE, a variance computation was performed on 4000 randomly generated integers uniformly distributed within the range . The same operation was executed both in plaintext and under different encryption paradigms using representative homomorphic schemes (BFV and CKKS). Table 12 reports the measured execution times, ciphertext sizes, memory usage, and relative slowdowns for each configuration.

Table 12.

Execution time, ciphertext size, memory usage, and relative performance for variance computation on 4000 integers under different encryption schemes. Dashes indicate values not applicable to plaintext computation.

As observed in Table 12, PHE (BFV) operations incur a computational slowdown of approximately four orders of magnitude compared with direct arithmetic. This performance degradation primarily arises from ciphertext expansion and modular polynomial arithmetic. The leveled variant of CKKS (without bootstrapping) exhibits an even higher overhead, reflecting the cost of rescaling and key-switching operations required to manage noise growth during multiplicative depth expansion. When bootstrapping is enabled, CKKS achieves FHE functionality by refreshing the accumulated noise and restoring ciphertext validity at the expense of an additional three orders of magnitude in runtime. Despite this substantial computational cost, homomorphic computation guarantees complete data confidentiality, as all intermediate values remain encrypted throughout the processing pipeline. These findings highlight the fundamental trade-off between computational efficiency and privacy preservation inherent in HE, illustrating that performance remains application-dependent and strongly influenced by parameter selection and the chosen level of homomorphism.

6. Discussion of Results

This section discusses the implications of the measured performance characteristics and interprets how the observed behavior of the three HE paradigms relates to practical deployment requirements.

Table 13 provides an overview of the principal performance metrics obtained in this study and illustrates the expected trade-offs across PHE, SWHE, and FHE. PHE achieves high computational efficiency and minimal ciphertext expansion, SWHE extends functionality to bounded-depth arithmetic at moderate computational cost, and FHE offers full expressiveness at the expense of significantly higher latency and memory usage. These trends reflect established characteristics of the underlying cryptographic designs and are consistent with observations in the literature.

Table 13.

Cross-scheme comparison of average performance metrics for representative homomorphic encryption implementations.

6.1. Interpretation of Experimental Findings

The results reveal several consistent behavioral trends across all evaluated HE paradigms. PHE schemes offer fast encrypted operations and low memory usage but support only one type of algebraic operation. SWHE provides a broader computational model and supports limited-depth arithmetic, though its performance depends heavily on noise growth and parameter selection. FHE offers the most flexible computation model but incurs high latency and memory overhead, primarily due to rescaling and bootstrapping operations. Across all paradigms, ciphertext expansion significantly increases bandwidth and storage requirements, which plays a critical role in distributed or wireless deployments.

These findings suggest that practical HE deployment requires careful coordination of latency, bandwidth, and hardware capabilities. PHE and SWHE can effectively support lightweight encrypted processing or aggregation tasks, whereas FHE is most appropriate for applications requiring strong privacy guarantees and more complex computation. Parameter tuning and hybrid cryptographic designs can further mitigate performance bottlenecks, especially in environments with constrained communication or processing resources.

It should also be noted that the performance results presented in this study reflect the capabilities of a standard workstation-class CPU and do not capture the substantial acceleration achievable on specialized hardware. Modern cloud infrastructures commonly deploy GPUs, FPGAs, and ASIC-based accelerators that can significantly reduce the cost of polynomial arithmetic, key switching, and bootstrapping. Likewise, edge and IoT-class devices exhibit opposite characteristics, where constrained compute, memory, and power resources impose tighter limits on HE workloads. Distributed and multi-node execution models can further alter performance by enabling parallel evaluation of ciphertext slots or task-level partitioning. Exploring these hardware-dependent behaviours lies beyond the scope of the present work, but represents an important direction for future research.

Furthermore, the scalability results presented in this study should be interpreted in light of the fact that all experiments were executed on a single workstation. The evaluation does not include distributed or multi-node experiments, which can significantly alter performance through task-level parallelism, ciphertext-slot parallelism, or load balancing across compute nodes. As a result, the scalability trends reported here reflect single-node behavior and do not fully capture the potential gains achievable in cloud-scale deployments or distributed processing frameworks. Investigating multi-node execution models represents an important direction for future validation.

6.2. Implications for Secure Communication Systems

The experimental results demonstrate how HE can improve privacy and data protection in modern communication systems. By supporting encrypted computation throughout the processing pipeline, HE enables sensitive data to remain confidential even when handled by untrusted infrastructure. PHE and SWHE are suitable for embedded or resource-limited systems, where they support encrypted aggregation or basic computation with low overhead. FHE offers the ability to compute on encrypted real-valued data, enabling privacy-preserving analytics or secure offloading of computation to the cloud. Integrating HE into communication architectures provides a pathway toward privacy-preserving distributed processing without relying on fully trusted intermediaries.

6.3. Discussion Summary

Overall, the results underline the fundamental trade-offs between computational efficiency, functional expressiveness, and resource consumption across PHE, SWHE, and FHE. These experimental insights help clarify how these schemes behave in realistic environments and inform design choices for secure and privacy-preserving communication systems.

7. Conclusions

This work presented a unified experimental framework for evaluating representative PHE, SWHE, and FHE schemes using GMP, Microsoft SEAL, and OpenFHE under comparable conditions. The results provide a clear view of the practical trade-offs between efficiency, expressiveness, and resource requirements, offering a useful basis for selecting appropriate HE schemes in privacy-preserving applications.

The developed framework is reproducible and can be extended to additional HE libraries or specialized deployment environments. Future work will focus on optimizing HE parameter choices for latency- and power-constrained systems, exploring hardware-assisted acceleration, and evaluating hybrid cryptographic designs that combine lightweight primitives with selective homomorphic computation.

A complementary direction will involve extending the performance evaluation to realistic cloud and distributed computing environments. While the present study provides a unified single-node CPU baseline, large-scale deployments frequently rely on parallel, multi-node execution and accelerator-backed compute infrastructures. To investigate these scalability aspects, we plan to validate the experimental framework on high-performance platforms, including the new PERUN supercomputing infrastructure at our university, which offers GPU- and cluster-level resources suitable for benchmarking HE at cloud scale. Such experiments will enable a more comprehensive assessment of scalability, throughput, and workload distribution patterns in environments representative of modern cloud-based services.

Additional research will also examine methods for reducing ciphertext expansion and transmission overhead, and will assess HE-based processing in prototype communication and edge-computing testbeds. These efforts aim to support the practical deployment of HE in next-generation secure and privacy-preserving communication systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.K. and M.D.; Formal analysis, E.K. and M.P.; Funding acquisition, M.P. and M.D.; Investigation, V.K.; Methodology, E.K. and M.D.; Resources, M.P. and M.D.; Supervision, M.P. and M.D.; Validation, E.K. and M.P.; Visualization, E.K. and M.P.; Writing—original draft, E.K., M.P., V.K. and M.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was partially supported by the Ministry of Education, research, development, and Youth of the Slovak Republic under the projects KEGA 049TUKE-4/2024 & KEGA 041TUKE-4/2025, and by the Slovak Research and Development Agency under the projects APVV-22-0414 & APVV-22-0261.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Doan, T.V.T.; Messai, M.L.; Gavin, G.; Darmont, J. A survey on implementations of homomorphic encryption schemes. J. Supercomput. 2023, 79, 15098–15139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivest, R.L.; Shamir, A.; Adleman, L. A method for obtaining digital signatures and public-key cryptosystems. Commun. ACM 1978, 21, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentry, C. Fully homomorphic encryption using ideal lattices. In Proceedings of the Forty-First Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, Bethesda, MD, USA, 31 May 31–2 June 2009; pp. 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.; Kim, K.; Won, D. A study on partially homomorphic encryption. In Proceedings of the 2023 17th International Conference on Ubiquitous Information Management and Communication (IMCOM), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 3–5 January 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniyaswamy, V.; Jagadeeswari, V.; Indragandhi, V.; Jhaveri, R.H.; Vijayakumar, V.; Kotecha, K.; Ravi, L. Somewhat homomorphic encryption: Ring learning with error algorithm for faster encryption of IoT sensor signal-based edge devices. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2022, 2022, 2793998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, J.H.; Kim, A.; Kim, M.; Song, Y. Homomorphic Encryption for Arithmetic of Approximate Numbers. In Advances in Cryptology, Proceedings of the ASIACRYPT 2017, 23rd International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptology and Information Security, Hong Kong, China, 3–7 December 2017; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 10624, pp. 409–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcolla, C.; Sucasas, V.; Manzano, M.; Bassoli, R.; Fitzek, F.H.; Aaraj, N. Survey on fully homomorphic encryption, theory, and applications. Proc. IEEE 2022, 110, 1572–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, A.; Aksu, H.; Uluagac, A.S.; Conti, M. A survey on homomorphic encryption schemes: Theory and implementation. ACM Comput. Surv. 2018, 51, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.J.; Taha, D.B. Performance evaluation of RSA, ElGamal, and paillier partial homomorphic encryption algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Computer Science and Software Engineering (CSASE), Duhok, Iraq, 15–17 March 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Laine, K.; Player, R. Simple encrypted arithmetic library-SEAL v2.1. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Financial Cryptography and Data Security, Sliema, Malta, 7 April 2017; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Badawi, A.; Bates, J.; Bergamaschi, F.; Cousins, D.B.; Erabelli, S.; Genise, N.; Halevi, S.; Hunt, H.; Kim, A.; Lee, Y.; et al. Openfhe: Open-source fully homomorphic encryption library. In Proceedings of the 10th Workshop on Encrypted Computing & Applied Homomorphic Cryptography, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 7 November 2022; pp. 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HEBench Contributors. Homomorphic Encryption Benchmarking Framework—HEBench. 2023. Available online: https://github.com/hebench (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Jiang, L.; Ju, L. Fhebench: Benchmarking fully homomorphic encryption schemes. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.00728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Chang, X.; Mišić, J.; Mišić, V.B.; Wang, J.; Zhu, H. Practical solutions in fully homomorphic encryption: A survey analyzing existing acceleration methods. Cybersecurity 2024, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, G.; Kim, S.; Sohn, G.; Rhu, M.; Kim, J.; Ahn, J.H. Ark: Fully homomorphic encryption accelerator with runtime data generation and inter-operation key reuse. In Proceedings of the 2022 55th IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Microarchitecture (MICRO), Chicago, IL, USA, 1–5 October 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 1237–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samardzic, N.; Feldmann, A.; Krastev, A.; Devadas, S.; Dreslinski, R.; Peikert, C.; Sanchez, D. F1: A fast and programmable accelerator for fully homomorphic encryption. In Proceedings of the MICRO-54: 54th Annual IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Microarchitecture, Virtual, 18–22 October 2021; pp. 238–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cheng, X.; Yang, L.; Hu, J.; Liu, X.; Chen, K. Sok: Fully homomorphic encryption accelerators. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crihan, G.; Crăciun, M.; Dumitriu, L. A comparative assessment of homomorphic encryption algorithms applied to biometric information. Inventions 2023, 8, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temirbekova, Z.E.; Turken, G.; Barata, M.M. Using Fully Homomorphic Encryption in IoT. In Proceedings of the DTESI 2023—8th International Conference on Digital Technologies in Education, Science and Industry, Almaty, Kazakhstan, 6–7 December 2023; Available online: https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-3680/S4Paper14.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Mahato, G.K.; Chakraborty, S.K. A comparative review on homomorphic encryption for cloud security. IETE J. Res. 2023, 69, 5124–5133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahinbas, K.; Catak, F.O. Secure multi-party computation-based privacy-preserving data analysis in healthcare IoT systems. In Interpretable Cognitive Internet of Things for Healthcare; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D. Secure cloud computing algorithm using homomorphic encryption and multi-party computation. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Information Networking (ICOIN), Bangkok, Thailand, 11–14 January 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Deryabin, M.; Eom, J.; Choi, R.; Lee, Y.; Ghang, W.; Yoo, D. General bootstrapping approach for RLWE-based homomorphic encryption. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2023, 73, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Badawi, A.; Polyakov, Y. Demystifying Bootstrapping in Fully Homomorphic Encryption. Cryptology ePrint Archive. 2023. Available online: https://eprint.iacr.org/2023/149 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Gentry, C.; Sahai, A.; Waters, B. Homomorphic encryption from learning with errors: Conceptually-simpler, asymptotically-faster, attribute-based. In Advances in Cryptology, Proceedings of the CRYPTO 2013 33rd Annual Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 18–22 August 2013; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Goldwasser, S.; Mossel, S. Deniable fully homomorphic encryption from learning with errors. In Advances in Cryptology, Proceedings of the CRYPTO 2021 41st Annual International Cryptology Conference, CRYPTO 2021, Virtual, 16–20 August 2021; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 641–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regev, O. On Lattices, Learning with Errors, Random Linear Codes, and Cryptography. J. ACM 2009, 56, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, M.R.; Player, R.; Scott, S. On the Concrete Hardness of Learning with Errors. Cryptology ePrint Archive. 2015. Available online: https://eprint.iacr.org/2015/046 (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Ding, J.; Branco, P.; Schmitt, K.; Key Exchange and Authenticated Key Exchange with Reusable Keys Based on RLWE Assumption. Cryptology ePrint Archive, Paper 2019/665. 2019. Available online: https://eprint.iacr.org/2019/665 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Albrecht, M.; Chase, M.; Chen, H.; Ding, J.; Goldwasser, S.; Gorbunov, S.; Halevi, S.; Hoffstein, J.; Laine, K.; Lauter, K.; et al. Homomorphic Encryption Standard. Cryptology ePrint Archive, Paper 2019/939. 2019. Available online: https://eprint.iacr.org/2019/939 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Barker, E.; Chen, L.; Roginsky, A.; Smid, M.; Dang, Q.T. Recommendation for Key Management, Part 1: General; Technical Report NIST Special Publication 800-57 Part 1, Revision 5; National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST): Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Boemer, F.; Kim, S.; Seifu, G.; DM de Souza, F.; Gopal, V. Intel HEXL: Accelerating homomorphic encryption with Intel AVX512-IFMA52. In Proceedings of the 9th on Workshop on Encrypted Computing & Applied Homomorphic Cryptography, Virtual, 15 November 2021; pp. 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeogu, A.O. Homomorphic Encryption in Healthcare Analytics: Enabling Secure Cloud-Based Population Health Computations. J. Adv. Res. 2025, 1, 42–60. Available online: https://joaresearch.com/index.php/JOAR/article/view/21 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Khan, M.J.; Fang, B.; Cimino, G.; Cirillo, S.; Yang, L.; Zhao, D. Privacy-preserving artificial intelligence on edge devices: A homomorphic encryption approach. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Web Services (ICWS), Shenzhen, China, 7–13 July 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheela, M.S.; Jayakanth, J.; Ramathilagam, A.; Gracewell, J. Secure wireless sensor network transmission using reinforcement learning and homomorphic encryption. Int. J. Data Sci. Anal. 2025, 20, 2851–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, S.; Cui, H.; Tang, Z.; Li, Y. A review of homomorphic encryption for privacy-preserving biometrics. Sensors 2023, 23, 3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J.; Liu, W.; Shi, J.; Li, Q. Approximate homomorphic encryption based privacy-preserving machine learning: A survey. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruccio, L.; Cimino, G.; Deufemia, V.; Iuliano, G.; Stanzione, R. Surveying federated learning approaches through a multi-criteria categorization. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 36921–36951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, C.; Wall, N.; Wansch, A.H.; Grimm, C. Privacy, GDPR, and homomorphic encryption. In IoT Platforms, Use Cases, Privacy, and Business Models: With Hands-on Examples Based on the VICINITY Platform; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gao, H.; Zhang, J.; Yang, S.; Jin, X.; Choo, K.K.R. GPU accelerated full homomorphic encryption cryptosystem, library, and applications for IoT systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 11, 6893–6903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupcová, E.; Drutarovskỳ, M. Number-Theoretic Transform with Constant Time Computation for Embedded Post-Quantum Cryptography. Acta Electrotech. Inform. 2022, 22, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, T. The generic composite residuosity problem. In Black-Box Models of Computation in Cryptology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halevi, S.; Shoup, V. Algorithms in helib. In Advances in Cryptology, Proceedings of the CRYPTO 2014 34th Annual Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 17–21 August 2014; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 554–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouchet, C.V.; Bossuat, J.P.; Troncoso-Pastoriza, J.R.; Hubaux, J.P. Lattigo: A multiparty homomorphic encryption library in go. In Proceedings of the 8th Workshop on Encrypted Computing and Applied Homomorphic Cryptography, Virtual, 15 December 2020; pp. 64–70. Available online: https://homomorphicencryption.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/wahc20_demo_christian.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2025).