A CNN-GRU Model-Based Trajectory Error Predicting and Compensating for a 6-DOF Parallel Robot

Abstract

1. Introduction

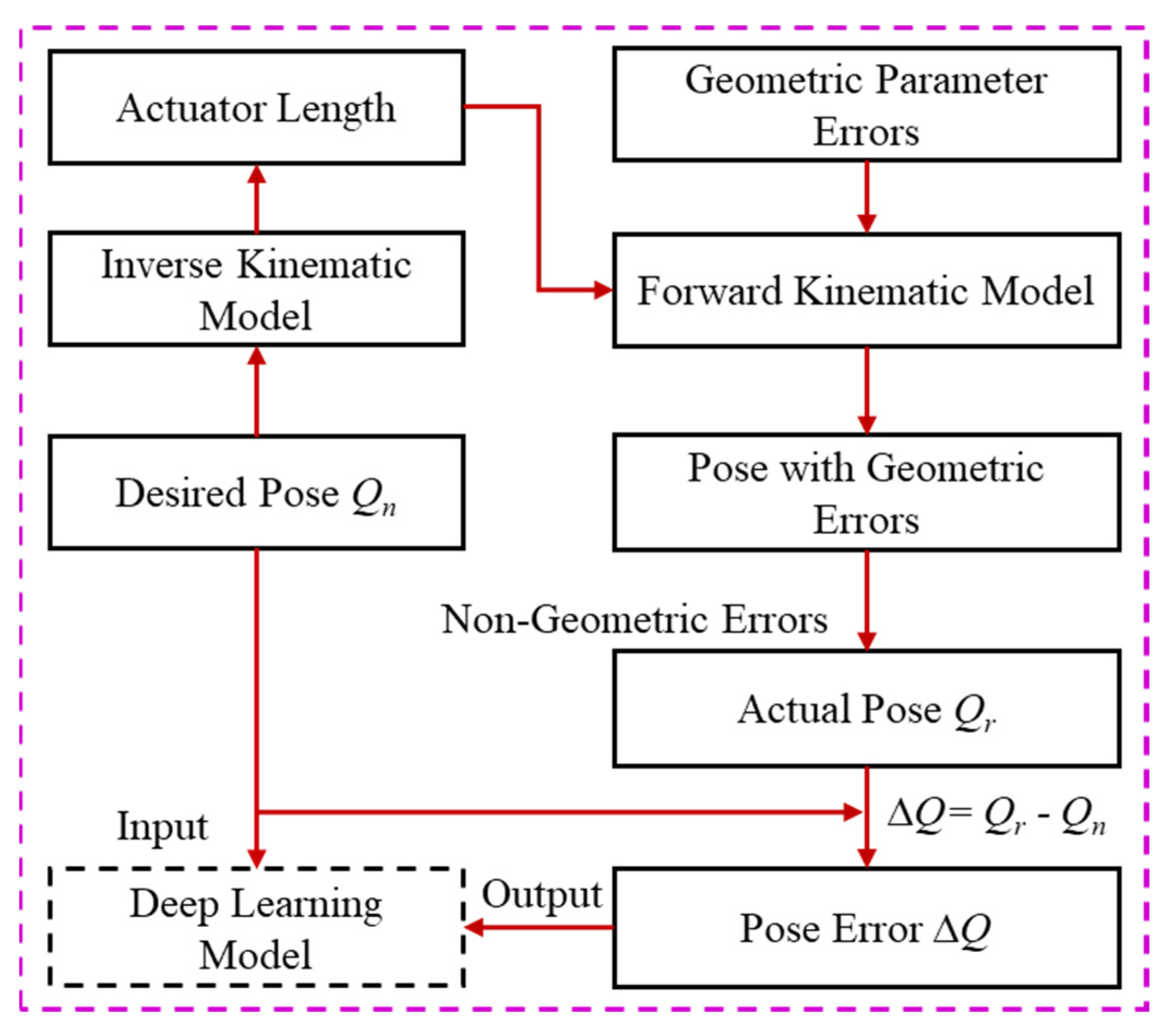

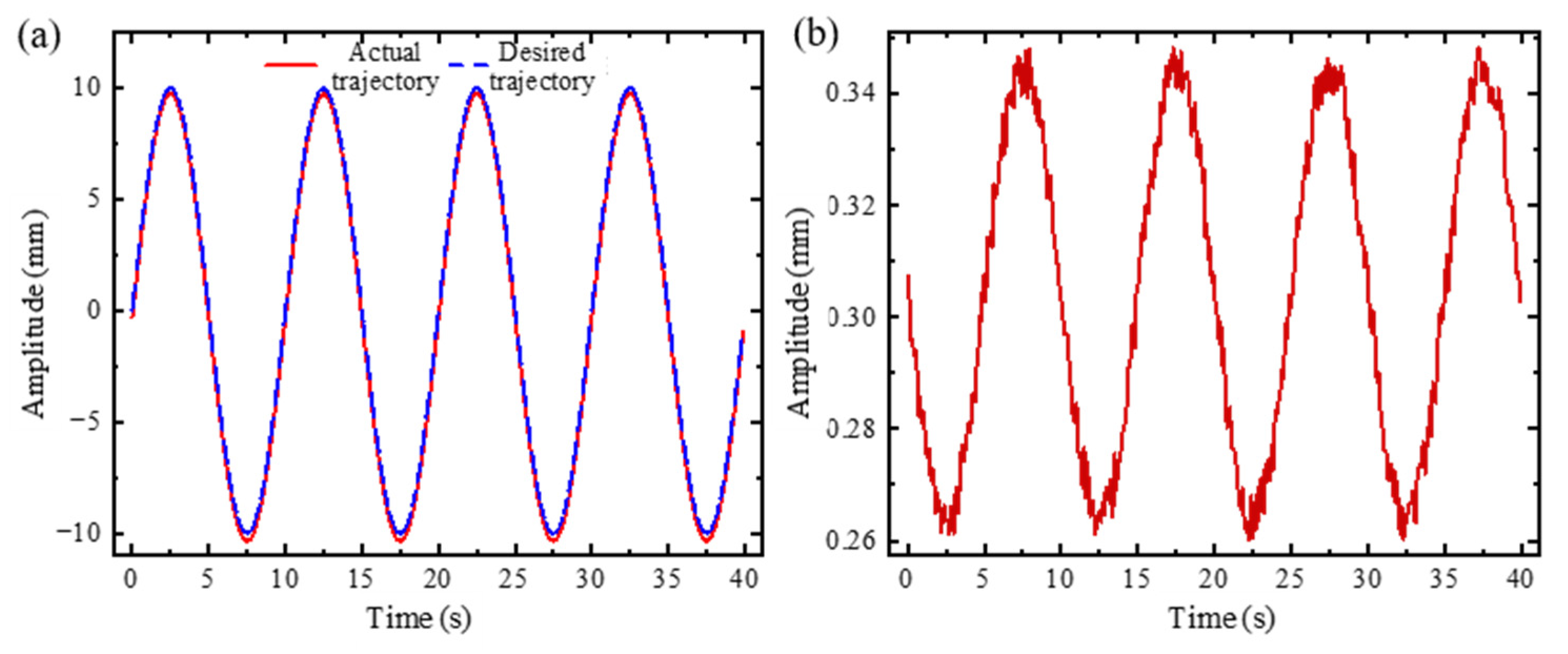

2. Proposed Methodology

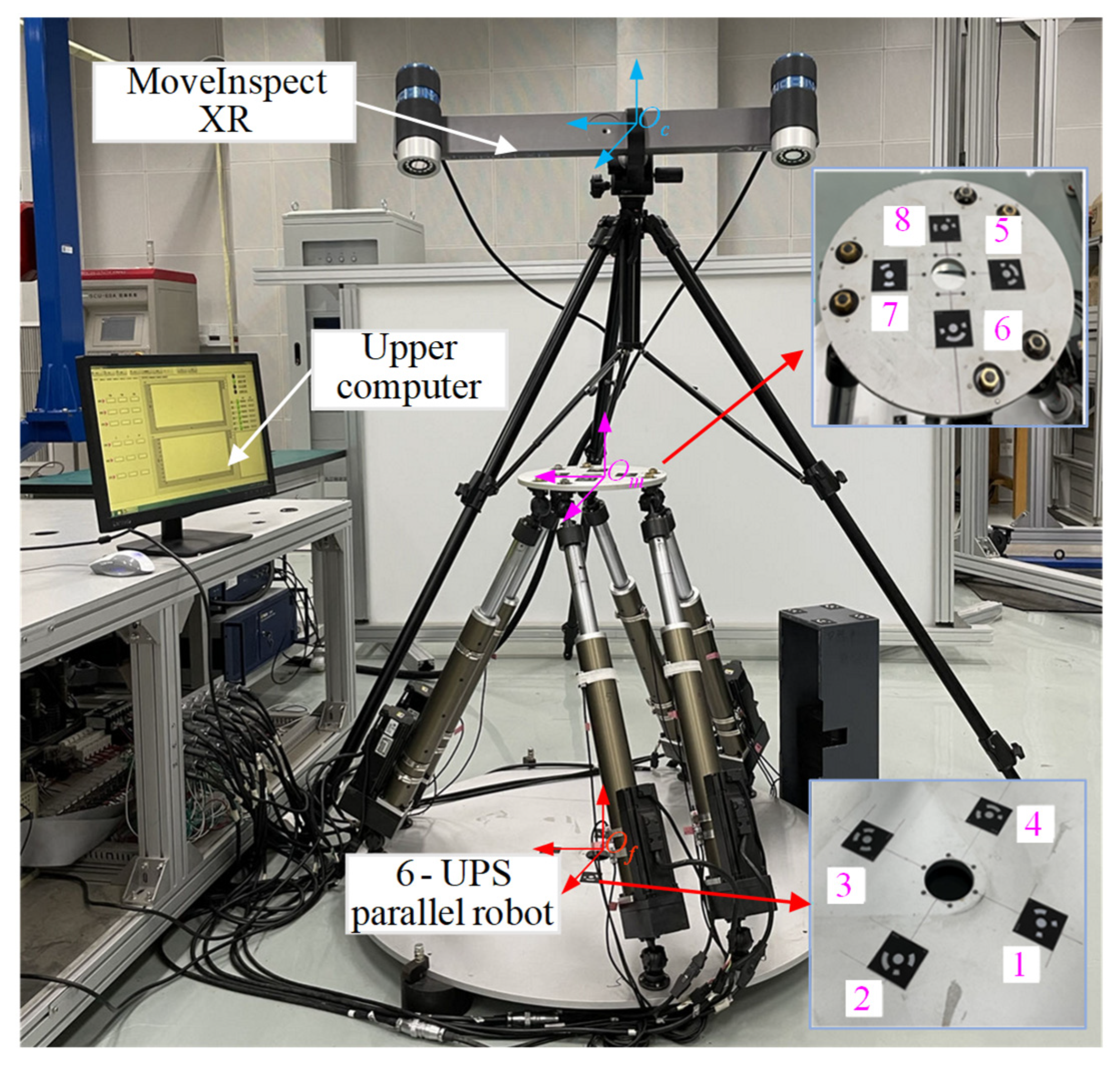

2.1. 6-UPS Parallel Robot and Its Kinematic Model

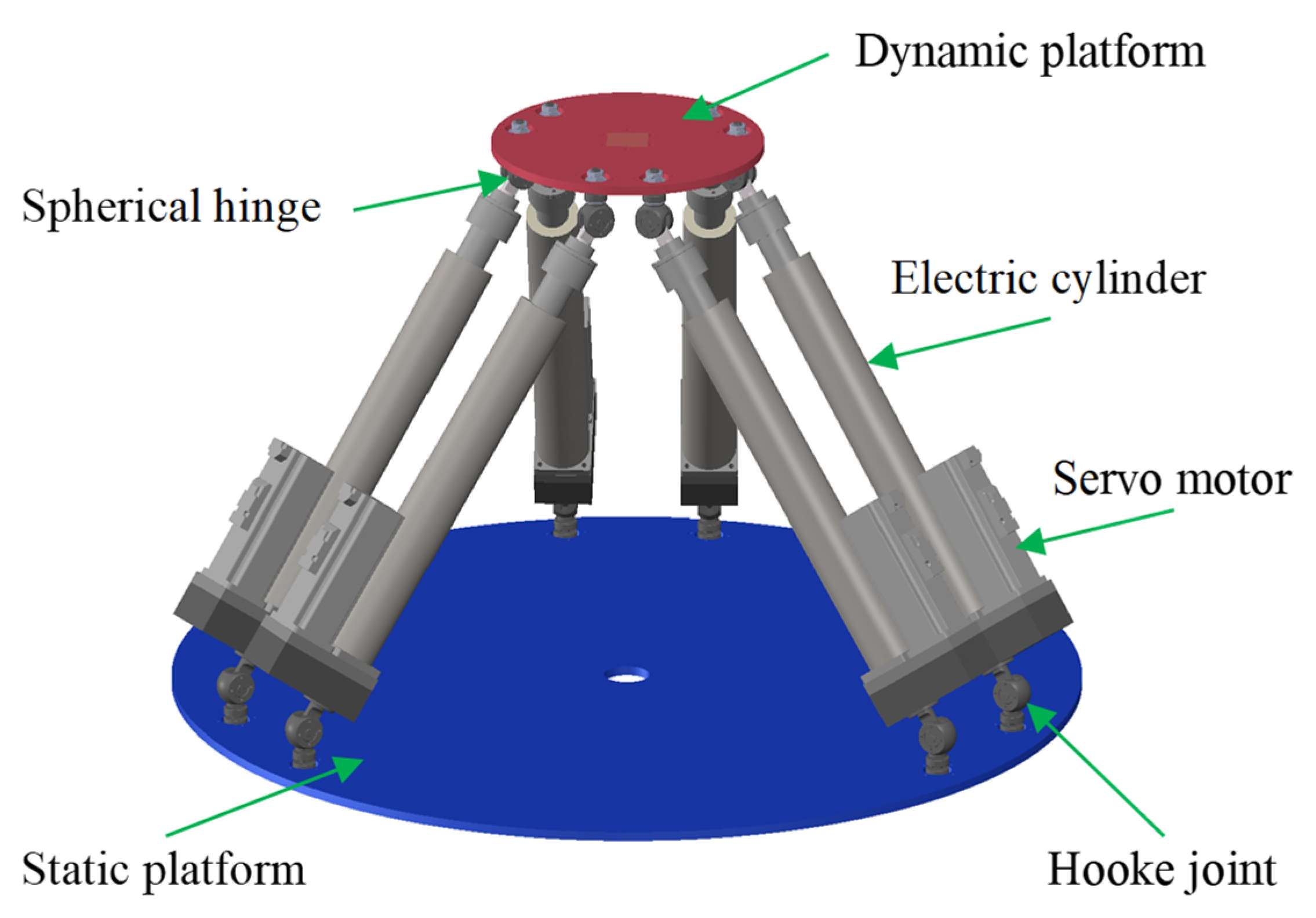

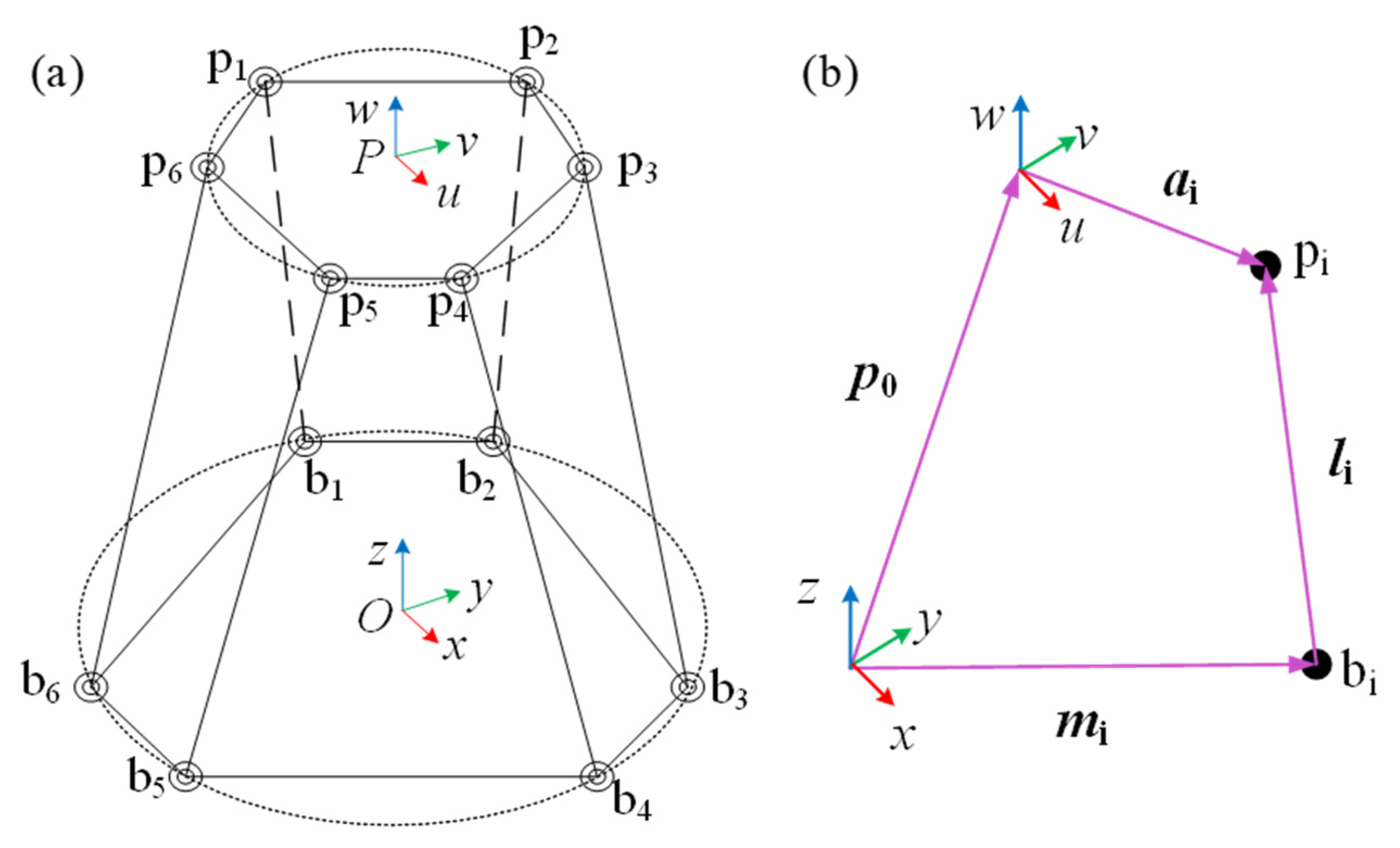

2.1.1. 6-UPS Parallel Robot

2.1.2. Kinematic Analysis of the 6-UPS Parallel Robot

- ai is the position vector of the spherical joint center expressed in the movable platform coordinate system P-uvw.

- R is the rotation matrix of the movable platform coordinate system P-uvw with respect to the fixed-base coordinate system O-xyz. The homogeneous transformation matrix T which combines both rotation and translation, and can be expressed as:

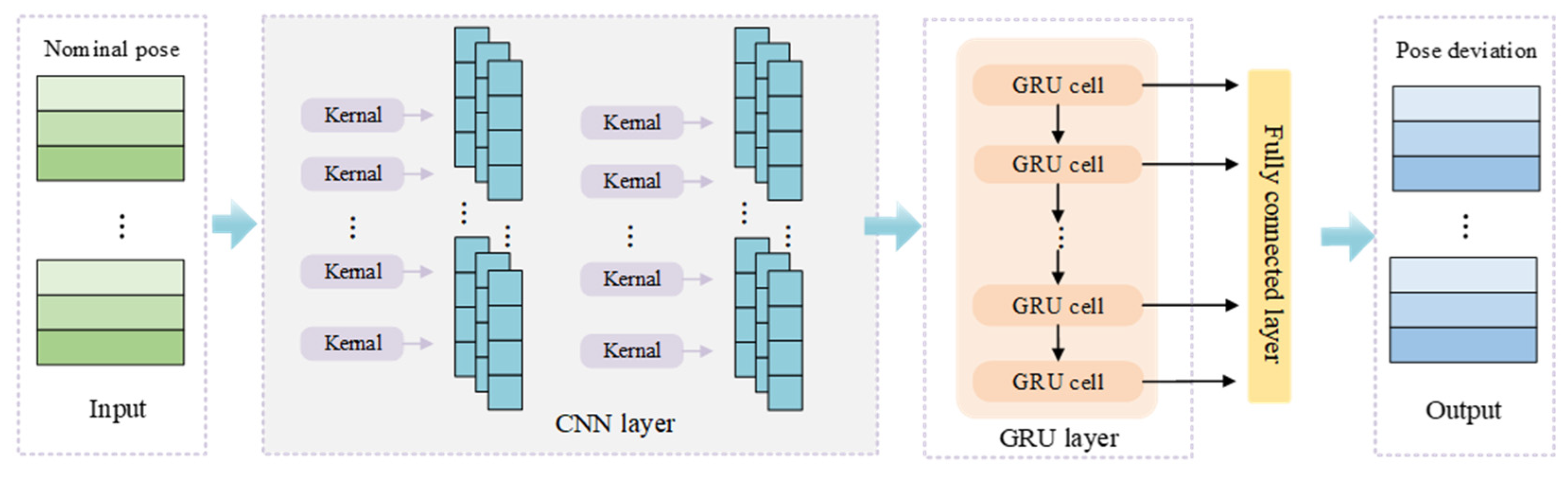

2.2. CNN-GRU Model-Based Trajectory Error Prediction

2.2.1. Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)

- denotes the i-th output in the t-th layer.

- denotes the j-th output in the (t-1)-th layer.

- represents the weight matrix of the convolutional kernel.

- represents the bias of the convolutional kernel.

- ∗ denotes the dot product operation.

- σ represents the activation function.

2.2.2. Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU)

- Sig denotes the Sigmoid activation function.

- ck represents the memory state.

- zk and rk are the update gate and reset gate, respectively.

- Wr, Wz, and W denote the weight matrices.

- xk is the input to the neuron at step k.

- tanh is the hyperbolic tangent activation function.

- yk is the output of the neuron.

- denotes the memory gate.

- signifies the element-wise multiplication operation.

2.2.3. CNN-GRU Model

3. Simulation Validation

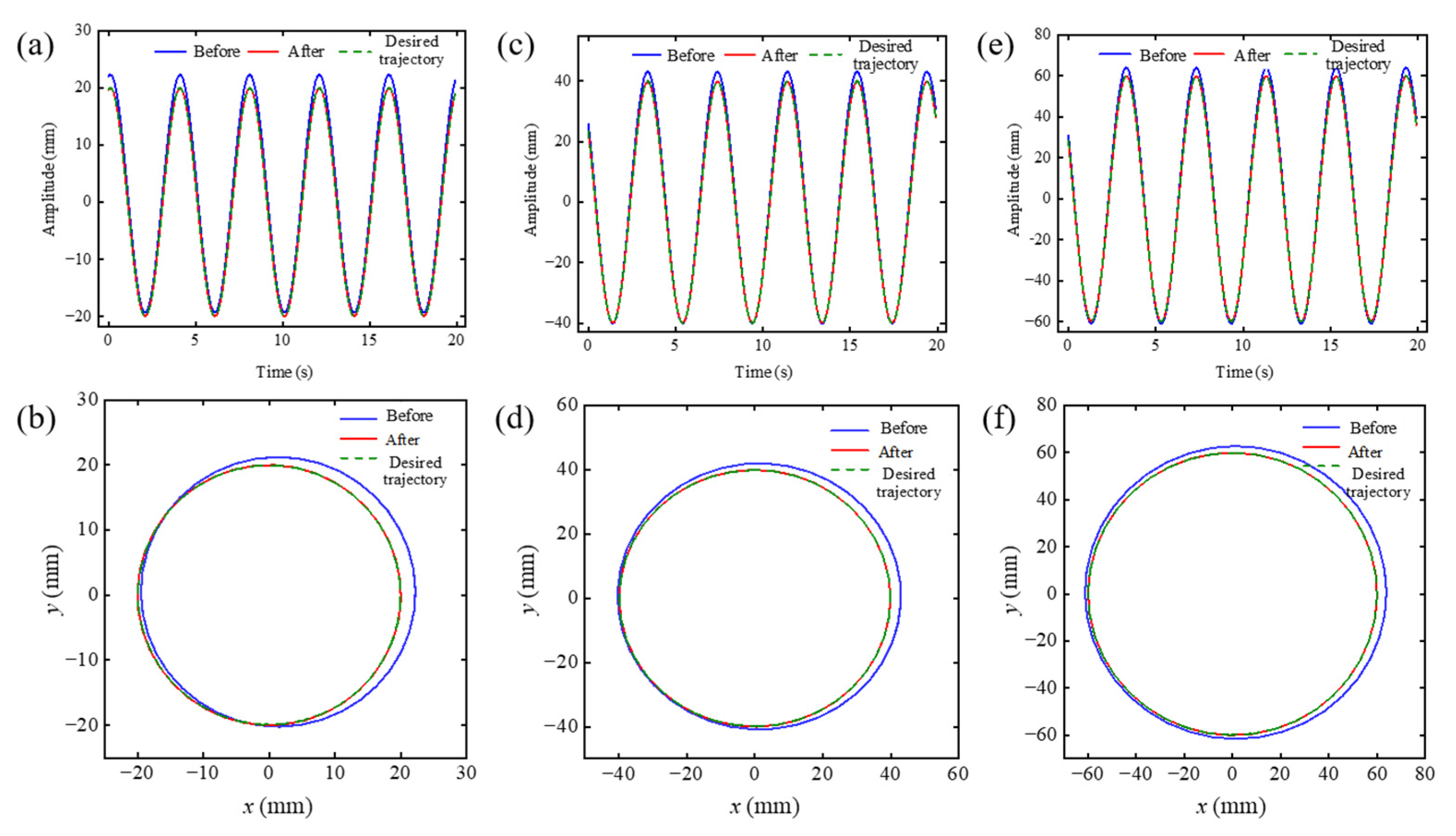

4. Experimental Validation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, L. Kinematics analysis and workspace investigation of a novel 2-DOF parallel manipulator applied in vehicle driving simulator. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2013, 29, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Yao, R. Identification of structure errors of 3-PRS-XY mechanism with Regularization method. Mech. Mach. Theory 2011, 46, 927–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Zhao, D.; Yin, F.; Tian, W.; Chetwynd, D.G. Kinematic calibration of a 6-DOF hybrid robot by considering multicollinearity in the identification Jacobian. Mech. Mach. Theory 2019, 131, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Song, Y.; Dong, G.; Lian, B.; Liu, J. Optimal design of a parallel mechanism with three rotational degrees of freedom. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2012, 28, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lian, B.; Sun, T. Kinematic calibration of a 5-DoF parallel kinematic machine. Precis. Eng. 2016, 45, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; An, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wu, H.; Qin, X.; Eynard, B.; Zhang, Y. Hybrid offline programming method for robotic welding systems. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2022, 73, 102238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, M.K.; Theissen, N.A.; Barrios, A.; Archenti, A. Online compliance error compensation system for industrial manipulators in contact applications. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2022, 76, 102305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimchik, A.; Caro, S.; Pashkevich, A. Optimal pose selection for calibration of planar anthropomorphic manipulators. Precis. Eng. 2015, 40, 214–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saund, B.; De, V.R. High Accuracy Articulated Robots with CNC Control Systems. SAE Int. J. Aerosp. 2013, 6, 780–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Yuan, P.; Wang, T.; Cai, Y.; Xue, L. A Compensation Method for Enhancing Aviation Drilling Robot Accuracy Based on Co-Kriging. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2018, 19, 1133–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Guo, Q.; Yang, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, J. A state-of-the-art review on robotic milling of complex parts with high efficiency and precision. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2023, 79, 102436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, H.; Xu, D.; Feng, X. Stewart parallel manipulator kinematic calibration based on the normalized identification Jacobian choosing measurement configurations. Opt. Precis. Eng. 2020, 28, 1546–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Song, Y.; Lian, B.; Sun, T. Kinematic Calibration of a 6-DoF Parallel Manipulator with Random and Less Measurements. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 7500912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Yang, M.; Liu, Z.; Tao, M.; Cai, C.; Huang, H. Stereo vision-based Kinematic calibration method for the Stewart platforms. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 47059–47069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alici, G.; Jagielski, R.; Ahmet Sekerciolu, Y.; Shirinzadeh, B. Prediction of geometric errors of robot manipulators with Particle Swarm Optimisation method. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2006, 54, 956–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Hua, F.; Tian, W. Robot Positioning Error Compensation Method Based on Deep Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2020 4th International Conference on Control Engineering and Artificial Intelligence, Singapore, 17–19 January 2020; Journal of Physics Conference Series. Volume 1487, p. 012045. [Google Scholar]

- Dolinsky, J.U.; Jenkinson, I.D.; Colquhoun, G.J. Application of genetic programming to the calibration of industrial robots. Comput. Ind. 2007, 58, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Liao, W.; Tian, W. Theory and experiment of industrial robot accuracy compensation method based on spatial interpolation. Jixie Gongcheng Xuebao J. Mech. Eng. 2013, 49, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Tian, W.; Zhang, C.; Hua, F.; Cui, G.; Li, Y. Positioning error compensation of an industrial robot using neural networks and experimental study. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2022, 35, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D. A new pose accuracy compensation method for parallel manipulators based on hybrid artificial neural network. Neural Comput. Appl. 2021, 33, 909–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Liu, Z.; Cai, C.; Yang, M.; Zhang, H.; Fu, L.; Zhang, J. Deep learning-based predicting and compensating method for the pose deviations of parallel robots. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 191, 110179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Z.; Cai, C.; Fu, L.; Yang, M.; Chen, H. Deep learning-based interpretable prediction and compensation method for improving pose accuracy of parallel robots. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 268, 126289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, D. A Platform with Six Degrees of Freedom (Reprinted from vol 180, 1965). Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. 2009, 223, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Liu, Z.; Cai, C.; Tao, M.; Yang, M.; Huang, H. Joint space-based optimal measurement configuration determination method for Stewart platform kinematics calibration. Measurement 2023, 211, 112646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toquica, J.S.; Oliveira, P.S.; Souza, W.S.R.; Motta, J.M.S.T.; Borges, D.L. An analytical and a Deep Learning model for solving the inverse kinematic problem of an industrial parallel robot. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 151, 106682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petraova, I.; Karban, P. Solving evolutionary problems using recurrent neural networks. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2023, 426, 115091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Limb | Δaix | Δaiy | Δaiz | Δbix | Δbiy | Δbiz | Δli |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.5959 | −0.8724 | 0.0221 | −3.2560 | −0.3268 | −1.3285 | −0.1221 |

| 2 | −0.8934 | −0.7948 | 0.7351 | −8.7241 | 0.6229 | 1.7698 | −1.7148 |

| 3 | −0.9396 | −0.2888 | 1.8452 | −1.1413 | −2.7663 | −0.2012 | 1.6943 |

| 4 | 0.5393 | −0.4455 | 1.6012 | 3.4204 | −4.1089 | −0.4453 | 0.8355 |

| 5 | 0.1725 | 0.6275 | 3.1431 | 0.9381 | 3.5874 | 2.5500 | −0.8717 |

| 6 | −0.2835 | −1.0608 | −2.0231 | 1.2270 | 3.2504 | −0.2171 | −2.1385 |

| Hyperparameter | Size/Quantity | Hyperparameter | Value/Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Convolutional Kernel Size | 3 × 1, 3 × 1 | Number of GRU | 6 |

| Number of Convolutional Kernels | 6, 3 | Optimizer | Adam |

| Batch Size | 32 | Loss Function | MAE |

| Number of Training Epochs | 500 | Decay Steps | 400 |

| Initial Learning Rate | 0.01 | Decay Rate | 0.1 |

| Amplitude/mm | CNN-GRU | GRU | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | |

| 20 | 0.0025 | 0.0030 | 0.0030 | 0.0037 |

| 40 | 0.0027 | 0.0032 | 0.0040 | 0.0049 |

| 60 | 0.0028 | 0.0032 | 0.0049 | 0.0060 |

| Amplitude/Radius | Before Compensation (mm) | After Compensation (mm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max. AE | MAE | Max. AE | MAE | |

| Ax = 20 | 0.7822 | 0.6887 | 0.0059 | 0.0024 |

| Ax = 40 | 0.8699 | 0.6888 | 0.0058 | 0.0025 |

| Ax = 60 | 0.9579 | 0.6889 | 0.0064 | 0.0026 |

| rxoy = 20 | 0.4682 | 0.4001 | 0.0316 | 0.0164 |

| rxoy = 40 | 0.5323 | 0.4012 | 0.0545 | 0.0319 |

| rxoy = 60 | 0.5974 | 0.4029 | 0.0814 | 0.0475 |

| Amplitude/mm | CNN-GRU | GRU | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | |

| 20 | 0.0195 | 0.0167 | 0.0172 | 0.0181 |

| 40 | 0.0196 | 0.0159 | 0.0213 | 0.0255 |

| 60 | 0.0359 | 0.0299 | 0.0478 | 0.0451 |

| Amplitude/ Radius | Before Compensation (mm) | After Compensation (mm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max. AE | MAE | Max. AE | MAE | |

| Ax = 20 | 2.3170 | 1.4921 | 0.0730 | 0.0295 |

| Ax = 40 | 3.1579 | 1.5212 | 0.0822 | 0.0400 |

| Ax = 60 | 4.0367 | 1.8820 | 0.0627 | 0.0544 |

| rxoy = 20 | 1.6981 | 0.9757 | 0.0652 | 0.0326 |

| rxoy = 40 | 2.4819 | 1.2051 | 0.0987 | 0.0499 |

| rxoy = 60 | 3.2555 | 1.6180 | 0.0979 | 0.0389 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, Z.; Liu, Z.; Cai, C.; Han, H.; Cao, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, R. A CNN-GRU Model-Based Trajectory Error Predicting and Compensating for a 6-DOF Parallel Robot. Electronics 2025, 14, 4752. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234752

Zhou Z, Liu Z, Cai C, Han H, Cao Y, Li S, Wang R. A CNN-GRU Model-Based Trajectory Error Predicting and Compensating for a 6-DOF Parallel Robot. Electronics. 2025; 14(23):4752. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234752

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Zhenjie, Zhihua Liu, Chenguang Cai, Hongsheng Han, Yufen Cao, Shaohui Li, and Rongyu Wang. 2025. "A CNN-GRU Model-Based Trajectory Error Predicting and Compensating for a 6-DOF Parallel Robot" Electronics 14, no. 23: 4752. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234752

APA StyleZhou, Z., Liu, Z., Cai, C., Han, H., Cao, Y., Li, S., & Wang, R. (2025). A CNN-GRU Model-Based Trajectory Error Predicting and Compensating for a 6-DOF Parallel Robot. Electronics, 14(23), 4752. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234752