Abstract

Problem: Medical image segmentation faces critical challenges in balancing global context modeling and computational efficiency. While conventional neural networks struggle with long-range dependencies, Transformers incur quadratic complexity. Although Mamba-based architectures achieve linear complexity, they lack adaptive mechanisms for heterogeneous medical images and demonstrate insufficient local feature extraction capabilities. Method: We propose Linear Context-Aware Robust Mamba (LCAR–Mamba) to address these dual limitations through adaptive resource allocation and enhanced multi-scale extraction. LCAR–Mamba integrates two synergistic modules: the Context-Aware Linear Mamba Module (CALM) for adaptive global–local fusion, and the Multi-scale Partial Dilated Convolution Module (MSPD) for efficient multi-scale feature refinement. Core Innovations: CALM module implements content-driven resource allocation through four-stage processing: (1) analyzing spatial complexity via gradient and activation statistics, (2) computing allocation weights to dynamically balance global and local processing branches, (3) parallel dual-path processing with linear attention and convolution, and (4) adaptive fusion guided by complexity weights. MSPD module employs statistics-based channel selection and multi-scale partial dilated convolutions to capture features at multiple receptive scales while reducing computational cost. Key Results: On ISIC2017 and ISIC2018 datasets, mIoU improvements of 0.81%/1.44% confirm effectiveness across 2D benchmarks. On the Synapse dataset, LCAR–Mamba achieves 85.56% DSC, outperforming the former best Mamba baseline by 0.48% with 33% fewer parameters. Significance: LCAR–Mamba demonstrates that adaptive resource allocation and statistics-driven multi-scale extraction can address critical limitations in linear-complexity architectures, establishing a promising direction for efficient medical image segmentation.

1. Introduction

With the rapid advancement of deep learning techniques, significant progress has been achieved in medical image segmentation [,,,]. Despite these advances, current segmentation methods face substantial challenges when dealing with complex medical images. Medical images frequently exhibit intricate multi-scale structural characteristics, ranging from pixel-level textural details to organ-level morphological contours. This requires that segmentation models be capable of capturing fine-grained local information while simultaneously modeling global semantic relationships. In addiction, practical clinical applications require segmentation models to robustly handle highly heterogeneous and complex anatomical structures, which requires adaptive modeling capabilities that can effectively address diverse tissue types, lesion characteristics, and contextual variations across different medical images and imaging modalities.

The main approaches to medical image segmentation are based primarily on two technical paradigms: convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [] and vision Transformers (ViTs) []. CNN-based methods, exemplified by U–Net [] and its variants, have achieved excellent segmentation performance through encoder–decoder architectures. Building on this foundation, Attention U–Net [] introduced attention gates to focus on target structures while suppressing irrelevant regions, and U–Net++ [] redesigned skip connections with nested dense skip pathways for improved feature aggregation across multiple scales. To address multi-scale feature extraction, the DeepLab series [] introduced Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) to capture multi-scale contextual information, while PSPNet [] employed pyramid pooling modules for similar purposes. Efficient convolution strategies have emerged to reduce computational overhead while maintaining local feature extraction capabilities. Partial convolutions [] reduce computational cost through selective channel processing, while Ghost convolutions [] generate feature maps through efficient transformations. Similarly, depthwise separable convolutions in MobileNets [] and mixed-scale convolutions in MixNet [] provide efficient alternatives for local feature processing. However, because of the inherently local nature of convolution operations, these models face intrinsic limitations in modeling long-range dependencies. Although researchers have proposed various mitigation strategies such as dilated convolutions and attention mechanisms [,], these approaches often incur a substantial increase in computational complexity.

ViT-based methods leverage self-attention mechanisms to enable global feature modeling, partially alleviating the challenge of modeling long-range dependencies. Vision Transformers [] demonstrated that pure attention mechanisms could achieve competitive performance without convolution operations, addressing CNN limitations in global context modeling. TransUNet [] pioneered the integration of Transformers with U–Net architectures, combining global context with fine-grained localization. Building on this foundation, TransFuse [] proposed parallel CNN–Transformer processing with attention-based fusion, while UTNetV2 [] further explored hybrid strategies to leverage the complementary strengths of both paradigms. Although effective in capturing global dependencies, standard ViTs incur substantial computational costs due to the quadratic complexity of self-attention. To address this challenge, advanced Transformer architectures have been developed specifically for medical imaging. Swin–UNet [] employed hierarchical Swin Transformer blocks with windowed attention to reduce complexity, while MedT [] proposed gated axial attention optimized for medical image characteristics. Similarly, MISSFormer [] introduced an efficient architecture tailored for 2D medical image segmentation through enhanced feature aggregation. To fundamentally overcome the quadratic complexity bottleneck, researchers have explored linear attention mechanisms that approximate self-attention more efficiently. Linear Transformers [] achieve linear complexity through kernel-based attention approximations, while Linformer [] reduces complexity by projecting attention matrices to lower-dimensional spaces. Nevertheless, these approximations often sacrifice modeling capacity, and processing high-resolution medical images remains challenging because of memory constraints even with linear methods.

Recently, state space models (SSMs), such as Mamba [], have attracted considerable attention due to their strong long-sequence modeling capabilities and linear computational complexity. Mamba achieves efficient and expressive feature modeling through an innovative selection mechanism and a hardware-friendly design. Vision Mamba [] extends this architecture to computer vision tasks, demonstrating substantial potential in image analysis. Building on Vision Mamba, numerous architectures have been developed for medical image segmentation. VM–UNet [] integrates Vision Mamba blocks into U–Net frameworks, and H–VMUNet [] proposes hierarchical Vision Mamba architectures with multi-scale processing capabilities. UltraLight VM–UNet [] focuses on parameter efficiency for resource-constrained deployment, Mamba–UNet [] investigates pure Mamba architectures without convolutional components, MambaMIR [] addresses medical image reconstruction and uncertainty estimation using arbitrarily masked Mamba architectures, LocalMamba [] combines local and global Mamba processing to tackle fine-grained structure extraction, and MSVM–UNet [] integrates multi-scale Vision Mamba with U–Net architectures for medical image segmentation.

Despite these advancements, existing advanced architectures, including current Mamba-based methods, still exhibit critical limitations in medical image segmentation. They lack adaptive mechanisms to accommodate varying content complexity and therefore fail to achieve context-aware resource allocation for heterogeneous medical images, in which pathological regions require intensive processing, whereas normal tissues can be handled more efficiently. Moreover, although these methods achieve linear complexity for global modeling, they provide insufficient local feature extraction for fine structures such as organ boundaries and small lesions. This mismatch between existing architectures and the requirements of medical image segmentation—particularly the need for adaptive context-aware processing and enhanced local feature extraction—motivates our LCAR–Mamba architecture, which incorporates novel context-aware linear Mamba modules and multi-scale partial dilated convolution strategies. Recent studies have attempted to mitigate these limitations. For example, Rahman and Marculescu [] proposed a medical image segmentation method with cascaded attention decoding, Azad et al. [] investigated deformable large-kernel attention, and subsequent works such as G–Cascade [] and EMCAD [] further introduced efficient cascaded graph convolutional decoding and multi-scale convolutional attention decoding architectures. Ruan et al. proposed MALUNet [] and EGE–UNet [], which explore lightweight designs with multi-attention and efficient group enhancement strategies for skin lesion segmentation, respectively. However, conventional partial convolution strategies employed in these approaches may overlook important information and thereby adversely affect the segmentation accuracy of fine structures such as boundaries.

To address these issues, this paper proposes a Linear Context-Aware Robust Mamba architecture that integrates two synergistic modules designed to directly tackle the identified limitations. The design philosophy of LCAR-Mamba builds upon recent Vision Mamba architectures for medical imaging [] and draws inspiration from efficient multi-stage feature extraction strategies in medical image super-resolution [], where combining attention mechanisms with lightweight convolutional operations has proven effective for balancing performance and computational cost. LCAR-Mamba comprises two key modules: the Context-Aware Linear Mamba (CALM) module and the Multi-scale Partial Dilated Convolution (MSPD) module. CALM implements a four-stage adaptive processing framework that performs context complexity analysis, adaptive resource allocation, dual-path parallel processing, and intelligent feature fusion, enabling context-aware feature representation and substantially improving model performance. MSPD employs channel statistics analysis, multi-scale parallel processing, and adaptive feature integration to achieve data-driven channel utilization and multi-scale feature fusion while maintaining feature integrity and significantly reducing computational complexity.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- We propose the CALM module, which enables context-aware feature modeling through a four-stage adaptive processing framework, significantly enhancing the feature representation capability and robustness of linear Mamba;

- We design the MSPD module, which utilizes channel statistics analysis and multi-scale feature fusion strategies to substantially reduce computational complexity while maintaining segmentation accuracy;

- We construct the LCAR–Mamba architecture, which seamlessly integrates global and local feature modeling through the collaborative optimization of CALM and MSPD, achieving superior performance in medical image segmentation by combining context-aware adaptive processing with intelligent multi-scale feature extraction;

- We conduct comprehensive experiments on three public medical image segmentation datasets [,,], and the results demonstrate that our method achieves state-of-the-art performance on various segmentation tasks.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Architecture Overview

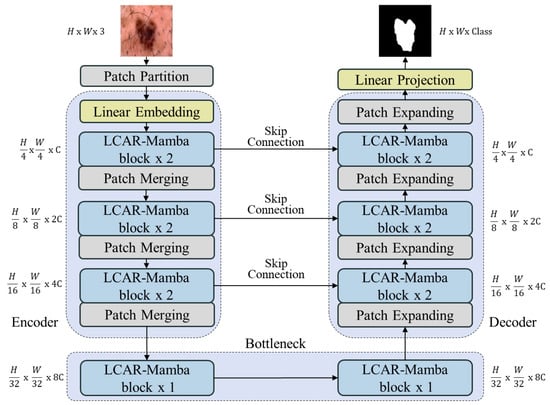

The architecture of the proposed LCAR–Mamba model is illustrated in Figure 1. LCAR–Mamba adopts a four-layer U-shaped structure comprising an encoder, a decoder, and skip connections. The encoder, designed for feature extraction, integrates LCAR–Mamba blocks with patch merging layers to effectively capture image features. The decoder, which incorporates LCAR–Mamba blocks and patch expanding layers, is responsible for reconstructing the segmentation output at the original resolution. Each LCAR–Mamba block consists of two modules: the CALM module and the MSPD module. Skip connections employ additive fusion to seamlessly integrate global and local features, thereby enhancing segmentation accuracy.

Figure 1.

Overall U-shaped architecture with explicit skip connections. The encoder progressively extracts hierarchical features through four stages with spatial downsampling, while the decoder performs symmetric upsampling to restore spatial resolution. Skip connections bridge corresponding encoder–decoder layers to preserve fine-grained details.

The patch embedding layer in LCAR-Mamba converts the input image by dividing it into non-overlapping patches and mapping them into a C-dimensional space (typically ), producing an embedded representation . Before entering the LCAR–Mamba backbone, is then processed by layer normalization to standardize the embedded image. The backbone consists of four distinct stages. In particular, after the output of each of the first three stages, a patch merging layer is applied to reduce the height and width of the feature maps while increasing the channel dimension. We implement [2, 2, 2, 1] LCAR-Mamba blocks in the four stages, with each stage using [C, , , ] channels, respectively.

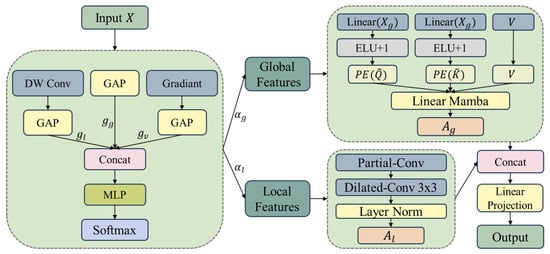

2.2. CALM: Context-Aware Linear Mamba Module

The CALM module addresses both the quadratic computational complexity of traditional self-attention and its insufficient adaptability to heterogeneous content in medical images, as illustrated in Figure 2. Because medical images exhibit pronounced spatial heterogeneity—where pathological regions require intensive processing, whereas normal tissues can be processed more efficiently—traditional uniform processing strategies often lead to suboptimal performance. Building upon the Mamba-Like Linear Attention (MLLA) [] mechanism, CALM implements a context-driven adaptive processing paradigm that combines the efficiency of linear attention with selective feature focusing, thereby enabling effective global context modeling while maintaining linear computational complexity. Unlike VM-UNet [] and MSVM-UNet [], which apply uniform processing to all spatial locations, CALM introduces adaptive resource allocation based on spatial complexity analysis.

Figure 2.

CALM module with parallel complexity assessment and adaptive resource allocation.

2.2.1. Context-Aware Feature Analyzer

The Context-Aware Feature Analyzer serves as a preprocessing component that quantifies input complexity and determines optimal resource allocation strategies. This component addresses the fundamental challenge of medical images that contain regions with varying diagnostic importance and computational requirements, necessitating adaptive processing rather than uniform feature extraction.

The analyzer employs multi-dimensional complexity assessment to comprehensively characterize the input features. It extracts complexity descriptors that capture spatial variation patterns, activation intensity distributions, and gradient characteristics that are essential for medical image analysis.

The complexity evaluation process integrates local spatial patterns through depthwise convolution, global activation statistics via pooling operations, and spatial change magnitudes through gradient analysis:

where , , and represent local, global, and variation features, respectively.

Based on this complexity analysis, adaptive resource allocation weights are generated to determine computational distribution between global and local processing pathways:

where denotes the resource distribution weights.

The soft feature partitioning strategy preserves information integrity while enabling fine-grained resource control and ensuring gradient continuity for end-to-end optimization:

where and represent global and local processing features, respectively, and ⊙ denotes element-wise multiplication.

2.2.2. Adaptive Dual-Path Processor

The Adaptive Dual-Path Processor constitutes the core computational engine that implements specialized processing strategies through complementary branches while maintaining linear computational complexity. This design addresses the limitation of traditional linear attention mechanisms, which often sacrifice expressiveness for computational efficiency—a particularly critical issue in complex medical image analysis that requires both global context understanding and fine-grained detail preservation.

The enhanced global processing branch preserves linear computational complexity while incorporating several key enhancements to improve representation capability. The query and key matrices are jointly generated under a non-negativity constraint:

where and denote the query and key matrices with non-negativity constraints, and .

The global attention mechanism integrates positional embedding to capture spatial relationships while maintaining linear complexity:

where denotes linear attention and represents position embedding.

The local processing branch employs convolutional operations optimized for fine-grained feature extraction:

where represents the combined partial and dilated convolution operations.

The dual-path features are fused using an adaptive, weight-guided strategy that leverages the learned resource allocation weights to ensure consistency between the feature allocation and fusion stages:

where and are the resource distribution weights obtained from the context complexity analysis, ensuring that the fusion process directly reflects the adaptive resource allocation strategy determined by input complexity. This differs from MSVM-UNet [], which learns fusion weights independently without considering spatial complexity.

2.2.3. CALM Algorithm

Algorithm 1 presents the computational procedure of the CALM module, which implements adaptive feature processing through four sequential stages: context complexity analysis (Lines 2–5), adaptive resource allocation (Lines 7–9), dual-path parallel processing (Lines 11–14), and intelligent feature fusion (Line 16).

| Algorithm 1 CALM module |

|

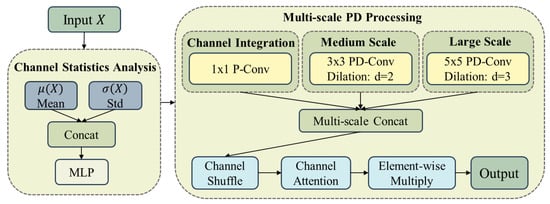

2.3. MSPD: Multi-Scale Partial Dilated Convolution Module

The MSPD module is composed of partial convolution [] and dilated convolution [] components and integrates adaptive channel selection mechanisms, as illustrated in Figure 3. Unlike traditional approaches that employ random channel selection, MSPD performs data-driven channel selection through feature-aware analysis, enabling the model to recognize multi-scale structures in images while preserving fine-grained details. In addition, partial convolution is utilized to reduce computational overhead, thus achieving substantial computational savings while maintaining segmentation accuracy.

Figure 3.

MSPD module with statistical guidance and multi-scale processing.

2.3.1. Channel Statistics Analysis

The feature-aware analysis component serves as the perceptual front end of MSPD, characterizing the intrinsic properties of input features and guiding subsequent partial convolution operations. This component replaces random selection strategies with feature-aware estimation of channel importance, enabling more efficient partial convolution processing.

For input feature maps X, first- and second-order moments are computed to represent channel-wise activation intensity and spatial complexity:

where and denote channel-wise mean and standard deviation operations, respectively.

2.3.2. Multi-Scale PD Processing

The multi-scale PD processing module implements multi-scale depthwise processing with optimized partial convolution configurations. Three parallel processing branches capture different receptive field characteristics: partial convolution for channel integration, partial dilated convolution for medium-scale relationships, and partial dilated convolution for large-scale context:

where denotes partial convolution with kernel size k, represents partial dilated convolution, and d indicates dilation rate.

Multi-scale features are integrated through concatenation and enhanced with channel attention:

where denotes channel shuffling and represents the channel attention mechanism.

2.3.3. MSPD Algorithm

Algorithm 2 outlines the computational flow of the MSPD module, which performs statistics-based channel analysis (Lines 2–4), extracts features through three parallel multi-scale branches (Lines 6–8), and integrates them via channel attention mechanism (Lines 10–13).

| Algorithm 2 MSPD module |

|

2.4. Loss Function

The proposed LCAR–Mamba model employs task-specific composite loss functions optimized for different segmentation scenarios: a BCE–Dice combination for binary skin lesion segmentation and a CE–Dice combination for multi-organ segmentation.

2.4.1. Binary Segmentation Loss for ISIC Datasets

For skin lesion segmentation on ISIC2017 and ISIC2018 datasets, we adopt a balanced combination of Binary Cross-Entropy (BCE) loss and Dice loss to jointly optimize pixel-level accuracy and region-level overlap:

where , assigning equal importance to both objectives.

2.4.2. Multi-Class Segmentation Loss for Synapse Dataset

For multi-organ segmentation on the Synapse dataset, we employ a weighted combination of Cross-Entropy (CE) loss and multi-class Dice loss:

where and control the relative contributions of pixel-level and region-level objectives. The asymmetric weighting emphasizes region-level consistency, which is particularly important for handling class imbalance in multi-organ segmentation. Following the loss computation methodology of VM–UNet [] and MSVM–UNet [], we adopt the same implementation where both CE loss and Dice loss are computed across all classes (including background class 0) to maintain consistent gradient flow during training.

2.5. Generative AI Assistance

Claude 3.5 Sonnet (Anthropic, October 2024) was used to refine English expression and optimize paragraph structure during manuscript preparation. All scientific content, data analysis, and conclusions were independently developed by the authors, who take full responsibility for the manuscript content.

3. Experiments and Results

3.1. Datasets

Our method was evaluated on three public datasets: ISIC2017, ISIC2018 and Synapse.

3.1.1. ISIC2017 and ISIC2018

The ISIC2017 [] and ISIC2018 [] datasets are publicly available skin lesion segmentation benchmarks, containing 2150 and 2694 images, respectively. Following the previous work [] on ISIC2017 and ISIC2018, we used a 7:3 train–test split. For ISIC2017, this resulted in 1500 training images and 650 test images. For ISIC2018, we obtained 1886 training images and 808 test images. All images were resized to . The experiments used fixed random seed = 42. Segmentation performance was evaluated using five metrics: mean Intersection over Union (mIoU), Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC), Sensitivity (SE), Specificity (SP) and Accuracy (ACC).

3.1.2. Synapse

The Synapse dataset [] is a publicly available multi-organ segmentation dataset comprising 30 abdominal CT cases with 3779 axial images across eight organs. Following [], 18 cases were used for training and 12 for testing. Performance was evaluated using the Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) and 95% Hausdorff Distance (HD95).

We employ a 2D slice-wise approach. Each 3D CT volume is decomposed into axial slices and resized from to pixels using bicubic interpolation for images and nearest-neighbor interpolation for masks. The dataset contains volumes with voxel spacing ranging from ([0.54 0.54] × [0.98 0.98] × [2.5 5.0]) mm3. Following standard evaluation protocols, Hausdorff Distance 95 (HD95) was computed using a normalized spacing of 1.0 mm for fair comparison with baseline methods.

3.2. Implementation Details

All experiments were conducted using the PyTorch 2.2.2 framework on an NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU. We adopted the AdamW optimizer with an initial learning rate of , weight decay of , and cosine annealing learning rate scheduler. The batch size was set to 48 and the network was trained for up to 300 epochs.

Inference and Post-processing. For ISIC datasets, predictions were obtained by applying a threshold of 0.5 to the sigmoid output. For Synapse, we used argmax over the softmax outputs to generate per-pixel class predictions. No additional post-processing techniques (e.g., conditional random fields, test-time augmentation, or largest connected component filtering) were employed in our experiments, ensuring that all reported results reflect the direct model output.

Baseline Implementation. To ensure fair comparison, all baseline methods were trained under identical experimental settings to LCAR-Mamba, including the same input resolution (256 × 256 for ISIC, 224 × 224 for Synapse), training configuration (300 epochs, AdamW optimizer with learning rate , cosine annealing scheduler), and data augmentation strategies.

Data Augmentation. During training, the following augmentations were applied:

- ISIC datasets: Random horizontal flip (), random vertical flip (), and random rotation (0°–360°)

- Synapse dataset: Random rotation by 90° increments (0°, 90°, 180°, and 270°) with and random flip along vertical or horizontal axis with

3.3. Comparisons with State of the Art

To demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed LCAR–Mamba, we conducted extensive comparisons with state-of-the-art approaches on three publicly available medical image segmentation datasets.

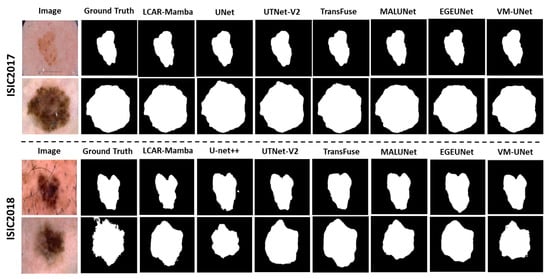

Skin Lesion Segmentation. Table 1 and Table 2 report the quantitative results on the ISIC2017 and ISIC2018 datasets, respectively. On ISIC2017, LCAR–Mamba achieves the highest mIoU of 80.79% and DSC of 89.42%, outperforming the Mamba-based model VM–UNet by 0.62% in mIoU and 0.52% in DSC. Notably, our method yields substantial gains in sensitivity, reaching 89.54%, which is 1.95% higher than VM–UNet (87.59%). On ISIC2018, LCAR–Mamba achieving an mIoU of 81.68% and a DSC of 89.93%, surpassing VM–UNet by 1.25% and 0.89%, respectively. Moreover, LCAR–Mamba attains the highest specificity of 97.29%, representing a 1.10% improvement over VM–UNet (96.19%). These consistent improvements on both skin lesion datasets highlight the effectiveness of combining context-aware adaptive processing through the CALM module with enhanced local feature extraction capabilities through the MSPD module. The qualitative comparisons shown in Figure 4 further demonstrate that LCAR–Mamba produces more precise boundary delineations and better captures fine-grained lesion details compared to existing methods.

Table 1.

Comparative experimental results on the ISIC2017 dataset. Bold values indicate the best performance. ↑ indicate metrics where higher values represent better performance.

Table 2.

Comparative experimental results on the ISIC2018 dataset. Bold values indicate the best performance. ↑ indicate metrics where higher values represent better performance.

Figure 4.

Quantitative comparison of our LCAR–Mamba framework against other baselines on the ISIC2017 and ISIC2018 datasets.

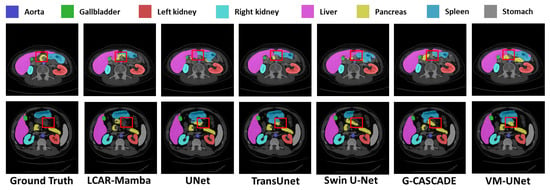

Multi-Organ Segmentation. Table 3 demonstrates the performance of LCAR–Mamba on the Synapse multi-organ segmentation dataset. LCAR–Mamba achieves the highest overall DSC score of 85.56% and an HD95 value of 13.15 mm, reflecting strong segmentation accuracy and boundary precision. Compared to its closest competitor MSVM–UNet, LCAR–Mamba improves DSC by 0.48% and HD95 by 1.28 mm. Compared to the Mamba-based baseline VM–UNet, LCAR–Mamba yields substantial gains of 2.90% in DSC and 2.75 mm in HD95, highlighting the advantages of the CALM and MSPD modules over conventional Mamba architectures. Compared to pure Transformer-based methods such as Swin–UNet and TransUNet, LCAR–Mamba outperforms them by 6.15% and 8.48% in DSC, along with substantial HD95 improvements of 8.13 mm and 30.74 mm, respectively, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed hybrid architecture. LCAR–Mamba also achieves competitive performance across most anatomical structures. In particular, it achieves the highest DSC scores for challenging organs, including the aorta (89.52%), gallbladder (76.43%), left kidney (88.75%), liver (96.21%) and stomach (88.15%). Even for small and irregularly shaped organs such as the pancreas, LCAR–Mamba maintains competitive performance with a DSC of 67.87%, comparable to state-of-the-art methods. Qualitative comparisons in Figure 5 further show that LCAR–Mamba produces more precise organ boundaries and better preserves fine anatomical structures.

Table 3.

Comparative experimental results on the Synapse dataset. Bold values indicate the best performance. ↑ and ↓ indicate metrics where higher and lower values represent better performance, respectively.

Figure 5.

Quantitative comparison of our LCAR–Mamba framework against other baselines on the Synapse dataset. Red boxes highlight regions where LCAR-Mamba demonstrates superior organ segmentation accuracy and better discrimination between organ and non–organ tissues.

3.4. Statistical Significance Analysis

To rigorously assess the reliability of our results, we conducted statistical significance testing using paired t-tests across 3 independent runs with different random seeds (42, 123, and 456). Table 4 summarizes the statistical analysis comparing LCAR–Mamba with VM-UNet on ISIC2017 and ISIC2018 datasets.

Table 4.

Statistical significance analysis. Mean difference and p-values from paired t-tests (3 seeds, df = 2).

All improvements achieved by LCAR-Mamba are statistically significant at the level (p < 0.05), confirming that the observed performance gains are not due to random variation. The relatively small standard deviations (0.12–0.21%) across different seeds indicate stable and reproducible training dynamics.

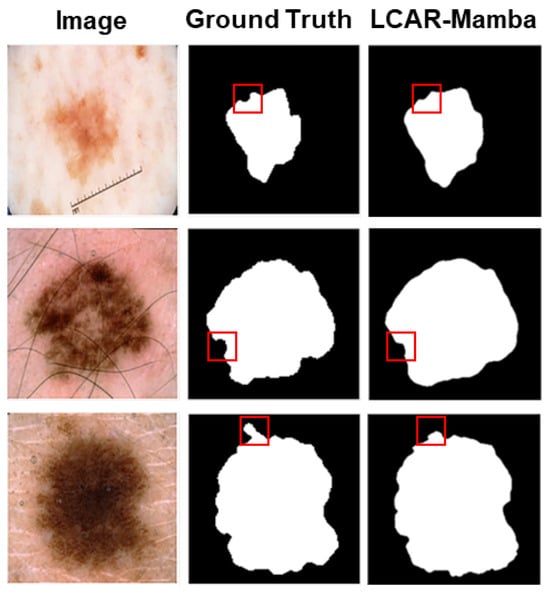

3.5. Failure Case Analysis

Figure 6 shows representative failure cases on ISIC2017. LCAR–Mamba struggles with fuzzy boundaries in low-contrast regions (Row 1), hair occlusion artifacts (Row 2), and pigmentation heterogeneity (Row 3). These cases reveal ongoing challenges in boundary refinement and noise robustness.

Figure 6.

Representative failure cases of LCAR–Mamba on ISIC2017 dataset. Red boxes highlight problematic regions: (Row 1) fuzzy boundaries with low contrast, (Row 2) hair occlusion interference, (Row 3) pigmentation heterogeneity with lighter central regions.

3.6. Ablation Studies

To validate the effectiveness of each component in the LCAR–Mamba architecture, we conducted comprehensive ablation studies on the Synapse dataset. The experiments are organized into two levels: module-level ablation and component-level ablation.

3.6.1. Module-Level Ablation

We first conduct module-level ablation experiments to assess the contribution of the CALM and MSPD modules. Table 5 summarizes the effect of each module on model performance. Incorporating the CALM module improves DSC from 82.66% to 84.12% while reducing the number of parameters from 44.75 M to 38.21 M, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed context–aware linear Mamba. Introducing the MSPD module substantially reduces the computational cost while maintaining high accuracy (83.87%), with the parameter count further reduced to 31.45 M. The complete LCAR–Mamba model achieves the best overall performance, reaching a DSC of 85.56% with only 29.83 M parameters, corresponding to an approximate 33% reduction in parameters compared to the baseline.

Table 5.

Module-level ablation study results on the Synapse dataset. Bold values indicate the best performance. ↑ and ↓ indicate metrics where higher and lower values represent better performance, respectively.

3.6.2. MSPD Component-Level Ablation

We further analyze the contribution of each component in the MSPD module. Table 6 highlights several key observations regarding the MSPD design. The statistics-based channel selection strategy is more effective than random selection, improving DSC from 82.91% to 83.34%. Multi-scale processing further enhances feature representation, with the three-scale configuration achieving the best trade-off between performance and complexity, reaching 83.87% DSC and yielding a 1.21% improvement over the baseline model. However, extending to four scales introduces parameter redundancy with only marginal performance gains, indicating that three scales constitute the optimal configuration for this architecture.

Table 6.

MSPD component-level ablation study. CSA: Channel Statistics Analysis; MSP: Multi-Scale Processing. Bold values indicate the best performance. ↑ and ↓ indicate metrics where higher and lower values represent better performance, respectively.

3.6.3. CALM Component-Level Ablation

We systematically analyze the contribution of each functional component in the CALM module. Table 7 presents controlled ablation experiments isolating the complexity analysis mechanism and the adaptive fusion strategy.

Table 7.

CALM component-level ablation study on the Synapse dataset. Bold values indicate the best performance. ↑ and ↓ indicate metrics where higher and lower values represent better performance, respectively.

The complexity analysis mechanism proves essential for content-aware processing. Without complexity–driven resource allocation (using uniform weights throughout), performance improves to 83.45% DSC, representing a 0.79% gain over the baseline but 0.67% below full CALM. This confirms that analyzing spatial heterogeneity via the Context-Aware Feature Analyzer is crucial for optimal resource distribution.

The adaptive fusion strategy also contributes independently. When complexity descriptors guide feature partitioning but fusion uses fixed weights, the model achieves 83.68% DSC—-a 1.02% improvement over the baseline yet 0.44% below full CALM. This demonstrates that while complexity-aware partitioning provides benefits, adaptive fusion in the Dual-Path Processor is necessary for optimal feature integration.

4. Conclusions

This paper introduces LCAR–Mamba, a hybrid architecture that addresses key limitations of current medical image segmentation methods through two synergistic components: the CALM module and the MSPD module. Extensive experiments on three public datasets show consistent and substantial performance gains across diverse imaging modalities and anatomical structures. The CALM module addresses the fundamental challenge of adaptive resource allocation in heterogeneous medical images, enabling context-aware feature modeling with linear computational complexity, as evidenced by a 1.46% DSC increase and a 14.6% reduction in parameters on the Synapse dataset. The MSPD module further demonstrates that intelligent channel selection and multi-scale processing can significantly enhance feature representations while reducing computational overhead, with the statistics-based selection strategy improving DSC by 0.43% compared with random selection.

Compared with pure CNN architectures such as U–Net [], LCAR–Mamba achieves a 10.51% DSC improvement on Synapse by more effectively modeling long-range dependencies, while surpassing Transformer-based methods [,] with approximately 33% fewer parameters. In addition, the 2.90% DSC improvement over existing Mamba-based methods [] validates the effectiveness of the proposed context-aware adaptive processing and multi-scale feature extraction mechanisms. These results underscore both the superior performance and parameter efficiency of LCAR–Mamba across different architectural paradigms.

Despite its strong empirical performance, several promising research directions remain. Future work includes extending the framework to 3D volumetric segmentation, enhancing small lesion detection (e.g., pancreas segmentation at 67.87% DSC), exploring semi-supervised or weakly supervised learning settings, and investigating dynamic network adaptation strategies for real-time clinical deployment. In summary, LCAR–Mamba integrates global context modeling with local feature extraction through adaptive processing mechanisms, achieving state-of-the-art performance across diverse medical segmentation tasks, with notable gains in accuracy (85.56% DSC on Synapse) and boundary precision (13.15 mm HD95), and offering a robust solution for practical clinical applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.M.; methodology, X.M.; investigation, X.M.; resources, G.L.; data curation, X.M.; writing—original draft preparation, X.M.; writing—review and editing, X.M. and G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the NSFC fund NO. 62572145.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because all experiments were conducted using publicly available datasets (ISIC2017, ISIC2018, and Synapse) that have been previously approved and anonymized by their respective institutions. No new human subjects were recruited for this research.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study used de-identified data from publicly available datasets and did not involve direct interaction with human subjects.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the use of Claude 3.5 Sonnet (Anthropic, October 2024) for English language editing and paragraph structure refinement during manuscript preparation. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI), Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Q.; Wang, M. Swin-UNet: UNet-Like Pure Transformer for Medical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 205–218. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Z.; Fedorov, V.V.; Fu, X.; Cheng, E.; Macleod, R.; Zhao, J. Fully Automatic Left Atrium Segmentation from Late Gadolinium Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging Using a Dual Fully Convolutional Neural Network. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2018, 37, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valanarasu, J.M.J.; Patel, V.M. UNeXt: MLP-Based Rapid Medical Image Segmentation Network. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI), Singapore, 18–22 September 2022; pp. 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-Based Learning Applied to Document Recognition. Proc. IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Virtual Event, Austria, 3–7 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Oktay, O.; Schlemper, J.; Folgoc, L.L.; Lee, M.; Heinrich, M.; Misawa, K.; Mori, K.; McDonagh, S.; Hammerla, N.Y.; Kainz, B.; et al. Attention U-Net: Learning Where to Look for the Pancreas. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI), Granada, Spain, 16–20 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Rahman Siddiquee, M.M.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. UNet++: A Nested U-Net Architecture for Medical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis and Multimodal Learning for Clinical Decision Support (DLMIA/ML-CDS), Granada, Spain, 20 September 2018; pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.C.; Papandreou, G.; Kokkinos, I.; Murphy, K.; Yuille, A.L. DeepLab: Semantic Image Segmentation with Deep Convolutional Nets, Atrous Convolution, and Fully Connected CRFs. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 40, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Shi, J.; Qi, X.; Wang, X.; Jia, J. Pyramid Scene Parsing Network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2881–2890. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Kao, S.H.; He, H.; Zhuo, W.; Wen, S.; Lee, C.H.; Chan, S.H.G. Run, Don’t Walk: Chasing Higher FLOPS for Faster Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 12021–12031. [Google Scholar]

- Han, K.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Q.; Guo, J.; Xu, C.; Xu, C. GhostNet: More Features from Cheap Operations. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 1580–1589. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. MobileNets: Efficient Convolutional Neural Networks for Mobile Vision Applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. MixConv: Mixed Depthwise Convolutional Kernels. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.09595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Koltun, V. Multi-Scale Context Aggregation by Dilated Convolutions. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), San Juan, Puerto Rico, 2–4 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Lu, Y.; Yu, Q.; Luo, X.; Adeli, E.; Wang, Y.; Lu, L.; Yuille, A.L.; Zhou, Y. TransUNet: Transformers Make Strong Encoders for Medical Image Segmentation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.04306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Hu, Q. TransFuse: Fusing Transformers and CNNs for Medical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI), Strasbourg, France, 27 September–1 October 2021; pp. 14–24. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Zhou, M.; Metaxas, D.N. UTNet: A Hybrid Transformer Architecture for Medical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI), Strasbourg, France, 27 September–1 October 2021; pp. 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Valanarasu, J.M.J.; Oza, P.; Hacihaliloglu, I.; Patel, V.M. Medical Transformer: Gated Axial-Attention for Medical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI), Strasbourg, France, 27 September–1 October 2021; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 36–46. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Deng, Z.; Li, D.; Yuan, X.; Fu, Y. MISSFormer: An Effective Transformer for 2D Medical Image Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2023, 42, 1484–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katharopoulos, A.; Vyas, A.; Pappas, N.; Fleuret, F. Transformers are RNNs: Fast Autoregressive Transformers with Linear Attention. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Virtual Event, 13–18 July 2020; Volume 119, pp. 5156–5165. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Li, B.Z.; Khabsa, M.; Fang, H.; Ma, H. Linformer: Self-Attention with Linear Complexity. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.04768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, A.; Dao, T. Mamba: Linear-Time Sequence Modeling with Selective State Spaces. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.00752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Liao, B.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Wang, X. Vision Mamba: Efficient Visual Representation Learning with Bidirectional State Space Model. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Vienna, Austria, 21–27 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, J.; Li, J.; Xiang, S. VM-UNet: Vision Mamba UNet for Medical Image Segmentation. ACM Trans. Multimedia Comput. Commun. Appl. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Liu, Y.; Liang, P.; Chang, Q. H-VMUNet: High-Order Vision Mamba UNet for Medical Image Segmentation. Neurocomputing 2025, 615, 129447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Liu, Y.; Ning, G.; Liang, P.; Chang, Q. UltraLight VM-UNet: Parallel Vision Mamba Significantly Reduces Parameters for Skin Lesion Segmentation. Patterns 2025, 6, 101298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zheng, J.Q.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, G.; Li, L. Mamba-UNet: UNet-Like Pure Visual Mamba for Medical Image Segmentation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.05079. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Yang, L.; Wang, F.; Nan, Y.; Aviles-Rivero, A.I.; Schönlieb, C.B.; Zhang, D.; Yang, G. MambaMIR: An Arbitrary-Masked Mamba for Joint Medical Image Reconstruction and Uncertainty Estimation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.18451. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T.; Pei, X.; You, S.; Wang, F.; Qian, C.; Xu, C. LocalMamba: Visual State Space Model with Windowed Selective Scan. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 12–22. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Yu, L.; Min, S.; Wang, S. MSVM-UNet: Multi-Scale Vision Mamba UNet for Medical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), Lisbon, Portugal, 3–6 December 2024; pp. 3111–3114. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.M.; Marculescu, R. Medical Image Segmentation via Cascaded Attention Decoding. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 2–7 January 2023; pp. 6222–6231. [Google Scholar]

- Azad, R.; Niggemeier, L.; Hüttemann, M.; Kazerouni, A.; Aghdam, E.K.; Velichko, Y.; Bagci, U.; Merhof, D. Beyond Self-Attention: Deformable Large Kernel Attention for Medical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2024; pp. 1287–1297. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.M.; Marculescu, R. G-Cascade: Efficient Cascaded Graph Convolutional Decoding for 2D Medical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2024; pp. 7728–7737. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.M.; Munir, M.; Marculescu, R. EMCAD: Efficient Multi-Scale Convolutional Attention Decoding for Medical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 11769–11779. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, J.; Xiang, S.; Xie, M.; Liu, T.; Fu, Y. MALUNet: A Multi-Attention and Light-Weight UNet for Skin Lesion Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 6–8 December 2022; pp. 1150–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, J.; Xie, M.; Gao, J.; Liu, T.; Fu, Y. EGE-UNet: An Efficient Group Enhanced UNet for Skin Lesion Segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–12 October 2023; pp. 481–490. [Google Scholar]

- Hayat, M. Endoscopic Image Super-Resolution Algorithm Using Edge and Disparity Awareness. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Electrical Engineering, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codella, N.; Rotemberg, V.; Tschandl, P.; Celebi, M.E.; Dusza, S.; Gutman, D.; Helba, B.; Kalloo, A.; Liopyris, K.; Marchetti, M.; et al. Skin Lesion Analysis Toward Melanoma Detection 2018: A Challenge Hosted by the International Skin Imaging Collaboration (ISIC). arXiv 2019, arXiv:1902.03368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codella, N.C.F.; Gutman, D.; Celebi, M.E.; Helba, B.; Marchetti, M.A.; Dusza, S.W.; Kalloo, A.; Liopyris, K.; Mishra, N.; Kittler, H.; et al. Skin Lesion Analysis Toward Melanoma Detection: A Challenge at the 2017 International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), Hosted by the International Skin Imaging Collaboration (ISIC). In Proceedings of the 15th IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), Washington, DC, USA, 4–7 April 2018; pp. 168–172. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, S.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Shen, W.; Fishman, E.; Yuille, A. Domain Adaptive Relational Reasoning for 3D Multi-Organ Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI), Lima, Peru, 4–8 October 2020; pp. 656–666. [Google Scholar]

- Han, D.; Wang, Z.; Xia, Z.; Han, Y.; Pu, Y.; Ge, C.; Song, J.; Song, S.; Zheng, B.; Huang, G. Demystify Mamba in Vision: A Linear Attention Perspective. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–15 December 2024; pp. 127181–127203. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Yang, H.; Zhou, H.Y.; Xi, Y.; Yu, L.; Li, C.; Liang, Y.; Shi, G.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, S.; et al. Swin-UMamba: Mamba-Based UNet with ImageNet-Based Pretraining. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI), Marrakesh, Morocco, 6–10 October 2024; pp. 615–625. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).