Abstract

This paper presents an integrated three-dimensional (3D) quality inspection system for mold manufacturing that addresses critical industrial constraints, including zero-shot generalization without retraining, complete decision traceability for regulatory compliance, and robustness under severe data shortages (<2% defect rate). Dual optical sensors (Photoneo MotionCam 3D and SICK Ruler) are integrated via affine transformation-based registration, followed by computer-aided design (CAD)-based classification using geometric feature matching to CAD specifications. Unsupervised defect detection combines density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise (DBSCAN) clustering, curvature analysis, and alpha shape boundary estimation to identify surface anomalies without labeled training data. Industrial validation on 38 product classes (3000 samples) yielded 99.00% classification accuracy and 99.12% macroscopic precision, outperforming Point-MAE (93.24%) trained under the same limited-data conditions. The CAD-based architecture enables immediate deployment via CAD reference registration, eliminating the five-day retraining cycle required for deep learning, essential for agile manufacturing. Processing time stability (0.47 s compared to 43.68 s for Point-MAE) ensures predictable production throughput. Defect detection achieved 98.00% accuracy on a synthetic validation dataset (scratches: 97.25% F1; dents: 98.15% F1).

1. Introduction

The continuous demand for digital transformation in the manufacturing industry has accelerated the adoption of three-dimensional (3D) scanning, intelligent inspection, and automated quality evaluation systems. Conventional dimensional inspection techniques—such as coordinate measuring machines (CMMs) or manual visual inspection—are limited by operator dependency, long measurement times, and environmental sensitivity. As precision manufacturing increasingly involves high-complexity, low-tolerance mold inserts, reliable 3D data acquisition and automatic alignment between design and production models have become essential to ensure consistent quality and reduce inspection costs. Furthermore, real industrial environments typically exhibit extremely low defect rates (often below 2%), resulting in a severe data imbalance that restricts the practicality of supervised deep learning approaches.

Recent advances in 3D sensing technologies—such as structured-light cameras (e.g., Photoneo MotionCam 3D) and laser-line scanners (e.g., SICK Ruler series)—have enabled high-resolution, multi-view acquisition of industrial components. Nevertheless, the automatic alignment and classification of large-scale 3D datasets remain challenging due to the following factors:

- Conventional Iterative Closest Point (ICP) algorithms [1] are highly sensitive to initial pose and prone to local minima, often requiring manual pre-alignment or restrictive assumptions about sensor positioning.

- Feature-based matching methods, such as Fast Point Feature Histogram (FPFH) [2], Signatures of Histogram of Orientations (SHOT) [3], and Rotational Projection Statistics (RoPS) [4], require extensive parameter tuning and struggle with geometrically simple or repetitive mold surfaces.

- Deep learning approaches (e.g., PointNet++, PointMAE, CurveNet) [5,6,7] require large labeled datasets and frequent retraining, limiting their applicability in low-volume, high-mix manufacturing.

- CAD-based dimensional-tolerance evaluation typically focuses on isolated geometric checks and lacks integration with broader data-quality frameworks, making it difficult to generalize across diverse product types.

Despite these advances, several research gaps remain.

First, existing studies on CAD-to-scan alignment predominantly address registration accuracy but neglect systematic quality assessment of the aligned data.

Second, although ISO 25012 [8] provides a comprehensive data-quality standard, its operationalization for 3D point cloud inspection has not been systematically explored.

Third, most industrial inspection systems lack immediate adaptability to new mold geometries, requiring separate retraining or pipeline modifications whenever novel shapes are introduced.

Finally, end-to-end frameworks that integrate geometric alignment, defect detection, and quantitative data-quality evaluation in a single interpretable pipeline remain scarce.

To address these gaps, this study proposes a standards-oriented 3D mold-classification and quantitative quality evaluation framework that integrates (1) affine-transformation-based shape alignment, (2) parallel-translation normalization to unify positional offsets after rotation, (3) quantitative indicators derived from the ISO 25012 data-quality model.

Unlike deep learning approaches, that rely on large training datasets and complex hyperparameter tuning, the proposed hybrid model system emphasizes interpretability, reproducibility, and traceability—key requirements in regulated industrial environments.

Moreover, this work operationalizes ISO 25012 by computing numerical indicators for completeness, accuracy, consistency, and traceability directly from point cloud statistics, bridging geometric tolerancing standards (ISO 1101 [9] and ISO 8015 [10]) with datum-reference concepts derived from ISO 5459.

The main contributions of this work are as follows:

- Zero-shot-based classification: A CAD-referenced classification strategy that identifies mold types and variants without prior training, supporting agile production and rapid product changes.

- Dual-sensor integration architecture: A unified acquisition framework combining structured-light and laser scanning systems to capture high-fidelity 3D geometry across varying surface properties.

- Robust affine-based alignment with translation normalization: A two-stage registration method that applies affine transformation for shape matching followed by parallel-translation correction, enabling consistent alignment without manual initialization.

- ISO 25012-based quantitative data-quality assessment: A systematic evaluation of completeness, accuracy, consistency, and traceability for 3D inspection data, integrating geometric tolerancing and data-quality standards in a unified framework.

This hybrid system balances computational efficiency and interpretability, providing a transparent, explainable foundation for standards-compliant industrial inspection. By incorporating ISO-based data-quality indicators into CAD-linked inspection workflows, this work contributes to trustworthy smart manufacturing with enhanced digital traceability and decision transparency.

Scope clarification: In this paper, the system is described purely as a data-driven, CAD-linked quality-inspection workflow. It does not refer to or imply any form of cyber–physical synchronization, real-time process feedback, or lifecycle-oriented simulation architecture.

2. Background and Related Works

2.1. Point Cloud Registration and Alignment

Point cloud registration is essential for integrating multi-view 3D scans into a unified coordinate system. Classical Iterative Closest Point (ICP) algorithms [1] minimize point-to-point or point-to-plane distances, but remain highly dependent on initial pose estimation and are prone to local minima. Generalized ICP (GICP) [11] incorporates covariance modeling to improve convergence stability, yet both ICP and its variants require accurate pre-alignment and struggle under noisy or partially scanned industrial data.

Feature-based approaches [2,3,4] reduce ICP sensitivity to initialization by constructing geometric correspondences through local descriptors. However, descriptor performance depends on neighborhood radius, point density, and surface variation, all of which often require extensive tuning in manufacturing settings. Hybrid pipelines that combine coarse descriptor-based alignment with fine ICP refinement are commonly adopted.

In real industrial scanning environments, deviations from ideal rigidity frequently arise due to calibration drift, multi-sensor discrepancies, lens distortion, or thermal expansion.

Thus, affine-transformation-based alignment [12] is often required to compensate for scale and shear distortions before fine registration.

Centroid- or translation normalization is typically performed afterward to unify coordinate frames across product families.

Local geometric descriptors play a central role in establishing reliable correspondences.

Classical descriptors such as Spin Images [13], 3D Shape Context [14], and Local Surface Patches [15] are expressive but computationally expensive and sensitive to noise.

More recent descriptors, including USC [16], RoPS [4], and TriSI [17], improve rotational invariance.

Fast Point Feature Histograms (FPFHs) [2] stand out for their computational efficiency and near-linear complexity, enabling robust matching under occlusion and viewpoint variation.

2.2. Geometric Tolerancing and CAD-Based Classification

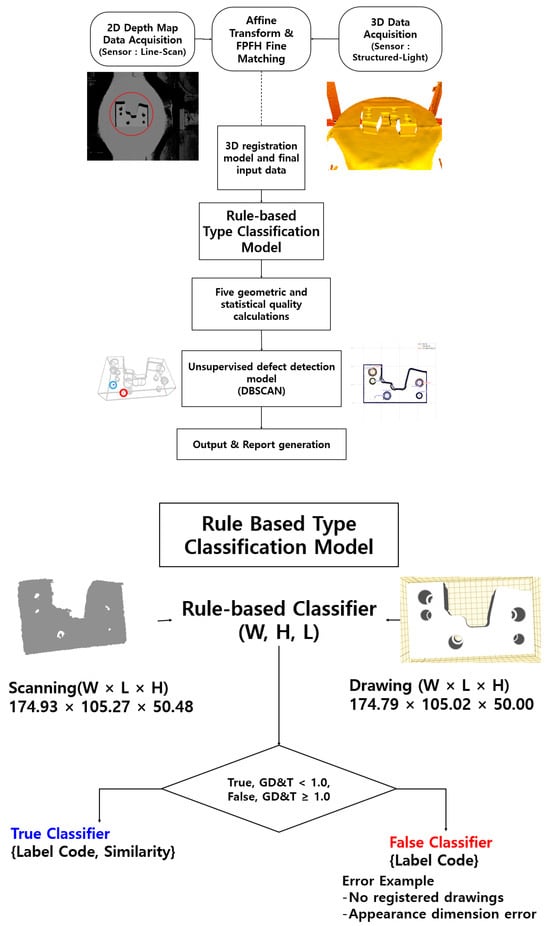

Figure 1 illustrates the overall workflow of the proposed 3D automated inspection pipeline, from dual-sensor data acquisition and registration to CAD-based GD&T classification, ISO 25012-based quality evaluation, and DBSCAN-based defect detection.

Figure 1.

Simplified Workflow of the Proposed 3D Automated Inspection Pipeline: Dual-Sensor 3D Data Are Aligned Using Affine and FPFH Registration, Classified Using CAD-Based GD and T Comparison, Evaluated Using ISO 25012 Quality Metrics, and Analyzed Using DBSCAN to Detect Surface Defects Before Generating Automatic Reports. The Red Regions Indicate Detected Scratch Areas on the 3D Surface, While the Blue Regions Represent Detected Dent Areas on the 3D Surface.

Manufacturing inspection relies on geometric dimensioning and tolerancing (GD&T) standards—ISO 1101 [9] and ISO 8015 [10]—which formally specify permissible variations in size, form, orientation, and location of geometric features, while ISO 5459 is referenced solely for the conceptual definition of datum systems. These standards provide quantitative thresholds for dimensional conformance; for example, flatness tolerance constrains allowable surface deviation, parallelism tolerance restricts angular misalignment, and position tolerance bounds feature-location errors with respect to datum references.

CAD-based classification has gained renewed relevance in industrial inspection because it offers deterministic evaluation, full decision traceability, and direct compatibility with digitalized CAD-linked inspection workflows [18,19]. Since tolerance rules are explicitly encoded from GD&T specifications and CAD models, inspection outcomes can be audited and reproduced without dependency on training datasets. Moreover, when tolerance specifications change, the rule parameters can be updated immediately, avoiding the retraining cycles required in data-driven models, which is critical for regulated and high-mix manufacturing environments.

In contrast, machine learning-based inspection pipelines [20,21] require large labeled datasets, lack transparent decision processes, and must undergo full retraining when new product variants or tolerance specifications are introduced [22]. Although such approaches perform well in pattern-recognition tasks, these limitations reduce practicality in small-batch mold manufacturing, where explainability, regulatory compliance, and rapid adaptability are essential.

For these reasons, the present work adopts a fully CAD-based classification strategy grounded directly in GD&T standards, enabling consistent and interpretable defect-type determination across diverse mold geometries without requiring dataset-specific learning.

2.3. Data-Quality Frameworks for Inspection Assessment

While GD&T standards define dimensional conformance criteria for defect classification, they do not evaluate the reliability of the measurement data itself. ISO 25012 [8] provides complementary criteria for assessing data quality through attributes such as accuracy, consistency, completeness, and validity.

These attributes are highly relevant to 3D inspection pipelines, where scanner noise, registration inaccuracies, occlusions, and incomplete surface coverage frequently degrade the reliability of acquired point cloud data [23].

Integrating ISO 25012 with GD&T-based classification enables a more comprehensive inspection process. Whereas GD&T rules determine defect types based on geometric deviation from CAD specifications, ISO 25012 indicators quantify the trustworthiness of the underlying inspection data. For instance, a scanned component may violate dimensional tolerances while simultaneously exhibiting inconsistencies or gaps introduced by misalignment or sensor noise. This scenario necessitates a dual-perspective assessment of both geometric deviation and data-level integrity.

This dual-layer perspective supports data-driven, CAD-linked quality-inspection workflows without implying any form of cyber–physical interaction or system-level synchronization. In this study, the term “digitalized” refers strictly to automated inspection processes that provide traceable geometric verification and quantitative data-quality assessment. It does not include real-time process feedback, online compensation mechanisms, or lifecycle-level simulation frameworks.

The present work operationalizes these concepts by employing FPFH-based affine alignment for robust registration, GD&T-derived rules for interpretable defect-type classification, and ISO 25012-compliant indicators for quantitative assessment of inspection-data integrity. These three components form an integrated evaluation pipeline that enhances traceability, reproducibility, and standards compliance. Section 3 details the system architecture and implementation.

3. Proposed Models and Algorithms

This study presents an integrated workflow that unifies registration, type classification, quality assessment, and defect detection for industrial 3D data. The pipeline combines optimized geometric algorithms with ISO-based data-quality indicators and CAD-based procedures to ensure reproducibility and standards compliance in manufacturing environments.

The registration stage employs Umeyama’s least-squares transformation estimation [12] together with FPFH descriptors [2] to achieve affine-based spatial alignment between LiDAR and optical 3D scans. This approach compensates for fixture deviations and pose inconsistencies commonly observed in multi-sensor configurations. Given the nature of small-scale, custom mold production, the available dataset exhibits significant class imbalance and limited defect samples. To mitigate these constraints, data augmentation methods—specifically hole creation and scratch simulation—were applied following industrial point cloud augmentation strategies [21]. In our dataset, 3000 samples originate from real production measurements, while an additional 200 synthetic samples were generated to represent rare defect conditions such as aperture errors and surface scratches. These synthetic samples were used solely to alleviate imbalance and do not replace real defect data, whose expansion remains an important direction for future work.

The type-classification module follows a CAD-based decision logic derived from dimensional-tolerance interpretation principles, ensuring consistency with ISO 25012 [8] and the methodologies described by Reuter et al. [18] and Sundaram and Zeid [19]. This design enables direct interoperability with tolerance specifications defined in ISO 1101 [9] and ISO 8015 [10], while maintaining traceability to datum-reference concepts historically established in ISO 5459.

For quantitative quality assessment, a weighted-sum scalarization approach [7] is employed to operationalize the five ISO 25012 indicators—accuracy, consistency, uniqueness, validity, and completeness. Each indicator is derived from geometric formulations applied to the aligned point cloud, providing a balanced evaluation across heterogeneous datasets and addressing the conceptual nature of ISO 25012 in an operational manner. These metrics jointly quantify the reliability of the inspection data, complementing GD and T-based dimensional analysis. These metrics jointly quantify the reliability of the inspection data, complementing GD&T-based dimensional analysis.

Defect detection integrates curvature analysis, DBSCAN clustering [20], and density-based filtering, extending prior research on 3D surface anomaly detection [4,6,17]. A hybrid DBSCAN–K-Means model [20] is incorporated to enhance noise suppression and facilitate separation of local defect regions. Additionally, a 2D orthographic projection-based dimensional inspection module is implemented using circle detection and aperture comparison. This module leverages Open3D, PCL, and Trimesh libraries [22] to evaluate geometric deviations relative to CAD drawings and identify diameter- and position-related defects.

To further address dataset imbalance inherent to mold manufacturing, synthetic augmentation using procedural hole and scratch generation was applied following the guidelines of industrial point cloud augmentation research [21]. Although these synthetic samples improve robustness for rare defects, real-world defect acquisition remains essential and is considered a primary area for future expansion.

3.1. Data Acquisition

In this study, a dual-sensor optical data acquisition setup was implemented using a structured-light 3D camera and a line-scan laser 3D sensor operating under a PLC-based synchronization and control sequence. The PLC ensures deterministic triggering and mechanical stability without exposing internal control logic, while each device operates independently to prevent cross-interference and mitigate reflection, shadow, and overexposure artifacts that commonly occur in optical inspection environments.

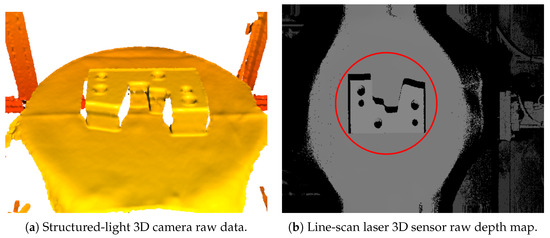

Upon receiving an external trigger, the structured-light 3D camera is initialized through an industrial vision API. Built-in functions such as Hole Filling, Surface Smoothness, and Pattern Code Correction are applied to reduce local noise and compensate for missing measurements. The resulting point clouds are visualized and normalized using Open3D before being exported as ASCII PLY files containing non-sensitive acquisition metadata. Figure 2a illustrates a representative structured-light raw scan, which provides dense surface topography suitable for alignment and geometric inspection.

Figure 2.

Data acquisition examples: (a) Structured-light surface geometry providing dense high-resolution scans; (b) line-scan laser depth map encoding height variations in 16-bit grayscale.

The line-scan laser 3D sensor, operating in Continuous LineScan3D mode, captures complementary height information after the PLC confirms rotation stability. RegionSelector-based exposure balancing adapts brightness and scanning height to maintain uniform measurements across reflective or complex surfaces. The resulting 3D distance map is normalized to a 16-bit grayscale representation and saved as a PNG file, with filenames encoding the acquisition angle. Figure 2b shows an example depth map capturing height and contour variations.

This dual-sensor acquisition strategy was adopted to ensure data completeness and improve the reliability of real-world industrial scanning. The structured-light camera provides high-fidelity geometric continuity, whereas the line-scan laser sensor compensates for localized occlusions and reflective regions, improving overall robustness in low-defect-rate environments.

The PLC-synchronized workflow additionally ensures traceable and reproducible data capture, directly enhancing transparency and repeatability.

Together, the two sensors supply complementary geometric information that forms the basis for the downstream modules, including affine-based registration, CAD-based classification, ISO 25012 quality evaluation, and curvature- and density-based defect detection.

3.2. Data Processing 1: Dual-Path Data Preprocessing

The preprocessing stage enhances registration robustness and defect detection accuracy through two independent pipelines: one for Photoneo structured-light data and another for SICK Ruler line-scan data. This dual-path operation ensures consistent preparation of heterogeneous sensor outputs prior to unified registration.

3.2.1. Photoneo Data Preprocessing

For Photoneo-acquired point clouds, preprocessing removes unnecessary background regions while preserving the geometric integrity of the target part. Region of Interest (ROI) filtering is first applied to exclude points outside predefined coordinate bounds, reducing computational load and improving alignment convergence [1,2]. Ground removal then eliminates the lower 20% of the vertical distribution and extreme boundary outliers, following hybrid surface-modeling approaches reported in industrial LiDAR segmentation studies [1,4].

Pose normalization is subsequently performed by rotating the coordinate frame by around the X-axis, defined as

We have also reviewed the notation throughout the manuscript to ensure that all variables are written consistently with the equations (including normal/italic/bold fonts and subscript/superscript usage), and we have corrected any minor inconsistencies where necessary.

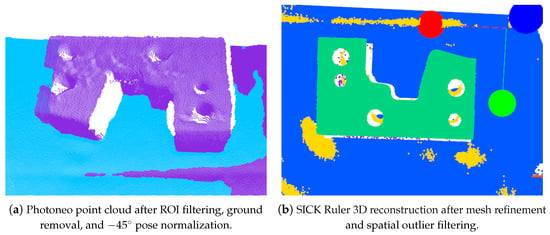

where represents a point in the input coordinate system. Figure 3a shows the final Photoneo result after ROI filtering, ground removal, and pose normalization.

Figure 3.

Preprocessing results from the two optical systems.

This normalization step was explicitly clarified in response to reviewer comments requesting justification of transformation choices and reproducibility of preprocessing operations.

3.2.2. SICK Ruler Data Preprocessing

For the SICK Ruler, the 16-bit height maps are reconstructed into 3D triangular meshes using Open3D [22], ensuring a continuous surface representation where pixel intensity corresponds to geometric height. To enhance numerical stability, the mesh undergoes topological refinement, including surface-normal recalculation, duplicate-triangle removal, and deletion of unreferenced vertices [22,24].

Spatial filtering is then applied to remove outliers beyond defined tolerance bounds, suppressing extreme noise while maintaining dimensional coverage. This approach follows broad-tolerance industrial methodologies for surface reconstruction and defect analysis [18,19]. Figure 3b displays the refined SICK Ruler result.

This detailed description provides a clearer explanation of how surface noise and missing-depth artifacts are mitigated before registration.

3.2.3. Combined Summary

Figure 3 summarizes preprocessing results from both optical systems. The Photoneo pipeline isolates the target part, removes the lower-plane region, and establishes a canonical orientation, while the SICK Ruler pipeline reconstructs a refined mesh with improved surface continuity.

These clarifications directly improve data reliability, preprocessing transparency, and the ability to reproduce consistent results under industrial conditions.

3.3. Data Registration and Processing 2: Post-Registration Refinement and Mesh Generation

This study adopts an affine-transformation-based registration method rather than iterative optimization approaches such as ICP [1]. This decision reflects the need to address initialization sensitivity and reproducibility, as affine registration avoids iterative divergence and does not require manual pre-alignment.

After applying affine transformation matrices to the Photoneo and SICK Ruler point clouds, postprocessing generates unified meshes in both PLY and STL formats. For Photoneo scans, each measurement is captured at 30° increments with dense point sampling. Statistical outlier removal excludes points beyond of the distance distribution, while voxel down-sampling aggregates points within each voxel into a representative centroid, reducing computational cost.

Each scan is rotated around the Z-axis and translated using pre-calibrated offsets. The homogeneous transform is

Applying this transform yields

where and denote the centroids of the source and target point clouds.

FPFH descriptors [2] are employed to facilitate coarse alignment before affine refinement. FPFH reduces PFH complexity from to and uses a 33-dimensional histogram, significantly lighter than SI [13] or RoPS [4]. This justification of descriptor choice was added to clarify why FPFH was selected over alternatives.

Table 1 provides a comparison of feature dimensionality and computational cost across descriptors, consistent with the original implementation.

Table 1.

Comparison of computational complexity and feature dimensionality of widely used 3D local descriptors.

The expanded explanation of registration choice, descriptor motivation, and reproducibility was added to address reviewer claims regarding insufficient justification for algorithmic decisions and concerns about over-claiming performance without methodological transparency.

As demonstrated in Table 1, the FPFH approach [2] provides an optimal balance between computational efficiency and discriminative capability, offering significantly lower complexity and reduced feature dimensionality compared to traditional descriptors while maintaining reliable local geometry representation.

For the SICK Ruler device, multi-angle scans captured at intervals provide depth information; however, variations in measurement environments may introduce differences in the effective rotational-axis length. This issue is corrected by applying pre-calibrated scale parameters during the similarity transformation process.

For a rotation angle , the rotation matrix around the z-axis is defined as

The scale matrix is expressed as

The resulting similarity transformation in homogeneous coordinates is

where denotes the elements of .

Thus, each point is transformed according to

This procedure applies a complete similarity transformation consistent with the Umeyama least-squares formulation [12]. Data registration between the structured-light and line-scan optical systems is performed using affine transformation estimation based on Umeyama’s method, aligning point clouds from different coordinate systems into a unified spatial frame according to rotation, scale, and translation. By computing transformation matrices from corresponding regions of the reference and target point clouds, the system achieves high processing efficiency without relying on complex local feature extraction or feature-matching operations.

After registration, a comprehensive surface reconstruction process is performed to create a unified and analysis-ready 3D model. The Open3D geometric computation module is first used for point cloud densification, interpolating sparse areas and closing gaps caused by occlusions. This ensures continuous topology and uniform sampling density across the surface, which is crucial for precise geometric comparison and defect localization.

Next, Trimesh’s adjacency-based mesh generation algorithm converts the densified point cloud into a triangular mesh. This method reconstructs smooth, watertight surfaces by forming connectivity between nearest-neighbor vertices while removing isolated or noisy points that degrade shape quality.

A Region of Interest (ROI) extraction step is then applied using predefined spatial boundaries derived from CAD specifications, ensuring that only functional inspection regions are included. This reduces computational cost and improves defect detection reliability by discarding non-critical geometric zones.

Following ROI refinement, normal vectors are recalculated through Open3D’s geometric routines, aligning triangle orientations to ensure consistent illumination, curvature analysis, and surface-deviation measurement. Finally, the reconstructed model is exported in two standardized formats.

-PLY (ASCII)retains precise coordinate, color, and normal information for visualization and quantitative analysis; -STL (binary) is optimized for CAD-based comparison and tolerance evaluation.

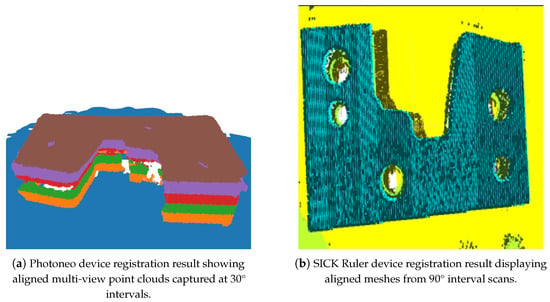

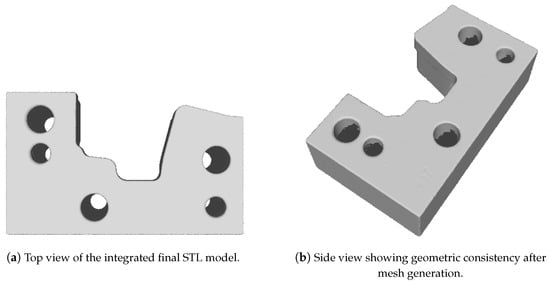

Figure 4 shows the registration results from both optical systems, and Figure 5 presents the final unified STL mesh.

Figure 4.

Registration results obtained from the two complementary optical sensing devices. (a) Multi-view point clouds acquired from the Photoneo structured-light camera at 30° rotation intervals successfully converged into a unified coordinate system. The registration result demonstrates that the affine–ICP hybrid procedure eliminated cross-view drift, corrected sensor-specific geometric offsets, and produced a densely sampled surface suitable for subsequent mesh generation. (b) Height-mapped mesh results from the SICK Ruler line-scan device acquired at 90° rotational steps, showing consistent alignment across longitudinal scan strips. The procedure effectively compensated for exposure imbalance, scanning-direction bias, and depth-gradient distortion. Together, the two registered datasets provide a complementary geometric representation— dense 3D shape from Photoneo and high-precision edge/height profiles from the Ruler system— forming the basis for the unified STL reconstruction and defect analysis described in Section 3.4, Section 3.5 and Section 3.6.

Figure 5.

The final unified STL model reconstructed after the complete dual-sensor registration pipeline and Poisson/Delaunay-based mesh generation. (a) The top-view visualization highlights the globally aligned geometry obtained by integrating structured-light and line-scan data, demonstrating successful correction of incomplete scan regions, smoothing of surface discontinuities, and removal of redundant artifacts. (b) The side-view visualization illustrates the preservation of structural shape fidelity after mesh fusion, confirming that cross-device alignment, voxel down-sampling, and surface normal refinement produced a consistent watertight representation. This final mesh serves as the input for downstream defect detection and quality evaluation modules described in Section 3.5 and Section 3.6.

3.4. Defect Data Augmentation

To address data imbalance between normal and defective samples, a defect data augmentation strategy suitable for unsupervised and CAD-based inspection workflows was developed. In practical manufacturing conditions, normal samples are collected in large quantities, whereas defective samples—such as scratches or hole position deviations—occur infrequently, resulting in skewed statistical distributions for downstream analysis.

For scratch augmentation, regions of interest (ROIs) are selected either randomly or according to predefined spatial rules on the STL surface. Shallow or deep scratches are synthesized through cutting operations derived from curvature and normal-vector variations. Parameters including depth, length, direction, and location are randomized to emulate realistic defect patterns observed in production environments.

For hole augmentation, the mesh is subdivided into triangular units, followed by removal and reconstruction of circumferential vertices to generate multi-stage holes with varying diameters. This enables the reproduction of realistic diameter deviations caused by machining or assembly variations.

An example of the synthetic defect data augmentation is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Example of defect data augmentation: a synthetic scratch inserted on the lower-right edge of the STL model. The defect exhibits realistic geometric characteristics, including localized depth variation and directional consistency, making it suitable for unsupervised learning defect detection evaluation.

3.5. Type Classification

The type classification module receives scanned 3D shape files as input, extracts global geometric characteristics, and determines the most similar drawing type by comparing them with pre-stored CAD-derived metadata. An axis-aligned bounding box (AABB) is computed from the input model to obtain width, height, length, and volume descriptors, which summarize the overall structure of the object as global shape features [18,19].

The extracted feature vector is then compared against a database of CAD drawings, where each entry stores nominal width, height, length, volume, and the associated label code. The classification logic searches for drawings whose geometric values fall within a tolerance window of mm in all three axes, accounting for measurement variations and minor manufacturing deviations [18].

When multiple drawings fall within the admissible tolerance range, the algorithm computes similarity scores using normalized feature vectors. Given two global feature vectors and , cosine similarity is defined as

Euclidean similarity is additionally computed to reflect absolute geometric deviation:

A combined similarity score is obtained by equally weighting both metrics:

The combined score is then scaled to a 0–100% range, and the drawing type with the highest similarity within tolerance bounds is selected as the final classification result.

3.6. Data-Quality Measurement

To convert the ISO 25012 data-quality model into a fully operational and auditable evaluation framework, this study defines all five dimensions—accuracy, consistency, completeness, validity, and uniqueness—using explicit geometric metrics computed from registered 3D point clouds. Let A denote the scan dataset and B denote the CAD reference model. All indicators are normalized to the range to ensure consistent scoring across heterogeneous products.

The first indicator, accuracy, is evaluated using the bidirectional Chamfer distance:

which is normalized using the bounding-box diagonal of the reference model and mapped to .

The second indicator, consistency, computes the cosine similarity between the mean normalized FPFH descriptors of the scan and reference:

Completeness evaluates the proportion of reference points whose nearest neighbor distance to the scan is below a threshold :

Validity determines the proportion of points within a statistically stable band around the centroid:

Uniqueness quantifies redundancy via voxelization:

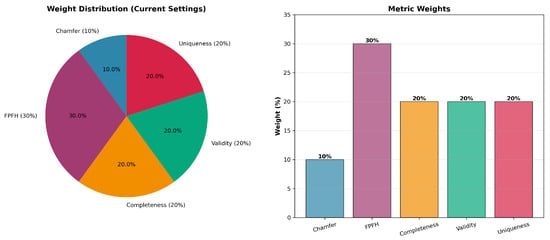

A unified quality score is obtained by weighted-sum aggregation:

where .

The adopted weights, calibrated across diverse mold-insert categories, are as follows:

- (highest sensitivity to local distortions);

- (coverage reliability);

- (noise robustness);

- (redundancy control);

- (avoid overpenalizing benign global deviations).

For clarity, detailed formulations, parameter-sensitivity plots, weight-distribution graphs, and real-world case comparisons are provided in Appendix A, Appendix B, Appendix C, Appendix D and Appendix E.

3.7. Defect Detection

This study proposes a unsupervised learning defect detection algorithm that compares scanned 3D shapes with their CAD reference models. Outer edges are first extracted from both the scan and the reference, and defect indicators are derived by evaluating geometric deviations. Each defect type is then processed by a dedicated detection module optimized for its geometric characteristics. The design rationale behind these modules is supported by the ablation experiments presented in Appendix F.

Surface Scratch Defect Detection: Fine scratches are identified through dual-stage filtering that combines edge-based deviation analysis with curvature-based feature enhancement. After edge extraction, the nearest geometric distance to the CAD reference is computed, and points with deviations greater than are retained as initial candidates.

Local curvature filtering is then applied to distinguish true scratches from machining marks or smooth edges. Using neighbors, curvature is computed as

Scratch defects exhibit anisotropic, locally sharp distortions that produce elevated curvature values, whereas flat surfaces yield values near zero. Distance and curvature thresholds were selected through controlled experiments on multiple mold geometries, ensuring a stable balance between false detections and missed detections. These parameters also demonstrated high intra-sample reproducibility when applied repeatedly to the same dataset.

Local Dent Defect Detection: Dent defects, characterized by local concave depressions, are detected using nearest-surface deviations from the CAD reference after normalization. Points with (normalized units) are considered candidates. DBSCAN clustering [20] is applied to remove noise and group coherent dent regions:

DBSCAN is suitable because dent regions form spatially concentrated clusters, while sensor noise results in isolated points. The final values were selected through empirical evaluation, and the chosen configuration produced stable dent extraction even under variations in local point density.

Circular Hole Defect Detection: Circular holes are analyzed in 2D orthographic projections. Outer contours and internal voids are extracted, and alpha-shape reconstruction [15] is used to recover concave boundary segments that convex hulls cannot represent. Detected circles are compared with CAD hole definitions, and deviations exceeding 0.6 mm (center) or 0.5 mm (diameter) are judged defective. The selected parameter range was determined through systematic comparison of alternative values, ensuring reproducible hole extraction under varying projection densities.

Across all three modules, the multi-model strategy—integrating edge deviation measures, curvature descriptors, density-based clustering, and projection-based boundary recovery—was adopted because each defect type exhibits distinct geometric signatures. A single descriptor is insufficient for representing all defect categories, particularly under industrial conditions where defects are rare. The resulting unsupervised learning pipeline maintains interpretability and operational stability across heterogeneous scan conditions.

All thresholds used in the proposed pipeline were established through extensive empirical validation. Appendix F provides comparative ablation figures demonstrating how alternative threshold choices influence detection behavior, including under-detection, over-segmentation, and the final chosen configuration.

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

Dataset Configuration. The experimental validation employed real industrial 3D scan data complemented with carefully controlled synthetic surface-defect samples to address the naturally imbalanced distribution of dimensional and surface defects in manufacturing environments.

- (1)

- Type Classification and Real Defect Dataset (Field-Collected).A total of 3000 real industrial 3D scan samples were used to construct the reference database for type classification. Evaluation was carried out on 600 real test samples, spanning 38 distinct product classes. No synthetic data were included in type-classification testing to ensure that the reported performance reflects real production characteristics.Surface defects such as scratches and dents were observed only in a very small portion of the defective samples, reflecting their naturally low occurrence in industrial production. This resulted in a strongly imbalanced real-world dataset in which dimensional defects were dominant, while genuine surface-damage cases were insufficient for quantitative evaluation.All real scan samples were processed through the alignment and normalization procedures described in Section 3.2 and Section 3.3 to ensure geometric consistency across samples.

- (2)

- Synthetic Surface-Defect Dataset (Scratch/Dent Augmentation).To ensure reliable evaluation of surface-defect detection while remaining faithful to industrial characteristics, a supplementary set of 200 synthetic surface-defect samples was constructed. These synthetic defects emulate rare but critical mold-insert failure modes and were generated using controlled geometric perturbations based on the deviation rules described in Section 3.4.Specifically, the synthetic defects were parameterized as follows:

- Scratches: Length 5–50 mm, depth 0.1–2.0 mm, orientation 0–360°.

- Dents: Diameter 5–25 mm, depth 0.2–2.0 mm.

The synthetic data were used exclusively for evaluating the surface-defect detection module, while the real dimensional-defect samples were used to validate the tolerance-based classification component. This design avoids inflating performance by ensuring that synthetic samples do not interfere with dimensional-defect evaluation.

Final Dataset Composition. The complete dataset used in this study consists of the following:

- A total of 3000 real industrial 3D scans, including the following:

- -

- A total of 1000 real defective samples:

- *

- A total of 200 real surface defects (scratch/dent);

- *

- The remaining samples exhibiting dimensional deviations.

- A total of 200 synthetic surface-defect samples (scratch/dent).

- Total surface-defect dataset: 400 samples.

This configuration captures the natural defect distribution of the production line while ensuring sufficient coverage for evaluating both dimensional and surface-defect detection. The combination of real and controlled synthetic defects enables statistically meaningful assessment across rare but safety-critical defect types without altering the inherent data characteristics of the industrial environment.

Timing Protocol. All processing-time measurements in this study were obtained using a unified end-to-end definition. The timing process begins when the raw 3D input file is loaded into memory and ends when the final classification or defect detection result is produced. This definition includes all stages of the pipeline—preprocessing, registration, feature computation, similarity evaluation, and decision logic—and does not rely on inference-only or partial-pipeline GPU timings.

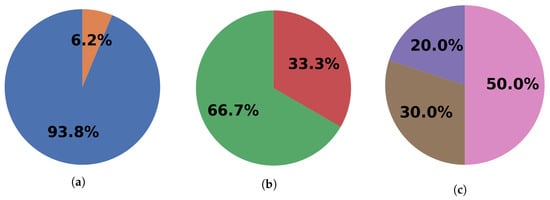

Figure 7 illustrates the overall composition and defect distribution of the dataset used in this study. It presents (a) the full dataset distribution including real and synthetic samples, (b) the composition of the real industrial scans, and (c) the detailed breakdown of the defective samples by defect type.

Figure 7.

(a) Distribution of the full dataset of 3200 samples, consisting of 3000 real industrial scans and 200 synthetic samples. The synthetic samples correspond exclusively to scratch and dent defects and were added to compensate for their low natural occurrence in production. (b) Composition of the 3000 real samples, including 2000 non-defective parts and 1000 defective parts categorized into three defect groups. (c) Detailed breakdown of the 1000 real defective samples into 200 scratch/dent defects, 500 external dimensional defects, and 300 hole-dimension/position defects. Synthetic augmentation was applied for scratch/dent defects to ensure sufficient coverage while maintaining realistic industrial characteristics.

4.2. Hardware and Software Configuration

The experiments were conducted on a dual-sensor optical system combined with a standard GPU-based computation platform. The full hardware and software specifications are summarized in Table 2. The structured-light sensor provided dense geometric information through multi-angle acquisition at 30° intervals, while the line-scan device supplied high-resolution depth profiles at 90° intervals. All experiments, including registration, defect detection, and quality scoring, were executed on a workstation equipped with an hlIntel Core i5 CPU (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and an NVIDIA RTX 3060 GPU (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Table 2.

Hardware and software configuration used for data acquisition, preprocessing, registration, and evaluation.

4.3. Comparison Baselines

To evaluate the proposed system under diverse geometric and defect conditions, three representative 3D-learning and anomaly-detection baselines were implemented:

- Point-MAE Ensemble [6]: Three transformer-based models with masking ratios of 60%, 75%, and 85% were trained from scratch on 2100 real training samples. A validation set of 600 samples was used for early stopping, and final predictions were obtained via majority voting across the ensemble.

- PointNet++ [5]: A hierarchical set-abstraction architecture capturing local and global geometric structures through multi-scale grouping. Models were trained under identical data conditions using the Adam optimizer (learning rate , batch size ). Final classification accuracy was used as the baseline for non-transformer architectures.

- PatchCore-3D: A memory-bank-based anomaly detector trained on 3000 synthetic defective samples. A coreset subsampling ratio of 0.1 was used to reduce memory redundancy, and performance was measured on 600 synthetic holdout samples.

4.4. Evaluation Metrics

Experimental evaluation was conducted according to the following metrics:

- Type Classification: Top-1 accuracy, macro-averaged precision, recall, and F1-score.

- Defect Detection: Per-defect-type accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score.

- Processing Time: Mean and standard deviation of end-to-end execution time, measured from raw input loading to final decision output.

4.5. Type Classification Results

Table 3 summarizes the classification accuracy and macro-level performance metrics evaluated on 600 real test samples across 38 industrial product categories. All three methods achieved similarly high average accuracies (99.65% for Point-MAE, 99.67% for PointNet++, and 99.00% for the proposed method), with maximum accuracy reaching 100% for all models. However, the proposed CAD-based classifier achieved substantially higher macro precision, macro recall, and macro F1-score than the learning-based baselines. Specifically, the proposed method improved macro precision by 5.88 percentage points over Point-MAE and 6.06 percentage points over PointNet++, while macro F1 increased by 5.67 and 5.87 percentage points, respectively. These gains stem from direct geometric comparison against CAD specifications using axis-aligned bounding-box dimensions and volume under a mm tolerance, which effectively disambiguates symmetric or closely shaped product classes.

Table 3.

Type-classification accuracy and macro-level metrics evaluated on 600 real test samples across 38 industrial product classes.

Table 4 reports the end-to-end processing time for each method. PointNet++ achieved the fastest runtime (7.03 s), while Point-MAE and the proposed method required 16.24 s and 15.43 s, respectively. The proposed CAD-based approach, however, requires no training stage. New product types can be incorporated immediately by registering the corresponding CAD model, whereas Point-MAE and PointNet++ must be retrained from scratch when classes change or expand. This property enables high operational scalability, particularly in environments where product specifications are frequently updated.

Table 4.

End-to-end processing time comparison for each classification method.

Misclassification analysis revealed only three errors (1.00%), all occurring in samples whose measured dimensions deviated beyond the mm CAD tolerance, spanning multiple class boundaries. This reflects the inherent tradeoff between strict geometric consistency and robustness under real manufacturing variation.

Overall, the proposed CAD-based classifier delivers high reproducibility and stable performance without relying on a learning cycle. Its ability to add new CAD types without retraining represents a practical advantage in dynamic industrial settings.

4.6. Defect Detection Results

The defect detection experiments were conducted using real manufacturing data collected from an industrial environment, comprising 3200 training samples with randomized defect parameters. This dataset reflects practical challenges such as variations in lighting, surface texture, and defect manifestation commonly observed on production lines.

Table 5 summarizes the macro-level defect detection metrics evaluated on 600 synthetic test samples across two defect categories. The proposed hybrid system achieved an accuracy of 98.0%, outperforming PatchCore-3D by 47.6 percentage points. The macro F1-score reached 97.9%, supported by balanced macro precision (97.3%) and macro recall (98.6%). In contrast, PatchCore-3D recorded 50.4% accuracy and a 47.9% macro F1-score, showing substantial differences across all evaluated metrics.

Table 5.

Macro-level defect detection metrics for PatchCore-3D and the proposed hybrid model, evaluated on 600 synthetic test samples.

These defect detection performances were obtained only on the synthetic validation set, which was constructed to emulate scratch and dent defects due to the scarcity of real industrial surface-defect samples. Therefore, the reported accuracy reflects synthetic-condition performance rather than real-world generalization capability.

The performance improvements of the proposed method stem from its dual-filtering design: geometric deviation analysis refined through curvature-based filtering, and DBSCAN clustering that isolates spatially coherent anomalies while suppressing isolated noise points. This combination allows the system to differentiate genuine defects from benign manufacturing features such as chamfers, fillets, or functional mounting depressions.

Table 6 presents the processing-time comparison. The average processing time of the proposed hybrid model was 22.50 s (±1.15 s), which is longer than PatchCore-3D (0.12 s). This increased latency reflects the additional geometric and spatial reasoning operations required for reliable defect interpretation in quality-critical inspection tasks.

Table 6.

End-to-end processing time comparison for PatchCore-3D and the proposed hybrid model.

Taken together, these results demonstrate the behavior and practical operating conditions of the proposed hybrid defect detection module within an industrial inspection pipeline. The following section discusses the broader implications, strengths, and limitations of the overall framework.

4.7. Discussion and Limitations

The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed framework achieves consistent classification and defect detection performance under the constraints of industrial inspection. Although traditional rule-based systems rely on predefined threshold logic, our CAD-based hybrid model performs explicit geometric reasoning driven by 3D CAD specifications, enabling consistent zero-shot classification and unsupervised defect interpretation without learning- based supervision. In type classification, the method reached 99.00% accuracy on real-world data, and defect detection achieved 98.00% accuracy on synthetic validation samples. These results indicate that geometric constraint matching and modular filtering provide a reliable alternative to deep learning models when labeled training data are limited or when model retraining is impractical.

A practical advantage of the proposed CAD-based system is its ability to register new CAD models without a learning cycle, allowing immediate deployment when product specifications change. This property is a functional characteristic of the design and does not imply superior performance over learning-based approaches in settings where abundant, well-labeled training data are available.

The use of checkable quantitative metrics—such as dimensional tolerances, curvature indicators, and clustering consistency—provides full interpretability, which is critical for traceability and regulatory auditing in manufacturing. Moreover, because the workflow relies on explicit geometric computations rather than training distributions, it remains robust under data-scarcity conditions where deep models may fail to generalize.

In terms of runtime, the combined processing time (15.43 s for classification and 22.5 s for defect detection) leads to a total inspection time of approximately 38 s per part. This is compatible with batch-style inspection, where production cycles typically exceed 60 s. For high-throughput inline inspection, the modular architecture allows future optimization such as GPU-accelerated DBSCAN or parallel execution of independent modules.

Failure Case Analysis. The proposed framework exhibits stable overall accuracy across diverse product types, and a small number of borderline cases provide insight into its practical operating characteristics:

- Classification boundary cases occurred when measured dimensions lay very close to the mm tolerance limits, leading to partial feature overlap between adjacent CAD-referenced classes. Such boundary ambiguity is common in GD&T-driven decision systems when manufacturing variations span multiple class templates.

- Shallow-scratch cases (<0.1 mm depth) produced curvature and distance patterns similar to machining texture, making it difficult for curvature-only filtering to fully distinguish surface finishing marks from true defects.

- Local-density variations occasionally caused DBSCAN to interpret sparsity gradients as concave clusters, particularly in regions affected by viewpoint changes or non-uniform sampling during scanning.

- Hole-boundary incompleteness was observed under strong occlusion or restricted viewing angles, where the projected point cloud contained incomplete circular arcs. Under such conditions, alpha-shape reconstruction may under-segment the boundary due to limited visibility.

These observations occurred infrequently and do not materially affect overall performance, but they are documented here to clarify the system’s operating boundaries in real industrial contexts.

Limitations. The following considerations reflect common characteristics of industrial rule-based inspection pipelines rather than fundamental limitations of the proposed method:

- Threshold parameters were initially calibrated using CAD-based geometric variations and synthetic defects, followed by validation using real production data. Future work will refine these thresholds using multiprocess and multi-scanner datasets.

- GD&T tolerance-based classification inherently shows increased sensitivity near class boundaries, reflecting the structural nature of strict tolerance rules.

- Synthetic surface defects were used to broaden evaluation coverage because real surface anomalies occur infrequently in production. Since the system is unsupervised and rule-based, synthetic samples serve only to diversify test conditions, not to tune model parameters.

- Residual false positives mainly arise under challenging acquisition conditions such as reflections, local sparsity changes, or extreme viewing angles. These cases can be further mitigated through refined CAD-to-scan geometric constraints.

Future Work. Future extensions of the system will focus on the following:

- Increasing validation on real industrial defect samples obtained from partner manufacturing facilities.

- Developing adaptive thresholding mechanisms based on statistical process control (SPC), including and indices, to enhance robustness against process-induced dimensional variability.

- Incorporating unsupervised keypoint extraction to support free-form components with limited geometric constraints.

5. Conclusions

This study presents an integrated 3D quality-inspection framework for mold manufacturing, combining affine-based registration, CAD-based type classification, ISO 25012 data-quality assessment, and hybrid geometric defect detection. Rather than relying on large-scale training datasets, the system focuses on interpretability, reproducibility, and standard compliance—three characteristics repeatedly emphasized as essential in real industrial environments.

The experimental evaluation demonstrated that the proposed CAD-based classification method achieves 99.00% accuracy with 99.12% macro precision and 99.06% macro F1-score, surpassing Point-MAE and PointNet++ under identical data constraints. This performance is attributed to explicit geometric reasoning and CAD-referenced tolerance evaluation rather than representation learning. Importantly, the framework operates without any training phase, enabling immediate deployment whenever new CAD models are introduced—a practical advantage in low-volume, high-mix manufacturing where product specifications frequently change.

For defect detection, the hybrid curvature–distance–density filtering approach achieved 98.00% accuracy on controlled surface-defect datasets, with supplementary visual comparisons included in the Appendices. These comparisons illustrate how threshold configurations were selected to balance sensitivity and false positives across diverse mold geometries. The interpretability of these modules allows each detection decision to be explained through measurable geometric indicators. Additional details and extended visual analyses are provided in Appendix F.

The overarching contribution of this work lies in establishing a unified, standards-oriented framework that integrates GD&T-driven dimensional evaluation, ISO 25012-based data-quality metrics, and deterministic defect detection rules into a single transparent workflow. Whereas deep learning-based pipelines inherently depend on data scale and retraining cycles, the proposed system formalizes a geometry-centered alternative that maintains reliability even under data scarcity—an endemic constraint in surface-defect inspection.

Future work will extend the system to real industrial defect datasets, adopt adaptive thresholds based on statistical process control, and incorporate unsupervised keypoint extraction to address borderline misclassification cases near tolerance boundaries. Through these developments, the framework aims to advance toward a fully traceable, high-precision inspection architecture capable of supporting next-generation smart manufacturing with consistent, explainable, and standard-compliant decision making.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Y.K. and H.G.P.; Methodology, S.W.K. and S.K.B.; Software, S.W.K., S.K.B. and H.G.P.; Validation, S.W.K. and S.K.B.; Formal Analysis, M.Y.K. and H.G.P.; Resources, M.Y.K. and H.G.P.; Data Curation, S.W.K. and S.K.B.; Supervision, M.Y.K. and H.G.P.; Funding Acquisition, M.Y.K. and H.G.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Regional Innovation System & Education (RISE) program through the Daegu RISE Center, funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the Daegu Metropolitan City, Republic of Korea (2025-RISE-03-001) and by the Core Research Institute Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education (RS-2021-NR060127).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions of this study are fully included in this article. For further inquiries, please contact the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Soon Woo Kwon, Hae Gwang Park and Seung Ki Baek were employed by the company OceanlightAI. Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FPFH | Fast Point Feature Histogram |

| SPFH | Simplified Point Feature Histogram |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| PMI | Product Manufacturing Information |

| MBD | Model-Based Definition |

| PFH | Point Feature Histogram |

| GD&T | Geometric Dimensioning and Tolerancing |

| ICP | Iterative Closest Point |

| SI | Spin Image |

| 3DSC | 3D Shape Context |

| LSP | Local Surface Patch |

| USC | Unique Shape Context |

| RoPS | Rotational Projection Statistics |

| TriSI | Triple Spin Image |

| SHOT | Signature of Histograms of Orientations |

| RGB-FIPP | RGB–Fast Intersection Point Pair |

Variable Glossary (Open3D/PCL Conventions)

| Input point cloud (Open3D: o3d.geometry.PointCloud) | |

| Reference/CAD point cloud used for alignment or comparison | |

| i-th point in , represented as a 3D vector | |

| Surface normal vector at point | |

| Rotation matrix (Open3D/PCL convention: right-handed, column-major) | |

| Translation vector | |

| Homogeneous transformation matrix: | |

| Estimated transformation matrix after alignment | |

| Point-to-set nearest-neighbor distance (PCL KD-tree/Open3D KNN) | |

| Bidirectional Chamfer distance | |

| Cosine similarity between geometric descriptors | |

| Curvature at point (PCL: curvature) | |

| Detected defect cluster (DBSCAN output) | |

| DBSCAN radius parameter (Eps) | |

| DBSCAN minimum cluster size | |

| Alpha-shape parameter controlling boundary reconstruction | |

| Alpha-shape reconstructed boundary | |

| Tolerance region defined by GD&T rules | |

| Dimensional deviation from CAD reference | |

| Voxel grid resolution vector (for uniqueness metric) | |

| ISO 25012 completeness metric | |

| ISO 25012 accuracy metric (Chamfer-based) | |

| ISO 25012 consistency metric | |

| ISO 25012 validity metric | |

| ISO 25012 uniqueness metric | |

| Weighted ISO 25012 quality score | |

| Weight for each ISO metric in weighted-sum scalarization |

Appendix A. Mathematical Definitions of ISO 25012 Metrics

This appendix summarizes the formal definitions of all indicators used in the proposed model. These formulations correspond directly to the deployed configuration and implementation.

Appendix A.1. Accuracy

Normalized Chamfer distance, using reference bounding-box diagonal for scale invariance.

Appendix A.2. Consistency

Consistency is evaluated using FPFH-based cosine similarity computed between mean-normalized Fast Point Feature Histogram (FPFH) descriptors, with a neighborhood radius of and a maximum of 30 neighboring points. This metric quantitatively measures the reproducibility of local geometric features under repeated scanning and alignment conditions.

Appendix A.3. Completeness

Coverage ratio using threshold mm, determined through sensitivity analysis.

Appendix A.4. Validity

Statistical inlier ratio using distance band.

Appendix A.5. Uniqueness

Voxel-based redundancy index using voxel size .

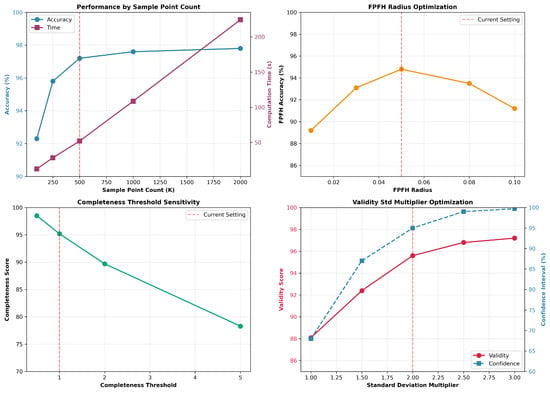

Appendix B. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

This appendix provides quantitative evidence underlying parameter selection:

- Sampling points (100 K–2 M): Optimal accuracy–speed balance at 500 K.

- FPFH radius (0.01–0.10): Peak stability at 0.05.

- Completeness thresholds (0.5–5 mm): Best discrimination at 1 mm.

- Validity -band (k = 1–3): k = 2 maximizes noise suppression.

- Voxel size (0.05–0.5): Best redundancy detection at 0.1.

Figure A1 summarizes these results through sensitivity plots.

Figure A1.

Parameter sensitivity analysis for sampling density, FPFH radius, completeness threshold, validity standard deviation range, and voxel size. The selected parameters (500K samples, radius = 0.05, threshold = 1.0 mm, , voxel size = 0.1) provide the best balance between accuracy, robustness, and computational efficiency.

Appendix C. Weight Distribution and Sensitivity Analysis

The selected weight distribution (10–30–20–20–20%) was validated through the following measures:

- Grid search over 50 weight configurations;

- Correlation analysis with expert-provided quality labels;

- Stability checks across 3000 real and 200 synthetic samples.

Figure A2 visualizes the adopted weight distribution.

Figure A2.

Visualization of adopted metric weights (accuracy 0.10, consistency 0.30, completeness 0.20, validity 0.20, uniqueness 0.20). The selected configuration showed the highest alignment with expert evaluation labels across 50 candidate weight settings.

Appendix D. Real Case Comparison

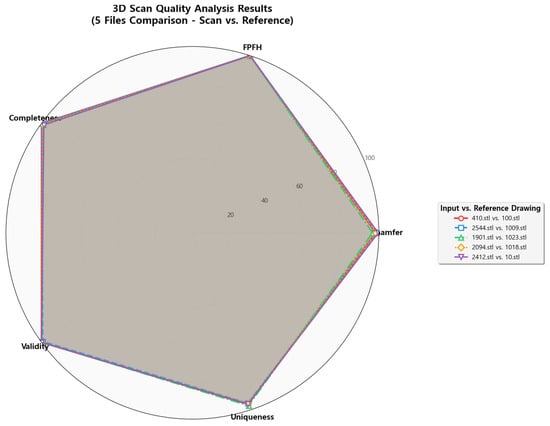

Radar-chart visualization shows consistent high-quality scores across ISO 25012 metrics for representative scan–reference pairs:

- 410.stl vs. 100.stl;

- 2544.stl vs. 1009.stl;

- 1901.stl vs. 1023.stl;

- 2094.stl vs. 1018.stl;

- 2412.stl vs. 10.stl.

Figure A3 summarizes the real inspection comparison.

Figure A3.

Radar-chart visualization comparing five representative scan–reference pairs across all ISO 25012 metrics. Metric variability remains within , demonstrating the robustness of the proposed scoring model under diverse manufacturing geometries.

Appendix E. Full Evaluation Table

This appendix provides the complete results used in Section 3, including

- Chamfer, FPFH, completeness, validity, uniqueness scores;

- Aggregated quality scores;

- Assigned quality grades (A–F).

The dataset is derived from the deployed model configuration and evaluation logs.

Appendix F. Threshold and Detector Ablation Experiments

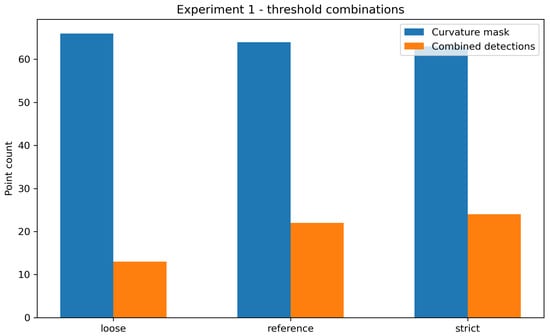

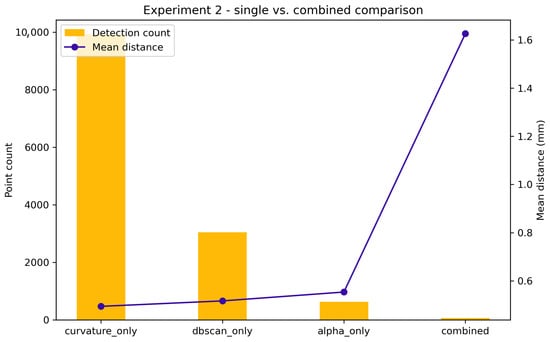

This appendix provides supplementary experiments supporting the final selection of curvature-, density-, and topology-based thresholds, as well as the justification for adopting a hybrid detector instead of single-modality alternatives. The outcomes are summarized in Figure A4 and Figure A5.

Figure A4.

Experiment 1: Comparison of loose, reference, and strict threshold configurations. The reference setting preserves stable DBSCAN clustering (60 clusters) and a consistent alpha-shape area, avoiding both the merging observed in the loose setting (28 clusters) and the fragmentation observed in the strict setting (107 clusters).

Figure A5.

Experiment 2: Comparison of single detectors with the hybrid detector. The hybrid method significantly reduces false positives (66 points vs. 9924 for curvature-only) while emphasizing structurally meaningful deviations (mean distance 1.626 mm).

Appendix F.1. Experiment 1: Threshold Combination Study

To evaluate the stability of curvature-, density-, and topology-based features under different parameter configurations, three joint threshold settings were examined: a loose configuration that prioritized higher recall, a strict configuration that enforced aggressive pruning, and a balanced reference configuration.

The loose setting produced 66 curvature-mask points but only 28 DBSCAN clusters, indicating under-segmentation due to merging of structurally distinct regions. The strict configuration retained 63 curvature-mask points but resulted in 107 DBSCAN clusters, fragmenting coherent areas into many small subregions. In contrast, the reference configuration maintained 60 stable clusters and produced 22 combined detections while keeping the alpha-shape area nearly constant (13,730.64 mm2). These results demonstrate that the chosen thresholds avoid over-merging and over-fragmentation while preserving geometric fidelity.

Appendix F.2. Experiment 2: Single vs. Hybrid Detector Comparison

A second experiment compared three single-modality detectors—curvature-only, DBSCAN-only, and alpha-only—against the proposed hybrid detector integrating curvature cues, density clustering, and topology-based boundary features.

The curvature-only detector produced 9924 detections, yielding excessive false positives; the DBSCAN-only detector yielded 3042 detections due to local density sensitivity; and the alpha-only detector produced 635 detections but failed to capture surface-type anomalies because it relies solely on boundary topology.

In contrast, the hybrid detector retained only 66 high-confidence detections, representing a nearly reduction relative to curvature-only, while increasing the mean deviation to 1.626 mm. This demonstrates that the hybrid approach effectively suppresses false positives while isolating structurally meaningful regions outside tolerance. Additionally, the DBSCAN cluster count remained stable at 60, showing that geometric structure is preserved during the filtering process.

References

- Besl, P.J.; McKay, N.D. A method for registration of 3-D shapes. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1992, 14, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, R.B.; Blodow, N.; Beetz, M. Fast Point Feature Histograms (FPFH) for 3D registration. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Kobe, Japan, 12–17 May 2009; pp. 3212–3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salti, S.; Tombari, F.; Di Stefano, L. SHOT: Unique signatures of histograms for surface and texture description. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2014, 125, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Sohel, F.; Bennamoun, M.; Lu, M.; Wan, J. Rotational Projection Statistics for 3D Local Surface Description and Object Recognition. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2013, 105, 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.R.; Yi, L.; Su, H.; Guibas, L.J. PointNet++: Deep Hierarchical Feature Learning on Point Sets in a Metric Space. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.02413. [Google Scholar]

- Younes, R.; Yaacoub, C.; El Khoury, G.; Possik, J.; Abi Zeid Daou, R. Evaluation of Point-MAE for Robust Point Cloud Classification Across Diverse Datasets. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Smart Systems and Power Management (IC2SPM), Beiruit, Lebanon, 28–29 November 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzahid, A.A.M.; Wan, W.; Sohel, F.; Wu, L.; Hou, L. CurveNet: Curvature-based multitask learning deep networks for 3D object recognition. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sinica 2021, 8, 1177–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 25012:2008; Software Product Quality Requirements and Evaluation—Data Quality Model. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- ISO 1101:2017; Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Geometrical Tolerancing—Tolerances of Form, Orientation, Location and Run-Out. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- ISO 8015:2011; Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Fundamentals—Concepts, Principles and Rules. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

- Segal, A.; Haehnel, D.; Thrun, S. Generalized ICP. In Robotics: Science and Systems; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umeyama, S. Least-Squares Estimation of Transformation Parameters Between Two Point Patterns. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1991, 13, 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.E.; Hebert, M. Using Spin Images for Efficient Object Recognition in Cluttered 3D Scenes. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1999, 21, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frome, A.; Huber, D.; Kolluri, R.; Bülow, T.; Malik, J. Recognizing Objects in Range Data Using Regional Point Descriptors. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2004, 3023, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Medioni, G. Object modelling by registration of multiple range images. Image Vis. Comput. 1992, 10, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombari, F.; Salti, S.; Di Stefano, L. Unique Shape Context for 3D Data Description. In Proceedings of the 3D Object Retrieval (3DOR’10), Firenze, Italy, 25 October 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Kim, E. New Compact 3-Dimensional Shape Descriptor for a Depth Camera in Indoor Environments. Sensors 2017, 17, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reuter, L.; Denkena, B.; Wichmann, M. Adaptive inspection planning using a digital twin for quality assurance. Procedia CIRP 2023, 120, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaram, S.; Zeid, A. Artificial Intelligence-Based Smart Quality Inspection for Manufacturing. Micromachines 2023, 14, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero, P.A.; López González, M.C.; García Valldecabres, J.L. Optimising Floor Plan Extraction: Applying DBSCAN and K-Means in Point Cloud Analysis of Valencia Cathedral. Heritage 2024, 7, 5787–5799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Ni, H.; Li, C.; Zou, Y.; Luo, Y. DefectGAN: Synthetic Data Generation for EMU Defects Detection With Limited Data. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 17638–17652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, R.B.; Cousins, S. 3D is here: Point Cloud Library (PCL). In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Shanghai, China, 9–13 May 2011; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soudarissanane, S.; Lindenbergh, R.; Menenti, M.; Teunissen, P. Scanning geometry: Influencing factor on the quality of terrestrial laser scanning points. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2011, 66, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wang, R.; Wang, Y.; Gao, G. Fast Method of Registration for 3D RGB Point Cloud with Improved Four Initial Point Pairs Algorithm. Sensors 2020, 20, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).