1. Introduction

The decision-making process is inherently complex and, when it involves multiple experts providing assessments of various alternatives to address a problem in order to arrive at a solution (or a series of solutions), it is referred to as group decision-making (GDM) [

1]. This process requires the aggregation of opinions within a dynamic environment influenced by the behaviors of experts, who often possess differing levels of knowledge regarding the alternatives being evaluated. Furthermore, these experts may approach the analysis from distinct perspectives, shaped by their individual experiences or expectations. Consequently, it is crucial to effectively manage the conflicts between differing opinions to ensure that all experts feel adequately represented in the ultimate decision [

2]. In this context, two fundamental challenges arise: the modeling of the judgments rendered by the experts and the evaluation of the quality of those judgments [

3].

To model evaluations in decision-making, various frameworks have been proposed [

4]. One such framework utilizes an ordered vector of alternatives, wherein the degree to which each alternative addresses a problem is assessed through a utility value. Alternatively, pairwise comparison may be employed to determine the preference degree of one alternative in relation to another. When applied iteratively, this method generates a preference relation, which is the most prevalent framework in decision-making due to its ability to facilitate accurate evaluations and streamline the aggregation of individual assessments into group evaluations—an aspect that is particularly critical in GDM scenarios [

5]. Nevertheless, this framework’s propensity to yield more information than necessary can lead to inconsistent evaluations. Such inconsistencies may stem from insufficient current knowledge and the intrinsic complexities associated with the GDM process. Because consistency has been recognized as a measure of rationality that enables performance evaluations, the quality of a preference relation can be gauged by its degree of consistency. Consequently, to ensure the validity of the outcomes, it is essential to maintain consistent preference relations [

6].

Within the realm of preference relations, one can identify fuzzy preference relations and multiplicative preference relations, both of which rely on numerical values [

7,

8]. Nevertheless, as decision-making is a fundamentally cognitive process, methodologies based on computing with words effectively bridge the gap between computational techniques and human reasoning [

9,

10]. These approaches have demonstrated considerable promise in enriching and formulating decision-making models that effectively manage qualitative information [

11]; for example, models of computing with words utilizing qualitative scales have been extensively applied to the management of linguistic information [

3]. Recently, novel models based on the granular computing framework have emerged to effectively address linguistic expressions [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Regardless of the specific model of computing with words, it is evident that linguistic information must be operationalized, as it does not possess inherent operational capability. In the context of models grounded in the granular computing framework, this operationalization is achieved through a process known as information granulation [

17]. In this framework, both the distribution and semantics of linguistic values are not predetermined; rather, they are established through an optimization process and, thus, are somewhat more feasible. This process entails the optimization of a suitable criterion through the effective mapping of linguistic values to a designated information granule family. Specifically, the distribution and semantics of linguistic values are typically modeled through a series of continuous intervals (information granules) that are established by assigning a vector of cutoff points within

. The process of allocating these cutoff points is usually determined as an optimization problem, where consistency and consensus are commonly employed as key performance indicators [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

18,

19].

The common characteristics of proposals based on the granular computing paradigm include the formulation of operational versions of linguistic terms in a manner that maintains consistent intervals across all experts—essentially assuming the same semantics for everyone involved. However, it is imperative to acknowledge that, in GDM contexts, words may possess distinct meanings for different individuals [

20,

21]. This consideration holds particular significance in environments such as social networks, where a diverse array of users interact and the same term can be interpreted in multiple ways [

22]. Traditional methodologies for computing with words frequently neglect this critical issue, either by avoiding direct engagement with it or by employing multi-granular linguistic models and type-2 fuzzy sets as remedial measures [

23,

24]. While these approaches may alleviate some of the ambiguity associated with word meanings, they do not sufficiently capture the unique semantics pertinent to each individual participant. To overcome this limitation, personalized individual semantics approaches were introduced, which utilize the 2-tuple linguistic model [

25] alongside numerical scales [

26,

27] to significantly enhance the specificity and relevance of interpretations within GDM frameworks [

28,

29,

30].

This study addresses a major gap in existing granular-computing-based linguistic decision-making models; namely, their assumption of uniform semantics across experts. Such an assumption disregards the fact that linguistic terms often carry different meanings for different individuals, which limits the accuracy and fidelity of collective decisions. To overcome this limitation, we propose a novel approach that personalizes linguistic semantics by integrating granular computing with the 2-tuple linguistic model. The central contribution of this work lies in enabling expert-specific interpretations of linguistic terms within a formal computational structure, thus enhancing both the coherence and representativeness of group decisions.

Therefore, the main research goal of this study is to develop a novel group decision-making model that personalizes the semantics of linguistic terms by integrating the granular computing paradigm with the 2-tuple linguistic model. Specifically, our objective is to operationalize individual linguistic preferences through personalized information granules, generated by optimizing the consistency of each expert’s 2-tuple linguistic preference relation. In this way, we aim to overcome the limitations of existing granular computing approaches that assume uniform linguistic semantics among experts, ultimately providing a more accurate, interpretable, and expert-aligned framework for linguistic GDM.

The proposed method is evaluated through a dual strategy that combines quantitative and comparative analysis. First, we measure the improvement in experts’ consistency levels after the optimization of symbolic translations, thereby providing a numerical indicator of the method’s effectiveness in enhancing the rationality and coherence of linguistic preference relations. Second, we conduct a comparative study against representative granular-computing-based linguistic decision-making approaches, demonstrating that our model achieves superior consistency and produces collective outcomes that more faithfully reflect individual semantic interpretations. Together, these two complementary perspectives confirm the robustness and practical relevance of the proposed approach.

The rest of this manuscript is structured as follows.

Section 2 provides essential foundational knowledge necessary for comprehending our proposal, including the description of the 2-tuple linguistic model, the definition of a GDM problem in 2-tuple linguistic contexts, a methodology for determining individual consistency within a 2-tuple linguistic preference relation, and an exposition of the Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm.

Section 3 elaborates on our innovative GDM approach, which employs granular computing and the 2-tuple linguistic model to personalize linguistic information.

Section 4 presents a real-world case study that exemplifies the proposed GDM model, accompanied by a comparative analysis to emphasize its key features in

Section 5. Lastly,

Section 6 concludes with a summary of our findings and recommends potential directions for future research.

3. Methodology: A Group Decision-Making Approach Based on Personalized Linguistic Information

In this section, we present a novel methodology for modeling and facilitating processes of GDM within linguistic contexts. Leveraging a framework of granular computing, we personalize the linguistic values derived from the preference degrees articulated by experts. Before undertaking the aggregation and exploitation phases of the selection process, it is essential to transform the linguistic values from these preference relations into an operational format through a structured granulation process. This transformation is pivotal, as it converts subjective linguistic inputs into quantifiable data suitable for further analysis. The result of this granulation process is an operational framework that enables the effective processing of data, ultimately yielding a comprehensive ranking of the available alternatives. This ranking is in alignment with the linguistic values communicated by the experts, ensuring that their insights are accurately represented and integrated into the decision-making process.

The precise definition of linguistic values is closely associated with the structured development of a collection of information granules. In this study, we advocate for an innovative approach that departs from previously explored methodologies by articulating the granulation of linguistic information through the framework of the 2-tuple linguistic model instead of intervals [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

18,

19]. This process encompasses four significant characteristics that enhance its effectiveness:

Retention of semantic meaning. The process meticulously preserves the meanings of the linguistic values that are distributed throughout the granulation phase. This ensures that the core ideas and concepts conveyed by the language remain intact, facilitating a deeper understanding among users.

Representation of information based on the 2-tuple linguistic model. Each granule of information is represented as a pair consisting of a linguistic term and a corresponding numerical value. The linguistic term reflects the qualitative aspect of the information, while the numerical value quantifies the term’s significance. This dual-format representation not only enhances the precision and clarity of the conveyed linguistic information but also enables more effective communication and thorough analysis in a variety of applications, such as decision-making, data interpretation, and modeling.

Recognition of subjective meaning. The process recognizes the subjective nature of language by acknowledging that the same words may convey different meanings to different individuals. It entails a distinct treatment of the linguistic values supplied by the experts involved in the process, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of varying perspectives and interpretations.

Operationalization of linguistic values. The process operationalizes the linguistic values by modeling them as linguistic 2-tuples. This is achieved by formulating a specific optimization problem aimed at maximizing consistency concerning the 2-tuple linguistic preference relations. This step is crucial as it provides a structured approach to handling linguistic information, ensuring that the final outcomes align closely with the diverse preferences and judgments of the experts.

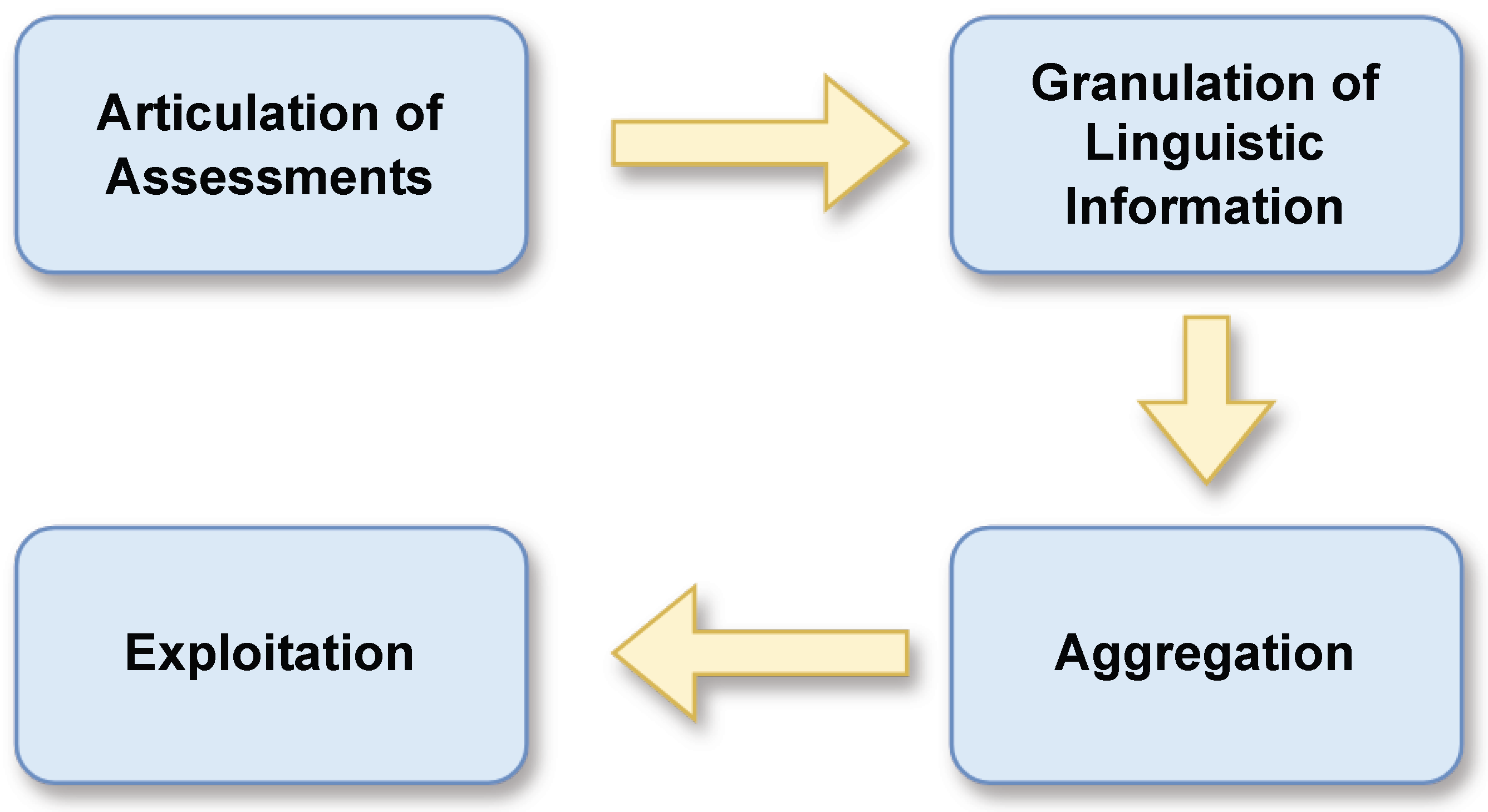

It is worth highlighting that the methodological process described in this section is fully implemented throughout the development of the proposed approach. Each phase of the Design Science Research methodology is explicitly addressed and executed in the subsequent sections, ensuring that the complete Design Science Research cycle is rigorously fulfilled within our model. In the following subsections, we provide a detailed examination of the four distinct phases involved in the proposed GDM approach. These phases are: (i) articulation of assessments, where experts clearly express their evaluations and opinions regarding the decision at hand; (ii) granulation of linguistic information, which involves breaking down and categorizing the qualitative data gathered from the assessments to capture the nuances of experts’ insights; (iii) aggregation, where the individual assessments and granulated information are systematically combined to form a cohesive group perspective; and (iv) exploitation, which focuses on utilizing the aggregated information to inform decision-making and action, ensuring that the outcomes align with the group’s collective goals and objectives. Each phase plays a critical role in enhancing the overall effectiveness of the GDM process. To improve the comprehensibility of the proposed approach, a graphical representation of the method has been incorporated (see

Figure 1). This diagram summarizes the full workflow, including the articulation of experts’ assessments, the granulation of linguistic information through personalized symbolic translations, the aggregation of 2-tuple linguistic preference relations, and the final exploitation phase. The graphical overview enables readers to visualize the sequence, interdependence, and purpose of each stage, thereby enhancing the interpretability and accessibility of the model.

3.1. Articulation of Assessments

The first phase is dedicated to the systematic collection of assessments from a panel of experts, using linguistic pairwise comparisons to articulate their preferences. In this context, we consider a group consisting of

m experts, denoted as

, where the index

h varies from 1 to

m. Each expert is tasked with evaluating a set of

n alternatives, represented as

, where the index

i ranges from 1 to

n. In addition, we utilize a comprehensive set of linguistic values, labeled as

, with

l ranging from 0 to

g, to facilitate nuanced comparisons. A linear order ≺ between the linguistic values is assumed, where

, if

(

, then

determines a greater degree of preference than

. During this phase, each expert

constructs a linguistic preference relation, designated as

. This relation comprises their pairwise comparisons between the alternatives, expressed through the predefined linguistic values

. These comparisons allow for a qualitative assessment of the alternatives based on the experts’ subjective judgments, which can capture the nuances of their preferences more effectively than numerical ratings alone [

3]. This approach not only enhances the clarity of the decision-making process, but also ensures that the collective insights of the experts are integrated cohesively.

3.2. Granulation of Linguistic Information

Prior to commencing the selection process (aggregation and exploitation), it is imperative to operationalize the linguistic values derived from the linguistic preference relations, and this is the objective of this second phase. Linguistic values utilized in the pairwise comparisons offered by the experts, in their inherent nature, are non-operational, indicating that further processing or analysis cannot be performed on them in their current state. Consequently, these linguistic values necessitate a procedure known as granulation, which involves the transformation of these values into structured entities referred to as information granules [

40]. This process facilitates enhanced understanding and manipulation of the associated data.

The granular definition of linguistic values is fundamentally linked to the realization of a structured set of information granules. This study investigates the granulation of linguistic information through the framework of the 2-tuple linguistic model [

25], which facilitates a more formal representation of linguistic nuances, suggesting that information granules are conveyed as linguistic 2-tuples. By employing this model, this study aims to improve clarity and effectiveness in communication, particularly in contexts characterized by imprecise or fuzzy information. Moreover, consistency is fundamental in formalizing linguistic values into linguistic 2-tuples because when consistency levels are elevated, the quality of solutions derived from decision-making processes tends to improve significantly. Additionally, the concept of consistency facilitates the personalization of individual semantics. Experts assign their unique interpretation and meaning to linguistic values based on their preferences, which is inherently linked to their level of consistency. This individual semantic framework reflects how personal experiences and understanding shape the assessment of linguistic values. Given these critical insights, this study also leverages consistency as an essential criterion for optimization. By focusing on consistency, we aim to enhance GDM processes and outcomes, ensuring that they are not only accurate but also aligned with individual preferences and interpretations.

In the context of optimizing the criterion, various strategies may be employed to enhance the process. Nevertheless, PSO has consistently demonstrated its efficacy in addressing such optimization challenges [

12,

13], making it the preferred method for this task. This algorithm is fundamentally composed of two critical components: the definition of the particle and the fitness function utilized to evaluate the particle’s quality.

Regarding the particle definition, we employ a modeling approach that utilizes a vector of symbolic translations, specifically constrained to the interval . These symbolic translations play a critical role in delineating how specific 2-tuple linguistic values are assigned to their corresponding linguistic terms during the transformation process. To elaborate on this, consider a scenario involving a set of linguistic terms used by three experts . Although these experts may refer to the same set of linguistic terms, their interpretations may vary due to their individual backgrounds, expertise, and perspectives. As a result, this diversity of interpretation can lead to the emergence of distinct 2-tuple linguistic values for identical terms. This phenomenon underscores the significance of acknowledging the subjective nature of language and the complexities that arise when various experts strive to convey similar concepts through linguistic expressions. Therefore, for each expert , , a different mapping is formed: , , , , , being , , , , and , the symbolic translations for the expert . In particular, if we consider linguistic values and m experts, each particle is composed of symbolic translations. Then, each particle is modeled as in this particular example.

With respect to the definition of the fitness function

f, the objective is to maximize the consistency level associated with the 2-tuple linguistic preference relations formed according to the symbolic translations contained in the particles. Consequently, the fitness function is defined as follows:

where

determines the consistency level of the 2-tuple linguistic preference relation

associated with the linguistic preference relation

expressed by the expert

and whose value is calculated according to Equation (

13).

In this framework, PSO seeks to maximize the values of the fitness function by refining the locations of the symbolic translations. This process entails the modification of symbolic translations associated with 2-tuple linguistic values while ensuring the preservation of the original linguistic terms provided by experts.

Although the proposed approach requires optimizing symbolic translations for all linguistic terms across all experts, the computational burden of the PSO stage remains moderate. The dimensionality of the optimization problem is defined by

, which in typical GDM settings results in a relatively small number of decision variables. PSO exhibits rapid convergence in continuous, low-dimensional search spaces, and in our experiments the optimization process consistently stabilized within fewer than 300 iterations. For the case study presented in

Section 4, using a population of 100 particles, the average runtime of the PSO procedure was below one second on a standard

GHz processor. This confirms that the personalization step introduces negligible computational cost relative to the overall GDM workflow. Moreover, once the optimal symbolic translations are obtained, no further optimization is required in subsequent stages, ensuring that the method remains scalable and efficient for practical applications.

3.3. Aggregation

In this phase, the objective is to establish a collective preference relation that effectively synthesizes the linguistic pairwise comparisons articulated by the group of experts. We begin with a set of m individual 2-tuple linguistic preference relations, denoted as . Each of these relations encapsulates the subjective preferences of the experts concerning a variety of alternatives.

To consolidate this information, it is necessary to derive a collective 2-tuple fuzzy linguistic preference relation, represented as . This process requires the implementation of an aggregation procedure that integrates the individual preferences into a unified framework. Each value is defined to reside within the set , wherein it quantitatively represents the extent of preference that alternative has over alternative . In this study, this representation reflects the consensus reached among the most consistent experts, capturing a coherent collective judgment.

To facilitate a robust aggregation of the experts’ opinions, a 2-tuple linguistic Ordered Weighted Averaging (OWA) operator is employed. This operator not only assists in combining the individual preferences but also accommodates the varying levels of significance attributed to each expert’s opinion. By utilizing this methodology, the final collective 2-tuple linguistic preference relation is constructed to meaningfully reflect the group’s overall assessment, while preserving the nuances of the linguistic evaluations provided.

Definition 4 ([

32])

. “A 2-tuple linguistic OWA operator of dimension n is defined as a function , that has a weighting vector associated with it, , with , :being a permutation defined on 2-tuple linguistic values, such that , ; i.e., is the i-highest 2-tuple linguistic value in the set .” An important consideration in the definition of an OWA operator is the method for deriving its weighting vector. In the work of Yager [

41], a specific mathematical expression was introduced to compute it:

Equation (

18) is significant because it allows for representation of the fuzzy majority concept, which reflects the idea of collective decision-making based on fuzzy logic [

42]. Furthermore, it utilizes a fuzzy linguistic non-decreasing quantifier

Q, which systematically categorizes and ranks values in a way that preserves their order [

43]. This approach enhances the OWA operator’s flexibility and applicability in various contexts where uncertainty and imprecision are inherent.

The 2-tuple linguistic OWA operator overlooks the varying significance of individual experts in decision-making processes. However, a logical and fair assumption when addressing GDM problems is that greater importance should be assigned to those participants communicating the most consistent and reliable information. This approach acknowledges that GDM scenarios are inherently heterogeneous, meaning the contributions of experts can differ significantly in terms of reliability and relevance [

12].

The incorporation of importance values into the aggregation process typically requires the transformation of preference values, designated as

, using a corresponding importance degree

I. This transformation results in new values, indicated as

[

44,

45]. The process is executed through a defined transformation function

t, expressed as

[

45]. An alternative approach that merits consideration involves utilizing importance or consistency degrees as the order-inducing values within the Induced Ordered Weighted Averaging (IOWA) operator, formalized as an extension of the OWA operator [

46]. This extension facilitates a distinct reordering of the values intended for aggregation, thus allowing for greater flexibility in decision-making and enhancing the accuracy of the aggregation process based on the specific context and criteria involved. By implementing this methodology, the aggregation of preferences can more accurately reflect varying levels of importance and consistency among the criteria under consideration.

Definition 5 ([

32])

. “A 2-tuple linguistic IOWA operator of dimension n is a function:being σ a permutation of such that , ; i.e., is the linguistic 2-tuple with the i-th highest value in the set .” In Definition 5, the reordering of the set of values designated for aggregation,

, is dictated by the reordering of the corresponding values

, which is based on their magnitudes. This utilization of the set of values

has led to classify them as the values of an order-inducing variable, which corresponds to the argument variable [

46].

In this context, to derive the corresponding weighting vector, Yager proposed a methodology for assessing the overall satisfaction associated with

Q significant criteria

or experts

regarding the alternative

[

47]. This methodology involves ordering the satisfaction values intended for aggregation, after which the weighting vector linked to an IOWA operator that employs a linguistic quantifier

Q is calculated according to:

where

denotes the total sum of importance, with

representing the permutation applied to order the values for aggregation. This methodology for integrating importance degrees allocates a weight of zero to any experts whose importance degree is zero. In our analysis, we employ the consistency levels of the 2-tuple linguistic preference relations to derive the importance degrees related to each expert.

Definition 5 facilitates the creation of various operators. Notably, the set of consistency levels associated with the preference values,

, can be employed to define an IOWA operator. The aggregation of the preference values, denoted as

, can be achieved by ranking the experts according to their consistency, from the most consistent to the least consistent. This method produces an IOWA operator,

, which is the additive-consistency 2-tuple IOWA operator and can be regarded as an extension of the AC-IOWA operator [

48]. Consequently, the formulation of the collective 2-tuple linguistic preference relation is:

In Equation (

21),

Q represents the fuzzy quantifier used to implement the fuzzy majority concept, and through Equation (

20) to compute the weighting vector of the

operator.

3.4. Exploitation

In this phase, we leverage the information derived from the collective 2-tuple linguistic preference relation to systematically rank the available alternatives. The objective is to identify the “best” decision(s) that are most widely accepted among the most consistent experts within the group. To accomplish this, we can employ two established methods for assessing the degree of preference for each alternative. These methods, as discussed by Herrera-Viedma et al. [

49], utilize OWA operators and incorporate the concept of fuzzy majority:

The Quantifier-Guided Dominance Degree (

). It is a metric that assesses the level of dominance one alternative possesses over others within a fuzzy majority context. This metric is defined through a specific mathematical framework that encapsulates the complexities of dominance in decision-making processes characterized by uncertainty and imprecision. By employing this approach, one can gain a deeper insight into the relationships among various alternatives, taking into account not only explicit preferences but also the nuanced comparative advantages that may arise in a fuzzy environment. It is defined as:

The Quantifier-Guided Non-Dominance Degree (

). It serves as a metric to assess the extent to which each alternative remains unaffected by the influence of a fuzzy majority among the remaining alternatives. This concept is essential in decision-making contexts, as it helps in identifying alternatives that maintain their uniqueness and value, despite the presence of other competitive options. The non-dominance degree is defined in the following manner:

where

and

represents the degree in which

is strictly dominated by

, which is computed as:

The application of choice degrees over X can be executed through two principal policies: the sequential policy and the conjunctive policy. Consequently, within the framework of a comprehensive selection process, the implementation of choice degrees occurs in three distinct steps:

Applying each choice degree of alternatives over

X to generate two sets of alternatives:

whose elements referred to as maximum dominance elements in the fuzzy majority of

X, quantified by

Q, and maximal non-dominated elements in the fuzzy majority of

X, also quantified by

Q, respectively.

Applying the conjunction selection policy to produce this collection of alternatives:

When , the process finishes. Otherwise, it continues.

Applying one of the two sequential selection policies, according to either a dominance or non-dominance criterion:

Dominance-based sequential selection process. Applying the

over

X to generate

. When

, the process finished and this is the solution set. Otherwise, it continues producing:

It is the solution.

Non-dominance-based sequential selection process. Applying the

over

X to produce

. When

, the process finishes and this is the solution set. Otherwise, it continues obtaining:

It is the solution.

4. Case Study

This section delineates a case study focused on the conversion of a non-residential building into a residential structure, based on the proposed methodology. The building under examination was constructed prior to 1917 and underwent reconstruction in 2019 under the purview of LLC “Engineering and Construction.” It is located on Nizhniy Val Street in the Podilskyi district of Kyiv, an area characterized by dense urban development and recognized as a central historical territory, which is also designated as an archaeological protection zone [

50]. The primary objective of this study is the reconstruction of three floors of an eight-story brick building, which features a distinctive gabled roof covered with metal tiles. The maximum dimensions of the building are 46.94 m in length and 9.4 m in width. The structural framework comprises load-bearing interior and exterior walls made of brick, along with monolithic sections supported by metal beams, wooden beams, and a cork flooring system. The partitions within the building are also constructed from brick.

The project entails the exterior enhancement of the house, which includes the installation of metal–plastic windows, the implementation of a ventilation system (including air conditioners), as well as the integration of a water supply system and heating system, all in accordance with the specified project guidelines. It is important to note that the project does not entail the involvement or relocation of any existing structures situated on the design site, nor does it permit the removal of existing greenery.

A single, fully detailed case study was selected because the purpose of this article is not to perform a broad empirical comparison but to illustrate, step by step, how personalized linguistic semantics are operationalized within the proposed granular computing-based GDM model. Using multiple case studies would significantly increase the manuscript length without providing additional methodological insight. The chosen building refurbishment scenario offers a real-world, data-rich environment involving multiple experts and conflicting linguistic assessments. Within this context, we decided to focus specifically on the ventilation system because it is the subsystem that most clearly reflects the multidimensional nature of linguistic evaluations. Criteria such as noise level, airflow efficiency, durability, and cost often generate divergent expert judgments due to professional background and experience. This makes ventilation an ideal example to demonstrate the usefulness of personalized semantic granulation. Other systems exhibit less semantic variability or fewer conflicting criteria, and therefore provide less illustrative value for showing the strengths of the proposed approach. According to the project case study, the systems for water supply, heating, ventilation, windows, and roofing necessitate renovation within the building. However, this analysis focuses specifically on the ventilation component.

The ventilation system in the residential building incorporates both natural and mechanical methods. Currently, the building features REHAU S710 profile plastic windows, which have deteriorated over time, leading to sub-optimal ventilation conditions. To comply with the air quality parameters established by current regulations, the design includes supply and exhaust ventilation systems with mechanical assistance. The capacity of these ventilation systems is determined by the normative air exchange rates on a per capita basis. Furthermore, the project includes provisions for the installation of outdoor air conditioning units. The air ducts are constructed from galvanized sheet steel.

Subsequently, an analysis is conducted to assess the significance, utility, and priority of the renovated ventilation system. The ventilation project will be developed based on defined initial data:

The estimated air circulation in both general and auxiliary rooms is determined based on the required air exchange standards. In areas where harmful air is present, the design accounts for adequate circulation to ensure its removal. The amount of outdoor air needed in administrative spaces is calculated in accordance with DBN B.2.5-67:2013 [

51]. In parking lots, the air supply is concentrated in the driveway, while air extraction is evenly distributed between the lower and upper zones. Ventilation equipment for the parking area is installed within the ventilation chambers of the basement. It is important to note that exhaust air will exceed the supply according to item 8.39 of DBN B.2.3-15-2007 [

52]. In administrative rooms, ventilation system productivity is intentionally reduced to a single air exchange during non-working hours to conserve energy resources. Supply and exhaust air ducts are routed concealed within ventilation shafts and behind architectural structures. These ducts are made from galvanized steel as per GOST 19904-74 [

53] and adhere to the density class specified in DBN B.2.5-67-2013 [

51].

Exhaust emissions in architectural mines are managed through exhaust holes positioned 1.0 m below the roof. Air intake is set at 2.0 m above ground, with a minimum separation of 8.0 m between intake and outlet. To minimize ventilation noise, pumps and fans are installed on vibration-insulating bases, fans and ducts are connected with flexible inserts, and mufflers are used.

The ventilation systems of five companies were evaluated using four indicators: maximum pressure, price, durability, and level of noise. The selected companies were BHTC (Ukraine,

), VIKMAS LTD (Ukraine,

), BT-Service (Ukraine,

), KERMI (Germany,

), and Danfoss (Denmark,

). Four ventilation specialists provided their preferences using the linguistic term set

, being

“Much Worse” (

),

“Worse” (

W),

“Equal” (

E),

“Better” (

B), and

“Much Better” (

). The linguistic preference relations given were:

Following the collection of linguistic preference relations from the four ventilation specialists, we utilized the information granulation approach described in

Section 3.2 to personalize and operationalize the linguistic values.

The parameters for the PSO framework were determined through extensive experimentation. A swarm size of 100 particles was selected, as this configuration yielded consistent results across multiple runs. The number of generations was fixed at 300 because no further improvement in fitness function values was observed beyond this threshold. Both

and

were set to 2 in accordance with established practices in the literature [

39]. The inertia weight

was programmed to decrease linearly from

to

. The PSO returned the following vector of symbolic translations:

Each expert’s linguistic values are mapped to the following 2-tuple linguistic values based on the elements of this vector:

It means the linguistic preference relations initially expressed by the four ventilation specialists are converted into the following four 2-tuple linguistic preference relations:

The 2-tuple linguistic preference relations are aggregated using the

operator. The consistency degree of the linguistic preference values serves as the order-inducing variable. For aggregation, the linguistic quantifier “most of,” modeled as

, is employed. By applying Equation (

20), a weighting vector with four values is generated to calculate the collective 2-tuple linguistic preference relation:

For instance,

is calculated as:

where:

and where the weighting vector

has been calculated considering that

and:

Utilizing again the linguistic quantifier “most of” and Equation (

18), the weighting vector

obtained is:

The quantifier-guided dominance and non-dominance degrees,

and

, of all the alternatives are:

The maximal sets are

and, therefore, applying the conjunction selection policy we get:

It means that, according to “most of the” most consistent experts, the best company to provide the ventilation systems is BHTC ().

5. Comparative Analysis

Several concurrent research lines address related challenges in linguistic group decision-making, including granular-computing-based approaches that optimize linguistic intervals, multi-granular linguistic models, and type-2 fuzzy frameworks designed to capture semantic variability. To position our contribution within this landscape, we compare the proposed upgrade with representative methods from these lines of research. While existing approaches either assume common semantics, model linguistic terms through intervals, or use complex type-2 structures, our method distinguishes itself by directly personalizing the symbolic translation of each linguistic value using an optimization-driven mechanism. This personalization yields higher consistency levels and more faithful semantic alignment with individual experts. The comparison confirms that the proposed model constitutes a substantive methodological improvement over existing upgrades.

To analyze the performance of the proposed approach, denoted as personalized-approach, we consider one method where linguistic values are directly converted into 2-tuple linguistic values by setting the symbolic translations to 0, denoted as direct-approach. We also consider a method where a unified realization is carried out, so all linguistic values are converted into the same 2-tuple linguistic values for all experts, denoted as unified-approach. We conduct an experiment in which 100 randomly generated GDM problems are used. These problems vary in the number of alternatives, experts, and linguistic terms.

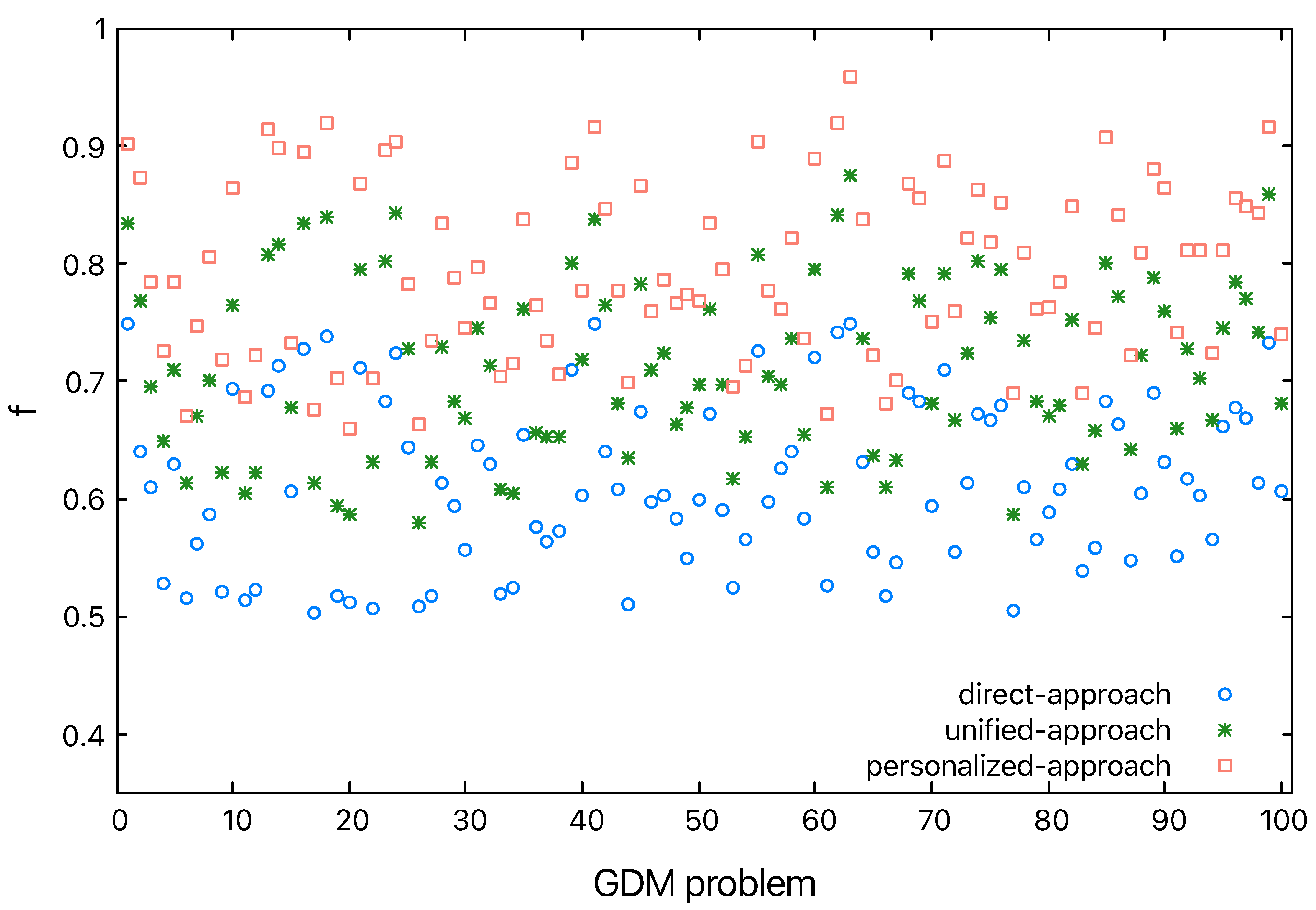

Figure 2 shows the value of the optimization criterion

f (global consistency level) achieved by each approach. The values for the granular approaches (the unified-approach and personalized-approach) are clearly higher than those for the direct-approach. This suggests that granular approaches can operationalize linguistic values and enhance consistency. Additionally, the values from the personalized-approach are higher than those from the unified-approach. This result verifies the superiority of the proposed approach, which achieves greater consistency levels by personalizing the semantics of the linguistic values.

To verify if the rankings of the alternatives produced by the direct-approach, the unified-approach, and the personalized-approach are different in the 100 GDM problems randomly generated previously, let

,

, and

be the rankings these approaches yield. These rankings are obtained after applying the aggregation and exploitation phases described in

Section 3, where the

is utilized to generate the rankings. Again,

is used to represent the linguistic quantifier “most of”, which is utilized in Equations (

18) and (

20) to produce the weights of the OWA and the additive-consistency 2-tuple IOWA operators. The

-norm distances between

and

, and between

and

, are calculated. These distances measure the decision discrepancies between the direct-approach and the personalized-approach,

, and between the unified-approach and the personalized-approach,

, respectively:

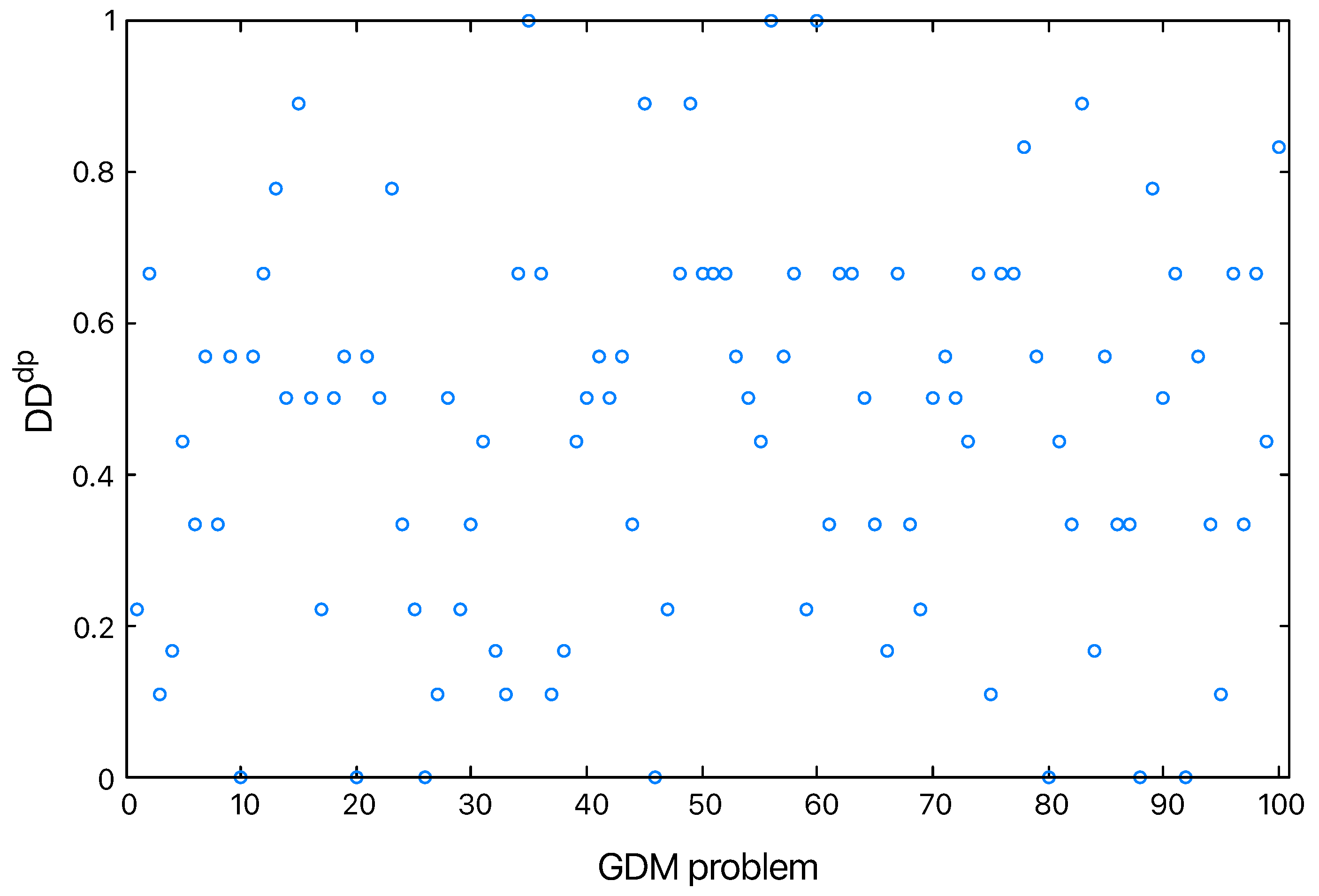

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 highlight the differences in decisions reached by the direct-approach and the personalized-approach, and between the unified-approach and the personalized-approach, respectively. Most decision discrepancy values are greater than 0, especially when compared with the direct-approach (see

Figure 3). Only a few GDM problems show no discrepancy at all. This demonstrates that the personalized-approach often leads to distinct outcomes compared with the other methods.

6. Concluding Remarks

In this study, we introduced a new approach using a granular computing framework to personalize linguistic information in GDM processes. We described the granulation of personalized linguistic information and its optimization using the PSO technique. Unlike existing approaches based on granular computing for computing with words, it formalizes each linguistic value through a personalized linguistic 2-tuple (information granule). The case study and the numerical experiments carried out demonstrated the performance and effectiveness of the proposed approach to solve GDM processes. In comparison with the granular approach based on a unified realization of the linguistic values, we showed that the proposed granular approach enables the personalization of linguistic values, resulting in higher consistency levels. Furthermore, it accounts for the possibility that linguistic values may convey slightly distinct meanings, even when utilized by all experts. Building on these critical insights, the proposed approach can improve GDM processes and decisions, ensuring both accuracy and alignment with individual understandings and preferences.

We propose to advance this research in two directions. Previously, we assumed all experts use a single linguistic label to state preferences between alternatives. However, single linguistic terms often fail to capture the depth of expert knowledge, making it necessary to develop richer, easily interpretable linguistic expressions that convey more nuanced information, such as extended comparative linguistic expressions with symbolic translation [

54]. Additionally, our focus has been on the consistency of individual experts, but the collective agreement among their preferences must also be addressed. The consensus-reaching process is essential in GDM models and has been widely studied in similar contexts. Thus, a GDM model that integrates a consensus-reaching process for personalized linguistic values should be developed.

Although the proposed approach demonstrates strong capabilities for personalizing linguistic semantics in GDM environments, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the method relies on the optimization of symbolic translations through PSO, whose performance may depend on parameter settings or population size, even though the computational effort is modest. Second, the approach assumes that experts provide complete linguistic preference relations; scenarios involving incomplete or missing evaluations are not addressed in this version of the model. Third, the personalization of linguistic semantics is performed independently for each expert, which may limit the integration of shared semantic structures in very large groups. Finally, the method was tested on a single real-world case study to illustrate its functioning; thus, broader empirical validation in diverse domains would be beneficial. These aspects open several avenues for future research, including the extension to incomplete linguistic information, hybrid optimization schemes, and large-scale experimental analysis across heterogeneous decision-making scenarios.