Abstract

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have emerged as a pivotal technology for enhancing the agility and resilience of future wireless networks. However, conventional optimization approaches remain predominantly reactive, relying solely on current network conditions for decision making. This proves to be inadequate for handling sudden traffic surges in dynamic environments, resulting in suboptimal service quality. To address this limitation, this paper proposes a novel joint optimization framework integrating spatiotemporal traffic prediction. This equips UAVs with predictive capabilities, thereby facilitating a paradigm shift from passive response to proactive service provision. The main contributions of this work are fourfold: First, a novel closed-loop optimization framework is introduced, deeply integrating an advanced traffic-forecasting module with a communication resource optimization module to provide a systematic, forward-looking decision-making solution for UAV-assisted communications. Second, a cellular traffic predictor based on Gaussian mixture model meta-learning (GMM-ML) is designed. This model effectively captures the periodicity and heterogeneity of traffic data, enabling the precise prediction of future hotspot areas and resolving the challenge of accurate forecasting under small-sample conditions. Third, a long-term discounted mixed-integer nonlinear programming (MINLP) problem model is formulated. This innovatively incorporates a “service readiness reward” for predicted hotspots within the objective function to achieve long-term performance optimization. Fourth, an efficient and convergent predictive iterative association and location optimization (P-IALO) algorithm is developed. Utilizing block coordinate descent and continuous convex approximation techniques, this algorithm decomposes the original complex problem to alternately optimized subproblems of user association and trajectory planning, guaranteeing algorithmic convergence. To validate the effectiveness of the proposed framework, large-scale simulation experiments were conducted using real-world traffic data. The results demonstrate that compared to traditional reactive algorithms, the proposed scheme significantly enhances the overall system throughput by 12%, improves user QoS satisfaction by 9.4%, and reduces service interruptions by 34.2%. Concurrently, the algorithm exhibits favorable convergence speed and robustness, maintaining performance advantages even under predictive errors. Extensive experimentation thoroughly demonstrates the efficacy of this research in enhancing the performance of drone-assisted networks.

1. Introduction

With the rapid advancement of fifth-generation (5G) and emerging sixth-generation (6G) mobile communication networks [], user demand for high-speed, low-latency, and reliable communications continues to grow []. Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), leveraging their high maneuverability, low-cost deployment, and flexible line-of-sight (LoS) link advantages, have emerged as a pivotal technology for augmenting terrestrial cellular networks, enhancing network capacity and coverage [,]. However, within dynamically evolving network environments, intelligently deploying UAVs and associating them with users to optimize the overall network performance remain significant challenges [].

Extensive research has focused on optimizing UAV-assisted communications, primarily addressing the co-optimization of user association and UAV trajectory planning. Pioneering studies based on iterative optimization and convex approximation techniques have significantly advanced in enhancing instantaneous network performance. However, these strategies are inherently limited by their reactive nature. Their resource allocation optimization relies solely on the current network state, lacking the ability to anticipate future traffic demands. This reactive approach often leads to delayed responses to traffic surges, unnecessary drone movements, and frequent handover switching, ultimately compromising both quality of service (QoS) and network efficiency. Concurrently, while recent studies have begun exploring spatiotemporal traffic forecasting using deep learning models, such as LSTMs and GNNs, the seamless integration of these predictions into practical drone decision-making loops remains an unresolved challenge. A critical gap remains in effectively translating accurate forecasts into proactive, long-term optimization decisions.

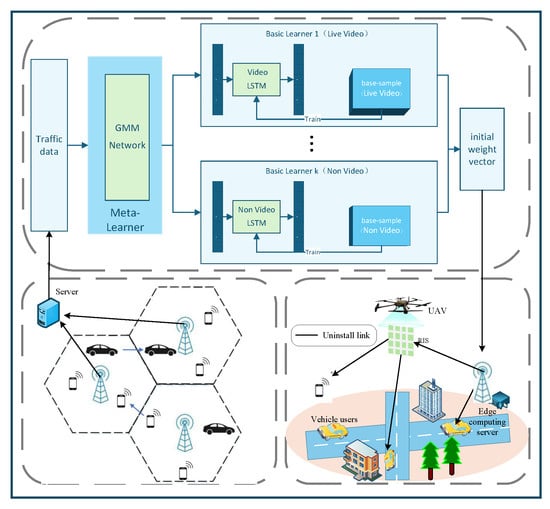

To bridge this gap, this paper introduces a spatiotemporal traffic prediction mechanism []. Its core concept involves accurately forecasting future user demand distributions based on historical data, enabling drone optimization strategies to not only rely on current network states but also anticipate future network conditions [,,]. This allows drones to preemptively relocate to positions better suited to serve future demands [,,,]. This “predict–optimize” closed-loop framework holds promise for significantly reducing service interruption probabilities and enhancing long-term system performance. The framework architecture is illustrated in Figure 1. Real-world network traffic is aggregated and processed before being uploaded to a server. The server hosts a cellular network traffic prediction module that assigns appropriate initial weight vectors to each cellular network, enabling targeted traffic forecasting for each. Drones utilize the prior knowledge generated by this traffic prediction module to provide targeted auxiliary communications in overloaded areas, thereby reducing the probability of service termination and enhancing service quality.

To validate this approach, we construct a rigorous mathematical optimization framework. This framework integrates two advanced techniques: First, a cellular traffic prediction model based on Gaussian mixture model meta-learning (GMM-ML) is used to accurately forecast future traffic hotspots across base stations []; second, a joint optimization algorithm is used for drone trajectories and user association based on mixed-integer nonlinear programming (MINLP). By translating predictive insights into objective functions and constraints within the optimization problem, we guide drones to perform anticipatory maneuvers. Simulation results confirm that the proposed framework achieves faster convergence and superior robustness in highly dynamic scenarios compared to conventional reactive methods.

The principal contributions of this paper comprise four aspects:

- A holistic closed-loop forward-looking optimization framework is proposed. This framework tightly couples the spatiotemporal traffic prediction module with the communication resource optimization module, enabling the genuine predeployment of unmanned aerial vehicles;

- An integrated traffic-forecasting model. We introduce a GMM-ML model based on Gaussian mixture models for cellular network traffic prediction. This model excels in handling task heterogeneity and few-shot learning scenarios, achieving highly accurate and robust forecasting of future traffic hotspots by extracting frequency-domain meta-features;

- Formulation of a long-term performance optimization problem and design of an efficient solution algorithm. We model the active UAV deployment problem as a long-term discounted mixed-integer non-convex optimization problem. To address this complexity, we designed the P-IALO algorithm, which decomposes the problem effectively and employs iterative BCD and SCA solutions to ensure convergence and practicality;

- Comprehensive simulation validation and analysis were conducted. Through extensive simulations calibrated with real-world data, we validated the significant advantages of our approach over existing reactive and predictive benchmark schemes. The study reveals performance improvements in throughput, quality of service, and system stability, alongside critical analysis of the framework’s robustness under predictive uncertainty.

Figure 1.

UAV-assisted communication framework based on spatiotemporal traffic prediction.

2. Related Work

Cellular network traffic forecasting and drone-assisted communication represent the two core technologies addressed in this paper. Consequently, the current research landscape will be examined from the perspectives of traffic prediction and drone-assisted communication.

As a core component underpinning modern communications infrastructure, the traffic-forecasting capability of cellular networks directly impacts network resource allocation, service quality assurance, and energy efficiency optimization. Traditional traffic-forecasting methods predominantly rely on statistical models [,,,,,,,] or shallow machine-learning approaches [,,,,,,], such as the seasonal autoregressive integrated moving average (SARIMA) model and support vector regression (SVR). Whilst these methods perform well in forecasting stationary time series, they often fail to effectively capture complex characteristics present in real-world networks, such as non-stationarity, coexisting multimodal patterns, and dynamic evolution. In recent years, deep learning models [,,,,,,], such as long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, have been widely applied to traffic-forecasting tasks due to their robust sequence-modeling capabilities. These models can uncover spatiotemporal correlations hidden within traffic patterns. Researchers have devised various hybrid models integrating distinct neural network architectures. A mature paradigm combines convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for spatial feature extraction with RNNs or their variants (e.g., LSTMs and GRUs) to capture temporal dependencies. Huang et al. [] designed a spatiotemporal fully connected convolutional network (ST-FCCNet). Its unique unit architecture captures spatial dependencies between any two regions within a city. Combined with modeling temporal proximity, daily cycles, and weekly cycles, this achieves precise city-wide cellular traffic forecasting. Lin et al. [] similarly employed multichannel LSTMs within their proposed model to capture hourly, daily, and weekly periodic temporal features. They innovatively integrated a multi-graph convolutional network (MGCN) to capture complex spatial features, ultimately constructing an accurate spatiotemporal traffic prediction model. The att-MCSTCNet model proposed by Zeng et al. [] employs convolutional LSTMs (Conv-LSTMs) or convolutional GRUs (Conv-GRUs) to model neighboring area data and periodic data. By introducing an attention mechanism, the model dynamically assigns varying weights to features from different sources, effectively enhancing the specificity and efficacy of feature extraction. Li et al. [] similarly employed a deep residual network (ResNet) to capture spatial features, combining it with RNNs and attention mechanisms to capture temporal dependencies, thereby achieving efficient modeling of spatiotemporal correlations.

However, the performances of these deep-learning-based forecasting methods are highly dependent on the volume of training data. When training data are insufficient, the vast number of parameters in deep learning models may converge to positions far from the target values due to overfitting. Second, these methods typically rely on substantial amounts of labeled data for training, exhibiting limited generalization capabilities when confronted with data distribution drift or unseen traffic patterns, and are prone to performance degradation. To enhance models’ adaptability to new tasks and improve generalization capabilities, meta-learning has been introduced to traffic forecasting. For instance, Li et al. [] proposed a meta-learning-based cellular network traffic prediction framework (ML-TP). Its core concept involves utilizing meta-features from new prediction tasks to provide suitable initial weights for the learning model. Through fast Fourier-transform analysis, the study found that the five primary frequency components sufficiently capture cellular traffic variations, serving as meta-features for the task. When the meta-features of two tasks are sufficiently close in Euclidean space, the model weights trained for one task can serve as a favorable starting point for another new task. To this end, they designed a meta-learner based on the k-nearest-neighbor algorithm for task matching. Experiments demonstrate that this framework significantly enhances the post-training prediction accuracy and learning efficiency of the base learning model. This research provides inspiration for the prediction module in this paper.

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), with their high maneuverability, flexibility for rapid on-demand deployment, relatively low operational costs, and ability to readily establish line-of-sight (LoS) communication links, are rapidly emerging from a niche application domain to become an indispensable key component in constructing future 6G-and-beyond integrated air–ground–space communication networks [,]. UAV-assisted communication technologies demonstrate immense potential in rapidly restoring emergency communication networks post natural disasters, providing temporary hotspot coverage enhancement for large gatherings or remote areas, and delivering efficient data aggregation services for vast, widely distributed Internet-of-Things (IoT) devices [,].

Joint resource allocation and three-dimensional trajectory optimization represent the most central and challenging issues in UAV-assisted communication research. Unlike fixed ground-based base stations, UAVs are mobile aerial platforms which communication performance (e.g., channel gain and interference levels) is intrinsically linked to their three-dimensional spatial position and attitude. It is imperative to synergistically and jointly optimize the UAVs’ flight trajectories, communication resources, computational resources, and user-scheduling strategies to maximize a specific system performance metric while satisfying various constraints. This constitutes an NP-hard problem mathematically, making it difficult to directly obtain a global optimal solution.

To effectively solve such problems, researchers have proposed and developed numerous efficient suboptimal algorithms. Among these, block coordinate descent (BCD) and successive convex approximation (SCA) stand as two of the most widely employed and demonstrably effective techniques. The core principle of the BCD algorithm is “divide and conquer through iterative solution”. This involves grouping the mutually coupled optimization variables within the original problem and then fixing the variables in other groups while successively optimizing each group of variables. This iterative process continues until the algorithm converges. For instance, in their study of multi-UAV-assisted communication systems, Tang et al. [] employed the BCD method to successfully decompose the complex original problem of maximizing the total system throughput into three relatively straightforward and manageable subproblems: user scheduling, UAV trajectory optimization, and power allocation. By introducing slack variables and employing convex approximation techniques, such as first-order Taylor expansions, they transformed the non-convex subproblems to convex problems for solution. Ultimately, high-quality suboptimal solutions were obtained through alternating iterations. Wang et al. [] similarly employed the BCD framework in their study of UAV-assisted NOMA backscatter communication systems. They decomposed the original problem into three subproblems: UAV transmit-power optimization, tag reflectivity coefficient optimization, and the joint optimization of UAV positioning and the SIC-decoding sequence. Efficient solution methods were designed for each subproblem. The core principle of SCA lies in approximating the original non-convex problem at each iteration with a sufficiently accurate and easily solvable convex counterpart near the current point. Solving this convex problem updates the variables, progressively approximating the optimal solution to the original problem. Pan et al. [] employed SCA in their study of drone-assisted communication in unlicensed bands, effectively transforming the highly non-convex trajectory-planning problem to a series of solvable convex planning problems, thereby achieving rapid transmission of monitoring data. Ha et al. [] ingeniously combined BCD and SCA methods in their work, jointly optimizing power, power allocation ratios, and trajectories within a drone-assisted SWIPT system. Their objective was to maximize the system’s secure energy efficiency. The present study draws inspiration from these references during its joint optimization process.

3. System Model

3.1. Network Scenario Description

We consider a downlink drone-assisted cellular network covering an extensive urban or suburban scenario. This network comprises multi-tiered heterogeneous access points, specifically:

Ground Infrastructure Layer: Comprising M cellular base stations, denoted as . These stations are fixed in location but may enter sleep mode due to energy management strategies;

Aerial Mobile Layer: Comprising U unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) functioning as mobile airborne base stations (ABSs), denoted by the set . Each UAV is equipped with communication devices and cruises at a fixed altitude () to provide on-demand communication services to ground users;

User layer: Comprises N ground users (Users), denoted collectively as . User positions are obtained via GPS or other positioning technologies and are assumed to change slowly within the short-term optimization timeframe.

Time is discretized to equal-length time slots denoted as , each lasting . The framework’s core lies in utilizing historical traffic data to predict future time slot network states, thereby guiding UAVs to make optimal decisions in the current time slot. This achieves a paradigm shift from “reactive” to “proactive” operation.

3.2. Traffic-Forecasting Model

Accurate traffic forecasting underpins proactive optimization. We employ an advanced prediction framework based on GMM-ML, which effectively addresses the heterogeneity, periodicity, and small-sample learning challenges inherent in cellular traffic data.

Historical Data: For each base station (), we record its past time-slot-normalized traffic load sequence, denoted as , where .

Prediction Model: We train a predictor () for each base station. This model first performs a fast Fourier transform (FFT) on the traffic sequence, extracting its principal frequency components as meta-features. Subsequently, a Gaussian mixture model (GMM) serves as the meta-learner, probabilistically modeling these meta-features to capture the clustering characteristics of different base station traffic patterns. Finally, an optimal model initialization weight is generated for the new prediction task through a multi-component mechanism (MCM) and a negative feedback (NF) correction strategy.

Prediction Output: At time slot t, the predictor outputs the traffic load forecast values for each base station over the next time slots as follows:

where represents the GMM model parameters for base station m.

Hotspot Identification: Using the prediction results, we define a binary hotspot indicator variable () to identify which base stations will become traffic hotspots in future time slots (t), requiring priority service provision by the UAV as follows:

where is a traffic threshold predefined according to network operational strategy.

3.2.1. Generation of a Feature Candidate Pool Based on the Global Energy Spectrum

The frequency-domain sub-feature extraction for the GMM-ML predictor is based on the fast Fourier transform (FFT), converting the time-domain traffic sequence () to a frequency-domain representation as follows:

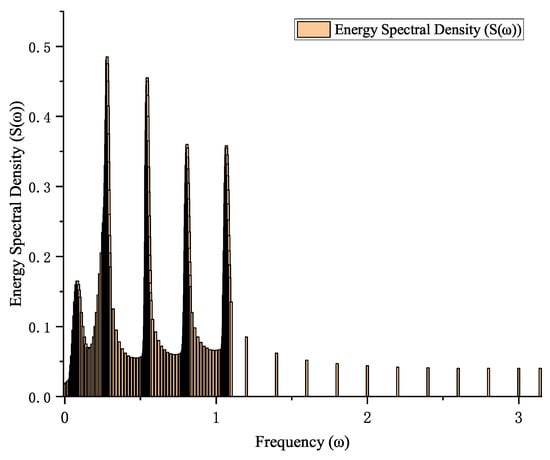

This paper selects five specific frequency components: (corresponding to sine waves with periods of 1 week, 1 day, 12 h, 8 h, and 6 h, respectively) as the cellular network’s meta-features. This selection stems from a systematic analysis of the frequency domain energy distribution across all the cellular traffic sequences in the dataset. The specific selection rationale and validation process are as follows: (1) Mathematical Foundations of Frequency-Domain Feature Extraction

First, the FFT amplitude spectrum () was computed for the normalized traffic load vectors of all the cellular cells. Subsequently, the global average energy spectral density was calculated.

(2) To ensure the universality of these five frequency components, we further examined their significance across different cellular subpopulations.

Step 1: We randomly sampled multiple subsets based on each cell’s total traffic volume and geographical location (e.g., high-traffic cells, low-traffic cells, city-center cells, and suburban cells).

Step 2: For each subset, we repeated Step (1) to compute its subset-averaged energy spectrum.

Results: Across all the tested subsets, the aforementioned five frequency components consistently represented the most prominent peaks in the energy spectrum. We conducted paired t-tests comparing the average energy at these five frequency points with that at adjacent frequencies, revealing in all instances that the energy at these five points was significantly higher than background noise and neighboring frequencies, indicating that they represent robust, cross-regional common patterns.

This energy spectrum quantifies the average importance of each frequency component across the entire dataset. As shown in Figure 2, significant peaks emerge near five frequency points, corresponding to periods confirmed as 1 week, 1 day, 12 h, 8 h, and 6 h, respectively. This forms the preliminary basis for the feature candidate pool in this paper.

Figure 2.

Cumulative curve of the total system throughput over time.

(3) Interpretability of physical significance

The selected frequency components possess explicit, human-activity-driven physical significance:

Weekly cycle: captures macro-level flow pattern differences between weekdays and weekends.

Diurnal cycle: Reflects fundamental human rhythms, constituting the core pattern of the diurnal traffic alternation.

(12/8/6-hour cycles): These sub-diurnal and shorter cycles may correspond to refined intra-day activity patterns, such as lunch breaks and commuting peaks (morning/evening), providing the model with richer temporal detail.

3.2.2. Theoretical Analysis of Non-Gaussian Multimodal Distributions

Considering information bottleneck theory:

where H() denotes entropy, and Hgmm() denotes conditional entropy based on the GMM assumption. When the true traffic distribution deviates from the GMM assumption, the lower bound on information loss in the frequency domain features is

where denotes the KL divergence, and denotes mutual information. Table 1 presents a comparative analysis of the prediction performance under various distribution characteristics. The results indicate that the GMM-ML model consistently outperforms the LSTM model across different distribution types, as evidenced by lower RMSE values. Notably, the performance retention rate of GMM-ML remains high, even in complex scenarios, such as heavy-tailed distributions and time-varying distributions, demonstrating its robustness and adaptability to diverse traffic patterns.

Table 1.

Prediction performance comparison under different distribution characteristics.

3.3. Communication and Channel Modeling

The quality of the wireless channel between the UAV and ground users is a key determinant of the optimized performance. We employ a widely adopted air-to-ground (A2G) path loss model that incorporates the probability of both line-of-sight (LoS) and non-line-of-sight (NLoS) links. To simplify the analysis and highlight the core optimization problem, we focus on LoS-dominant scenarios, where the path loss can be approximated by the free-space path loss (FSPL).

The Euclidean distance between the UAV (j) and the user (i) during time slot t is as follows:

According to the Friis transmission formula, the channel power gain for this link can be expressed as follows:

where and represent the transmitter antenna gain and receiver antenna gain of the UAV, respectively. is the carrier wavelength, where c is the speed of light, and is the carrier frequency, while is the far-field reference distance, which is typically set at 1 m.

Assuming that the drone transmits at a fixed power (), the receiver’s signal-to-noise ratio is as follows:

where is the power of the additive Gaussian white noise.

The system employs frequency division multiple access (FDMA), allocating equal bandwidth to each user. According to Shannon’s formula, the data rate obtainable by the user (i) from the UAV (j) is as follows:

3.4. User Association and the Quality-of-Service (QoS) Model

Regarding user association, this paper introduces a binary decision variable to characterize the connection state.

It is assumed that each user can be served by at most one access point (UAV or ground base station) within the same time slot. Users not served by UAVs will be served by the ground network (which performance is not directly considered in this optimization problem). Each user has specific QoS requirements, typically characterized by their required minimum data rate (). To ensure that a user is successfully served within a time slot, the following condition must be satisfied:

Due to the limited onboard communication resources (e.g., spectrum and processing capacity) of UAVs, the maximum number of users a single UAV can serve is denoted by K. This constraint is formalized as

Furthermore, the drone’s mobility underpins its flexible service provision but introduces additional constraints. The drone’s positional changes between consecutive time slots are limited by its maximum flight speed () as follows:

4. Problem Formulation

This paper aims to design a joint optimization framework that synergistically optimizes drone trajectory planning and user association strategies to maximize the system’s long-term performance within a finite time domain. Unlike conventional approaches that solely optimize instantaneous performance, this framework incorporates traffic prediction information, enabling forward-looking optimization decisions.

4.1. Decision Variables

The user association strategy is defined as the set of association decisions across all the time slots, denoted by , where , and for all and .

UAV Trajectories: The flight paths of all the UAVs across all the time slots, }, where .

4.2. Objective Function

This paper designs a multiobjective tradeoff function that simultaneously considers the immediate utility of the current network and the benefits of preparing to serve potential future hotspots.

where the first term represents the current network utility, aiming to maximize the weighted sum of rates for currently served users. The logarithmic function () is employed instead of a linear function to ensure fairness among users while enhancing the overall throughput, preventing excessive resource allocation to a minority of users with exceptionally favorable channel conditions. () is the discount factor, used to discount future returns. The closer is to 0, the more the optimization strategy focuses on the current period; the closer is to 1, the more forward-looking the optimization strategy becomes. In addition, is the weighting factor, used to balance the importance of instantaneous rate utility and future preparedness rewards within the objective function. It can be adjusted through network simulations to achieve the optimal performance.

The second term represents the future hotspot readiness reward: This constitutes our core innovation, where indicates whether the base station (m) within the time slot (t) is a predicted hotspot. is a function measuring the drone’s readiness to serve the hotspot base station (m), which we define as follows:

where denotes the set of users within the coverage area of the base station (m). The significance of this function lies in incentivizing the drone to serve users in predicted hotspot areas, yet the reward diminishes marginally once the number of users served in that area reaches the drone’s maximum service capacity (K). At this point, the reward ceases to increase, thereby preventing excessive resource concentration.

The optimization problem () is formulated subject to the following constraints:

- User Association Constraint: Each user can be associated with at most one access point (UAV) in any time slot slot

- UAV Service Capacity Constraint: The number of users served by a single UAV cannot exceed its maximum service capacity

- Quality-of-Service (QoS) Constraint: The achievable data rate for an associated user must satisfy its minimum requirement

- UAV Mobility Constraint: The position change of a UAV between consecutive time slots is constrained by its maximum velocity

- UAV Initial Position Constraint:

Problem constitutes a large-scale, multi-time-slot mixed-integer nonlinear programming (MINLP) problem. The decision variables include both integer (binary association indicators) and continuous (UAV trajectory) components. Furthermore, the objective function and constraint are non-convex, which precludes the existence of a polynomial-time algorithm capable of finding the global optimum. Consequently, an efficient, low-complexity suboptimal algorithm must be developed.

5. Solution Algorithm: Proactive Iterative Optimization Algorithm

To address the joint optimization problem proposed in [], this paper proposes a P-IALO algorithm. Employing a receding horizon control (RHC) framework, this algorithm decomposes the multi-slot problem to a sequence of single-slot problems, alternately optimizing user association and UAV positioning within each slot. The algorithm’s pseudocode is presented in Algorithm 1.

5.1. Detailed Explanation of the Key Steps

The optimization is solved using the block coordinate descent (BCD) method. This algorithm alternately optimizes one block of variables while keeping the others fixed, iterating until convergence. The original problem is thus decomposed to two subproblems: (1) user association with fixed drone positions and (2) drone position optimization with fixed user associations. The solution process for each subproblem is described next.

| Algorithm 1 Predictive iterative association and location optimization (P-IALO) |

|

Input: Initial drone position , Prediction model , Total time slots T, Prediction window , Discount factor , Reward weight . Output: Optimal trajectory and associated policy .

|

5.1.1. User Association Subproblem

Given the r drone position at iteration , the objective function and constraints of the user association subproblem are simplified from the main problem () to

Subject to:

where is a known constant.

The objective function is linear in the binary variable (), and constraints (C1) and (C2) are also linear. However, constraint (C3) is nonlinear because it couples the continuous variable () with the binary variable (). Consequently, the problem constitutes a mixed-integer nonlinear programming (MINLP) problem. While this formulation is simpler than the original trajectory-augmented version, it remains computationally challenging, necessitating specialized algorithms to handle the non-convex constraint (C3).

The logic of constraint (C3) is as follows: If user i is associated with drone j (i.e., ), the achievable data rate () must be at least the user’s minimum requirement (). This constraint allows for a useful preprocessing step: For any user–UAV pair (), if the predicted or calculated rate (), the association is infeasible, and we must set , regardless of other conditions. Consequently, we can predefine a feasible association set for each time slot as follows:

Following this preprocessing, constraint (C4) is implicitly satisfied. The problem transforms to solving the following optimization problem over the feasible set ():

Subject to:

This constitutes a weighted bipartite graph-matching problem, where the user set () and the drone set () form the two partitions. An edge () exists in the feasible set () with a weight of . Our objective is to assign at most one drone to each user (C1’) and each drone to at most K users (C2’), thereby maximizing the total weight. This problem is NP-hard. However, in practice, K is typically low, and weights are positive, allowing efficient greedy algorithms to yield high-quality suboptimal solutions with a complexity of .

Steps of the greedy algorithm:

(a) Initialization: Set all the association variables () at 0. Initialize a counter () for each drone (j).

(b) Calculate Weights: For all the feasible pairs (), obtain the edge weight ().

(c) Sorting: Sort all the feasible pairs () in descending order of .

(d) Greedy Allocation: Traverse the sorted list. For the current pair (), if user i is unassigned and drone j has not reached its capacity (), assign user i to drone j: set and increment .

(e) Output: The resulting association matrix is .

5.1.2. UAV Location Subproblem

Given the user associations at iteration , the location subproblem is decoupled. For each UAV (j), its position optimization is independent of others. Its subproblem is

where denotes the set of users requiring service from the UAV (j).

- Non-convexity analysis: The objective function () is a nested composite function. The inner function () is a convex function with respect to , which second derivatives are positive. However, the outer function () is concave. The convexity of the composite of a concave and convex function cannot be guaranteed; hence, the entire objective function is non-convex.

- Continuously convex approximation (SCA): For a non-convex function, at a given local point (), construct a globally convex approximation function that serves as an upper or lower bound, and iteratively optimize this approximation. Here, we opt to construct a differentiable global lower bound; by maximizing this bound, we ensure the original objective function is non-decreasing at each iteration.

- Constructing a lower bound approximation: xml-ph-0000@deepl.internal, which is a concave function.Let , which is a concave function.Let . As previously stated, is a convex function with respect to .For the concave function (), its first-order Taylor expansion constitutes its global upper bound as follows:However, here, we require a lower bound. Although itself is not concave, we may approximate itself with a linear lower bound and then utilize ’s monotonicity. Specifically, for a convex function (), its first-order Taylor expansion at a given point () constitutes a global lower bound as follows:Since is a monotonically increasing function, we obtainTherefore, constitutes a global lower bound for the original objective function term ().

- Calculate the derivativeWe now require .Let .Since , by the chain ruleAt the point , this derivative is constant, denoted as (taking the negative sign yields )Simultaneously, let

- Constructing the convex approximation problem: Substituting the above derivation yields that for the unmanned aerial vehicle (j), the lower bound of its optimization objective isLet . Note that is a concave function with respect to , while is a linear function with respect to since is convex but prefixed with a negative sign. The composition of a concave function with a linear function remains concave. Hence, is a concave function with respect to . Maximizing a concave function constitutes a convex optimization problem.

- Adding a trust region: Since Taylor series expansions are only accurate near local points, it is necessary to ensure that the new solution () does not deviate too far from the current point (); otherwise, the approximation becomes inaccurate, potentially causing algorithmic divergence. Therefore, we introduce a trust region constraint as follows:where is the trust region radius for the (r)th iteration, which can be adaptively adjusted. This constraint is a convex constraint (quadratic convex constraint).

- The final convex formulation: For each drone (j), the convex optimization problem to be solved at the (r + 1)th iteration isThis is a constrained convex optimization problem. The objective function is concave, and the constraint set is convex. This paper opts to utilize MATLAB (R2024a)’s fmincon toolbox for direct solutions. The new position obtained from the solution () will be employed for the next iteration.By alternately executing these two sub-steps, the value of the original objective function improves (or remains unchanged) with each iteration. As the objective function has an upper bound, the algorithm ultimately converges to a local optimum.

5.2. Lyapunov-Based Convergence Analysis

Consider the discrete-time Lyapunov function:

where represents the global optimum value, and denotes the current objective function value.

Construct the Lyapunov function and analyze its difference:

For the associated subproblem, due to the use of optimal matching

For the location subproblem, based on the conservative approximation guarantee of SCA

Therefore,

When holds, , and the system converges stably.

Under time-varying channel conditions, the channel gain () is modeled as follows:

Table 2 presents the convergence performance under various channel conditions, where P-IALO still guarantees convergence when the channel change rate () occurs.

Table 2.

Convergence performance under different channel conditions.

6. Experiments and Analysis

6.1. Experimental Objectives

This experiment aims to validate the effectiveness of the proposed P-IALO algorithm through simulations. Specific objectives include.

Validate the core innovation: Demonstrate that incorporating traffic prediction for forward-looking optimization significantly enhances long-term system performance compared to traditional reactive optimization.

Evaluate the algorithmic performance: Comprehensively assess the P-IALO algorithm’s throughput, quality of service, and convergence speed in varying network load and user mobility scenarios.

Conduct comparative analyses: Quantify performance gains by contrasting P-IALO against multiple benchmark algorithms.

Robustness testing: Examine the algorithm’s resilience under real-world conditions where prediction errors exist.

Datasets and Preliminary Analysis

This section primarily introduces the dataset utilized, comprising real-world mobile network traffic records, and presents mathematical analyses of cellular traffic in both the time and frequency domains.

- (1)

- Spatial Gridding and Cell DefinitionThe traffic prediction section employs a mobile network dataset provided by Telecom Italia’s Big Data Challenge program. The dataset comprises approximately 3 million traffic records collected in Milan between 1 November 2013 and 1 January 2014. The city area was divided into 10,000 grids, each representing a square region with a side length of 235 m, serving as the fundamental spatial unit for this study. Each record contains a timestamp, a grid ID, and a mobile traffic load (i.e., a traffic payload). Given that the grid size approximates the coverage area of a 50-base station, each grid is defined herein as a “cell”.

- (2)

- Time Series ConstructionFor analytical convenience, the entire dataset’s temporal span is divided into consecutive one-hour intervals, denoted asAssume there are N time intervals, where r denotes the traffic record index, represents the cell ID for record r, indicates the timestamp for record r, and signifies the traffic load for record r. The time series for the pth cell traffic load is represented by the vector .

- (3)

- Meta-feature extractionWithin each cell, although traffic load variations differ daily, they exhibit fixed periodic patterns weekly. To quantify the temporal correlation of the cellular traffic load, the autocorrelation coefficient of the normalized traffic load vector for cell P can be calculated as follows:This paper selects five specific frequency components: , , , , and , corresponding to periods of 1 week, 1 day, 12 h, 8 h, and 6 h, respectively (as sinusoidal signals) as the meta-features for the cellular network. This selection is based on a systematic analysis of the frequency-domain energy distribution across all the cellular traffic sequences in the dataset.The real and imaginary parts of the five principal frequency components may form a 10-dimensional principal frequency component vector, i.e., the cellular principal feature, as follows:where and represent the real and imaginary parts of the complex number, respectively.

6.2. Comparison Algorithms

This paper will conduct performance comparisons of the following four benchmark algorithms:

Static UAV: The UAV remains stationary at its initial position, optimizing only the user association. This serves as the baseline performance lower bound.

Reactive-IALO: The original IALO algorithm from the first paper. The UAV optimizes its position and the user association solely based on the current network state, without utilizing traffic prediction ().

KNN Proactive: This replaces the GMM-MCM-NF predictor in our framework with the k-nearest neighbor (nKNN) algorithm, with the remainder identical to P-IALO. It is used to compare the merits of predictive models.

Exhaustive Search: At each time slot, we run the algorithm on a simplified, small-scale network. It approximates the global optimum via a grid search, serving as a performance upper bound reference, though computational complexity precludes its use in real-world scale networks.

The parameters for the simulation environment and algorithms are detailed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Parameter settings.

6.3. Evaluation Metrics

Total throughput: The sum of the achieved rates for all the users across all the time slots.

QoS satisfaction: The percentage of user–slot pairs where the achieved rate meets QoS requirements () relative to the total number of user–slot pairs.

Algorithm convergence speed: The distribution of internal iterations of the P-IALO algorithm across the time slots, measuring the computational efficiency.

Interruption count: The total number of times user service drones switch. Frequent switching leads to signaling overhead and a degraded experience.

6.4. Results and Analysis

6.4.1. Fundamental Performance Analysis

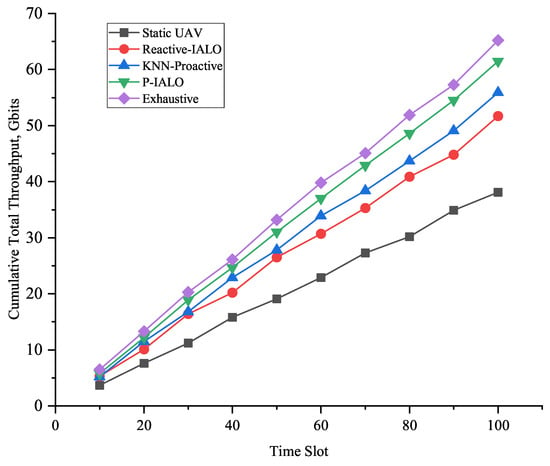

Analysis from Figure 3 reveals that static UAVs exhibit the poorest performance, as they cannot adapt to user mobility and traffic fluctuations.

Figure 3.

Cumulative curve of the total system throughput over time.

Reactive-IALO outperforms Static, demonstrating the necessity of dynamic optimization. However, its performance exhibits significant fluctuations and a response lag during traffic bursts (e.g., around time slots 40 and 70).

KNN-Proactive outperforms Reactive, validating predictive approaches. Yet its limited performance gain indicates KNN’s inferiority to GMM models in capturing complex spatiotemporal correlations.

P-IALO delivers the optimal and most stable performance. Through precise predictive deployment, it positions itself optimally before traffic peaks arrive, maximizing network resource utilization. Its curve most closely approaches the exhaustive upper bound, validating its effectiveness.

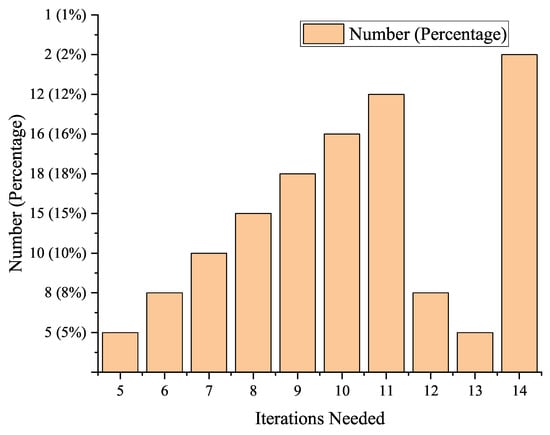

Figure 4 shows that P-IALO converges within fewer than 15 iterations for the majority of the time slots (>90%), proving its computational efficiency and suitability for (near-) real-time applications.

Figure 4.

Distribution of internal iterations for P-IALO.

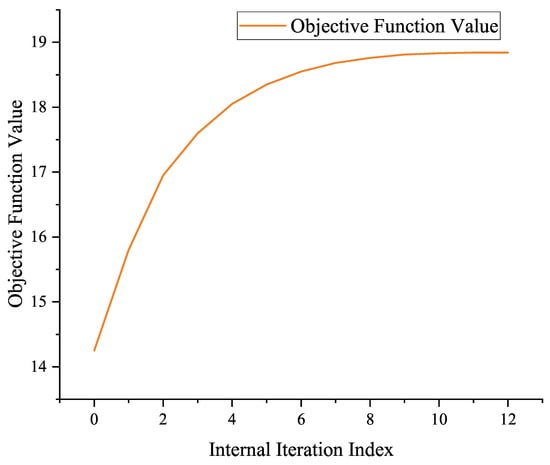

Figure 5 validates the monotonic convergence of the BCD algorithm. Following each solution of the correlation or position subproblem, the objective function value steadily increases.

Figure 5.

Convergence process of the objective function value for time slot 50.

Table 4 shows that P-IALO significantly outperforms other benchmark algorithms in both the total throughput and QoS satisfaction (with improvements ranging from approximately 12% to 60%). This indicates that our approach not only enhances the network efficiency but also better safeguards the user’s experience. Notably, P-IALO exhibits the lowest average user interruption rate. This stems from predictive deployment, enabling a more forward-looking and stable drone movement, thereby reducing frequent handoffs caused by the reactive `chasing’ of users.

Table 4.

Comparison of average performance metrics.

6.4.2. Robustness Analysis

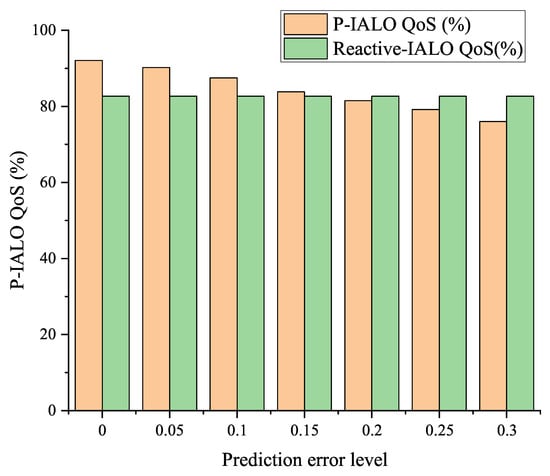

Figure 6 illustrates how P-IALO’s QoS satisfaction varies at different levels of prediction error. We simulated prediction errors by adding zero-mean Gaussian noise to real traffic data (greater noise variance indicates larger errors). The results show that even with a 20% prediction error, P-IALO significantly outperforms the Reactive-IALO algorithm without any predictions. This confirms our framework’s robust resilience to prediction errors, rendering it practically feasible for real-world applications.

Figure 6.

Prediction error robustness test (QoS satisfaction).

To validate the robustness of the GMM-ML predictor under insufficient training data (few-shot) conditions and its impact on the stability of the P-IALO framework, we conducted few-shot prediction robustness tests. The test scenario was fixed at a 100-slot dynamic environment, using an LSTM network as the comparison model. Training data comprised 10%, 30%, 50%, 70%, and 100% of the full training set.

The experimental results are presented in Table 5 and Table 6. When only 10% of the training data is available, GMM-ML exhibits significantly lower prediction errors than LSTM. Moreover, the P-IALO system driven by GMM-ML maintains a final performance of 89.6%, whereas the LSTM approach only achieves 80.7%. This demonstrates GMM-ML’s capability for rapid adaptation to new tasks.

Table 5.

Prediction performance comparison under small-sample conditions.

Table 6.

Comparison of predictive performance under small-sample conditions.

Regarding the convergence speed and efficiency, GMM-ML’s training time is significantly shorter than LSTM’s at any data proportion. This stems from GMM-ML’s training inherently involving parameter estimation of a probability distribution, whereas LSTM requires extensive gradient descent iterations. This indicates GMM-ML’s superior computational efficiency, making it more suitable for online or edge-computing scenarios demanding rapid model updates.

6.4.3. Impacts of Different Forecasting Models on P-IALO Performance

The objective of this section’s experiments is to compare the overall performance differences of various traffic prediction models when deployed as the front end of the P-IALO framework, thereby validating the superiority of the GMM-ML model.

The model parameters for comparison are as follows:

ARIMA: (p,d,q) = (3,1,2).

LSTM: Single layer, 64 hidden units, sliding window = 10.

GRU: Single layer, 64 hidden units, sliding window = 10.

KNN-ML: K=4.

The results, as shown in Table 7 and Table 8, show a strong positive correlation between the accuracy of the prediction models and the overall performance of the P-IALO framework. Leveraging its meta-learning capabilities for handling heterogeneity and small samples, the GMM-ML model significantly outperforms traditional time-series models (ARIMA), standard deep learning models (LSTM/GRU), and simple similarity-matching models (KNN) in predictive accuracy. GMM-ML reduces the RMSE by approximately 20.5% compared to the next-best KNN model. This advantage directly translates to enhanced system performance: Compared to KNN-Proactive, the GMM-ML-driven P-IALO achieves an approximately 4.5% higher total throughput and a 1.6% improvement in QoS satisfaction. This demonstrates that more precise predictions enable UAVs to anticipate network hotspots earlier and more accurately, thereby facilitating superior predeployment decisions.

Table 7.

Comparison of the prediction accuracy across different models.

Table 8.

Performances of P-IALO systems driven by different prediction models.

6.4.4. Impact of the Prediction Time Horizon on the System Performance

The selection of the prediction horizon () involves a fundamental tradeoff. An excessively short prohibits proactive deployment due to limited maneuver time, whereas an overly long is plagued by high prediction uncertainty, resulting in misguided actions. This work systematically characterizes this tradeoff by evaluating a range of values to determine the optimum for the given scenario.

Table 9 shows that the system utility value initially increases and then decreases with rising , peaking at . This reveals the existence of an “optimal predictive horizon” within forward-looking optimization. The experiment further indicates that the optimal reward weight () increases as grows. This suggests that longer prediction time horizons necessitate stronger incentives for the UAV to prepare for the future, thereby balancing short-term utility with long-term returns. This provides guidance for hyperparameter tuning.

Table 9.

Performance variation across different prediction time spans.

6.4.5. Quantitative Analysis of the Relationship Between the Prediction Error and System Performance

Error Propagation Model and Theoretical Analysis

Consider the error propagation within the hotspot readiness reward term of the objective function. Let the true hotspot indicator variable be , the predicted value be , and the prediction error be .

The hotspot readiness component in the objective function:

The decision deviation caused by the prediction error:

Through the first-order optimality conditions of the optimization problem, changes in the objective function propagate to the system throughput as follows:

where denotes the dual variable. Combining with expectation operations yields a lower bound on the throughput loss.

The lower bound of the system throughput loss due to the prediction error is

Empirical Analysis of the Error–Performance Quantitative Relationship

Establishing a quantitative relationship between the prediction error and throughput loss via polynomial regression:

The empirical results in Table 10 demonstrate that as the prediction error increases, the system performance metrics (throughput loss, QoS satisfaction decline, spectrum efficiency loss, and service readiness loss) degrade significantly. This quantification provides critical insights into the sensitivity of the system to prediction inaccuracies, guiding future improvements in prediction models and system design.

Table 10.

Quantitative relationship between the prediction error and system performance.

6.4.6. Hyperparameter Sensitivity Analysis

This section employs the Sobol’ global sensitivity analysis method to quantify the impact of each hyperparameter on the system performance.

First-order sensitivity indices:

Hyperparameter Range Settings:

Table 11 presents the results of the hyperparameter sensitivity analysis. Based on this analysis, the following hyperparameter configuration strategy is proposed:

- Fine-tuning critical parameters: and require a grid search or a Bayesian optimization;

- Empirical configuration of secondary parameters: K and may be set according to scenario characteristics;

- Default values for secondary parameters: and employ recommended default values.

This section’s sensitivity analysis reveals that the discount factor and reward weight are critical parameters influencing the system performance, providing explicit guidance for parameter tuning in practical deployments. These findings not only enhance our understanding of the algorithm’s robustness but also offer practical references for parameter configuration across different scenarios.

Table 11.

Results of the hyperparameter sensitivity analysis.

Table 11.

Results of the hyperparameter sensitivity analysis.

| Hyperparameter | First-Order Sensitivity Index | Total Sensitivity Index | Sensitivity Level | Recommended Range | Performance Variance Explained (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discount factor | 0.28 | 0.35 | High | [0.85, 0.92] | 32.5 |

| Reward weight | 0.22 | 0.27 | High | [0.25, 0.35] | 25.8 |

| Number of GMM components K | 0.15 | 0.19 | Medium | [5, 7] | 17.3 |

| Prediction window | 0.12 | 0.16 | Medium | [5, 7] | 13.5 |

| Learning rate | 0.06 | 0.09 | Low | [0.01, 0.05] | 5.9 |

| Trust domain value | 0.08 | 0.11 | Low | [40, 60] | 9.1 |

6.4.7. System Scalability Analysis

As the scale of UAV-assisted communication networks expands, the scalability of the system () becomes a critical performance metric. This section analyses the scalability of the proposed method from three dimensions: computational complexity, communication overhead, and resource allocation.

Computational Complexity Analysis

The primary computational burden of the P-IALO algorithm stems from its prediction and optimization modules. Let the network comprise U UAVs, N users, and M base stations, with the time domain spanning T time slots.

The upper bound on the computational complexity of the P-IALO algorithm is

where denotes the maximum internal iteration count, represents the complexity of a single SCA convex optimization, and signifies the prediction computational load per base station.

Proof.

The algorithm comprises three primary computational components:

- Association subproblem: Employing a greedy algorithm to sort and match N users and U drones, with complexity ;

- Position subproblem: Each drone independently solves a convex optimization problem. Using an interior-point method yields , where n is the variable dimension;

- Forecasting module: Performs -step forecasting for M base stations using a GMM meta-learning framework, with complexity .

The overall complexity is the product of the outer time-slot loop and the inner iteration.

□

Multi-UAV Scalability Verification

To validate the system scalability, this paper tests the performance across networks of varying scales, adjusting the number of UAVs from 1 to 5 while keeping other parameters constant. The results in Table 12 indicate that as the number of UAVs increases, the total throughput and QoS satisfaction improve significantly. However, the average computation time and convergence iteration count also rise, reflecting the increased complexity of coordinating multiple UAVs.

Table 12.

System performance at different UAV scales.

Multi-UAV coordination requires exchanging status information, with communication overhead as follows:

where bytes represent the size of the status information, and Hz.

The analysis is shown in Table 13 which indicates that when the number of UAVs exceeds five, the communication overhead surpasses 5%, potentially impacting data transmission efficiency. This necessitates the design of more efficient distributed coordination mechanisms.

Table 13.

Communication overhead for networks of different sizes.

6.4.8. Robustness Analysis of Channel Models

Impacts of Altitude Disturbances on the Communication Model

Although this paper assumes UAVs cruise at a fixed altitude (), real-world flights involve altitude fluctuations. Considering altitude disturbance , the actual communication distance is adjusted as follows:

Taking the partial derivative of the channel gain formula

As the derivative is always negative, an increase in altitude will cause the channel gain to decrease.

Impacts of Motion Disturbances on the Communication Quality

Vibrations and attitude changes generated by the UAV’s motion affect the antenna pattern, introducing additional gain fluctuations. The corrected channel model accounting for motion disturbance is

where represents gain fluctuations caused by vibration, modeled as . denotes the gain loss due to pointing error, modeled as .

The impact of different flight conditions on communication performance is summarized in Table 14. The results indicate that under strong turbulence, the rate loss can reach up to 18.3%, and the QoS compliance rate drops by 12.7%. This highlights the necessity of considering flight-induced disturbances in UAV communication system designs.

Table 14.

Impacts of flight conditions on the communication performance.

6.4.9. Limitations and Practical Deployment Challenges

Although the P-IALO framework proposed in this section performs well in simulation environments, it still faces several challenges and limitations in practical deployment.

Limitations at the Algorithmic Level

The Prediction Dependency Issue: P-IALO’s performance is highly contingent upon the accuracy of traffic forecasting. In real-world scenarios, sudden events (such as large gatherings or traffic accidents) may cause drastic shifts in traffic patterns, which historical data-based prediction models struggle to capture. When prediction errors exceed 30%, forward-looking optimization may conversely degrade the system performance, inducing a “misguided” effect.

The Computational Timeliness Challenge: Whilst P-IALO’s average computation time performs well in simulations (approximately 15 s per time slot), it may fail to meet stringent real-time requirements on actual edge-computing devices. Accounting for practical overheads, such as code parsing and memory access, the measured runtime on the Jetson TX2 platform increased by approximately 40–60% compared to that in the simulated environment.

Local Optimum Traps: SCA-based optimization methods guarantee convergence but not global optimality. Within multimodal optimization landscapes, the algorithm may become trapped in suboptimal solutions, particularly when initialization points are poorly chosen, resulting in performance losses of 15–25%.

Technical Challenges in Practical Deployment

Sensing and Positioning Errors: User position acquisition in real-world systems introduces inaccuracies, with GPS typically achieving 2–5 m positioning accuracy, which may deteriorate further in urban canyon environments. Positioning errors (, ) directly propagate in distance calculations, causing biases in channel estimation and association decisions.

Communication Protocol Overhead: Practical UAV networks require substantial control-signaling exchanges, including channel state feedback, handover signals, and coordinated scheduling information. Field measurements indicate that control overhead can consume 5–15% of the total bandwidth, reducing the effective data transmission capacity.

Energy Constraints and Endurance Limitations: Practical drone flight is constrained by the battery life, and frequent trajectory adjustments significantly increase the energy consumption. Energy-optimized models necessitate tradeoffs between communication performance and endurance time, which exceed the scope of the current framework.

Idealized Channel Modeling: The simplified path loss model employed herein inadequately accounts for multi-path, shadowing, and blocking effects prevalent in urban environments. Within dense urban areas, Non-Line-of-Sight (NLoS) link occurrence rates may reach 30–50%, substantially degrading the communication quality.

7. Conclusions

This paper systematically investigates, designs, and evaluates a joint optimization framework for drone-assisted communication based on spatiotemporal traffic prediction, demonstrating strong theoretical innovation and practical value. The key contributions are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- The introduction of a closed-loop, forward-looking optimization framework: We introduce a framework that for the first time, tightly integrates traffic forecasting into the UAV decision-making cycle, establishing an integrated “forecast–optimize–execute” architecture. This endows UAVs with the capacity to anticipate future network conditions, achieving a fundamental shift from reactive response to proactive scheduling;

- (2)

- The design of a high-performance traffic prediction model: We design a prediction model by incorporating a meta-learning approach based on Gaussian mixture models (GMM-ML). This model effectively addresses challenges in scenarios with small samples and heterogeneity, significantly enhancing both prediction accuracy and generalization to provide reliable inputs for subsequent optimization;

- (3)

- The formulation of a long-term optimization model: We establish a long-term optimization problem that innovatively incorporates a “service readiness reward” into the objective function. This incentivizes drones to predeploy to forecast hotspot areas, balancing immediate utility with future gains and enhancing the overall system performance;

- (4)

- The development of the P-IALO solution algorithm: We develop the P-IALO algorithm, which leverages techniques such as rolling optimization, block coordinate descent, and continuous convex approximation. It decomposes the complex MINLP problem to efficiently solvable subproblems, ensuring both convergence and real-time performance suitable for practical deployment;

- (5)

- A comprehensive simulation validation: In a real-data-driven simulation environment, the proposed framework demonstrates superiority across multiple dimensions—including throughput, QoS satisfaction, interruption frequency, convergence speed, and robustness. It exhibits particular stability under prediction errors and small-sample conditions, confirming its strong practical value.

This research advances UAV network optimization from static to dynamic and from myopic to forward-looking. It also offers novel insights for intelligent resource management in the integrated air–ground–space networks of the 6G era. Future work may extend to multi-vehicle coordination, energy consumption optimization, and end-to-end reinforcement learning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L.; Methodology, X.L.; Software, X.L.; Validation, X.L.; Formal analysis, X.L.; Investigation, X.T. and X.L.; Resources, X.T.; Data curation, J.Z.; Writing—original draft, X.L. and J.Z.; Writing—review & editing, X.L. and Y.L.; Visualization, X.L.; Supervision, Y.L.; Project administration, J.Z.; Funding acquisition, J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Xing Tai and Jiao Zhu were employed by the companies UniCom Vsens Communications Co., Ltd. and China Unicom Research Institute, respectively. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Wang, C.X.; You, X.; Gao, X.; Zhu, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, H.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Haas, H.; et al. On the Road to 6G: Visions, Requirements, Key Technologies, and Testbeds. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2023, 25, 905–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, W.; Bennis, M.; Chen, M. A Vision of 6G Wireless Systems: Applications, Trends, Technologies, and Open Research Problems. IEEE Netw. 2020, 34, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, G.K.; Gurjar, D.S.; Yadav, S.; Jiang, Y.; Yuen, C. UAV-Assisted Communications With RF Energy Harvesting: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2025, 27, 782–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, K.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, C.X.; Ye, X.; Gomez-Ponce, J.; Cai, X.; Miao, Y.; Cui, Z.; Wu, Q.; Fan, W. A Survey on Channel Sounding Technologies and Measurements for UAV-Assisted Communications. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bithas, P.S.; Ropokis, G.A.; Karagiannidis, G.K.; Nistazakis, H.E. UAV-Assisted Communications With RIS: A Shadowing-Based Stochastic Analysis. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 10000–10010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Chow, C.Y.; Zhang, J.D. STNN: A Spatio-Temporal Neural Network for Traffic Predictions. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 22, 7642–7651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Xiao, F.; Xing, K.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Peng, C. Spatio-Temporal Analysis and Prediction of Cellular Traffic in Metropolis. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2019, 18, 2190–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Wu, J.; Jiang, H. Spatio-Temporal Trajectory Design for UAVs: Enhancing URLLC and LoS Transmission in Communications. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2024, 13, 2417–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Hu, J.; Yan, H.; Liu, Y. Bayesian Spatio-Temporal grAph tRansformer network (B-STAR) for multi-aircraft trajectory prediction. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 249, 108998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Peng, X.; Zhang, P.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Yang, R.; Xiang, P. An intelligent GNN seismic response prediction and computation framework adhering to meshless principles: A case study for high-speed railway bridges. Eng. Anal. Bound. Elem. 2025, 179, 106359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wu, C.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Z.; He, K.; Du, R.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, Y. Privacy-Preserving Universal Adversarial Defense for Black-Box Models. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2025, 20, 11503–11515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Sun, J.; Chen, J.; Alazab, M.; Liu, Y.; Xiang, Y. TCG-IDS: Robust Network Intrusion Detection via Temporal Contrastive Graph Learning. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2025, 20, 1475–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Yu, S.; Yoon, W.S.; Kim, Y.D. A new prediction method of alpha-stable processes for self-similar traffic. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Telecommunications Conference, Dallas, TX, USA, 29 November–3 December 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tedjopurnomo, D.A.; Bao, Z.; Zheng, B.; Choudhury, F.M.; Qin, A.K. A Survey on Modern Deep Neural Network for Traffic Prediction: Trends, Methods and Challenges. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2022, 34, 1544–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Feng, J.; Wang, W.; Xin, K. An approach for spatial-temporal traffic modelling in mobile cellular networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Teletraffic Congress, Ghent, Belgium, 8–10 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, F.; Lin, Y.; Huang, J.; Wu, D.; Shi, H.; Song, J.; Li, Y. Big data driven mobile traffic understanding and forecasting: A time series approach. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2016, 9, 796–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Yu, M.; Yang, O.; Liu, J.; Feng, H. Wireless traffic modelling and prediction using seasonal ARIMA models. IEICE Trans. Commun. 2005, 88, 3992–3999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhao, Z.; Zhou, X.; Palicot, J.; Zhang, H. The prediction analysis of cellular radio access network traffic: From entropy theory to networking practice. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2014, 52, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikunov, D.; Nishimura, T. Traffic prediction for mobile networks using Holt-Winter’s exponential smoothing. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Software, Telecommunications and Computer Networks, Split, Croatia, 27–29 September 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, F.; Yang, J.; Liu, H. Analysis of self-similar traffic based on the on/off model. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Workshop on Chaos-Fractals Theories and Applications, Shenyang, China, 6–8 November 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Jin, Y.; Qiang, S.; Hu, W.; Jiang, K. Analysing and modelling spatio-temporal dependence of cellular traffic at city scale. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC), London, UK, 8–12 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.; Liu, H.X.; Xiao, H.; Ran, B. Short-term traffic forecasting using the local linear regression model. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board, Washington, DC, USA, 21–23 March 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Roughan, M.; Willinger, W.; Qiu, L. Spatio-temporal compressive sensing and internet traffic matrices. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGCOMM 2009 Conference on Data Communication, Barcelona, Spain, 16–21 August 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Zhao, Z.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, H. Energy savings scheme in radio access networks via compressive sensing-based traffic load prediction. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 2014, 25, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapankevych, N.I.; Sankar, R. Time series prediction using support vector machines: A survey. IEEE Comput. Intell. Mag. 2009, 4, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, R.H.; Maia, J.E.B. Network traffic prediction using PCA and K-means. In Proceedings of the IEEE Network Operations and Management Symposium (NOMS), Osaka, Japan, 19–23 April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Falvo, M.; Gastaldi, M.; Nardecchia, A.; Prudenzi, A. Kalman filter for short-term load forecasting: An hourly predictor of municipal load. In Proceedings of the IASTED International Conference on ASM, Palma de Mallorca, Spain, 29–31 August 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Yin, F.; Xu, W.; Lin, J.; Cui, S. Wireless traffic prediction with scalable Gaussian process: Framework, algorithms, and verification. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2019, 37, 1291–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, L.; Jiang, D.; Yu, S.; Song, H. Network traffic prediction based on deep belief network in wireless mesh backbone networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC), San Francisco, CA, USA, 19–22 March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Pan, L. Predicting short-term traffic flow by long short-term memory recurrent neural network. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Smart City/SocialCom/SustainCom (SmartCity), Chengdu, China, 19–21 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, L.; Janowicz, K.; Mai, G.; Yan, B.; Zhu, R. Traffic transformer: Capturing the continuity and periodicity of time series for traffic forecasting. Trans. GIS 2020, 24, 736–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, P.; Cui, S. Spatio-temporal wireless traffic prediction with recurrent neural network. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2018, 7, 554–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, Z.; Chen, X.; Li, R.; Zhang, H. Traffic prediction based on random connectivity in deep learning with long short-term memory. In Proceedings of the IEEE Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC-Fall), Chicago, IL, USA, 27–30 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Tang, J.; Xu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xue, G.; Zhang, X.; Yang, D. Spatiotemporal modelling and prediction in cellular networks: A big data enabled deep learning approach. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Communications (INFOCOM), Atlanta, GA, USA, 1–4 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Dai, Z.; He, Z.; Ma, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. Learning traffic as images: A deep convolutional neural network for large-scale transportation network speed prediction. Sensors 2017, 17, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.Y.; Yang, B.; Wu, Z.H.; Kuang, J.Y.; Yan, Z.M. Spatiotemporal fully connected convolutional networks for city-wide cellular traffic prediction. Comput. Eng. Appl. 2021, 57, 168–175. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, H.; Ding, M.; Cheng, P.; Hanzo, L. A data-driven base station sleeping strategy based on traffic prediction. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2021, 11, 5627–5643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Sun, Q.; Chen, G.; Duan, H. Attention-based multi-component spatiotemporal cross-domain neural network model for wireless cellular network traffic prediction. EURASIP J. Adv. Signal Process. 2021, 2021, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, H. A deep learning method based on an attention mechanism for wireless network traffic prediction. Ad Hoc Netw. 2020, 107, 102258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhang, Z.; Chu, X.; Zhang, J.; Qiu, S.; Zhang, J. A Meta-Learning Based Framework for Cell-Level Mobile Network Traffic Prediction. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2023, 22, 4264–4280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Bi, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, P. Unmanned aerial vehicle assisted communication: Applications, challenges, and future outlook. Clust. Comput. 2024, 27, 13187–13202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Kumar, N.; Dixit, D. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Assisted Wireless Communications: Enabling Connectivity and Applications. In Next-Generation Wireless Systems: Fundamentals and Applications; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 265–307. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B.; Xiong, X.; Liu, H.; Jia, Y.; Gao, Y.; Tolba, A.; Zhang, X. Unmanned aerial vehicle assisted post-disaster communication coverage optimisation based on internet of things big data analysis. Sensors 2023, 23, 6795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Sun, P.; Boukerche, A. Unmanned aerial vehicle-assisted energy-efficient data collection scheme for sustainable wireless sensor networks. Comput. Netw. 2019, 165, 106927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Huang, J.; Wang, B.; Song, Y.; Yu, G. Resource optimisation for multi-UAV-assisted communication systems based on user scheduling. J. Beihang Univ. 2025, 51, 1143–1151. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Fan, Z.; Wan, X.; Xu, Y. Max-min rate optimisation algorithm for UAV-assisted non-orthogonal multiple access backscatter communication systems. Trans. Chin. Inst. Electron. Inf. Technol. 2023, 45, 2358–2365. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.; Hu, H.; Jin, H.; Lei, Y.; Feng, H.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, M. Optimisation of Trajectory and Resource Allocation for UAV-Assisted Communications in Unlicensed Bands. Chin. J. Electron. Inf. Technol. 2024, 46, 4287–4294. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, D.; Jeong, S.; Kang, J.; Kang, J. Secrecy Energy Efficiency Maximisation for Secure Unmanned Aerial Vehicle-Assisted Simultaneous Wireless Information and Power Transfer Systems. Drones 2023, 7, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).