Robust Predictors of Mobile Phone Reliance for Information Seeking: A Multi-Stage Empirical Analysis and Validation

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Context and Rationale

1.2. Novelty and Contributions

- (a)

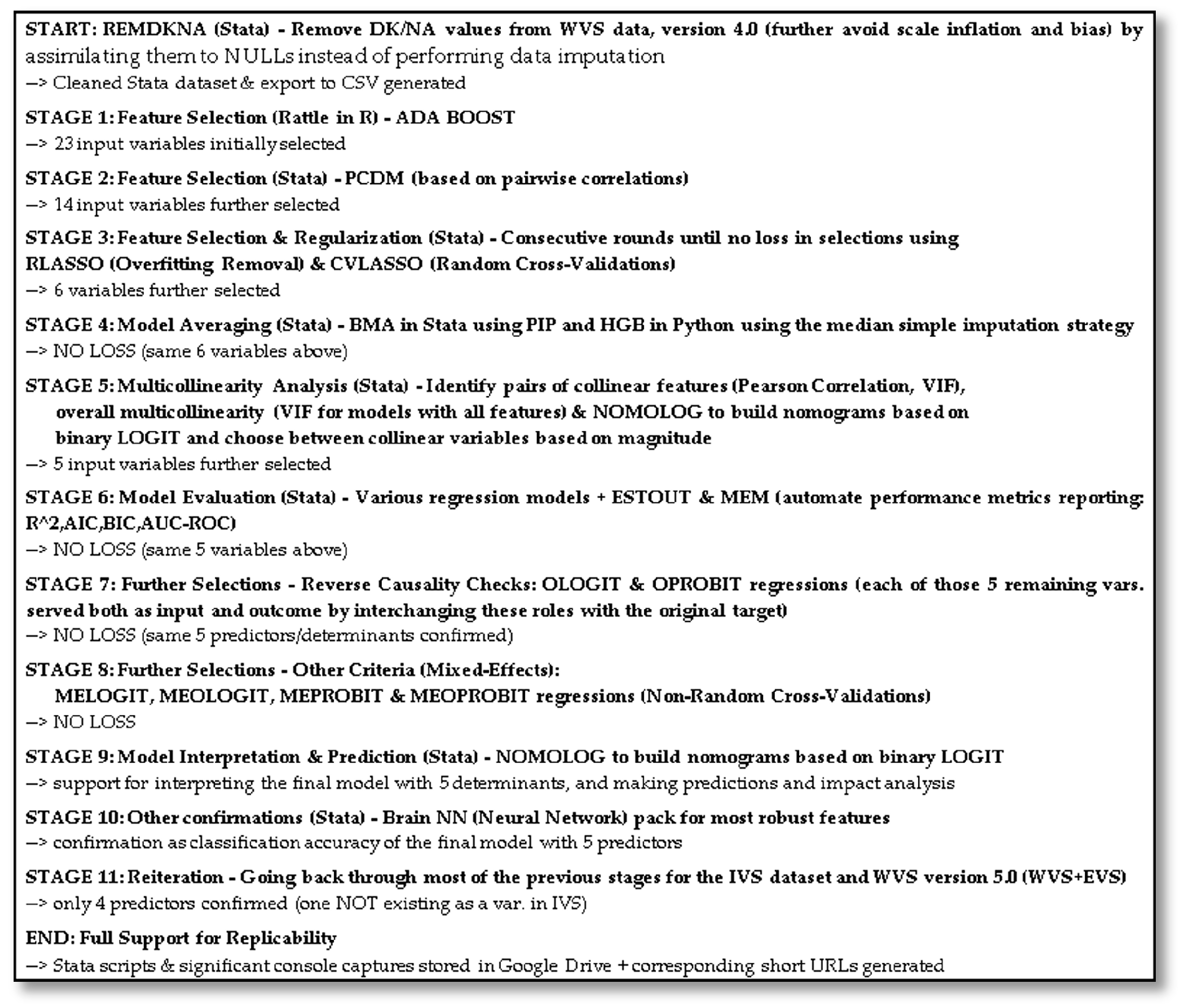

- Methodological Fusion: We proposed a new, multi-stage analytical framework centered on feature selection through rigorous triangulation. This approach systematically combines multiple Data Mining (DM) techniques (including HGB, AdaBoost, and Lasso methods) with traditional statistical models (e.g., Logit). Crucially, we empirically demonstrate the superiority of this triangulated approach as a robustness filter over single-method optimization (e.g., HGB). Specifically, while a single HGB selection yielded a higher raw predictive score based on AUC-ROC, this set proved structurally unstable in the Logit framework, experiencing a severe drop in performance and a loss of statistical significance for key variables. Our methodology, by contrast, identifies a minimal set of core predictors that maintain superior performance (e.g., AUC-ROC) and robustness across all tested frameworks, providing an unprecedented level of confidence in the generalizability of the findings.

- (b)

- Empirical Contribution: To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to apply such a comprehensive framework to the specific, cross-national WVS/IVS dataset, providing a new empirical understanding of a rapidly evolving social phenomenon. The latter includes uncovering novel predictors like radio usage, reflecting traditional media integration in digital behaviors.

- (c)

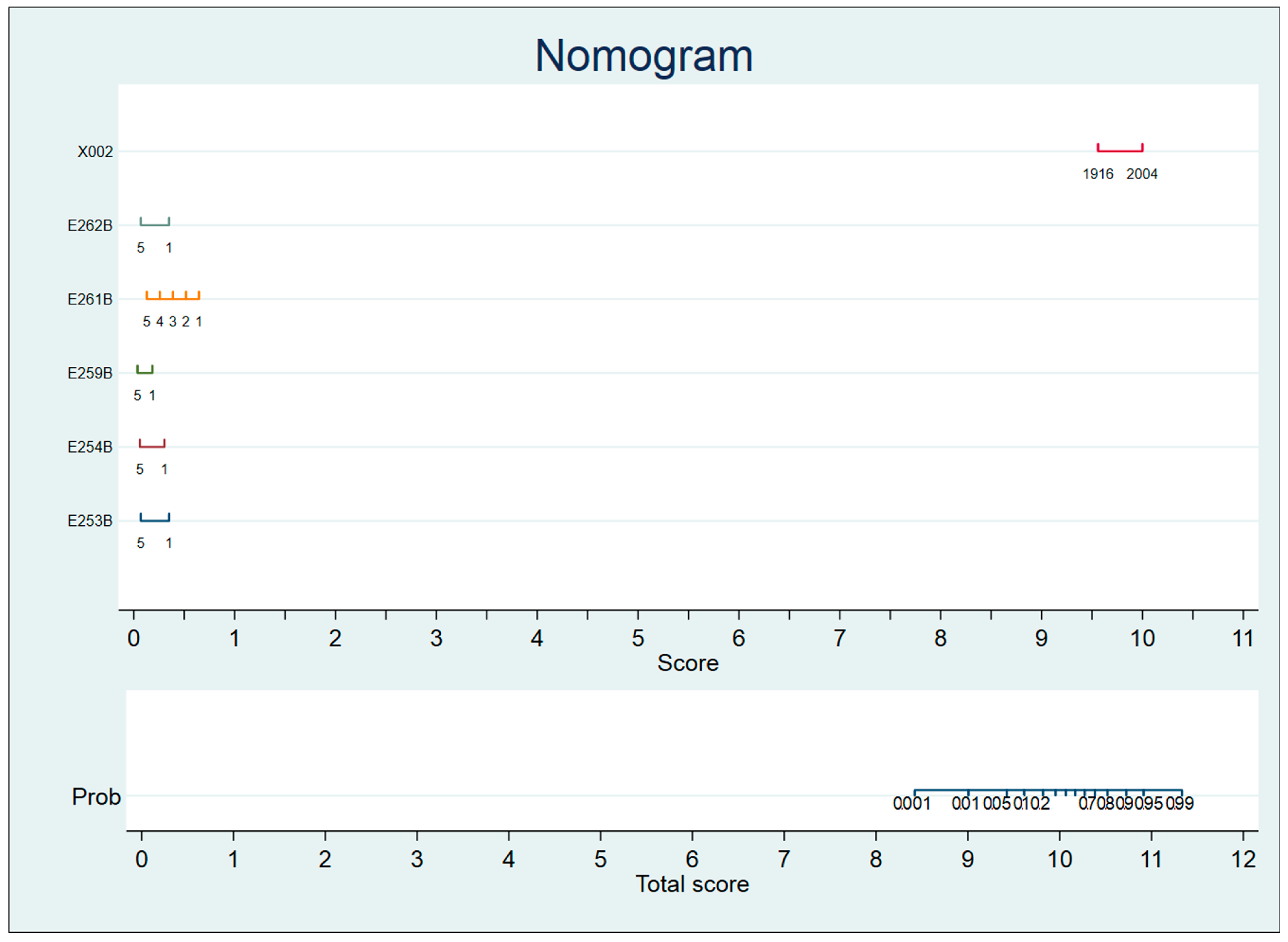

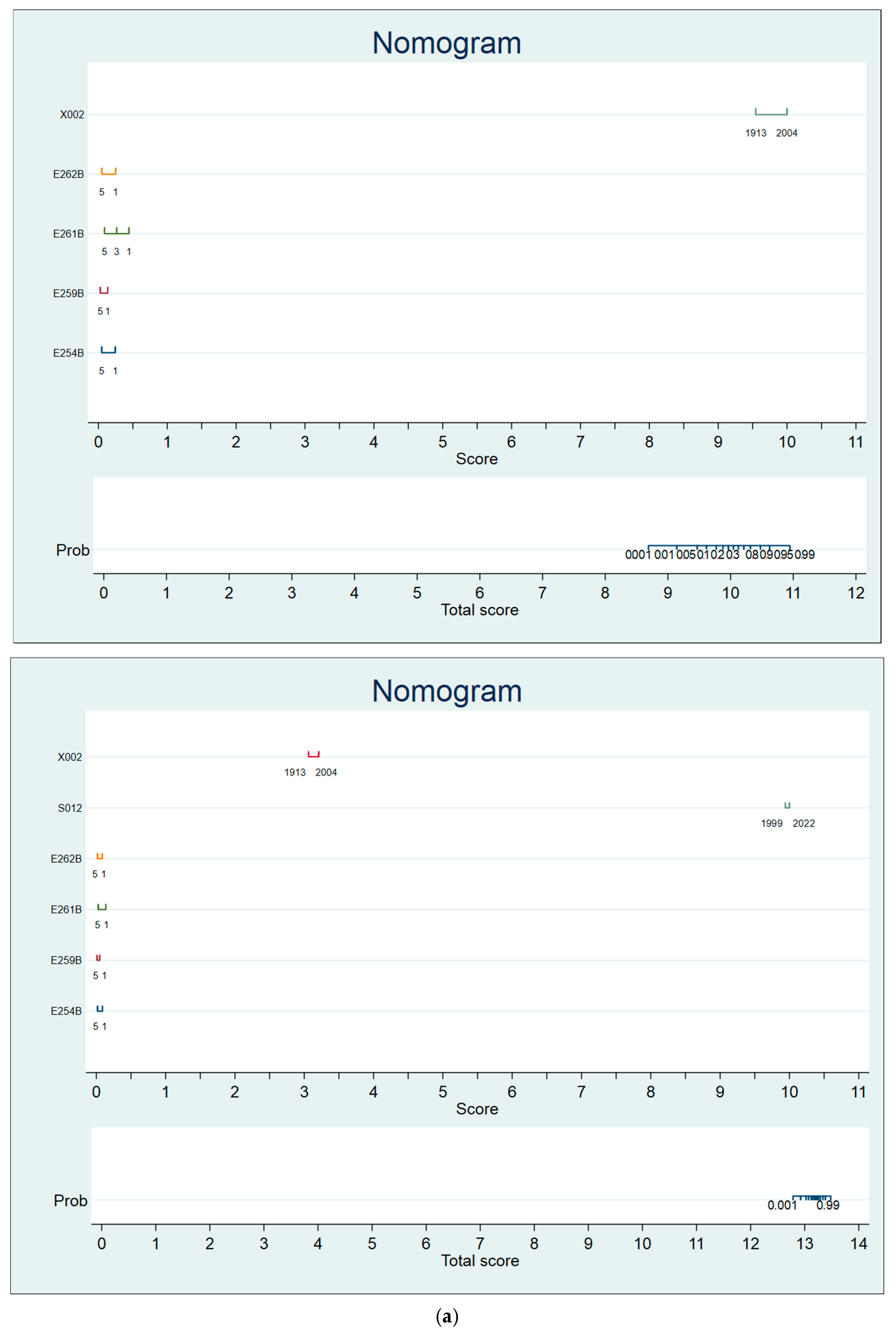

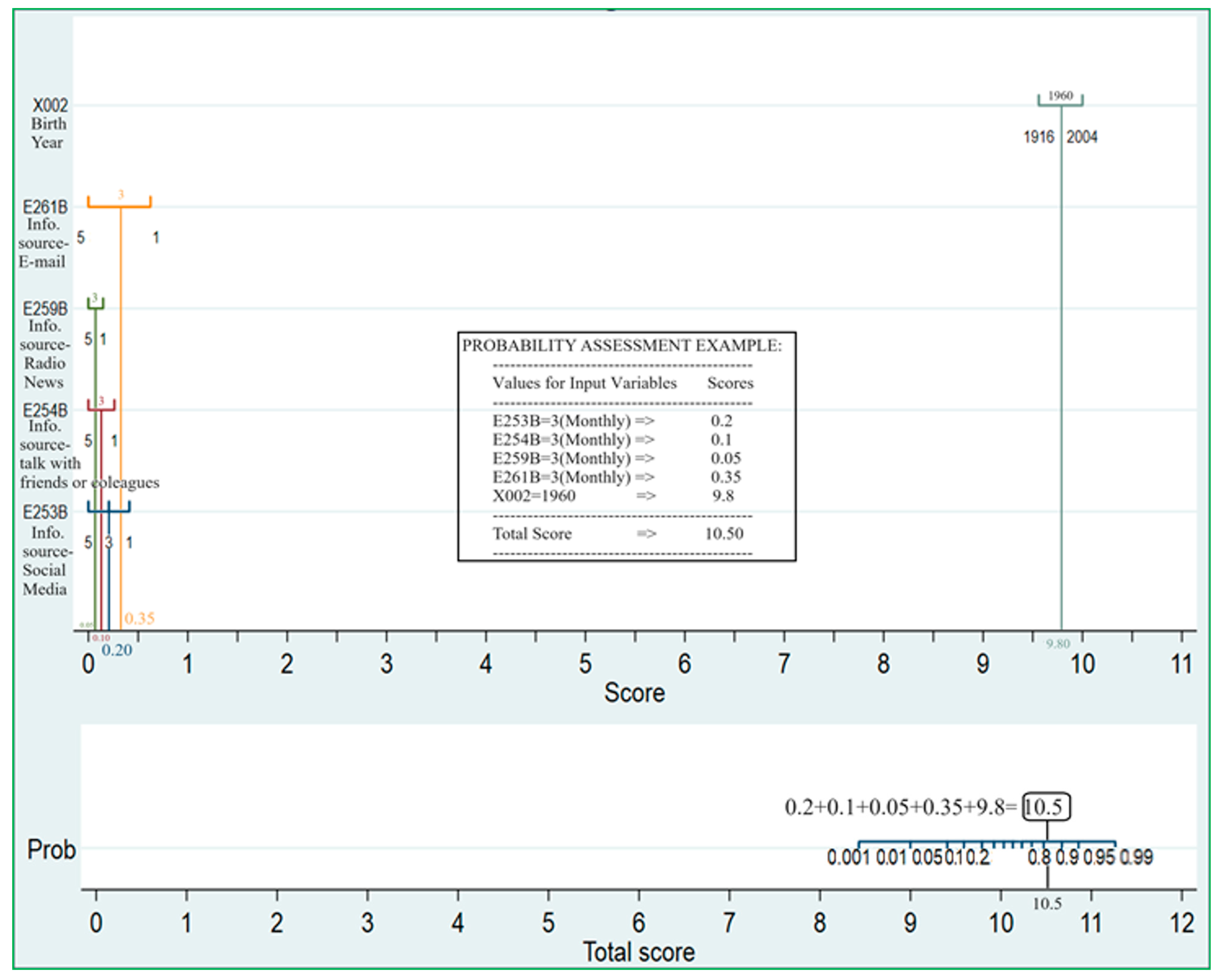

- Practical Tool: One of the final products of this research, the nomogram, is a significant contribution (in itself). It transforms complex research outputs into an intuitive tool for UI designers and policymakers, enabling simulations for optimizing application features (e.g., low-literacy interfaces).

2. Short Literature Review

2.1. Overview and Main Research Questions

2.2. Common Predictors and Contrasting Findings

- -

- Background (avoid abrupt brightness changes, use colors sparingly, and maintain high contrast between foreground and background elements);

- -

- Browsing (avoid scroll bars and overlapping pop-ups);

- -

- Cognition (provide sufficient time to read content and simplify decision-making by offering fewer choices, reducing cognitive load);

- -

- Content (eliminate irrelevant information, highlight key points, use simple and unambiguous language, and ensure consistent, user-friendly layout and navigation);

- -

- Graphics (avoid animations, ensure all images have alt tags, and use simple, meaningful icons to improve accessibility and clarity);

- -

- Target (avoid requiring double clicks and use larger, more visible targets to improve usability and accessibility). Judging by this list of additional requirements, access to information via the mobile phone is to the advantage of younger users (Hypothesis No. 5 or H5) [79].

2.3. Existing Gaps

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Key Data Selection Steps

3.2. Additional Tests and Validations

3.3. Demographic Analysis

4. Results

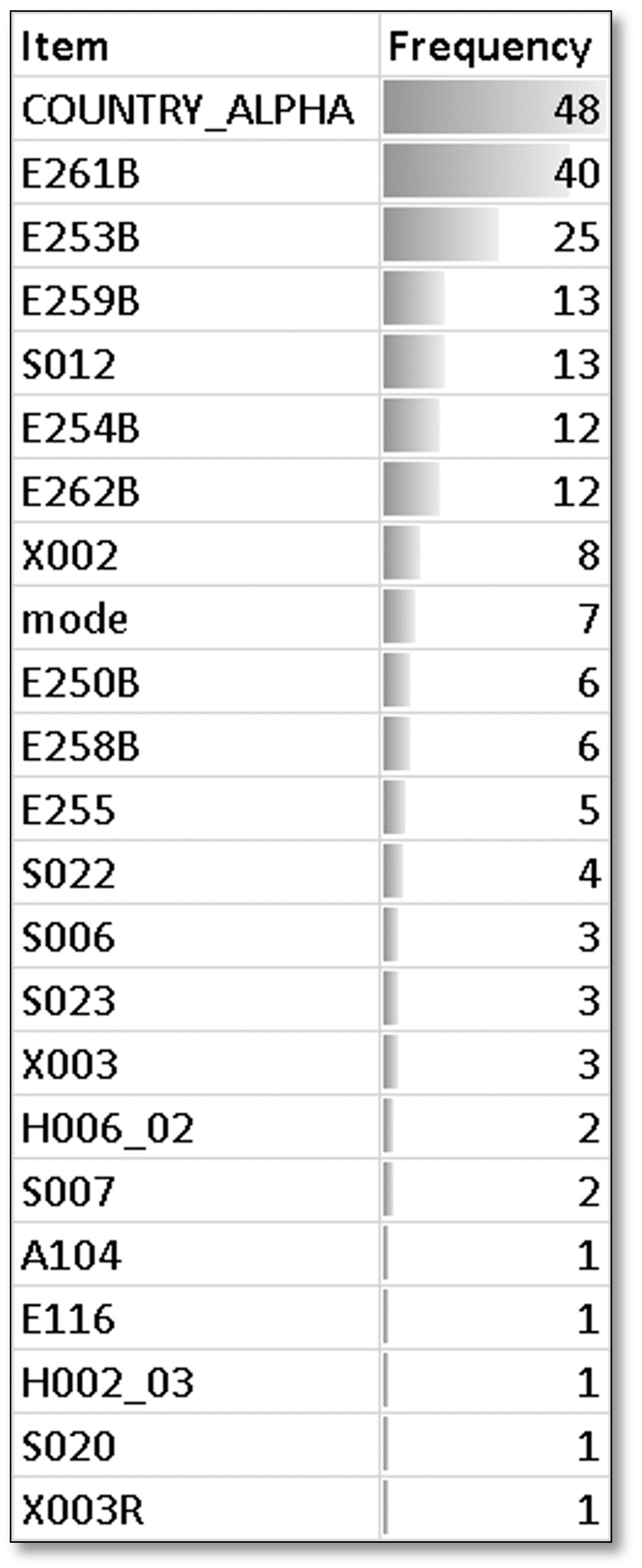

4.1. Outcomes of the Main Selection Steps

4.2. Results of Additional Tests and Validations

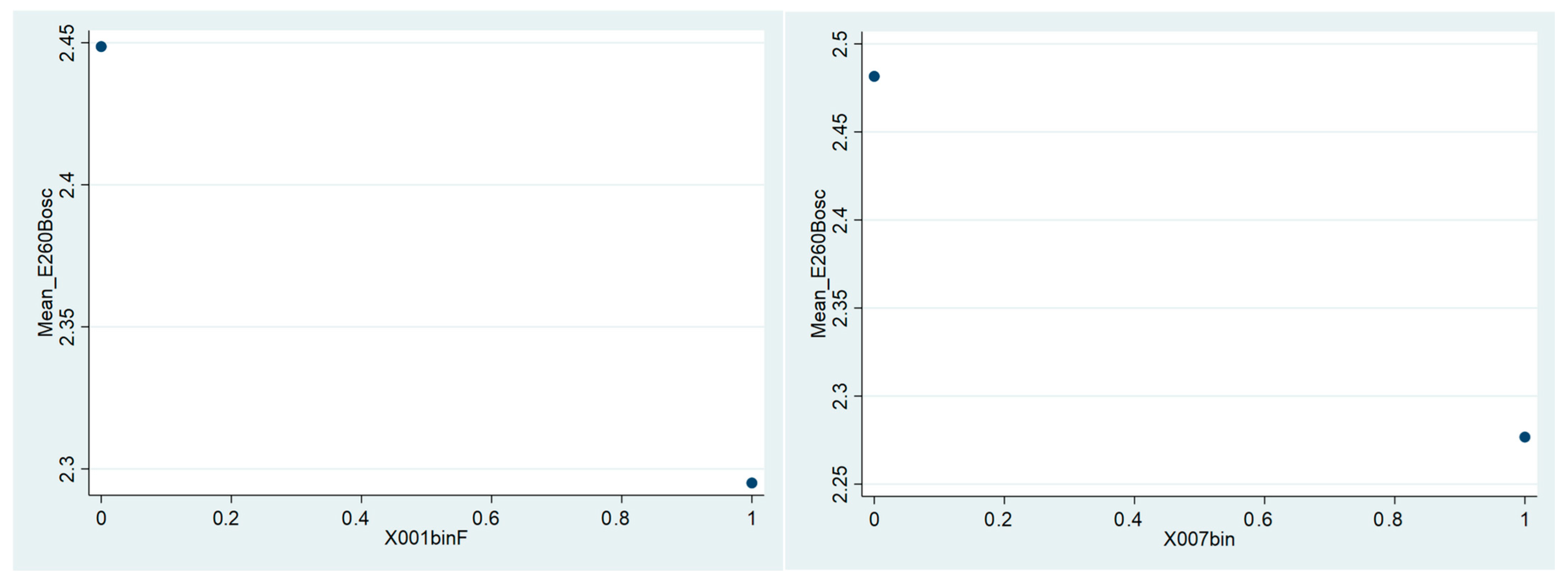

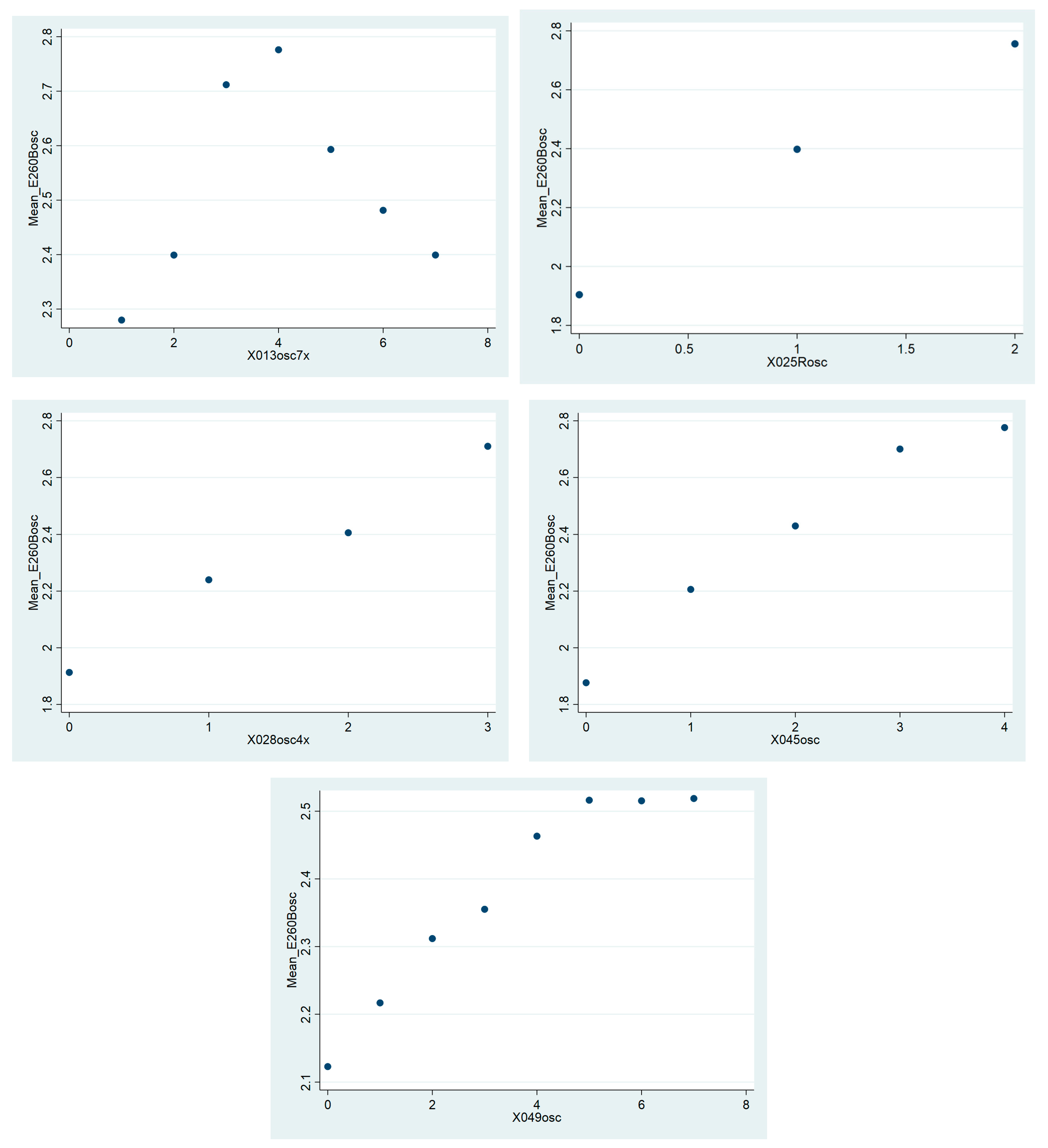

4.3. Demographic Analysis Outcomes

5. Discussion

5.1. Main Findings

5.2. Support and Additional Checks and Validations

5.3. Delimitation from Previous Findings

5.4. Potential Implications

5.5. Limitations

5.6. Addressing the Limitations in Further Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Criterion | Straightforward Longitudinal Model | Multi-Stage Ensemble (This Study) |

|---|---|---|

| Data compatibility | Requires balanced panel | Handles repeated cross-sections |

| Predictor robustness | Prone to collinearity/spuriousness | Triangulated stability |

| Nonlinear/heterogeneous effects | Assumed linear/homogeneous | Captured (HGB, subgroup analysis) |

| Causal inference support | Limited | Reverse causality checks (Stage 7) |

| Policy interpretability | Coefficients only | Nomogram-based simulation |

| Study (Author, Year) | Focus/Main Findings | Methods | Limitations/Gaps |

|---|---|---|---|

| Levine et al. (2012) [5] | Mobile phones as primary info devices, surpassing desktops; impacts on multitasking/distractibility. | Survey-based analysis of mobile media use. | Limited to U.S. context; descriptive, no robust predictors or global validation; ignores cultural variations. |

| Sher et al. (2022) [6] | Mobile dominance in info access; time-of-day/weekend patterns in LMS usage. | Analysis of LMS logs from blended learning. | Focus on educational settings; no cross-national data; lacks predictive modeling for broader behaviors. |

| Yu et al. (2022) [7] | Convenience/portability enhances info access; changes in electronic news habits. | Comparative survey of university students. | Region-specific (likely Asia); no integration of alternative channels (e.g., radio); limited to young demographics. |

| Neggaz et al. (2023) [8] | Mobile apps for specific info needs; boosted optimization for facial analysis. | ML-based boosting algorithm testing. | Technical focus on algorithms; no behavioral predictors; lacks empirical validation on survey data like WVS. |

| Alqahtani & Goodwin (2012) [10] | Growth of m-commerce via smartphones; affordability drives adoption. | Literature review and conceptual model. | Descriptive; no quantitative predictors; ignores age/digital divide effects. |

| Barry & Jan (2018) [11] | Seamless shopping via mobile-optimized sites/apps. | Case study/review of m-commerce trends. | Limited to e-commerce; no global/cross-cultural analysis; lacks robust statistical validation. |

| Salehan et al. (2018) [31] | Mobile usage linked to cultural values (e.g., individualism); global trends. | Cross-country trend analysis using secondary data. | Aggregate-level; no individual predictors (e.g., age, SN use); limited to associations, not causation. |

| Kushlev & Proulx (2016) [23] | Mobile info consumption linked to lower trust; social costs. | Empirical study on mobile use and trust. | Focus on negative outcomes; small sample; no predictive tools or multi-method triangulation. |

| Hoehle et al. (2015) [60] | Cultural values mediate mobile app use intention; usability as key predictor. | SEM on four-country survey data. | Limited countries; no integration with traditional media; ignores elderly/inclusive design gaps. |

| Pattison & Stedmon (2006) [72] | Inclusive design for older users in mobile phones. | Human factors/ergonomics review. | Conceptual; no empirical global data; highlights but does not address digital divide quantitatively. |

| Iancu & Iancu (2020) [73] | Mobile tech design for elderly; theoretical overview. | Literature synthesis on accessibility. | Theoretical; no predictive models; limited to design principles, not behavioral predictors. |

| Kasemsarn et al. (2024) [76] | Museums/apps for older/mobility-impaired; inclusive principles/digital storytelling. | Literature review on heritage accessibility. | Domain-specific (museums); no broad survey validation; lacks tools for policy simulation (e.g., nomograms). |

| Listing A1. Stata recoding script with numbered lines applicable at least to WVS or IVS datasets and meant to drop DK/NA values coded as negative ones and responsible for artificially increasing the scale of all variables. |

| 1 local nvar = c(k) 2 local k = 0 3 foreach v of varlist _all { 4 local k = ‘k’ + 1 5 di “Removing DK/NA from VAR.‘v’ = ‘: var label ‘v’’” 6 capture replace ‘v’ = . if ‘v’! = . & ‘v’ < 0 7 if !_rc { 8 di “OK!” 9 } 10 else { 11 di “EXCEPTION !!!” 12 } 13 local perc=int(‘k’/‘nvar’*100) 14 window manage maintitle “Removing DK/NA: Step ‘k’ of ‘nvar’ (‘perc’% done)!” 15 } 16 window manage maintitle “Stata” (Online at https://drive.google.com/u/0/uc?id=1NMCmr0m10gOqkFVNn45ePltW-Hib4sMH&export=download) |

| Listing A2. Simple Stata script for deriving the binary format of the target variables (WVS dataset, version 4.0) and checking its values when comparing them to the ones of the original form. |

| 1 generate E260BBin=. 2 replace E260BBin = 1 if E260B!=. & E260B>=1 & E260B<=4 3 replace E260BBin = 0 if E260B==5 4 label list E260B 5 tabulate E260B 6 tabulate E260BBin (Online at https://drive.google.com/u/0/uc?id=1BAIYNAizhRp4beeXxBBiTtvqHrxsMLIW&export=download) |

| Listing A3. Simple Stata script for selecting the variables most correlated with the outcome using the PCDM custom command using the WVS dataset (version 4.0). |

| 1 pcdm E260B E260BBin 2 pcdm E260B A104 E116 E250B E253B E254B E255 E258B E259B E261B E262B H002_03 H006_02 mode S006 S007 S012 S020 S022 S023 X002 X003 X003R, minacc(0.1) minn(89,170) maxp(0.001) 3 pcdm E260BBin A104 E116 E250B E253B E254B E255 E258B E259B E261B E262B H002_03 H006_02 mode S006 S007 S012 S020 S022 S023 X002 X003 X003R, minacc(0.1) minn(89,170) maxp(0.001) 4 *=> A104 E253B E254B E259B E261B E262B S007 S012 S020 S022 S023 X002 X003 X003R (Online at https://drive.google.com/u/0/uc?id=1bsgjtfzTUD26GE1ewieSLggEK8w_TWmo&export=download) |

| Listing A4. Simple Stata script for performing consecutive selections until convergence using the RLAASO and CVLASSO commands using the WVS dataset (version 4.0). |

| 1 rlasso E260B A104 E253B E254B E259B E261B E262B S007 S012 S020 S022 S023 X002 X003 X003R 2 rlasso E260BBin A104 E253B E254B E259B E261B E262B S007 S012 S020 S022 S023 X002 X003 X003R 3 *=> E260BBin A104 E253B E254B E259B E261B E262B X002 4 cvlasso E260B A104 E253B E254B E259B E261B E262B X002 5 cvlasso, lse 6 cvlasso E260BBin A104 E253B E254B E259B E261B E262B X002 7 cvlasso, lse 8 cvlasso E260B E253B E254B E259B E261B E262B X002 9 cvlasso, lse 10 cvlasso E260BBin E253B E254B E259B E261B E262B X002 11 cvlasso, lse 12 rlasso E260B E253B E254B E259B E261B E262B X002 13 rlasso E260BBin E253B E254B E259B E261B E262B X002 14 *=> Convergence/No removal (stable set of influences) (Online at https://drive.google.com/u/0/uc?id=1l93pJRBM06CtesmhW88HAzil1cb_uBip&export=download) |

Appendix B

| Variable | Short Description | Coding Details |

|---|---|---|

| E260B | Information source: Mobile phone (target variable—scale form) | 1-Daily, 2-Weekly, 3-Monthly, 4-Less than Monthly, 5-Never |

| E260BBin | Information source: Mobile phone (target variable—binary format) | 1-for E260B >=1 and <=4; 0-for E260B = 5 |

| E253B | Information source: Social media (Facebook, Twitter, etc.) | 1-Daily, 2-Weekly, 3-Monthly, 4-Less than Monthly, 5-Never |

| E254B | Information source: Talk with friends or colleagues | 1-Daily, 2-Weekly, 3-Monthly, 4-Less than Monthly, 5-Never |

| E259B | Information source: Radio news | 1-Daily, 2-Weekly, 3-Monthly, 4-Less than Monthly, 5-Never |

| E261B | Information source: E-mail | 1-Daily, 2-Weekly, 3-Monthly, 4-Less than Monthly, 5-Never |

| E262B | Information source: Internet | 1-Daily, 2-Weekly, 3-Monthly, 4-Less than Monthly, 5-Never |

| X002 | Year of birth | values between 1886 and 2004 |

| Variable | N (Obs.) | Mean | St.Dev. | Min | Median | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E260B | 178,339 | 2.63 | 1.78 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| E260BBin | 178,339 | 0.69 | 0.46 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| E253B | 90,726 | 2.69 | 1.8 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| E254B | 178,495 | 2.18 | 1.42 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| E259B | 178,588 | 2.81 | 1.69 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| E261B | 177,286 | 3.57 | 1.67 | 1 | 5 | 5 |

| E262B | 177,714 | 2.9 | 1.8 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| X002 | 439,978 | 1964.43 | 18.35 | 1886 | 1966 | 2004 |

| Variable | N (Obs.) | Mean | St.Dev. | Min | Median | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E260B | 87,741 | 2.44 | 1.73 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| E260BBin | 87,741 | 0.73 | 0.44 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| E253B | 87,741 | 2.7 | 1.8 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| E254B | 87,741 | 2.35 | 1.45 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| E259B | 87,741 | 3.1 | 1.69 | 1 | 3 | 5 |

| E261B | 87,741 | 3.55 | 1.66 | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| X002 | 87,741 | 1975.64 | 16.43 | 1916 | 1978 | 2004 |

| Model No. | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target Variable | E260BBin (Information source: Mobile phone—binary form) | E260BBin | E260BBin | E260BBin | E260B (Information source: Mobile phone—scale form) | E260B | E260B |

| Regression Type | OLS | LOGIT | SCOBIT | PROBIT | OLS | OLOGIT | OPROBIT |

| E253B (Information source: Social media) | −0.0740 *** | −0.4186 *** | −0.9218 *** | −0.2417 *** | 0.3305 *** | 0.4410 *** | 0.2557 *** |

| (0.0010) | (0.0063) | (0.0548) | (0.0035) | (0.0038) | (0.0053) | (0.0030) | |

| E254B (Information source: Talk with friends or colleagues) | −0.0443 *** | −0.2651 *** | −0.4785 *** | −0.1557 *** | 0.2092 *** | 0.3117 *** | 0.1810 *** |

| (0.0011) | (0.0064) | (0.0220) | (0.0038) | (0.0040) | (0.0057) | (0.0033) | |

| E259B (Information source: Radio news) | −0.0211 *** | −0.1498 *** | −0.2538 *** | −0.0893 *** | 0.0679 *** | 0.0957 *** | 0.0588 *** |

| (0.0008) | (0.0059) | (0.0137) | (0.0034) | (0.0029) | (0.0047) | (0.0027) | |

| E261B (Information source: E-mail) | −0.0533 *** | −0.6341 *** | −1.7006 *** | −0.3199 *** | 0.2254 *** | 0.3603 *** | 0.2183 *** |

| (0.0008) | (0.0116) | (0.1161) | (0.0054) | (0.0033) | (0.0054) | (0.0032) | |

| X002 (Year of birth) | 0.0028 *** | 0.0203 *** | 0.0341 *** | 0.0121 *** | −0.0093 *** | −0.0134 *** | −0.0082 *** |

| (0.0001) | (0.0006) | (0.0015) | (0.0004) | (0.0003) | (0.0005) | (0.0003) | |

| _cons | −4.2237 *** | −33.7885 *** | −50.5590 *** | −20.5299 *** | 18.4061 *** | ||

| (0.1693) | (1.2081) | (2.4583) | (0.7010) | (0.6186) | |||

| lnalpha | −1.1583 *** | ||||||

| (0.0650) | |||||||

| cut1 | −22.8815 *** | −14.0814 *** | |||||

| (0.9543) | (0.5605) | ||||||

| cut2 | −22.1901 *** | −13.6788 *** | |||||

| (0.9544) | (0.5605) | ||||||

| cut3 | −21.8614 *** | −13.4884 *** | |||||

| (0.9544) | (0.5606) | ||||||

| cut4 | −21.4249 *** | −13.2367 *** | |||||

| (0.9543) | (0.5605) | ||||||

| N | 87,741 | 87,741 | 87,741 | 87,741 | 87,741 | 87,741 | 87,741 |

| chi-squared | 17,218.9490 | 19,397.2846 | 30,872.9575 | 34,542.1763 | |||

| p | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| R-squared | 0.3287 | 0.3320 | 0.3285 | 0.3983 | 0.1890 | 0.1891 | |

| AIC | 70,518.3523 | 67,801.3760 | 67,457.5315 | 68,153.9530 | 300,462.5556 | 177,927.0057 | 177,884.4839 |

| BIC | 70,574.6452 | 67,857.6689 | 67,523.2065 | 68,210.2458 | 300,518.8485 | 178,011.4450 | 177,968.9232 |

| RMSE | 0.3616 | 1.3408 | |||||

| AUC-ROC | 0.8714 | 0.8708 |

| S002VS (Chronology of Waves) | E260B | E260BBin | E253B | E254B | E259B | E261B | E262B | X002 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1981–1984 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11,324 |

| 1989–1993 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 27,331 |

| 1994–1998 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 76,448 |

| 1999–2004 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 59,979 |

| 2005–2009 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 84,887 |

| 2010–2014 | 85,013 | 85,013 | 0 | 85,242 | 85,262 | 84,826 | 84,974 | 87,315 |

| 2017–2022 | 93,326 | 93,326 | 90,726 | 93,253 | 93,326 | 92,460 | 92,740 | 92,694 |

| Total | 178,339 | 178,339 | 90,726 | 178,495 | 178,588 | 177,286 | 177,714 | 439,978 |

| S003 (Numeric Country Code) | E260B | E260BBin | E253B | E254B | E259B | E261B | E262B | X002 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albania | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1994 |

| Algeria | 1179 | 1179 | 0 | 1178 | 1184 | 1161 | 1165 | 2482 |

| Andorra | 997 | 997 | 1001 | 999 | 1001 | 999 | 999 | 2007 |

| Azerbaijan | 1002 | 1002 | 0 | 1002 | 1002 | 1002 | 1002 | 3003 |

| Argentina | 1995 | 1995 | 759 | 2007 | 2005 | 1966 | 1984 | 7401 |

| Australia | 3206 | 3206 | 0 | 3240 | 3228 | 3209 | 3219 | 7949 |

| Bangladesh | 1183 | 1183 | 1119 | 1172 | 1177 | 1124 | 1128 | 4220 |

| Armenia | 2311 | 2311 | 1218 | 2310 | 2307 | 2307 | 2309 | 4323 |

| Bolivia | 2048 | 2048 | 2025 | 2059 | 2064 | 2021 | 2030 | 2067 |

| Bosnia Herzegovina | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1200 |

| Brazil | 3208 | 3208 | 1729 | 3219 | 3216 | 3193 | 3212 | 5889 |

| Bulgaria | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2073 |

| Myanmar | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 |

| Belarus | 1515 | 1515 | 0 | 1517 | 1523 | 1503 | 1517 | 4642 |

| Canada | 4018 | 4018 | 4018 | 4018 | 4018 | 4018 | 4018 | 11,076 |

| Chile | 1978 | 1978 | 990 | 1984 | 1990 | 1983 | 1986 | 6700 |

| China | 5124 | 5124 | 3023 | 5125 | 5119 | 5106 | 5120 | 10,827 |

| Taiwan | 2448 | 2448 | 1223 | 2440 | 2451 | 2452 | 2450 | 4459 |

| Colombia | 3028 | 3028 | 1520 | 3031 | 3031 | 3026 | 3026 | 12,069 |

| Croatia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1191 |

| Cyprus | 1986 | 1986 | 988 | 1982 | 1975 | 1967 | 1971 | 3048 |

| Czechia | 1193 | 1193 | 1195 | 1195 | 1194 | 1192 | 1194 | 3271 |

| Dominican Rep. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 414 |

| Ecuador | 2397 | 2397 | 1184 | 2396 | 2398 | 2391 | 2390 | 2402 |

| El Salvador | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1254 |

| Ethiopia | 1206 | 1206 | 1099 | 1189 | 1209 | 1086 | 1095 | 2730 |

| Estonia | 1497 | 1497 | 0 | 1516 | 1523 | 1511 | 1518 | 2554 |

| Finland | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2000 |

| France | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1001 |

| Georgia | 1200 | 1200 | 0 | 1201 | 1201 | 1200 | 1200 | 4710 |

| Palestine | 995 | 995 | 0 | 993 | 998 | 993 | 995 | 1000 |

| Germany | 3563 | 3563 | 1527 | 3571 | 3574 | 3566 | 3568 | 7657 |

| Ghana | 1552 | 1552 | 0 | 1552 | 1552 | 1552 | 1552 | 3086 |

| Greece | 1197 | 1197 | 1119 | 1199 | 1196 | 1113 | 1116 | 1200 |

| Guatemala | 1189 | 1189 | 1198 | 1193 | 1185 | 1184 | 1186 | 2229 |

| Haiti | 1937 | 1937 | 0 | 1937 | 1937 | 1938 | 1938 | 0 |

| Hong Kong | 2075 | 2075 | 2075 | 2075 | 2075 | 2073 | 2073 | 3237 |

| Hungary | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1656 |

| India | 4078 | 4078 | 0 | 4078 | 4078 | 4078 | 4078 | 12,525 |

| Indonesia | 3164 | 3164 | 2980 | 3198 | 3182 | 2959 | 2990 | 6214 |

| Iran | 1495 | 1495 | 1496 | 1498 | 1497 | 1496 | 1496 | 6681 |

| Iraq | 2378 | 2378 | 1188 | 2387 | 2369 | 2356 | 2366 | 7426 |

| Israel | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1191 |

| Italy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1012 |

| Japan | 3734 | 3734 | 1330 | 3755 | 3737 | 3730 | 3734 | 9523 |

| Kazakhstan | 2731 | 2731 | 1222 | 2713 | 2724 | 2716 | 2723 | 2776 |

| Jordan | 2396 | 2396 | 1198 | 2395 | 2398 | 2394 | 2397 | 4826 |

| Kenya | 1254 | 1254 | 1245 | 1245 | 1253 | 1224 | 1240 | 1259 |

| South Korea | 2421 | 2421 | 1245 | 2427 | 2415 | 2421 | 2424 | 7343 |

| Kuwait | 1225 | 1225 | 0 | 1242 | 1219 | 1219 | 1232 | 1245 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 2694 | 2694 | 1195 | 2691 | 2696 | 2683 | 2691 | 3743 |

| Lebanon | 2377 | 2377 | 1200 | 2379 | 2388 | 2368 | 2379 | 2400 |

| Latvia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1200 |

| Libya | 3267 | 3267 | 1184 | 3278 | 3262 | 3229 | 3250 | 3316 |

| Lithuania | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1009 |

| Macau | 1019 | 1019 | 1018 | 1022 | 1019 | 1016 | 1018 | 813 |

| Malaysia | 2613 | 2613 | 1313 | 2613 | 2613 | 2613 | 2613 | 3813 |

| Maldives | 1038 | 1038 | 1032 | 1031 | 1033 | 1028 | 1029 | 1036 |

| Mali | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1428 |

| Mexico | 3738 | 3738 | 1739 | 3739 | 3741 | 3738 | 3738 | 11,707 |

| Mongolia | 1638 | 1638 | 1638 | 1638 | 1638 | 1638 | 1638 | 1638 |

| Moldova | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3037 |

| Montenegro | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1298 |

| Morocco | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 | 4848 |

| Netherlands | 3895 | 3895 | 1999 | 3852 | 3888 | 3886 | 3895 | 5097 |

| New Zealand | 1748 | 1748 | 980 | 1793 | 1796 | 1744 | 1777 | 3963 |

| Nicaragua | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 |

| Nigeria | 2989 | 2989 | 1217 | 2990 | 2994 | 2981 | 2978 | 7988 |

| Norway | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2152 |

| Pakistan | 3117 | 3117 | 1908 | 3114 | 3105 | 3067 | 3049 | 5919 |

| Peru | 2577 | 2577 | 1368 | 2571 | 2587 | 2557 | 2562 | 6822 |

| Philippines | 2395 | 2395 | 1200 | 2397 | 2396 | 2398 | 2398 | 4800 |

| Poland | 958 | 958 | 0 | 963 | 962 | 958 | 960 | 4052 |

| Puerto Rico | 1099 | 1099 | 1102 | 1106 | 1089 | 1082 | 1105 | 2991 |

| Qatar | 1060 | 1060 | 0 | 1060 | 1060 | 1060 | 1060 | 1053 |

| Romania | 2723 | 2723 | 1218 | 2716 | 2748 | 2685 | 2702 | 5755 |

| Russia | 4177 | 4177 | 1774 | 4245 | 4219 | 4167 | 4213 | 10,342 |

| Rwanda | 1527 | 1527 | 0 | 1527 | 1527 | 1527 | 1527 | 3034 |

| Saudi Arabia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1502 |

| Serbia | 1029 | 1029 | 1027 | 1030 | 1031 | 1029 | 1033 | 4739 |

| Singapore | 3975 | 3975 | 2006 | 3976 | 3976 | 3975 | 3976 | 5463 |

| Slovakia | 1197 | 1197 | 1196 | 1191 | 1195 | 1195 | 1195 | 2761 |

| Vietnam | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 | 3695 |

| Slovenia | 1061 | 1061 | 0 | 1060 | 1065 | 1060 | 1062 | 3100 |

| South Africa | 3531 | 3531 | 0 | 3531 | 3531 | 3531 | 3531 | 16,694 |

| Zimbabwe | 2710 | 2710 | 1179 | 2710 | 2713 | 2676 | 2679 | 3713 |

| Spain | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6319 |

| Sweden | 1194 | 1194 | 0 | 1197 | 1199 | 1197 | 1198 | 7354 |

| Switzerland | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3845 |

| Tajikistan | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 | 1200 |

| Thailand | 2669 | 2669 | 1489 | 2658 | 2662 | 2663 | 2672 | 4216 |

| Trinidad and Tob | 992 | 992 | 0 | 989 | 993 | 985 | 987 | 2000 |

| Tunisia | 2376 | 2376 | 1191 | 2385 | 2403 | 2370 | 2376 | 2410 |

| Turkey | 3997 | 3997 | 2405 | 3996 | 3989 | 3980 | 3995 | 11,686 |

| Uganda | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1002 |

| Ukraine | 2745 | 2745 | 1249 | 2666 | 2705 | 2728 | 2741 | 6587 |

| North Macedonia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2050 |

| Egypt | 2717 | 2717 | 1194 | 2718 | 2722 | 2715 | 2717 | 8770 |

| United Kingdom | 2596 | 2596 | 2598 | 2597 | 2599 | 2594 | 2599 | 4586 |

| Tanzania | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1146 |

| United States | 4729 | 4729 | 2562 | 4735 | 4727 | 4737 | 4720 | 12,962 |

| Burkina Faso | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1479 |

| Uruguay | 1978 | 1978 | 996 | 1977 | 1987 | 1977 | 1985 | 3999 |

| Uzbekistan | 1500 | 1500 | 0 | 1500 | 1500 | 1500 | 1500 | 1500 |

| Venezuela | 1190 | 1190 | 1190 | 1190 | 1190 | 1190 | 1190 | 3590 |

| Yemen | 955 | 955 | 0 | 981 | 989 | 885 | 890 | 1000 |

| Zambia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1500 |

| Northern Ireland | 446 | 446 | 445 | 445 | 446 | 445 | 445 | 414 |

| Total | 178,339 | 178,339 | 90,726 | 178,495 | 178,588 | 177,286 | 177,714 | 439,978 |

| E260B—Information Source: Mobile Phone (B) | Freq. (Before REMDKNA) | Percent (Before REMDKNA) | Cum. (Before REMDKNA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Missing; Unknown | 347 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| Not asked | 270,415 | 59.98 | 60.05 |

| No answer | 1008 | 0.22 | 60.28 |

| Don’t know | 760 | 0.17 | 60.45 |

| Daily | 84,763 | 18.8 | 79.25 |

| Weekly | 18,483 | 4.1 | 83.34 |

| Monthly | 8301 | 1.84 | 85.19 |

| Less than monthly | 11,212 | 2.49 | 87.67 |

| Never | 55,580 | 12.33 | 100 |

| Total | 450,869 | 100 | - |

| E260B—Information Source: Mobile Phone (B) | Freq. (After REMDKNA) | Percent (After REMDKNA) | Cum. (After REMDKNA) |

| Daily | 84,763 | 47.53 | 47.53 |

| Weekly | 18,483 | 10.36 | 57.89 |

| Monthly | 8301 | 4.65 | 62.55 |

| Less than monthly | 11,212 | 6.29 | 68.83 |

| Never | 55,580 | 31.17 | 100 |

| Total | 178,339 | 100 | - |

Appendix C

| Model | Model1 | Model2 | Model3 | Model4 | Model5 | Model6 | Model7 | Model8 | Model9 | Model10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input/Target Var. | E260B | E253B | E260B | E254B | E260B | E259B | E260B | E261B | E260B | X002 |

| E253B (Information source: Social media) | 0.6843 *** | |||||||||

| (−0.0045) | ||||||||||

| E254B (Information source: Talk with friends or colleagues) | 0.5078 *** | |||||||||

| (−0.0035) | ||||||||||

| E259B (Information source: Radio news) | 0.1898 *** | |||||||||

| (−0.0028) | ||||||||||

| E261B (Information source: E-mail) | 0.6046 *** | |||||||||

| (−0.0032) | ||||||||||

| X002 (Year of birth) | −0.0292 *** | |||||||||

| (−0.0003) | ||||||||||

| E260B (Information source: Mobile phone—scale form) | 0.7194 *** | 0.3813 *** | 0.1727 *** | 0.5932 *** | −0.2491 *** | |||||

| (−0.0048) | (−0.0027) | (−0.0026) | (−0.003) | (−0.0024) | ||||||

| N | 90,405 | 90,405 | 177,518 | 177,518 | 177,617 | 177,617 | 176,719 | 176,719 | 174,628 | 174,628 |

| Chi-squared | 23,128.5659 | 22,836.1391 | 20,665.4526 | 20,105.3049 | 4489.8956 | 4286.6316 | 35,243.6861 | 37,867.409 | 11,222.997 | 10,679.8848 |

| P | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| R-squared | 0.1375 | 0.1384 | 0.053 | 0.0459 | 0.0111 | 0.0094 | 0.0925 | 0.0943 | 0.0262 | 0.0076 |

| AIC | 195,027.077 | 197,208.765 | 426,536.286 | 467,382.566 | 445,602.806 | 511,724.316 | 406,784.477 | 421,084.352 | 430,886.692 | 1,445,048.39 |

| BIC | 195,074.137 | 197,255.825 | 426,586.72 | 467,433 | 445,653.243 | 511,774.753 | 406,834.889 | 421,134.764 | 430,937.044 | 1,445,964.8 |

| Model | Model1 | Model2 | Model3 | Model4 | Model5 | Model6 | Model7 | Model8 | Model9 | Model10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input/Target Var. | E260B | E253B | E260B | E254B | E260B | E259B | E260B | E261B | E260B | X002 |

| E253B (Information source: Social media) | 0.4029 *** | |||||||||

| (−0.0025) | ||||||||||

| E254B (Information source: Talk with friends or colleagues) | 0.3053 *** | |||||||||

| (−0.0021) | ||||||||||

| E259B (Information source: Radio news) | 0.1157 *** | |||||||||

| (−0.0017) | ||||||||||

| E261B (Information source: E-mail) | 0.3662 *** | |||||||||

| (−0.0019) | ||||||||||

| X002 (Year of birth) | −0.0181 *** | |||||||||

| (−0.0002) | ||||||||||

| E260B (Information source: Mobile phone—scale form) | 0.4224 *** | 0.2291 *** | 0.1041 *** | 0.3545 *** | −0.1457 *** | |||||

| (−0.0026) | (−0.0016) | (−0.0016) | (−0.0018) | (−0.0014) | ||||||

| N | 90,405 | 90,405 | 177,518 | 177,518 | 177,617 | 177,617 | 176,719 | 176,719 | 174,628 | 174,628 |

| Chi-squared | 25,945.9827 | 25,431.203 | 21,247.3917 | 21,521.2876 | 4594.0689 | 4412.5131 | 37,695.6852 | 38,542.2283 | 11,556.7561 | 11,130.298 |

| p | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| R-squared | 0.1355 | 0.1347 | 0.0516 | 0.047 | 0.0111 | 0.0094 | 0.0932 | 0.0941 | 0.0264 | 0.0079 |

| AIC | 195,461.138 | 198,055.951 | 427,136.336 | 466,861.672 | 445,629.349 | 511,758.999 | 406,463.445 | 421,156.312 | 430,780.016 | 144,4671.88 |

| BIC | 195,508.199 | 198,103.011 | 427,186.77 | 466,912.106 | 445,679.786 | 511,809.436 | 406,513.857 | 421,206.723 | 430,830.368 | 1,445,588.29 |

| MELOGIT/MEOLOGIT | Model1 | Model2 | Model3 | Model4 | Model5 | Model6 | Model7 | Model8 | Model9 | Model10 | Model11 | Model12 | Model13 | Model14 | Model15 | Model16 | Model17 | Model18 | Model19 | Model20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | E260BBin | E260BBin | E260BBin | E260BBin | E260BBin | E260BBin | E260BBin | E260BBin | E260BBin | E260BBin | E260B | E260B | E260B | E260B | E260B | E260B | E260B | E260B | E260B | E260B |

| E253B (Information source: Social media) | −0.4186 *** | −0.4179 *** | −0.4213 *** | −0.4169 *** | −0.4175 *** | −0.4166 *** | −0.4138 *** | −0.4152 *** | −0.4384 *** | −0.4162 *** | 0.4408 *** | 0.4382 *** | 0.4422 *** | 0.4385 *** | 0.4403 *** | 0.4401 *** | 0.4407 *** | 0.4390 *** | 0.4589 *** | 0.4371 *** |

| (−0.026) | (−0.0066) | (−0.0108) | (−0.0077) | (−0.0521) | (−0.0149) | (−0.0137) | (−0.0197) | (−0.0298) | (−0.023) | (−0.0194) | (−0.0074) | (−0.0158) | (−0.0132) | (−0.0271) | (−0.009) | (−0.0119) | (−0.0141) | (−0.0282) | (−0.0169) | |

| E254B (Information source: Talk with friends or colleagues) | −0.2650 *** | −0.2628 *** | −0.2640 *** | −0.2663 *** | −0.2656 *** | −0.2636 *** | −0.2644 *** | −0.2672 *** | −0.2579 *** | −0.2697 *** | 0.3122 *** | 0.3101 *** | 0.3101 *** | 0.3127 *** | 0.3120 *** | 0.3121 *** | 0.3127 *** | 0.3134 *** | 0.2974 *** | 0.3150 *** |

| (−0.0286) | (−0.0081) | (−0.0046) | (−0.0088) | (−0.0232) | (−0.0196) | (−0.0064) | (−0.0145) | (−0.0163) | (−0.0165) | (−0.0181) | (−0.0067) | (−0.0051) | (−0.006) | (−0.0145) | (−0.0116) | (−0.0057) | (−0.0137) | (−0.0159) | (−0.0181) | |

| E259B (Information source: Radio news) | −0.1498 *** | −0.1524 *** | −0.1510 *** | −0.1522 *** | −0.1491 *** | −0.1493 *** | −0.1459 *** | −0.1494 *** | −0.1688 *** | −0.1577 *** | 0.0963 *** | 0.0963 *** | 0.0961 *** | 0.0973 *** | 0.0951 *** | 0.0958 *** | 0.0887 *** | 0.0944 *** | 0.1086 *** | 0.0977 *** |

| (−0.0115) | (−0.008) | (−0.012) | (−0.0089) | (−0.0049) | (−0.0115) | (−0.0075) | (−0.0119) | (−0.0129) | (−0.0047) | (−0.0107) | (−0.0056) | (−0.0085) | (−0.0077) | (−0.0053) | (−0.01) | (−0.0075) | (−0.0133) | (−0.0122) | (−0.0108) | |

| E261B (Information source: E-mail) | −0.6340 *** | −0.6399 *** | −0.6370 *** | −0.6380 *** | −0.6328 *** | −0.6339 *** | −0.6243 *** | −0.6369 *** | −0.6739 *** | −0.6390 *** | 0.3608 *** | 0.3629 *** | 0.3623 *** | 0.3623 *** | 0.3602 *** | 0.3608 *** | 0.3516 *** | 0.3596 *** | 0.4001 *** | 0.3619 *** |

| (−0.0183) | (−0.0192) | (−0.0078) | (−0.0581) | (−0.0431) | (−0.064) | (−0.0369) | (−0.0209) | (−0.0614) | (−0.0946) | (−0.0014) | (−0.0061) | (−0.0092) | (−0.0093) | (−0.0214) | (−0.0134) | (−0.0105) | (−0.0135) | (−0.0238) | (−0.042) | |

| X002 (Year of birth) | 0.0202 *** | 0.0262 *** | 0.0211 *** | 0.0186 *** | 0.0203 *** | 0.0174 *** | 0.0196 *** | 0.0202 *** | 0.0231 *** | 0.0201 *** | −0.0134 *** | −0.0242 *** | −0.0142 *** | −0.0125 *** | −0.0134 *** | −0.0115 *** | −0.0130 *** | −0.0133 *** | −0.0150 *** | −0.0134 *** |

| (−0.0012) | (−0.0013) | (−0.0009) | (−0.0028) | (−0.0038) | (−0.0023) | (−0.0013) | (−0.0013) | (−0.0036) | (−0.0049) | (−0.0003) | (−0.0022) | (−0.0009) | (−0.0024) | (−0.0016) | (−0.002) | (−0.0004) | (−0.0018) | (−0.0026) | (−0.0037) | |

| _cons | −33.7671 *** | −45.4276 *** | −35.5040 *** | −30.4154 *** | −33.9865 *** | −28.2662 *** | −32.5541 *** | −33.7607 *** | −39.0467 *** | −33.4129 *** | ||||||||||

| (−2.4971) | (−2.6269) | (−1.8546) | (−5.7798) | (−7.852) | (−4.8731) | (−2.6713) | (−2.5541) | (−7.361) | (−10.0081) | |||||||||||

| var(_cons [X001]) (Gender) | 0.0000 | 0.0004 *** | ||||||||||||||||||

| (0.0000) | (−0.0001) | |||||||||||||||||||

| var(_cons [X003]) (Age) | 0.0360 *** | 0.0455 ** | ||||||||||||||||||

| (−0.0073) | (−0.014) | |||||||||||||||||||

| var(_cons [X007]) (Marital status) | 0.0069 * | 0.0064 * | ||||||||||||||||||

| (−0.0029) | (−0.0027) | |||||||||||||||||||

| var(_cons [X013]) (Number of people in household) | 0.0137 | 0.0299 | ||||||||||||||||||

| (−0.011) | (−0.0333) | |||||||||||||||||||

| var(_cons [X025R]) (Education level) | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | ||||||||||||||||||

| (0.0000) | (0.0000) | |||||||||||||||||||

| var(_cons [X028]) (Employment status) | 0.0108 ** | 0.0056 * | ||||||||||||||||||

| (−0.0034) | (−0.0023) | |||||||||||||||||||

| var(_cons [X045]) (Social class) | 0.0078 *** | 0.0017 ** | ||||||||||||||||||

| (−0.0021) | (−0.0006) | |||||||||||||||||||

| var(_cons [X049]) (Settlement size) | 0.0071 * | 0.0074 ** | ||||||||||||||||||

| (−0.0031) | (−0.0028) | |||||||||||||||||||

| var(_cons [S003]) (Country code) | 0.5129 *** | 0.4610 *** | ||||||||||||||||||

| (−0.1021) | (−0.0887) | |||||||||||||||||||

| var(_cons [S020]) (Year of survey) | 0.0747 | 0.0702 | ||||||||||||||||||

| (−0.0467) | (−0.0416) | |||||||||||||||||||

| N | 87,704 | 87,734 | 87,379 | 87,165 | 87,071 | 86,856 | 82,972 | 86,686 | 87,741 | 87,741 | 87,704 | 87,734 | 87,379 | 87,165 | 87,071 | 86,856 | 82,972 | 86,686 | 87,741 | 87,741 |

| AIC | 67,770.6289 | 67,637.9946 | 67,480.3968 | 67,360.5005 | 67,364.793 | 67,060.8194 | 64,400.5809 | 67,076.2378 | 62,934.8751 | 67,257.6101 | 177,832.158 | 177,699.841 | 177,048.931 | 176,674.575 | 176,551.535 | 176,140.688 | 169,260.844 | 175,691.124 | 170,411.14 | 177,113.989 |

| BIC | 67,789.3924 | 67,703.669 | 67,536.6649 | 67,426.1294 | 67,383.542 | 67,126.4235 | 64,447.2122 | 67,141.8282 | 63,000.5501 | 67,304.5208 | 177,841.54 | 177,793.662 | 177,114.577 | 176,768.331 | 176,579.658 | 176,206.292 | 169,298.149 | 175,775.455 | 170,504.96 | 177,179.664 |

| MEPROBIT/MEOPROBIT | Model1 | Model2 | Model3 | Model4 | Model5 | Model6 | Model7 | Model8 | Model9 | Model10 | Model11 | Model12 | Model13 | Model14 | Model15 | Model16 | Model17 | Model18 | Model19 | Model20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | E260BBin | E260BBin | E260BBin | E260BBin | E260BBin | E260BBin | E260BBin | E260BBin | E260BBin | E260BBin | E260B | E260B | E260B | E260B | E260B | E260B | E260B | E260B | E260B | E260B |

| E253B (Information source: Social media) | −0.2417 *** | −0.2410 *** | −0.2430 *** | −0.2406 *** | −0.2411 *** | −0.2404 *** | −0.2395 *** | −0.2399 *** | −0.2512 *** | −0.2403 *** | 0.2556 *** | 0.2539 *** | 0.2564 *** | 0.2543 *** | 0.2553 *** | 0.2551 *** | 0.2552 *** | 0.2546 *** | 0.2663 *** | 0.2535 *** |

| (−0.0167) | (−0.0038) | (−0.0058) | (−0.0057) | (−0.0319) | (−0.0095) | (−0.0091) | (−0.0107) | (−0.0166) | (−0.0132) | (−0.0118) | (−0.0039) | (−0.0077) | (−0.0072) | (−0.0179) | (−0.0054) | (−0.0075) | (−0.0081) | (−0.0161) | (−0.0096) | |

| E254B (Information source: Talk with friends or colleagues) | −0.1556 *** | −0.1543 *** | −0.1550 *** | −0.1564 *** | −0.1560 *** | −0.1546 *** | −0.1553 *** | −0.1568 *** | −0.1487 *** | −0.1582 *** | 0.1813 *** | 0.1800 *** | 0.1802 *** | 0.1816 *** | 0.1812 *** | 0.1811 *** | 0.1816 *** | 0.1820 *** | 0.1710 *** | 0.1827 *** |

| (−0.0172) | (−0.0047) | (−0.004) | (−0.0057) | (−0.0149) | (−0.0123) | (−0.0045) | (−0.009) | (−0.0096) | (−0.0093) | (−0.0112) | (−0.0039) | (−0.003) | (−0.0038) | (−0.0097) | (−0.007) | (−0.0032) | (−0.0083) | (−0.0093) | (−0.011) | |

| E259B (Information source: Radio news) | −0.0893 *** | −0.0903 *** | −0.0896 *** | −0.0906 *** | −0.0889 *** | −0.0887 *** | −0.0871 *** | −0.0892 *** | −0.0980 *** | −0.0934 *** | 0.0592 *** | 0.0591 *** | 0.0589 *** | 0.0597 *** | 0.0585 *** | 0.0587 *** | 0.0549 *** | 0.0580 *** | 0.0661 *** | 0.0605 *** |

| (−0.0068) | (−0.0046) | (−0.0067) | (−0.0053) | (−0.0015) | (−0.0067) | (−0.004) | (−0.007) | (−0.0074) | (−0.0039) | (−0.0063) | (−0.0034) | (−0.0051) | (−0.0043) | (−0.0025) | (−0.0056) | (−0.0042) | (−0.0076) | (−0.0071) | (−0.0057) | |

| E261B (Information source: E-mail) | −0.3198 *** | −0.3229 *** | −0.3215 *** | −0.3224 *** | −0.3194 *** | −0.3199 *** | −0.3134 *** | −0.3206 *** | −0.3417 *** | −0.3221 *** | 0.2186 *** | 0.2201 *** | 0.2196 *** | 0.2195 *** | 0.2182 *** | 0.2187 *** | 0.2137 *** | 0.2179 *** | 0.2352 *** | 0.2189 *** |

| (−0.0048) | (−0.007) | (−0.0027) | (−0.0192) | (−0.0157) | (−0.0195) | (−0.0161) | (−0.0095) | (−0.0239) | (−0.0404) | (−0.0002) | (−0.0034) | (−0.0047) | (−0.0046) | (−0.0116) | (−0.0083) | (−0.0063) | (−0.0081) | (−0.0133) | (−0.024) | |

| X002 (Year of birth) | 0.0121 *** | 0.0156 *** | 0.0126 *** | 0.0111 *** | 0.0122 *** | 0.0105 *** | 0.0117 *** | 0.0121 *** | 0.0135 *** | 0.0120 *** | −0.0082 *** | −0.0143 *** | −0.0088 *** | −0.0076 *** | −0.0082 *** | −0.0070 *** | −0.0080 *** | −0.0081 *** | −0.0091 *** | −0.0082 *** |

| (−0.0007) | (−0.0008) | (−0.0005) | (−0.0016) | (−0.0022) | (−0.0014) | (−0.0007) | (−0.0007) | (−0.0021) | (−0.0029) | (−0.0002) | (−0.0011) | (−0.0005) | (−0.0015) | (−0.0011) | (−0.0012) | (−0.0003) | (−0.001) | (−0.0016) | (−0.0023) | |

| _cons | −20.5187 *** | −27.3435 *** | −21.6102 *** | −18.5761 *** | −20.6474 *** | −17.3468 *** | −19.8562 *** | −20.4965 *** | −23.1771 *** | −20.4118 *** | ||||||||||

| (−1.4951) | (−1.5225) | (−0.9942) | (−3.3779) | (−4.5297) | (−2.8223) | (−1.4287) | (−1.3829) | (−4.1373) | (−5.8688) | |||||||||||

| var(_cons [X001]) (Gender) | 0.0000 | 0.0002 *** | ||||||||||||||||||

| (0.0000) | (0.0000) | |||||||||||||||||||

| var(_cons[X003]) (Age) | 0.0120 *** | 0.0153 *** | ||||||||||||||||||

| (−0.0024) | (−0.0041) | |||||||||||||||||||

| var(_cons[X007]) (Marital status) | 0.0024 * | 0.0021 * | ||||||||||||||||||

| (−0.001) | (−0.0009) | |||||||||||||||||||

| var(_cons[X013]) (Number of people in household) | 0.0054 | 0.0118 | ||||||||||||||||||

| (−0.0052) | (−0.0124) | |||||||||||||||||||

| var(_cons[X025R]) (Education level) | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | ||||||||||||||||||

| (0.0000) | (0.0000) | |||||||||||||||||||

| var(_cons[X028]) (Employment status) | 0.0037 ** | 0.0021 * | ||||||||||||||||||

| (−0.0012) | (−0.0008) | |||||||||||||||||||

| var(_cons[X045]) (Social class) | 0.0029 ** | 0.0007 ** | ||||||||||||||||||

| (−0.0009) | (−0.0002) | |||||||||||||||||||

| var(_cons[X049]) (Settlement size) | 0.0024 * | 0.0024 ** | ||||||||||||||||||

| (−0.0011) | (−0.0009) | |||||||||||||||||||

| var(_cons[S003]) (Country code) | 0.1660 *** | 0.1538 *** | ||||||||||||||||||

| (−0.0333) | (−0.0285) | |||||||||||||||||||

| var(_cons[S020]) (Year of survey) | 0.0256 | 0.0251 | ||||||||||||||||||

| (−0.0152) | (−0.0144) | |||||||||||||||||||

| N | 87,704 | 87,734 | 87,379 | 87,165 | 87,071 | 86,856 | 82,972 | 86,686 | 87,741 | 87,741 | 87,704 | 87,734 | 87,379 | 87,165 | 87,071 | 86,856 | 82,972 | 86,686 | 87,741 | 87,741 |

| AIC | 68,121.2058 | 67,982.195 | 67,824.8319 | 67,704.6795 | 67,710.0795 | 67,402.0599 | 64,729.7165 | 67,427.8605 | 63,195.3261 | 67,594.3494 | 177,791.077 | 177,645.439 | 177,000.599 | 176,624.35 | 176,505.075 | 176,086.464 | 169,233.635 | 175,649.294 | 170,377.29 | 177,054.715 |

| BIC | 68,130.5875 | 68,047.8695 | 67,881.1 | 67,770.3085 | 67,728.8285 | 67,467.664 | 647,76.3478 | 67,493.4509 | 63,261.0011 | 67,641.2602 | 177,809.84 | 177,739.26 | 177,056.867 | 176,718.105 | 176,523.824 | 176,152.068 | 169,270.94 | 175,724.254 | 170,471.11 | 177,120.39 |

| Number of Hidden Layers | Number of Iterations | Training Factor—Eta | R–square | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 1000 | 0.05 | 0.7296 | 83.3578 |

| 10 | 1000 | 0.15 | 0.7284 | 83.3350 |

| 10 | 1000 | 0.25 | 0.7170 | 82.3617 |

| 10 | 2000 | 0.05 | 0.728 | 83.073 |

| 10 | 2000 | 0.15 | 0.7244 | 82.9658 |

| 10 | 2000 | 0.25 | 0.7143 | 82.5441 |

| 10 | 3000 | 0.05 | 0.7306 | 83.4114 |

| 10 | 3000 | 0.15 | 0.7273 | 83.3681 |

| 10 | 3000 | 0.25 | 0.7214 | 83.0957 |

| 15 | 1000 | 0.05 | 0.7190 | 82.8085 |

| 15 | 1000 | 0.15 | 0.7213 | 82.9749 |

| 15 | 1000 | 0.25 | 0.7219 | 83.2222 |

| 15 | 2000 | 0.05 | 0.7283 | 83.2507 |

| 15 | 2000 | 0.15 | 0.73 | 83.3852 |

| 15 | 2000 | 0.25 | 0.7285 | 83.3841 |

| 15 | 3000 | 0.05 | 0.7305 | 83.4285 |

| 15 | 3000 | 0.15 | 0.7292 | 83.3738 |

| 15 | 3000 | 0.25 | 0.72 | 83.0832 |

| 20 | 1000 | 0.05 | 0.7292 | 83.3761 |

| 20 | 1000 | 0.15 | 0.7213 | 83.0957 |

| 20 | 1000 | 0.25 | 0.7207 | 83.155 |

| 20 | 2000 | 0.05 | 0.7271 | 83.1379 |

| 20 | 2000 | 0.15 | 0.7234 | 83.2416 |

| 20 | 2000 | 0.25 | 0.7163 | 82.902 |

| 20 | 3000 | 0.05 | 0.7235 | 83.2302 |

| 20 | 3000 | 0.15 | 0.7229 | 83.2131 |

| 20 | 3000 | 0.25 | 0.7232 | 83.3373 |

Appendix D

| IVS | EVS Trend File | WVS Trend File | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Survey period | 1981–2022 | 1981–2017 | 1981–2022 |

| Number of waves | 7 | 5 | 7 |

| Number of cases | 663.965 | 224.434 | 442.473 |

| Number of variables | 838 | 635 | 732 |

| Countries/territories | 120 | 49 | 108 |

| Number of surveys | 464 | 160 | 306 |

| Variable | N (Obs.) | Mean | St. Dev. | Min | Median | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E260B | 171,901 | 2.64 | 1.79 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| E260BBin | 171,901 | 0.68 | 0.46 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| E254B | 171,901 | 2.18 | 1.42 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| E259B | 171,901 | 2.83 | 1.7 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| E261B | 171,901 | 3.58 | 1.67 | 1 | 5 | 5 |

| X002 | 171,901 | 1972.73 | 16.81 | 1913 | 1975 | 2004 |

| Model No. | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target Variable | E260BBin | E260BBin | E260BBin | E260BBin | E260B | E260B | E260B |

| Regression Type | OLS | LOGIT | SCOBIT | PROBIT | OLS | OLOGIT | OPROBIT |

| E254B (Information source: Talk with friends or colleagues) | −0.0561 *** | −0.2827 *** | −0.5311 *** | −0.1692 *** | 0.2671 *** | 0.3530 *** | 0.2078 *** |

| (0.0008) | (0.0041) | (0.0163) | (0.0025) | (0.0029) | (0.0039) | (0.0023) | |

| E259B (Information source: Radio news) | −0.0221 *** | −0.1246 *** | −0.2335 *** | −0.0749 *** | 0.0710 *** | 0.0932 *** | 0.0567 *** |

| (0.0006) | (0.0037) | (0.0095) | (0.0022) | (0.0023) | (0.0032) | (0.0019) | |

| E261B (Information source: E-mail) | −0.0884 *** | −0.6411 *** | −1.7086 *** | −0.3490 *** | 0.3662 *** | 0.4825 *** | 0.2911 *** |

| (0.0006) | (0.0058) | (0.0719) | (0.0029) | (0.0023) | (0.0034) | (0.0020) | |

| X002 (Year of birth) | 0.0053 *** | 0.0301 *** | 0.0544 *** | 0.0182 *** | −0.0202 *** | −0.0260 *** | −0.0158 *** |

| (0.0001) | (0.0004) | (0.0015) | (0.0002) | (0.0002) | (0.0003) | (0.0002) | |

| _cons | −9.3355 *** | −54.9435 *** | −94.2903 *** | −33.3224 *** | 40.4795 *** | ||

| (0.1208) | (0.7245) | (2.4669) | (0.4211) | (0.4431) | |||

| lnalpha | −1.1989 *** | ||||||

| (0.0407) | |||||||

| cut1 | −48.7565 *** | −29.5915 *** | |||||

| (0.5999) | (0.3570) | ||||||

| cut2 | −48.2092 *** | −29.2648 *** | |||||

| (0.5998) | (0.3569) | ||||||

| cut3 | −47.9520 *** | −29.1118 *** | |||||

| (0.5997) | (0.3569) | ||||||

| cut4 | −47.5784 *** | −28.8906 *** | |||||

| (0.5995) | (0.3568) | ||||||

| N | 171,901 | 171,901 | 171,901 | 171,901 | 171,901 | 171,901 | 171,901 |

| Chi-squared | 29,375.6194 | 34,000.0736 | 46,704.8809 | 50,964.0623 | |||

| p | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| R-squared | 0.2490 | 0.2319 | 0.2298 | 0.2919 | 0.1335 | 0.1339 | |

| AIC | 175,061.6152 | 164,571.0977 | 163,971.2185 | 165,014.1210 | 628,085.6018 | 377,315.8048 | 377,144.2028 |

| BIC | 175,111.8885 | 164,621.3710 | 164,031.5465 | 165,064.3944 | 628,135.8752 | 377,396.2421 | 377,224.6402 |

| RMSE | 0.4026 | 1.5037 | |||||

| AUC-ROC | 0.8160 | 0.8151 |

| Recommendation | Potential Costs | Expected Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Subsidized internet and data plans | Requires government funding or telecom partnerships; potential revenue loss for providers | Increases digital inclusion, enabling access to vital services like education and healthcare |

| Offline-accessible mobile apps | Development and maintenance costs; limited content updates | Ensures access to critical information without constant internet connectivity |

| Peer-led digital literacy programs | Training costs; requires community engagement efforts | Empowers users with mobile skills, increasing adoption and effective usage |

| Simplified user interfaces | Development costs for app redesign; potential limitations in functionality | Enhances accessibility for users with low literacy, improving engagement |

| Infrastructure investment in rural areas | High initial costs for network expansion and maintenance | Reduces urban-rural digital divide, enabling equitable access to mobile technology |

| Public–private partnerships | Requires negotiation and long-term collaboration | Shares costs between stakeholders, ensuring sustainable solutions for mobile accessibility |

| Intervention | ΔP (Delta Probability—Example) | Design/Policy Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Promote daily email use (E261B) | 0.9 − 0.8 = 0.1 | Integrate email digests to reduce mobile dependency |

| Increase radio news access (E259B) | 0.85 − 0.8 = 0.05 | Cache audio for offline/low-data users |

| Target older users born between 1945 and 1950 (X002) | 0.75 − 0.8 = −0.05 | Prioritize desktop/web interfaces |

| ∑ΔP (Sum of all increases/decreases in ΔP) | 0.1 or 10% |

Appendix E. List of Abbreviations

Appendix E.1. General Acronyms

Appendix E.2. Glossary for Specialized Technical Terms and Corresponding Acronyms

References

- Ali, I.; Warraich, N.F. Modeling the process of personal digital archiving through ubiquitous and desktop devices: A systematic review. J. Librariansh. Inf. Sci. 2022, 54, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsmadi, A.A.; Shuhaiber, A.; Alhawamdeh, L.N.; Alghazzawi, R.; Al-Okaily, M. Twenty years of mobile banking services development and sustainability: A bibliometric analysis overview (2000–2020). Sustainability 2022, 14, 10630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, P.; Grewal, H.S.; Singhal, C.; Kargeti, H. Evaluating the webrooming behaviour for mobile phones. Int. J. Bus. Innov. Res. 2022, 27, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okmi, M.; Por, L.Y.; Ang, T.F.; Al-Hussein, W.; Ku, C.S. A systematic review of mobile phone data in crime applications: A coherent taxonomy based on data types and analysis perspectives, challenges, and future research directions. Sensors 2023, 23, 4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, L.E.; Waite, B.M.; Bowman, L.L. Mobile media use, multitasking and distractibility. Int. J. Cyber Behav. Psychol. Learn. 2012, 2, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher, V.; Hatala, M.; Gašević, D. When Do Learners Study? An Analysis of the Time-of-Day and Weekday-Weekend Usage Patterns of Learning Management Systems from Mobile and Computers in Blended Learning. J. Learn. Anal. 2022, 9, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.Y.; Tsoi, Y.Y.; Rhim, A.H.R.; Chiu, D.K.; Lung, M.M.W. Changes in habits of electronic news usage on mobile devices in university students: A comparative survey. Libr. Hi Tech 2022, 40, 1322–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neggaz, I.; Neggaz, N.; Fizazi, H. Boosting Archimedes optimization algorithm using trigonometric operators based on feature selection for facial analysis. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 3903–3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderlund, C.; Lundin, J. What is an information source? Information design based on information source selection behavior. Commun. Des. Q. Rev. 2017, 4, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, A.S.; Goodwin, R. E-commerce smartphone application. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2012, 3, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, M.; Jan, M.T. Factors influencing the use of m-commerce: An extended technology acceptance model perspective. Int. J. Econ. Manag. Account. 2018, 26, 157–183. [Google Scholar]

- Taneja, B. The Digital Edge for M-Commerce to Replace E-Commerce. In Emerging Challenges, Solutions, and Best Practices for Digital Enterprise Transformation; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 299–318. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z. An empirical study on consumers’ intention to purchase mobile apps. Inf. Dev. 2016, 32, 301–312. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, H.; Yen, D.C. Mobile e-commerce: A review and research agenda. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103168. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.T.; Wang, X.D. Socialization, Traffic Distribution and E-Commerce Trends: An Interpretation of the “Pinduoduo” Phenomenon. China Econ. 2019, 14, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowicz, W.; Cuthbertson, R. Introduction to the special issue information technology in retail: Toward omnichannel retailing. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2014, 18, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, J.R.; AlQahtani, S.A.; Nekovee, M. FinTech enablers, use cases, and role of future internet of things. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2023, 35, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.N. A Proposed Taxonomy of Cybersecurity Risk in Mobile Applications. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Comput. Technol. 2022, 1, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, X.; Wang, F.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, T.; Chen, H. Personalized Recommendation of Location-Based Services Using Spatio-Temporal-Aware Long and Short Term Neural Network. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 39864–39874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Lu, Y.; Wei, K.K.; Zhang, J. Understanding customer satisfaction and loyalty: An empirical study of mobile instant messages in China. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 44, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almtiri, Z.; Miah, S.J.; Noman, N. Application of E-commerce Technologies in Accelerating the Success of SME Operation. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Congress on Information and Communication Technology, Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, London, UK, 21–24 February 2022; Springer: Singapore, 2023; Volume 448, pp. 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homocianu, D. Investigating Patterns in mobile phone usage: An empirical exploration using multiple techniques. Inf. Theory Res. eJournal 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushlev, K.; Proulx, J.D. The social costs of ubiquitous information: Consuming information on mobile phones is associated with lower trust. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0162130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, D. Adult literacy benefits? New opportunities for research into sustainable development. Int. Rev. Educ. 2016, 62, 751–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X. Trust and financial inclusion: A cross-country study. Financ. Res. Lett. 2020, 35, 101310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.J.; binti Zahari, N.S.H.; Chew, Y.H. The design of social media mobile application interface for the elderly. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Conference on Open Systems (ICOS), Langkawi, Malaysia, 21–22 November 2018; pp. 104–108. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; May, A. A comparison of field-based and lab-based experiments to evaluate user experience of personalised mobile devices. Adv. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2013, 2013, 619767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, K.; Li, B.; Bernal-Cárdenas, C.; Jelf, D.; Poshyvanyk, D. Automated reporting of GUI design violations for mobile apps. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Software Engineering, Gothenburg, Sweden, 27 May–3 June 2018; pp. 165–175. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge, K.; Ashurst, S. Technology Applied: A Business Leader’s Guide to Software, Systems and IT Projects; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kornelakis, A.; Petrakaki, D. Technological innovation, industry platforms or financialization? A comparative institutional perspective on Nokia, Apple, and Samsung. Bus. Hist. 2024, 66, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehan, M.; Kim, D.J.; Lee, J. Are there any relationships between technology and cultural values? A country-level trend study of the association between information communication technology and cultural values. Inf. Manag. 2018, 55, 725–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litorp, H.; Kågesten, A.; Båge, K.; Uthman, O.A.; Nordenstedt, H.; Fagbemi, M.; Puranen, B.; Ekström, A.M. Gender norms and women’s empowerment as barriers to facility birth: A population-based cross-sectional study in 26 Nigerian states using the World Values Survey. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0272708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dall’Agnola, J. Smartphones and public support for LGBTQ+ in Central Asia. Cent. Asian Surv. 2023, 43, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoeven, P. The Innovation of Values: Exploring the role of news media exposure and communication in moral progress in The Netherlands. Mass Commun. Soc. 2022, 27, 173–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.R. Shifting values. Comp. Sociol. 2023, 22, 639–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhizkari, S. Exploring the role of female egalitarian values in the 2022 protests in Iran, using data from the World Values Survey. Int. Rev. Sociol./Rev. Int. Sociol. 2024, 34, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndofirepi, T.M.; Steyn, R. Income elasticity of information technology and financial emancipation in South Africa. Deleted J. 2023, 58, 539–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, M.; Kar, A.K. Dress to impress and serve well to prevail—Modelling regressive discontinuance for social networking sites. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2024, 76, 102756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasarao, U.; Sharaff, A. Sentiment analysis from email pattern using feature selection algorithm. Expert Syst. 2021, 41, e12867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, P.; Sathiyanarayanan, M.; Proença, H.P. A novel and secured email classification and emotion detection using hybrid deep neural network. Int. J. Cogn. Comput. Eng. 2024, 5, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, R.M.A. A lifelong spam emails classification model. Appl. Comput. Inform. 2020, 20, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayo, F.E.; Ogundele, L.A.; Olakunle, S.; Awotunde, J.B.; Kasali, F.A. A hybrid correlation-based deep learning model for email spam classification using fuzzy inference system. Decis. Anal. J. 2023, 10, 100390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, M.; Imam, M.O.; Javed, M.F.; Murtza, I. Improving spam email classification accuracy using ensemble techniques: A stacking approach. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2023, 23, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tusher, E.H.; Ismail, M.A.; Rahman, M.A.; Alenezi, A.H.; Uddin, M. Email spam: A comprehensive review of optimize detection methods, challenges, and open research problems. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 143627–143657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandrić, P.; Knox, J.; Besley, T.; Ryberg, T.; Suoranta, J.; Hayes, S. Postdigital science and education. Educ. Philos. Theory 2018, 50, 893–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ortiz, P.J.; Browne, J.; Franklin, D.; Oliver, J.Y.; Geyer, R.; Zhou, Y.; Chong, F.T. Smartphone Evolution and Reuse: Establishing a More Sustainable model. In Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Parallel Processing, San Diego, CA, USA, 13–16 September 2010; pp. 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallis, C.J.; Nguyen, H.T.; Norman, A. Cross-cultural adaptation of educational design patterns at scale. J. Work. Appl. Manag. 2024, 16, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westlund, O. The Production and Consumption of News in an age of Mobile Media: Reflections on the Transistor Radio. In The Routledge Companion to Mobile Media; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 135–145. [Google Scholar]

- Mhagama, P. Expanding access and participation through a combination of community radio and mobile phones: The experience of Malawi. J. Afr. Media Stud. 2015, 7, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karnowski, V.; Knop-Huelss, K.; Olbermann, Z. Mobile news access, mobile news repertoires, and users’ tendency to talk about the news—An experience sampling study on mobile news consumption. Online Media Glob. Commun. 2024, 3, 213–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrose, D. Social and Mobile Media in Times of Disaster. In Transnational Broadcasting in the Indo Pacific; Wake, A., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bivens, R.K. The Internet, Mobile Phones and Blogging. Journal. Pract. 2008, 2, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirakulwanich, A.; Sawmong, S. Factors Influencing Shoppers’ Behavioral Intention to Purchase Smart Phones: Digital Transformation Through YouTube User Generated Content. In Innovations in Digital Economy. SPBPU IDE 2021. Communications in Computer and Information Science; Rodionov, D., Kudryavtseva, T., Skhvediani, A., Berawi, M.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, R.R.; Bargavi, S.M. Virtual Smartphones: Exploring the Evolution and Impact of Virtualization Technology on Mobile Devices. Asian J. Basic Sci. Res. 2024, 6, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duy, H.V.; Xuan, T.N.; Huyen, T.H.M.; Dinh, T.N.; Khanh, T.N.; Quy, T.H.; Hai, P.B.; Van, T.T.; Tran, T. Deploying Virtual Desktop Infrastructure with Open-Source Platform for Higher Education. In Creative Approaches Towards Development of Computing and Multidisciplinary IT Solutions for Society; Bijalwan, A., Bennett, R., Jyotsna, G.B., Mohanty, S.N., Eds.; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, P. The Impact of Mobile Broadband and Internet Bandwidth on Human Development—A Comparative Analysis of Developing and Developed Countries. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 15, 16419–16453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimalkumar, M.; Singh, J.B.; Sharma, S.K. Exploring the Multi-Level Digital Divide in Mobile Phone adoption: A comparison of Developing nations. Inf. Syst. Front. 2020, 23, 1057–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elena-Bucea, A.; Cruz-Jesus, F.; Oliveira, T.; Coelho, P.S. Assessing the role of age, education, gender and income on the digital Divide: Evidence for the European Union. Inf. Syst. Front. 2020, 23, 1007–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smale, W.T.; Hutcheson, R.; Russo, C.J. Cell phones, student rights, and school safety: Finding the right balance. Can. J. Educ. Adm. Policy 2021, 195, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoehle, H.; Zhang, X.; Venkatesh, V. An espoused cultural perspective to understand continued intention to use mobile applications: A four-country study of mobile social media application usability. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2015, 24, 337–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L. Analysis of Japanese cultural patterns—Based on Hofstede’s value dimensions and Minkov’s cultural dimensions. Int. J. Educ. Humanit. 2024, 14, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkin, R.S. Masculinity-Femininity Applied to Cooperative and Competitive Facework. In Saving Face in Business; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matusitz, J.; Musambira, G. Power Distance, Uncertainty Avoidance, and Technology: Analyzing Hofstede’s Dimensions and Human Development Indicators. J. Technol. Hum. Serv. 2013, 31, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y. The effect of principal transformational leadership on teacher innovative behavior: The moderator role of uncertainty avoidance and the mediated role of the sense of meaning at work. Front. Educ. 2024, 9, 1378615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Lou, L. A Study on Cross-Cultural Business Communication Based on Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions Theory. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2024, 12, 352–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichbroth, P. Usability Testing of Mobile Applications: A Methodological framework. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazdaloglu, A.E.; Yildiz, K.C.; Pekpazar, A.; Calisir, F.; Gumussoy, C.A. Conceptualization and survey instrument development for mobile application usability. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2024, 24, 555–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Sykes, T.A.; Ackerman, P.L. Individual reactions to new technologies in the workplace: The role of gender as a psychological construct. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 34, 445–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Masculinity at the national cultural level. In APA Handbook of Men and Masculinities; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; pp. 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, K.; Naoual, O.T. Leveraging technology for equity: A literature review on e-inclusion and its potential to advance young people’s socioeconomic inclusion. Rev. Int. Rech. Sci. 2024, 2, 1936–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyram, S. Future directions for context in ICT4D: A systematic literature review. Inf. Dev. 2024, 35, 02666669241248149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattison, M.; Stedmon, A.W. Inclusive design and human factors: Designing mobile phones for older users. PsychNology J. 2006, 4, 267–284. [Google Scholar]

- Iancu, I.; Iancu, B. Designing mobile technology for elderly. A theoretical overview. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 155, 119977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, F.R.; Silva, A.; Barbosa, F.; Silva, A.P.; Metrôlho, J.C. Mobile applications for accessible tourism: Overview, challenges and a proposed platform. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2018, 19, 29–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussou, M.; Katifori, A. Flow, Staging, Wayfinding, Personalization: Evaluating User Experience with Mobile Museum Narratives. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2018, 2, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasemsarn, K.; Sawadsri, A.; Harrison, D.; Nickpour, F. Museums For Older Adults and Mobility-Impaired People: Applying Inclusive Design Principles and Digital Storytelling Guidelines—A Review. Heritage 2024, 7, 1893–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, C.S.; Lim, W.M.; Teh, P.-L. Designing age-friendly mobile apps: Insights from a Mobility App Study. Act. Adapt. Aging 2023, 48, 409–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Bossini, J.-M.; Moreno, L. Accessibility to mobile interfaces for older people. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2014, 27, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, C.; Holland, F. Young peoples’ lived experiences of shifts between face-to-face and smartphone interactions: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. J. Youth Stud. 2022, 27, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.J. Television versus the Internet for Information Seeking: Lessons from Global Survey Research. Int. J. Commun. 2017, 11, 4744–4756. [Google Scholar]

- Karale, A. The challenges of IoT addressing security, ethics, privacy, and laws. Internet Things 2021, 15, 100420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, N.; Howlett, M.; Taeihagh, A. Why and how does the regulation of emerging technologies occur? Explaining the adoption of the EU General Data Protection Regulation using the multiple streams framework. Regul. Gov. 2021, 15, 1020–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavin, B.P.; Karki, S.; Hemalatha, S.; Singh, D.; Vijayalakshmi, R.; Thangamani, M.; Haleem, S.L.A.; Jose, D.; Tirth, V.; Kshirsagar, P.R.; et al. Machine Learning-Based secure data acquisition for fake accounts detection in future mobile communication networks. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2022, 2022, 6356152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinko, M.; Qalandar, S.; Randall, D.; Wulf, V. Nationalizing the internet to break a protest movement: Internet Shutdown and Counter-Appropriation in Iran of late 2019. In Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 28 September–1 October 2022; Volume 6, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selby, J. Data localization laws: Trade barriers or legitimate responses to cybersecurity risks, or both? Int. J. Law Inf. Technol. 2017, 25, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.D. “Data localization”: The internet in the balance. Telecommun. Policy 2020, 44, 102003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airinei, D.; Homocianu, D. Cloud computing based web applications. Examples and considerations on google apps script. In Proceedings of the IE 2017 International Conference, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 21–25 August 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lula, P.; Dospinescu, O.; Homocianu, D.; Sireteanu, N. An advanced analysis of cloud computing concepts based on the computer science ontology. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2021, 66, 2425–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garba, A.; Dwivedi, A.D.; Kamal, M.; Srivastava, G.; Tariq, M.; Hasan, M.A.; Chen, Z. A digital rights management system based on a scalable blockchain. Peer-to-Peer Netw. Appl. 2020, 14, 2665–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edam-Agbor, I.B.; Akin-Fakorede, O.O. Digital rights management (DRM) and digital privacy of online resources in academic libraries in Cross River State. Libr. Inf. Perspect. Res. 2025, 7, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R. Unplugging the threat: How internet addiction among adolescents undermines learning behavior. SN Soc. Sci. 2024, 4, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirish, A.; Srivastava, S.C.; Chandra, S. Impact of mobile connectivity and freedom on fake news propensity during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-country empirical examination. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2021, 30, 322–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, D.; Fathi, R.; Fiedrich, F.; Van De Walle, B.; Comes, T. On the Interplay of Data and Cognitive Bias in Crisis Information Management. Inf. Syst. Front. 2022, 26, 391–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, N. Electoral management of digital campaigns and disinformation in East and Southeast Asia. Elect. Law J. Rules Politics Policy 2020, 19, 214–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanishyn, A.; Malytska, O.; Goncharuk, V. AI-driven disinformation: Policy recommendations for democratic resilience. Front. Artif. Intell. 2025, 8, 1569115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roumeliotis, K.I.; Tselikas, N.D.; Nasiopoulos, D.K. Next-Generation spam filtering: Comparative Fine-Tuning of LLMs, NLPs, and CNN models for email spam classification. Electronics 2024, 13, 2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottola, G.; Cocconcelli, M. Nomograms in the history and education of machine Mechanics. Found. Sci. 2023, 29, 125–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Liu, Y.; Tong, T.; Liu, Y. Development, validation and visualization of a web-based nomogram for predicting risk of new-onset diabetes after percutaneous coronary intervention. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Zhu, S.; Wang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Mo, X.; Xu, W.; Xu, Z. Development, validation, and visualization of a novel nomogram to predict depression risk in patients with stroke. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 365, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homocianu, D.; Plopeanu, A.; Florea, N.; Andrieș, A.M. Exploring the Patterns of Job Satisfaction for Individuals Aged 50 and over from Three Historical Regions of Romania. An Inductive Approach with Respect to Triangulation, Cross-Validation and Support for Replication of Results. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homocianu, D. Global Patterns of Parental Concerns about Children’s Education: Insights from WVS Data. Societies 2025, 15, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabulut, E.M.; Ibrikci, T. Analysis of Cardiotocogram Data for Fetal Distress Determination by Decision Tree-Based Adaptive Boosting Approach. J. Comput. Commun. 2014, 2, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, C. Spatial air quality index prediction model based on decomposition, adaptive boosting, and three-stage feature selection: A case study in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 265, 121777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staerk, C.; Mayr, A. Randomized boosting with multivariable base-learners for high-dimensional variable selection and prediction. BMC Bioinform. 2021, 22, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homocianu, D. An approach to automatically remove negatively coded Do Not Know/No Answer values in some Stata datasets. Data Sci. Data Anal. Inform. eJournal 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsikriktsis, N.A. Review of techniques for treating missing data in OM survey research. J. Oper. Manag. 2005, 24, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuña, E.; Rodriguez, C. The treatment of missing values and its effect on classifier accuracy. In Classification, Clustering, and Data Mining Applications. Studies in Classification, Data Analysis, and Knowledge Organisation; Banks, D., McMorris, F.R., Arabie, P., Gaul, W., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 639–647. [Google Scholar]

- Osman, M.S.; Abu-Mahfouz, A.M.; Page, P.R. A survey on Data Imputation Techniques: Water Distribution System as a use case. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 63279–63291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, B. A systematic review of generative adversarial imputation network in missing data imputation. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 19685–19705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homocianu, D.; Airinei, D. PCDM and PCDM4MP: New Pairwise Correlation-Based Data Mining Tools for Parallel Processing of Large Tabular Datasets. Mathematics 2022, 10, 2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanberry, B.B. Practical guide for retaining correlated climate variables and unthinned samples in species distribution modeling, using random forests. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 79, 102406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Sun, J.; Feng, Y. PCABM: Pairwise Covariates-Adjusted Block Model for Community Detection. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2023, 119, 2092–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrens, A.; Hansen, C.B.; Schaffer, M.E. Lassopack: Model selection and prediction with regularized regression in Stata. Stata J. Promot. Commun. Stat. Stata 2020, 20, 176–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Adaptive lasso variable selection method for semiparametric spatial autoregressive panel data model with random effects. Commun. Stat.-Theory Methods 2022, 53, 2122–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogundimu, E.O. On Lasso and adaptive Lasso for non-random sample in credit scoring. Stat. Model. 2022, 24, 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBruine, L.M.; Barr, D.J. Understanding Mixed-Effects Models through data simulation. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 4, 251524592096511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukaka, M.M. A guide to appropriate use of correlation coefficient in medical research. Malawi Med. J. 2012, 24, 69–71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation coefficients: Appropriate use and interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vatcheva, K.P.; Lee, M.J.; McCormick, J.B.; Rahbar, M.H. Multi-collinearity in Regression Analyses Conducted in Epidemio-545 logic Studies. Epidemiology 2016, 6, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imdadullah, M.; Aslam, M.; Altaf, S. mctest: An R Package for Detection of Collinearity among Regressors. R J. 2016, 8, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, R.J.; Wilson, W.J.; Sa, P. Regression Analysis: Statistical Modeling of a Response Variable; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tîrnăucă, C.; Homocianu, D. Pairwise collinearity detection using parallel algorithms. Preliminary details. Comput. Theory eJournal 2024, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H. Multicollinearity and misleading statistical results. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2019, 72, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homocianu, D.; Tîrnăucă, C. MEM and MEM4PP: New Tools Supporting the Parallel Generation of Critical Metrics in the Evaluation of Statistical Models. Axioms 2022, 11, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, R. Comparison of the binary logistic and skewed logistic (Scobit) models of injury severity in motor vehicle collisions. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2016, 88, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, E.L.; Astin, A.W. Statistical alternatives for studying college student retention: A comparative analysis of logit, probit, and linear regression. Res. High. Educ. 1993, 34, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullerton, A.S. A conceptual framework for ordered logistic regression models. Sociol. Methods Res. 2009, 38, 306–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daykin, A.R.; Moffatt, P.G. Analyzing ordered responses: A review of the ordered probit model. Underst. Stat. Stat. Issues Psychol. Educ. Soc. Sci. 2002, 1, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, K. Using Information Criteria Under Missing Data: Full Information Maximum Likelihood Versus Two-Stage Estimation. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2021, 28, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jann, B. Making regression tables simplified. Stata J. Promot. Commun. Stat. Stata 2007, 7, 227–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlotnik, A.; Abraira, V.A. General-purpose nomogram generator for predictive logistic regression models. Stata J. Promot. Commun. Stat. Stata 2015, 15, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, N.H.; Reaz, M.B.I.; Ali, S.H.M.; Ahmad, S.; Crespo, M.L.; Cicuttin, A.; Haque, F.; Bakar, A.A.A.; Bhuiyan, M.A.S. Nomogram-Based Chronic Kidney Disease Prediction Model for Type 1 diabetes mellitus patients using routine pathological data. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.E.H.; Rahman, T.; Khandakar, A.; Al-Madeed, S.; Zughaier, S.M.; Doi, S.A.R.; Hassen, H.; Islam, M.T. An Early Warning Tool for Predicting Mortality Risk of COVID-19 Patients Using Machine Learning. Cogn. Comput. 2024, 16, 1778–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.G.; Park, S.; Kim, H.; Yeom, J.S. Development and Validation of a Risk-Prediction Nomogram for Chronic Low Back Pain using a National Health Examination Survey: A Cross-Sectional study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayana, Y.V.; Chhapola, V.; Tiwari, S.; Debnath, E.; Aggarwal, M.; Prakash, O. Diagnosis of bacterial infection in children with relapse of nephrotic syndrome: A personalized decision-analytic nomogram and decision curve analysis. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2023, 38, 2689–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Almeida, M.J.; Camandaroba, M.P.G.; Nassar, A.P., Jr.; De Jesus, V.H.F. Short-term survival of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer admitted to intensive care unit: A retrospective cohort study. Ecancermedicalscience 2022, 16, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homocianu, D. Exploring the Predictors of Co-Nationals’ Preference over Immigrants in Accessing Jobs—Evidence from World Values Survey. Mathematics 2023, 11, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homocianu, D. Life Satisfaction: Insights from the World Values Survey. Societies 2024, 14, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jann, B. Tabulation of multiple responses. Stata J. Promot. Commun. Stat. Stata 2005, 5, 92–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.K. Triangulation 2.0. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2012, 6, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayyad, U.M.; Piatetsky-Shapiro, G.; Smyth, P. From data mining to knowledge discovery in databases. AI Mag. 1996, 17, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeioplastis, A.; Aliprantis, J.; Konstantakis, M.; Tsimpiris, A. Predicting Student Performance and Enhancing Learning Outcomes: A Data-Driven approach using educational data mining techniques. Computers 2025, 14, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.; Abdullah, A.; Udzir, N.I.; Kasmiran, K.A. A systematic review of machine learning and deep learning techniques for anomaly detection in data mining. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2025, 47, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathison, S. Why Triangulate? Educ. Res. 1988, 17, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, D.; Zou, J. How much does your data exploration overfit? Controlling bias via information usage. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2019, 66, 302–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S. A critical reflection of generalization in mixed methods research. Eval. Rev. 2025, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, G.; Magnus, J.R. Bayesian model averaging and weighted-average least squares: Equivariance, stability, and numerical issues. Stata J. Promot. Commun. Stat. Stata 2011, 11, 518–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurkiewicz, P.; Kadziołka, B.; Kantor, M.; Domżał, J.; Wójcik, R. Machine Learning-Based Elephant Flow Classification on the First Packet. IEEE J. Mag. 2024, 12, 105744–105760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitriyani, N.L.; Syafrudin, M.; Chamidah, N.; Rifada, M.; Susilo, H.; Aydin, D.; Qolbiyani, S.L.; Lee, S.W. A novel approach utilizing bagging, histogram gradient boosting, and advanced feature selection for predicting the onset of cardiovascular diseases. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshewey, A.M.; Shams, M.Y.; Tawfeek, S.M.; Alharbi, A.H.; Ibrahim, A.; Abdelhamid, A.A.; Eid, M.M.; Khodadadi, N.; Abualigah, L.; Khafaga, D.S.; et al. Optimizing HCV disease Prediction in Egypt: The HYOPTGB Framework. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerrigan, D.; Barr, B.; Bertini, E. PDPILoT: Exploring partial dependence plots through ranking, filtering, and clustering. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2025, 31, 7377–7390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merabet, K.; Di Nunno, F.; Granata, F.; Kim, S.; Adnan, R.M.; Heddam, S.; Kisi, O.; Zounemat-Kermani, M. Predicting water quality variables using gradient boosting machine: Global versus local explainability using SHapley Additive Explanations (SHAP). Earth Sci. Inform. 2025, 18, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An analysis of variance test for normality (Complete samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monter-Pozos, A.; González-Estrada, E. On testing the skew normal distribution by using Shapiro–Wilk test. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2024, 440, 115649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cribari-Neto, F.; Da Glória, A.; Lima, M. New heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors for the linear regression model. Braz. J. Probab. Stat. 2014, 28, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Coya, E.; Perron, P. Estimation in the presence of heteroskedasticity of unknown form: A Lasso-based approach. J. Econom. Methods 2023, 13, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.G.; Lee, K.E. A linearity test statistic in a simple linear regression. J. Korean Data Inf. Sci. Soc. 2014, 25, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]