Abstract

The permeability index (PI) is a key comprehensive indicator that reflects the smoothness of internal gas flow in pig iron production via blast furnace. An accurate prediction for it is essential for forecasting abnormal furnace conditions and preventing potential faults. However, developing an early prediction model for PI has been neglected in existing research, and it faces massive challenges due to the strong nonlinearity, undesirable nonstationarity, and significant multiscale time delays inherent in the blast furnace data. To bridge this gap, a new modeling paradigm for PI is proposed to explore the inherent time delay characteristics among multiple variables. First, the data are progressively decomposed into multiple components using wavelet decomposition and spike separation. Then, a novel delay extraction method based on wavelet coherence analysis is developed to obtain accurate multiscale time delay knowledge. Furthermore, the integration of Orthonormal Subspace Analysis (OSA) and wavelet neural network (WNN) achieves comprehensive modeling across time and frequency domains, incorporating global and local features. A Gauss–Markov-based fusion framework is also utilized to reduce the output error variance, ultimately enabling the early prediction of PI. Mechanism analysis and a practical case study on blast furnace production verify the effectiveness of the proposed target-oriented prediction framework.

1. Introduction

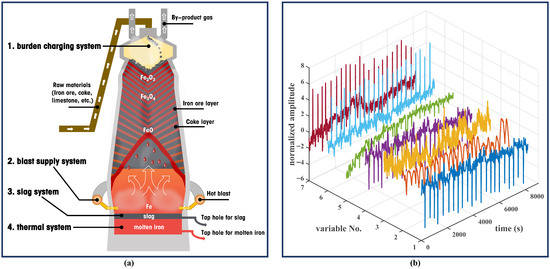

Blast furnace production (BFP), which produces molten pig iron, is one of the most critical links in the entire steel manufacturing system, whose energy consumption accounts for more than 70% of the steel industry [1,2,3]. Uninterrupted heat transfer, momentum transfer, mass transfer, and various chemical reactions drive the blast furnace into a complicated system which has so far remained elusive in identification missions. Permeability index (PI) is an important operation parameter of BFP, reflecting whether the internal airflow of the blast furnace is smooth [4] and significantly impacting subsequent slag formation and desulfurization processes. This indicator is governed by a complex interplay between raw material properties and key operational parameters. The size, strength, and high-temperature behavior of the ferrous burden (sinter/pellets) and coke directly determine the voidage and resistance of the packed bed, forming the physical foundation for gas flow. Furthermore, the moisture content in raw materials can increase particle adhesion, alter burden distribution, and consume significant energy during vaporization, all adversely affecting permeability. In addition, the endothermic decomposition of flux not only produces fine particles but also consumes energy, thereby affecting thermal equilibrium. Simultaneously, operation variables such as the blast volume, temperature, and oxygen enrichment rate critically influence the gas flow rate, combustion zone dynamics, and the shape of the cohesive zone, thereby altering permeability. If the operating systems (including burden charging system, blast supply system, thermal system, and slag system as shown in Figure 1a) of BFP are selected unreasonably, faults are easy to occur inside blast furnaces, causing abnormal values of PI [5,6,7]. However, due to the strong nonlinearity and nonstationarity of the blast furnace process caused by the aforementioned factors, accurately predicting PI in advance remains challenging. Many existing studies have not fully addressed these intertwined challenges, especially the inherent time delay characteristics between variables, which inspired us to conduct this research.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the blast furnace production (BFP) and its nonstationary data characteristics. (a) The basic operating systems of BFP, including the burden charging, blast supply, thermal, and slag systems. (b) Time-series profiles of normalized process variables, including (1) total pressure drop, (2) hot blast temperature, (3) top temperature, (4) hot blast pressure, (5) oxygen enrichment rate, (6) permeability index, and (7) cold blast flow rate.

The variation process of the PI has the following main characteristics:

- Multiple Time Scales: Various parameters of BFP belong to different operating systems, so they have different time scales of influence on PI [8]. The burden charging operation on the upper part of blast furnace changes the PI primarily by affecting the burden distribution, which requires a long transition period of about 6–8 h. The oxygen enrichment rate changes the height of the soft melting zone and the size of the combustion zone by influencing the internal temperature distribution of the blast furnace, thereby affecting the PI. Since it mainly affects the lower burden of the blast furnace, the influence time scale is 15–30 min. The blast supply system directly affects the distribution of gas flow and pressure, thus completely altering PI in just a few minutes [9].

- Nonstationarity: As illustrated in Figure 1b, due to the periodic equipment switching of the heated air subsystem, there occur some upward or downward spikes in the data, resulting in the data’s nonstationarity [10]. Such nonstationarity will cause a modal aliasing phenomenon when using time series decomposition methods for sequence decomposition, causing “data contaminated”. A detailed introduction to this section will be provided in Section 3.1.

- Nonlinearity: Extremely complicated physical and chemical processes in BFP give temporal variables complex nonlinearity characteristics. This unknown-structured nonlinear relationship will pose challenges for modeling. The nonlinear relationship of PI is expressed as follows in Equation (1):where f represents the nonlinear relationship between PI and other parameters, X represents observation parameters related to PI, is the nonlinear order of the parameter corresponding to the subscript, and the subscript n is the total number of these parameters.

Aiming at such a modeling problem, mechanism-based and data-based methods are the two prevalent approaches for studying industrial processes [11]. There are two main types of mechanism-based methods: fundamental analysis and computational modeling. The former qualitatively or semi-quantitatively analyzes the research objectives based on theories of heat transfer, mass transfer and so on, as well as the expert knowledge of blast furnace [8]. The latter simulates the internal state of blast furnace using numerical calculation methods such as computational fluid dynamics (CFD) [12,13] and discrete element method (DEM) [14,15], based on various physical and chemical laws, to obtain the changes of research targets. However, these mechanism-based methods have certain limitations. Fundamental analysis methods carry less credibility in tasks expecting specific numerical results, while computational modeling methods demand extensive time and substantial computational resources for modeling and result calculation, making mechanism-based methods challenging to perform the task of predicting PI.

Data-based methods can effectively handle the nonlinear relationships between industrial variables and uncover the spatiotemporal characteristics within the data to achieve the goal of accurately modeling the target variables [16]. So in recent years, most of the literature has achieved the goal of PI prediction through the application of different intelligent algorithms. Dong et al. performed multi-layer wavelet decomposition on PI to analyze the multiscale characteristic, and combined it with relevant operation parameters to establish the model using the least square support vector machines (LS-SVMs) method for each layer of wavelet coefficients [17]. Su et al. proposed a model for forecasting the future value of PI based on multi-layer extreme learning machine (ML-ELM) and wavelet transform. They solved the high multicollinearity problem of the last hidden layer output of ML-ELM through the principal component analysis (PCA) method, enhancing the generalization performance and stability of the model [18]. Tan et al. conducted a coupling mechanism analysis between PI and airflow, as well as Spearman correlation analysis and maximum information coefficient (MIC) analysis to select key parameters, and ultimately established an intelligent prediction model for blast furnace PI based on the wavelet neural network (WNN) [19]. Liu et al. decomposed the PI according to the difference of frequency bands based on variational mode decomposition (VMD) to obtain multiple sub-modes. For each sub-mode, they constructed a back propagation neural network (BPNN) model optimized by particle swarm optimization (PSO), improving the prediction accuracy of the model [20]. However, research on the PI of blast furnaces is still scarce. Existing studies mostly lack the ability to perform multi-step ahead prediction in advance, and ignore the intrinsic time delay characteristics between different variables and the data nonstationarity caused by the switching of the hot blast stove.

To address the above issues, we propose a PI prediction method based on multiscale time delay characteristic analysis that is guided by the mechanistic understanding of the BFP. Firstly, the nonstationarity characteristics of data caused by the spikes are eliminated through separation from the sequences. Secondly, the multiscale delay characteristics are dug up by the method of wavelet decomposition and wavelet coherence analysis. To our knowledge, this is the first time that wavelet coherence analysis has been applied to time series prediction tasks in the industrial field. Using wavelet coherence analysis, the temporal advance of operational variables relative to PI at different wavelet decomposition scales is obtained. Then, Orthonormal Subspace Analysis (OSA) and WNN are carried out for each wavelet decomposition scale to describe the nonlinearity of variables, and the fusion of submodels is implemented by Gauss–Markov estimation. The input variables are selected to ensure that the key thermodynamic and physicochemical phenomena—such as those governing the soft melting zone, combustion zone, and gas flow distribution—are adequately represented by the operation parameters. The experimental results on actual datasets demonstrate the high accuracy and stability of the proposed model. A detailed comparison between our model and the models proposed in [17,18,19,20] is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of the proposed method with previous hybrid or multiscale models for permeability index prediction.

The main contributions of this article lie in the following three aspects:

- To address the challenge of traditional correlation methods in extracting delays under complex noise conditions in blast furnaces, this article proposes a novel delay extraction method based on wavelet coherence analysis from a multi-resolution perspective and explores reliable multiscale delay knowledge of PI for the first time.

- To comprehensively address data nonstationarity and nonlinearity, this paper proposes a fusion prediction method based on OSA and WNN, which extracts the spatial characteristics between variables from different perspectives in both time and frequency domains, as well as global and local scales, thereby expanding the representation capability of PI.

- To achieve accurate early prediction performance of PI, a practical advance prediction framework is built by fusing extracted delay information and integrating spatiotemporal dimensions through the Gauss–Markov estimation method. We conduct experiments on the proposed method and other traditional methods using actual data. Extensive experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method can consistently maintain good predictive performance. With the increase in prediction time interval, the advantages of the proposed method over other methods are more notable.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the proposed time delay extraction method based on wavelet coherence analysis. The modeling framework of our proposed prediction method is described in Section 3. Then, Section 4 demonstrates the effectiveness of our method through actual BFP cases. Finally, Section 5 provides a summary of the content of this article.

2. Multiscale Time Delay Analysis

2.1. Time Series Multiscale Decomposition

Wavelet transform is a local transformation of time and frequency. Through the scaling and translation of wavelet, wavelet transform achieves the truncation transformation of variable length time windows, which can effectively perform local location and extract information from the signal [21]. Meanwhile, as a time series decomposition method, the multi-resolution analysis ability of wavelet transform endows it with the ability to handle nonstationary time series. By dividing nonstationary time series into sub-sequences with different time distribution characteristics, the nonstationary reduction of each sub-sequence makes it easier to handle, thereby reducing the overall processing difficulty [22].

Assuming signal . Let , make its integer translation satisfy

where represents linear spanning, is called the scaling function, and is called the approximation space with unit scale. When the scale is changed, there are

Thus, given as the orthonormal basis of space , we can obtain constituting the orthonormal basis of space , where . Subspace is called the approximation space of scale .

If can form a multi-resolution analysis (MRA), we can define

Equation (4) means that any element in can be represented as the sum of two mutually orthogonal elements, one belonging to and the other belonging to . Generally, , and is the orthogonal complement of in . Subspace is called the detailed space of scale , where represents the characteristic period of the fluctuations captured in this subspace. Let . Similar to , we require to be the orthonormal basis of subspace . is called the mother wavelet function. Then we have

And constitutes the orthonormal basis of space .

Now can be expressed as the sum of its projection components on and using MRA:

where and are the projections of in subspace and , given by Equations (7) and (8), respectively:

Here is called the approximation of signal , and is the missing detail of approximated by . and are called the approximation coefficient of and detailed coefficient of , respectively.

Similarly, as we can divide it in subspace and :

where

Therefore, we can continuously decompose the approximation components at different scales until the desired result is achieved. Ultimately, the reconstruction of the signal can be expressed as

where J represents the total number of decomposition levels in wavelet decomposition. The detail of each decomposition layer represents the fluctuation patterns at the corresponding time scale. As the number of decomposition layers increases, the fluctuation frequency gradually decreases. And the approximation is the most gentle part of the change, representing the overall trend of the signal.

Wavelet decomposition and EMD-like methods are commonly used and effective multiscale time series decomposition methods [23]. Compared to classical decomposition, seasonal and trend decomposition using Loess (STL), and other methods that divide data series into trend, periodic, and random terms, while wavelet decomposition and EMD-like methods can decompose data into more sub-sequences with more diverse differences in period and frequency, which is convenient to excavate the time delay information more accurately. We utilize wavelet decomposition instead of EMD-like methods for multiscale decomposition for the following reasons:

- (1)

- Using wavelet transform to decompose time series can ensure that the period of the decomposed sequences at the same decomposition level is consistent, meaning that they have data fragments of the same length, reach the same frequency physically, and can naturally cooperate with wavelet coherence analysis to obtain the internal time delay under the corresponding scale. However, EMD and the methods derived from EMD cannot guarantee the same number of intrinsic mode functions (IMFs) decomposed from different variables, nor the consistent scale and frequency of IMFs at the same level of different variables, which will change over different local characteristics of the data. Therefore, it is difficult to extract more detailed intrinsic latency information between data when using EMD-like methods.

- (2)

- When different variables are decomposed using EMD, because of the data fluctuations, the number of IMFs obtained each time and the information contained in each IMF will change with the moving of the sliding window, thus generating additional dynamic information. The wavelet transform, however, uses the same type of wavelet for all the data in one decomposition operation. Therefore, all the changes of the information obtained by decomposition originate from the data itself, and the wavelet transform introduces no additional information.

- (3)

- In the process of adaptive signal decomposition, EMD-like methods need to perform cubic spline interpolation on the extreme value to obtain the upper and lower envelopes of the signal. Since the extreme points at both ends of the data sequence cannot be clearly identified and the conditions required for spline interpolation cannot be satisfied, the envelope line fitted will have a large swing at the endpoints that exceed the signal itself. This untrue swing will gradually spread to the signal center with the increase in decomposition level, resulting in serious distortion of the decomposition results, which is the so-called end effect. The use of wavelet decomposition can avoid the occurrence of this situation.

2.2. Delay Extraction: Wavelet Coherence Analysis

Industrial time series are usually nonstationary, which means that their frequency information changes over time. For these time series, it is important to perform correlation or coherence analysis in the time–frequency plane. Wavelet coherence analysis was proposed by Torrence and Compo [24], aiming to reveal the relationships between different time series in the time–frequency space. Wavelet coherence analysis can detect common temporal local oscillations in nonstationary signals. Additionally, the relative time delay between two series can be identified using the phase of wavelet cross spectrum if one is regarded to have an impact on the other. The cross wavelet transform of time series and is defined as

where and denote the wavelet transformation coefficient of and , respectively. The cross wavelet transform reveals the common power and relative phase of two time series in time–frequency space. Further, in order to capture the coherence between two series at low common power, wavelet coherence is defined as follows:

where S is a smoothing operator in both time and scale. Grinsted et al. [25] rewrite the smoothing operator as

where represents smoothing operation along wavelet scale axis and is smoothing in time. Also, an appropriate smoothing operator is given for the Morlet wavelet:

where and are normalization constants and is the rectangle function.

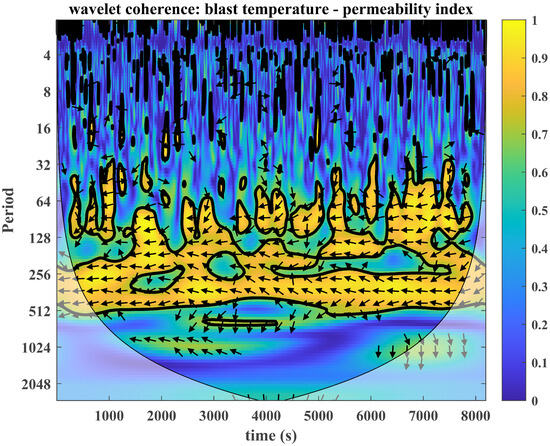

Figure 2 is a wavelet coherence diagram of blast temperature and PI, showing the inner relationship between the two series. The significance level of the area within the black outline is less than 0.05, which is a credible indication of causality. The shade of the colors in the diagram represents the magnitude of wavelet coherence. The closer it is to yellow, the higher the coherence of the time–frequency region, while the closer it is to blue, the lower the coherence. The arrow in the area with higher coherence indicates the phase difference between the two sequences. If the arrow points horizontally to the right, the two sequences are in the same phase; that is, there is no time delay. If the arrow points horizontally left, the two sequences are negatively correlated. If the arrow has an upward angle, it means that the first sequence is ahead. If the arrow has a downward angle, the second sequence is leading. Through the phase angle, the corresponding time delay can be calculated. From Figure 2 we can see that at all times within the period from 256 to 512, the blast temperature and PI exhibit high coherence, and the arrows are mostly horizontally to the left, indicating that the two series show anti-phase behavior at the corresponding period.

Figure 2.

Wavelet coherence between blast temperature and permeability index series.

2.3. Determination of Delay Knowledge

According to the wavelet coherence analysis in Section 2.2, the coherence values and phase difference of the operating variables and PI at different decomposition scales and different time can be obtained. What we should do next is to convert them into specific time delays at certain scales, which can be used for variable alignment operation before the prediction task. We propose a method to achieve this goal. First, it is necessary to set a threshold to filter out the positions where the coherence is less than . Then, the average phase difference at a certain scale is obtained by weighted averaging the phase differences of all reserved positions at this scale according to coherence values, that is,

Finally, the phase difference is converted into the corresponding time delay:

In addition, for the needs of practical industrial application, it is necessary to set a minimum advance time step , which means we need to make predictions of steps in advance. To meet the requirements, the time delay is replaced with if , and retained in other cases, reaching the final time delay value.

3. Prediction Methodology

3.1. Spike Separation

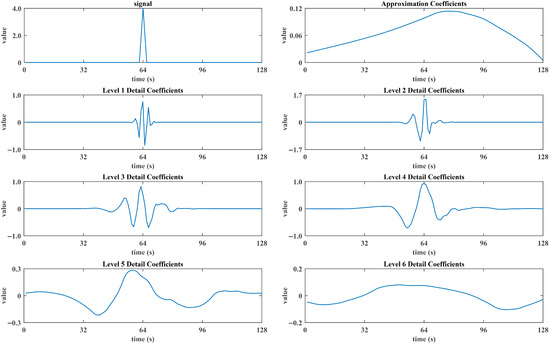

An arbitrary spike signal similar to the spike of PI data caused by periodic equipment switching of the heated air subsystem is provided, with a total length of 128 and a non-zero region ranging from 54 to 76. The original signal and the results of six-layer wavelet decomposition are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Wavelet analysis of spike signal.

When applying Equation (11) to perform wavelet transforms at each level, selecting some specific values of the displacement factor k will result in the non-zero region of the wavelet function exactly covering a part of zero region of the original signal. At this point, performing inner product operation will gain a non-zero value, ultimately causing the transformed signal to diffuse outward relative to the original signal. Figure 3 shows the corresponding results.

The original PI signal can be decomposed into a sum of a relatively stationary signal and a spike signal:

According to Equation (8), the detail coefficients of the original signal can be correspondingly represented as the sum of the detail coefficients of two component signals:

Assuming that the amplitude of the spike fluctuation is about times the amplitude of the fluctuation of ( is an amplification factor), which is the result of removing the mean of , then we can derive

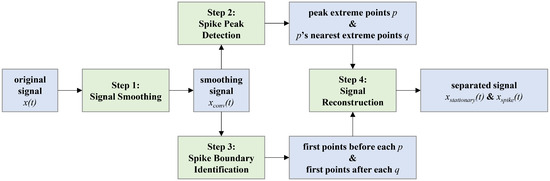

For the PI signal of the actual process, the value of is generally around 10, so the shape and amplitude of the wavelet decomposition result of the original signal are closer to the wavelet decomposition result of the spike signal, and the relatively stationary sequence is covered up. Compared with the information at the spike, the information from the relatively stable sequence is worthy of more attention, so we need to separate the spikes. The process of spike separation is shown in Figure 4, and the specific steps are as follows:

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of spike separation process.

Step 1: Convolve the original signal to obtain the convolutional sequences with a Gaussian function . The value of should be determined carefully. If is too small, the smoothing effect is poor, while large will lead to waveform distortion and phase shift. After experimental adjustment, is selected.

Step 2: Perform second-order difference on and set an appropriate threshold to filter out the peak extreme points p. Then, perform first-order difference on and set an appropriate interval to obtain the nearest extreme point q following each point p.

Step 3: Use the first-order difference of as the search sequence. Set another threshold to locate the first point before point p which is less than as the starting point of the peak, and the first point after point q which is less than as the ending point of the peak.

Step 4: The sequence obtained by connecting the starting and ending points of the peak with smooth curves that can preserve the original peaks’ changing trend and greatly reduce the amplitude is the stationary sequence of the original signal, and the remaining part is the separated peaks, thereby achieving the goal of peak separation.

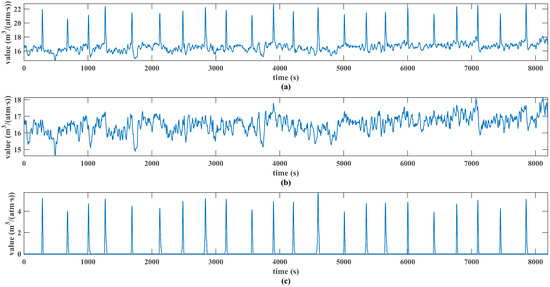

Figure 5 shows the comparison of PI series before and after spike separation. It can be seen that in the original series containing 22 hot blast stove switches, the operation of spike separation can effectively remove all peaks and maintain the stable changing trend of the sequence except for the peaks. The separated signal only contains the peaks caused by the switching of hot blast stove without any additional information.

Figure 5.

Permeability index (a) before spike separation, (b) after spike separation, and (c) separated peak signal.

3.2. Fusion Prediction Model

In this section, two algorithms, OSA and WNN, are applied and integrated through the Gauss–Markov estimation method to perform the prediction tasks. OSA is used to analyze the global time-domain information of data, while WNN can capture the local frequency-domain features more intensively. This fusion model can more comprehensively describe the nonlinearity and nonstationarity characteristics of PI.

3.2.1. Global Time-Domain: Orthonormal Subspace Analysis

Orthonormal Subspace Analysis (OSA) is a new statistical learning algorithm first used in fault monitoring tasks [26]. It proposes a subspace orthogonalization method that decomposes process data and quality data into three orthonormal subspaces (as shown in Equation (23)), overcoming the defects of canonical correlation analysis (CCA) and partial least squares (PLS) in information leakage, model identification, and component selection. Now we will re-derive OSA to enable its application in prediction tasks:

where is the common latent variable shared by both and , that is , and and are the transformation matrices. and are the residual matrices of and such that they do not contain any information of . Therefore, and can be divided into the following three subspaces: (1) the common component subspace, i.e., and , (2) the residual subspace of , i.e., , and (3) the residual subspace of , i.e., . It can be proven that these three subspaces are mutually orthogonal. Therefore, and can be written as follows:

where represents the transformation matrix from to , and represents the transformation matrix from to . Since is orthogonal to and , and is orthogonal to and , we can obtain

Then all the required transformation matrices can be derived as follows:

is necessary for the situation where new quality data may not be available. Then principal components are extracted using Equation (27) as the observation variables in may be highly linearly correlated:

where denotes the score matrix, represents the loading matrix, and is the residual matrix. Accordingly, the transformation matrices from to and from to can be derived as follows:

Subsequently, the quality data can be predicted with new process data and Equation (29):

3.2.2. Local Frequency-Domain: Wavelet Neural Network

The wavelet neural network (WNN) is a variant of BPNN [27]. It replaces the traditional activation functions used by hidden layer neurons in BPNN with the Morlet wavelet function as shown in the following equation:

The narrow bandwidth of the Morlet wavelet function in frequency domain provides it with high-frequency resolution, endowing WNN with excellent capability to process high-frequency local nonstationary signals. Similar to Equation (5), the output value of hidden layer neurons is correspondingly calculated as

where is the output value of the nth node in the hidden layer, denotes weights connecting the input layer and hidden layer, is the output value of the mth node in the input layer, and and are the scale factor and displacement factor of the nth node in the hidden layer, respectively.

WNN inherits the advantages of wavelet transform and BPNN. Through introducing scale factor and displacement factor , which are adjusted by adopting the same error back propagation algorithm as neural network weights, WNN can perform multiscale analysis on signals using time windows of different widths and positions, thereby highlighting the details of the problem to be processed, effectively extracting local information of the signals, and avoiding nonlinear optimization problems such as local optima [28].

3.2.3. Model Fusion: Gauss–Markov Estimation

After obtaining the prediction results of OSA and WNN models at different scales, fusing them to obtain the final model output is necessary. The traditional method assigns the same weight to different submodels, which can lead to error accumulation. The improvement in ultimate prediction accuracy is achieved through model fusion using Gauss–Markov estimation. Gauss–Markov estimation is essentially a special form of weighted least squares method [29]. By fusing the error variances of different models, the error variance of the final output result is brought smaller than that of each single submodel.

Assume that there are C prediction submodels. The estimated output of the ith submodel is . The corresponding prediction error and variance are and , respectively. And the actual value is y. Hence, the relationship between and y can be expressed as . Gauss–Markov theorem assumes that all errors satisfy the conditions of independence from each other and zero mean. For minimizing the error variance of the estimated final output , the weighted variance estimation index is constructed as

where , is a vector with all elements equal to 1, and . The estimated value can be calculated as

and the corresponding error variance can be derived as

Equation (34) shows that Gauss–Markov estimation can reduce the error variance of the final output results in the process of model integration and thus improve the prediction performance of the overall model.

3.3. The Proposed Prediction Framework

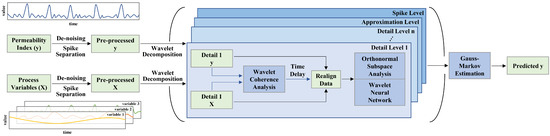

The basic architecture of our proposed PI prediction model is shown in Figure 6. The modeling process is as follows:

Figure 6.

Basic architecture of the proposed method.

Step 1: Determine the input and output variables of the model based on the operational mechanism of BFP.

Step 2: Perform de-noising and spike separation on all variables to obtain their respective stationary and peak parts.

Step 3: Select the appropriate number of wavelet decomposition layers n, then apply wavelet decomposition to the stationary part of each variable to get n detail components and one approximation component.

Step 4: At each decomposition level, extract the decomposition sequences of all variables belonging to that decomposition level, align these sequences based on the time delay received from wavelet coherence analysis. Then send the aligned data into OSA and WNN to conduct model training and fusion by Gauss–Markov estimation. Perform the same operation on the peak parts separated in Step 2.

Step 5: Utilize the well-trained model to conduct prediction tasks at different scales with new input data and sum up all the outputs to gain the final predicted value of PI.

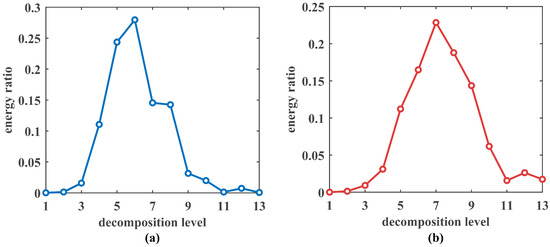

The selection of wavelet decomposition levels is crucial in this model. Due to the fact that signal can be decomposed into the form of Equation (12), considering the orthonormality of wavelets and , according to Parseval’s theorem, it can be obtained that

Therefore, represents the energy contribution of changes on scale to . at different decomposition levels are calculated to obtain their respective energy ratios as shown in Figure 7. It can be seen that after decomposing to the ninth layer, the energy contribution of corresponding detail coefficients significantly decreases. There is no significance for further decomposition and analysis of them. So the wavelet decomposition layer is selected as 9. Figure 7 also illustrates that after spike separation, the highest energy ratio decreases, and the energy aggregation phenomenon of the detail coefficients of each layer weakens, indicating that this operation effectively separates the impact of the hot blast subsystem switching from the normal operation sequence. In addition, the commonly used Daubechies wavelets are chosen, which have good regularity, compact support, and symmetry.

Figure 7.

Energy ratio of different decomposition level of detail coefficients for (a) original permeability index signal and (b) permeability index signal processed by spike separation.

The selection of other important model parameters, including the number of hidden layer units m in WNN and the wavelet coherence threshold , will be discussed in detail in Section 4.

4. Experimental Studies

This section will discuss the results of implementing our proposed model for PI prediction tasks on field data from actual BFP. We gathered actual operation data of the #2 blast furnace of Liuzhou Steel Group Co., Ltd. in Guangxi Province, China, in March 2021. Based on the operational mechanism analysis of BFP in Section 1, available observation variables with different impact time scales that are most relevant to PI are selected as the input variables of the model, including cold blast flow rate (CBFR), oxygen enrichment rate (OER), blast kinetic energy (BKE), bosh gas index (BGI), total pressure drop (TPD), hot blast pressure (HBP), hot blast temperature (HBT), and top temperature (TT). They belong to different operating systems of the blast furnace, covering impact time scales from seconds to hours. These process data are stored in SQL Server, collected on-site at a frequency of 10 s. PI is the output variable of the model. A total of 8192 data points are used for the simulation experiments, of which 80% are used for training the prediction model and the rest are test data. All variables are de-noised using Daubechies 4 wavelet and normalized before being fed into the model. The detailed information of the observation data is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Detailed information of the collected observation data.

To demonstrate the modeling effectiveness of our method, root mean square error (RMSE), correlation coefficient (r), and determination coefficient () are used as evaluation criteria for model performance. RMSE is used to measure the average deviation between prediction values and actual values. The closer RMSE is to 0, the more accurate the prediction model is. r describes the degree of linear correlation between the prediction values and the actual values, while the reflects the model’s goodness of fit. The closer r and are to 1, the closer the prediction values are to the actual values in general. The calculation formulas for RMSE, r, and are as follows:

4.1. Time Delay Analysis

Table 3 compares the time delays between 8 input variables and PI calculated using our method, Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC), and mutual information (MI) method at different wavelet decomposition levels. Different operating variables act on different parts of the blast furnace and involve different physical or chemical processes, each with its characteristic time scale. Since there are no actual measured values for the time delays, we conduct a qualitative analysis based on practical conditions and expert knowledge to elucidate the physical interpretation of the extracted multiscale time delays.

Table 3.

Time delay between eight input variables and permeability index at different wavelet decomposition levels calculated by three methods.

The smaller numbers in the table (below 50) represent shorter delays of a few minutes. These are mainly related to the blast furnace air supply system and the instantaneous dynamics of the gas. Variables such as CBFR, BKE, BGI, and HBP directly affect the distribution and pressure of the ascending gas. A change in these parameters can almost instantaneously alter the gas flow pattern and pressure drop across the cohesive zone and dry zone, impacting PI within minutes. This is analogous to changing the pressure in a pneumatic pipe, where the effect is nearly immediate.

The larger numbers in the table (above 50) represent longer delays ranging from tens of minutes to hours. These delays correspond to the thermal and chemical processes governing the softening and melting zone. Operational variables like OER and HBT modify the adiabatic flame temperature and the size of combustion zone. This, in turn, alters the shape, thickness, and location of the soft melting zone—the primary resistance to gas flow in the furnace. However, this thermal inertia and the subsequent change in the melting zone’s structure require a longer time to manifest fully in the overall permeability.

With this physical context, the results in Table 3 can be meaningfully interpreted. As a calculated variable, PI should fall behind all variables collected from actual sites in terms of trend and phase. In our method, all delays are positive values, meaning the input variables lead PI, which aligns with physical causality. In contrast, the mixed positive and negative delays from PCC and MI are physically implausible. For different variables, noise dominates the first two wavelet decomposition sequences. The noise of random fluctuations does not have a relative delay, and the same conclusion is reflected in the results obtained by our method. However, PCC and MI exhibit inappropriate large-time delays in the first two wavelet decomposition levels, which contradicts common sense.

Furthermore, our results are consistent with the expected impact scales. Variables related to the gas supply (CBFR, BKE, BGI, TPD, and HBP) show significant delays within ten minutes (e.g., at levels 3–7), while those influencing the thermal state (OER, HBT, and TT) exhibit major delays in the 30 min to 1 h range (e.g., at levels 8–9). This clear separation of influence timescales is absent in the PCC and MI results, which show erratic and counter-intuitive delays (e.g., extremely large values at low decomposition levels dominated by noise). In summary, the multiscale time delays extracted by our proposed method provide a physically meaningful and accurate representation of the diverse dynamic processes inside the blast furnace.

4.2. Prediction Accuracy Analysis

To rigorously assess the performance of our model and validate its superiority over existing approaches, we conduct four sets of experiments using different methods for comprehensive comparison with our model. Table 4 shows the parameter settings of each model and the PI prediction results at different minimum advance time steps . Group A contains several machine learning methods without neural networks, Group B contains several commonly used neural network methods, Group C contains published methods for PI prediction, and Group D is an ablation study of our model. The above results are averaged over 20 experiments.

Table 4.

Prediction results of permeability index from different methods.

To ensure a fair comparison across all benchmark methods, optimal model parameters are determined through a combination of literature-guided initialization and data-driven cross-validation. For traditional machine learning models in Group A, the optimal hyperparameters are determined via 5-fold cross-validation on the training set. For PLS and OSA, the number of latent variables is determined by the 90% Cumulative Percent Variance (CPV) criterion, a standard threshold to retain sufficient process information while avoiding overfitting. For KPLS, a polynomial kernel is adopted, with the order optimized to 2 and the constant term to 2 via 5-fold cross-validation. For LS-SVM, the kernel parameter for the RBF kernel is set to 10, calibrated to minimize the prediction error during cross-validation. For neural network-based models in Group B, a combination of grid search and hold-out validation is employed. The number of hidden units for GRU and LSTM is optimized to 32, and the learning rate is set to 0.001. The network structure for MLP is set to [8, 4] through cross-validation. The parameters for methods from the literature in Group C are set according to their original publications, with any unspecified parameters optimized using a compatible strategy. The final hyperparameter configurations for all models, which yield the best performance on the validation set, are summarized in Table 4.

In the case of , PI is equal to CBFR divided by TPD at the same acquisition time. This calculation process does not exhibit strong nonlinearity. Therefore, linear methods PLS and OSA both demonstrate relatively good prediction performance. Due to the ability to forcibly partition mutually orthogonal output-related components subspaces and residual subspaces, OSA overcomes the problem of information leaking into the residual space, reaching better prediction performance than PLS. Compared with RBF kernel, KPLS with polynomial kernel obtains better performance, indicating the low dimension of PI data in this case, so that using infinite dimensional Gaussian kernels is more prone to overfitting. The slight performance improvement of KPLS compared to PLS also indicates this point. The LS-SVM method also has the problem of overfitting (RMSE = 0.042 for the training set and RMSE = 0.735 for the test set) due to its higher suitability for small sample data and the distribution of our dataset.

Results of neural network methods show better experimental performance. As a single-layer feedforward neural network, introducing kernel functions improves the ability of ELM to handle nonlinearity, but overfitting is prone to occur for weak nonlinear scenarios. By contrast, the simple MLP model obtains better results. Deep learning models GRU and LSTM achieve the best prediction performance since the addition of recurrent cells improves the ability to process long-time series prediction tasks.

For Group C, since the original literature did not consider the situation of hot blast stove switching, our data show stronger nonstationarity than theirs, and their methods cannot perform the best on our dataset. W-LS-SVM [17] has the same overfitting problem as LS-SVM. Even if wavelet decomposition is applied to improve the ability of multiscale analysis, its performance is still very poor. The two improved methods based on the ELM model have similar effects. Compared to w-PCA-ML-ELM [18], adding the ALD criterion and sliding windows for data filtering improves the prediction performance of ALD-KOS-ELMF [30] slightly. Since WNN only changes the activation function compared to ANN, the performance of CM-WNN [19] with a single hidden layer is not as good as MLP with multiple hidden layers. Due to the addition of modal decomposition and optimization to the MLP model, the performance of VMD-PSO-BP [20] is the best in Group C.

For Group D, we compare the effect of our method and the models that remove any one module from the complete model. It can be seen that each module contributes to the effectiveness improvement of the model. Peak separation reduces the nonstationarity of data and enhances the effect of wavelet decomposition, thereby improving prediction performance. OSA and WNN supplement the prediction effect of the model from both linear and nonlinear aspects. The delay analysis module introduces additional intrinsic delay information, improves the interpretability and robustness of the model, and also enhances the prediction performance. However, compared to our models and those with better performance such as GRU, LSTM and OSA, the information contained in the input variables is already rich and complete enough when . In this case, the use of the wavelet decomposition method will actually destroy the original structure and information implied in the data, leading to a decrease in prediction performance.

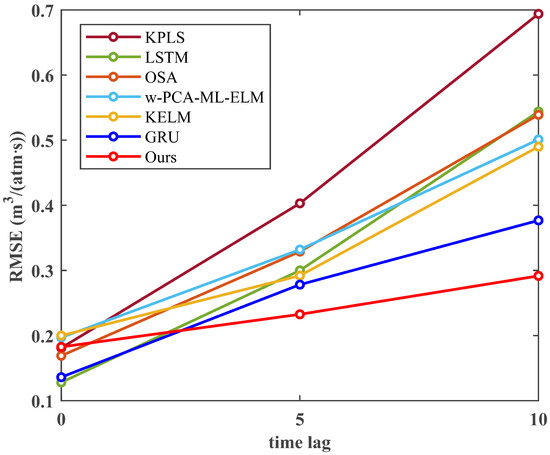

However, the situation changes when . In Table 4, we list the experimental results with and 10. In this case, CBFR, TPD, and PI to be predicted no longer have a clear relationship. Moreover, due to the small impact time scale of the air supply system, once the time delay exists, the correlation between variables will obviously decrease. Therefore, it can be seen that RMSE in the experimental results of Group A, B, and C all significantly rises with the increase in delay. In contrast, GRU has the best effect among them. When changes from 0 to 10, the RMSE only increases by 0.241, and the and r values also maintain a high level. However, when and 10, our method has the best performance in the three indicators of RMSE, , and r, and the increase in RMSE is also the least (only 0.109), which reflects the applicability of our method in scenarios that require multi-step advance prediction. It is observed that the RMSE difference between the with and without delay analysis module gradually increases (from 0.032 to 0.038 and then to 0.072), indicating that the correlation between variables weakens with the increase in , and the inherent delay information of long time scales obtained by using delay analysis module at different decomposition scales could compensate for the decline in correlation and slow down the reduction in prediction effect. Figure 8 compares the variation of RMSE with for different methods. It can be intuitively seen that except for GRU and our method, the slope in the second half of other methods is larger than that in the first half, illustrating that the model effect deteriorates to a greater extent when the time delay is larger. On the contrary, our model shows a nearly straight line with the smallest slope in the graph, meaning that our model maintains good performance under different time delays. When increases, the performance of other models declines significantly because they lack an understanding of the inherent causal time lags between variables. In contrast, our model, by explicitly leveraging multiscale time delay information, can ’anticipate’ changes caused by slow processes (such as cohesive zone variations) earlier. As a result, its prediction performance decays the slowest, which is crucial in industrial scenarios that require long-term early warning.

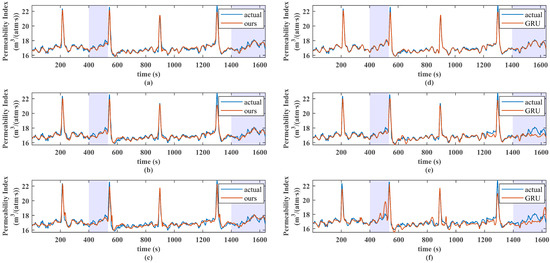

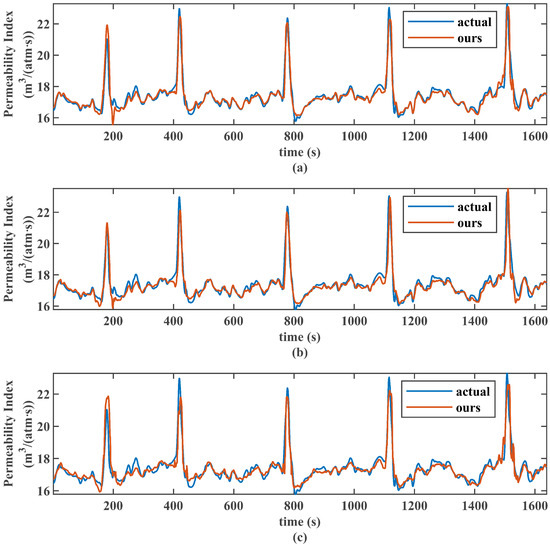

Figure 8.

Evolution of prediction accuracy for multi-step ahead forecasting. The RMSE values for the permeability index of different models are shown as a function of minimum advance time step .

A more in-depth comparison between our method and the GRU method, which has the best overall prediction performance among other methods, is shown in Figure 9. In the stage where the data trend is relatively stable (such as the acquisition time periods of 600–800 and 1000–1200), GRU can show good fitting results at different time delays. However, when the data are not stable enough (such as the region with purple shadows in the figure), there exist significant fluctuations in the actual data, and in the case of large , multi-resolution information is hidden in the data. With GRU without prior knowledge guidance, it is difficult to mine this information, which is susceptible to other irrelevant information, resulting in overfitting and worsening the prediction results. On the contrary, thanks to the multi-resolution analysis and multi-time-scale analysis capabilities, our method can predict the trend of PI changes well at any time delay, even in periods when the process changes are not stationary enough.

Figure 9.

Comparison of prediction details between the proposed method and the GRU model under different . (a–c) show the predictions of our method for 0, 5, and 10, respectively. (d–f) show the corresponding predictions of the GRU model.

A key concern for industrial models is their performance across varying operating conditions. Although developed on data from one blast furnace, our model is rigorously tested against inherent regime shifts on datasets from different time periods. We provide the prediction performance of the proposed model on another production dataset from August 2021, as shown in Figure 10. Our model’s prediction stability shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10 demonstrates its robustness under different operating modes. This robustness stems from our methodology’s core focus on multiscale delay extraction and time–frequency domain modeling, which are universal challenges in blast furnace operation. Therefore, the model exhibits strong potential for transferability to other furnaces, as the methodology is designed to learn the specific dynamics of any given dataset.

Figure 10.

Prediction details of the proposed method under different using data from August 2021. (a–c) show the predictions of our method for 0, 5, and 10, respectively.

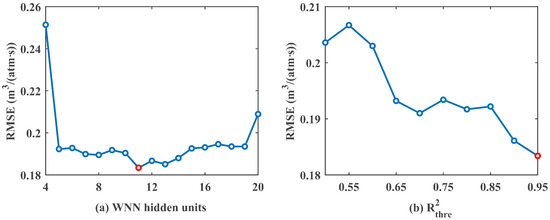

4.3. Model Parameter Selection

We study the prediction performance of our model with different values of the number of hidden layer units m in WNN and the wavelet correlation threshold described in Section 3.3 at , as shown in Figure 11. As m increases, the prediction performance shows a trend of initially decreasing and then increasing, reaching its lowest point at . It is easy to understand that an initial increase in m improves the fitting ability of neural networks, but when m exceeds a certain value, the increase in network complexity results in overfitting the decrease in prediction performance on the test set. Therefore, m is set to 11. With the increase in , the decrease in RMSE goes through three plateau periods (0.5–0.6, 0.65–0.85, and 0.9–0.95), reaching its minimum at . During this process, excess information is constantly filtered, leaving behind information more relevant to PI and more accurate intrinsic time delays. In practical applications, we find that for different , the results are not significantly different when values of 0.9 and 0.95 are selected. Sometimes choosing works better, and sometimes choosing works better. Here, we mainly choose for the experiment.

Figure 11.

Prediction performance of our method at 0 time delay varies with (a) the number of hidden layer units m in wavelet neural network (WNN) and (b) the wavelet coherence threshold .

4.4. Computational Efficiency Analysis

In order to analyze the computational efficiency of our model, we compare both the training time and inference time of models with better prediction performance under Intel(R) Core(TM) i9-10900K CPU and 32G RAM as shown in Table 5. The training time of our model is 30.70 s, which is competitive compared to other complex models. Because our model is based on OSA with WNN and reduces the hidden layer nodes of WNN, even if nine wavelet layers are selected, the computation time of our model is still well controlled. More critically for practical application, the inference time of our model on the test set containing 1638 data points is 35.74 milliseconds. This high prediction speed is a pivotal factor for real-time industrial deployment. Given that the data acquisition frequency in our industrial case is 10 s, our model can complete a prediction in less than 0.36% of the sampling interval. This demonstrates a strong capability for real-time monitoring and provides ample computational headroom for timely operational adjustments.

Table 5.

Training time and inference time of different models.

In contrast, while models like OSA and w-PCA-ML-ELM exhibit lower inference times, their prediction accuracy, especially for multi-step ahead forecasting as demonstrated in Table 4, is significantly inferior to our method. On the other hand, deep learning models such as GRU and LSTM, despite their high accuracy, suffer from excessively high inference times (over 3.8 s), which could become a bottleneck in a continuous real-time monitoring system. Therefore, the proposed framework achieves an excellent balance between prediction accuracy and computational efficiency, making it highly feasible for real-time deployment in industrial environments where both timeliness and precision are important.

5. Conclusions

Advance PI prediction plays an important role in monitoring and adjusting the internal production status of blast furnaces. In this article, a PI prediction model that can explore the inherent time delay characteristics between variables is proposed. Firstly, based on the proposed novel delay extraction approach, the process dynamics between observed variables and PI are focused on extracting time delay information at different time scales for the first time, overcoming the limitation of traditional correlation analysis in noisy environments. Secondly, to handle the data nonstationarity and nonlinearity, OSA is transferred to prediction tasks and integrated with WNN to provide time–frequency multi-resolution feature extraction capability at both global and local scales. Through the collaborative framework based on Gauss–Markov estimation between different modules, the risk of overfitting is reduced, ensuring the reliability and accuracy of the model. Finally, the effectiveness of the proposed model in extracting the time delay characteristics between variables is demonstrated through mechanism analysis and practical blast furnace studies. Compared with traditional machine learning and deep learning methods, the proposed model provides the best advance prediction performance for PI. One limitation of this study is the exclusion of raw material properties, which could introduce prediction deviations during quality fluctuations. Future research will focus on incorporating these data to enhance the comprehensiveness of the model, and continuously optimize training time and prediction performance for zero advance time. This work will also be expanded to other more valuable fields. A key next step is developing an online learning version of the framework to enable adaptive model updating, which is crucial for handling slow process drifts and ensuring long-term practical utility. Furthermore, the proposed methodology, with its core components of multiscale delay extraction and hybrid modeling, demonstrates strong generality. It holds significant potential for being applied to predict other critical blast furnace indices, such as silicon content in hot metal, thereby facilitating a more comprehensive and intelligent operational system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.X. and C.Y.; methodology, Y.X.; software, Y.X.; validation, Y.X. and S.L.; formal analysis, Y.X.; investigation, Y.X. and S.L.; resources, Y.X. and C.Y.; data curation, Y.X. and S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.X.; writing—review and editing, C.Y. and S.L.; visualization, Y.X.; supervision, C.Y. and S.L.; project administration, C.Y.; funding acquisition, C.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Authors gratefully acknowledge the support by Pioneer Research and Development Program of Zhejiang (No. 2025C01021), Zhejiang Province Postdoctoral Research Project Selection Fund (No. ZJ2025061), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62394341) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 226202400182).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, X.; Kano, M.; Matsuzaki, S. A comparative study of deep and shallow predictive techniques for hot metal temperature prediction in blast furnace ironmaking. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2019, 130, 106575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Li, W.; Wang, H.; Li, M.; Chai, T. Robust online sequential RVFLNs for data modeling of dynamic time-varying systems with application of an ironmaking blast furnace. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2019, 50, 4783–4795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, C.; Li, Y.; Xie, S. A context-aware enhanced GRU network with feature-temporal attention for prediction of silicon content in hot metal. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021, 18, 6631–6641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Wang, Z.; Li, K.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S. Machine Learning Models for Predicting and Controlling the Pressure Difference of Blast Furnace. JOM 2023, 75, 4550–4561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, A.; Onorin, O.; Spirin, N.; Polinov, A. MMK blast furnace operation with a high proportion of pellets in a charge. Part 1. Metallurgist 2016, 60, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K.; Agrawal, A.; Reddy, A.; Ramna, R. Factsage studies to identify the optimum slag regime for blast furnace operation. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2021, 74, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonkikh, D.; Karikov, S.; Tarakanov, A.; Koval’chik, R.; Kostomarov, A. Improving the charging and blast regimes on blast furnaces at the Azovstal metallurgical combine. Metallurgist 2014, 57, 797–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; An, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, Q. Multi-Time Scale Analysis of The Influence of Blast Furnace Operations on Permeability Index. In Proceedings of the 2022 41st Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Hefei, China, 25–27 July 2022; pp. 2574–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Yang, C. Pretrained Language–Knowledge Graph Model Benefits Both Knowledge Graph Completion and Industrial Tasks: Taking the Blast Furnace Ironmaking Process as an Example. Electronics 2024, 13, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Shang, J.; Zhang, J.; Yang, C. Nonstationary process monitoring for blast furnaces based on consistent trend feature analysis. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2021, 30, 1257–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhale, P.B.; Viswanathan, N.N.; Saxén, H. Numerical modelling of blast furnace–Evolution and recent trends. Miner. Process Extr. Metall. 2020, 129, 166–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Tang, G.; Wang, J.; Fu, D.; Okosun, T.; Silaen, A.; Wu, B. Comprehensive numerical modeling of the blast furnace ironmaking process. JOM 2016, 68, 1353–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhu, R.; Zhou, P.; Song, Y.p.; Zhou, C.Q. Prediction of the cohesive zone in a blast furnace by integrating CFD and SVM modelling. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2021, 48, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeplal, R.; Pang, Y.; Adema, A.; van der Stel, J.; Schott, D. Modelling of phenomena affecting blast furnace burden permeability using the Discrete Element Method (DEM)—A review. Powder Technol. 2023, 415, 118161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, E.R.; Pozzetti, G.; Peters, B. Application of a dual-grid multiscale CFD-DEM coupling method to model the raceway dynamics in packed bed reactors. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2019, 205, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhang, X.; Kano, M.; Deng, L.; Yang, C.; Song, Z. Data-driven soft sensors in blast furnace ironmaking: A survey. Front. Inform. Technol. Elect. Eng. 2023, 24, 327–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Bai, C.; Shi, H.; Dong, J. Research on intellectual prediction for permeability index of blast furnace. In Proceedings of the 2009 WRI Global Congress on Intelligent Systems, Xiamen, China, 19–21 May 2009; pp. 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Zhang, S.; Yin, Y.; Xiao, W. Prediction model of permeability index for blast furnace based on the improved multi-layer extreme learning machine and wavelet transform. J. Frankl. Inst. 2018, 355, 1663–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.; Li, Z.; Han, Y.; Qi, X.; Wang, W. Research and Application of Coupled Mechanism and Data-Driven Prediction of Blast Furnace Permeability Index. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, R.; Chen, S. Prediction for permeability index of blast furnace based on VMD–PSO–BP model. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2024, 31, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, A.P.M.; Côco, K.F.; Gomes, F.S.V.; Salles, J.L.F. Forecasting model of silicon content in molten iron using wavelet decomposition and artificial neural networks. Metals 2021, 11, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Zhang, T.; Lim, E.; Lopez-Benitez, M.; Ma, F.; Yu, L. A review of wavelet analysis and its applications: Challenges and opportunities. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 58869–58903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tan, H.; Wang, Z. Interference response prediction of receiver based on wavelet transform and a temporal convolution network. Electronics 2023, 13, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrence, C.; Compo, G.P. A practical guide to wavelet analysis. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1998, 79, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinsted, A.; Moore, J.C.; Jevrejeva, S. Application of the cross wavelet transform and wavelet coherence to geophysical time series. Nonlinear Process Geophys. 2004, 11, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Z.; Wang, Y.; Si, Y.; Lu, S. A novel multivariate statistical process monitoring algorithm: Orthonormal subspace analysis. Automatica 2022, 138, 110148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X. A comparative research on wavelet neural networks. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Neural Information Processing, Singapore, 18–22 November 2002; pp. 1699–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, A.; Yadav, Y. Wavelet-Based Fusion for Image Steganography Using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Electronics 2025, 14, 2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonocore, A.; Caputo, L.; Nobile, A.G.; Pirozzi, E. Gauss–Markov processes in the presence of a reflecting boundary and applications in neuronal models. Appl. Math. Comput. 2014, 232, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-X.; Zhang, S.; Sun, S.-L.; Yin, Y.-X. A novel permeability index prediction method for blast furnace based on the improved extreme learning machine. In Proceedings of the 2022 37th Youth Academic Annual Conference of Chinese Association of Automation (YAC), Beijing, China, 19–20 November 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).