1. Introduction

More Electric Aircraft, as a representative of the new generation of aviation electrical architecture, gradually replaces traditional mechanical transmission methods such as hydraulic and pneumatic systems with electrical energy integration technology, significantly improving the comprehensive utilization efficiency of onboard energy [

1,

2]. In this system, DC–DC power converters undertake the core function of energy conversion, and their operational reliability has a decisive impact on the entire onboard power system [

3].

In actual flight missions, DC–DC converters often face rapidly changing operating conditions. The key components such as internal power semiconductors, capacitors, and inductors are prone to performance degradation under the coupling effect of electrical thermal multi-physical field stress, which in turn affects the overall reliability of the system. Aluminum electrolytic capacitors (AEC) have become key components of DC–DC converters due to their excellent filtering and voltage stabilization performance [

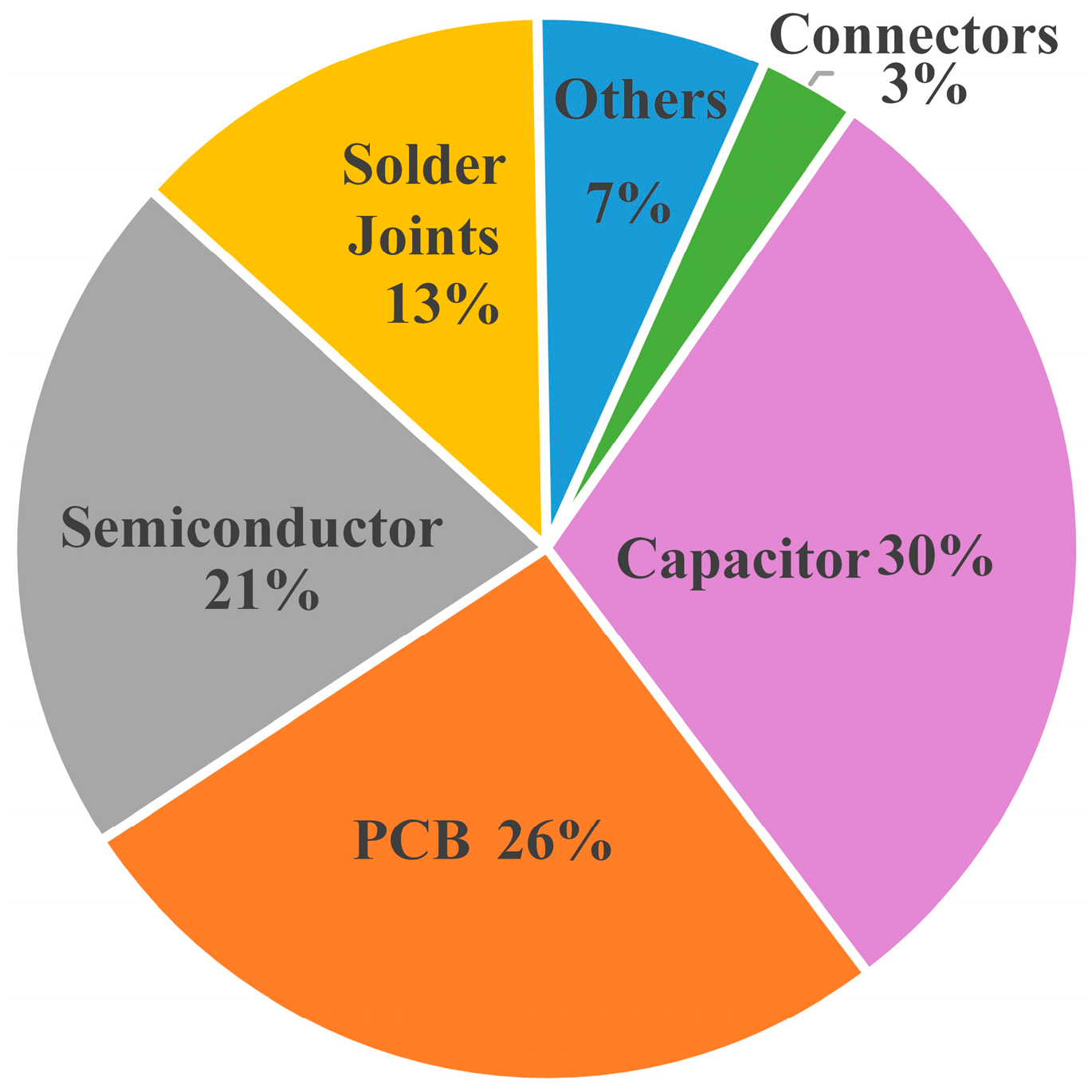

4]. However, as shown in

Figure 1, the fault statistics of the converter indicate that the failure rate of AEC is as high as about 30%, which is considered the weakest link in the converter and is therefore commonly used as a reference indicator to evaluate its overall lifespan [

5].

The capacitance (C) and equivalent series resistance (ESR) are key electrical parameters for evaluating the aging state of capacitors [

6,

7]. It is generally believed that when the capacitance drops to 80% of the initial value or the ESR rises to twice the initial value, the capacitor fails. State monitoring technology is the core means of identifying the aging status of capacitors and achieving fault warning [

8,

9]. According to whether the system operation needs to be interrupted during the monitoring process, existing methods can be mainly divided into two categories: offline monitoring and online monitoring [

10].

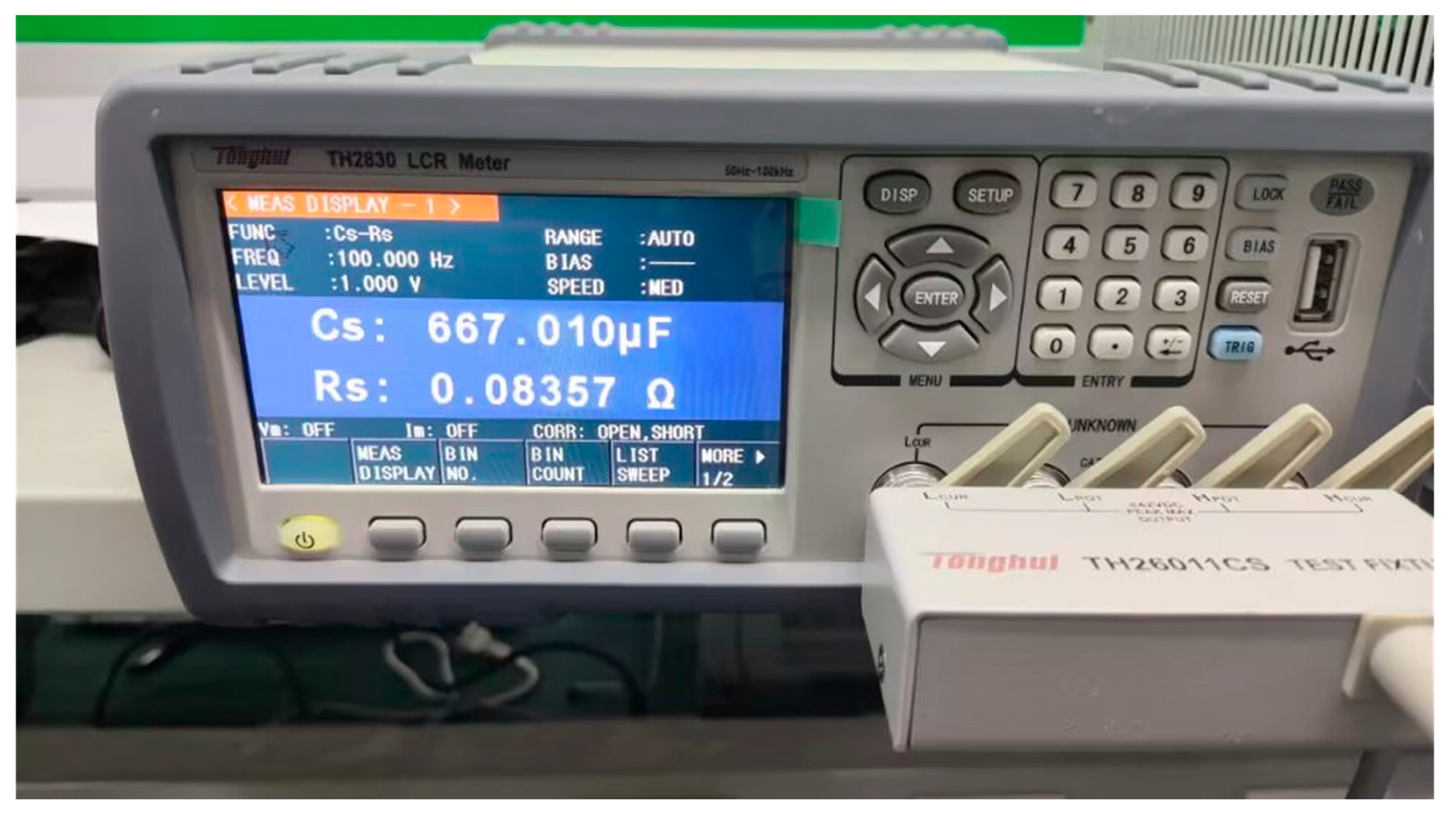

Offline monitoring methods typically require pausing system operation in order to accurately obtain key health status parameters of capacitors. In this method, using an LCR tester to directly measure the C and ESR is a typical means, with a measurement accuracy of up to 0.1%. Therefore, it is often used as a benchmark to evaluate the accuracy of other parameter identification methods. In order to simplify the configuration of measurement equipment, an experimental method based on an RC circuit was proposed in [

11]. This method analyzes the phase relationship between the capacitor terminal voltage and the input voltage and combines graphic processing and model simplification to achieve ESR extraction of capacitors in the frequency range of 100 Hz to 100 kHz. To further reduce the influence of human errors in the graphical analysis process, the Newton–Raphson numerical iteration method was introduced to achieve accurate estimation of ESR and capacitance values at a low frequency of 120 Hz by solving the nonlinear equation system describing the voltage relationship [

12]. Although the offline monitoring method has the advantage of high accuracy, its operation usually requires the removal of capacitors from the circuit, which is costly to implement and makes it difficult to meet the requirements of continuous operation and real-time evaluation of the system in practical engineering.

Online monitoring technology, as a non-invasive detection method, can obtain real-time operation status and performance parameters of capacitors under continuous circuit operation conditions. A real-time monitoring method for input and output capacitors with ESR estimation was developed for boost converters, and the influence of load, duty cycle, inductance, and temperature on ESR estimation accuracy was systematically analyzed [

13]. Another study proposes a non-invasive online monitoring technology that achieves state assessment by analyzing the correlation characteristics between capacitor voltage and current during transient processes [

14]. For flyback converters, existing studies have constructed online models suitable for continuous conduction mode and intermittent conduction mode, which can infer the capacitance value C and ESR parameters based on the voltage ripple of the capacitor [

15,

16]. However, this type of method is complex in analyzing the model, sensitive to changes in operating mode, and has limited adaptability.

In response to the above shortcomings, this paper proposes a fusion monitoring strategy based on Haar wavelet transform and Kalman filter: the switch sequence is accurately extracted from the inductor current through Haar wavelet transform, and the capacitor current can be reconstructed without additional hardware; furthermore, by utilizing the Kalman filtering algorithm, high-precision and full lifecycle online identification of capacitors C and ESR was achieved in strong noise environments. This method only requires the collection of conventional inductor current and output voltage signals, significantly improving the practicality, robustness, and engineering applicability of the monitoring system. Finally, the effectiveness of the proposed strategy under different operating conditions was verified through simulation and experiments.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 analyzed the mechanism of capacitor aging and changes in key parameters. The basic working principle of the boost converter is elaborated on in

Section 3.

Section 4 focuses on a capacitor current reconstruction method based on the Haar wavelet transform. The estimation of the C and ESR parameters using a Kalman filter algorithm is introduced in

Section 5. Simulation verification and analysis are conducted in

Section 6, followed by a systematic discussion and evaluation of the experimental results in

Section 7. Finally, the conclusion of this work is presented in

Section 8.

2. Aging Mechanism and Key Parameters of Capacitors

The aging of aluminum electrolytic capacitors is a complex electrochemical process, and its main failure modes are the decrease in C and the increase in equivalent series resistance ESR. Understanding the physical nature of these parameter changes is crucial for accurately monitoring their health status.

2.1. Aging Mechanism of Capacitors

The internal structure of aluminum electrolytic capacitors is mainly composed of anode aluminum foil, electrolyte, and cathode aluminum foil, and its dielectric layer is an aluminum oxide film generated on the surface of the anode aluminum foil through anodic oxidation. The capacitance value is determined by (1), [

17].

where

ε is the dielectric constant,

As is the effective area, and

ds is the thickness of the dielectric layer. During the lifespan of a capacitor, its geometric dimensions (

As,

ds) remain essentially unchanged. The decrease in capacitance value is mainly attributed to the decrease in effective dielectric constant. This is not due to changes in the properties of the stable alumina dielectric layer itself, but rather because the electrolyte used as the cathode gradually evaporates and decomposes under working temperature and electric field stress. The reduction in electrolyte leads to a decrease in its contact area with the dielectric layer and changes the interface characteristics, which is equivalent to a decrease in the effective dielectric constant of the overall system forming the capacitor, resulting in a continuous decrease in the measured capacitance value.

ESR is the equivalent of all active losses of a capacitor in a series equivalent model. These losses mainly include: the resistance of the electrolyte itself (the main contribution); contact resistance between electrode foil and electrolyte; and ohmic resistance of electrode leads and connection points. The volatilization and decomposition of the electrolyte directly lead to a decrease in its ionic conductivity, significantly increasing the body resistance and contact resistance, thereby causing an overall increase in ESR. Therefore, the increase in ESR directly characterizes the increase in internal power loss of capacitors.

2.2. Loss Tangent Analysis

The tangent of the loss angle (tan

δ) is a classic and important parameter for evaluating the insulation state of electrical equipment. It is defined as the ratio of active power loss to reactive power in an insulating medium. In the series equivalent circuit model of capacitors, tan

δ can be expressed as follows [

18]:

As shown in (2), tanδ is directly proportional to the product of C and ESR. As the capacitor ages, the C value decreases while the ESR value increases, and the combined effect will cause a significant change (usually an increase) in tanδ. Therefore, tanδ is a sensitive parameter that can comprehensively reflect the degradation of capacitor insulation performance.

2.3. Complex Impedance Analysis

The aging state of capacitors is fully reflected in the frequency characteristics of their complex impedance

Z(

f). As described in

Section 2.2, in the series model, the modulus and phase angle are [

19]

In theory, by accurately measuring the impedance modulus and phase angle of a capacitor at a certain frequency, both C and ESR can be calculated simultaneously. This is exactly the basic principle of many offline monitoring instruments. However, online and non-invasive monitoring in DC–DC converters faces challenges: On the one hand, the excitation signal is limited, and the system itself does not provide pure sine excitation for sweep frequency measurement. On the other hand, capacitor current and voltage ripple are non-sinusoidal signals containing switching noise, and it is very difficult to accurately extract impedance phase angle information directly from them.

In response to the above challenges, this article proposes a robust monitoring strategy based on time-domain analysis in strong noise and non-sinusoidal excitation environments. By accurately tracking the changes in C and ESR, this method effectively avoids the problem of extracting impedance phase angle online and can also be used for indirectly detecting the insulation state of capacitors.

3. Working Principle of Boost Converter

Boost converters have been widely used in the energy distribution of aircraft power systems due to their efficient energy conversion and flexible voltage regulation characteristics [

20].

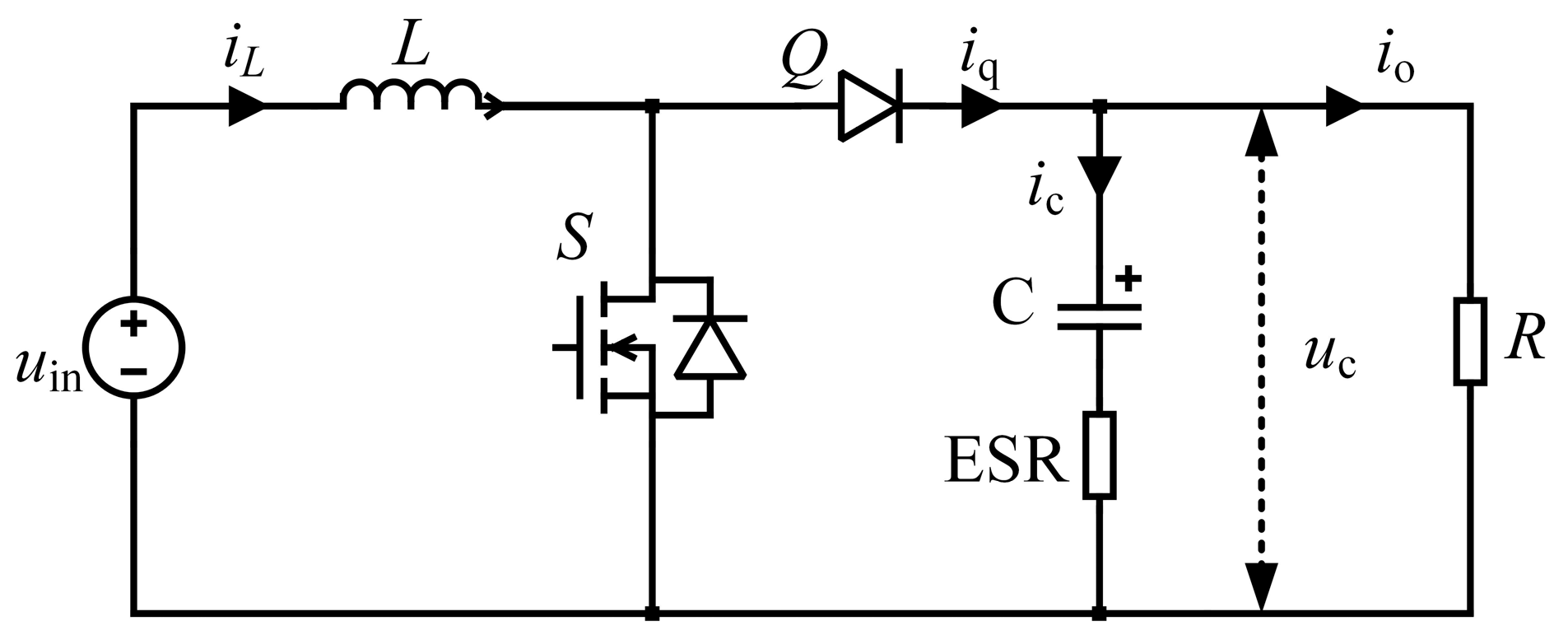

Figure 2 shows the topology of a typical boost converter, which mainly consists of input power supply

uin, power inductor

L, switch tube

S, diode

Q, output capacitor C and its ESR, and load

R.

When the switch tube is conducting, the switch tube S is approximately in a short-circuit state. The input power uin charges the inductor L, and the inductor current iL increases, resulting in an increase in inductor energy storage; at the same time, the output capacitor C independently supplies power to the load R to maintain the load current ic, resulting in a gradual decrease in the output voltage uc.

When the switch tube is turned off, the switch tube S is in an open-circuit state, and the energy stored in the inductor L is released through the freewheeling diode Q, and together with the input power source uin, it supplies power to the load while charging the output capacitor C. During this process, the inductor current iL decreases and the output voltage uc increases accordingly.

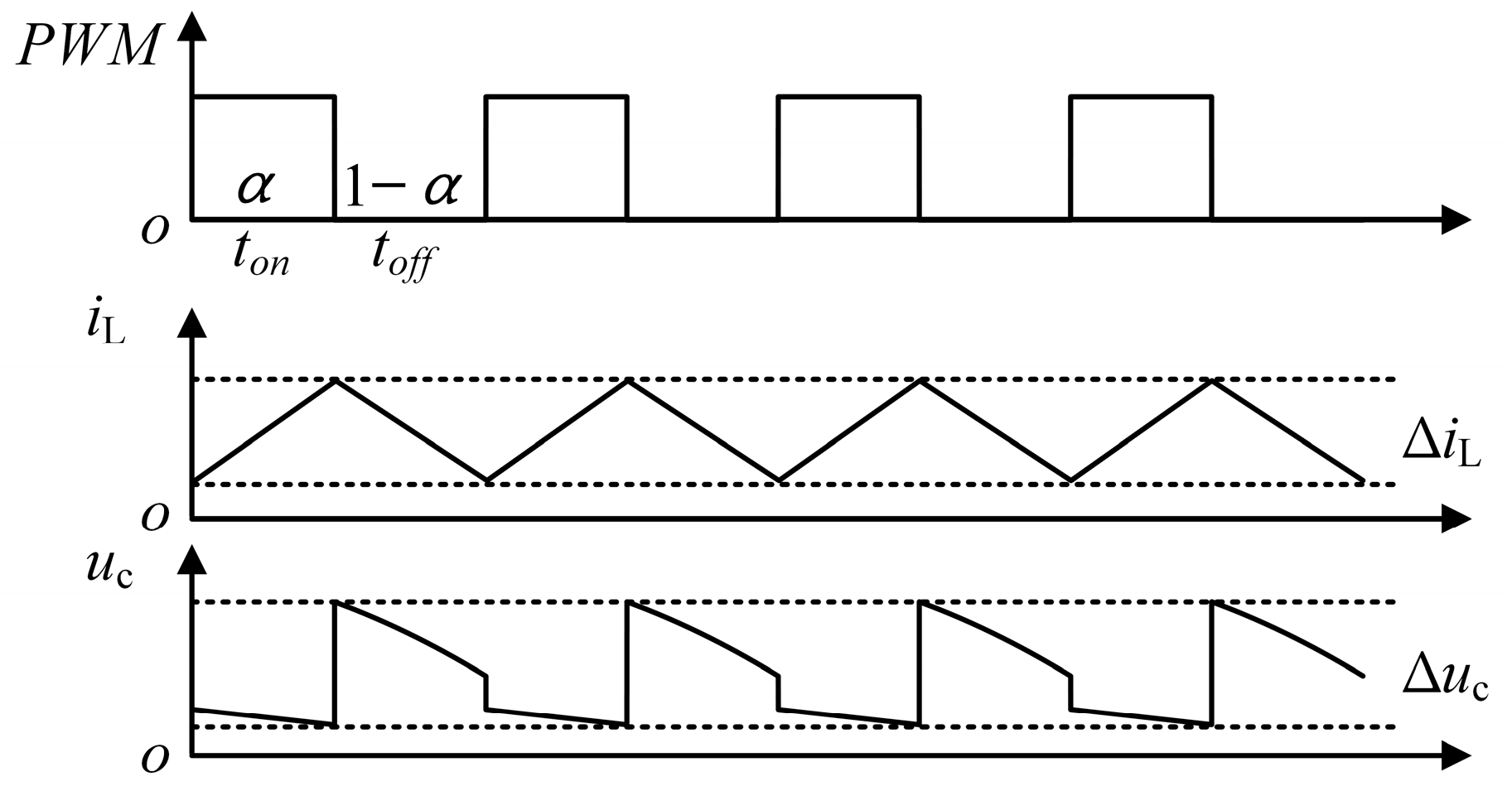

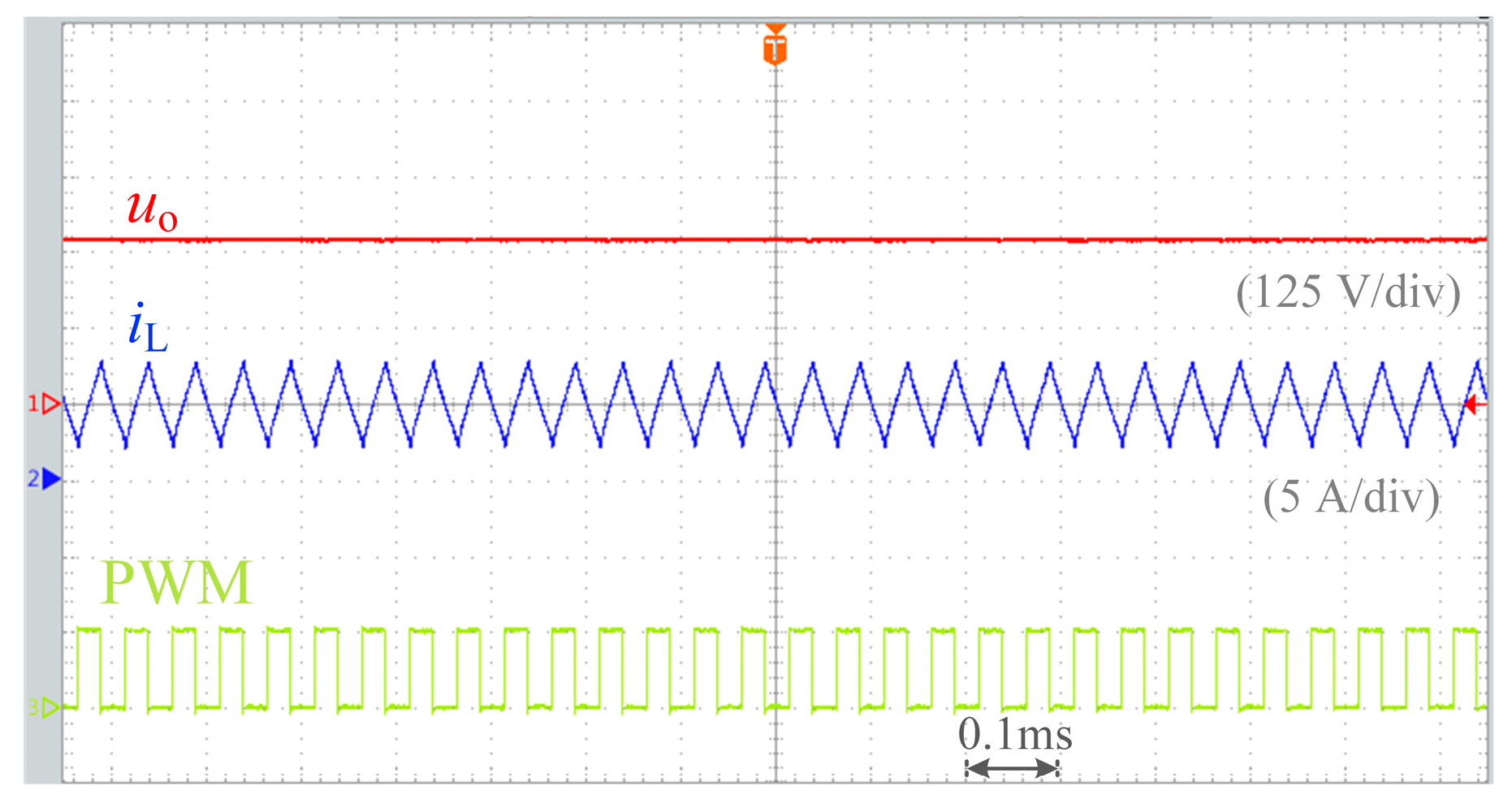

This paper focuses on the steady-state operating characteristics of converters in continuous conduction mode (CCM). The steady-state operating waveform of C and ESR in series is shown in

Figure 3, revealing the dynamic correlation between switch signals, inductor current, and output voltage. It is crucial to note that the monitoring methodology developed in this work is specifically designed for and validated under this CCM regime. The reason for choosing CCM is that the core requirements for high efficiency, high reliability, high power density, and low electromagnetic interference in aviation applications fundamentally contradict the inherent characteristics of discontinuous conduction mode (DCM), such as large current ripple, high component stress, and significant electromagnetic interference. Due to the above advantages, CCM has become the preferred solution for this type of application. Furthermore, the subsequent capacitor current reconstruction strategy fundamentally relies on the continuous and periodic nature of the inductor current in CCM. Its direct application to DCM is precluded, as the DCM operation, characterized by periods of zero inductor current, violates this core signal prerequisite.

5. Capacitor State Monitoring Based on Kalman Filter

To achieve accurate monitoring of capacitor C and ESR, it is necessary to establish a discrete relationship model between capacitor terminal voltage and current in the time domain. Firstly, based on the working principle of the boost circuit, the transfer function between the capacitor terminal voltage and current can be derived, as shown in (18).

Further using the Tustin transform method shown in (19), discretize (18) to obtain the discrete form shown in (20), where Δ

t represents the sampling period.

Finally, transform the variable relationships described in (20) into a structural form suitable for parameter identification:

According to the parameter identification form established in (21), it can be incorporated into the framework of Kalman filtering (KF) for solving. This form is highly consistent with the standard state space model of KF, where the terminal voltage of the capacitor can be used as an observed variable, and the capacitance C to be accurately estimated and the equivalent series resistance ESR together form the state vector of the system.

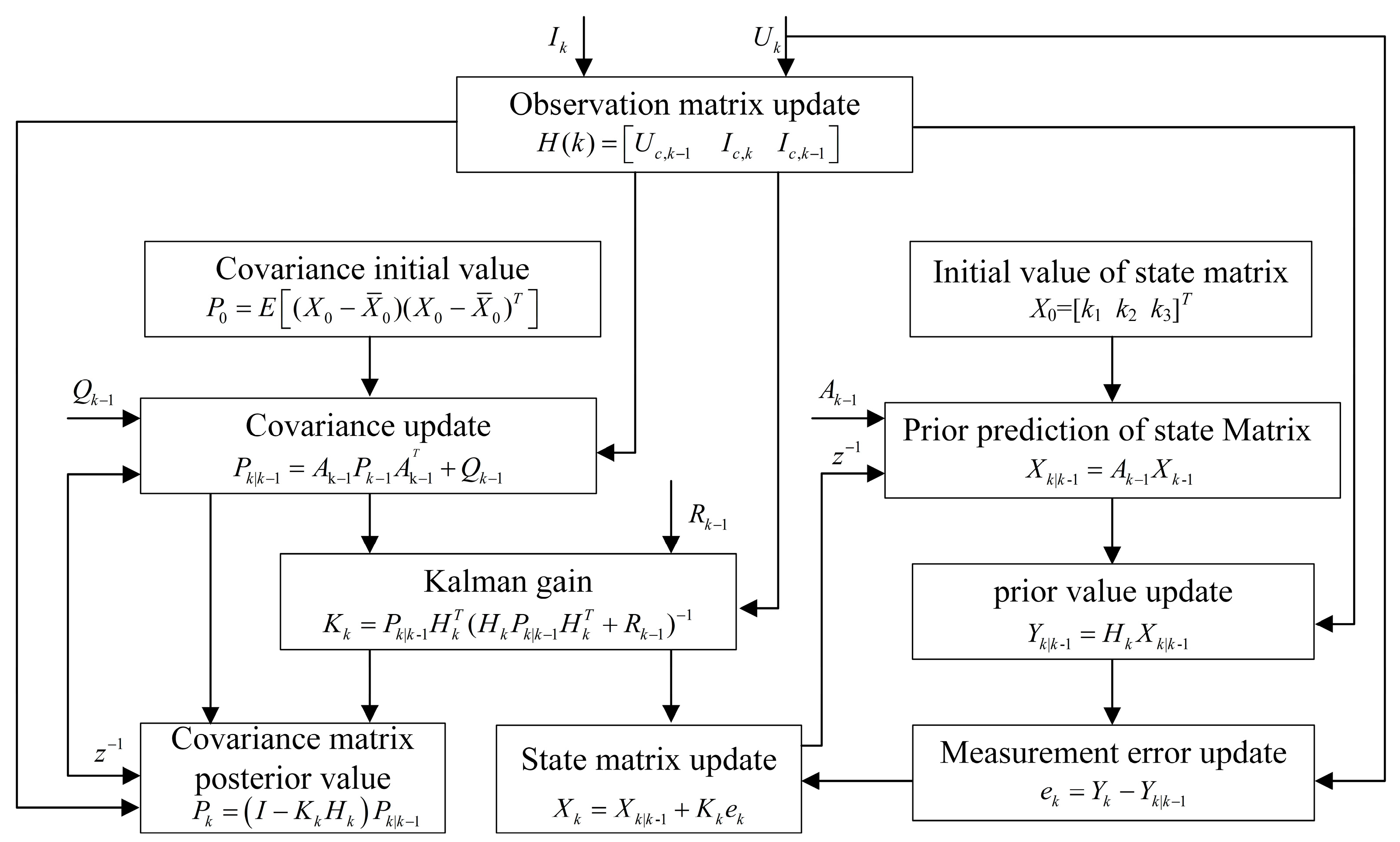

The KF algorithm mainly consists of two equations: the state equation and the measurement equation, as shown in (22) and (23), respectively [

28,

29]:

Among them,

X(

k) represents the state vector at time

k;

A(

k) represents the state transition matrix, which is used to establish an iterative relationship between the state variables at the previous

k − 1 time and the current

k time;

T(

k) represents the noise driven matrix;

ωk represents process noise excitation;

Y(

k) represents the observation vector;

H(

k) represents the observation matrix; and

vk represents observation noise excitation. It should be noted that

ωk and

vk are uncorrelated Gaussian white noise with a mean of 0 and follow a normal distribution, namely

ωk~

N(0,

Qk),

vk~

N(0,

Rk), where

Qk is the covariance matrix of process noise and

Rk is the covariance matrix of observation noise [

30].

To achieve capacitor parameter identification, this study collected inductor current and voltage data during the operation of the boost converter, extracted capacitor current using Haar wavelet transform, and then performed state estimation based on KF method. In this model, matrices

A and

T are identity matrices, and the terminal voltage

Uc is the observation vector

Y. The noise covariance

R and

Q are adjusted according to the system accuracy to obtain. The state vector

X and observation matrix

H of the KF can be derived from (21), corresponding to (24) and (25), respectively:

The relationship between C and ESR can be derived from (21) and (24) as follows:

Construct the online monitoring process shown in

Figure 5 based on the derived state and measurement equations. This process is based on the KF algorithm, which recursively estimates the state vector by inputting the capacitor terminal voltage and operating current in real time and directly solves and outputs the online identification results of capacitor C and ESR.

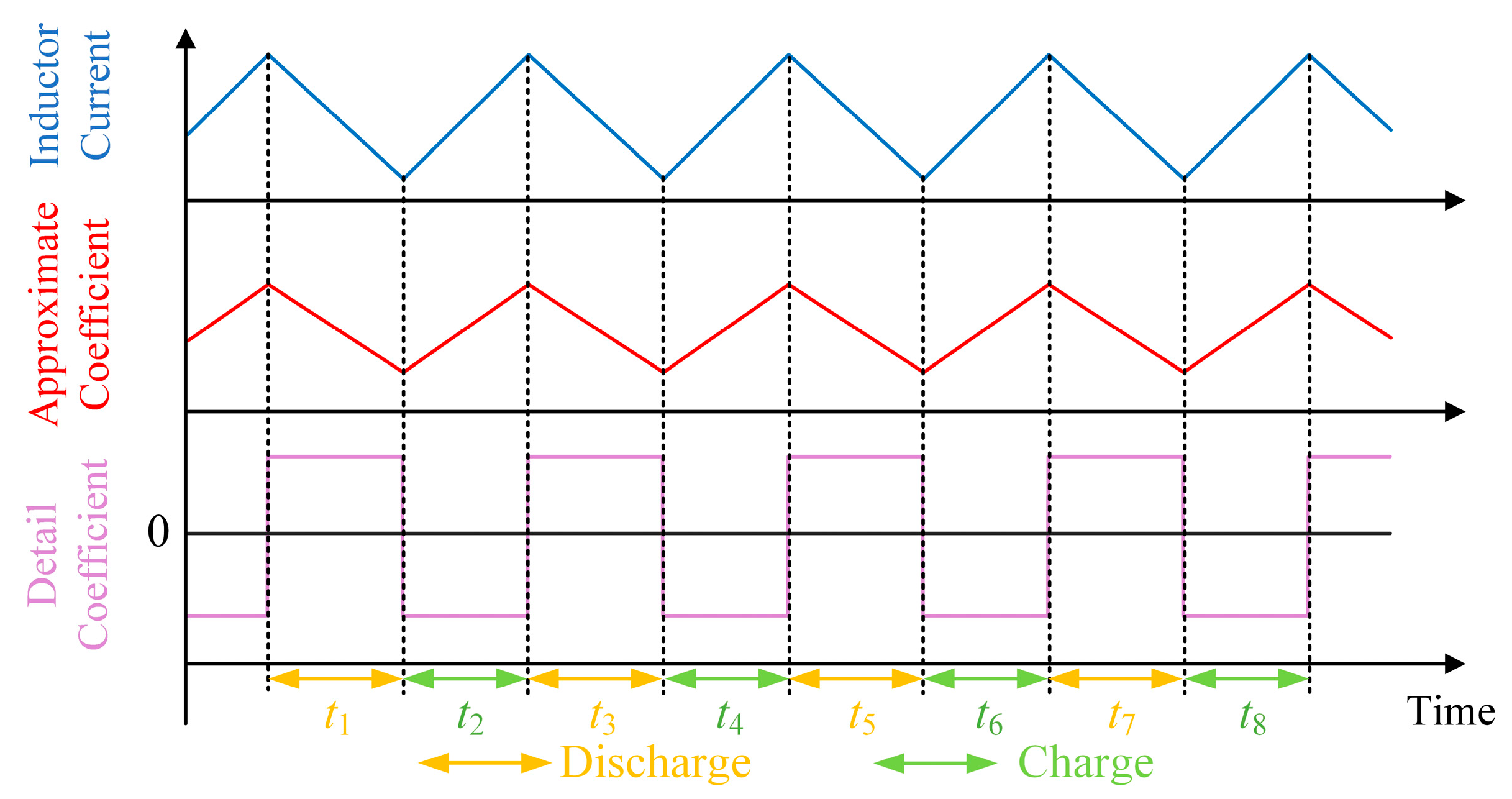

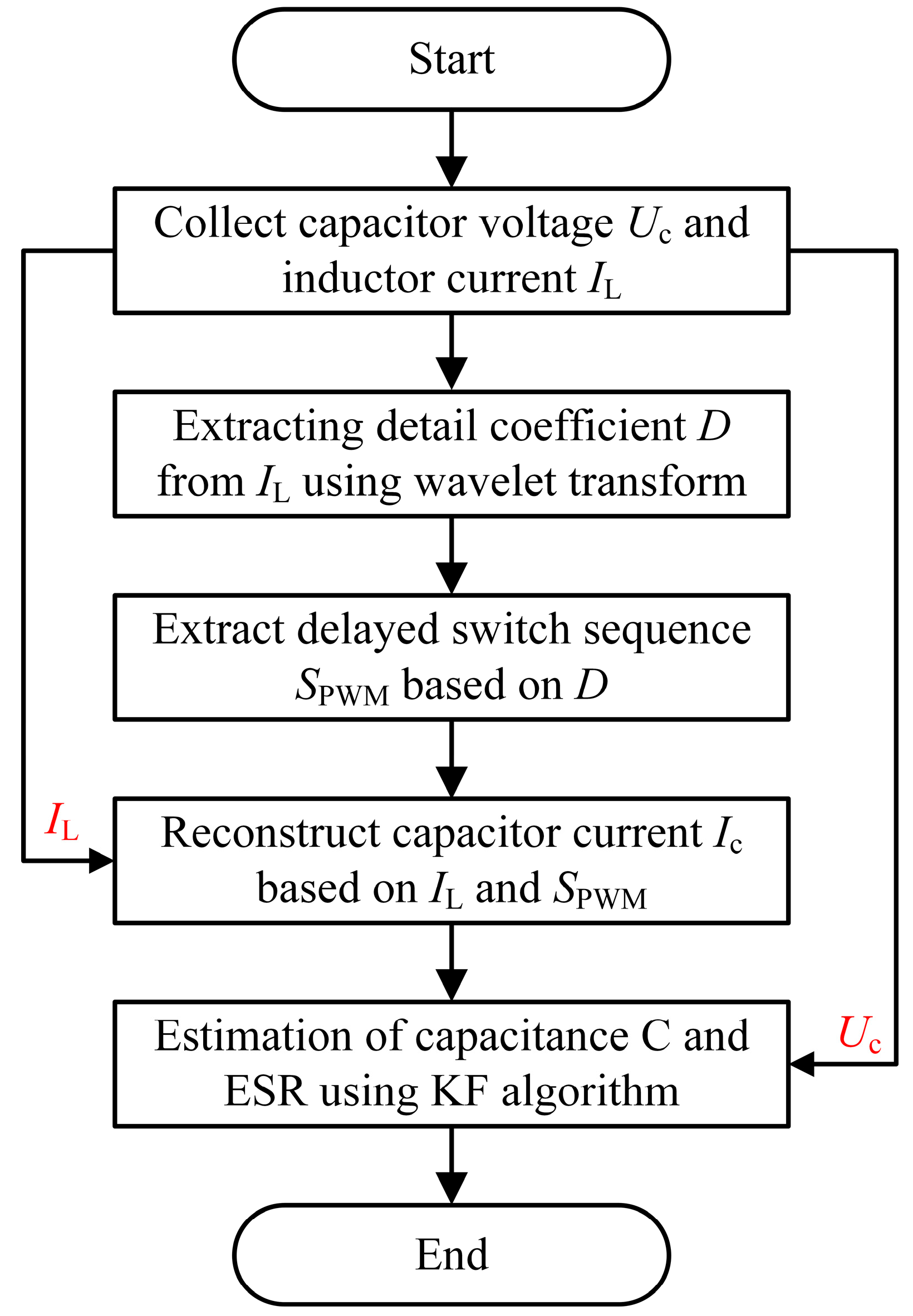

The process of the method used in this chapter is shown in

Figure 6. Firstly, collect the inductor current and capacitor voltage signals from the boost converter; subsequently, the inductance current was subjected to Haar wavelet transform using (8) to extract its detail coefficient

D. According to

Table 1, the switch sequence

SPWM delayed by one sampling period was derived from the detail coefficient

D. Combine the switch sequence with the inductor current and reconstruct the capacitor current through (17). Furthermore, the measured capacitor voltage is combined with the reconstructed capacitor current to construct the state space equation of the system. Finally, based on the KF algorithm, the state space equation is solved to achieve accurate estimation of capacitance C and ESR.

The state space model proposed in this article is derived from the ideal topology of the boost converter, aiming to clearly explain the core theoretical basis of the method. This model has not explicitly considered non-ideal factors such as inductance parasitic resistance, switch voltage drop, PCB routing resistance, etc. However, it should be emphasized that the KF algorithm itself has inherent robustness to a certain degree of model uncertainty. In the state estimation process, the effects of these unmodeled dynamic characteristics and parasitic parameters can be effectively incorporated and absorbed into the process noise covariance matrix Qk. By adjusting Qk and Rk appropriately, the filter can compensate for model mismatch to some extent, thus still achieving accurate state estimation.

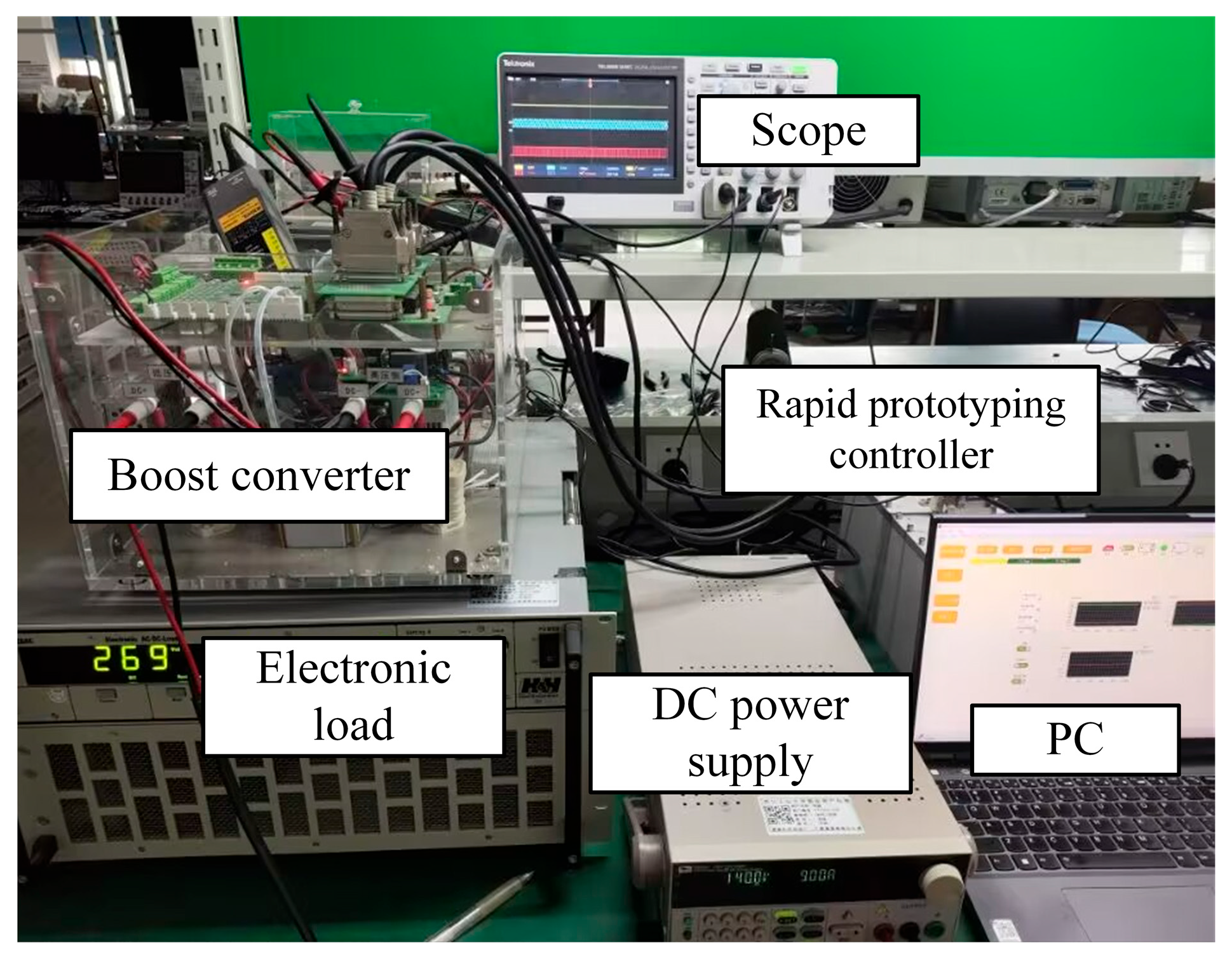

6. Simulation Verification

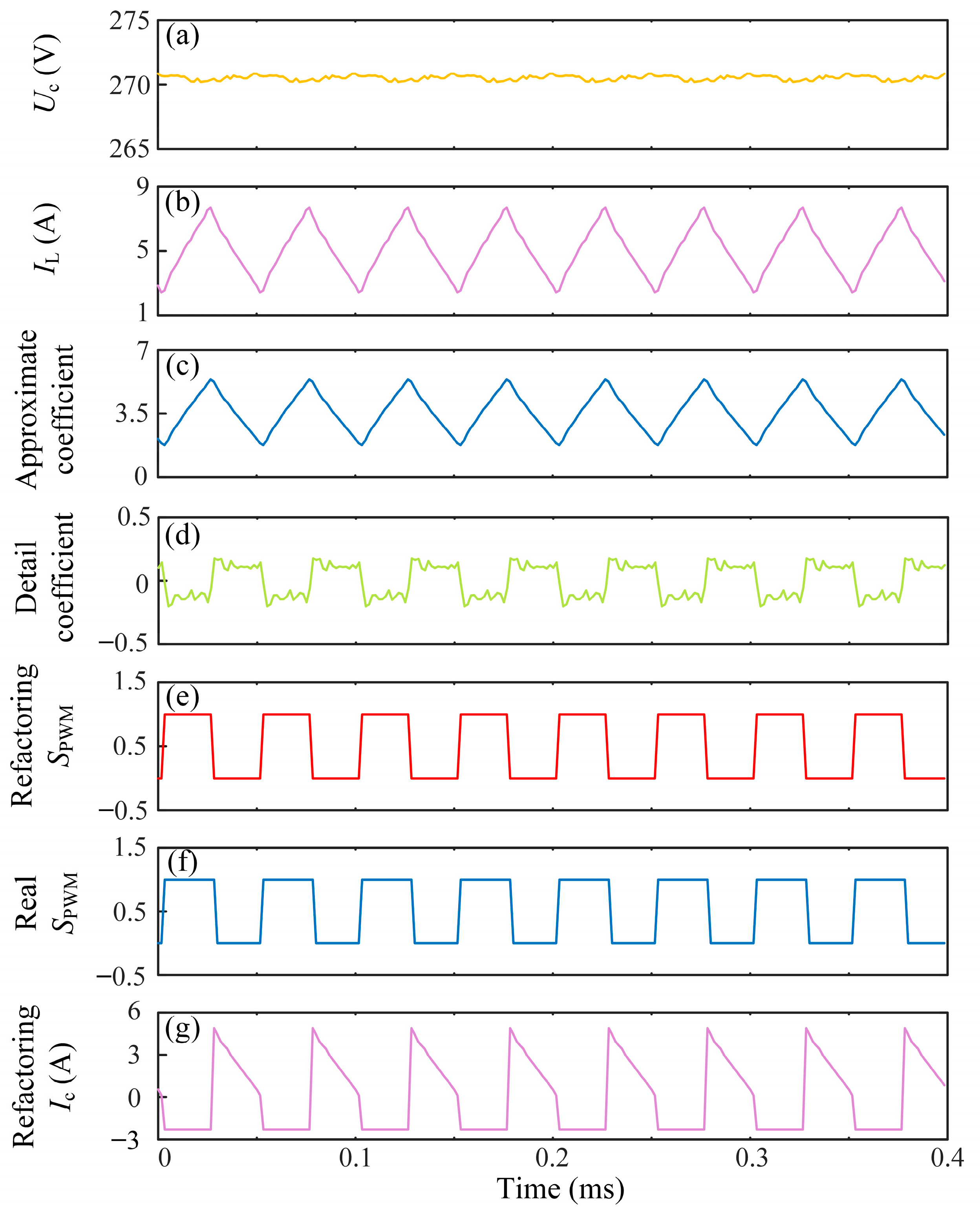

Based on the monitoring algorithm proposed in the previous text, a simulation model of the boost converter was built in the Plecs 4.8 environment. In this model, the output capacitance is characterized in the form of an ideal capacitor series with equivalent resistance, and the system controller adopts a PI control strategy. The data processing adopts Origin 2024b. During the simulation process, the inductor current signal and capacitor voltage signal are synchronously collected for the validation of subsequent capacitor state monitoring algorithms; at the same time, the waveform of the capacitor current is recorded to evaluate the effectiveness of the capacitor current reconstruction method based on Haar wavelet transform.

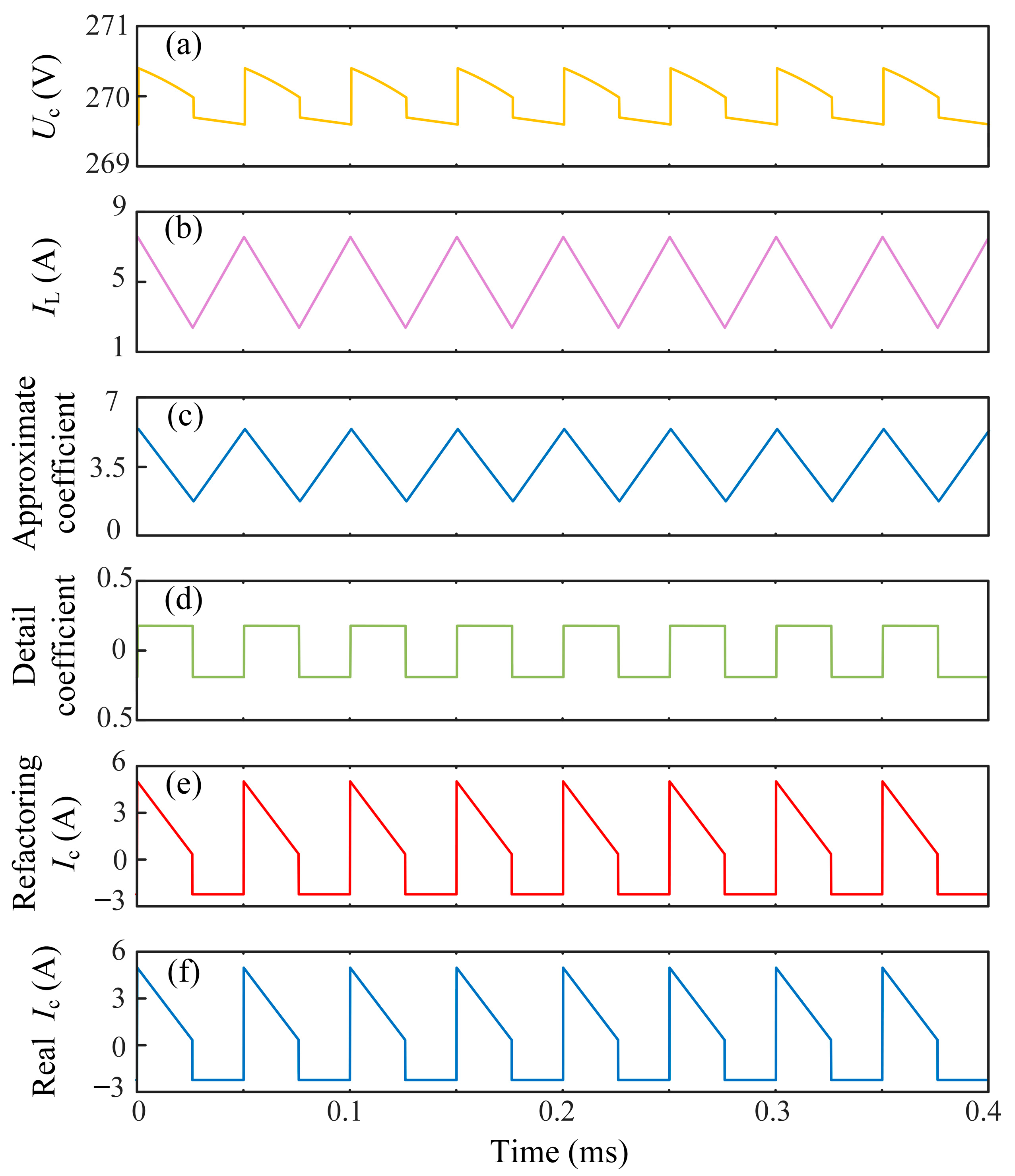

The simulation model and parameters (listed in

Table 2) are established based on a typical set of components from a single manufacturing batch, aiming to validate the fundamental principle of the proposed method. The experimental object is the steady-state operating condition of the boost converter under a 0.4 ms operating cycle, and its key waveform is shown in

Figure 7. Among them,

Figure 7a is the collected capacitor voltage waveform, which will serve as the basis for subsequent capacitor electrical parameter estimation. The waveform of the collected inductor current is shown in

Figure 7b. By performing Haar wavelet transform on the current signal, the approximate coefficients are obtained as shown in

Figure 7c. It can be seen that the approximation coefficient preserves the main trend and dynamic characteristics of the original inductor current well. On the other hand, the detail coefficients obtained from wavelet transform are shown in

Figure 7d. This detail coefficient contains high-frequency switch information of the system, which can be used to extract a sequence of switch states delayed by one sampling period. Based on the extracted switch sequence and inductor current information, the reconstructed capacitor current waveform is shown in

Figure 7e. By comparing and analyzing it with the actual capacitance current obtained through data collection in

Figure 7f, it can be seen that both have good agreement in amplitude and phase, and the waveform characteristics are basically the same. The simulation model and parameters (listed in

Table 2) are established based on a typical set of components from a single manufacturing batch, aiming to validate the fundamental principle of the proposed method.

To verify the accuracy of the KF algorithm in estimating capacitance C and ESR, the capacitance simulation model was set with C at 680 μF and ESR at 0.1 Ω. By collecting the voltage across the capacitor and combining it with the reconstructed capacitor current, the system evaluates the accuracy and robustness of the capacitor state monitoring algorithm under different sampling frequencies, capacitor lifecycles, different input voltages, and noise interference environments.

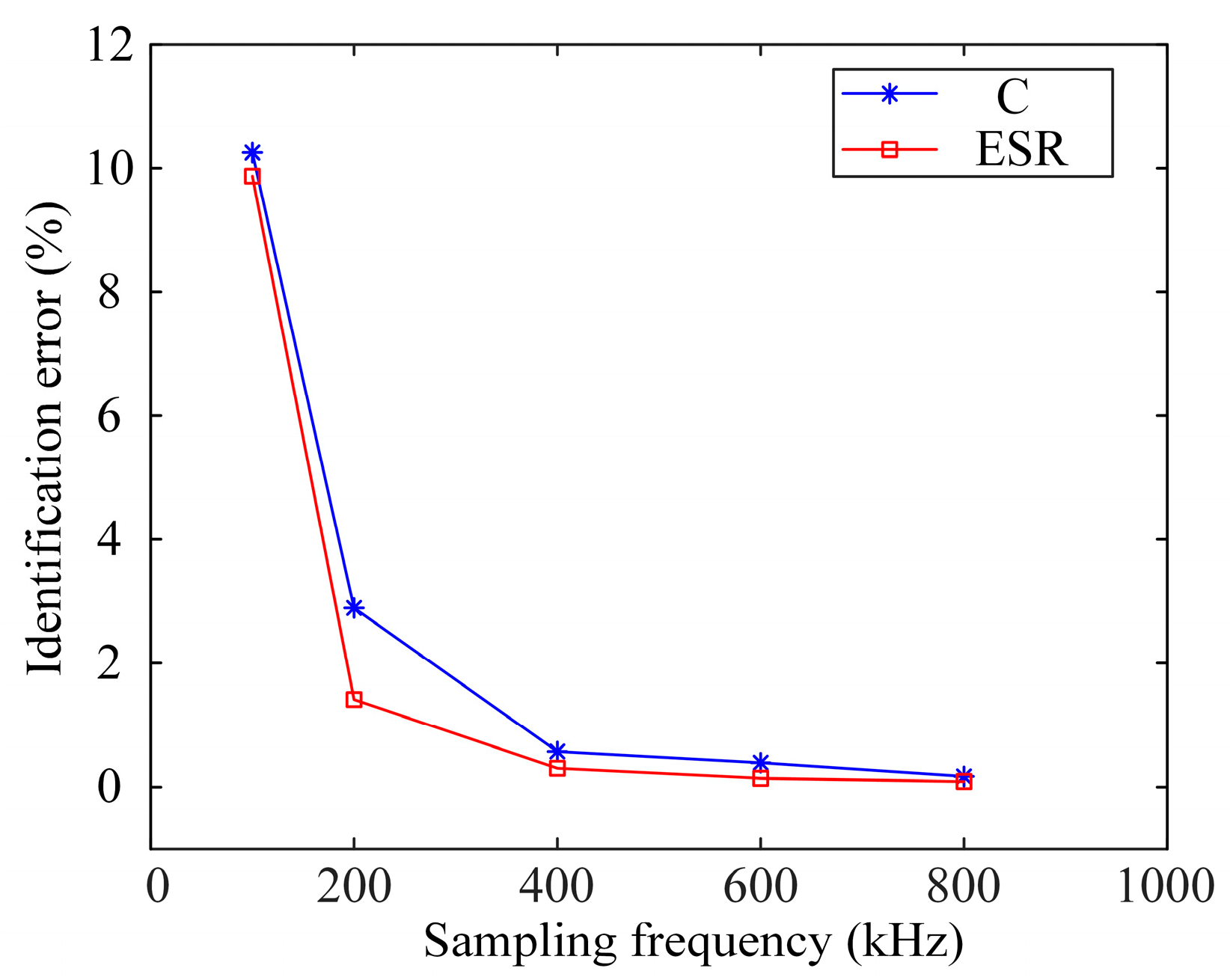

To evaluate the impact of sampling frequency on the accuracy of electrolytic capacitor parameter identification, this paper conducted comparative experiments using four sampling frequencies: 200 kHz, 400 kHz, 600 kHz, and 800 kHz, based on a switching frequency of 20 kHz. By analyzing the identification results of C and ESR at different sampling frequencies, the effects of sampling rate on the stability and accuracy of parameter estimation were evaluated. The identification results are shown in

Table 3. The identification errors of C and ESR are shown in

Figure 8.

The identification results show that the estimation error of C and ESR can be controlled within 3% in the frequency range of 200 kHz to 800 kHz. When the sampling frequency is increased to 400 kHz, the identification accuracy of C and ESR is significantly improved; when the sampling frequency is further increased to 800 kHz, the accuracy improvement effect gradually approaches saturation. This phenomenon indicates that moderately increasing the sampling frequency helps to suppress the interference of high-frequency switching noise on parameter identification, but excessively high sampling rates have limited contribution to accuracy improvement. Therefore, a sampling rate of 400 kHz (20 times the switching frequency) is established as a benchmark that effectively balances high identification accuracy with computational load for the proposed method. Given that high sampling frequency significantly increases the data storage and processing burden of the system, and with a focus on finding a balance between accuracy and resource consumption, future work will set the sampling frequency for capacitance parameter identification based on the KF algorithm to 400 kHz. It is noteworthy that for applications where the switching frequency is inherently lower, this 20× ratio principle allows the method to be implemented with a correspondingly lower, more feasible sampling rate on resource-constrained hardware.

- 2.

Capacitor lifecycle

Considering that the C and ESR of electrolytic capacitors undergo significant changes with aging during long-term operation, it is necessary to effectively monitor their entire lifecycle status. This paper takes the nominal capacitance value of 680 μF and ESR of 0.1 Ω as the initial healthy state, and the failure threshold is set as the capacitance value dropping to 80% of the initial value (544 μF) and ESR rising to twice the initial value (0.2 Ω). To verify the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed parameter identification algorithm, testing and analysis were conducted at five typical aging stages: 0% (initial state), 25%, 50%, 75%, and 100% (failure state). The identification results are shown in

Table 4.

From the data in

Table 4, it can be seen that at different aging stages, the predicted values of capacitor C and ESR are highly consistent with the true values. The maximum relative error of capacitor C is 0.70% (100% aging state), and the minimum is 0.48% (75% aging state); the maximum relative error of ESR is 0.51% (100% aged state) and the minimum is 0.23% (50% aged state). The relative error of C and ESR identification under all operating conditions remains within 1%, indicating that the parameter identification method proposed in this paper has good estimation accuracy and robustness under different aging states and can effectively achieve state monitoring of the entire life cycle of electrolytic capacitors.

- 3.

Different input voltages

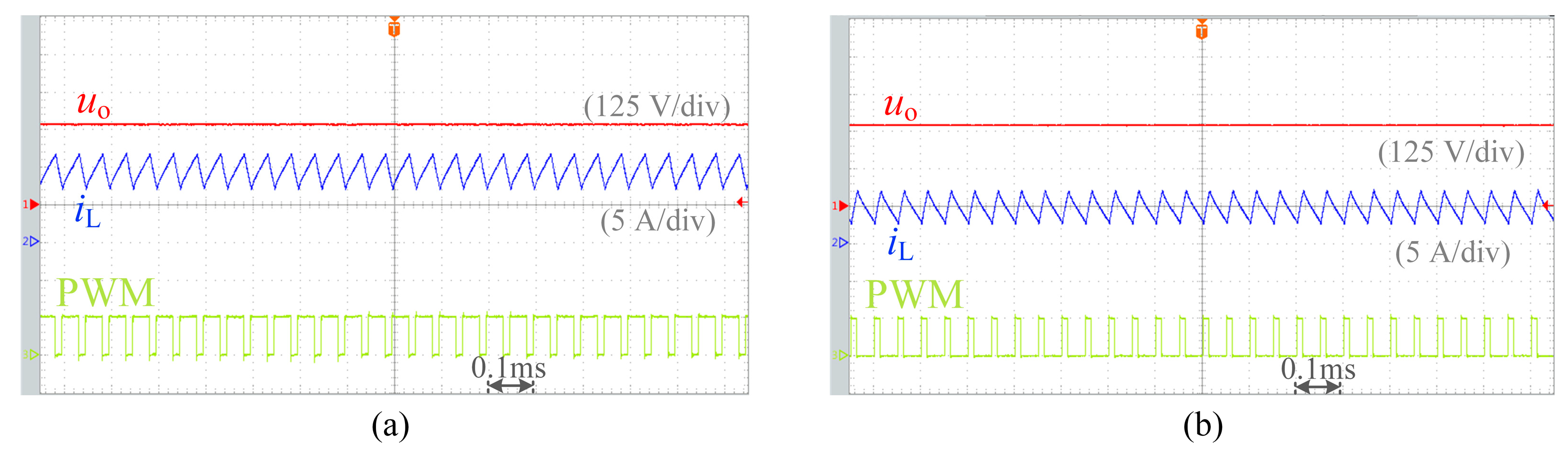

Under different power conditions, the monitoring of capacitor status will have an impact on the accuracy of parameter identification due to changes in the circuit operating point. To evaluate the impact of this factor, this paper constructs different power operating conditions by adjusting the input voltages to 80 V, 140 V, and 200 V while ensuring that the output voltage of the boost converter is stable at 270 V. The capacitor parameter identification method is simulated and verified under these conditions.

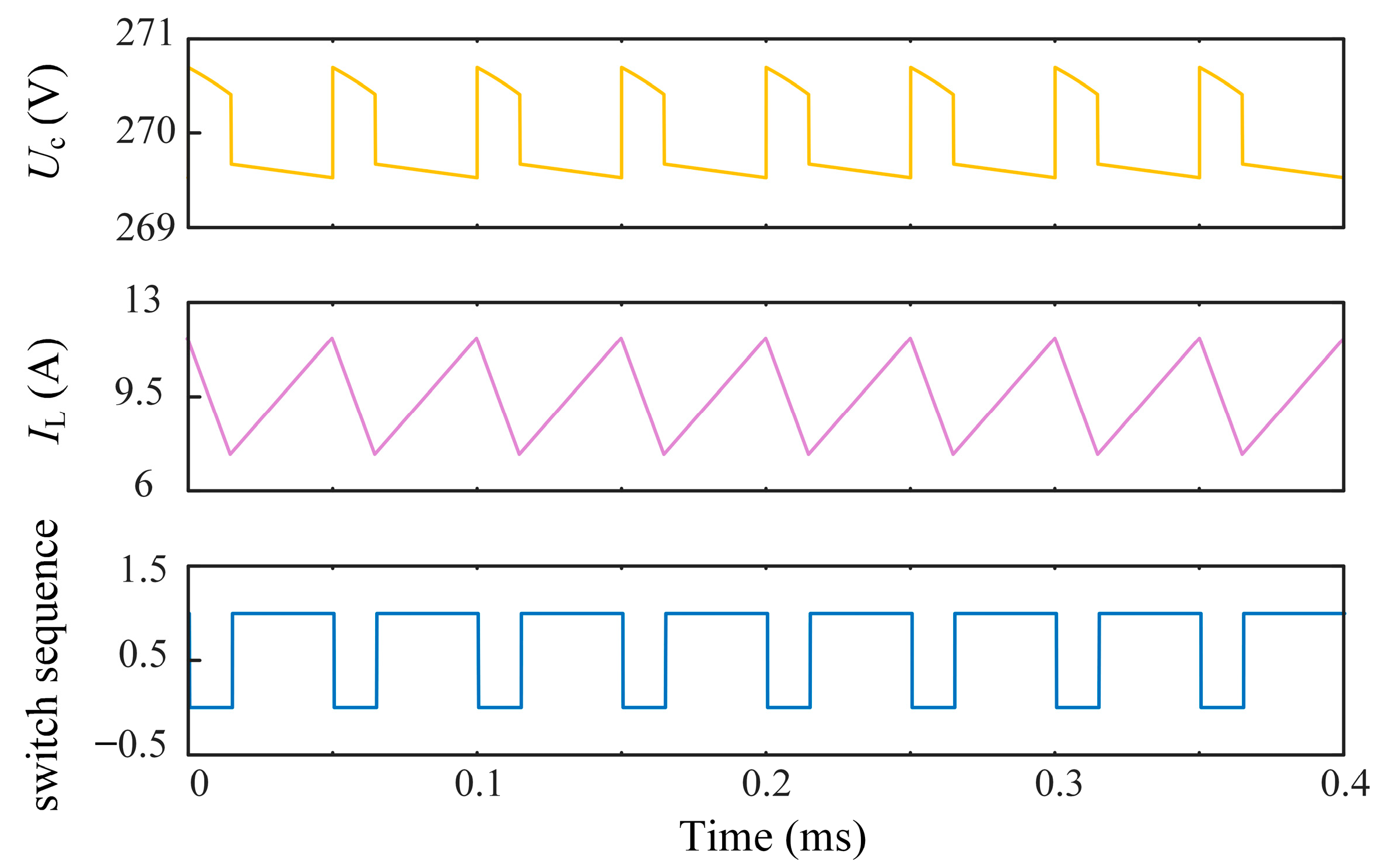

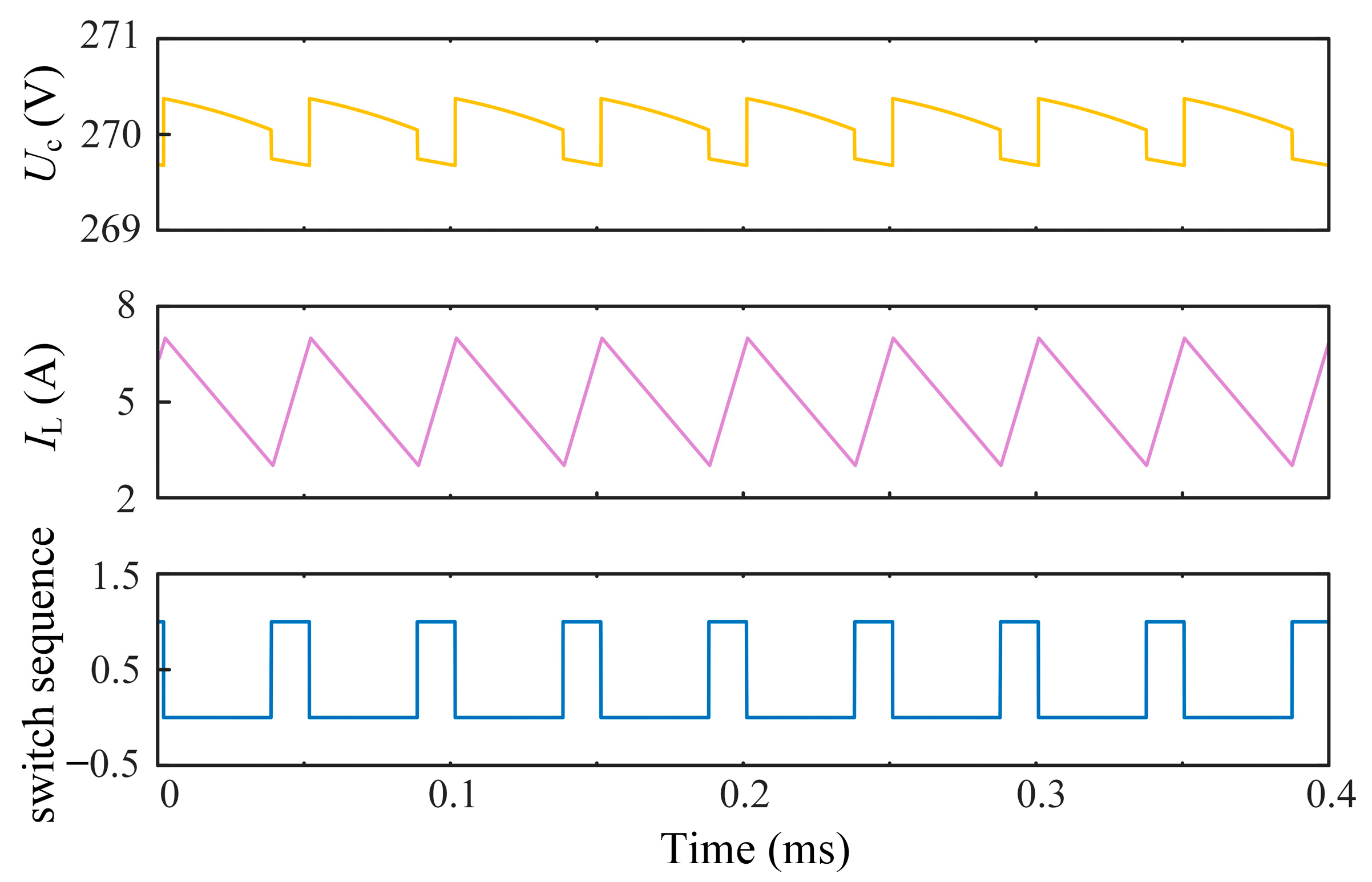

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 show the capacitor voltage, inductor current, and switch sequence waveforms corresponding to input voltages of 80 V and 200 V, respectively.

The identification results obtained by setting C to 680 μF and ESR to 0.1 Ω are shown in

Table 5. From the identification results, it can be seen that under different input voltage conditions, the identification results of capacitor C and ESR are highly consistent with their actual values, and the maximum relative errors do not exceed 1%, indicating that the parameter identification method proposed in this paper has good accuracy and robustness. However, as the input voltage increases, the identification error shows a gradually increasing trend. Specifically, the identification error of capacitor C increased from 0.31% at 80 V input to 0.73% at 200 V input; the identification error of ESR also increased from 0.19% to 0.51%. The main reason for this phenomenon is that when the input voltage increases, the duty cycle of the boost converter decreases accordingly, resulting in a decrease in the ripple amplitude of the capacitor current and output voltage. Due to the fact that ripple is a dynamic excitation signal in the parameter identification process, its amplitude reduction will weaken the ability to extract key state information, while the measurement noise level remains basically unchanged, resulting in a decrease in the system’s signal-to-noise ratio. This change affects the convergence performance of the KF, causing a slight decrease in parameter identification accuracy with increasing voltage.

- 4.

Noise interference

Under the Gaussian white noise model, system noise is usually assumed to have uniformly distributed frequency components. Although this assumption is convenient for theoretical analysis under ideal conditions, there is a certain gap between it and the statistical characteristics of noise in actual aviation operating environments. To more accurately evaluate the performance of the proposed method under near real aviation conditions, this study introduces colored noise with strong correlation as the testing condition. The colored noise is generated by a first-order autoregressive model:

where

λk+1/k = 1.0001,

ek~

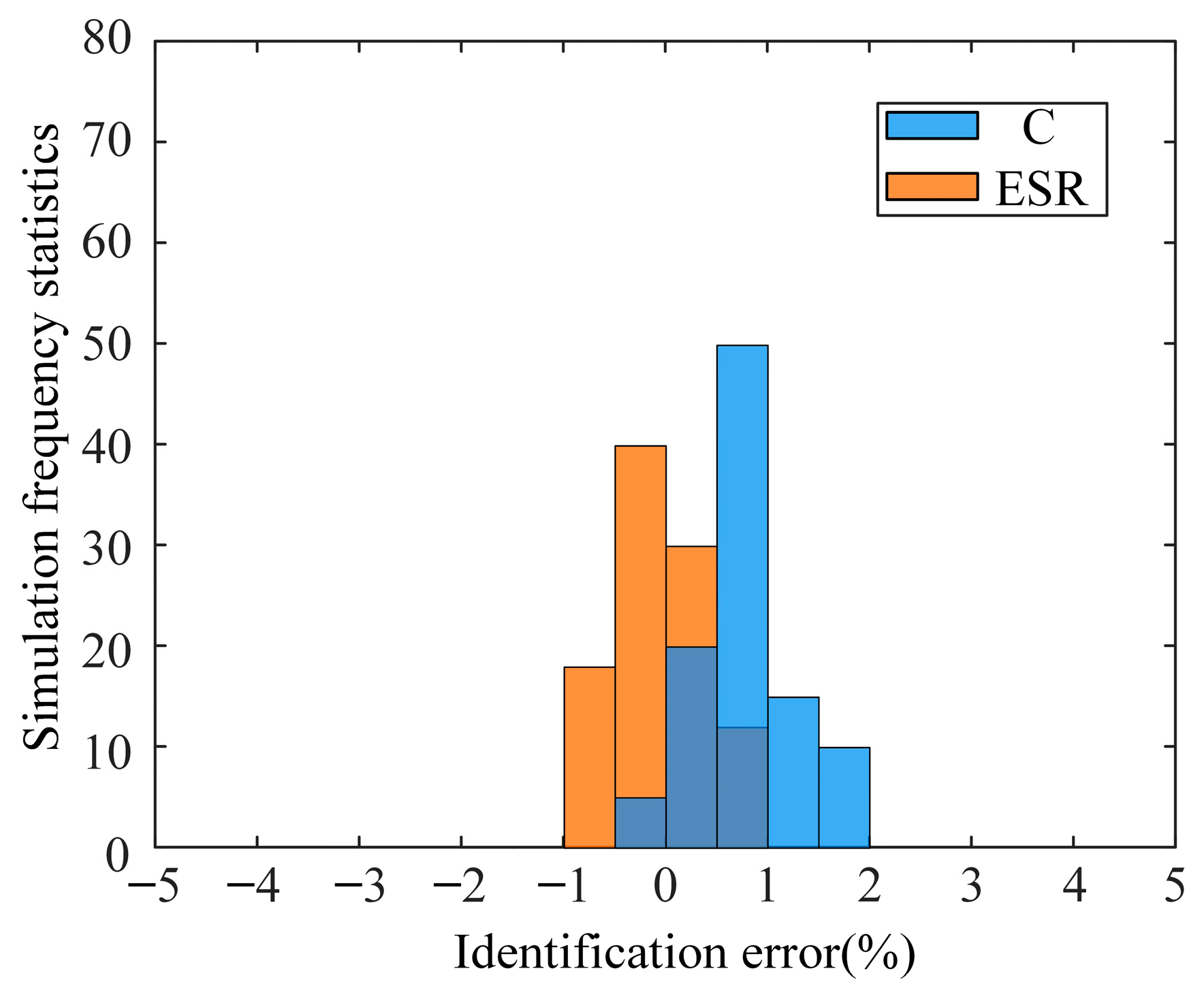

N(0,0.006). To eliminate the influence of random errors on the identification results, independent simulations were repeated 100 times for each noise configuration. The current and voltage observation signals obtained each time were input into the KF algorithm for parameter identification, and the identification error distribution was finally calculated as shown in

Figure 11.

According to

Figure 11, in 100 independent simulation experiments, the identification error of capacitor C is mainly concentrated in the range of −0.5% to 2%, and the identification error of ESR is mainly concentrated in the range of −1% to 1%. The vast majority of error samples are concentrated around zero, with the highest proportion of errors within ± 2%, reflecting the good noise suppression ability of the KF. This error distribution further validates the effectiveness and robustness of the parameter identification method proposed in this paper in noisy environments.

8. Conclusions

This paper proposes an online monitoring method that integrates Haar wavelet transform and KF for the state monitoring requirements of boost converter aluminum electrolytic capacitors in multi-electric aircraft. The research focuses on solving two core problems: non-invasive reconstruction of capacitor current and high-precision identification of key parameters throughout their lifecycle.

Firstly, a switch sequence extraction and capacitor current reconstruction strategy based on Haar wavelet transform is proposed. This method only requires the collection of inductance current signals during regular operation, and by analyzing the polarity changes in its detail coefficients, accurately restores the switch sequence, thereby achieving non-invasive reconstruction of capacitor current without the need for additional hardware. Furthermore, a discrete state space model of the capacitor is established, combined with the KF algorithm, to recursively estimate C and ESR under strong noise background, achieving high robustness online identification of key parameters.

Simulation and experimental results show that the fusion monitoring method exhibits excellent performance under various operating conditions, including different sampling frequencies, aging degrees, input voltages, and noise environments. In simulation, the identification error between capacitor C and ESR can be controlled within 1%; under experimental conditions, the recognition errors of C and ESR were less than 3% and 2%, respectively, verifying the comprehensive advantages of this method in accuracy, robustness, and engineering applicability. It should be pointed out that the experimental validation of this study is currently based on a single capacitor sample. Although the proposed method achieved satisfactory accuracy on this component, future work will include statistical validation on multiple components and units to further confirm the universality and robustness of the method across a wider range of component differences. Furthermore, extending the proposed methodology to handle DCM operation represents another critical direction for future research, aiming to broaden the applicability of this monitoring strategy across all potential converter operating conditions. This study provides a practical and efficient solution for online status monitoring and predictive maintenance of key capacitive components in aviation grade DC–DC converters.