Abstract

The wafer test is an essential component of semiconductor manufacturing. Rapid and accurate diagnosis of defects in a wafer test produces practical industrial values. However, the existing deep learning-based methods for wafer testing, although achieving excellent performance, face challenges in their reliance on extensive training datasets and the intricacy of models. To address these challenges, this paper proposes an efficient detection method based on inductive transfer learning for wafer-test-induced defects. By exploiting the visual feature extraction capability of the pre-trained model, the method requires only hundreds of wafer map data points for fine-tuning and achieves high detection accuracy. In addition, a progressive model-pruning flow is proposed to compress the model while maintaining accuracy. Experimental results show that the proposed method achieves detection accuracy as high as 100% for the wafer-test-induced defects on the validation set, while the pruning flow reduces the model size by 10.2% and the number of computational operations by 83.7%. The detection method achieves 61.7 FPS processing speed on an FPGA-based accelerator, enabling real-time defect detection.

1. Introduction

The integrated circuit (IC) test represents a pivotal stage in the IC industry, verifying whether ICs adhere to stringent design specifications and performance targets. This stage plays an essential role in design validation, yield enhancement, quality control, and failure analysis [1].

The IC test is typically partitioned into two phases: the wafer-level test, commonly referred to as the chip probe (CP), and the final test (FT). The wafer test focuses on electrical examinations to identify non-functional dies, thus preventing defective chips from entering the packaging stage. In contrast, the FT delivers a comprehensive validation of structural integrity, functional behavior, and extensive electrical characteristics after packaging. The widespread adoption of multi-die packaging has significantly reduced the accessibility of individual chips, underscoring the increasing importance of the wafer test in preempting downstream defects. Early detection at the wafer stage not only improves yield but also reduces cost and enhances overall throughput.

The wafer test is performed with automatic test equipment (ATE) to detect defects caused by the fabrication process. However, the test process can also introduce defects in the wafer, such as the contact issue. A digital wafer map generated by the ATE is attached to each wafer, which intuitively reflects the defects of the wafer. Therefore, analysis of the wafer map provides a means to improve the quality of the wafer test process.

In the early days, because of the simple wafer process and low production quantities, the analysis of wafer maps was conducted manually, mainly depending on the experience and skills of test engineers. In recent years, with the development of the IC industry, the wafer process and production amount have become complex and massive, and manual analysis has become infeasible.

Recently, deep learning has been used in the wafer test [2,3]. In particular, deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs), as one of the most advanced machine learning methods, have been used in wafer map defect recognition [4,5]. A wafer map classifier that utilizes a multi-scale depthwise separable convolutional (MDSC) neural network is introduced. This network captures the spatial correlations within each channel through the application of multi-scale convolution [6]. In [7], a CNN model is first trained with expert-labeled wafer maps and then used to perform wafer labeling. To ensure labeling accuracy and reliability, an adaptive ensemble learner, which consists of a series of shallow neural networks, is proposed to filter wafer image samples with potentially unreliable pseudo labels [7]. A composite wafer defect recognition framework is proposed in [8]. It utilizes a multi-view dynamic feature enhancement module and an attention mechanism to recalibrate the features of a basic defect and then recognizes the composite defects caused by the manufacturing process. As a pre-processing step for wafer map defect recognition, a framework is proposed to resize wafer maps and retrieve pattern information based on image hashing [9].

Although significant progress has been achieved, existing CNN-based wafer map analysis approaches face two challenges. First, existing approaches usually require thousands of wafer samples for training in order to achieve high defect detection accuracy. However, for most actual IC products, there are only hundreds of wafers per product in mass production. According to the TSMC 2024 Annual Report [10], on average, about 1000 wafers were produced for each product. The manufactured wafers were subsequently tested at the test factory, with corresponding wafer maps generated. It should be noted that the ownership of these wafer maps resides with individual IC design companies. Additionally, under proper quality control during wafer testing, the number of wafer maps containing defects is typically small. Consequently, acquiring a dataset with a large volume of defective samples poses a challenge for both test factories and design companies. Second, existing approaches require pre-processing of wafer maps, such as cluster removal and outer rim removal [11]. The whole process requires a significant amount of time, and rapid detection on-site is difficult to achieve. To address these challenges, we carry out research considering defect features, CNN architecture, and practical constraints and make the following contributions.

- An efficient detection method for wafer-test-induced defects is proposed based on inductive transfer learning [12]. The essence of defect detection is to identify visual patterns associated with distinct failure modes from wafer maps. Therefore, the proposed method exploits the visual feature extraction capability of a pre-trained CNN model and uses hundreds of wafer map data points for fine-tuning to achieve high detection accuracy. The method provides an efficient solution that meets the wafer test requirements and demonstrates a practical application of transfer learning.

- After visualizing and evaluating the impact of the different layers of a CNN model on the detection method, a model development flow is proposed. It progressively prunes the pre-trained model from the deep layers to the shallow layers in order to reduce computation complexity, memory storage, and detection time, enabling on-site fast detection.

- The detection method is evaluated on several pre-trained CNN models and real wafer map data. The results show that the detection accuracy is as high as 100% for test-induced defects on the validation set, while the model size can be reduced by 10.2% and the number of computational operations can be reduced by 83.7% compared to the original models. The decision-making process is interpreted by model visualization.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Wafer Test Process and Defect

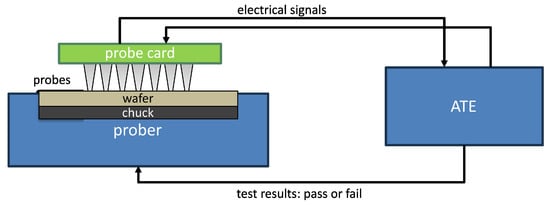

The wafer-level test mainly performs electrical parameter testing, functional testing, performance testing, and process defect detection. The hardware equipment for the wafer test mainly includes the ATE, prober, and probe card, as shown in Figure 1. During the wafer test process, the wafer is positioned on the chuck in the prober. The wafer is vacuum-secured onto the chuck and transported synchronously with the chuck’s movement, enabling comprehensive testing of the entire wafer. The electrical signals generated by the ATE travel through the probe card and are transmitted to the pads on the chips, enabling testing of electrical performance parameters and functional verification. The ATE evaluates the electrical signals generated by the chips and transmits the test results, namely, the pass or fail signals, to the prober. Based on these signals, the prober generates a wafer map that includes pass and fail information.

Figure 1.

CP test diagram.

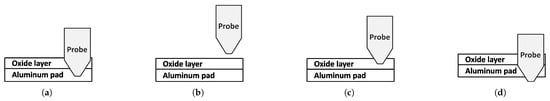

Although the above test configuration is used to detect defects caused by the fabrication process, improper configuration of the test equipment could also introduce false-positive or physical defects [11]. Figure 2 illustrates the positional relationship between probes and pads under various conditions, as well as potential scenarios that may induce defects during the wafer test. Under normal testing conditions, the probes of the probe card must penetrate the oxide layer to reach the pads and establish a connection between the wafer and the probe card, as shown in Figure 2a.

Figure 2.

Examples of wafer-test-induced defects. (a) Probe connects pad properly. (b) Probe does not touch wafer. (c) Probe does not penetrate oxide layer. (d) Probe penetrates pad.

Figure 2b–d show three possible improper scenarios. Several factors could cause the three scenarios. If the settings of the overdrive parameters for the probes are incorrect during testing, the probe tips may not contact the pads, resulting in an open-circuit test outcome (false positive), as shown in Figure 2b,c. A more severe issue is that the probes penetrate the pads (physical defect) and cause a short-circuit test outcome, as shown in Figure 2d. As the wafer test proceeds, the dimensions of the probe tips can change. The rough tips of the probes may not be able to penetrate the oxide layer to contact the pads, as shown in Figure 2c, while excessively small probe tips increase the probability of cracking of the pads, as shown in Figure 2d. Furthermore, prolonged testing can lead to contamination of the probe tips with oxides, which impedes contact between the probes and pads, resulting in an open-circuit test result, as shown in Figure 2c. Finally, if the wafer is not perfectly adsorbed on the chuck or if the chuck and probe card are not aligned in parallel, any of the three scenarios depicted in Figure 2b–d may also occur.

All of the above factors can contribute to test failures or the formation of physical chip defects, potentially resulting in misclassification of functional chips as defective or even causing physical damage to the chips. In this paper, we define test failures and physical defects caused by testing as test-induced defects.

In practical scenarios, test engineers are required to determine whether chip failures are attributable to anomalies in the testing process and to verify whether such failures can induce irreparable damage to the chips, such as burnout or pad cracks. On the one hand, this practice can prevent yield losses and cost escalation resulting from an abnormal wafer test. Anomalies during the wafer test can lead to inaccurate assessment of chip quality, causing resource waste and increased production costs. Through accurate identification and mitigation of these issues, overall production efficiency can be enhanced. On the other hand, chips with defects incurred during wafer testing may exhibit exacerbated problems after packaging processes, particularly when combined with the effects of wire bonding. The additional stress imposed during packaging can potentially amplify pre-existing defects, leading to a higher number of defective products.

Therefore, it is crucial to monitor and promptly detect test-induced defects during the wafer test stage. This helps ensure the quality of the final products, reduce waste, and improve the overall efficiency of the testing process.

2.2. Related Work

The identification and classification of defect patterns in wafer maps have long been critical to enhancing manufacturing yield and root-cause analysis, with research evolving from traditional feature engineering to advanced deep learning approaches. Early studies focused on handcrafted features and statistical methods. Jeong et al. [2] introduced spatial correlograms combined with dynamic time warping for automated recognition of defect patterns, leveraging spatial dependencies to distinguish failure modes. Wu et al. [3] further advanced this by developing a framework for large-scale wafer map failure pattern recognition and similarity ranking, addressing scalability challenges in high-volume manufacturing data. Piao et al. [13] employed radon-transform-based features with a decision tree ensemble, demonstrating improved robustness to geometric variations in defect patterns. Pan et al. [14] extended this domain by introducing wafer-level adaptive testing based on a dual-predictor collaborative decision framework, bridging defect recognition with proactive testing strategies to improve manufacturing efficiency.

The rise of deep learning revolutionized this field, driven by the need to handle complex, mixed-type defects and reduce the reliance on manual feature engineering. Ishida et al. [15] presented a deep learning-based framework for wafer map failure pattern recognition, emphasizing noise reduction through data augmentation to address limited labeled data. The challenge was further tackled by Wang et al. [16] with AdaBalGAN, a generative adversarial network that synthesizes rare defect patterns. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have emerged as the cornerstone. Wang and Chen [17] applied CNNs with polar coordinate transformation to standardize wafer geometries, while Nakazawa and Kulkarni [18] combined CNN-based classification with image retrieval, using synthetic wafer maps to achieve high accuracy and efficient pattern matching. Wen et al. [4] extended CNNs to semiconductor surface defect inspection, demonstrating their versatility beyond bin maps. Fan et al. [7] advanced this by proposing a self-assured deep learning framework that operates with minimum pre-labeled data, addressing the practical constraint of limited annotated samples in industrial settings through uncertainty quantification and active learning strategies.

Addressing mixed-type defects, where multiple failure patterns coexist, became a key focus. Kyeong and Kim [19] and Wang et al. [20] introduced CNNs and deformable convolutional networks (DCNs), respectively, to handle irregular, overlapping defect shapes without manual pre-processing. Wei et al. [5] further enhanced this with multifaceted dynamic convolution, adapting to diverse defect morphologies. Luo et al. [8] expanded this line of research with a composite defect recognition framework, integrating multi-view dynamic feature enhancement with class-specific classifiers to capture complex spatial relationships across different defect categories.

To overcome limitations of single-modality approaches, hybrid methods integrated handcrafted and deep features. Kang [21] proposed a stacking ensemble classifier that combined geometric and statistical descriptors with CNN features, achieving superior accuracy in synthetic and real datasets. Kim et al. [22] introduced Bin2Vec, a neural network-based coloring scheme that improved visualization interpretability while enabling consistent bad wafer classification. Piao and Jin [9] explored image hashing for wafer map failure pattern recognition, offering a lightweight alternative for efficient pattern matching and retrieval in large-scale databases, complementing deep learning-based methods with faster inference speeds.

Although significant progress has been achieved, existing machine learning-based defect detection methods require either a complex model and a large number of training samples or data pre-processing. This work focuses on wafer-test-induced defect detection and aims to provide a practical and efficient solution.

3. Methodology

3.1. Motivation

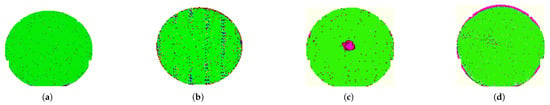

Figure 3 presents a defect-free wafer map (denoted as “Good”), a defective wafer map resulting from wafer test issues (CPF: Chip Probing Failure), and two typical defective wafer maps (Local and Edge) caused by fabrication processes. It can be observed that defective wafer maps induced by testing and fabrication processes exhibit distinct characteristics. This distinctiveness makes the detection and identification of test-induced defects feasible.

Figure 3.

Wafer map samples. (a) Good. (b) CPF. (c) Local. (d) Edge.

As mentioned above, the wafer-test-induced defects are mainly due to the improper setting of the test conditions. Therefore, wafer-test-induced defects should be detected as early as possible so that improper settings can be corrected and the number of defective wafers can be reduced. In this way, the loss of final products can be minimized. Therefore, a fast and accurate detection method is required for wafer-test-induced defects on-site. In addition, because of differences in testing software and hardware, the features of wafer-test-induced defects may vary on wafer maps. Therefore, the detection method should also be able to adapt to real test conditions.

To meet the requirements, we propose an efficient and practical detection method, as follows: (1) the method takes advantage of the transfer learning technique [12], transfers knowledge from the general object detection field to wafer test defect detection, and requires only a small number of samples for fast adaptation; and (2) the method customizes the CNN structure by network pruning [23] to reduce computational workload and enable fast detection on-site.

3.2. Wafer Test Defect Detection Based on Transfer Learning

The target domain and the learning task for the test-induced defect detection problem can be defined as follows. The target domain is , where is a feature space of all feature vectors of wafer maps and is a marginal probability distribution of a feature vector . uniquely represents a wafer map i. The learning task is , where is a label space which is true or false, indicating whether there is a defect or not, and the function is used to predict the corresponding label for a wafer map . Specifically, given , the task is to learn from training samples . However, as mentioned earlier, there are only hundreds of wafers in mass production and thus the size of training samples is limited. As a result, the prediction accuracy of is hard to guarantee if it is trained directly on the limited training samples.

However, we know that the fundamental process of the targeted problem of detecting test-induced defects from wafer maps is equivalent to a series of image processing operations. Classic CNNs trained on a large dataset such as ImageNet have achieved remarkable capability in image feature extraction, classification, and recognition. The image classification task on ImageNet aims to classify objects from more than 5000 categories that are the meaningful concepts in WordNet. The domain contains millions of images and their marginal probability distribution. Certainly, the domain is different from our target domain . In fact, is significantly larger than because ImageNet’s scale and diversity are much greater than the available wafer map set and does not contain . In addition, is different from . In this case, the CNN model obtained from and cannot be used directly in our domain and task.

However, the intuition is that the CNN model’s capability learned from ImageNet could be transferred to our task, because the defective wafer maps demonstrate certain visual features such as colors, edges, lines, positions, etc. This motivates us to exploit the inductive transfer learning technique [12]. Inductive transfer learning can help with the learning of the predictive function in the target domain using knowledge in the source domain and the task and , where . Only a few labeled samples in are required as training data to induce . This meets the requirement of test-induced defect detection problem. Next, we show how to transfer the knowledge.

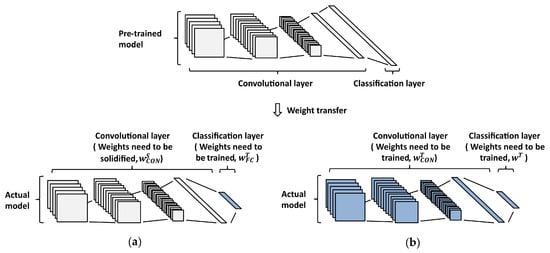

A typical CNN model contains two types of layers, the convolutional layer (CON) and fully connected layer (FC). The CON layers extract features, and the FC layers make the classification decision. The trained CNN model could be simply represented as

where are the trained parameters of the CON layers and are the trained parameters of the FC layers. In inductive transfer learning, one way of transferring knowledge is to use the CON layers obtained from the source domain in the defect detection task as follows:

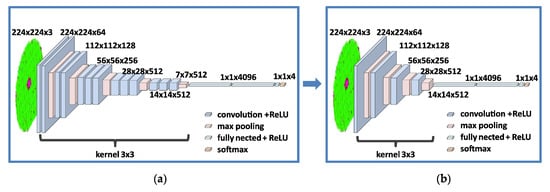

where the parameters of CON obtained in the source domain are reused because we want to exploit the learned visual feature extraction capability. Figure 4a illustrates inductive transfer learning without the fine-tuning of the convolutional layer. The defective wafer map samples are then used to train the parameters of the FC layers. The FC layers’ parameters are not reused here because the two tasks and are different.

Figure 4.

Model generation based on inductive transfer learning. The blue color indicates the parts finely adjusted. (a) Inductive transfer learning without the fine-tuning of the convolutional layer. (b) Inductive transfer learning with the fine-tuning of the convolutional layer.

The loss function used to train is the following:

where N is the number of training wafer maps, K is the number of categories of defective wafer map, and v represents the output of the CON layers. The Batch-SGD (Batch Stochastic Gradient Descent) training algorithm is used.

There are also some cases where the feature extraction capability learned from the source domain is not enough because the difference between the source and target domains is large. For the defect detection problem in such a specialized field, the description of wafer maps and the corresponding defect labels may not be properly incorporated into the source domain, e.g., the ImageNet database used as the source domain in this work does not contain any samples of wafer maps. The domain difference needs to be reduced to further improve the prediction accuracy of . To do so, the parameters of CON obtained in the source domain are re-tuned during the training.

where the new parameters are obtained based on the parameters transferred from the source domain and the specific parameters from the target domain. represents the new weight parameters of the whole network, including the convolution layers and the fully connected layers, as shown in Figure 4b. In this case, the loss function used in the training is

where

3.3. Model Development Flow

The model generated by transfer learning inherits the good visual feature extraction capability and achieves high detection accuracy by fine-tuning. However, the pre-trained model trained for general visual object classification usually contains a large number of parameters and requires high computing power and storage space. To improve detection efficiency and reduce overhead, the detection method is desired to have low computing requirement, low memory usage, and high detection accuracy.

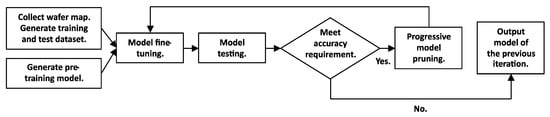

To achieve this goal, we propose a model development flow based on progressive pruning [23], as shown in Figure 5. The wafer map dataset and the pre-trained CNN model are prepared first. Secondly, the actual model is generated by transfer learning and is fine-tuned with the training dataset. The test dataset is then inputted to evaluate the accuracy of the model. If the accuracy meets the requirement, the model is pruned progressively. Afterwards, the model goes back to the fine-tuning stage. The iterative process continues until the model cannot be further pruned under the accuracy constraint. In the next, we introduce the progressive pruning method used in the flow.

Figure 5.

Development flow.

The progressive pruning method is developed considering the structure characteristics of CNN models. In general, the receptive field of shallow layers is relatively small, and the overlap area of the receptive fields is also relatively small, so it can ensure that the network extracts more detailed features. Therefore, the shallow layers of the CNN extract features that include fine-grained information, such as image color, texture, edges, etc. As the receptive fields increase, the deep layers extract coarse-grained information about the overall image. As the number of CNN layers increases, the extracted features move from the details to the whole and from simple to complex.

In general, the more layers a CNN has, the stronger the capability of the CNN model to extract and represent features. However, deeper networks require more training data to ensure accuracy. In addition, the more layers a CNN has, the greater its computational complexity and latency. For test-induced defect detection, the amount of training data is limited, and the defect patterns are relatively simple compared to general object detection. Also, the overall information extracted by the deeper layers in the pre-trained model is not strongly related to the test-induced defect detection task due to the across-domain transferring. An increase in the number of layers in the CNN does not necessarily lead to better model learning performance. Trimming the deeper CON layers of neural networks can not only greatly reduce computational complexity but also achieve model testing accuracy comparable to or even better than deep convolutional neural networks. As a result, it is important to keep the shallow layers when using transfer learning to transfer model parameters trained on the ImageNet dataset to the test-induced defect detection task. Therefore, in the proposed method, the deeper CON layers are progressively pruned. The pruning starts from the deepest CON layer and the associated activation function. After re-tuning, if the model accuracy meets the requirement, then the layer next to the deepest layer is removed. The process proceeds from deep layers to shallow layers until the model accuracy requirement is not met.

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Experiment Setup

To evaluate the proposed detection method, we carried out a set of experiments. In the first part, we evaluated the effect of transfer learning on the detection method with limited training data. In the second part, we evaluated the effect of progressive pruning of the model on the detection method. The experiments were carried out on a computer with an NVIDIA 3060 GPU. We set the batch size of training to 32, the epoch to 100, and the learning rate to 0.001. The pre-trained VGG16, ResNet18, and MobileNetV2 networks on ImageNet dataset were used for transfer learning. In addition, to evaluate the real-time processing performance of the detection method, we also deployed the CNN models used in the detection method on an FPGA accelerator.

Publicly available wafer map datasets, such as WM-811K, do not contain test-induced defects. Therefore, in the experiment, 1026 wafer maps were obtained from actual production, in which several digital ICs were tested using a V93000 test system. The size of the dataset represents a typical amount of wafers generated for an IC product [10]. The dataset was randomly partitioned into a training dataset with 739 wafer maps and a validation dataset with 287 wafer maps. In the training set, there were 277 good wafer maps, 150 CPF wafer maps, 150 local wafer maps, and 162 edge wafer maps. In the validation set, there were 125 good wafer maps, 51 CPF wafer maps, 51 local wafer maps, and 60 edge wafer maps. To evaluate the robustness of the method, the dataset partition was performed three times at random while maintaining consistent sizes for both the training and validation sets, as well as keeping the number of wafer maps per category unchanged, resulting in three partition schemes of the training and validation sets.

4.2. Evaluation Metric

In the experiment, a confusion matrix was employed to show the relationship between actual labels and predicted categories. Based on the confusion matrix, several evaluation metrics were used, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score.

Accuracy represents the overall correctness of the detection method, defined as the number of correct predictions divided by the total number of samples. Precision denotes the fraction of instances identified as positive that are truly positive. Recall quantifies the proportion of correctly identified positive instances relative to all actual positive cases. Higher recall signifies a model’s enhanced ability to detect positive instances, albeit potentially at the cost of increased false positives. To balance recall and precision in the prediction process, the F1 score was also used as a weighted harmonic mean in the experiment.

4.3. Detection Accuracy Evaluation

To evaluate the accuracy of the proposed detection method, we compared it to two methods for the defect detection task using the training and validation datasets. One method included training a VGG16 model with the training data from scratch, called VGG16-noTL. The other used the classical support vector machine (SVM) method [24]. Also, the proposed method was implemented in two versions, one without fine-tuning of the CON layers (VGG16-TL-noFT) and one with fine-tuning of the CON layers (VGG16-TL-FT).

The results are shown in Table 1, where the VGG16 network is used. From the results, we can make the following observations. First, the proposed detection method without fine-tuning the CON layers achieves higher detection accuracy than the two traditional machine learning methods in all four accuracy metrics, up to a 17.4% improvement. Second, with fine-tuning of the CON layers, the detection accuracy is further increased to 100% on the validation set.

Table 1.

Detection accuracy comparison of different methods.

Table 2 shows the confusion matrix of the detection method in three dataset partition schemes. We can see that in all three schemes, the detection method achieves 100% detection accuracy for the CFP category on the validation set. This result demonstrates the stability of the proposed method.

Table 2.

Confusion matrix of the detection method under three dataset partition schemes.

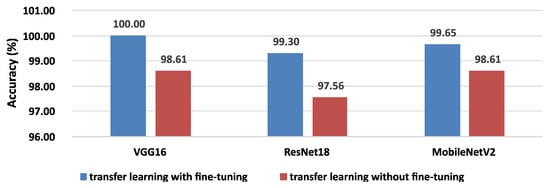

We also make similar observations on the ResNet18 and MobileNetV2 networks. The results are shown in Figure 6. With limited wafer map samples, the proposed method improves detection accuracy by leveraging the knowledge from the general object detection field to the wafer test defect detection for fast adaptation.

Figure 6.

Detection accuracy comparison with and without fine-tuning of the convolutional layers on different models.

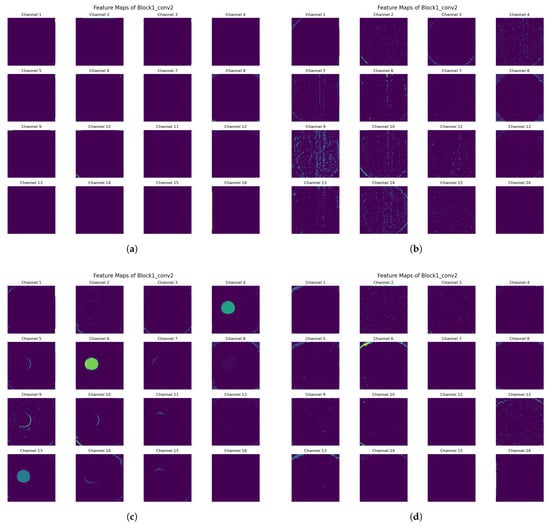

Furthermore, we visualize the corresponding feature maps of the model to provide insight into how the neural network model works during defect detection. The first 16 channels of the second convolutional layer are illustrated in Figure 7, where Figure 7a–d display extracted features corresponding to the wafer maps shown in Figure 3, respectively. Taking the “CPF” category as an example, it can be observed that the linear pattern present in the wafer map is effectively extracted and represented in the feature maps. Therefore, the trained model performs as expected.

Figure 7.

The extracted features of the wafer maps. (a) Good. (b) CPF. (c) Local. (d) Edge.

4.4. Result of Progressive Pruning

In this part of the experiment, we used VGG16 to evaluate the progressive pruning method. Table 3 shows the structure of the model.

Table 3.

VGG16 model structure.

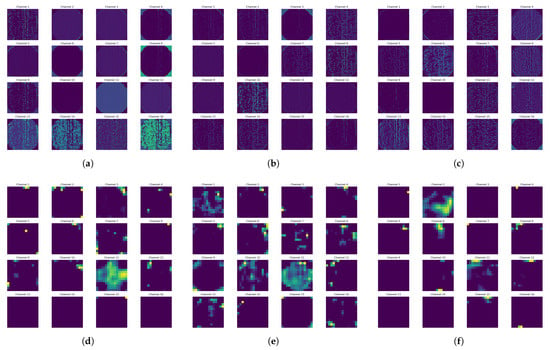

We first demonstrate the impact of different convolutional layers on the accuracy of the detection method. Figure 8 presents the feature maps extracted by layers 0, 1, 3, 14, 15, and 16 of the original VGG16 model given the input wafer map of the category CPF. It can be observed that the shallow layers 0, 1, and 3 capture the fine-grained edge information of the CPF, whereas the deep layers 14, 15, and 16 capture the coarse-gained features, which do not contribute to the test-induced defect detection.

Figure 8.

Feature maps extracted by different convolutional layers in the original VGG16 model. (a) Hidden layer 0. (b) Hidden layer 1. (c) Hidden layer 2. (d) Hidden layer 14. (e) Hidden layer 15. (f) Hidden layer 16.

Table 4 shows the detection accuracy of the model after removing shallow layers 1~3 and deep layers 15~17, respectively. We can see that when the deep layers 15~17 are removed, the accuracy remains 100%. In contrast, when the shallow layers are removed, the model’s detection accuracy decreases. This result is consistent with the above feature map visualization. Thus, the model development flow is well justified and represents a meaningful structural simplification method.

Table 4.

Detection accuracy comparison between removing shallow layers and deep layers of VGG16 model.

We obtain six models as shown in Table 5, pruning from the original VGG16 model (labeled model no. 0) following the proposed progressive pruning method. For example, model no. 1 is obtained by pruning four deep hidden layers, 14~17. In addition, to maintain feature extraction capability, for convolutional layers with the same number of input channels, at least one layer is kept during the pruning process. In addition to hidden layers, the classification layers are also pruned. Model no. 6 is obtained by pruning both the hidden layers and the classification layers. From the experimental results, it can be seen that before model no. 6, as more layers are removed, both the model size (the number of parameters) and the computation workload (floating operations, FLOPs) are reduced, and the detection accuracy remains. Specifically, depending on the size, pruning a convolutional layer will significantly reduce computational complexity, where each weight parameter is involved in multiple multiplications and additions. For example, from model no. 1 to model no. 2, pruning layers 11~12 reduces 4.7 M parameters and 3.7 G computational operations; from model no. 2 to model no. 3, pruning layers 7~8 reduces 1.2 M parameters and 3.7 G operations. From model no. 6, the detection accuracy starts to decline. This is because the classification layers have a more significant impact on the model accuracy. If a smaller model size is preferred, the progressive pruning process can continue, at the cost of accuracy degradation. In the IC testing scenario, ideally no defective chip is allowed to pass the test to ensure a high yield. Therefore, model no. 5 is taken as a promising result. Compared to the original VGG16 model, the size and computation workload of model no. 5 are reduced by 10.2% and 83.7%, respectively. The models before and after pruning are shown in Figure 9.

Table 5.

Results of progressive pruning of VGG16 model.

Figure 9.

VGG16 model before and after progressive pruning. (a) VGG16 model before progressive pruning. (b) VGG16 model after progressive pruning.

4.5. Hardware Deployment

Our ultimate goal is to achieve real-time online defect detection in the wafer test pipeline. Therefore, we also tried to deploy the proposed detection method on a CNN accelerator. Our previous work designs an FPGA-based lightweight CNN accelerator [25]. The accelerator contains 256 processing elements (PEs), and each PE comprises nine multipliers and an adder tree. It supports multi-level parallelism, such as kernel level, input channel level, and output channel level. We map the VGG16 model no. 5 onto the accelerator in an Xilinx Virtex-7 XC7V690t FPGA. The accelerator uses 308,449 LUTs, 278,926 FFs, 941.5 BRAM blocks, and 2160 DSP blocks. The results show that the accelerator works at 150 MHz and provides a processing speed of 61.7 FPS (16.2 ms per frame) at a power consumption of 11.35 W. These results meet the requirements in the wafer test scenario, enabling real-time defect detection. With such a capability, the defects caused by improper wafer test settings can be found earlier, and the related loss can be significantly reduced.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we propose an efficient detection method for wafer-test-induced defects. By analyzing the characteristics of the task, we exploit inductive transfer learning and a development flow to achieve a high-accuracy and lightweight detection method that only requires a small amount of training data. The method is simple, fast, and matched to the actual wafer test process.

Considering the inherent real-time operational characteristics of wafer testing and production processes, alongside the anticipated continuous improvement in wafer yield rates, the acquisition of defective wafer samples remains technically challenging. Consequently, future research endeavors could leverage few-shot learning or self-supervised learning paradigms to enhance the generalization capabilities of the defect detection method across diverse wafer testing scenarios.

Author Contributions

Z.W., Q.L., G.C. and W.S. contributed to the study conception and design. Z.W., W.S. and X.W. were responsible for material preparation and analysis. L.Z. and Y.Z. collected the data. Q.L. supervised the research and guided the writing of the paper. Z.W. authored the first draft, and all authors provided feedback on subsequent versions. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant U21B2031.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research does not involve human participants or animals.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to the data belonging to Shanghai Eastsoft Microelectronics Co., Ltd.

Conflicts of Interest

Author W.S., X.W., L.Z. and Y.Z. are employed by the company (Shanghai Eastsoft Microelectronics Co., Ltd.). ALL the authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Uzsoy, R.; Lee, C.Y.; Martin-vega, L.A. A review of production planning and scheduling models in the semiconductor industry part I: System characteristics, performance evaluation and production planning. IIE Trans. 1992, 24, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.-S.; Kim, S.-J.; Jeong, M.K. Automatic identification of defect patterns in semiconductor wafer maps using spatial correlogram and dynamic time warping. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2008, 21, 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-J.; Jang, J.-S.R.; Chen, J.-L. Wafer map failure pattern recognition and similarity ranking for large-scale data sets. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2014, 28, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, G.; Gao, Z.; Cai, Q.; Wang, Y.; Mei, S. A novel method based on deep convolutional neural networks for wafer semiconductor surface defect inspection. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2020, 69, 9668–9680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Wang, H. Mixed-type wafer defect pattern recognition framework based on multifaceted dynamic convolution. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Pu, H.; Shao, K. Wafer map defect pattern classification based on multi-scale depthwise separable convolution. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Symposium of Electronics Design Automation (ISEDA), Nanjing, China, 8–11 May 2023; pp. 204–208. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, S.-K.S.; Tsai, D.-M.; Shih, Y.-F. Self-assured deep learning with minimum pre-labeled data for wafer pattern classification. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2023, 36, 404–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Wang, H. Composite wafer defect recognition framework based on multiview dynamic feature enhancement with class-specific classifier. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, M.; Jin, C.H. Analysis of image hashing in wafer map failure pattern recognition. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2023, 36, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC). TSMC 2024 Annual Report. 2025. Available online: https://investor.tsmc.com/sites/ir/annual-report/2024/2024%20Annual%20Report-E.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Cheng, K.C.C.; Chen, L.L.Y.; Li, J.W.; Li, K.S.M.; Tsai, N.C.Y.; Wang, S.J.; Huang, A.Y.A.; Chou, L.; Lee, C.S.; Chen, J.E.; et al. Machine learning-based detection method for wafer test induced defects. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2021, 34, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, F.; Qi, Z.; Duan, K.; Xi, D.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Xiong, H.; He, Q. A comprehensive survey on transfer learning. Proc. IEEE 2020, 109, 43–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, M.; Jin, C.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Byun, J.-Y. Decision tree ensemble-based wafer map failure pattern recognition based on radon transform-based features. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2018, 31, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Liang, H.; Li, J.; Qu, J.; Huang, Z.; Yi, M.; Lu, Y. Wafer-level adaptive testing based on dual-predictor collaborative decision. J. Electron. Test 2024, 40, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, T.; Nitta, I.; Fukuda, D.; Kanazawa, Y. Deep learning-based wafer-map failure pattern recognition framework. In Proceedings of the 20th International Symposium on Quality Electronic Design (ISQED), Santa Clara, CA, USA, 6–7 March 2019; pp. 291–297. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Chien, W.-T.K. AdaBalGAN: An improved generative adversarial network with imbalanced learning for wafer defective pattern recognition. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2019, 32, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Chen, N. Defect pattern recognition on wafers using convolutional neural networks. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2020, 36, 1245–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, T.; Kulkarni, D.V. Wafer map defect pattern classification and image retrieval using convolutional neural network. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2018, 31, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyeong, K.; Kim, H. Classification of mixed-type defect patterns in wafer bin maps using convolutional neural networks. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2018, 31, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, C.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, X. Deformable convolutional networks for efficient mixed-type wafer defect pattern recognition. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2020, 33, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Kang, S. A stacking ensemble classifier with handcrafted and convolutional features for wafer map pattern classification. Comput. Ind. 2021, 129, 103450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, H.; Park, J.; Mo, K.; Kang, P. Bin2Vec: A better wafer bin map coloring scheme for comprehensible visualization and effective bad wafer classification. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Sun, M.; Zhou, T.; Huang, G.; Darrell, T. Rethinking the value of network pruning. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.05270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vapnik, V. The support vector method for estimating indicator functions & The support vector method for estimating real-valued functions. In Statistical Learning Theory; Wiley Publishing House: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 401–492. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Yan, S.; Cheung, R.C.C. An efficient FPGA-based depthwise separable convolutional neural network accelerator with hardware pruning. ACM Trans. Reconfigurable Technol. Syst. 2024, 17, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).