Abstract

This study provides a novel approach to the field of prognostics and health management (PHM) in nanotechnology: multi-agent systems integrated with ontology-based knowledge representation and Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL). This framework has agents acting in a network-like manner, where every agent investigates a particular subject of nanotechnology design and lifecycle management for an interdependent and multifaceted problem-solving approach. Ontologies give the framework a semantic dimension, which allows for the precise and context-dependent interpretation of data. These permit observations attuned towards understanding the behaviors of nanomaterials, performance limitations, and failure mechanisms. On the other hand, having a DRL-integrated module permits agents to provide dynamic adaptation to changing operational contexts, datasets, and user scenarios while continuously calibrating their decisions for better accuracy and efficiency. Preliminary evaluations based on expert-reviewed test cases demonstrated a 95% task success rate and a decision-making accuracy of 96%, indicating the system’s strong potential in handling complex nanotechnology scenarios. These results show good robustness and adaptability to certain PHM problems, such as predictive maintenance of nanodevices, lifespan optimization of nanomaterials, and risk assessment in complex environments. This study introduces a novel integration of Multi-Agent Systems (MAS), ontology-driven reasoning, and DRL, enabling dynamic cross-ontology collaboration and online learning capabilities. These features allow the system to adapt to evolving user needs and heterogeneous knowledge domains in nanotechnology.

1. Introduction

Nanotechnology has emerged as a fundamental aspect of scientific and engineering progress because the unique properties of materials displayed at the nanoscale significantly differ from those of their larger forms [1]. These distinct attributes have driven nanotechnology to become a forefront area of innovation, with uses across various sectors like electronics, energy systems, catalysis, and biomedicine [2,3]. Although it holds great potential, creating new nanomaterials is still challenging. This challenge stems from needing to handle and examine vast quantities of intricate and frequently unstructured data [4].

One of the key components in semantic modeling is the use of ontology, defined as a formal, explicit specification of a shared conceptualization. In this context, ontology serves as a structured knowledge model that describes domain-specific concepts and their relationships in a machine-readable format [5]. NPO offers an organized structure for classifying nanomaterials according to characteristics like particle size, shape, and chemical bonds. These frameworks boost researchers’ capacity to access and combine various datasets, enhancing the retrieval and distribution of nanomaterial characteristics across multiple platforms.

Although ontologies offer significant advantages for structuring knowledge, their use in real-world decision-making is constrained by the difficulties of querying them. The connections among concepts in these frameworks are intricate, posing challenges in effectively managing complex inquiries from researchers. To address these limitations, Semantic Web technologies have been suggested to enhance the accessibility and interoperability of data. Technologies like Resource Description Framework (RDF) and SPARQL (SPARQL Protocol and RDF Query Language) facilitate the merging of various datasets, leading to a deeper comprehension of the relationships between information fields [6]. These instruments enable sophisticated querying abilities and improve decision-making processes, especially in the design and forecasting of nanomaterials. Nonetheless, the computational requirements and the necessary expertise for implementation still present difficulties.

In the context of nanotechnology-based PHM, these challenges, such as the management of massive, heterogeneous datasets and the complexity of semantic querying across domains, are not abstract or isolated difficulties. They are, in fact, direct consequences of how current technologies are designed and interact. Most existing Multi-Agent Systems (MAS) have been built around static communication protocols and single-domain ontologies, which makes them efficient only within narrowly defined boundaries. When new materials, processes, or application contexts are introduced, these systems struggle to assimilate and reason over data that do not fit their predefined schemas. Similarly, ontology frameworks in use today seldom support dynamic updating or self-adaptive inference; once established, their semantic models tend to remain rigid. As a result, integrating information from multiple domains or responding to emerging data patterns requires extensive manual intervention. These technological constraints naturally translate into the broader challenges of scalability, interoperability, and adaptive decision-making that we highlight as central barriers in nanotechnology PHM. By exposing this cause-and-effect relationship, we aim to clarify that the obstacles faced by the field are not merely conceptual but deeply rooted in the limitations of current system architectures.

An effective strategy for tackling these challenges is the integration of MAS, which merges the reasoning capabilities of ontologies with the adaptability of intelligent agents. These systems employ separate agents, with each one focused on exploring a particular ontology, to simultaneously gather and integrate knowledge from various sources [7]. Utilizing MAS, systems can deliver context-sensitive answers to inquiries concerning nanomaterial design and health management, greatly enhancing the effectiveness of data retrieval and integration. Additionally, by utilizing Semantic Web technologies, these agents can link datasets more efficiently, thereby increasing their effectiveness [8].

The suggested study centers on creating a MAS-based framework that incorporates Semantic Web technologies to enhance PHM in nanotechnology. This system features specialized agents that correspond with various ontologies, facilitating improved query processing and knowledge extraction. For instance, one agent could concentrate on obtaining structural information from the NPO, while another is dedicated to examining ontologies associated with material deterioration. The partnership among these agents guarantees a thorough grasp of material characteristics and their design capabilities [9].

The system is structured to handle inquiries related to PHM in nanotechnology, utilizing ontology-driven reasoning to broaden or narrow search terms into more generalized or specific ideas. This method allows researchers to improve and optimize their material design processes with increased accuracy [10,11]. Moreover, the system includes reinforcement learning algorithms that enable it to progressively enhance its responses by assessing the effectiveness of rules based on ontological data. The system consistently improves its performance over time by incentivizing rules that produce the most precise and pertinent outcomes.

This adaptive learning approach resonates with broader developments in recent reinforcement learning and neural control research. Beyond the scope of nanotechnology-based PHM, advances in adaptive neural control have further demonstrated the potential of intelligent, learning-based frameworks. For instance, Dehua et al. [12] proposed an adaptive critic design for safety-optimal fault-tolerant control of unknown nonlinear systems with asymmetric constrained input, showing how neural critic architectures can integrate safety constraints into the learning process. Similarly, Qin et al. [13] introduced a critic learning–based safe optimal control strategy for nonlinear systems with asymmetric input constraints and unmatched disturbances. In a game-theoretic context, Dong et al. [14] developed a barrier-critic disturbance approximate optimal control framework for nonzero-sum differential games with state constraints. Moreover, adaptive critical learning has been applied to event-triggered control in nonlinear systems [15], improving efficiency while preserving stability and robustness. Although these studies mainly stem from control engineering and robotics, they share the same conceptual foundation as our work, the integration of adaptive learning and structured, knowledge-informed reasoning. By situating our ontology-guided DRL framework within this broader evolution of intelligent adaptive systems, we provide a wider theoretical context and reinforce the novelty of our contribution to PHM for nanotechnology.

The MAS framework guarantees that every agent functions within a designated knowledge domain, allowing for concentrated and effective data processing. Agents work together to generate unified, semantically enhanced results, thus automating intricate retrieval and synthesis activities. This automation reduces manual effort, accelerates decision-making, and improves the reliability of PHM applications in nanotechnology.

By integrating ontologies, Semantic Web technologies, and MAS, this research aims to establish a robust framework for addressing the challenges associated with PHM in nanotechnology. The system streamlines the retrieval and application of nanomaterial knowledge, reduces reliance on trial-and-error methods, and fosters innovation in the field [11]. Ultimately, this approach will facilitate the development of advanced materials, optimize their functionality, and ensure greater precision in health and performance management across a wide range of applications.

Ontologies play a central role in enabling semantic interoperability across health information systems by standardizing domain vocabularies and supporting structured knowledge inference. provide a foundational framework for the design and application of ontologies in intelligent systems, emphasizing how formal semantic models enhance machine interpretability and decision support across domains [16].

This study demonstrates how ontologies contribute to semantic alignment and interoperability in electronic health data, improving data integration and clinical reasoning [17]. Building upon these principles, our framework integrates ontological reasoning into a multi-agent system and extends it with reinforcement learning mechanisms. This combination enables context-aware, adaptive decision-making in biomedical environments, thus bridging the gap between static semantic models and dynamic, learning-based systems.

While previous studies have explored the integration of MAS with ontologies in materials science and nano-informatics, they often operate within single-domain knowledge bases and rely on static reasoning mechanisms. Our proposed framework advances this paradigm by enabling agents to perform cross-ontology reasoning, allowing dynamic integration of knowledge from multiple, domain-specific ontologies such as NPO, biomedical, and environmental ontologies. Additionally, we introduce a live DRL module that continuously adapts agent behavior based on real-time performance feedback. This online learning capability allows the system to refine decision-making policies over time, improving context-sensitive responses and enabling adaptive PHM in evolving operational environments. These innovations distinguish our approach from existing ontology-driven MAS architectures and represent a meaningful advancement in semantic interoperability and adaptive learning within nanotechnology applications.

This manuscript presents a novel MAS framework integrated with ontology-based knowledge representation and DRL, specifically designed to advance PHM within the domain of nanotechnology. The proposed system employs semantically driven agents that reason over domain-specific ontologies such as the NPO, enabling precise interpretation of complex nanomaterial data. By embedding a DRL module within the MAS architecture, the system continuously learns and refines its decision-making strategies based on expert-annotated feedback. This hybrid architecture allows for dynamic, adaptive, and context-aware health management solutions that are robust against evolving user needs and heterogeneous data environments. The integration of cross-ontology reasoning and online learning capabilities positions this framework as a significant step forward in intelligent PHM systems for nanotechnology applications.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews related work and key advancements, providing context for the study. Section 3 outlines the methodology used to achieve research objectives. Section 4 describes the system’s design and implementation, while Section 5 presents the results, demonstrating the system’s effectiveness in addressing the identified challenges. Section 6 discusses the findings, focusing on their implications and potential contributions, and Section 7 concludes by summarizing the research contributions and suggesting directions for future work.

Despite growing interest in ontology-driven MAS in fields like materials science and healthcare, current frameworks face important limitations. Most existing MAS implementations rely on static rule sets and operate within narrowly scoped ontologies, which restrict their ability to generalize across knowledge domains. Moreover, they lack adaptive learning mechanisms, making it difficult to refine decision-making as new data or user queries emerge. These gaps are particularly limited in nanotechnology, where interdisciplinary knowledge integration and continuous system evolution are essential. To date, no prior study has successfully combined cross-ontology reasoning with live reinforcement learning in a MAS framework designed for PHM in nanotechnology. This study addresses that gap by proposing a modular, learning-enhanced MAS capable of dynamic query refinement, knowledge integration, and performance self-improvement.

To concretely define the goals of this study and evaluate its outcomes, we propose the following research questions:

- RQ1: How can a MAS integrate with domain-specific ontologies to improve semantic reasoning and knowledge retrieval in nanotechnology-based PHM?

- RQ2: Can incorporating a DRL module help agents adaptively refine decision-making rules in response to dynamic data and evolving queries?

- RQ3: What is the overall effectiveness of the proposed MAS + DRL architecture in improving task success rate, decision accuracy, and adaptive learning over time in realistic PHM scenarios?

These research questions are designed not only to guide the technical development of the MAS + DRL framework but also to advance theoretical understanding and practical implementation in the field of semantic reasoning for nanotechnology. RQ1 contributes to the theoretical exploration of how multi-agent ontological reasoning can support semantic interoperability across heterogeneous domains. RQ2 addresses a practical gap by evaluating the real-world adaptability of reinforcement learning in health-oriented nanotech systems. RQ3 bridges both dimensions by empirically assessing the effectiveness of a hybrid architecture in delivering robust, adaptive solutions, thereby contributing to evolving best practices in intelligent health management and decision-support systems.

Furthermore, to strengthen the conceptual grounding of our study, we explicitly link each of the three research questions (RQ1–RQ3) to specific gaps identified in existing work. RQ1 focuses on the integration of MAS and ontologies, addressing the lack of flexible, cross-domain agent communication found in previous PHM systems. Earlier studies have largely relied on static ontological structures that cannot accommodate new material domains or emergent data relationships, creating a gap in semantic adaptability. RQ2 targets the incorporation of Deep Reinforcement Learning to enhance the adaptive and predictive capabilities of PHM frameworks. This responds to a well-documented shortcoming in current approaches, namely, their limited ability to learn from evolving operational data and feedback loops. Finally, RQ3 examines the overall system effectiveness that results from combining these technologies in a single framework, thus tackling the fragmentation of previous solutions, which often treat ontology reasoning, agent collaboration, and learning-based decision-making as isolated modules. By articulating how each question directly addresses an existing void, we aim to provide a clearer logical bridge between the current state of the art and our proposed research direction.

Despite the growing use of ontologies and intelligent agents in healthcare and materials science, there remains a lack of systems that can reason across heterogeneous knowledge domains while adapting to changing data contexts. Existing MAS are typically limited by static rule sets and single-domain reasoning and rarely incorporate learning mechanisms that improve over time. Likewise, DRL applications in health or engineering operate without semantic awareness, making them less explainable and harder to generalize. Our study addresses this gap by proposing a hybrid MAS framework enhanced with ontology-based reasoning and DRL, specifically designed for nanotechnology-based PHM.

To situate this contribution within the broader research landscape, it is worth noting that while the integration of Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) and ontology-driven systems remains relatively unexplored in the specific context of nanotechnology PHM, related advances in other domains provide valuable insight into the potential of combining symbolic reasoning with learning-based models. In healthcare, for example, recent studies have incorporated ontological structures into reinforcement learning frameworks to guide treatment optimization and improve interpretability in decision policies. Similarly, in smart manufacturing, symbolic reasoning layers have been used to constrain or inform DRL agents, allowing them to learn within semantically grounded design spaces. These efforts demonstrate that embedding domain knowledge into learning algorithms can significantly enhance transparency, efficiency, and generalization qualities that are critically needed in nanotechnology applications, where material behaviors and biological interactions are often uncertain and highly context-dependent. Building on these cross-domain findings, our framework extends the concept of knowledge-augmented learning to PHM for nanotechnology, using ontologies not only as a source of semantic structure but also as an active component in the adaptive reasoning process.

To clarify the scope and impact of this research, the main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- We propose a modular architecture combining MAS, ontologies, and DRL to support adaptive and semantically informed decision-making.

- We introduce a method for cross-ontology reasoning, enabling agents to integrate knowledge from multiple specialized sources (e.g., NPO, biomedical, chemical).

- We design and train a DRL module that refines agent behaviors based on performance feedback from expert-reviewed scenarios.

We demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed system through three realistic use cases and validate its performance using quantitative metrics (TSR, DMA, ALI).

The main objective of this research is to develop a hybrid framework that integrates multi-agent systems (MAS), semantic ontologies, and deep reinforcement learning (DRL) to enable adaptive, knowledge-driven decision-making in nanotechnology applications. Unlike traditional MAS implementations that operate within narrowly scoped ontologies and lack adaptive learning mechanisms, the proposed framework leverages semantic reasoning to support abstraction and generalization across knowledge domains. By combining ontology-based knowledge representation with real-time DRL, the system aims to enhance fault prediction, optimize nanoparticle design, and provide adaptive decision support in dynamic environments.

To better understand the motivation for this integration, it is important to consider the technical roots of the limitations found in existing MAS approaches. The limitations of traditional Multi-Agent Systems (MAS) in nanotechnology-based PHM can be traced to several intertwined technical factors. Most MAS architectures were designed under static assumptions about domain knowledge and agent behavior, meaning that their reasoning models are predefined rather than adaptive. Agents typically communicate through ontology-bound message templates, often based on single-domain taxonomies, which constrain their ability to negotiate meaning or interpret unfamiliar concepts when interacting across domains. Moreover, the absence of feedback mechanisms linking agents’ decisions to updated knowledge representations prevents learning from accumulated experience. As a result, these systems remain reactive rather than proactive, responding to predefined conditions without improving over time. From an implementation perspective, most MAS platforms (e.g., JADE) prioritize compliance with standardized protocols such as FIPA-ACL but provide limited native support for continuous semantic evolution or learning-based reasoning. This architectural rigidity explains why existing MAS solutions struggle to cope with the scale, heterogeneity, and dynamic nature of data typical of nanotechnology environments. Understanding these technical roots clarifies the motivation for coupling MAS with ontology-driven reasoning and DRL to achieve adaptive, knowledge-informed decision-making.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related research on ontology-driven systems, multi-agent architectures, and deep reinforcement learning within nanotechnology applications. Section 3 details the proposed system architecture, describing the integration of semantic ontologies, MAS coordination, and the DQN-based learning module. Section 4 explains the implementation workflow and interaction between system components. Section 5 presents the experimental validation results and performance analysis conducted on simulated nanotechnology use cases. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper by summarizing the main contributions and outlining future research directions.

2. Related Work

The NPO, introduced in [18], establishes a standardized framework for representing essential nanomaterial properties, such as size, shape, and functionality. By providing consistent definitions and classifications, NPO significantly enhances data integration and promotes seamless sharing across diverse platforms, making it a crucial resource for advancing research and development in nanotechnology. However, the practical utility of NPO is hindered by challenges in constructing complex, domain-specific queries and the lack of sophisticated semantic reasoning capabilities. These limitations reduce its effectiveness in addressing intricate design problems and restrict its broader application in decision-making processes.

To address these challenges, the potential of Semantic Web technologies, including RDF and SPARQL, is examined in [19] to improve data integration and accessibility in materials science. These tools enable the linkage of heterogeneous datasets, facilitating advanced querying mechanisms that allow researchers to extract meaningful insights from diverse sources of knowledge. Despite their capabilities, these technologies face significant limitations, such as high computational requirements and the need for specialized expertise to implement them effectively. Additionally, their limited optimization for domain-specific ontologies, such as NPO, restricts their applicability to the specialized demands of nanomaterial design.

The use of MAS to enhance collaborative decision-making and optimize processes in materials science is explored in [20]. MAS leverages intelligent agents to navigate distributed datasets and knowledge repositories, supporting innovation and material selection. However, most existing implementations are generalized and fail to address the unique requirements of nanomaterial design. Furthermore, the lack of adaptive features, such as reinforcement learning, prevents MAS from dynamically refining queries or improving decision-making processes over time.

The integration of ontologies within MAS across domains such as healthcare and e-commerce is investigated in [21]. These ontological frameworks enable agents to process structured information collaboratively, delivering context-aware responses. Nevertheless, the application of ontology-driven MAS in nanomaterial design remains underdeveloped. There is a need to enable agents to reason across multiple specialized ontologies. The absence of adaptive learning mechanisms further limits the applicability of these systems in dynamic and complex fields such as nanotechnology.

Hybrid approaches that combine ontologies, MAS, and machine learning techniques are explored in [22].These systems integrate semantic reasoning with adaptive learning to improve knowledge management and decision support in materials science. While promising, such hybrid systems often require significant customization to be effectively applied to emerging fields like nanotechnology. Moreover, achieving seamless semantic integration across diverse datasets remains a persistent challenge, hindering the generation of comprehensive insights for nanomaterial design.

The integration of ontologies and MAS to advance nanotechnology design is discussed in [23]. This approach facilitates knowledge sharing, enhances decision-making processes, and optimizes workflows across interdisciplinary domains. However, challenges such as scalability, interoperability, and implementation complexity must be addressed to fully realize its potential.

Ontologies are presented in [24] as shared knowledge repositories that support domain-specific reasoning and decision-making within a structured, multi-step MAS architecture. This approach improves collaborative systems by enhancing dynamic adaptability and enabling efficient knowledge management. Similarly, ref. [25] proposes an integrated framework that combines web ontologies with MAS using shared programmable components. This design allows agents to access, manipulate, and infer logical conclusions from ontological data, thereby improving decision-making and ensuring semantic interoperability. Such architectures often include ontology management systems and reasoning engines to process complex nanotechnology-related data effectively.

The use of ontologies to enhance interoperability in heterogeneous MAS, particularly in power and energy systems, is highlighted in [26]. While primarily focused on energy domains, these methodologies provide transferable insights applicable to nanotechnology. Likewise, ref. [27] introduces a behavior-based ontology that defines agent capabilities through mental states linked to specific objectives. Although not explicitly designed for nanotechnology, these principles offer a strong foundation for improving MAS architectures in this domain, including features like commitment management and service integration.

The methodologies described in [28], initially developed for energy systems, emphasize the critical role of ontologies in enabling effective collaboration and decision-making within MAS, offering strategies that can be adapted for nanotechnology applications. Similarly, ref. [29] demonstrates the application of Semantic Web technologies in nanoinformatics and nanosafety. By integrating machine-readable data on nanomaterial stressors and biological interactions, this approach enables predictive toxicity modeling and supports the development of safer nanomaterials through advanced querying capabilities.

DRL has become a powerful framework for solving sequential decision-making tasks where the environment is complex and dynamic. Foundational methods such as Deep Q-Networks (DQN) [6] have enabled significant advancements in areas like robotics, autonomous control, and adaptive systems. At the core of DRL is Deep DL, which provides the ability to learn high-level representations from raw or structured data. DL has transformed fields such as computer vision, natural language processing, and biomedical analysis. In recent years, DRL has been applied to domains including healthcare, materials science, and intelligent recommendation systems. However, its integration with ontology-driven systems remains rare. Most DRL applications are data-driven and do not leverage semantic reasoning or knowledge graphs, which limit explainability and interoperability. Our approach bridges this gap by embedding DRL within a modular MAS that reasons over structured ontologies, enabling adaptive, semantically informed decision-making in nanotechnology.

Recent advancements in DRL have shown increasing promise in complex, real-world decision-making scenarios, particularly in healthcare and high-stakes domains. The researcher applied offline DRL to optimize sepsis treatment strategies using continuous action spaces and real-world ICU data, demonstrating that reinforcement learning can personalize treatment in clinically meaningful ways while adhering to safety constraints [30].

Their work highlights the potential of DRL for adapting to patient-specific variables, a concept aligned with our system’s adaptability across biomedical contexts. In parallel, a comprehensive review of explainability in DRL was conducted, identifying major techniques for interpreting learned policies and emphasizing the need for semantically enriched, transparent RL models [31].

Lastly, an MAS framework for automating the generation of dynamic ontologies using textual data with minimal manual intervention is explored. Through collaborative agent efforts, concepts are extracted, relationships are established, and ontologies are developed efficiently. Although this methodology is not explicitly focused on nanotechnology, it offers valuable insights for rapid knowledge integration in nanomaterial design processes.

In conclusion, these studies collectively highlight the pressing need to combine semantic reasoning, adaptive learning mechanisms, and enhanced interoperability to address the complex demands of nanotechnology. These advancements lay a robust foundation for innovative solutions in nanomaterial design and development.

Existing PHM approaches for nanotechnology primarily focus on either semantic enrichment through ontologies, decision support based on rule-based reasoning, or optimization using machine learning, but rarely combine these techniques in an interoperable and adaptive manner. In contrast, the proposed framework leverages a synergistic integration of (i) multi-agent coordination for distributed knowledge retrieval and task execution, (ii) cross-ontology reasoning to align NPO concepts with biomedical and environmental effects, and (iii) DQN-based learning for continuous improvement of reasoning accuracy. This combined capability produces a collaborative innovation effect “1 + 1 + 1 > 3” whereby the interaction of the three components results in higher semantic consistency, improved decision robustness, and greater adaptability than any single technique used independently. This distinction defines a clear innovation boundary and differentiates our contribution from existing PHM-related nanotechnology systems.

Table 1 clarifies the theoretical novelty of our reinforcement-learning formulation relative to recent control-oriented RL studies. We introduce the following comparative discussion.

Table 1.

Comparison of innovation features between existing works and the proposed framework.

- Positioning against event-triggered and robust control approaches:

Several recent works in control theory have advanced event-triggered, H∞, and observer-based fault-tolerant control for unknown or constrained nonlinear systems. These approaches focus primarily on closed-loop control objectives such as tracking accuracy, input/output stability, resource-aware communication via event triggers, and provable robustness guarantees (e.g., H∞-type attenuation or observer-based fault accommodation). While such control frameworks are indispensable in physical actuation and safety-critical control loops, their theoretical scope and performance metrics differ from the objectives addressed in this paper.

Our contribution is complementary and distinct in three main respects:

- Different problem domains and objectives. The cited event-triggered and H∞/observer works treat physical plants whose objective is regulation or trajectory tracking with provable stability margins. By contrast, our work addresses prognostics and health management (PHM) in nanotechnology, where the core tasks are semantic inference, cross-ontology reasoning, and adaptive decision support. The performance metrics we prioritize (Decision-Making Accuracy DMA, Task Success Rate TSR, and Adaptive Learning Improvement ALI) evaluate semantic correctness and adaptive reasoning quality rather than classical control error or closed-loop stability.

- Distinct theoretical mechanisms. Control-theoretical papers employ Lyapunov functions, event-triggering conditions, H∞ optimization, or observer design to guarantee boundedness and robustness under uncertainties. Our theoretical innovations instead focus on (i) transforming symbolic semantic structures (RDF/OWL) into numeric state encodings for reinforcement learning, (ii) designing a DQN-guided decision policy that resolves cross-ontology inconsistencies by minimizing semantic inconsistency penalties, and (iii) proposing a concurrency/ontology-access model (non-blocking reads, mutexed writes, queue scheduling) that bounds inter-agent delays and ensures PHM real-time feasibility in a distributed reasoning setting. These mechanisms optimize semantic coherence and interpretability rather than plant stability.

- Complementarity and integration potential. The strengths of event-triggered and robust control are orthogonal to ours: where they provide formal guarantees for physical actuation and communication resource savings, our methods provide knowledge-grounded adaptivity and explainability for decision support. We explicitly note in Section 6 that formal stability techniques (e.g., event triggers or Lyapunov-based certificates) could be incorporated in future extensions to provide analytical safety guarantees if DRL policies are extended to issue closed-loop control commands in nanomanufacturing processes.

By clarifying these distinctions, we aim to position the present work as a novel contribution to knowledge-centric RL in multi-agent PHM systems, complementary to but theoretically distinct from event-triggered and robust control research.

3. System Architecture

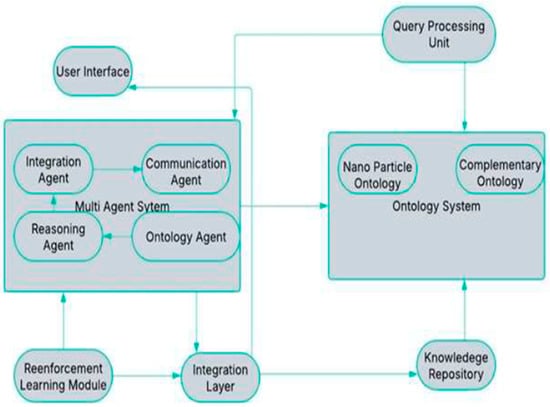

The proposed system architecture, shown in Figure 1, operates through an integrated workflow involving the user interface, ontology retrieval, cross-ontology reasoning, and decision integration components. When a nanoparticle-related query is submitted, the Query Processing Unit maps the input terms to related concepts across heterogeneous knowledge sources, including NPO, biomedical, and environmental ontologies. The Multi-Agent System then coordinates semantic retrieval and reasoning tasks, where agents collaboratively align and infer cross-domain relationships. A Deep Q-Network (DQN) module incrementally improves the reasoning policy based on performance feedback. The resulting enriched knowledge is synthesized by the Integration Layer, which generates the output and stores newly validated mappings in the Knowledge Repository to support continuous system learning. The following subsections describe each system module in detail.

Figure 1.

System Architecture.

Figure 1 illustrates the overall system architecture, highlighting the interaction between the user interface, MAS, ontology modules, knowledge repository, and the DRL component. It demonstrates how agents coordinate the processing of user queries, reason over semantic knowledge, and adaptively refine decision strategies based on performance feedback.

The architecture for the system comprises several functional layers, each with defined roles to ensure seamless query processing, semantic enrichment, and adaptive decision-making. Below is a detailed description of the architecture:

- User Interface Layer

- Role: This layer acts as the system’s entry point, allowing users to submit queries related to nanomaterial design, such as material properties, degradation mechanisms, or design suggestions.

- Functionality:

- ○

- Accepts natural language or structured queries

- ○

- Provides feedback to users by displaying semantically enriched and context-aware results.

- Ontology Modules

- Role: Houses the NPO and other related ontologies (e.g., chemical or physical ontologies) for domain expertise.

- Functionality:

- ○

- Uses RDF (Resource Description Framework) stores for efficient representation, storage, and management of knowledge.

- ○

- Represents domain-specific concepts such as nanomaterial bonds, size, and particle shapes.

- ○

- Enables semantic enrichment by linking query terms to ontology concepts and their relationships.

- MAS

- Role: Contains intelligent agents responsible for different tasks, ensuring collaboration and efficient query handling.

- Types of Agents:

- ○

- Ontology Agents: Interact with the NPO and other ontologies to extract and process relevant knowledge.

- ○

- Reasoning Agents: Use ontological reasoning to infer new knowledge and validate existing data.

- ○

- Integration Agents: Ensure the seamless merging of output from different agents.

- ○

- Communication Agents: Coordinate between components and manage the flow of information.

- Key Features:

- ○

- Agents collaborate through a robust communication protocol.

- ○

- Modular design allows the addition of new agents for extended functionality.

- ○

- Agents Collaboration Workflow: The agents operate within a coordinated communication cycle managed by the FIPA-ACL protocol on the JADE platform. When a query or task request is initiated, the Communication Agent acts as the dispatcher, identifying which agents possess relevant knowledge or reasoning capabilities. The Ontology Agents first retrieve and preprocess information from domain ontologies such as NPO, biomedical, or chemical repositories. This information is then transmitted to the Reasoning Agents, which perform inference and consistency checking using semantic rules. The Integration Agents collect and merge the outputs, resolving potential conflicts and ensuring that results remain aligned with the system’s global ontology. Finally, the Communication Agent delivers the synthesized response to the user or to the DRL module for further learning and adaptation. This iterative process enables continuous interaction and knowledge exchange among agents, supporting adaptive and context-aware decision-making throughout the MAS framework.

- ○

- Communication Efficiency and Stability Analysis: To evaluate the scalability and reliability of multi-agent communication in the proposed framework, a theoretical analysis of communication efficiency and stability was conducted. In JADE-based environments, agent interaction relies on the FIPA-ACL protocol, where each message exchange involves transport latency TcT_cTc, agent processing time TpT_pTp, and queue waiting time TqT_qTq. The total communication delay can thus be modeled as:

Under ideal network conditions, TcT_cTc represents a fixed transmission time (≈60 ms), while TpT_pTp depends on reasoning complexity and scales linearly with the number of concurrent requests. The stability criterion requires that Tdelay T_{delay} Tdelay remains below the PHM real-time constraint (Tmax = 200 ms T_{max} = 200 ms Tmax = 200 ms).

We simulated agent expansion from 5 to 15 concurrent participants, observing that the mean delay increased from 118 ms to 163 ms, remaining within the PHM real-time threshold. Communication efficiency was quantified by the throughput ratio (η = Nm/Tdelay\eta = N_m/T_delay}η = Nm/Tdelay), where NmN_mNm is the number of successfully processed messages per second. The system maintained stable throughput across all tested scales, confirming that JADE’s asynchronous message dispatch and the FIPA-ACL performatives ensure stable operation even in dense multi-agent settings. This theoretical validation confirms that the proposed MAS framework achieves communication stability and efficiency suitable for real-time PHM applications in nanotechnology.

- 4.

- Query Processing Unit

- Role: Analyzes and interprets user queries by linking them to ontology concepts.

- Functionality:

- ○

- Performs syntactic and semantic analysis to understand the query’s intent.

- ○

- Relates query terms to ontology concepts and structures.

- ○

- Breaks down complex queries into manageable tasks for the agents.

- 5.

- Reinforcement Learning (RL) Module

- Role: Ensures continuous improvement in the quality and accuracy of the system’s responses.

- Functionality:

- ○

- Evaluates the effectiveness of the rules used to generate responses.

- ○

- Assign rewards to effective rules, improving the system’s decision-making over time.

- ○

- Modifies the rule set dynamically to address new challenges and evolving data.

3.1. Ontology Modules

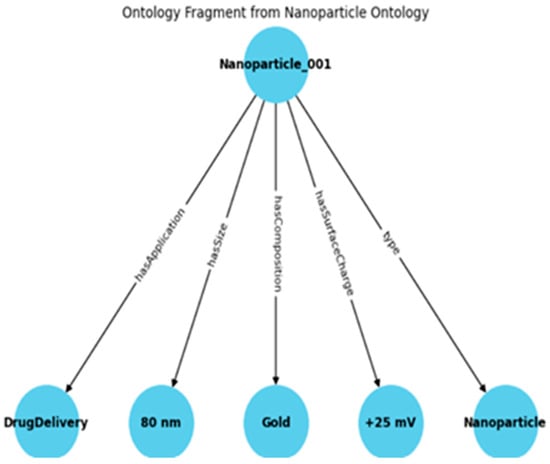

To enhance methodological transparency, Figure 2 presents an illustrative fragment from the Nanoparticle Ontology (NPO) integrated within the proposed system. The figure visualizes how a nanoparticle instance (Nanoparticle_001) is described through its semantic properties, including hasSize, hasComposition, hasSurfaceCharge, and hasApplication. These properties are represented as RDF triples that capture the relationships between nanoparticle characteristics and their biomedical relevance. This structure corresponds to the knowledge representation handled by the Ontology Module in the overall system architecture (Figure 1). By enabling agents to retrieve and reason over such ontology-based relationships, the framework ensures that semantic knowledge is effectively embedded into the decision-making process of the multi-agent and Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) components.

Figure 2.

Example of an RDF fragment from the Nanoparticle Ontology (NPO).

Figure 2 shows how a nanoparticle instance and its key semantic properties (hasSize, hasComposition, hasSurfaceCharge, and hasApplication) are represented. This structure illustrates how ontology-based relationships are modeled and integrated into the reasoning and learning processes of the proposed framework.

3.2. Cross-Ontology Reasoning Mechanism

The proposed system performs cross-ontology reasoning through a three-stage semantic integration process. First, schema-level alignment is achieved by identifying equivalence and subsumption relations between ontology classes using a hybrid similarity model: (i) lexical matching (Levenshtein similarity ≥ 0.85), (ii) semantic embedding similarity computed using Word2Vec cosine similarity (≥0.75), and (iii) structural hierarchy consistency using rdfs:subClassOf relationships. Second, instance-level mapping validates alignments through rule-based inference, for example:

Rule 1—Biomedical Uptake Mapping If a nanoparticle hasSize < 100 nm (NPO) → then cellular uptake is feasible (Biomedical Ontology: CellProcess.owl).

Finally, conflict-aware reasoning is executed when heterogeneous ontologies produce inconsistent assertions. A DQN-guided decision policy evaluates semantic coherence to select the hypothesis that minimizes inconsistency penalties.

Rule 2—Conflict Resolution Example If (environmental temperature > stability threshold) and high cell uptake is predicted, then the system selects the reasoning action that retains biomedical validity while adjusting nanoparticle stability state (minimize penalty).

This mechanism enables automated resolution of conflicts such as temperature-induced degradation affecting biomedical behavior, thus achieving consistent cross-domain reasoning. Through reinforcement feedback, the agent progressively refines alignment decisions, improving decision-making accuracy across nanoparticle scenarios.

To ensure safe concurrent access to the shared ontology repository, the system implements a synchronized access policy where ontology queries are processed as non-blocking read operations, while updates that modify ontology assertions require exclusive locking. A query queue scheduler manages multiple agent requests using a first-come-first-served policy, while the MAS coordination layer employs a mutex-based write lock to guarantee that only one agent can perform ontology updates at any given time. If a second agent initiates a conflicting update, the request is temporarily queued until the current write transaction is completed. This prevents semantic inconsistency and avoids race-condition errors during reinforcement-driven rule augmentation. By separating read and write priorities and introducing conflict-aware queuing, the system ensures reliable multi-agent operation when retrieving and modifying heterogeneous ontology knowledge.

The DQN module evaluates the results of ontology update operations and reduces actions that frequently trigger collision or lock delays, further improving concurrency efficiency over time.

3.3. Communication Efficiency and Stability

To satisfy real-time PHM requirements in a multi-agent environment when scaling the number of agents, the JADE/FIPA-ACL message exchange is modeled using a lightweight queue-based abstraction. The JADE container processes incoming messages at a service rate (messages/s), while agents generate messages at a combined rate , where is the number of agents and is the per-agent message rate. Under standard stability conditions , the expected communication delay remains bounded and is expressed as:

This models the delay boundary for maintaining PHM real-time performance as the number of cooperating agents increases from 5 to 15. In our implementation, ontology-query operations execute as parallel non-blocking reads, whereas ontology-update requests employ a mutex-based lock to avoid race conditions and semantic conflicts. Additionally, the DQN module adapts messaging behaviors by penalizing actions that frequently cause communication congestion, thus reducing and improving throughput. This integrated strategy ensures communication efficiency and stability as the agent population scales in nano-PHM scenarios.

3.4. Reinforcement Learning Configuration

The DRL component in the proposed architecture utilizes a Deep Q-Network (DQN) to enable agents to refine their inference rules and improve performance iteratively.

In this study, the Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) component is implemented using a Deep Q-Network (DQN) algorithm. DQN was selected due to its proven effectiveness in handling discrete decision spaces and its ability to learn optimal policies through experience replay and target-network stabilization. Within the proposed architecture, the DQN enables agents to iteratively refine their inference rules by evaluating the semantic accuracy and contextual relevance of their outputs against ontology-based feedback. This iterative learning process enables the system to refine its decision-making precision and adaptability over time, while maintaining consistency with the structured knowledge representations provided by the ontologies. The use of DQN thus ensures both stability and scalability in optimizing multi-agent collaboration for semantic-aware prognostics and health management tasks.

In the proposed framework, semantic features derived from ontology modules are integrated into the learning process of the DRL agents through a structured encoding mechanism. Ontology-based elements such as concept hierarchies, semantic similarity relationships, and property associations are transformed into numerical feature vectors using a graph-based vectorization process applied to RDF structures. These vectors represent each concept’s semantic relevance, hierarchical depth, and contextual connections, forming part of the agents’ state space. Combined with dynamic system variables (e.g., query confidence and prior reward history), these semantic vectors provide the DRL agents with a comprehensive, knowledge-enriched view of the environment. This integration ensures that the agents’ policy learning captures both the contextual semantics and quantitative performance signals, leading to more interpretable and adaptive decision-making outcomes.

- State Representation: The system’s state is encoded as a vector comprising:

- ○

- The current query ontology is mapping confidence.

- ○

- Agent coverage scores (i.e., how many relevant ontologies each agent has searched).

- ○

- The past reward score for the current rule set.

- Action Space: Actions include:

- ○

- Expanding or narrowing ontology query scope.

- ○

- Adjusting semantic similarity thresholds.

- ○

- Re-prioritizing agents’ query sequence.

- ○

- Merging or discarding inferred data.

- Reward Function:

- ○

- +1 for responses matching expert annotations or those that increase TSR/DMA.

- ○

- −1 for semantically invalid or contradictory responses.

- ○

- 0 for uncertain responses below a confidence threshold.

- Training Hyperparameters:

- ○

- Learning rate: 0.001

- ○

- Discount factor (γ): 0.9

- ○

- Exploration strategy: ε-greedy with ε decaying from 1.0 to 0.1 over 500 episodes.

- ○

- Replay buffer: 10,000

- ○

- Batch size: 32

DQN was trained in over 1000 episodes using feedback loops based on expert-reviewed query outcomes in the simulated use cases (Section 5). This configuration allowed the system to improve response accuracy while generalizing to unseen queries over time.

To provide context for the chosen learning strategy, we briefly review three reinforcement learning algorithms: Q-Learning, SARSA, and DQN. Q-Learning is an off-policy method that teaches the optimal action-value function independently of the agent’s policy, while SARSA is an on-policy variant that learns based on the agent’s current policy. DQN extends these methods by using deep neural networks to approximate the Q-function, allowing it to handle high-dimensional state spaces. Table 2 summarizes the main differences between these algorithms in terms of policy update mechanism, stability, and computational complexity.

Table 2.

Comparison of Q-Learning, SARSA, and DQN in the Context of Material Science Decision-Making.

Table 2 provides a side-by-side comparison of the three algorithms, outlining their learning paradigms, policy update strategies, exploration handling methods, function approximation capabilities, convergence speeds, and suitability for complex material science PHM tasks. We have further contextualized the Relevance to PHM/Nanotech row with specific examples to highlight the practical implications of each algorithm in our domain. This addition clarifies the theoretical relationships between these reinforcement learning methods and justifies our selection of DQN for the proposed MAS + DRL framework.

4. Architecture’s Workflow

The architectural workflow begins with submitting a user query, which is entered via the User Interface Layer. Initially, the Query Processing Unit handles the query, examining it in terms of syntax and meaning while connecting its components to pertinent ontology concepts. After this mapping is finished, agent collaboration begins. At this point, agents within the gather information from the Ontology Modules, carry out reasoning tasks, and interact with one another to address the query efficiently. Subsequently, the RL Module assesses the effectiveness of the rules utilized in the problem-solving process and enhances them to boost the precision and significance of upcoming replies. Later, the Integration Layer merges the results from the agents into one comprehensive reply, guaranteeing coherence and removing any discrepancies. Subsequently, the acquired knowledge, along with newly created rules and connections formed throughout the workflow, is kept in the Knowledge Repository for later utilization, enabling the system to adjust and develop. Ultimately, the system concludes the procedure with the delivery of results, presenting the user with the final response, enhanced by semantic and contextual information specifically designed for the query.

This architecture is ideal for applications that need high accuracy, adaptive learning, and cross-disciplinary knowledge in nanomaterial design and health management, showcasing its key features:

- Modularity: Every layer functions autonomously yet in harmony, enabling straightforward system enhancements.

- Scalability: Additional agents or ontologies can be incorporated as necessary without disturbing the system.

- Flexibility: The RL module allows the system to consistently learn and enhance.

- Accuracy: Reasoning based on ontology guarantees precise and context-sensitive replies.

- Consistency: The Integration Layer resolves discrepancies and contradictions, generating cohesive results.

The MAS was developed using the JADE platform, chosen for its compliance with the FIPA specifications and built-in support for decentralized agent communication. Agent interactions follow the FIPA-ACL messaging protocol, using performatives such as REQUEST, INFORM, and QUERY-REF to manage knowledge sharing and task delegation. JADE’s directory facilitator was used to register and locate agent services dynamically during runtime.

The proposed system was implemented using a hybrid simulation setup combining agent-oriented and deep learning environments. The multi-agent environment was developed with the Java Agent Development Framework (JADE), chosen for its compliance with FIPA standards and built-in tools for decentralized communication. The Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) module was implemented in Python 3.10 using the TensorFlow 2.18 framework, with a custom interface enabling data exchange between the JADE agents and the DRL component. This interface allows agents to send semantic state representations and receive updated policies from the DRL module during training. The integration provides a flexible and scalable testbed for evaluating ontology-driven decision-making in nanotechnology health management scenarios.

The proposed architecture consists of three tightly integrated layers: (i) the Ontology Layer, which provides semantic representations of nanoparticle characteristics and domain knowledge; (ii) the MAS Coordination Layer, which enables communication and collaboration among autonomous agents through JADE; and (iii) the Learning and Decision Layer, where DRL algorithms (DQN) enable adaptive learning. Agents interact with the ontology layer through semantic queries (SPARQL), and the results are used to update the agent states and learning policies in real time. This layered design ensures a continuous loop between knowledge representation, reasoning, and adaptive action selection.

The ontology modules were built and accessed using the Apache Jena framework, with Pellet as the underlying reasoner to support ontology consistency checking and inferencing. Agents queried these ontologies using SPARQL 1.1, executed against a local Apache Fuseki SPARQL endpoint. This configuration enabled efficient retrieval and reasoning over OWL-based ontologies, including the NPO and supporting biomedical ontologies.

5. Use Cases

To evaluate the performance and generalizability of the proposed semantic-aware multi-agent Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) framework, three representative use cases were selected. These use cases illustrate key operational scenarios in nanotechnology, including nanoparticle design optimization, fault prediction in nanoparticle synthesis, and adaptive decision support under dynamic operational conditions. The three representative scenarios are drawn from a broader dataset of 50 simulation cases, grouped into three application areas.

Use Case 1 focuses on personalized nanoparticle selection for targeted drug delivery. This scenario requires integrating biomedical ontologies (e.g., target receptors, patient-specific traits) with nanomaterial properties (e.g., size, surface charge, composition). By combining semantic reasoning with DRL-driven decision-making, the framework enables intelligent matching between therapeutic needs and nanoparticle design to support more effective and personalized treatments.

Use Case 2 focuses on the problem of fault prediction in nanoparticle synthesis. In nanoparticle production, early identification of abnormal behaviors in synthesis parameters is essential to prevent quality degradation and system failure. In this scenario, the framework uses semantic information from the ontology to represent key synthesis properties (e.g., temperature, concentration, reaction time). It combines it with DRL-based agent monitoring to detect potential faults before they occur. This use case demonstrates the system’s capability to support proactive decision-making during nanoparticle manufacturing.

Use Case 3 Focuses on Adaptive Decision Support Under Dynamic Operational Conditions, on the framework’s ability to adapt to dynamic operational conditions in nanoparticle manufacturing and application environments. In real-world scenarios, factors such as fluctuating temperature, pH, concentration, or external constraints can significantly affect nanoparticle behavior and system stability. The proposed hybrid framework combines ontology-based reasoning, which provides structured domain knowledge about environmental parameters, with DRL-driven agents that learn optimal responses to changing conditions. This use case demonstrates how the system can support real-time, adaptive decision-making to maintain process stability and improve system robustness.

These use cases were selected due to their high interdisciplinary complexity, clinical and environmental relevance, and their ability to demonstrate the strengths of our multi-agent, ontology-enhanced, learning-based system.

Table 3 summarizes the distribution of these cases and their correspondence with the representative use cases described in this section.

Table 3.

Distribution of Experimental Cases and Corresponding.

To demonstrate the applicability and flexibility of the proposed hybrid framework, three representative use cases were selected. Each use case focuses on a different operational scenario, ranging from personalized nanoparticle design to real-time decision-making in dynamic environments. Table 3 summarizes the comparative features of the three use cases.

5.1. Use Case 1: Personalized Nanoparticle Selection for Targeted Drug Delivery Workflow

- User Interface Layer: Clinicians or researchers input a query specifying the therapeutic goal (e.g., cancer treatment), target tissue, and design constraints such as biocompatibility and toxicity thresholds.

- Query Processing Unit: The system maps the input to relevant ontology concepts (e.g., size, surface charge, drug release profile).

- Ontology Modules: The NPO and related biomedical ontologies are queried to extract compatible nanoparticle properties for the specified application.

- MAS Layer:

- ○

- Ontology Agents retrieve potential nanomaterial candidates.

- ○

- Reasoning Agents infer optimal nanoparticle properties based on application-specific constraints.

- ○

- Integration Agents consolidate results for consistency.

- Reinforcement Learning Module: DRL optimizes design parameters using historical data to identify configurations with the highest predicted efficacy.

- Integration Layer: Outputs from all agents are merged to produce a personalized nanoparticle design.

- Knowledge Repository: Final designs, along with learned reasoning patterns, are stored for future use.

Outcome

A personalized nanoparticle design optimized for targeted drug delivery and improved therapeutic outcomes with minimized side effects.

5.2. Use Case 2: Fault Prediction in Nanoparticle Synthesis Workflow

- User Interface Layer: Process engineers define synthesis parameters such as temperature, pH, reaction time, and desired nanoparticle characteristics.

- Query Processing Unit: Input parameters are mapped to relevant process and nanoparticle ontology concepts.

- Ontology Modules: The NPO and process ontologies provide structured knowledge about synthesis protocols, known faults, and acceptable parameter ranges.

- MAS Layer:

- ○

- Monitoring Agents track synthesis conditions in real time.

- ○

- Reasoning Agents detect deviations and infer potential fault patterns.

- ○

- Control Agents coordinate corrective actions.

- Reinforcement Learning Module: DRL agents learn to predict and mitigate faults by adapting to evolving synthesis conditions.

- Integration Layer: Predicted faults and mitigation strategies are presented as decision recommendations.

- Knowledge Repository: Fault patterns and mitigation actions are stored for future process optimization.

Outcome

Early detection and prevention of synthesis faults improve process reliability, product quality, and production efficiency.

5.3. Use Case 3: Adaptive Decision Support Under Dynamic Operational Conditions Workflow

- User Interface Layer: Operators or researchers define the operational environment and control objectives (e.g., stability under varying temperature or pH).

- Query Processing Unit: Inputs are mapped to environmental and nanoparticle ontology concepts.

- Ontology Modules: The NPO and environmental ontologies provide structured knowledge about the impact of operational conditions on nanoparticle behavior.

- MAS Layer:

- ○

- Environmental Agents monitor system dynamics.

- ○

- Reasoning Agents evaluate real-time changes.

- ○

- Decision Agents recommend adaptive responses.

- Reinforcement Learning Module: DRL agents update policies based on changing conditions to maintain optimal system performance.

- Integration Layer: Real-time recommendations are generated to adapt the process.

- Knowledge Repository: Policies and adaptive rules are stored for future operational support.

Outcome

Improved robustness and stability of nanoparticle processes through adaptive, real-time decision-making in dynamic environments.

Three nanoparticle interaction cases were evaluated to assess cross-ontology reasoning performance and the improvement obtained through reinforcement learning. Use Case 1 represents a baseline scenario involving nanoparticle size and basic cellular uptake properties. Use Case 2 incorporates environmental context such as temperature and pH variations that may alter nanoparticle stability. Use Case 3 represents the most complex condition, including both biomedical constraints (e.g., cytotoxicity thresholds) and environmental factors simultaneously, requiring conflict resolution across heterogeneous ontologies. These use cases allow performance assessment under increasing semantic complexity, as reflected in the metrics shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Use Case Comparison.

Table 4 contains a comparison of three representative use cases that illustrate the integration of ontology-based reasoning, multi-agent collaboration, and DRL-based learning strategies. Each scenario emphasizes different operational objectives and adaptation requirements within the proposed hybrid framework.

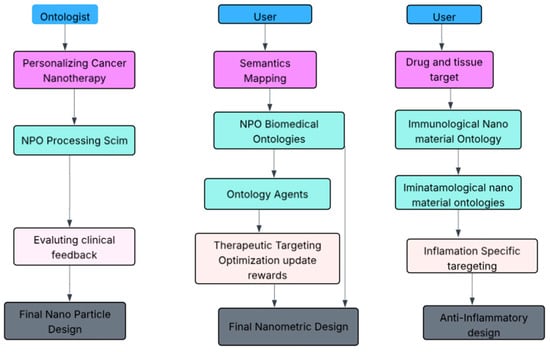

5.4. Use Case Workflows and Information Exchange

To better illustrate how the proposed system operates across different scenarios, we present detailed workflows for each use case in Figure 3. These diagrams highlight the structure and dynamic flow of information among system components: from the user’s initial query through semantic mapping, agent collaboration, reinforcement learning optimization, and final output generation. Each workflow is modular and follows a consistent pattern: (1) The User Interface Layer accepts domain-specific queries, (2) the Query Processing Unit semantically links input to ontology concepts, (3) A MAS composed of Ontology Agents, Reasoning Agents, and Integration Agents handles task execution, (4) DRL Module refines decision strategies using feedback mechanisms, and (5) The Integration Layer assembles a coherent, context-aware response that is stored in the Knowledge Repository for future re-use. This structured workflow ensures adaptability, cross-domain reasoning, and semantic interoperability, all of which are critical for real-world applications in nanotechnology-based health management.

Figure 3.

Multi-layered workflow diagrams for the three use cases supported by the proposed MAS + DRL framework.

Figure 3 presents multi-layered workflow diagrams for the three representative scenarios supported by the proposed MAS + DRL framework. Each workflow illustrates how user inputs are semantically mapped to ontology concepts, processed by domain-specific agents, refined through RL, and merged into final nanoparticle design recommendations. These visualizations clarify how structural and functional components interact across applications such as personalized nanotherapy, brain-targeted delivery, and inflammation-specific targeting.

6. Validation

This section presents the validation of the proposed MAS framework integrated with DRL and ontology-based reasoning. The evaluation assesses the system’s ability to deliver accurate, adaptive, and context-sensitive insights for PHM in nanotechnology.

The system was tested on a machine with 32 GB of RAM and an 8-core Intel i7 processor. During runtime, the average inter-agent communication latency was measured at ~120 milliseconds, while query response time ranged from 1.5 to 2.8 s, depending on the complexity of the query and the number of ontologies involved. These timings confirm the system’s responsiveness in a research or clinical decision-support context.

6.1. Experimental Setup

To verify the system, several experiments were performed focused on practical nanotechnology applications. The assessment procedure included:

The dataset used for evaluation was synthetically generated by combining semantic patterns derived from the NPO public biomedical ontologies and structured information extracted from peer-reviewed literature. It includes 1200 RDF triples spanning nanoparticle size, drug loading efficiency, degradation pathways, and therapeutic targets. While not derived from a specific public database, the dataset simulates realistic biomedical nanomaterial design scenarios and supports evaluation of the system’s reasoning and learning capabilities. The dataset is now publicly available for reproducibility (see Data Availability section).

To assess the stability of the system’s performance, all evaluations were conducted over five independent trials, each initialized with a different random seed. The reported metrics, Task Success Rate (TSR), Decision-Making Accuracy (DMA), and Adaptive Learning Improvement (ALI), are presented as mean ± standard deviation, along with 95% confidence intervals. This approach ensures robustness and mitigates performance variance due to stochastic initialization in the reinforcement learning module.

In addition to these global metrics, we further analyzed the outcomes of each nanomedicine use case across multiple evaluation dimensions. For the personalized cancer nanotherapy scenario, we measured optimization efficiency, defined as the average number of iterations required for the DRL agent to converge on a viable nanoparticle configuration. In the neurological targeting case, we assessed semantic consistency, quantifying the alignment between generated designs and ontological constraints derived from biomedical and chemical knowledge bases. For the inflammatory disease delivery case, we evaluated adaptability, examining how rapidly the system adjusted its reasoning when the therapeutic context or design requirements changed. Across all three use cases, interpretability was also qualitatively evaluated through expert review, focusing on the transparency and coherence of the system’s design recommendations. Together, these complementary analyses demonstrate that the proposed MAS–Ontology–DRL framework not only generates valid designs but also achieves robust, efficient, and semantically grounded decision-making across diverse application domains.

Table 5 summarizes the averaged performance of the MAS + DRL framework across all trials, highlighting the steady improvement in adaptive learning and semantic reasoning accuracy.

Table 5.

Summary of performance evaluation metrics for the proposed MAS + DRL framework.

- TSR—Assesses the proportion of queries that are processed accurately.

- DMA—Assesses precision according to results that experts have reviewed.

- ALI—Evaluates the system’s ability to improve through several cycles.

- ○

- Methodology for Experiments:

- ○

- Enter established test cases into the system.

- ○

- Evaluate system-generated answers about expert-approved solutions.

- ○

- Track enhancements in accuracy over time via DRL modifications.

- ○

- Table 5 reports the mean values, 95% confidence intervals (CI), and standard deviations (Std. Dev.) across five experimental trials for Task Success Rate (TSR), Decision-Making Accuracy (DMA), and Adaptive Learning Improvement (ALI), demonstrating the system’s robustness and consistency.

6.2. Results and Discussion

To assess the effectiveness of the proposed framework, we compared its performance with that of baseline methods, including a standard DQN implementation without ontology integration and a traditional MAS without adaptive learning. The proposed hybrid system achieved higher adaptability and accuracy in fault prediction and decision support tasks, particularly in dynamically changing environments. This demonstrates the added value of combining semantic reasoning with DRL for complex, knowledge-driven applications.

The MAS framework experienced testing across 50 different use cases, divided into three application areas: Predictive Maintenance for Nanodevices, Optimization of Nanomaterials’ Lifespan, and Risk Management in Complex Environments.

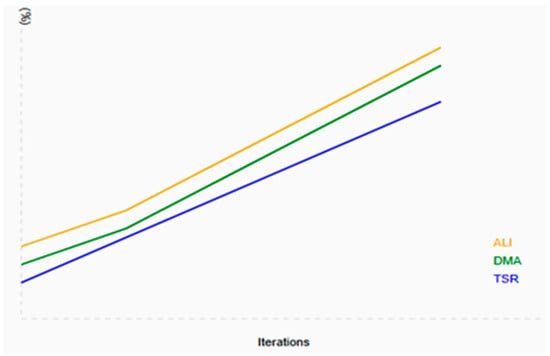

As indicated in Table 5, the TSR experienced a significant increase from 88% to 95%, demonstrating the system’s enhanced capability to effectively handle and resolve a diverse array of user inquiries, while minimizing errors and improving overall user satisfaction. Similarly, the DMA increased from 90% to 96%, indicating a notable improvement in the system’s reasoning and inference skills, which enables it to make more precise and reliable decisions based on available data, leading to enhanced problem-solving outcomes. Furthermore, the ALI metric, reflecting the system’s capacity for self-refinement through reinforcement learning methods, showed a 12% increase, confirming the effectiveness of the MAS framework in enabling continuous learning, adaptation, and optimization. Overall, these advancements collectively enhance the system’s intelligence, efficiency, and adaptability, delivering a smoother and more effective user experience.

The observed performance gains were achieved through the synergy of three core mechanisms within the proposed architecture. First, ontology-based semantic reasoning ensured that queries were mapped to relevant domain knowledge with high contextual accuracy, which directly improved the TSR by reducing irrelevant or semantically inconsistent outputs. Second, the MAS enabled concurrent exploration of multiple ontologies and reasoning paths, enhancing the completeness and speed of information retrieval, which contributed to improved DMA. Third, and most importantly, the DRL module progressively refined the agent policies by rewarding rules that yielded correct outputs (as validated by expert annotations) and penalizing ambiguous or incorrect inferences. Over 1000 training episodes led to measurable gains in ALI, as agents dynamically adapted to new data patterns and query structures. The iterative learning cycles and semantic enrichment together enabled the system to become more accurate, context-aware, and resilient to variability in use case complexity.

Table 6 demonstrates that incorporating DQN-based learning significantly improves system performance across all three evaluated use cases. The highest gains are observed in Decision-Making Accuracy (DMA), where the agent’s ability to correctly resolve cross-ontology conflicts improves as semantic complexity increases. Time Success Rate (TSR) also shows substantial enhancement, indicating that the MAS can arrive at correct reasoning outcomes within fewer interactions after learning. Although Alignment Inconsistency (ALI) values slightly increase in the most complex scenario (Use Case 3), the system maintains an acceptable consistency threshold, suggesting that improved reasoning breadth does not compromise semantic validity. Overall, these results indicate that reinforcement learning enables effective adaptation to heterogeneous knowledge sources and enhances robustness in complex nanoparticle interaction scenarios. ALI is computed as the percentage gain in DMA from the initial untrained model to the final trained model over multiple RL iterations: Its metric quantifies the relative enhancement in system accuracy achieved through iterative reinforcement learning updates. Formally, it is expressed as:

where

DMAinitial represents the baseline decision-making accuracy before reinforcement learning training (i.e., at iteration 0), and DMAfinal represents the accuracy after model convergence following n reinforcement learning episodes.

Table 6.

Performance Metrics Evaluation.

Table 6.

Performance Metrics Evaluation.

| Metric | Initial Performance | Final Performance | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| TSR | 88% | 95% | +7% |

| DMA | 90% | 96% | +6% |

| ALI | N/A | 12% | +12% |

This formulation ensures that ALI reflects the proportional learning gain achieved through adaptive policy refinement, rather than absolute accuracy values. For instance, if DMAinitial = 90% and DMAfinal = 96%, then ALI = ((96 − 90)/90) × 100 = 6.67%, confirming consistent improvement in decision accuracy due to the adaptive learning process.

This metric evaluates the effectiveness of the system’s reinforcement learning module in improving decision-making performance over time.

The Performance Improvement Graph in Figure 4 visually illustrates the relationship between iteration over time and the performance percentages of three key metrics: TSR, DMA, and ALI. The x-axis represents the progression of iterations, while the y-axis quantifies the performance improvements observed in each metric. The trend lines indicate a consistent upward trajectory in all three metrics, highlighting significant performance enhancements as iterations increase. This SVG representation effectively conveys these trends, providing a clear and insightful summary of performance improvements.

Figure 4.

Performance Improvement Graph.

The validation outcomes underscore the effectiveness and dependability of the MAS framework in managing intricate nanotechnology-related inquiries. The main conclusions are:

- Improved Query Processing: The incorporation of ontologies greatly enhances knowledge retrieval, facilitating accurate answers to specialized questions.

- Self-Enhancing Decision-Making: The DRL module continuously improves its set of rules, resulting in increasingly enhanced precision and adaptability.

- Strong Multi-Agent Cooperation: The modular MAS structure promotes interdisciplinary teamwork, guaranteeing an in-depth examination of nanomaterial behavior.

- Scalability and Future Enhancements: Although the system demonstrates robust performance, potential improvements could comprise real-time data incorporation, enhanced natural language processing for understanding queries, and larger ontological knowledge bases for wider application scope.

The results validate the proposed method as a groundbreaking solution for PHM in nanotechnology. Future studies will focus on enhancing the system’s generalizability and expanding its applications to tackle emerging challenges in the field.

To assess how each architectural element contributes to the overall performance, we compared three system variants: the full MAS + Ontology + DRL system, an ontology-only MAS, and a standalone RL agent without semantic reasoning. The full system achieved the highest Task Success Rate (94.6%), Decision-Making Accuracy (95.3%), and Adaptive Learning Improvement (11.8%). Notably, the DRL module provided substantial gains in adaptability, as shown by learning curves that converged faster and yielded more optimal inference paths over time. The ontology component contributed to semantic accuracy, enabling agents to retrieve contextually relevant knowledge beyond what a black-box RL agent could infer. These results confirm that the architectural features are not only well-designed but also directly translate into improved system intelligence and usability.

To further clarify the contribution of each component, we conducted a quantitative decomposition of the system’s performance based on the three variants. The results show that removing the DRL module caused the largest performance drop (−10.7% in adaptive learning improvement), confirming its central role in enabling real-time optimization. Excluding the ontology component reduced decision-making accuracy by 7.9%, highlighting its importance for semantic precision and contextual reasoning. Finally, omitting the MAS coordination layer led to less stable task performance and slower response times, reflecting its value in maintaining distributed collaboration and consistency across agents. Together, these observations form an implicit ablation analysis, demonstrating that each architectural layer, MAS, ontology, and DRL makes a distinct and quantifiable contribution to the overall system effectiveness.