Abstract

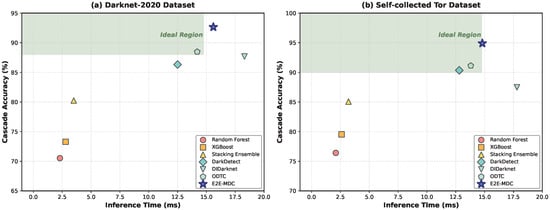

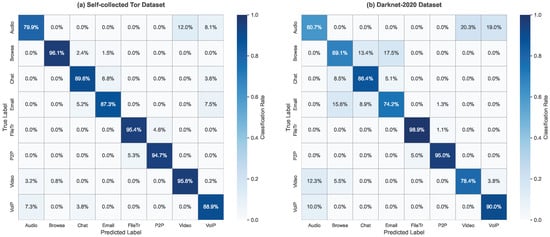

Accurate identification and classification of Darknet traffic is a critical technical challenge for network security supervision. Existing methods predominantly adopt single-modal features and independent classification strategies, making it difficult to effectively handle the hierarchical structural characteristics and complex encryption patterns of Darknet traffic. This paper proposes E2E-MDC (End-to-End Multi-modal Darknet Classification), an end-to-end deep learning framework based on conditional hierarchical mechanism for three-level hierarchical classification of Darknet traffic. The framework integrates four complementary feature extractors—byte-level CNN, packet sequence TCN, bidirectional LSTM, and Transformer—to comprehensively capture traffic patterns from multiple perspectives. A soft conditional hierarchical classification architecture explicitly models dependencies among Level 1 (Darknet type), Level 2 (application category), and Level 3 (specific behavior) by using upper-level prediction probability distributions as conditional input for lower-level classification. On the self-collected Tor dataset containing 8 applications and 8 behavior types, the system achieves 94.90% cascade accuracy, with Level 3 fine-grained classification accuracy reaching 95.02%. On the public Darknet-2020 dataset, cascade accuracy reaches 92.65%, representing improvements of 12% and 15% over existing state-of-the-art methods, respectively, while reducing hierarchical violation rate to below 0.8%. Experimental results demonstrate that the conditional hierarchical mechanism and multi-modal fusion strategy significantly enhance the accuracy and robustness of Darknet traffic classification, providing effective technical support for network security protection.

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of Internet technology, the Darknet has increasingly attracted widespread attention as a special network space. The Darknet refers to network spaces built upon Internet infrastructure that require specific software, configurations, or authorization to access. It primarily includes anonymous communication systems such as Tor (The Onion Router), I2P (Invisible Internet Project), Freenet, and ZeroNet. Although the original intention of Darknet technology is to protect user privacy and freedom of speech, its strong anonymity and encryption characteristics are also exploited for malicious purposes [1], making it a breeding ground for cybercrime, illegal transactions, terrorism, and other activities. Therefore, accurate identification and classification of Darknet traffic is of great significance for network security supervision, crime prevention, and forensic investigation.

Darknet traffic classification faces multiple technical challenges. First, Darknet protocols employ multi-layer encryption and onion routing technologies, rendering traditional Deep Packet Inspection (DPI)-based methods [2] ineffective. The encrypted payload prevents direct content inspection, while onion routing obscures the true source and destination of traffic. Second, traffic characteristics differ significantly across different Darknet platforms (Tor, I2P, Freenet, ZeroNet), while traffic patterns of different applications within the same platform are highly similar, creating difficulties for fine-grained classification. Third, the dynamic and adversarial nature of Darknet traffic requires classification methods to possess good robustness and adaptability to handle diverse traffic patterns and evasion techniques. Finally, practical applications need to meet real-time requirements while ensuring classification accuracy, imposing strict constraints on algorithm efficiency.

Existing Darknet traffic classification methods can be mainly divided into two categories. Traditional machine learning methods [3,4,5,6] rely on manually designed statistical features, such as packet size distribution, inter-packet intervals, and flow duration. Although these methods perform well in certain scenarios, they have inherent limitations. Feature engineering is time-consuming and labor-intensive, requiring extensive domain expertise. More critically, handcrafted statistical features struggle to capture deep temporal relationships in encrypted traffic, where the temporal ordering and dependencies of packets often carry crucial discriminative information that simple statistics cannot adequately represent.

In recent years, deep learning methods have begun to be applied in this field, demonstrating the capability for automated feature learning. DarkDetect [7] adopts a CNN-LSTM hybrid architecture, achieving 96% accuracy on darknet detection tasks. DIDarknet [8] converts traffic into images for classification using pre-trained ResNet-50. DarknetSec [9] introduces self-attention mechanisms to explore feature relationships. However, these methods exhibit several limitations that motivate our work.

First, most existing deep learning methods focus only on single-level classification tasks, ignoring the hierarchical structural characteristics of Darknet traffic. In practice, Darknet traffic naturally follows a three-level hierarchy: platform type (e.g., Tor, I2P), application category (e.g., Telegram, BBC), and specific behavior (e.g., video, browsing). Methods that treat classification as a flat problem fail to leverage this structural prior and may produce logically inconsistent predictions. For instance, a classifier might incorrectly predict “Freenet platform” at level 1 while simultaneously predicting “Telegram application” at level 2, violating the inherent constraint that Telegram only operates on Tor.

Second, existing methods mostly adopt single-modal features, failing to fully utilize multi-dimensional information in traffic data. DarkDetect [7] primarily relies on CNN-extracted spatial features and LSTM-captured temporal patterns, but does not consider raw byte-level information. DIDarknet [8] focuses exclusively on image-based representations converted from traffic matrices. DarknetSec [9] emphasizes statistical features with attention mechanisms. Each approach captures only a partial view of the traffic characteristics. Given that encrypted Darknet traffic exhibits complex patterns across multiple dimensions—byte-level protocol signatures, packet-level statistical distributions, flow-level temporal dynamics, and session-level global semantics—a single modality is inherently insufficient for comprehensive characterization.

Third, even among the few works that consider hierarchical classification [10,11], most employ independent classifiers at each level without explicitly modeling inter-level dependencies. This approach treats each level as a separate task, potentially leading to hierarchical violations where predictions at different levels are mutually inconsistent. Such violations not only indicate classification errors but also reduce the interpretability and trustworthiness of the system in security-critical applications.

To address these limitations, this paper proposes E2E-MDC (End-to-End Multi-modal Darknet Classification), an end-to-end deep learning framework based on conditional hierarchical mechanism for three-level hierarchical classification of Darknet traffic. The framework integrates four complementary feature extractors—byte-level CNN, packet sequence TCN, bidirectional LSTM, and Transformer—to comprehensively capture traffic patterns from multiple perspectives. A soft conditional hierarchical classification architecture explicitly models dependencies among Level 1 (Darknet type), Level 2 (application category), and Level 3 (specific behavior) by using upper-level prediction probability distributions as conditional input for lower-level classification.

Experimental results demonstrate that our method achieves a cascade accuracy of 94.90% on the self-collected Tor traffic dataset and 92.65% on the public Darknet-2020 dataset, representing improvements of 12% and 15% over existing state-of-the-art methods, respectively, while reducing the hierarchical violation rate to below 0.8%. Ablation experiments confirm the effectiveness of multi-modal fusion and conditional hierarchical design. Furthermore, the system achieves an inference speed of 1200 traffic windows per second on an RTX 3090 GPU (NVIDIA Corporation, Chengdu, China), meeting real-time detection requirements.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- Innovative proposal of a conditional hierarchical classification mechanism. Unlike traditional independent multi-task learning or hard cascade classification, this paper implements end-to-end hierarchical learning through a soft conditioning design that enables joint optimization across all classification levels. Specifically, the probability distribution (rather than hard decisions) of upper-level classification is used as conditional input for lower levels, enabling gradient backpropagation through Softmax operations while preserving prediction uncertainty information. This design maintains cascade accuracy of 94.90% while controlling the hierarchical violation rate below 0.8%.

- Design of a four-modal complementary feature extraction architecture tailored for Darknet traffic characteristics. Targeting different information dimensions of encrypted traffic, this paper carefully designs four specialized neural network modules: (i) byte-level CNN captures encrypted protocol patterns through learnable byte embeddings; (ii) temporal convolutional network employs exponentially growing dilation rates (1, 2, 4, 8) to extract multi-scale temporal patterns; (iii) bidirectional LSTM fuses recurrent features with self-attention outputs through gating mechanisms; (iv) Transformer employs a [CLS] token mechanism to provide global sequence representation for traffic classification. Experiments demonstrate that this complementary design achieves 95.02% accuracy in Level 3 fine-grained classification.

- Proposal of a multi-objective joint optimization framework that unifies classification accuracy, hierarchical consistency, and feature diversity in an end-to-end differentiable loss function. Through carefully designed loss weights (classification 0.3/0.3/0.4, consistency 0.1, diversity 0.01), the system effectively maintains logical reasonability of predictions while optimizing the main task and prevents model degradation into single-modal dependency.

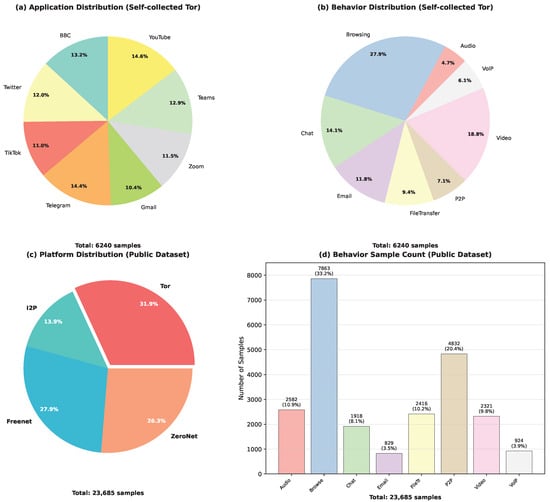

- Construction of a fine-grained Tor traffic benchmark dataset containing 6240 annotated samples across 8 behavior categories from 8 mainstream applications (BBC, Twitter, Telegram, etc.), employing a sliding window mechanism (window size 2000 packets, step size 1500 packets) to ensure completeness of traffic patterns, providing a new evaluation benchmark for Darknet traffic classification research.

The organization of this paper is as follows: Section 2 introduces related research work; Section 3 provides a formal definition of the problem and elaborates on the proposed end-to-end multi-modal classification system; Section 4 conducts experimental validation and result analysis; Section 5 concludes the paper and outlines future research directions.

2. Background and Related Work

In this section, we introduce the relevant background of the darknet and review related research in the field of machine learning-based darknet traffic classification.

2.1. Darknet

The darknet is a part of the Internet that is hidden from ordinary search engine indexing and requires special software and configuration to access. Mainstream darknet technologies include the following:

Tor network [12] is the most widely used darknet platform. It employs onion routing technology to achieve anonymous communication through three-layer encryption and multi-hop forwarding. Traffic passes through entry nodes, relay nodes, and exit nodes, with each hop only knowing the adjacent nodes before and after, making it impossible to trace the complete path. Tor supports the TCP protocol and is widely used for anonymous browsing, instant messaging, and other applications.

I2P network focuses on hidden services and employs garlic routing technology, which bundles and encrypts multiple messages together. Unlike Tor, all nodes in I2P function as both clients and routers, forming a fully distributed overlay network. I2P has built-in support for various applications, including email, file sharing, and web browsing.

Freenet is a distributed censorship-resistant storage system that uses content-based routing mechanisms. Data is encrypted, fragmented, and redundantly stored across multiple nodes, retrieved through keys. Freenet emphasizes content persistence and censorship resistance, making it suitable for publishing and retrieving static content.

ZeroNet uses Bitcoin cryptography and the BitTorrent network to create decentralized websites. Each website is a torrent file, and visitors simultaneously serve as content distributors. ZeroNet does not provide anonymity by default and typically needs to be used in conjunction with Tor.

The common characteristics of these darknet technologies—strong encryption, multi-layer forwarding, and traffic obfuscation—pose tremendous challenges for traffic classification.

2.2. Traditional Machine Learning-Based Methods

Early darknet traffic classification research primarily employed traditional machine learning methods. The core of these methods lies in feature engineering, i.e., extracting statistical features from raw traffic for classification.

In terms of feature selection, researchers have explored various approaches. Recent feature selection review studies [13] systematically summarize filtering, wrapper, and embedded feature selection paradigms. By combining the advantages of multiple algorithms [14], more stable feature subsets can be obtained. Commonly used features include packet size statistics (mean, variance, maximum, minimum), inter-packet interval time distribution, packet direction ratio, byte distribution entropy, and flow duration.

Regarding classifier selection, Random Forest [3] is widely used due to its robustness to high-dimensional features. Rust-Nguyen et al. [1] achieved 98% accuracy on the CIC-Darknet2020 dataset through optimized Random Forest. Marim et al. [4] compared the performance of decision trees and neural networks in darknet traffic detection. Gradient boosting tree methods have shown excellent performance in recent years. XGBoost [5] and LightGBM [6], as next-generation gradient boosting frameworks, have demonstrated superior performance in darknet traffic classification. Song et al. [15] proposed the CDBC method, improving XGBoost’s effectiveness in darknet detection through enhanced between-class learning. Ensemble learning methods further improve performance by combining multiple base learners. Almomani [16] proposed an improved stacking ensemble framework, achieving 99% accuracy in the training phase. Mohanty et al. [17] designed a robust stacking ensemble model that maintains stable performance in adversarial environments.

However, the main limitations of traditional methods are (1) heavy reliance on hand-crafted features, making it difficult to adapt to dynamic changes in traffic patterns; (2) inability to capture deep patterns in raw traffic; and (3) significant performance degradation on fine-grained classification tasks.

2.3. Deep Learning-Based Methods

Deep learning methods overcome some limitations of traditional methods by automatically learning feature representations. DIDarknet, proposed by Lashkari et al. [8], is a pioneering work in this field, converting traffic data into grayscale images and utilizing pre-trained ResNet-50 for classification, achieving excellent performance on binary classification tasks. The innovation of this image-based method lies in mapping temporal traffic to two-dimensional space, leveraging mature computer vision techniques.

CNN-LSTM hybrid architectures are widely applied to traffic classification. DarkDetect, proposed by Sarwar et al. [7], employs a 3-layer CNN to extract spatial features and a 2-layer LSTM to model temporal dependencies, achieving 96% and 89% accuracy on darknet detection and classification tasks respectively. This architecture combines CNN’s local feature extraction capability with LSTM’s sequence modeling ability. Other innovative deep learning architectures have also been applied to this field. FlowPic [18] provides a general traffic representation learning framework by converting network traffic into image representations. CETAnalytics [19] combines content features and statistical features, using Bi-GRU to process temporal information. DarknetSec [9] introduces self-attention mechanisms, exploring intrinsic relationships between features through multi-head attention.

2.4. Multi-Modal Traffic Classification

Recent advances in deep learning have demonstrated the effectiveness of multi-modal approaches for encrypted traffic classification. These methods leverage complementary information from different data modalities to improve classification performance.

Lin et al. [20] proposed a novel multimodal deep learning framework called PEAN for encrypted traffic classification. Their method combines packet-level and flow-level features through separate neural networks. Aceto et al. [2] developed MIMETIC, a multimodal mobile encrypted traffic classification system. It integrates data payload and protocol time-series features through deep learning models. More recently, Zhai et al. [21] introduced ODTC, an online darknet traffic classification model. It employs CNN and BiGRU to extract spatiotemporal features from payload content. ODTC also uses a multi-head attention mechanism to capture relationships between different modalities.

Despite these advances, most existing multimodal methods rely on late fusion techniques. They concatenate features from different extractors at the final stage. This approach may not fully exploit the complementary nature of multi-modal features. Our proposed method addresses this limitation through adaptive attention-based fusion. It dynamically weights different modalities based on traffic characteristics.

2.5. Hierarchical Classification Methods

Hierarchical classification has emerged as a promising approach for structured traffic classification tasks. This approach naturally aligns with the taxonomic structure of network traffic, where categories are organized in parent-child relationships.

Several recent studies have explored hierarchical classification for darknet and encrypted traffic. Hu et al. [10] proposed a hierarchical classifier for darknet traffic that distinguishes four darknet types (Tor, I2P, ZeroNet, Freenet) and 25 user behaviors. The classifier employs local classifiers at different hierarchy levels, respecting the natural taxonomic structure of darknet traffic. Montieri et al. [11] developed a hierarchical framework for anonymity tools classification, achieving fine-grained identification across multiple levels. Their work demonstrated that hierarchical approaches can effectively handle the complexity of darknet traffic patterns. More recently, Li et al. [22] proposed a hierarchical perception framework for encrypted traffic classification using class incremental learning, which addresses the challenge of continuously evolving traffic categories.

Traditional hierarchical methods often use independent classifiers at each level. This can lead to logical inconsistencies in predictions. For example, a sample may be classified as Tor at Level 1 but assigned to an I2P application at Level 2. Such violations undermine the reliability of classification results. Moreover, these methods typically employ hard decision boundaries, where each level makes a definitive classification before passing to the next level, potentially propagating errors down the hierarchy.

Our work differs from previous approaches in three key aspects. First, we introduce soft conditional mechanisms that use probability distributions from upper levels to guide lower-level classification rather than hard decisions. This allows lower levels to retain uncertainty information from upper levels. Second, we incorporate hierarchical consistency constraints into the training objective through a dedicated consistency loss term. This ensures that predictions respect predefined taxonomic relationships across all levels during both training and inference. Third, our framework employs end-to-end joint optimization of all hierarchy levels, enabling gradient information to flow across levels and facilitating better learning of hierarchical dependencies.

2.6. Summary of Existing Methods

Comprehensive analysis of existing research reveals several significant deficiencies that limit the effectiveness of current darknet traffic classification approaches. Recent survey studies [23] provide a comprehensive review of darkweb research trends and highlight the evolving challenges in this domain. First, most methods rely on single-modal features or employ simple late fusion of multiple modalities. They use only one type of feature such as statistical features or raw bytes, and thus fail to comprehensively utilize the multi-dimensional information inherent in network traffic. Second, existing methods typically focus only on single-level classification or employ independent multiple classifiers at different hierarchy levels. This potentially leads to predictions that violate hierarchical constraints and lack semantic consistency across different classification levels. Third, traditional methods require extensive expert knowledge for feature engineering. Deep learning methods, though capable of automatic learning, often focus on a single perspective and fail to capture the full complexity of darknet traffic patterns. Recent advances in mobile encrypted traffic classification [24] have demonstrated the potential of deep learning approaches, yet challenges remain in handling the diversity of darknet traffic characteristics. For instance, while machine learning-based approaches [25] have shown promise in IoT-based darknet detection systems, they remain limited by their dependence on hand-crafted features and struggle with the heterogeneity of darknet traffic across different platforms. Fourth, public datasets mostly focus on coarse-grained classification and lack application behavior-level annotations. This significantly limits research on fine-grained classification tasks. Finally, most studies prioritize accuracy while neglecting the latency requirements critical for practical deployment in real-world network monitoring scenarios.

The end-to-end multi-modal deep learning framework proposed in this paper aims to address these issues systematically. By fusing multiple feature extractors, designing conditional hierarchical classification mechanisms, and adopting end-to-end training strategies, our method not only ensures high accuracy but also meets real-time detection requirements, providing a comprehensive and practical solution for darknet traffic classification.

3. Methodology

3.1. Problem Definition

In the darknet traffic classification problem, accurate formal definition is fundamental to constructing an effective solution. This section first defines the basic notations and concepts involved in the problem, providing a unified mathematical framework for subsequent method description.

Let the raw network traffic be a continuous sequence of data packets , where each packet contains multiple attributes: timestamp , source IP address , destination IP address , protocol type , packet size , and raw payload . In practical applications, this sequence may contain interleaved packets from multiple concurrent network flows, requiring preprocessing steps for separation and organization.

Through a sliding window mechanism, we partition the continuous traffic into fixed-size windows , where each window contains k consecutive packets (in our implementation, ). For each window, we define a feature extraction function , which maps the raw packet sequence to a feature space . This feature space is multi-modal, comprising a combined representation of byte-level features, packet sequence features, temporal features, and global semantic features.

The label space for darknet traffic classification has a clear hierarchical structure. We define three levels of label spaces: represents darknet platform types (such as Tor, I2P, Freenet, ZeroNet), represents application categories (such as Twitter, Telegram, YouTube, etc.), and represents specific application behaviors (such as audio streaming, browsing, video streaming, etc.). There exist strict hierarchical constraint relationships among these three label spaces.

The hierarchical constraints are formalized through two mapping functions: : defines the Level 1 label to which each Level 2 label belongs, and : defines the Level 2 label to which each Level 3 label corresponds. These mappings ensure the logical consistency of labels. Formally, these mappings are defined as

which associates each Level 2 application with its Level 1 platform , and

which maps each Level 3 behavior to its Level 2 application . For example, on the public Darknet-2020 dataset containing multiple platforms, and , while on our self-collected Tor dataset where all applications belong to a single platform, for all . At the behavior level, and illustrate the application-to-behavior mappings.

These mappings enforce hierarchical consistency: any valid prediction must satisfy and . This constraint ensures semantic coherence across classification levels and guides the conditional dependencies in our hierarchical classifier, where level ℓ predictions are conditioned on level probability distributions through these predefined parent-child relationships. Additionally, we define a function : to identify which Level 2 categories require further Level 3 classification, as not all application categories have multiple sub-behaviors.

Based on the above definitions, the hierarchical classification task for darknet traffic can be formalized as learning a mapping function H: , which maps samples in the feature space to labels at three hierarchical levels. Unlike traditional multi-label classification, this mapping must satisfy hierarchical constraints: for any valid prediction , it must satisfy and . This constraint ensures the semantic reasonableness of prediction results.

From a probabilistic perspective, our goal is to model the conditional probability distribution , where is the input feature. Through the chain rule, this joint probability can be decomposed as

This decomposition not only simplifies the learning task but also naturally encodes hierarchical dependencies, making predictions at subsequent levels conditional on the results of preceding levels.

In practical implementation, the model realizes the above probabilistic decomposition through three conditional classifiers: the first classifier : outputs logits for Level 1 labels, the second classifier : outputs logits for Level 2 labels given the features and Level 1 predictions, and the third classifier : similarly handles Level 3 classification. This conditional design is key to achieving accurate hierarchical classification.

It is worth noting that our problem definition also considers constraints for practical deployment. The choice of window size k needs to balance detection latency and classification accuracy; the feature dimension d needs to be high enough to capture complex traffic patterns but not so high as to affect real-time processing performance. Furthermore, the hierarchical prediction structure provides flexibility: in some application scenarios, only coarse-grained Level 1 or Level 2 classification results may be needed. Our framework allows for stopping predictions at any level, providing classification services at different granularities.

3.2. System Architecture Overview

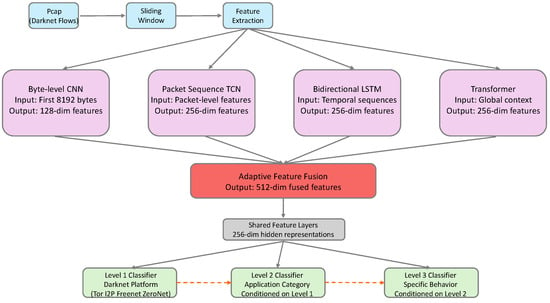

The end-to-end darknet traffic classification system proposed in this paper adopts an architectural design that combines multi-modal feature fusion with conditional hierarchical classification, aiming to learn discriminative features directly from raw network traffic and avoid tedious manual feature engineering in traditional methods. The overall system architecture is shown in Figure 1, mainly comprising four core components: the data preprocessing module, multi-modal feature extraction module, adaptive feature fusion module, and conditional hierarchical classification module.

Figure 1.

Overall architecture of the proposed E2E-MDC framework. The system processes raw network traffic through four specialized feature extractors (Byte-level CNN, Packet Sequence TCN, Bidirectional LSTM, and Transformer), adaptively fuses multi-modal features through attention mechanisms, and performs three-level hierarchical classification through conditional classifiers.

The system input is raw network traffic data in PCAP format, and the output consists of three hierarchical classification results: Level 1 (darknet type, such as Tor, I2P, etc.), Level 2 (application category, such as BBC, Twitter, TikTok, Telegram, Gmail, Zoom, Teams, YouTube, etc.), and Level 3 (specific application behavior, such as audio streaming, browsing, video streaming, etc.). This hierarchical classification system not only conforms to the natural hierarchical structure of darknet traffic but also provides threat intelligence at different granularities for network security analysis.

In terms of data flow processing, the system first segments continuous network traffic into fixed-size traffic segments through a sliding window mechanism. Each segment contains 2000 packets, with an overlap of 500 packets between adjacent segments. This design ensures sufficient contextual information while enabling near-real-time traffic detection. For each traffic segment, the system simultaneously extracts four types of features at different granularities: raw byte sequences, packet-level statistical features, temporal dependencies, and global semantic information.

Multi-modal feature extraction is one of the core innovations of this system. Unlike existing methods that focus only on a single type of feature, we designed four specialized deep neural network modules to capture different aspects of traffic features: (1) the byte-level CNN module directly processes the first 8192 raw bytes, extracting byte pattern features through multi-scale convolution; (2) the packet sequence TCN module processes sequence features such as packet size, direction, and time interval, using temporal convolutional networks to capture local temporal patterns; (3) the bidirectional LSTM module models long-range temporal dependencies, learning dynamic evolution features of traffic through gating mechanisms and self-attention mechanisms; and (4) the Transformer module understands the semantic information of the entire traffic segment from a global perspective, capturing complex interaction relationships between packets through multi-head attention mechanisms.

The feature fusion stage adopts an adaptive weighting mechanism. The system learns the importance weights of each feature module, dynamically adjusting the contribution of different modal features. This design enables the model to automatically select the most discriminative feature combinations based on different types of traffic. For example, for highly encrypted traffic where byte-level features may contain limited information, the system will automatically increase the weights of temporal and statistical features.

Finally, the conditional hierarchical classifier performs three-level classification decisions based on the fused features. Unlike traditional flat classification, our classifier explicitly models the conditional dependencies between different levels: Level 2 classification is conditioned on Level 1 prediction results, and Level 3 classification considers both Level 1 and Level 2 information. This conditional design not only improves classification accuracy but also ensures hierarchical consistency of prediction results.

The entire system adopts end-to-end training, with all modules jointly optimized through a unified loss function. The loss function contains three parts: weighted classification loss ensures classification accuracy at each level, hierarchical consistency loss maintains logical reasonableness of prediction results, and feature diversity regularization prevents different feature extractors from learning redundant information. This carefully designed training strategy enables system components to cooperate with each other and jointly improve overall performance.

It is worth noting that the system design fully considers the needs of practical deployment. Through modular architecture design, the system can be flexibly adjusted according to different application scenarios. For example, on edge devices with limited computational resources, certain feature extraction modules can be selectively disabled; in scenarios with high real-time requirements, the size and stride of the sliding window can be adjusted. This flexibility gives the system good practicality and scalability.

3.3. Data Preprocessing Pipeline

Data preprocessing is a key step in ensuring the performance of end-to-end learning systems. This section details our designed preprocessing pipeline, including the sliding window mechanism and multi-scale feature normalization strategy.

3.3.1. Sliding Window Mechanism

When processing network traffic data, a core challenge is how to handle variable-length traffic sequences. Traditional methods typically use complete flows or fixed time windows, but both approaches have obvious defects: the complete flow method requires the flow to end before classification, which cannot meet real-time detection requirements; fixed time windows may truncate important traffic patterns. To address this, we propose a sliding window mechanism based on a fixed number of packets.

Specifically, we segment continuous network traffic into windows containing 2000 packets, with an overlap of 500 packets between adjacent windows, i.e., a sliding stride of 1500 packets. The selection of window size and stride involves trade-offs among protocol characteristics, computational constraints, and real-time requirements.

From the perspective of traffic pattern characteristics, different application behaviors exhibit varying temporal spans. At the protocol level, fundamental operations such as TCP handshake and TLS negotiation typically complete within 10–50 packets. At the application level, interactive applications (e.g., browsing, chat) exhibit request-response patterns spanning 50–300 packets; streaming media applications establish stable transmission patterns over hundreds to thousands of packets; file transfer applications may require even longer observation sequences to manifest complete characteristics. Furthermore, the multi-layer encryption in darknet traffic causes behavioral patterns to become more dispersed, necessitating longer sequences to accumulate sufficient statistical features. Based on these considerations, a reasonable range for window size is approximately 1000–3000 packets.

Within this range, the specific choice requires consideration of practical system constraints. From a computational efficiency perspective, our framework incorporates a Transformer module whose self-attention mechanism has complexity; when the window size increases to 3000 packets, computational overhead increases significantly, affecting real-time processing capability. From a latency perspective, in typical gigabit network environments, 1000–2000 packets correspond to approximately 1–3 s of traffic accumulation, meeting real-time monitoring requirements, whereas exceeding 2500 packets may result in excessive detection delay. From a feature completeness perspective, our preliminary experiments indicate that windows of 1500–2000 packets adequately capture behavioral characteristics for the eight categories of interest (browsing, chat, file transfer, P2P, audio/video streaming, VoIP), with diminishing performance gains from further window enlargement.

Considering these factors comprehensively, we select 2000 packets as the window size for this study. This choice performs well on our datasets, though we note that other window sizes (e.g., 1500 or 2500) may be equally or more effective under different application scenarios or network conditions.

To prevent critical behavioral patterns from being truncated at window boundaries, we introduce overlap between adjacent windows, setting the stride to 1500 packets (i.e., 25% overlap). This configuration is based on the following trade-offs: moderate overlap ensures that patterns spanning boundaries can be captured more completely in at least one window, while avoiding redundant computation from excessive overlap. This parameter setting works well in our experiments but can be adjusted according to specific requirements—latency-sensitive scenarios may reduce overlap, while scenarios demanding extreme accuracy may increase it.

The sliding window implementation also considers boundary case handling. For traffic segments with fewer than 2000 packets, we adopt a zero-padding strategy, filling insufficient parts with zero values while maintaining the original packet order. This processing ensures consistency of model input while allowing the model to identify the actual number of valid packets through packet count features.

This sliding window mechanism provides a principled approach to partitioning variable-length traffic streams while balancing pattern completeness and real-time performance.

3.3.2. Feature Normalization Strategy

Raw network traffic data contains multiple types of features with vastly different numerical ranges. Direct input to neural networks would lead to training instability. Therefore, we designed corresponding normalization strategies for different types of features.

Timestamp normalization is one of the most critical steps in preprocessing. The timestamps in raw PCAP files are absolute Unix times, and direct use would cause the model to overfit specific time periods. We convert all timestamps to relative times, using the first non-zero timestamp in each window as the reference point. The specific calculation formula is

This normalization method maps all timestamps to the [0, 1] interval, making the model focus on inter-packet time interval patterns rather than absolute time.

Byte sequence normalization processes raw byte data. We extract the first 8192 bytes of each traffic window as byte-level features, dividing each byte value by 255 to map to the [0, 1] interval. This simple linear normalization preserves the relative relationships between byte values, enabling the byte-level CNN to effectively learn protocol features and encryption patterns.

Packet size normalization considers the physical limitations of Ethernet. Since the Ethernet MTU is typically 1500 bytes, we normalize all packet sizes by dividing by 1500. For jumbo frames, the normalized value may be slightly larger than 1, but this situation is rare and does not significantly affect model training.

Time interval normalization adopts logarithmic scale transformation. The distribution of inter-packet time intervals in network traffic is extremely uneven, spanning multiple orders of magnitude from microseconds to seconds. Direct normalization would compress the differences between small intervals. We adopt the following logarithmic normalization strategy:

This transformation maps time intervals to the [0, 1] interval while preserving the discrimination of intervals at different scales.

Protocol feature processing includes TCP flags, window size, IP flags, and TTL. TCP flags and IP flags maintain their original integer encoding and are input to the embedding layer as categorical features. TCP window size is normalized by dividing by 32,768 (). TTL values maintain their original range [0, 255], as different TTL values inherently have categorical feature characteristics.

Direction feature encoding is used to distinguish the bidirectionality of traffic. We use the source IP of the first packet in each window as the client standard, marking subsequent packets as client-to-server (+1), server-to-client (), or retransmission in the same direction (0). This encoding method is simple and effective, capable of capturing traffic interaction patterns.

Additionally, we implemented data augmentation strategies to improve the model’s generalization ability. Augmentation operations include (1) time shifting: adding random perturbations of −10% to +10% to time-related features; (2) packet size perturbation: adding 5% Gaussian noise to simulate network jitter; (3) random packet loss: randomly setting certain packet features to zero with a probability of 5–15%, simulating network packet loss; and (4) byte sequence noise: adding 2% uniform noise to raw bytes, enhancing the model’s robustness to slight content changes.

All preprocessing operations are carefully designed to ensure that while improving model training stability, key information in the original traffic is not lost. The preprocessed data is input to subsequent feature extraction modules in standardized tensor format, laying a solid foundation for end-to-end learning.

3.4. Multi-Modal Feature Extraction

Multi-modal feature extraction is the core innovation of this system, capturing features of darknet traffic from different perspectives through four specially designed deep neural network modules. Each module is optimized for specific types of information, collectively forming a comprehensive feature representation system.

3.4.1. Byte-Level CNN Module

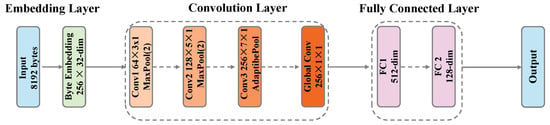

The byte-level CNN module directly processes the byte sequence of raw traffic, aiming to automatically learn protocol features, encryption patterns, and application fingerprints. The module input is the first 8192 bytes of each traffic window, and the output is a 128-dimensional feature vector. This design draws on the idea of Network in Network [26].

The first layer of the module is a byte embedding layer, mapping each byte (0–255) to a 32-dimensional dense vector space. This embedding representation is more compact than one-hot encoding and can learn semantic similarity between bytes. For example, bytes within the ASCII character range may be mapped to similar embedding spaces, while random bytes of encrypted data are distributed more uniformly. The byte-level CNN architecture is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Architecture of the byte-level CNN module. The module processes 8192 raw bytes through embedding layer, three multi-scale convolutional blocks, and fully connected layers to extract 128-dimensional byte pattern features.

The core feature extraction adopts a three-layer multi-scale convolution structure:

The first convolution layer uses 64 convolution kernels, combined with batch normalization and ReLU activation function, mainly capturing local patterns between adjacent bytes. This layer is followed by max pooling, halving the sequence length to 4096. This design can effectively identify short-range protocol identifiers and fixed header patterns.

The second convolution layer uses 128 convolution kernels, with a receptive field expanded to 5 bytes, capable of capturing longer byte patterns such as HTTP request methods and TLS handshake messages. Similarly using batch normalization, ReLU activation, and max pooling, the sequence length is further reduced to 2048.

The third convolution layer uses 256 convolution kernels with a larger receptive field for capturing complex patterns of application layer protocols. This layer is followed by adaptive max pooling, uniformly compressing feature sequences of different lengths to a fixed length of 64, ensuring consistency in subsequent processing.

After multi-scale convolution, we add a global convolution layer using 256 convolution kernels to transform features at each position. This design draws on the idea of Network in Network, enhancing the model’s nonlinear expressive power.

Finally, the extracted features are projected to a 128-dimensional output space through a two-layer fully connected network. The first fully connected layer maps the flattened = 16,384-dimensional features to 512 dimensions, combined with batch normalization, ReLU activation, and 0.2 dropout to prevent overfitting. The second fully connected layer outputs the final 128-dimensional feature representation.

3.4.2. Packet Sequence Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN)

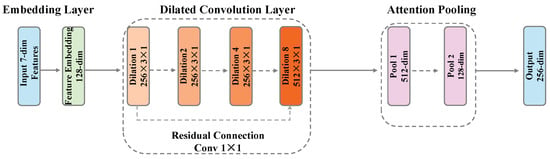

The packet sequence TCN module [27] specifically processes packet-level statistical feature sequences, including 7-dimensional features such as packet size, direction, time interval, TCP flags, window size, IP flags, and TTL. The module adopts a temporal convolutional network architecture and outputs a 256-dimensional feature vector. The packet sequence TCN architecture is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Architecture of the packet sequence TCN module. The module employs dilated causal convolutions with exponentially growing dilation rates (1, 2, 4, 8) to capture multi-scale temporal patterns from packet sequences.

Feature embedding is the first step of this module. Different types of features adopt different embedding strategies: continuous value features (packet size, time interval, window size) are mapped to 32-dimensional spaces through linear transformation respectively; discrete features (direction, TCP flags, IP flags, TTL) learn their semantic representations through embedding layers. All embedded features are concatenated into a unified 128-dimensional representation.

The core TCN structure adopts 4 layers of dilated convolution with dilation rates of 1, 2, 4, and 8 respectively. This exponentially growing dilation rate enables the network to obtain a large receptive field with fewer layers. The design of each layer is as follows:

- Layer 1: 256 convolution kernels, dilation rate 1, capturing direct relationships between adjacent packets

- Layer 2: 256 convolution kernels, dilation rate 2, capturing patterns with 1-packet intervals

- Layer 3: 256 convolution kernels, dilation rate 4, capturing larger-range temporal patterns

- Layer 4: 512 convolution kernels, dilation rate 8, capturing long-range dependencies

Each layer includes batch normalization, ReLU activation, and 0.1 dropout. To address the vanishing gradient problem, we add residual connections between Layer 1 and Layer 4, projecting the 128-dimensional input to 512 dimensions through convolution and adding it to the Layer 4 output.

An innovation point of this module is the attention pooling mechanism. Traditional global average pooling or max pooling may lose important local information. We designed a two-layer attention network: the first layer compresses 512-dimensional features to 128 dimensions and uses Tanh activation, and the second layer outputs 1-dimensional attention scores. After Softmax normalization, these scores serve as weights to perform weighted summation of features at different time steps, obtaining the final 512-dimensional aggregated features. Finally, the 256-dimensional packet sequence feature representation is output through linear projection.

3.4.3. Bidirectional LSTM with Attention Module

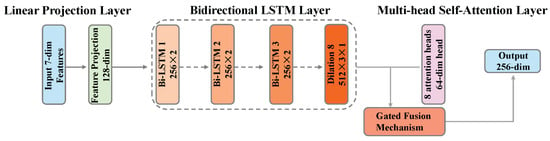

The bidirectional LSTM module focuses on modeling the temporal dynamic characteristics of traffic, particularly long-range dependencies in packet sequences. This module also takes 7-dimensional packet-level features as input and outputs a 256-dimensional feature vector. The bidirectional LSTM architecture is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Architecture of the bidirectional LSTM module. The module processes packet sequences through 3-layer bidirectional LSTM, applies multi-head self-attention, and fuses features through a gating mechanism.

Input features are first expanded to 128 dimensions through a linear projection layer, providing richer input representation for LSTM. The core network is a 3-layer bidirectional LSTM with a hidden dimension of 256 in each direction, totaling 512 hidden dimensions. Using multi-layer LSTM can learn more complex temporal patterns, while the bidirectional structure allows the model to utilize both past and future contextual information simultaneously. Inter-layer dropout is set to 0.2 to prevent overfitting.

Based on LSTM output, we introduce a self-attention mechanism to further refine features. Specifically, 8-head attention is used, with each head focusing on a 64-dimensional subspace. This multi-head design allows the model to focus on different parts of the sequence from different angles. Attention calculation follows the standard scaled dot-product attention formula with 0.1 dropout added to improve generalization.

A key innovation is the gated fusion mechanism. LSTM output and attention output are adaptively fused through a gating network. The gating network generates 512-dimensional gate values through a linear layer and Sigmoid activation function on the concatenated 1024-dimensional features (512-dimensional LSTM + 512-dimensional attention), controlling the mixing ratio of the two types of features:

where g represents the gate values and ⊙ denotes element-wise multiplication. This design enables the model to adaptively choose to rely on LSTM’s temporal modeling or attention’s global correlation based on input characteristics.

The final feature representation is obtained through two methods: one is the hidden state at the last time step of LSTM (considering bidirectionality, concatenating the final hidden states of forward and backward directions), and the other is average pooling of fused features at all time steps. After averaging the two, they are projected to the 256-dimensional output space through a multi-layer perceptron containing batch normalization, ReLU, and dropout.

3.4.4. Transformer Global Feature Extractor

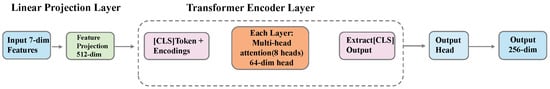

The Transformer module understands the semantic information of the entire traffic window from a global perspective, capturing complex interaction relationships between packets through self-attention mechanisms. This module also processes 7-dimensional packet features and outputs a 256-dimensional feature vector. The Transformer architecture is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Architecture of the Transformer module. The module introduces a [CLS] token to aggregate global information and processes the sequence through 6 Transformer encoder layers with multi-head self-attention.

The input 7-dimensional features are first expanded to the 512-dimensional model dimension () through linear projection. Unlike the standard Transformer, we use learnable positional encoding rather than fixed sinusoidal encoding, allowing the model to adaptively learn positional patterns in darknet traffic. Positional encoding is a learnable parameter with shape [1, 2000, 512], added directly to the input embeddings.

The adoption of learnable positional encoding is a deliberate design choice motivated by the unique characteristics of encrypted network traffic classification. This approach offers three key advantages over fixed sinusoidal encoding.

First, domain-specific adaptivity: Learnable encoding enables the model to discover and represent the temporal patterns inherent in darknet traffic through end-to-end training. Encrypted network packets exhibit irregular timing distributions, protocol-specific ordering patterns, and burst transmission behaviors that differ fundamentally from the sequential structures found in natural language or other domains where fixed sinusoidal encoding was originally designed. By parameterizing the positional embeddings as learnable weights, the model can adapt to these domain-specific characteristics rather than imposing predetermined periodic patterns.

Second, task-driven optimization: Through joint training with the hierarchical classification objective, the learnable positional embeddings are optimized to encode position information that is most discriminative for distinguishing darknet applications and behaviors. This end-to-end learning allows the model to automatically identify which positional features are relevant for classification while discarding irrelevant temporal variations. The gradient flow from classification loss directly shapes the positional representations, ensuring they contribute effectively to the final prediction rather than serving as generic position markers.

Third, multi-scale temporal modeling: Darknet traffic patterns manifest across multiple temporal scales—from microsecond-level inter-packet intervals to second-level session dynamics. Learnable encoding provides the flexibility to adaptively weight different temporal granularities based on their relevance to each hierarchical classification level. For instance, fine-grained Level 3 behavior classification may rely more heavily on short-range temporal patterns, while Level 2 application identification may benefit from longer-range dependencies. The learnable nature of positional embeddings allows such task-specific temporal focusing to emerge naturally during training.

Furthermore, the learnable encoding maintains compatibility with the overall architecture’s differentiability, enabling seamless gradient backpropagation throughout the entire model. This is particularly important for our conditional hierarchical classification framework, where optimization signals must flow across multiple classification levels and feature modalities.

To enhance the model’s perception of different stages of traffic, we introduce a segment embedding mechanism. The sequence of 2000 packets is divided equally into three segments, the beginning segment (first 667 packets), middle segment (668–1334 packets), and ending segment (last 666 packets), each identified with different segment embedding vectors. This design helps the model distinguish different stages of traffic, such as handshake phase, data transmission phase, and termination phase.

The [CLS] token mechanism is a key innovation of this module. Drawing on the design idea of BERT [28], we add a special [CLS] (Classification) token at the beginning of each input sequence. This token is a learnable parameter vector, initialized as a 512-dimensional random vector, consistent with the model dimension.

The design of the [CLS] token has several important considerations:

First, it provides a dedicated “anchor point” to aggregate global information. During self-attention computation, the [CLS] token can interact with all packets in the sequence, but it does not carry information about any specific packet itself, thus being able to neutrally learn the global representation of the entire sequence. This is particularly important for darknet traffic classification, as judging traffic type often requires comprehensive consideration of the entire communication pattern rather than local features.

Second, through 6-layer Transformer encoding, the [CLS] token aggregates information layer by layer. In shallow layers, it mainly focuses on local patterns between adjacent packets; in deep layers, as the receptive field expands, it can capture more complex global interaction patterns. The self-attention mechanism at each layer allows the [CLS] token to selectively focus on different parts of the sequence based on the current representation.

In specific implementation, the input sequence is expanded from the original [batch_size, 2000, 512] to [batch_size, 2001, 512], where position 0 is the [CLS] token. When applying positional encoding, we assign position 0 to the [CLS] token, and the positions of the original sequence are shifted backward accordingly. This processing ensures continuity of positional information.

The core Transformer encoder contains 6 layers, each consisting of multi-head self-attention and feed-forward network. Specific configuration is as follows:

- Number of attention heads: 8;

- Dimension per head: 64 (total 512 dimensions);

- Feed-forward network dimension: 2048;

- Activation function: GELU;

- Dropout rate: 0.1.

In self-attention computation, the [CLS] token participates in all attention calculations. It both attends to other positions as a query and is attended to by other positions as key and value. This bidirectional interaction enables the [CLS] token to effectively integrate global information. In particular, since darknet traffic often contains encrypted content, individual packet information may be limited, but the overall pattern of packet sequences (such as packet size distribution, time interval regularity, etc.) can reveal application types. The [CLS] token is the ideal carrier for capturing such overall patterns.

After 6 layers of encoding, we extract the output at the [CLS] position (i.e., position 0) as the representation of the entire sequence. This 512-dimensional vector contains the Transformer’s understanding of the traffic window from a global perspective. Compared to simple average pooling or max pooling, the [CLS] token provides a more flexible and powerful sequence representation method.

The final output head is a two-layer network containing layer normalization, ReLU activation, and dropout. The first layer maintains 512 dimensions for feature transformation and regularization; the second layer projects the dimension to 256 dimensions, consistent with the output of other feature extraction modules. This design ensures feature compatibility, facilitating subsequent multi-modal fusion.

It is worth noting that although the computational complexity of Transformer is high ( relative to sequence length), in our application scenario, the fixed window size of 2000 packets makes the computational cost controllable. Meanwhile, the [CLS] token mechanism avoids the need to pool outputs at all positions, improving computational efficiency.

The four feature extraction modules capture features of darknet traffic from different perspectives: the byte-level CNN focuses on underlying protocol and encryption patterns, the packet sequence TCN extracts local temporal patterns, the bidirectional LSTM models long-range dependencies, and the Transformer provides global semantic understanding through the [CLS] token. This multi-modal design ensures feature comprehensiveness and complementarity, providing a rich information foundation for subsequent classification tasks.

3.5. Adaptive Feature Fusion

The adaptive feature fusion module is the key bridge connecting multi-modal feature extraction and conditional hierarchical classification. This module does not simply concatenate features from different modalities but learns the importance of each modality through attention mechanisms and captures interactions between modalities through cross-attention, ultimately generating a unified 512-dimensional feature representation.

3.5.1. Attention-Driven Weighting Mechanism

The first step of feature fusion is projecting features from four different modalities into a unified representation space. Although the byte-level CNN outputs 128 dimensions and the other three modules output 256 dimensions, their semantic spaces differ. Through independent linear projection layers, we map all features to a shared 256-dimensional space:

- Byte features: dimensions (expansion projection);

- TCN features: dimensions (semantic alignment);

- LSTM features: dimensions (semantic alignment);

- Transformer features: dimensions (semantic alignment).

This projection not only unifies dimensions but more importantly learns a shared semantic space, enabling features from different modalities to be compared and fused at the same scale.

Next is the calculation of attention weights. We designed a two-layer attention network to learn the importance of each modality. First, the four projected features are concatenated into a 1024-dimensional vector and input to the first fully connected network (), using Tanh activation function to introduce nonlinearity. The second layer () outputs four scalar values, corresponding to the importance scores of the four modalities.

The key insight of this design is that different types of darknet traffic may depend on different feature modalities. For example,

- For highly encrypted traffic, byte-level features may contain limited information, making temporal features more important.

- For applications with obvious interaction patterns (such as chat), LSTM and Transformer features may be more discriminative.

- For streaming media applications, statistical features of packet sequences (TCN) may be most critical.

Through Softmax normalization, the four importance scores are converted into a probability distribution totaling 1, serving as weights for each modality. Each modality’s feature vector is multiplied by its corresponding weight to obtain weighted feature representations. This soft selection mechanism is more flexible than hard feature selection, allowing the model to dynamically adjust its dependence on different modalities based on input.

3.5.2. Cross-Modal Attention Mechanism

Simply weighting and summing features ignores potential complex interaction relationships between modalities. To address this, we introduce a cross-attention mechanism that allows features from different modalities to mutually enhance each other.

In specific implementation, we stack the four weighted feature vectors into a tensor with shape [batch_size, 4, 256], where 4 represents the number of modalities. This tensor is input to a multi-head attention layer with the following configuration:

- Embedding dimension: 256;

- Number of attention heads: 8;

- Dimension per head: 32;

- Dropout rate: 0.1.

In this cross-attention computation, features from each modality serve both as queries to attend to other modalities and as keys and values to be attended to by other modalities. This mechanism allows the model to learn complementary relationships between modalities. For example,

- Byte-level features may gain global context by attending to Transformer features;

- LSTM features may enhance understanding of local patterns by attending to TCN features;

- Transformer features may refine identification of specific protocols by attending to byte-level features.

The output of cross-attention maintains the shape [batch_size, 4, 256], containing feature representations enhanced through inter-modal interaction. These features not only retain unique information from each modality but also incorporate complementary information from other modalities.

Finally, the output of cross-attention is flattened into a 1024-dimensional vector and input to a three-layer fully connected network for final feature fusion:

- First layer: dimensions, with batch normalization, ReLU activation, and 0.3 dropout.

- Second layer: dimensions, with batch normalization, ReLU activation, and 0.2 dropout.

- Third layer: dimensions, outputting the final fused features.

This multi-layer perceptron not only completes dimension transformation but more importantly learns a nonlinear feature combination function that can capture high-order interactions between different modal features. Higher dropout rates (0.3 and 0.2) ensure that the model does not overly depend on specific feature combinations, improving generalization ability.

The fused 512-dimensional feature vector contains comprehensive information from four modalities, both retaining the unique contribution of each modality and achieving adaptive feature selection and interaction through attention mechanisms. This unified representation will be sent to the conditional hierarchical classifier to complete the final classification task.

An important characteristic of the entire fusion process is end-to-end learnability. Attention weights, cross-attention parameters, and fusion network are all jointly optimized through backpropagation, enabling the fusion strategy to automatically adapt to different data distributions and classification tasks. Meanwhile, attention weights generated during the fusion process also provide important clues for model interpretability, helping us understand from which modalities the discriminative features of different types of traffic mainly come.

3.6. Conditional Hierarchical Classifier

The conditional hierarchical classifier is the core component for achieving precise three-level classification in this system. Unlike traditional flat classification or independent multi-task learning, this classifier explicitly models the conditional dependencies between the three classification levels, ensuring prediction results are both accurate and comply with hierarchical logic.

3.6.1. Hierarchical Structure Design

The classifier input is a 512-dimensional feature vector from the feature fusion module, and it needs to simultaneously output classification results at three levels: Level 1 (darknet type), Level 2 (application category), and Level 3 (specific behavior). Our hierarchical architecture includes a shared feature extraction layer and three conditioned classification heads.

The shared feature extraction layer is responsible for further extracting high-level semantic representations related to classification tasks from fused features. This layer consists of two fully connected blocks:

- First fully connected block: dimensions, followed by batch normalization, ReLU activation, and 0.3 dropout. This layer compresses fused features to a more compact representation space while preventing overfitting through higher dropout rates.

- Second fully connected block: dimensions, also equipped with batch normalization, ReLU activation, and 0.3 dropout. This layer further refines features while maintaining dimensionality, learning representations more suitable for hierarchical classification.

The design of the shared layer is based on the assumption that although the three-level classification tasks are different, they share certain fundamental discriminative features. Through shared feature extraction, the model can more effectively utilize limited training data while ensuring consistency of predictions at different levels.

The Level 1 classification head is the simplest because it does not depend on information from other levels. This classification head contains two layers:

- First layer: dimensions, batch normalization + ReLU + 0.3 dropout;

- Second layer: dimensions, outputting classification logits for Level 1.

In our experiments, Level 1 includes 4 classes (Tor, I2P, Freenet, ZeroNet) or 1 class (only self-collected Tor data). This layer mainly identifies the type of darknet technology used.

The innovation of the Level 2 classification head lies in its conditioning on Level 1 prediction results. Specifically, Level 1 output logits are converted to probability distribution through Softmax and then concatenated with shared features to form conditional features of dimensions. This design enables Level 2 predictions to consider Level 1 uncertainty:

- Input: [Shared features (256 dim), Level 1 probabilities ( dim)];

- First layer: dimensions, batch normalization + ReLU + 0.3 dropout;

- Second layer: dimensions, outputting classification logits for Level 2.

Using probabilities rather than hard classification results as conditions has two advantages: first, it retains the uncertainty information from Level 1 predictions; second, it makes the entire network end-to-end trainable, allowing gradients to backpropagate through the Softmax operation to Level 1.

The Level 3 classification head further extends the conditionalization idea by simultaneously considering Level 2 prediction results:

- Input: [Shared features (256 dim), Level 2 probabilities ( dim)];

- First layer: dimensions, batch normalization + ReLU + 0.3 dropout;

- Second layer: dimensions, outputting classification logits for Level 3.

This cascaded conditional design ensures hierarchical consistency of predictions. For example, if Level 2 predicts “Youtube”, Level 3 is more likely to predict “video” rather than “filetransfer” or “browsing”.

3.6.2. Conditional Probability Modeling

From a probabilistic perspective, our hierarchical classifier is actually modeling the joint probability distribution , where X is the input feature and are labels at three levels, respectively. Through conditional decomposition, we express it as

This decomposition not only conforms to the natural structure of hierarchical labels but also simplifies the learning task. Each classification head only needs to learn the corresponding conditional probability distribution rather than directly learning the complex joint distribution.

In implementation, conditional dependencies are embodied through the following ways:

- Feature-level conditioning: Classification heads at subsequent levels receive the probability distribution from the previous level as additional input, providing explicit conditional information.

- Implicit regularization: Through the shared feature extraction layer, classification heads at different levels are softly constrained, encouraging them to learn consistent representations.

- Loss function constraints: During training, we not only optimize classification accuracy at each level but also ensure predictions conform to predefined hierarchical structure through hierarchical consistency loss (detailed in Section 3.7).

3.6.3. Inference Strategy

During the inference stage, the classifier adopts a top-down prediction strategy:

Step 1: Level 1 Prediction. First obtain the darknet type prediction through the Level 1 classification head. Let the input feature be x, and shared feature be , then

Step 2: Level 2 Conditional Prediction. Concatenate Level 1 probability distribution with shared features and input to Level 2 classification head:

Step 3: Level 3 Conditional Prediction. Similarly, use Level 2 probability distribution:

An important characteristic of this inference strategy is uncertainty propagation. When Level 1 prediction is uncertain (such as when the probability distribution is relatively uniform), this uncertainty is transmitted through the probability vector to Level 2, making its prediction more cautious. This is valuable in practical applications as it can identify difficult-to-classify boundary cases.

Another advantage is computational efficiency. Although we have three classification heads, shared features only need to be computed once, and each classification head is relatively lightweight. In our implementation, the computational overhead of the entire classification process is only slightly higher than a single three-way classifier.

Additionally, this architecture supports partial hierarchical prediction. In some application scenarios, only Level 1 or Level 1 + Level 2 prediction results may be needed. Our design allows predictions to be stopped at any level, providing flexible deployment options.

The conditional hierarchical classifier achieves accurate three-level classification through carefully designed architecture and inference strategy while ensuring hierarchical consistency of prediction results. This design is particularly suitable for darknet traffic classification tasks because strong dependencies indeed exist between labels at different levels, and our method can effectively utilize this structural information to improve classification performance.

3.7. Loss Function Design

The design of the loss function is crucial for end-to-end learning systems, as it not only guides the model to learn accurate classification boundaries but also ensures coordinated optimization of all system components. The loss function proposed in this paper consists of three carefully designed components: weighted classification loss, hierarchical consistency loss, and feature diversity regularization. This multi-objective optimization strategy enables the model to maintain hierarchical logical reasonability of predictions while ensuring classification accuracy and fully utilize the complementarity of multi-modal features.

3.7.1. Weighted Classification Loss

Weighted classification loss is the basic component of the entire loss function, responsible for optimizing classification accuracy at three levels. Considering that different levels have different classification difficulties and importance, we assign different weights to each level. In actual implementation, the weights for Level 1, Level 2, and Level 3 are set to 0.3, 0.3, and 0.4 respectively. This configuration reflects our emphasis on fine-grained classification (Level 3) while ensuring that coarse-grained classifications (Level 1 and Level 2) are also sufficiently trained.

This weight configuration reflects two design considerations: first, Level 3 behavior classification is more challenging than Level 1 platform or Level 2 application identification due to subtle distinctions under encryption, warranting higher weight (); second, equal weighting for Level 1 and Level 2 () ensures reliable conditional information for the hierarchical classifier, as upper-level predictions serve as inputs for lower levels.

The specific values were determined through preliminary validation experiments, demonstrating effective balance between Level 3 optimization and foundational level performance. Comprehensive ablation of loss weights is beyond the scope of this work, as our focus is on the conditional hierarchical mechanism and multi-modal fusion strategy.

The classification loss at each level adopts cross-entropy loss function with label smoothing. Label smoothing is an effective regularization technique [29] that prevents the model from being overconfident by reducing the probability of the true label from 1.0 to (where in this paper) and uniformly distributing to other classes, thereby improving generalization ability. This is particularly important in darknet traffic classification because some traffic samples may simultaneously have features of multiple classes, and completely hard labels may be too absolute.

For a single sample, the classification loss at level ℓ () is defined as

where is the smoothed label probability for class i at level ℓ, is the predicted probability, and is the number of classes at level ℓ. With label smoothing, the smoothed label is

The calculation of classification loss considers the class imbalance problem. Darknet traffic datasets typically suffer from severe class imbalance, with some application types (such as browsing) having far more samples than others (such as VoIP). Although we use a balanced sampler during data loading, we still retain the option of class weighting in loss calculation to provide additional safeguards for extreme imbalance situations.

The total weighted classification loss is computed as

where , , and are the weights for the three levels.

3.7.2. Hierarchical Consistency Loss

Hierarchical consistency loss is one of the innovative contributions of this paper, aiming to ensure that predictions at three levels conform to predefined hierarchical structure. In darknet traffic classification, there are clear inclusion relationships between labels at different levels: specific Level 2 categories can only appear under specific Level 1 categories, and similarly, specific Level 3 categories can only correspond to specific Level 2 categories. Predictions that violate this hierarchical relationship are not only logically unreasonable but also cause confusion in practical applications.

Hierarchical consistency loss is implemented through soft constraints. For each training sample, we first obtain prediction probability distributions at three levels. Then, based on predefined hierarchical mapping relationships (: Level 2 to Level 1 mapping, and : Level 3 to Level 2 mapping), we calculate the consistency degree of predictions. Specifically, if the model predicts a high probability for a certain Level 2 class for a sample, the prediction probability for its corresponding Level 1 parent class should also be correspondingly high.

The hierarchical consistency loss between Level 2 and Level 1 is defined as

where is the predicted probability for Level 2 class j, and is the predicted probability for its corresponding Level 1 parent class.

Similarly, the hierarchical consistency loss between Level 3 and Level 2 is

The total hierarchical consistency loss is

In implementation, we use mean squared error (MSE) to measure this consistency. For each Level 2 category prediction, we check the prediction probability of its corresponding Level 1 parent category and calculate the difference between them. This soft constraint is more flexible than hard logical rules, allowing the model to maintain certain prediction diversity in uncertain situations while maintaining hierarchical consistency overall.

The weight of hierarchical consistency loss is set to . This relatively small weight ensures that it serves as an auxiliary objective without excessively interfering with the main classification task. During training, we observed that this loss term has significant effect in the early training phase, helping the model quickly learn hierarchical structure; in later stages, when the model has internalized the hierarchical relationships, its value is usually very small, mainly serving a maintenance role.

3.7.3. Feature Diversity Regularization

Feature diversity regularization is an innovative loss term designed for multi-modal fusion. A common problem in multi-modal learning is that different feature extractors may learn similar or redundant representations, which not only wastes model capacity but may also lead to overfitting. Feature diversity regularization addresses this problem by encouraging different modalities to learn complementary features.

This loss term is based on attention weights in the feature fusion module. Ideally, if all four feature extractors (byte-level CNN, packet sequence TCN, bidirectional LSTM, and Transformer) learn valuable and complementary features, the attention weights during fusion should be relatively balanced. Conversely, if the weight of a certain modality approaches 1 while others approach 0, it indicates that the model overly depends on a single modality and does not fully utilize the advantages of multi-modality.

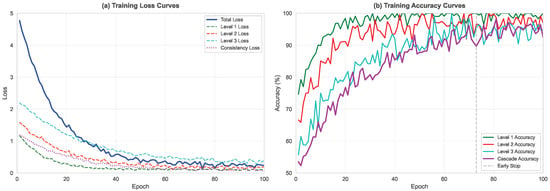

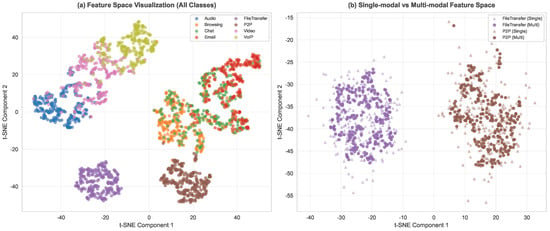

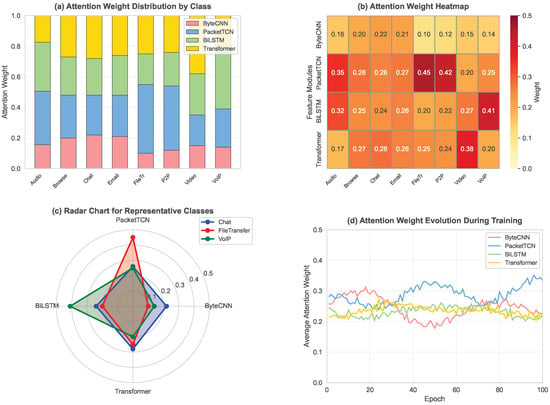

We use KL divergence to measure the difference between the actual attention distribution and uniform distribution. Let = denote the attention weights for the four modalities (where ), and denote the uniform distribution. The feature diversity regularization is defined as