Abstract

Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) reports are essential resources for identifying the Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs) of hackers and cyber threat actors. However, these reports are often lengthy and unstructured, which limits their suitability for automatic mapping to the MITRE ATT&CK framework. This study designs and compares five hybrid classification models that combine statistical features (TF-IDF), transformer-based contextual embeddings (BERT and ModernBERT), and topic-level representations (BERTopic) to automatically classify CTI reports into 12 ATT&CK tactic categories. Experiments using the rcATT dataset, consisting of 1490 public threat reports, show that the model integrating TF-IDF and ModernBERT achieved a micro-precision of 72.25%, reflecting a 10.07-percentage-point improvement in detection precision compared with the baseline. The model combining TF-IDF and BERTopic achieved a micro F0.5 of 67.14% and a macro F0.5 of 63.20%, demonstrating balanced performance across both frequent and rare tactic classes. These findings indicate that integrating statistical, contextual, and semantic representations can improve the balance between precision and recall while enabling clearer interpretation of model outputs in multi-label CTI classification. Furthermore, the proposed model shows potential applicability for improving detection efficiency and reducing analyst workload in Security Operations Center (SOC) environments.

Keywords:

adversary emulation; cyber threat intelligence (CTI); cyber threat reports (CTRs); CTI automation; BERT; ModernBERT; TF-IDF; BERTopic; natural language processing (NLP); MITRE ATT&CK; Security Operations Center (SOC); sliding window; multi-label classification; F0.5 score; threat report automation 1. Introduction

As digital transformation accelerates, cyber threats are becoming increasingly diverse and sophisticated [1]. In particular, Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) attacks targeting critical industries such as government agencies, financial institutions, and manufacturing cause massive data breaches and significant economic losses, seriously threatening national security and social trust [2]. In this complex threat landscape, the importance of Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) is more critical than ever [3]. CTI goes beyond simple event detection, playing an essential role in structurally understanding attackers’ Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs) and establishing proactive defence strategies based on this understanding [4]. In this process, Cyber Threat Reports (CTRs) function as the most critical source of data [5]. CTRs are documents published by security firms, research institutions, and government organizations after analyzing actual attack cases. They contain multi-layered information, including the attacker’s intent, penetration methods, scale of damage, and response strategies [6]. Crucially, CTRs provide strategic patterns and tactical clues that are difficult to discern from simple log data or event alerts, as they describe attacker behaviour in concrete detail within diverse contexts [7,8].

Therefore, CTRs are both the starting point for CTI automation research and a vital basis for practical decision-making in Security Operations Centres (SOCs) [9]. However, the sheer volume and unstructured narrative nature of CTRs make it difficult to perform automated analysis [10]. Traditional analysis methods typically involved security experts manually reviewing reports or relying on keyword-based tools. This approach consumes excessive time and human resources and struggles to fully extract the attackers’ inherent tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) embedded within the reports [4]. Furthermore, low compatibility with systematic threat knowledge frameworks like MITRE ATT&CK limited the utilization of CTR information as structured, standardized CTI assets. Recent advancements in Natural Language Processing (NLP) have opened possibilities for automated CTR analysis [11].

Pre-trained language models like BERT, with their strength in contextual meaning understanding, can be applied to document classification and threat actor identification within cyber threat reports [12]. However, existing BERT models face challenges: their input length constraint (maximum 512 tokens) makes fully processing long reports difficult, and their classification performance across multiple tactic categories is unstable [13]. To overcome these limitations, this study designed and compared five models performing MITRE ATT&CK tactic-level classification on CTRs [14].

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- We proposed a sliding window-based ModernBERT approach to process long CTRs without information loss [14].

- We developed a hybrid feature strategy that concatenates TF-IDF, ModernBERT embeddings, and BERTopic topic vectors to form a unified input representation for classification [15,16].

- Through comparative experiments against existing baselines and state-of-the-art NLP-based techniques, we demonstrated significant improvements in precision and F0.5 metrics [9,17].

- We demonstrated the practical applicability of our findings for CTI automation and adversary emulation scenarios based on MITRE ATT&CK [18,19].

2. Literature Review

Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) has evolved into a core domain for identifying attackers’ Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs) and preventing threats based on this knowledge [3]. Cyber Threat Reports (CTRs) serve as critical source data, containing actual attack narratives, technical indicators, and response strategies, thereby providing the foundation for CTI automation research [4]. CTRs hold high value for both academic research and practical application because they contain strategic context and tactical clues that are difficult to extract from simple logs or event data [8]. However, CTRs are typically lengthy and composed of unstructured narratives, presenting significant challenges for automated analysis [10,20].

2.1. Traditional Text Mining-Based Research

Early CTI automation research was based on traditional vectorization techniques such as TF-IDF (Term Frequency–Inverse Document Frequency) [4,6]. Legoy et al. (2020) formally introduced the rcATT dataset, presenting a multi-label problem that classifies public threat reports into MITRE ATT&CK tactic units [4]. While this approach, combining TF-IDF with a linear classifier, offers the advantages of simple implementation and straightforward result interpretation and explanation, it revealed limitations in failing to reflect contextual meaning between words and insufficiently capturing the multi-layered information within long documents [21].

2.2. Transformer-Based Embedding Research

With the rapid advancement of natural language processing (NLP) technology, transformer-based models, including BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers), were introduced to CTR analysis [12]. These models leveraged their contextual understanding capabilities and were applied to various applications such as TTP classification, malicious code report summarization, and incident analysis [17,22]. However, BERT struggles to process long documents like CTRs due to its input length limitation (maximum 512 tokens) [13,23]. Techniques like sliding windows, paragraph-level segmentation, and truncation have been proposed to address this, but issues like long-context disruption and reduced computational efficiency are still reported [23].

2.3. Topic Modelling and Hybrid Approach Research

To compensate for the limitations of contextual embeddings, topic modelling techniques like BERTopic have begun to be utilized [24]. BERTopic identifies latent topics within documents and can leverage them as features for classifiers, providing meaningful thematic context in CTR analysis [15,16]. Recently, hybrid approaches combining TF-IDF, embeddings, and topic distributions have been attempted, aiming to improve the balance between precision and recall. These studies are significant, as they compensate for the limitations of single approaches and can enhance the performance of CTR analysis in multiple dimensions [25,26,27].

2.4. Research Gaps and Distinctiveness of This Study

While existing research has demonstrated the potential for automated CTR analysis, several common limitations persist [6]. First, there is a lack of effective structures capable of processing long documents like CTRs without context loss [23]. Second, the problem of imbalance between precision and recall has been consistently reported, limiting practical application in security monitoring environments. Third, research on multi-label classification at the MITRE ATT&CK tactic level remains immature, and systematic comparative studies across diverse approaches are scarce. Consequently, this study focuses not merely on hyperparameter tuning for a single model, but on identifying which combination of AI models achieves optimal performance when applied to the specialized domain data of CTRs in the information security industry [14,24,28].

This holds the following academic significance: (Domain-Specific Optimization) By identifying model combinations specialized for CTR analysis, it reflects the unique characteristics of real-world security data not addressed by general NLP research. (Methodological Contribution) By combining and analyzing features with distinct characteristics—such as TF-IDF, ModernBERT, and BERTopic—it academically presents the balanced point between precision, recall, and F0.5 [9,16]. (Practical Impact) In Security Operations Centre (SOC) environments, optimal model selection directly impacts alert reliability and detection coverage; this research enhances practical applicability. (Standardization Contribution) This study provides a basis for future CTI researchers to determine suitable approaches in CTRs analysis, contributing to the establishment of research directions. Therefore, by exploring the most suitable AI model combination for CTRs, this research aims to achieve both academic originality and industrial effectiveness [17,29,30,31].

3. Methodology

This section describes the research design and experimental methodology. First, the target dataset and preprocessing steps are presented, followed by a detailed explanation of the proposed model architecture. Finally, the training environment and evaluation methods are described, and the comparative research position of this study is discussed.

3.1. Research Design Overview

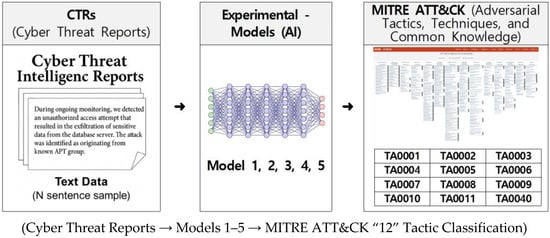

Figure 1 illustrates the overall analysis structure of this study, which takes Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) reports as input and predicts MITRE ATT&CK tactics. Input documents undergo preprocessing before being fed into the model, and the five proposed models (Model 1–5) each utilize different feature extraction methods (BERT, ModernBERT, TF-IDF, BERTopic, etc.) [12,14,24]. The objective of this study is to design various AI models for automatically classifying Cyber Threat Reports (CTRs) into the 12 tactical units of MITRE ATT&CK (TA0001–0011, TA0040) and systematically compare and analyze the most effective model combinations. While previous studies focused on hyperparameter optimization for single models, this research designs model combinations encompassing traditional vectorization, transformer embeddings, and topic modelling, considering the specialized domain of CTRs. To ensure consistency and fairness, performance is comprehensively validated using identical data and evaluation criteria [3,6].

Figure 1.

Overall analysis architecture structure.

3.2. Dataset and Processing

The rcATT dataset (Legoy et al., 2020) was used for experiments [4]. This dataset contains 1490 publicly available threat reports, with each document having a multi-label structure assigned one or more of 12 MITRE ATT&CK tactic labels (TA0001~TA0011, TA0040). Each model vectorizes document representations and then predicts tactic labels using a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) or classifier [9]. All models are designed with a multi-label classification structure, enabling simultaneous detection of multiple tactics within a single document [17]. The final output is document-level prediction results for the 12 MITRE ATT&CK tactic classes [14]. The experiment proceeded with the following workflow: input data (cyber threat reports) on the left, the AI model in the centre, and the tactic classification results on the right [24].

Models 1–3 were designed as single-source input baselines, constructed to independently evaluate the performance of each feature without any fusion process. In contrast, Models 4 and 5 adopted a late concatenation strategy, in which heterogeneous feature representations were horizontally merged at the classifier input stage. Through this integration, statistical features (TF-IDF), contextual features (BERT/ModernBERT), and topic-level features (BERTopic) were combined into a single composite vector, enabling the model to learn multi-layered semantic representations that capture both surface and deep textual characteristics.

The MLP classifier consisted of two hidden layers (2048 units each) with ReLU activations, dropout = 0.1, and the AdamW optimizer. This architecture was chosen to minimize information loss from the high-dimensional input space (over 20,000 features) and to alleviate potential representational bottlenecks. By ensuring sufficient expressive capacity relative to the input dimensionality, the model achieved stable convergence and robust generalization performance even in the feature-fusion setting.

3.3. Feature Composition and Rationale

In this study, four main features—TF-IDF, BERT, ModernBERT, and BERTopic—were employed to capture distinct linguistic levels of cyber threat intelligence (CTI) reports.

TF-IDF represents lexical importance by quantifying the statistical relevance of each word in the corpus. It measures how frequently a term appears in a document relative to its occurrence across all reports, highlighting significant cybersecurity-related terms such as malware names, attack tools, and technical commands. As a traditional statistical feature, TF-IDF serves as a strong baseline for representing surface-level lexical patterns in CTI texts.

BERT was utilized to extract contextual embeddings that reflect sentence-level and document-level semantics. By leveraging its bidirectional transformer architecture, BERT can capture contextual dependencies between tokens and understand adversarial procedures described across sentences. This enables a deeper semantic representation of attack narratives compared to purely statistical features. However, its maximum sequence length (512 tokens) poses limitations when processing lengthy CTI reports, which often exceed several thousand tokens.

To overcome this constraint, ModernBERT was employed for its enhanced long-text processing capability and computational efficiency. Supporting up to 8192 tokens, ModernBERT incorporates FlashAttention to reduce memory overhead and applies Rotary Position Embedding (RoPE) to maintain semantic coherence across extended contexts. These architectural improvements allow it to model long-range dependencies and interpret complex multi-stage attack descriptions within lengthy CTI reports more effectively than standard BERT.

Finally, BERTopic was adopted to provide topic-level abstraction and improve interpretability. Using class-based TF-IDF (c-TF-IDF), BERTopic clusters semantically related reports and identifies key topic keywords—such as “Mimikatz,” “PowerShell,” and “Cobalt Strike”—that align with MITRE ATT&CK tactics. In this study, each topic identifier was converted into a 40-dimensional one-hot vector, providing a lightweight categorical feature that represents high-level thematic patterns of CTI data.

Although these features were analyzed independently, they collectively represent complementary perspectives across lexical, contextual, and thematic dimensions, enabling a multi-layered understanding of adversarial behaviour and linguistic structure within CTI reports.

3.4. Model Structure

3.4.1. Model 1: TF-IDF + MLP

Algorithm 1 illustrates the overall process of Model 1, which employs a TF-IDF + MLP structure for multi-label classification.

| Algorithm 1 [Model-1: Classification with TF-IDF + MLP] |

| Input: document set D (rcATT, Legoy et al., 2020 [4]), 1490 threat reports; TF-IDF vectorizer; MLP classifier; labels = MITRE ATT&CK tactics (12 classes, multi-label) Output: predicted MITRE ATT&CK tactic classes

|

For document , the final prediction probability is defined as follows:

Prediction Equation

Loss Function (BCE)

Notation

- : TF-IDF vector of document

- : weights of MLP layer

- : biases of MLP layer

- : activation function (e.g., ReLU)

- : sigmoid function

- : decision threshold (default 0.5)

- : predicted label (0/1) for class c of document

- : ground-truth label

- : final output logits of the MLP

- : Binary Cross-Entropy loss

- N: total number of documents

- : set of model parameters {W, b}

Model 1 is a classification architecture that utilizes the traditional statistical feature TF-IDF as input to a multilayer perceptron (MLP) for text classification [4]. Cyber threat reports undergo preprocessing (including tokenization); specifically, for TF-IDF vectorization, we lowercase all text, remove standard English stopwords and domain-specific custom tokens (e.g., ‘xc’, ‘http’, ‘https’, ‘www’, ‘com’, ‘org’), and do not apply stemming or lemmatization to preserve security tool names (e.g., Mimikatz, Cobalt Strike). Each document is then converted into a sparse TF-IDF vector reflecting term frequency and inverse document frequency.

Here, TF-IDF limits the maximum number of features (max_features) to 20,000 and sets the n-gram range to (1,2). The generated TF-IDF vectors are fed to the MLP as input [16]. The MLP consists of two hidden layers, each containing 2048 units (neurons). A ReLU activation function is applied to the hidden layers, and a dropout rate of 0.1 is set to prevent overfitting [25]. The final output layer consists of a 12-dimensional vector corresponding to the MITRE ATT&CK tactic classes, with each output node calculating the probability for each class via the sigmoid function [12]. During inference, if the probability exceeds the threshold ( = 0.5, adjustable if needed), the tactic label is determined as the final prediction [17]. This model follows a multi-label classification structure and employs the binary cross-entropy loss function during training. Model performance evaluation was conducted based on precision, recall, and F0.5 metrics.

3.4.2. Model 2: BERT (sliding_Window) + MLP

Algorithm 2 illustrates the overall process of Model 2, which utilizes the BERT model combined with an MLP to perform multi-label classification on CTI reports.

| Algorithm 2 [Model-2: BERT (sliding window) + MLP] |

| Input: document set D (rcATT, Legoy et al., 2020 [4]), 1490 threat reports; pretrained BERT; MLP classifier; window length L (e.g., 512 tokens), stride S (e.g., 256); labels = MITRE ATT&CK tactics (12 classes, multi-label) Output: predicted MITRE ATT&CK tactic classes

|

For document d, the final prediction probability is defined as follows:

Prediction Equation

Notation

- : k-th sliding window of document

- : number of windows in document

- : [CLS] embedding of window from BERT

- : weights of MLP layer

- : biases of MLP layer

- : activation function (e.g., ReLU)

- : sigmoid function

- : decision threshold (default 0.5)

- : predicted label (0/1) for class c of document

Cyber Threat Reports (CTRs) are often lengthy documents averaging over 3000 words. However, the BERT model has a maximum input length limited to 512 tokens, making it difficult to process long documents directly [12]. To address this, Model-2 employs a sliding window technique [14]. Each CTR is divided into 256-token segments after tokenization, with 50% overlap applied to minimize context disruption [16]. For example, the first window covers (1–256), and the second window covers (129–384). Each generated window is input to BERT to extract a [CLS] vector, which is then fed to an MLP classifier to produce logits for the 12 MITRE ATT&CK tactic classes. The logits from each window are converted to probability values via a sigmoid function, and the document-level prediction is calculated by averaging the probabilities across all windows. During training, the binary cross-entropy loss function was used, and at inference, if a probability exceeds the threshold ( = 0.5), the corresponding tactic class is assigned as the final label [25]. This approach reduces information loss inherent in long CTRs and effectively incorporates diverse contextual clues [23,32].

To elaborate further, to handle the long and complex structure of CTI reports, each document was divided into overlapping segments using a fixed-length 256-token sliding window with 50% overlap. This design helps to minimize information loss and ensure smooth contextual transitions between adjacent windows. Although this fixed-length segmentation may not always align perfectly with sentence boundaries, it effectively captures tactical clues dispersed across large-scale reports that often exceed 3000 sentences. For longer models such as ModernBERT (4096 tokens), the same overlapping strategy was applied to preserve discourse continuity while respecting each model’s input size limitation. To further mitigate potential boundary inconsistencies, the outputs of overlapping segments were aggregated through mean pooling at the document level.

3.4.3. Model 3: ModernBERT (sliding_Window) + MLP

Algorithm 3 illustrates the overall process of Model 3, which employs the ModernBERT model in combination with an MLP to perform multi-label classification on long CTI reports through efficient contextual embedding.

| Algorithm 3 [Model-3: ModernBERT (sliding window) + MLP] |

| Input: document set (rcATT, Legoy et al., 2020 [4]), 1490 threat reports; pretrained ModernBERT; MLP classifier; window length (e.g., 4096 tokens), stride (e.g., 2048); labels = MITRE ATT&CK tactics (12 classes, multi-label) Output: predicted MITRE ATT&CK tactic classes

|

For document , the final prediction probability is defined as follows:

Prediction Equation

Notation

- : k-th sliding window of document (L = 4096, S = 2048)

- : number of windows in document

- : pooled embedding ([CLS] or mean) of window from ModernBERT

- : weights of MLP layer

- : biases of MLP layer

- : activation function (e.g., ReLU)

- : sigmoid function

- : decision threshold (default 0.5)

- : predicted label (0/1) for class c of document

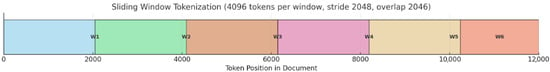

Model-3 was designed based on ModernBERT to effectively process long cyber threat reports (CTRs). CTRs are often written with an average of thousands of words or more, making it difficult for existing BERT models—limited to an input maximum length of 512 tokens—to directly reflect the entire document [12,23]. To overcome this limitation, this study adopts ModernBERT-large, designed in the original paper to process inputs up to 8192 tokens. However, considering resource constraints and model stability, the maximum input length was set to 4096 tokens for experiments. To sufficiently capture the contextual information of long documents, a sliding window technique was employed concurrently. Each document is divided into a set of windows after tokenization, with a length ( = 4096) and a stride ( = 2048), resulting in 50% overlap [14,23]. For example, the first window covers the range (1–4096), and the second window covers (2049–6144). This structure was designed to accommodate inputs of up to 32,768 tokens across the entire document, minimizing context disruption and preserving continuous semantic clues [12,14]. Figure 2 schematically illustrates the structure of the sliding window technique applied in this study.

Figure 2.

Schematic Diagram of Window Sliding (Based on MAX_LENGTH = 4096).

Each window is input into the ModernBERT encoder to generate contextual embeddings, and the window representation vector is extracted using either the [CLS] token vector or the mean pooling result. The obtained window vector is then input into a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) to produce a 12-dimensional logit, which is converted into class-specific probability values via a sigmoid function. The final document-level prediction was calculated by averaging all window probabilities. During training, the binary cross-entropy loss function was used, and at inference, if a class probability exceeded the threshold ( = 0.5), that tactical class was assigned as the final label.

Table 1 summarizes the distribution of input windows generated after sliding window segmentation across all 1490 CTRs [4,14]. Analysis revealed that 77.38% (1153 documents) could be processed with a single window, with an average document length equivalent to approximately 8.2 A4 pages [10]. Conversely, 22.62% of documents were split into two or more windows, with instances of up to 16 windows generated [23]. For example, 178 documents (11.95%) were split into two windows, and only a few documents were split into three or more windows. These results suggest that CTRs are predominantly composed of lengthy texts, meaning that key clues may be missed with single-window input alone. Therefore, the sliding window technique is confirmed as an essential preprocessing strategy for comprehensively learning the entire dataset and effectively reflecting the contextual meaning of long documents [3,9,14].

Table 1.

Distribution of original data window counts (Based on MAX_LENGTH = 4096).

Furthermore, the distribution of single-window and multi-window documents varied significantly between models due to their different input capacities. For Model 2 (BERT + MLP), which accepts up to 512 tokens, each report was segmented into an average of 9.65 overlapping windows (total 14,383 windows), with only 15.7% of reports processed within a single window. This configuration required mean-pooling aggregation to stabilize document-level predictions by integrating contextual evidence from multiple overlapping segments.

In contrast, Model 3 (ModernBERT + MLP) supports inputs up to 8192 tokens, and was configured with 4096-token windows and a 50% overlap to balance context preservation and computational stability. Under this setting, 91.5% of reports were fully processed within a single window, illustrating that ModernBERT fully leveraged its long-context capability to represent each report as a single coherent segment without losing tactical or semantic information. This difference demonstrates that while the BERT-based model relies on window aggregation to reconstruct global context, ModernBERT inherently maintains document-level coherence within a single forward pass.

3.4.4. Model 4: TF-IDF + ModernBERT (sliding_Window) + MLP

Algorithm 4 illustrates the overall process of Model 4, which integrates TF-IDF features with ModernBERT embeddings and feeds the combined representation into an MLP to perform multi-label classification on CTI reports.

| Algorithm 4 [Model-4: TF-IDF + ModernBERT (sliding window) + MLP] |

| Input: document set (rcATT, Legoy et al., 2020 [4]), 1490 threat reports; TF-IDF vectorizer; pretrained ModernBERT; MLP classifier; window length (e.g., 4096), stride (e.g., 2048); labels = MITRE ATT&CK tactics (12 classes, multi-label) Output: predicted MITRE ATT&CK tactic classes

|

For document d, the final prediction probability is defined as follows:

Prediction Equation

Notation

- : Binary output indicating if document i belongs to class c.

- : -th sliding window of document ( = 4096, = 2048)

- : Indicator function (1 if true, else 0).

- : Sigmoid activation converting logits to probabilities.

- : Threshold for class c (default 0.5).

- : Activation (e.g., ReLU) in hidden layers.

- : MLP weights and biases for layer .

- : TF-IDF feature vector for document .

- R: Optional projection matrix (SVD); identity if unused.

- : ModernBERT document embedding for document

- : Concatenation of TF-IDF and BERT features as MLP input.

Model 4 is a hybrid model concatenating statistical features (TF-IDF) and language model-based features (ModernBERT). Each document generates a sparse vector via TF-IDF, while simultaneously encoding windows segmented by the ModernBERT tokenizer to obtain a [CLS] or mean pooling-based vector . These vectors are aggregated into a document embedding via mean pooling and finally concatenated with the TF-IDF vector to form a fused input [14,24].

The concatenated vector outputs a 12-dimensional logit through an MLP, which then passes through a sigmoid function to generate class-specific probabilities. During inference, if the probability exceeds the threshold ( = 0.5), the corresponding tactical class is determined as the predicted label. This model aims to improve the balance between precision and recall in classifying long CTI documents by jointly reflecting TF-IDF’s word-distribution information and ModernBERT’s contextual semantic representation [3,6,16].

3.4.5. Model 5: TF-IDF + BERTopic + MLP

Algorithm 5 illustrates the overall process of Model 5, which combines TF-IDF features with BERTopic-derived topic embeddings and utilizes an MLP to perform multi-label classification on CTI reports.

| Algorithm 5 [Model-5: TF-IDF + BERTopic + MLP] |

| Input: document set D (rcATT, Legoy et al., 2020 [4]), 1490 threat reports; TF-IDF vectorizer; BERTopic model; MLP classifier; labels = MITRE ATT&CK tactics (12 classes, multi-label) Output: predicted MITRE ATT&CK tactic classes

|

For document d, the final prediction probability is defined as follows:

Prediction Equation

Notation

- : TF-IDF vector of docuent

- : BERTopic-based topic vector of document (stopwords removed in preprocessing)

- : concatenated TF-IDF and BERTopic features

- : weights of the MLP layer

- : biases of the MLP layer

- : activation function (e.g., ReLU)

- : sigmoid function

- τ: decision threshold (default 0.5)

Model-5 is a hybrid model that adds BERTopic-based topic features (topic distribution) to the structure of Model-1 (TF-IDF + MLP). First, the BERTopic algorithm is applied to the entire training data to cluster major topics, and each document (or window) is represented by its topic ID using one-hot encoding. These topic features are combined with the existing TF-IDF vectors to form the final input vector, which is subsequently classified through a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP). This approach aims to reflect the thematic flow of documents, thereby complementing the contextual recognition limitations inherent in TF-IDF-based models [3,9].

Specifically, the TF-IDF vector was configured with max_features = 20,000 and n-gram range = (1, 2), and custom stop words [xc, http, https, www, com, org] were applied to remove unnecessary tokens. BERTopic utilized the all-mpnet-base-v2 embedding model, with UMAP parameters for dimensionality reduction set to n_neighbors = 15, n_components = 5, min_dist = 0.0, and metric = cosine [24]. The vectorizer was based on CountVectorizer, with topic constraints set to NR_TOPICS = 40 and MIN_TOPIC_SIZE = 5 [15,24].

The final input vector was constructed by concatenating the TF-IDF vector and the BERTopic-based topic distribution vector [9,16]. The classifier was designed as an MLP with hidden layer size = 2048, number of hidden layers = 2, dropout rate = 0.1, and activation function = ReLU. Through this approach, Model-5 was designed to simultaneously incorporate statistical features (TF-IDF) and semantic-based features (BERTopic), thereby improving the balance between precision and recall in long-form CTR classification and complementing imbalanced class detection [9,15,16,33].

3.5. Document-Level Result Integration and Evaluation Method

The model proposed in this study classifies long cyber threat reports (CTRs) by dividing them into sliding window units. Each window produces probability values in the range [0, 1] for each label, but practical application requires a single prediction result for the entire document. To achieve this, this study integrated document-level results through a two-step procedure [17].

First, mean pooling was applied by averaging all window probabilities calculated for a specific label within the same document. This method mitigates locally high predictions occurring only in certain segments and contributes to producing stable probability values reflecting the overall document context [24].

Second, the rcATT dataset follows a multi-label structure in which a single CTI report can contain multiple MITRE ATT&CK tactics simultaneously. Accordingly, each tactic label is evaluated independently through a separate sigmoid output node, allowing multiple labels to be assigned to a single document at the same time. After averaging the segment-level probabilities (for models using sliding windows), each tactic’s document-level probability is compared with the fixed threshold ( = 0.5), and all labels exceeding this value are assigned concurrently. This approach differs from SoftMax-based single-label classification and employs an independent sigmoid-based multi-label prediction mechanism, enabling the model to detect multiple co-occurring tactics within the same report.

Model performance evaluation was conducted based on precision, recall, and F0.5 metrics [6,9]. Specifically, F0.5 was adopted to reflect the fact that, in the actual information security operational environments of each country and company, the importance of True Positives is prioritized over False Positives. That is, this study set detecting threats without missing them as a more important task than suppressing excessive alerts and accordingly used F0.5 as the core performance metric [29].

3.6. Positioning of Comparative Research

This study compared Model 4, optimized for precision maximization, and Model 5, strong in balanced detection, under identical conditions, considering the SOC (Security Operations Centre) environment. This provides threat response practitioners with a basis for selecting the optimal model based on their situation—whether prioritizing false negative minimization or broadening detection coverage. This approach aligns with the direction emphasized by the TRAM (Threat Report ATT&CK Mapper) project promoted by MITRE Engenuity. TRAM aims to integrate automated mapping results seamlessly into the analyst review and refinement phase, embedding it within actual operational workflows. The results of this study also demonstrate that CTRs analysis can be leveraged not merely for performance enhancement but also to boost analytical efficiency by linking it to security operations procedures [3,9,19].

Furthermore, this study holds academic significance due to its comparability, reproducibility, and ATT&CK consistency. Previous studies often used different datasets, task definitions, and evaluation metrics, making direct comparisons difficult. In contrast, this study implements a fair and reproducible comparison framework by using the same dataset (rcATT), the same tactic labels, the same cross-validation protocol (OOF), and the same metrics (including F0.5). Particularly, based on the problem definition and evaluation criteria proposed by rcATT, this study systematically verifies the performance differences among combinations of TF-IDF, ModernBERT, and BERTopic and identifies the balance point between precision, recall, and F0.5 [9,16,24].

Recent research trends also show strong interest in comparing model and feature combinations and automating ATT&CK mapping. For example, Li et al. [9] proposed a method to automatically map unstructured CTI reports to ATT&CK tactics and techniques, achieving significant performance improvements over existing approaches. Additionally, Chen et al. [17]. proposed TTPXHunter, a technique for automatically extracting TTPs from threat reports, enhancing its practical utility in security analysis. Furthermore, Arazzi et al. [3]. highlighted the importance of data quality, class imbalance, and evaluation metric standardization in their survey on CTI automation research, once again pointing out the need for comparative studies. Additionally, Albarrak et al. (2024) proposed U-BERTopic, a topic modelling technique specialized for security contexts, demonstrating the potential for topic signal augmentation. Castaño et al. (2024) released WAVE-27K, a large-scale threat report benchmark, enabling more scalable comparative experiments. In summary, this study identified the relative strengths of models optimized for CTR data based on the same benchmark, the same protocol, and various model combinations [15,34]. These findings contribute academically by establishing a foundation for comparative and reproducible research in the field of CTI automation and practically offer useful advice for model selection and operational efficiency enhancement in security monitoring environments [17,35,36].

4. Data Analysis and Critical Discussion

4.1. Experiment Purpose and Structure

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the performance of a text classification model for automatically extracting tactics from the MITRE ATT&CK framework within cyber threat reports. To this end, we directly utilized the ATT&CK-based public threat report dataset employed in the rcATT research proposed by Valentine Legoy (2020) [4]. This dataset consists of 1490 cyber threat reports, with each document assigned multi-label classifications for tactics and techniques [14].

Table 2 summarizes the 12 tactics defined in the MITRE ATT&CK framework (version 7). Tactics represent high-level behavioural categories performed by attackers to achieve specific objectives, each further subdivided into various techniques. This tactical framework encompasses the entire attack lifecycle, describing a sequence of behavioural stages from initial penetration to final impact. For example, Initial Access (TA0001) covers the process by which an attacker first gains entry into a network, with methods such as phishing or vulnerability exploitation being representative [21].

Table 2.

MITRE ATT&CK (version 7) 12 tactics indicators.

Subsequently, the attacker executes malicious code through Execution (TA0002) and secures Persistence (TA0003) to maintain long-term access privileges within the system. Next, Privilege Escalation (TA0004) and Defence Evasion (TA0005) address privilege elevation and security detection avoidance, respectively, which are core strategies frequently observed in advanced attacks [3,9]. Following this, Credential Access (TA0006) and Discovery (TA0007) target the theft of credentials and the assessment of the internal environment, serving as preparatory steps for subsequent attack phases [9,14].

Additionally, Lateral Movement (TA0008) and Collection (TA0009) describe spreading within the organization and gathering data, enabling attackers to access and secure their targeted information. Collected information is then exfiltrated externally via Exfiltration (TA0010), while the Command and Control (TA0011) stage enables persistent control through communication with remote C2 servers. Finally, Impact (TA0040) represents the stage causing final damage, such as data destruction or service disruption, signifying the damage phase where the attack’s consequences directly manifest for the enterprise or organization [1,9].

Ultimately, the MITRE ATT&CK tactics framework structures the attacker’s behavioural process into stages, providing standardized reference guidelines for cyber threat analysis and defence strategy development. Therefore, the tactical classification model proposed in this study aims to effectively identify and predict these tactics based on CTRs, which showed improved performance in enhancing the efficiency of threat response in practical environments [9,19].

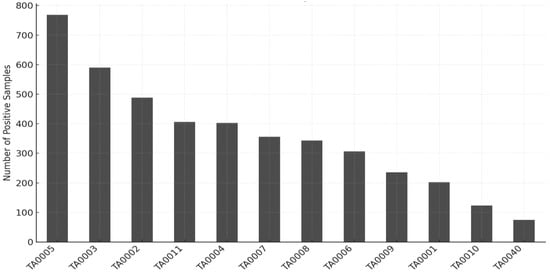

Figure 3 illustrates the label distribution across 12 tactics (TAs). Each bar represents the frequency with which a tactic is labelled as positive (1) among 1490 Cyber Threat Reports (CTRs). Tactics such as TA0005, TA0003, and TA0002 demonstrate relatively high occurrence rates, whereas TA0010 and TA0040 exhibit very low frequencies, confirming the presence of a pronounced data imbalance among tactics. Such an imbalance can lead to performance bias during model training and evaluation, thereby necessitating compensatory learning strategies for underrepresented tactics.

Figure 3.

Frequency of each tactic (TA) label with value 1 across 1490 documents.

Although recall is an essential factor in threat detection, excessive false positives can cause analyst fatigue and reduce the operational reliability of alerts in real-world SOC environments. Therefore, this study prioritized precision while maintaining recall at a reasonable level, adopting F0.5 as the primary evaluation metric. This choice reflects a precision-oriented decision strategy consistent with the practical goal of minimizing false positives and improving alert trustworthiness in multi-label and imbalanced settings.

The F0.5 metric thus provides a balanced yet precision-focused measure that aligns with operational priorities in cybersecurity analysis. In future work, recall-oriented metrics such as F2 will also be examined to validate the robustness of the models under different β-weight configurations.

4.2. Baseline Models for Comparison

The rcATT study (Legoy et al., 2020) experimentally compared various multi-classification strategies and text representation techniques for tactical classification tasks [4]. The simplest baseline presented was the majority-class classifier, which always predicts the most frequently occurring tactic in each document. However, this model performed very poorly because it relied solely on frequency without undergoing any learning process (Table 3) [21].

Table 3.

Performance of the majority class classifier.

In contrast, the combination yielding the best results in the rcATT study was a model utilizing the binary relevance strategy, a Linear SVC classifier, and TF-IDF-based vectorization. Binary relevance decomposes each tactic into an independent binary classification problem, while Linear SVC is a classifier strong at handling high-dimensional sparse vectors. This combination recorded the most stable performance in tactic classification, showing improved and more consistent results compared to the simple frequency-based model (Table 4) [9,14,24].

Table 4.

Optimal performance model (Linear SVC with TF-IDF).

In summary, the rcATT research findings demonstrate that simple frequency-based approaches fail to deliver practical classification performance. Simultaneously, the combination of TF-IDF and a linear classifier serves as the core rationale for selecting it as the baseline for the ATT&CK tactic classification problem. This model has become the benchmark against which subsequent studies applying various representations and classifiers are compared [6,12,14].

For all models, the decision threshold () was fixed at 0.5, which is the standard setting in multi-label classification. Each tactic label was assigned a value of 1 if its sigmoid probability exceeded 0.5. Fixing ensured consistent and reproducible comparisons across the five model architectures, as varying thresholds could distort the balance between precision and recall. This setting also aligns with the baseline rcATT framework (Legoy et al., 2020 [4]), maintaining fair comparability. Because false positives are more critical than false negatives in practical SOC environments, = 0.5 was retained as a balanced, precision-oriented criterion. In future work, an adaptive, validation-based threshold optimization will be considered to further improve the precision–recall trade-off.

4.3. Experimental Design of This Study

This study utilized the same dataset as rcATT but performed classification for MITRE ATT&CK tactics (12 classes) at the window level. The results were then aggregated at the document level to derive the final prediction. This approach was designed to capture tactical clues scattered within long CTR documents more precisely. Based on this, this study designed the following five experimental models (Model 1–5) and conducted detailed performance improvement experiments [9,14]. The prediction results for each model were integrated at the document level, and evaluation was performed based on the multi-label classification results per tactic (Table 5) [24].

Table 5.

Experimental model configurations.

Specifically, this study set the best baseline results reported in the rcATT paper (Micro F0.5: 65.38%, Macro F0.5: 59.47%) as the comparison benchmark and verified the performance of the proposed sliding window-based document segmentation technique and multi-model combination at the tactic level [4,9,14]. Performance evaluation used precision, recall, and F0.5 score as metrics, calculating both macro-average and micro-average. The reasons for selecting each metric are as follows.

Precision: In Security Operations Centre (SOC) environments, excessive false positives can cause analyst fatigue and reduce response efficiency. Precision—defined as the proportion of correctly identified threats among all alerts predicted by the model—is therefore a critical metric for ensuring the reliability and trustworthiness of alerts in real-world operations [25]. A high precision level indicates that the system generates fewer unnecessary alerts, allowing analysts to focus on high-priority incidents and improving overall operational efficiency.

Recall: Identifying as many true threats as possible remains an essential objective in cybersecurity detection. Recall measures the proportion of actual threats successfully detected by the model and reflects the system’s coverage of adversarial behaviours. However, in SOC practice, excessive emphasis on recall can lead to an increase in false positives, ultimately degrading operational trust. Therefore, this study prioritizes precision while maintaining recall at a reasonable level, reflecting the practical trade-off required for stable and efficient security monitoring [6,9].

F0.5 Score: In this study, placing a higher weight on precision than on balancing precision and recall is crucial. This is because accurately identifying threats holds greater value than excessive detection in security operations environments. F0.5 aligns with this study’s objective by prioritizing correct detection over false detection, giving precision a relatively higher weight [9,16,29].

Consequently, precision represents alert reliability, recall indicates detection coverage, and F0.5 balances these two metrics. By comprehensively analyzing these three metrics in this study, we can verify where the proposed models outperform the existing rcATT baseline and assess their practical applicability from multiple angles [17].

4.4. Experimental Results

To comprehensively and reliably evaluate model performance across the 12 ATT&CK tactic classes, this study reports both micro-level and macro-level metrics, including Precision, Recall, and F0.5. The micro-level results summarize the overall predictive performance of the model, while the macro-level analysis reflects each tactic’s contribution under conditions of class imbalance, providing a fairer assessment of model robustness and generalization capability. In future work, a confusion matrix analysis will be incorporated to visually examine false-positive and false-negative patterns and to interpret inter-tactic confusion more effectively.

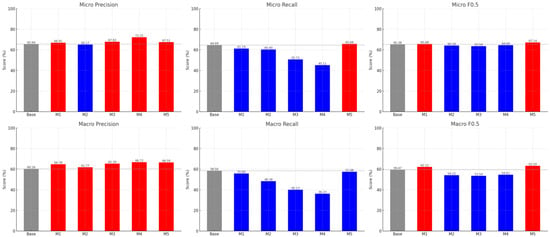

Table 6 and Figure 4 show the classification performance of the five models compared to the baseline (linear SVC) using precision, recall, and F0.5 metrics. Overall, traditional techniques like TF-IDF + MLP (Model 1) and embedding-based approaches such as BERT (Model 2) and ModernBERT (Model 3) showed some improvement in precision. However, a significant drop in recall was observed, limiting the overall improvement in F0.5 performance. This demonstrates that simply increasing precision alone is insufficient to achieve overall detection performance improvements in real-world multi-tactic classification. The most notable results were observed in Model 4 and Model 5. Model 4 (TF-IDF ⊕ ModernBERT) achieved 72.25% micro-precision, representing a +10.07 percentage point improvement over the baseline and the highest precision among all models. This suggests Model 4 is optimized for a precision-focused detection strategy.

Table 6.

Summary of experimental results by model.

Figure 4.

Comparison of key performance metrics by model (Micro/Macro Precision, Recall, and F0.5).

Conversely, Model 5 (TF-IDF ⊕ BERTopic) maintained precision while slightly improving micro recall (+1.55 percentage points) and achieved 63.20% on macro F0.5, showing the most prominent improvement of +6.27 percentage points over the baseline. Thus, Model 5 can be evaluated as a model that elevates overall performance while maintaining a balance between precision and recall. In summary, Model 4 maximizes precision detection performance, making it suitable for security operations scenarios where minimizing false positives is critical. Model 5 demonstrates balanced detection performance across diverse classes, including rare tactics, making it highly applicable in real-world SOC (Security Operations Centre) environments. For these reasons, this study subsequently focuses on Model 4 and Model 5 as key comparison targets, analyzing their respective strengths and limitations in detail.

4.5. Interpretation of Results

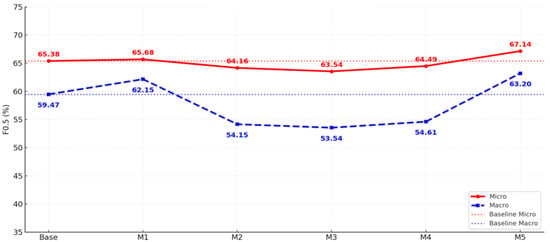

Figure 5 shows the comparison of F0.5 scores between the baseline and each model on micro and macro evaluation metrics. Micro F0.5 maintained a stable level overall without significant fluctuation, with Model 5 achieving the highest performance at 67.14%. In contrast, Macro F0.5 dropped significantly to 54.15% for Model 2 and 53.54% for Model 3, before recovering to 63.20% for Model 5, surpassing the baseline (59.47%) [4,9].

Figure 5.

F0.5 trends by model (Micro vs. Macro).

These results clearly demonstrate that in data environments with severe class imbalance, such as CTRs, micro- and macro-metrics can exhibit different patterns. Specifically, while the micro metric reflects the average performance across the entire dataset and shows a stable trend, the macro metric reacts sensitively to performance differences between classes, revealing significant performance degradation in specific models. Therefore, both metrics should be considered together when interpreting model performance [3,9,29].

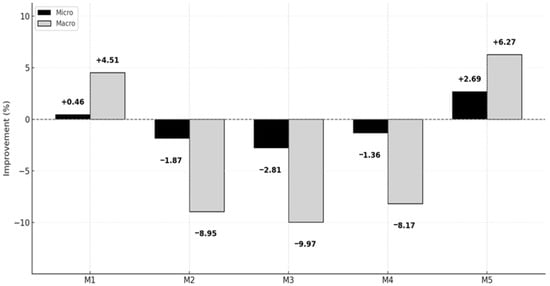

Figure 6 presents the relative improvement rate of each model’s F0.5 performance compared to the baseline. Model 1 recorded a modest improvement of +0.46% on the micro metric and +4.51% on the macro metric, demonstrating that applying an MLP classifier to a traditional TF-IDF-based model can yield some performance gains. Conversely, Models 2 through 4 all showed performance degradation compared to the baseline [9,14]. Notably, the Macro F0.5 scores decreased by −8.95%, −9.97%, and −8.17%, respectively, indicating a loss of contextual information during the long document segmentation process. This suggests that simply extending input length or introducing embedding-based representations is insufficient to reliably secure performance for imbalanced classes [3,6,9].

Figure 6.

Improvement rate of F0.5 (%) compared with the baseline.

In contrast, Model 5 (TF-IDF ⊕ BERTopic) achieved performance improvements of +2.69% and +6.27% at the micro and macro levels, respectively, showing the most prominent enhancement among all models. This indicates that topic-based features effectively complement the detection of various classes, including rare tactics, and secure overall performance balance. Collectively, these results intuitively reveal the relative strengths and weaknesses of each model, particularly highlighting that Model 5 provided the most reliable improvement on the F0.5 metric. Therefore, Model 5 can be considered the most promising approach for practical application in imbalanced data environments like CTRs [9,14,24].

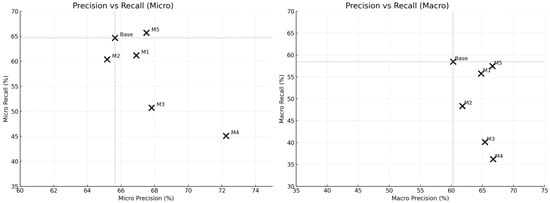

Figure 7 compares the precision-recall relationships for each model under micro (left) and macro (right) settings. The x-axis represents precision, and the y-axis represents recall, where points in the upper-right corner indicate ideal performance with both metrics high. Conversely, points in the lower left indicate poor performance with both metrics low. Therefore, moving to the right signifies improved precision, while moving upward indicates enhanced recall, and securing both axes simultaneously represents the ultimate goal of model performance. From the micro perspective (left graph), the baseline model achieves a precision of 65.64% and a recall of 64.69%, positioning it at a relatively balanced point. Model 4 moved rightward, raising precision to 72.25%, but recall dropped significantly to 45.11%, shifting it downward. Conversely, Model 5 maintained or improved both precision and recall, positioning itself above and to the right of the baseline, securing the most stable performance [15,16].

Figure 7.

Precision–recall distributions by model (based on Micro and Macro metrics).

A similar pattern is observed from the macro perspective (right graph). Models 3 and 4 moved to the right due to higher macro precision, but recall dropped significantly to 40.13% and 36.23%, respectively, revealing tactical class imbalance issues. In contrast, Model 5 achieved Precision 66.59% and Recall 57.49%, positioning itself above and to the right of the baseline, demonstrating balanced detection performance across all classes [24]. Ultimately, these results visually demonstrate that Model 4 is specialized for precision detection in CTRs classification, while Model 5 is a balanced detection model securing both precision and recall [6,15]. This can serve as crucial evidence for determining which model is more suitable for specific situations in practical applications [9,19].

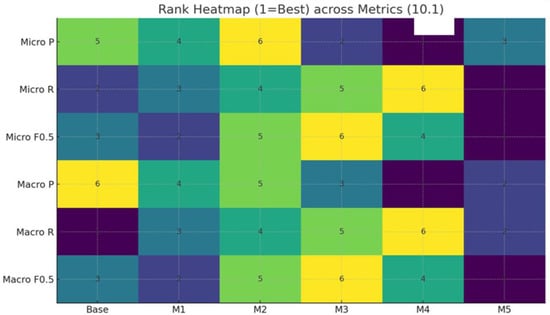

Figure 8 presents the comparative rankings of each model across Micro and Macro metrics for Precision, Recall, and F0.5 as a heatmap. The vertical axis represents the evaluation metrics (Micro Precision, Micro Recall, Micro F0.5, Macro Precision, Macro Recall, Macro F0.5), while the horizontal axis denotes the comparison models (Baseline and Models 1–5). The numbers within the heatmap indicate the rank for that metric (1 = best, 6 = worst), while the colours visually indicate the relative magnitude of each rank. Generally, lighter colours (yellow tones) indicate lower rankings, meaning relatively poor performance, while darker colours (blue and purple tones) represent higher rankings.

Figure 8.

Heatmap of model performance rankings by metric (1 = Best Performance).

Therefore, this heatmap allows for an intuitive comparison of each model’s position relative to others across metrics, rather than focusing on absolute numerical values. As the heatmap shows, Model 4 achieved leading performance in Micro Precision but remained in the lower ranks for Macro Recall, strongly revealing its precision-focused nature. Conversely, Model 5 maintained leading positions in both Micro F0.5 and Macro F0.5, demonstrating consistently robust performance across multiple metrics. This suggests that even if a specific model excels in certain metrics, maintaining balanced top-tier performance across diverse metrics is more crucial for ensuring operational applicability.

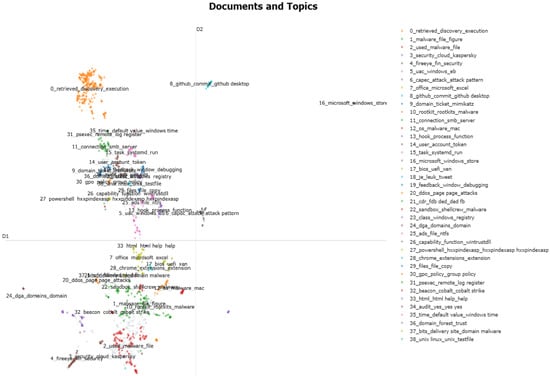

Figure 9 visualizes the document-topic distribution derived from the BERTopic algorithm applied to Model 5, projected into a two-dimensional space. Each point in the graph represents a single CTRs document, where colour indicates the topic to which the document belongs. The legend on the right lists each topic number and its representative keyword, enabling interpretation of which tactics/techniques each cluster relates to. The latent axes (D1, D2) are virtual axes representing the dimensionality reduction results. Their significance lies in the relative distances and distribution patterns between points instead of absolute values. That is, points that form compact clusters represent documents with similar content, while points far apart represent documents covering different topics. The first notable feature visible in this figure is that a majority of documents form well-separated clusters. Each cluster is grouped around tactical/technical keywords like retrieved, discovery, execution, or Microsoft, Windows, or store. This indicates that topic-level patterns can be reliably extracted even from lengthy reports like CTRs.

Figure 9.

Visualization of document–topic distribution based on BERTopic.

Second, it is noticeable that some clusters are located proximally to each other. For example, activities related to the initial penetration phase, execution, and maintaining persistence within the system are located close together. This empirically indicates that these phases often appear together in actual attack reports. Such positioning allows the classification model to reflect the inherent semantic correlations between tactics when learning from documents, potentially contributing to reducing misclassifications. Third, the peripheral clusters situated on the outer edges of the graph reflect minority tactics. Their stable distribution in distinct latent regions indicates that BERTopic-based topic features can accurately discriminate minority tactics even under class imbalance conditions.

These structural characteristics correspond to actual performance results. Model 5 achieved performance improvements over the Baseline: Micro Recall +1.55 percentage points, Micro F0.5 +2.69 percentage points, and Macro F0.5 +6.27 percentage points. Notably, the improvement in Macro F0.5 corresponds with the stable separation of minority tactic clusters observed in the graph. Conversely, Models 2 and 3 suffered contextual fragmentation during the process of dividing and concatenating long documents using a sliding window approach, thereby preventing sufficiently similar documents from being semantically clustered, resulting in a degradation in Recall.

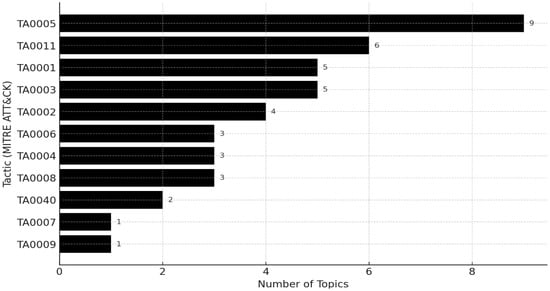

In summary, Figure 10 demonstrates that Model 5 effectively clusters documents into distinct thematic representations and forms a feature space robust against linguistic diversity and class imbalance. This is significant because it reduces threat-detection omissions in real Cyber Threat Report (CTR) analysis environments and provides more reliable classification performance in practical applications. Figure 11 shows the results of mapping topics derived from Model 5 (TF-IDF + BERTopic + MLP) to the 12 tactics of the MITRE ATT&CK Framework (v7). Since BERTopic extracts topics based on document-level word distributions, it does not directly provide tactic labels. Therefore, this study interpreted the representative keywords of the 39 topics using domain-specific information-security knowledge and mapped them to each tactic (see Appendix A).

Figure 10.

Topic distribution by MITRE ATT&CK tactics based on BERTopic.

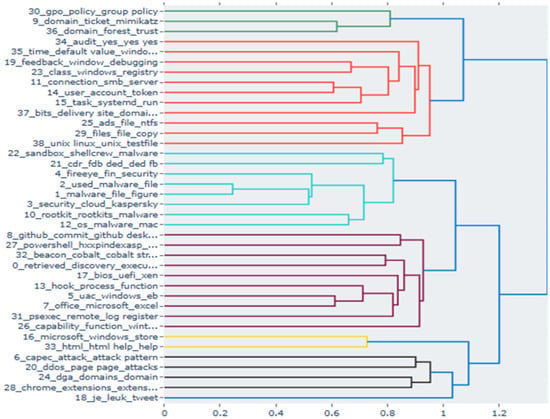

Figure 11.

Hierarchical clustering results derived using BERTopic topic embeddings.

Analysis revealed that many topics corresponded to specific tactics. For example, topics related to Mimikatz corresponded to Credential Access (TA0006), PsExec and SMB to Lateral Movement (TA0008), PowerShell to Execution (TA0002), and Cobalt Strike to Command & Control (TA0011). Keywords such as UAC bypass, rootkit, and sandbox evasion reflected the Defence Evasion (TA0005) tactic. Some topics included keywords indicating both Initial Access (TA0001) and Persistence (TA0003), demonstrating that Model 5 can capture tactics that frequently co-occur in real-world attacks, rather than distinguishing them in isolation.

Conversely, topics lacking clear cybersecurity relevance—such as Windows Store or tweet—were identified as semantic noise. This indicates the model’s capability to effectively filter irrelevant subjects, enhancing analytic efficiency in operational contexts. In summary, Figure 11 demonstrates that BERTopic-based topics extend beyond simple keyword clustering to reflect actual adversarial behaviour and tactical context. Furthermore, the mapping procedure utilizing the technical expertise of information-security professionals facilitates more interpretable and explainable model outputs. It also aids in systematically understanding tactical-level correlations during the CTR analysis process. These findings indicate that Model 5 not only delivers a numerical performance improvement (Macro F0.5 + 6.27 pp) but also strengthens its interpretability by revealing inter-tactic relationships.

Figure 11 shows the results of visualizing topics derived from Model 5 (TF-IDF + BERTopic + MLP) using hierarchical clustering. The y-axis represents each topic and its representative keywords, while the x-axis indicates the similarity distance between topics. In the dendrogram, closer branches signify greater semantic proximity between topics, and colours distinguish major cluster groups. First, the clustering results showed high correspondence with the MITRE ATT&CK v7 framework. For example, the red cluster includes registry, SMB, PsExec, GPO, etc., reflecting the Lateral Movement (TA0008) and Persistence (TA0003) tactics. This aligns with the attacker’s strategy of propagating within a network and maintaining persistent footholds. The purple cluster, associated with PowerShell, Mimikatz, Cobalt Strike, etc., encompasses Execution (TA0002), Credential Access (TA0006), and Command & Control (TA0011), illustrating behaviours frequently observed together during real-world intrusion scenarios. The turquoise cluster aggregates items corresponding to Defence Evasion (TA0005), such as rootkits, sandbox evasion, and UAC bypass, effectively representing concealment and detection avoidance techniques. Finally, the lime-green cluster includes Chrome extensions, BITS delivery, and domain trust, mapping to Initial Access (TA0001) and Exfiltration (TA0010).

Second, these results indicate that Model 5 goes beyond merely classifying documents into specific tactics; it can also capture the intrinsic inter-tactic relationships observed in real attack reports. That is, the process by which adversaries progress from initial penetration to execution, privilege escalation, and persistence, then expand to information exfiltration and remote control, is visually revealed as a continuous attack chain. This was difficult to discern with conventional flat classification models. Third, some topics (e.g., Windows Store, tweet, HTML help) were classified as semantic noise, not directly linked to specific tactics. However, this demonstrates the model’s capability to effectively filter out non-threat-relevant content, potentially improving analytic efficiency by eliminating redundant information in operational environments.

To capture higher-level semantic structures, this study applied BERTopic to the entire rcATT dataset, which contains 1490 Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) reports, and derived 39 latent topics. Each document was assigned to one representative topic, converted into a one-hot encoded vector, and concatenated with the TF-IDF features. This categorical topic indicator was designed to provide clear topic boundaries rather than continuous probabilistic semantics. As shown in Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11, the topic–tactic mapping revealed distinct correspondences between certain topics and MITRE ATT&CK tactics. For example, Mimikatz (Credential Access, TA0006), PowerShell (Execution, TA0002), and Cobalt Strike (Command and Control, TA0011) were each clearly associated with specific tactics. These clear topic boundaries contributed to improving model stability and detection consistency for rare or overlapping tactics. Experimentally, the results of Model 5, which incorporated the BERTopic one-hot features, demonstrated that even this simple discrete representation enhanced the model’s generalization performance while maintaining semantic clarity within the hybrid architecture.

In future work, we plan to evaluate the performance of a continuous topic-distribution vector approach, which can probabilistically capture documents spanning multiple topics. Furthermore, by integrating such continuous topic representations with TF-IDF and ModernBERT features, we aim to expand the semantic representation space and further improve the precision and robustness of automatic tactic classification for CTI reports. In summary, Model 5 concatenates TF-IDF-based statistical features with BERTopic-derived topic embeddings and links them to an MLP classifier. This approach goes beyond simple quantitative performance improvement (Macro F0.5 + 6.27%) to support a structural understanding of the progression of attack tactics. This is particularly significant as it provides a practical foundation for identifying inter-tactic linkages in threat intelligence analysis and enhancing multi-stage attack detection.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

This study compared and analyzed five models for automatically classifying MITRE ATT&CK tactics based on cyber threat intelligence (CTI) reports [2,4]. The baseline rcATT model, using TF-IDF + Linear SVC, achieved Micro F0.5 65.38% and Macro F0.5 59.47%, serving as the performance benchmark against which the proposed models were evaluated [14]. Experimental results showed that the TF-IDF ⊕ ModernBERT model achieved a micro-precision of 70%, demonstrating the greatest improvement in detection precision, although recall was reduced, limiting coverage. Conversely, the TF-IDF ⊕ BERTopic model achieved Micro F0.5 67.14% and Macro F0.5 63.20%, representing a +6.27 percentage point improvement over the baseline. Notably, Macro Precision improved by +10.5 percentage points, showing clear strengths in detecting imbalanced and rare tactics. Furthermore, by mapping BERTopic-based topics to ATT&CK tactics, this study provided insights into relationships between tactics beyond numerical improvements [15,16,24].

Real-world CTI reports often describe multiple adversarial behaviours simultaneously, leading to semantic drift and tactic overlap. To address this, the study employed a multi-label classification framework using independent sigmoid activations, enabling multiple tactics to be assigned per document and reducing semantic information loss. The proposed structure improved label validity and robustness under overlapping conditions. Notably, Model 5 (TF-IDF ⊕ BERTopic) achieved balanced precision, recall, and F0.5 scores, maintaining stable performance even for rare tactics such as TA0010 Exfiltration and TA0040 Impact. These results confirm that topic-level features help preserve contextual coherence within complex multi-tactic narratives. Future research will extend this approach through confusion-matrix analysis and adaptive thresholding, aiming to enhance interpretability and robustness in real CTI environments.

(Academic Contribution) This study holds significance not merely as a proposal of a new model but as comparative research aligned with recent trends. Li et al. (2024) [9], Chen et al. (2024), and others emphasized the necessity of mapping ATT&CK tactics/techniques and extracting TTPs based on CTI reports [17]. Arazzi et al. (2025) identified data imbalance and evaluation metric standardization as key challenges in CTI automation [3]. Within this context, this study systematically compared and analyzed feature-level concatenations of TF-IDF, ModernBERT, and BERTopic, demonstrating the complementary value of precision-focused and balanced detection models. This provides a foundation for advancing CTI tactic classification research into more sophisticated comparative and evaluation phases [6,14].

(Industrial Practical Outcomes) Practically, automated CTI report analysis plays a critical role in enhancing SOC (Security Operations Centre) operational efficiency, reducing analyst workload, and reflecting the latest attack group TTPs [19]. As emphasized by MITRE’s TRAM project, integrating model outputs seamlessly into analyst workflows is essential [18,19]. The findings of this study align with this need. Model 4 demonstrated strong precision in reducing false positives, while Model 5 achieved balanced detection across all tactics, including rare ones. This can be directly applied to threat hunting and adversary emulation scenarios, providing a practical foundation for implementing Threat-informed Defence [2].

Furthermore, the results of this study quantitatively demonstrate the potential to reduce analyst workload in SOC environments. As shown in Table 6 and Figure 8, Model 5 (TF-IDF ⊕ BERTopic) outperformed the baseline rcATT model in all metrics, achieving Precision = 66.59%, Recall = 57.49%, and F0.5 = 67.14%. These improvements suggest that the model can enhance alert reliability and reduce false positives, thereby mitigating alert fatigue and improving operational efficiency within SOC workflows. In particular, the gain in precision helps decrease unnecessary alerts, allowing analysts to focus on higher-priority incidents rather than repetitive triage tasks. This finding is also consistent with the POMDP (Partially Observable Markov Decision Process)–based cybersecurity risk model proposed by Donchev et al. (2021) [37], which reported that when the false-positive rate exceeds approximately 20–25%, the effect of risk reduction reaches saturation. Hence, reducing false positives—i.e., improving precision—directly contributes to both operational and security risk mitigation. In this context, the proposed model presents a hypothetical yet technically grounded potential to alleviate analyst workload through precision improvement and false-positive reduction. However, since this study did not include user studies, deployment trials, or practitioner feedback, its industrial relevance remains at a hypothetical level. Therefore, future work will focus on conducting empirical validations to establish concrete evidence and to demonstrate the model’s industrial applicability in real SOC environments.

(Future Research Directions) Future work will explore (1) ensemble methods combining the strengths of different models to simultaneously improve precision and rare-tactic detection [14], and (2) hybrid approaches integrating diverse representations (TF-IDF, ModernBERT, BERTopic) into a unified vector space to optimize both precision and recall [15,20,26,38].

(Overall Conclusion) In conclusion, this study demonstrated the validity of a hybrid approach in CTI report-based tactic classification. The precision-focused detection model excelled at identifying high-risk tactics, while the balanced detection model showed strength in detecting rare tactics [6,9]. Both models played complementary roles. Most importantly, this study contributes academically by reinforcing the comparative analytical foundation for CTI automation research and practically by improving accuracy and efficiency in SOC-based threat response [2,9,19].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.K.; Research Design and Methodology, J.B.; Data Collection, J.B.; Model Development and Implementation, J.B.; Experimentation, J.B., J.O. and S.J.; Formal Analysis, J.B.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, J.B.; Writing—Review and Editing, W.K.; Supervision and Academic Guidance, W.K.; Project Administration, W.K.; Technical Consultation and Algorithm Improvement, J.O.; Model Validation and Performance Evaluation, J.O.; Literature Review, J.O.; Experimental Environment Setup, S.J.; Data Preprocessing Support, S.J.; Reproducibility Verification and Technical Validation, S.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Informed Consent Statement

All authors give consent for the publication of identifiable details, which can include photograph(s) and/or videos and/or case history and/or details within the text to be published in the above journal and article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author Prof. Wooju Kim, upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

BERTopic cluster analysis of Model 5 (based on information security technology).

Table A1.

BERTopic cluster analysis of Model 5 (based on information security technology).

| Topic | Key Keywords | Mapped Tactic | Confidence Level | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | retrieved, discovery, execution | TA0001/2/6/7/11 | High | ‘discovery’ keyword is directly associated with reconnaissance tactics |

| 1 | malware, file, microsoft | TA0005- | Low | Generic malware keywords, Difficulty in specifying tactics |

| 2 | used, malware, file | - | Low | APT/File Context, No Explicit Tactic Indicators |

| 3 | security, cloud, kaspersky | - | Low | Security vendor–related context |

| 4 | uac, windows, dll | TA0004/5 | Medium ~High | UAC bypass → privilege escalation |

| 5 | office, macros, excel | TA0001/2/6/7/11 | High | Macro execution = initial access/execution |

| 6 | github, commit, download | TA0001/3/10 | Medium | Potential intrusion via public repositories/downloads |

| 7 | capec, attack_pattern | - | Low | Attack pattern literature |

| 8 | fireeye, fin, apt | - | Low | Vendor information |

| 9 | domain_ticket, mimikatz, kerberos | TA0001/2/6/7/11 | Very High | Mimikatz = representative tool for credential theft |

| 10 | rootkit, malware | TA0005 | High | Rootkit = detection evasion |

| 11 | connection, smb, server | TA0003/6/8 | High | SMB connection = lateral movement |

| 12 | os_malware_mac, wirulker | TA0005/TA0040 | Medium | macOS malware concealment |

| 13 | hook, process, function | TA0001/2/5/6/7/11 | High | Process hooking/injection |

| 14 | user_account_token, lsa | TA0003/6/8/14 | High | Token/LSA related = credential theft |

| 15 | task, systemd, run, schtasks | TA0003/6/8/14 | High | Scheduled tasks/systemd |

| 16 | microsoft_windows_store | - | Low | General platform keywords |

| 17 | bios, uefi, xen | TA0004/TA0003 | Medium | Firmware/Boot-Level Privilege Escalation |

| 18 | je_leuk_tweet, op, meer | - | Low | Social/noise |

| 19 | feedback_window_debugging | TA0003/5/6/7/8 | Medium | Debugging-related reconnaissance/anti-debugging |

| 20 | ddos, page, attacks | TA0040 | High | DDoS = denial of service |

| 21 | cdr, fdb, ded, fd | - | Low | File/forensic |

| 22 | sandbox, shellcrew, trojan | TA0005 | High | Sandbox evasion |

| 23 | class, windows, registry, atom | TA0003/5/6/8 | Medium | Registry manipulation |

| 24 | dga, domains, domain | TA0011 | Very High | DGA = C2 persistence |

| 25 | ads, file_ntfs, stream | TA0005 | Medium | Alternate Data Streams |

| 26 | capability_function, wintrustdll | TA0005 | Medium | WinTrust signature manipulation |

| 27 | powershell, script, hxxp | TA0001/2/6/11 | High | PowerShell execution |

| 28 | chrome, extensions, webstore | TA0001/3/10 | Medium | Intrusion/persistence via malicious extensions |

| 29 | files, file_copy, executable | TA0001/3/9/10 | Medium | File collection |

| 30 | gpo, policy, group policy | TA0003/6/8 | Medium ~High | Policy/GPO manipulation |

| 31 | psexec, remote, log register | TA0003/6/8 | Very High | PsExec = lateral movement |

| 32 | cobalt_strike, beacon | TA0011 | Very High | Cobalt Strike = C2 tool |

| 33 | html, html_help | - | Low | Formal Keywords |

| 34 | audit_yes_yes, policy | - | Low | Noise/logs |

| 35 | time_default_value, windows time | TA0003/5/6/8 | Medium | Timer-based persistence |

| 36 | domain_forest_trust | TA0001/3/4/8/10 | Medium | Abuse of forest trust |

| 37 | bits_delivery, malware_delivery_site | TA0001/3/10/11/40 | Medium | BITS job = payload/C2 |

| 38 | unix, linux, chmod | TA0002 | Medium | Unix shell execution |

References

- Peltola, S. Threat Detection Analysis Using MITRE ATT&CK Framework. Master’s Thesis, JAMK University of Applied Sciences, Jyväskylä, Finland, May 2025. Available online: https://www.theseus.fi/handle/10024/888343 (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- MITRE Corporation. MITRE ATT&CK Framework; MITRE Corporation: Bedford, MA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://attack.mitre.org (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Arazzi, M.; Arikkat, D.R.; Nicolazzo, S.; Nocera, A.; Conti, M. NLP-Based Techniques for Cyber Threat Intelligence. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2025, 58, 100765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legoy, V.; Caselli, M.; Seifert, C.; Peter, A. Automated Retrieval of ATT&CK Tactics and Techniques for Cyber hreat Reports. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, L.; Müller, M.; Torbati, G.H.; Milchevski, D.; Grau, P.; Pujari, S.; Friedrich, A. AnnoCTR: A Dataset for Detecting and Linking Entities, Tactics, and Techniques in Cyber Threat Reports. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.; Lee, Y.; Shin, S. Vulcan: Automatic Extraction and Analysis of Cyber Threat Intelligence from Unstructured Text. Comput. Secur. 2022, 120, 102763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.; Shin, C.; Shin, S. Cyber attack group classification based on MITRE ATT&CK model. J. Internet Comput. Serv. 2022, 23, 1–13. Available online: https://www.jics.or.kr/digital-library/38235 (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Wang, G.; Liu, P.; Huang, J.; Bin, H.; Wang, X.; Zhu, H. KnowCTI: Knowledge-Based Cyber Threat Intelligence Entity and Relation Extraction. Comput. Secur. 2024, 141, 103824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Huang, C.; Chen, J. Automated Discovery and Mapping of ATT&CK Tactics and Techniques for Unstructured Cyber Threat Intelligence. Comput. Secur. 2024, 140, 103815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, A.; Calic, D.; Delfabbro, P. “Generic and Unusable”: Understanding Employee Perceptions of Cybersecurity Train-ing and Measuring Advice Fatigue. Comput. Secur. 2023, 128, 103137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]