Abstract

Amidrapid advances in intelligent medicine, decoding brain activity from electroencephalogram (EEG) signals has emerged as a critical technical frontier for brain–computer interfaces and medical AI systems. Given the inherent spatial resolution limitations of an EEG, researchers frequently integrate functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to enhance neural activity representation. However, fMRI acquisition is inherently complex. Consequently, efforts increasingly focus on cross-modal transformation methods that map EEG signals to fMRI data, thereby extending EEG applications in neural mechanism studies. The central challenge remains generating high-fidelity fMRI images from EEG signals. To address this, we propose a diffusion model-based framework for cross-modal EEG-to-fMRI generation. To address pronounced noise contamination in electroencephalographic (EEG) signals acquired via simultaneous recording systems and temporal misalignments between EEGs and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), we first apply Fourier transforms to EEG signals and perform dimensionality expansion. This constructs a spatiotemporally aligned EEG–fMRI paired dataset. Building on this foundation, we design an EEG encoder integrating a multi-layer recursive spectral attention mechanism with a residual architecture.In response to the limited dynamic mapping capabilities and suboptimal image quality prevalent in existing cross-modal generation research, we propose a diffusion-model-driven EEG-to-fMRI generation algorithm. This framework unifies the EEG feature encoder and a cross-modal interaction module within an end-to-end denoising U-Net architecture. By leveraging the diffusion process, EEG-derived features serve as conditional priors to guide fMRI reconstruction, enabling high-fidelity cross-modal image generation. Empirical evaluations on the resting-state NODDI dataset and the task-based XP-2 dataset demonstrate that our EEG encoder significantly enhances cross-modal representational congruence, providing robust semantic features for fMRI synthesis. Furthermore, the proposed cross-modal generative model achieves marked improvements in structural similarity, the root mean square error, and the peak signal-to-noise ratio in generated fMRI images, effectively resolving the nonlinear mapping challenge inherent in EEG–fMRI data.

1. Introduction

As the supreme regulatory center of the human physiological system, the brain orchestrates both fundamental life-sustaining processes and the integration of higher-order neural functions—including cognition, emotion, and behavior. Neuroimaging technologies, which serve as the core methodological framework for deciphering neural activity, have become pivotal pillars of neuroscience and medical research. By enabling non-invasive observation, these techniques permit the systematic investigation of cerebral structure and function, elucidate coupling mechanisms between cognitive behavior and neural activity, and delineate characteristics of neural dynamics. Consequently, they provide a critical scientific foundation for both basic research and clinical diagnostics.

Within the diversified neuroimaging landscape, electroencephalography (EEG) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) constitute two of the most widely employed modalities. EEG records cortical electrophysiological activity via scalp electrode arrays, offering millisecond-level temporal resolution that enables the precise capture of transient neuronal firing patterns [1]. This superior temporal fidelity renders EEG an optimal tool for investigating neural circuitry and the rapid dynamical fluctuations of cerebral activity. Nevertheless, volume conduction through the skull and scalp introduces pronounced spatial blurring, which fundamentally limits EEG’s capacity to characterize deep subcortical structures. In contrast, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) capitalizes on the blood-oxygenation-level-dependent (BOLD) effect, which indirectly measures neural activity by translating variations in deoxyhemoglobin concentration into whole-brain functional maps [2]. Boasting millimetre-level spatial resolution, fMRI affords comprehensive brain coverage, thereby effectively compensating for EEG’s limited sensitivity to subcortical structures. However, its inherent hemodynamic latency—a consequence of the delayed BOLD response—severely restricts temporal resolution, precluding the direct tracking of rapid neural dynamics. Empirical studies have demonstrated a robust neurophysiological coupling between electroencephalography (EEG) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) signals [3,4,5]. Consequently, multimodal EEG–fMRI fusion has been extensively investigated to leverage their complementary information for a more complete elucidation of brain states [6,7]. However, the widespread application of fMRI is intrinsically constrained by its high equipment costs, demanding infrastructure requirements, and incompatibility with metallic implants [8]. These limitations restrict its utility in resource-limited clinical settings and often preclude its use in specific patient cohorts. In contrast, EEG systems offer inherent cost-effectiveness and portability, substantially enhancing their accessibility for both research and clinical use. This practicality enables data collection across a broader participant population, including individuals with claustrophobia or implanted medical devices.

Recent research has increasingly utilized deep-learning techniques to decode brain-activity images from electroencephalography (EEG) signals and reconstruct visual percepts. Early work by Kavasidis et al. (2017) [9] introduced “Brain2Image,” an LSTM-based generative framework that translates EEG data into images by mapping neural oscillatory patterns to visual representations. Subsequently, Fares et al. (2019) [10] employed bidirectional long short-term memory (Bi-LSTM) networks to capture dynamic features of EEG signals, significantly improving the classification of visually evoked brain activity. Building on these advances, Suchetha et al. (2021) [11] applied convolutional neural networks directly to EEG-derived feature maps, enabling more accurate identification and classification of electrophysiological data and enhancing performance in brain–computer interface applications. To further demonstrate the utility of EEG, recent studies have shown that EEG signals can serve as supervisory information for learning semantic feature representations, achieving performance comparable to semantic image-editing tasks [12]. In 2023, Mishra et al. [13] proposed NeuroGAN, a multi-class image-generation framework combining EEG features with generative adversarial networks (GANs). By integrating attention mechanisms and deep feature extraction from visually evoked EEG responses, NeuroGAN achieved state-of-the-art generation quality, further underscoring the potential of EEG in visual synthesis. Most recently, Yang (2024) [14] introduced DreamDiffusion, which employs a pre-trained text-to-image diffusion model conditioned on EEG-specific temporal masking to significantly enhance the fidelity of reconstructed visual brain-activity images.

The principal contributions of this work are as follows:

- (1)

- A Novel EEG-conditioned Diffusion Model (EF-Diffusion): While previous diffusion models have excelled in image generation, their application to the EEG-to-fMRI problem remains largely unexplored and faces unique challenges such as severe noise in EEG and complex cross-modal mapping. Unlike existing methods that often rely on simplistic conditioning, we propose EF-Diffusion, a framework that introduces two core innovations: (a) a dedicated EEG encoder (EPG) with a Multi-Head Recursive Spectral Attention (MHRSA) mechanism to dynamically extract noise-robust, spectrally aware neural features and (b) a Cross-modal Information Interaction Module (CIIM) integrated within the U-Net, which uses cross-attention to enable fine-grained, spatially adaptive guidance of the fMRI denoising process by EEG semantics. This design fundamentally differs from prior diffusion-based works by providing a deeply fused and dynamic conditioning pathway that is specifically tailored for the intricacies of neuroimaging data.

- (2)

- Comprehensive Validation and Novel Insight: We provide, to our knowledge, the first extensive empirical demonstration that a diffusion-based model can significantly outperform existing GAN and transformer-based methods in EEG-to-fMRI generation. Through rigorous ablation studies on two public datasets (NODDI and XP-2), we not only validate the necessity of each proposed component (EPG and CIIM) but also deliver a key finding: our model achieves superior performance on task-state data, highlighting its capability to leverage strong stimulus-evoked neural correlates, a conclusion quantitatively and qualitatively supported by state-of-the-art results in SSIM, PSNR, and RMSE.

2. Theoretical Foundations for EEG-Guided Synthesis of fMRI Data

This chapter establishes the theoretical foundations for this work by first outlining the principles of electroencephalography (EEG) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). It places a particular emphasis on the two concurrently acquired EEG–fMRI datasets used in this study. The chapter then details the deep learning methodologies that underpin the proposed synthesis framework.

2.1. Principles of EEG–fMRI Neuroimaging

2.1.1. Principles of EEG Neuroimaging

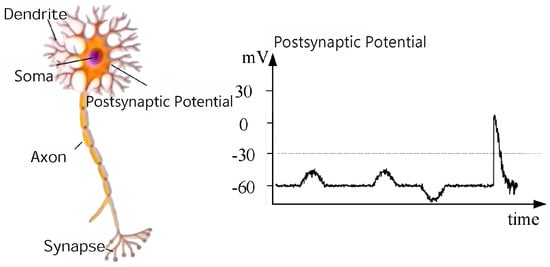

Electroencephalography (EEG) is a non-invasive technique that records macroscopic electrical activity from the scalp (Figure 1). The EEG signal primarily reflects the summation of postsynaptic potentials (PSPs)—transmitter-gated ionic currents—and action potentials (APs) from large, synchronously firing populations of cortical pyramidal neurons. The resting transmembrane ion gradients establish a baseline voltage; the synchronized synaptic activity within these neuronal populations generates the oscillations measurable as the scalp EEG.

Figure 1.

Principle of EEG neuroimaging.

The EEG signal exhibits a broad frequency spectrum that is conventionally partitioned into five canonical bands—delta, theta, alpha, beta, and gamma [15,16]—each correlated with specific cognitive operations and global brain states. Delta oscillations (0.5–4 Hz) dominate deep slow-wave sleep; theta rhythms (4–7 Hz) mediate creative insight and meditation; alpha activity (8–13 Hz) accompanies relaxed wakefulness; beta power (12–30 Hz) [17] supports motor control and higher-order executive processes; and gamma transients (>30 Hz) [18] subserve sensory processing and perceptual binding. Empirical evidence indicates that the brain recruits these distinct frequency channels in a task-selective manner [19]. For instance, enhanced alpha power suppresses irrelevant inputs during a relaxed yet vigilant state, whereas gamma synchronization is implicated in sensory coding and mnemonic consolidation. Furthermore, training-induced increases in theta amplitude during meditation correlate with improved cognitive flexibility, underscoring that EEG spectra not only index baseline neural activity but also dynamically track moment-to-moment cognitive states.

2.1.2. Principles of fMRI Neuroimaging

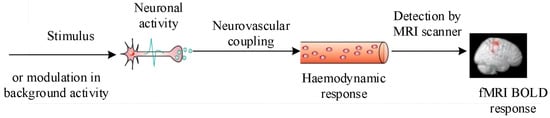

Unlike electroencephalography (EEG), functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) indirectly measures neural activity. Most fMRI relies on blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) contrast [20]. When neurons fire, neurovascular coupling increases local blood flow, reducing paramagnetic deoxyhemoglobin. This improves magnetic field homogeneity, lengthening the T2 relaxation time detected by T2-weighted sequences to map brain activity (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Principle of fMRI neuroimaging.

The hemodynamic response function (HRF) is conventionally used to characterize the temporal dynamics of this process [21]. Following stimulus onset, the BOLD signal typically peaks within 5–8 s and requires a comparable duration to return to baseline; both the latency and the shape of the HRF vary across brain regions and individuals, as they are influenced by the physiological state. Owing to its high spatial resolution (typically 2–5 mm) and unique sensitivity to deep-brain structures—including subcortical nuclei—fMRI complements EEG’s temporal precision and has become a cornerstone technique in neuroscience.

2.2. Simultaneous EEG–fMRI Dataset

The advent of simultaneous EEG–fMRI acquisition has provided neuroscience with an unprecedented opportunity to investigate functional and structural brain connectivity; however, its utility remains constrained by variability in hardware configurations and the absence of standardized acquisition protocols. Divergent experimental designs and dissimilar recording criteria often introduce significant discrepancies between electrophysiological and hemodynamic data. To permit a comprehensive evaluation of the methodology proposed herein, we selected two openly available datasets: a resting-state collection (NODDI) and a task-based collection (XP-2). We present the detailed characteristics of each dataset in the following sections.

2.2.1. Resting-State Simultaneous EEG–fMRI Dataset

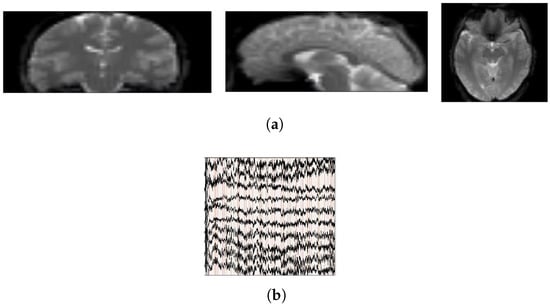

NODDI is a representative resting-state, simultaneously acquired EEG–fMRI dataset [22,23] comprising eleven male and six female volunteers aged from 24.71 to 40.97 years. All data were acquired on a Siemens Avanto 1.5 T clinical scanner equipped with a self-shielded gradient system (maximum amplitude = 40 mT m−1). During the session, participants were instructed to keep their eyes open and fixate on a white cross presented on a black background; head motion was minimized using a vacuum cushion. Functional images were obtained using a T2-weighted gradient-echo EPI sequence: 300 volumes, TR = 2160 ms, TE = 30 ms, 30 axial slices, slice thickness = 3.0 mm, and effective voxel size = 3.3 × 3.3 × 4.0 mm3. EEG was recorded simultaneously with a 64-channel MR-compatible cap referenced to FCz at an original sampling rate of 5 kHz and clock-synchronized to the MR scanner. Representative segments of the EEG–fMRI data are displayed in Figure 3a (fMRI) and Figure 3b (EEG).

Figure 3.

Display of raw EEG-fMRI data segments. (a) fMRI data; (b) EEG data.

For storage, the EEG data are divided into two folders, EEG1 and EEG2. These two subsets are identical in acquisition protocol and preprocessing; they are separated solely due to file size constraints and can be merged into a single folder when possible. The files contain EEG data preprocessed with Brain Vision Analyzer 2. Because EEG data recorded inside the MR environment suffers from severe gradient artifacts, a standard preprocessing pipeline is applied to simultaneously acquired data; here, we use the preprocessed EEG supplied with the dataset. The fMRI dataset comprises the functional images and high-resolution T1-weighted anatomical images acquired in the same session. Furthermore, because the EEG and fMRI signals were sampled at different rates, further preprocessing is required; we thus paired the simultaneous EEG–fMRI recordings using the publicly available pipeline described in reference [24].

2.2.2. Task-Based Simultaneous EEG–fMRI Dataset

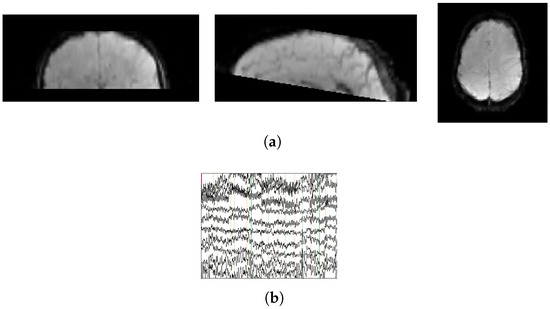

Task-state data typically require participants to perform designated tasks. The dataset XP-2 [25] featured a “motor-imagery neurofeedback task” and comprised 17 subjects (mean age: 28.4 ± 10.6 years). Sixty-channel EEG and fMRI data were simultaneously acquired to record brain activity and provide neurofeedback while participants imagined right-hand movements. The experimental protocol consisted of five EEG–fMRI runs alternating between rest and task blocks, each lasting 20 s. Representative samples of the dataset are shown in Figure 4a (fMRI) and Figure 4b (EEG).

Figure 4.

Display of raw EEG-fMRI data segments. (a) fMRI data; (b) EEG data.

For EEG processing, the data were preprocessed using Brain Vision Analyzer II. Automatic gradient artifact correction was performed with a template-based subtraction algorithm to minimize artifact contamination. After downsampling to 200 Hz, the EEG was filtered with a 50 Hz low-pass FIR filter. Cardiac artifacts were identified and marked using a semi-automatic procedure. For fMRI, data were acquired with echo-planar imaging. Unlike most fMRI protocols, the XP-2 dataset covered only the upper brain. Acquisition parameters were as follows: TR = 1 s, TE = 23 ms, spatial resolution = 2 × 2 × 4 mm3, and 16 contiguous 4 mm thick slices. The EPI sequence was started 2 s before task onset; consequently, the first two TRs were discarded. As with the resting-state dataset, simultaneous EEG–fMRI recordings were paired using the publicly available pipeline described in reference [24].

2.3. Overview of Deep Learning Theory

2.3.1. Convolutional Neural Network

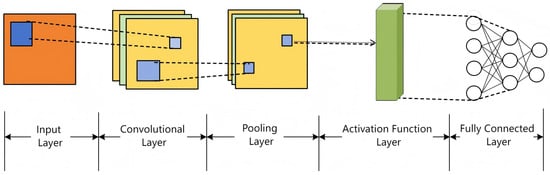

A convolutional neural network (CNN) is a deep feed-forward architecture for processing high-dimensional data like images and videos. Its hierarchical structure includes an input layer, convolutional layers, activation functions, pooling layers, and fully connected layers, as shown in Figure 5. Convolutional layers extract spatial features using local receptive fields and shared weights, progressing from edges to object parts. Pooling layers (e.g., max-pooling) reduce dimensionality and enhance spatial invariance. Fully connected layers integrate high-level features for classification/regression, with nonlinearity provided by activation functions.

Figure 5.

Convolutional neural network architecture.

CNNs demonstrate strong representational capacity and generalization, forming a cornerstone of computer vision. By mimicking biological visual hierarchy and incorporating advances like residual connections, CNNs have driven modern deep learning development.

- (1)

- Convolutional layer

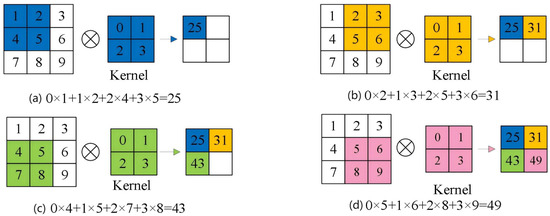

As the core building block of a CNN, the convolutional layer performs a local dot-product operation, where a learnable kernel is convolved across the input feature map. At each location, the kernel values are multiplied by the corresponding input values, and the products are summed. Figure 6 illustrates this procedure. With a fixed stride, the filter moves across the input. When the kernel is positioned over the upper-left region, each weight is multiplied by the underlying pixel value; these products are summed, and the result becomes the first entry of the output feature map. Repeating this multiply–accumulate operation as the kernel shifts across the spatial domain produces a new matrix that encodes the original data’s local spatial relationships. This locally connected, weight-sharing scheme preserves key spatial information while significantly reducing computational complexity.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of the convolution operation.

- (2)

- Pooling Layer

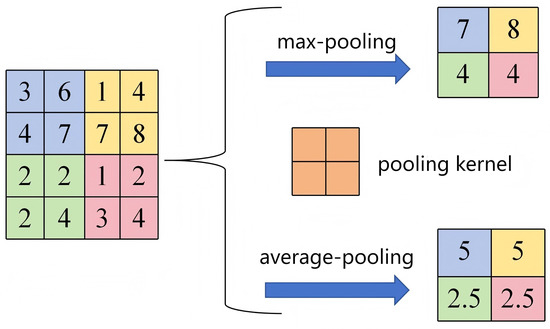

As a core CNN component, the pooling layer performs spatial compression and feature selection via a sliding window with a fixed stride. It applies summary statistics: max-pooling retains the maximum value per window, while average pooling computes the arithmetic mean. Max-pooling amplifies strong local responses to enhance discriminative power, whereas average pooling suppresses noise while preserving distributional characteristics. The former prioritizes salient features, while the latter maintains informational integrity. This parameter-free operation halves feature-map dimensions, confers spatial robustness, and enables efficient deep computation. As shown in Figure 7 (stride = 2), the operations are defined by Equations (1) and (2).

where Y denotes the pooled output feature map, X denotes the input feature map, and k is the window size of the pooling operation.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of the pooling-layer operation.

- (3)

- Activation Functions

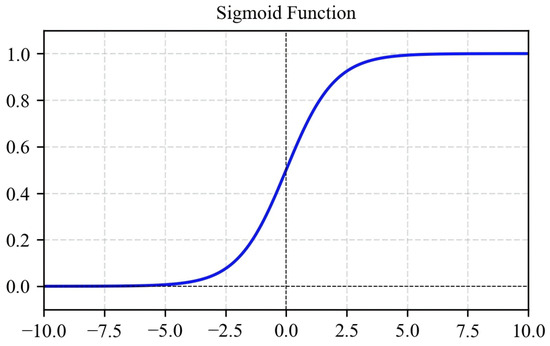

Nonlinear activation functions are essential components in neural networks, transforming linear combinations into nonlinear responses to enable hierarchical modeling. They enhance model expressivity for complex function approximation. Commonly used functions include Sigmoid, Tanh, and ReLU [26,27,28].

The Sigmoid function maps inputs to (0, 1), facilitating probability estimation and gradient computation. However, it suffers from vanishing gradients with large-magnitude inputs and produces non-zero-centered outputs, hindering deep network training. Thus, it is primarily used in output layers for binary classification (Equation (3); Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Sigmoid activation function graph.

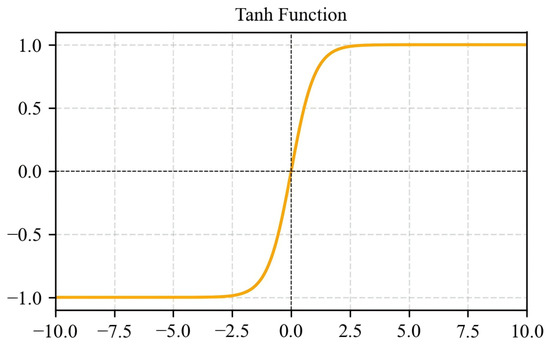

Tanh outputs in [−1, 1], offering zero-centered symmetry that often accelerates convergence compared to Sigmoid (Figure 9). Nevertheless, it still exhibits vanishing gradients for extreme inputs, limiting its use mainly to shallow networks (Equation (4)).

Figure 9.

Tanh activation function graph.

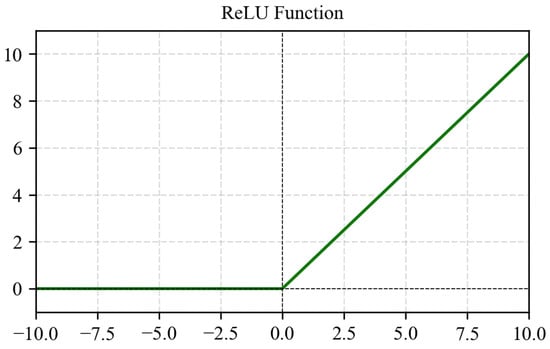

ReLU avoids vanishing gradients for positive inputs, making it highly effective for deep networks (Figure 10). Its main limitation is zero output for negative inputs, causing “dead neurons.” Despite this, ReLU remains widely adopted due to its computational efficiency (Equation (5)).

Figure 10.

ReLU activation function graph.

In summary, while Sigmoid and Tanh have been largely superseded by ReLU and its variants for hidden layers, activation function selection should be determined by specific task requirements and network architecture considerations.

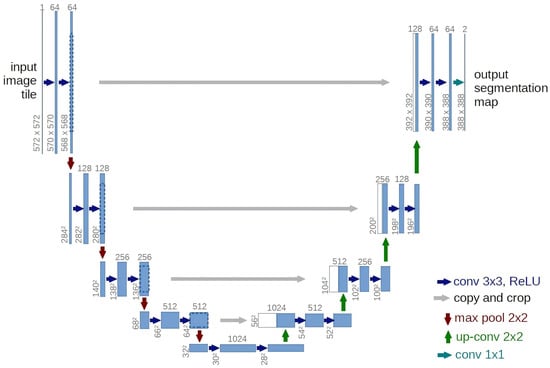

2.3.2. U-Net

Featuring a symmetrical encoder–decoder design [29], the U-Net architecture (Figure 11) uses convolutional blocks and downsampling in the encoder to extract features, a bottleneck for global context, and upsampling in the decoder to restore resolution. Skip connections between corresponding layers preserve image details.

Figure 11.

U-Net network architecture.

Owing to its symmetric architecture, the U-Net excels at pixel-level tasks and has become the de facto standard not only for medical-image segmentation but also as the backbone of diffusion models such as DDPM, where it generates high-quality images by predicting noise at each time step. Although subsequent studies have explored hybrid designs incorporating Transformer modules, the U-Net remains pivotal in both medical imaging and generative tasks. Consequently, we retain the original DDPM configuration and adopt the U-Net as the deep learning model in this work.

2.3.3. Attention-Based Neural Network

The attention mechanism has emerged as a revolutionary development, finding widespread adoption across deep learning. Initially introduced to capture long-range dependencies in natural language processing, it has since been extended to computer vision, speech recognition, and other domains. By mimicking the human ability to focus, the attention mechanism re-weighs different parts of the input, amplifying salient features and suppressing irrelevant information, thereby improving both model efficiency and task-specific performance. Traditional networks treat inputs as fixed-length vectors and assign equal weight to every element, ignoring the fact that some parts are more informative than others—e.g., certain words carry greater significance in machine translation. The attention model addresses this limitation through dynamic weight allocation; the model adaptively adjusts the importance of each element based on contextual cues.

- (1)

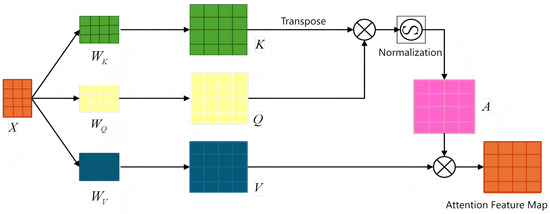

- Self-attention mechanism

The self-attention mechanism [30] is now a standard component of modern neural architectures. It works by computing pairwise similarities among all elements in an input sequence to generate a dynamically weighted representation for each element. Since each element can attend to all others, self-attention excels at modeling long-range dependencies, as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Self-attention mechanism.

The self-attention mechanism operates through a series of distinct steps: first, the raw input is embedded into a feature space; second, query, key, and value vectors are generated; third, attention weights are computed; and finally, a weighted sum is applied. The input is typically represented as a sequence of N vectors, each of dimension d. These input vectors are then projected into the query, key, and value spaces via linear transformations. The corresponding computations are shown in Equations (6)–(8).

where , , and are weight matrices and X is the input sequence. Next, the similarity between each query vector (Q) and all key vectors (K) is computed as their dot product.

The pairwise relationships between all queries and keys are captured in a similarity matrix. These scores are typically scaled by a factor of to ensure stable gradients. This scaling prevents excessively large dot-product values in high-dimensional spaces, which can lead to vanishing gradients after the Softmax operation. The scaled dot products are then passed through a Softmax function to produce a probability distribution, forming the attention weights for each query. Specifically, the attention weight matrix A is computed as Equation (9), where

These weights are then used to compute a weighted sum of the value vectors V, producing a contextualized representation for each element. Each output element thus becomes a weighted combination of all input values, with the weights signifying the contextual influence of other elements in the sequence. The complete computation for the self-attention output is summarized by the following equation (Equation (10)):

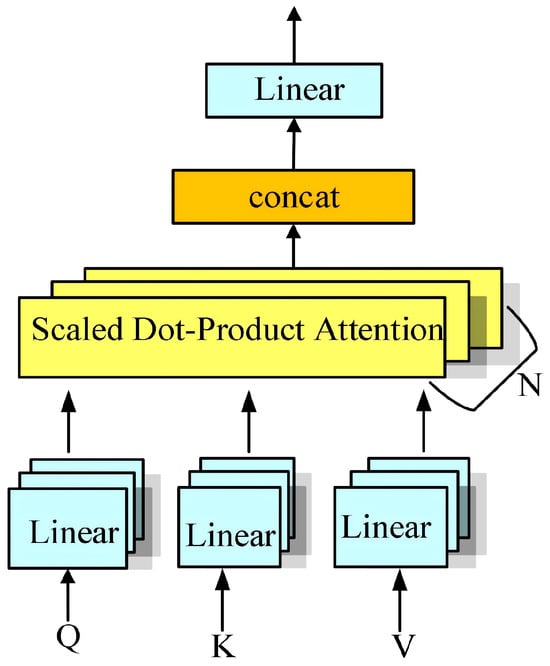

- (2)

- Multi-Head Self-Attention Mechanism: To enhance the expressive power of neural networks, the multi-head self-attention mechanism [31] is often employed, as illustrated in Figure 13. The key idea is to compute multiple independent attention heads in parallel, each operating in a distinct subspace, thereby capturing information at various positions and levels of abstraction. Specifically, the queries, keys, and values are first projected into several lower-dimensional subspaces; the attention output of each head is then computed separately, and the resulting vectors are concatenated or linearly combined to produce the final representation. The computation is summarized in Equation (11).where is the output of each attention head, is a linear transformation matrix, and h is the number of heads.

Figure 13. Multi-head self-attention mechanism.

Figure 13. Multi-head self-attention mechanism.

Multi-head self-attention enhances model expressivity by attending to different parts of the input in parallel. This parallel processing allows the model to capture diverse dependencies across multiple representation subspaces simultaneously.

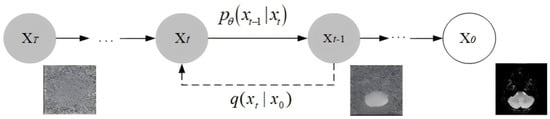

2.3.4. Principles of Diffusion Models

The Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Model (DDPM) is a generative model based on probability theory and inspired by diffusion processes in physics [32]. Its forward noising and reverse denoising processes are illustrated in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

The diffusion model’s working principle diagram.

In deep learning, diffusion models transform input data into a Gaussian distribution by progressively adding noise; they then execute the inverse process, gradually denoising the data to generate a clear output. This procedure is formulated as a Markov chain. Its distinctive mechanism has driven significant breakthroughs in image generation.

- (1)

- Forward diffusion process: In the forward process of the denoising diffusion probabilistic model, assume a given data distribution and a Markov chain that gradually adds Gaussian noise to the original data, generating a sequence of random variables . Here, T is the total number of steps in the diffusion process. The diffusion process is described by Equation (12):According to Equation (12), in the diffusion process, the joint distribution of the data is obtained by the product of the conditional distributions at each step. The mathematical equation for is Equation (13):where represents the noise weight added to the data at each time step, with ; T is the covariance matrix of the noise, which is an identity matrix; and represents the noisy data at step t.Through multiple iterations, the noisy data at any time step can be computed based on and , allowing us to derive , which follows a Gaussian distribution. The mathematical expression is shown in Equation (14).where is the original image without noise and ; .

- (2)

- Reverse diffusion process

The reverse process is also a parameterized Markov chain. This denoising trajectory begins from a state of pure noise, , and learns to recover the original data, . The reverse-diffusion process is defined by Equation (15):

The reverse diffusion process progressively denoises a pure Gaussian noise input to generate a clean data sample. Its probability distribution is defined as shown in Equation (16):

where and are the mean and covariance parameterized by a neural network. The core of the denoising neural network is to estimate the noise from the noisy data ; can then be recovered from using Equation (17).

where controls the noise intensity and is related to the time step t; is the noise estimated by the noise estimation model, which is typically predicted by a neural network model; the parameter represents the weights of the neural network; and represents the noise intensity at a specific time step t.

The training objective is to minimize the error between the estimated noise and the actual noise, as shown in Equation (18).

2.4. Evaluation Metrics

To quantitatively assess the quality of the generated fMRI images, we employ metrics that measure structural and fine-detail discrepancies between synthetic and real data, thereby objectively quantifying their consistency. The most widely used metrics are the peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) and the Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM). Furthermore, to facilitate comparison with previous studies, we also report the root mean square error (RMSE) as a supplementary metric.

(1) Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR): The PSNR quantifies the discrepancy between a generated image and its reference, providing a standard metric for assessing fMRI reconstruction quality. A higher PSNR indicates stronger consistency with the original data, signifying superior reconstruction. Conversely, a lower PSNR reflects greater deviation, increased distortion, and poorer quality. This metric is defined in Equation (19).

where n is the number of bits per sample (for grayscale images, ) and MSE denotes the mean squared error, i.e., the average of the squared deviations between pixels and their reference values, calculated as shown in Equation (20).

where X denotes the generated fMRI image, Y denotes the ground-truth fMRI image, H represents the image height, and W signifies the image width.

(2) Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM): The SSIM evaluates generated image quality by measuring three perceptual dimensions: luminance, contrast, and the spatial structure. As it closely aligns with human visual perception, the SSIM is widely used to assess the outputs of image enhancement and generative models. The metric is defined in Equation (21).

where is the luminance measurement, is the contrast measurement, is the structure measurement, and , , and are constants.

To obtain the simplified form, let , and let , , and be constants. The simplified formula is given in Equation (25):

where and are the mean values of images x and y, and are the variances of images x and y, is the covariance between images x and y, and and are small constants used to stabilize the division and prevent division by zero.

(3) Root Mean Square Error (RMSE): The RMSE is a statistical metric that quantifies the error between the generated fMRI image and the ground-truth image; its formula is as follows:

where n denotes the total number of pixels, is the pixel value of the reference data, and is the pixel value of the reconstructed data at the corresponding coordinate.

2.5. Chapter Summary

This chapter has detailed the physiological foundations of EEG and fMRI neuroimaging and provided a systematic overview of deep learning theory, focusing on the working principles of CNNs, the U-Net, attention mechanisms, and diffusion models. It also introduced the two simultaneously acquired EEG–fMRI datasets used in our experiments—the NODDI resting-state dataset and the XP-2 task-based dataset—alongside the evaluation metrics. The material presented here establishes the foundation for the EEG-to-fMRI translation framework and the experimental analysis developed in the following chapters.

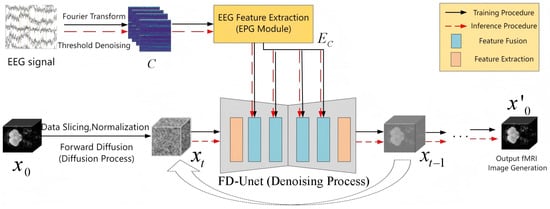

3. Research on EEG-to-fMRI Cross-Modal Generation via Diffusion Models

To address the nonlinear and highly complex mapping between EEG and fMRI, this chapter proposes an EEG-to-fMRI generation framework built on diffusion models. By integrating 3-D convolutional residual networks with multiple attention mechanisms, the approach accomplishes the targeted task of synthesizing fMRI images from EEG signals; the resulting network is termed the EF-Diffusion model. Here, we elaborate on the overall architecture of EF-Diffusion, with a particular emphasis on the EEG signal encoder and the EEG-fMRI information-interaction module. Finally, comprehensive experiments are conducted to evaluate the model’s performance.

3.1. Establishment of the EF-Diffusion Model

In this chapter, we construct EF-Diffusion (EEG-to-fMRI Diffusion), a network that translates EEG signals into fMRI images by leveraging the principles of diffusion models. As illustrated in Figure 15, the architecture adopts the concept of text-prompted generation, treating the EEG recording as conditional guidance that steers the synthesis of fMRI volumes. The framework consists of two main components: (i) an EEG signal encoder, termed the EEG Prompt Generation (EPG) module, and (ii) an fMRI-denoising U-Net, referred to as FD-UNet.

Figure 15.

EF-Diffusion network architecture.

The EF-Diffusion model functions differently during training and inference. During training, the model requires both EEG signals and fMRI images as inputs. These data undergo distinct preprocessing strategies tailored to their respective modalities [24] before being fed into the network. The core workflow consists of a forward diffusion process and a reverse denoising process. The forward process gradually adds random noise, transforming the initial fMRI image into a near-pure noise state over a series of time steps, as defined by Equation (27). The reverse process reconstructs the original data from this noisy state. Specifically, the FD-UNet is trained to predict the noise added at each step; a sampler then uses these predictions to iteratively remove the noise, recovering the original image to generate the fMRI output. This reverse procedure is formulated in Equation (28).

where is a hyperparameter that decreases over time; this process is characterized by a Markov chain, where each step is typically controlled by a variance-preserving transformation.

where and are predicted by the FED-UNet neural network and c represents EEG features.

During inference, only the EEG signal is fed into the EF-Diffusion model. This signal is encoded and then used by the FD-UNet and sampler to generate an fMRI image from a pure noise distribution, thereby achieving EEG-to-fMRI synthesis.

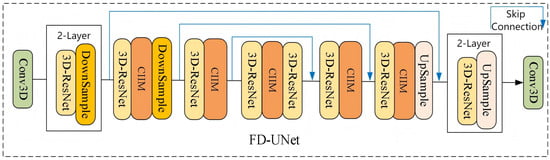

3.2. FD-UNet Network Design

This chapter’s fMRI-denoising network, FD-UNet, is a residual-enhanced U-Net with a four-level encoder–decoder architecture. Its detailed structure is illustrated in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

Detailed structure diagram of the FD-UNet network.

In the FD-UNet encoder, the forward pathway is built from three principal components: (i) 3-D residual blocks (3D-ResNet), (ii) a Cross-modal Information Interaction Module (CIIM), and (iii) downsampling layers (DownSample). The 3D-ResNet and downsampling stages are designed to progressively extract rich feature representations from the noisy fMRI volume while reducing spatial resolution, thereby capturing both low-level and high-level cues. After each downsampling step, the channel count is increased and the spatial size is halved.

Additionally, a Cross-modal Information Interaction Module (CIIM), which uses a cross-attention mechanism, is inserted at every point in the network where the fMRI tensor has spatial dimensions of [8, 8, 4]. This module performs a joint analysis of the EEG and fMRI modalities, aligns their feature spaces, and enables the network to focus on task-relevant information during the complex denoising process.

The decoder is architecturally symmetric to the encoder and likewise embeds a Cross-modal Information Interaction Module (CIIM) to refine features, steering and enhancing detail recovery. It comprises 3-D residual blocks (3D-ResNet) followed by UpSample layers; after each upsampling bundle, the spatial resolution doubles, while the channel count is halved. Skip connections convey the feature maps from the corresponding encoder level, concatenating them with the decoder features at each stage. By progressively increasing geometric fidelity and reducing channels, the network restores fine structures and semantics; detailed layer parameters are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameter table of the FD-UNet network.

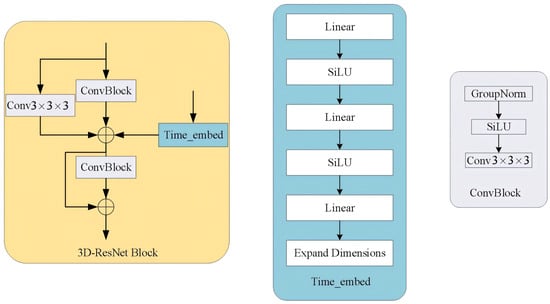

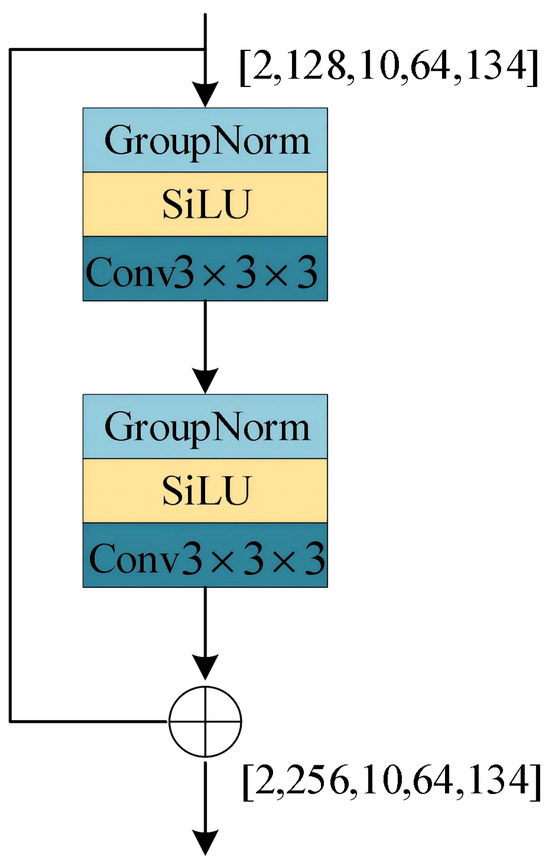

3.2.1. The 3D-ResNet Module

The 3D-ResNet module serves as the fundamental building block of the FD-UNet architecture, comprising two ConvBlock modules, a time-step-encoding block, and a skip connection.

Each ConvBlock and each time-step-encoding block comprise convolution, normalization, and activation layers that extract local features and boost nonlinearity. A skip-connection convolution allows gradients to flow directly to deeper layers, mitigating vanishing-gradient problems. After every 3D-ResNet unit, down-sampling is performed with a 3-D pooling layer; the corresponding upsampling stage uses 3-D nearest-neighbor interpolation (a zeroth-order method). When building these modules, the dimensionality of the time-step embedding must be expanded so that its shape matches the fMRI feature maps, enabling element-wise addition. Detailed structures of the 3D-ResNet and time-step-encoding blocks are illustrated in Figure 17.

Figure 17.

Diagram of the 3D-ResNet module and its component structure.

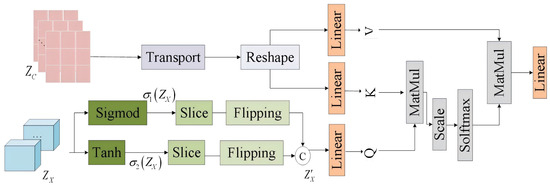

3.2.2. The Cross-Modal Information Interaction Module

In this chapter, the Cross-modal Information Interaction Module (CIIM) serves as a key component of FD-UNet; its primary function is to enable information exchange between EEG signals and fMRI images so that EEG can drive fMRI generation. The CIIM introduces a cross-attention mechanism that fuses multimodal data through learnable weighting. The module receives two inputs: the fMRI noise feature map output by the 3-D residual network and the EEG signal feature map produced by the EEG encoder. First, undergoes non-linear transformations via the Tanh and Sigmoid functions to yield two complementary feature maps, and ; these are then split along the channel dimension, reversed, concatenated, and fused to generate an enriched representation, . Finally, and are fed into the linear layers of the cross-attention mechanism. The detailed structure is illustrated in Figure 18.

Figure 18.

Cross-modal information interaction module.

Cross-attention operates through three components—query (Q), key (K), and value (V)—each projected into a shared embedding space via linear transformations. In this work, Q is derived from the fMRI feature map by a linear layer, yielding a query tensor of shape [2, 2048, 128] that encodes every spatial location of the fMRI volume. K and V are obtained from the EEG feature map , producing both key and value tensors of shape [2, 1632, 128] that represent electrode-specific time–frequency characteristics. Similarity between Q and K is computed (scaled dot product), converted to attention probabilities with Softmax, and used to weigh V. The resulting weighted sum is then linearly transformed to produce the updated fMRI feature map. Detailed computations are provided in Equations (29)–(33).

where , , and are learnable weight matrices of the model and is a dynamic parameter representing the dimension of the key vectors, which changes adaptively with the number of channels in each network layer.

At each diffusion time-step, the temporal and spectral features extracted by the EEG encoder serve as conditional cues to guide fMRI generation. This cross-modal interaction ensures correspondence between the synthesized fMRI volumes and the input EEG while also improving structural consistency and content fidelity. Specifically, a cross-attention module aligns the encoded EEG features with the fMRI feature maps. This mechanism steers the denoising trajectory so that every intermediate state is informed by the EEG signature, enabling the network to progressively reconstruct an fMRI image whose spatial patterns reflect the input EEG characteristics.

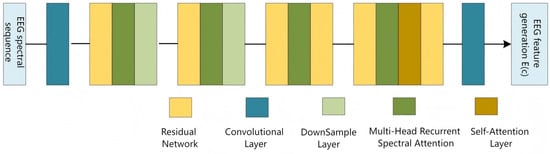

3.3. The EEG Signal Encoder

In the EF-Diffusion model, the EEG-signal encoder—termed the EPG (EEG Prompt Generation) module—serves as the core component for processing and extracting features from EEG recordings. To exploit the frequency content of the signal, we first apply a Fourier transform while preserving electrode-channel information. Consequently, the EEG tensor is high-dimensional and multi-featured: denotes the number of EEG electrodes. F represents the frequency, and T denotes the time samples. The detailed architecture of the EPG module is illustrated in Figure 19.

Figure 19.

EEG prompt generation network architecture.

The input EEG spectro-temporal sequence is passed through multiple convolutional and attention layers to extract discriminative EEG spectral image features, which are then denoted as and fed into the FD-UNet layers to guide the generation of realistic fMRI images. The EPG module consists of one 3-D convolutional layer, residual blocks, downsampling layers, Multi-Head Recursive Spectral Attention (MHRSA), and self-attention. A front-end 3-D convolution first preprocesses the EEG data so that both spatial and temporal information can be represented in deeper layers. The residual network block within the EEG encoder is illustrated in Figure 20.

Figure 20.

Residual network architecture diagram.

To match the model’s input requirements, the input tensor is defined as , while the output of the stacked layers is . Residual connections are introduced to alleviate the vanishing gradient problem caused by increasing network depth. By adding skip connections between the input and output of each convolutional block, the residual pathway ensures that the original features are delivered directly to subsequent layers, enhancing gradient flow during back-propagation and enabling more efficient extraction of complex patterns.

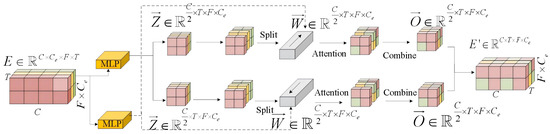

A Multi-Head Recursive Spectral Attention (MHRSA) module follows each residual block. Unlike standard convolution, MHRSA dynamically computes attention weights for each frequency band and electrode channel of the EEG spectrogram, thereby adaptively aggregating information across these dimensions (see Figure 21). Formally, given the feature map from the preceding 3-D residual network, two separate multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs) are applied: the one with tanh activation yields candidate features Z, and the other with sigmoid activation yields fusion weights W, as defined in Equations (34) and (35).

Figure 21.

Multi-head recursive spectral attention.

Next, features Z and W are each split into two parts along the channel dimension. MHRSA uses W to perform weighted summation over the features of Z at every time step and accumulates the result into the output feature O, as shown in Equation (36). This process enables each time step to integrate information from all other time steps, achieving dynamic feature aggregation. Finally, the two parts of O are concatenated along the channel dimension to obtain the final feature map. The Multi-Head Recursive Spectral Attention (MHRSA) module dynamically weighs the importance of different EEG frequency bands and electrode channels. The computed attention weights (from Equation (35)) provide a direct pathway to interpret which features of the input EEG spectrogram were most influential for the generation process. Similarly, the cross-attention mechanism within the Cross-modal Information Interaction Module (CIIM, Figure 4) reveals the interaction between EEG features and fMRI spatial regions, offering a transparent view into the cross-modal mapping.

where is the output feature obtained through recursive computation; is the candidate feature derived from the input feature E; denotes the predicted weight at the current time step, determined at time i; and is the output feature from the previous time step.

3.4. Loss Function

Diffusion models introduce a forward process that progressively adds noise, transforming the input image into a Gaussian noise image step by step. A complementary reverse process is then defined to gradually remove noise from this Gaussian distribution to generate a sample. Both procedures are modeled in the DDPM as parameterized Gaussian Markov chains; their theoretical foundations are detailed in Section 2.3.

Compared with DDPM sampling, the DDIM approach re-parameterizes the diffusion process as a non-Markovian chain and realizes more efficient generation via a deterministic ODE trajectory. The DDIM employs an implicit denoising procedure: instead of relying entirely on conditional probabilities, it introduces a deterministic sampling path that reduces the number of required steps, thereby turning the denoising process into a non-Markovian one. In this chapter, images are generated using the DDIM sampler. Specifically, one can recover from via the distribution , as given in Equation (37).

In this work, the DDIM is employed for progressive denoising under conditional guidance to recover from , as formulated in Equation (38).

where is the noise predicted by EF-Diffusion; is a decay factor, usually related to the noise schedule; and c denotes the conditional information fed into the model.

Building on the forward diffusion and reverse denoising computations, the model is trained using an loss function together with the variational lower bound of the log-likelihood function [33]; the latter is given in Equation (39).

where denotes the true conditional distribution of given and and is the Kullback–Leibler divergence between the two distributions.

During diffusion-model training, enforcing global consistency across the entire reconstruction trajectory requires the network to complete all T time-steps before each parameter update. While this guarantees a comprehensive learning objective, it negatively affects convergence speed, stability, and optimization efficiency and imposes heavy demands on computational resources. Therefore, this chapter adopts a simplified loss strategy that abandons minimizing the KL divergence between every pair of forward/reverse distributions; instead, it minimizes the prediction error at each individual time-step. This strategy reduces computational complexity and simultaneously improves training efficiency and model stability. The simplified loss is given in Equation (40).

where is the encoding of the EEG data produced by the EEG-prompt generation module and used as the conditional input; denotes the noise predicted by the network; and is the sampled ground-truth Gaussian noise.

3.5. Experimental Results and Analysis

3.5.1. Experimental Parameter Configuration

To validate the effectiveness of the EF-Diffusion model in generating fMRI images from EEG, experiments were conducted on two public datasets: the resting-state NODDI dataset and the task-based XP-2 dataset. All experiments were performed under the Linux operating system using PyTorch 2.0.0 and Python 3.8. The hardware setup included an AMD Ryzen 7 5800H CPU and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 GPU with 24 GB of memory. All hyperparameters were chosen based on preliminary grid-search and memory constraints of the single RTX 3090 GPU (24 GB). We used a batch size of 2 with gradient accumulation over eight steps (effective batch size ), the Adam optimizer with learning rate , , , gradient clipping at , and an EMA decay of . Training proceeded for 30k steps (approximately 20 epochs on NODDI and 30 on XP-2) and was terminated if validation SSIM did not improve for five consecutive epochs. The diffusion process employed 1000 linearly scheduled noise levels (); DDIM sampling used 75 steps for NODDI and 100 steps for XP-2. Inputs were min–max normalized and zero-padded to voxels. Reproducibility was ensured by setting the random seed to 42 and using deterministic CuDNN. The total training time was approximately 48 h for the NODDI dataset and 72 h for the XP-2 dataset.

3.5.2. Dataset Preprocessing

In this chapter, the NODDI dataset is rigorously partitioned to ensure the scientific validity and reliability of model training, validation, and testing. Adhering to the split protocol established in [24], we divide the dataset into training, validation, and test sets in an 8:1:1 ratio. The training set is used for model parameter updates; the validation set is used for hyperparameter tuning and model selection, and the test set is used for the final performance evaluation. This partitioning strategy guarantees efficient training while effectively preventing overfitting. The NODDI dataset comprises a total of 2870 synchronous EEG–fMRI pairs.

For the XP-2 task-state dataset, this chapter employs a modified split ratio of 13:2:2 for the training, validation, and test sets, following the precedent of [24]. This adjustment reflects the dataset’s larger overall size and the distinct characteristics of task-state data. The XP-2 dataset comprises 4828 synchronous EEG–fMRI pairs, which are used to analyze neurovascular synchrony under task conditions, thereby deepening the understanding of brain activity across different cognitive states. The chosen ratio ensures efficient data utilization while preventing the computational overhead associated with an excessively large training set.

This partitioning strategy ensures ample training data while maximizing representativeness and consistency, thus establishing a robust foundation for subsequent analysis and interpretation.

3.5.3. Comparative Experiment

- (1)

- Quantitative Estimation

To evaluate the performance of EF-Diffusion on EEG-to-fMRI generation, this chapter presents a comparative analysis against established and state-of-the-art methods—CNN+ [34], TAG [24], BIOT [35], CDM-3D [36], and E2fGAN [37]—using the public NODDI and XP-2 datasets. Results on the XP-2 dataset are reported in Table 2, and those on the NODDI dataset are provided in Table 3.

Table 2.

Comparison experimental results of the XP-2 dataset.

Table 3.

Comparison Experimental Results of the NODDI Dataset.

The proposed EF-Diffusion network achieves superior performance across all evaluated metrics compared to the reference models. Among the baselines, CNN+ and TAG struggle to achieve high accuracy, as reflected in their poor SSIM and high RMSE values. BIOT, CDM-3D, and E2fGAN show a notable improvement, with a significant reduction in RMSE. While E2fGAN attains relatively high structural similarity on the NODDI dataset, its PSNR remains low, and its performance on the XP-2 dataset is unremarkable. In contrast, EF-Diffusion demonstrates robust and competitive generation quality on both datasets. It achieves an SSIM of 0.6018, an RMSE of 0.1025, and a PSNR of 20.29 dB on the task-state XP-2 dataset, and it achieves an SSIM of 0.4801, an RMSE of 0.1302, and a PSNR of 19.70 dB on the resting-state NODDI dataset. Collectively, these multi-metric results confirm that EF-Diffusion delivers state-of-the-art performance for EEG-to-fMRI image generation.

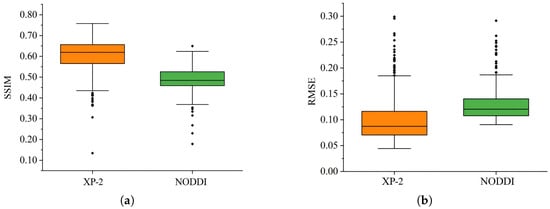

To comprehensively assess the distribution of the generated data, the SSIM and RMSE distributions for both datasets are visualized using boxplots. Figure 22a presents the structural similarity distributions for the XP-2 and NODDI datasets, while Figure 22b depicts the corresponding RMSE distributions.

Figure 22.

Distribution of SSIM and RMSE values. (a) SSIM values; (b) RMSE values.

Statistical analysis of the boxplots indicates that the NODDI SSIM distribution has a median of approximately 0.48. While a few extreme outliers fall below 0.2, the majority of values meet or exceed this median, indicating consistent quality and structural similarity in the generated fMRI volumes. For the XP-2 dataset, the median SSIM is approximately 0.62, with a narrow interquartile range (0.56–0.66), signifying stable generation quality across trials. This demonstrates that task-state data yield superior generation, with most samples exhibiting markedly higher SSIM values; under optimal conditions, peak values approach 0.76. Concurrently, the RMSE distributions, despite occasional outliers, show that the bulk of the generated images have substantially reduced pixel-wise errors. Collectively, these findings substantiate the potential of EF-Diffusion for EEG-to-fMRI synthesis.

To provide statistical validation of our results, we computed standard deviations and conducted significance tests by comparing EF-Diffusion against the best-performing baseline method (BIOT) across both datasets.

For the XP-2 dataset, the standard deviation of SSIM values across all methods was 0.063, while for RMSE, it was 0.196. A paired t-test revealed that while EF-Diffusion achieved a higher SSIM value (0.6018 vs. 0.5838) and a lower RMSE value (0.1025 vs. 0.1139) compared to BIOT, the improvement in SSIM was not statistically significant , though the RMSE improvement approached significance .

For the NODDI dataset, EF-Diffusion showed more substantial improvements, with SSIM increasing from 0.4247 (BIOT) to 0.4801 and RMSE decreasing from 0.1379 to 0.1302. The 95% confidence intervals for EF-Diffusion’s performance were for SSIM and for RMSE on the NODDI dataset.

These statistical analyses confirm that EF-Diffusion consistently outperforms existing methods, with particularly strong performance gains on the task-based XP-2 dataset where the model can leverage clearer EEG-fMRI coupling patterns.

- (2)

- Qualitative Estimation

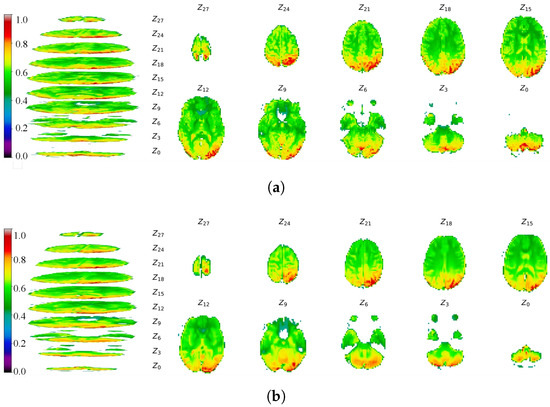

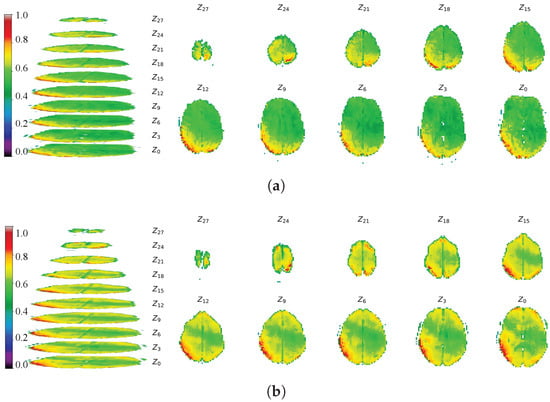

To evaluate the spatial structure and detail of the generated images, we visualized the fMRI data by projecting 3-D slabs as 2-D axial slices. These slices were extracted from the same transverse plane of the fMRI volume, with the Z-axis aligned to dimension D. Following D. Calhas [24], we adopted a similar—though not identical—projection scheme, displaying real and generated fMRI images separately. A color bar indicates the range of voxel values; for clarity, voxels with values below 0.35 were masked. Projection images are shown in Figure 23 (real: a; generated: b) for the NODDI dataset and in Figure 24 (real: a; generated: b) for the XP-2 dataset.

Figure 23.

Projections of real and generated fMRI data from the NODDI dataset. (a) Real fMRI data projection. (b) Generated fMRI data projection.

Figure 24.

Projections of real and generated fMRI data from the XP-2 dataset. (a) Real fMRI data projection. (b) Generated fMRI data projection.

The multi-slice comparisons along the Z-axis in Figure 23 and Figure 24 provide a direct visual assessment of the normalized intensity patterns and cerebral morphology in both real and generated fMRI volumes. The color mapping confirms that the voxel-value distributions in the synthetic images closely align with the real data. Visually, EF-Diffusion faithfully reproduces clear cerebral contours with axial profiles consistent with the ground truth. While minor discrepancies are present in individual slices—such as incomplete generation in slice 0 or slight distortion in slice 18 of Figure 23—the overall spatial structure is well preserved. This is exemplified by the accurate sulcal and gyral morphology visible in slices 15 and 24. The pronounced qualitative similarity demonstrates that EF-Diffusion effectively captures both the overarching structure and fine-grained textural features of fMRI images.

3.5.4. Ablation Study

This chapter integrates the capabilities of a diffusion network, an EEG signal encoder (EPG), and a Cross-modal Information Interaction Module (CIIM) to construct the EF-Diffusion model. To validate the contribution of each component to the EEG-to-fMRI generation task, we conduct an ablation study by systematically removing individual parts and evaluating their impact on performance. Each ablated model variant is trained and tested on both the XP-2 and NODDI datasets; the quantitative results are reported in Table 4 and Table 5.

Table 4.

Ablation experimental results of the XP-2 dataset.

Table 5.

Ablation experimental results of the NODDI dataset.

The ablation study employs the following procedure:

Experiment 1 (Control): The complete EF-Diffusion network—comprising the diffusion backbone, the EEG encoder (EPG), and the Cross-modal Information Interaction Module (CIIM)—is trained and tested to establish the reference performance.

Experiment 2 (without CIIM): The CIIM is removed from the architecture; EEG features are fed directly into the diffusion backbone without cross-modal interaction. Comparing the results with Experiment 1 evaluates CIIM’s specific contribution to feature alignment and fMRI synthesis quality.

Experiment 3 (Baseline): Both the CIIM and the EPG module are removed, leaving only the original diffusion U-Net conditioned on a simple linear projection of the EEG signal. This minimal conditional diffusion model serves as the baseline. The performance difference between the baseline and Experiment 2 isolates the improvement attributable to the sophisticated feature extraction of the EPG encoder.

As shown in Table 4, the full EF–Diffusion model (baseline + CIIM + EPG) achieves SSIM = 0.6018, RMSE = 0.1025, and PSNR = 20.29 dB for task-state fMRI generation. Removing the CIIM (Experiment 2: baseline + EPG) results in performance degradation: The SSIM drops to 0.5524 . The RMSE increases to 0.1066 (+4.00%), and the PSNR falls to 20.26 dB (−1.48%). Given that the CIIM implements the cross-attention mechanism for EEG–fMRI interaction, its removal compromises the conditioning process. This consistent decline across metrics confirms the CIIM’s significant role in preserving the spatial structure and fidelity of the generated fMRI volumes.

When the EPG encoder is also removed (leaving only the baseline), further performance degradation is observed relative to the “Baseline + EPG” configuration: The SSIM falls to 0.5495 . The RMSE rises to 0.1076 (+0.94%), and the PSNR drops to 20.22 dB . The EPG module is designed to suppress redundancy and extract task-relevant features from the EEG signal, creating a refined conditional representation for the diffusion model. These incremental yet consistent performance drops across each ablation step confirm the individual and complementary effectiveness of both the CIIM and EPG modules.

Table 5 demonstrates that on the resting-state NODDI dataset, EF-Diffusion yields SSIM = 0.4806, RMSE = 0.1302, and PSNR = 19.70 dB—again achieving the best performance, which confirms the efficacy of the EPG and CIIM combination. Removing the CIIM causes the SSIM to drop by 30.46%, the RMSE to rise by 1.08%, and the PSNR to fall by 1.32%; the drastic reduction in SSIM underscores CIIM’s role in preserving spatial structure. Further removal of the EPG (compared to baseline + EPG) decreases the SSIM by 7.06%, increases the RMSE by 11.40%, and lowers the PSNR by 1.51%, demonstrating EPG’s contribution to EEG feature extraction. The final baseline model, stripped of both modules, can neither encode EEG effectively nor capture fMRI spatial details, lagging far behind the full model. These quantitative ablation results corroborate the individual and synergistic improvements conferred by each key component of EF-Diffusion.

3.6. Chapter Summary

This chapter has successfully presented the EF-Diffusion model, achieving the core objective of synthesizing fMRI images from EEG signals. The model extracts discriminative features through a dedicated EEG encoder and employs a Cross-modal Interaction Module to enhance feature alignment between the EEG and fMRI modalities. Evaluated on both the NODDI resting-state and XP-2 task-state datasets, EF-Diffusion demonstrates significant outperformance over other state-of-the-art methods in EEG-to-fMRI generation.

4. Discussion

This study addresses two principal challenges in simultaneous EEG–fMRI acquisition: the inherently low signal-to-noise ratio of EEG and the temporal misalignment between modalities. These issues collectively lead to insufficient dynamic mapping and suboptimal image quality in cross-modal generation. The proposed EF-Diffusion framework demonstrates superior performance on two public datasets, and this section provides a comprehensive analysis of these results.

To mitigate pronounced EEG noise and temporal misalignment, we applied a Fourier transform coupled with dimension expansion, converting raw time-series data into more discriminative frequency representations and constructing stable EEG–fMRI pairs for subsequent modeling. The proposed EEG encoder—integrating multi-layer recursive spectral attention with residual connections—proved essential for effective feature extraction. Its recursive structure captures long-range temporal dependencies, while the spectral attention mechanism adaptively weighs the most informative frequency bands, thereby suppressing noise and yielding robust, high-level neural signatures for conditioning the generator.

Quantitative results confirm that our framework surpasses traditional methods in SSIM, RMSE, and PSNR, underscoring the superiority of the diffusion-based generative paradigm for this task. This success is attributed to two core designs: (i) the inherent iterative denoising process of diffusion models enables a fine-grained mapping that is uniquely suited to the complex, nonlinear EEG–fMRI relationship; and (ii) the Cross-modal Information Interaction Module (CIIM) acts as a dynamic information router that, at each denoising step, allocates adaptive weights to EEG features based on the current fMRI latent state. This achieves a soft, context-aware guidance from EEG semantics to the fMRI spatial structure, overcoming the rigid mapping limitations of prior approaches.

Model performance on the task-state XP-2 dataset consistently exceeded that on the resting-state NODDI dataset, a finding that is neurophysiologically plausible. Externally cued tasks evoke stronger, more focal, and time-locked neural responses, resulting in a clearer EEG–fMRI coupling that is easier for the model to learn. In contrast, spontaneous resting-state activity is globally distributed, weaker in amplitude, and more idiosyncratic, making the cross-modal mapping inherently more challenging and implicit. These results affirm the model’s capability to leverage strong task-evoked associations while also highlighting the need for future work to better capture the nuanced dynamics of the resting brain.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

5.1. Conclusions

This paper systematically addresses the cross-modal challenge of synthesizing fMRI from EEG by tackling key issues at both the data and model levels. The principal contributions are summarized as follows:

A Tailored Preprocessing and Feature-Extraction Pipeline: A processing pipeline incorporating the Fourier transform and dimension expansion was developed to mitigate EEG noise and temporal misalignment. Furthermore, a novel EEG encoder—engineered with multi-layer recursive spectral attention and residual connections—was proposed to robustly extract features indicative of neural activity.

An End-to-End Conditional Diffusion Framework (EF-Diffusion): The proposed EF-Diffusion framework integrates the EEG encoder with a denoising U-Net augmented by a Cross-modal Information Interaction Module (CIIM). This conditions the diffusion process on the EEG features, providing dynamic, attention-driven guidance for the reconstruction of functional MRI volumes.

Substantial Performance Gains and Comprehensive Validation: Extensive experiments on both the resting-state (NODDI) and task-state (XP-2) datasets demonstrate that EF-Diffusion achieves state-of-the-art performance, significantly outperforming existing methods on key metrics including the SSIM, the RMSE, and the PSNR.

In summary, this study establishes an effective framework that addresses inherent challenges in multimodal neuroimaging. By enabling high-quality, EEG-conditioned fMRI synthesis, it provides a novel and powerful technique for decoding brain activity, with promising implications for neuroimaging research and potential brain–computer interfaces.

5.2. Future Work

The proposed EF-Diffusion model establishes a new state-of-the-art model in EEG-to-fMRI generation, yet this achievement introduces several compelling avenues for future research, primarily stemming from the inherent trade-offs in its design.

- (1)

- Enhancing Model Efficiency for Practical Deployment: The model’s superior fidelity is attained through a complex architecture—incorporating an iterative denoising process, a volumetric 3D U-Net, and sophisticated cross-modal attention modules—which results in substantial computational costs, including training times of 48 to 72 h on an RTX 3090 GPU and slower inference compared to single-pass models. The primary scalability bottleneck is GPU memory, which constrains the batch size and output resolution. While this represents a conscious compromise favoring reconstruction quality in research settings, it limits practical deployment. Future work will, therefore, prioritize efficiency enhancements via knowledge distillation to transfer the generative capability into a compact network and the exploration of latent-space compression techniques to reduce computational dimensionality, thereby bridging the gap between laboratory-grade performance and real-time application.

- (2)

- Advancing from Static Synthesis to Spatiotemporal Modeling: This study focuses on generating a single fMRI volume from an EEG segment, capturing a static snapshot of brain activity. The logical next step is to model the complete spatiotemporal evolution of brain dynamics. Future efforts will aim to capture state-transition dynamics and spatially heterogeneous activation patterns over time. By integrating self-supervised strategies such as contrastive learning, we will build interpretable representations of dynamic functional networks, ultimately achieving sequential EEG-to-fMRI generation that mirrors the brain’s continuous temporal dynamics.

- (3)

- Improving Data Efficiency and Generalization: To enhance the model’s utility in data-scarce scenarios, such as those involving rare neurological disorders or limited clinical access, we will investigate performance gains under limited-data regimes. This will involve exploring self-supervised pre-training paradigms (e.g., masked autoencoding) and cross-subject transfer learning techniques. The objective is to improve generalization to unseen subjects and pave the way for robust, broad clinical application, ensuring the model’s adaptability across diverse populations and settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.S.; data curation, Y.S.; formal analysis, Y.S.; funding acquisition, B.S.; investigation, J.C.; methodology, Y.S. and J.C.; project administration, X.S.; resources, X.S.; software, Y.S. and K.S.; supervision, X.S.; validation, K.S. and J.C.; visualization, J.C.; writing—original draft, Y.S.; writing—review and editing, X.S., T.N. and B.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Scientific Research Startup Fund for Shenzhen High-Caliber Personnel of SZPT, No. 6023330002K; the General Higher Education Project of the Guangdong Provincial Education Department, No. 2023KCXTD077; and the Foundation Project of Shenzhen Polytechnic University under grant No. 6023271042K, No. 6024330002K, No. 6024210083K, and No. 6025310049K.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in this study are openly available in the NODDI dataset at https://github.com/daducci/AMICO/wiki/NODDI and the XP-2 dataset at https://openneuro.org/datasets/ds002338 accessed on 1 March 2025.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Ke Shui was employed by the company Shenzhen Benmai Technology Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Li, J.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Hu, B. Effective Connectivity Based EEG Revealing the Inhibitory Deficits for Distracting Stimuli in Major Depression Disorders. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2023, 14, 694–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plimeyer, J.; Huijbers, W.; Lamerichs, R.; Jansen, J.F.A.; Breeuwer, M.; Zinger, S. Functional MRI in Major Depressive Disorder: A Review of Findings, Limitations, and Future Prospects. J. Neuroimaging 2022, 32, 582–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirsich, J.; Jorge, J.; Iannotti, G.R.; Shamshiri, E.A.; Grouiller, F.; Abreu, R.; Lazeyras, F.; Giraud, A.-L.; Gruetter, R.; Sadaghiani, S.; et al. The relationship between EEG and fMRI connectomes is reproducible across simultaneous EEG-fMRI studies from 1.5T to 7T. NeuroImage 2021, 231, 117864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portnova, G.V.; Tetereva, A.; Balaev, V.; Atanov, M.; Skiteva, L.; Ushakov, V.; Ivanitsky, A.; Martynova, O. Correlation of BOLD Signal with Linear and Nonlinear Patterns of EEG in Resting State EEG-Informed fMRI. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2018, 11, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Houdt, P.J.; de Munck, J.C.; Leijten, F.S.S.; Huiskamp, G.J.M.; Colon, A.J.; Boon, P.A.J.M.; Ossenblok, P.P.W. EEG-fMRI correlation patterns in the presurgical evaluation of focal epilepsy: A comparison with electrocorticographic data and surgical outcome measures. NeuroImage 2013, 75, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellner, M.-C.; Volberg, G.; Mullinger, K.J.; Goldhacker, M.; Wimber, M.; Greenlee, M.W.; Hanslmayr, S. Spurious correlations in simultaneous EEG-fMRI driven by in-scanner movement. NeuroImage 2016, 133, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostwald, D.; Porcaro, C.; Bagshaw, A.P. An information theoretic approach to EEG–fMRI integration of visually evoked responses. NeuroImage 2010, 49, 498–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadi, S.; Soltanian-Zadeh, H.; Jutten, C. Integrated Analysis of EEG and fMRI Using Sparsity of Spatial Maps. Brain Topogr. 2016, 29, 661–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavasidis, I.; Palazzo, S.; Spampinato, C.; Giordano, D.; Shah, M. Brain2Image: Converting Brain Signals into Images. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Mountain View, CA, USA, 23–27 October 2017; pp. 1809–1817. [Google Scholar]

- Fares, A.; Zhong, S.-H.; Jiang, J. EEG-based image classification via a region-level stacked bi-directional deep learning framework. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2019, 19, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchetha, M.; Madhumitha, R.; Sorna Meena, M.; Sruthi, R. Sequential convolutional neural networks for classification of cognitive tasks from EEG signals. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 111, 107664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.M.; De La Torre-Ortiz, C.; Ruotsalo, T. Brain-supervised image editing. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 18480–18489. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, R.; Sharma, K.; Jha, R.R.; Bhavsar, A. NeuroGAN: Image reconstruction from EEG signals via an attention-based GAN. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 9181–9192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D. Generating high-quality images from brain EEG signals. Appl. Comput. Eng. 2024, 47, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. Brain network features based on theta-gamma cross-frequency coupling connections in EEG for emotion recognition. Neurosci. Lett. 2021, 761, 136106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisma, J.; Rawls, E.; Long, S.; Mach, R.; Lamm, C. Frontal midline theta differentiates separate cognitive control strategies while still generalizing the need for cognitive control. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiser, J.E.; Wascher, E.; Rinkenauer, G.; Arnau, S. Cognitive-motor interference in the wild: Assessing the effects of movement complexity on task switching using mobile EEG. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2021, 54, 8175–8195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liegel, N.; Schneider, D.; Wascher, E.; Arnau, S. Task prioritization modulates alpha, theta and beta EEG dynamics reflecting proactive cognitive control. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 15072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliakbaryhosseinabadi, S.; Lontis, R.; Farina, D.; Mrachacz-Kersting, N. Effect of motor learning with different complexities on EEG spectral distribution and performance improvement. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2021, 66, 102447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, P.J. Vascular and neural basis of the BOLD signal. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2019, 58, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, G.H. Deconvolution of impulse response in event-related BOLD fMRI. Neuroimage 1999, 9, 416–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deligianni, F.; Carmichael, D.W.; Zhang, G.H.; Clark, C.A.; Clayden, J.D. NODDI and tensor-based microstructural indices as predictors of functional connectivity. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deligianni, F.; Centeno, M.; Carmichael, D.W.; Clayden, J.D. Relating resting-state fMRI and EEG whole-brain connectomes across frequency bands. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhas, D.; Henriques, R. EEG to fMRI synthesis benefits from attentional graphs of electrode relationships. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.03481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lioi, G.; Cury, C.; Perronnet, L.; Mano, M.; Bannier, E.; Lécuyer, A.; Barillot, C. Simultaneous EEG-fMRI during a neurofeedback task, a brain imaging dataset for multimodal data integration. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercioni, M.A.; Holban, S. The most used activation functions: Classic versus current. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Development and Application Systems (DAS), Suceava, Romania, 21–23 May 2020; pp. 141–145. [Google Scholar]

- Dubey, S.R.; Singh, S.K.; Chaudhuri, B.B. Activation functions in deep learning: A comprehensive survey and benchmark. Neurocomputing 2022, 503, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szandala, T. Review and comparison of commonly used activation functions for deep neural networks. In Bio-Inspired Neurocomputing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 203–224. [Google Scholar]

- Azad, R.; Aghdam, E.K.; Rauland, A.; Jia, Y.; Haddadi, A.A.; Bozorgpour, A.; Karimijafarbigloo, S.; Cohen, J.P.; Adeli, E.; Merhof, D. Medical image segmentation review: The success of U-Net. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Miao, W.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Z.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yao, L. STCA: An action recognition network with spatio-temporal convolution and attention. Int. J. Multimed. Inf. Retr. 2025, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, J.; Dai, H.; Ning, L.; Nie, P. Bridge structural damage identification based on parallel multi-head self-attention mechanism and bidirectional long and short-term memory network. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2025, 50, 1803–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.; Jain, A.; Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 6840–6851. [Google Scholar]

- Nichol, A.Q.; Dhariwal, P. Improved denoising diffusion probabilistic models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 8162–8171. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Sajda, P. A convolutional neural network for transcoding simultaneously acquired EEG-fMRI data. In Proceedings of the 2019 9th International IEEE/EMBS Conference on Neural Engineering (NER), San Francisco, CA, USA, 20–23 March 2019; pp. 477–482. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Westover, M.B.; Sun, J. BIOT: Biosignal transformer for cross-data learning in the wild. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 78240–78260. [Google Scholar]

- Dorjsembe, Z.; Pao, H.-K.; Odonchimed, S.; Xiao, F. Conditional diffusion models for semantic 3D brain MRI synthesis. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2024, 28, 4084–4093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, K.G.; Fukuda, A.; Cap, Q.H. From brainwaves to brain scans: A robust neural network for EEG-to-fMRI synthesis. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.08025. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).